Abstract

Aging is a complex phenomenon associated with a wide spectrum of physical and physiological changes affecting every part of all metazoans, if they escape death prior to reaching maturity. Critical to survival, the immune system evolved as the principal component of response to injury and defense against pathogen invasions. Because how significantly immune system affects and is affected by aging, several neologisms now appear to encapsulate these reciprocal relationships, such as Immunosenescence. The central part of Immunosenescence is Inflammaging –a sustained, low-grade, sterile inflammation occurring after reaching reproductive prime. Once initiated, the impact of Inflammaging and its adverse effects determine the direction and magnitudes of further Inflammaging. In this article, we review the nature of this vicious cycle, we will propose that phytocannabinoids as immune regulators may possess the potential as effective adjunctive therapies to slow and, in certain cases, reverse the pathologic senescence to permit a more healthy aging.

Keywords: Inflammaging, Cannabinoids, CBD, Aging, Inflammation, Cannabis, Microbiome

1. Introduction

It was over two decades ago when Claudio Franceschi first introduced the term ”Inflammaging” to describe how aging increases the susceptibility of the host organism to a wide spectrum of diseases (Claudio et al., 2018b, 2017a). Inflammaging, defined as an age-dependent, chronic, low-grade inflammation, is characterized by elevated inflammatory indices including, but not limited to, pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNFα, IFNγ, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, IL-22), chemokines, and inflammatory factors (CCL5, MCP, CRP) (Paola et al., 2016). The maximum length of time an organism can live is lifespan while the average length of time a particular group actually lives is defined as life expectancy. Because the aging process occurs after the reproductive period, natural selection plays a smaller, secondary role, allowing the accumulation of many deleterious genes that would have been eliminated if their effects manifested earlier in life. The high prevalence of degenerative diseases in the human population attest to this fact. Thus, aging is an inevitable, natural, intricate consequence of increased longevity.

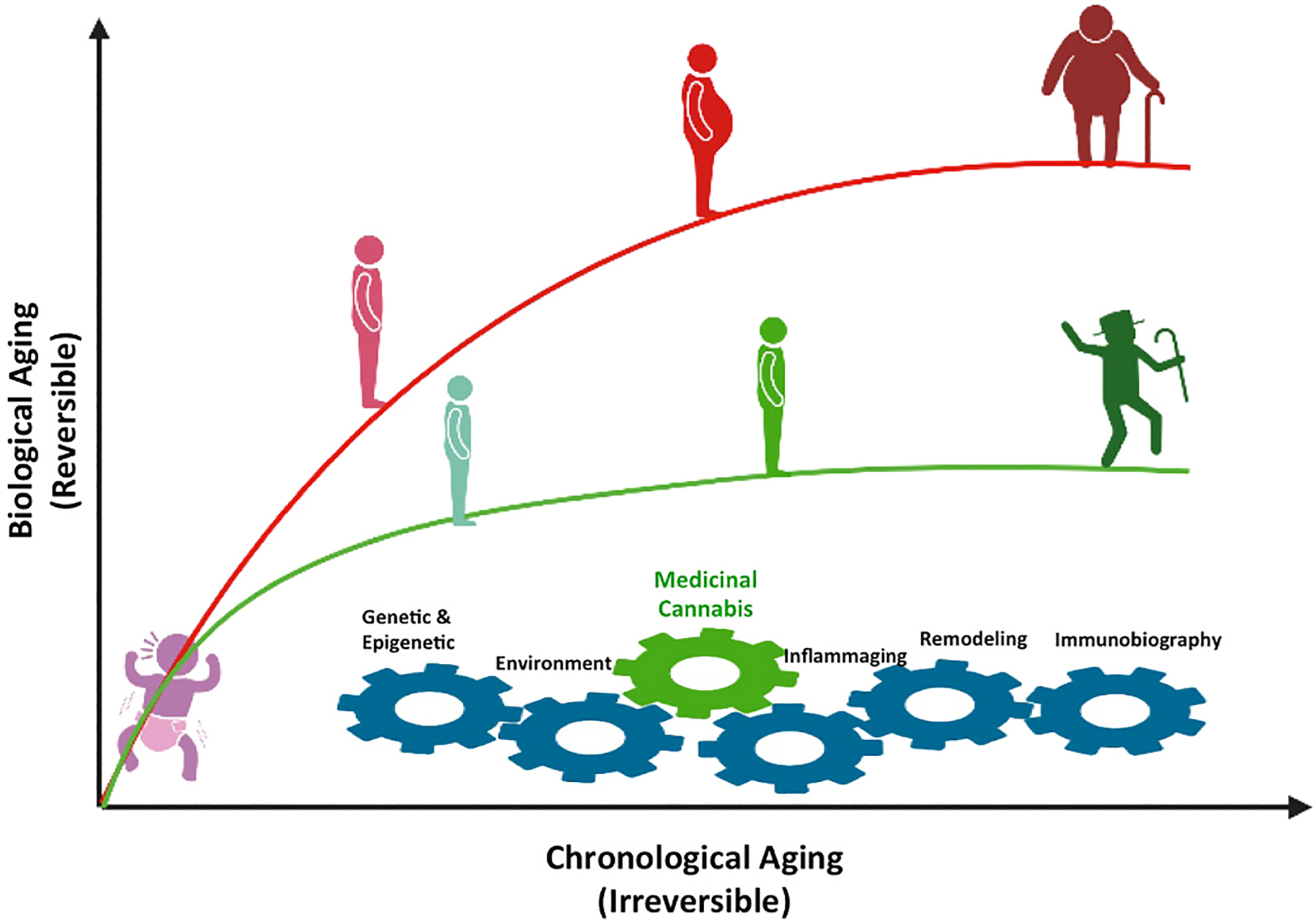

Inflammation is obligatory for host survival; however, chronic inflammation may be deleterious in the context of aging. Therefore, a holistic understanding of inflammaging is imperative to examine the principles of inflammation during old age through the eyes of “geroscience”. Gero-scientists classify aging into two categories: “Chronological” and “Biological” aging. While chronological aging is a “non-reversible” process, biological aging is a controllable and theoretically reversible process (Beltrán-Sánchez et al., 2015; Bret et al., 2017; Robin, 2004; Kelci et al., 2021). In this mini-review, we summarize basic concepts related to inflammaging within the paradigm of aging and immunosenescence. We also explore the medicinal potential of phytocannabinoids, such as cannabidiol (CBD) (Zurier and Burstein, 2016; Angelo and Izzo, 2009; Khodadadi et al., 2020; Salles et al., 2020), which may counter the deleterious effects of immune activation to promote healthy biological aging (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Aging, contributing factors and Inflammaging. A combination of genetic, physiologic and environmental variables may affect the process of aging and age-dependent inflammatory responses, Inflammaging. While chronologic aging is irreversible, interventional strategies, such as medicinal cannabis, may control the biological aging, delay and ideally prevent the adversarial symptoms of Inflammaging (Created with BioRender.com).

2. Aging and the immune system

Aging is a complex, natural phenomenon that occurs in all metazoans. It is the inevitable extension from maturation and reproduction into senescence and eventually death. As metazoans approach the end of their life expectancy or the limit of their life span, multiple biological, physical, and chemical impairments accumulate, challenging the continued living of these “old” organisms (Beltrán-Sánchez et al., 2015; Bret et al., 2017; Robin, 2004). Aging progressively perturbs the homeostasis and functional capacity of the individual, often creating multiple vicious feed-forward cycles leading to unfavorable outcomes through impairment of vital dynamics as well as damaging the body’s infrastructure (Vetrano et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Amir, 2018; Chen et al., 2020; Bonafè et al., 2020). While not a disease, aging is a major risk factor for most chronic diseases and pathologic conditions (Teresa and Linda, 2012; Irene et al., 2018; Claudio et al., 2018a). Importantly, the influence of aging is general, occurring through the entire body with no exception, including the immune system (Claudio et al., 2017a, 2018a; Amir, 2018). The immune system is one of the main principles required for human survival. It is crucial for the maintenance of bio-integrity, protecting the host against pathogens as well as resolving undesirable non-infectious conditions and disorders resulting from accidental injuries.

The relationship between Immune system and aging is intricate, but remains incompletely understood. Numerous studies support the notion that the “inflammation” is the main link between the immune system and aging (Claudio et al., 2017a; Cornelia and Goronzy; Luigi and Elisa, 2018; Olivieri et al., 2018). Inflammation is the major part of innate immunity, protecting the organism and contributing to tissue repair and homeostasis. Inflammatory responses are beneficial only if triggered in an acute and regulated fashion, with timely resolution to prevent inappropriate tissue damage. However, chronic inflammation, beyond the initial injury or assaulting signals, may cause life-long debilitating illness, increased mortality and high costs for therapy and care. The key factor in switching from a regulated acute inflammatory response to an uncontrolled and chronic destructive cascade of interactions is “the immune balance” or immunobalance. The immune balance is the equipoise between pro- and counter-inflammatory reactions responsible for the status of immune responses. Aging is one of the major factor affecting immunobalance and plays an essential role in the direction and function of immune system. Therefore, “Immunosenescence”, the age-related alterations of Immune system, results in a profound changes in immune responses, affecting homeostasis and all systems of the host organism.

