Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) a life‐limiting inherited disease affecting a number of organs, but classically associated with chronic lung infection and progressive loss of lung function. Chronic infection by Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and therefore represents a significant challenge to clinicians treating people with CF. This review examines the current evidence for long‐term antibiotic therapy in people with CF and chronic BCC infection.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of long‐term oral and inhaled antibiotic therapy targeted against chronic BCC lung infections in people with CF. The primary objective is to assess the efficacy of treatments in terms of improvements in lung function and reductions in exacerbation rate. Secondary objectives include quantifying adverse events, mortality and changes in quality of life associated with treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register, compiled from electronic database searches and handsearching of journals and conference abstract books. We also searched online trial registries and the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews.

Date of last search: 12 April 2021.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of long‐term antibiotic therapy in people with CF and chronic BCC infection.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data, assessed risk of bias and assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We included one RCT (100 participants) which lasted 52 weeks comparing continuous inhaled aztreonam lysine (AZLI) and placebo in a double‐blind RCT for 24 weeks, followed by a 24‐week open‐label extension and a four‐week follow‐up period. The average participant age was 26.3 years, 61% were male and average lung function was 56.5% predicted.

Treatment with AZLI for 24 weeks was not associated with improvement in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), mean difference 0.91% (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.15 to 4.97) (moderate‐quality evidence). The median time to the next exacerbation was 75 days in the AZLI group compared to 51 days in the placebo group, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.27) (moderate‐quality evidence). Similarly, the number of participants hospitalised for respiratory exacerbations showed no difference between groups, risk ratio (RR) 0.88 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.45) (moderate‐quality evidence). Overall adverse events were similar between groups, RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.19) (moderate‐quality evidence). There were no significant differences between treatment groups in relation to mortality (moderate‐quality evidence), quality of life or sputum density.

In relation to methodological quality, the overall risk of bias in the study was assessed to be unclear to low risk.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence from the literature to determine an effective strategy for antibiotic therapy for treating chronic BCC infection.

Plain language summary

Antibiotic treatments for long‐term Burkholderia cepacia infections in people with cystic fibrosis

Review question

We reviewed the evidence for long‐term antibiotic treatments for people with cystic fibrosis who are infected with Burkholderia cepacia complex (bacteria composed of at least 20 different species).

Background

People with cystic fibrosis often suffer from repeated chest infections and eventually their lungs become permanently infected by bacteria, such as a family of bacteria called Burkholderia cepacia complex which can cause problems because many antibiotics do not work against them and they can cause a quicker deterioration in lung disease. We wanted to discover whether using long‐term antibiotic treatment was beneficial for people with cystic fibrosis and Burkholderia cepacia complex infection.

Search date

The evidence is current to: 12 April 2021.

Study characteristics

This review included one study of 100 people aged between 6 and 57 years old. The study compared an inhaled antibiotic called aztreonam to placebo (a substance which contains no medication) and people were selected for one treatment or the other randomly (by chance). The study lasted 52 weeks.

Key results

The only study included in this review found inhaled aztreonam had no beneficial effect on lung function or rates of chest infections in people with cystic fibrosis and Burkholderia cepacia complex infection. There was no difference between groups in relation to the average time to the next exacerbation or the number of people hospitalised for an exacerbation. Overall adverse events were similar between groups and with regards to other outcomes assessed, there was no difference between treatment groups for mortality, quality of life or sputum density. More research is needed to establish if other inhaled antibiotics may be useful.

Quality of the evidence

Overall quality of evidence was considered to be moderate across all outcomes, which means further research is likely to have an important impact on results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings ‐ AZLI compared with placebo for chronic Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in people with CF.

| AZLI compared with placebo for chronic Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in people with CF | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with CF Settings: CF treatment centres across North America Intervention: AZLI for inhalation 75 mg three times a day via nebuliser for 24 weeks Comparison: placebo, three times a day via nebuliser for 24 weeks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | AZLI | |||||

| Relative change in FEV1% predicted | The mean change in FEV1 (% predicted) in the control group was ‐0.75% | The mean change in FEV1 (% predicted) in the intervention group was0.91% higher ( 3.15% lower to 4.97% higher) | NA | 99 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Days to next exacerbation |

See comment |

NA | 100 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Median days to next exacerbation in the control group was 75 days. Median days to next exacerbation in the intervention group was 24 days lower. | |

| Participants hospitalised for respiratory exacerbation | 400 per 1000 | 352 per 1000 (212 to 580) |

RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.45) | 100 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Any AEs | 904 per 1000 |

976 per 1000 (886 to 1076) |

RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.19) |

100 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Wheeze was more frequent in the AZLI group compared to placebo but groups were otherwise well matched. |

| Mortality | There were 0 deaths in the placebo group | There were 2 deaths in the intervention arm | RR 5.41 (95% CI 0.27 to 109.87) | 100 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝

Moderatea |

|

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AE: adverse event; AZLI: aztreonam lysine for inhalation; CF: cystic fibrosis; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

a Downgraded once due to imprecision of results (small sample size and subsequent wide CIs)

Background

Description of the condition

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a life‐threatening inherited disease affecting over 10,000 people in the UK, 35,000 in Europe and 30,000 in the USA (CFF 2016; CF Trust 2017; Farrell 2008). There have been significant improvements in CF survival since the 1930s when 70% of those with CF died in infancy, to a current median predicted survival of 43.5 years (CF Trust 2017). Early CF deaths are now rare: over 95% of children with CF enter adulthood and recent predictions are that by 2025, the number of CF adults in Europe will have nearly doubled (Burgel 2015).

