Abstract

Chemotherapy is an important component of cancer treatment, which has side effects like vomiting, peripheral neuropathy, and numerous organ toxicity but the most significant outcomes of chemotherapy are cognitive impairment, which is mainly referred to as chemobrain or CICI (chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment). It is characterized by difficulty with language, concentrating, processing speed, learning, and memory, as it affects the hippocampus areas of the brain. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are one of the major mechanisms causing chemobrain. The generation of reactive oxygen species (byproducts of oxidative phosphorylation) mainly occurs in mitochondria that play a prominent role in the induction of oxidative stress. The homeostasis of ROS in the mitochondria is maintained by mitochondrial antioxidant mechanism via enzymes like catalase, glutathione, and superoxide dismutase. Lungs and breast cancer are the two most common types of cancer, which are the most leading cancers in the world with about 4.18 million cases. In this review we exposed the current knowledge regarding chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction to cause cognitive impairment.We especially focused on the antineoplastic agent (ADRIAMYCIN, CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE), platinum group agent CISPLATIN, antimetabolite agents (METHOTREXATE), and nitrogen mustard agent (CARMUSTINE) which increase oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in the PNS (peripheral nervous system) as well as the central nervous system. We also highlight the behavioural and functional changes in the brain.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Cognitive impairment, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Oxidative stress, Chemobrain, Reactive oxygen species

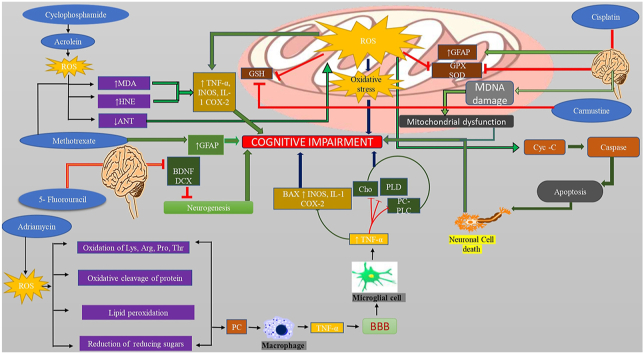

Graphical abstract

Chemotherapeutic agent like cyclophosphamide causes ROS production with increasing HNE protein and cytokines level resulting in cognitive impairment. Adriamycin increases ROS generation, oxidation of amino acid, protein, and lipid peroxidation leading to protein carbonyl formation, activation of the microglial cell which release TNF-α, cross BBB that decreases choline, PLC, AND PC-PLD level and increase cytokine level causes cognitive impairment. Chemotherapeutic agents also increase GFAP level and inhibit the Gpx as well as glutathione level. 5- fluorouracil inhibit the BDNF and DCX levels leads to decrease neurogenesis resulting in cognitive impairment. Carmustine decreases the GSH level. Chemotherapy agent disrupts the mitochondrial chain complex and releases cytochrome -C leads to caspase activation cause apoptosis results in neuronal damage to induce cognitive impairment.

Highlights

-

•

Chemotherapy alters brain functions and behavioural activities.

-

•

Providing theoretical and diagrammatic knowledge of chemobrain mechanisms.

-

•

Introducing new targets involved in the development of chemobrain.

-

•

Provide information on mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress as causes of chemobrain.

List of abbreviation

- GPX1

= Glutathione peroxidase

- PRDX1

= Peroxiredoxin-1

- HO-1

= Heme oxygenase 1

- ANT

= Adenine nucleotide translocase

- MDA

= Malonaldehyde

- 4-HNE

= 4- Hydroxynonel

- ADR

= Adriamycin

- PLD

= Phospholipase D

- CDDP(II)

= Cis-diamminedichloridoplatinum (II)

- AChE

= Acetylcholinesterase

- GFAP

= Glial fibrillar acid protein

- PC-PLC

= Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C

- GR

= Glutathione reductase

- DIC

= Dicarboxylate transporter

- OGC

= 2-oxoglutarate transporter

- BDNF

= Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DCX

= Doublecortin

- CSF

= Cerebrospinal fluid

- ATP

= Adenosine triphosphate

1. Introduction

Anti-cancer drugs are a crucial part of cancer treatment, as it has increased the survival rate of patients, but the major complications of anticancer drugs are cognitive impairment in the central nervous system (CNS). An anticancer agent has been reported to cause cognitive impairment, which is referred to as chemobrain. Chemobrain (also known as CICI chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment) was first described in 1980 by Dr. Peter Silberfarb and colleagues. Chemobrain is referred to as troubling in language, concentration, acceleration, learning, and recognition (Wigmore, 2012; Li et al., 2013; Monje and Dietrich, 2012; Dietrich, 2010; Silberfarb et al., 1980). During or shortly after treatment, chemotherapy can cause cognitive impairment or late CRCI (chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment) can occur late in the course of the disease (Koppelmans et al., 2012). CICI increases the prevalence of cognition with an increased survival rate and the incidence of chemobrain in about 17–75% of patients receiving chemotherapy (Wefel et al., 2004). After initiating chemotherapy, about 18%–78% of breast cancer patients report cognitive dysfunction (Ahles et al., 2012; Cull et al., 1996). The Study of the American Cancer Society revealed that more than 15 million cancer survivors are currently living in the United States. According to the data given in 2016, there will be a possibility of a rise in the numbers to 20.3 million by 2026 (Miller et al., 2016). Mitochondrion is the powerhouse of the cell which has a prominent role in the generation of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) in all eukaryotecells. It also plays an essential role in membrane biogenesis by synthesizing heme, phospholipids, and amino acids (Rizzuto et al., 2012). Mitochondria have the ability to transmit energy over an extended distance to meet the high energy demands of neurons and synapses. It also shows the fuse and split mechanism (Celsi et al., 2009). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl (OH−), and superoxide radicals (O2−), which are the major endogenous components of mitochondria and are mostly produced via oxidative phosphorylation, which is maintained by anti-oxidative enzymes like glutathione (GSH), catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxiredoxin (Liu et al., 2002). The natural homeostasis mechanism of the cell is to preserve, the equilibrium between the generation and neutralization process of ROS by endogenous cellular defence mechanisms (Dröge, 2002). The inadequate availability of antioxidants and imbalance in ROS homeostasis contribute to the neurons transferring near the free radical attack that leads to oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, disruption of the cell division pathway, and apoptosis, and ultimately results in cognitive dysfunction (Lin and Beal, 2006; Kimura et al., 2006; Wadhwa et al., 2018). The normal functioning of the mitochondria is affected by chemotherapy by a mechanism that directly inhibits the respiratory chain in the brain and other organs of the body (Mattson and Magnus, 2006; Cardoso et al., 2008; Kruidering et al., 1997). Around half of the Food and Drug administration (FDA) approved anticancer drugs result in the progression of ROS that leads to induced oxidative stress (Chen et al., 2007). Adriamycin is one of the quinines containing an anthracycline chemotherapeutic agent that does not cross the Blood-brain barrier (BBB) but it has the potential to produce reactive oxygen species in normal tissue (Cummings et al., 1991; Bigotte and Olsson, 1982; Besedovsky and del Rey, 1996; Singal et al., 2000; Kalyanaraman et al., 2002; Joshi et al., 2005). Administration of Adriamycin increases the level of TNF-α peripherally and crosses the BBB by active or passive transport, which activates microglia and nerve cells to increase the TNF-α expressions that causes oxidative stress, neuronal damage, and tissue injury. The particular mechanism for the CICI is unclear, but numerous mechanisms have been elaborated to cause the straightway of neurotoxicity induced by chemotherapeutic drugs, the genetic tendency of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), oxidative damage, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, immune dysregulation, and condensed telomeres (Sternberg, 1997; Madrigal et al., 2002; Perry et al., 2002; Szelenyi, 2001). In this review, we have discussed mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress causing chemobrain and understand the pathological condition of CICI.