3. Anti-aging strategies: the concept of “successful aging”

Significant increases in human life expectancy has necessitated novel strategies to allow individuals to enjoy an extended, healthy life without serious, debilitating, painful age-related diseases (Roger and Wong, 2018; Urtamo et al., 2019; Ingunn et al., 2019). In response, the objectives of age-related research have shifted from extending length of life to enhancing health span and quality of life. In the 1960 s, Havighurst presented the utilitarian theory of “Successful aging”, from a population perspective, as the principle of the greatest good for the greatest number (Urtamo et al., 2019; Robert, 1961). Due to the complexity of aging, there is no definitive description for successful aging. However, the most accepted definition of “Successful aging” was delineated by Rowe and Kahn, characterizing the concept of “Successful aging” as the functional status in later life span (EDITOR’S CHOICE, 2015). Accordingly, the functional status translates to the high physical, psychological, and social operational mode in old age with no major pathologic condition or disability (Roger and Wong, 2018; Urtamo et al., 2019; Nancy and Hans-Werner, 2016). Despite the inclusion of psychologic and social factors, the concept of “Successful Aging” widely relies on physiologic variables, measuring by functional criteria and healthy aging (Urtamo et al., 2019; Editor’s choice, 2015; Nancy and Hans-Werner, 2016). Therefore, to achieve the standards of successful aging, it is imperative to have a strategy by which extended life expectancy is associated with long stable health and higher quality of life with a shortened period of illness just before death.

4. Immunosenescence and Inflammaging

Inflammaging is an intrinsic component of Immunosenescence, which itself is one of the outcomes of aging (Claudio et al., 2018b; Luigi and Elisa, 2018; Olivieri et al., 2018; Tamas et al., 2018; Weili et al., 2020). Although the majority of studies have focused on the pathologic aspects of Inflammaging, there exists a need for multi-dimensional approaches beyond merely the gerontologic perspective (Claudio et al., 2017a; Tamas et al., 2018; Weili et al., 2020; Franceschi et al., 2020; Leane et al., 2021; Hae et al., 2019). This new perspective has been conceptualized in the context of larger scheme of recently described theory of aging (Shijin et al., 2016; Kirkwood, 2018). According to the new scenario, Inflammaging is a cascade of adaptive responses occurring as a result of natural aging and in relation to immunosenescence. Specifically, as aging affects the immune system, inflammaging develops as a central core of immunosenescence. Inflammaging is a “remodeling” mechanism to respond to changes and challenges faced by the organism due to general aging. This adaptive remodeling is influenced by a series of primary and secondary factors collectively called “Immunobiography” (Claudio et al., 2017b), which play a central role in determining the type, magnitude, and direction of age-related adaptation during senescence. Immunobiography is the history of immune responses produced by individuals during their lifetime. This chronicle plays a crucial role in predicting an individual’s immune reactions to various stimuli and biological assaults, based on historic immunologic records, particularly in relation to inflammaging and during immunosenescence. In fact, the Immunobiography presents a solid and reasonable platform to explain the diversity of responses to age-related effects and the heterogeneity of inflammaging and the outcomes of Immunosenescence (Claudio et al., 2017a, 2017b). Importantly, the concept of immunobiography and its effects on immunosenescence is more meaningful when considered in relation to categorical division of Chronological versus Biological aging. While chronologic aging (actual amount of time a person has been alive) is irreversible, biological aging is variable and dependent on the immunobiography trajectory of the individual. Cellular and molecular interactions (e.g., mitochondrial function, nuclear factor signaling, intracellular stress, degradation of telomeres, cytokines/mitokines/chemokines, damage associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMP) etc.) and their lifetime productions called “Garb-aging”, genetic/epigenetic factors, metabolic and general health status, as well as lifestyle and environmental stress are examples of mechanisms by which immune system can become dysregulated (Claudio et al., 2017a, 2017b; Franceschi et al., 2020; Hae et al., 2019; Shijin et al., 2016; Kirkwood, 2018). These alterations of the immune system induce a marked level of accumulated pro-inflammatory proteins, which may have a determinant role in the polarization of Inflammaging from a benign, adaptive “remodeling” breeze to a severe destructive “inflammatory” tsunami. Consequently, the theory of “Immuno-networking” was propounded to represent a dynamic scheme, rendering a more profound definition of inflammaging. According to the Immuno-networking theory, the lifetime aggregation of immune products (cellular and humoral) caused by a network of infective and non-infective stimuli, metabolic and physiologic phenomena (e.g., Reactive Oxygen Species, Apoptosis, Autophagy, Mitochondrial damages) as well as genetic and epigenetic factors would be the central organizing point of aging. The accumulation of all these elements together dictates the direction of inflammaging and its magnitude as a central component of immunosenescence during aging.

5. The dichotomous nature of Inflammaging: the key to successful aging

Inflammaging has two complex elements: inflammation and aging. While inflammaging is considered the main triggering factor for the majority of age-related diseases, it is also a remodeling strategy by which organism can adapt to the age-induced alterations. The association between aging and dysregulation of major biological responses is well established (Claudio et al., 2017b; David et al., 2019; Joana and Pedro, 2020). As an organism ages, Intrinsic and extrinsic factors cause tissue injury, leading to inflammatory responses. While acute and regulated inflammation is crucial for survival, sustained and excessive inflammatory responses are destructive and serve as the major underlying causes of age-related diseases. Inflammaging is defined as a low-grade, sterile, chronic and unresolved inflammatory status during aging. Therefore, targeting inflammaging as a therapeutic target for age-related diseases has become a central focus of several studies investigating the link between Inflammaging and age-related diseases.

Aging is characterized by higher frequencies and more impactful assaults on tissues, causing alterations in physiologic functions including skewing of the immune system. Environmental assaults and ensuing tissue injuries cause cellular stress and elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial dysfunction, higher incidence of DNA damage, shortened telomeres, increased apoptosis, dysregulation of cellular plasticity and elevated vascular and endothelial permeability. These changes initiate the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) as part of the DNA Damage Response in senescent cells (Matt et al., 2021; Daniela et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2010, 2019; Gianluca et al., 2021; Bezzerri et al., 2019). Activation of SASP induces inflammatory responses which under normal conditions would be a transient event, regulated by anti-inflammatory mechanisms and resulting in a re-establishment of baseline homeostasis. However, with aging, similar to all other bio-systems in the body, the immune system undergoes a series of significant changes described as immunosenescence. Under immunosenescence, the immune responses to the accumulated cellular stress and assault during aging are manifested as inflammaging. Under normal condition and during pre-senescence period of life, inflammation is a regulated process following stress and tissue injury, providing an optimal micro-environment for host defense, cellular repair, restoring homeostasis and tissue integrity. However, as an intrinsic part of the immunosenescence paradigm and based on age-related physiological decline, inflammaging may be evident by dysregulated and chronic inflammatory reactions manifested by sustained low grade immune responses causing further phenotypic alterations and tissue damages (Franceschi et al., 2020; Claudio et al., 2017b; David et al., 2019; Fabiola et al., 2015; Simon et al., 2015; Claudio and Judith, 2014). Therefore, the subset of a potent and active counter inflammatory mechanism is an exigent requirement for “successful aging”.

