Abstract

Background

Midwives are primary providers of care for childbearing women around the world. However, there is a lack of synthesised information to establish whether there are differences in morbidity and mortality, effectiveness and psychosocial outcomes between midwife‐led continuity models and other models of care.

Objectives

To compare midwife‐led continuity models of care with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (25 January 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished trials in which pregnant women are randomly allocated to midwife‐led continuity models of care or other models of care during pregnancy and birth.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 15 trials involving 17,674 women. We assessed the quality of the trial evidence for all primary outcomes (i.e. regional analgesia (epidural/spinal), caesarean birth, instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum), spontaneous vaginal birth, intact perineum, preterm birth (less than 37 weeks) and all fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death using the GRADE methodology: all primary outcomes were graded as of high quality.

For the primary outcomes, women who had midwife‐led continuity models of care were less likely to experience regional analgesia (average risk ratio (RR) 0.85, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.92; participants = 17,674; studies = 14; high quality), instrumental vaginal birth (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97; participants = 17,501; studies = 13; high quality), preterm birth less than 37 weeks (average RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91; participants = 13,238; studies = eight; high quality) and less all fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death (average RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.99; participants = 17,561; studies = 13; high quality evidence). Women who had midwife‐led continuity models of care were more likely to experience spontaneous vaginal birth (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.07; participants = 16,687; studies = 12; high quality). There were no differences between groups for caesarean births or intact perineum.

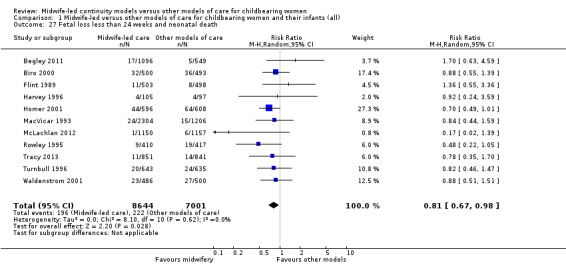

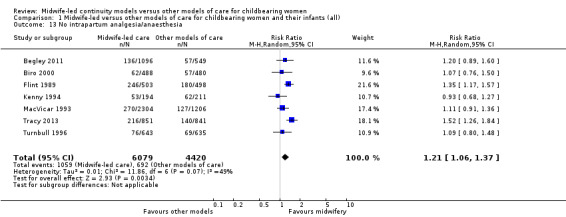

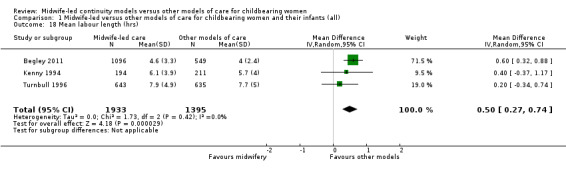

For the secondary outcomes, women who had midwife‐led continuity models of care were less likely to experience amniotomy (average RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.98; participants = 3253; studies = four), episiotomy (average RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92; participants = 17,674; studies = 14) and fetal loss less than 24 weeks and neonatal death (average RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.98; participants = 15,645; studies = 11). Women who had midwife‐led continuity models of care were more likely to experience no intrapartum analgesia/anaesthesia (average RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.37; participants = 10,499; studies = seven), have a longer mean length of labour (hours) (mean difference (MD) 0.50, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.74; participants = 3328; studies = three) and more likely to be attended at birth by a known midwife (average RR 7.04, 95% CI 4.48 to 11.08; participants = 6917; studies = seven). There were no differences between groups for fetal loss equal to/after 24 weeks and neonatal death, induction of labour, antenatal hospitalisation, antepartum haemorrhage, augmentation/artificial oxytocin during labour, opiate analgesia, perineal laceration requiring suturing, postpartum haemorrhage, breastfeeding initiation, low birthweight infant, five‐minute Apgar score less than or equal to seven, neonatal convulsions, admission of infant to special care or neonatal intensive care unit(s) or in mean length of neonatal hospital stay (days).

Due to a lack of consistency in measuring women's satisfaction and assessing the cost of various maternity models, these outcomes were reported narratively. The majority of included studies reported a higher rate of maternal satisfaction in midwife‐led continuity models of care. Similarly, there was a trend towards a cost‐saving effect for midwife‐led continuity care compared to other care models.

Authors' conclusions

This review suggests that women who received midwife‐led continuity models of care were less likely to experience intervention and more likely to be satisfied with their care with at least comparable adverse outcomes for women or their infants than women who received other models of care.

Further research is needed to explore findings of fewer preterm births and fewer fetal deaths less than 24 weeks, and all fetal loss/neonatal death associated with midwife‐led continuity models of care.

Plain language summary

Midwife‐led continuity models of care compared with other models of care for women during pregnancy, birth and early parenting

What is the issue?

There are several ways to look after the health and well‐being of women and babies during pregnancy, birth and afterwards – these ways are called ‘models of care’. Sometimes, an obstetrician or another doctor is the lead healthcare professional and at other times it is a midwife. Sometimes, the responsibility is shared between obstetricians and midwives. One of the models is called ‘the midwife‐led continuity model’. This is where the midwife is the lead professional starting from the initial booking appointment, up to and including the early days of parenting. We wanted to find out if women and babies do better with this midwife‐led continuity model, compared with other models.

Why is this important?

Midwife‐led continuity models provide care from the same midwife or team of midwives during the pregnancy, birth and the early parenting period, and many women value this. These midwives also involve other care‐providers if they are needed. Obstetrician‐led or family doctor‐led models are not usually able to provide the same midwife/wives throughout. We need to know if the midwife‐led continuity model is safe, and if it brings benefits to mothers and babies.

What evidence did we find?

We identified 15 studies involving 17,674 mothers and babies (search date 25 January 2016). We included women at low risk of complications as well as women at increased risk, but not currently experiencing problems. All the trials involved professionally‐qualified midwives and no trial included models of care that offered home birth. We used reliable methods to assess the quality of the evidence and looked at seven key outcomes: preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks of pregnancy); the risk of losing the baby in pregnancy or in the first month after birth; spontaneous vaginal birth (when labour was not induced and birth not assisted by forceps; caesarean birth; instrumental vaginal birth (births using forceps or ventouse); whether the perineum remained intact, and use of regional analgesia (such as epidural).

The main benefits were that women who received midwife‐led continuity of care were less likely to have an epidural. In addition, fewer women had episiotomies or instrumental births. Women’s chances of a spontaneous vaginal birth were also increased and there was no difference in the number of caesarean births. Women were less likely to experience preterm birth, and they were also at a lower risk of losing their babies. In addition, women were more likely to be cared for in labour by midwives they already knew. The review identified no adverse effects compared with other models.

The trials contributed enough high quality evidence for each key outcome to give us reliable results for each one. We can be reasonably confident that future trials would find similar results for these outcomes.

What does this mean?

Most women should be offered ‘midwife‐led continuity of care’. It provides benefits for women and babies and we have identified no adverse effects. However, we cannot assume the same applies to women with existing serious pregnancy or health complications, because these women were not included in the evidence assessed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Midwife‐led compared with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) for childbearing women.

| Midwife‐led compared with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) for childbearing women | ||||||

| Patient or population: Pregnant women Settings: Australia, Canada, Ireleand, UK Intervention: Midwife‐led models of care Comparison: All other models of care for childbearing women and their infants | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) | Midwife‐led | |||||

| Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks) | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.64 to 0.91) | 13238 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | None of the included trials in this review had adequate blinding. We have not downgraded evidence (‐1) for risk of bias due to lack of blinding. | |

| 63 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (41 to 58) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 59 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (38 to 54) | |||||

| All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death | Study population | RR 0.84 (0.71 to 0.99) | 17561 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ||

| 34 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (24 to 34) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (14 to 20) | |||||

| Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors) | Study population | RR 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | 16687 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 658 per 1000 | 691 per 1000 (677 to 704) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 693 per 1000 | 727 per 1000 (713 to 741) | |||||

| Caesarean birth | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) | 17674 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 155 per 1000 | 143 per 1000 (130 to 155) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 156 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (131 to 156) | |||||

| Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum) | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.83 to 0.97) | 17501 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 143 per 1000 | 129 per 1000 (119 to 139) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 179 per 1000 | 161 per 1000 (149 to 174) | |||||

| Intact perineum | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | 13186 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 1 | ||

| 269 per 1000 | 279 per 1000 (255 to 304) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 333 per 1000 | 346 per 1000 (316 to 376) | |||||

| Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal) | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.78 to 0.92) | 17674 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 2 | ||

| 270 per 1000 | 229 per 1000 (211 to 248) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 287 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (224 to 264) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Statistical heterogeneity, I² = 54%. We did not downgrade the evidence for heterogeneity with I2 < 60%.

2Statistical heterogeneity, I² = 57%.