In CF, the genetic autosomal‐recessive defect in the CFTR protein causes abnormal salt and water movements across mucus‐producing cell surfaces. This results in thick mucus leading to a combination of infection and inflammation with subsequent local organ damage, which is most apparent in the lungs and pancreas, but affects many other organs. In the lungs the hallmarks of disease are chronic airway inflammation and chronic infection with difficult to treat pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC). Chronic airway infection is associated with a progressive loss of lung function, which is the primary cause of death in people with CF (Corey 1997).

BCC is comprised of a group of over 20 closely related species with a cumulative annual prevalence in people with CF of 3% to 5%; Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia multivorans account for 85% to 97% of BCC infections (CFF 2016; CF Trust 2017; Drevinek 2010; Mahenthiralingam 2002; Vandamme 2011). These two pathogens are associated with poor outcomes including accelerated pulmonary decline, a necrotizing pneumonia known as 'cepacia syndrome' and a higher mortality rate (Aris 2001; Mahenthiralingam 2002; Zlosnik 2015). B cenocepacia is the more pathogenic of the two, with an increased likelihood of chronic infection and reduced survival compared to B multivorans (Jones 2004; Mahenthiralingam 2001). Acquisition is often from environmental sources, but clonal transmission of epidemic strains has been extensively reported, particularly for B cenocepacia, and hence infection control and segregation measures are required to prevent cross‐infection (Ledson 1998; LiPuma 2010; Zlosnik 2015).

Resistance to aminoglycosides, to most beta‐lactams as well as to polymyxins is common within BCC and some species have the ability to develop resistance to any agent resulting in pan‐resistant strains (CF Trust 2017; Drevinek 2010; Mahenthiralingam 2002). Therefore, the clinical management of chronic BCC infection in CF poses a challenge to clinicians.

Description of the intervention

Long‐term antibiotics are one of the mainstays of treatment in people with CF with chronic infection, these are usually inhaled or given orally to reduce the bacterial burden in sputum. Inhaled antibiotics allow rapid deposition of high concentrations of antibiotics direct to the site of action and hence represent an attractive strategy. In those with P aeruginosa infection, colistimethate, tobramycin and aztreonam have all demonstrated clinical benefit (Gibson 2003; McCoy 2008; Retsch‐Bogart 2008; Ryan 2011). The low systemic absorption associated with inhaled antibiotics can help avoid some of the side‐effects seen with intravenous antibiotics used in acute infection (Weber 1995). Oral antibiotics are quick and convenient to take, but may not be able to deliver as high a concentration to the lung as inhaled formulations. Nevertheless, oral macrolide therapy has been shown to be effective in CF with a recent Cochrane Review demonstrating a reduction in pulmonary exacerbations and improved respiratory function after six months treatment of azithromycin (Southern 2012).

How the intervention might work

Long‐term antibiotic therapy targeted towards P aeruginosa infections has been associated with improved clinical outcomes in people with CF and both inhaled and oral antibiotic therapies are recommended in that cohort (NICE 2017). There is no clear guidance on whether treatments targeted towards BCC are effective, but inhaled antibiotics may theoretically overcome traditional resistance breakpoints due the 100‐fold increase in concentrations achieved in the lung. Hence antimicrobial agents, with little or no activity against BCC at systemically achievable concentrations, may still exert bactericidal effects when inhaled into the lungs (Ramsey 1999).

Furthermore, macrolides have no in vitro bactericidal effect against P aeruginosa, yet appear to produce marked clinical improvements. This is most likely secondary to an anti‐inflammatory effect with attenuated cytokine production and reductions in neutrophil elastase reported in a number of studies (Bell 2005; Wales 1999).

Hence, despite BCC often demonstrating in vitro resistance to many of the antimicrobial agents available for chronic use in CF, there is hope that the principles of treatment and agents used in chronic P aeruginosa infection are relevant in BCC infection.

Why it is important to do this review

Chronic infection with BCC is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in people with CF. The inherent antibiotic resistance in these species makes the treatment of chronic infection challenging for clinicians. This review aims to assess the current evidence with regards to antibiotic treatment options for people with CF who are chronically infected with BCC to identify evidence‐based strategies.

