Abstract

Background

For patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the standard treatment is concurrent or sequential chemotherapy with radiotherapy. Most treatment schedules use radiotherapy with conventional fractionation; however, the application of hypofractionated radiotherapy (HYPO-RT) regimens is rising. A meta-analysis was performed to assess the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy combined with HYPO-RT and indirectly compare with the outcomes from previous studies employing concomitant conventional radiotherapy (CONV-RT).

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were identified on the electronic database sources through June 2020. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a meta-analysis was performed to assess if there were significant differences in the overall mortality (OM), local failure (LF), and disease progression (DP), comparing HYPO-RT-C vs. sequential chemotherapy followed HYPO-RT (HYPO-RT-S). To establish an indirect comparison with the current standard treatment, we calculate the risk ratio (RR) of the OM from RCTs using conventional chemoradiation, concurrent (CONV-RT-C), and sequential (CONV-RT-S), and compared with HYPO-RT. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Two RCTs with a total of 288 patients were included. The RR for the OM, DP and LF at 3 year comparing HYPO-RT-C vs. HYPO-RT-S were 1.09 (95% CI: 0.96–1.28, P=0.17), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.82–1.23, P=0.610), and 1.06 (95% CI: 0.86–1.29, P=0.490), respectively. The late grade 3 pneumonitis and esophagitis had no significant difference between HYPO-RT groups. In the indirect comparison of RCTs using CONV-RT, the RR for the OM at 3 years was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.96–1.10, P=0.36) with no significant difference for the HYPO-RT arms 1.09 (95% CI: 0.96–1.28, P=0.17).

Discussion

HYPO-RT given with chemotherapy provides satisfactory OM, LF, and DP in locally advanced NSCLC with similar rates to the CONV-RT. These findings support HYPO-RT inclusion in future clinical trials as an experimental arm in addition to the incorporation of new strategies, such as immunotherapy.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), chemoradiation (CRT), hypofractionated radiotherapy (HYPO-RT), overall survival

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality (1). It accounts for 85% cases of all histological subtypes of lung cancer (2). Most patients are diagnosed with locally advanced disease when the tumor is inoperable due to invasion of local structures and/or lymph node metastases (2).

Chemoradiation (CRT) is considered the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced NSCLC and a good clinical condition to support it (3,4). Traditionally, radiotherapy regimens employ a conventional fractionation of 1.8–2 Gy/day, with a total dose of 60–64 Gy, combined with platinum-based chemotherapy. Although a previous meta-analysis has reported a survival benefit of 5.7% in terms of overall survival (OS) with concomitant conventional CRT (CONV-RT-C) compared with sequential chemotherapy and conventional radiation (CONV-RT-S), the median survival with CONV-RT-C remains short, ranging from 14 to 17 months (2-4).

The reduced survival of patients with locally advanced NSCLC has encouraged several treatment strategies to improve oncological outcomes (2,5). However, these strategies have been associated with increased toxicity, without a clear survival benefit. For instance, in the RTOG 0617, intensification of treatment with dose-escalated radiotherapy (RT) from 60 to 74 Gy, with or without adjuvant cetuximab, was associated with a high toxicity rate without a survival benefit (6). In addition to intensification of the total radiation dose, researchers have also evaluated different fractionation schedules, such as hyperfractionated and accelerated hyperfractionated combined with or without chemotherapy to improve outcomes (7-10). Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy for NSCLC (with or without chemotherapy) was evaluated in a meta-analysis (9). The combined outcomes demonstrated an absolute survival benefit of 2.5% at 5 years compared with conventional treatment (9). However, hyperfractionation is associated with a high acute toxicity rate, increases resource use, and complicates logistics, thereby limiting its broad use (9,11,12).

Recently, several phase I and II clinical trials have been designed to combine chemotherapy with hypofractionated radiotherapy (HYPO-RT) to intensify radiotherapy in a different way (13-15). These studies have demonstrated that irradiation delivered within a short period (4 or 5 weeks) and at a radiation dose of ≥2.5 Gy per fraction combined with chemotherapy is feasible and shows encouraging outcomes (13-15). The rationale supporting CRT with HYPO-RT is to limit tumor repopulation and enhance local control with consequent survival improvement (16,17). Although it is a commonly used fractionated radiotherapy schedule in the UK (18) with strong rationale and is supported by the encouraging outcomes from phase II studies, the fear of possible severe collateral effects with HYPO-RT combined with chemotherapy has limited its utilization in clinical practice worldwide. Moreover, the absence of clinical trials directly comparing the CONV-RT vs. HYPO-RT has also contributed to the uncertainty regarding the efficacy and safety of CRT with hypofractionation (19).