Background

Description of the condition

In many parts of the world, midwives are the primary providers of care for childbearing women (ten Hoope‐Bender 2014). There are, however, considerable variations in the organisation of midwifery services and in the education and role of midwives (UNFPA 2014). Furthermore, in some countries, e.g. in North America, medical doctors are the primary care providers for the vast majority of childbearing women, while in other countries, e.g. Australia, New Zealand, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Ireland, various combinations of midwife‐led continuity, medical‐led, and shared models of care are available. Childbearing women are often faced with different opinions as to which option might be best for them (De Vries 2001). There is much debate about the clinical and cost effectiveness of the different models of maternity care (Ryan 2013) and hence continuing debate on the optimal model of care for routine ante‐, intra‐ and postnatal care for healthy pregnant women (Sutcliffe 2012; Walsh 2012). This review complements other work on models of maternity care and attributes thereof, specifically, the work of Hodnett (Hodnett 2012) and Olsen (Olsen 2012), in which the relationships between the various birth settings and pregnancy outcomes were evaluated systematically. This review also subsumes the Cochrane review, 'Continuity of caregivers during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period' (Hodnett 2000).

Description of the intervention

Whilst it is difficult to categorise maternity models of care exclusively due to the influence of generic policies and guidelines, it is assumed that the underpinning philosophy of a midwife‐led model of care is normality and the natural ability of women to experience birth without routine intervention. The midwife‐led continuity model of care is based on the premise that pregnancy and birth are normal life events. The midwife‐led continuity model of care includes: continuity of care; monitoring the physical, psychological, spiritual and social well being of the woman and family throughout the childbearing cycle; providing the woman with individualised education, counselling and antenatal care; attendance during labour, birth and the immediate postpartum period by a known midwife; ongoing support during the postnatal period; minimising unnecessary technological interventions; and identifying, referring and co‐ordinating care for women who require obstetric or other specialist attention. Differences between midwife‐led continuity and other models of care often include variations in philosophy, relationship between the care provider and the pregnant woman, use of interventions during labour, care setting (home, home‐from‐home or acute setting) and in the goals and objectives of care (Rooks 1999).

Midwife‐led continuity models of care

Midwife‐led continuity of care has been defined as care where "the midwife is the lead professional in the planning, organisation and delivery of care given to a woman from initial booking to the postnatal period" (RCOG 2001). Some antenatal and/or intrapartum and/or postpartum care may be provided in consultation with medical staff as appropriate. Within these models, midwives are, however, in partnership with the woman, the lead professional with responsibility for assessment of her needs, planning her care, referral to other professionals as appropriate, and for ensuring provision of maternity services. Thus, midwife‐led continuity models of care aim to provide care in either community or hospital settings, normally to healthy women with uncomplicated or 'low‐risk' pregnancies. In some models, midwives provide continuity of midwifery care to all women from a defined geographical location, acting as lead professional for women whose pregnancy and birth is uncomplicated, and continuing to provide midwifery care to women who experience medical and obstetric complications in partnership with other professionals.

Some models of midwife‐led continuity of care provide continuity of care to a defined group of women through a team of midwives sharing a caseload, often called 'team' midwifery. Thus, a woman will receive her care from a number of midwives in the team, the size of which can vary. Other models, often termed 'caseload midwifery', aim to offer greater relationship continuity, by ensuring that childbearing women receive their ante‐, intra‐ and postnatal care from one midwife or her/his practice partner (McCourt 2006). There is continuing debate about the risks, benefits, and costs of team and caseload models of midwife‐led continuity of care (Ashcroft 2003; Benjamin 2001; Green 2000; Johnson 2005; Waldenstrom 1998).

Other models of care

Other models of care include the following (a) Obstetrician‐provided care. This is common in North America, where obstetricians are the primary providers of antenatal care for most childbearing women. An obstetrician (not necessarily the one who provides antenatal care) is present for the birth, and nurses provide intrapartum and postnatal care. (b) Family doctor‐provided care, with referral to specialist obstetric care as needed. Obstetric nurses or midwives provide intrapartum and immediate postnatal care but not at a decision‐making level, and a medical doctor is present for the birth. (c) Shared models of care, where responsibility for the organisation and delivery of care, throughout initial booking to the postnatal period, is shared between different health professionals.

At various points during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period, responsibility for care can shift to a different provider or group of providers. Care is often shared by family doctors and midwives, by obstetricians and midwives, or by providers from all three groups. In some countries (e.g. Canada and The Netherlands), the midwifery scope of practice is limited to the care of women experiencing uncomplicated pregnancies, while in other countries (e.g. United Kingdom, France, Australia and New Zealand), midwives provide care to women who experience medical and obstetric complications in collaboration with medical colleagues. In addition, maternity care in some countries (e.g. Republic of Ireland, Iran and Lebanon), is predominantly provided by a midwife but is obstetrician‐led, in that the midwife might provide the actual care, but the obstetrician assumes overall responsibility for the care provided to the woman throughout her ante‐, intra‐ and postpartum periods.

How the intervention might work

Continuity of care is a means of delivering care in a way which acknowledges that a woman’s health needs are not isolated events, and should be managed over time (Reid 2002). This longitudinal aspect allows a relationship to develop between patients and their providers of care, and contributes to the patients' perception of having a provider who has knowledge of their medical history, and similarly an expectation that a known provider will care for them in the future (Haggerty 2003). Continuity refers to a ‘coordinated and smooth progression of care from the patient’s point of view’ (Freeman 2007) and therefore woman‐centredness is an important aspect in the delivery of continuity of care.

The general literature on continuity notes that a lack of clarity in definition and measurement of different types of continuity has been one of the limitations in research in this field (Haggerty 2003). Continuity has been defined by Freeman 2007 as having three major types ‐ management, informational and relationship. Management continuity involves the communication of both facts and judgements across team, institutional and professional boundaries, and between professionals and patients. Informational continuity concerns the timely availability of relevant information. Relationship continuity means a therapeutic relationship of the service user with one or more health professionals over time. Relationship/personal continuity over time has been found to have a greater effect on user experience and outcome (Saultz 2003; Saultz 2004; Saultz 2005). It has been argued that neither management nor informational continuity can compensate for lack of an ongoing relationship (Guthrie 2008). Midwife‐led continuity models of care have generally aimed to improve continuity of care over a period of time. Some models of midwife‐led care offer continuity with a group of midwives, and others offer personal or relational continuity, and thus the models of care that are the foci of this review are defined as follows.

Why it is important to do this review

There has been a lack of a single source of synthesised evidence on the effectiveness of midwife‐led continuity models of care when compared with other models of care. This review attempts to provide this evidence.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to compare the effects of midwife‐led continuity models of care with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants. We also explore whether the effects of midwife‐led continuity of care are influenced by: 1) models of midwife‐led care that provide differing levels of relationship continuity; 2) varying levels of obstetrical risk.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials including trials using individual‐ or cluster‐randomisation methods. We also included quasi‐randomised trials, where allocation may not have been truly random (e.g. where allocation was alternate or not clear).

Types of participants

Pregnant women.

Types of interventions

Models of care are classified as midwife‐led continuity of care, and other or shared care on the basis of the lead professional in the antepartum and intrapartum periods. In midwife‐led continuity models of care, the midwife is the woman's lead professional, but one or more consultations with medical staff are often part of routine practice. Other models of care include: a) where the physician/obstetrician is the lead professional, and midwives and/or nurses provide intrapartum care and in‐hospital postpartum care under medical supervision; b) shared care, where the lead professional changes depending on whether the woman is pregnant, in labour or has given birth, and on whether the care is given in the hospital, birth centre (free standing or integrated) or in community setting(s); and c) where the majority of care is provided by physicians or obstetricians.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Birth and immediate postpartum

Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal)

Caesarean birth

Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum)

Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors)

Intact perineum

Neonatal

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks)

All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death

Secondary outcomes

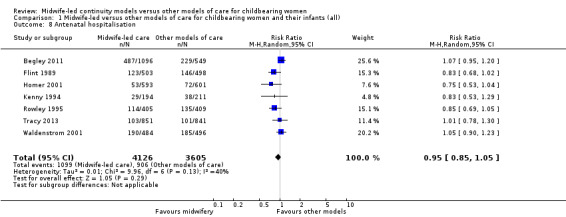

Antenatal hospitalisation

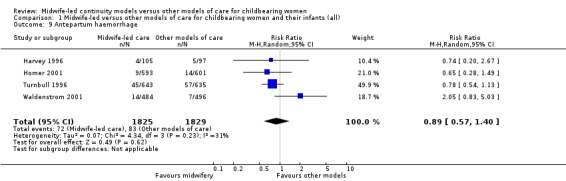

Antepartum haemorrhage

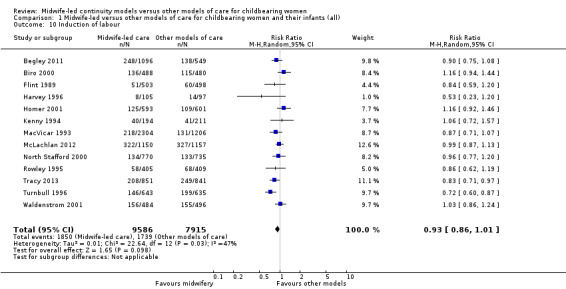

Induction of labour

Amniotomy

Augmentation/artificial oxytocin during labour

No intrapartum analgesia/anaesthesia

Opiate analgesia

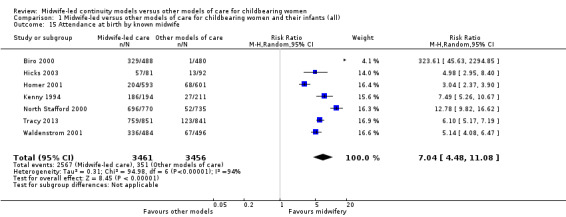

Attendance at birth by known midwife

Episiotomy

Perineal laceration requiring suturing

Mean labour length (hours)

Postpartum haemorrhage

Breastfeeding initiation

Duration of postnatal hospital stay (days)

Low birthweight (less than 2500 g)

Five‐minute Apgar score less than or equal to seven

Neonatal convulsions

Admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit

Mean length of neonatal hospital stay (days)

Fetal loss less than 24 weeks and neonatal death

Fetal loss equal to/after 24 weeks and neonatal death

Perceptions of control during labour and childbirth

Mean number of antenatal visits

Maternal death

Cord blood acidosis

Postpartum depression

Any breastfeeding at three months

Prolonged perineal pain

Pain during sexual intercourse

Urinary incontinence

Faecal incontinence

Prolonged backache

Breastfeeding on hospital discharge (not pre‐specified)

Maternal satisfaction (not pre‐specified)

Cost (not pre‐specified)

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (25 January 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 20,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate the PCG Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group in The Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth Group review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included, Excluded, Awaiting Classification or Ongoing).