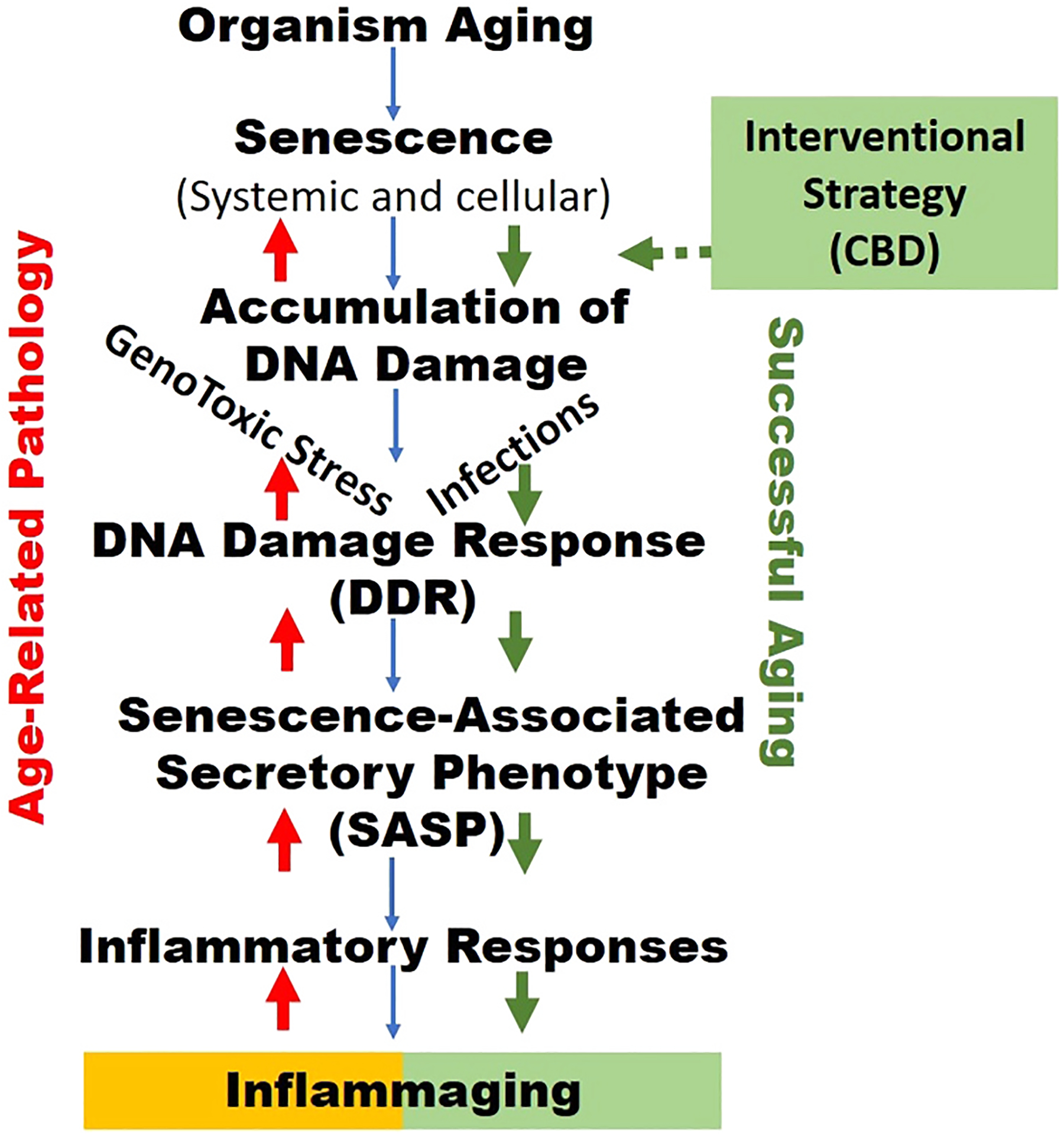

Overall, Inflammaging can be conceptualized as an immunologic interchange characterized by mild but sustained inflammation, triggering imbalance between “damage and repair”, remodeling the immune responses in an age-dependent fashion. Inflammation is the first line of defense with a significant impact on the host integrity and function. This vital role of inflammation is more important during aging when there is a generalized decline in every organ/system. Therefore, any interventional strategy to control the adverse symptoms of inflammaging should be concentrated on “Immuno-regulation” rather than “Immuno-suppression”. By re-establishing the balance between inflammatory and counter inflammatory signals, the equation will move towards more repair than damage. This beneficial development results in “successful aging”, characterized by reduced ROS, decreased DNA damage, lower numbers of senescent cells, less mitochondrial dysfunction, and an increased level of autophagy and homeostasis (Fig. 2), until the end-of-life expectancy.

Fig. 2.

Medicinal Cannabis and Successful aging. Aging process is intensified by accumulation of DNA damages, higher stress and excessive DNA Damage Repair (DDR) mechanisms causing Inflammaging and uncontrolled inflammatory responses during old ages of life. Using alternative therapeutic strategies such as medicinal cannabis may be beneficial through re-establishment of homeostasis and Immunobalance. Equalizing the inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory responses will reverse the devastating effects of Inflammaging, pathologic aging, towards the more normal and less inflammatory status, signs of successful aging.

6. Medicinal cannabis and inflammaging

The use of cannabinoids in the treatment of diseases goes back to ancient times (Baron, 2015; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017). However, the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic value of cannabis and cannabinoids were initially described in the last several decades (Natalya, 2007; Khodadadi et al., 2021; Atakan, 2012). A more in depth understanding of the endocannabinoid system in the early 1990 s increased interest in characterizating the dynamics of cannabis and its derivatives in treating diseases and pathologic conditions (Valerio et al., 2018; Reddy et al., 2020). Since then, and particularly during the last decade, the concept of “Medicinal Cannabis” has become the focus of numerous studies and clinical trials to explore the potentially beneficial effects of cannabis as alternative modalities in the clinical setting to treat diseases.

Age induces senescence which is manifested by significant alteration of the body’s bio-dynamics. Inflammaging is a direct consequence of senescence, identified by low-grade chronic inflammation resulting from the imbalance of immune system, a major contributing factor of many age-related disorders. Chronic inflammation is the excessive pro-inflammatory reactions triggered by a dysregulated immune system. Numerous studies support the Immuno-modulatory features of certain cannabinoids. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that some cannabinoids such as Cannabidiol (CBD) and Cannabichromene (CBC) may have the potential to modulate the immune responses, prevent the adverse effects of Inflammaging and promote healthy aging.

7. Cannabinoids and aging: natural synergy and intrinsic preponderance

Aging is associated with gradual and autonomous physiological declines, accompanied by structural and functional changes occurring in a systematic manner (López-Otín et al., 2013; Neves and Sousa-Victor, 2020). The most focus of anti-aging mechanisms is currently targeting pathological symptoms of aging organisms (Neves and Sousa-Victor, 2020; Palmer et al., 2019; Belsky et al., 2015). However, the desirable interventional anti-aging strategy is to defer, reverse or ideally block this process of aging. Therefore, it is a dire requirement for exploring novel anti-aging approaches not only to treat the adversarial effects of aging, but also establish a paradigm towards full spectrum of a healthy life and successful aging.

Cannabinoids have been suggested to be effective counter-aging compounds by modulating several aging factors (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017; Marchalant et al., 2009; Pryimak et al., 2020). Regulation of inflammatory responses, normalization of circadian rhythm, suppression of oxidative stress (antioxidant effects), anxiolytic properties, and repression of ROS/RNS (reactive nitrogen species) are examples of such anti-aging properties of cannabinoids (Table 1). Importantly, several studies have identified dysfunctional circadian rhythms as a biomarker for aging (Duffy et al., 2015; Hood and Amir, 2017; Hodges and Ashpole, 2019). It has been reported that phytocannabinoids have potential to improve and normalize circadian rhythms through activation of endocannabioid system in aged animals (Hodges and Ashpole, 2019; Kesner and Lovinger, 2020). Interactive relationship between endocannabinoid systems and phytocannabinois may be potentially beneficial for the host, restoring normal circadian rhythms, proposing cannabinoids as new source of modalities against aging. Compared with other natural and synthetic plant based cannabinoids, due to extensive presence of endocannabinoids in the body, therefore, cannabinoids can be therapeutically targeted to reduce the impact of aging and ameliorate the symptoms of age-related disease, contributing to healthy and successful aging.

Table 1.

Potential anti-aging effects of Cannabinoids and levels of evidence for efficacy.

| Anti-aging Features of Cannabinoids | Aging Conditions/Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Regulating the inflammation (Modulation of Inflammaging) | Pain***, Neurodegenerative Diseases*/**/*** Seizures*** Cardiovascular complications*/** Ocular conditions* Mobility issues*/**/*** Wound Healing*/** Cancer*/** Inflammatory Bowl Disease**/*** |

| Anti-oxidative and anti-oxidant | Skin health**/***, Pain***

Wound healing */**, Mobility issues*/**/*** Digestion***, Sleep** |

| Dietary health and improvement | Cancer patients and appetite complications**/*** Microbiome maintenance**/*** Inflammatory Bowl Disease**/*** Exercise and rehabilitation*** |

Level of efficacy evidence: *** Conclusive/Significant **Moderate *Limited.

8. Oxidative stress and inflammaging: the potential protective and anti-aging roles for CBD

Inflammation is a major functional component of Immune system, playing a central role in human health and survival. The regulation of inflammatory responses, a balance between initiation and resolution, called immunobalance, is the key for a beneficial and effective inflammatory paradigm. Oxidized compounds are one of the main products accrued from inflammatory reactions with the capacity to affect the immune balance (Tarique et al., 2016; Nemat et al., 2009; Rosa et al., 2019; Roberts and Sindhu, 2009). The impact of oxidized molecules and oxidation reactions goes beyond immune system, influencing physio-metabolic interactions, cellular signaling, differentiation and replication (Rosa et al., 2019; Roberts and Sindhu, 2009; Soazig et al., 2014). During early years of life until advanced age, the body remains in a “redox balance” status (oxidative equipoise). Under redox balance, the production of oxidative compounds including reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (RONS) and free radicals are equal to or less than the neutralization of RONS and other free radicals detoxification (Poljsak and Milisav, 2013; Liguori et al., 2018). The interruption of such balance elicits “oxidative stress” condition. As a damage control strategy and to re-establish the redox balance, living cells deploy a battery of enzymatic (e.g., superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, catalases) and/or non- enzymatic (e.g., vitamins C & E, certain natural compounds, plant polyphenol, carotenoids) mechanisms, known collectively as “Oxidant defense” (Poljsak and Milisav, 2013; Liguori et al., 2018; Warraich et al., 2020; Daniel et al., 2014; Márcio et al., 2018). In fact, the correlation between oxidative stress and defense is molding the principles of “Oxidative-theory” of aging (Romero Cabrera, 2016; Gladyshev, 2014). Originally expressed by Harman, based on the oxidative theory of aging, excessive production and accumulation of oxidative stress and lack of sufficient oxidative defense would induce damage, accelerating the aging process and causing age-related pathological condition (Gladyshev, 2014; Viña et al., 2013). Inflammaging is the first clinical manifestation of such disarrays, determined by multiple variables including, but not limited to, host Immunobiography, genetic background and epigenetic factors, collectively contribute to the state of inflammaging as the source of chronic inflammation and the aging catalyst. Under oxidative stress, the aging phenomenon would be associated with a form of Inflammaging characterized by severe cellular and tissue damages due to excessive DNA damage, heightened apoptosis, shortened telomeres and elevated amount of oxidized macromolecules and free radicals. Inflammaging and significance of oxidative stress during aging accentuate the need for more effective and non-invasive interventional therapeutic modalities for prevention and slowing the aging process.