Based on this background information and the encouraging findings of studies employing hypofractionation combined with chemotherapy, this meta-analysis was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of combined chemotherapy with hypofractionation and indirectly compare with the outcomes of previous CONV-RT studies.

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-573).

Methods

Electronic searches on PubMed, Embase, Scielo, and Cochrane for eligible studies published before July 1, 2020. The following keywords or medical terms were used: (“non-small cell lung carcinoma” or “non-small cell lung cancer” or “non-small cell lung neoplasms” or “lung adenocarcinoma” or “lung squamous cell carcinoma” or “large cell lung cancer”), and (“radiotherapy” or “hypofractionation” or “hypofractionated” or “accelerated hypofractionated”). We included only articles in English. Moreover, reference lists of relevant studies were manually searched for potentially eligible articles. The meta-analysis followed PRISMA guidelines recommendations (20).

Study inclusion

We included clinical trials phase II/III comparing HYPO-RT-C versus sequential chemotherapy followed HYPO-RT (HYPO-RT-S) in patients with NSCLC (T1-3/N0-N2/M0). Clinical trials phase I or phase II without a comparison between HYPO-RT-C vs. HYPO-RT-S were excluded. Retrospective studies, case reports, reviews, or studies without data were excluded.

Patients

Studies enrolling patients with inoperable NSCLC stage T1-4N0-3M0 who were randomized to receive HYPO-RT-S or HYPO-RT-C were included.

Intervention

We included studies that used radiotherapy given to patients eligible for potential curative RT at presentation; the treatments should be given sequentially or concurrently. HYPO-RT-C was considered when chemotherapy was given on the same days as RT treatment. HYPO-RT-S was considered when it was given before a course of RT but not during RT. Any chemotherapy drug combination was allowed. HYPO-RT was considered as any fractionation schedule delivering a radiotherapy dose higher than 2.1 Gy. Any radiotherapy technique such as conformational radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), or volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) was allowed.

Outcomes

The outcomes for meta-analysis were overall mortality (OM), disease progression (DP), and local failure (LF). The late maximal toxicity grade 3–5 pneumonitis and esophagitis were estimated. We also evaluated the patient’s adherence to the chemotherapy and radiotherapy protocol.

Data collection and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently selected data using a standardized method. The following information was collected: author, year, study design, stage, HYPO-RT dose, clinical characteristics (sex, age, histology, follow-up), and clinical outcomes.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis of the outcomes was performed using openmeta software. Relative risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI was used to analyze dichotomous data. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I2 index and P-value, with a P-value lower than 0.05 considered statistically significant. In the presence of heterogeneity using the fixed effect model, the random effect model was selected to estimate the outcomes. To give a view of the outcomes with HYPO-RT, we extracted the data of randomized clinical trials with the same design comparing conventional radiotherapy combined with concurrent (CONV-RT-C) versus sequential chemotherapy (CONV-RT-S). We utilized the data available from the meta-analysis performed by Aupérin et al. (4). Then, a subgroup analysis was performed, dividing the studies by HYPO-RT versus CONV-RT. The RR and 95% CI for both interventions were estimated. Data were extracted from the Kaplan Meier curve of each study using WebPlotDigitizer employing the “X Step w/interpolation” setting, and points were extracted along with regular intervals of 12 months for each curve (21). A representative survival curve for each arm HYPO-RT-C, HYPO-RT-S, CONV-RT-C, and CONV-RT-S was built to provide a better view of the differences among them. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

