Abstract

Background

The rates of early-onset group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease (EOGBS) have declined since the implementation of universal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines but late-onset (LOGBS) rates remain unchanged. Racial differences in GBS disease rates have been previously documented, with Black infants having higher rates of EOGBS and LOGBS, but it is not known if these have persisted. Therefore, we sought to determine the differences in EOGBS and LOGBS disease by race over the past decade in Tennessee.

Methods

This study used active population-based and laboratory-based surveillance data for invasive GBS disease conducted through Active Bacterial Core surveillance in selected counties across Tennessee. We included infants younger than 90 days and who had invasive GBS disease between 2009 and 2018.

Results

A total of 356 GBS cases were included, with 60% having LOGBS. EOGBS and LOGBS had decreasing temporal trends over the study period. Overall, there were no changes in temporal trend noted in the rates of EOGBS and LOGBS among White infants. However, Black infants had significantly decreasing EOGBS and LOGBS temporal trends (relative risk [95% confidence interval], .87 [.79, .96] [P = .007] and .90 [.84–.97] [P = .003], respectively).

Conclusions

Years after the successful implementation of the universal screening guidelines, our data revealed an overall decrease in LOGBS rates, primarily driven by changes among Black infants. More studies are needed to characterize the racial disparities in GBS rates, and factors driving them. Prevention measures such as vaccination are needed to have a further impact on disease rates.

Keywords: group B Streptococcus, race, early-onset, late-onset

Decades after implementation of universal prenatal screening guidelines, late-onset group B Streptococcus disease remains more common than early-onset disease with differences by race noted. Early- and late-onset diseases are significantly decreasing in Black infants while remaining constant among White infants.

Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae; GBS) is a major cause of invasive bacterial infections in neonates and young infants and can cause either early-onset (<7 days of life) or late-onset (7–89 days of life) disease [1, 2]. Both early-onset GBS (EOGBS) and late-onset GBS (LOGBS) disease are a global challenge with an incidence ranging from 0.21 to 2.00 per 1000 live births and a case fatality rate (CFR) ranging from 4.7% to 18.9% in various countries [3]. Moreover, in 2017, the global rates of EOGBS rates were higher than those for LOGBS (0.41 vs 0.26 per 1000 live births), with a CFR of 10% and 7% for EOGBS and LOGBS disease, respectively [3].

A woman’s gastrointestinal tract serves as the primary reservoir for GBS and is likely the source of vaginal colonization [4]. Maternal recto-vaginal colonization with GBS and subsequent vertical transmission to the neonate is the primary risk factor for EOGBS disease [4]. Risk factors for colonization include Black race, obesity, diabetes, and older age [5–7]. However, only 1–2% of neonates born to colonized mothers develop EOGBS disease [4]. Other known risk factors for EOGBS disease include prematurity, very low birth weight, prolonged rupture of membranes, intra-amniotic infection, GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy, intrapartum fever, young maternal age, maternal obesity and diabetes, and maternal Black race [4, 8–11]. Prior studies have demonstrated that intrapartum antibiotics started at least 4 hours prior to delivery in colonized pregnant women have been associated with substantial reductions in EOGBS disease [4]. In the United States, guidelines issued in 1996 recommended either screening of all pregnant women for GBS colonization (screening approach) or assessing clinical risk factors (risk-based approach) to identify candidates for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis [12]. A study in the 1990s found that the screening approach showed that 18% of all deliveries were to culture-positive women without risk factors [12]. The rates of EOGBS disease have declined tremendously since the implementation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revised guidelines for the prevention of perinatal GBS disease in 2002, including routine universal culture-based screening of women for GBS colonization between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation followed by antibiotic prophylaxis during delivery if known GBS positive [13, 14]. Those guidelines were revised in 2019 to include later screening between 36 and 38 weeks of gestation [8].

Alternatively, LOGBS rates were not impacted by universal screening, and recent reports demonstrate that LOGBS rates among US infants are now higher than EOGBS rates [14, 15]. Also, less is known about GBS acquisition in LOGBS; vertical transmission from the mother, healthcare-associated transmission, contaminated breast milk, and/or community transmissions are postulated to play a role [16, 17]. Prematurity, young maternal age, and Black race have been identified as risk factors for LOGBS disease [9, 18], but further identification of risk factors is needed for the implementation of prevention strategies [14, 19].

