Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal injuries (MSkIs) are a leading cause of health care utilization, as well as limited duty and disability in the US military and other armed forces. MSkIs affect members of the military during initial training, operational training, and deployment and have a direct negative impact on overall troop readiness. Currently, a systematic overview of all risk factors for MSkIs in the military is not available.

Methods

A systematic literature search was carried out using the PubMed, Ovid/Medline, and Web of Science databases from January 1, 2000 to September 10, 2019. Additionally, a reference list scan was performed (using the “snowball method”). Thereafter, an international, multidisciplinary expert panel scored the level of evidence per risk factor, and a classification of modifiable/non-modifiable was made.

Results

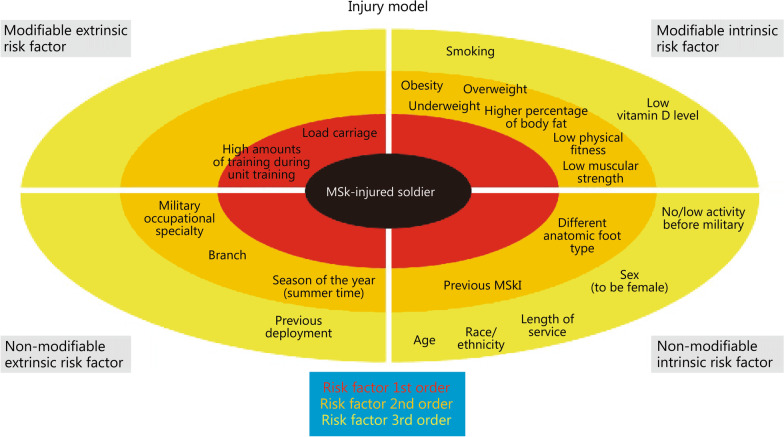

In total, 176 original papers and 3 meta-analyses were included in the review. A list of 57 reported potential risk factors was formed. For 21 risk factors, the level of evidence was considered moderate or strong. Based on this literature review and an in-depth analysis, the expert panel developed a model to display the most relevant risk factors identified, introducing the idea of the “order of importance” and including concepts that are modifiable/non-modifiable, as well as extrinsic/intrinsic risk factors.

Conclusions

This is the qualitative systematic review of studies on risk factors for MSkIs in the military that has attempted to be all-inclusive. A total of 57 different potential risk factors were identified, and a new, prioritizing injury model was developed. This model may help us to understand risk factors that can be addressed, and in which order they should be prioritized when planning intervention strategies within military groups.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40779-021-00357-w.

Keywords: Military, Musculoskeletal injuries, Risk factors, Prevention, Intervention, Injury

Background

Musculoskeletal injuries (MSkIs) are a leading cause of health care utilization, as well as limited duty and disability in the US military [1] and other armed forces [2–6]. MSkIs affect members of the military during initial training [7], operational training [8], and deployment [9], and have a direct negative impact on overall troop readiness. MSkIs have been shown to make up 50% of disease and non-battle injury (DNBI) casualties, and 43% of DNBI casualties requiring evacuation. Additionally, many service members sustain MSkIs, which are treated conservatively in the theater during deployment, but eventually require surgery following a combat tour [10, 11]. The consequences of MSkIs are reduced individual fitness and health [12], and ultimately discharge from military duty [13, 14].

As such, the prevention of MSkIs is considered a main target area to increase the readiness, performance, and health of military personnel. Approaches include the identification of risk factors and purposeful intervention strategies to reduce MSkIs. In recent decades, hundreds of original studies have been published with the goal of identifying risk factors for MSkIs, including narrative and systematic reviews on specific risk factors [15–26]. However, an overall summary of the published data on risk factors for MSkIs in the military is not available. Further, for several risk factors, such as sex, there is an ongoing debate on whether there is a direct association with an increased risk of MSkIs, or whether the association is indirect via a confounding risk factor [27]. Finally, there is no model that clarifies the relative order of importance of the risk factors for MSkIs in the military.

Given the gaps in knowledge identified above and the fact that soldier readiness is of great importance to all allied militaries, the multidisciplinary NATO Science and Technology Organization (STO) Research Task Group (RTG) 283 on “Reducing musculoskeletal injuries” set out to perform a systematic review of risk factors for MSkIs in the military to address and discuss the facilitation of successful interventions.

Methods

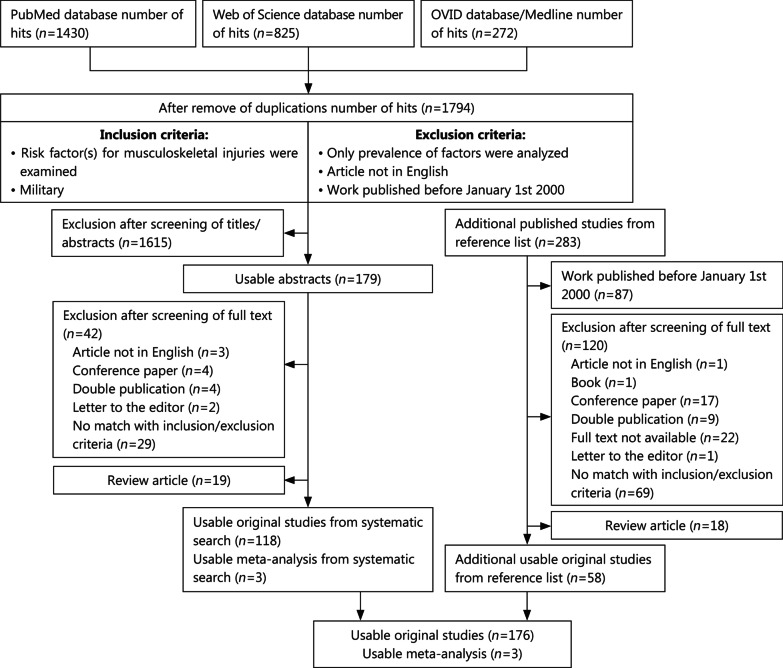

A systematic literature search considering the PRISMA guidelines [28] was initiated using the PubMed, Ovid/Medline, and Web of Science databases with the search terms “(military) AND ((injury) OR (trauma)) AND ((basic training) OR (physical training))” with all MeSH terms (see details on Additional file 1) on September 10, 2019. The principal criterion for inclusion was that the study reported on risk factors for MSkIs in a military population. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a language other than English; studies without a risk factor evaluation; and studies published before January 1, 2000. Review articles (without a meta-analysis) were used to find the included original works (see below), but were not included as such in this review. Of the 1794 studies identified (after removing duplicates), 179 were selected for full-text analysis. After full-text analysis, 42 papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 19 studies were reviews and did not present new information. So far, a total of 118 original papers and 3 meta-analyses have been included.

Moreover, to present a complete overview, a reference list scan (using the “snowball method”) [29] was performed on each of the 179 fully analyzed texts, including each of the 19 review articles. With this approach, an additional 283 studies were identified, of which 87 were excluded due to the publication date being before January 1, 2000. The remaining 196 papers were also read in full to determine relevance. If two studies reported on exactly the same population, only the publication that provided the most details was included. As a result, an additional 58 studies were included in this review, bringing the total to 176 original papers and 3 meta-analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review

Once all the literature was identified, a list of all reported risk factors was created. Each original paper and meta-analysis was then assigned to a risk factor. If an original paper described multiple risk factors, it was assigned to every risk factor it reported.

In the results section, a general description of all the included publications is provided first, followed by specific descriptions per risk factor. Risk factors were sorted into different groups (in alphabetical order): lifestyle factors, medical factors, occupational factors, physiological factors, social factors, and training factors. For each risk factor, an accompanying table was included that summarizes each aspect of the supporting studies: lead author; year of publication; country of origin; characteristics of the population examined (branch and unit/type of military activity); study type (retrospective or prospective); sample size of the population studied; and whether or not the study concluded that the risk factor was correlated to MSkIs (yes or no). In a number of publications, more than one risk factor was evaluated.