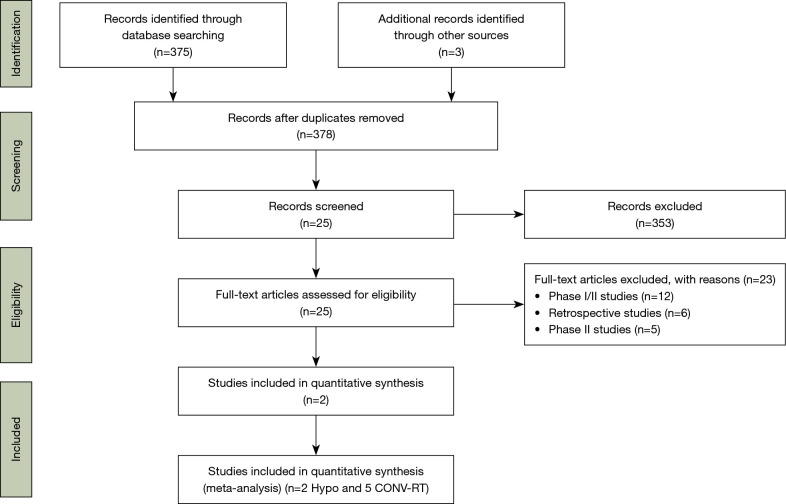

We identified in our searches 378 studies reporting the outcomes of HYPO-RT to locally advanced NSCLC. After applying the inclusion criteria, 25 studies were screened, and with full-text analysis, 23 were excluded from the meta-analysis because they were phase I (n=12), phase II (n=5), or retrospective studies (n=6) without a comparison arm (Figure 1). Thus, we selected 2 studies, including 288 patients with locally advanced NSCLC treated with HYPO-RT-C or HYPO-RT-S reporting the outcomes with a median follow-up of three years (22,23). Figure 1 describes the search strategy and the reasons for the exclusion of some studies. Both studies were randomized clinical trials (one phase II and another phase III). The patient’s characteristics were similar between the studies for age, histological subtype, clinical performance, and follow-up (Table 1). Both trials, SOCCAR and EORTC, used conformational 3D RT (22,23). Regarding the total dose, SOCCAR delivered 55 Gy with 2.75 Gy per fraction and EORTC 66 Gy with 2.75 Gy per fraction. In the SOCCAR trial, the sequential arm received cisplatin 80 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and 8 (q 21) for 3–4 cycles with RT scheduled to start four weeks after day 1 of the final cycle of chemotherapy (22). The EORTC trial employed two courses of Gemcitabine (1,250 mg/m2 days 1, 8) and Cisplatin (75 mg/m2 day 2) with a 3 weeks interval (23). In both studies, cisplatin was given concomitant with HYPO-RT (22,23).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies in the meta-analysis. CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Variables | SOCCAR (22) | EORTC (23) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HYPO-RT-C | HYPO-RT-S | HYPO-RT-C | HYPO-RT-S | ||

| Patients | 70 | 60 | 80 | 78 | |

| Age (mean) | 61 | 64 | 62 | 64 | |

| Female (%) | 36 | 33 | 26 | 22 | |

| Male (%) | 64 | 67 | 74 | 78 | |

| Clinical stage III (%) | 100 | 100 | 94 | 93 | |

| Histology (%) | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 26 | 28 | 24 | 32 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 69 | 58 | 40 | 40 | |

| Radiotherapy (Gy) | |||||

| Total dose (median) | 55 | 55 | 66 | 66 | |

| Dose/fraction (median) | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | |

| Chemotherapy | Cisplatin 20 mg/m2 was given days 1–4 and 16–19. Vinorelbine was 15 mg/m2 given days 1, 6, 15 and 20 | Cisplatin 80 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and 8 (q 21) for 3–4 cycles |

Cisplatin (6 mg/m2) 1–2 hours before each fraction |

Gemcitabine (1,250 mg/m2 days 1,8) and Cisplatin (75 mg/m2 day 2) |

|

| Follow-up, mouth (median) | 35 | 35 | 39 | 39 | |

HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy.

