Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a deadly respiratory disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, which has caused a global pandemic since early 2020 and severely threatened people's livelihoods and health. Patients with pre-diagnosed conditions admitted to hospital often develop complications leading to mortality due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and associated multiorgan failure and blood clots. ARDS is associated with a cytokine storm. Cytokine storms arise due to elevated levels of circulating cytokines and are associated with infections. Targeting various pro-inflammatory cytokines in a specific manner can result in a potent therapeutic approach with minimal host collateral damage. Immunoregulatory therapies are now of interest in order to regulate the cytokine storm, and this review will summarize and discuss advances in targeted therapies against cytokine storms induced by COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, anti-inflammatory, targeted therapy, cytokine storm, biologics, multiorgan failure

1. COVID-19 infection and the cytokine storm

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019 and since then has spread across the globe rapidly, leading to over 4.9 million deaths and over 243 million infections (as of October 2021) [1]. COVID-19 infection leads to a hallmark hyper-inflammatory state, more commonly known as a ‘cytokine storm’ [2,3]. The onset of a cytokine storm leads to impaired oxygen-exchange and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is driven by a cytokine storm caused by upregulated levels of inflammatory mediators. ARDS is thought to be the cause of death in up to 70% of fatal COVID-19 cases where a cytokine storm has been detected [4]. Furthermore, continuous inflammation causes an imbalance in pro- and anti-coagulative factors, leading to microthrombosis, multiorgan injury and failure [5].

With a marked similarity to SARS and MERS, severely ill patients with COVID-19 demonstrate decreased CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte counts, increased Th17 cell proliferation and abnormally elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, notably interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (figure 1) [6–8]. Moreover, post-mortem pathological examinations reported diffuse alveolar damage, mononuclear infiltration and pulmonary oedema, also characteristic of other highly pathogenic coronaviruses [8]. These findings altogether are indicative of a cytokine storm underlying ARDS and multiple organ failure (MOF) in most severe cases. Thus, targeting exaggerated cytokine response may be effective in improving outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 immune response and outcomes. SARS-CoV-2 infection of host cells via the ACE-2 receptors triggers an immune response, notably activation of neutrophils, macrophages and Th17 cells, downregulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and increased cytokine production. The abnormally elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, known as cytokine storm, can cause cell death and tissue damage across the body that may lead to MOF and death.

2. Anti-inflammatory therapeutic approaches used to date to combat COVID-19

Multiple anti-inflammatory therapies have been used to diminish high cytokine levels and to mitigate the cytokine storm-related morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients (tables 1 and 2). However, none of the existing therapeutic approaches has demonstrated desired efficacy, and no consensus has been reached yet with regard to timing, duration and type of regimen. Untargeted immunosuppression of cytokine storm in COVID-19 with corticosteroids and anti-malarials has been associated with mixed success so far. While anti-inflammatory corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, have been successfully used for the treatment of critically ill SARS and MERS patients, these drugs failed to deliver on their promise for long-term use in COVID-19 treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms due to increased risk of co-infections [38]. However, a randomized, open-label clinical trial, RECOVERY, showed that dexamethasone could decrease mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who require respiratory support [39]. The short-term use of low-dose methylprednisolone was reported to improve clinical outcomes for severely ill patients, but further clinical investigations are required for confirmation [40,41]. The clinical performance of anti-malarials, chloroquine and its derivative hydroxychloroquine is also inconsistent. While it has been suggested that chloroquine inhibits production and release of IL-6 and TNF-α [42] and hydroxychloroquine modulates antigen processing in antigen-presenting cells [43], thus both suppressing cytokine storm, major clinical trials with these drugs have been halted due to suboptimal efficacy and prominent adverse effects [44,45]. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), derived from pooled human plasma, has been used for the treatment of various immune diseases [46]. As an immunomodulator, IVIG can suppress inflammation [9,47], and in a recent multi-centre retrospective cohort study proved that when administered early, IVIG improves prognosis for critically ill COVID-19 patients [48].

Table 1.