Finally, the multidisciplinary expert panel (consisting of all coauthors of this review) classified the evidence supporting the association between a risk factor and MSkI into one of five categories: strong, moderate, weak, insufficient, or no evidence. For this classification, the expert panel took into account the results of the studies, as well as the number of participants and their professional experience in military MSkI injury prevention. In addition, the expert panel included a determination as to whether a risk factor would be considered modifiable or non-modifiable in the military context. A risk factor was defined as modifiable if a service member could influence it (e.g., to be a smoker) or if military authorities could influence it (e.g., by changing the training schedule or by providing other gear). Risk factors classified as non-modifiable are beyond personal control (e.g., the weather). Whether a risk factor is modifiable is a significant determinant for the application of intervention strategies. Based on the literature review and an in-depth analysis, the multidisciplinary expert panel developed a model to classify the different risk factors identified, introducing the concept of “order of importance” and including the notions of modifiable/non-modifiable and extrinsic/intrinsic risk factors.

Results

Of the 176 original papers, 101 came from investigations in the US Armed Forces. Additional investigations were conducted in the armed forces of the UK (19 studies), Israel (18 studies), and Finland (14 studies). Australia and Switzerland produced 4 studies each, China and Greece had 3 studies each, Germany had 2 studies, and Belgium, Denmark, India, Iran, Malta, Poland, Slovenia, and Sweden were represented by 1 study each. A majority of the studies examined risk factors in the army (113 studies), whereas there were considerably fewer studies conducted in the marines (16 studies), the air force (7 studies), the navy (5 studies), and the special operations forces (2 studies). Seven studies explored risk factors, including multiple armed services branches; 4 studies were conducted only among recruits or participants in academy training, and 22 studies did not include descriptions of the particular service branch. More than half of the studies (n = 101) chose a prospective study design, and the remaining 75 papers evaluated data retrospectively. The study populations ranged from 20 subjects [30] to 5,580,875 analyzed person-years [31]. In two studies [32, 33], no information about the underlying size of the population was reported. Less than half of the studies (n = 79) scrutinized populations of less than 1000 participants, while 27 studies had a population greater than 10,000 participants. A number of retrospective studies involved populations with over 100,000 participants [31, 34–51]. A large minority of the studies included both male and female military personnel (n = 51). In 33 studies, only male members were included, whereas 17 studies focused exclusively on women in the military. In most of the studies (n = 75), no specific information was given about the sex of the included participants.

Lifestyle factors

Alcohol intake

Nine studies focused on higher alcohol intake as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). Five studies were conducted in the US Army, 2 within the British Army, and 1 in Finland and in Greece. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 64 to 4139 participants. Three of the 9 studies identified alcohol intake as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 6 did not show a significant association between alcohol intake and MSkIs.

Table 1.

Summary of studies that focused on alcohol intake, calcium intake, milk consumption, vegetable consumption, vegetarian diet, sleep time, and smoking as risk factors for MskIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol intake | |||||||

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 1156 M, 746 F | No |

| Chatzipapas [53] | 2008 | Greece | n/a | Active duty | R | 64 | No |

| Cosio-Lima [54] | 2013 | USA | Army | Sergeants Major Academy | R | 149 | No |

| Lappe [55] | 2005 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 4139 F | Yes (F) |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | Yes (F) |

| Robinson [57] | 2016 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 1810 | No |

| Schneider [58] | 2000 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | R | 1214 | Yes |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | No (M) |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Calcium intake (low) | |||||||

| Chatzipapas [53] | 2008 | Greece | n/a | Active duty | R | 64 | No |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | No (M) | |

| Moran [62] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Recruits of elite combat unit | P | 116 | No |

| Moran [63] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Elite combat unit BCT | P | 74 | Yes |

| Milk consumption (low) | |||||||

| Cosman [64] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 755 M, 136 F | No |

| Moran [62] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Recruits of elite combat unit | P | 116 | No |

| Sanchez-Santos [65 | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | Yes (M) |

| Vegetables consumption | |||||||

| Robinson [57] | 2016 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 1810 | No |

| Sanchez-Santos [65] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | No (M) |

| Vegetarian diet | |||||||

| Dash [66] | 2012 | India | Army | Recruits | P | 8570 | Yes |

| Sleep time (reduced) | |||||||

| Kovcan [67] | 2019 | Slovenia | Army | Infantry, active duty | R | 118 M, 11 F | No |

| Wyss [68] | 2014 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1676 | Yes |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Altarac [69] | 2000 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 187 M, 915 F | Yes |

| Anderson [70] | 2015 | USA | Army | Light Infantry Brigade | R | 2101 | Yes |

| Anderson [71] | 2017 | USA | Army | Light Infantry | R | 4384 M, 363 F | No |

| Bedno [72] | 2013 | USA | Army | IET | P | 8456 M | Yes |

| Bedno [35] | 2019 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 238,772 | Yes |

| Brooks [73] | 2019 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 1460 M, 540 F | Yes |

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 1156 M, 746 F | Yes |

| Chatzipapas [53] | 2008 | Greece | n/a | Active duty | R | 64 | No |

| Cosio-Lima [54] | 2013 | USA | Army | Sergeants Major Academy | R | 149 | No |

| Cosman [64] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 755 M, 136 F | Yes |

| Cowan [74] | 2012 | USA | Army | Trainees | P | 1568 F | No |

| Cowan [75] | 2011 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 7323 | Yes |

| Davey [76] | 2015 | UK | Marines | P | 1090 M | Yes | |

| Fallowfield [77] | 2018 | UK | Air Force | Recruits | P | 990 M, 203 F | Yes |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | Yes (less) | |

| Grier [78] | 2017 | USA | Army | Infantry brigades | R | 4236 M | No |

| Grier [79] | 2010 | USA | Multiple | R | 24,177 M | Yes | |

| Kelly [80] | 2000 | USA | Navy | Recruits BCT | R | 86 F | No |

| Knapik [81] | 2010 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | P | 1042 M, 375 F | Yes |

| Knapik [82] | 2013 | USA | Army | Army military police training | P | 1838 M, 553 F | Yes## |

| Knapik [83] | 2013 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | P | 805 | No |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Knapik [85] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 182 M, 168 F | Yes |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | No |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | Yes |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 840 M, 571 F | Yes (M), No (F) |

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | No |

| Lappe [55] | 2005 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 4139 F | Yes |

| Kovcan [67] | 2019 | Slovenia | Army | Infantry, active duty | R | 118 M, 11 F | Yes |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | Yes |

| Lauder [90] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | P | 230 F | No (F) |

| Munnoch [91] | 2007 | UK | Marines | P | 1115 M | Yes | |

| Nagai [92] | 2017 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | P | 275 | Yes |

| Pihlajamäki [93] | 2019 | Finland | n/a | R | 4029 M | No | |

| Psaila [94] | 2017 | Malta | n/a | Recruits BCT | P | 114 M, 13 F | No |

| Rappole [95] | 2017 | USA | Army | Army Brigade | R | 1099 | Yes |

| Reynolds [96] | 2009 | USA | Army | Infantry | P | 181 | Yes |

| Reynolds [97] | 2002 | USA | Army | Construction engineers & Combat artillery soldiers | P | 313 | No |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | Yes |

| Robinson [57] | 2016 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 1810 | No |

| Roos [99] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 651 M | Yes |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | No |

| Sanchez-Santos [65] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | No |

| Scheinowitz [101] | 2017 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 350 F | No |

| Schneider [58] | 2000 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | R | 1214 | No |

| Sharma [102] | 2019 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 562 M | Yes |

| Sharma [103] | 2011 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 468 M | Yes |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | No (M) |

| Taanila [104] | 2015 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 1411 M | Yes |

| Trone [105] | 2014 | USA |

Marine Corp Air Force Army |

Recruits BCT | R | 900 M, 597 F | Yes |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | No |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Wunderlin [107] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 230 M | Yes |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | No |

BCT basis combat training; n/a Not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI); #Deployment; ##Former smoking

There is insufficient scientific evidence for alcohol intake as a modifiable risk factor.