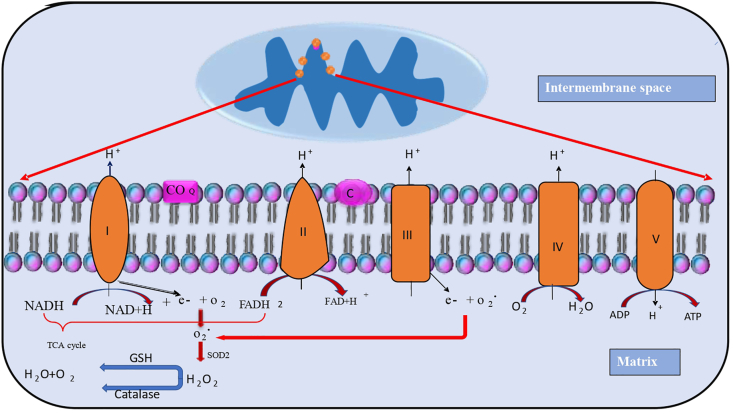

2. Mitochondria and oxidative stress

Reactive oxygen species are produced by various biological compartments. Although mitochondria are the major source of reactive oxygen species, they also have capacity to generate free radicals using various substrates.This ability of the mitochondria may be liable to the membrane composition. The reactive oxygen species are generated by mitochondrial complexes I, II, and III which are parts of the respiratory chain complexes (Balaban et al., 2005; Lenaz, 2001; Brand, 2010). The electrons are generated by mitochondrial complexes. Basically, unpaired electrons are generated by oxidative phosphorylation, which interacts with oxygen and causes the generation of superoxide ions. The superoxide ions are changed into H2O2 and OH-reactive oxygen species (Duchen, 2004). Mitochondrial complexes - I (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase) is a major place for the production of ROS via the transfer of an electron to the NADH reductase and in the case of chemotherapy, this production of ROS occurs abnormally which leads to oxidative stress (Bolisetty and Jaimes, 2013; Warnau et al., 2018). The functional damage of the enzyme (succinate dehydrogenase) causes succinate accumulation that leads to ROS production in the cell (Ralph et al., 2011). The low level of superoxide anion is also generated by the mitochondrial complex-II enzyme via reduction of CoQ (McLennan and Degli Esposti, 2000; Fato et al., 2008; Murphy, 2009; Yankovskaya et al., 2003). Harman's theory states that the continuing free radical accumulation in the cell is the main cause of oxidative damage to the amino acids, phospholipids, and DNA. The elevation of ROS, induces cellular damage, especially in neurons and glial cells leading to neuronal damage or apoptosis (Gilgun-Sherki et al., 2001). Tangpong et al., in 2006 state that the systemic administration of Adriamycin declines mitochondrial respiration, via disruption of complex I enzyme (NAPH CoQ reductase) that releases cytochrome c, which will increase caspase activity, results in mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death (Fig. 1) (Tangpong et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

ROS generation and antioxidant defence in mitochondria. Mitochondria is the cell organelles that are the main sites for ROS production especially in mitochondrial complex I (also called NADH) act as coenzyme Q reductase and complex II called FADH2 (succinate dehydrogenase) and the reduced molecules of NADH and FADH2 donates electrons to the respiratory chain present in the inner membrane of mitochondria. The electrons are leaked to form superoxide which is dismutated by superoxide dismutase (SOD2) in the inner mitochondrial membrane to form hydrogen peroxide. Later, the antioxidant enzyme catalase and glutathione reduced the hydrogen peroxide to form a molecule of water and oxygen.

3. Defense of mitochondria against oxidative stress

Mitochondria are the organelles that generate 90 percent of cellular ATP. The function of mitochondria is especially important in nerve cells specified for ATP generation. Neurons are specific cells that require higher energy to support the activities of the cell, especially in the synaptic region (Nicholls and Budd, 2000). Mitochondria can undergo a fusion/fission mechanism to adapt to the environment. The fusion/fission cycle involves sharing organelle content to replace damaged or lost components (Celsi et al., 2009). Mitochondria have a prominent role in ATP generation, which is important for the proper functioning of the cell.

Mitochondria are the main site for ROS production, which is involved normally under physiological conditions. It is mainly produced at the site of mitochondrial enzyme complexes I and III in the respiratory chain of mitochondria. Some studies have reported that the mitochondrial complexes II are also involved in ROS production (Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Chiswick and Miller, 2015; Quinlan et al., 2012). The superoxide ion is a primary free radical that is produced by an electron transport chain that undergoes ROS generation like H202 via SOD2. This elevated level of ROS is harmful to various bio molecules like enzymes, proteins, and nucleic acids. This ROS production is neutralized by the oxidant defense (Pichaud et al., 2013). During the production of ROS, cells develop some protective enzymes including catalase, SOD, glutathione, and glutathione peroxidase (Radi et al., 1991).

3.1. Superoxide dismutase

The mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme, SOD converts oxygen free radicals into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). According to the Lu et al. report, the main source of oxidative damage is an elevated level of SOD1/2 (Lu et al., 2009).

3.2. Catalase

Catalase is one of the most important antioxidants which has an important role in the degradation of H2O2. The decline in antioxidant levels is harmful to mitochondria because catalase functions as a protection of mitochondria from oxidative stress, but the catalase declines, that may induce an accumulation of H2O2 that causes oxidative stress in the cell (Nohl and Hegner, 1978).

3.3. GSH and GSH reductase

GSH also referred to as glutathione, is an intracellular thiol compound that acts as a defense against ROS and electrophiles (Pronk et al., 1990). GSH is mainly present in mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the nucleus in a reduced form that regulates the normal functioning of cell-like protection, proliferation, and growth of mitochondria (Marí et al., 2009; Mari et al., 2010; Griffith and Meister, 1985; Garcia-Ruiz et al., 1994).

4. Chemotherapy associated cognitive impairment via mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the brain

Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is also known as “chemobrain” or “chemofog” (Cleeland et al., 2003). Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is seen in a patient by altering brain structure and cognitive function (Ahles and Saykin, 2007). Recent studies as reported that some chemotherapeutic drug-like Adriamycin, does not cross the BBB, but some chemotherapeutic agent like methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, and cyclophosphamide crosses the BBB. After the administration of chemotherapy, the levels of various inflammatory cytokines were upregulated in hippocampal regions. This includes IL-6, TNF-α which damages neuronal transmission in the synaptic regions, which alters the cholinesterase expression that leads to cognitive impairment. For the Mitochondrial function assessment, the level of antioxidants like catalase, MnSOD, and GPX is important for normal functioning, but with the administration of chemotherapy, this level of the above enzyme alters that result in chemobrain (Verstappen et al., 2003; Troy et al., 2000; Briones and Woods, 2011).