Small-molecule-based targeted anti-inflammatory approaches in patients with COVID-19. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; MF = myelofibrosis; cGVHD = graft-versus-host disease; MCL = mantle cell lymphoma; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; WM = Waldenström macroglobulinemia; MZL = marginal zone lymphoma; LAM = lymphangioleiomyomatosis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; Ps = plaque psoriasis.

| drug | cytokine regulation | study type (identification number), status | study aim | original indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK inhibitors | ||||

| baricitinib | IL-6: JAK1, JAK2, TYK2; IFN-ɣ: JAK1, JAK2; IL-2, IL-4, IL-7: JAK1, JAK3 [9] | Phase III (NCT04421027), recruiting [10] | to assess effectiveness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | RA |

| ruxolitinib | IL-6: JAK1, JAK2, TYK2; IFN-ɣ: JAK1, JAK2; IL-2, IL-4, IL-7: JAK1, JAK3 [9] | Phase II and III (NCT04359290), recruiting [11] | to evaluate safety and efficacy in patients with COVID-19 severe pneumonia | MF, cGVHD |

| BTK inhibitors | ||||

| acalabrutinib | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1 [12] | Phase II (EudraCT 2020-001736-95), active [13] | to evaluate efficacy and safety of multiple candidate agents for treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients | MCL |

| ibrutinib | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1 [14] | Phase II (NCT04439006), recruiting [15] | to study side effects, best dose and its efficacy in treating COVID-19 patients who require hospitalization | MCL, CLL, WM, MZL, cGVHD |

| mTOR inhibitor | ||||

| rapamycin/ sirolimus | IL-1β, IL-6 [16] | Phase II (NCT04341675), recruiting [17] | to assess clinical outcomes and improvement in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | LAM |

| PDE4 inhibitors | ||||

| apremilast | IFN-ɣ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, IL-10 [18] | Phase II (NCT04488081), recruiting [19] | to evaluate efficacy for treatment of critically ill COVID-19 patients | PsA, Ps |

Table 2.

Biologic-based targeted anti-inflammatory approaches in patients with COVID-19. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; GCA, giant cell arteritis; SJIA, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; iMCD, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease; CAPS, cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes; TRAPS, tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome; HID, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; Ps, plaque psoriasis; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; UV, uveitis; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

| name | drug type | study type (identification number), status | study aim | original indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6/IL-6R targeting | ||||

| tocilizumab | anti-IL-6R human IgG1 mAb | Phase III (NCT04320615), completed [20] | to evaluate safety, efficacy, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia | RA, CRS, GCA, PJIA |

| sarilumab | anti-IL-6R human IgG1 mAb | Phase III (NCT04327388), completed [21] | to evaluate clinical efficacy in patients with severe or critical COVID-19 | RA |

| clazakizumab | anti-IL-6 human IgG1 mAb | Phase II (NCT04348500), active [22] | to evaluate safety and adverse events in patients with COVID-19 | RA |

| siltuximab | anti-IL-6 chimeric human–mouse IgG1 mAb | Phase III (NCT04330638), active [23] | to evaluate safety and efficacy individual or in combination with IL-1 blocker (anakinra) in patients with COVID-19 and systemic cytokine release syndrome | iMCD |

| IL-1R targeting | ||||

| anakinra | recombinant human IL-1Rα antagonist | Phase III (NCT04362111), recruiting [24] | to determine effect of early treatment with COVID-19-induced pneumonia | RA, CAPS |

| canakinumab | anti-IL-1β human IgG1κ mAb | Phase III (NCT04362813), active [25] | to evaluate the safety and efficacy with COVID-19-induced pneumonia | CAPS, TRAPS, HIDS/MKD, FMF, SJIA |

| GM-CSF/GM-CSF-R targeting | ||||

| mavrilimumab | anti-GM-CSF-R human IgG4 mAb | Phase II and Phase III (NCT04447469), recruiting [26] | to evaluate the safety and efficacy of two dose levels in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation | RA |

| otilimab | anti-GM-CSF human IgG1 mAb | Phase II (NCT04376684), active [27] | to evaluate benefit–risk in patients with severe pulmonary COVID-19 related diseases | RA |

| lenzilumab | anti-GM-CSF human IgG1κ mAb | Phase III (NCT04351152), recruiting [28] | to evaluate the impact on time to recovery in hospitalized patients with severe or critical COVID-19 pneumonia | RA |

| TJ003234 | anti-GM-CSF human IgG1 mAb | Phase II and III (NCT04341116), recruiting [29] | to evaluate the safety and efficacy in patients with severe COVID-19 disease | RA |

| gimsilumab | anti-GM-CSF human IgG1 mAb | Phase II (NCT04351243), active [30] | to evaluate the safety and efficacy in patients with lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to COVID-19 | RA |

| TNFα targeting | ||||

| adalimumab | anti-TNFα human recombinant IgG1 mAb | Phase IV (ChiCTR2000030089), recruiting [31] | to evaluate the safety and efficacy in patients with severe COVID-19 | RA, JIA, PsA, AS, CD, UC, Ps, HS, UV |