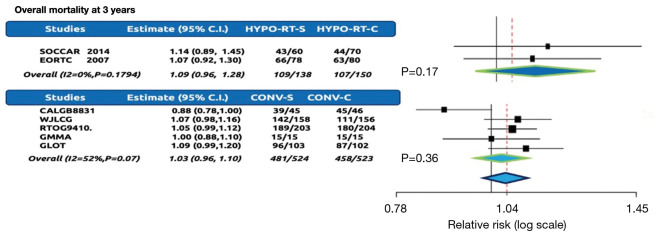

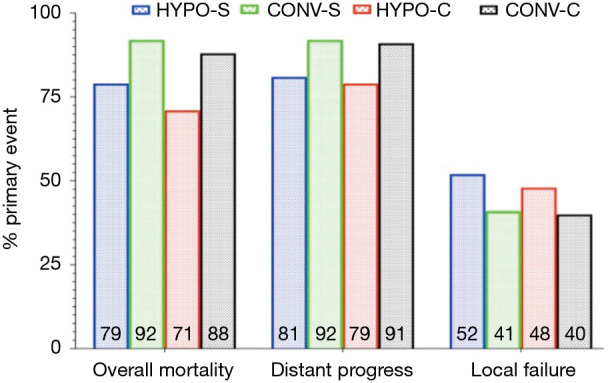

Overall mortality

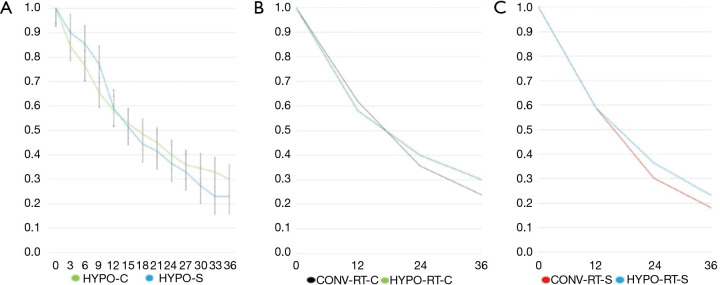

All the studies reported OM as one of the outcomes. Altogether, the analyses included 2 trials with 288 patients. The OM rates at 3 years had no significant difference comparing HYPO-RT-C arm (107/150=71%) with HYPO-RT-S arms (109/138=79%). The pooled risk ratio for all trials was 1.09 with a 95% CI of 0.96 to 1.28, P=0.1. The test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant with a P-value of 0.17, which indicates that the pooling of the data was valid. The overall risk ratio suggests no difference between HYPO-RT-C and HYPO-RT-S arms regarding the OM rate with a P-value of 0.17 (Figure 2). The RR of trials comparing CONV-RT-C arm (458/523=87.6%) with CONV-RT-S arms (481/524=92%) for OM at 3 years was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.96–1.10), no indicating significant difference between CONV-RT and HYPO-RT arms (Figure 2). The representative Kaplan-Meier curve of the rates for OS comparing HYPO-RT-C with HYPO-RT-S (Figure 3A) was extracted from each arm of studies. Figure 3B illustrates the OS with HYPO-RT-C vs. CONV-RT-C and Figure 3C the OS of HYPO-RT-S vs. CONV-RT-S.

Figure 2.

Overall mortality at 3 years with HYPO-RT and CONV-RT with sequential (S) or concomitant (C) chemotherapy. HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy; CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the survival with different radiotherapy and chemotherapy combinations. (A) A representative Kaplan-Meier curve showing the survival of patients treated by HYPO-RT with sequential (S) and concomitant (C). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of patients treated by HYPO-RT-C and CONV-RT-C. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve of patients treated with HYPO-RT-S and CONV-RT-S. HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy; CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

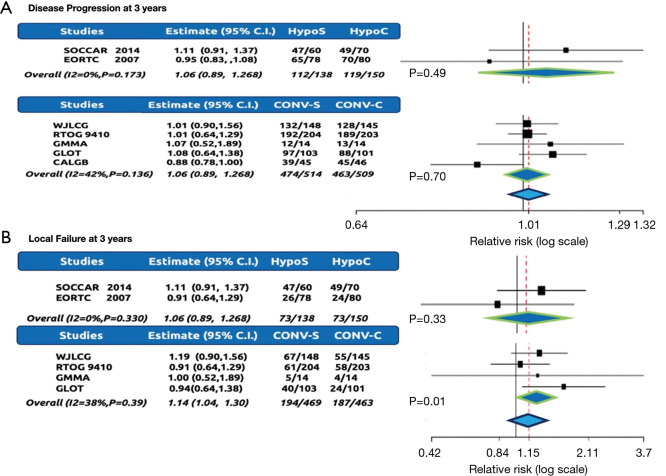

Disease progression

All studies reported DP as an outcome representing a total of 288 patients. The DP was 79% (119/150) and 81% (112/138) for HYPO-RT-C and HYPO-RT-S, respectively. The test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P=0.173), allowing the results to be pooled. The RR was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.89–1.268, P=0.49), which suggests that there was no difference for DP between the HYPO-RT-C and HYPO-RT-S (Figure 4A). The RR of trials comparing CONV-RT-C arm (91%) with CONV-RT-S arms (92%) for DP at 3 years was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.89–1.269), no indicating significant difference between CONV-RT and HYPO-RT arms (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

