Abstract

The cyclins encoded by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and herpesvirus saimiri are homologs of human D-type cyclins. However, when complexed to cdk6, they have several activities that distinguish them from D-type cyclin-cdk6 complexes, including resistance to cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and an enhanced substrate range. We find that viral cyclins interact with and phosphorylate proteins involved in replication initiation. Using mammalian in vitro replication systems, we show that viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes can directly trigger the initiation of DNA synthesis in isolated late-G1-phase nuclei. Viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes share this capacity with cyclin A-cdk2, demonstrating that in addition to functioning as G1-phase cyclin-cdk complexes, they function as S-phase cyclin-cdk complexes.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (also known as human herpesvirus 8) is thought to be the etiologic agent of several multifocal neoplasias (7, 8, 60; reviewed in reference 4). Closely related to KSHV is herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), which causes T-cell lymphomas in non-natural primate hosts (27). The genomes of these two oncogenic members of the gammaherpesvirus family (KSHV and HVS) contain a number of genes that are homologous to known cellular genes, one of which is homologous to D-type cyclin genes (1, 28, 52). Although some KSHV genes have been either implicated in or demonstrated to cause transformation in culture (2, 44), the role of D-type cyclin homologs in viral oncogenicity is as yet undetermined. Because overexpression of D-type cyclins and cyclin E is associated with proliferative disorders and genomic instability (51, 56, 57, 61), the role of viral cyclins in promoting oncogenicity deserves analysis.

DNA tumor viruses deregulate the cell cycle and, in some cases, do so by modulating the cyclin D/p16/pRb signaling pathway, which controls cellular proliferation (reviewed in reference 56). Cellular D-type cyclins are induced upon mitogenic stimulation and are required for the progression of cells from a quiescent state through the restriction point, a juncture in G1 beyond which cells are committed to proceed through the cell cycle even when mitogenic factors are withdrawn (reviewed in reference 51). The retinoblastoma protein (pRb) is sequentially phosphorylated by the G1-phase cyclins: D-type cyclins, which bind cdk's 4 and 6, and cyclin E, which binds cdk2. This inactivates its growth-suppressive functions and facilitates progression into S phase (22, 36). The absence of pRb from cells removes the requirement for D-type cyclins, suggesting that pRb is the major physiologically relevant substrate for progression through G1 phase (35). Additionally, it has recently been shown that a “knock-in” of cyclin E can functionally substitute for cyclin D1 in mice, suggesting that cyclin E is the major downstream target of D-type cyclins (19). Both the virally encoded D-type cyclin homologs present in the genomes of HVS and KSHV, denoted V cyclin and K cyclin, respectively, bind and activate the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases cdk4 and cdk6. The resulting complexes can efficiently phosphorylate pRb (9, 21, 28, 34), the canonical D-type cyclin-cdk substrate. K cyclin-cdk6 complexes are also able to phosphorylate a number of different proteins that are not usually substrates for cyclin D-cdk6, including p27, histone H1, Id-2, and cdc25, but are normally targeted by cyclin E-cdk2 (14, 37). This unique capacity of viral cyclin to change the substrate specificity of cdk6 and phosphorylate many different proteins may prove to be important for viral pathogenesis and/or oncogenicity.

Viral cyclins have the remarkable capacity to evade inhibition by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) (64; reviewed in reference 63). Two families of CKIs (INK4 and Cip/Kip) normally regulate the activity of cdk complexes (reviewed in reference 58). The INK4 proteins specifically bind to D-type cdk's, while the Cip/Kip inhibitors bind to a cyclin-cdk complex and occlude the substrate pocket and catalytic cleft which are required for kinase activity. The resistance of viral cyclin-cdk complexes to inhibition by the INK4 and Cip/Kip proteins suggests that they would represent an unrestrained proliferative signal upon expression in an infected host cell. In support of this idea, expression of K cyclin will induce quiescent cells, where the levels of CKIs are elevated, to transit G1 and enter S (64). Thus, the normal mechanisms to regulate cyclin activity and consequent progression into the cell cycle are subverted by viral cyclins.

Viral cyclin-mediated entry into S phase probably involves the phosphorylation of many targets, including pRb and p27; however, neither of these proteins is directly involved in catalyzing the initiation of DNA replication itself. Even though all of the crucial cdk phosphorylation targets for the initiation of DNA replication have not yet been identified, it is known that cdk2 activity is required for entry into S phase (20, 24, 48, 49). In a screen aimed at discovering proteins that are downstream targets of viral cyclins, we cloned Orc1, a subunit of the origin recognition complex, which suggests a direct role of viral cyclin in S-phase entry. Given the involvement of cellular cyclin-cdk complexes in replication initiation, we determined whether viral cyclin-cdk complexes have the ability to initiate DNA replication directly in cell-free systems, using isolated cell nuclei as templates (30, 32, 62). In these mammalian in vitro replication systems, cyclins E and A have a stimulatory effect (30, 32, 62). The first human in vitro nuclear DNA replication system demonstrated that G1-phase, but not G2-phase, nuclei would initiate replication when coincubated with S-phase cytosol and nuclear extract. Furthermore, the S-phase nuclear extract could be replaced by the addition of exogenous cyclins E and A and their dependent kinases (32). A modified version of this system relies on nuclear cyclin A-cdk2 and cyclin E-cdk2 complexes and another unknown cytosolic initiation activity (30). A second mammalian in vitro replication system has also been described where G1-phase template nuclei were isolated from mouse cells at different time points following release from quiescence (62). When incubated in S-phase cytosol, nuclei from cells later in the transit through G1 phase were competent to initiate replication. This system is sensitive to olomoucine, an inhibitor of cdk2 activity, and this inhibition is relieved by cyclin E-cdk2. In the present study we use both of these mammalian in vitro DNA replication systems to test the ability of viral cyclin-cdk activity to initiate DNA replication. We show that viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes interact with, and phosphorylate, components of the replication machinery and mimic cyclin A-cdk2 complexes to directly drive the initiation of nuclear DNA replication in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two-hybrid screen.

PJ69-4a was cotransformed with a pGBDU vector bearing the full-length HVS cyclin and a human cDNA-GAD library constructed from a B-cell lymphoma (12, 25). Two million transformants were screened by plating on medium selecting for both plasmids and the activation of the HIS3 reporter. 3-Aminotriazole (10 mM) (Sigma) was added to reduce the background due to activation of the histidine reporter by the cyclin bait alone. Potential positive colonies were then rescreened for their ability to activate the lacZ and ADE2 reporters, as well as the plasmid dependence for activation of all three reporters. Library plasmids were isolated, retransformed with the viral cyclin bait plasmid, and then sequenced.

Plasmids.

The pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) mammalian expression constructs encoding double flag epitope-tagged cyclin D1 or K or V cyclins have been previously described (64). The human cyclin E in pRC/CMV was a gift from Ignacio Perez-Roger. The human cyclin A in pCMX was a gift from Jonathan Pines. K and V cyclins were amplified by PCR and subcloned independently into pRsetA (Invitrogen). Constructs for the bacterial expression of viral cyclins were a gift from Charles Swanton. The T7 epitope-tagged Orc1 mammalian expression construct was a gift from Bruce Stillman and has been previously described (18). The human Cdc6 clone was generously provided by John Diffley. The GST-Rb clone was a gift of Gordon Peters. The Orc1 and Cdc6 genes were subcloned into pGEX(KG) (Pharmacia) to create glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins for use as substrates for in vitro kinase reactions. The GenBank accession numbers for viral cyclins used in this study are U93872 for K cyclin and X64346 for V cyclin.

Cell culture, transfection, synchronization, and FACS analysis.