| Phase II (ISRCTN33260034), recruiting [32] | to evaluate effectiveness in preventing or reducing severity of COVID19 disease | |||

| infliximab | anti-TNFα recombinant chimeric human–mouse IgG1 mAb | Phase II (NCT04425538), active [33] | to assess efficacy in patients with severe or critical COVID-19 disease | RA, CD, UC, AS, PsA, Ps |

| IFN-ɣ targeting | ||||

| emapalumab | anti-IFN-ɣ human IgG1 mAb | Phase II and III (NCT04324021), terminated [34] | to assess safety and efficacy in patients with severe COVID-19 disease | HLH |

| IL-8 targeting | ||||

| BMS-986253 | anti-IL-8 human IgG1κ mAb | Phase II (NCT04347226), recruiting [35] | to evaluate time-to-improvement following treatment compared to standard of care in patients with COVID-19 respiratory disease | BRAF V600 mutation-positive unresectable or metastatic melanoma |

| CCR5 targeting | ||||

| leronlimab | anti-CCR5 human IgG4 mAb | Phase II (NCT04343651), active [36] | to evaluate safety and efficacy in patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms of COVID-19 infection | AIDS |

| Phase II (NCT04347239), recruiting [37] | to evaluate safety and efficacy in patients with severe or critical symptoms of COVID-19 infection | |||

The complexity of the immune system as a whole and in particular the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 with elevated levels of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10, respectively [49], may underpin the mixed outcomes of general immunosuppressive anti-COVID-19 treatments so far. However, targeted immunomodulating therapies have been explored on par and hold promise to become a potential first-line COVID-19 therapy.

Most widely, blocking cytokine receptors to suppress their activity is explored as a COVID-19-related cytokine storm treatment avenue. IL-6 has a fundamental role in the cytokine storm, and its elevated levels tend to be correlated with the disease severity [50–52]. A recombinant humanized antibody, tocilizumab, binds to soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors, and inhibits IL-6 mediated inflammatory response by blocking its signal transduction [53]. Multiple studies suggest that tocilizumab could effectively improve symptoms and outcome in severe and critical COVID-19 patients [54–58]. However, tocilizumab has been previously linked to increased risk of opportunistic infections for other indications such as rheumatoid arthritis [59], and a major clinical trial has recently demonstrated that this drug was not effective in preventing intubation or death in moderately ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients [60]. Analogously, another rheumatoid arthritis drug, IL-1 receptor antagonist protein, anakinra, which inhibits the activity of pro-inflammatory IL-1α and IL-1β cytokines, has been repurposed for COVID-19 [61]. A retrospective cohort study of patients with COVID-19 and ARDS showed that intravenous administration of a high-dose anakinra improved the clinical status of the participants [61]. Furthermore, anakinra was found to reduce the need for oxygen therapy and the mortality among severe COVID-19 patients [62].

Alternatively, downstream inhibition of major inflammation-associated signalling pathway could provide an alternative approach to cytokine storm suppression, for instance, targeting Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (JAK-STAT) pathway [63]. Early clinical data suggest that the use of currently available JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib and ruxolitinib is associated with improved clinical and laboratory parameters, or faster clinical improvement of severe COVID-19 patients [64,65]. However, the risks may outweigh the benefits for JAK inhibitors in COVID-19 treatment as these drugs may increase the chance of viral reactivation by blocking anti-viral IFN-α production [66], and baricitinib, in particular, has been linked to lower lymphocyte counts, which is already a critical concern for COVID-19 patients [67].