Calcium intake (low)

Four studies focused on low (daily) calcium intake as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). Three studies were conducted in the Israel Defense Force (IDF) and one in the Armed Forces of Greece. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 64 to 2306 participants. Only the study with one of the smallest populations identified low daily calcium intake as a risk factor for MSkIs. The other three studies, including one with more than 2000 participants, did not find a significant association.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for low (daily) calcium intake as a modifiable risk factor.

Milk consumption (low)

Three studies focused on milk consumption as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). The research was conducted within the militaries of Israel, the USA, and the UK (1 study from each country). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 116 to 1082 participants. Only one study identified low milk consumption as a risk factor for MSkIs; the other two studies did not find a significant association.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for low milk consumption as a modifiable risk factor.

Vegetable consumption

Two studies focused on the amount of vegetables eaten (as measured via a self-report questionnaire) as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). The research was conducted within different branches of the UK military. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 1082 to 1810 participants. Neither study found a significant association between the amount of vegetable consumption and MSkIs.

There is no scientific evidence for the amount of vegetable consumption as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Vegetarian diet

Only one study focused on a vegetarian diet as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). This study was conducted within the Indian Army. In this study, with 8570 participants, a vegetarian diet was identified as a risk factor for stress fractures.

There is weak scientific evidence for a vegetarian diet as a modifiable risk factor.

(Reduced) sleep time

Two studies focused on little time for sleep as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). These studies were conducted within the Army of Switzerland and the Army of Slovenia. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 129 to 1676 participants. A larger study identified little time for sleep as a risk factor for MSkIs; however, this was not observed within the smaller study.

There is weak scientific evidence for little time for sleep as a modifiable risk factor.

Smoking

Fifty-four studies focused on smoking as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 1). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (32 studies); additional studies were conducted within the militaries of the UK (8 studies), Finland (5 studies), China, Israel, Switzerland (2 studies from each) and Greece, Malta and Slovenia (1 study from each nation). The study populations ranged from 64 to 238,772 participants. Twenty-seven studies identified smoking as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 23 studies did not find a significant association between smoking and MSkI. One study found a significant increase in MSkIs related to a lower level of smoking, and one study found that former smoking habits were a significant risk factor for MSkIs. In one study, the association between smoking and increased risk for MSkIs was found only for males (not for females). A meta-analysis, which included 18 studies, found that smoking increases the risk for MSkIs, for males by 26% (a low level of smoking) up to 84% (a high level of smoking) and for females by 30% (low level of smoking) up to 56% (high level of smoking) [24]. For both sexes together, the increased risk ranges from 27 to 71%.

There is strong scientific evidence for smoking as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs. Smoking is associated with a 27–71% increased risk of MSkIs.

Medical factors

Current illness

The term “current illness” was used to describe the situation where an injured person was ill (e.g., with influenza at the time the MSkI occurred). There was only one study on current illness as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). The study was conducted in 2010 in the US Armed Forces. With 24,177 male participants, this study found a significant association between current illness and an increased risk for MSkIs. It must be noted that the risk factor “current illness” may represent a bias. Soldiers with an identified current illness are generally removed from active duty and training. This means that current illness is a risk factor mostly based on retrospective self-report by the service member.

Table 2.

Summary of studies that focused on current illness, prior pregnancy, prescription of contraceptives, prescription of NSAIDs, previous MSkIs, serum iron/serum ferritin, and vitamin D status as risk factors for MSkIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current illness | |||||||

| Grier [79] | 2010 | USA | Multiple | R | 24,177 M | Yes (M) | |

| Prescription of contraceptives | |||||||

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 920 F | No |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 571 F | No |

| Scheinowitz [101] | 2017 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 350 F | No |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No |

| Prescription of NSAID | |||||||

| Hughes [50] | 2019 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 120,730 | Yes |

| Previous MSkI | |||||||

| Cameron [110] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 630 M, 84 F | Yes |

| Cosman [64] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 755 M, 136 F | No |

| Evans [111] | 2005 | USA | Army | R | 1532 | Yes | |

| Finestone [112] | 2011 | Israel | Army | Elite infantry soldier | P | 77 M | No (M) |

| Garnock [113] | 2018 | Australia | Navy | Recruits | P | 95 M, 39 F | Yes |

| George [114] | 2012 | USA | Army | Combat medics | P | 1230 | Yes |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | Yes (M) (invers) | |

| Hill [115] | 2013 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 83,323 | Yes |

| Knapik [81] | 2010 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | P | 1042 M, 375 F | No |

| Knapik [82] | 2013 | USA | Army | Army military police training | P | 1838 M, 553 F | Yes (M), No (F) |

| Knapik [116] | 2013 | USA | Army | Combat engineer enlisted trainees | P | 1633 | Yes |

| Knapik [83] | 2013 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | P | 805 | No |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | Yes |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | No (M), Yes (F) |

| Kovcan [67] | 2019 | Slovenia | Army | Infantry, active duty | R | 118 M, 11 F | Yes |

| Kucera [117] | 2016 | USA | Army | Cadets | P | 9811 | Yes |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | No (F) |

| Lisman [118] | 2013 | USA | Marines | Officer candidate training | P | 874 | Yes |

| Monnier [119] | 2019 | Sweden | Marines | Training course | P | 48 M, 5 F | Yes |

| Rice [120] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 147 M | Yes (M) (invers) |

| Robinson [57] | 2016 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 1810 | Yes |

| Roos [99] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 651 M | Yes (M) |

| Roy [121] | 2014 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 625 F | Yes (F) |

| Schneider [58] | 2000 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | R | 1214 | Yes |

| Scott [122] | 2015 | USA | Army | Reserve Officer Training | R | 165 M, 30 F | No |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No (F) |

| Taanila [123] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 944 M | Yes (M) |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | Yes (M) |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | Yes |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | Yes## (M) |

| Prior pregnancy | |||||||

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 920 F | Yes |

| Serum iron/serum ferritin | |||||||

| Merkel [124] | 2008 | Israel | Army | Infantry/non-combatant (medics) | P | 83 M, 355 F | Yes |

| Moran [125] | 2008 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 227 F | Yes (F) |

| Vitamin D status | |||||||

| Burgi [126] | 2011 | USA | Navy | Recruits | P | 2300 F | Yes (F) |

| Davey [127] | 2016 | UK | Marines | P | 1082 M | Yes (M) | |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | Yes (M) | |

| Sanchez-Santos [65] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | No (M) |

BCT basis combat training; n/a not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females; NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI); #Deployment; ##Only for fractures

There is weak scientific evidence for current illness as a non-modifiable risk factor.

The prescription of contraceptives

Four studies focused on the prescription of contraceptives as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (3 studies). An additional study was conducted within the IDF. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 350 to 2962 participants. None of the four studies identified the prescription of contraceptives as a risk factor for MSkIs.

There is no scientific evidence for the prescription of contraceptives as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

The prescription of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Only one study focused on the prescription of a NSAID as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). This study was conducted within the US Army. In this retrospective study, with 120,730 participants, the prescription of a NSAID was identified as a risk factor for MSkIs (specifically stress fractures). There may be a bias between NSAID use and increased risk for a stress fracture because with the medication, soldiers may have stayed in training longer and consequently were more likely to suffer a fracture. Therefore, this study also explored the relationship with a subset who were taking NSAIDs for non-pain or injury reasons and found a similar relationship with increased risk for MSkIs.

There is weak scientific evidence for prescription for a NSAID as a modifiable risk factor.

Previous MSkIs

Thirty studies focused on previous MSkIs as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (18 studies); the remaining research was conducted within the militaries of the UK (3 studies), Israel and China (2 studies from each), Australia, Finland, Slovenia, Sweden, and Switzerland (1 study from each nation). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 53 to 83,323 participants. Nineteen of the 30 studies identified an earlier MSkI as a risk factor for MSkIs; 7 studies did not find a significant association. Two studies found a significant association only for one sex but not the other. The remaining two studies found that an earlier MSkI reduced the risk for MSkIs.

There is strong scientific evidence for earlier MSkIs as a non-modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Prior pregnancy

Only one study focused on prior pregnancy as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). This study was conducted within the US Army. In this study, with 920 female participants, prior pregnancy > 7 months prior was identified as a risk factor for MSkIs.