According to the El-Agamy et al., 2018 study, it is reported that upregulation of acetylcholinesterase activity in the hippocampus region of the brain after the ADR treatment (El-Agamy et al., 2018). Bagnall-Moreau et al., 2019 proved that after the administration of chemotherapy AC (Adriamycin and cyclophosphamide) in the combination shown the reduced level of antioxidant include GPX1 (glutathione peroxidase 1), PRDX1 (peroxiredoxin-1), and the level of HO-1 (heme oxygenase 1)by using RT-qPCR analysis, further they shown the elevated ERK/MAPK Signalling in the hippocampus which causes the oxidative damage. This damage activates the microglia to release proinflammatory cytokines like IL2, IL16, IL-10, and TNF-αleads to neuronal damage and affects cognitive functions (Briones and Woods, 2011).

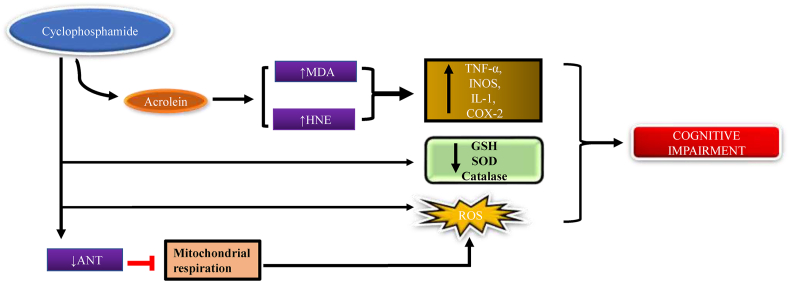

4.1. Cyclophosphamide

The chemotherapeutic drug, cyclophosphamide is a class of alkylating agents, which is mostly used for the treatment of acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cyclophosphamide is converted into two bioactive metabolites, 4-hydoxycyclophasphamide and acrolein by hepatic microsomal cytochrome 450 enzyme, 4-hydoxycyclophasphamide that has chemotherapeutic effect whereas acrolein shows toxic effect (Ludeman, 1999; Kern and Kehrer, 2002; Arumugam et al., 1997). According to Alfarhan et al., 2020) the acrolein can directly stimulate mitochondrial oxidative stress via increasing the ROS level and therefore decline the defense mechanism of the cell by lowering the expression of catalase or glutathione. Other statements of this study include that ANT (adenine nucleotide translocase) is facilitated by the ATP/ADP exchange across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Several hypotheses suggest that the deficiency of ANT causes hyperpolarization in the mitochondrial membrane via reducing the migration of proton transporter to the mitochondrial matrix, which additionally regulates the transmission of electrons through the electron transport chain. The accessibility of electrons in mitochondria was found to be more, which increases the production of superoxide from oxygen. The deficiency of ANT inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain function, which further causes oxidative stress via promoting the production of ROS and reducing the expression of mitochondrial antioxidant defense mechanisms (Luo and Shi, 2005; Alfarhan et al., 2020). Some studies state that the increased malonaldehyde (MDA) level is an important indicator of lipid peroxidation, acrolein shows a toxic effect by increasing MDA level in the cerebral cortex and reducing the first line protector, most abundant antioxidant glutathione level (Rashedinia et al., 2015) GSH shows a protective effect against various oxidative stress in several diseases like lungs, brain cancer (Bains and Shaw, 1997; Subramaniam et al., 1997). Some studies suggest that the intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide decreases the level of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione transferase in the brain. Cyclophosphamide also increased the generation of H2O2 in both the cerebrum and cerebellum (Oyagbemi et al., 2016). The chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide increases oxidative stress, via the protein, carbohydrates oxidation, and lipid peroxidation include MDA and (4-HNE) 4-hydroxynonel (toxic product), which changes the normal function of the cell by altering the membrane fluidity and allow ca2+ ions to leak into the cell, it also increases the TNF-α, IL6 level, and the production of INOS, cox-2 (Fig. 2) (Paiva and Russell, 1999; Sies, 1985, 1986; Pryor and Godber, 1991; Oboh et al., 2011; Nafees et al., 2015).

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of cyclophosphamide to induce chemobrain. Chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide causes ROS production with increasing HNE protein, Malonaldehyde and decreasing antioxidant levels resulting in cognitive impairment.

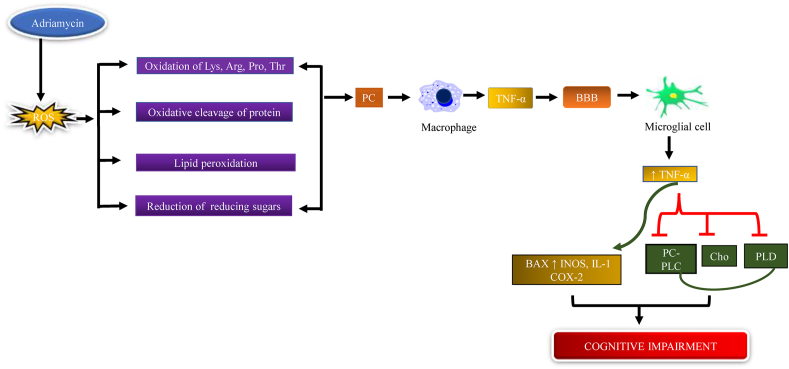

4.2. Adriamycin

Adriamycin (ADR) is a potent antibiotic chemotherapeutic agent that is mainly used in the treatment of different types of cancer including kidney, breast, thyroid, lungs, and Hodgkin's, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ren et al., 2019 state that TNF-α is a type of inflammatory cytokine which causes oxidative stress, leads to cognitive impairment and they have also suggested that the intraperitoneal injection of ADR increases plasma, brain protein carbonyl, and 4-HNE levels. Protein carbonyl is the most commonly used oxidative marker that increases oxidative stress (Weber et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2019). 4-hydroxytransnonel is one of the most important products of lipid peroxidation that is involved in oxidative stress and redox imbalance (Castro et al., 2017). The study showed that brain choline and creatine level were reduced after the administration of Adriamycin. Creatine is a naturally occurring compound whose main function is to supply energy to the muscle and brain (Andres et al., 2008; Persky and Brazeau, 2001). Ren et al., 2019 reported that with Adriamycin administration there is a decline in the expressions of reduction in the levels of Phospholipase-D (PLD) and phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC) in the brain (Li et al., 2013). Tangpong et al., 2006 show that in ADR-treated mice the TNF-α level increased in the cortex and hippocampus area, ADR disrupts the mitochondrial complex I substrate which led to reduced mitochondrial respiration, which is the main cause of oxidative stress. It is well known that ADR does not cross the BBB but ADR treatment increases the plasma TNF-α level by activation of glial cells that further increase the ROS production including H202, superoxide, and nitric oxide. The increased plasma TNF-α level crosses the BBB by endocytosis that further increases TNF-α level by the activation of the microglial cell. The circulating TNF-α is responsible for the mitochondrial dysfunction that causes tissue injury and neuronal damage (Tangpong et al., 2006; Joshi et al., 2010). Joshi et al., 2010 showed that the ADR treatment reduces the GSH level and causes oxidative stress that leads to protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation. GSH is an antioxidant that prevents the cell from cellular free radical NO, O2. and protects from lipid peroxidation. Neurons are susceptible to oxidative damage because of extremeO2 consumption and low GSH and other antioxidant levels (Fig. 3) (Joshi et al., 2010; Mark et al., 1997).