Not only has Black race been identified as a risk factor for GBS colonization and disease but racial differences in disease rates and screening frequencies have also been reported [20, 21]. Therefore, it was not surprising that Black infants had higher rates of EOGBS disease compared with White infants in 1990 [22]. After the implementation of the universal screening guidelines, the CDC reported an improvement in the racial disparity of EOGBS disease rates between Black and White infants; however, Black infants continued to have higher EOGBS and LOGBS disease rates from 2006 to 2015 [14, 15, 22, 23]. Currently, it is not known whether disease rates remain different between racial groups. Given these known risk factors and racial differences for GBS disease, we sought to compare EOGBS and LOGBS disease by race and prematurity status over the past decade.

METHODS

Surveillance

The Active Bacterial Core surveillance system (ABCs) is a component of the Emerging Infections Program Network that involves collaboration between the CDC, state health departments, and universities to perform active population-based and laboratory-based surveillance [24]. This includes surveillance for invasive GBS disease in select counties of 10 US states, including Tennessee [25]. Trained staff collect clinical data from medical records using standardized forms. The Human Subjects Review Boards at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) determined the study to be exempt because it involves very minimal to no risk to participants. Additionally, the CDC reviewed this activity for human subjects’ protection and determined it to be nonresearch. The methods of ABCs, including those used for the identification of clinical syndromes, and determination of race are detailed elsewhere [26]. This study includes data collected from Tennessee from 2009 through 2018.

Study Population

We included infants up to 89 days of age with invasive GBS disease who resided in one of the surveillance counties. In 2009, 11 counties were included in Tennessee’s surveillance, which then expanded to include 20 counties throughout the following years, 2010–2018. The combined population under surveillance represented 55% and 63% of the state’s total births in 2009 and 2018, respectively. In 2018, Tennessee’s births under surveillance were 68% White and 28% Black; in comparison, the state’s births were 76% White and 21% Black [27].

Definitions

A case of invasive GBS disease was defined as isolation of S. agalactiae from a sterile site (eg, blood, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], joint, muscle, bone, pleura, pericardium, perineum) using conventional microbiological methods. EOGBS was defined as invasive GBS disease in infants aged 0–6 days after birth and 7–89 days for LOGBS. Preterm was defined as infants who were born before 37 weeks of gestational age.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed using StataIC 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). We summarized variables as frequencies (%) for categorical variables or means (SD) for continuous variables. Between-group comparisons were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and a 2-sample t test allowing unequal variances for continuous variables. We used a significance level (ɑ) of .05 for all analyses. Missing race data were imputed using multiple imputation and analyses were performed accounting for imputation by using multiple imputation by chained equations and Rubin’s rule. Approximately 3.7% of observations were missing the total number of births for a given county and race.

The GBS rates were reported as cases per 1000 live births and were calculated using ABCs case counts as the numerator and the number of live births as the denominator. We used TDH vital statistics reports to obtain ABCs county- and race-specific live birth data [27]. Rate comparisons were performed using R 3.6.1, lme4 1.1–21 (R Core Team) [28–32]. We used a Poisson linear mixed model with log-link to model temporal trends in the rates of EOGBS and LOGBS births and compare them over the duration of the survey data (2009–2018). An offset was included for total births of a given race, to account for differences between county sizes and demographics, as well as a random effect for county. Linear main effects included race, disease type, and year; we further allowed interaction between disease type and year.

To study differences with respect to race, we fit separate models for EOGBS and LOGBS disease. These models included the offset and random effect described above and main effects of year, race, and their interaction. Race-specific live birth data were missing for Union county for White race between 2015 and 2017, for Black race between 2010 and 2018, and for Grainger county for Black race between 2010 and 2012. The TDH explains missing data by having a White or Black population of less than 50 or not being reported according to the TDH guidelines for release of aggregate data to the public [27].

RESULTS

Group B Streptococcus Cohort

From 2009 through 2018, 356 infants had GBS disease and 55% were male; 158 (44%) were White, 170 (48%) were Black, 2 (1%) were of another race, and 26 (6%) were unknown. The median age at the time of GBS isolation was 18 (0–38) days, maternal age at delivery was 25 (20–30) years, and gestational age was 38 (32–39) weeks. Sixty-five percent were publicly insured, while 26% had private insurance. Thirty-seven percent were premature, 71% of the infants were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and 8% died. Fifty-three percent (149/320) of mothers received intrapartum antibiotics. Of the 260 mothers who had screening data available, 68% were screened prior to admission for delivery, and of the 116 mothers who had screening results available, 29% were colonized with GBS.

