Abstract

Cancer is a multifactorial disease with a convoluted genesis and progression. The emergence of multidrug resistance to presently be offered drug and relapse is by far, the most critical concern to tackle this deteriorating disease. Henceforth, there is undeniably an inflated necessity for safe, promising, and less harmful new anticancer drugs. Natural compounds from various sources like plants, animals, and microorganisms have occupied a center stage in drug discovery due to their tremendous chemical diversity and potential as therapeutic agents. Endophytic microbes are symbiotically associated with plants and have been proven to produce novel or analogues of host bioactive metabolites exhibiting a variety of biological activities including anticancer activity. This review emphasizes on structurally diverse unprecedented anticancer natural compounds that have been reported exclusively from endophytic fungi from 2016 to 2020. It covers chemical nature of metabolites, its fungal source associated with terrestrial, as well as marine plants and anticancer activity based on their cytotoxicity profile against various cancer cell lines. Many of these fungal metabolites with promising anticancer activity can be used as lead molecules for in silico experiments and deserve special attention from scientists for further in vitro and clinical research.

Keywords: Endophytes, Antitumor, Novel fungal metabolites, Cytotoxicity, Natural compounds

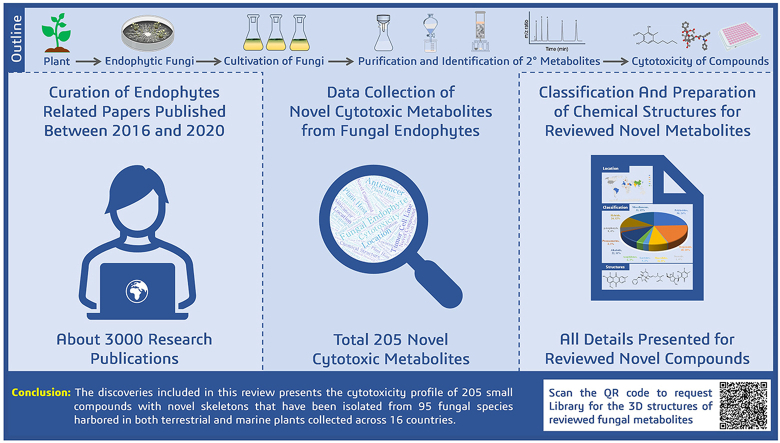

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Endophytic fungi are the gold mine for natural chemotherapeutic agents.

-

•

The present study sheds light on novel cytotoxic fungal metabolites.

-

•

Future aspects of endophytic metabolites have been precisely discussed.

-

•

Library for the 3D structures of reviewed compounds will be provided on request.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a global health problem that affects all population, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, wealth, or socioeconomic status and therefore, it is undeniably the biggest obstacle in the twenty-first century that is jeopardizing medical system and research community. Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about 10 million deaths per year and this number is still rising (GLOBOCAN, 2020). A variety of clinical methods, including surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation are the key treatment for cancer (Subramaniam et al., 2019). Currently present chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer treatment offer temporary relief to the patients and extend their longevity, but with this come other disadvantages which includes side effects, lack of selectivity and overpriced that not only impairs the quality of life but is also unaffordable by millions of patients living in developing nations (Reis-Mendes et al., 2018). Additionally, the emergence of multidrug resistance and relapse of malignancy is by far, the most critical concern in the treatment of this multifactorial condition with a convoluted genesis and progression (Cree and Charlton, 2017; Patel et al., 2018). To tackle this deteriorating disease, there is certainly an unmet need for new promising, safe, and less harmful medicines produced from natural compounds. Research findings suggest that phytochemicals possess antitumor ability, and many of them are currently being used to treat this high-profile disease (Patel et al., 2018; Bhadresha et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2015). Despite the fact that phytochemicals are recognized as the most significant source of potential drugs, their use in drug research has recently seen a decline in interest due to some remarkable challenges with the plant as a drug molecule source, such as its unusual habitat, slow growth rate, limited yield and non-reproducibility of the desired phytochemicals and an unwavering threat by the civilization (Kala et al., 2006; Garcia-Oliveira et al., 2021). On the other side, microorganisms have sparked a lot more interest as a source of therapeutic agents because of their abundance, high biodiversity, and unique scaffold of produced bioactive components. They are often rudimentary to culture in a fermenter under controlled environments, and consistently deliver the desired molecules. (Abdel-Razek et al., 2020).

The great discovery of the billion-dollar chemotherapeutic drug Paclitaxel originally known to be produced only by plant Taxus longifolia (discovered in 1971), was later identified to be produced by an endophytic fungus Taxomyces andreanae (discovered in 1993), from the same plant, Taxus longifolia has led scientists to appreciate plants as reservoirs for an infinite range of microorganisms, normally alluded as the endophytes (Stierle et al., 1995). Endophytes are microorganisms that live within plant tissues with mutualistic association for at least part of their life cycle without causing any apparent disease manifestation (Arora et al., 2016). Some endophytes have evolved the ability to synthesize bioactive compounds in a de novo manner that are identical or related to those produced by their host plants during mutualistic association (Jia et al., 2016). For instance, endophytic fungi isolated from Taxus chinensis var. mairei, Podophyllum hexandrum, Camptotheca acuminata and Catharanthus roseus can produce anticancer drug taxol, podophyllotoxin, camptothecin and vincristine, respectively (Palem et al., 2015; Nadeem, 2012; Qiao et al., 2017; Ran et al., 2017). Moreover, these endophytes also produce novel secondary metabolites with unprecedented scaffolds (Pang et al., 2018) and sometimes hybrid chemical skeletons (Chen et al., 2017). The most widely found endophyte fungal species belong to the genus of Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Penicillium, Fusarium and Pestalotiopsis. Research on endophytic fungi have evinced that, they are an auspicious resource of bioactive compounds and to access this valuable source, the diversity of endophytic fungi and their species richness in different parts of world has been explored.

Large number of secondary metabolites, especially from fungal endophytes are extracted, isolated, and characterized, of which, some of these have been discussed in earlier reviews in detail (Bedi et al., 2018a; Deshmukh et al., 2014; Kharwar et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2008). Most of these fungal metabolites are bioactive and classified under various chemical classes like, alkaloids, terpenoids, polyketides, flavonoids, steroids, lactones, lignans, depsipeptides, quinones, etc. In the past three decades, around 180 natural molecules with significant cytotoxicity towards selected tumor cell lines are reported from the endophytic fungi harbored in various plants (Bedi et al., 2018a; Kharwar et al., 2011). This review summarizes 205 novel compounds produced by terrestrial and marine plant-associated endophytic fungi from 2016 to 2020, including detailed chemical structures, structural type classifications, and cytotoxicity towards particular cancer cell lines.

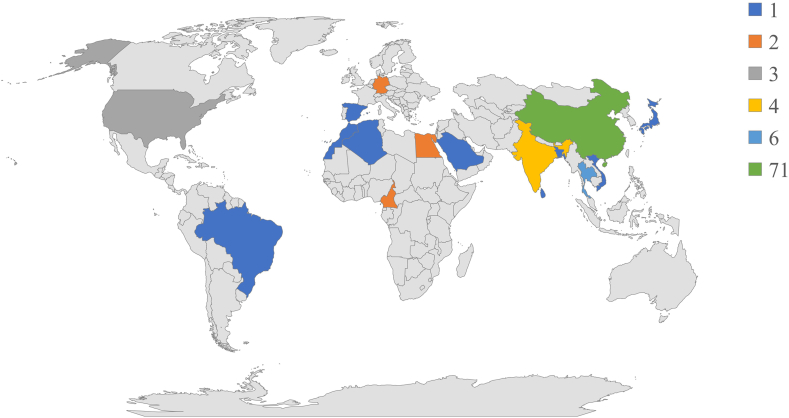

2. Cytotoxic secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi

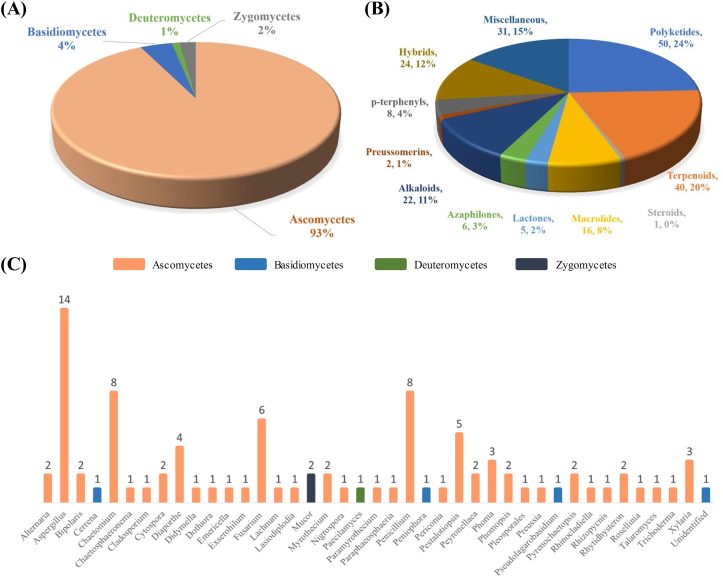

Endophytic fungi are valuable source of natural bioactive compounds in drug discovery and have a wide range of medical applications. Secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi have diverse biological activities, such as cytotoxic, antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, phytotoxic, antimalarial, antialgae, antimigratory, and pro-apoptotic activity. In past thirty years, researchers have been driven for the use of novel and promising cytotoxic compounds in pharmaceuticals. Herein, 205 new natural compounds synthesized by terrestrial as well as marine plant associated 95 endophytic fungi from 4 phyla and 41 genera, collected from 16 countries during the period of 2016–2020 are described (Fig. 1). In the subsequent sections, we discuss about the cytotoxic profile of compounds which are majorly classified as polyketides, terpenoids, sterols, macrolides, lactones, azaphilones, alkaloids, preussomerins, p-terphenyls, hybrid structures and miscellaneous compounds based on their chemical nature. List of secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi, with their plant host and cytotoxic activities towards specific tumor cell lines are provided in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

(A) Proportions of endophytic fungi belonging to various phyla, (B) total number and percentage of structural varieties of novel cytotoxic compounds from endophytic fungi, and (C) the quantity of endophytic fungi researched in each genus.

Table 1.

Novel cytotoxic compounds of the fungal endophytes reported during 2016–2020.

| Chemical nature | Secondary metabolite | Cell lines | Activity (IC50) | Endophytic fungi | Host plant (T/M)b | Location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromones | Botryochromone (1) | KB | 43 μg/mL | Botryosphaeriaceae family (unidentified strain BCC 54265) | Polygonum odoratum(T) | Thailand | Isaka et al. (2018) |

| NCI–H187 | 18 μg/mL | ||||||

| Rhytidchromone A (2) | MCF-7 | 19.3 ± 2.5 μM | Rhytidhysteron rufulum | Bruguiera gymnorrhiza(M) | Thailand | Chokpaiboon et al. (2016) | |

| KATO-3 | 23.3 ± 1.1 μM | ||||||

| Rhytidchromone B (3) | KATO-3 | 21.4 ± 2.3 μM | |||||

| Rhytidchromone C (4) | KATO-3 | 16.8 ± 3.6 μM | |||||

| Rhytidchromone D (5) | MCF-7 | 17.7 ± 3.7 μM | |||||

| KATO-3 | 16.0 ± 1.9 μM | ||||||

| Secalonic acid derivative F-7 (6) | PC-3 | 10.38 ± 0.14 μM | Aspergillus aculeatus MBT 102 | Rosa damascene(T) | India | Farooq et al. (2020) | |

| MCF-7 | 12.97 ± 0.02 μM | ||||||

| HT-29 | 30.23 ± 0.54 μM | ||||||

| SW620 | 22.80 ± 0.14 μM | ||||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 16.60 ± 0.28 μM | ||||||

| PANC-1 | 06.86 ± 0.09 μM | ||||||

| FR-2 | 10.14 ± 0.43 μM | ||||||

| Pyrones | (R)-3,6-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3-methylisochroman-4-one (07) | MV4-11 | 38.39 μM | Aspergillus fumigatus | Cordyceps sinensis(T) | China | Li et al. (2019a) |

| 8-methoxy-3-methylisochromane-3,6-diol (08) | MV4-11 | 30.00 μM | |||||

| Aspermicrone B (09) | HepG2 | 9.9 μM | Aspergillus micronesiensis | Kappaphycus alvarezii(T) | Vietnam | Luyen et al. (2019) | |

| 5,6-dihydro-4-methoxy-6-hydroxymethyl-2H-pyran-2-one (10) | HeLa | 15.60 ± 0.28 μM | Pestalotiopsis palmarum | Sinomenium acutum (Thunb.) (T) | China | Xiao et al. (2018) | |

| HCT116 | 24.35 ± 0.56 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 47.82 ± 2.19 μM | ||||||

| Phomone D (11) | HL-60 | 0.65 μM | Phoma sp. YN02–P-3 | Sumbaviopsis J. J. Smith (T) | China | Sang et al. (2017) | |

| PC-3 | 1.09 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 2.31 μM | ||||||

| Phomone E (12) | HL-60 | 1.04 μM | |||||

| PC-3 | 5.90 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 9.84 μM | ||||||

| Pleospyrone A (13) | HepG2 | 5.07 μM | Pleosporales sp. Sigrf05 | Siraitia grosvenorii(T) | China | Lai et al. (2020) | |

| BGC-823 | 1.26 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H1650 | 15.1 μM | ||||||

| Daoy | 2.72 μM | ||||||

| Pleospyrone D (14) | NCI–H1650 | 29.6 μM | |||||

| Pleospyrone E (15) | HCT-116 | 1.17 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 20.3 μM | ||||||

| BGC-823 | 20.7 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H1650 | 6.26 μM | ||||||

| Daoy | 19.9 μM | ||||||

| Rhizopycnin C (16) | A-549 | 25.5 μM | Rhizopycnis vagum Nitaf22 | Nicotiana tabacum(T) | China | Lai et al. (2016) | |

| HCT116 | 37.3 μM | ||||||

| Xylarione A (17) | MCF-7 | 18 ± 1.08 μM | Xylaria psidii | Aegle marmelos(T) | India | Arora et al. (2016) | |

| MIA-Pa-Ca-2 | 16 ± 1.09 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H226 | 25 ± 1.98 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 37 ± 1.99 μM | ||||||

| DU145 | 22 ± 1.12 μM | ||||||

| Isocoumarins | Oryzaein A (18) | NB4 | 4.2 μM | Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis(T) | China | Zhou et al. (2016) |

| A-549 | 6.5 μM | ||||||

| SHSY5Y | 7.6 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 8.2 μM | ||||||

| Oryzaein B (19) | NB4 | 2.8 μM | |||||

| A-549 | 4.2 μM | ||||||

| SHSY5Y | 3.5 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 4.8 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 3.0 μM | ||||||

| Oryzaein C (20) | NB4 | 7.9 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 5.5 μM | ||||||

| Oryzaein D (21) | A-549 | 6.8 μM | |||||

| SHSY5Y | 8.8 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 6.5 μM | ||||||

| Aspergisocoumrin A (22) | MDA-MB-435 | 05.08 ± 0.88 μM | Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius(M) | China | Wu et al. (2019) | |