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of Adriamycin to induce chemobrain. Adriamycin increases ROS generation, oxidation of amino acids, protein, and lipid peroxidation leading to protein carbonyl formation, activation of the microglial cells which release TNF-α, cross BBB that decreases choline, PLC, and PC-PLD levels, and increased cytokine levels cause cognitive impairment.

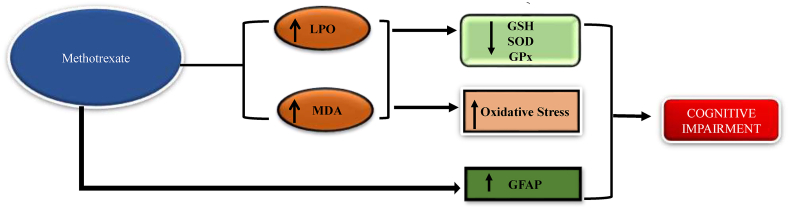

4.3. Methotrexate

Methotrexate is an anti-metabolite in the anthracycline class of drugs which is mainly used in the treatment of breast cancer, lung cancer, bladder cancer, leukemia, and osteosarcoma (Gottlieb et al., 2008). Tousson et al., 2016 states that after the administration of methotrexate the lipid peroxidation and malonaldehyde level increased and it has shown a reduced level of glutathione and catalase. It is also revealed that the expression of Glial fibrillar acid protein (GFAP) antibody in the hippocampus area (Tousson et al., 2016). Its expression of GFAP was increased, which is an indicator of activated astrocytes (Oliveira et al., 2016). Seigers et al., 2008 show that after the administration of methotrexate in the experimental animals there is an increase in the latency time in the Morris water maze test, which gives evidence of poor learning and memory performance (Seigers et al., 2008). Welbat et al., 2020 proved that the methotrexate treatment significantly decreases the SOD and GPX level in both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Fig. 4) (Welbat et al., 2020).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of methotrexate to induce chemobrain Chemotherapeutic agent methotrexate increases LPO (lipid peroxidation), Malonaldehyde and GFAP (Glial fibrillar acid protein) levels, causing cognitive impairment.

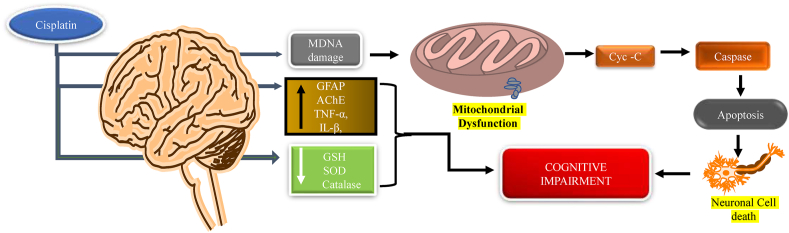

4.4. Cisplatin

The chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (cis-diammine dichlorido platinum (II)-CDDP) is a platinum compound class of drug that is mainly used in the treatment of cancers including ovarian, colon, bladder, head, neck, and testicles cancer. Cisplatin can cross the BBB and mainly affects the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory and learning (Screnci et al., 2000; Köppen et al., 2015; McWhinney et al., 2009; Stathopoulos, 2010). Lomeli et al., 2017 proved that cisplatin causes cognitive impairment by dysfunction of mitochondria. They have measured the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate by using the Seahorse XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer and proved that after the administration of cisplatin the oxygen consumption rate is reduced in hippocampus cell mitochondria (Lomeli et al., 2017). Jangra et al., 2016 performed the MWM to assess learning and memory and they have found the long latency time, which further estimates the antioxidant level and found that there is a reduction in the levels of SOD, catalase, glutathione. Further, they have shown the expressed level of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and also measured the expression level of Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and BDNF levels in the hippocampus (Fig. 5) (Jangra et al., 2016).

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of cisplatin to induce chemobrain. Chemotherapy agent cisplatin decreases antioxidant levels and disrupts mitochondrial DNA and releases cytochrome-C, which leads to caspase activation, causing apoptosis and resulting in neuronal damage that leads to cognitive impairment.

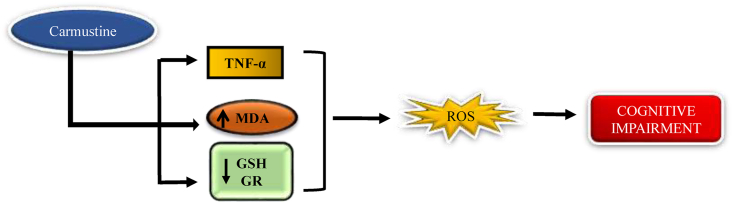

4.5. Carmustine

Carmustine is a nitrogen mustard β-chloronitrosourea alkylating agent used in the treatment of lymphoma both (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin), melanoma, primary brain tumors (Dietrich et al., 2006). Gouda K et al., states that the intraperitoneal injection of carmustine causes oxidative stress in the hippocampal brain area, BCNU expresses the TNF-α, MDA level, decreasing the GSH and GR (glutathione reductase) level (Helal et al., 2009). Narciso Couto et al., states that there is some chemotherapeutic agent like carmustine increase the hippocampal oxidative stress by inhibiting glutathione reductase enzyme and glutathione, glutathione is transported across the mitochondrial matrix via the dicarboxylate transporter (DIC) and 2-oxoglutarate transporter (OGC) that neutralize the oxidative stress, regulates some genetic function, glutathione level is maintained by glutathione reductase which is important for the recycling of oxidized glutathione into reduced glutathione (Yu and Zhou, 2007; Karplus and Schulz, 1987; Mittl and Schulz, 1994). Glutathione is an important antioxidant in which the reduced form of glutathione is capable of the defence mechanism against ROS (Fig. 6) (Zhang et al., 2012; Bass et al., 2004; Raturi and Mutus, 2007).

Fig. 6.

Mechanism of carmustine to induce chemobrain. Carmustine decreases the GSH level and increases the expression of TNF- α and Malonaldehyde, resulting in cognitive impairment.

