Abstract

Formalin and mercuric chloride-based low-viscosity polyvinyl alcohol (LV-PVA) are widely used by most diagnostic parasitology laboratories for preservation of helminth eggs and protozoan cysts and trophozoites in fecal specimens. Concerns about the toxicity of formalin and the difficulty of disposal of LV-PVA are powerful incentives to use alternate preservatives. Such alternatives have been marketed by several companies and are often presented as one-vial, non-mercuric chloride fixatives that aim at performing the same role as formalin and PVA combined. We compared five, one-vial commercial preservatives, two from Meridian Diagnostics, Inc. (Ecofix and sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin), and one each from Scientific Device Laboratories, Inc. (Parasafe), Alpha Tec Systems, Inc. (Proto-fix), and Streck Laboratories, Inc. (STF), with 10% formalin and LV-PVA. Fecal specimens obtained from patients in a Brazilian hospital were aliquoted within 12 h of collection into the seven preservatives mentioned above and were processed after 1 month at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Direct and concentrated permanent smears as well as concentrates for 20 positive specimens (a total of 259 processed samples) were prepared, stained according to the manufacturers' instructions, examined, and graded. Positive specimens contained one or more parasites with stages consisting of eggs, larvae, cysts, and a few trophozoites of Giardia intestinalis. Criteria for assessment of the preservatives included the quality of the diagnostic characteristics of helminth eggs, protozoan cysts, and trophozoites, ease of use, and cost. Acceptable alternatives to formalin for wet preparations were found. Ecofix was found to be comparable to the traditional “gold standard” LV-PVA for the visualization of protozoa in permanent stained smears. This study suggests that more acceptable alternatives to the traditional formalin and LV-PVA exist.

Formalin and low-viscosity polyvinyl alcohol (LV-PVA), two traditional stool fixatives, have been widely used in most public, private, and commercial laboratories for many years. These two fixatives have been and are still considered the “gold standard” in parasitology because they allow excellent long-term preservation of intestinal parasites (2). Formalin is considered an all-purpose fixative used to preserve helminth eggs, larvae, and protozoan cysts (2, 7). PVA is a plastic resin that contains Schaudinn's fixative, which is used to preserve protozoan cysts and trophozoites for the preparation of permanent stained smears (2, 7).

Formalin contains formaldehyde (5 or 10%), which is a toxic carcinogen (1, Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center, University of Arizona College of Pharmacy, [http://www.pharmacy.arizona.edu / centers / tox_center / exp_path / formalde.html]), and LV-PVA contains mercuric chloride, which must be disposed of according to biosafety regulations to limit mercury contamination of the environment (5; Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center, University of Arizona College of Pharmacy). The high cost of disposal of LV-PVA has become a problem in most laboratories within the United States (3, 4). Thus, many laboratories are assessing or adopting non-mercuric chloride- and/or nonformalin-based fixatives. Biomedical supply companies that currently produce one-vial, non-mercuric chloride fixatives state that these new preservatives play the same role as formalin and LV-PVA combined. These one-vial fixatives aim at allowing the laboratory to perform all tests from one vial, with the results presumably being equivalent to or better than those obtained with formalin and LV-PVA. Some of these new fixatives allow concentration procedures that require less centrifugation time or that use staining procedures that are faster and require fewer reagents. We compared five one-vial preservatives (Ecofix, sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin [SAF], STF, Parasafe, and Proto-fix) with 10% formalin and LV-PVA in terms of their suitability in preparation of concentrated wet preparations and permanent stained smears for microscopic examination, ease of use, diagnostic accuracy, and cost. The objective of these findings was to find a fixative that could replace the traditional combination of formalin and mercuric chloride-based PVA (LV-PVA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human fecal specimens were obtained from patients at the Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An initial examination of the specimens was completed in Brazil by the Baermann technique, by the zinc sulfate flotation procedure, and with a modified Kato thick smear. On the basis of these examinations, 20 positive specimens were selected. These specimens were aliquoted within 12 h of passage into seven different fixative vials, coded as a set with identification numbers, and placed in a Ziploc bag. The set of seven fixatives included 10% formalin and LV-PVA (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.), Ecofix (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.), SAF (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.), STF (Streck Laboratories, Inc.), Parasafe (Scientific Device Laboratories, Inc.), and Proto-fix (Alpha Tec Systems, Inc.). When the stool quantity was insufficient, one or more of the seven preservative vials were left out on a rotating basis. A total of seven fixative vials were randomly left out of the specimen sets; these included two vials of 10% formalin, two vials of LV-PVA, one vial of SAF, and two vials of Parasafe. Three Parasafe vials in other sets also were left out of the study due to leakage during transport back to the United States.