Strategies will primarily be assessed in terms of their ability to preserve or improve pulmonary function and to reduce acute pulmonary exacerbations.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of long‐term oral and inhaled antibiotic therapy targeted against chronic BCC lung infections in people with CF. The primary objective is to assess the efficacy of treatments in terms of improvements in lung function and reductions in exacerbation rate. Secondary objectives include quantifying adverse events, mortality and changes in quality of life (QoL) associated with treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including those with a cross‐over design, were considered for inclusion in this review.

Types of participants

Adults and children with CF (confirmed by either a positive sweat test or the identification of two pathogenic CFTR mutations) and chronic BCC infection (defined as a positive respiratory culture growth of BCC within the last six months and BCC growth in more than 50% of all respiratory cultures in the last 12 months) (Lee 2003).

Types of interventions

Long‐term (defined as a period of eight weeks or more) antibiotics (all agents, doses and regimens) via either the inhaled or oral route. Studies were included if there was comparison to either no treatment, placebo, another antibiotic agent, another mode of delivery, or another dose or regimen of the same antibiotic.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

-

Lung function

-

forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)

absolute change in volumes, % predicted or both

relative change in volumes, % predicted or both

-

-

Pulmonary exacerbations

time to next exacerbation

hospitalisations

exacerbation rate

IV antibiotic use

-

Adverse events

mild: transient event, no treatment change, e.g. rash, nausea, diarrhoea

moderate: treatment discontinued, e.g. nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, hepatitis, visual impairment

severe: causing hospitalisation or death

Secondary outcomes

Mortality

-

QoL

validated QoL score, e.g. CFQ‐R Respiratory Symptom Score (RSS)

-

BCC culture

sputum density of BCC

-

Changes in inflammatory markers

sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples

serum or blood

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all relevant published and unpublished studies without restrictions on language, year or publication status.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Information Specialist conducted a systematic search of the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register for relevant trials using the following terms: Burkholderia cepacia:kw OR mixed infections:kw.

The Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (updated each new issue of the Cochrane Library), weekly searches of MEDLINE, a search of Embase to 1995 and the prospective handsearching of two journals ‐ Pediatric Pulmonology and the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. Unpublished work is identified by searching through the abstract books of three major cystic fibrosis conferences: the International Cystic Fibrosis Conference; the European Cystic Fibrosis Conference and the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. For full details of all searching activities for the register, please see the relevant sections of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group website.

Date of the most recent search of the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register: 12 April 2021.

We searched the following trials registries:

the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch) (searched 22 October 2021);

Clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (searched 22 October 2021).

See an appendix for details of the searches (Appendix 1).

Searching other resources

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (FF, DN) independently selected studies to be included in the review. Where there was disagreement on the suitability of a study for inclusion, all three review authors reached a consensus decision after discussion.

Data extraction and management

Each author independently extracted data using standardised data collection forms. We planned to compare outcome measures at eight weeks to three months, over three months to six months and over six months to one year. However, we planned that should we identify studies with outcome data at alternative time‐points, we would also consider these. We planned to analyse oral and inhaled antibiotics separately, however, we found no relevant studies of oral antibiotics.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Each review author independently assessed studies following the domain‐based evaluation as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Briefly, a judgement of 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' of bias was made for each of the seven domains in the Cochrane tool which are listed below.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participant personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective reporting

Other sources of bias

In the case of any disagreements between the three review authors, we aimed to reach a consensus by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes, such as change in lung function we calculated the mean difference (MD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) to measure treatment effect. If there had been more than one study included, which reported multiple variations of a similar outcome, we planned to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD) and corresponding 95% CIs.

For dichotomous outcomes such as mortality, we calculated risk ratios (RR) and corresponding CIs.

For the included studies, where SEs were reported (e.g. relative change for FEV1% predicted), in order to enter the data into 'Data and analyses' we calculated the SD using the formula: SD = SE x square root of n.

Unit of analysis issues

No cross‐over studies were included in the review. In future updates of this review, should cross‐over studies be included we plan to include data from cross‐over studies should the duration of treatment meet the inclusion criteria and if the relevant information, as described by Elbourne is available (Elbourne 2002). In such cases we plan to treat the studies as parallel studies and pool the intervention arms to be compared against the control arms, or alternatively perform analysis on the first period only, depending on the information available.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed for missing data in reported results and report the percentage of participants from whom no outcome data were obtained on the data collection form. Unless there is reason to suspect data are not missing at random, we included data on only those whose results are known in the analysis and use the total participants with complete data as the denominator rather than the total number of participants (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

There were insufficient studies to assess heterogeneity, however should more studies be conducted in the future we plan to assess heterogeneity of inconsistencies across studies using the I² statistic and interpret the I² statistic based on the thresholds of heterogeneity set out by Higgins (Higgins 2003):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent evidence of moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent evidence of substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%:may represent evidence of considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we are able to include more studies in the future, we will attempt to assess whether our review is subject to publication bias by using a funnel plot; if we detect asymmetry, we will explore causes other than publication bias.