For search methods used in an earlier update of this review (Hatem 2008), seeAppendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched for further studies in the reference list of the studies identified.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see (Sandall 2015).

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the three reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

One of the review authors (D Devane) is a co‐author of one of the included studies (Begley 2011), so was not involved in data extraction or in the 'Risk of bias' assessment for this study.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE Handbook. In order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons of midwife‐led versus all other models of care for childbearing women and their infants.

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks)

All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death

Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors)

Caesarean birth

Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum)

Intact perineum

Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal)

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias. We have not downgraded evidence for heterogeneity with an I² < 60%. We have not downgraded for risk of bias due to lack of blinding.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, as appropriate, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We included a cluster‐randomised trial in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials (North Stafford 2000). This trial found a negative ICC so no adjustment was made for clustering. We considered it reasonable to combine the results from cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

Other unit of analysis issues

Multiple pregnancies were included and both infants included in the denominator.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014).

As there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or where substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect had not been clinically meaningful, we would not have combined trials. The results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Caseload versus team models of midwifery care

Low‐risk versus mixed‐risk status

The following outcomes were used in subgroup analyses.

Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal)

Caesarean birth

Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum)

Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors)

Intact perineum

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks)

All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 88 citations relating to 38 studies in total. The updated search in May 2015 identified 11 new reports. Four were additional reports of an already included study McLachlan 2012; three new reports were included as Tracy 2013; two reports were excluded (Famuyide 2014; Gu 2013); and one was an additional reports of an excluded study (Walker 2012). A final report, Allen 2013, was eligible for the review and included, though this trial was a feasibility study and presents no usable data.

The updated search in January 2016 identified three new reports relating to three already included studies in the review (Begley 2011; McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013). Additional data were extracted from these new reports on the following outcomes: cost (economic cost of care analysis) Begley 2011; and maternal satisfaction (maternal experiences of childbirth) McLachlan 2012. These data were reported narratively. No additional data were extracted from the additional report of Tracy 2013 which reports on the number of midwives and health professionals seen by a subset of publicly funded pregnant women.

Included studies

We included 15 trials involving 17,674 randomised women in total (Allen 2013; Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). SeeCharacteristics of included studies table.

Included studies were conducted in the public health systems in Australia, Canada, Ireland and the United Kingdom with variations in model of care, risk status of participating women and practice settings. The Zelen method was used in three trials (Flint 1989; Homer 2001; MacVicar 1993), and one trial used cluster‐randomisation (North Stafford 2000).

Four studies offered a caseload model of care (McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996) and 10 studies provided a team model of care: (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; Rowley 1995; Waldenstrom 2001). The composition and modus operandi of the teams varied among trials. Levels of continuity (measured by the percentage of women who were attended during birth by a known carer varied between 63% to 98% for midwife‐led continuity models of care to 0.3% to 21% in other models of care).

Eight studies compared a midwife‐led continuity model of care with a shared model of care (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995), three studies compared a midwife‐led continuity model of care with medical‐led models of care (Harvey 1996; MacVicar 1993; Turnbull 1996), and three studies compared midwife‐led continuity of care with various options of standard care including shared, medical‐led and shared care (McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013; Waldenstrom 2001).

Participating women received ante‐, intra‐ and postpartum care in 13 studies (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001), and antenatal and intrapartum care only in one study (MacVicar 1993).

Some midwife‐led continuity models included routine visits to the obstetrician or family physicians (GPs), or both. The frequency of such visits varied. Such visits were dependent on women's risk status during pregnancy (Biro 2000); routine for all women (one to three visits) (Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Rowley 1995; Waldenstrom 2001), or based on the development of complications (Hicks 2003; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996) or antenatal care from midwives and, if desired by the woman, from the woman's general practitioner (Begley 2011).

Women were classified as being at low risk of complications in eight studies (Begley 2011; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001) and as 'low and high' and 'high' in six studies (Biro 2000; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013).

The midwifery models of care were hospital‐based in four studies (Biro 2000; MacVicar 1993; Rowley 1995; Waldenstrom 2001), or offered (i) antenatal care in an outreach community‐based clinic and intra‐ and postpartum care in hospital (Homer 2001); (ii) ante‐ and postpartum community‐based care with intrapartum hospital‐based care (Hicks 2003; North Stafford 2000; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996) (iii) antenatal and postnatal care in the hospital and community settings with intrapartum hospital‐based care or (iv) postnatal care in the community with hospital‐based ante‐ and intrapartum care (Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Kenny 1994; McLachlan 2012). Four studies offered intrapartum care in home‐like settings, either to all women in the trial (Waldenstrom 2001), or to women receiving midwife‐led continuity of care only (Begley 2011; MacVicar 1993; Turnbull 1996).

Excluded studies

We excluded 22 studies (Berglund 1998; Berglund 2007; Bernitz 2011; Chambliss 1991; Chapman 1986; Famuyide 2014; Giles 1992; Gu 2013; Heins 1990; Hildingsson 2003; Hundley 1994; James 1988; Kelly 1986; Klein 1984; Law 1999; Marks 2003; Runnerstrom 1969; Slome 1976; Stevens 1988; Tucker 1996; Waldenstrom 1997; Walker 2012). SeeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

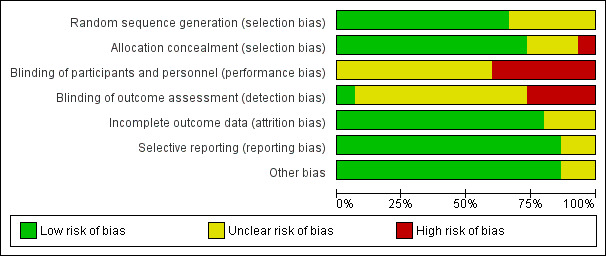

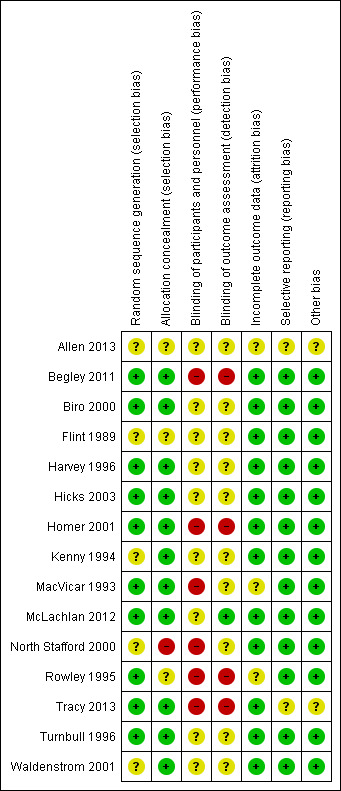

SeeFigure 1; Figure 2 for summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Ten studies reported genuine random methods of generation of the randomisation sequence (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996). Five gave no or insufficient information to form a clear judgement (Allen 2013; Flint 1989; Kenny 1994; North Stafford 2000; Waldenstrom 2001).

Allocation concealment was judged low risk of bias for 11 studies (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Harvey 1996, Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). Three studies were judged unclear risk of bias: Rowley 1995 and Allen 2013 gave no information about the process of random allocation; and Flint 1989 used sealed opaque envelopes but did not specify any numbering. The North Stafford 2000 trial was a cluster‐randomised trial, whereby allocation concealment was not possible and it was judged high risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Six of the included studies were judged as high risk in blinding of participants and personnel (Begley 2011; Homer 2001; MacVicar 1993; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013) and nine studies were of unclear risk of bias (Allen 2013; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Kenny 1994; McLachlan 2012; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001).

One study was at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment (McLachlan 2012), four were judged as high risk of bias (Begley 2011; Homer 2001; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013), and 10 studies were at unclear risk of bias (Allen 2013; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; North Stafford 2000; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001).

Incomplete outcome data

Twelve of the included studies were judged at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data on the basis that attrition rate was less than 20% for all outcomes (other than satisfaction), or missing outcome data were balanced across groups (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). Two of the studies (MacVicar 1993; Rowley 1995) did not provide sufficient information on loss to follow‐up and were judged as unclear. A feasibility study was also judged as unclear (Allen 2013).