| HepG2 | 43.70 ± 1.26 μM | ||||||

| H460 | 21.53 ± 1.37 μM | ||||||

| MCF10A | 11.34 ± 0.58 μM | ||||||

| Aspergisocoumrin B (23) | MDA-MB-435 | 04.98 ± 0.74 μM | |||||

| MCF10A | 21.40 ± 1.71 μM | ||||||

| Palmaerone E (24) | HepG2 | 42.8 μM | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica(T) | China | Zhao et al. (2018a) | |

| Xanthones | Asperanthone (25) | HepG2 | 35.5 ± 0.06 μM | Aspergillus sp. TJ23 | Hypericum perforatum L (T) | China | Qiao et al. (2018) |

| Xanthoquinodin B9 (26) | KB | 7.04 μM | Chaetomium globosum 7s-1 | Rhapis cochinchinensis (Lour.) Mart. (T) | Thailand | Tantapakul et al. (2020) | |

| MCF-7 | 18.4 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H187 | 0.98 μM | ||||||

| Chryxanthone A (27) | A-549 | 41.7 ± 1.9 μM | Penicillium chrysogenum AD-1540 | Grateloupia turuturu(M) | China | Zhao et al. (2018b) | |

| BT-549 | 20.4 ± 1.2 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 23.5 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 33.6 ± 1.4 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 46.4 ± 1.2 μM | ||||||

| Chryxanthone B (28) | A-549 | 20.4 ± 0.9 μM | |||||

| THP-1 | 41.1 ± 0.5 μM | ||||||

| Incarxanthone B (29) | A375 | 8.6 ± 0.2 μM | Peniophora incarnata | Bruguiera gymnorrhiza(M) | China | Li et al. (2020a) | |

| MCF-7 | 6.5 ± 0.4 μM | ||||||

| HL-60 | 4.9 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| Chryxanthone C (30) | HeLa | 23.6 ± 2.1 μM | Paecilamyces sp. TE-540 | Nicotiana tabacum L. (T) | China | Li et al. (2020b) | |

| Phenalenone | Hispidulone B (31) | A-549 | 02.71 ± 0.08 μM | Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum | Dessert plant (T) | China | Zhang et al. (2020) |

| Huh7 | 22.93 ± 1.61 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 23.94 ± 0.33 μM | ||||||

| Diphenyl ethers | Sinopestalotiollide A (32) | HeLa | 18.92 ± 0.77 μM | Pestalotiopsis palmarum | Sinomenium acutum (Thunb.) (T) | China | Xiao et al. (2018) |

| HCT116 | 15.69 ± 0.09 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 31.29 ± 0.72 μM | ||||||

| Sinopestalotiollide B (33) | HeLa | 12.80 ± 0.16 μM | |||||

| HCT116 | 22.67 ± 0.59 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 44.89 ± 1.26 μM | ||||||

| Sinopestalotiollide C (34) | HeLa | 14.66 ± 0.64 μM | |||||

| HCT116 | 18.49 ± 2.81 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 36.13 ± 1.33 μM | ||||||

| Sinopestalotiollide D (35) | HeLa | 1.19 ± 0.02 μM | |||||

| HCT116 | 2.66 ± 0.08 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 2.14 ± 0.05 μM | ||||||

| Unclassified Polyketide | Lijiquinone (36) | RPMI-8226 | 129 μM | Ascomycete sp. F53 | Taxus yunnanensis(T) | China | Cain et al. (2020) |

| (3E,8E,6S)-undeca-3,8,10-triene-1,6-diol (37) | H1975 | 10 μM | Cladosporium sp. OUCMDZ-302 | Excoecaria agallocha(M) | China | Wang et al. (2018) | |

| Cytosporaphenone A (38) | MCF-7 | 70 μM | Cytospora rhizophorae | Morinda officinalis(T) | China | Liu et al. (2017) | |

| HepG2 | 60 μM | ||||||

| Fusarielin J (39) | A2780 | 12.5 μM | Fusarium tricinctum | Aristolochia paucinervis(T) | Morocco | Hemphill et al. (2017) | |

| Fusarielin K (40) | A2780 | 36.5 μM | |||||

| Fusarielin L (41) | A2780 | 84.6 μM | |||||

| Sporulosaldein F (42) | LM3 | 39.2 μM | Paraphaeosphaeria sp. F03 | Paepalanthus planifolius(T) | Brazil | De Amorim et al. (2019) | |

| MCF-7 | 34.4 μM | ||||||

| Peyronetide A (43) | A2780S | 24.1 ± 0.8 μM | Peyronellaea sp. FT431 | Verbena sp. (T) | USA | Li et al. (2019b) | |

| A2780CisR | 28.3 ± 7.2 μM | ||||||

| TK-10 | 29.2 ± 2.9 μM | ||||||

| Peyronetide B (44) | A2780S | 21.5 ± 0.3 μM | |||||

| A2780CisR | 27.2 ± 1.3 μM | ||||||

| TK-10 | 22.7 ± 1.3 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide A (45) | L929 | 6.5 μM | Preussia similis | Globularia alypum(T) | Algeria | Noumeur et al. (2017) | |

| KB3.1 | 6 μM | ||||||

| A431 | 20.3 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 60.3 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 22.6 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 47.7 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 24.3 μM | ||||||

| U2OS | 7.03 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide B (46) | L929 | 17.3 μM | |||||

| KB3.1 | 11.3 μM | ||||||

| A431 | 35.1 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 70.3 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 32.4 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 60.2 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 22.1 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide C (47) | L929 | 9.1 μM | |||||

| KB3.1 | 2.5 μM | ||||||

| A431 | 10.1 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 22.9 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 15.6 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 18.4 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 7.3 μM | ||||||

| U2OS | 6.8 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide D (48) | L929 | 24.7 μM | |||||

| KB3.1 | 17.4 μM | ||||||

| A431 | 17.9 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 47.9 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 20.19 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 45.4 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 15.4 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide E (49) | L929 | 80 μM | |||||

| KB3.1 | 23 μM | ||||||

| A431 | 55.8 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 41.2 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 29.1 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 41.2 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 55.8 μM | ||||||

| Preussilide F (50) | L929 | 53.6 μM | |||||

| KB3.1 | 51.2 μM | ||||||

| U2OS | 22.2 μM | ||||||

| Meroterpenoids | Isocochlioquinone D (51) | SF-268 | 32.8 ± 0.5 μM | Bipolaris sorokiniana A606 | Pogostemon cablin(T) | China | Wang et al. (2016) |

| MCF-7 | 28.3 ± 1.1 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 42.6 ± 2.5 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 38.7 ± 1.1 μM | ||||||

| Isocochlioquinone E (52) | SF-268 | 17.2 ± 1.1 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 28.1 ± 0.7 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 31.1 ± 1.1 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 13.6 ± 0.5 μM | ||||||

| Cochlioquinone G (53) | SF-268 | 35.9 ± 1.3 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 21.1 ± 0.6 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 26.9 ± 2.8 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 11.3 ± 1.9 μM | ||||||

| Cochlioquinone H (54) | SF-268 | 6.4 ± 0.2 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 8.6 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 15.5 ± 0.7 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 7.6 ± 0.1 μM | ||||||

| Bipolahydroquinone C (55) | NCI–H226 | 5.5 μM | Bipolaris sp. L1-2 | Lycium barbarum(T) | China | Long et al. (2019) | |

| MDA-MB-231 | 6.7 μM | ||||||

| Cochlioquinone I (56) | MDA-MB-231 | 8.5 μM | |||||

| Cochlioquinone K (57) | MDA-MB-231 | 9.5 μM | |||||

| Cochlioquinone L (58) | MDA-MB-231 | 7.5 μM | |||||

| Cochlioquinone M (59) | MDA-MB-231 | 5.6 μM | |||||

| Emeridone B (60) | SMMC-7721 | 18.80 ± 0.23 μM | Emericella sp. TJ29 | Hypericum perforatum(T) | China | Li et al. (2019c) | |

| SW-480 | 18.35 ± 0.53 μM | ||||||

| Emeridone D (61) | A-549 | 11.33 ± 0.82 μM | |||||

| SMMC-7721 | 8.19 ± 0.39 μM | ||||||

| SW-480 | 14.67 ± 1.12 μM | ||||||

| Emeridone F (62) | SMMC-7721 | 17.49 ± 0.59 μM | |||||

| SW-480 | 16.84 ± 1.08 μM | ||||||

| 11-dehydroxy epoxyphomalin A (63) | MCF-7 | 2.0 μM | Peyronellaea coffeaearabicae FT238 | Pritchardia lowreyana(T) | USA | Li et al. (2016) | |

| MDA468 | 1.3 μM | ||||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 2.2 μM | ||||||

| T24 | 1.8 μM | ||||||

| OVCAR5 | 1.8 μM | ||||||

| OVCAR4 | 1.4 μM | ||||||

| OVCAR3 | 0.5 μM | ||||||

| IGROV-1/Pt | 1.6 μM | ||||||

| A2780 CisR | 0.6 μM | ||||||

| A2780 | 0.8 μM | ||||||

| Rhizovarin A (64) | A-549 | 11.5 μM | Mucor irregularis | Rhizophora stylosa(M) | China | Gao et al. (2016) | |

| HL-60 | 09.6 μM | ||||||

| Rhizovarin B (65) | A-549 | 6.3 μM | |||||

| HL-60 | 5.0 μM | ||||||

| Rhizovarin E (66) | A-549 | 9.2 μM | |||||

| Isopenicin A (67) | SW480 | 07.91 ± 0.53 μM | Penicillium sp. sh18 | Isodon eriocalyx var. laxiflora(T) | China | Tang et al. (2019) | |

| SW620 | 08.63 ± 0.15 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 09.03 ± 0.61 μM | ||||||

| CaCo2 | 12.56 ± 0.91 μM | ||||||

| SMMC-7721 | 27.66 ± 0.88 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 37.06 ± 2.24 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 27.89 ± 0.70 μM | ||||||

| Isopenicin B (68) | SW480 | 11.60 ± 0.18 μM | |||||

| SW620 | 15.48 ± 1.39 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 14.95 ± 0.22 μM | ||||||

| CaCo2 | 20.34 ± 0.25 μM | ||||||

| SMMC-7721 | 33.49 ± 0.17 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 33.05 ± 0.19 μM | ||||||

| Sesquiterpenoids | Fumagillene A (69) | MV4-11 | 8.40 ± 2.9 μg/mL | Aspergillus fumigatus | Ligusticum wallichii(T) | China | Li et al. (2020c) |

| MDA-MB-231 | 14.3 ± 5.8 μg/mL | ||||||

| Fumagillene B (70) | MV4-11 | 11.2 ± 3.6 μg/mL | |||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 17.3 ± 6.4 μg/mL | ||||||

| Proversilin C (71) | HL-60 | 7.30 ± 1.2 μM | Aspergillus versicolor F210 | Lycoris radiata(T) | China | Li et al. (2020d) | |

| SMMC-7721 | 12.6 ± 0.9 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 15.0 ± 0.8 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 11.8 ± 0.5 μM | ||||||

| SW-480 | 12.4 ± 0.4 μM | ||||||

| Proversilin E (72) | HL-60 | 9.90 ± 1.4 μM | |||||

| SMMC-7721 | 19.4 ± 0.7 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 28.4 ± 1.2 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 18.3 ± 1.2 μM | ||||||

| SW-480 | 16.4 ± 1.0 μM | ||||||

| Lithocarin B (73) | SF-268 | 41.68 ± 0.88 μM | Diaporthe lithocarpus A740 | Morinda officinalis(T) | China | Liu et al. (2019a) | |

| MCF-7 | 37.68 ± 0.30 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 48.33 ± 0.10 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 53.36 ± 0.91 μM | ||||||

| Lithocarin C (74) | SF-268 | 69.46 ± 7.08 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 97.71 ± 0.72 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 79.43 ± 0.63 μM | ||||||

| (R,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (75) | MV4-11 | 22.29 μM | Fusarium tricinctum | Ligusticum chuanxiong(T) | Morocco | Cao et al. (2020) | |

| HCT116 | 54.97 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 93.47 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 69.62 μM | ||||||

| (S,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (76) | MV4-11 | 70.20 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 81.21 μM | ||||||

| Periconianone E (77) | MCF-7 | 17.9 μM | Periconia sp. F-31 | Annona muricata(T) | China | Liu et al. (2016a) | |

| Periconianone H (78) | HeLa | 16.5 μM | |||||

| Pestathenol A (79) | HeLa | 78.2 μM | Pestalotiopsis theae | Camellia sinensis(T) | China | Guo et al. (2020) | |

| Pestathenol B (80) | HeLa | 88.4 μM | |||||

| Rhinomilisin A (81) | L5178Y | 5.0 μM | Rhinocladiella similis | Acrostichums aureum(M) | Cameroon | Liu et al. (2019b) | |

| Rhinomilisin G (82) | L5178Y | 8.7 μM | |||||

| Merulinol C (83) | KATO-3 | 35.0 ± 1.20 μM | Basidiomycetous fungus XG8D | Xylocarpus granatum(M) | Thailand | Choodej et al. (2016) | |

| Merulinol D (84) | KATO-3 | 25.3 ± 0.82 μM | |||||

| Cerrenin D (85) | SF-268 | 41.01 ± 0.34 μM | Cerrena sp. A593 | Pogostemon cablin(T) | China | Liu et al. (2020a) | |

| MCF-7 | 14.34 ± 0.45 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 29.67 ± 0.81 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 44.32 ± 2.12 μM | ||||||

| 7-epi-merulin B (86) | HuCCA-1 | 37.46 ± 3.77 μM | Pseudolagarobasidium acaciicola | Bruguiera gymnorrhiza(M) | Thailand | Wibowo et al. (2016) | |

| A-549 | 24.75 ± 1.09 μM | ||||||

| MOLT-3 | 2.39 ± 0.95 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 8.91 ± 3.13 μM | ||||||

| HL-60 | 0.28 ± 0.18 μM | ||||||

| MDA-MB231 | 12.22 ± 9.26 μM | ||||||

| T47D | 22.25 ± 3.35 μM | ||||||

| MRC-5 | 17.92 ± 4.58 μM | ||||||

| 3-epi-merulin A (87) | MOLT-3 | 17.28 ± 3.66 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 20.71 ± 3.50 μM | ||||||

| HL-60 | 12.09 ± 3.50 μM | ||||||

| MRC-5 | 17.83 ± 2.72 μM | ||||||

| Diterpenoid | (10S)-12,16-epoxy-17 (15 → 16)-abeo-3,5,8,12,15-abietapentaen-2,7,11,14-tetraone (88) | HL-60 | 12.54 ± 1.18 μM | Pestalotiopsis adusta | Clerodendrum canescens(T) | China | Xu et al. (2016) |

| Triterpenoids | Integracide H (89) | BT-549 | 1.82 μM | Fusarium sp. | Mentha longifolia L. (T) | Saudi Arabia | Ibrahim et al. (2016a) |

| SKOV-3 | 1.32 μM | ||||||

| KB | 0.18 μM | ||||||

| Integracide J (90) | BT-549 | 2.46 μM | |||||

| SKOV-3 | 3.01 μM | ||||||

| KB | 2.54 μM | ||||||

| Steroid | Demethylincisterol A5 (91) | A-549 | 11.05 μM | Aspergillus tubingensis YP-2 | Taxus yunnanensis(T) | China | Yu et al. (2019) |