3. Potential targeted therapeutic approaches against the COVID-19 cytokine storm

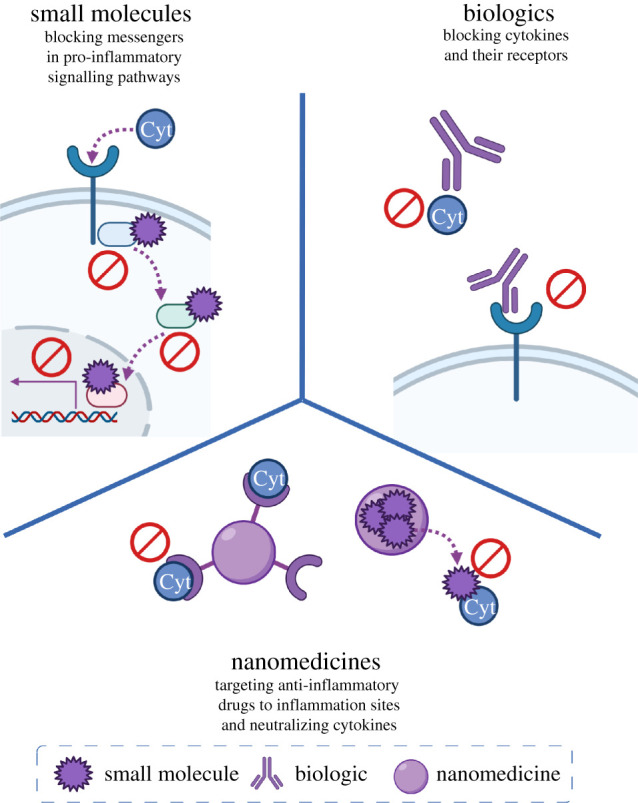

There are as yet few anti-inflammatory therapeutic approaches that have been deliberated upon in a clinical trial setting. However, as more evidence on COVID-19 pathogenesis comes to light, targeting cytokine storm appears more promising, and more therapeutic approaches with different molecular entities such as small-molecule therapeutics, biologics and nanomedicines are investigated (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Therapeutic approaches targeting COVID-19-induced cytokine storm with small-molecule, biologic and nanomedicine therapies.

3.1. Small-molecule therapeutics

The main advantage of small-molecule drugs over any higher molecular weight therapeutic agents is oral availability and predictable pharmacokinetic profiles due to their simple chemical structures [68]. In addition to well-known JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib and ruxolitinib that are currently undergoing clinical trials for COVID-19 repurposing (table 1), other kinase inhibitors are now also being considered in response to the pressing need to mitigate the fatal consequences of COVID-19-related cytokine storm.

Small-molecule inhibitors specific to Bruton's tyrosine kinases (BTK) such as acalabrutinib and ibrutinib are considered for the treatment of COVID-19 due to their ability to inhibit B-cell signalling pathway and suppress subsequent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) [69,70]. Both BTK inhibitors showed improvements in symptoms and outcomes in preliminary studies with acalabrutinib substantially reducing key pro-inflammatory IL-6 cytokine levels [12,14] and are now in the middle of Phase II clinical trials to further evaluate their effectiveness [13,15].

Moreover, a few studies have suggested using sirolimus (also known as rapamycin), a selective mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, to tame the cytokine storm by inhibiting the mTOR pathway that plays a key role in downstream T-cell differentiation and cytokine production [71–74]. The immunosuppressant has previously been shown to shorten the duration of ventilator usage and improved clinical outcomes in patients with severe H1N1 pneumonia by inhibiting T and B cells activation [16]. However, whether its efficacy in influenza treatment can be replicated in COVID-19 is yet to be seen as Phase II clinical trials for sirolimus are soon to begin upon completion of recruitment [75].

Another potential target of interest is phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE-4), which regulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines through cyclic adenosine monophosphate activation [18]. Apremilast was originally proposed as an auto-immune disease treatment and shown to diminish pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6 and IL-13 expression and vice versa to increase anti-inflammatory IL-10 expression [76]. Treatment with the selective PDE-4 inhibitor at early phases of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia resulted in a significant reduction in IL-6 across all four patients with minimal side effects [77]. The early success and excellent safety profile led to further investigation, and apremilast has been accepted for a Phase II clinical trial [19].

3.2. Biologics

The use of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in the treatment of inflammation has been widely accepted for the last decade, with immunomodulatory mAbs generally proven safe and in many cases effective [78]. Most therapeutic approaches for suppressing cytokine storm are based on targeting either the cytokine itself or its receptor. Together with widely investigated tocilizumab, other mAbs targeting IL-6 such as siltuximab and IL-6 receptor such as sarilumab are being considered as promising anti-inflammatory therapies for COVID-19, and both are currently evaluated in Phase III clinical trials in hospitalized COVID-19 patients [23,79]. Another mAb targeting IL-1β cytokine has now also reached Phase III clinical trials [25], previously demonstrating a reduction in serum inflammatory biomarkers in COVID-19 patients upon subcutaneous administration [80].

Anti-TNF-α mAbs have been associated with not only reduced activity of TNF-α but also downregulation of key pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-6, offering a ‘double-whammy’ therapeutic approach [81,82]. Observational clinical data in patients on anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis have shown to be inversely associated with death and hospital admission for COVID-19 [83]; however, no effect on intensive care admission was observed [84]. While the potential use of anti-TNF-α mAbs is backed up by a holistic understanding of the mechanisms of a cytokine storm and observational clinical data, very few clinical studies are currently investigating these therapies for the prevention of cytokine storm progression and overall COVID-19 treatment (table 2) [31,32].