Cannabinoids are chemical compounds found in natural forms as phytocannabinoids (within Cannabis plant), and endocannabinoids produced inside human body (known as endogenous cannabinoid compounds), or in synthetic form, artificially produced (Baron, 2015). Cannabinoids and their derivatives have been investigated extensively for their potential beneficial effects, most importantly their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant features (Khodadadi et al., 2020; Salles et al., 2020; Atakan, 2012). Through binding to specific membrane-bound receptors, cannabinoids can modulate the redox reactions effectively. The most investigated phytocannabinoids are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD). THC is a psychoactive agent, affecting the host mainly through binding to CB1R (endocannabinoid receptor 1). Although many studies have shown beneficial effects of THC in several conditions including aging, the adverse symptoms, mainly related to THC’s euphoric effects, have diverted a significant volume of research and attention towards CBD.

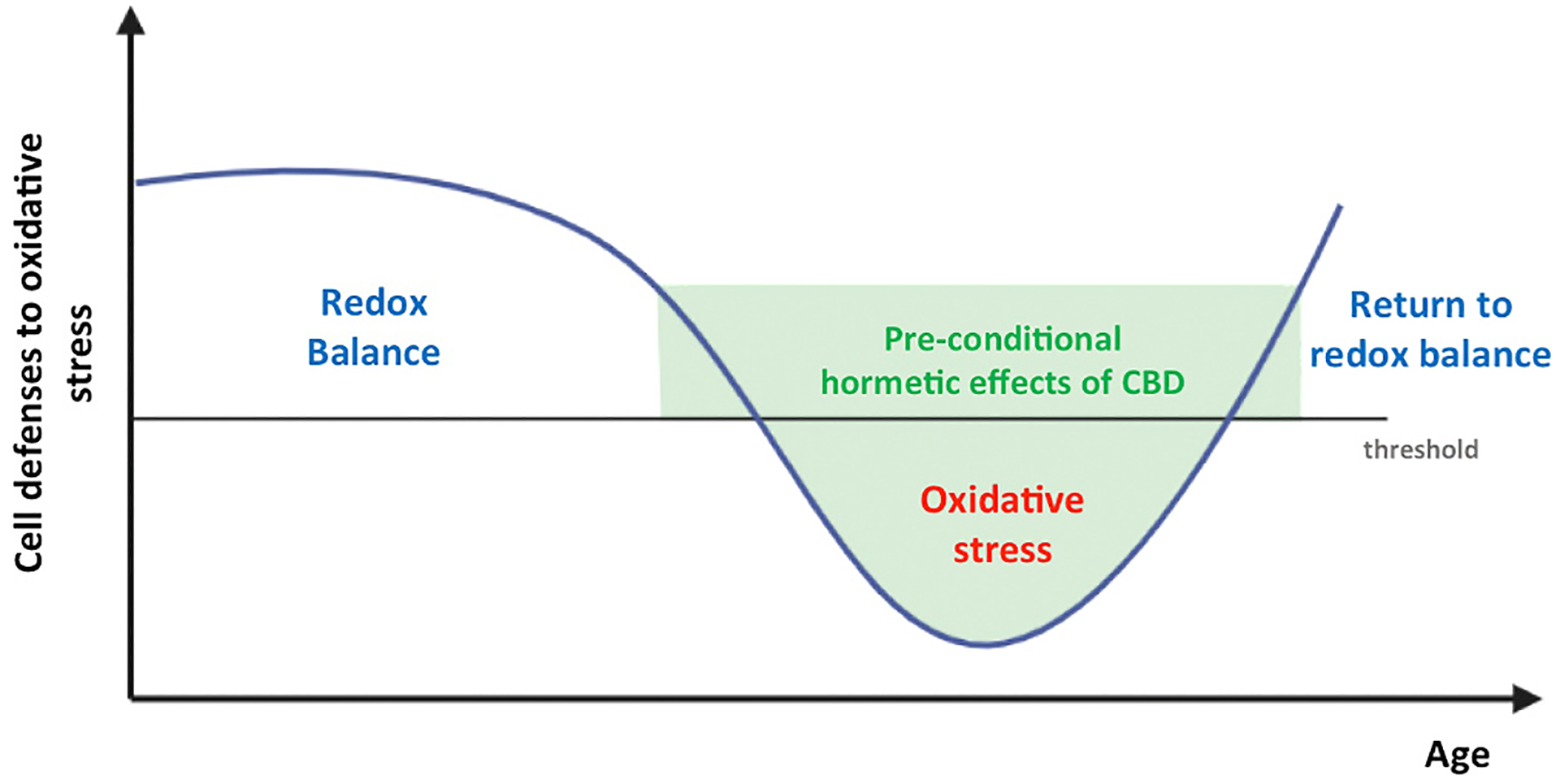

CBD does not bind to CB1R and is only a weak agonist for CB2R, but several studies have shown that CBD interaction with CB2R results in reduction of RONS level and reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6 as well as inhibition of the transcriptional factor, NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), collectively curtailing oxidative stress and mitigating Inflammaging effects. Importantly, there are several other membrane-bound receptors through which CBD can alter the redox balance, modulate inflammatory responses, prevent further DNA damage and contain destructive features of inflammaging (Viña et al., 2013; Sinemyiz et al., 2019; O’Sullivan, 2016). The transient receptor potential (TRPs) superfamily receptors are proteins acting as ion channels including TRPC (canonical), TRPV (vanilloid), TRPM (melastatin), TRPP (polycystin), TRPML (mucolipin) and TRPA (ankyrin). TRPs are ubiquitously presented in the body, reflecting their crucial role in metabolic and physiologic paradigms and ion homeostasis within cells and tissues. Several studies have shown that the ligation of CBD to TRPV1 down-regulated oxidant stress, restored immunomodulation, and decreased apoptosis. The interactions of CBD with several other receptors including TRPA1, G-protein coupled receptors (GPR3, GPR6 and GPR12), serotonin 1 A receptor (5-HT1A), adenosine A2A receptor (ADORA2A), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) may be potential mechanism for antioxidant and counter-inflammatory functions of CBD (Sinemyiz et al., 2019; O’Sullivan, 2016; Lowin and Straub, 2015; Iannotti and Vitale, 2021; James and Barbara; Turcotte et al., 2015). Interestingly, CBD antagonistic relationship with GPR55 and TRPM8 have resulted in higher production of Th2 and anti-inflammatory cytokines, limiting the inflammatory damages, slow aging and re-establish homeostasis (Lowin and Straub, 2015; Anavi-Goffer et al., 2012; Nina et al., 2020; Zacharias et al., 2020). Therefore, the potential of CBD engagement with these receptors individually or in a chimeric and combined fashion may be targeted as a non-invasive interventional modality, delaying the aging process and confining the inflammaging and consequential damages. These potential effects of CBD in re-establishing homeostasis of the redox balance may be achieved via a pre-conditioning signal, through a hormetic process (Fig. 3). Hormesis is a biphasic dose-response relationship characterized by low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition (Calabrese et al., 2020, 2010, 1996, 2021; Siracusa et al., 2020; Miquel et al., 2018). Briefly, low doses of a pharmacologic agent would promote beneficial effects, but when the dose exceeds a certain threshold, the effects would be deleterious (Calabrese et al., 1996). The nature of this dynamic mechanism is type of bio-recalibration, enabling the organism to acquire resilience and protection against subsequent noxious stimuli (Brunetti et al., 2020). The use of CBD at low doses and in a determined old-age period could induce a pre-conditional signal (Calabrese et al., 2020) reestablishing the cell oxidative defense through the mechanisms as described (Calabrese et al., 2020, 2010, 1996, 2021; Siracusa et al., 2020; Miquel et al., 2018; Brunetti et al., 2020). Whether the beneficial effects of CBD including anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant features root in a hormetic basis, remain to be elucidated through further research (Hodges and Ashpole, 2019).

Fig. 3.

The image illustrates the window of beneficial and hermetic effects of low doses of CBD (green). The use of low doses of CBD would recalibrate cells to oxidative stress, re-establishing the redox balance. This process also would enable cells to acquire resilience to oxidative stress and maintain balance. The threshold represents the limit of the oxidative balance, the moment in which the production of oxidative compounds including reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (RONS) and free radicals are equal to the neutralization of RONS and other free radicals’ detoxification.

9. DNA damage and inflammaging: the potential protective role for CBD

The DNA damage is imputed to any alteration to the basic structure of DNA molecule, making it different from the original DNA molecule (Matt et al., 2021). These changes can result in cellular injuries, affecting vital functions of organism negatively. Metazoans possess a complex mechanistic network to recognize and repair DNA damage, re-establishing the genomic stability and cellular integrity. While early detection of DNA damage and DNA Damage Repair (DDR) is vital for survival, perpetuated DNA damage and DDR represent “genotoxic stress”, affecting cellular genetic code and affect genome stability negatively (Matt et al., 2021; Gianluca et al., 2021; Fabiola et al., 2015; Clementi et al., 2020). In fact, the interactive paradigm between DNA damage and DDR has been proposed as one of the viable theories of aging (Matt et al., 2021; Maynard et al., 2015). Accordingly, excessive DDR intensifies the cellular senescence and triggers the chronic sterile inflammation. This uncharted senescence and chronic inflammatory responses result in repression of cell cycle, mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic increase in RONS, heighten p53 activation, altered cellular metabolism and morphology (Matt et al., 2021; Gianluca et al., 2021; Hitomi et al., 2020). One of the major functional changes due to the chronic DNA damage is the modification of SASP (Matt et al., 2021; Hitomi et al., 2020). Depending on the nature of genotoxic inducer, the SASP plays a crucial role in initiating a pro-inflammatory response, promoting inflammatory indices including cytokines, chemokines and a diverse range of inflammatory factors and inducers of additional senescence (Olivieri et al., 2018; Matt et al., 2021; da Silva and Schumacher, 2019). This shift of inflammatory plateau may disturb the cellular homeostasis, shifting it towards the chronic status of Inflammaging with potential local and systemic adversarial consequences. Inflammaging is the central core for the development of Immunosenescence, therefore it is the ideal target to explore new therapeutic modalities to prevent and treat the potential pernicious impact of Inflammaging on the body. Since inflammaging is a chronic phenomenon, adopting any limiting strategy must be safe with minimal side effects for long-term use. Given antioxidant and modulatory functions of certain cannabinoids in particular CBD, they may be considered as alternative anti-aging modalities. The anti-inflammatory feature of CBD would advance its potentials beyond re-calibration of inflammaging, affecting metabolic and physiologic network in a protective fashion. Regulation of SASP, influencing the mitochondrial membrane potential, modulating AMPK (5’ AMP-activated protein kinase, an enzyme with crucial role in cellular energy homeostasis) activation, adjustment of ion trafficking and glucose uptake, neutralizing free radicals are all examples of mechanisms by which CBD may have the capacity to minimize DNA damages (Anavi-Goffer et al., 2012; Nina et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2017). Considering all these protective measures individually or combined together, entitle CBD and certain cannabinoids to be targeted as an alternative anti-aging therapeutic modality, affecting inflammaging, preventing age-related diseases and promoting cell plasticity and survival. Further research is warranted.