The human osteosarcoma cell line (U2OS) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Helena Biosciences) in a 10% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were cotransfected by the calcium phosphate method, which has been previously described (38), with the appropriate construct and a CD8 marker for transfection. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, stained with anti-CD8 antibodies conjugated to fluorescain isothiocyanate, and fixed in 70% ethanol. DNA was stained with propidium iodide (10 μg/ml). Data were analyzed using bivariate flow cytometry.

HeLa-S3 cells were cultured as monolayers and arrested in late G1 phase by adding 0.5 mM mimosine (Sigma) from a 10 mM stock solution to proliferating cells for 24 h (30, 31). NIH 3T3 cells were grown to confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL). Cells synchronized in G0 by contact inhibition were released into G1 by splitting into fresh medium and harvested 15 or 17 h later (62).

Preparation of nuclei and cell extracts.

Nuclei and cytosolic extracts were prepared by hypotonic treatment followed by Dounce homogenization and centrifugation exactly as described previously (30–32, 62). For NIH 3T3 cells, nuclei were prepared by a slightly gentler version of the standard procedure, using 5 to 10 strokes of the Dounce homogenizer instead of 25 as described previously (32), to better preserve the nuclear membrane.

DNA synthesis reactions and analysis of reaction products.

DNA replication initiation reaction mixtures using human cell nuclei (see Fig. 2) contained the following: HeLa cell cytosolic extract (100 μg of protein, unless indicated otherwise), a buffered mix of ribonucleoside triphosphates and deoxynucleoside triphosphates including biotin-16-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim), and 2 × 105 to 5 × 105 nuclei from mimosine-arrested HeLa cells (30–32). The final reaction volume of 50 μl was adjusted with replication buffer (20 mM potassium HEPES [pH 7.8], 100 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol). The incubation time was 3 h unless indicated otherwise. The Cdk inhibitor roscovitine (Calbiochem) was added to replication reaction mixtures at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. For replication of 17- and 18-h NIH 3T3 G1 nuclei (see Fig. 4 and 5), approximately 5 × 104 nuclei were incubated per 10 μl of 15-h NIH 3T3 G1 cytosolic extract supplemented with nucleotides as above. Reaction mixtures were also supplemented with equivalent levels of Cdk activity (5 × 105 Rb phosphorylation units per 20 μl of reaction mixture) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Incorporation of biotinylated dUTP was visualized as previously described (31), and the percentages of replicating nuclei were determined by fluorescence microscopy. Experiments using cycloheximide were performed at 250 μg of cycloheximide per ml (the concentration routinely used to prepare noncycling Xenopus egg extracts in this laboratory).

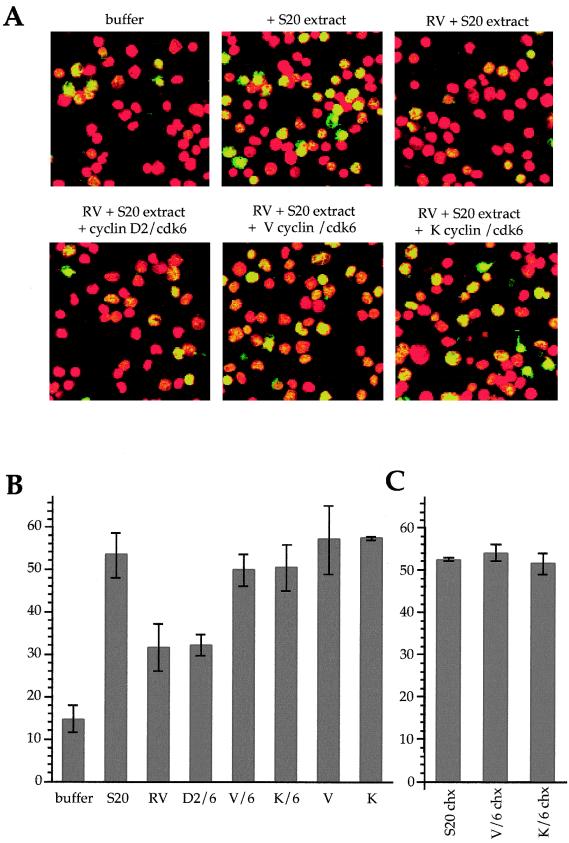

FIG. 2.

Viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes functionally substitute for endogenous cdk2 activity. (A) Representative fields of nuclei replicating in vitro. Nuclei from HeLa cells arrested in late G1 phase by mimosine were incubated in replication buffer (buffer), supplemented with cytosolic extract from proliferating HeLa cells (+S20 extract), 0.5 mM roscovitine (RV), and recombinant cyclin-cdk complexes as indicated. Nuclear DNA was visualized by staining with propidium iodide (red signal), and DNA replicated in vitro was visualized by incorporation of biotin-dUTP and staining with streptavidin-FITC (green signal). Merged images of the two signals are presented, and nuclei replicating in vitro appears in yellow. (B) Quantitation of the percentages of nuclei replicating in these reactions. The percentages of nuclei (500 to 1,000 per reaction) replicating in the presence of the indicated compounds were quantitated from 6 to 10 independent experiments (except for the percentages in lanes labeled V and K, which were analyzed in two independent experiments). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Lanes are as follows: buffer, buffer alone; S20, buffer plus S20 extract; RV, buffer plus S20 plus 0.5 mM roscovitine; then as indicated, cyclin-cdk complexes were added to roscovitine-treated samples. (C) Percentages of nuclei replicating in the presence of cycloheximide (chx). Mean values and standard deviations of two or three independent experiments performed in the presence of cycloheximide and the indicated compounds are as shown in panel B.

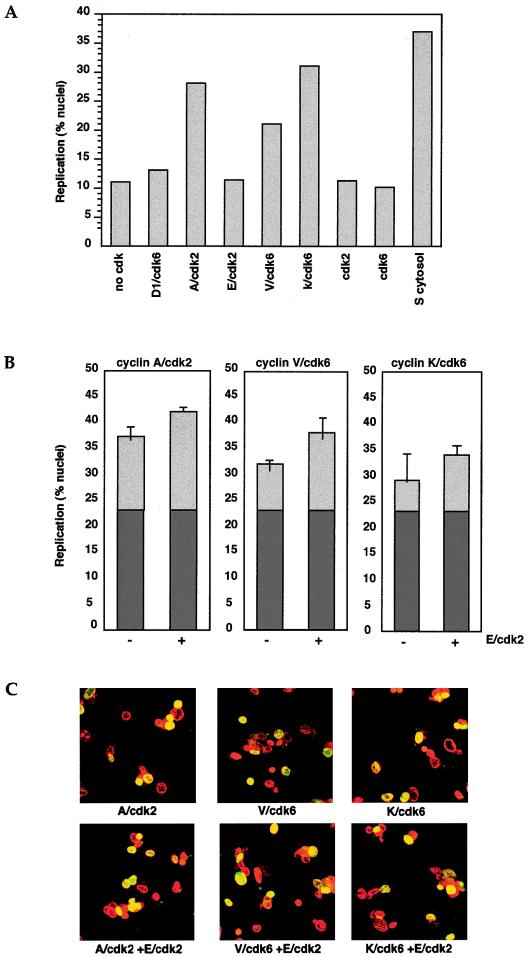

FIG. 4.

Viral cyclin-cdk complexes are sufficient to initiate replication in G1 nuclei when added to G1 cytosol. (A) Nuclei from NIH 3T3 cells isolated 17 h after release from quiescence were incubated in S or G1 cytosol supplemented with equivalent amounts of recombinant cyclin-cdk activity. In this and six other experiments with independent populations of nuclei and purified cyclins or cdk complexes, V cyclin-cdk6 and K cyclin-cdk6 consistently stimulated the proportion of nuclei capable of initiation in vitro. (B) Nuclei from 18-h NIH 3T3 cells were incubated in G1 cytosol supplemented with cyclin A-cdk2, V cyclin-cdk6, or K cyclin-cdk6, in combination with cyclin E-cdk2. In all cases cyclin E-cdk2 had a slight additional effect. (C) Images show representative populations of nuclei. Nuclei were scored using high-magnification fluorescence microscopy to detect the presence or absence of replication foci in 1 to 200 nuclei per sample. Nuclear DNA was visualized by staining with propidium iodide (red signal), and DNA replicated in vitro was visualized by incorporating dUTP-biotin as detected by streptavidin-FITC (green signal). Merged images of the two signals appear in yellow.