| HepG2 | 19.15 μM | ||||||

| Macrolides | Myrothecine D (92) | K562 | 8.20 μM | Myrothecium roridum | Trachelospermum jasminoides (Lindl.) Lem (T) | China | Shen et al. (2019) |

| SW1116 | 0.57 μM | ||||||

| Myrothecine E (93) | K562 | 15.98 μM | |||||

| SW1116 | 11.61 μM | ||||||

| Myrothecine F (94) | K562 | 00.97 μM | |||||

| SW1116 | 10.62 μM | ||||||

| Myrothecine G (95) | K562 | 01.53 μM | |||||

| SW1116 | 04.25 μM | ||||||

| 16-hydroxymytoxin B (96) | K562 | 2.87 μM | |||||

| SW1116 | 0.18 μM | ||||||

| 14′-dehydrovertisporin (97) | K562 | 0.056 μM | |||||

| SW1116 | 0.200 μM | ||||||

| Epiroridin acid (98) | SF-268 | 0.751 ± 0.03 μM | Myrothecium roridum A553 | Pogostemon cablin(T) | China | Liu et al. (2016b) | |

| MCF-7 | 0.170 ± 0.01 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 0.360 ± 0.05 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 0.380 ± 0.03 μM | ||||||

| Myrothecine H (99) | SF-268 | 6.75 ± 0.22 μM | Paramyrothecium roridum | Morinda officinalis(T) | China | Liu et al. (2020b) | |

| HepG2 | 6.72 ± 0.27 μM | ||||||

| Myrothecine I (100) | SF-268 | 0.20 ± 0.01 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 0.20 ± 0.03 μM | ||||||

| 7-O-Methylnigrosporolide (101) | L5178Y | 0.7 μM | Pestalotiopsis microspora | Drepanocarpus lunatus(M) | Cameroon | Liu et al. (2016c) | |

| A2780 | 28 μM | ||||||

| Pestalotioprolide C (102) | L5178Y | 39 μM | |||||

| Pestalotioprolide D (103) | L5178Y | 5.6 μM | |||||

| Pestalotioprolide E (104) | L5178Y | 3.4 μM | |||||

| A2780 | 1.2 μM | ||||||

| Pestalotioprolide F (105) | L5178Y | 3.9 μM | |||||

| A2780 | 12 μM | ||||||

| Pestalotioprolide G (106) | A2780 | 36 μM | |||||

| Pestalotioprolide H (107) | L5178Y | 11 μM | |||||

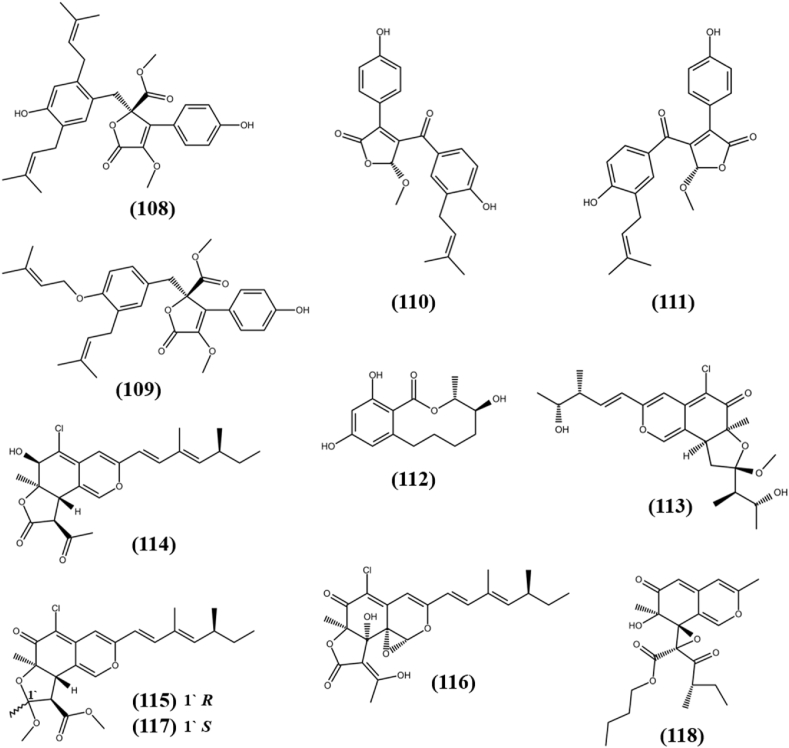

| Lactones | Asperlactone G (108) | A-549 | 65.3 ± 1.06 μM | Aspergillus sp. | Pinellia ternate(T) | China | Xin et al. (2019) |

| Asperlactone H (109) | A-549 | 23.3 ± 2.01 μM | |||||

| (−)-Asperteretone E (110) | AsPC-1 | 9.50 μM | Aspergillus terreus | Hypericum perforatum(T) | China | Deng et al. (2020) | |

| SW1990 | 11.7 μM | ||||||

| PANC-1 | 9.80 μM | ||||||

| (+)-Asperteretone E (111) | AsPC-1 | 9.90 μM | |||||

| SW1990 | 10.3 μM | ||||||

| PANC-1 | 15.6 μM | ||||||

| Hispidulactone F (112) | HepG2 | 61.05 μM | Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum (TS-8-1) | Dessert plant (T) | China | Zheng et al. (2020) | |

| Azaphilones | Chaephilone C (113) | HepG2 | 38.6 μM | Chaetomium globosum TY-2 | Polygonatum Sibiricum(T) | China | Song et al. (2020) |

| Isochromophilone A (114) | ACHN | 27 μM | Diaporthe sp. SCSIO 41011 | Rhizophora stylosa(M) | China | Luo et al. (2018) | |

| 786-O | 34 μM | ||||||

| OS-RC-2 | 45 μM | ||||||

| Isochromophilone D (115) | ACHN | 14 μM | |||||

| 786-O | 8.9 μM | ||||||

| OS-RC-2 | 13 μM | ||||||

| Isochromophilone F (116) | ACHN | 13 μM | |||||

| 786-O | 10 μM | ||||||

| OS-RC-2 | 38 μM | ||||||

| Isochromophilone C (117) | 786-O | 38 μM | |||||

| OS-RC-2 | 44 μM | ||||||

| Phomopsone C (118) | A-549 | 08.9 μMa | Phomopsis sp. CGMCC No.5416 | Achyranthes bidentata(T) | China | Yang et al. (2020a) | |

| MDA-MB-231 | 03.2 μMa | ||||||

| PANC-1 | 17.3 μMa | ||||||

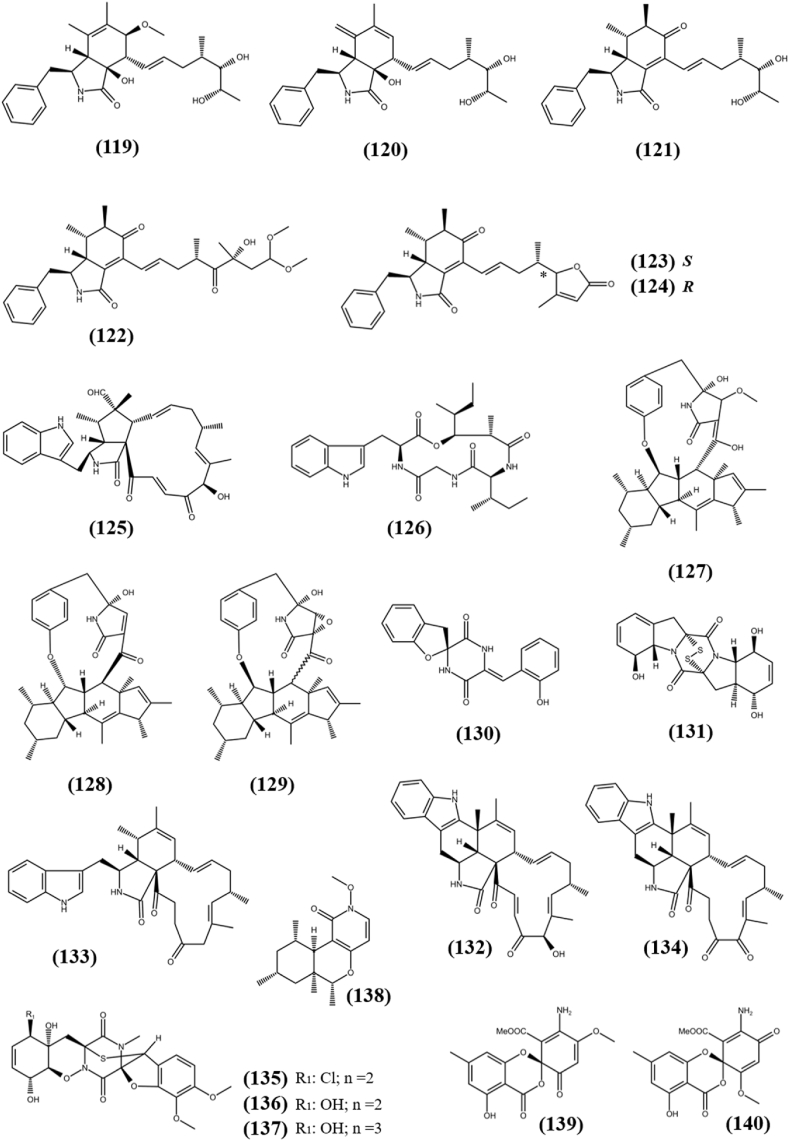

| Alkaloids | Asperchalasin A (119) | A-549 | 55.5 ± 1.87 μM | Aspergillus sp. | Pinellia ternate(T) | China | Xin et al. (2019) |

| Asperchalasin B (120) | A-549 | 54.2 ± 1.22 μM | |||||

| Asperchalasin C (121) | A-549 | 47.2 ± 0.92 μM | |||||

| Asperchalasin D (122) | A-549 | 40.6 ± 1.30 μM | |||||

| Asperchalasin E (123) | A-549 | 55.2 ± 1.85 μM | |||||

| Asperchalasin F (124) | A-549 | 70.2 ± 1.76 μM | |||||

| Pchaeglobosal B (125) | MCF-7 | 8.59 ± 0.40 μM | Chaetomium globosum P2-2-2 | Ptychomitrium sp. (T) | China | Peng et al. (2020a) | |

| HepG2 | 7.09 ± 0.11 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 1.04 ± 0.04 μM | ||||||

| HT29 | 9.90 ± 0.68 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 6.92 ± 0.21 μM | ||||||

| Chaetomiamide A (126) | HL-60 | 35.2 μM | Chaetomium sp. | Cymbidium Goeringii(T) | China | Wang et al. (2017) | |

| Ascomylactam A (127) | MDAMB-435 | 4.9 μM | Didymella sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica(M) | China | Chen et al. (2019) | |

| MDAMB-231 | 5.9 μM | ||||||

| SNB19 | 6.8 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 5.5 μM | ||||||

| NCIH460 | 4.4 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 5.7 μM | ||||||

| Ascomylactam B (128) | MDAMB-435 | 12 μM | |||||

| MDAMB-231 | 6.6 μM | ||||||

| SNB19 | 18 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 4.5 μM | ||||||

| NCIH460 | 13 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 20 μM | ||||||

| Ascomylactam C (129) | MDAMB-435 | 7.8 μM | |||||

| MDAMB-231 | 5.1 μM | ||||||

| SNB19 | 7.8 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 4.2 μM | ||||||

| NCIH460 | 4.4 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 7.5 μM | ||||||

| Spirobrocazine C (130) | A2780 | 59 μM | Penicillium brocae MA-231 | Avicennia marina(M) | China | Meng et al. (2016) | |

| Brocazine G (131) | A2780 | 0.664 μM | |||||

| A2780 CisR | 0.661 μM | ||||||

| Penochalasin I (132) | MDA-MB-435 | 07.55 ± 0.71 μM | Penicillium chrysogenum V11 | Myoporum bontioides(M) | China | Huang et al. (2016) | |

| SGC-7901 | 07.32 ± 0.68 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 16.13 ± 0.82 μM | ||||||

| Penochalasin J (133) | MDA-MB-435 | 36.68 ± 0.90 μM | |||||

| SGC-7901 | 37.70 ± 1.30 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 35.93 ± 0.66 μM | ||||||

| Penochalasin K (134) | MDA-MB-435 | 4.65 ± 0.45 μM | Penicillium chrysogenum V11 | Myoporum bontioides(M) | China | Zhu et al. (2017a) | |

| SGC-7901 | 5.32 ± 0.58 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 8.73 ± 0.62 μM | ||||||

| Penicisulfuranol A (135) | HeLa | 0.5 μM | Penicillium janthinellum HDN13-309 | Sonneratia caseolaris(M) | China | Zhu et al. (2017b) | |

| HL-60 | 0.1 μM | ||||||

| Penicisulfuranol B (136) | HeLa | 3.9 μM | |||||

| HL-60 | 1.6 μM | ||||||

| Penicisulfuranol C (137) | HeLa | 0.3 μM | |||||

| HL-60 | 1.2 μM | ||||||

| Chromenopyridin A (138) | A-549 | 14.7 μM | Penicillium nothofagi P-6 | Abies beshanzuensis(T) | China | Zhu et al. (2020) | |

| HeLa | 11.3 μM | ||||||

| 2′-aminodechloromaldoxin (139) | NCI–H460 | 18.63 ± 1.82 μM | Pestalotiopsis flavidula | Cinnamomum camphora(T) | China | Rao et al. (2019) | |

| SF-268 | 20.23 ± 2.15 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 23.53 ± 2.33 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 20.48 ± 2.04 μM | ||||||

| 2′-aminodechlorogeodoxin (140) | NCI–H460 | 16.47 ± 1.63 μM | |||||

| SF-268 | 17.57 ± 2.12 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 20.79 ± 2.39 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 19.43 ± 2.02 μM | ||||||