EOGBS Versus LOGBS Disease

Table 1 includes a comparison of infants with EOGBS and LOGBS. Over the combined study period, the majority of cases were LOGBS (214, 60%) and were more likely to be premature and have a lower gestational age but less likely to be admitted to the ICU compared with those with EOGBS (Table 1). Mothers of infants with EOGBS were more likely to be screened prior to admission but less likely to screen positive and to receive intrapartum antibiotics compared with mothers of infants with LOGBS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Early- and Late-onset Group B Streptococcus Disease in Tennessee Between 2009 and 2018

| EOGBS (n = 142) | LOGBS (n = 214) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 78 (55) | 118 (55) | .969 |

| Age,a days | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 37.4 ± 20.0 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 74/129 (57) | 84/199 (42) | .007 |

| Black | 55/129 (43) | 115/199 (58) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 42/134 (31) | 46/206 (22) | .202 |

| Public | 81/134 (60) | 141/206 (68) | |

| Premature | 39/139 (28) | 86/201 (43) | .006 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36.4 ± 4.9 | 34.9 ± 5.3 | .009 |

| ICU admission | 107/118 (91) | 99/172 (58) | <.001 |

| Died | 12 (8) | 17/209 (8) | .912 |

| Maternal age at delivery, years | 25.1 ± 5.6 | 25.4 ± 6.3 | .739 |

| Maternal GBS colonization screened before admission for delivery | 84/108 (78) | 92/152 (61) | .003 |

| Maternal GBS colonization positive before admission for delivery | 11/58 (19) | 23/58 (40) | .014 |

| Intrapartum antibiotics given to mother | 43/130 (33) | 136/214 (56) | <.001 |

Data are presented as n (%), or means ± SDs. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus; GBS, group B Streptococcus; ICU, intensive care unit; LOGBS, late-onset group B Streptococcus.

a P value was not calculated because subjects are classified as EOGBS and LOGBS depending on age at diagnosis.

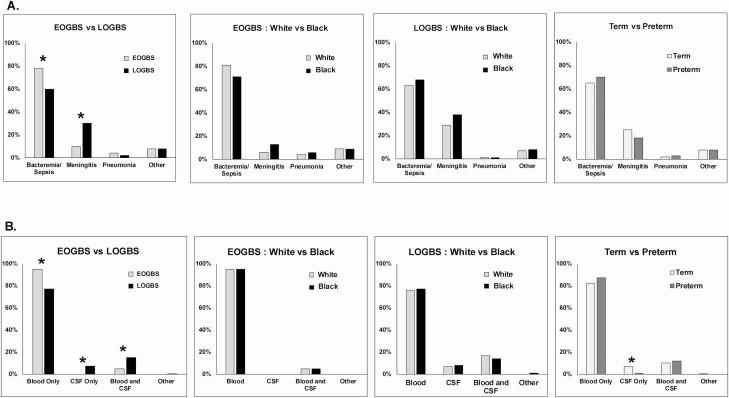

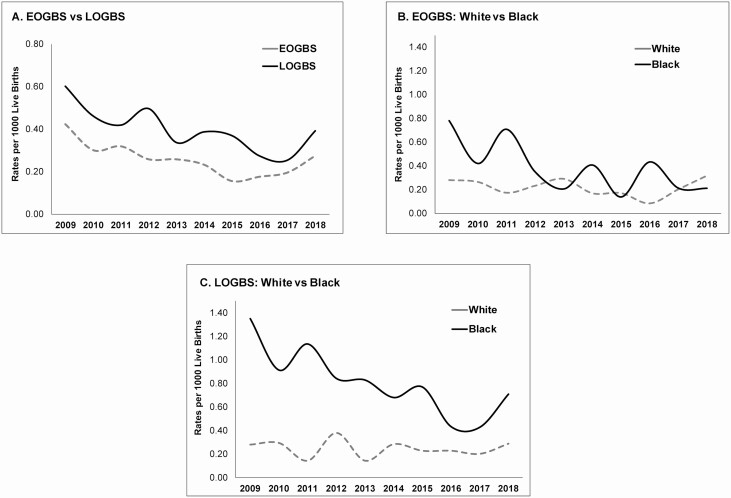

Cases with EOGBS were more likely to present with bacteremia/sepsis and less likely to have meningitis (Figure 1A). Moreover, cases with EOGBS had a higher proportion of GBS isolated from the blood and were less likely to have GBS isolated from CSF or blood and CSF (Figure 1B). Figure 2A shows EOGBS versus LOGBS rates over the study period.