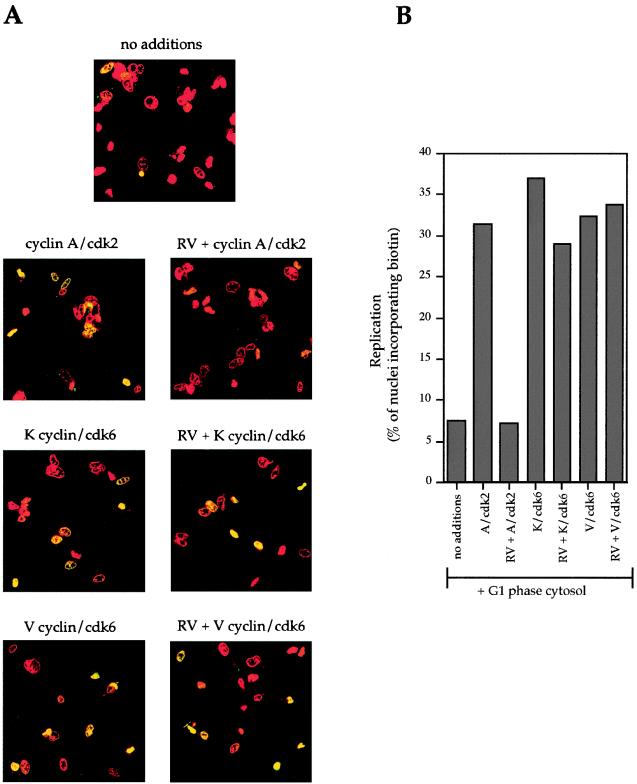

FIG. 5.

Viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes can initiate replication in trans in the presence of roscovitine. Nuclei from NIH 3T3 cells isolated 17 h after release from quiescence were incubated in G1 cytosol and recombinant cyclin-cdk complexes in the presence or absence of roscovitine (RV) as indicated. (A) Panels of nuclei incorporating dUTP-biotin as detected by streptavidin-FITC and viewed by confocal microscopy. (B) Inhibition of endogenous cdk2 activity with roscovitine prevents initiation by cyclin A-cdk2 complexes but not of viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes. A graph of the percentages of nuclei that continued to initiate replication in the presence of roscovitine is given. Data are representative of three separate experiments.

Sf9 infection and preparation of crude extracts.

Sf9 cells (provided by ICRF Cell Production Services) were grown in Grace's insect medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells (3 × 106 to 4 × 106) were seeded into a 60-mm flask and then either singly infected or coinfected with cyclin and cdk partners as previously described (64). Recombinant baculoviruses expressing cyclin D1 and cyclin E were a gift of C. Sherr, those expressing cyclin A and cdk2 were gifts of D. O. Morgan, and that expressing cdk6 was a gift of M. Meyerson. Three days postinfection, cells were collected and lysed in 300 μl of cold lysis buffer (0.1% Tween, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50% glycerol, protease inhibitors). The cells were vortexed for 10 s three times during a 10-min incubation on ice. Debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the cleared lysate was used in kinase assays and in vitro replication assays.

Preparation of purified viral cyclins.

The viral cyclins were amplified by PCR with BamHI and EcoRI linkers and subcloned into pRSETa (Invitrogen). These expression constructs were then transformed into a recA derivative of BL21 (ICRF strain FB810) for large-scale expression. Cyclins were purified via an N-terminal histidine tag over a nickel column (Qiagen). The cyclins were eluted from the column with 100 mM imidazole in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl–2mM dithiothreitol–20% glycerol. Cyclin-cdk complexes were made by mixing equimolar amounts of each subunit and incubating then at 4°C for 1 h. The complexes were further purified by gel filtration over a Superdex 75 column. Kinase activity was confirmed by testing the ability of cyclin-cdk complexes to phosphorylate a GST-Rb (C-terminal) substrate.

Kinase assays.

In vitro kinase assays using lysates from Sf9 cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses were performed essentially as previously described (64). Briefly, phosphorylation reactions were performed in 30-μl volumes using 10 μl of crude extract in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)– 10 mM MgCl2–1 mM dithiothreitol–0.1 mM EGTA and incubated with 5 μg of substrate, 50 μM ATP, and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 30°C, the reactions were stopped by the addition of 2× Laemmli buffer, and the products were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide). The gels were fixed, dried, and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics) for visualization and quantification of the incorporation of radiolabel. Roscovitine was purchased from Calbiochem and made as a 10 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide. The sensitivity of cyclin-cdk complexes to roscovitine was tested at concentrations of 0.5 and 5 μM. Kinase complexes showed similar sensitivities to those reported for cyclin E-cdk2 and cyclin A-cdk2 complexes (40). Kinase assays with purified cyclins were performed with 0.5 mg of purified cyclin-cdk complex in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl–2 mM dithiothreitol–12.5 mM MgCl2–100 μg of bovine serum albumin with 5 μg of purified GST-pRb substrate, 25 μM ATP, and 0.6 μCi of [α-32P]ATP.

Immunoprecipitation and Western analysis.

U2OS cells were transiently transfected with 10 μg of the appropriate mammalian expression constructs. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested by being scraped into 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–150 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA–2.5 mM EGTA–10% glycerol–1 mM dithiothreitol–0.1% Tween 20–10 mM β-glycerophosphate–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were then sonicated for 10 s and centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were subject to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against the flag epitope conjugated to agarose (Affimatrix; Kodak) or antibodies against human cyclin E (Pharmingen 14761C). Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, incubated with antibodies against cdk subunits (anti-cdk2 SC-163; anti-cdk4 SC-260; anti-cdk6 SC-177) (Santa Cruz Biochemicals) or antibodies against anti-human Orc1 (JD32, a gift from J. Diffley) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RESULTS

Viral cyclins interact with the replication protein, Orc1.

The use of the yeast two-hybrid system to identify proteins that interact with cellular cyclins has resulted in the cloning of several genes, including many potential regulators and/or substrates (3, 17, 23, 29, 39, 47, 59). Virus-encoded cyclins have subtle structural alterations that render them resistant to inhibition by CKIs and may also affect substrate selection by viral cyclin-cdk complexes (5, 54, 64). Since the cyclin subunit contributes to substrate selection, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the viral cyclin encoded by the HVS as bait to identify targets that might be important in viral pathogenesis and/or oncogenesis (see Materials and Methods). We identified 15 known genes in this screen, including Orc1, the largest subunit of the origin recognition complex. The other genes will be described elsewhere. The GAD-Orc1 clone that was isolated contained the C-terminal 566 amino acids of Orc1. No other components of the prereplicative complex (pre-RC) were identified in this screen.