Selective reporting

All outcomes stated in the methods section were adequately reported in the results in 13 studies (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). Two trials were judged to be of unclear risk of bias due to reporting: Allen 2013, a feasibility recruiting just one woman to the intervention and Tracy 2013, where we emailed the trial authors for clarification of data and additional data.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were identified in most included studies. A feasibility study (Allen 2013) was considered of unclear risk, as was Tracy 2013, where a small proportion of women were crossed‐over from each arm.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We used random‐effects for all analyses. Where we identified statistical heterogeneity (I² > 30%) we have reported the values of both Tau² and I². Because our subgroup analyses (reported below) did not generally explain heterogeneity found in specific primary outcomes, we discuss additional sources of heterogeneity below and in the discussion section of the review.

Comparison 1 (main comparison): midwife‐led continuity models of care versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants ‐ all trials

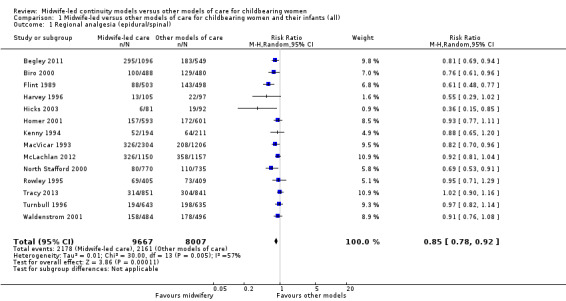

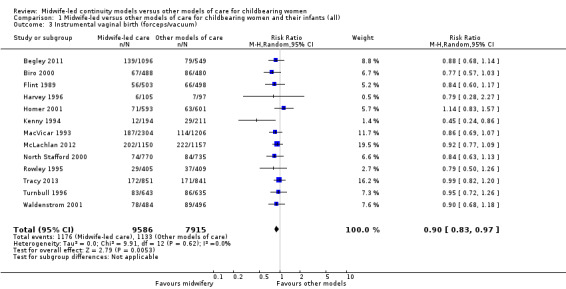

Primary outcomes

Women randomised to midwife‐led continuity models of care were, on average, less likely to experience:

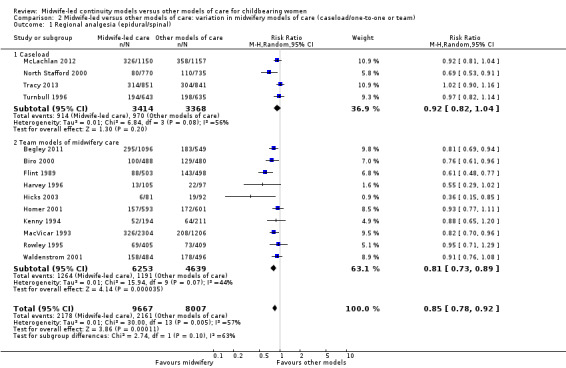

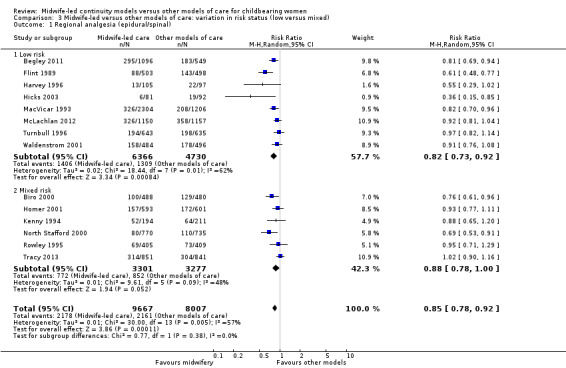

regional analgesia (epidural/spinal) (average risk ratio (RR) 0.85, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.92; participants = 17,674; studies = 14; I² = 57%; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1);

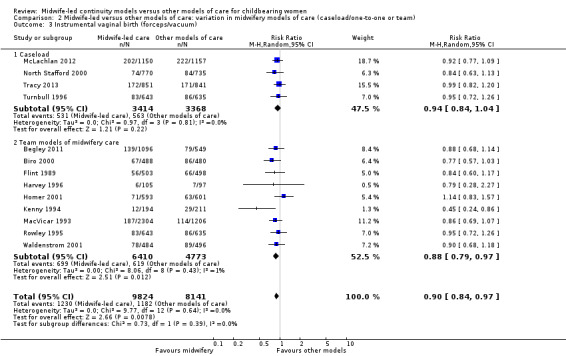

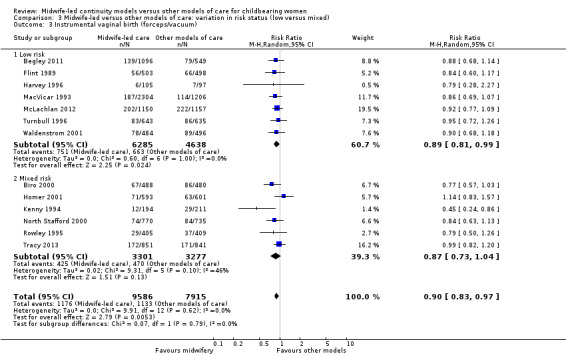

instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum) (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97; participants = 17,501; studies = 13; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.3);

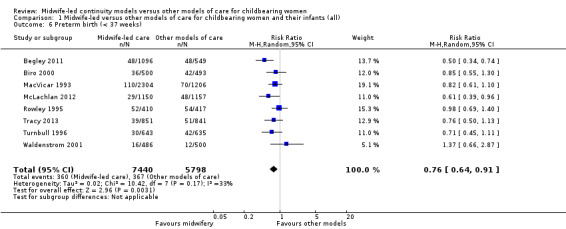

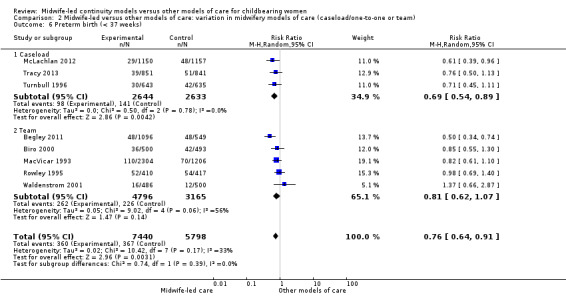

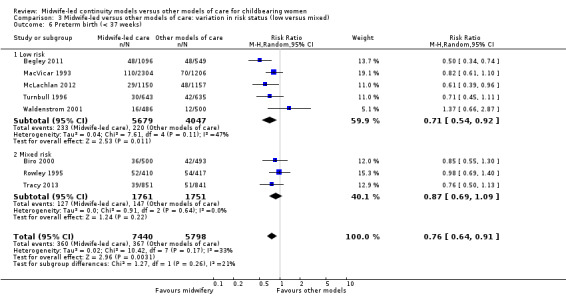

preterm birth < 37 weeks (average RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91; participants = 13,238; studies = eight; I² = 33%; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.6).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 1 Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 3 Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 6 Preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

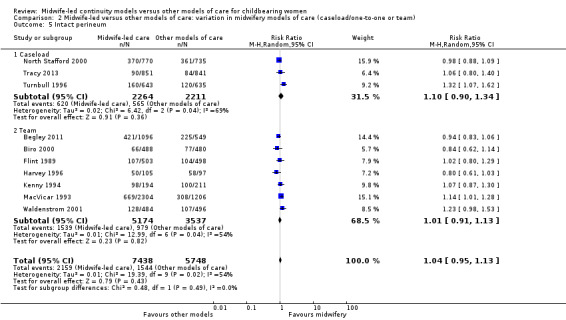

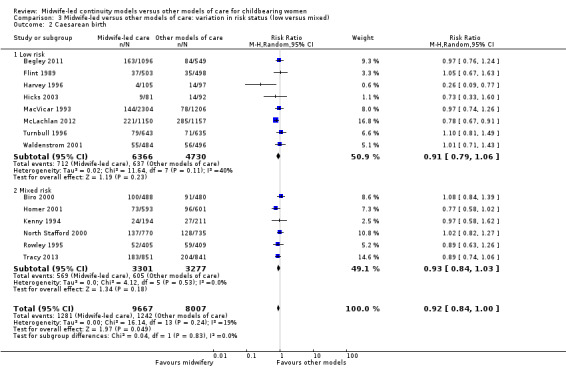

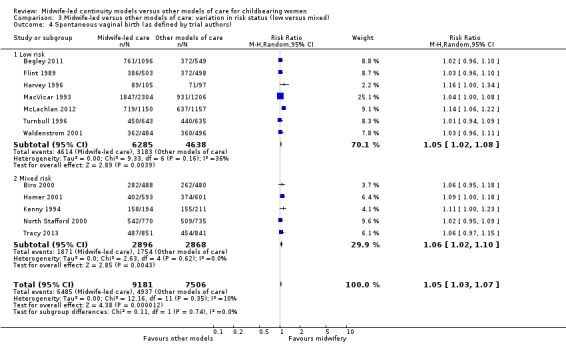

We conducted pre‐specified subgroup analysis to investigate heterogeneity in the above outcomes of regional analgesia and preterm birth. Assumed differences between caseload or team models of care versus other models of care could not explain the heterogeneity for these outcomes, and neither could potential differences between low‐risk and mixed‐risk groups of pregnant women (see analyses for regional analgesia Analysis 2.1 and Analysis 3.1 and for preterm birth Analysis 2.6 and Analysis 3.6).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in midwifery models of care (caseload/one‐to‐one or team), Outcome 1 Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal).