10. Microbiome and inflammaging: the potential protective role for CBD

Increasing evidence show the significance of microbiome and its biological values in human health (Vogelzang et al., 2018; Bosco and Noti, 2021). Aging-induced changes alter major functional systems in the body, affecting microbiome and its bidirectional relationship with the host significantly (Bosco and Noti, 2021; Tomasz et al., 2020; Kim and Benayoun, 2020). Considering the interaction between microbiome and immune system, it is evident that age-dependent gradation of either side would affect the reciprocal interplay between them. Alteration in composition, function, metabolic output, phenotype and diversity of microbiome are examples of major age-dependent changes with a profound impact on the Immune-balance and homeostasis. These changes in microbiome would promote inflammaging, resulting in heightened inflammatory responses with excessive adverse symptoms to the host. On the other side, Immunosenescence elicits a set of alterations in the immunoprofile of the host, known as inflammaging, including chronic pro-inflammatory reactions associated with skew from lymphoid to myeloid system, elevated RONS production, increased oxidative stress, apoptosis, and higher incidence and severity of age-related diseases. Decline in function is the other side of the Aging coin. Senescence-induced dysfunction affects the tolerogenic and symbiotic relationship between microbiome and Immune system, which may result in severe immunopathogenesis and autoimmune diseases.

Numerous preclinical data indicate that cannabinoids may play a crucial role in re-establishing the balance and symbiosis between microbiota and immune system, restoring the homeostasis and the foundation for a successful aging paradigm (Cani et al., 2016; Iannotti and Di Marzo, 2021; Geurts et al., 2011). The immunomodulatory characteristics of cannabinoids and specifically CBD may be used not only to reduce the excessive inflammatory impact of inflammaging, but also to influence the microbiome through antioxidant potential, providing the optimal conditions for the growth and dominance of beneficial members of microbiome in a protective fashion. Interestingly, microbiota may affect the endocannabinoid system, regulating the digestive tract permeability and reducing the inflammatory signaling (Lee et al., 2016; DiPatrizio, 2016). Importantly, CBD is a natural phytocannabinoid with minimal known toxicity and side effects. Considering the digestive tract as the main site of the largest microbiota in the body, it is plausible to suggest a dietary regiment including CBD as a pragmatic and relatively safe interventional strategy to target the inflammaging, reversing the pathologic symptoms of aging and its potential pernicious side effects.

11. Safety implications and interactions of therapeutic cannabinoids

Despite increasing research on efficacy of cannabinoids and their potential as therapeutic modalities for a wide range of conditions, there is still a dearth of certainty on the safety of cannabinoids use and applications in clinical settings (Gottschling et al., 2020; MacCallum et al., 2021; Sachs et al., 2015; Kurlyandchik et al., 2021; Sohn, 2019). This ambiguity is mainly a source of concern when cannabinoid-based medicines are used by patients rather than by healthy individuals. Lack of sufficient understanding, particularly in distinguishing the characteristics of medicinal from recreational cannabis, using appropriate chemovar (strain), routes of administration, and dosing are examples of important factors to be considered when medicinal cannabis is recommended (Gottschling et al., 2020; MacCallum et al., 2021; Sachs et al., 2015; Kurlyandchik et al., 2021; Sohn, 2019; Wang et al., 2008).

There are several studies suggesting that age and duration of use may influence the efficacy and any potential adversarial side effects of medicinal cannabis (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Fontes et al., 2011; Lorenzetti et al., 2020; Levine et al., 2017). Several investigations have recommended additional considerations when medicinal cannabis is used in younger patients under age 25 (Levine et al., 2017; Parekh et al., 2020; Gorey et al., 2019). This is due to a potential risk of long-term cognitive effects (Kurlyandchik et al., 2021; Sohn, 2019; Levine et al., 2017; Parekh et al., 2020; Gorey et al., 2019). However, cannabinoid-based medicine has shown beneficial effects in children with severe nausea and vomiting resulted from chemotherapy (Chao and McCormack, 2019; Rower et al., 2021). Therefore, for every individual, an evidence-based recommendation in a personalized fashion maybe the most desirable approach in prescribing medicinal cannabis to avoid any potential side effects (Freeman et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2021). Further, while numerous studies support the safety and tolerability of cannabinoid-based medicine in older individuals (aged<50), however, a careful consideration should be given prior to using medicinal cannabis in these individuals (Pisani et al., 2021; Velayudhan et al., 2021). This is because of potential morbidity and complications based on individual’s poor health conditions, compromised cardiovascular, respiratory, or immune systems(Pisani et al., 2021; Velayudhan et al., 2021). These cautionary actions would also apply to those who are pregnant (Navarrete et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2020).

Overall, the short-term use of medicinal cannabis seems relatively safe, tolerable and effective (Pisani et al., 2021). However, similar to all other type of medications, medicinal cannabis may contain certain level of unrealized risks particularly in long-term users. These potential adverse effects may be more prominent in adolescents and vulnerable individuals including those with current or history of particular illnesses and those who are pregnant (Pisani et al., 2021; Navarrete et al., 2020). Therefore, further discussion between the physician and the patient as well as more careful considerations and detailed screening for any drug interactions is highly recommended prior to any use of medicinal cannabis.

12. Mode of administration, dosing strategies and drug interactions

12.1. Mode of administration

Cannabinoids are taken through different routs. Inhalation (smoking/vaporization) and ingestion (Oral) are the most common ways of administration. Oromucosal and topical are examples of other methods of administration with less prevalence, followed by rectal, sublingual, transdermal, eye drops, and aerosols which have been used rarely in only a few studies with least significance in practice today (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017).

Each mode of delivery has its specific characteristics affecting the administration factors including onset and duration of effects. While Inhalation has the fastest onset time (5–10 min), it shows the shortest duration period (2–4 h) compared to oromucosal (15–45 min of onset and 6–8 h of duration) followed by oral method (1–3 h of onset time and 6–8 h of duration). Onset time represents the period which cannabinoids are concentrated in the plasma and duration time is when the cannabinoids are attained their highest effects before their efficacy decline within few hours. Given the rapid onset time, Inhalation is considered as an effective method for treating pain and nausea. However, factors such as cost, usage difficulties (depth of inhalation, breath holding), size of chamber and strength of cannabinoids in the chemovar are all examples of some of disadvantages of inhalation. On the other hand, oral route is more convenient method with less odor to apply, particularly for chronic diseases. However, slower onset timing may cause inaccuracy in final dose and solubility. Several reports have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of oromucosal method. However, cost and universal availability are major factors affecting oromucosal route negatively. The therapeutic effects of topical approach is limited by localized and non-systemic impact. The topical administration has a variable values depending on the ingredients as well as skin structure and other metabolic/environmental conditions (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017).

12.2. Dosing strategies

Cannabinoid-based medications may be used during day or at bedtime depending on the symptoms. As a starting base line, it is recommended to start THC with 2.5 mg once per day for the first 1–2 days and increase it to twice a day by third and fourth days. If tolerated, it can be increased to 15 mg either twice or third times a day. Doses higher than 20–30 mg may cause ineffectiveness (desensitization) with increased side effects (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017).

For CBD, there is no standard dose and it varies for every individuals depending on symptoms and physical conditions such as weight and metabolic status. In general, CBD causes less side effects compared to THC. Depending on physical conditions and route of administration, a starting dose between 5 and 30 mg of CBD per day has been beneficial. There are reports of using very high dose of CBD in particular cases, 800 mg in psychosis and 2500 mg (25–50 mg/kg) for seizure disorders (MacCallum and Russo, 2018; Bridgeman and Abazia, 2017; Busse et al., 2021).

12.3. Drug interactions

There is still insufficient data on any potential interactions between cannabinoids and other pharmaceuticals during their concomitant administration. Several studies have reported bidirectional interactions between cannabinoids and other pharmaceutical agents, leading to lower or higher serum concentration of cannabinoids (Antoniou et al., 2020; Cox et al., 2019). Simultaneous administration of cannabinoids (CBD and THC) with rifampin resulted in reduction of those cannabinoid levels, while concurrent use of cannabinoids and CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole resulted in significantly higher concentrations of CBD and THC (Cox et al., 2019; Alsherbiny and Li, 2018; Nasrin et al., 2021). Therefore, additional considerations should be given to any potential interaction between cannabinoids and other medications, especially for individuals with pathologic and chronic conditions and elderly.