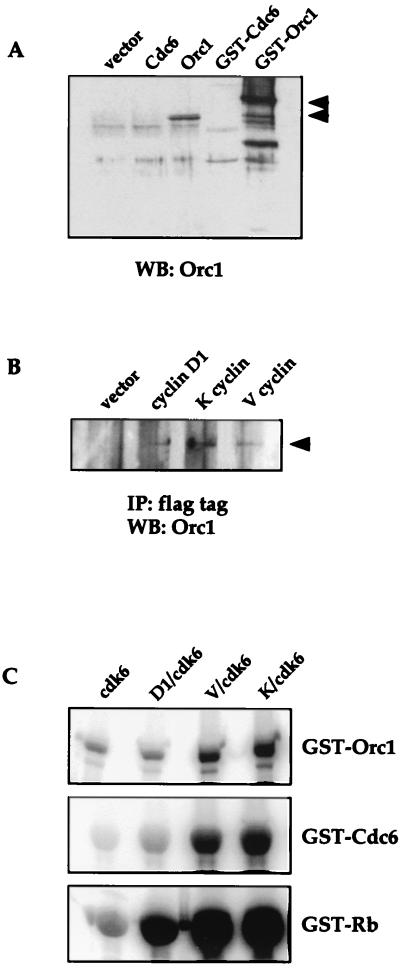

To support the significance of this two-hybrid interaction, we tested the ability of two viral cyclins, K cyclin and V cyclin, to coimmunoprecipitate with Orc1 following their expression in human cells. U2OS osteosarcoma cells were transiently transfected with viral cyclin or cyclin D1 containing an N-terminal flag epitope, and cell lysates were immunopreciptated with antibodies against the flag tag. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the presence of endogenous Orc1. The Orc1 antibody used in these experiments was raised to the C terminus of human Orc1 and recognizes a protein of approximately 105 kDa when a reticulocyte lysate is programmed to translate human Orc1 and a 133-kDa GST-Orc1 fusion protein produced in Escherichia coli and pulled down through glutathione beads. The antibody does not cross-react with human Cdc6, the protein most closely homologous to Orc1, or with a GST-Cdc6 fusion protein (Fig. 1A). In Fig. 1B, viral cyclins and cyclin D1 are shown to coimmunoprecipitate with endogenous Orc1. The interaction between Orc1 and cyclins could be a direct or indirect interaction between cyclins and a multisubunit ORC, although the two-hybrid data would argue in favor of the former. In either case, the above data indicate that viral cyclins interact with a replication protein in vivo.

FIG. 1.

Viral cyclins interact with DNA replication proteins. (A) Western analysis (WB) using JD32 antibody to detect in vitro-transcribed and translated human Orc1 and bacterially expressed GST-Orc1 fusion protein. (B) The indicated cyclins with N-terminal flag epitopes or an empty mammalian expression vector were transiently transfected into U2OS cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-flag antibodies coupled to Sepharose and separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western analysis was performed with anti-Orc1 antibody (JD32). (C) Sf9 lysates from cells programmed to express the indicated cyclin-cdk complexes were used for kinase assays against the indicated GST fusion protein substrates. Kinase reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and 32P incorporation into the substrates was visualized and quantitated on a PhosphorImager.

One of the roles of ORC is to recruit Cdc6, which further assembles a complex of Mcm proteins into a prereplicative complex needed to initiate DNA replication. In yeast, Cdc6 is absent from the pre-RC after the origins fire, although whether this is the case in mammalian cells is unclear (10, 16). The phosphorylation of Cdc6 and Orc1 has been examined and is suggested to be necessary for triggering S phase and/or preventing the reassembly of origins until the next cell cycle. We therefore determined whether cyclin-cdk6 complexes phosphorylate Orc1 and/or Cdc6, both of which are known to be substrates for cyclin E-cdk2 and cyclin A-cdk2 complexes (15, 26, 50, 67). We tested for the ability of viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes and cyclin D1-cdk6 to phosphorylate bacterially expressed Cdc6 and Orc1 fusion proteins in vitro. As seen in Fig. 1C, viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes are able to phosphorylate both Cdc6 and Orc1, demonstrating that the expanded range of cdk6 substrates when complexed to viral cyclins includes these replication proteins. Furthermore, although cyclin D1 interacts with Orc1 in vivo, when complexed to cdk6 it is unable to phosphorylate Orc1 in vitro or initiate DNA replication in vitro (see below).

Viral cyclins can functionally substitute for endogenous S-phase cyclin activity.

Viral cyclin interaction with, and phosphorylation of, replication origin binding proteins led us to speculate about a direct effect of viral cyclin-cdk complexes on the initiation of DNA replication. Since it is difficult to assess a direct effect of viral cyclins on DNA replication in vivo, we addressed this question using two different in vitro replication systems. Both are dependent on cdk2 activity and are modified from the previously published systems (32, 62). Our initial experiments were designed to test for the ability of viral cyclins to substitute functionally for S-phase cyclins to initiate in vitro DNA replication. We used an in vitro nuclear DNA replication system, where template nuclei were isolated from cells arrested in late G1 phase by high concentrations of mimosine (31). These nuclei already contain cyclin A-cdk2 and cyclin E-cdk2, and the initiation of DNA replication in vitro depends on their activity, as well as on a cytosolic extract from interphase cells (30). Typical panels of template nuclei undergoing replication initiation are shown in Fig. 2A, and quantitation is given in Fig. 2B. Only 14% of the mimosine-arrested template nuclei incorporated biotin-dUTP in the absence of cytosolic extract; this low level of replication initiation is due to contaminating S-phase nuclei. In contrast, the percentage of replicating nuclei was increased to 54% when cytosolic extract (S20) was added. We used roscovitine, which competes with ATP for binding to cdk2, to block the endogenous cdk2 activity, reducing the percentage of replicating nuclei to 31%. Viral cyclin-cdk complexes, either purified cyclin-cdk complexes or crude lysates from Sf9 cells coinfected with recombinant baculoviruses expressing either cyclins or cdks, were then assayed for their ability to overcome the roscovitine-mediated inhibition to replication initiation. The addition of viral cyclin, alone or in complexes with cdk6, negated the inhibition of DNA replication initiation by roscovitine, promoting replication in approximately 56% (V or K cyclin alone) and 50% (V or K cyclin-cdk6 complexes) of nuclei (Fig. 2B). The relative levels of kinase activity of cyclin-cdk complexes were assayed using pRb as a substrate, and equivalent amounts of kinase activity were subsequently added to in vitro replication assay mixtures. Both viral cyclins, when titrated into the assay at higher concentrations, showed an inhibitory effect on initiation (data not shown), which has also been previously seen for cyclin E-cdk2 and cyclin A-cdk2 (32). Furthermore, the addition of exogenous cyclins A or E complexed to cdk2 negated the inhibition of initiation imposed by roscovitine (reference 30 and data not shown). In contrast, cdk6 complexed to either cyclin D1 or cyclin D2 failed to overcome the inhibitory effects of roscovitine over a wide (2 orders of magnitude) range of kinase activity (Fig. 2B and data not shown). This indicates that mere addition of cdk activity, even if it is resistant to the effects of roscovitine (see below), is not sufficient to restore DNA replication initiation.

Because viral cyclin-cdk complexes can phosphorylate Rb, which inactivates the E2F transcription factor, it is possible that the upregulation of E2F target genes in vitro could mediate the entry into S phase seen in this system. To address this, we tested the ability of viral cyclins to rescue the roscovitine-mediated block to replication initiation in the presence of cycloheximide. Figure 2C shows that viral cyclins also negate the inhibitory effects of roscovitine in the presence of cycloheximide, arguing that a possible translation of newly transcribed mRNAs in the assay cannot account for the initiation of DNA replication.

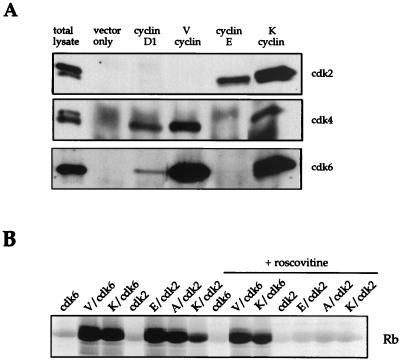

V cyclin binds cdk4 and cdk6, but not cdk2.