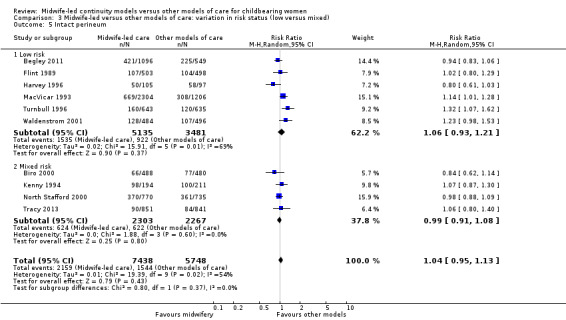

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in risk status (low versus mixed), Outcome 1 Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in midwifery models of care (caseload/one‐to‐one or team), Outcome 6 Preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in risk status (low versus mixed), Outcome 6 Preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

Women randomised to midwife‐led continuity models of care were on average more likely to experience:

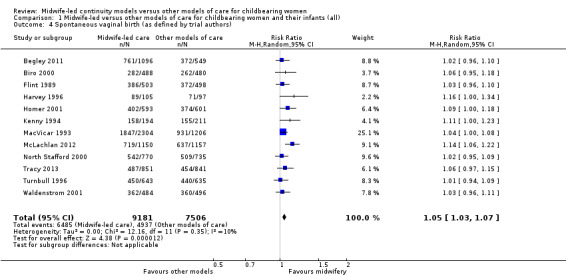

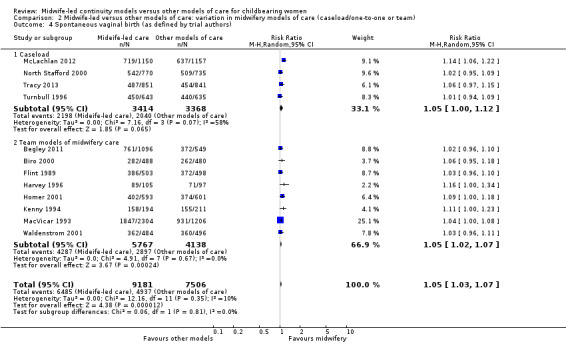

a spontaneous vaginal birth (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.07; participants = 16,687; studies = 12; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 4 Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors).

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the following outcomes:

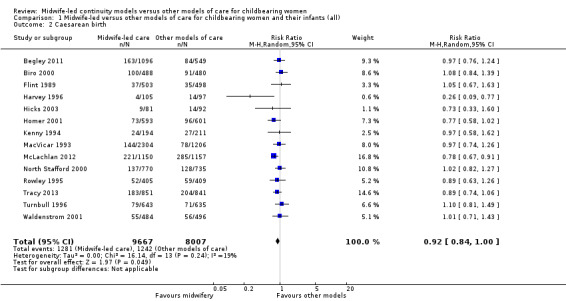

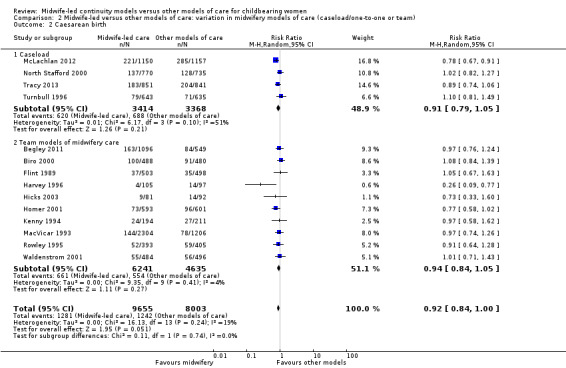

caesarean birth (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.00; participants = 17,674; studies = 14; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.2);

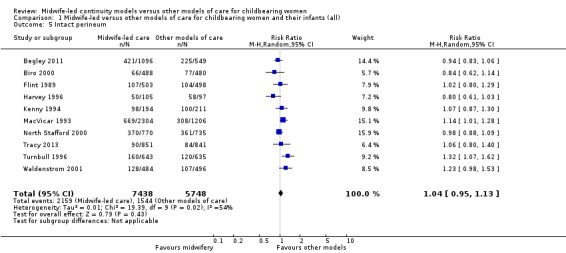

intact perineum (average RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.13; participants = 13,186; studies = 10; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.5); there was moderate heterogeneity for this outcome (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.01; I² = 54%), and this could not be attributed to differences in the pre‐specified subgroups (see below and Analysis 2.5 and Analysis 3.5).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 2 Caesarean birth.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 5 Intact perineum.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in midwifery models of care (caseload/one‐to‐one or team), Outcome 5 Intact perineum.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in risk status (low versus mixed), Outcome 5 Intact perineum.

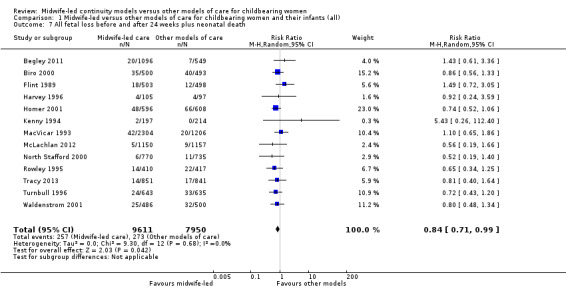

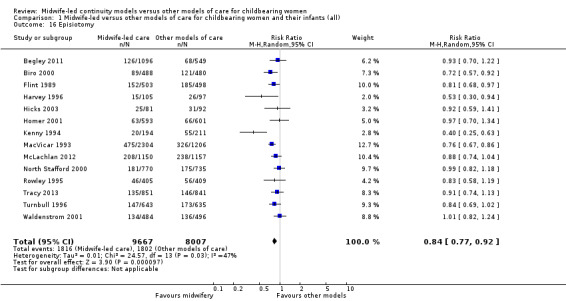

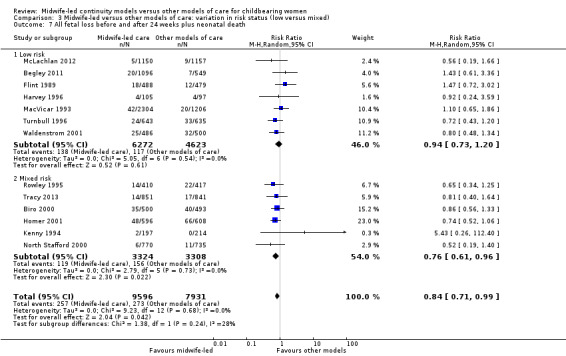

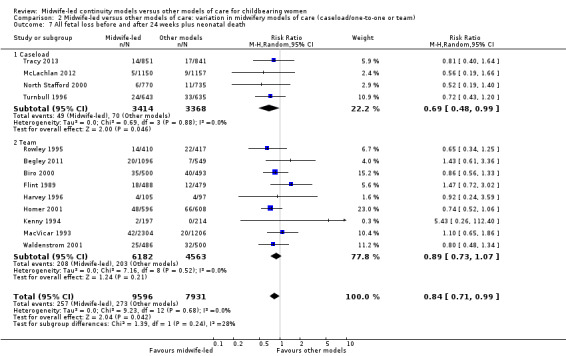

The difference in the average treatment effect in all fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death across included trials between women allocated to midwife‐led continuity models of care and women allocated to other models has an average RR of 0.84, with 95% CI 0.71 to 0.99. Given that (i) the 95% CI just reaches 0.99 and (ii) the absence of measurable heterogeneity in this outcome analysis, the probability is that midwife‐led continuity models of care are associated with a reduction in fetal loss and neonatal death by approximately 16%.

all fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death (average RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.99; participants = 17,561; studies = 13; high quality evidence) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 7 All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death.

Secondary outcomes

Women randomised to midwife‐led continuity models of care were, on average, less likely to experience:

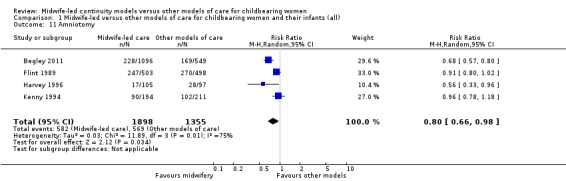

amniotomy (average RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.98; participants = 3253; studies = four; I² = 75%) (Analysis 1.11);

episiotomy (average RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92; participants = 17,674; studies = 14; I² = 47%) (Analysis 1.16);

fetal loss less than 24 weeks and neonatal death (average RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.98; participants = 15,645; studies = 11) (Analysis 1.27).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 11 Amniotomy.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 16 Episiotomy.

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 27 Fetal loss less than 24 weeks and neonatal death.