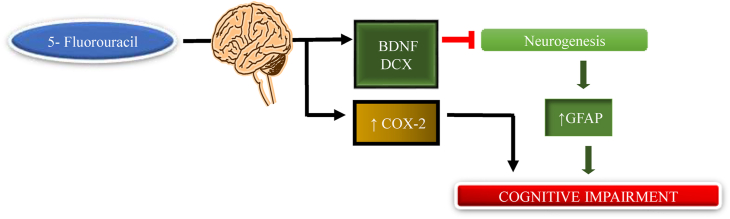

4.6. 5-Fluorouracil

Pyrimidine antagonist class 5-fluorouracil chemotherapeutic agent mainly used in breast, colon, oesophageal, stomach, pancreas, and prostate cancer (ELBeltagy et al., 2010). It is reported that the single high dose of 5-fluorouracil or combination causes chemobrain in animals, 5-fluorouracil readily crosses the BBB by a simple diffusion mechanism (Greenwald, 1976; Bourke et al., 1973; Kerr et al., 1984). Some study shows that after the administration of 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of breast cancer patient the chemobrain are reported(Falleti et al., 2005; Kuhl et al., 2004).Mainly, 5-fluorouracil affects the neurogenic area of the dentate gyrus is of the hippocampus. The subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus is responsible for adult neurogenesis in the brain. Neurogenesis is an important process for learning and memory (Dietrich et al., 2006; Mustafa et al., 2008; Han et al., 2008; Baudino et al., 2012; Kempermann, 2006; Kitabatake et al., 2007). Mustafa et al., 2006 show that after the administration of 5-fluorouracil the level of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) and DCX (doublecortin) in the hippocampus area of the brain has been decreased (Mustafa et al., 2008). Doublecortin is a phosphoprotein that has an important role in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral nervous system. It is essential for microtubule stabilization by migration and differentiation of neurons. Mutation in double cortin causes defective neuronal migration. The expression level of double cortin is mainly seen in the neurogenic zone such as the subgranular and subventricular zone (Gleeson et al., 1999; Rivest, 2006; Tint et al., 2009; Ocbina et al., 2006). The nerve growth factor BDNF belongs to the family of neurotrophins, which has a dominant role in the brain, which promotes the survival, growth, maturation, and axonal plasticity of neurons. It also plays an important role in the development of the nervous system (Alcántara et al., 1997). Some studies revealed that in the treated animals the increased cox-2 enzyme level causes the production of prostaglandins and causes inflammation in the periphery (Lopes et al., 2009). Sirichoat et al., 2020 show the hippocampus-dependent memory performance after the administration of 5-fluorouracil and show that the 5-fluorouracil animal shows less familiarization with a novel object during the familiarization phase, hence its evidence of poor learning and memory performance (Fig. 7) (Sirichoat et al., 2020).

Fig. 7.

Mechanism of 5-fluorouracil to induce chemobrain. 5-fluorouracil inhibits BDNF and DCX levels, leading to decreased neurogenesis resulting in cognitive impairment.

5. Chemotherapy alters brain functions and behavioural activities

5.1. BBB

Chemotherapy enters the BBB by simple diffusion. chemotherapy agent like cyclophosphamide, carmustine, carboplatin, and Taxotere damage the blood vessels at a high dose, that cause leakiness of BBB by altering its membrane permeability, such vascular damages activate microglial cells and thus enhance the synthesis of inflammatory biomarkers including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, PGE2 and cox-2 in CNS, and further disrupt the BBB, which leads to cause memory deficits (chemobrain) (Briones and Woods, 2014; Cossaart et al., 2003; Christie et al., 2012; Brown and Thore, 2011; Ohara et al., 1998; Breedveld et al., 2006; Jacobs et al., 2010).

5.2. Levels of neurotransmitter

Some studies reported that the concentration of some neurotransmitters includes serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine level decline in the hippocampus area of the brain after methotrexate administration (Yang et al., 2011). Ren et al., 2019 reported that Adriamycin declines the choline levels which is responsible for the synthesis of acetylcholine, which plays an important role in memory and attention (Ren et al., 2019).

5.3. Neuronal growth factor

5-FU is mainly involved in neurotrophic activity decline via the reduction of BDNF (it is responsible for the growth of neuronal cells mainly stem cells and is used in neuronal cell survival) in the hippocampus region of the brain. The decline in the expression of BDNF results in a reduction of neuronal cell growth or causes cell death. If the neuronal cells of the hippocampus are decreased, then memory processing and storage of which ultimately leads to cognitive impairment as well as neuroinflammation(Yang et al., 2011).

5.4. Effect of chemotherapy on myelin

Chemotherapy administration in the case of children affects the white matter (especially white fibers as compared to projection-type fiber). Chemotherapy affects the changes in the myelin region, if the neurons present in the corpus colosseum via direct toxic effect these alterations in the corpus callosum indirectly related to the inhibition of the myelination especially the inner myelin layer of the neurons are affected as the ages grows along with the administration of chemotherapy myelinate mechanism of the normal neurons becomes slower (Morioka et al., 2013; Deprez et al., 2011).

5.5. Folate

Methotrexate is transport into the cell by the reductase folate carrier. Methotrexate and 5-FU alter the folate homeostasis via a decline in expression of 5- methyltetrahydro folate and elevates the level of homocysteine in the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) and blood serum (Zhao et al., 2011; Vijayanathan et al., 2011).

6. Conclusion

Mitochondria is an important component of a cell which is a major site for ROS production(O2°, H2O2) which are toxic to proteins, lipids, and DNA that cause oxidative damage and reduce choline levels leading to a decline in cognition function. In this review, we have discussed the present evidence of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by cognitive impairment by the administration of chemotherapy. It is clear that the evidence of cognitive impairment some symptoms include difficulty in concentration, attention, processing speed, learning, and memory. The exact mechanism of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is unknown, but some preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate the link between CICI. Some chemotherapeutic agents like Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, and carmustine cause cognitive impairment. Chemotherapy agents mainly affect the hippocampus area of the brain. This shows a neurotoxic effect by reducing the capacity of neuronal repair (decrease BDNF level), reducing the level of the neurotransmitter (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine), and decreasing the choline concentration. The chemotherapeutic agent also reduced the antioxidant capacity associated with a reduction of glutathione, catalase, and superoxide dismutase. Chemotherapeutic agents increase the cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6) by the activation of microglial cells in the brain. It is also responsible for the reduction in the levels of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC), phospholipase D (PLD), and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzymes. ROS causes the elevation in the level of lipid peroxidation malonaldehyde, protein carbonyl, and 4-hydroxynonenal levels.

Funding sources

Not applicable.

Credit author statement

Kuleshwar Sahu-wrote the manuscript. Urvashi Langeh- Prepare diagrams and referencing. Charan Singh- Revise the manuscript. Arti Singh- Design the layout and critically revise the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express my gratitude to the Department of Pharmacology, ISF College of Pharmacy Moga, Punjab for providing us the facilities to complete the work.