It has been previously reported that both viral cyclins bind and activate cdk6, and K cyclin has also been shown to bind cdk2 in vivo (37). Furthermore, in our experiments, the addition of free cyclin subunits stimulated replication initiation, implying that free cyclin subunits are able to complex with endogenous cdks present within the extract. We wanted to determine which cdk subunit is likely to be responsible for mediating this effect. First, we asked whether V cyclin could also bind cdk2. Coimmunoprecipitations from transfected U2OS cells showed that cdk4 and cdk6, but not cdk2, complexed with V cyclin in vivo (Fig. 3A). This specificity of complex formation has been further confirmed in vitro using cyclin and cdk partners expressed in insect cells from baculovirus vectors (C. Swanton, personal communication), suggesting that complex formation with cdk2 is unlikely to account for the stimulatory effect of V cyclin. We conclude, therefore, that V cyclin is stimulating replication initiation via the D-type cyclin kinase partners, cdk4 or cdk6.

FIG. 3.

(A) V cyclin interacts with cdk4 and cdk6 but not cdk2. U2OS cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to cyclins. Western analysis was performed on immunoprecipitates with the indicated anti-cdk antibodies and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection. (B) K cyclin-cdk2 kinase activity is sensitive to roscovitine. Crude extracts from singly infected or coinfected Sf9 cells were used in kinase assays against a purified GST-pRB substrate in the presence or absence of roscovitine. Reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and 32P incorporation was analyzed by a PhosphorImager.

K cyclin-cdk2 is sensitive to roscovitine.

K cyclin could initiate in vitro replication either through cdk4 or cdk6, by imposing a broader substrate range, or through cdk2. As a step toward discriminating between these possibilities, it was important to test whether K cyclin-cdk2 or K cyclin-cdk6 complexes were sensitive to roscovitine. We tested the sensitivity of viral cyclin-mediated kinase activity to roscovitine in in vitro kinase assays using the pRb C terminus as a substrate. At the concentration used in the in vitro kinase assays (0.5 μM), cyclin E-cdk2 and cyclin A-cdk2 complexes showed approximately 50% inhibition while the kinase activity of cdk6 complexed to either cyclin D1 or K cyclin was not affected (data not shown). Furthermore, as seen in Fig. 3B, V cyclin-cdk6 and K cyclin-cdk6 complexes were resistant to a 10-fold-higher concentration of roscovitine (5 μM), which completely inhibited the kinase activities of cyclins E, A, and K complexed to cdk2. These data agree with previously published sensitivity profiles for D-type cyclin-cdk complexes and cyclins E and A complexed to cdk2 (40). Furthermore, these data demonstrate that K cyclin complexed to cdk6 is resistant to inhibition by roscovitine while K cyclin complexed to cdk2 is sensitive. Therefore, viral cyclins do not alter the sensitivity of cdk subunits to roscovitine. In conclusion, these data strongly suggest that K cyclin complexed to cdk4 or cdk6, rather than to cdk2, is likely to be responsible for overcoming the roscovitine-mediated inhibition of replication initiation seen in Fig. 2.

Viral cyclin-cdk complexes, but not cyclin D1-cdk6 complexes, initiate replication in vitro.

Next we wanted to independently confirm an inducing role for viral cyclins in the initiation of DNA replication by using an experimental system that does not depend on chemical inhibitors. This system uses G1-phase nuclei, isolated from NIH 3T3 cells 17 to 18 h after their release from quiescence. Nuclei are incubated in noninitiating G1-phase cytosol (see Materials and Methods) to determine whether stimulation of replication initiation can be triggered by the addition of cyclin/cdk activity. As seen in Fig. 4, there was a background value of 12% replication nuclei when this population of 17-h G1 nuclei were incubated in G1 cytosol. This represents the proportion of nuclei that entered S phase in vivo before isolation. As a positive control for the response to S-phase-promoting activities, G1 nuclei were incubated in S-phase cytosol, which resulted in 37% of these nuclei forming active replication foci. Next we added free cyclins or cyclin complexed to a cdk subunit to the G1 cytosol and nuclei (Fig. 4A and data not shown) and looked for an increase in the number of responsive nuclei. When either V cyclin-cdk6 or K cyclin-cdk6 was added, the incorporation of biotin-dUTP was stimulated. This effect is dependent on the cyclins, since extracts made from Sf9 cells infected with only cdk subunits (cdk2 or cdk6) did not stimulate this system. In repeated experiments with crude extracts as well as purified cyclin-cdk complexes or purified viral cyclins alone, we consistently observed stimulation of replication (Fig. 4A and data not shown). Interestingly, no further increase in the number of replicating nuclei was observed with viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes compared to the addition of viral cyclin alone (data not shown). As in the previous system, this suggests that the viral cyclin was able to complex to endogenous cdk subunits present in the G1-phase cytosol to form active holoenzymes.

We also determined the efficacy of G1 cyclin-cdk complexes (D-type cyclin-cdk6 complexes and cyclin E-cdk2) and an S-phase cyclin-cdk complex (cyclin A-cdk2) in initiating replication in the presence of G1 cytosol. Only cyclin A-cdk2 complexes increased the number of replicating nuclei. Crude extracts from Sf9 cells expressing G1 cyclin-cdk complexes (cyclin D1-cdk6 and cyclin E-cdk2), as well as purified cyclin D2-cdk6 complexes, had little or no stimulatory effect on template nuclei (Fig. 4A and data not shown).

A slight stimulatory role for cyclin E-cdk2 was seen, however, when it was mixed with cyclin A-cdk2 or either of the viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes, suggesting that they cooperate to initiate S phase (Fig. 4B). The histograms show the proportion of cdk-responsive nuclei in a population of 18-h NIH 3T3 G1 nuclei. The proportion of replicating S-phase nuclei in the population is indicated by darker shading, while the lighter shading shows the increase in replicating S-phase nuclei on addition of cyclin-cdk complexes to G1 cytosol. These results agree with a previously reported synergistic effect of cyclins E and A for initiation of replication (32). These data suggest that the endogenous cyclin E levels that may be present in the G1 cytosol are not optimal for initiation. However, even though cyclin E-cdk2 can contribute toward DNA replication, it does not stimulate replication in this assay on its own, arguing for the essential function of cyclin A. Viral cyclin-cdk6-mediated replication initiation is also stimulated by additional cyclin E-cdk2, suggesting that they function like cyclin A-cdk2 in these assays. These data demonstrate that an S-phase cyclin-cdk kinase activity is required to initiate in vitro replication in trans and that individual G1 cyclin-cdk complexes cannot substitute for this activity. Thus, viral cyclin-cdk complexes, but none of the cellular G1-phase cyclin-cdk complexes, (cyclin D1-cdk6, cyclin D2-cdk6, or cyclin E2-cdk2), were able to promote in vitro initiation of DNA synthesis in trans when added to G1 cytosol. Furthermore, they shared the capacity to initiate in vitro DNA replication with cyclin A-cdk2, and their effect on replication initiation was slightly enhanced by cyclin E-cdk2 activity. These data suggest that in this in vitro system, they function in the same way as cyclin A-cdk2, allowing entry into S phase.

Like the mimosine-based initiation system shown in Fig. 2, this G1-derived in vitro system showed no sensitivity to cycloheximide (data not shown). These results support the hypothesis that in a late-G1-phase environment in vitro, viral cyclin-cdk complexes can promote replication initiation by exerting a direct effect on the replication complex.

K cyclin-cdk6 complexes initiate replication in the presence of roscovitine.

We also tested the ability of viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes in G1-phase cytosol to initiate DNA replication in late-G1-phase nuclei in the presence of the cdk2-specific inhibitor roscovitine. As seen in Fig. 5, replication initiation occurred in 37, 32, and 31% of G1 nuclei when K cyclin-cdk6, V cyclin-cdk6, or cyclin A-cdk2 was added to G1 cytosol, respectively. In the presence of roscovitine, however, there was very little effect on replication stimulated by K cyclin-cdk6 or V cyclin-cdk6, while cyclin A-cdk2 stimulation was abolished. This supports our previous conclusion that viral cyclins are able to stimulate in vitro replication via interaction with the cdk6 subunit, since this complex is insensitive to roscovitine.