Data synthesis

When sufficient data are available we plan to assess whether studies are clinically similar enough to combine into meta‐analyses, and if so, we will assess for heterogeneity as outlined above. If we identify at least substantial heterogeneity (higher than 50%), we will use a random‐effects model, otherwise, we will use a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct a subgroup analysis on species (B cenocepacia and B multivorans), however, we were unable to do so due to lack of studies and data. In future updates of this review, when possible, we plan to consider the potential effects of the intermittent use of acute antibiotics by undertaking a subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

If there are sufficient studies in future updates of this review (10 or more) we will review the validity of our conclusions by carrying out sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of a high risk of bias (any domain) on our results and conclusions and the effects of a fixed‐effect analysis versus a random‐effects analysis. This has not been possible to date due to a lack of eligible studies.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared a summary of findings table for the included comparison. We included reported changes in the primary outcomes FEV1 (changes in relative % predicted or volumes or both), time to next exacerbation and hospitalisations, mortality and adverse events (mild, moderate and severe). We listed population, setting, intervention and comparison and reported an illustrative risk for the experimental and control intervention with MDs re‐expressed as RRs as required (Schünemann 2011b). The grade of certainty for each outcome was adjudicated as moderate using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) (Schunemann 2006).

Results

Description of studies

Please see the relevant tables for further information (Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies).

Results of the search

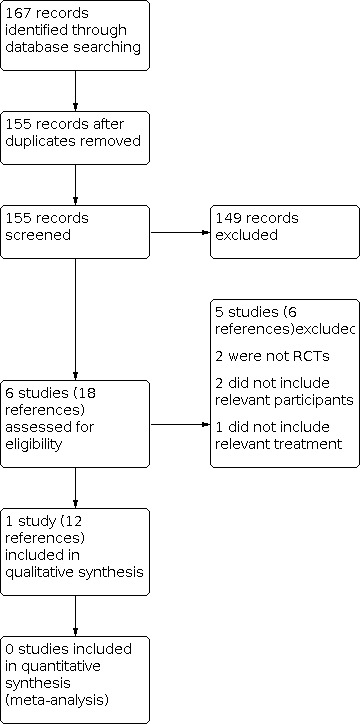

We identified a total of 167 references from the search of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register. We identified no further studies from the searches of international trials databases. After initial consideration, we removed duplicates and were left with 155 records; of these 149 were not relevant and we discounted these (Figure 1). We examined the remaining six studies (18 references), and included one study (12 references) and excluded five studies (six references) (Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included a placebo‐controlled RCT of long‐term nebulised aztreonam lysine (AZLI), which was funded by the makers of AZLI (Tullis 2014). In this study, 100 participants were included (52 AZLI, 48 placebo) across 35 adult and paediatric centres in North America. A total of 61% of participants were male, with ages ranging from 6 years to 57 years old.

Participants were randomised to receive either 24 weeks of continuous treatment of nebulised AZLI 75 mg three times a day or placebo. The primary endpoint was mean change in FEV1 % predicted. Key secondary outcomes were number of days to antibiotic use for respiratory exacerbations, hospitalisations, respiratory symptoms and change in sputum microbiology. A blinded medical reviewer adjudicated whether the use of antibiotics and hospitalisations were due to respiratory exacerbations. No restrictions on additional antibiotic use were imposed.

Excluded studies

A total of five studies were excluded. Two studies were excluded as, on further examination, they were not RCTs (Kun 1984; Waters 2017); two studies did not concern the population under review (Adeboyeku 2001; Burns 1999); and one study design did not include a relevant intervention (Ledson 2002) (Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

The overall risk of bias in the included study was assessed as 'low'. The study authors did report industry funding; however, the randomisation, blinding and outcome adjudication procedures were all conducted and reported appropriately. Further details can be found in the Characteristics of included studies and in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

The included study stratified randomisation by region. The authors justified this approach as an attempt to mitigate different treatment‐centre approaches for managing chronic Burkholderia species infection. Participants were assigned randomly 1:1 to either treatment or placebo. The sequence generation method is not reported and the risk of bias is therefore unclear.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was not reported and we therefore judged the study to have an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Participants, investigators and outcome adjudicators were all blinded to allocation. Risk of bias was therefore considered to be low for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

The included study reported that 14 participants (14%) did not continue treatment for the 24‐week study period, given the nature of the study population this does not seem excessive. Primary outcome data are reported for all participants; however, the primary outcomes results were adjusted to account for completed days in the study. One secondary outcome was reported for less than half of all participants (change in Burkholderia species sputum density at week 24), which the authors reported was due to inability to provide a sputum sample of sufficient quality for sputum density analysis. Risk of bias was therefore considered to be unclear for this domain.

Selective reporting

After review of the manuscript, supplementary material and prior results presented at conferences we found no evidence of selective reporting of outcomes. There was no statistical analysis of differences in safety outcomes reported. Our own analysis confirmed no overall difference in adverse events. The risk of bias for this domain was therefore considered to be low.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The certainty of the evidence has been graded for those outcomes included in the summary of findings table. For the definitions of these gradings, please refer to the summary of findings table (Table 1).

AZLI versus placebo

One study (100 participants) was included in the review (Tullis 2014).