There is weak scientific evidence for prior pregnancy as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Serum iron/serum ferritin (lower)

Two studies focused on serum iron/serum ferritin as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). Both studies were conducted within the IDF. The sizes of the study populations were 227 and 438 participants. Both studies identified low serum iron/serum ferritin as a risk factor for MSkIs.

There is weak scientific evidence for low serum iron/serum ferritin as a modifiable risk factor.

Vitamin D status [low level of 25(OH)D]

Four studies focused on vitamin D status as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 2). The studies were conducted within the militaries of the UK (2 studies), Israel, and the US (1 study from each country). The sizes of the populations of both UK studies [65, 127] were the same. The study populations ranged from 1082 to 2306 participants. Three studies identified low vitamin D status as a risk factor for MSkIs, while another study did not find a significant association. The two studies from the UK reported different outcomes. Davey et al. [127] reported a significant difference in vitamin D level for participants who have suffered a stress fracture when compared to a group that did not [(64.2 ± 28.2) nmol/L for participants with stress fracture vs. (78.6 ± 35.9) nmol/L for participants without a stress fracture, P = 0.004]. Alternatively, Sanchez-Santos et al. [65] presented the results as odds ratios with a cutoff value for a low level of vitamin D at 50 nmol/L. They found no difference in the likelihood of stress fractures between the groups above and below the vitamin D level cutoff (P = 0.077).

In a meta-analysis by Dao et al. [23], it was reported that the mean serum 25(OH)D level was lower in stress fracture cases than in controls at the time of entry into basic training. The mean serum 25(OH)D level was also lower in the stress fracture cases at the time of stress fracture diagnosis.

There is moderate scientific evidence for a low level of vitamin D status as a modifiable risk factor.

Occupational factors

Branch

Three studies focused on membership in different branches as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). Two studies were conducted within the US Armed Forces and 1 within the Army of Finland. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 982 to 423,581 participants. All 3 studies identified membership to different branches as a risk factor for MSkIs.

Table 3.

Summary of studies that focused on branch, length of service, load carriage, MOS, previous deployment, and status (active vs. reserve) as risk factors for MskIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branch | |||||||

| Cameron [44] | 2010 | USA | Multiple | Active duty | R | 423,581 | Yes |

| Owens [128] | 2009 | USA | Army, Marines, Navy, Air Force | Active duty | R | 19,730 | Yes |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | Yes (M) |

| Length of service | |||||||

| Hill [115] | 2013 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 83,323 | Yes |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | Yes |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | Yes |

| Mattila [38] | 2007 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 149,750 M, 2345 F | No |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | No |

| Schermann [129] | 2018 | Israel | Army | Infantry unit vs. female unit working with dogs## | R | 7949 | Yes |

| Scott [122] | 2015 | USA | Army | Reserve Officer Training | R | 165 M, 30 F | Yes |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Load carriage | |||||||

| Constantini [130] | 2010 | Israel | Army | Border Police Infantry | P | 1423 F | Yes (F) |

| Knapik [83] | 2013 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | P | 805 | Yes |

| Konitzer [131] | 2008 | USA | n/a | Active duty# | R | 863 | Yes |

| Rappole [132] | 2018 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 368 F | No (F) |

| Roy [133] | 2012 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | P | 246 M, 17 F | Yes |

| Roy [134] | 2015 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | R | 536 M, 57 F | Yes |

| MOS | |||||||

| Anderson [71] | 2017 | USA | Army | Light Infantry | R | 4384 M, 363 F | No |

| Darakjy [8] | 2006 | USA | Army | Active duty | P | 4101 M, 413 F | Yes |

| Roy [135] | 2011 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team | P | 3066 patient encounters | Yes |

| Schermann [129] | 2018 | Israel | Army | Infantry unit vs. female unit working with dogs | R | 7949 | Yes |

| Schwartz [136] | 2018 | Israel | Army | Combat units | R | 19,791 M | Yes (M) |

| Sefton [137] | 2016 | USA | Army | Recruits IET | P | 1788 M | Yes (M) |

| Sharma [138] | 2017 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 5708 | Yes |

| Previous deployment | |||||||

| Hill [115] | 2013 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 83,323 | Yes |

| Konitzer [131] | 2008 | USA | n/a | Active duty# | R | 863 | Yes |

| Roy [121] | 2014 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 625 F | Yes (F) |

| Skeehan [139] | 2009 | USA | Army, Marine, Navy | Active duty# | R | 3367 | No |

| Status (active vs. reserve) | |||||||

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 1156 M, 746 f |

No (M) Yes (F) |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | Yes (invers) |

| Skeehan [139] | 2009 | USA | Army, Marine, Navy | Active duty# | R | 3367 | Yes |

BCT basis combat training; IET initial entry training; n/a not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) Risk factor only for females; MOS Military occupational specialty

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI); #Deployment; ##LOS examined in month of service

There is strong scientific evidence for branches as a non-modifiable risk factor for MSkI.

Length of service

Eight studies focused on the length of service as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). Half of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (4 studies), and the remaining studies were conducted within the militaries of Finland (2 studies), Israel, and the UK (1 study from each country). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 195 to 152,095 participants. Five studies identified that military servicemen and servicewomen with a longer length of service have an increased risk for MSkIs; 3 studies did not find a significant association. Two of the largest studies only examined conscripts (Kuikka et al. [36] and Mattila et al. [38]), with a small range of lengths of service, and found conflicting results. Hill et al. [115] included a broad range of active duty personnel and showed a strong association for military servicemen and women with more than 10 years of service for an increased risk of MSkIs. Reynolds et al. [98] and Wilkinson et al. [60] detected no association, but had only a small range of lengths of service.

There is moderate scientific evidence for length of service as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Load carriage

Six studies focused on load carriage as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). Most of the research was conducted in the US Armed Forces (5 studies); the remaining study was conducted within the IDF. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 263 to 1423 participants. Five studies identified body-borne load as a risk factor for MSkIs, with 3 of the 5 studies reporting load via self-report. One study found no association between load carriage and the risk for MSkIs.

There is strong scientific evidence for body-borne load as a modifiable risk factor for MSkI.

Military occupational specialty (MOS)

Seven studies focused on military occupational specialties (MOS) as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). Most of the research was conducted within the US Armed Forces, 2 studies were from the IDF, and only 1 study was from the military of the UK. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 1788 to 19,791 participants. All but one study (with light infantry) identified membership in different MOSs as a risk factor for MSkIs.

There is strong scientific evidence for MOS as a non-modifiable risk factor for MSkI.

Previous deployment

Four studies focused on previous deployment as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). All 4 studies were conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 625 to 83,323 participants. Three of the 4 studies identified previous deployment as a risk factor for MSkI, and 1 study did not find a significant association.

There is moderate scientific evidence for previous deployment as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Status (active vs. reserve)

Three studies focused on status (active vs. reserve) as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 3). All 3 studies were conducted within the US Armed Forces. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 1902 to 3367 participants. All 3 studies identified status as a risk factor for MSkIs: 1 study only for women (when they are in the reserve instead of active duty), 1 for active personnel vs. reserve, and 1 for reserve vs. active personnel.

There is no scientific evidence for being part of the reserve (instead of active duty) as a non-modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Physiological factors

Age

Sixty-five studies focused on age as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 4). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces, 8 within the military of the UK, and 7 within the military of Finland; the other studies were conducted within the militaries of China (3 studies), Israel (2 studies), Belgium, Greece, Iran, Poland, and Switzerland (1 study for each country). The study populations ranged from 44 to 5,580,875 participants. Thirty-three of the 65 studies identified older age as a risk factor for MSkIs (however, the definitions of older age differ across studies); 30 studies did not find a significant association between age and MSkIs, while 1 study found a significant rise in MSkIs for younger participants when compared to older participants. When only studies with a population of 1400 or more participants were taken into account (this represents 31 of the 65 studies), 23 studies revealed a significant association between age and an increased risk for MSkIs compared to only 8 studies that did not find a significant association. When only studies that had 5000 participants or more were considered, the relationship was 12 (significant association) vs. 1 (no association).

Table 4.