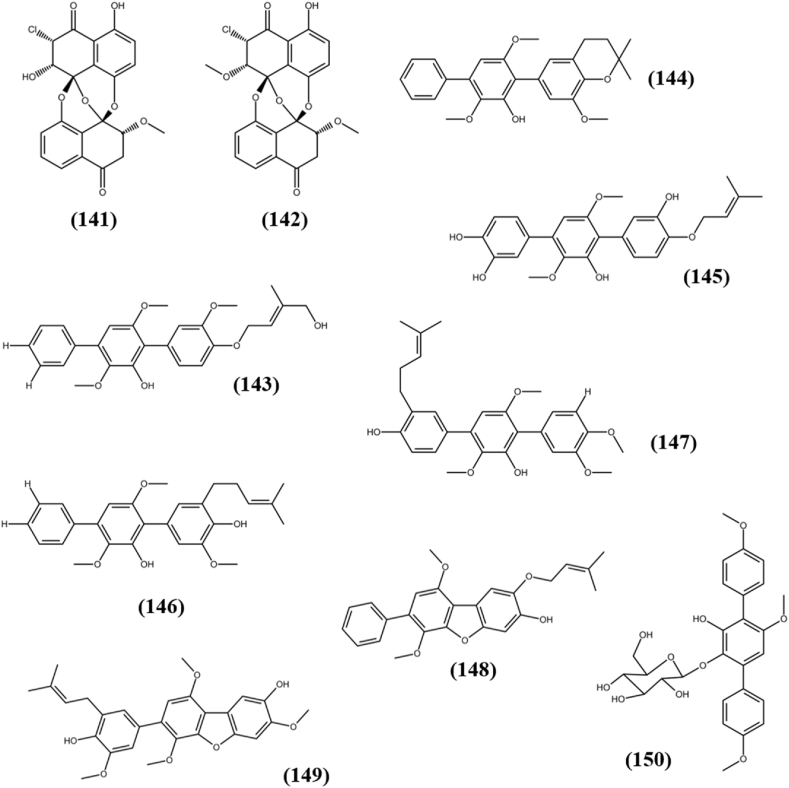

| Preussomerins | Chloropreussomerin A (141) | A-549 | 8.5 ± 0.9 μM | Lasiodiplodia theobromae ZJ-HQ1 | Acanthus ilicifolius(M) | China | Chen et al. (2016) |

| HepG2 | 13 ± 1 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 19 ± 1 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 5.9 ± 0.4 μM | ||||||

| HEK293T | 4.8 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| Chloropreussomerin B (142) | A-549 | 8.9 ± 0.6 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 7.7 ± 0.1 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 27 ± 3 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 6.2 ± 0.4 μM | ||||||

| HEK293T | 11 ± 3.0 μM | ||||||

| p-terphenyls | Prenylterphenyllin F (143) | L-02 | 19.9 μM | Aspergillus candidus LDJ-5 | Rhizophora apiculate(M) | China | Zhou et al. (2020) |

| MGC-803 | 11.0 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 09.3 μM | ||||||

| BEL-7402 | 12.4 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 10.2 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 10.4 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 08.3 μM | ||||||

| HL-60 | 07.1 μM | ||||||

| Prenylterphenyllin G (144) | L-02 | 29.7 μM | |||||

| MGC-803 | 12.5 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 16.9 μM | ||||||

| BEL-7402 | 12.6 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 16.3 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 12.4 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 11.5 μM | ||||||

| Prenylterphenyllin H (145) | L-02 | 3.5 μM | |||||

| MGC-803 | 0.7 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 0.5 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 0.4 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 0.6 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 2.0 μM | ||||||

| U87 | 13.8 μM | ||||||

| Prenylterphenyllin I (146) | L-02 | 24.4 μM | |||||

| MGC-803 | 14.5 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 14.7 μM | ||||||

| BEL-7402 | 11.1 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 14.8 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 16.7 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 11.4 μM | ||||||

| Prenylterphenyllin J (147) | MGC-803 | 8.10 μM | |||||

| HCT-116 | 6.20 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 7.60 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 15.6 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 8.50 μM | ||||||

| K562 | 15.9 μM | ||||||

| Prenylcandidusin E (148) | L-02 | 16.7 μM | |||||

| MGC-803 | 16.3 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 19.8 μM | ||||||

| BEL-7402 | 14.9 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 19.1 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 17.9 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 14.0 μM | ||||||

| U87 | 10.3 μM | ||||||

| K562 | 05.0 μM | ||||||

| Prenylcandidusin G (149) | L-02 | 17.9 μM | |||||

| MGC-803 | 1.40 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 0.90 μM | ||||||

| BEL-7402 | 16.0 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 2.80 μM | ||||||

| SH-SY5Y | 2.20 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 10.1 μM | ||||||

| HL-60 | 3.40 μM | ||||||

| Gliocladinin C (150) | Hep-2 | 0.18 μM | Chaetomium subaffine L01 | Potato (T) | China | Han et al. (2019) | |

| HepG2 | 0.12 μM | ||||||

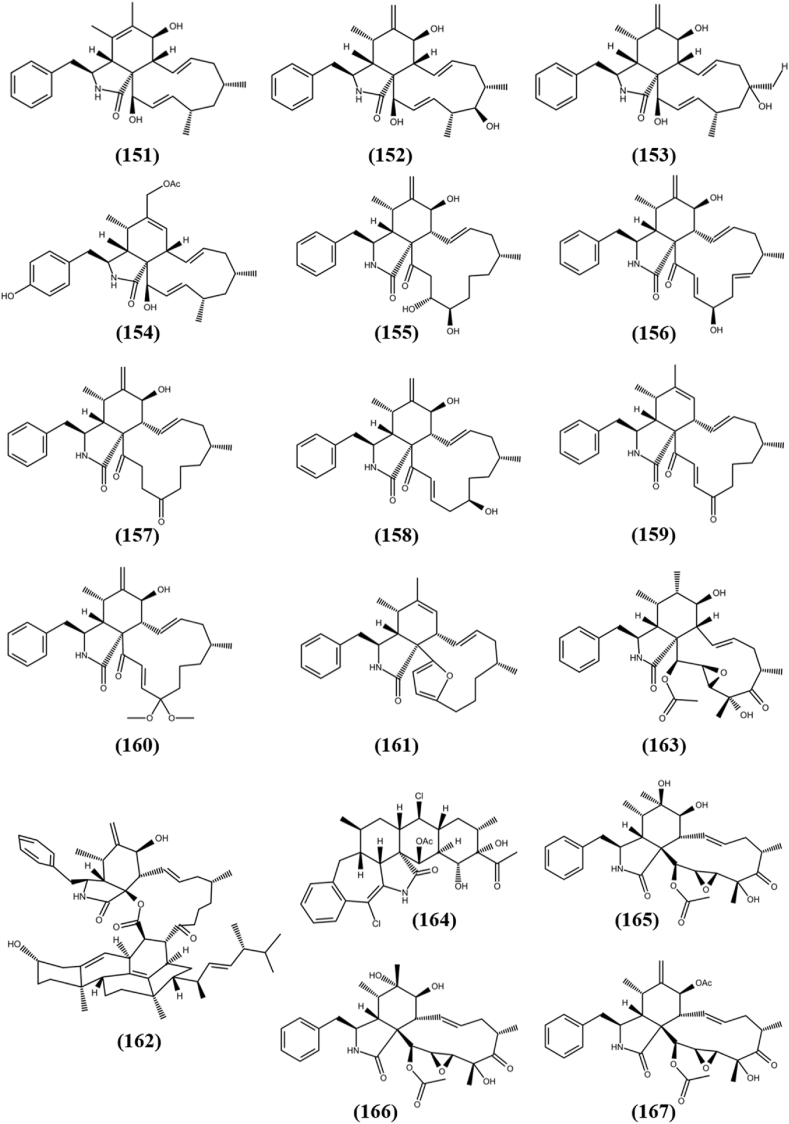

| Cytochalasans | Diaporthichalasin D (151) | A-549 | 13.7 ± 2.3 μM | Diaporthe sp. SC-J0138 | Cyclosorus parasiticus(T) | China | Yang et al. (2020b) |

| HeLa | 15.3 ± 2.7 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 08.8 ± 1.7 μM | ||||||

| Diaporthichalasin E (152) | HepG2 | 30.6 ± 2.5 μM | |||||

| Diaporthichalasin F (153) | HeLa | 34.7 ± 5.6 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 16.5 ± 2.2 μM | ||||||

| Diaporthichalasin H (154) | A-549 | 13.9 ± 2.1 μM | |||||

| HeLa | 20.0 ± 1.5 μM | ||||||

| HepG2 | 09.9 ± 1.6 μM | ||||||

| MCF–7 | 32.1 ± 1.5 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin B (155) | HepG2 | 31.95 ± 1.86 μM | Phoma multirostrata | Parasenecio albus(T) | China | Peng et al. (2020b) | |

| CT26 | 27.40 ± 0.68 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin E (156) | MCF-7 | 34.08 ± 5.88 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 32.05 ± 1.54 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 17.20 ± 0.23 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 25.51 ± 0.83 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin F (157) | MCF-7 | 22.29 ± 0.35 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 23.02 ± 0.24 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 19.20 ± 1.63 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 43.22 ± 4.49 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin G (158) | MCF-7 | 10.22 ± 0.43 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 17.69 ± 0.27 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 06.03 ± 0.85 μM | ||||||

| HT29 | 43.03 ± 1.79 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 05.04 ± 0.18 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin H (159) | MCF-7 | 31.52 ± 0.82 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 20.85 ± 0.48 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 21.89 ± 0.35 μM | ||||||

| HT29 | 16.30 ± 0.60 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 26.63 ± 0.49 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin I (160) | CT26 | 19.31 ± 0.40 μM | |||||

| HT29 | 24.09 ± 0.73 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 36.58 ± 1.10 μM | ||||||

| Multirostratin J (161) | MCF-7 | 30.75 ± 1.48 μM | |||||

| HepG2 | 25.29 ± 3.91 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 14.53 ± 0.13 μM | ||||||

| HT29 | 21.33 ± 1.19 μM | ||||||

| Ergocytochalasin A (162) | HepG2 | 21.32 ± 0.30 μM | Phoma multirostrata XJ-2-1 | Parasenecio albus(T) | China | Peng et al. (2020c) | |

| A-549 | 19.11 ± 0.99 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 26.63 ± 0.13 μM | ||||||

| HCT116 | 22.28 ± 2.65 μM | ||||||

| HT-29 | 15.23 ± 0.67 μM | ||||||

| CT26 | 06.92 ± 0.71 μM | ||||||

| Jammosporin A (163) | MOLT-4 | 20 μM | Rosellinia sanctaecruciana | Albizia lebbeck(T) | India | Sharma et al. (2018a) | |

| Xylarichalasin A (164) | HL-60 | 17.3 ± 1.6 μM | Xylaria cf. curta | Solanum tuberosum(T) | China | Wang et al. (2019a) | |

| A-549 | 11.8 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| SMMC-7721 | 08.6 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 06.3 ± 0.1 μM | ||||||

| SW480 | 13.2 ± 0.3 μM | ||||||

| 19-epi-cytochalasin P1 (165) | HL-60 | 13.31 ± 0.13 μM | Xylaria cf. curta | Solanum tuberosum(T) | China | Wang et al. (2019b) | |

| 7-O-acetyl-6-epi-19,20-epoxycytochalasin P (166) | HL-60 | 37.16 ± 1.90 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 26.64 ± 1.37 μM | ||||||

| 7-O-acetyl-19,20-epoxycytochalasin D (167) | HL-60 | 25.83 ± 1.42 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 34.03 ± 2.10 μM | ||||||

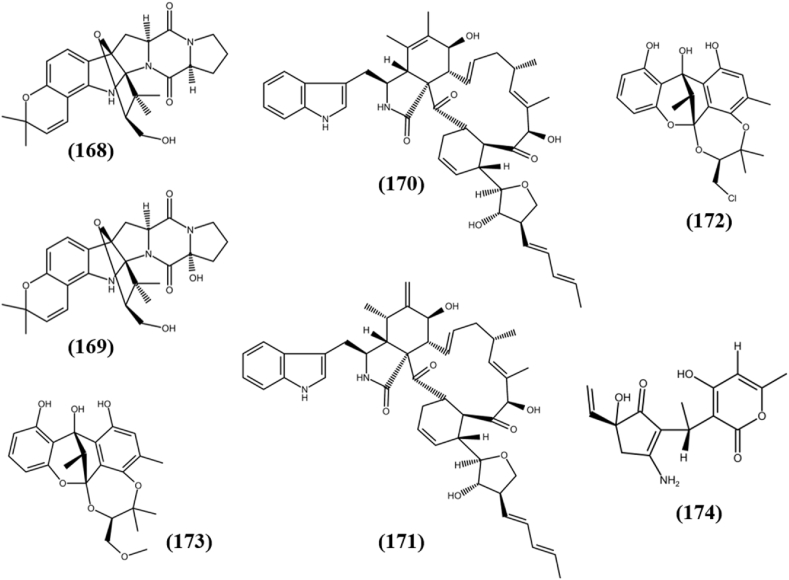

| Other Hybrids | Gartryprostatin A (168) | MV4-11 | 7.20 μM | Aspergillus sp. GZWMJZ-258 | Garcinia multiflora(T) | China | He et al. (2019) |

| Gartryprostatin B (169) | MV4-11 | 10.0 μM | |||||

| Aureochaeglobosin B (170) | MDA-MB-231 | 7.6 ± 0.5 μM | Chaetomium globosum | Pinellia ternate(T) | China | Yang et al. (2018) | |

| Aureochaeglobosin C (171) | MDA-MB-231 | 10.8 ± 0.64 μM | |||||

| Cytorhizin B (172) | HepG2 | 29.4 ± 4.4 μM | Cytospora rhizophorae A761 | Morinda officinalis(T) | China | Liu et al. (2019c) | |

| MCF-7 | 30.1 ± 3.3 μM | ||||||

| SF-268 | 34.8 ± 1.4 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 32.8 ± 4.1 μM | ||||||

| Cytorhizin C (173) | HepG2 | 68.6 ± 8.2 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 58.6 ± 1.8 μM | ||||||

| SF-268 | 36.8 ± 5.1 μM | ||||||

| NCI–H460 | 54.7 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| Trichoderpyrone (174) | A-549 | 16.9 ± 1.3 μM | Trichoderma gamsii | Panax notoginseng (BurK.) F.H. Chen (T) | China | Chen et al. (2017) | |

| HepG2 | 30.8 ± 0.2 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 33.9 ± 0.7 μM | ||||||