Figure 1.

A, Cumulative frequency of clinical syndromes between 2009 and 2018 presented by EOGBS and LOGBS and then stratified by race and prematurity. B, Cumulative frequency of sterile sites between 2009 and 2018 presented by EOGBS and LOGBS and then stratified by race and prematurity. *Pearson’s chi-square test used for comparison, P < .05. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus; LOGBS, late-onset group B Streptococcus.

Figure 2.

A, Annual rates of EOGBS and LOGBS disease from 2009 to 2018 in Tennessee. B, Annual rates of EOGBS disease by race from 2009 to 2018 in Tennessee. C, Annual rates of LOGBS disease by race from 2009 to 2018 in Tennessee. Abbreviations: EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus; LOGBS, late-onset group B Streptococcus.

Racial Differences in EOGBS and LOGBS Disease

Table 2 compares EOGBS and LOGBS by race. Black infants with EOGBS and LOGBS disease were more likely to have public insurance compared with White infants (Table 2). Among those with LOGBS, White infants were more likely to be screened for GBS prior to admission and have mothers with a higher maternal age at delivery compared with Black infants, whereas there were no racial differences in cases of EOGBS (Table 2). Figure 2B and 2C demonstrates EOGBS and LOGBS rates by race over the study time period.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Early- and Late-onset Group B Streptococcus Disease by Race in Tennessee Between 2009 and 2018

| EOGBS | LOGBS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 74) | Black (n = 55) | P | White (n = 84) | Black (n = 115) | P | |

| Sex, male | 40 (54) | 30 (55) | .956 | 47 (56) | 63 (55) | .870 |

| Age, days | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | .745 | 35.9 ± 20.0 | 38.4 ± 20.5 | .397 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Private | 31/69 (45) | 6/53 (11) | <.001 | 39/83 (47) | 5/110 (5) | <.001 |

| Public | 32/69 (46) | 44/53 (83) | 39/83 (47) | 94/110 (85) | ||

| Premature | 16/72 (22) | 19/55 (35) | .124 | 30/77 (39) | 54/111 (49) | .189 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36.8 ± 4.7 | 35.7 ± 5.2 | .197 | 35.4 ± 5.2 | 34.4 ± 5.5 | .201 |

| ICU admission | 55/63 (87) | 41/44 (93) | .324 | 43/70 (61) | 51/92 (55) | .444 |

| Died | 5 (7) | 6 (11) | .404 | 6 (7) | 11 (10) | .555 |

| Maternal age at delivery, years | 25.7 ± 5.4 | 23.9 ± 5.4 | .075 | 27.5 ± 6.1 | 23.7 ± 5.9 | <.001 |

| Maternal GBS screened before admission for delivery | 49/62 (79) | 28/38 (74) | .537 | 50/73 (68) | 37/72 (51) | .036 |

| Maternal GBS colonization positive before admission for delivery | 7/36 (20) | 4/16 (25) | .651 | 11/33 (33) | 10/22 (45) | .365 |

| Intrapartum antibiotics given to mother | 19/69 (28) | 21/50 (42) | .099 | 47/78 (60) | 54/100 (54) | .403 |

Data are presented as n (%), n/N (%), or means ± SDs. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus; GBS, group B Streptococcus; ICU, intensive care unit; LOGBS, late-onset group B Streptococcus.

Preterm Versus Term Group B Streptococcus Cases

When comparing term versus preterm GBS cases, preterm infants were more likely to be Black, require ICU admission, and die compared with term infants (P < .05). Mothers of term GBS cases were more likely to be screened for GBS colonization prior to admission to delivery but less likely to be screened positive and to receive intrapartum antibiotics than mothers of preterm infants (P < .05). There were no differences in clinical syndromes developed between term and preterm infants (Figure 1A), but term infants were more likely to have GBS isolated from CSF compared with preterm infants (Figure 1B).