References

- Ahles T.A., Saykin A.J. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2007;7(3):192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles T.A., Root J.C., Ryan E.L. Cancer-and cancer treatment–associated cognitive change: an update on the state of the science. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(30):3675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara S., Frisén J., del Río J.A., Soriano E., Barbacid M., Silos-Santiago I. TrkB signaling is required for postnatal survival of CNS neurons and protects hippocampal and motor neurons from axotomy-induced cell death. J. Neurosci. 1997;17(10):3623–3633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarhan M., Jafari E., Narayanan S.P. Acrolein: a potential mediator of oxidative damage in diabetic retinopathy. Biomolecules. 2020;10(11):1579. doi: 10.3390/biom10111579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres R.H., Ducray A.D., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Widmer H.R. Functions and effects of creatine in the central nervous system. Brain Res. Bull. 2008;76(4):329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam N., Sivakumar V., Thanislass J., Devaraj H. Effects of acrolein on rat liver antioxidant defense system. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1997;35(12):1373–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains J.S., Shaw C.A. Neurodegenerative disorders in humans: the role of glutathione in oxidative stress-mediated neuronal death. Brain Res. Rev. 1997;25(3):335–358. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban R.S., Nemoto S., Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120(4):483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass R., Ruddock L.W., Klappa P., Freedman R.B. A major fraction of endoplasmic reticulum-located glutathione is present as mixed disulfides with protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(7):5257–5262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudino B., D’agata F., Caroppo P., Castellano G., Cauda S., Manfredi M., et al. The chemotherapy long-term effect on cognitive functions and brain metabolism in lymphoma patients. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2012;56(6):559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besedovsky H.O., del Rey A. Immune-neuro-endocrine interactions: facts and hypotheses. Endocr. Rev. 1996;17(1):64–102. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-1-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigotte L., Olsson Y. Cytofluorescence localization of adriamycin in the nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1982;58(3):193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00690801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolisetty S., Jaimes E.A. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species: physiology and pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14(3):6306–6344. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke R.S., West C.R., Chheda G., Tower D.B. Kinetics of entry and distribution of 5-fluorouracil in cerebrospinal fluid and brain following intravenous injection in a primate. Canc. Res. 1973;33(7):1735–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010;45(7–8):466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M.D., Nicholls D.G. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem. J. 2011;435(2):297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedveld P., Beijnen J.H., Schellens J.H. Use of P-glycoprotein and BCRP inhibitors to improve oral bioavailability and CNS penetration of anticancer drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones T.L., Woods J. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment is associated with decreases in cell proliferation and histone modifications. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones T.L., Woods J. Dysregulation in myelination mediated by persistent neuroinflammation: possible mechanisms in chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment. Brain, behavior. Immunity. 2014;35:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W.R., Thore C.R. Cerebral microvascular pathology in ageing and neurodegeneration. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2011;37(1):56–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso S., Santos R.X., Carvalho C., Correia S., Pereira G.C., Pereira S.S., et al. Doxorubicin increases the susceptibility of brain mitochondria to Ca2+-induced permeability transition and oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45(10):1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J.P., Jung T., Grune T., Siems W. 4-Hydroxynonenal (HNE) modified proteins in metabolic diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;111:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.10.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celsi F., Pizzo P., Brini M., Leo S., Fotino C., Pinton P., et al. Mitochondria, calcium and cell death: a deadly triad in neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2009;1787(5):335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Jungsuwadee P., Vore M., Butterfield D.A., St Clair D.K. Collateral damage in cancer chemotherapy: oxidative stress in nontargeted tissues. Mol. Interv. 2007;7(3):147. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick B.R., Miller P.W. Elsevier; 2015. International Migration and the Economics of Language. Handbook of the Economics of International Migration; pp. 211–269. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Christie L.-A., Acharya M.M., Parihar V.K., Nguyen A., Martirosian V., Limoli C.L. Impaired cognitive function and hippocampal neurogenesis following cancer chemotherapy. Clin. Canc. Res. 2012;18(7):1954–1965. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C.S., Bennett G.J., Dantzer R., Dougherty P.M., Dunn A.J., Meyers C.A., et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer: Interdis. Int. J. Am. Canc. Soc. 2003;97(11):2919–2925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossaart N., SantaCruz K., Preston D., Johnson P., Skikne B. Fatal chemotherapy-induced encephalopathy following high-dose therapy for metastatic breast cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31(1):57–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull A., Hay C., Love S., Mackie M., Smets E., Stewart M. What do cancer patients mean when they complain of concentration and memory problems? Br. J. Canc. 1996;74(10):1674–1679. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J., Anderson L., Willmott N., Smyth J.F. The molecular pharmacology of doxorubicin in vivo. Eur. J. Canc. Clin. Oncol. 1991;27(5):532–535. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90209-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez S., Amant F., Yigit R., Porke K., Verhoeven J., JVd Stock, et al. Chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning in breast cancer patients. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011;32(3):480–493. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich J. 2010. Chemotherapy Associated Central Nervous System Damage. Chemo Fog: Springer; pp. 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich J., Han R., Yang Y., Mayer-Pröschel M., Noble M. CNS progenitor cells and oligodendrocytes are targets of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. 2006;5(7):1–23. doi: 10.1186/jbiol50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82(1):47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen M.R. Mitochondria in health and disease: perspectives on a new mitochondrial biology. Mol. Aspect. Med. 2004;25(4):365–451. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agamy S.E., Abdel-Aziz A.K., Wahdan S., Esmat A., Azab S.S. Astaxanthin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment (chemobrain) in experimental rat model: impact on oxidative, inflammatory, and apoptotic machineries. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55(7):5727–5740. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELBeltagy M., Mustafa S., Umka J., Lyons L., Salman A., Tu C.-Y.G., et al. Fluoxetine improves the memory deficits caused by the chemotherapy agent 5-fluorouracil. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;208(1):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falleti M.G., Sanfilippo A., Maruff P., Weih L., Phillips K.-A. The nature and severity of cognitive impairment associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Brain Cognit. 2005;59(1):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fato R., Bergamini C., Leoni S., Strocchi P., Lenaz G. Generation of reactive oxygen species by mitochondrial complex I: implications in neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33(12):2487–2501. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ruiz C., Morales A., Ballesta A., Rodes J., Kaplowitz N., Fernández-Checa J.C. Effect of chronic ethanol feeding on glutathione and functional integrity of mitochondria in periportal and perivenous rat hepatocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94(1):193–201. doi: 10.1172/JCI117306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun-Sherki Y., Melamed E., Offen D. Oxidative stress induced-neurodegenerative diseases: the need for antioxidants that penetrate the blood brain barrier. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40(8):959–975. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J.G., Lin P.T., Flanagan L.A., Walsh C.A. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23(2):257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb A., Korman N.J., Gordon K.B., Feldman S.R., Lebwohl M., Koo J.Y., et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58(5):851–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald E.S. Organic mental changes with fluorouracil therapy. Jama. 1976;235(3):248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith O.W., Meister A. Origin and turnover of mitochondrial glutathione. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82(14):4668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Yang Y.M., Dietrich J., Luebke A., Mayer-Pröschel M., Noble M. Systemic 5-fluorouracil treatment causes a syndrome of delayed myelin destruction in the central nervous system. J. Biol. 2008;7(4):1–22. doi: 10.1186/jbiol69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helal G.K., Aleisa A.M., Helal O.K., Al-Rejaie S.S., Al-Yahya A.A., Al-Majed A.A., et al. Metallothionein induction reduces caspase-3 activity and TNFα levels with preservation of cognitive function and intact hippocampal neurons in carmustine-treated rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Long. 2009;2(1):26–35. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.1.7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S., McCully C.L., Murphy R.F., Bacher J., Balis F.M., Fox E. Extracellular fluid concentrations of cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin in brain, muscle, and blood measured using microdialysis in nonhuman primates. Canc. Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010;65(5):817–824. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangra A., Kwatra M., Singh T., Pant R., Kushwah P., Ahmed S., et al. Edaravone alleviates cisplatin-induced neurobehavioral deficits via modulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016;791:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G., Sultana R., Tangpong J., Cole M.P., St Clair D.K., Vore M., et al. Free radical mediated oxidative stress and toxic side effects in brain induced by the anti cancer drug adriamycin: insight into chemobrain. Free Radic. Res. 2005;39(11):1147–1154. doi: 10.1080/10715760500143478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G., Aluise C.D., Cole M.P., Sultana R., Pierce W., Vore M., et al. Alterations in brain antioxidant enzymes and redox proteomic identification of oxidized brain proteins induced by the anti-cancer drug adriamycin: implications for oxidative stress-mediated chemobrain. Neuroscience. 2010;166(3):796–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaraman B., Joseph J., Kalivendi S., Wang S., Konorev E., Kotamraju S. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis: implications in cardiotoxicity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;234(1):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus P.A., Schulz G.E. Refined structure of glutathione reductase at 1.54 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195(3):701–729. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G. Oxford University Press; USA: 2006. Adult Neurogenesis: Stem Cells and Neuronal Development in the Adult Brain. [Google Scholar]