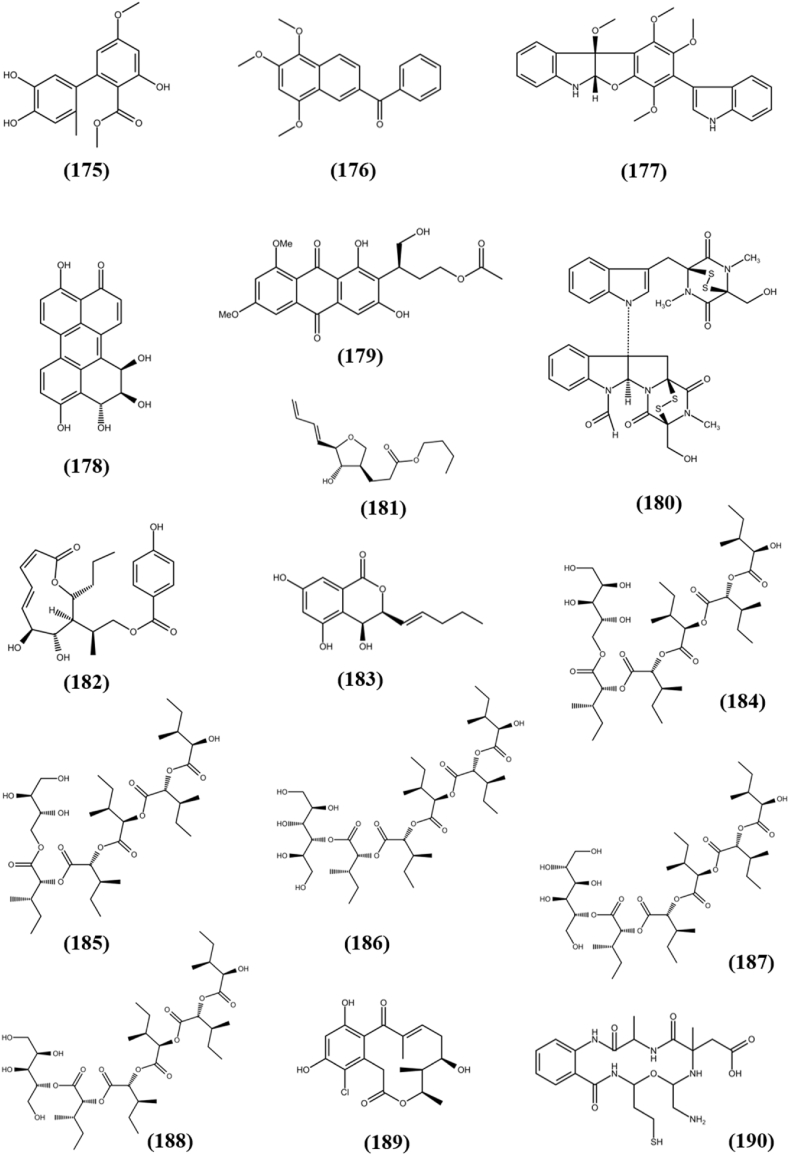

| Miscellaneous Compounds | Alternate C (175) | MDA-MB-231 | 20.1 μM | Alternaria alternata | Paeonia lactiflora(T) | China | Wang et al. (2019c) |

| MCF-7 | 32.2 μM | ||||||

| Nigronapthaphenyl (176) | HCT 116 | 9.62 ± 0.5 μM | Nigrospora sphaerica | Bruguiera gymnorrhyza(M) | Sri Lanka | Ukwatta et al. (2019) | |

| Varioloid A (177) | A-549 | 3.5 μg/mL | Paecilomyces variotii EN-291 | Grateloupia turuturu(M) | China | Zhang et al. (2016a) | |

| HCT116 | 6.4 μg/mL | ||||||

| HepG2 | 2.5 μg/mL | ||||||

| Altertoxin IV (178) | MG-63 | 14.81 μg/mL | Alternaria sp. G7 | Broussonetia papyrifera(T) | China | Zhang et al. (2016b) | |

| SMMC-7721 | 22.87 μg/mL | ||||||

| Asperxin A (179) | A-549 | 11.72 μg/mL | Aspergillus sp. Y-2 | Abies beshanzuensis(T) | China | Zhu et al. (2019) | |

| HeLa | 16.78 μg/mL | ||||||

| 6-formamidechetomin (180) | HeLa | 21.6 nM | Chaetomium sp. M336 | Huperzia serrata Trev. (T) | China | Yu et al. (2018) | |

| SGC-7901 | 23.0 nM | ||||||

| A-549 | 27.1 nM | ||||||

| Chaetominin A (181) | Hep-2 | 0.23 μM | Chaetomium subaffine L01 | Potato (T) | China | Han et al. (2019) | |

| HepG2 | 0.38 μM | ||||||

| Xylarolide A (182) | MIA-PA-CA-2 | 20 ± 0.17 μM | Diaporthe sp. | Datura inoxia(T) | India | Sharma et al. (2018b) | |

| MCF-7 | 30 ± 1.02 μM | ||||||

| PC-3 | 14 ± 0.12 μM | ||||||

| Diportharine A (183) | MIA-PA-CA-2 | 34 ± 1.32 μM | |||||

| PC-3 | 22 ± 0.83 μM | ||||||

| Hormonemate A (184) | HepG2 | 29.0 μM | Dothiora sp. | Launaea arborescens(T) | Spain | Pérez-Bonilla et al. (2017) | |

| MCF-7 | 15.6 μM | ||||||

| Hormonemate B (185) | HepG2 | 28.7 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 11.1 μM | ||||||

| Hormonemate C (186) | MCF-7 | 27.8 μM | |||||

| Hormonemate D (187) | HepG2 | 36.2 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 18.3 μM | ||||||

| Hormonemate E (188) | HepG2 | 26.2 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | 19.0 μM | ||||||

| MiaPaca_2 | 36.4 μM | ||||||

| (13R,14S,15R)- 13-hydroxy-14-deoxyoxacy-clododecindione (189) | A-549 | 9.2 μM | Exserohilum rostratum | Gymnadenia conopsea(T) | China | Lin et al. (2018) | |

| Fusarithioamide B (190) | SK-MEL | 11.2 ± 0.95 μM | Fusarium chlamydosporium | Anvillea garcinii (Burm.f.) DC. (T) | Egypt | Ibrahim et al. (2018) | |

| KB | 6.9 ± 0.75 μM | ||||||

| BT-549 | 0.09 ± 0.05 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 1.23 ± 0.03 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 0.21 ± 0.07 μM | ||||||

| HCT-116 | 0.59 ± 0.01 μM | ||||||

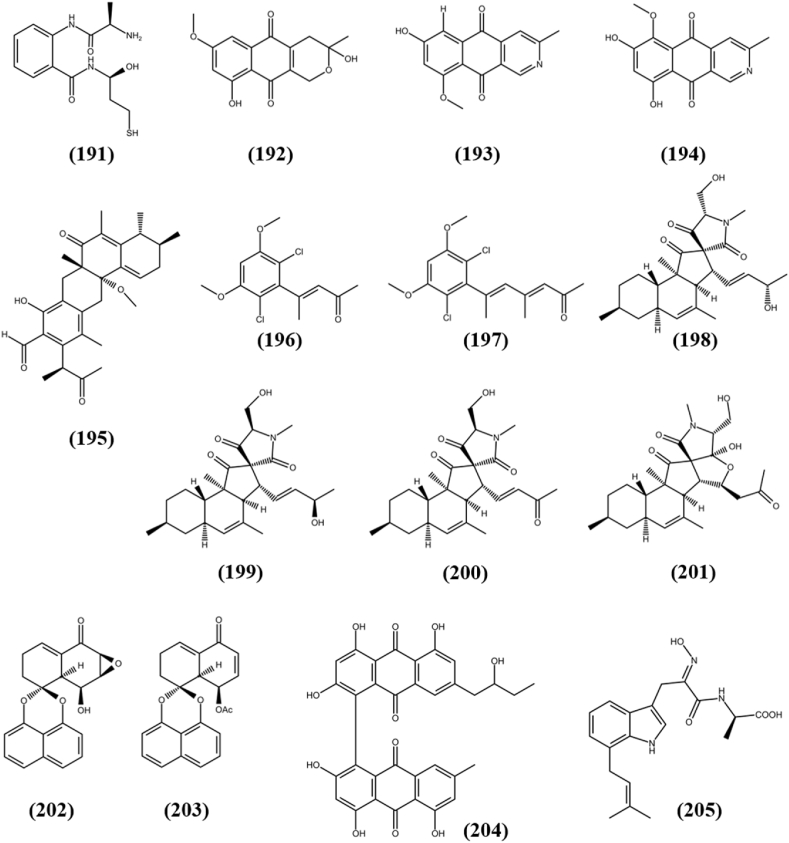

| Fusarithioamide A (191) | SK-MEL | 9.3 ± 0.86 μM | Fusarium chlamydosporium | Anvillea garcinia (Burm.f.) DC. (T) | Egypt | Ibrahim et al. (2016b) | |

| KB | 7.7 ± 0.95 μM | ||||||

| BT-549 | 0.4 ± 0.07 μM | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 0.8 ± 0.01 μM | ||||||

| 9-desmethylherbarine (192) | WI38 | 10.3 μM | Fusarium solani | Aponogeton undulatus(T) | Bangladesh | Chowdhury et al. (2017) | |

| NCI HI975 | 30.72 μM | ||||||

| MIA PaCa2 | 20.46 μM | ||||||

| MDA MB 231 | 27.73 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 54.34 μM | ||||||

| 7-desmethylscorpinone (193) | WI38 | 0.96 μM | |||||

| NCI HI975 | 1.51 μM | ||||||

| MIA PaCa2 | 0.98 μM | ||||||

| MDA MB 231 | 0.61 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 5.84 μM | ||||||

| 7-desmethyl-6-methylbostrycoidin (194) | WI38 | 0.71 μM | |||||

| NCI HI975 | 0.73 μM | ||||||

| MIA PaCa2 | 0.64 μM | ||||||

| MDA MB 231 | 0.34 μM | ||||||

| HeLa | 6.42 μM | ||||||

| Penctrimertone (195) | HL-60 | 16.77 μM | Penicillium sp. T2-11 | Gastrodsia elata(T) | China | Li et al. (2020e) | |

| SMMC-7721 | 23.63 μM | ||||||

| A-549 | 28.62 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 21.53 μM | ||||||

| SW480 | 39.32 μM | ||||||

| Cosmochlorin D (196) | HL60 | 6.1 μM | Phomopsis sp. N-125 | Ficus ampelasa(T) | Japan | Shiono et al. (2017) | |

| Cosmochlorin E (197) | HL60 | 1.8 μM | |||||

| Pyrenosetin A (198) | A-375 | 2.8 μM | Pyrenochaetopsis sp. FVE-001 | Fucus vesiculosus(M) | Germany | Fan et al. (2020a) | |

| HaCaT | 4.2 μM | ||||||

| Pyrenosetin B (199) | A-375 | 6.3 μM | |||||

| HaCaT | 35 μM | ||||||

| Pyrenosetin C (200) | A-375 | 140.3 μM | |||||

| HaCaT | 142.9 μM | ||||||

| Pyrenosetin D (201) | A-375 | 77.5 μM | Pyrenochaetopsis sp. FVE-087 | Fucus vesiculosus(M) | Germany | Fan et al. (2020b) | |

| HaCaT | 39.3 μM | ||||||

| Rhytidenone G (202) | Ramos | 17.98 μM | Rhytidhysteron rufulum AS21B | Azima sarmentosa(M) | Thailand | Siridechakorn et al. (2017) | |

| H1975 | 07.30 μM | ||||||

| Rhytidenone H (203) | Ramos | 0.018 μM | |||||

| H1975 | 0.252 μM | ||||||

| 3-demethyl-3-(2-hydroxypropyl)-skyrin (204) | MCF-7 | 20.76 ± 3.41 μg/mL | Talaromyces sp. YE3016 | Aconitum carmichaeli(T) | China | Xie et al. (2016) | |

| Terezine E (205) | HUVEC | 28.02 μg/mLa | Mucor sp. | Centaurea stoebe(T) | USA | Abdou et al. (2020) | |

| K-562 | 27.31 μg/mLa | ||||||

| HeLa | 60.43 μg/mLa |

CC50

T: terrestrial plant; M: marine plant.

2.1. Polyketides

Polyketides are biologically active and chemically diverse family of secondary metabolites that come from mammals, plants, fungi, and bacteria. Doxorubicin is a well-known anticancer molecule obtained as a polyketide from fungi (Tacar et al., 2013). Herein, 50 polyketides are classified as chromones, pyrones, isocoumarins, lactones, xanthones, phenalenones, diphenyl ethers, and unclassified polyketides.

2.1.1. Chromones

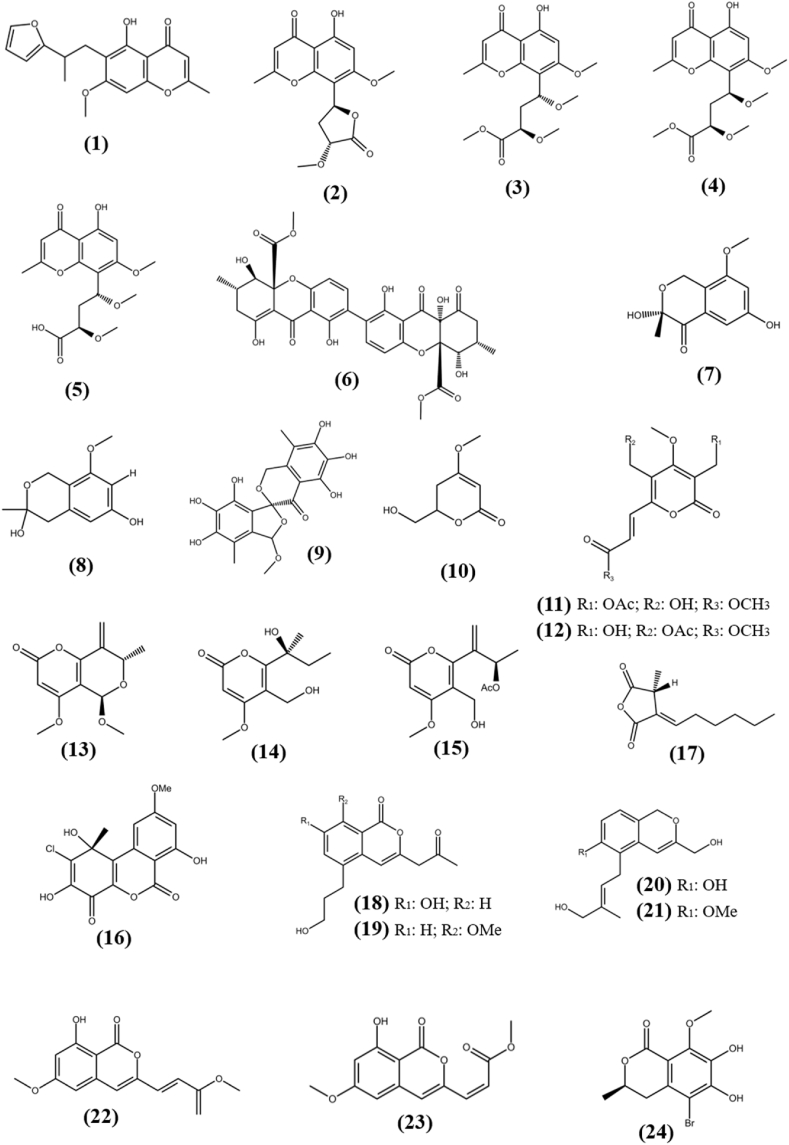

Chromones are phenolic derivatives of chromone and isomers of coumarin that have been confirmed to have anti-tumor, anti-viral, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties (di Duan et al., 2019). A chromone derivative, Botryochromone (1) was isolated from unidentified strain (BCC 54265) of Botryosphaeriaceae family, which was obtained from a leaf of the Vietnamese coriander, Polygonum odoratum and exhibited weak cytotoxicity to epidermoid (KB) and human small cell lung cancer (NCI–H187) cell lines with IC50 values of 43 and 18 μg/mL, while remain inactive against MCF-7, a human breast cancer cell line (Isaka et al., 2018). Rhytidchromones A–D (2-5) are highly oxygenated chromones, which were separated from the culture broth of fungus Rhytidhysteron rufulum, an endophyte associated with marine Thai Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. All compounds were tested for cytotoxic activity against four tumor cell lines human breast (MCF-7), liver (HepG2), gastric (KATO-3) and cervical (CaSki), in which they remain inactive against HepG2 and CaSki cells with IC50s of >25 μM. Compound Rhytidchromone A and Rhytidchromone D were active against MCF-7 and KATO-3 cells with IC50 value of 19.3 ± 2.5, 23.3 ± 1.1 μM and 17.7 ± 3.7, 16.0 ± 1.9 μM, respectively, while compound Rhytidchromone B and Rhytidchromone C were cytotoxic towards only KATO-3 cells with IC50s of 21.4 ± 2.3 and 16.8 ± 3.6 μM, respectively (Chokpaiboon et al., 2016). A new Secalonic acid derivative, F-7 (6), an ergochrome which is dimeric xanthene linked at second position, was discovered from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus aculeatus MBT 102, obtained from Rosa damascene. It showed strong cytotoxic activity against triple negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) with 16.6 ± 0.28 μM IC50 value and found to induce apoptosis through phase contrast and scanning electron microscopy. It also exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against PC-3 (prostatic cancer), MCF-7, HT-29 (human colon carcinoma), SW620 (colon cancer), PANC-1 (pancreatic cancer) and FR-2 (normal human breast epithelial cells) with IC50 values in the range of 6.86–30.23 μM (Farooq et al., 2020). The structures of chromones (1–6) are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of chromones (1–6), pyrones (7–17) and isocoumarins (18–24).