Primary outcomes

1. Lung function

a. FEV1

i. Absolute change in volumes, % predicted or both

The included study did not report this outcome.

ii. Relative change in volumes, % predicted or both

The study reported the relative change in % predicted FEV1 from baseline to week 24, expressed as the mean area under curve corrected for baseline and adjusted for number of days on study. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups, MD 0.91% (95% ‐3.15 to 4.97) (moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 1: Change in FEV1

2. Pulmonary exacerbations

a. Time to next exacerbation

The included study reported median days to next antibiotic use for respiratory exacerbation (as adjudicated by a blinded medical reviewer). The estimated number of median days to next antibiotic use was for 24 days fewer in the placebo arm, however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.266) (moderate‐certainty evidence).

b. Hospitalisations

Total number of respiratory hospitalisations, number of days hospitalised for respiratory exacerbations, number and proportion of participants hospitalised at least once, and respiratory hospitalisation rate per participant year were all reported. At 24 weeks, no statistically significant differences were reported, RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.45) (moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 2: Participants hospitalised for respiratory exacerbation

c. Exacerbation rate

Exacerbation rate was not reported.

d. IV antibiotic use

IV antibiotic use was not reported separately. Instead a composite of number of unique days of IV, oral or inhaled antibiotics (or both) was reported. There were no statistically significant differences reported.

3. Adverse events

Adverse events were reported in detail, however, no statistical analysis of differences between groups is reported in the original paper. Our own analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in overall adverse events between groups (Analysis 1.4) (moderate‐certainty evidence) (Table 1).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 4: Adverse events (by severity)

a. mild: transient event, no treatment change, e.g. rash, nausea, diarrhoea

The study reported a number of mild adverse events (cough, sputum increase, pyrexia, oropharyngeal pain, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, chest discomfort, nasal congestion, nausea, fatigue, wheezing, decreased appetite, rhinorrhoea, sinus congestion, sinus headache, chest pain, lung disorder, respiratory tract congestion, chills, headache and rales). At 24 weeks, wheeze was statistically significantly higher in the AZLI group compared to placebo, RR 3.61 (95% CI 1.06 to 12.34) (Analysis 1.4), however other common adverse events including cough (RR 1.15 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.52)), dyspnoea (RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.87)) and increased sputum (RR 1.25 (95% 0.79 to 1.96)) were all similar. It was noted in the trial report that "...The wheezing observed among AZLI‐treated subjects appeared to be associated with underlying disease (asthma or prior history of wheezing), was associated with a viral infection, or was one of multiple symptoms reported for acute pulmonary exacerbation...".

b. moderate: treatment discontinued, e.g. nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, hepatitis, visual impairment

At 24 weeks, the study reported no difference between treatment groups, there were five participants in the AZLI arm who discontinued due to adverse events, no discontinuations were seen in the placebo group, RR 11.90 (95% CI 0.68 to 209.61) (Analysis 1.4).

c. severe: causing hospitalisation or death

The study reported that severe adverse events mainly consisted of respiratory exacerbations and were similar between groups at 24 weeks, RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.49 to 2.37) (Analysis 1.4). Other severe adverse events included one life‐threatening adverse event (respiratory failure) and two deaths, all of which occurred in the AZLI treatment group.

Secondary outcomes

1. Mortality

Mortality was reported in crude rates. Our own analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between groups at 24 weeks, RR 5.41 (95% CI 0.27 to 109.87) (moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 5: Mortality

2. QoL

a. Validated QoL score (e.g. CFQ‐R, CRISS score)

Relative change from baseline to week 24 for the CFQ‐R respiratory symptoms scale score was presented; no significant differences were reported, MD 0.18 (95% CI ‐4.37 to 4.73) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 6: QoL

3. BCC culture

a. Sputum density of BCC

The authors presented the average change in Log10Burkholderia species CFU/g sputum from baseline to week 24. No significant differences were reported (at 24 weeks), MD 0.93 (95% ‐0.57 to 2.43); however, it was noted that this analysis included only 15 participants in the AZLI group and 20 in the placebo group (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 7: Sputum density of BCC

4. Changes in inflammatory markers

a. Sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples

The included study did not report this outcome.

b. Serum or blood

The included study did not report this outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this review was to assess the evidence for the long‐term antibiotic therapy for chronic infection with BCC. Despite extensive searches of the literature we were only able to include one study suitable for inclusion in the review (Table 1). The included study compared 24 weeks of AZLI with placebo in people with CF and chronic BCC infection. The study appeared well‐conducted and reported most of the outcomes of interest to this review. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups and placebo in terms of lung function or exacerbations. AZLI appeared to be generally well‐tolerated, however, wheeze was significantly higher in the AZLI group compared to placebo.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

As we were only able to include one study in this review, there is a clear need for more evidence in this field. The included study investigated the use of one intervention in a broad group of participants. The availability of an increasing array of nebulised antibiotics for people with CF warrants further trials of their use in this population.