Women randomised to midwife‐led continuity models of care were on average more likely to experience:

no intrapartum analgesia/anaesthesia (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.37; participants = 10,499; studies = seven; I² = 49%) (Analysis 1.13);

a longer mean length of labour (hours) (mean difference (MD) 0.50, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.74; participants = 3328; studies = three) (Analysis 1.18); however, there was evidence of skewness in the data from one of the trials in the analyses of length of labour (Turnbull 1996);

women allocated to midwife‐led continuity models of care were more likely to be attended at birth by a known midwife (RR 7.04, 95% CI 4.48 to 11.08; participants = 6917; studies = seven); however, the effect estimates for individual studies are highly variable, as reflected in substantial statistical heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.31; I² = 94%; Analysis 1.15).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 13 No intrapartum analgesia/anaesthesia.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 18 Mean labour length (hrs).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 15 Attendance at birth by known midwife.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the following outcomes:

antenatal hospitalisation (average RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.05; participants = 7731; studies = seven; I² = 40%) (Analysis 1.8);

antepartum haemorrhage (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.40; participants = 3654; studies = four; I² = 31%) (Analysis 1.9);

induction of labour (average RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.01; participants = 17,501; studies = 13; I² = 47%) (Analysis 1.10);

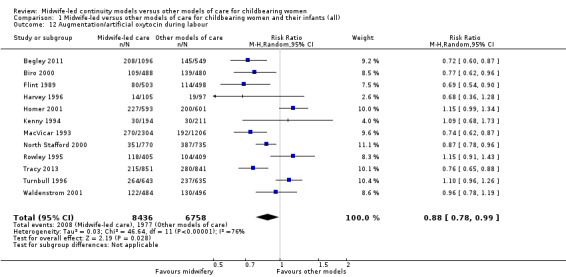

augmentation/artificial oxytocin during labour (average RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.99; participants = 15,194; studies = 12; I² = 76%) (Analysis 1.12);

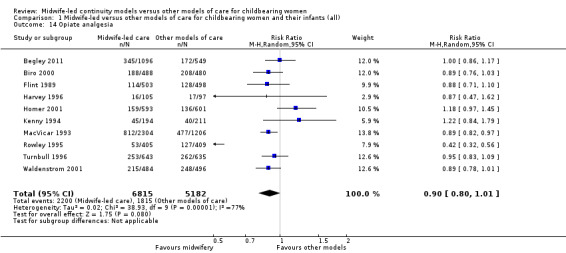

opiate analgesia (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.01; participants = 11,997; studies = 10; I² = 77%) (Analysis 1.14);

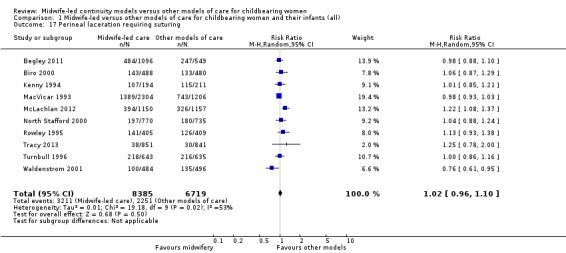

perineal laceration requiring suturing (average RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.10; participants = 15,104; studies = 10; I² = 53%) (Analysis 1.17);

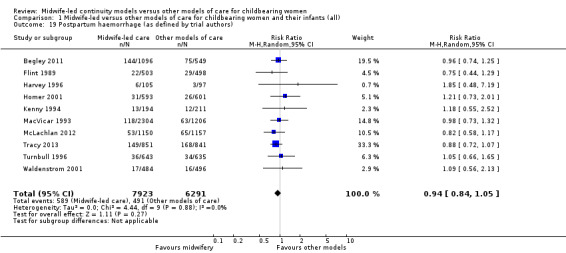

postpartum haemorrhage (average RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.05; participants = 14,214; studies = 10) (Analysis 1.19);

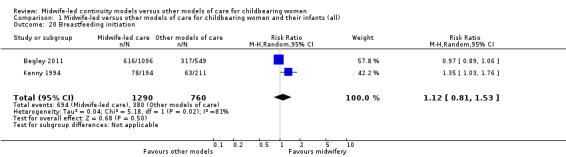

breastfeeding initiation (average RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.53; participants = 2050; studies = two; I² = 81%) (Analysis 1.20);

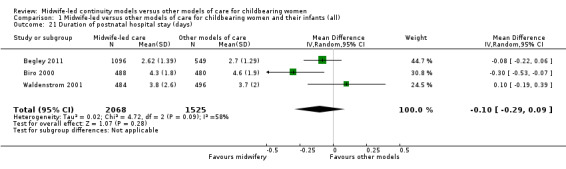

mean length of postnatal hospital stay (days) (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.09; participants = 3593; studies = three; Tau² = 0.02, I² = 58%) (Analysis 1.21);

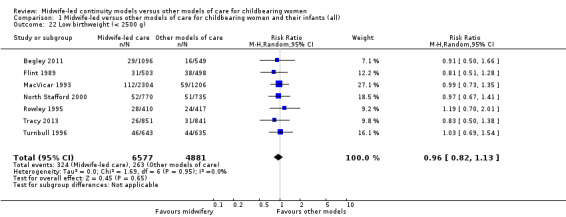

low birthweight infant (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.13; participants = 11,458; studies = seven) (Analysis 1.22);

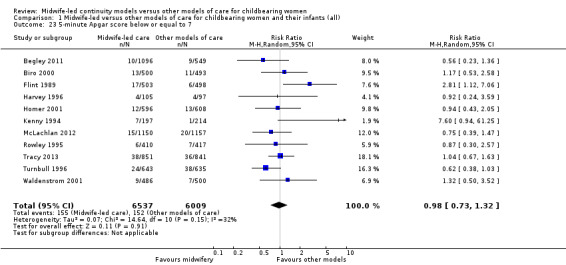

five‐minute Apgar score less than or equal to seven (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.32; participants = 12,546; studies = 11; I² = 32%) (Analysis 1.23);

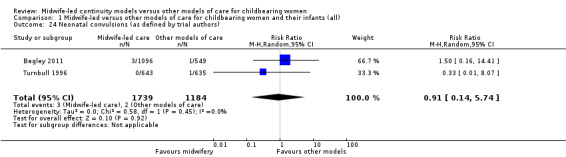

neonatal convulsions (average RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.14 to 5.74; participants = 2923; studies = two) (Analysis 1.24);

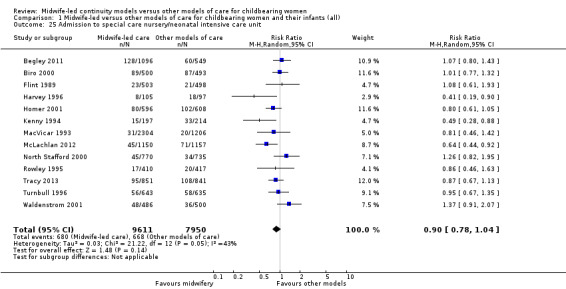

admission of infant to special care or neonatal intensive care unit(s) (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.04; participants = 17,561; studies = 13; I² = 43%) (Analysis 1.25);

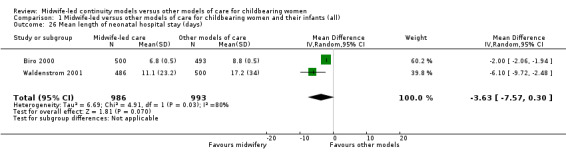

mean length of neonatal hospital stay (days) (MD ‐3.63, 95% CI ‐7.57 to 0.30, participants = 1979; studies = two; Tau² = 6.69, I² = 80%) (Analysis 1.26);

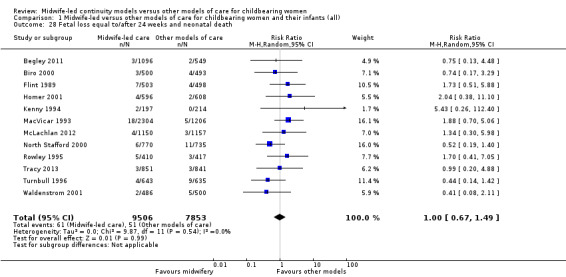

fetal loss equal to/after 24 weeks and neonatal death (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.49; participants = 17,359; studies = 12; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.28).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 8 Antenatal hospitalisation.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 9 Antepartum haemorrhage.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 10 Induction of labour.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 12 Augmentation/artificial oxytocin during labour.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 14 Opiate analgesia.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 17 Perineal laceration requiring suturing.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 19 Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by trial authors).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 20 Breastfeeding initiation.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 21 Duration of postnatal hospital stay (days).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 22 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 23 5‐minute Apgar score below or equal to 7.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 24 Neonatal convulsions (as defined by trial authors).

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 25 Admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 26 Mean length of neonatal hospital stay (days).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), Outcome 28 Fetal loss equal to/after 24 weeks and neonatal death.

There was substantial statistical heterogeneity in many of the analyses. The I² value was greater than 50% for 10 outcomes (antenatal hospitalisation, amniotomy, augmentation, opiate analgesia, attendance at birth by known carer, intact perineum, perineum requiring suturing, duration of postnatal hospital stay, duration of neonatal stay, breastfeeding initiation, and greater than 30% for a further six (antepartum haemorrhage, induction of labour, episiotomy, five‐minute Apgar score less than seven, preterm birth, admission to neonatal care). It is likely that heterogeneity could be due to the nature of the complexity of the intervention of a model of care, with variation in case mix and organisational setting.