Targeting other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as GM-CSF has also been pursued to curb hyperinflammation [85,86]. Anti-GM-CSF mAb lenzilumab and anti-GM-CSF receptor mAb mavrilimumab, alongside other mAbs used in the treatment of COVID-19, have been associated with earlier clinical improvement in respiratory parameters, demonstrating potential efficacy of this therapeutic approach [28,86,87]. While IFN-γ, IL-8 and C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) mAbs are investigated as anti-cytokine storm therapies in COVID-19 [34,35,37], a few cytokines and chemokines upregulated in a cytokine storm such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and CCL2 are not yet targeted directly by any therapeutic approaches and in light of the urgent need for a viable COVID-19 treatment, drugs against these targets should be evaluated as well.

3.3. Nanomedicine

Although useful in combating the cytokine storm, the use of immunosuppressants will result in systemic reduction in patients' immunity and pose an increased risk of secondary infection or sepsis. Moreover, the short half-lives of small molecules limit the ability to achieve sustained drug delivery and therapeutic benefits. On the other hand, biologics usually suffer from poor bioavailability and, therefore, a higher dose might be required, resulting in an increased risk of unforeseen adverse effects. Encapsulating these therapeutic agents into smart nanocarriers would allow targeted delivery, increased bioavailability and circulation stability as well as optimization of pharmacokinetic profiles of combination therapies as multiple therapeutic agents can be encapsulated into nanoparticles.

A few nanomedicine approaches have emerged as anti-inflammatory COVID-19 treatments. Rao et al. demonstrate decoy nanoparticles formulated by fusing two cellular membrane nanovesicles to protect host cells by competing with virus [88]. Alongside angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptors that bind SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, the nanodecoy possesses IL-6 and GM-CSF receptors on its surface that efficiently bind and neutralize pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and GM-CSF [88]. Thus, nanodecoys have been shown to effectively suppress cytokine levels in acute pneumonia mouse model in vivo [88].

Other nanoparticle-based approaches so far have focused on delivery of non-specific anti-inflammatory agents such as adenosine and corticosteroids. Dormoont et al. reported the development of squalene-based multidrug nanoparticles consisting of adenosine and the antioxidant α-tocopherol as a potential targeted approach for cytokine storm mitigation [89]. Adenosine, a non-specific immunomodulator, has been shown to inhibit TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-12 production and promote the release of anti-inflammatory IL-10 [90]. This nanoformulation exploits the enhanced permeability and retention effect to achieve site-targeted delivery. The multidrug nanoparticle has been shown to accumulate at the site of inflammation and was associated with a significant reduction in TNF-α alongside an increase in IL-10 in endotoxemia mouse model [89]. To avoid systemic immunosuppression and increased risk of secondary infection, nanoformulations of dexamethasone have been previously developed to treat other inflammatory diseases such as cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and inflammatory arthritis and proposed for COVID-19 treatment to improve specificity, stability and efficacy of dexamethasone [91]. However, the idea is still at its early stages, and more research has to be done to find the optimal formulation and evaluate its efficacy.

While nanomedicine has been centre-stage in vaccine development recently, it is so far underused in therapeutic development to combat viral infections in general and COVID-19 in particular [92]. However, more evidence is being amassed on potential benefits of nanomedicine in developing COVID-19 therapies and how nanomedicine can address limitations of repurposed anti-inflammatory agents and improve their specificity, bioavailability and in situ release kinetics [93,94].

4. Challenges and perspectives

As cytokine storm has been convincingly linked to fatal outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infections, targeted approaches to curb hyperinflammation have been widely explored and hold promise of improving prognoses and reducing COVID-19-associated mortality. However, complexity of the immune response in general and specific patterns linked to COVID-19 are yet to be fully comprehended. As the understanding of origins, patterns and consequences of SARS-CoV-2-induced cytokine storm grows, it will become more apparent what subset of patients and at what disease stage could benefit the most from anti-inflammatory therapies. In parallel to the vaccine rollout, it is critical to continue investing efforts into novel treatment developments given the likelihood of variation in vaccine protection due to continuous mutations in the virus. Moreover, integrating nanoscience into re-purposing of existing targeted drugs and the development of novel molecular entities can help overcome safety and efficacy shortcomings currently associated with these therapeutics—by targeting drugs to a particular tissue in the body or by boosting synergy of combination therapies through concurrent delivery.

Data accessibility

This article does not contain any data.

Authors' contributions

N.M., F.A., E.C. and Y.O. and N.K. devised, planned, wrote and edited the paper.