Fixed stool specimens arrived in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory within 1 month after initial collection. Accompanying the 20 positive specimens was a data sheet from Brazil which listed the organisms identified in each of the samples. Individual vials of the 20 sample sets were recoded with new identification numbers so that the microscopists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would identify organisms on the basis of morphology and not on the basis of previous knowledge of the initial identification. Since 10% formalin and LV-PVA work together as a set, we considered these two fixatives as “one system,” with formalin being labeled “A” and LV-PVA being labeled “B”. The traditional formalin-ethyl acetate concentration procedure was completed for samples in 10% formalin and STF fixatives (Table 1). The SAF and Parasafe manufacturers recommend a modified formalin-ethyl acetate concentration procedure in which saline is used instead of formalin. The manufacturers of Proto-fix (Alpha Tec Systems, Inc.) and Ecofix (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.) recommend the use of the concentration reagents and procedures specifically made for these fixatives. As recommended by the manufacturers, we used concentration procedures with the following: Consed Sedimentation Reagent (Alpha Tec Systems, Inc.) with Proto-fix and Spincon (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.) with Ecofix. All the concentrates described above were examined as wet mounts. For wet mounts, an area equivalent to the area of a coverslip of 22 by 22 mm was examined by bright-field microscopy at ×100 and ×400 magnifications.

TABLE 1.

Procedures completed with the seven preservativesa

| Fixative | Concentration technique | Permanent stain | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% Formalin | FEA | ||

| LV-PVA | Wheatley's trichrome | ||

| Ecofix | Spincon | Ecostain | |

| SAF | FEA (saline) | Iron hematoxylin | |

| STF | FEA | Wheatley's trichrome | |

| Parasafe | FEA (saline) | Wheatley's trichrome | Conc. PS |

| Proto-fix | Consed | Trichrome-Plus | Conc. PS |

Abbreviations: Conc. PS, concentrated permanent smear; FEA, formalin-ethyl acetate concentration procedure.

Direct permanent smears were prepared with samples from all fixative vials (except 10% formalin, for which its partner LV-PVA vial was used). These smears were stained with the appropriate stains as noted in Table 1: Wheatley's trichrome and Ecostain (both from Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.), Trichrome-Plus (Alpha-Tec Systems, Inc.), and iron hematoxylin (Alexon-Trend, Inc.). Permanent smears (PS) were labeled with an identification number and the date on which they were processed. Smears from concentrated material (CS) of samples fixed in Proto-fix and Parasafe were also stained and labeled with an identification number and the date on which they were processed. Microscopists examined 200 oil-immersion fields using bright-field microscopy at ×1,000 magnification.