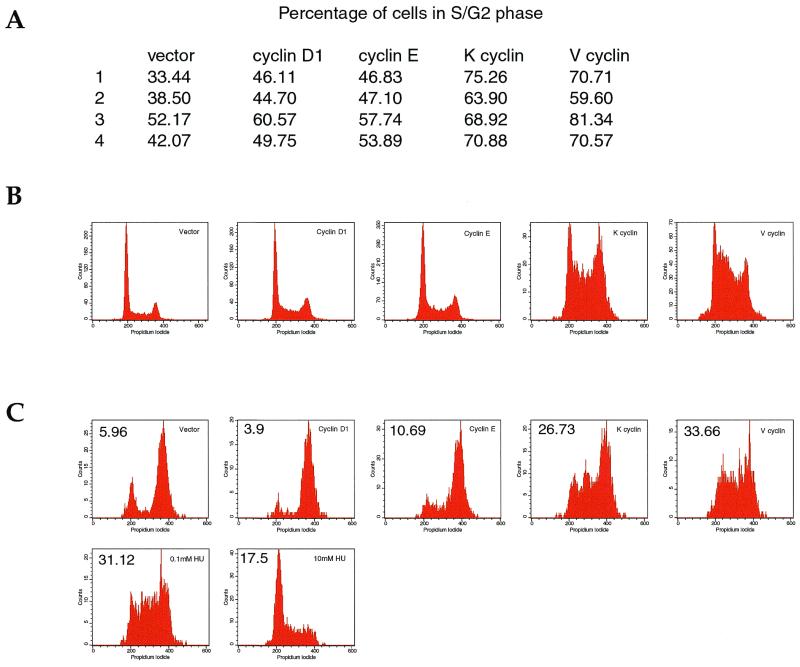

Viral cyclins increase the percentage of cells in S phase.

The above data show that viral cyclin-cdk complexes interact with and phosphorylate replication proteins and have a direct effect on S-phase entry. A stimulatory role for K cyclin in promoting the progression out of quiescence in NIH 3T3 cells has previously been demonstrated (64). We examined the in vivo effect of viral cyclin expression on progression through the cell cycle. The human osteosarcoma cell line U2OS was transiently transfected with viral cyclins and a CD8 marker. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and the DNA content in CD8+ cells was analyzed by FACS. Both viral cyclins consistently and markedly increased the proportion of cells in the S and G2 phases compared to the endogenous G1-phase cyclins (Fig. 6). An increase in the S/G2 population mediated by both K and V cyclins in proliferating NIH 3T3 cells was also seen (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

(A) Viral cyclins increase the proportion of cells in S/G2 phase. The indicated cyclins and a CD8 marker were transiently transfected into U2OS cells. At 48 h post transfection, the cells were harvested by trypsinization and stained with anti-CD8 antibodies conjugated to FITC. The cells were treated with propidium iodide and subjected to FACS analysis. Experiments 1 and 2 show the mean of triplicate samples, while experiments 3 and 4 were done in duplicate. (B) Representative histogram plots of CD8+ transfected cell populations as indicated. (C) Cells were transfected as in panel A, except that 24 h prior to harvesting and FACS analysis, 40 ng of nocodozole per ml was added. Numbers in the upper left hand corner are the percentages of cells in S phase. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

The large proportion of cells in the S and G2 phases caused by overexpression of viral cyclins could represent a rapid transit through G1 phase and/or a slow transit through S phase. To address these possibilities, U2OS cells were transfected as above and, 24 h posttransfection, 40 ng of nocodozole per ml was introduced to block the cells in mitosis. Cells were harvested 24 h later, and the DNA content was analyzed by FACS. As seen in Fig. 6C, U20S cells transfected with cellular cyclins had progressed through S phase and were blocked in mitosis. By contrast, a significant proportion of cells transiently transfected with viral cyclins remained in S phase. A similar cell cycle profile was observed with cells treated with sublethal doses of hydroxyurea (0.1 mM), supporting the view that the viral cyclin-transfected cells were either blocked in mid-S phase or progressing slowly through S phase. Cells treated with high doses of hydroxyurea (10 mM) were blocked early in S phase with a 2N content of DNA. Thus, viral cyclin expression not only induces the initiation of S phase but also prolongs its duration, a situation that may be conducive to viral DNA replication.

DISCUSSION

Although the role of viral cyclins in gammaherpesvirus-mediated oncogenesis is still under investigation, they appear to use multiple direct and indirect mechanisms to alter the regulation of the cell cycle and promote entry into S phase. Their ability to phosphorylate and inactivate key proteins that restrict progression through G1 phase (pRb and p27) suggests that the viral cyclins are likely to be important for keeping infected cells in cycle. Additionally, subsequent transcriptional upregulation of cyclin A will further increase cyclin-cdk2-dependent activity, which is required for S-phase entry (13, 14, 21, 28, 34, 37). Finally, there are many potential indirect transcriptional effects due to E2F release from Rb, which could enhance S-phase entry (increased expression of cyclin E and various DNA synthesis genes).

To identify viral cyclin-interacting proteins that might prove to be important in oncogenesis or viral pathogenesis, we performed a two-hybrid screen with a viral cyclin and identified Orc1, a component of the replication machinery, as an interacting protein. Orc1 interacts with Cdc6, which then recruits a complex of Mcm proteins to form prereplicative complexes (pre-RC) at origins of replication (reviewed in reference 11). The GAD-Orc1 clone isolated in the screen contained the C-terminal ATPase domain, and it is this region of Orc1 that is most homologous to Cdc6. In support of the two-hybrid screen findings, we showed that both K and V cyclins coimmunoprecipitate with Orc1 in vivo and, furthermore, phosphorylate both Orc1 and Cdc6 in vitro. This contrasts with the situation for cyclin D1, which was able to interact with Orc1 but was unable to phosphorylate Orc1 or Cdc6 in vitro or to initiate in vitro replication (see below).

While a number of studies have shown that cdk2 activity is required for S-phase entry, the nature of the crucial target proteins and their phosphorylation sites has not yet been determined (20, 24, 48, 49). The best-characterized candidate replication proteins are Orc1 and Cdc6, and their phosphorylation is proposed to be important for firing origins during S phase and/or preventing origin pre-RC reassembly. A hyperphosphorylated state of human and Xenopus Orc1 correlates with its decreased association with chromatin during mitosis (15, 66), and only during early G1 does mammalian Orc1 rebind chromatin, allowing ORC assembly (45). Furthermore, many studies have correlated the phosphorylation of Cdc6 with its degradation as well as its export from the nucleus (10, 16, 26, 50, 53, 65, 68). It has been previously shown that both viral cyclins robustly activate cdk6 and extend its substrate range to include proteins phosphorylated by cyclin E-cdk2, such as p27 and Id2 (9, 14, 21, 28, 34, 37). Our data indicate that replication proteins are among the expanded repertoire of substrates that cdk6 is able to phosphorylate when complexed to viral cyclins but not to an endogenous D-type cyclin.

The above data raised the intriguing possibility that viral cyclin-cdk complexes participate directly at replication origins to promote S-phase entry. To test this hypothesis and to simplify events surrounding S-phase entry, we examined the capacity of viral cyclins to directly initiate DNA replication in vitro. We used two distinct human in vitro replication systems that allowed us to compare viral cyclins with the endogenous cyclins to promote initiation. In the first system, initiation is dependent on cdk2 activity, which is present in cis in template nuclei from late-G1 cells, and on a soluble cytosolic initiation factor (30, 32). We inhibited the endogenous cdk activity by using roscovitine and showed that viral cyclin-cdk complexes can substitute for the endogenous cdk2 activity, complementing the “knockout” of an essential S-phase-promoting activity. Viral cyclin-cdk activity, like exogenously added cyclin E-cdk2 or cyclin A-cdk2 activity, can overcome this block to replication initiation. Strikingly, D-type cyclins complexed to cdk6 are unable to stimulate initiation, demonstrating the specificity of viral cyclin-cdk6 activity in this assay. Thus, when complexed to viral cyclins, but not to D-type cyclins, cdk6 can promote replication initiation.