DP and LF at 3 years. (A) DP with HYPO-RT and concomitant CONV-RT with sequential (S) or concomitant (C) chemotherapy. B) LF with HYPO-RT and CONV-RT with sequential (S) or concomitant (C) chemotherapy. DP, disease progression; LF, local failure; HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy; CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

Local failure

All studies reported LF as an outcome representing a total of 288 patients. The LF was 48.7% (73/150) and 52.9% (73/138) for HYPO-RT-C and HYPO-RT-S, respectively. The test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P=0.33), allowing the results to be pooled. The RR was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.89–1.268, P=0.33), suggesting no difference for LF between the HYPO-RT-C and HYPO-RT-S (Figure 4B). The RR of trials comparing CONV-RT-C arm (40%) with CONV-RT-S arms (41%) for LF at 3 years was 1.14 (95% CI: 1.04–1.30), no indicating significant difference between CONV-RT and HYPO-RT arms (Figure 4B). The rates of mortality, distant progression, and LF in HYPO-RT and CONV-RT are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Overall mortality, distant progression and local failure rates in the HYPO-RT and CONV-RT arms. HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy; CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

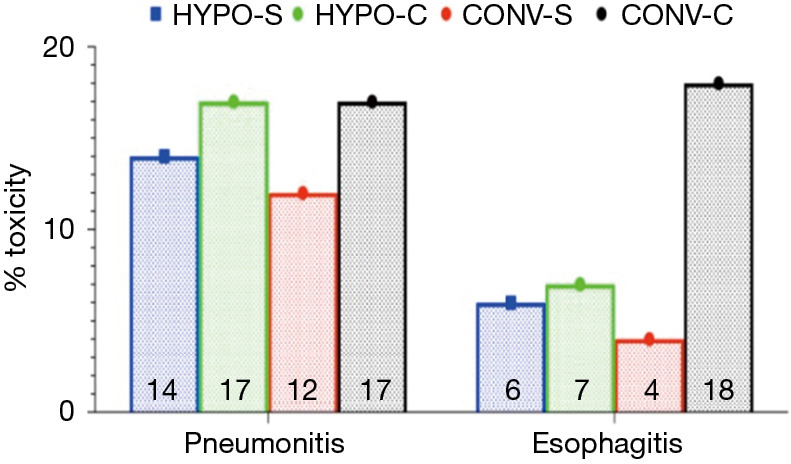

Adherence and toxicity

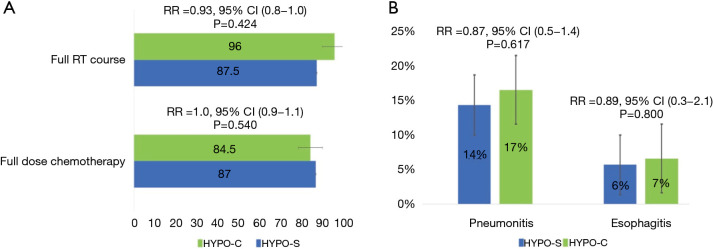

There was no difference in the full course of chemotherapy HYPO-RT-C (84.5%) vs. HYPO-RT-S (87%), RR =1 (95% CI: 0.9–1.1) or radiotherapy HYPO-RT-C (96%) vs. HYPO-RT-S (87.5%), RR =0.93 (95% CI: 0.8–1.1). Test for heterogeneity was not significant with a P-value of 0.42 (Figure 6A). The RR of late grade 3 pneumonitis comparing HYPO-RT-C (17%) vs. HYPO-RT-S (14%) was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.5–1.4, P=0.617) and grade 3 esophagitis was HYPO-RT-C (7%) vs. HYPO-RT-S (6%) with a RR =0.89 (95% CI: 0.3–2.1, P=0.80) (Figure 6B). The grade 3 or higher pneumonitis and esophagitis rates in HYPO-RT and CONV-RT is resumed in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Percentage of patients completing the planned therapy and grade ≥3 toxicities rates with HYPO-RT. (A) Percentage of patients received full-dose chemotherapy and radiotherapy in HYPO-RT arms. (B) Late grade ≥3 pneumonitis and esophagitis in HYPO-RT with sequential (S) and concomitant (C) chemotherapy. HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy.

