Abstract

Purpose: Gender-affirming care that integrates transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC)-related and/or transition-related health care needs is an effective mechanism to increase the number of TGNC patients being screened for HIV and linked to HIV services.

Methods: Evaluation of a gender-affirming education initiative to help clinicians in one clinic provides better care for TGNC patients.

Results: Processes and factors that support the effective implementation of a gender-affirming clinical environment include (1) establishing credibility within the local TGNC community; (2) the critical role played by a patient navigator; and (3) awareness of the lived experience of being TGNC. Participating in the education initiative boosted team motivation, improved knowledge and competence, and provided opportunities for training nonclinical staff.

Conclusion: This practice assessment interview offers a unique window into the impact of an education initiative on the effective implementation of a gender-affirming clinical environment.

Keywords: health disparities, health education/training, HIV/AIDS, outcomes, transgender

Introduction

Globally, transgender women are 49 times more likely to acquire HIV than the general population.1 In the United States, transgender women of color have a high prevalence rate for HIV infection (14%), second only to that for men who have sex with men.1–4 Whereas 0.3% of all American adults are living with HIV, the percentage of African American transgender women living with HIV ranges from 19% to 30%.3,5 Transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) persons are disenfranchised with the health care system and several factors pose barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among TGNC people, as well as to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and retention in HIV care. Social stigma, discrimination, health care provider biases, and health care that is insensitive to TGNC needs, identity, and cultural/lifestyle factors contribute to negative health care encounters for this population.6,7 Moreover, TGNC individuals who seek out health care encounters often do not return for further care if the entire experience is not sensitive to their gender identity.8 The US Department of Health and Human Services has acknowledged that the lack of culturally competent providers is a significant barrier to quality health care for TGNC persons,9 and ∼25% of TGNC individuals report that they have to teach healthcare providers (HCPs) about transgender health care.10

Gender-affirming strategies are required to address the needs of this patient population and improve their access to PrEP and HIV care.10,11 Gender affirmation is a key social determinant of health outcomes in TGNC people,12 and gender-affirming care that integrates TGNC-related and/or transition-related health care needs is an effective mechanism to increase the number of TGNC patients being screened for HIV and linked to HIV services.13,14 A gender-affirming environment uses patients' preferred names and pronouns, respects diversity in gender identities and expressions, and ensures that clinical and nonclinical staff are trained to provide a welcoming culturally appropriate environment for TGNC people that seek care.15

We developed a gender-affirming continuing medical education initiative accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to foster culturally competent, compassionate, and skilled care to help clinicians provide better care for TGNC patients. We report in this study on our evaluation of clinical practice engagement with the initiative.

Methods

Education program design, delivery, and evaluation

The education included a series of live, local, and regional meetings for primary care physicians and infectious disease specialists. The curriculum was promoted to HCPs as “elevate your practice to improve healthcare outcomes for TGNC persons” and the program was branded as “ELEVATE.” An on-demand, gender-affirming training webinar accompanied live meetings and targeted nonphysician HCPs (e.g., nurses, nurse practitioners [NPs], and physician assistants) and office personnel. We evaluated education impact on knowledge and competence through an Expanded Outcomes Framework that focused on learners' proficiencies and how motivation to change corresponded to practice changes16; we also planned to conduct practice assessment interviews through telephone after education and webinar participation.

An independent institutional review board (Western Institutional Review Board) approved the study. We recruited interview participants after education and webinar participation, and obtained verbal informed consent before interview. We developed an interview guide (Supplementary Data) that was designed to explore specific practice changes that resulted from the initiative, as well as key issues concerning how to create a gender-affirming environment.17 Despite considerable follow-up efforts to 13 practices that expressed interest in the interview, only one practice volunteered for a posteducation interview. All personnel involved with the Gender-Affirming program in this practice were present for the 60-min interview conducted by Annenberg Center for Health Sciences.