Summary of studies that focused on age, ankle dorsiflexion, and balance as risk factors for MskI

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| Anderson [70] | 2015 | USA | Army | Light Infantry Brigade | R | 2101 | Yes |

| Anderson [71] | 2017 | USA | Army | Light Infantry | R | 4384 M, 363 F | Yes |

| Beck [140] | 2000 | USA | Marines | P | 624 M, 693 F | No | |

| Bedno [72] | 2013 | USA | Army | IET | P | 8456 M | Yes (M) |

| Cameron [44] | 2010 | USA | Multiple | Active duty | R | 423,581 | Yes |

| Canham-Chervak [141] | 2000 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 655 M, 498 F | No |

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 1156 M, 746 F | No |

| Cosio-Lima [54] | 2013 | USA | Army | Sergeants Major Academy | R | 149 | No |

| Cowan [74] | 2012 | USA | Army | Trainees | P | 1568 F | No (F) |

| Cowan [75] | 2011 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 7323 | Yes |

| Craig [40] | 2000 | USA | Army | Airborne Division | R | 242,949 aircraft exists | Yes (30 years +) |

| Davey [76] | 2015 | UK | Marines | P | 1090 M | No (M) | |

| Dixon [142] | 2019 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1065 | Yes (younger) |

| Grier [78] | 2017 | USA | Army | Infantry Brigade | R | 4236 M | Yes (M) |

| Grier [79] | 2010 | USA | Multiple | R | 24,177 M | Yes (M) | |

| Havenetidis [143] | 2011 | Greece | n/a | Recruits | P | 253 | Yes |

| Henderson [144] | 2000 | USA | Army | Combat medic | P | 439 M, 287 F | Yes |

| Hill [115] | 2013 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 83,323 | Yes |

| Knapik [47] | 2012 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes |

| Knapik [145] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1174 M, 898 F | Yes |

| Knapik [82] | 2013 | USA | Army | Army military police training | P | 1838 M, 553 F | Yes |

| Knapik [146] | 2007 | USA | Army | Mechanics | R | 518 M, 43 F | No |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Knapik [85] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 182 M, 168 F | No |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | Yes |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | Yes |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 840 M, 571 F | No |

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | Yes |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | Yes |

| Lappe [55] | 2005 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 4139 F | Yes (F) |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | Yes (F) |

| Lauder [90] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | P | 230 F | No (F) |

| Ma [147] | 2016 | China | n/a | R | 2479 | No | |

| Mahieu [148] | 2006 | Belgium | n/a | Recruits Royal Military Academy | P | 69 M | No (M) |

| Mattila [38] | 2007 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 149,750 M, 2345 F | Yes |

| Moran [149] | 2013 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 44 | No |

| Munnoch [91] | 2007 | UK | Marines | P | 1115 M | Yes (M) | |

| Nunns [150] | 2016 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 160 M | No (M) |

| Nye [151] | 2016 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 67,525 | Yes |

| Owens [152] | 2007 | USA | n/a | Active duty | R | 4451 | Yes |

| Owens [128] | 2009 | USA | Army, Marines, Navy, Air Force | Active duty | R | 19,730 | Yes |

| Parr [153] | 2015 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 106 | No |

| Pihlajamäki [93] | 2019 | Finland | n/a | Full duty | R | 4029 M | No (M) |

| Rabin [154] | 2014 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 70 M | No (M) |

| Reynolds [96] | 2009 | USA | Army | Infantry | P | 181 | No |

| Reynolds [97] | 2002 | USA | Army | Construction engineers & Combat artillery soldiers | P | 313 | No |

| Roos [99] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 651 M | No (M) |

| Roy [133] | 2012 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | P | 246 M, 17 F | No |

| Roy [121] | 2014 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 625 F | Yes (F) |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | No (M) |

| Sanchez-Santos [65] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | Yes (M) |

| Schneider [58] | 2000 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | R | 1214 | Yes |

| Sefton [137] | 2016 | USA | Army | Recruits IET | P | 1788 M | Yes (M) |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No (F) |

| Sharma [102] | 2019 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 562 M | No (M) |

| Sharma [103] | 2011 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 468 M | No (M) |

| Skeehan [139] | 2009 | USA | Army, Marine, Navy | Active duty# | R | 3367 | No |

| Sobhani [155] | 2015 | Iran | n/a | Recruits | R | 181 M | No (M) |

| Sormaala [39] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | R | 118,149 | No |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | Yes (M) |

| Trybulec [156] | 2016 | Poland | Army | Airborne Brigade | R | 162 M, 3 F | Yes |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | No (M) |

| Waterman [31] | 2016 | USA | Multiple | Active Duty | R | 5,580,875 | Yes |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | Yes |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | No (M) |

| Ankle dorsiflexion (limited) | |||||||

| Dixon [30] | 2006 | UK | Marines | Recruits | R | 20 | No |

| Rabin [154] | 2014 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 70 M | No (M) |

| Balance (low) | |||||||

| Heebner [157] | 2017 | USA | Army | Special Operation Forces | P | 95 | No |

| Sell [158] | 2014 | USA | Special Operation Forces | P | 226 | Yes |

BCT basis combat training; IET initial entry training; n/a not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI); #Deployment

There is moderate scientific evidence for age as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Ankle dorsiflexion (limited)

Only 2 studies focused on limited ankle dorsiflexion as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 4). One study was conducted within the IDF, and one in the armed forces of the UK. The sizes of the study populations were 20 and 70 participants, respectively. In both studies, limited ankle dorsiflexion was not significantly identified as a risk factor for MSkIs.

There is no scientific evidence for limited ankle dorsiflexion as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Balance (low)

Two studies focused on low balance as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 4). These studies were conducted within the special operations forces of the US military. In the larger study, poor balance (measured as single-leg balance with the eyes open, and the eyes closed on a force plate) was identified as a risk factor for MSkIs, whereas in the other studies, no association was identified.

There is weak scientific evidence for low balance as a modifiable risk factor.

BMI: in general

Fifty-two studies focused on BMI (in general) as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 5). BMI in general means that the studies have looked at BMI without categorization (such as obese, overweight, underweight categories). This makes it very difficult to compare different study outcomes. Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (24 studies); 9 studies within the military of the UK, 6 within the Finnish armed forces, and 5 within the IDF. The remaining studies were conducted in the militaries of Switzerland (3 studies), Greece (2 studies), Australia, Belgium, and Malta (1 study each). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 44 to 238,772 participants. Fourteen of the 52 studies identified BMI as a risk factor for MSkIs. Thirteen studies found that higher BMI was a risk factor; 1 study found that lower BMI was a risk factor. Thirty-five studies did not find a significant association between BMI and MSkIs, and 3 studies found that BMI is a risk factor for men, but not for women.

Table 5.

Summary of studies that focused on BMI (in general), obesity, being overweight, and being underweight as risk factors for MskIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (in general) | |||||||

| Allsopp [159] | 2003 | UK | Navy | Recruits | R | 1287 M, 354 F | Yes |

| Beck [140] | 2000 | USA | Marines | P | 624 M, 693 F | Yes (M), no (F) | |

| Bedno [35] | 2019 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 238,772 | Yes (M), no (F) |

| Billings [160] | 2004 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 2006 | Yes |

| Blacker [161] | 2008 | UK | Army | Recruits | R | 11,937 M, 1480 F | Yes |

| Burgi [126] | 2011 | USA | Navy | Recruits | P | 2300 F | No (F) |

| Cosio-Lima [54] | 2013 | USA | Army | Sergeants Major Academy | R | 149 | No |

| Davey [76] | 2015 | UK | Marines | P | 1090 M | No (M) | |

| Garnock [113] | 2018 | Australia | Navy | Recruits | P | 95 M, 39 F | No |

| George [114] | 2012 | USA | Army | Combat medics | P | 1230 | Yes |

| Havenetidis [162] | 2017 | Greece | Army | Officer recruits | P | 268 M | No (M) |

| Havenetidis [143] | 2011 | Greece | n/a | Recruits | P | 253 | No |

| Jones [34] | 2017 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 143,398 M, 41,727 F | Yes |

| Knapik [145] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1174 M, 898 F | No |

| Knapik [82] | 2013 | USA | Army | Army military police training | P | 1838 M, 553 F | Yes |

| Knapik [146] | 2007 | USA | Army | Mechanics | R | 518 M, 43 F | Yes (M) |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Knapik [85] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 182 M, 168 F | No |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | No |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | No |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 840 M, 571 F | No |

| Kodesh [163] | 2015 | Israel | n/a | Combat Fitness Instructor Course | P | 158 F | No |