13. Concluding remarks

Aging is an inevitable, natural, and complex phenomenon, reshaping the global demographics significantly. By 2025, an estimated 1.2 billion individuals worldwide will be over sixty years of age, with that number doubling by 2050 (Aiello et al., 2019); yet, this remarkable shift in life expectancy does not synchronize with healthspan. Aging and its influences on the body’s declining vital bio-systems are blamed for this incoordination. Given the central role of immune system in human survival, the impact of aging on innate and adaptive immunity has emerged as one of the main focus areas of anti-aging measures and investigations. Inflammaging, a potentially underlying cause for a significant number of age-related diseases, has rationalized anti-inflammatory interventional protocols as therapeutic strategies to slow, limit and/or reverse the adversarial symptoms of aging, closing the gap between increase in lifespan and its lopsided ratio with healthspan.

In recent years, the anti-inflammatory features of cannabinoids have been demonstrated repeatedly through vigorous pre-clinical studies and, to a less extend, by clinical trials. Among a variety of cannabinoids, CBD has shown the most potential as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. This is due to CBD’s non-psychotropic nature, relative safety, low toxicity and its modulatory effects on several pro-inflammatory signals. Given the existing urgency in exploring reliable and effective therapeutic modalities to reverse the aging symptoms and inflammaging, cannabinoids and specifically CBD appear as potential potent compounds to be targeted as part of anti-aging therapeutic regimen. With the increasing interest in CBD by public, industry and scientific community, further research to document and to better understand beneficial effects of CBD and its potential contribution to a healthy successful aging is both reasonable and necessary.

Funding

This work was partially supported by funding provided by awards from the National Institute of Health (NIH), USA (NS110378 to KMD/BB, and NS114560 to KV).

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors have contributed in writing this article by providing insight and conceptual input as well as editing advice. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, Ligotti ME, Zareian N, Accardi G, 2019. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Front. Immunol 10, 2247. September 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsherbiny MA, Li CG, 2018. Medicinal cannabis-potential drug interactions. Medicines 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir A. Sadighi Akha, 2018. Aging and the immune system: an overview. J. Immunol. Methods 463, 21–26 (December). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anavi-Goffer S, Baillie G, Irving AJ, et al. , 2012. Modulation of L-α lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling by cannabinoids. J. Biol. Chem 287 (1), 91–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo A, Izzo Michael Camilleri, 2009. Cannabinoids in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Pharm. Res 60 (2), 117–125 (August). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JM, 2020. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ 192 (9), E206. March 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atakan Z, 2012. Cannabis, a complex plant: different compounds and different effects on individuals. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol 2 (6), 241–254 (December). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron EP, 2015. Comprehensive review of medicinal marijuana, cannabinoids, and therapeutic implications in medicine and headache: what a long strange trip it’s been. Headache 55 (6), 885–916 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R, Cohen HJ, Corcoran DL, Danese A, Harrington H, Israel S, Levine ME, Schaefer JD, Sugden K, Williams B, Yashin AI, Poulton R, Moffitt TE, 2015. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112 (30), E4104–E4110. July 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Sánchez H, Soneji S, Crimmins EM, 2015. Past, present, and future of healthy life expectancy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 5 (11), a025957. November 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzerri V, Piacenza F, Caporelli N, Malavolta M, Provinciali M, Cipolli M, 2019. Is cellular senescence involved in cystic fibrosis? Respir. Res 20 (1), 32. February 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafè M, Prattichizzo F, Giuliani A, Storci G, Sabbatinelli J, Olivieri F, 2020. Inflamm-aging: why older men are the most susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 complicated outcomes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 53, 33–37 (June). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco N, Noti M, 2021. The aging gut microbiome and its impact on host immunity. Genes Immun. 10.1038/s41435-021-00126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bret R.Rutherford, Warren D.Taylor, Patrick J.Brown, Joel R.Sneed, Steven P.Roose, 2017. Biological aging and the future of geriatric psychiatry. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 72 (3), 343–352. March 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeman MB, Abazia DT, 2017. Medicinal cannabis: history, pharmacology, and implications for the acute care setting. P&T 42 (3), 180–188 (March). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti G, Di Rosa G, Scuto M, Leri M, Stefani M, Schmitz-Linneweber C, Calabrese V, Saul N, 2020. Healthspan maintenance and prevention of parkinson’s-like phenotypes with hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein Aglycone in C. elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21 (7), 2588. April 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse JW, Vankrunkelsven P, Zeng L, Heen AF, Merglen A, Campbell F, Granan LP, Aertgeerts B, Buchbinder R, Coen M, Juurlink D, Samer C, Siemieniuk RAC, Kumar N, Cooper L, Brown J, Lytvyn L, Zeraatkar D, Wang L, Guyatt GH, Vandvik PO, Agoritsas T, 2021. Medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 374, n2040. September 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP, Dhawan G, Kapoor R, Calabrese V, Giordano J, 2020. Hormesis: a potential strategic approach to the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol 155, 271–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Calabrese V, Giordano J, 2021. Demonstrated hormetic mechanisms putatively subserve riluzole-induced effects in neuroprotection against amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): implications for research and clinical practice. Ageing Res. Rev 67, 101273 (May). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Renis M, Calderone A, Russo A, Barcellona ML, Rizza V, 1996. Stress proteins and SH-groups in oxidant-induced cell damage after acute ethanol administration in rat. Free Radic. Biol. Med 20 (3), 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP, 2010. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal 13 (11), 1763–1811. December 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Plovier H, Van Hul M, Geurts L, Delzenne NM, Druart C, Everard A, 2016. Endocannabinoids–at the crossroads between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 12 (3), 133–143 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao YS, McCormack S, 2019. Medicinal and Synthetic Cannabinoids for Pediatric Patients: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Ottawa (ON). October 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kelley WJ, Goldstein DR, 2020. Role of aging and the immune response to respiratory viral infections: potential implications for COVID-19. J. Immunol 205 (2), 313–320. July 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio Franceschi, Judith Campisi, 2014. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 69 (1), S4–S9 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio Franceschi, Paolo Garagnani, Giovanni Vitale, Miriam Capri, Stefano Salvioli, 2017a. Inflammaging and ‘Garb-aging’. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 28 (3), 199–212 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio Franceschi, Stefano Salvioli, Paolo Garagnani, Magda de Eguileor Daniela, Monti Miriam, Capri, 2017b. Immunobiography and the heterogeneity of immune responses in the elderly: a focus on inflammaging and trained immunity. Front. Immunol 8, 982. August 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio Franceschi, Paolo Garagnani, Cristina Morsiani, Maria Conte, Aurelia Santoro, Andrea Grignolio, Daniela Monti, Miriam Capri, Stefano Salvioli, 2018a. The continuum of aging and age-related diseases: common mechanisms but different rates. Front. Med 5, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio Franceschi, Paolo Garagnani, Paolo Parini, Cristina Giuliani, Aurelia Santoro, 2018b. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 14 (10), 576–590 (October). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi E, Inglin L, Beebe E, et al. , 2020. Persistent DNA damage triggers activation of the integrated stress response to promote cell survival under nutrient restriction. BMC Biol. 18, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelia M. Weyand, J.örg J. Goronzy, Aging of the Immune System: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets, Transatlantic Airway Conference,AnnalsATS Volume 13 Supplement 5. [Google Scholar]