Two trained microscopists (“readers”) examined the coded samples blindly and independently. They recorded the species identification, morphologic quality, and parasite density. Morphologic quality was initially graded by using three values: “good” (textbook quality, parasite identification possible, diagnosis of infection possible), “fair” (parasite identification possible, certain morphologic details not visible, diagnosis of infection possible), and “poor” (extreme morphologic distortion or barely recognizable, diagnosis of infection difficult or impossible). If differences in species identification and/or in morphologic quality were found between the two readers, a third microscopist was asked to examine and grade the processed sample blindly and record his or her findings. If this person graded the sample as one of the other microscopists did, the results were accepted and recorded; if this was not the case, the processed sample was shown to a fourth person who examined and graded the sample (with the results being compared and recorded once again). The fourth person's grade always matched one of those of the other three persons. A total of 259 processed samples from 20 positive samples consisting of 18 wet preparations from samples in 10% formalin, 18 permanent stained smears from samples in LV-PVA, 40 concentrated wet mounts and permanent stained smears from samples in Ecofix, 38 concentrated wet mounts and permanent stained smears from samples in SAF, 40 concentrated wet mounts and permanent stained smears from samples in STF, 45 concentrated wet mounts, permanent stained smears, and concentrated stained smears from samples in Parasafe, and 60 concentrated wet mounts, permanent stained smears, and concentrated stained smears from samples in Proto-fix were examined and graded. Equal numbers of processed samples were not used for each fixative due to Parasafe and Proto-fix manufacturers' recommendations to use concentrated material for permanent smears, insufficient stool quantity during the time of collection, and leakage of vials during transport back to the United States.

Because of the difficulty in differentiating between categories and subsequently assigning scores, the decision was made to use only two grading categories. Therefore, for the final analysis, it was decided that the use of only two categories was preferable to the use of three categories. The first two categories of “good” and “fair” were combined and called “satisfactory.” The category of “poor” was then changed to “unsatisfactory.”

RESULTS

Twenty positive specimens had one or more of the following stages of parasites: eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura, larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis, and cysts of Blastocystis hominis, Endolimax nana, Entamoeba coli, Entamoeba histolytica/E. dispar, Iodamoeba buetschlii, and Giardia intestinalis (a few trophozoites of this organism were also found). These samples did not contain Cyclospora cayetanensis, Cryptosporidium parvum, or Isospora belli. Therefore, no data could be collected on these organisms in the seven preservatives.

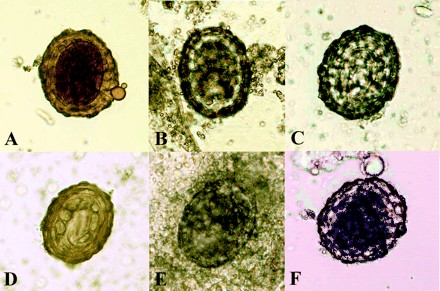

Concentration procedures for samples from six fixatives (with LV-PVA being the exception) were easy to perform and took approximately 10 to 20 min to complete. Wet mounts of samples from four fixatives were clean and easy to visualize. The concentrated material from Parasafe preparations was viscous (Fig. 1), and wet mounts prepared by the Consed procedure were found to be dense red in color, which sometimes obscured elements such as eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides because of blending with background material. The morphology of eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides from concentrated samples in these six preservatives can be found in Fig. 1. Five of these images clearly show morphologic characteristics necessary for identification of Ascaris lumbricoides eggs.

FIG. 1.

Images of Ascaris lumbricoides eggs in concentrated wet mounts preserved in 10% formalin (A), Ecofix (B), SAF (C), STF (D), Parasafe (E), and Proto-fix (F). Magnifications, ×200.

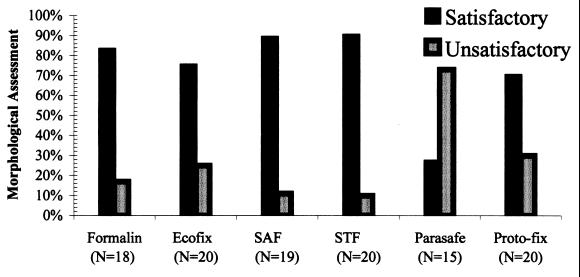

Formalin, Ecofix, SAF, STF, and Proto-fix all scored satisfactory in morphologic quality when used with concentration procedures for wet mounts (Fig. 2). All readers agreed with these results, with few discrepancies being noted.

FIG. 2.

Morphologic quality of fixatives: percentage of concentrated wet mounts of samples from six preservatives that scored satisfactory or unsatisfactory in morphologic assessments.