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | Yes |

| Kupferer [164] | 2014 | USA | Air Force | Trainees | R | 141 | No |

| Lauder [90] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | P | 230 F | Yes (F) |

| Mahieu [148] | 2006 | Belgium | n/a | Recruits Royal Military Academy | P | 69 M | No |

| Mattila [38] | 2007 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 149,750 M, 2345 F | No |

| Moran [149] | 2013 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 44 | No |

| Moran [63] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Elite combat unit BCT | P | 74 | No (M) |

| Moran [125] | 2008 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 227 F | Yes (F) |

| Munnoch [91] | 2007 | UK | Marines | P | 1115 M | No (M) | |

| Nunns [150] | 2016 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 160 M | Yes (M) |

| Nye [151] | 2016 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 67,525 | No |

| Parr [153] | 2015 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 106 | No |

| Pihlajamäki [93] | 2019 | Finland | n/a | Full duty | R | 4029 M | No (M) |

| Psaila [94] | 2017 | Malta | n/a | Recruits BCT | P | 114 M, 13 F | No |

| Rabin [154] | 2014 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 70 M | No (M) |

| Rappole [95] | 2017 | USA | Army | Army Brigade | R | 1099 | Yes |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | No |

| Rice [120] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 147 M | Yes (M, especially lower BMI) |

| Roos [99] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 651 M | No (M) |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | No (M) |

| Scott [122] | 2015 | USA | Army | Reserve Officer Training | R | 165 M, 30 F | No |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No (F) |

| Sharma [102] | 2019 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 562 M | No (M) |

| Sharma [103] | 2011 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 468 M | No (M) |

| Sillanpää [51] | 2008 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | R | 128,508 M | No (M) |

| Sormaala [39] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | R | 118,149 | No |

| Waterman [165] | 2010 | USA | Military Academy | R | 10,511 person years | Yes (M), no (F) | |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Wunderlin [107] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 230 M | Yes (M) |

| Wyss [68] | 2014 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1676 | NO |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | |||||||

| Anderson [70] | 2015 | USA | Army | Light Infantry Brigade | R | 2101 | Yes |

| AMSA [43] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 387,536 | Yes |

| Bedno [72] | 2013 | USA | Army | IET | P | 8456 M | Yes (M) |

| Billings [160] | 2004 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 2006 | Yes |

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 1156 M, 746 F | Yes |

| Cowan [74] | 2012 | USA | Army | Trainees | P | 1568 F | No (F) |

| Cowan [75] | 2011 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 7323 | Yes |

| Gundlach [166] | 2012 | Germany | Army | Active duty | P | 410 | Yes |

| Henderson [144] | 2000 | USA | Army | Combat medic | P | 439 M, 287 F | Yes |

| Hruby [48] | 2016 | USA | Army | R | 736,608 | Yes | |

| Jones [34] | 2017 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 143,398 M, 41,727 F | Yes |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | Yes |

| Ma [147] | 2016 | China | n/a | R | 2479 | Yes | |

| Packnett [41] | 2011 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 217,468 M, 47,813 F | Yes |

| Rappole [95] | 2017 | USA | Army | Army Brigade | R | 1099 | Yes |

| Taanila [123] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 944 M | Yes (M) |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | Yes (M) |

| Overweight (BMI ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2) | |||||||

| Anderson [70] | 2015 | USA | Army | Light Infantry Brigade | R | 2101 | Yes |

| Bedno [72] | 2013 | USA | Army | IET | P | 8456 M | No (M) |

| Billings [160] | 2004 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 2006 | Yes |

| Canham-Chervak [52] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1156 M, 746 F | Yes |

| Cowan [74] | 2012 | USA | Army | Trainees | P | 1568 F | No (F) |

| Grier [78] | 2017 | USA | Army | Infantry Brigade | R | 4236 M | Yes (M) |

| Gundlach [166] | 2012 | Germany | Army | Active duty | P | 410 | Yes |

| Henderson [144] | 2000 | USA | Army | Combat medic | P | 439 M, 287 F | Yes |

| Hruby [48] | 2016 | USA | Army | R | 736,608 | Yes | |

| Knapik [47] | 2012 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes (M), no (F) |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | No |

| Ma [147] | 2016 | China | n/a | R | 2479 | Yes | |

| Mattila [37] | 2007 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | R | 133,943 M, 2044 F | Yes |

| Rappole [95] | 2017 | USA | Army | Army Brigade | R | 1099 M | Yes (M) |

| Taanila [123] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 944 M | Yes (M) |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | No (M) |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | |||||||

| AMSA [43] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | R | 387,536 | Yes |

| Bedno [72] | 2013 | USA | Army | IET | P | 8456 M | Yes (M) |

| Billings [160] | 2004 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | R | 2006 | Yes |

| Cowan [74] | 2012 | USA | Army | Trainees | P | 1568 F | No (F) |

| Finestone [167] | 2008 | Israel | Army | Light Infantry training | P | 36 M, 99 F | Yes |

| Grier [78] | 2017 | USA | Army | Infantry brigade | R | 4236 M | Yes (M) |

| Hruby [48] | 2016 | USA | Army | R | 736,608 | Yes | |

| Jones [34] | 2017 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 143,398 M, 41,727 F | Yes |

| Knapik [47] | 2012 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | No |

| Packnett [41] | 2011 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 217,468 M, 47,813 F | Yes |

| Reynolds [96] | 2009 | USA | Army | Infantry | P | 181 | Yes |

| Taanila [104] | 2015 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 1411 M | Yes (M) |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | No (M) |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | Yes (M) |

BMI body mass index; BCT basis combat training; IET initial entry training; n/a not available; R Retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI)

There is insufficient scientific evidence for BMI in general as a modifiable risk factor.

BMI: obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)

Seventeen studies focused on obesity as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 5). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (12 studies). Additional studies were conducted within the militaries of Finland (3 studies), China, and Germany (1 study for each country). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 410 to 387,536 participants. Sixteen studies identified obesity as a risk factor for MSkIs; only one study, with 1568 participants, did not find a significant association.

There is strong scientific evidence for obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

BMI: overweight (BMI ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2)

Sixteen studies focused on being overweight as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 5). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (10 studies); the remaining studies were conducted within the Finnish armed forces (4 studies) and within the militaries of China and Germany (1 study each). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 410 to 736,608 participants. Eleven studies identified being overweight as a risk factor for MSkIs; 4 studies did not find a significant association. One study found an association for men but not for women. It is important to acknowledge that these findings are based on BMI alone; none of the 16 studies analyzed the body composition of the included soldiers in detail (i.e., body fat or muscle mass).

There is strong scientific evidence for being overweight (BMI ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2) as a modifiable risk factor for MSkI.

BMI: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2)

Fifteen studies focused on being underweight as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 5). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (10 studies); the remaining studies were conducted within the militaries of Finland (3 studies), China, and Israel (1 study each). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 135 to 736,608 participants. Twelve studies identified being underweight as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 3 studies did not find a significant association.

There is strong scientific evidence for being underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Body fat (higher)

Eight studies focused on body fat as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 6). The research was conducted within the armies of Greece (2 studies), Iran (1 study), Israel (2 studies), and the US (3 studies); the studies included different methods for measuring body fat (e.g., self-report, circumference, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, 4-site skinfold test). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 44 to 583,651 participants. Six of the 8 studies identified a higher percentage of body fat as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 2 studies did not find a significant association. A retrospective study by Knapik et al. [46], with more than a half million participants, showed a relationship between a greater percentage of body fat and a higher risk for MSkIs.

Table 6.