Quality of the evidence

We were only able to include one study, which, although well‐conducted, makes it likely that further studies may change the estimated effect size. Given the certainty of evidence was assessed to be moderate across all outcomes, future research is likely to have an important impact on our estimates and conclusions.

Potential biases in the review process

We are unaware of any potential biases.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are no other reviews in this setting and little in the way of observational data. Our findings of a general lack of evidence for the treatment of chronic BCC infection are in keeping with reviews of other aspects of care of people with CF and BCC (Lord 2020; Regan 2019).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found insufficient evidence from the literature to determine an effective strategy for antibiotic therapy in chronic Burkholderia cepacia complex infection.

Implications for research.

Although the included study did not report any positive findings, it served to confirm that large randomised controlled trials can be performed in this population. The high concurrent antibiotic use in the included study may make the exacerbation outcomes difficult to define and difficult to compare with other studies. The recent expansion in available nebulised antibiotics, as well as products currently in clinical trial phase should mean further clinical trials are feasible in the future.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 December 2021 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | For this update only minor changes were made throughout the review and our conclusions remain the same. |

| 2 December 2021 | New search has been performed | A search of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Cystic Fibrosis Register identified 23 potentially‐relevant references, none of which were relevant for any section of the review. No additional results were found from searches of trials registries. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 8, 2018 Review first published: Issue 6, 2019

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

The authors would like to thank Nikki Jahnke and Tracey Remmington for their support and guidance in the completion of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies ‐ trial registries

| Registry | Search terms | Date of most recent search |

| WHO ICTRP | Search terms: burkholderia OR cepacia | 22 October 2021 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov |

Advanced Search form Condition or disease: cystic fibrosis Other terms: burkholderia OR cepacia Study type: Interventional Studies (Clinical Trials) |

22 October 2021 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. AZLI versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Change in FEV1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.2 Participants hospitalised for respiratory exacerbation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.2.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.3 Overall adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.3.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4 Adverse events (by severity) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.1 Mild: cough | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.2 Mild: wheeze | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.3 Mild: dyspnoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.4 Mild: sputum increased | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.5 Moderate: discontinuation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.4.6 Severe: severe adverse events or life‐threatening | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.5 Mortality | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.5.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.6 QoL | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.6.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.7 Sputum density of BCC | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.7.1 At 24 weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: AZLI versus placebo, Outcome 3: Overall adverse events

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Tullis 2014.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT Conducted in 35 centres (USA: 34; Canada:1 (Feb 2010 ‐ Sept 2011) |

|

| Participants | 100 participants (48 given AZLI treatment; 52 given placebo) Eligible participants ≥ 6 years of age had documented CF and chronic infection with Burkholderia spp. 61 participants were male |

|

| Interventions | 24 weeks of continuous treatment with 75 mg inhaled AZLI (3 times a day) or placebo Followed by a 24‐week extension period of open‐label AZLI treatment for all participants (weeks 24 ‐ 48); and a 4‐week follow‐up period (weeks 48 ‐ 52) |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome was change in lung function (FEV1) at 24 weeks Secondary outcomes included: number of respiratory exacerbations requiring IV, oral or inhaled antibiotics (or both); number of respiratory hospitalisations; AUCave through week 24 for CF Questionnaire‐Revised (CFQ‐R) Respiratory Symptoms scores; time to respiratory exacerbation requiring IV, oral or inhaled antibiotics (or both); and adverse events |

|

| Notes | The study was funded by Gilead Sciences | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear how sequences were generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear how allocation was concealed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blinded with identical placebo |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded medical reviewer for subjective outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Some outcomes reported with significantly reduced participants. Overall, 84% of participants completed the trial and continued onto the extension period) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other potential sources of bias were identified |

AUCave: average area under the curve AZLI: aztreonam lysine FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Adeboyeku 2001 | Not relevant participants |

| Burns 1999 | Not relevant participants |

| Kun 1984 | Not a RCT |

| Ledson 2002 | Not a relevant intervention |

| Waters 2017 | Not a RCT |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Differences between protocol and review

There were no differences.

Contributions of authors

FF conceived the review and designed the protocol with input and advice from DN. MS provided advice regarding statistical methods. FF and DN wrote the manuscript (original protocol and review as well as subsequent updates).

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

None, Other

No Internal Sources of Funding

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK

This systematic review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group.

Declarations of interest

All authors (FF, MS, DN) declare no potential conflict of interests.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Tullis 2014 {published data only}

- Balfour-Lynn IM. At last, Burkholderia spp. is one of the inclusion criteria--a negative (but published) randomised controlled trial. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2014;13(3):241-2. [CFGD REGISTER: PI259i] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, LiPuma JJ, Retsch-Bogart G, Bresnik M, Henig N, McKevitt M, et al. No antibiotic cross-resistance after 1 year of continuous aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (pts) with chronic Burkholderia (BURK) infection. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2012;11 Suppl 1:S71. [ABSTRACT NO.: 58] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259d] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JL, LiPuma J, McKevitt M, Lewis S, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Bresnik M, et al. The effect of burkholderia colony morphology in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic burkholderia species in a randomized trial of Aztreonam For Inhalation Solution (AZLI). Pediatric Pulmonology 2012;47 Suppl 35:333. [ABSTRACT NO.: 307] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259g] [Google Scholar]

- EUCTR2009-011740-19-Outside-EU/EEA. Clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic burkholderia species infection. www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=EUCTR2009-011740-19-Outside-EU/EEA (first received 02 February 2015).