2.1.2. Pyrones

Dibenzo-pyrones are polyketides with a 6H-benzo [c]-chromen-6-one tricyclic skeleton that have been shown to be biologically active in nature. Two unprecedented isochromane molecules, (R)-3,6-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3-methylisochroman-4-one (7), and 8-methoxy-3-methylisochromane-3,6-diol (8) were obtained from the fermentation broth of Aspergillus fumigatus, an endophytic fungus associated with Cordyceps sinensis. Compounds (7) and (8) exhibited moderate antiproliferative activity against a FLT3 positive acute myeloid leukemia cell line (MV4-11) with IC50s of 38.39 and 30.00 μM respectively, while remain inactive against MCF-7, HCT116 (colon cancer) and A-549 (human lung adenocarcinoma) cell lines (Li et al., 2019a). A novel dibenzospiroketal, Aspermicrone B (9) was obtained from the culture of endophytic fungus Aspergillus micronesiensis, which was derived from edible red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii. It showed selective antiproliferative activity towards HepG2 cell line with IC50 value of 9.9 μM, while other compounds remain inactive (Luyen et al., 2019). A fermented culture of fungus Pestalotiopsis palmarum, an endophyte harbored in the leaves of medicinal plant Sinomenium acutum (Thunb.) Rehd et Wils was detected with the novel α-pyrone, 5,6-dihydro-4-methoxy-6-hydroxymethyl-2H-pyran-2-one (10). It showed cytotoxic activity against HeLa (human cervical carcinoma cells), HCT116, and A-549 cell lines with IC50s of 15.60 ± 0.28 μM, 24.35 ± 0.56 μM, and 47.82 ± 2.19 μM, respectively, that is comparatively higher than known anticancer compound doxorubicin, which showed cytotoxicity in the range of 0.86–8.9 μM (Xiao et al., 2018). Two new α-pyrone derivatives, Phomone D (11) and Phomone E (12) were separated from the fermented culture of fungus Phoma sp. YN02–P-3, an endophyte associated with the plant Sumbaviopsis J. J. Smith. Phomone D and Phomone E showed cytotoxicity against three human cancer cell lines HL-60 (acute leukemia), PC-3 and HCT-116 with IC50s of 0.65, 1.09, 2.31 μM and 1.04, 5.9, 9.84 μM, respectively (Sang et al., 2017). Pleospyrone A (13), Pleospyrone D (14), and Pleospyrone E (15) were extracted as new chlamydosporol derivatives with an α-pyrone motif from the EtOAc extract of endophytic fungus Pleosporales sp. Sigrf05, which was obtained from the healthy tuberous roots of the medicinal plant Siraitia grosvenorii. Pleospyrone A and Pleospyrone E were cytotoxic against HepG2, BGC-823 (gastric cancer), NCI–H1650 (non-small-cell lung carcinoma) and DAOY (medulloblastoma) cell lines in the range of 1.26–20.7 μM of IC50 values, while Pleospyrone D was active against only NCI–H1650 with IC50 of 29.6 μM. Pleospyrone E also possess cytotoxicity against HCT-116 cancer cell line with 1.17 μM of IC50 value, while other compounds remain inactive (Lai et al., 2020). An unprecedented dibenzo-α-pyrone, Rhizopycnin C (16) was separated from culture of endophytic fungus Rhizopycnis vagum Nitaf22 harbored in Nicotiana tabacum. It exhibited cytotoxicity against only A-549 and HCT116 cell lines with IC50s of 25.5 and 37.3 μM, respectively, while remain inactive (IC50 > 50 μM) against human melanoma cell line (A375), MCF-7 and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Capan2) cell lines, which suggests interaction towards specific protein expressed in tumor cells and need to be explored further to find mode of action (Lai et al., 2016). One novel furanodione, Xylarione A (17) was separated from ethyl acetate extract of fermented culture of endophytic fungus Xylaria psidii, harbored in the medicinal plant Aegle marmelos. It showed cytotoxic ability towards MCF-7, pancreatic cancer cells (MIA-Pa-Ca-2), non-small cell lung cancer cells (NCI–H226), HepG2 and prostate carcinoma cells (DU145) with IC50s in the range of 16–25 μM. Detailed in vitro analysis of compound (17) on MIA-Pa-Ca-2 suggested that it showed cytotoxicity due to mitochondrial dependent apoptosis and could be served as compound of interest to studied further evaluation of definite mechanism for its activity (Arora et al., 2016). The structures of pyrones (7–17) are shown in Fig. 2.

2.1.3. Isocoumarins

Isocoumarins are a large group of natural substances that belong to the well-known polyketide family. They are the structural isomer of coumarin and have a wide range of chemical configurations and therapeutic effects (Saddiqa et al., 2017). Four new isocoumarin derivatives, Oryzaeins A–D (18–21) were extracted from solid cultures of fungus Aspergillus oryzae, an endophyte associated with Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. All compounds showed antiproliferative activity towards human tumor cell lines NB4 (human leukemia), A-549, SHSY5Y (human neuroblastoma), PC-3, and/or MCF-7 with IC50s in the range between 2.8 and 8.8 μM (Zhou et al., 2016). Aspergisocoumrin A (22) and Aspergisocoumrin B (23) are new cytotoxic isocoumarin derivatives, which were isolated from the fungus Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D, an endophyte harbored in the leaves of the mangrove plant Acanthus ilicifolius. Compound (22) exhibited cytotoxic activity against human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-435), human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2), lung carcinoma cell line (H460) and non-cancer breast epithelial cells (MCF10A) with IC50 value in the range of 5.08–43.70 μM, while compound (23) showed activity against only MDA-MB-435 and MCF10A cells with IC50s of 4.98 ± 0.74 and 21.40 ± 1.71 μM, respectively and remain inactive against other tested cell lines (Wu et al., 2019). An unprecedented halogenated dihydroisocoumarin, Palmaerone E (24) was separated from SAHA (histone deacetylase inhibitor) exposed fermented culture of fungus Lachnum palmae, an endophyte associated with Przewalskia tangutica. It exhibited weak cytotoxic activity towards only HepG2 cell line with the IC50 value of 42.8 μM, while remain inactive (IC50 > 50 μM) against HL-60 and SGC-7901 (human gastric carcinoma) cells (Zhao et al., 2018a). The structures of isocoumarins (18–24) are shown in Fig. 2.

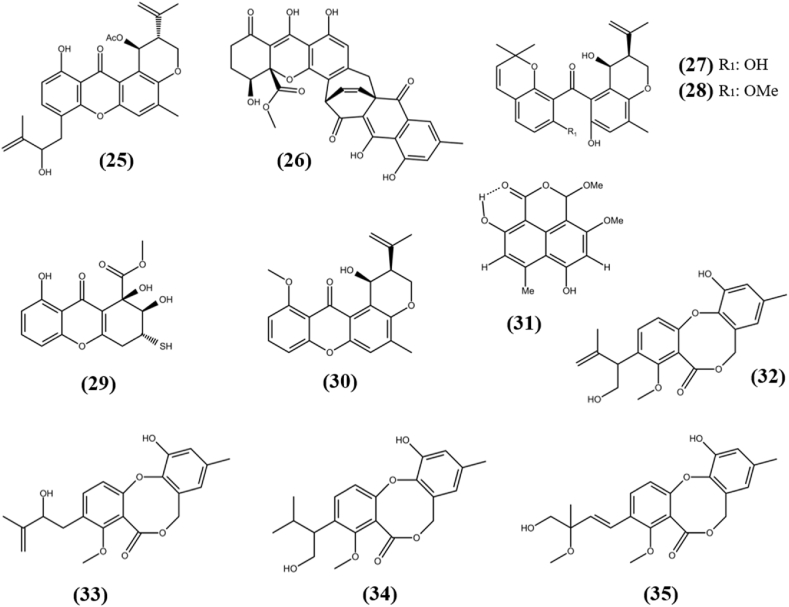

2.1.4. Xanthones

Xanthones are tricyclic secondary metabolites which are derived from dibenzo-pyrone, mainly possess anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties (Bedi et al., 2018b). Asperanthone (25) is a new prenylxanthone derivative, which was obtained from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. TJ23 isolated from traditional chienese medicinal plant Hypericum perforatum L. It exhibited weak cytotoxicity towards HepG2 cell line with IC50 of 35.5 ± 0.06 μM, while remain inactive against B16 (murine), MDA-MB-231, 4T1 (breast cancer) and LLC (Lewis lung carcinoma) cell lines with IC50 > 40 μM (Qiao et al., 2018). A new natural metabolite, Xanthoquinodin B9 (26) was separated from the fermented culture of endophytic fungus Chaetomium globosum 7s-1, harbored in Rhapis cochinchinensis (Lour.) Mart. It showed cytotoxic ability towards the three cancer cell lines (KB, MCF-7, NCI–H187) and normal cell line (Vero cell) with the IC50 values of 7.04, 18.4, 0.98 and 1.78 μM, respectively (Tantapakul et al., 2020). Because Xanthoquinodin B9 does have a lower IC50 value towards NCI–H187 cells than the Vero cells, it requires exploratory research into discovering its mechanism of action. Chryxanthone A (27) and Chryxanthone B (28) were separated from a culture of endophytic fungus Penicillium chrysogenum AD-1540, which was harbored in the marine red alga Grateloupia turuturu. Chryxanthone A possess cytotoxic ability towards A-549, BT-549 (Triple negative breast cancer), HeLa, HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50s of 41.7 ± 1.9, 20.4 ± 1.2, 23.5 ± 0.2, 33.6 ± 1.4 and 46.4 ± 1.2 μM, respectively, while Chryxanthone B possess activity against A-549 and THP-1 (acute monocytic leukemia) cell lines with IC50s of 20.4 ± 0.9 and 41.1 ± 0.5 μM, respectively (Zhao et al., 2018b). The mangrove plant Bruguiera gymnorrhiza derived endophytic fungus Peniophora incarnata Z4 was detected with a new cytotoxic xanthone derivative named Incarxanthone B (29). It exhibited cytotoxicity towards A375 (human melanoma), MCF-7, and HL-60 tumor cell lines with IC50s in the range of 4.9–8.6 μM (Li et al., 2020a). An endophytic fungus Paecilamyces sp. TE-540 was isolated from the leaves of Nicotiana tabacum L., which was collected from China in August 2016. One novel compound with xanthone moiety, Chryxanthone C (30) was separated from the EtOAc crude extract of isolated fungus, which possess cytotoxic ability against only HeLa cell line with IC50 value of 23.6 ± 2.1 μM while remain inactive (IC50s > 100 μM) against other tested A-549, BT-549, HepG2, and MCF-7 cell lines (Li et al., 2020b). The structures of xanthones (25–30) are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of xanthones (25–30), phenalenone (31) and diphenyl ethers (32–35).

2.1.5. Phenalenone

Phenalenones are a special class of fungal metabolites with three-ring systems of hydroxyl-perinaphthenones that have a wide range of biological activities, including anti-HIV, antimicrobial, anti-malarial, and cytotoxic activity (Gombodorj et al., 2017). A new phenalenone analogue, Hispidulone B (31) with naphthalene backbone was isolated from dessert plant associated endophytic fungus Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum. It possess significant cytotoxic ability towards A-549, human hepatoma cell line (Huh7), and HeLa cell lines with IC50s of 2.71 ± 0.08, 22.93 ± 1.61, and 23.94 ± 0.33 μM, respectively, compared to the positive control cis-platinum which had an IC50s of 8.73 ± 1.77, 5.89 ± 0.15, and 14.68 ± 0.10 μM, respectively (Zhang et al., 2020). As the compound had a better cytotoxic ability against particular cancer cell lines than the positive control, it should be investigated further to determine its molecular mechanism to develop it as a new anti-cancer therapeutic agent after thorough pharmacological evaluation. The structure of phenalenone (31) is shown in Fig. 3.

2.1.6. Diphenyl ethers

Prenylated diphenyl ethers have been shown to have antimicrobial, cytotoxic, antioxidant, and antiviral effects on a number of cases (Zhang et al., 2018). Sinopestalotiollides A-D (32–35) are new diphenyl ether derivatives, which were isolated from fermented culture of fungus Pestalotiopsis palmarum, an endophyte harbored in the leaves of medicinal plant Sinomenium acutum (Thunb.) Rehd et Wils. Sinopestalotiollides A-C showed cytotoxic activity against HeLa and HCT116, an A-549 cell lines with IC50s in the range of 12.80–47.82 μM. Sinopestalotiollide D exhibited potent cytotoxic ability towards all tested cell lines with IC50s of 1.19 ± 0.02, 2.66 ± 0.08, and 2.14 ± 0.05 μM, respectively, compared to the known anticancer compound doxorubicin that showed cytotoxicity at 8.96 ± 0.19, 2.38 ± 0.24, and 0.86 ± 0.03 μM, respectively (Xiao et al., 2018). Since Sinopestalotiollide D does have a higher activity against HeLa cells than doxorubicin, it needs to be explored further in order to be developed as an anticancer agent. The structures of diphenyl ethers (32–35) are shown in Fig. 3.