Temporal Trends in Overall EOGBS and LOGBS Rates

Overall, there was a significant decrease in GBS disease over the years (relative risk [RR], .94; 95% confidence interval [CI], .90–.97; P < .001), an increased risk of developing LOGBS compared with EOGBS (RR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.24–1.93; P < .001), and a decreased risk of GBS disease in White compared with Black infants (RR, .43; 95% CI, .33–.54; P < .001). There was no evidence of a difference in the trend by year between EOGBS and LOGBS rates (year by GBS type interaction; RR, 1.00; 95% CI, .93–1.09; P = .93).

Racial Differences in Temporal Trends Between EOGBS and LOGBS Rates

We fit a generalized linear mixed model separately for EOGBS and LOGBS to study racial differences in temporal trends of GBS disease. Our results showed a significantly decreasing trend in EOGBS rates (RR, .93; 95% CI, .88–.99; P = .029). There was not sufficient power to detect a significant difference in the rates of change between Black and White races (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, .97–1.27; P = .081). Overall, there were no changes of temporal trend noted in the rates of EOGBS among White infants (RR, .98; 95% CI, .90–1.06; P = .595). However, Black infants had a significantly decreasing EOGBS temporal trend (RR, .87; 95% CI, .79–.96; P = .007).

Rates of LOGBS also decreased over time. There was a main effect of race in LOGBS rates as they were significantly higher in Black infants across the duration of the study (White RR, .22; 95% CI, .13–.36; P < .001). There was not sufficient power to detect a difference in the rates of change between White and Black infants (year by race interaction RR, 1.09; 95% CI, .98–1.20; P = .104). There was no temporal trend change noted in LOGBS rates for White race (RR, .99; 95% CI, .92–1.07; P = .768). However, Black infants showed a significantly decreasing temporal trend (RR, .90; 95% CI, .84–.97; P = .003).

Discussion

In our study evaluating the racial differences of GBS disease in Tennessee over a decade, we noted that EOGBS rates have decreased significantly among Black infants and remained relatively stable among White infants. In contrast to our findings, a study conducted between 2003 and 2005 reported an increase in EOGBS rates among Black infants and a decrease among White infants [21, 23]. In another study evaluating EOGBS rates by race from 2006 to 2015 in the United States, there was a statistically significant decline in EOGBS rates among both White infants (from 0.29 to 0.15 per 1000 live births; P < .001) and Black infants (from 0.76 to 0.55 per 1000 live births; P = .04), but EOGBS rates were 2.4 times higher in Black infants compared with White infants [15]. Factors contributing to racial disparities include higher maternal colonization, especially late in the third trimester, and lower screening frequencies in Black compared with White mothers [20, 21]. The 2019 guidelines addressed the late pregnancy discrepancy by recommending prenatal universal screening between 36 0/7 and 37 6/7 weeks of gestation [33, 34]. Therefore, further reductions in racial disparities, as noted in our study, are expected and continued surveillance for GBS is warranted to monitor these trends to evaluate practices and continuously update recommendations.

We also noted that LOGBS rates declined significantly among Black infants yet stayed relatively stable in White infants. However, despite decreasing rates, LOGBS rates in Black infants remained 2.4 times higher. This is similar to previous studies that reported LOGBS to be approximately 3 times higher in Black infants compared with non-Black infants between 1990–2005 and 2006–2015 [15]. Risk factors affecting LOGBS need further evaluation and additional research is needed to understand why differences occur and to adopt targeted interventions to help reduce the disease burden and these racial disparities.