- Cox EJ, Maharao N, Patilea-Vrana G, Unadkat JD, Rettie AE, McCune JS, Paine MF, 2019. A marijuana-drug interaction primer: precipitants, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics. Pharm. Ther 201, 25–38 (September). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva PFL, Schumacher B, 2019. DNA damage responses in ageing. Open Biol. 9 (11), 190168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Ortuño-Sahagún, Mercè Pallàs, Argelia E.Rojas-Mayorquín, 2014. Oxidative stress in aging: advances in proteomic approaches. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev vol, 18. Article ID 573208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniela Frasca, Bonnie B.Blomberg, Roberto Paganelli, 2017. Aging, obesity, and inflammatory age-related diseases. Front. Immunol 8, 1745. December 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David Furman, Judith Campisi, Eric Verdin, Pedro Carrera-Bastos, Sasha Targ, Claudio Franceschi, Luigi Ferrucci, Derek W.Gilroy, Alessio Fasano, Gary W. Miller, Andrew H.Miller, Alberto Mantovani, Cornelia M.Weyand, Nir Barzilai, Jorg J.Goronzy, Thomas A.Rando, Rita B.Effros, Alejandro Lucia,Nicole Kleinstreuer, George M.Slavich, 2019. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med 25, 1822–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, Lee T, Weber JT, Bugden S, 2020. Cannabis use in pregnancy and breastfeeding: the pharmacist’s role. Can. Pharm. J 153 (2), 95–100. January 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPatrizio NV, 2016. Endocannabinoids in the gut. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 1 (1), 67–77 (February). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Zitting KM, Chinoy ED, 2015. Aging and circadian rhythms. Sleep Med. Clin 10 (4), 423–434 (December). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editor’s choice, 2015. Successful aging: contentious past, productive future (February). Gerontologist 55 (1), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiola Olivieri, Maria Cristina Albertini, Monia Orciani, Artan Ceka, Monica Cricca, Antonio Domenico Procopio, Massimiliano Bonafè, 2015. DNA damage response (DDR) and senescence: shuttled inflamma-miRNAs on the stage of inflamm-aging. Oncotarget 6 (34), 35509–35521. November 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes MA, Bolla KI, Cunha PJ, Almeida PP, Jungerman F, Laranjeira RR, Bressan RA, Lacerda AL, 2011. Cannabis use before age 15 and subsequent executive functioning. Br. J. Psychiatry 198 (6), 442–447 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Santoro A, Capri M, 2020. The complex relationship between immunosenescence and inflammaging: special issue on the new biomedical perspectives. Semin. Immunopathol 42 (5), 517–520 (October). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TP, Hindocha C, Green SF, Bloomfield MAP, 2019. Medicinal use of cannabis based products and cannabinoids. BMJ 365, l1141. April 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts L, Lazarevic V, Derrien M, Everard A, Van Roye M, Knauf C, Valet P, Girard M, Muccioli GG, François P, de Vos WM, Schrenzel J, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, 2011. Altered gut microbiota and endocannabinoid system tone in obese and diabetic leptin-resistant mice: impact on apelin regulation in adipose tissue. Front. Microbiol 2, 149. July 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianluca Storci, Francesca Bonifazi, Paolo Garagnani, Fabiola Olivieri, Massimiliano Bonafè, 2021. The role of extracellular DNA in COVID-19: clues from inflamm-aging. Ageing Res. Rev 66, 101234 (March). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev VN, 2014. The free radical theory of aging is dead. Long live the damage theory! Antioxid. Redox Signal 20 (4), 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey C, Kuhns L, Smaragdi E, Kroon E, Cousijn J, 2019. Age-related differences in the impact of cannabis use on the brain and cognition: a systematic review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci 269 (1), 37–58 (February). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling S, Ayonrinde O, Bhaskar A, Blockman M, D’Agnone O, Schecter D, Suárez Rodríguez LD, Yafai S, Cyr C, 2020. Safety considerations in cannabinoid-based medicine. Int. J. Gen. Med 13, 1317–1333. December 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hae Young Chung, Dae Hyun Kim, Eun Kyeong Lee, Ki Wung Chung, Sangwoon Chung, Bonggi Lee, Arnold Y.Seo, Jae Heun Chung, Young Suk Jung, Eunok Im, Jaewon Lee, Nam Deuk Kim, Yeon Ja. Choi, Dong Soon Im, Byung Pal Yu, 2019. Redefining chronic inflammation in aging and age-related diseases: proposal of the senoinflammation concept. Aging Dis. 10 (2), 367–382. April 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi K, Okada R, Loo TM, Miyata K, Nakamura AJ, Takahashi A, 2020. DNA damage regulates senescence-associated extracellular vesicle release via the ceramide pathway to prevent excessive inflammatory responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21 (10), 3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EL, Ashpole NM, 2019. Aging circadian rhythms and cannabinoids. Neurobiol. Aging 79, 110–118 (July). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood S, Amir S, 2017. The aging clock: circadian rhythms and later life. J. Clin. Investig 127 (2), 437–446. February 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti FA, Di Marzo V, 2021. The gut microbiome, endocannabinoids and metabolic disorders. J. Endocrinol 248 (2), R83–R97 (February). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti FA, Vitale RM, 2021. The endocannabinoid system and PPARs: focus on their signalling crosstalk, action and transcriptional regulation. Cells 10 (3), 586. March 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingunn Bosnes, Hans Morten Nordahl, Eystein Stordal, Ole Bosnes, Tor Åge Myklebust, Ove Almkvist, 2019. Lifestyle predictors of successful aging: A 20-year prospective HUNT study. PLoS One 14 (7), e0219200. July 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irene Maeve Rea, David S.Gibson, Victoria Mc.Gilligan, Susan E.Mc.Nerlan, H Denis Alexander, Owen A.Ross, 2018. Age and age-related diseases: role of inflammation triggers and cytokines. Front. Immunol 9, 586. April 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. Nichols, Barbara L.F. Kaplan, Immune Responses Regulated by Cannabidiol., Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research., Vol. 5, No. 1 Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joana Neves, Pedro Sousa-Victor, 2020. Regulation of inflammation as an anti-aging intervention. FEBS J. 287 (1), 43–52 (January). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelci Straka, Mai-Lan Tran, Summer Millwood, James Swanson, Kate Ryan Kuhlman, 2021. Aging as a context for the role of inflammation in depressive symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 11, 605347. January 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner AJ, Lovinger DM, 2020. Cannabinoids, endocannabinoids and sleep. Front. Mol. Neurosci 13, 125. July 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi H, Salles ÉL, Jarrahi A, Chibane F, Costigliola V, Yu JC, Vaibhav K, Hess DC, Dhandapani KM, Baban B, 2020. Cannabidiol modulates cytokine storm in acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by simulated viral infection using synthetic RNA. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 5 (3), 197–201. September 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi H, Salles ÉL, Jarrahi A, Costigliola V, Khan MB, Yu JC, Morgan JC, Hess DC, Vaibhav K, Dhandapani KM, Baban B, 2021. Cannabidiol ameliorates cognitive function via regulation of IL-33 and TREM2 upregulation in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis 80 (3), 973–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Benayoun BA, 2020. The microbiome: an emerging key player in aging and longevity. Transl. Med. Aging 4, 103–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood KL, 2018. Inflammaging. Immunol. Investig 47 (8), 770–773 (November). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlyandchik I, Tiralongo E, Schloss J, 2021. Safety and efficacy of medicinal cannabis in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review. J. Altern. Complement. Med 27 (3), 198–213 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leane Perim Rodrigues, Vitória Rodrigues Teixeira, Thuany Alencar-Silva, Bianca Simonassi-Paiva, Rinaldo Wellerson Pereira, Robert Pogue, Juliana Lott Carvalho, 2021. Hallmarks of aging and immunosenescence: connecting the dots. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 59, 9–21 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Jo J, Chung HY, Pothoulakis C, Im E, 2016. Endocannabinoids in the gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 311 (4), G655–G666. October 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Clemenza K, Rynn M, Lieberman J, 2017. Evidence for the risks and consequences of adolescent cannabis exposure. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56 (3), 214–225 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang Z, Ren Y, Wang Y, Fang J, Yue H, Ma S, Guan F, 2021. Aging and age-related diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology 22 (2), 165–187 (April). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, 2018. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Published 2018 Apr 26. doi Clin. Inter. Aging 13, 757–772. 10.2147/CIA.S158513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G, 2013. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153 (6), 1194–1217. June 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti V, Hoch E, Hall W, 2020. Adolescent cannabis use, cognition, brain health and educational outcomes: A review of the evidence. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 169–180 (July). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowin T, Straub RH, 2015. Cannabinoid-based drugs targeting CB1 and TRPV1, the sympathetic nervous system, and arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther 17 (1), 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luigi Ferrucci, Elisa Fabbri, 2018. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 15 (9), 505–522 (September). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum CA, Russo EB, 2018. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. Eur. J. Intern. Med 49, 12–19 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum CA, Lo LA, Boivin M, 2021. “Is medical cannabis safe for my patients?” A practical review of cannabis safety considerations. Eur. J. Intern. Med 89, 10–18 (July). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchalant Y, Brothers HM, Norman GJ, Karelina K, DeVries AC, Wenk GL, 2009. Cannabinoids attenuate the effects of aging upon neuroinflammation and neurogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis 34 (2), 300–307 (May). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Márcio Carocho, Isabel C.F.R.Ferreira, Patricia Morales, Marina Soković., 2018. Antioxidants and prooxidants: effects on health and aging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev [Google Scholar]

- Matt Yousefzadeh, Chathurika Henpita, Rajesh Vyas, Carolina Soto-Palma, Paul Robbins, Laura Niedernhofer, 2021. DNA damage—How and why we age? eLife 10, e62852.33512317 [Google Scholar]