2.1.7. Unclassified polyketide

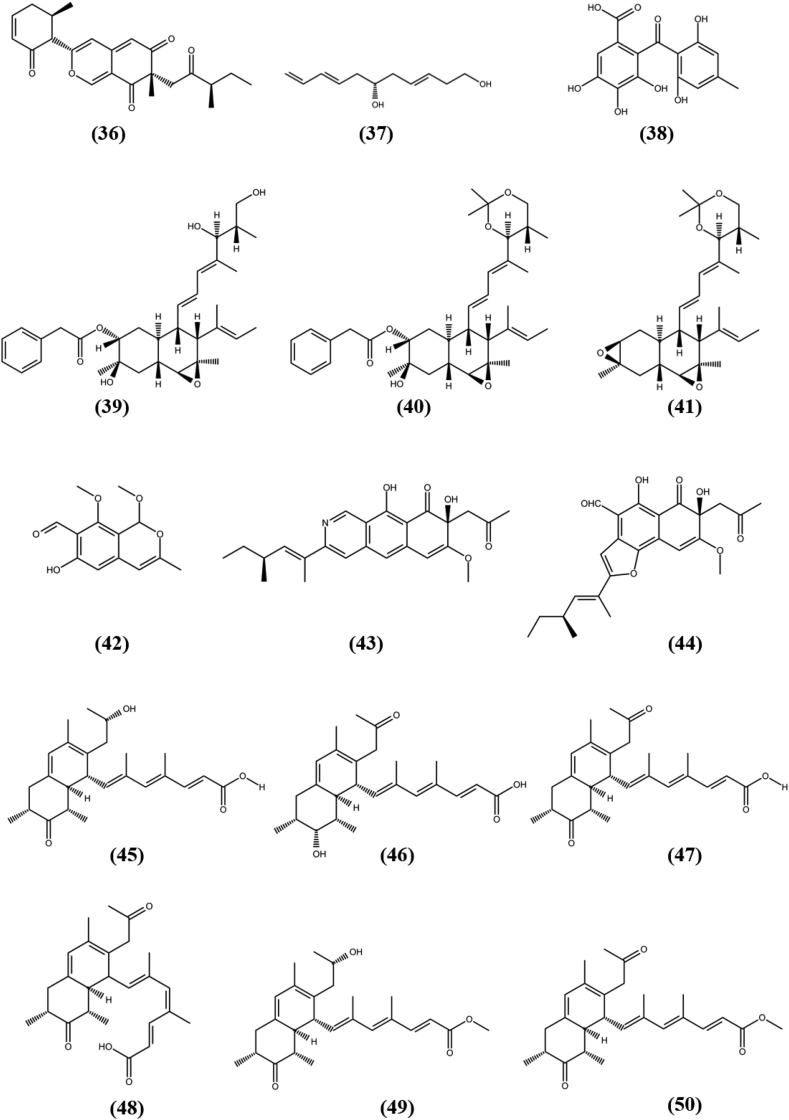

A novel polyketide, Lijiquinone (36), was obtained from fungus Ascomycete sp. F53, an endophyte of the traditional Chinese medicinal plant Taxus yunnanensis (Chinese yew) and exhibited cytotoxicity against human myeloma cells (RPMI-8226) with IC50 value of 129 μM (Cain et al., 2020). (3E,8E,6S)-undeca-3,8,10-triene-1,6-diol (37), a new polyketide was separated from the fermented culture of the fungus Cladosporium sp. OUCMDZ-302, an endophyte harbored in the mangrove plant Excoecaria agallocha. Compound (37) showed antiproliferation activity towards gefitinib resistance non-small cell lung cancer cell line (H1975) with an IC50 values of 10.0 μM, while remain inactive against HL-60, BEL-7402 (hepatoma carcinoma), K562 (chronic myeloid leukemia), A-549 and HeLa cell lines (Wang et al., 2018). Cytosporaphenone A (38), with polyhydric benzophenone moiety was obtained from fungus Cytospora rhizophorae, an endophyte harbored in Morinda officinalis and showed cytotoxic activities against the two cancer cell lines MCF-7 and HepG2 with IC50s of 70 and 60 μM, respectively, while remain inactive against non-small cell lung cancer (NCI–H460) and human central nervous system cancer (SF-268) cell lines (Liu et al., 2017). Three new natural products, Fusarielin J (39), Fusarielin K (40) and Fusarielin L (41), were obtained from the fungal endophyte Fusarium tricinctum, isolated from rhizomes of Aristolochia paucinervis. All isolated compounds displayed cytotoxic activity against the human ovarian cancer cell line (A2780) with IC50 values of 12.5, 36.5 and 84.6 μM, respectively (Hemphill et al., 2017). The endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria sp. F03 was isolated from leaves of Paepalanthus planifolius, collected from Minas Gerais, Brazil. It produced six novel polyketides, one of which, Sporulosaldein F (42) with benzopyran backbone exhibited in vitro cytotoxicity against the LM3 and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 39.2 and 34.4 μM, respectively and remains inactive against murine lung adenocarcinoma (LP07) cell line (IC50 > 100 μM). None of the other novel compounds showed cytotoxicity at the concentrations tested (De Amorim et al., 2019). Peyronetide A (43) is a novel polyketide with benzoisoquinoline-9-one backbone, extracted from endophytic fungus Peyronellaea sp. FT431 along with its derivative Peyronetide B (44). Both the novel polyketide showed antiproliferative ability against three cancer lines A2780S (cisplatin sensitive human ovarian carcinoma), A2780CisR (cisplatin resistant human ovarian carcinoma), and TK-10 (human kidney adenocarcinoma) with IC50 values between 21.5 ± 0.3 and 29.2 ± 2.9 μM in CyQuant cell proliferation assay (Li et al., 2019b). Six new bicyclic polyketides, Preussilides A−F (45–50), were obtained from the fermented culture of endophytic fungi Preussia similis harbored in medicinal plant Globularia alypum, which was collected in Batna, Algeria. All isolated preussilides exhibited antiproliferative activity against either some or all tested cell lines L929, KB3.1, A431, A-549, SKOV-3 (ovarian cancer), PC-3, MCF-7 and U2OS with IC50 values in the range of 2.5–80 μM (Noumeur et al., 2017). Selective cytotoxicity of Preussilide A and Preussilide C and influence on the morphology of human osteosarcoma cells (U2OS) suggest that these two compounds might affects the cell division process and more research is needed to determine the molecular mechanism. The structures of unclassified polyketides (36–50) are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Chemical structures of unclassified polyketides (36–50).

2.2. Terpenoids

Terpenoids are a class of natural bioactive substances which have isoprene as a scaffold and are found in a wide range of organisms. Many terpenoids are studied for anticancer activity, antimicrobial activities, lethal toxicity, anti-inflammatory action, enzyme inhibitor activity, and other biological activities (Jiang et al., 2020). Herein, 40 terpenoids are divided into four categories: meroterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoid, and triterpenoids.

2.2.1. Meroterpenoids

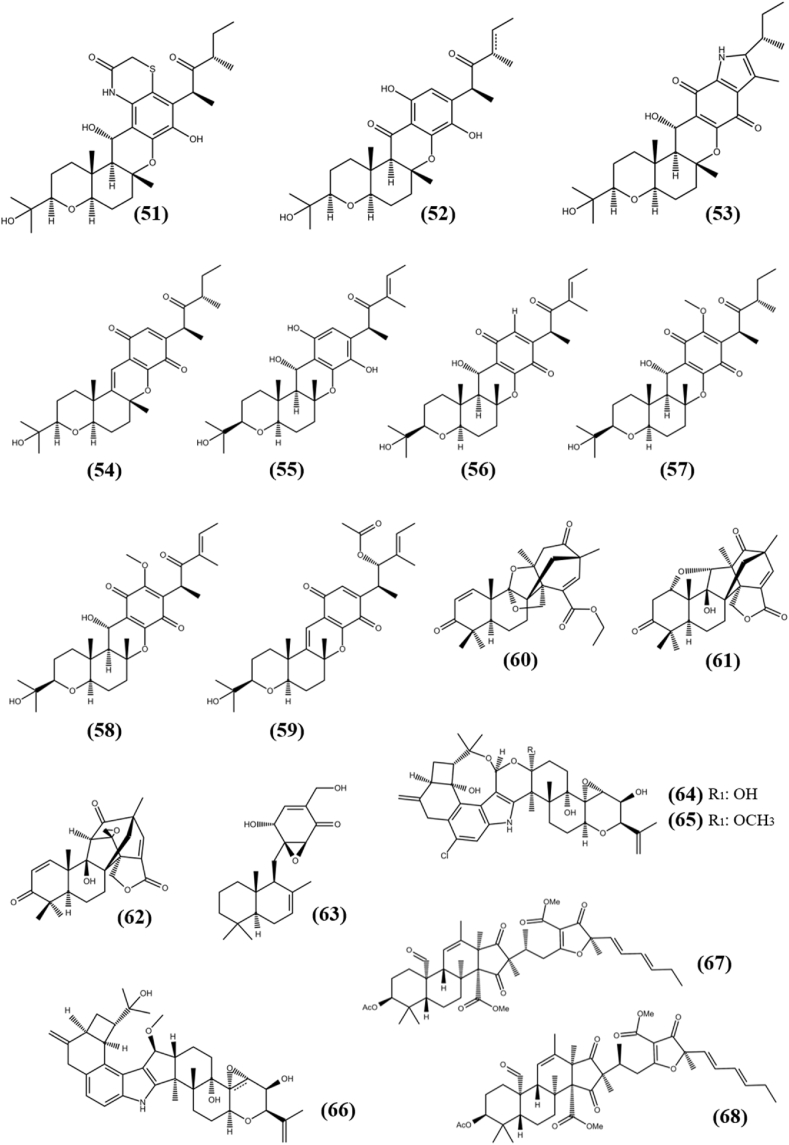

A chemical compound with a partial terpenoid structure is known as a meroterpenoid. Four new meroterpenoids, Isocochlioquinones D-E (51–52) and Cochlioquinones G-H (53–54) were separated from EtOAc extract of fungus Bipolaris sorokiniana A606, an endophyte associated with the medicinal plant Pogostemon cablin. All compounds possess antiproliferative activity against SF-268, MCF-7, NCI–H460 and HepG2 tumor cell lines with the IC50s between 6.4 ± 0.2 and 42.6 ± 2.5 μM (Wang et al., 2016). An endophytic fungus Bipolaris sp. L1-2 was isolated from leaves of the Lycium barbarum, which were collected from Ningxia Province, China. Ethyl acetate extract of fermented fungus, detected with eleven new meroterpenoids, including Bipolahydroquinone C (55), Cochlioquinones I (56), K (57), L (58) and M (59), which have cytotoxic activity in the range of 5.6–9.5 μM of IC50s against MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line (Long et al., 2019). Bipolahydroquinone C was also found to be cytotoxic against the NCI–H226 cancer cell line, with an IC50 of 5.5 μM, making it an appealing molecule for further scientific research as a chemotherapeutics for lung cancer treatment. A series of 3,5-demethylorsellinic acid-based meroterpenoids including Emeridone B (60), Emeridone D (61) and Emeridone F (62) were separated from EtOAc extract of fungus Emericella sp. TJ29, an endophyte associated with the plant Hypericum perforatum. All three compounds possess cytotoxic activity against two cancer cell lines SMMC-7721 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and SW-480 (colon cancer) with IC50s in the range of 8.19–18.80 μM. Emeridone D also showed antiproliferative activity to A-549 with IC50 value of 11.33 ± 0.82 μM, while other compounds remain inactive against tested cell lines (Li et al., 2019c). The new meroterpenoid, 11-dehydroxy epoxyphomalin A (63) with epoxyphomalin backbone was extracted from fermented culture of fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238, an endophyte associated with the native Hawaiian plant Pritchardia lowreyana. It showed antiproliferative activity against panel of tumor cell lines MCF-7, MDA468, MDA-MB-231, T24 (human urinary bladder carcinoma), OVCAR5, OVCAR4, OVCAR3 (epithelial carcinoma), IGROV-1/Pt (drug-resistant ovarian carcinoma), A2780 CisR and A2780 with IC50s of 2, 1.3, 2.2, 1.8, 1.8, 1.4, 0.5, 1.6, 0.6 and 0.8 μM, respectively (Li et al., 2016). Rhizovarin A (64), Rhizovarin B (65) and Rhizovarin F (66) with cytotoxic ability were extracted from Mucor irregularis QEN-189, an endophyte associated with marine mangrove plant Rhizophora stylosa. Compound (64) and (65) showed cytotoxic activity towards HL-60 and A-549 tumor cell lines with IC50s of 11.5, 9.6 μM and 6.3, 5 μM, respectively, while compound (66) showed activity against only A-549 cells with IC50 value of 9.2 μM and remain inactive (IC50 > 10 μM) against HL-60 cells (Gao et al., 2016). Two novel meroterpenoids, Isopenicin A (67) and Isopenicin B (68) with unprecedented hybrid skeleton of polyketide-terpenoid moiety were obtained from fermented culture of endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. sh18, which was harbored in fresh stems of Isodon eriocalyx var. laxiflora. Both the compounds possess cytotoxic ability against several cancer cell lines SW480, SW620, HCT116, CaCo2 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma), SMMC-7721 (human hepatocellular carcinoma), A-549 and MCF-7 with the IC50s of 7.91 ± 0.53, 8.63 ± 0.15, 9.03 ± 0.61, 12.56 ± 0.91, 27.66 ± 0.88, 37.06 ± 2.24, 27.89 ± 0.70 μM and 11.60 ± 0.18, 15.48 ± 1.39, 14.95 ± 0.22, 20.34 ± 0.25, 33.49 ± 0.17, >40, 33.05 ± 0.19 μM, respectively (Tang et al., 2019). Detailed analysis of both compounds on human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293), SW620, and HCT116 cells revealed that they selectively suppress the Wnt pathway in colon cancer cells. However, more research and in vivo experiments are essential before it could be termed an effective anticancer compound. The structures of meroterpenoid (51–68) are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Chemical structures of meroterpenoids (36–50).