Our data indicate that the prevalence of LOGBS is higher than EOGBS and cumulatively represented the majority of cases. The declining trend of EOGBS with unchanged LOGBS rates was widely described after the introduction of universal screening [4], leading to higher rates of LOGBS compared with EOGBS [15]. In our study, EOGBS and LOGBS both declined, with a steeper decrease in the LOGBS rates. The impact of universal screening and the successful implementation and maintenance of the universal screening guidelines most likely explain the stabilization of EOGBS rates [15]. However, since no strategies exist to prevent LOGBS, health officials were concerned initially that widespread antimicrobial use might delay GBS disease onset and result in an increase in LOGBS [35]. In the United States, LOGBS rates remained unchanged after the increase in screening and intrapartum antibiotics administration and our study is the first to show a decreasing LOGBS trend [4, 14, 36]. Prematurity is the main identified risk factor for LOGBS. From 2005 to 2014, a 15% decline in prematurity was noted after major efforts in Tennessee were implemented to reduce prematurity, likely contributing to the decline in LOGBS rates [37]. Moreover, GBS in LOGBS is believed to be acquired by horizontal transmission from either the mother or individuals in the community, so changes in community exposures could play a role in these trend changes, but additional studies are needed to explore this theory further [16]. Candidate GBS vaccines are also under development, which will be important for LOGBS prevention [1].

All causes of sepsis, including GBS, are higher in preterm infants compared with term infants [38]. Prematurity is another known risk factor for both EOGBS and LOGBS and was previously reported to be higher in LOGBS disease [13, 14, 18, 33]. We also noted that infants with LOGBS had a higher frequency of prematurity and lower gestational age when compared with EOGBS, but both proportions are higher than the general population in the United States (9.9% of live births) [31]. Furthermore, consistent with our findings, the CDC also reported in 2004 a higher percentage of prematurity among LOGBS compared with EOGBS cases [35]. Tennessee has higher rates of prematurity compared with the rest of the nation, with 11.3% of live births being preterm between 2015 and 2017, and 14.8% of Black live births compared with 10.3% of White live births were preterm in the state [32]. Therefore, prematurity may be playing a role in the higher GBS rates among Black infants [13]. Additionally, preterm infants have a higher frequency of death compared with term infants, which is consistent with findings of previous studies reporting EOGBS CFRs to be 20–30% versus 2–3% between preterm and term infants, respectively [4]. Strategies and public health policies aimed at reducing prematurity may, in turn, help reduce the incidence of both EOGBS and LOGBS, and impact further reductions in LOGBS rates in Black infants.

The strengths of our study include the large sample size of GBS cases and the long time period in which the data were extracted. Our surveillance includes 20 counties in Tennessee, covering over half of the state’s population, with race distributions similar to the state’s actual distribution, which makes our findings representative of the state’s numbers; however; data may not be generalizable to other states. Moreover, these data were collected through retrospective chart reviews of subjects after isolation of GBS from a sterile site, and some data were incomplete or missing. Also, we did not have denominators to calculate incidence rates by prematurity, which is a major risk factor for EOGBS and LOGBS. Moreover, Tennessee’s surveillance site does not include serotype data; therefore, we were not able to report which serotypes are driving EOGBS versus LOGBS.

In summary, LOGBS disease continues to predominate over EOGBS with decreasing trends in both diseases over time in Tennessee. Specifically, we noted that both EOGBS and LOGBS rates are decreasing among Black infants, while rates among White infants remained relatively stable, indicating the decline in rates among Black infants is driving the overall decrease noted. In addition, our study is the first to report a decrease in LOGBS rates. More studies are needed to characterize the recent changes noted in LOGBS rates, the racial disparities in GBS rates, and factors driving them. Our study also supports research and implementation strategies for prematurity prevention and the need for GBS maternal vaccination to further decrease the burden of GBS disease.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors acknowledge all of the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) team members who contributed to this project.

Financial support. This work was supported primarily by an Emerging Infections Program’s cooperative agreement (grant number 1U50CK000491) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; REDCap (grant number ULI TR000445) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health (NIH); NIH grant R01 HD090061 (to J. A. G.) and a Career Development Award (grant number IK2BX001701; to J. A. G) from the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veterans Affairs; by additional funding from NIH grants U01TR002398 and R01AI134036 and the March of Dimes (to D. M. A.); and from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research program supported by the National Center for Research Resources (grant number UL1 RR024975–01), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant 2 UL1 TR000445–06).