Figure 7.

Late grade ≥3 pneumonitis and esophagitis in the HYPO-RT and CONV-RT arms with sequential (S) and concomitant (C) chemotherapy. HYPO-RT, hypofractionated radiotherapy; CONV-RT, conventional radiotherapy.

Discussion

HYPO-RT has the capability of improving local control and, consequently, overall survival (17). The high rate of NSCLC repopulation makes HYPO-RT an alternative for tackling tumor repopulation utilizing single large daily fractions in reduced treatment time (16,17). In addition, HYPO-RT has the advantage of being more convenient and attractive than CONV-RT to patients. At the same time, it can be helpful in radiotherapy services with limited capacity and resources.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of HYPO-RT combined with chemotherapy in locally advanced NSCLC. Our data showed that this approach is feasible and safe for patients, yielding outcomes similar to those of CONV-RT. The intention was not to directly compare the treatment outcomes of CONV-RT with HYPO-RT; this strategy was chosen only to establish a baseline. The rate of OM at 3 years with CONV-RT and HYPO-RT was similar, with no difference in the RR between HYPO-RT (RR =1.09) and CONV-RT (RR =1.03) (Figure 2). The overall survival rates extracted from the trials using CONV-RT and HYPO-RT with concomitant or sequential chemotherapy from the first 3 years show that HYPO-RT yielded similar outcomes, as demonstrated in Figure 3A-3C. Our data concurred with those of a recent study involving a large cohort of patients with locally advanced NSCLC who were treated with HYPO-RT-C (24). In the study, following the SOCCAR trial protocol, the authors reported a high treatment completion rate, low morbidity, and satisfactory survival (24).

A possible concern with HYPO-RT-C is the risk of increased toxicity and the consequences of interruptions or low adherence, leading to reduced survival. In total, ≥84.5% and ≥95% patients received full-dose chemotherapy and radiotherapy, respectively, without differences between concomitant and sequential arms. High adherence is an indirect measure of severe acute toxicity occurrence. As one of the trials did not provide any data on acute toxicity, adherence was used as a surrogate endpoint. However, both studies provided information on late toxicity (22,23). The estimations of late grade ≥3 toxicities considered only pneumonitis and esophagitis because they were the most frequent toxicities observed in both HYPO-RT arms. The severe pneumonitis and esophagitis rates were not significantly different between the HYPO-RT arms and were comparable to those using CONV-RT. Although an exploratory analysis of the factors from these studies in relation to the development of severe toxicity was not possible, the combination of the HYPO-RT schedule and the number of chemotherapy drugs seemed to have played a decisive role. A phase I/II trial treating 92 patients with HYPO-RT at a dose of 58.8 Gy/21 fractions (2.8 Gy/fraction, 4 weeks) with 2 cycles of CHT (cisplatin 80 mg/m2 on D1 and D22 and vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 on D1, D8, D22, and D29) and RT on D1 highlighted this point (25). Although an encouraging median survival of 38 months was achieved, 2 deaths related to treatment toxicity were reported.

Recently, a large retrospective single-institution study evaluating the role of HYPO-RT (55 Gy/20 fractions) compared to continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART, 54 Gy, 36 fractions over 12 days) was published (26). In this study, with 563 patients, 38% underwent induction chemotherapy, 57% received HYPO-RT, and 43% CHART (26). The prescribed radiotherapy treatment was completed for 99% patients (26). The median age of the patients was 71 years, and 95% PET stages were evaluated (26). The overall response rate was 50%, with a disease-free survival of 19 months and an OS of 22.5 months (26). The OS rate was 48% at 2 years (26).