Competing interests

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Chemistry, Imperial College London.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2021 WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. See https://covid19.who.int. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. 2020. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. The Lancet 395, 1033-1034. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X, et al. 2020. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 475-481. ( 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hojyo S, Uchida M, Tanaka K, Hasebe R, Tanaka Y, Murakami M, Hirano T. 2020. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 40, 1-7. ( 10.1186/s41232-020-00146-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose RJ, Manuel A. 2020. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, e46-e47. ( 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, et al. 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 395, 497-506. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, et al. 2020. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 323, 1061-1069. ( 10.1001/jama.2020.1585) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Z, et al. 2020. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 420-422. ( 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizk JG, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Mehra MR, Lavie CJ, Rizk Y, Forthal DN. 2020. Pharmaco-immunomodulatory therapy in COVID-19. Drugs 80, 1267-1292. ( 10.1007/s40265-020-01367-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCT04421027. 2020 A study of baricitinib (LY3009104) in participants with COVID-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04421027.

- 11.PUMM Center. 2021 Ruxolitinib for treatment of Covid-19 induced lung injury ARDS. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04359290 (accessed 17 January 2021).

- 12.Roschewski M, et al. 2020. Inhibition of Bruton tyrosine kinase in patients with severe COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabd0110. ( 10.1126/SCIIMMUNOL.ABD0110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson T, et al. 2020. ACCORD: a multicentre, seamless, phase 2 adaptive randomisation platform study to assess the efficacy and safety of multiple candidate agents for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalised patients: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 21, 691. ( 10.1186/s13063-020-04584-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treon SP, Castillo JJ, Skarbnik AP, Soumerai JD, Ghobrial IM, Guerrera ML, Meid K, Yang G. 2020. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib may protect against pulmonary injury in COVID-19–infected patients. Blood 135, 1912-1915. ( 10.1182/blood.2020006288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NCT04439006. 2020 Ibrutinib for the treatment of COVID-19 in patients requiring hospitalization. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04439006.

- 16.Wang CH, Chung FT, Lin SM, Huang SY, Chou CL, Lee KY, Lin TY, Kuo HP. 2014. Adjuvant treatment with a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, sirolimus, and steroids improves outcomes in patients with severe H1N1 pneumonia and acute respiratory failure. Crit. Care Med. 42, 313-321. ( 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a2727d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCT04341675. 2020 Sirolimus treatment in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04341675.

- 18.Dalamaga M, Karampela I, Mantzoros CS. 2020. Commentary: could iron chelators prove to be useful as an adjunct to COVID-19 treatment regimens? Metabolism 108, 154260. ( 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154260) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCT04488081. 2020 I-SPY COVID-19 TRIAL: an adaptive platform trial for critically ill patients. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04488081.

- 20.NCT04320615. 2020 A study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia.

- 21.NCT04327388. 2020 Sarilumab COVID-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04327388.

- 22.NCT04348500. 2020 Clazakizumab (Anti-IL- 6 Monoclonal) compared to placebo for COVID19 disease. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04348500.

- 23.NCT04330638. 2020 Treatment of COVID-19 patients with anti-interleukin drugs. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04330638.

- 24.NCT04362111. 2020 Early identification and treatment of cytokine storm syndrome in Covid-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04362111.

- 25.NCT04362813. 2020 Study of efficacy and safety of canakinumab treatment for CRS in participants with COVID-19-induced pneumonia.

- 26.NCT04447469. 2020 Study of mavrilimumab (KPL-301) in participants hospitalized with severe corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia and hyper-inflammation. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04447469.

- 27.NCT04376684. 2020 Investigating otilimab in patients with severe pulmonary COVID-19 related disease. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04376684.

- 28.NCT04351152. Phase 3 study to evaluate efficacy and safety of lenzilumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04351152.

- 29.NCT04341116. 2020 Study of TJ003234 (Anti-GM-CSF Monoclonal Antibody) in subjects with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04341116.

- 30.NCT04351243. 2020 A study to assess the efficacy and safety of gimsilumab in subjects with lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to coronavirus disease 2019. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04351243.

- 31.ChiCTR2000030089. 2020 A randomized, open-label, controlled trial for the efficacy and safety of adalimumab injection in the treatment of patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). See http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=49889.

- 32.ISRCTN33260034. 2020 Adalimumab in COVID-19 to prevent respiratory failure in community care (AVID-CC): a randomised controlled trial. See http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN33260034.

- 33.NCT04425538. 2020 A phase 2 trial of infliximab in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04425538 (accessed 17 January 2021).