Potential conflicts of interest. W. S. reports personal fees from Pfizer and VBI Vaccines outside the submitted work. N. B. H. reports grants from Sanofi and Quidel and personal fees from Genentech, outside the submitted work. D. M. A. reports grants to Study Group B Streptococcus from the National Institutes of Health, March of Dimes, and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Melin P. Neonatal group B streptococcal disease: from pathogenesis to preventive strategies. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:1294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schrag SJ, FarleyMM, PetitS, et al. Epidemiology of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis, 2005 to 2014. Pediatrics 2016; 138:e20162013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madrid L, Seale AC, Kohli-Lynch M, et al. ; Infant GBS Disease Investigator Group . Infant group B streptococcal disease incidence and serotypes worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:160–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ; Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease—revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010; 59:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Regan JA, Klebanoff MA, Nugent RP. The epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization in pregnancy. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77:604–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kleweis SM, Cahill AG, Odibo AO, Tuuli MG. Maternal obesity and rectovaginal group B Streptococcus colonization at term. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2015; 2015:586767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Venkatesh KK, Vladutiu CJ, Strauss RA, et al. Association between maternal obesity and group B Streptococcus colonization in a national U.S. cohort. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020; 10.1089/jwh.2019.8139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, number 782. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 134:206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schuchat A, Oxtoby M, Cochi S, et al. Population-based risk factors for neonatal group B streptococcal disease: results of a cohort study in metropolitan Atlanta. J Infect Dis 1990; 162:672–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Al-Kadri HM, Bamuhair SS, Johani SM, Al-Buriki NA, Tamim HM. Maternal and neonatal risk factors for early-onset group B streptococcal disease: a case control study. Int J Womens Health 2013; 5:729–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elvedi-Gasparović V, Peter B. Maternal group B streptococcus infection, neonatal outcome and the role of preventive strategies. Coll Antropol 2008; 32:147–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team . A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schrag SJ, Verani JR. Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: experience in the United States and implications for a potential group B streptococcal vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31(Suppl 4):D20–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jordan HT, Farley MM, Craig A, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs)/Emerging Infections Program Network, CDC . Revisiting the need for vaccine prevention of late-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease: a multistate, population-based analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27:1057–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nanduri SA, Petit S, Smelser C, et al. Epidemiology of invasive early-onset and late-onset group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 2006 to 2015: multistate laboratory and population-based surveillance. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173:224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berardi A, Rossi C, Lugli L, et al. ; GBS Prevention Working Group, Emilia-Romagna . Group B streptococcus late-onset disease: 2003-2010. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shabayek S, Spellerberg B. Group B streptococcal colonization, molecular characteristics, and epidemiology. Front Microbiol 2018; 9:437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin FY, Weisman LE, Troendle J, Adams K. Prematurity is the major risk factor for late-onset group B streptococcus disease. J Infect Dis 2003; 188:267–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mukhopadhyay S, Puopolo KM. Preventing neonatal group B Streptococcus disease: the limits of success. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173:219–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bryant AS, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. Equality in obstetrical care: racial/ethnic variation in group B Streptococcus screening. Matern Child Health J 2011; 15:1160–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Perinatal group B streptococcal disease after universal screening recommendations—United States, 2003–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007; 56:701–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diminishing racial disparities in early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease—United States, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:502–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Phares CR, Lynfield R, Farley MM, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network . Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999-2005. JAMA 2008; 299:2056–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schuchat A, Hilger T, Zell E, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team of the Emerging Infections Program Network . Active bacterial core surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:92–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance report, Emerging Infections Program Network, group B Streptococcus, 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gbs17.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core surveillance: methodology—surveillance population. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/methodology/surv-pop.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tennessee Department of Health. General health data: birth statistics. Available at: https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/statistics/health-data/birth-statistics.html. Accessed 22 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2019. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- 29. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S.. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015; 67:48. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lenth R. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.5. 2020. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans. Accessed 22 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB.. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw 2017; 82:26. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarkar D. Lattice: multivariate data visualization with R. New York: Springer, 2008:268. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, number 797. Obstet Gynecol 2020; 135:489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spiel MH, Hacker MR, Haviland MJ, et al. Racial disparities in intrapartum group B Streptococcus colonization: a higher incidence of conversion in African American women. J Perinatol 2019; 39:433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early-onset and late-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease—United States, 1996–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54:1205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, et al. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lummus A, Walton A. Why are Tennessee moms and babies dying at such a high rate? 2018. Available at: https://www.tnjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Infant-and-Maternal-Mortality-Policy-Brief.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- 38. Puopolo KM, Benitz WE, Zaoutis TE, et al. Management of neonates born at ≥35 0/7 weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20182894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]