Summary of studies that focused on body fat, body height, and body weight as risk factors for MskIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body fat (higher) | |||||||

| Anderson [71] | 2017 | USA | Army | Light Infantry | R | 4384 M, 363 F | Yes |

| Havenetidis [162] | 2017 | Greece | Army | Officer recruits | P | 268 M | Yes (M) |

| Havenetidis [143] | 2011 | Greece | n/a | Recruits | P | 253 | Yes |

| Knapik [46] | 2018 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes |

| Kodesh [163] | 2015 | Israel | n/a | Combat Fitness Instructor Course | P | 158 F | Yes (F) |

| Krauss [168] | 2017 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 1900 F | Yes (F) |

| Moran [149] | 2013 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 44 | No |

| Sobhani [155] | 2015 | Iran | n/a | Recruits | R | 181 M | No (M) |

| Body height (higher) | |||||||

| Beck [140] | 2000 | USA | Marines | P | 624 M, 693 F | Yes (M), no (F) | |

| Blacker [161] | 2008 | UK | Army | Recruits | R | 11,937 M, 1480 F | No |

| Cosio-Lima [54] | 2013 | USA | Army | Sergeants Major Academy | R | 149 | No |

| Davey [76] | 2015 | UK | Marines | P | 1090 M | No (M) | |

| Fallowfield [77] | 2018 | UK | Air Force | Recruits | P | 990 M, 203 F | Yes |

| Finestone [112] | 2011 | Israel | Army | Elite infantry soldier | P | 77 M | No (M) |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | No (M) | |

| Kelly [80] | 2000 | USA | Navy | Recruits BCT | R | 86 F | Yes (F) |

| Knapik [47] | 2012 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes |

| Knapik [145] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1174 M, 898 F | No |

| Knapik [146] | 2007 | USA | Army | Mechanics | R | 518 M, 43 F | No |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | No |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | No |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 840 M, 571 F | No |

| Kodesh [163] | 2015 | Israel | n/a | Combat Fitness Instructor Course | P | 158 F | No |

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | Yes |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | No |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | No (F) |

| Ma [147] | 2016 | China | n/a | R | 2479 | No | |

| Mahieu [148] | 2006 | Belgium | n/a | Recruits Royal Military Academy | P | 69 M | No (M) |

| Mattila [38] | 2007 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 149,750 M, 2345 F | No |

| Monnier [119] | 2019 | Sweden | Marines | Training course | P | 48 M, 5 F | Yes |

| Moran [149] | 2013 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 44 | No |

| Moran [63] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Elite combat unit BCT | P | 74 | No |

| Moran [125] | 2008 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 227 F | Yes (F) |

| Munnoch [91] | 2007 | UK | Marines | P | 1115 M | No (M) | |

| Nunns [150] | 2016 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 160 M | No (M) |

| Parr [153] | 2015 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 106 | No |

| Reynolds [96] | 2009 | USA | Army | Infantry | P | 181 | No |

| Reynolds [97] | 2002 | USA | Army | Construction engineers & Combat artillery soldiers | P | 313 | Yes (to be shorter) |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | No |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | No (M) |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No (F) |

| Sharma [102] | 2019 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 562 M | No (M) |

| Sharma [103] | 2011 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 468 M | No (M) |

| Sillanpää [51] | 2008 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | R | 128,508 M | Yes (M) |

| Sobhani [155] | 2015 | Iran | n/a | Recruits | R | 181 M | No (M) |

| Sormaala [39] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | R | 118,149 | No |

| Sulsky [42] | 2018 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 278,045 M, 55,302 F | Yes |

| Taanila [59] | 2012 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 982 M | No (M) |

| Trybulec [156] | 2016 | Poland | Army | Airborne Brigade | R | 162 M, 3 F | No |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | No (M) |

| Waterman [165] | 2010 | USA | Military Academy | R | 10,511 person years | Yes | |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | No (M) |

| Body weight (higher) | |||||||

| Beck [140] | 2000 | USA | Marines | P | 624 M, 693 F | Yes (M), no (F) | |

| Blacker [161] | 2008 | UK | Army | Recruits | R | 11,937 M, 1480 F | No |

| Davey [76] | 2015 | UK | Marines | P | 1090 M | No (M) | |

| Davey [127] | 2016 | UK | Marines | P | 1082 M | No (M) | |

| Finestone [112] | 2011 | Israel | Army | Elite infantry soldier | P | 77 M | No (M) |

| Givon [61] | 2000 | Israel | n/a | P | 2306 M | Yes (M) | |

| Havenetidis [162] | 2017 | Greece | Army | Officer recruits | P | 268 M | Yes (M) |

| Hughes [169] | 2008 | Australia | Special Operation Forces | Active duty | R | 554 descents | Yes |

| Kelly [80] | 2000 | USA | Navy | Recruits BCT | R | 86 F | Yes (F) |

| Knapik [47] | 2012 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | R | 475,745 M, 107,906 F | Yes (invers) |

| Knapik [145] | 2006 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 1174 M, 898 F | No |

| Knapik [146] | 2007 | USA | Army | Mechanics | R | 518 M, 43 F | Yes |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Knapik [86] | 2008 | USA | Army | Paratrooper training | R | 1677 | Yes |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 2147 M, 920 F | No |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 840 M, 571 F | No (M), yes (F) |

| Kodesh [163] | 2015 | Israel | n/a | Combat Fitness Instructor Course | P | 158 F | No (F) |

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | Yes |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | Yes (F) |

| Ma [147] | 2016 | China | n/a | R | 2479 | No | |

| Mahieu [148] | 2006 | Belgium | n/a | Recruits Royal Military Academy | P | 69 M | No (M) |

| Moran [149] | 2013 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 44 | No |

| Moran [63] | 2012 | Israel | Army | Elite combat unit BCT | P | 74 | No |

| Monnier [119] | 2019 | Sweden | Marines | Training course | P | 48 M, 5 F | No |

| Munnoch [91] | 2007 | UK | Marines | P | 1115 M | No (M) | |

| Nunns [150] | 2016 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 160 M | No (M) |

| Parr [153] | 2015 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 106 | No |

| Reynolds [96] | 2009 | USA | Army | Infantry | P | 181 | No |

| Reynolds [97] | 2002 | USA | Army | Construction engineers & Combat artillery soldiers | P | 313 | Yes |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | No |

| Rice [120] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 147 M | Yes (M) (invers) |

| Robinson [57] | 2016 | UK | Army | Recruits | P | 1810 | Yes |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | No (M) |

| Sanchez-Santos [65] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 1082 M | Yes (M) (invers) |

| Schermann [129] | 2018 | Israel | Army | Infantry unit vs. female unit working with dogs | R | 7949 | Yes |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No (F) |

| Sharma [102] | 2019 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 562 M | No (M) |

| Sharma [103] | 2011 | UK | Army | Infantry recruits | P | 468 M | No (M) |

| Sillanpää [51] | 2008 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | R | 128,508 M | Yes (M) |

| Sobhani [155] | 2015 | Iran | n/a | Recruits | R | 181 M | No (M) |

| Sormaala [39] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | R | 118,149 | No |

| Trybulec [156] | 2016 | Poland | Army | Airborne Brigade | R | 162 M, 3 F | No |

| Waterman [165] | 2010 | USA | Military Academy | R | 10,511 person years | Yes | |

| Wilkinson [60] | 2009 | UK | Army | Infantry | P | 660 | No |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | No (M) |

BCT basis combat training; n/a not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI)

There is strong scientific evidence for higher body fat as a modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Body height (higher)

Forty-six studies focused on body height as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 6). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (18 studies); 8 within the military of the UK, 7 within the military of Finland, and 6 studies within the IDF; the other studies were conducted within the military of China (3 studies), Belgium, Iran, Poland, and Sweden (1 study each). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 44 to 583,651 participants. Eight of the 46 studies identified a taller stature as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 35 studies did not find a significant association. One study found a significant increase in MSkIs associated with a taller stature for men but not for women, and one study found that a shorter stature was a significant risk factor for MSkIs.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for body height as a non-modifiable risk factor for MSkIs.