- Kern J.C., Kehrer J.P. Acrolein-induced cell death: a caspase-influenced decision between apoptosis and oncosis/necrosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2002;139(1):79–95. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr I.G., Zimm S., Collins J.M., O'Neill D., Poplack D.G. Effect of intravenous dose and schedule on cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of 5-fluorouracil in the monkey. Canc. Res. 1984;44(11):4929–4932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Dargusch R., Schubert D., Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects HT22 neuronal cells from oxidative stress. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2006;8(3–4):661–670. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabatake Y., Sailor K.A., Ming G-l Song H. Adult neurogenesis and hippocampal memory function: new cells, more plasticity, new memories? Neurosurg. Clin. 2007;18(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppelmans V., Breteler M., Boogerd W., Seynaeve C., Gundy C., Schagen S. Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(10):1080–1086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köppen C., Reifschneider O., Castanheira I., Sperling M., Karst U., Ciarimboli G. Quantitative imaging of platinum based on laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to investigate toxic side effects of cisplatin. Metallomics. 2015;7(12):1595–1603. doi: 10.1039/c5mt00226e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruidering M., Van De Water B., De Heer E., Mulder G.J., Nagelkerke J.F. Cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in porcine proximal tubular cells: mitochondrial dysfunction by inhibition of complexes I to IV of the respiratory chain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 1997;280(2):638–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl J., Doz F., Taylor R. 2004. Embryonic Tumors. Brain and Spinal Tumors of Childhood Arnold; pp. 314–330. London. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaz G. The mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species: mechanisms and implications in human pathology. IUBMB Life. 2001;52(3–5):159–164. doi: 10.1080/15216540152845957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li W., Jiang Z.-G., Ghanbari H.A. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14(12):24438–24475. doi: 10.3390/ijms141224438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M.T., Beal M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443(7113):787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Fiskum G., Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Neurochem. 2002;80(5):780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomeli N., Di K., Czerniawski J., Guzowski J.F., Bota D.A. Cisplatin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with impaired cognitive function in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;102:274–286. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes N.N.F., Plapler H., Chavantes M.C., Lalla R.V., Yoshimura E.M., Alves M.T.S. Cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in hamsters: evaluation of two low-intensity laser protocols. Support. Care Canc. 2009;17(11):1409–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0603-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Oveson B.C., Jo Y.J., Lauer T.W., Usui S., Komeima K., et al. Increased expression of glutathione peroxidase 4 strongly protects retina from oxidative damage. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2009;11(4):715–724. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludeman S.M. The chemistry of the metabolites of cyclophosphamide. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 1999;5:627–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Shi R. Acrolein induces oxidative stress in brain mitochondria. Neurochem. Int. 2005;46(3):243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal J.L., Hurtado O., Moro M.A., Lizasoain I., Lorenzo P., Castrillo A., et al. The increase in TNF-α levels is implicated in NF-κB activation and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in brain cortex after immobilization stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marí M., Morales A., Colell A., García-Ruiz C., Fernández-Checa J.C. Mitochondrial glutathione, a key survival antioxidant. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2009;11(11):2685–2700. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari M., Colell A., Morales A., von Montfort C., Garcia-Ruiz C., Fernández-Checa J.C. Redox control of liver function in health and disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010;12(11):1295–1331. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark R.J., Lovell M.A., Markesbery W.R., Uchida K., Mattson M.P. A role for 4-hydroxynonenal, an aldehydic product of lipid peroxidation, in disruption of ion homeostasis and neuronal death induced by amyloid β-peptide. J. Neurochem. 1997;68(1):255–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P., Magnus T. Ageing and neuronal vulnerability. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7(4):278–294. doi: 10.1038/nrn1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan H.R., Degli Esposti M. The contribution of mitochondrial respiratory complexes to the production of reactive oxygen species. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32(2):153–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1005507913372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhinney S.R., Goldberg R.M., McLeod H.L. Platinum neurotoxicity pharmacogenetics. Mol. Canc. Therapeut. 2009;8(1):10–16. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K.D., Siegel R.L., Lin C.C., Mariotto A.B., Kramer J.L., Rowland J.H., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66(4):271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittl P.R., Schulz G.E. Structure of glutathione reductase from Escherichia coli at 1.86 Å resolution: comparison with the enzyme from human erythrocytes. Protein Sci. 1994;3(5):799–809. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje M., Dietrich J. Cognitive side effects of cancer therapy demonstrate a functional role for adult neurogenesis. Behav. Brain Res. 2012;227(2):376–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka S., Morimoto M., Yamada K., Hasegawa T., Morita T., Moroto M., et al. Effects of chemotherapy on the brain in childhood: diffusion tensor imaging of subtle white matter damage. Neuroradiology. 2013;55(10):1251–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00234-013-1245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417(1):1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa S., Walker A., Bennett G., Wigmore P.M. 5-Fluorouracil chemotherapy affects spatial working memory and newborn neurons in the adult rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(2):323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafees S., Rashid S., Ali N., Hasan S.K., Sultana S. Rutin ameliorates cyclophosphamide induced oxidative stress and inflammation in Wistar rats: role of NFκB/MAPK pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015;231:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls D.G., Budd S.L. Mitochondria and neuronal survival. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80(1):315–360. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohl H., Hegner D. Evidence for the existence of catalase in the matrix space of rat-heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1978;89(1):126–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oboh G., Akomolafe T.L., Adefegha S.A., Adetuyi A.O. Inhibition of cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress in rat brain by polar and non-polar extracts of Annatto (Bixa orellana) seeds. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011;63(3):257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocbina P.J., Dizon M.L., Shin L., Szele F.G. Doublecortin is necessary for the migration of adult subventricular zone cells from neurospheres. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006;33(2):126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara S., Hayashi R., Hata S., Itoh N., Hanyu N., Yamamoto K. Leukoencephalopathy induced by chemotherapy with tegafur, a 5-fluorouracil derivative. Acta Neuropathol. 1998;96(5):527–531. doi: 10.1007/s004010050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira W.H., Nunes A.K., França M.E.R., Santos L.A., Lós D.B., Rocha S.W., et al. Effects of metformin on inflammation and short-term memory in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Brain Res. 2016;1644:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyagbemi A.A., Omobowale T.O., Saba A.B., Olowu E.R., Dada R.O., Akinrinde A.S. Gallic acid ameliorates cyclophosphamide-induced neurotoxicity in Wistar rats through free radical scavenging activity and improvement in antioxidant defense system. J. Diet. Suppl. 2016;13(4):402–419. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2015.1103827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva S.A., Russell R.M. β-carotene and other carotenoids as antioxidants. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999;18(5):426–433. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S.W., Dewhurst S., Bellizzi M.J., Gelbard H.A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in normal and diseased brain: conflicting effects via intraneuronal receptor crosstalk? J. Neurovirol. 2002;8(6):611–624. doi: 10.1080/13550280290101021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persky A.M., Brazeau G.A. Clinical pharmacology of the dietary supplement creatine monohydrate. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53(2):161–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichaud N., Messmer M., Correa C.C., Ballard J.W.O. Diet influences the intake target and mitochondrial functions of Drosophila melanogaster males. Mitochondrion. 2013;13(6):817–822. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk J., Meulenberg R., Hazeu W., Bos P., Kuenen J. Oxidation of reduced inorganic sulphur compounds by acidophilic thiobacilli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;75(2–3):293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor W.A., Godber S.S. Noninvasive measures of oxidative stress status in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991;10(3–4):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90073-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan C.L., Orr A.L., Perevoshchikova I.V., Treberg J.R., Ackrell B.A., Brand M.D. Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(32):27255–27264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi R., Turrens J.F., Chang L.Y., Bush K.M., Crapo J.D., Freeman B.A. Detection of catalase in rat heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266(32):22028–22034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph S.J., Moreno-Sánchez R., Neuzil J., Rodríguez-Enríquez S. Inhibitors of succinate: quinone reductase/Complex II regulate production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and protect normal cells from ischemic damage but induce specific cancer cell death. Pharmaceut. Res. 2011;28(11):2695–2730. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashedinia M., Lari P., Abnous K., Hosseinzadeh H. Protective effect of crocin on acrolein-induced tau phosphorylation in the rat brain. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2015;75(2):208–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raturi A., Mutus B. Characterization of redox state and reductase activity of protein disulfide isomerase under different redox environments using a sensitive fluorescent assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Keeney J.T., Miriyala S., Noel T., Powell D.K., Chaiswing L., et al. The triangle of death of neurons: oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and loss of choline-containing biomolecules in brains of mice treated with doxorubicin. Advanced insights into mechanisms of chemotherapy induced cognitive impairment (“chemobrain”) involving TNF-α. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;134:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivest S. Cannabinoids in microglia: a new trick for immune surveillance and neuroprotection. Neuron. 2006;49(1):4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13(9):566–578. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screnci D., McKeage M., Galettis P., Hambley T., Palmer B., Baguley B. Relationships between hydrophobicity, reactivity, accumulation and peripheral nerve toxicity of a series of platinum drugs. Br. J. Canc. 2000;82(4):966–972. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigers R., Schagen S.B., Beerling W., Boogerd W., Van Tellingen O., Van Dam F.S., et al. Long-lasting suppression of hippocampal cell proliferation and impaired cognitive performance by methotrexate in the rat. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;186(2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H. Hydroperoxides and thiol oxidants in the study of oxidative stress in intact cells and organs. Oxid. Stress. 1985;1:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sies H. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1986;25(12):1058–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Silberfarb P.M., Philibert D., Levine P.M. Psychosocial aspects of neoplastic disease: II. Affective and cognitive effects of chemotherapy in cancer patients. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1980 doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal P., Li T., Kumar D., Danelisen I., Iliskovic N. Adriamycin-induced heart failure: mechanisms and modulation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2000;207(1):77–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1007094214460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichoat A., Suwannakot K., Chaisawang P., Pannangrong W., Aranarochana A., Wigmore P., et al. Melatonin attenuates 5-fluorouracil-induced spatial memory and hippocampal neurogenesis impairment in adult rats. Life Sci. 2020;248:117468. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos G.P. Liposomal cisplatin: a new cisplatin formulation. Anti Canc. Drugs. 2010;21(8):732–736. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833d9adf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg E.M. Neural-immune interactions in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100(11):2641–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI119807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam R., Roediger F., Jordan B., Mattson M.P., Keller J.N., Waeg G., et al. The lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-trans-nonenal, alters the conformation of cortical synaptosomal membrane proteins. J. Neurochem. 1997;69(3):1161–1169. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szelenyi J. 2001. Cytokines and the central nervous system: brain research bulletin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangpong J., Cole M.P., Sultana R., Joshi G., Estus S., Vore M., et al. Adriamycin-induced, TNF-α-mediated central nervous system toxicity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;23(1):127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tint I., Jean D., Baas P.W., Black M.M. Doublecortin associates with microtubules preferentially in regions of the axon displaying actin-rich protrusive structures. J. Neurosci. 2009;29(35):10995–11010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3399-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousson E., Masoud A., Elatrsh A.M., Mostafa T. Oral supplementation of aqueous Ginkgo biloba extract inhibits oxidative stress and hippocampus injury associated with methotrexate injection. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2016;2(10):651–660. [Google Scholar]