Investigation of publication bias

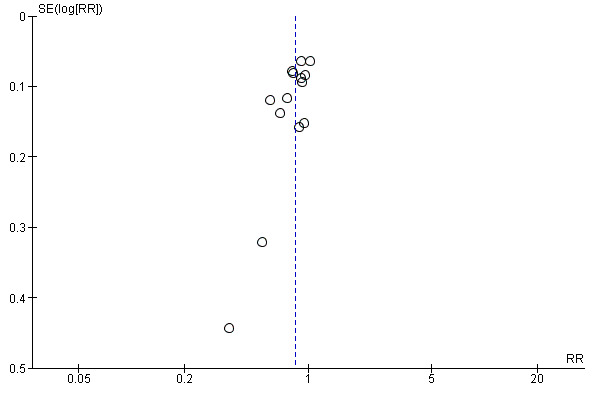

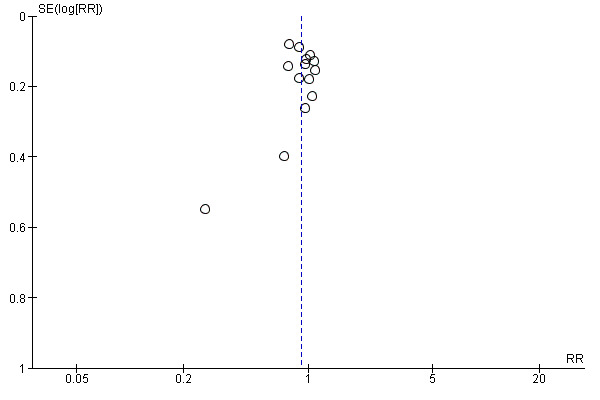

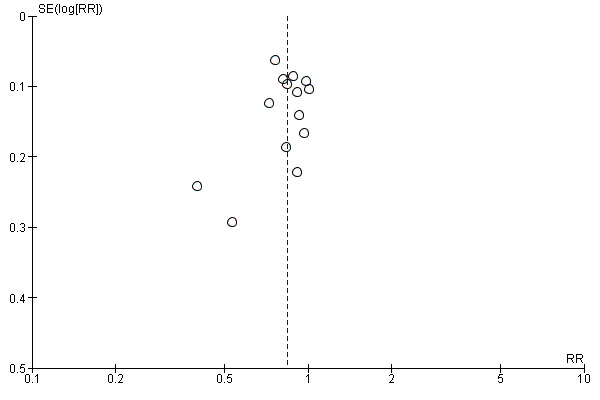

Visual inspection of funnel plots for analyses where there were 10 or more studies (Analysis 1.1, Analysis 1.2, Analysis 1.3, Analysis 1.4, Analysis 1.5, Analysis 1.7, Analysis 1.10, Analysis 1.12, Analysis 1.14, Analysis 1.16, Analysis 1.17, Analysis 1.19, Analysis 1.23, Analysis 1.25, Analysis 1.27 and Analysis 1.28) suggested little evidence of asymmetry for most analyses. For three analyses (Analysis 1.1 regional analgesia, Analysis 1.2 caesarean delivery and Analysis 1.16 episiotomy), there was a some suggestion of asymmetry, though in all cases this was due to two small trials with large treatment effects in the same direction (Harvey 1996 and Hicks 2003, see Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5). There is therefore no strong evidence of reporting bias, though this is difficult to detect with the number of studies in this review, and whether it exists and the extent to which it affects the results may be clarified when more studies have been conducted.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), outcome: 1.1 Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), outcome: 1.2 Caesarean birth.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Midwife‐led versus other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all), outcome: 1.16 Episiotomy.

Outcomes reported in single trials or not at all

It was not possible to analyse the following outcomes, either because data were not reported by any studies or they were reported in a way that did not allow extraction of the necessary data for meta‐analysis, or losses and exclusions were more than 20% of the randomised participants. No maternal deaths were reported. Only one trial reported the following outcomes: mean number of antenatal visits, perceptions of control, breastfeeding on discharge and postpartum depression and so results were not included in a meta‐analysis. No trials reported on longer‐term outcomes: any breastfeeding at three months; prolonged perineal pain; pain during sexual intercourse; urinary incontinence; faecal incontinence; and prolonged backache.

Subgroup analyses

Comparison 2: variation in midwifery models of care (caseload or one‐to‐one versus team)

Four trials randomised 6782 women to compare a caseload model of care (defined as one midwife carrying responsibility for a defined caseload of women in partnership with a midwife partner) with other models of care (McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996). Caseload size was reported to be 45 women per midwife per year (McLachlan 2012), 35 to 40 women (North Stafford 2000), 40 women (Tracy 2013) and 32.4 women per midwife (Turnbull 1996). Ten trials randomised 11,183 women to compare team models of midwifery (defined as a group of midwives sharing responsibility for a caseload of women) with other models of care (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; Rowley 1995; Waldenstrom 2001).

On the whole, there was no evidence of a difference between the caseload and team subgroups for any of the outcomes included in the subgroup analysis, which included caesarean section, instrumental vaginal birth, spontaneous vaginal birth, intact perineum, preterm birth < 37 weeks and all fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death.

There were borderline differences between subgroups for the outcome of regional analgesia (Test for subgroup differences: (P = 0.10), I² = 63.4%). Both caseload and team care (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.04; participants = 6782; studies = four; I² = 56%) and other models of care (average RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.89; participants = 10,892; studies = 10; I² = 44%) had substantial heterogeneity. Due to heterogeneity and to the small number of trials in each subgroup, we would advise caution when interpreting this result (Analysis 2.1).

Comparison 3: variation in risk status (low risk versus mixed)

Eight trials randomised 11,195 women to compare midwife‐led continuity models of care versus other models of care in women defined to be at low risk by trial authors (Begley 2011; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). Six trials randomised over 6578 women to compare midwife‐led continuity models of care with other models of care in women defined to be at mixed risk of complications by trial authors (Biro 2000; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013;). Of these, two trials excluded women who booked late ‐ after 24 weeks' gestation (Biro 2000; Homer 2001) and 16 weeks' gestation (Kenny 1994). Two trials excluded women with a substance misuse problem (Kenny 1994; Rowley 1995), and two trials excluded women with significant medical disease or previous history of a classical caesarean or more than two caesareans (Homer 2001), or women requiring admission to the maternal fetal medicine unit (Biro 2000).

There was no evidence of differences in treatment effect between the low risk and mixed risk subgroups for any of the outcomes included (see Analysis 3.1 to Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Midwife‐led versus other models of care: variation in risk status (low versus mixed), Outcome 7 All fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal death.

Maternal satisfaction

Due to the lack of consistency in conceptualisation and measurement of women's experiences and satisfaction of care, a narrative synthesis of such data are presented. Ten studies reported maternal satisfaction with various components of the childbirth experiences (Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Kenny 1994; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; Rowley 1995; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001).

Given the ambiguity surrounding the concept of satisfaction, it was not surprising to find inconsistency in the instruments, scales, timing of administration and outcomes used to 'measure' satisfaction across studies. Because of such heterogeneity and as might be expected, response rates of lower than 80% for most of these studies, meta‐analysis for the outcome of satisfaction was considered inappropriate and was not conducted.

Satisfaction outcomes reported in the included studies included maternal satisfaction with information, advice, explanation, venue of delivery, preparation for labour and birth, as well as giving choice for pain relief and behaviour of the carer. One study assessed perceptions of control in labour (Flint 1989), using a three‐point scale. For convenience and ease of understanding, tabulated results of the overall satisfaction or indicators which directly relate to staff attitude, or both, are presented in Table 2. In brief, the majority of the included studies, showed a higher level of satisfaction in various aspects of care in the midwife‐led continuity compared to the other models of care.

1. Women's experiences of care.

| Satisfaction | Intervention (n/N) | Control (n/N) | Relative rate | 95% CI | Statistical test | P value |

| Flint 1989* | ||||||

| Staff in labour (very caring) | 252/275 (92%) | 208/256 (81%) | 1.1 | 1.0‐1.2 | ||

| Experience of labour (wonderful/enjoyable) | 104/246 (42%) | 72/223 (32%) | 1.3 | 1.0‐1.8 | ||

| Satisfaction with pain relief (very satisfied) | 121/209 (58%) | 104/205 (51%) | 1.1 | 0.9‐1.4 | ||

| Very well prepared for labour | 144/275 (52%) | 102/254 (40%) | 1.3 | 1.0‐1.7 | ||

| MacVicar 1993 | N = 1663 | N = 826 | Difference | |||

| Very satisfied with antenatal care | 52% | 44% | 8.3% | 4.1‐12.5 | ||

| Very satisfied with care during labour | 73% | 60% | 12.9% | 9.1‐16.8 | ||

| Kenny 1994 | N = 213 | N = 233 | ||||

| Carer skill, attitude and communication (antenatal care) | 57.1/60 | 47.7/60 | t = 12.4 | 0.0001 | ||

| Convenience and waiting (antenatal care) | 14.8/20 | 10.9/20 | t = 10.1 | 0.0001 | ||

| Expectation of labour/birth (antenatal care) | 9.8/18 | 9.3/18 | t = 1.4 | 0.16 | ||

| Asking questions (antenatal care) | 8.5/12 | 6.9/12 | t = 6.6 | 0.0001 | ||

| Information/communication (labour and birth) | 28.3/30 | 24.8/30 | t = 7.48 | 0.0001 | ||