- 34.NCT04324021. 2020 Efficacy and safety of emapalumab and anakinra in reducing hyperinflammation and respiratory distress in patients with COVID-19 infection. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04324021.

- 35.NCT04347226. 2020 Anti-interleukin-8 (anti-IL-8) for cancer patients with COVID-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04347226.

- 36.NCT04343651. 2020 Study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of leronlimab for mild to moderate COVID-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04343651.

- 37.NCT04347239. 2020 Study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of leronlimab for patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). See https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04347239.

- 38.Lu S, et al. 2020. Effectiveness and safety of glucocorticoids to treat COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann. Trans. Med. 8, 627. ( 10.21037/atm-20-3307) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. 2021. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 693-704. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang R, Xiong Y, Ke H, Chen T, Gao S. 2020. The role of methylprednisolone on preventing disease progression for hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 50, e13412. ( 10.1111/eci.13412) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, Wang C, Wang B, Zhou P, Dong N, Tong Q. 2020. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 57. ( 10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. 2020. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J. Infect. 80, 607-613. ( 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou D, Dai SM, Tong Q. 2020. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 1667-1670. ( 10.1093/jac/dkaa114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2020. NIH halts clinical trial of hydroxychloroquine. See https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-halts-clinical-trial-hydroxychloroquine (accessed 25 October 2020).

- 45.Borba MGS, et al. 2020. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. open 3, e208857. ( 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen AA, Habiballah SB, Platt CD, Geha RS, Chou JS, McDonald DR. 2020. Immunoglobulins in the treatment of COVID-19 infection: proceed with caution!. Clin. Immunol. 216, 108459. ( 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jawhara S. 2020. Could intravenous immunoglobulin collected from recovered coronavirus patients protect against COVID-19 and strengthen the immune system of new patients? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2272. ( 10.3390/ijms21072272) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shao Z, et al. 2020. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in critical ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 9, e1192. ( 10.1002/cti2.1192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang Y, Liu J, Zhang D, Xu Z, Ji J, Wen C. 2020. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: the current evidence and treatment strategies. Front. Immunol. 11, 1708. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01708) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen N, et al. 2020. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet 395, 507-513. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV. 2020. Interleukin-6 as a potential biomarker of COVID-19 progression. Med. Mal. Infect. 50, 382-383. ( 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu B, Li M, Zhou Z, Guan X, Xiang Y. 2020. Can we use interleukin-6 (IL-6) blockade for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-induced cytokine release syndrome (CRS)? J. Autoimmun. 111, 102452. ( 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102452) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. 2020. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55, 105954. ( 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu X, et al. 2020. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10 970-10 975. ( 10.1073/pnas.2005615117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, Liu X, Liu D, Li J. 2020. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: a single center experience. J. Med. Virol. 92, 814-818. ( 10.1002/jmv.25801) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guaraldi G, et al. 2020. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e474-e484. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price CC, et al. 2020. Tocilizumab treatment for cytokine release syndrome in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest 158, 1397-1408. ( 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu B, Xu X, Wei H. 2020. Why tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19? J. Transl. Med. 18, 164. ( 10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutherford AI, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. 2018. Serious infection across biologic-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 905-910. ( 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212825) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stone JH, et al. 2020. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2333-2344. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cavalli G, et al. 2020. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e325-e331. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30127-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dauriat G, et al. 2020. Anakinra for severe forms of COVID-19: a cohort study. Artic. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, 393-400. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30164-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luo W, Li YX, Jiang LJ, Chen Q, Wang T, Ye DW. 2020. Targeting JAK-STAT signaling to control cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 41, 531-543. ( 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cantini F, Niccoli L, Matarrese D, Nicastri E, Stobbione P, Goletti D. 2020. Baricitinib therapy in COVID-19: a pilot study on safety and clinical impact. J. Infect. 81, 318-356. ( 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao Y, et al. 2020. Ruxolitinib in treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 146, 137-146.e3. ( 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang W, et al. 2020. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin. Immunol. 214, 108393. ( 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Praveen D, Puvvada RCet al. 2020. Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib is not an ideal option for management of COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55, 105967. ( 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105967) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ngo HX, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2018. What are the drugs of the future? MedChemComm 9, 757-758. ( 10.1039/C8MD90019A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chong EA, Roeker LE, Shadman M, Davids MS, Schuster SJ, Mato AR. 2020. BTK Inhibitors in cancer patients with COVID-19: ‘The winner will be the one who controls that chaos' (Napoleon Bonaparte). Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 3514-3516. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1427) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buggy JJ, Elias L. 2012. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and its role in B-cell malignancy. Int. Rev. Immunol. 31, 119-132. ( 10.3109/08830185.2012.664797) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng Y, Li R, Liu S. 2020. Immunoregulation with mTOR inhibitors to prevent COVID-19 severity: a novel intervention strategy beyond vaccines and specific antiviral medicines. J. Med. Virol. 92, 1495-1500. ( 10.1002/jmv.26009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Terrazzano G, Rubino V, Palatucci AT, Giovazzino A, Carriero F, Ruggiero G. 2020. An open question: is it rational to inhibit the mTor-dependent pathway as COVID-19 therapy? Front. Pharmacol. 11, 856. ( 10.3389/fphar.2020.00856) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Husain A, Byrareddy SN. 2020. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Chem. Biol. Interact. 331, 109282. ( 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109282) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omarjee L, Janin A, Perrot F, Laviolle B, Meilhac O, Mahe G. 2020. Targeting T-cell senescence and cytokine storm with rapamycin to prevent severe progression in COVID-19. Clin. Immunol. 216, 108464. ( 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108464) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.NCT04461340. 2020 Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in COVID-19 infection. See https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02134221/full.