- Maynard S, Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Croteau DL, Bohr VA, 2015. DNA damage, DNA repair, aging, and neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 5 (10), a025130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel S, Champ C, Day J, Aarts E, Bahr BA, Bakker M, Bánáti D, Calabrese V, Cederholm T, Cryan J, Dye L, Farrimond JA, Korosi A, Layé S, Maudsley S, Milenkovic D, Mohajeri MH, Sijben J, Solomon A, Spencer JPE, Thuret S, Vanden Berghe W, Vauzour D, Vellas B, Wesnes K, Willatts P, Wittenberg R, Geurts L, 2018. Poor cognitive ageing: vulnerabilities, mechanisms and the impact of nutritional interventions. Ageing Res. Rev 42, 40–55 (March). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RA, Fisher E, Finn DP, Finnerup NB, Gilron I, Haroutounian S, Krane E, Rice ASC, Rowbotham M, Wallace M, Eccleston C, 2021. Cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicines for pain management: an overview of systematic reviews. Pain 162 (1), S67–S79. July 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy A.Pachana, Hans-Werner Wahl, 2016. Healthy Aging: Current and Future Frameworks and Developments., Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology (Book). June 20. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrin S, Watson CJW, Perez-Paramo YX, Lazarus P, 2021. Cannabinoid metabolites as inhibitors of major hepatic CYP450 enzymes, with implications for cannabis-drug interactions. Drug Metab. Dispos September 7:DMD-AR-2021–000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natalya M.Kogan, 2007. Cannabinoids in health and disease. Dialog-. Clin. Neurosci 9 (4), 413–430 (December). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete F, García-Gutiérrez MS, Gasparyan A, Austrich-Olivares A, Femenía T, Manzanares J, 2020. Cannabis use in pregnant and breastfeeding women: behavioral and neurobiological consequences. Front. Psychiatry 11, 586447. November 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemat Khansari, Yadollah Shakiba, Mahdi Mahmoudi, 2009. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov 3 (1), 73–80 (January). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves J, Sousa-Victor P, 2020. Regulation of inflammation as an anti-aging intervention. FEBS J. 287 (1), 43–52 (January). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nina Pocuca, Walter T.Jordan, Arpi Minassian, Young Jared W., Geyer Mark A., William Perry, 2020. The effects of cannabis use on cognitive function in healthy aging: a systematic scoping review. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol, acaa105. November 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Prattichizzo F, Grillari J, Balistreri CR, 2018. Cellular senescence and inflammaging in age-related diseases. Mediat. Inflamm 2018, 9076485. April 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan SE, 2016. An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharm 173 (12), 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AK, Xu M, Zhu Y, Pirtskhalava T, Weivoda MM, Hachfeld CM, Prata LG, van Dijk TH, Verkade E, Casaclang-Verzosa G, et al. , 2019. Targeting senescent cells alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. Aging Cell 18, e12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paola Lucia Minciullo, Antonino Catalano, Giuseppe Mandraffino, Marco Casciaro, Andrea Crucitti, Giuseppe Maltese, Nunziata Morabito, Antonino Lasco, Sebastiano Gangemi, Giorgio Basile, 2016. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: the role of cytokines in extreme longevity. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp 64, 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh T, Pemmasani S, Desai R, 2020. Marijuana use among young adults (18–44 Years of Age) and risk of stroke: a behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey analysis. Stroke 51 (1), 308–310 (January). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani S, McGoohan K, Velayudhan L, Bhattacharyya S, 2021. Safety and tolerability of natural and synthetic cannabinoids in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of open-label trials and observational studies. Drugs Aging 38 (10), 887–910 (October). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poljsak B, Milisav I, Aging, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants, (Book Chapter) Published in Oxidative stress and Chronic Degenerative diseases, a role for Antioxidants. May 22nd 2013. ISBN: 978–953–51–1123–8.

- Pryimak N, Zaiachuk M, Kovalchuk O, Kovalchuk I, 2020. Tissue fibrosis, aging and the potential use of cannabinoids as anti-fibrotic agents. Preprints, 2020100464. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V, Grogan D, Ahluwalia M, Salles ÉL, Ahluwalia P, Khodadadi H, Alverson K, Nguyen A, Raju SP, Gaur P, Braun M, Vale FL, Costigliola V, Dhandapani K, Baban B, Vaibhav K, 2020. Targeting the endocannabinoid system: a predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine-directed approach to the management of brain pathologies. EPMA J. 11 (2), 217–250. April 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J.Havighurst, 1961. Successful aging (March). Gerontologist 1 (1), 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CK, Sindhu KK, 2009. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 84 (21–22), 705–712. May 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin Holliday, 2004. The close relationship between biological aging and age-associated pathologies in humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 59 (6), B543–B546 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger Y, Wong A, 2018. New strategic approach to successful aging and healthy aging. Geriatric 3 (4), 86 (December). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero Cabrera AJ, 2016. Inflammatory oxidative aging: a new theory of aging. MOJ Immunol. 3 (5), 00103. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa Vona, Lucrezia Gambardella, Camilla Cittadini, Elisabetta Straface, Donatella Pietraforte, 2019. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome and associated diseases. Article ID 8267234 Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2019, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rower JE, King AD, Wilkins D, Wilkes J, Yellepeddi V, Maese L, Lemons RS, Constance JE, 2021. Dronabinol prescribing and exposure among children and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol 10 (2), 175–184 (April). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D, 2015. Safety and toxicology of cannabinoids. Neurotherapeutics 12 (4), 735–746 (October). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles ÉL, Khodadadi H, Jarrahi A, Ahluwalia M, Paffaro VA Jr., Costigliola V, Yu JC, Hess DC, Dhandapani KM, Baban B, 2020. Cannabidiol (CBD) modulation of apelin in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Cell. Mol. Med 24 (21), 12869–12872 (November). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shijin Xia, Xinyan Zhang, Songbai Zheng, Ramin Khanabdali, Bill Kalionis, Junzhen Wu, Wenbin Wan, Xiantao Tai, 2016. An update on inflamm-aging: mechanisms, prevention, and treatment. J. Immunol. Res 2016, 8426874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A.Katharina, Hollander Georg A., McMichael Andrew, 2015. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc. Biol. Sci 282 (1821), 20143085. December 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinemyiz Atalay, Iwona Jarocka-Karpowicz, Elzbieta Skrzydlewska, 2019. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol. Antioxidants 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siracusa R, Scuto M, Fusco R, Trovato A, Ontario ML, Crea R, Di Paola R, Cuzzocrea S, 2020. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activity of hidrox® in rotenone-induced parkinson’s disease in mice. Antioxidants 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soazig Le. Lay, Gilles Simard, Maria Carmen Martinez, 2014. Ramaroson andriantsitohaina, “oxidative stress and metabolic pathologies: from an adipocentric point of view. Article ID 908539 Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2014, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn E, 2019. Weighing the dangers of cannabis. Nature 572 (7771), S16–S18 (August). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Hu F, Wu J, Zhang S, 2017. Cannabidiol attenuates OGD/R-induced damage by enhancing mitochondrial bioenergetics and modulating glucose metabolism via pentose-phosphate pathway in hippocampal neurons. Redox Biol. 11, 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamas Fulop, Anis Larbi, Gilles Dupuis, Aurélie Le. Page, Eric H.Frost, Alan A.Cohen, Jacek M.Witkowski, Claudio Franceschi, 2018. Immunosenescence and inflamm-aging as two sides of the same coin: friends or foes? Front. Immunol 8, 1960. January 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarique Hussain, Bie Tan, Yulong Yin, Francois Blachier, Myrlene C.B. Tossou, Najma Rahu, 2016. Oxidative stress and inflammation: what polyphenols can do for us? Article ID 7432797 Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2016, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teresa Niccoli, Linda Partridge, 2012. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr. Biol 22 (17), R741–R752. September 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmanski Tomasz, Diener Christian, Rappaport Noa, Patwardhan Sushmita, Wiedrick Jack, Lapidus Jodi, Earls John C., Zimmer Anat, Glusman Gustavo, Robinson Max, Yurkovich James T., Kado Deborah M., Cauley Jane A., Zmuda Joseph, Lane Nancy E., Magis Andrew T., Lovejoy Jennifer C., Hood Leroy, Gibbons Sean M., Orwoll Eric S., Price Nathan, Gut Microbiome Pattern Reflects Healthy Aging and Predicts Extended Survival in Humans., bioRxiv 2020.02.26.966747; [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte C, Chouinard F, Lefebvre JS, Flamand N, 2015. Regulation of inflammation by cannabinoids, the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol and arachidonoyl-ethanolamide, and their metabolites. J. Leukoc. Biol 97 (6), 1049–1070 (June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urtamo Annele, Satu K.Jyväkorpi, Timo E.Strandberg, 2019. Definitions of successful ageing: a brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta Biomed. 90 (2), 359–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio Chiurchiù, van der Stelt Mario, Diego Centonze, Mauro Maccarrone, 2018. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation in multiple sclerosis: clues for other neuroinflammatory diseases. Prog. Neurobiol 160, 82–100 (January). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velayudhan L, McGoohan K, Bhattacharyya S, 2021. Safety and tolerability of natural and synthetic cannabinoids in adults aged over 50 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 18 (3), e1003524. March 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrano DL, Triolo F, Maggi S, Malley R, Jackson TA, Poscia A, Bernabei R, Ferrucci L, Fratiglioni L, 2021. Fostering healthy aging: the interdependency of infections, immunity and frailty. Ageing Res. Rev 69, 101351. May 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viña J, Borras C, Abdelaziz KM, Garcia-Valles R, Gomez-Cabrera MC, 2013. The free radical theory of aging revisited: the cell signaling disruption theory of aging. Antioxid. Redox Signal 19 (8), 779–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang A, Guerrini MM, Minato N, Fagarasan S, 2018. Microbiota - an amplifier of autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol 55, 15–21 (December). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG, 2010. Arterial aging: a journey into subclinical arterial disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens 19 (2), 201–207 (March). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ware MA, 2008. Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review. CMAJ 178 (13), 1669–1678. June 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang L, Wen X, Hao D, Zhang N, He G, Jiang X, 2019. NF-kappaB signaling in skin aging. Mech. Ageing Dev 184, 111160 (December). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warraich UE, Hussain F, Kayani HUR, 2020. Aging - oxidative stress, antioxidants and computational modeling. Heliyon 6 (5), e04107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weili Xu, Glenn Wong, You Yi. Hwang, Anis Larbi, 2020. The untwining of immunosenescence and aging. Semin. Immunopathol 42, 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias Pandelides, Cammi Thornton, Anika S.Faruque, Alyssa P.Whitehead, Kristine L.Willett, Nicole M.Ashpole, 2020. Developmental exposure to cannabidiol (CBD) alters longevity and health span of zebrafish (Danio rerio). GeroScience 42, 785–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurier RB, Burstein SH, 2016. Cannabinoids, inflammation, and fibrosis. FASEB J. 30 (11), 3682–3689 (November). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]