Few discrepancies in the detection of organisms were noted during examination of the same samples in the various fixatives. The presence of organisms in some wet mounts and not in others was due mainly to rare numbers of organisms per slide; this was most problematic with Strongyloides stercoralis larvae and cysts of Endolimax nana or Blastocystis hominis.

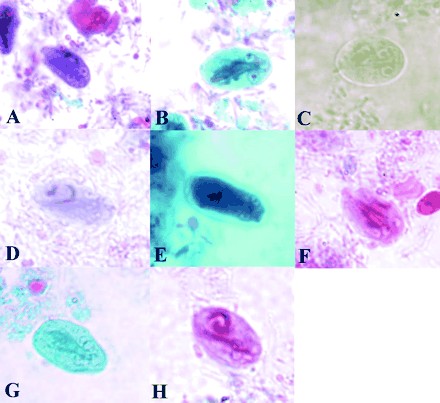

Permanent stained smears had many color ranges that either aided or hindered identification of organisms within the samples. LV-PVA-fixed samples, when stained with trichrome, were red, purple, and blue, while Ecofix-preserved material stained with Ecostain was more of a greenish blue with areas of red. For the other fixatives, material preserved in SAF and stained with iron hematoxylin was brownish-grayish, samples fixed in STF and stained with Wheatley's trichrome were pink or purple, material fixed in Parasafe and stained with trichrome was bluish green, and samples preserved in Proto-fix and stained with Trichrome-Plus were red (as shown in Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Images of Giardia intestinalis cysts and trophozoites in permanent stained smears: LV-PVA stained with Wheatley's trichrome (A), Ecofix stained with Ecostain (B), SAF stained with iron hematoxylin (C), STF stained with Wheatley's trichrome (D), Parasafe stained with Wheatley's trichrome (E), and Proto-fix stained with Trichrome-Plus (F). Concentrated stained smears were Parasafe with Wheatley's trichrome (G) and Proto-fix with Trichrome-Plus (H). Magnifications, ×1,000.

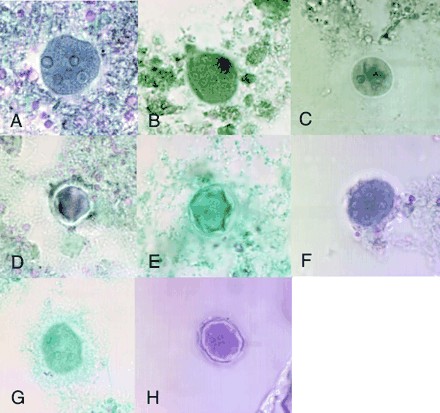

Staining of LV-PVA-fixed samples with Wheatley's trichrome clearly defined the nuclear and cytoplasmic details of the organisms. Material preserved in Ecofix and stained with Ecostain displayed similar morphologic details compared with those for samples preserved in LV-PVA and stained with Wheatley's trichrome. Samples preserved in STF and Parasafe and stained with Wheatley's trichrome did not have the same distinct morphologic characteristics as those preserved in Ecofix or fixed in LV-PVA (Fig. 3 and 4). For samples preserved in Protofix and stained with Trichrome-Plus and in samples preserved in SAF and stained with iron hematoxylin, organisms could not be easily recognized or seen on the smears, and thus, these preservatives did not perform as well as LV-PVA and Ecofix.

FIG. 4.

Images of Entamoeba coli cysts in permanent stained smears: LV-PVA stained with Wheatley's trichrome (A), Ecofix stained with Ecostain (B), SAF stained with iron hematoxylin (C), STF stained with Wheatley's trichrome (D), Parasafe stained with Wheatley's trichrome (E), and Proto-fix stained with Trichrome-Plus (F). Concentrated stained smears were Parasafe with Wheatley's trichrome (G) and Proto-fix with Trichrome-Plus (H). Magnifications, ×1,000.