Data analysis

Initial review of the interview transcript suggested the potential to analyze the data as an intrinsic case study. In health policy and health care services research, intrinsic case studies are often used as an exemplar to understand policy pathways and protocol development and implementation.18 The group interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcript was imported into NVivo 12 (QSR International), a software package designed to support systematic analysis of unstructured textual data. We analyzed group discussion through constant comparative method, an iterative coding approach that allows for exploration of a priori issues and identification of emergent themes in the data.19 One of the authors A.H. coded transcript content using descriptive codes that followed the structure and focus of the interview guide, creating a coding frame that another author A. McC. validated. Additional coding identified themes across the data grounded in participants' reflections about both the education and its relation to their current clinical practice. Discussion among the authors provided analytic authentication of key themes.

Results

Interview participant roles and clinic setting

The clinic is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) that delivers primary and HIV-related care to TGNC persons, including HIV testing, PrEP, and ART. The clinic has a long history of serving TGNC people and is supported by on-site and linked nutritional, housing, and dental programs. The organization was founded in the 1980s by grass-roots volunteers active in HIV/AIDS health care. We interviewed nine members of the gender-affirming care team (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gender-Affirming Care Team Member Roles

| Chief operations officer |

| CHW |

| DCO |

| Licensed vocational nurse |

| Learning and development manager |

| NP |

| Navigator |

| Patient registration manager |

| Quality assurance administrator |

CHW, community health worker; DCO, director of clinical operations; NP, nurse practitioner.

We identified several themes: (1) establishing credibility within the local TGNC community; (2) the lived experience of being TGNC; (3) the critical role played by a patient navigator; (4) sex-positive HIV risk assessment; (5) and self-reported impact on HIV care of participating in the ELEVATE program.

Baseline practices before ELEVATE participation

Clinic history: the importance of establishing credibility in the local TGNC community

Before ELEVATE participation, the clinic had developed strong relationships with several community organizations. In 2018, the clinic's advisory group recommended implementing a more structured program to engage TGNC in primary care. The chief operating officer and NP described this process of operationalizing a structured gender-affirming program as organic and enthusiastic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Themes and Supporting Quotes

| Credibility in the TGNC community |

| What I love about it is nobody's being forced to do this on staff. This is coming from the heart. It's coming from individuals and it's really building a culturally-competent and medically-competent program. So, it's a very organic process. |

| At the structural level, I think stigma affects health outcomes, as cis-centered and heteronormative policies and practices limit the resources that are available to trans individuals. But looking at how we provide care, and the policies and practices that we have at [the clinic], we try to eliminate those cis-centered, heteronormative policies and try to make it more diverse, inclusive for everybody, regardless of their gender identity. |

| Trust and enculturation |

| I think more than having training, education and concrete solutions about gender-affirming care, I think it's living it, practicing it on a daily basis, and enculturating those practices in our daily activities here at the clinic—in the clinic and outside the clinic. |

| We try to make sure that they have the proper training as well to ensure that they're knowledgeable of this terminology and pronouns and that kind of stuff. |

| Critical role of transgender navigator |

| And we don't just like tell them, “Oh, now you go over there.” We make sure that all of our staff, whether they need to meet with myself or, or I'm taking them to the Health Center to schedule with either or, we make sure we always do warm hand-offs. So, we're always with our clients. We're just trying to create warmth and that saves face and they're not alone. [CHW] |

| So that, I think makes a big difference for them. It's coming in, registering, making them feel comfortable right away, you know, being included in everything, and [navigator] coming to meet with them. I think that's made a huge difference for our patients. One of our key staff in the central registration department is trans, so that's a very welcoming and comforting first encounter with, and then being introduced to [navigator] who helps walk them through everything within the organization to get them connected where they need to be. |