| Coping with labour (labour and birth) | 20.9/30 | 19.3/30 | t = 2.83 | 0.005 | ||

| Midwife skill/caring (labour and birth) | 22.7/24 | 21.3/24 | t = 3.44 | 0.0007 | ||

| Help and advice (postnatal care) | 21.0/24 | 19.7/24 | t = 1.88 | 0.06 | ||

| Midwife skill and communication (postnatal care) | 16.6/18 | 15.4/18 | t = 4.48 | 0.0001 | ||

| Managing baby (postnatal care) | 8.7/12 | 8.5/12 | t = 0.77 | 0.77 | ||

| Self‐rated health (postnatal care) | 7.5/12 | 7.1/12 | t = 1.67 | 0.10 | ||

| Rowley 1995 | OR | |||||

| Encouraged to ask questions | N/A | 4.22 | 2.72‐6.55 | |||

| Given answers they could understand | N/A | 3.03 | 1.33‐7.04 | |||

| Able to discuss anxieties | N/A | 3.60 | 2.28‐5.69 | |||

| Always had choices explained to them | N/A | 4.17 | 1.93‐9.18 | |||

| Participation in decision making | N/A | 2.95 | 1.22‐7.27 | |||

| Midwives interested in woman as a person | N/A | 7.50 | 4.42‐12.80 | |||

| Midwives always friendly | N/A | 3.48 | 1.92 ‐ 6.35 | |||

| Turnbull 1996 | n/N | n/N | Mean difference ‐ satisfaction score | |||

| Antenatal care | 534/648 | 487/651 | 0.48 | 0.55‐0.41 | ||

| Intrapartum care | 445/648 | 380/651 | 0.28 | 0.37‐0.18 | ||

| Hospital‐based postnatal care | 445/648 | 380/651 | 0.57 | 0.70‐0.45 | ||

| Home‐based postnatal care | 445/648 | 380/651 | 0.33 | 0.42‐0.25 | ||

| Waldenstrom 2001 | % | % | OR | |||

| Overall antenatal care was very good (strongly agree) | 58.2% | 39.7% | 2.22 | 1.66‐2.95 | < 0.001 | |

| Happy with the physical aspect of intrapartum care (strongly agree) | 58.6% | 42.5% | 1.94 | 1.46‐2.59 | < 0.001 | |

| Happy with the emotional aspect of intrapartum care (strongly agree) | 58.8% | 44.0% | 1.78 | 1.34‐2.38 | < 0.001 | |

| Overall postnatal care was very good (strongly agree) | 37.6% | 33.2% | 1.27 | 0.97‐1.67 | 0.08 | |

| Hicks 2003** | ||||||

| Care and sensitivity of staff (antenatal) | 1.32 | 1.77 | Mean difference? | 0.0000 | ||

| Care and sensitivity of staff (labour and delivery) | 1.26 | 1.58 | Mean difference? | 0.008 | ||

| Care and sensitivity of staff (postpartum at home) | 1.24 | 1.57 | Mean difference? | 0.0000 | ||

| Harvey 1996 | ||||||

| Labour and Delivery Satisfaction Index + | 211 | 185 | 26 | 18.8‐33.1 | 0.001 | |

| Biro 2000 | ||||||

| Satisfaction with antenatal care (very good) | 195/344 (57%) | 100/287 (35%) | 1.24 | 1.13‐1.36 | 0.001 | |

| Satisfaction with intrapartum care (very good) | 215/241 (63%) | 134/282 (47%) | 1.11 | 1.03‐1.20 | 0.01 | |

| Satisfaction with postpartum care in hospital (very good) | 141/344 (41%) | 102/284 (31%) | 0.92 | 0.82‐1.04 | 0.22 |

*: 99% Confidence interval (CI) for Flint study was reported N/A: not available **:Mean satisfaction scores are reported: lower scale indicates higher satisfaction. Satisfaction scores were calculated on a 5‐point ordinal scale in which 1 = very satisfied and 5 = very dissatisfied.

A second study (McLachlan 2012) assessed women's experience of childbirth in a postal survey. Women receiving caseload midwifery care were more likely to rate their experience of childbirth as very positive overall. These women reported a more positive experience of pain overall and more often reported feeling very proud of themselves. Women also felt more in control and more able to cope physically and emotionally; all of these outcome data are taken directly from the Machlachlan 2015 report and displayed in our Table 3 below.

2. McLachlan 2015 Women's experiences of birth.

| Outcome measure |

Caseload % scored 6 or 7*, with (n) |

Standard % scored 6 or 7*, with (n) |

Caseload RR** (ref = standard) |

|

Overall experience of childbirth (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive) |

71.2(697/979) | 62.6(516/824) | 1.47(1.21,1.80) |

|

Pain intensity (1 = no pain at all; 7= worst imaginable pain) |

57.8(565/978) | 58.0(478/825) | 0.99(0.82,1.20) |

|

Pain in relation to expectations (1 = much worse than expected; 7 = much better than expected) |

26.1(256/979)) | 22.7(186/820) | 1.21(0.97,1.50) |

|

Pain overall (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive) |

26.8(260/971) | 21.8(177/813) | 1.31(1.06,1.63) |

|

Anxiety during labour (1 = not at all anxious; 7 = very anxious) |

28.7(280/975) | 32.2(265/823) | 0.854(0.69,1.04) |

|

Experience of control (1 = completely out of control; 7 = in complete control) |

35.4(344/973) | 27.4(225/822) | 1.45(1.19,1.78) |

|

Coping physically (1 = much worse than expected; 7 = much better than expected) |

53.0(519/979) | 46.0(379/824) | 1.32(1.10–1.60) |

|

Coping emotionally (1 = much worse than expected; 7 = much better than expected) |

53.5(524/979) | 47.2(389/824) | 1.29(1.07–1.56) |

|

Feeling proud of self (1 = not all proud; 7 = very proud) |

80.5(786/976) | 72.2(594/823) | 1.59(1.28–1.99) |

|

Felt free to express feelings (1 = disagree strongly; 7 = agree strongly) |

80.7(788/977) | 71.6(586/819) | 1.66(1.33–2.06) |

|

Support by midwife (1 = no support at all; 7 = a lot of support) |

91.3(889/974) | 77.6(629/810) | 3.01(2.28–3.97) |

|

Support by doctor (if present) (1 = no support at all; 7 = a lot of support) |

53.0(334/630) | 54.1(329/608) | 0.96(0.77–1.20) |

|

Support by partner at all; 7 = a lot of support) |

91.5(892/975) | 89.7(733/817) | 1.23(0.89–1.69) |

*Scored ‘6’ or ‘7’ on seven‐point scale where ‘1’ was most negative response and ‘7’ most positive.

**Relative Risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of rating statements as ‘6’ or ‘7’ on seven‐point scale, caseload/standard care.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the cluster‐randomised North Staffordshire trial from all outcomes in the primary comparison (comparison 1) for which it had contributed data (North Stafford 2000). This did not alter the findings for any outcome, which remained consistent with overall findings with all trials included. Similarly, a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes including only the studies rated at low risk of bias (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; McLachlan 2012; Turnbull 1996), found that there were only minor differences from the overall analyses. The main consequence was that confidence intervals were slightly wider, because of the smaller number of trials in the analysis. In no case were the conclusions of the analysis different. The primary outcome with the largest difference in this sensitivity analysis was preterm birth, where an analysis restricted to trials with lower risk of bias suggested a larger treatment effect: RR 0.64, (95% CI 0.51 to 0.81) compared with RR 0.77, (95% CI 0.62 to 0.94) in the overall analysis.

Economic analysis

Findings from economic analyses will vary depending on the structure of health care in a given country and what factors are included in the modelling. Due to the lack of consistency in measurement of economic evaluations, a narrative synthesis of such data are presented. Seven studies presented economic analysis in which various measures and items were included in the final cost estimation (Begley 2011; Flint 1987; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013; Young 1997).

Kenny 2015 reports an economic evaluation based on the Begley 2011 trial. Because the trial found no differences in the effect of type of care on any primary clinical outcome, the economic analysis compares only the costs of care rather than their cost‐effectiveness. Both midwifery‐led care and obstetric‐led care were shown to be equally safe and effective in the trial, but the costs of midwife‐led care were lower, contributing to a cost saving of EUR 182 per pregnant woman receiving midwife‐led care using an 'intention‐to‐treat' analysis.

Flint 1989 examined the costs for a subgroup of women (n = 49) and estimated costs for antenatal admission and antenatal care, and found antenatal care was 20% to 25% cheaper for women in the midwife‐led continuity of care group due to differences in staff costs. Women in the midwife‐led continuity of care group had fewer epidurals (GBP 19,360 versus GBP 31,460).

Kenny 1994 examined the costs of care in detail. The average cost/client in the antenatal period was AUD 158 midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 167 control. For high‐risk women the average cost/client was AUD 390 midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 437 control, and for low‐risk women AUD 119 midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 123 control. The average cost per woman for intrapartum care was AUD 219 midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 220 control and for postnatal care was AUD 745 midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 833 control. The total cost/woman was AUD 1122 for midwife‐led continuity of care and AUD 1220 control.