- 76.Schafer P. 2012. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 83, 1583-1590. ( 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Santaniello A, Vigone B, Beretta L. 2020. Letter to the editor: immunomodulation by phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor in COVID-19 patients. Metabolism 110, 154300. ( 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brennan FR, Morton LD, Spindeldreher S, Kiessling A, Allenspach R, Hey A, Muller PY, Frings W, Sims J. 2010. Safety and immunotoxicity assessment of immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 2, 233-255. ( 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11782) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.NCT04315298. 2020 Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of sarilumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04315298 (accessed 25 October 2020).

- 80.Ucciferri C, Auricchio A, Di Nicola M, Potere N, Abbate A, Cipollone F, Vecchiet J, Falasca K. 2020. Canakinumab in a subgroup of patients with COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e457-ee458. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30167-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stallmach A, Kortgen A, Gonnert F, Coldewey SM, Reuken P, Bauer M. 2020. Infliximab against severe COVID-19-induced cytokine storm syndrome with organ failure—a cautionary case series. Crit. Care 24, 444. ( 10.1186/s13054-020-03158-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robinson PC, Richards D, Tanner HL, Feldmann M. 2020. Accumulating evidence suggests anti-TNF therapy needs to be given trial priority in COVID-19 treatment. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e653-e655. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30309-X) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brenner EJ, et al. 2020. Corticosteroids, but not TNF antagonists, are associated with adverse COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: results from an international registry. Gastroenterology 159, 481-491.e3. ( 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gianfrancesco M, et al. 2020. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician-reported registry. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 859-866. ( 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mehta P, Porter JC, Manson JJ, Isaacs JD, Openshaw PJM, McInnes IB, Summers C, Chambers RC. 2020. Therapeutic blockade of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation: challenges and opportunities. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 822-830. ( 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30267-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Temesgen Z, et al. 2020. GM-CSF neutralization with lenzilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 95, 2382-2394. ( 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.08.038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Luca G, et al. 2020. GM-CSF blockade with mavrilimumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia and systemic hyperinflammation: a single-centre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e465-e473. ( 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30170-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rao L, et al. 2020. Decoy nanoparticles protect against COVID-19 by concurrently adsorbing viruses and inflammatory cytokines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 27 141–27 147. ( 10.1073/pnas.2014352117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dormont F, et al. 2020. Squalene-based multidrug nanoparticles for improved mitigation of uncontrolled inflammation in rodents. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz5466. ( 10.1126/sciadv.aaz5466) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haskó G, Cronstein B. 2013. Regulation of inflammation by adenosine. Front. Immunol. 4, 85. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00085) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lammers T, et al. 2020. Dexamethasone nanomedicines for COVID-19. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 622-624. ( 10.1038/s41565-020-0752-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Uskoković V. 2020. Why have nanotechnologies been underutilized in the global uprising against the coronavirus pandemic? Nanomedicine (Lond) 15, 1719-1734. ( 10.2217/nnm-2020-0163) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chauhan G, Madou MJ, Kalra S, Chopra V, Ghosh D. 2020. Nanotechnology for COVID-19: therapeutics and vaccine research. ACS Nano 14, 7760-7782. ( 10.1021/acsnano.0c04006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heinrich MA, Martina B, Prakash J. 2020. Nanomedicine strategies to target coronavirus. Nano Today 35, 100961. ( 10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100961) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article does not contain any data.