| Sex-positive HIV risk assessment |

| As far as like HIV risk assessment, it would be [asking about] sexual practices. What are the things that they're doing to decrease their risk for HIV? Are they on PrEP? Have they ever been on PEP? If they are living with HIV, what medications are they on? Are they taking the medications on a regular basis? What are the barriers they are experiencing if they don't have really good compliance? So those are some of the things that we have in regards to discussion of HIV care. One of the things, the way that I approach my care for my patients is I always tell my patients that, you know, every part, every aspect of your health is very important and that equals sexual health. So looking at it in a positive manner and having a sex-positive way of asking the questions I think has been very helpful. |

| Impact of ELEVATE |

| When we did our Transgender 101, a lot of the surveys that we saw were our staff really wanted more continuous, reoccurring training because they were confused, or it was just brand new to them. So participating in ELEVATE, we were able to extend some more of that education, as well as I'm currently working on extending that to retail stores that are attached to [the clinic]. And I am working on doing kind of a Transgender 101 specific to them for, you know, like dressing room procedures and stuff like that. So… |

| I heard a lot of people didn't quite understand something before going in, and now have a much, much better understanding. I personally have been to many trans-related trainings over the years, and I found that this was the best training I've been to, and I learned something new. S-O-G-I, and now I know it's S-O-G-I-E with “expression.” And I heard from people in our retail stores that they hadn't quite understood exactly the issue of pronouns. And the Director of that said, “I get it now. I understand the importance of appropriate pronouns,” whereas they hadn't quite grasped that before. |

COO, chief operating officer; LDM, learning development manager; SOGI, sexual orientation/gender identity; TGNC, transgender and gender nonconforming.

Team members described this program as informed by an ecological and intersectional model of care that considers how structural, personal, and interpersonal factors affect health care access and delivery and felt that this theoretically informed approach to developing the program had been effective. Within 1 year, the number of self-identified TGNC patients in the program (n=15) increased 427%.

Trust, enculturation, and TGNC lived experience

Team members identified trust as key to effective relationships between clients and HCPs. For instance, many self-identified transgender clients of the clinic are concerned that HIV medication might affect the efficacy of estrogen therapy. Therefore, a key program goal is to ensure that HCPs are equipped to provide information to clients about medication to reduce their concern and in doing so support their engagement in care and adherence to medication. As noted by the NP (Table 2), an acute sense of the importance of trust also stems from a deliberate process of threading transgender practices and concerns throughout the culture of the organization (enculturation), which in turn is informed by lived transgender experience among key staff. Enculturation was also shored up by integrating formal training throughout the organization. For instance, many clinicians are certified by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and have received training from the Association of Providers of AIDS Care and other HIV-related organizations. The Learning and Development Manager (Table 2) has also developed a Transgender 101 training for new hire orientation and onboarding as well as for in-house vendors (e.g., an on-site pharmacy provider, testing vendor, and yoga studio).

Intake process: the critical role of the transgender navigator

The team developed a succinct intake process. Intake forms use gender-inclusive and bilingual language as Spanish is dominant in the area the clinic serves. The nursing department makes concierge calls to prepare clients before clinic attendance and collect information on sexual orientation and gender identity. On arrival at the clinic, the navigator meets clients at the central registration department, which employs TGNC staff, and identifies appropriate resources and support. The clinic uses “warm-handoffs” in which clients are always present with a clinic staff member (Table 2). Team members affirmed this approach and felt that clients appreciated warm handoffs. The director of clinical operations considered this immediate connection with both the navigator and TGNC personnel as vital (Table 2).

Sex-positive HIV risk assessment

The clinic's HIV risk assessment includes questions about sexual practices; whether clients are using PrEP, have ever been on postexposure prophylaxis, or are living with HIV; current medications; and barriers to medication adherence. The lead NP, who is also a certified HIV Testing Counselor, emphasized the importance of including sexual health as a broader aspect of health and asking questions in a sex-positive way. Clients who are status unaware and want to be tested are offered an HIV test. The program has also invested several wraparound services. For instance, a Reentry Work Specialist (a transgender woman) was recently hired to connect clients to job opportunities, create resumes, and prepare for potential interviews. The clinic navigator is also creating a social volunteer group led by a TGNC specialist or navigator to address isolation and stigma.