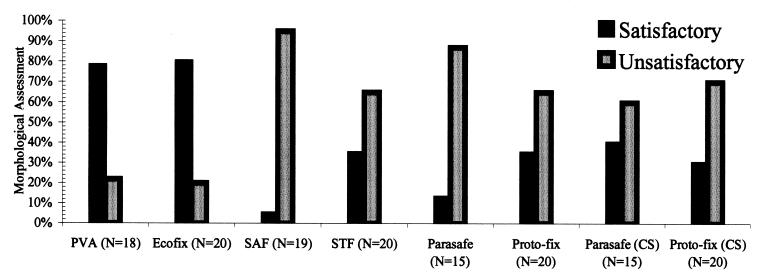

LV-PVA and Ecofix were the only preservatives that scored satisfactory with permanent stained smears (Fig. 5). The range in morphology is illustrated in Fig. 3 and 4. Concentrated permanent stained smears prepared from samples preserved in Parasafe and Proto-fix did not score well, as shown in Fig. 5. The morphologic characteristics of organisms preserved in Parasafe or Proto-fix and then stained were sometimes difficult to observe because the stained sample was blurry, was faint, or lacked the necessary clarity of morphologic characteristics for identification of the organisms.

FIG. 5.

Morphologic quality of fixatives: Percentage of permanent stained smears of samples from six preservatives that scored satisfactory or unsatisfactory in morphologic assessments.

Among the permanent stained smears, there were few missed positive specimens among the specimens that were either unconcentrated or concentrated with various fixatives. As mentioned earlier, organisms were missed primarily due to low parasite density, although the staining quality of the smear and the inability to differentiate between amebae such as Entamoeba coli and Entamoeba histolytica/E. dispar also contributed to some discrepancies.

Readers 1 and 2 graded 129 of the 259 processed fixed samples, identically. Discrepancies between readers 1 and 2 occurred for 130 samples. All samples that were graded differently by readers 1 and 2 were read by reader 3. With only two categories, reader 3 most likely would agree with one of the initial two readers. The 15 permanent and/or concentrated smears for which the parasite identification was questioned were examined by all readers to make a final identification.

DISCUSSION

Fixatives play an important role in the preservation and transport of human fecal specimens and in the accurate diagnosis of parasitic diseases. Formalin and LV-PVA have been trusted preservatives in the past, but with mounting concern over environmental issues and health concerns for laboratorians, alternative fixatives need to be explored. The two objectives of this study were to compare various fixatives (10% formalin and LV-PVA, Ecofix, SAF, STF, Parasafe, and Proto-fix) in terms of diagnostic quality both with wet preparations of concentrates and by techniques for the preparation of permanent stained smears.

We found that all fixatives except Parasafe performed well for the preservation of helminth eggs and protozoa when used with concentration procedures for wet preparations (Fig. 1 and 2). The concentrate of Parasafe-fixed samples was viscous and dense, which made it difficult to see all the morphologic characteristics of the various organisms necessary for identification. Studies by Yang and Scholten (8) found that the SAF fixative works well in concentration procedures but that SAF contains formalin and hence poses the same health concerns as standard 10% formalin. Nace et al. (6) found STF to be an excellent substitute for formalin in concentration techniques. Therefore, acceptable alternatives to traditional 10% formalin for wet preparations exist.

The preparation of permanent stained smears is an important technique associated with routine examination of intestinal protozoa (7). LV-PVA has always been a superior fixative for the preparation of permanent stained smears of protozoan cysts and trophozoites. In our study, LV-PVA proved to be superior. Nonetheless, Ecofix was comparable to LV-PVA in terms of preservation of diagnostic characteristics when the recommended stain was used. Garcia and Shimizu (2) also found this to be true in their study with specimens preserved in Ecofix and stained with either Ecostain or Wheatley's trichrome. They found that specimens fixed in Ecofix and stained with Ecostain had well-defined nuclear detail, with some parasites being easier to identify than the parasites in traditional specimens fixed in LV-PVA.