Body weight (higher)

Forty-five studies focused on body weight as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 6). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (16 studies); 11 studies within the military of the UK, and 6 within the IDF. The remaining studies were conducted within the militaries of Finland (4 studies), China (2 studies), Australia, Belgium, Greece, Iran, Poland, and Sweden (1 study each). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 44 to 583,651 participants. Thirteen of the 45 studies identified a higher body weight as a risk factor for MSkIs, 27 did not find a significant association between body weight and MSkIs, and 3 studies found a significant increase in MSkIs for a lower body weight. Two studies found different outcomes regarding the participants’ sex.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for higher body weight as a modifiable risk factor.

Bone (mineral) density (low)

Three studies focused on low bone (mineral) density as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 7). All 3 studies were conducted in the US Army. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 230 to 891 participants. Two studies identified low bone (mineral) density as a risk factor for MSkIs; one study did not find a significant association.

Table 7.

Summary of studies that focused on bone (mineral) density, external rotation of the hip, flexibility, and foot type as risk factors for MskIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone (mineral) density (low) | |||||||

| Cosman [64] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 755 M, 136 F | Yes |

| Knapik [85] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 182 M, 168 F | No |

| Lauder[90] | 2000 | USA | Army | Active duty | P | 230 F | Yes (F) |

| External rotation of the hip (higher) | |||||||

| Burne [170] | 2004 | Australia | Military Academy | P | 122 M, 25 F | No | |

| Finestone [112] | 2011 | Israel | Army | Elite infantry soldier | P | 77 M | No (M) |

| Garnock [113] | 2018 | Australia | Navy | Recruits | P | 95 M, 39 F | Yes |

| Rauh [171] | 2010 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 748 F | Yes (F) |

| Sobhani [155] | 2015 | Iran | n/a | Recruits | R | 181 M | Yes (M) |

| Flexibility (lower) | |||||||

| Heebner [157] | 2017 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 95 | No |

| Keenan [172] | 2017 | USA | Multiple | Special Forces | P | 726 | Yes#,## |

| Knapik [85] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits | P | 182 M, 168 F | No# |

| Nagai [92] | 2017 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | P | 275 | No### |

| Wang [106] | 2003 | China | n/a | Military Police Forces Training | R | 805 M | No (M) |

| Foot type | |||||||

| Esterman [173] | 2005 | Australia | Air Force | Recruits | P | 230 | No |

| Hetsroni [174] | 2006 | Israel | Army | Recruits | P | 405 M | No& |

| Levy [175] | 2006 | USA | n/a | Military Academy Cadets | R | 431 M, 73 F | Yes&& |

| Nunns [150] | 2016 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 160 M | Yes (M)&&&,&&&& |

| Psaila [94] | 2017 | Malta | n/a | Recruits BCT | P | 114 M, 13 F | No |

| Reynolds [98] | 2000 | USA | Marines | Winter mountain training | P | 356 | Yes&&&&& |

| Rice [120] | 2017 | UK | Marines | Recruits | P | 147 M | Yes (M)&&& |

| Yates [176] | 2004 | UK | Navy | Recruits | P | 84 M, 40 F | Yes |

BCT basis combat training; n/a not available; R retrospective study; P prospective study; M male; F female; (M) risk factor only for males; (F) risk factor only for females

*Risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries (MSkI); #Hamstring-flexibility; ##Gastrocnemius-soleus flexibility; ###Several muscle groups (shoulder, trunk rotation, hip extension, active knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion, ankle plantarflexion); &For any type for foot pronation; &&Pes planus; &&&Width malleolar; &&&&Arch index, corrected calf girth; &&&&&Forefoot varus

There is insufficient scientific evidence for low bone (mineral) density as a non-modifiable risk factor.

External rotation of the hip (higher)

Five studies focused on external rotation (range of motion) of the hip as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 7). The research was conducted within the militaries of Australia (2 studies), Iran, Israel, and the US (each 1 study). The range of motion of the hip was measured in different ways across the identified studies. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 77 to 748 participants. Three studies (including the two with the most participants) identified that higher external rotation of the hip is a risk factor for MSkIs; two studies did not find a significant association.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for higher external rotation of the hip as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Flexibility (lower)

Five studies focused on flexibility at different anatomical locations as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 7). Most of the research was conducted within different branches of the US Armed Forces (4 studies), and 1 study was conducted by armed forces from China. The sizes of the study populations ranged from 95 to 805 participants. Only 1 study identified low flexibility as a risk factor for MSkIs, and 5 studies did not find a significant association.

There is insufficient scientific evidence for lower flexibility as a modifiable risk factor.

Foot type

Eight studies focused on foot type (e.g., anatomic differences such as a pes planus, a wide malleolar or a forefoot varus) as a risk factor for MSkIs (Table 7). The studies were conducted within the militaries of the UK (3 studies), USA (2 studies), Australia, Israel, and Malta (1 study from each country). The sizes of the study populations ranged from 124 to 504 participants. Five studies identified different foot types as a risk factor for MSkI, while 3 studies did not.

There is moderate scientific evidence for different foot types as a non-modifiable risk factor.

Genetic factors

Two studies focused on genetic factors as risk factors for MSkIs (Table 8). One study was conducted within the military of China and 1 within the military of Finland. The study populations ranged from 192 to 1398 participants. Both studies identified an association between certain genetic factors and an increased risk for MSkIs. The analyzed genetic factors were different between the 2 studies, so a comparison was not possible. Korvala et al. [89] examined genes involved in bone metabolism and pathology, and Zhao et al. [108] looked at a specific growth differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) polymorphism between recruits with and without stress fractures.

Table 8.

Summary of studies that focused on genetic factors, late menarche, muscular strength, and physical fitness as risk factors for MSkIs

| Study | Publication year | Country | Branches | Unit/training | Study type | n | Risk factor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic factors | |||||||

| Korvala [89] | 2010 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | P | 192 | Yes |

| Zhao [108] | 2016 | China | Army | Recruits | P | 1398 M | Yes (M) |

| Late menarche | |||||||

| Cosman [64] | 2013 | USA | Army | Military Academy | P | 136 F | Yes |

| Knapik [81] | 2010 | USA | Air Force | Recruits BCT | P | 375 F | No |

| Knapik [87] | 2008 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 920 F | No |

| Knapik [88] | 2009 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | P | 571 F | No |

| Lappe [56] | 2001 | USA | Army | Recruits BCT | P | 3758 F | No |

| Shaffer [109] | 2006 | USA | Marines | Recruits BCT | R | 2962 F | No |

| Trone [105] | 2014 | USA | Marine Corp Air Force Army | Recruits BCT | R | 597 F | Yes |

| Muscular strength (lower) | |||||||

| Blacker [161] | 2008 | UK | Army | Recruits | R | 11,937 M, 1480 F | No |

| Heebner [157] | 2017 | USA | Army | Special Operation Forces | P | 95 | Yes |

| Knapik [84] | 2007 | USA | Army | Band | R | 159 M, 46 F | No |

| Kuikka [36] | 2013 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | R | 128,584 | Yes |

| Mattila [38] | 2007 | Finland | Army | Conscripts | P | 149,750 M, 2345 F | Yes |

| Nagai [92] | 2017 | USA | Army | Airborne Div | P | 275 | No |

| Parr [153] | 2015 | USA | Army | Special Operations Forces | P | 106 | No## |

| Roy [177] | 2012 | USA | Army | Brigade Combat Team# | R | 593 | Yes |

| Ruohola [100] | 2006 | Finland | n/a | Recruits | P | 756 M | Yes (M) |

| Sillanpää [51] | 2008 | Finland | n/a | Conscripts | R | 128,508 M | No (M) |

| Wunderlin [107] | 2015 | Switzerland | Army | Recruits | P | 230 M | Yes (M) |

| Physical fitness (low) | |||||||

| Allsopp [159] | 2003 | UK | Navy | Recruits | R | 1287 M, 354 F | Yes |

| Anderson [70] | 2015 | USA | Army | Light Infantry Brigade | R | 2101 | Yes |

| Anderson [71] | 2017 | USA | Army | Light Infantry | R | 4384 M, 363 F | Yes |

| Beck [140] | 2000 | USA | Marines | P | 624 M, 693 F | Yes | |