2.2.2. Sesquiterpenoids

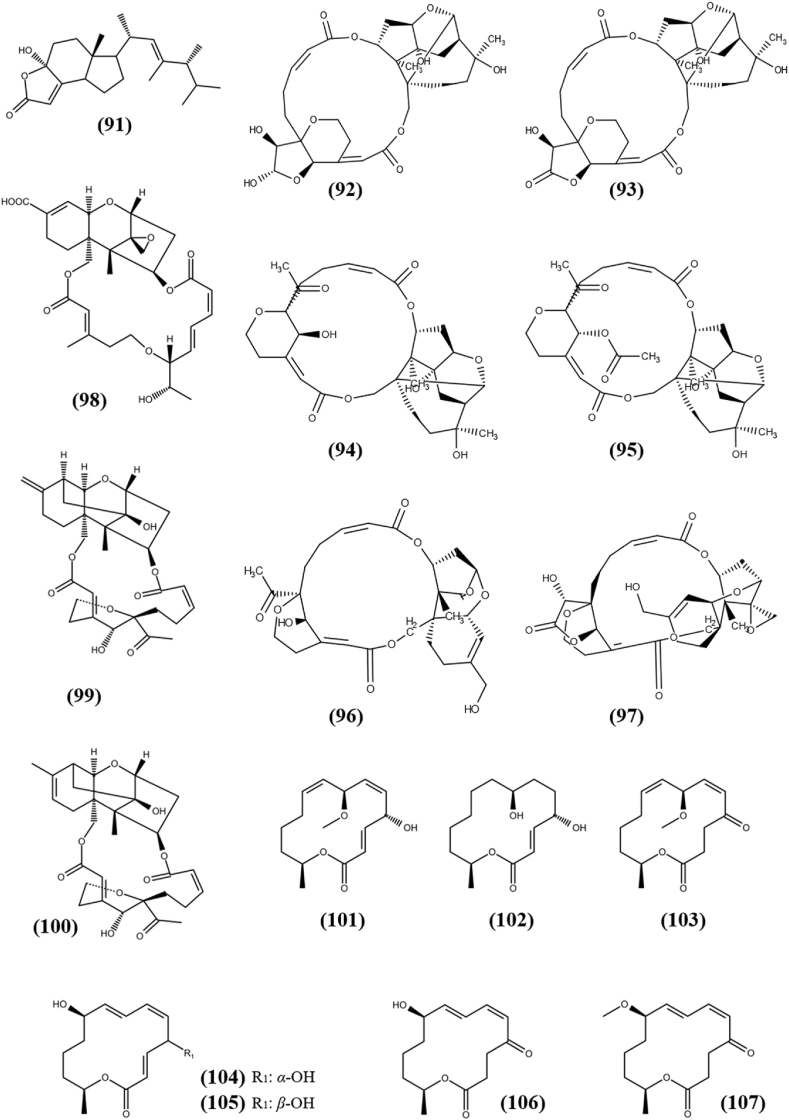

Sesquiterpenoids are a class of compounds that contain 15 carbon atoms and are made up of three isoprene units. Two novel sesquiterpenes named, Fumagillene A (69) and Fumagillene B (70) were separated from EtOAc extract of endophytic fungi Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from the root of Ligusticum wallichii. Compound (69) exhibited cytotoxicity against MDA-ME-231 and MV4-11 cancer cell lines with IC50s of 8.4 ± 2.9 and 4.3 ± 5.8 μg/ml, while compound (70) showed activity at 11.2 ± 3.6 and 17.3 ± 6.4 μg/ml respectively (Li et al., 2020c). Proversilin C (71) and Proversilin E (72) are unprecedented drimane-type sesquiterpenoids which were obtained from fungi Aspergillus versicolor F210, an endophyte associated with Lycoris radiata. Both the compounds showed antiproliferation activity against HL-60, SMMC-7721, A-549, MCF-7 and SW-480 cells with IC50s of 7.3 ± 1.2, 12.6 ± 0.9, 15.0 ± 0.8, 11.8 ± 0.5, 12.4 ± 0.4 μM and 9.9 ± 1.4, 19.4 ± 0.7, 28.4 ± 1.2, 18.3 ± 1.2, 16.4 ± 1.0 μM respectively, while remain inactive against normal colonic epithelial cells (NCM460) with IC50 of >40 μM (Li et al., 2020d). Two new eremophilane sesquiterpenes, Lithocarin B (73) and Lithocarin C (74) have been extracted along with two more new metabolites from EtOAc extract of fungus Diaporthe lithocarpus A740, an endophyte associated with medicinal plant Morinda officinalis. Lithocarin B and Lithocarin C showed weak antiproliferative activity against three cancer cell lines, SF-268, MCF-7, HepG2 in the range of 37 and 97.71 μM of IC50 values compared to known anticancer molecule, cisplatin which exhibited activity at 3.39 ± 0.29, 3.19 ± 0.12 and 2.42 ± 0.14 μM, respectively. Other compounds remain inactive against all tested cell lines at IC50s of >100 μM (Liu et al., 2019a). (R,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (75) and (S,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4- methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (76) are two novel nor-sesquiterpenoids obtained from endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum, associated with the root of Ligusticum chuanxiong. Among these, compound (75) displayed cytotoxicity against MV4-11, HCT116, MCF-7 and A-549 cancer cell lines with an IC50 values between 22.29 and 93.47 μM, while compound (76) exhibited cytotoxicity against only MV4-11 and MCF-7 cells with an IC50 value of 70.2 and 81.21 μM, respectively (Cao et al., 2020). Two new polyoxygenated eremophilane sesquiterpenes, Periconianone E (77) and Periconianone H (78) were obtained from EtOAc extract of endophytic fungus Periconia sp. F-31, which was isolated from Annona muricata. Compound (77) showed cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells with IC50 value of 17.9 μM, while compound (78) exhibited cytotoxic activity against HeLa cell line with IC50 of 16.5 μM (Liu et al., 2016a). The crude extract of the fungus Pestalotiopsis theae, an endophyte isolated from Camellia sinensis in Hangzhou, China, contains three new compounds including two caryophyllene-type sesquiterpenoids, Pestathenol A (79) and Pestathenol B (80). Both the compounds exhibited weak cytotoxicity against HeLa cell line, with IC50 values of 78.2 and 88.4 μM, respectively, compared to positive control cisplatin which possess IC50 value of 21.1 μM (Guo et al., 2020). Two new cytotoxic sesquiterpenoid derivatives, Rhinomilisin A (81) and Rhinomilisin G (82) were extracted from the culture of fungus Rhinocladiella similis, which was isolated from the leaves of mangrove fern Acrostichums aureum. Both the compounds showed cytotoxic ability towards mouse lymphoma cell line (L5178Y) with IC50 value of 5 and 8.7 μM, respectively (Liu et al., 2019b). Merulinol C (83) and Merulinol D (84) are two new chamigrane sesquiterpenes, which were separated from the EtOAc extract of the fungus XG8D of basidiomycetes phyla, harbored in the healthy leaves of Thai mangrove Xylocarpus granatum. Both the compound showed cytotoxicity against KATO-3 cells with IC50s of 35.0 ± 1.20 and 25.3 ± 0.82 μM, respectively, while remain inactive against MCF-7 and HepG2 cell lines with IC50s of >50 μM (Choodej et al., 2016). Cerrenin D (85), a triquinane-type sesquiterpene had been isolated from endophytic fungus Cerrena sp. A593, which was harbored in Pogostemon cablin and possess weak antiproliferative activity against four cancer cell lines SF-268, MCF-7, NCI–H460 and HepG2 with IC50s of 41.01 ± 0.34, 14.34 ± 0.45, 29.67 ± 0.81, and 44.32 ± 2.12 μM, respectively (Liu et al., 2020a). Two unprecedented fungal sesquiterpenoids, 7-epi-merulin B (86) and 3-epi-merulin A (87) were separated from the culture of Pseudolagarobasidium acaciicola, an endophyte associated with mangrove plant Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Compound (86) exhibited cytotoxicity against HuCCA-1 (human lung cholangiocarcinoma), A-549, MOLT-3 (T-lymphoblast), HepG2, HL-60, MDA-MB231, T47D (human mammary adenocarcinoma) and MRC-5 (normal human embryonic lung) cell lines with IC50 values of 37.46 ± 3.77, 24.75 ± 1.09, 2.39 ± 0.95, 8.91 ± 3.13, 0.28 ± 0.18, 12.22 ± 9.26, 22.25 ± 3.35 and 17.92 ± 4.58 μM, respectively, while compound (87) was active towards only MOLT-3, HepG2, HL-60 and MRC-5 cell lines with IC50s of 17.28 ± 3.66, 20.71 ± 3.50, 12.09 ± 3.50 and 17.83 ± 2.72 μM, respectively (Wibowo et al., 2016). The structures of meroterpenoid (69–87) are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Chemical structures of sesquiterpenoids (69–87), diterpenoid (88), and triterpenoids (89–90).

2.2.3. Diterpenoid

Diterpenoids are a substantial class of terpenoids that has a wide range of structures and bioactivities. A novel compound (10S)-12,16-epoxy-17(15 → 16)-abeo-3,5,8,12,15-abietapentaen-2,7,11,14-tetraone (88) with diterpenoid backbone was separated from the culture of endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis adusta, obtained from the medicinal plant Clerodendrum canescens. It showed antiproliferative activity against HL-60 cancer cell line with IC50 of 12.54 ± 1.18 μM (Xu et al., 2016). The structure of diterpenoid (88) is shown in Fig. 6.

2.2.4. Triterpenoids

Triterpenoids are a group of chemical compounds composed of three terpene units that have a versatile chemistry and pharmacology and contain several pentacyclic motifs. Three new tetracyclic triterpenoids, including Integracide H (89) and Integracide J (90) were separated from the fermented culture of endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. associated with Mentha longifolia L. Both the compounds showed strong cytotoxicity towards BT-549, SKOV-3 and KB cell lines with IC50s of 1.82, 1.32, 0.18 μM and 2.46, 3.01, 2.54 μM, respectively, compared to positive control doxorubicin (2.78, 0.16 and 0.41 μM). However, both the compounds remain inactive against SKOV-3 cell line, while other compound remain inactive against all tested cell lines (Ibrahim et al., 2016a). The structures of triterpenoids (89–90) are shown in Fig. 6.

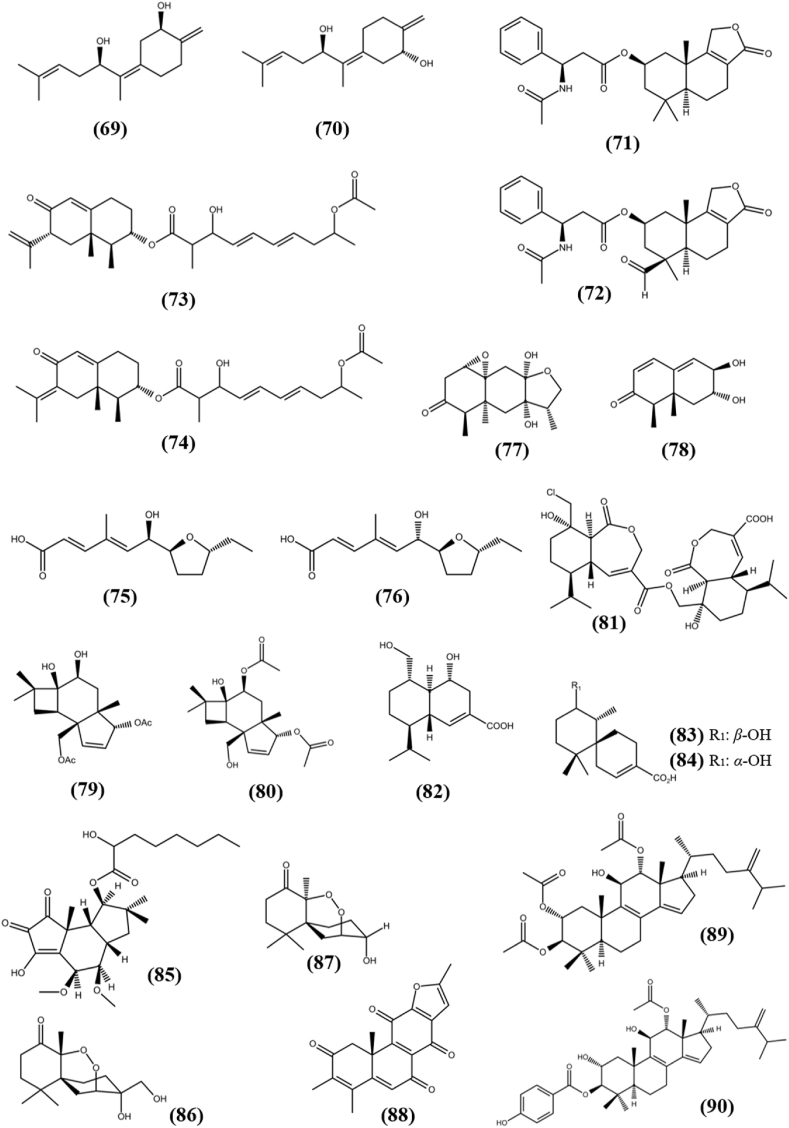

2.3. Steroid

Steroids are a class of fungal metabolites with a wide range of chemical structures and biological functions. Many researchers are currently looking for steroidal metabolites to use as potential lead compounds in drug development (Ur Rahman et al., 2017). A new compound, Demethylincisterol A5 (91) with sterol moiety was separated from the rice fermented culture of endophytic fungus Aspergillus tubingensis YP-2, which was isolated from traditional Chinese medicinal plant Taxus yunnanensis. It showed weak cytotoxicity towards A-549 and HepG2 cells with the IC50s of 11.05 and 19.15 μM, respectively, compared to positive control Doxorubicin, which had an IC50s of 0.94 and 1.16 μM, respectively (Yu et al., 2019). The structure of steroid (91) is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Chemical structures of Steroid (91) and macrolides (92–107).

2.4. Macrolides

The macrolides are a group of natural products that are made up of a large macrocyclic lactone ring with one or more deoxy sugars attached and have a wide range of biological activities, including antiparasitic, antifungal, and antimalarial properties (Karpiński, 2019). Myrothecines D-G (92–95), 16-hydroxymytoxin B (96), and 14′-dehydrovertisporin (97) are six unprecedented macrolides, which were obtained from endophytic fungus Myrothecium roridum, associated with Trachelospermum jasminoides (Lindl.) Lem. All compounds possess cytotoxic ability against two tumor cell lines K562 (chronic myeloid leukemia) and SW1116 (colorectal carcinoma) between 0.056 and 15.98 μM of IC50 values. A three-dimensional quantitative structure activity relationship (3D QSAR) analysis suggested that the cytotoxicity of these trichothecene macrolides at nanomolar to micromolar level is dependent on steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and H-bond accepting pharmacophore group present in them (Shen et al., 2019). Moreover, additional research could be useful in developing these fungal metabolites as anticancer agents with specific molecular mechanism. A macrolide molecule consists of sesquiterpenoid with a diacyl residue anchored at the 4β and 15 positions, named Epiroridin acid (98) was separated from fermented culture of fungus Myrothecium roridum A553, an endophyte harbored in the medicinal plant Pogostemon cablin. It exhibited strong cytotoxic capability against SF-268, MCF-7, NCI–H460, and HepG2 cell lines with IC50s of 0.751 ± 0.03, 0.170 ± 0.01, 0.360 ± 0.05 and 0.380 ± 0.03 μM, respectively, compared to positive control cisplatin, which showed activity with IC50s of 4.060 ± 0.16, 2.850 ± 0.45, 2.850 ± 0.15 and 2.470 ± 0.17 μM, respectively (Liu et al., 2016b). The fact that Epiroridin acid has lower IC50 values than the positive control signals that more in vitro investigations such as apoptosis, cell cycle-based studies, and so on, is needed to determine its mechanism of action. Two new trichothecene macrolides, named Myrothecine H (99) and Myrothecine I (100) were extracted from the culture of endophytic fungus Paramyrothecium roridum, associated with the medicinal plant Morinda officinalis. Both the compounds showed strong cytotoxicity towards SF-268 and HepG2 cell lines with IC50s of 6.75 ± 0.22, 6.72 ± 0.27 μM and 0.20 ± 0.01, 0.20 ± 0.03 μM, respectively (Liu et al., 2020b). 7-O-Methylnigrosporolide (101) and Pestalotioprolide C–H (102–107) are 14-membered macrolides, which were separated from the culture of Pestalotiopsis microspora, an endophytic fungus associated with mangrove Drepanocarpus lunatus. All compounds possess cytotoxic ability against murine lymphoma cell line L5178Y and/or A2780 with IC50s between 1.2 and 39 μM (Liu et al., 2016c). The structures of macrolides (92–107) are shown in Fig. 7.

2.5. Lactones

Lactones are cyclic esters, which consist of a ring of two or more carbon atoms and a single oxygen atom with a ketone group next to one of the carbons. Lactones are used in the flavors and fragrances industry, and they also possess antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties (Robinson et al., 2019). Two new compounds, Asperlactone G (108) and Asperlactone H (109) were separated from ethyl acetate extract of an endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp., associated with Pinellia ternate. Both the compounds showed weak cytotoxicity towards A-549 cells with IC50s of 65.3 ± 1.06 and 23.3 ± 2.01 μM, respectively, while remain inactive against MCF-7/DOX cell line at IC50 of >100 μM (Xin et al., 2019). Four new compounds including a pair of butanolide derivatives, (−)-asperteretone F (110) and (+)-asperteretone F (111), were obtained from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus, associated with Hypericum perforatum. Compounds (110) and (111) exhibited cytotoxic activity against human pancreatic cancer cells AsPC-1, SW1990 and PANC-1 cell line with IC50 values of 9.5, 11.7, 9.8 μM and 9.9, 10.3, 15.6 μM, respectively. Both the compounds remain inactive against HeLa and SW480 cancer cell lines, while other compounds were inactive against all tested cell lines (Deng et al., 2020). Hispidulactone F (112), a novel metabolite was separated from the EtOAc extract of dessert plant associated endophytic fungus Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum (TS-8-1) and showed antiproliferative activity against HepG2 cells with IC50 of 61.05 μM by the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Zheng et al., 2020). The structures of lactones (108–112) are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Chemical structures of lactones (108–112) and azaphilones (113–118).

2.6. Azaphilones