In the G1-derived system, we assessed which cyclin-cdk complexes, when delivered in trans to a late-G1 in vitro environment (nuclei and cytosol), are sufficient to promote the initiation of DNA replication. Here, the addition of neither the D-type cyclin-cdk6 complex nor the cyclin E-cdk2 complex is sufficient to stimulate replication initiation. A stimulatory effect for cyclin E-cdk2 is seen only in combination with cyclin A-cdk2 complexes, demonstrating the dependence of this system on cyclin A-cdk2 activity for replication initiation. The addition of either viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes or cyclin A-cdk2 complexes triggers the initiation of DNA synthesis, supporting the idea that viral cyclin-cdk6 activity is functionally equivalent to cyclin A-cdk2 activity in this assay. We demonstrate the requirement for cdk2 activity in this system by using roscovitine, which inhibits replication initiation mediated by cyclin A-cdk2 complexes. Convincingly, viral cyclin-cdk6 activity alone is sufficient to promote DNA replication even in the presence of roscovitine. These data argue strongly for the capacity of viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes to independently promote DNA replication, which is normally a cdk2-mediated reaction. Since cdk2 activity is normally required for the initiation of S phase, these data indicate that the broadened substrate range of viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes includes targets that initiate DNA replication.

One potential target for phosphorylation and degradation within the in vitro replication systems is p27, which is a substrate for K cyclin-cdk6 (14, 37). The phosphorylation of p27 results in its degradation via ubiquitination (6, 43, 55). Therefore, one mechanism by which K cyclin could stimulate replication is by phosphorylating p27, thereby releasing endogenous cyclin E-cdk2 or A-cdk2 activity from inhibition, which could then stimulate initiation. However, even in the presence of roscovitine, viral cyclin-cdk complexes can stimulate initiation, arguing that release of endogenous cdk2 activity from inhibition by p27 is not the underlying mechanism that promotes initiation.

The upregulation of the transcription factor E2F has also been demonstrated to promote S-phase entry, and many E2F target genes are involved in S-phase progression, including proliferating-cell nuclear antigen, ribonucleotide reductase, cyclin A, DNA polymerase α, and thymidine synthase (reviewed in reference 46). Using cell-free in vitro replication systems, we can eliminate any indirect subsequent downstream transcriptional effects, which is not possible when doing these experiments in vivo. We addressed the possibility that de novo expression of E2F target genes was mediating viral cyclin-cdk-induced DNA initiation in the in vitro systems by the addition of cycloheximide to block translation. Our data, showing little or no effect of cycloheximide on the initiation of DNA replication, argue that translation is unlikely to be crucial for the initiation of DNA replication in these systems.

The data presented in this report argue that in addition to their previously reported cyclin D- and E-like kinase activities, viral cyclins have a distinct S-phase-promoting activity that acts directly to stimulate the initiation of DNA replication and mimics cyclin A-like activity. Viral cyclins interact with Orc1 in vivo, suggesting that they are present at origins. Furthermore, our in vitro data indicate that the range of substrates for viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes includes targets involved in the initiation of DNA synthesis. Viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes function as cyclinA-cdk2 complexes to stimulate in vitro replication, while cyclin E-cdk2 is unable to catalyze this reaction. This is the first demonstration of their ability to function exclusively as an S-phase, rather than a G1 phase, kinase, although we have not shown which phosphorylation event is responsible for triggering the initiation of DNA replication itself. Furthermore, we demonstrate that transient overexpression of viral cyclins markedly increases the proportion of cells in S/G2 phase in proliferating cells, and this effect is likely to be due to a delay in progression. One possible mechanism to explain this increase is that viral cyclin-cdk6 complexes represent a sustained cdk2-like activity during the latter part of the cell cycle. In normal cells, cdk2 activity is downregulated so that the cells can exit these phases of the cell cycle and enter mitosis. At present, the mechanisms that regulate viral cyclin stability are unknown. This could reflect a viral mechanism to keep infected cells in a host cell environment that is conducive to viral DNA replication.

KSHV and HVS infect lymphoid cells, where cdk6 is the predominant kinase associated with D-type cyclins (41, 42). Viral cyclins bind and strongly activate cdk6 and extend its substrate repertoire (9, 14, 21, 28, 34, 37; reviewed in reference 33). Therefore, these two oncogenic herpesviruses encode viral D-type cyclin homologs that, on binding to a single cdk subunit, execute the functions of three separate cyclin-cdk complexes, encompassing exit from G0 (cyclin D-cdk6) through G1 (cyclin E-cdk2) to entry into S (cyclin A-cdk2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank several people for generously providing reagents used in these experiments: E. Laue, P. Knowles, and N. McDonald for purified viral cyclins and cdk subunits; R. Peat for Sf9 cells; I. Perez-Roger, J. Pines, B. Stillman, J. Diffley, and C. Swanton for expression constructs; J. Diffley for anti-Orc1 antibodies; and D. Morgan, M. Meyerson, and C. Sherr for recombinant baculoviruses. We thank D. Davies for FACS analysis and D. Mann, P. Pereira, and J. Pines for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the ICRF, the CRC, the Royal Society, and the Louis Jeantet Foundation.