- Troy L., McFarland K., Littman-Power S., Kelly B., Walpole E., Wyld D., et al. Cisplatin-based therapy: a neurological and neuropsychological review. Psycho-Oncology: journal of the Psychological. Social Behav. Dimen. Canc. 2000;9(1):29–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<29::aid-pon428>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstappen C.C., Heimans J.J., Hoekman K., Postma T.J. Neurotoxic complications of chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Drugs. 2003;63(15):1549–1563. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayanathan V., Gulinello M., Ali N., Cole P.D. Persistent cognitive deficits, induced by intrathecal methotrexate, are associated with elevated CSF concentrations of excitotoxic glutamate analogs and can be reversed by an NMDA antagonist. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;225(2):491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa R., Gupta R., Maurya P.K. Oxidative stress and accelerated aging in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorder. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2018;24(40):4711–4725. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190115121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnau J., Sharma V., Gamiz-Hernandez A.P., Di Luca A., Haapanen O., Vattulainen I., et al. Redox-coupled quinone dynamics in the respiratory complex I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2018;115(36):E8413–E8420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805468115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber D., Davies M.J., Grune T. Determination of protein carbonyls in plasma, cell extracts, tissue homogenates, isolated proteins: focus on sample preparation and derivatization conditions. Redox Biol. 2015;5:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefel J.S., Lenzi R., Theriault R.L., Davis R.N., Meyers C.A. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer: Interdis. Int. J. Am. Canc. Soc. 2004;100(11):2292–2299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbat J.U., Naewla S., Pannangrong W., Sirichoat A., Aranarochana A., Wigmore P. Neuroprotective effects of hesperidin against methotrexate-induced changes in neurogenesis and oxidative stress in the adult rat. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;178:114083. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigmore P. The effect of systemic chemotherapy on neurogenesis, plasticity and memory. Neurogen. Neural Plasticity. 2012:211–240. doi: 10.1007/7854_2012_235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Kim J.-S., Kim J., Kim S.-H., Kim J.-C., Kim J., et al. Neurotoxicity of methotrexate to hippocampal cells in vivo and in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;82(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankovskaya V., Horsefield R., Törnroth S., Luna-Chavez C., Miyoshi H., Léger C., et al. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science. 2003;299(5607):700–704. doi: 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Zhou C.Z. Crystal structure of glutathione reductase Glr1 from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2007;68(4):972–979. doi: 10.1002/prot.21354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Limphong P., Pieper J., Liu Q., Rodesch C.K., Christians E., et al. Glutathione-dependent reductive stress triggers mitochondrial oxidation and cytotoxicity. Faseb. J. 2012;26(4):1442–1451. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R., Diop-Bove N., Visentin M., Goldman I.D. Mechanisms of membrane transport of folates into cells and across epithelia. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011;31:177–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]