- NCT01059565. Safety and efficacy study of aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic burkholderia species infection. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/nct01059565 (first received 01 February 2010).

- Tullis DE, Burns JL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Bresnik M, Henig NR, Lewis SA, et al. Inhaled aztreonam for chronic Burkholderia infection in cystic fibrosis: a placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2014;13(3):296-305. [CFGD REGISTER: PI259h] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis DE, Burns JL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Bresnik M, Henig NR, Lewis SA, et al. Inhaled aztreonam for chronic Burkholderia infection in cystic fibrosis: a placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2014;13(3):296-305. Online Supplementary Appendix. [CFGD REGISTER: PI259j] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tullis E, Burns J, Retsch-Bogart G, Bresnik M, Henig N, Lewis S, et al. Aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic Burkholderia species (BURK) infection: final results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2012;11 Suppl 1:S11. [ABSTRACT NO.: WS5.4] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259e] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis E, Burns JL, Retsch-Bogart G, Bresnik M, Henig Nr, Lewis S, et al. Aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic burkholderia species (Burk) infection: initial results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatric Pulmonology 2011;46 Suppl 34:296. [ABSTRACT NO.: 234] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259b] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis E, Burns JL, Retsch-Bogart G, Bresnik M, Lewis S, Montgomery AB, et al. Aztreonam 75 mg powder and solvent for nebuliser solution (AZLI) in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic Burkholderia species (Burk) infection: baseline demographics and microbiology from randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2011;10 Suppl 1:S22. [ABSTRACT NO.: 85] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259c] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis E, Burns JL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Bresnik M, Lewis S, LiPuma J. Lung function in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic burkholderia (BURK) species infection over the course of a prospective, randomized trial of aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI). Pediatric Pulmonology 2012;47(S35):334. [ABSTRACT NO.: 310] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259f] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis E, LiPuma JJ, Retsch-Bogart G, Bresnik M, Henig N, McKevitt M, et al. Effects of continuous aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) use on pathogens and antibiotic susceptibility in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic Burkholderia species infection. Pediatric Pulmonology 2011;46 Suppl 34:305. [ABSTRACT NO: 257] [CFGD REGISTER: PI259a] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Adeboyeku 2001 {published data only}

- Adeboyeku DU, Agent P, Jackson V, Hodson M. A double blind randomised study to compare the safety and tolerance of differing concentrations of nebulised colistin administered using HaloLite in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Pediatric Pulmonology 2001;32 Suppl 22:288. [CFGD REGISTER: PI165] [Google Scholar]

Burns 1999 {published data only}

- Burns JL, Van Dalfsen JM, Shawar RM, Otto KL, Garber RL, Quan JM, et al. Effect of chronic intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin on respiratory microbial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1999;179(5):1190-6. [CFGD REGISTER: PI120i] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kun 1984 {published data only}

- Kun P, Landau LI, Phelan PD. Nebulized gentamicin in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Australian Paediatric Journal 1984;20(1):43-5. [CFGD REGISTER: PI106] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ledson 2002 {published data only}

- Ledson MJ, Gallagher MJ, Cowperthwaite C, Robinson M, Convery RP, Walshaw MJ. A randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover trial of nebulised taurolidine in adult CF patients colonised with B Cepacia. In: 22nd European CF Conference;1998 Jun 13-19; Berlin. 1998:120. [ABSTRACT NO.: PS5-17]

- Ledson MJ, Gallagher MJ, Robinson M, Cowperthwaite C, Williets T, Hart CA, et al. A randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled crossover trial of nebulized taurolidine in adult cystic fibrosis patients infected with Burkholderia cepacia. Journal of Aerosol Medicine 2002;15(1):51-7. [CFGD REGISTER: PI128b] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Waters 2017 {published data only}

- Waters V, Yau Y, Beaudoin T, Wettlaufer J, Tom SK, McDonald N, et al. Pilot trial of tobramycin inhalation powder in cystic fibrosis patients with chronic Burkholderia cepacia complex infection. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2017;16(4):492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Aris 2001

- Aris RM, Routh JC, LiPuma JJ, Heath DG, Gilligan PH. Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis patients with Burkholderia cepacia complex. Survival linked to genomovar type. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2001;164(11):2102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bell 2005

- Bell SC, Senini SL, McCormack JG. Macrolides in cystic fibrosis. Chronic Respiratory Disease 2005;2(2):85-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgel 2015

- Burgel PR, Bellis G, Olesen HV, Viviani L, Zolin A, Blasi F, et al. Future trends in cystic fibrosis demography in 34 European countries. European Respiratory Journal 2015;46(1):133-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CFF 2016

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 2015 Annual Data Report. www.cff.org/Our-Research/CF-Patient-Registry/2015-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf (accessed 03 April 2018).