H. Laman, D. Coverley, and T. Krude contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht J C, Nicholas J, Biller D, Cameron K R, Biesinger B, Newman C, Wittmann S, Craxton M A, Coleman H, Fleckenstein B, Honess R W. Primary structure of the herpesvirus saimiri genome. J Virol. 1992;66:5047–5058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5047-5058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Raaka E G, Gutkind J S, Asch A S, Cesarman E, Gershengorn M C, Mesri E A. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonetto F, Fanciulli M, Battista T, De Luca A, Russo P, Bruno T, De Angelis R, Di Padova M, Giordano A, Felsani A, Paggi M G. Interaction between the pRb2/p130 C-terminal domain and the N-terminal portion of cyclin D3. J Cell Biochem. 1999;75:698–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19991215)75:4<698::aid-jcb15>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boshoff C, Weiss R A. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;75:57–86. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Card G L, Knowles P, Laman H, Jones N, McDonald N Q. Crystal structure of a γ-herpesvirus cyclin-cdk complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:1–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrano A C, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore P S, Said J W, Knowles D M. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin M S, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles D M, Moore P S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Y, Moore P S, Talbot S J, Boshoff C H, Zarkowska T, Godden K, Paterson H, Weiss R A, Mittnacht S. Cyclin encoded by KS herpesvirus. Nature. 1996;382:410. doi: 10.1038/382410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coverley D, Pelizon C, Trewick S, Laskey R A. Chromatin-bound Cdc6 persists in S and G(2) phases in human cells, while soluble Cdc6 is destroyed in a cyclin A-cdk2 dependent process. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1929–1938. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diffley J F. Replication control: choreographing replication origins. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R771–R773. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen P L, Yeh S H, Yang Y, Kilburn A E, Lee W H, Elledge S J. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duro D, Schulze A, Vogt B, Bartek J, Mittnacht S, Jansen D P. Activation of cyclin A gene expression by the cyclin encoded by human herpesvirus-8. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:549–555. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis M, Chew Y P, Fallis L, Freddersdorf S, Boshoff C, Weiss R A, Lu X, Mittnacht S. Degradation of p27(Kip) cdk inhibitor triggered by Kaposi's sarcoma virus cyclin-cdk6 complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:644–653. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Findeisen M, El-Denary M, Kapitza T, Graf R, Strausfeld U. Cyclin A-dependent kinase activity affects chromatin binding of ORC, cdc6, and MCM in egg extracts of xenopus laevis. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:415–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujita M, Yamada C, Goto H, Yokoyama N, Kuzushima K, Inagaki M, Tsurumi T. Cell cycle regulation of human CDC6 protein. Intracellular localization, interaction with the human Mcm complex, and Cdc2 kinase-mediated hyperphosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25927–25932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funakoshi M, Geley S, Hunt T, Nishimoto T, Kobayashi H. Identification of XDRP1; a Xenopus protein related to yeast Dsk2p binds to the N-terminus of cyclin A and inhibits its degradation. EMBO J. 1999;18:5009–5018. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.5009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin K A, Hidaka M, Stillman B. Conserved initiator proteins in eukaryotes. Science. 1995;270:1667–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng Y, Whoriskey W, Park M Y, Bronson R T, Medema R H, Li T, Weinberg R A, Sicinski P. Rescue of cyclin D1 deficiency by knockin cyclin E. Cell. 1999;97:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb N J. Cyclin A is required for the onset of DNA replication in mammalian fibroblasts. Cell. 1991;67:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godden-Kent D, Talbot S J, Boshoff C, Chang Y, Moore P, Weiss R A, Mittnacht S. The cyclin encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stimulates cdk6 to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein and histone H1. J Virol. 1997;71:4193–4198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4193-4198.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harbour J W, Luo R X, Dei Santi A, Postigo A A, Dean D C. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirai H, Sherr C J. Interaction of D-type cyclins with a novel myb-like transcription factor, DMP1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6457–6467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua X H, Newport J. Identification of a preinitiation step in DNA replication that is independent of origin recognition complex and cdc6, but dependent on cdk2. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:271–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James P, Halladay J, Craig E A. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang W, Wells N J, Hunter T. Multistep regulation of DNA replication by Cdk phosphorylation of HsCdc6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6193–6198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung J U, Choi J K, Ensser A, Biesinger B. Herpesvirus saimiri as a model for gammaherpesvirus oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:231–239. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung J U, Stager M, Desrosiers R C. Virus-encoded cyclin. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7235–7244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong M, Barnes E A, Ollendorff V, Donoghue D J. Cyclin F regulates the nuclear localization of cyclin B1 through a cyclin-cyclin interaction. EMBO J. 2000;19:1378–1388. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krude T. Initiation of human DNA replication in vitro using nuclei from cells arrested at an initiation-competent state. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13699–13707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krude T. Mimosine arrests proliferating human cells before onset of DNA replication in a dose-dependent manner. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:148–159. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krude T, Jackman M, Pines J, Laskey R A. Cyclin/Cdk-dependent initiation of DNA replication in a human cell-free system. Cell. 1997;88:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laman H, Mann D J, Jones N C. Viral-encoded cyclins. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, Lee H, Yoon D W, Albrecht J C, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Jung J U. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a functional cyclin. J Virol. 1997;71:1984–1991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1984-1991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lukas J, Bartkova J, Rohde M, Strauss M, Bartek J. Cyclin D1 is dispensable for G1 control in retinoblastoma gene-deficient cells independently of cdk4 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2600–2611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundberg A S, Weinberg R A. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:753–761. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann D J, Child E S, Swanton C, Laman H, Jones N. Modulation of p27(Kip1) levels by the cyclin encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. EMBO J. 1999;18:654–663. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mann D J, Jones N. E2F-1 but not E2F-4 can overcome p16-induced cell cycle arrest. Curr Biol. 1996;6:474–483. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Measday V, McBride H, Moffat J, Stillman D, Andrews B. Interactions between Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase complexes and the Swi5 transcription factor in budding yeast. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:825–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meijer L, Borgne A, Mulner O, Chong J P, Blow J J, Inagaki N, Inagaki M, Delcros J G, Moulinoux J P. Biochemical and cellular effects of roscovitine, a potent and selective inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases cdc2, cdk2 and cdk5. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyerson M, Enders G H, Wu C L, Su L K, Gorka C, Nelson C, Harlow E, Tsai L H. A family of human cdc2-related protein kinases. EMBO J. 1992;11:2909–2917. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyerson M, Harlow E. Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2077–2086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montagnoli A, Fiore F, Eytan E, Carrano A C, Draetta G F, Hershko A, Pagano M. Ubiquitination of p27 is regulated by Cdk-dependent phosphorylation and trimeric complex formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1181–1189. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muralidhar S, Pumfery A M, Hassani M, Sadaie M R, Kishishita M, Brady J N, Doniger J, Medveczky P, Rosenthal L J. Identification of kaposin (open reading frame K12) as a human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) transforming gene. J Virol. 1998;72:4980–4988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4980-4988.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natale D A, Li C J, Sun W H, DePamphilis M L. Selective instability of Orcl protein accounts for the absence of functional origin recognition complexes during the M-G(1) transition in mammals. EMBO J. 2000;19:2728–2738. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohtani K. Implication of transcription factor E2F in regulation of DNA replication. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D793–D804. doi: 10.2741/ohtani. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohtoshi A, Maeda T, Higashi H, Ashizawa S, Hatakeyama M. Human p55 (CDC)/Cdc20 associates with cyclin A and is phosphorylated by the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:530–534. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtsubo M, Theodoras A M, Schumacher J, Roberts J M, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–2624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersen B O, Lukas J, Sorensen C S, Bartek J, Helin K. Phosphorylation of mammalian CDC6 by cyclin A/CDK2 regulates its subcellular localization. EMBO J. 1999;18:396–410. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reed S I. Control of the G1/S transition. Cancer Surv. 1997;29:7–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russo J J, Bohenzky R A, Chien M C, Chen J, Yan M, Maddalena D, Parry J P, Peruzzi D, Edelman I S, Chang Y, Moore P S. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14862–14867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saha P, Chen J, Thome K C, Lawlis S J, Hou Z H, Hendricks M, Parvin J D, Dutta A. Human CDC6/Cdc18 associates with Orcl and cyclin-cdk and is selectively eliminated from the nucleus at the onset of S phase. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2758–2767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulze-Gahmen U, Jung J U, Kim S H. Crystal structure of a viral cyclin, a positive regulator of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Structure. 1999;7:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheaff R J, Groudine M, Gordon M, Roberts J M, Clurman B E. Cyclin E-CDK2 is a regulator of p27Kipl. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1464–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sherr C J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sherr C J. D-type cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sherr C J, Roberts J M. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singer J D, Gurian-West M, Clurman B, Roberts J M. Cullin-3 targets cyclin E for ubiquitination and controls S phase in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2375–2387. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals H D, Babinet P, d'Agay M F, Clauvel J P, Raphael M, Degos L, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spruck C H, Won K A, Reed S I. Deregulated cyclin E induces chromosome instability. Nature. 1999;401:297–300. doi: 10.1038/45836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stoeber K, Mills A D, Kubota Y, Krude T, Romanowski P, Marheineke K, Laskey R A, Williams G H. Cdc6 protein causes premature entry into S phase in a mammalian cell-free system. EMBO J. 1998;17:7219–7229. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swanton C, Card G L, Mann D, McDonald N, Jones N. Overcoming inhibitions: subversion of CKI function by viral cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swanton C, Mann D J, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Peters G, Jones N. Herpes viral cyclin/Cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by CDK inhibitor proteins. Nature. 1997;390:184–187. doi: 10.1038/36606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takei Y, Yamamoto K, Tsujimoto G. Identification of the sequence responsible for the nuclear localization of human Cdc6. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:292–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tatsumi Y, Tsurimoto T, Shirahige K, Yoshikawa H, Obuse C. Association of human origin recognition complex 1 with chromatin DNA and nuclease-resistant nuclear structures. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5904–5910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolf D A, Wu D, McKeon F. Disruption of re-replication control by overexpression of human ORC1 in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32503–32506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan Z, DeGregori J, Shohet R, Leone G, Stillman B, Nevins J R, Williams R S. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]