In addition, Kaster et al. analyzed heterogeneous data from 33 retrospective trials on HYPO-RT and reported a moderate relationship between HYPO-RT and BED, OS, and greater acute esophageal toxicity. The study concluded some type of hypofractionation and concomitant systemic therapy should be included in the treatment of stage III NSCLC to improve outcomes (27).

Based on these and our data, it is possible to recommend a moderate fraction (2.75 Gy) with a total dose of 55 Gy combined or sequential to platinum-based chemotherapy doublets and 66 Gy with the same dose per fraction as cisplatin alone. A study exploring the relationship between the tumor volume or its proximity to the organs at risk, such as the heart and main vessels, and severe toxicity was not possible. These points were assessed in another prospective and retrospective study showing that large tumors or those centrally located in the mediastinum can have a high risk of developing severe toxicity (28). In contrast, the use of IMRT, combined with modern imaging for planning such as PET-CT, with an image guiding system (IGRT) to deliver the moderated hypofractionation has great potential to mitigate toxicities and improve the therapeutic index.

The importance of radiation doses has recently gained attention owing to the incorporation of immunotherapy in the therapeutic arsenal for NSCLC (29). The PACIFIC trial was the first randomized trial to show a possible synergistic effect leading to the benefit of progression-free survival with the incorporation of durvalumab after CRT with conventional fractionation (30). The dose per fraction may play a potential role in boosting anti-tumor immune responses (29,31-33). The initial results of the pre-clinical studies showed a profound difference in the immunological effects of the hypofractionation schedule. For example, Reits et al. showed that the expression of MHC-I and associated tumor peptides were higher with hypofractionated doses (29). Further, a high dose per fraction may lead to more significant upregulation of other stimulatory immune signals, enhancing tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell infiltration (29). In this scenario, our data provide an authentic benchmark regarding the efficacy and toxicity of CRT with HYPO-RT, which is indispensable before considering the addition of immuno-oncology agents or DNA damage response inhibitors to concurrent CRT. Currently, there is only one study registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03331575) comparing HYPO-RT-C and CONV-RT-C (34). The findings of the present meta-analysis may stimulate and support the development of further studies employing HYPO-RT.

This meta-analysis has some limitations. The study included only two trials comparing the timing of chemotherapy with HYPO-RT, and a direct comparison with CONV-RT was not possible. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provided limited data on significant factors related to the development of late severe toxicity and, thus, an exploratory analysis was not possible. However, despite these limitations, this meta-analysis provides data that strongly support the continuation and development of studies employing HYPO-RT-C for locally advanced NSCLC.

Conclusions

HYPO-RT given with chemotherapy provides satisfactory OM, LF, and DP in locally advanced NSCLC. The adherence to the full course of chemotherapy and radiotherapy was high, and the severe pneumonitis and esophagitis rates with HYPO-RT-C or S were acceptable. The indirect comparison of HYPO-RT outcomes with the standard treatment (CONV-RT) for locally advanced NSCLC suggests that HYPO-RT-C is feasible, convenient for patients, and further randomized clinical trials should consider it an experimental arm in the incorporation of new strategies, such as immunotherapy. These data can also be useful to design future clinical trials employing HYPO-RT.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-573