Direct or concentrated permanent stained smears from various samples preserved in Parasafe, Proto-fix, SAF, and STF were sometimes fuzzy or faint in color, with detailed morphologic characteristics not visible when the smears were stained with appropriate stains. In samples fixed in Parasafe, STF, and sometimes Proto-fix and SAF, amebae (such as Entamoeba histolytica/E. dispar, Entamoeba coli, and Endolimax nana) were the most difficult to identify because of poor preservation. In such samples that did not receive high scores, amebae were distorted or shrunken or the cyst wall was deteriorated; internal structure was poor or nuclei were hard to visualize (these were reported as Entamoeba species). It has been well recognized that good preservation and staining are critical for the identification of amebae, much more so than for the identification of Giardia, for instance. This was again demonstrated in the present study.

Permanent stained smears made from the various fixatives had many color ranges. We found that stains with contrasting colors worked well for the identification of protozoan parasites. Garcia and Shimizu (2) found that the primary difference between Ecostain and Wheatley's trichrome was the color of the organisms. Overall, better performance was obtained for samples preserved in LV-PVA and Ecofix because of preservation of morphology and ease of visualization of parasites on smears stained with contrasting colors.

We were not able to thoroughly evaluate the issue of quantitation between fixatives. However, we noted only a small difference in the number of organisms between aliquots of the same samples in various fixatives. Since a consistent pattern could not be found among the samples in the various fixatives, it does not appear that one fixative performs better or worse for the detection of organisms.

When comparing fixatives in terms of ease of use, Ecofix and Proto-fix had the shortest staining procedures; these two procedures took approximately 15 min, whereas the procedure with trichrome required 55 min and that with iron hematoxylin required 2 h.

Many laboratories today are also concerned with the high cost of preservatives. The approximate cost of each fixative is $1 to $2 per preserved sample. One-vial fixatives cost almost as much as the traditional formalin and LV-PVA Para-Paks. To use new concentration techniques such as Consed or Spincon with samples preserved in Proto-fix or Ecofix, respectively, laboratorians will need to purchase additional concentration kits, which usually include specific vials for use in centrifugation and filters. These kits are relatively expensive, costing anywhere from $1 to $2 per sample, which adds an additional charge to the cost of processing each sample. Therefore, when considering the total cost of sample preservation and processing, the difference in cost between new and traditional fixatives is negligible.

New one-vial fixatives are entering the commercial market. In the present study, several of the seven fixatives (Ecofix, SAF, STF, and Proto-fix) provided the best overall fixative for subsequent parasitological examination with wet preparations. However, all fixatives studied except Ecofix fell short in terms of quality of staining compared to that achieved with LV-PVA.

Continuing evaluations of these new preservatives need to be made by both public health and clinical laboratories to find suitable alternatives to the traditional 10% formalin and PVA. A new one-vial preservative that has characteristics similar to those of the traditional formalin and LV-PVA preservatives would be advantageous in the laboratory not only because of health and disposal issues but also in terms of ease of use, cost, and shorter staining times. Additional work on staining quality for permanent stained smears is needed before a one-vial preservative can replace LV-PVA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chapman B. Fixing to switch. College Am Pathol Today. 1996;11:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia L S, Shimizu R Y. Evaluation of intestinal protozoan morphology in human fecal specimens preserved in Ecofix: comparison of Wheatley's trichrome stain and Ecostain. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1974–1976. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1974-1976.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia L S, Bruckner D A. Diagnostic medical parasitology. 3rd edition. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia L S, Shimizu R Y, Shum A, Bruckner D A. Evaluation of intestinal protozoan morphology in polyvinyl alcohol preservative: comparison of zinc-sulfate and mercuric chloride-based compounds for use in Schaudinn's fixative. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;31:307–310. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.307-310.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melvin D M, Brooke M M. Laboratory procedures for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites. 3rd ed. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1982. publication no. (CDC) 82-8282. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nace E K, Steurer F J, Eberhard M L. Evaluation of Streck tissue fixative, a nonformalin fixative for preservation of stool samples and subsequent parasitologic examination. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4113–4119. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4113-4119.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Procedures for the recovery and identification of parasites from the intestinal tract. Approved guideline M28-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang J, Scholten T. A fixative for intestinal parasites permitting the use of concentration and permanent staining procedures. Am J Clin Pathol. 1977;67:300–304. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/67.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]