CF Trust 2017

- Jeffery A, Charman S, Cosgriff R, Carr S. 2016 Annual Data Report. UK CF Registry 2017.

Corey 1997

- Corey M, Edwards L, Levison H, Knowles M. Longitudinal analysis of pulmonary function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics 1997;131(6):809-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drevinek 2010

- Drevinek P, Mahenthiralingam E. Burkholderia cenocepacia in cystic fibrosis: epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of virulence. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2010;16(7):821-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elbourne 2002

- Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Higgins JP, Curtin F, Worthington HV, Vail A. Meta-analyses involving cross-over trials: methodological issues. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Farrell 2008

- Farrell PM. The prevalence of cystic fibrosis in the European Union. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2008;7(5):450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibson 2003

- Gibson RL, Emerson J, McNamara S, Burns JL, Rosenfeld M, Yunker A, et al. Significant microbiological effect of inhaled tobramycin in young children with cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2003;167(6):841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JA, editor(s) on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Higgins 2011b

- Higgins JP, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, editor(s) on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Jones 2004

- Jones AM, Dodd ME, Govan JR, Barcus V, Doherty CJ, Morris J, et al. Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia multivorans: influence on survival in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2004;59(11):948-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ledson 1998

- Ledson MJ, Gallagher MJ, Corkill JE, Hart CA, Walshaw MJ. Cross infection between cystic fibrosis patients colonised with Burkholderia cepacia. Thorax 1998;53(5):432-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2003

- Lee TW, Brownlee KG, Conway SP, Denton M, Littlewood JM. Evaluation of a new definition for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. Journal of Cystic FIbrosis 2003;2(1):29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

LiPuma 2010

- LiPuma JJ. The changing microbial epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2010;23(2):299-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lord 2020

- Lord R, Jones AM, Horsley A. Antibiotic treatment for Burkholderia cepacia complex in people with cystic fibrosis experiencing a pulmonary exacerbation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 4. Art. No: CD009529. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009529.pub4] [CD009529] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mahenthiralingam 2001

- Mahenthiralingam E, Vandamme P, Campbell ME, Henry DA, Gravelle AM, Wong LT, et al. Infection with Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovars in patients with cystic fibrosis: virulent transmissible strains of genomovar III can replace Burkholderia multivorans. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001;33(9):1469-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

Mahenthiralingam 2002

- Mahenthiralingam E, Baldwin A, Vandamme P. Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2002;51(7):533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCoy 2008

- McCoy KS, Quittner AL, Oermann CM, Gibson RL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Montgomery AB. Inhaled aztreonam lysine for chronic airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2008;178(9):921-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2017

- NICE. Cystic fibrosis: diagnosis and management. National Institue of Clinical Excellence 2017. [PubMed]

Ramsey 1999

- Ramsey BW, Pepe MS, Quan JM, Otto KL, Montgomery AB, Williams-Warren J, et al. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Inhaled Tobramycin Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 1999;340(1):23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Regan 2019

- Regan KH, Bhatt J. Eradication therapy for Burkholderia cepacia complex in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, Issue 4. Art. No: CD009876. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009876.pub4] [CD009876] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Retsch‐Bogart 2008

- Retsch-Bogart GZ, Burns JL, Otto KL, Liou TG, McCoy K, Oermann C, et al. A phase 2 study of aztreonam lysine for inhalation to treat patients with cystic fibrosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Pediatric Pulmonology 2008;43(1):47-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ryan 2011

- Ryan G, Singh M, Dwan K. Inhaled antibiotics for long-term therapy in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 3. Art. No: CD001021. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001021] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schünemann 2011b

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, et al on behalf of the Cochrane Applicability and Recommendations Methods Group and the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Southern 2012

- Southern KW. Macrolide antibiotics for cystic fibrosis. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2012;13(4):228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vandamme 2011

- Vandamme P, Dawyndt P. Classification and identification of the Burkholderia cepacia complex: past, present and future. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2011;34(2):87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wales 1999

- Wales D, Woodhead M. The anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides. Thorax 1999;54 Suppl 2:S58-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weber 1995

- Weber A, Williams-Warren J, Ramsey B, Smith AL. Tobramycin serum concentrations after aerosol and oral administration in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Therapeutics 1995;2(2):81-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zlosnik 2015

- Zlosnik JE, Zhou G, Brant R, Henry DA, Hird TJ, Mahenthiralingam E, et al. Burkholderia species infections in patients with cystic fibrosis in British Columbia, Canada. 30 years' experience. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2015;12(1):70-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Frost 2018

- Frost F, Shaw M, Nazareth D. Antibiotic therapy for chronic infection with Burkholderia cepacia complex in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 8. Art. No: CD013079. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013079] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]