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-573

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-573). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puri S, Saltos A, Perez B, et al. Locally Advanced, Unresectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2020;22:31. 10.1007/s11912-020-0882-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowell NP, O'rourke NP. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD002140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aupérin A, Le Péchoux C, Rolland E, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2181-90. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajappa S, Sharma S, Prasad K. Unmet Clinical Need in the Management of Locally Advanced Unresectable Lung Cancer: Treatment Strategies to Improve Patient Outcomes. Adv Ther 2019;36:563-78. 10.1007/s12325-019-0876-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley JD, Hu C, Komaki RR, et al. Long-Term Results of NRG Oncology RTOG 0617: Standard- Versus High-Dose Chemoradiotherapy With or Without Cetuximab for Unresectable Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:706-14. 10.1200/JCO.19.01162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders M, Dische S, Barrett A, et al. Continuous, hyperfractionated, accelerated radiotherapy (CHART) versus conventional radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: mature data from the randomised multicentre trial. CHART Steering committee. Radiother Oncol 1999;52:137-48. 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann M, Herrmann T, Koch R, et al. Final results of the randomized phase III CHARTWEL-trial (ARO 97-1) comparing hyperfractionated-accelerated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Radiother Oncol 2011;100:76-85. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauguen A, Le Péchoux C, Saunders MI, et al. Hyperfractionated or Accelerated Radiotherapy in Lung Cancer: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2788-97. 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatton M, Nankivell M, Lyn E, et al. Induction chemotherapy and continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (chart) for patients with locally advanced inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer: the MRC INCH randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:712-8. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Din OS, Harden SV, Hudson E, et al. Accelerated hypo-fractionated radiotherapy for non small cell lung cancer: results from 4 UK centres. Radiother Oncol 2013;109:8-12. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pemberton LS, Din OS, Fisher PM, et al. Accelerated radical radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer using two common regimens: a single-centre retrospective study of outcome. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:161-7. 10.1016/j.clon.2008.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy S, Pathy S, Mohanti BK, et al. Accelerated hypofractionated radiotherapy with concomitant chemotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of lung: evaluation of response, survival, toxicity and quality of life from a Phase II randomized study. Br J Radiol 2016;89:20150966. 10.1259/bjr.20150966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bearz A, Minatel E, Rumeileh IA, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with tomotherapy in locally advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: a phase I, docetaxel dose-escalation study, with hypofractionated radiation regimen. BMC Cancer 2013;13:513. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbanic JJ, Wang X, Bogart JA, et al. Phase 1 Study of Accelerated Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy With Concurrent Chemotherapy for Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: CALGB 31102 (Alliance). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;101:177-85. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramroth J, Cutter DJ, Darby SC, et al. Dose and Fractionation in Radiation Therapy of Curative Intent for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;96:736-47. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler JF. Biological factors influencing optimum fractionation in radiation therapy. Acta Oncol 2001;40:712-7. 10.1080/02841860152619124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prewett SL, Aslam S, Williams MV, et al. The management of lung cancer: a UK survey of oncologists. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:402-9. 10.1016/j.clon.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faivre-Finn C. Dose escalation in lung cancer: have we gone full circle? Lancet Oncol 2015;16:125-7. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70001-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WebPlotDigitizer - Extract data from plots, images, and maps. Accessed February 12, 2021. Available online: https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/

- 22.Maguire J, Khan I, McMenemin R, et al. SOCCAR: A randomised phase II trial comparing sequential versus concurrent chemotherapy and radical hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients with inoperable stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and good performance status. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:2939-49. 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belderbos J, Uitterhoeve L, van Zandwijk N, et al. Randomised trial of sequential versus concurrent chemo-radiotherapy in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer (EORTC 08972-22973). Eur J Cancer 2007;43:114-21. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal MS, Vashisht G, McMenemin R, et al. Hypofractionated Concomitant Chemoradiation in Inoperable Locally Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Report on 100 Patients and a Systematic Review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2019;31:e1-e10. 10.1016/j.clon.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glinski K, Socha J, Wasilewska-Tesluk E, et al. Accelerated hypofractionated radiotherapy with concurrent full dose chemotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase I/II study. Radiother Oncol 2020;148:174-80. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson SD, Tahir BA, Absalom KAR, et al. Radical accelerated radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A 5-year retrospective review of two dose fractionation schedules. Radiother Oncol 2020;143:37-43. 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaster TS, Yaremko B, Palma DA, et al. Radical-intent hypofractionated radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Lung Cancer 2015;16:71-9. 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming C, Cagney DN, O'Keeffe S, et al. Normal tissue considerations and dose-volume constraints in the moderately hypofractionated treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2016;119:423-31. 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006;203:1259-71. 10.1084/jem.20052494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1919-29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaue D, Ratikan JA, Iwamoto KS, et al. Maximizing tumor immunity with fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:1306-10. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kachikwu EL, Iwamoto KS, Liao YP, et al. Radiation enhances regulatory T cell representation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:1128-35. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weichselbaum RR, Liang H, Deng L, et al. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a beneficial liaison? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:365-79. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu X. Hypofractionated vs. Conventionally Fractionated Concurrent CRT for Unresectable Stage III NSCLC. clinicaltrials.gov; 2017. Accessed August 11, 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03331575

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as