The impact of ELEVATE participation

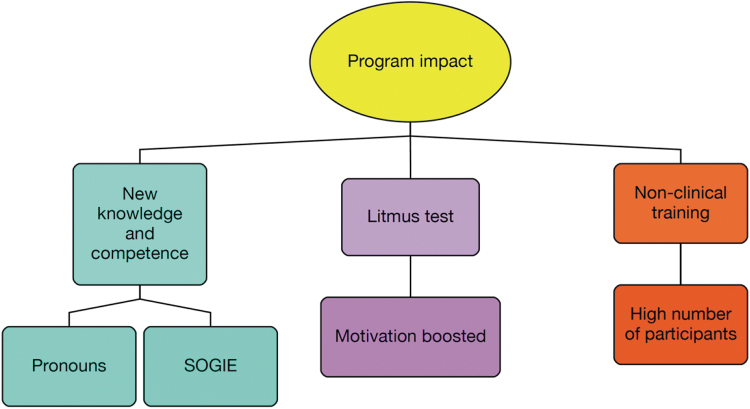

The group's reported impact of ELEVATE was threefold: (1) boosting team motivation; (2) improving knowledge and competence; and (3) providing opportunities for nonclinical staff training (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Model of program impact.

Although the team has a long history of working with TGNC clients, members were motivated to participate in ELEVATE because they viewed the initiative as a “litmus test” to identify whether “we are doing the things that we should be doing” and to solicit external feedback about program improvement. ELEVATE participation was effective in this regard. After completion of the program, the team felt validated in the approach they are taking to create a gender-affirming clinic environment and motivated to continue this path. ELEVATE participation also expanded program capacity to provide nonclinical training on TGNC needs. Although the clinic currently offers Transgender 101 training, staff identified a need to provide a full spectrum of patient-centered education around lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning and other communities (LGBTQ+) people for nonclinical support staff. ELEVATE participation helped the clinic involve more staff in TGNC training (∼70 clinic staff participated in the ELEVATE webinar), consolidate such training as a benefit to organizational culture, and improve nonclinical staff knowledge (Table 2).

Discussion

We analyzed group discussion data as a case study in implementing and fostering a gender-affirming clinical environment. The clinic's approach to creating a gender-affirming clinic environment was guided by clear acknowledgment that social and structural determinants of health drive HIV infections in TGNC communities, who experience these determinants as challenges and barriers to care.20 Team members described the program model as “an ecological and intersectional model of care” that incorporates components of WPATH guidelines such as navigation, trans-competency training, collaborating with community organizations and partners, and hiring staff members who reflect the TGNC community. Each team member shared perspectives that were germane to their roles within the clinic and spoke with a coherent voice about the goals, successes, and challenges associated with their program. This coherent voice appeared to reflect a well-defined culture framed by a commitment to the lived experience of TGNC people and to a process of continuous improvement. For instance, the interview concluded with a preview from team members of ongoing initiatives, including the creation of a wellness office, creating a mentorship volunteer group, community engagement through panel discussions with people in the local TGNC community, and further education and training for clinicians. Although the low volume of collected data limits the generalizability of these insights our approach offers in-depth insights into the “how,” “what,” and “why” of clinic processes and can be used to understand pathways of gender-affirming protocol development and implementation.20

Conclusion

Although there are several published guidance documents on how to implement TGNC programs, beyond demonstration project reports, there is very little published literature on the implementation of practices and policies to support a gender-affirming clinical environment.21–23 This practice assessment interview offers a unique window into education initiative impact and presents an overview of the process and factors that support the effective implementation of a gender-affirming clinical environment. Although team members emphasized their long history of effectively implementing strategies tailored to the specific needs, culture, and lifestyle of TGNC people, group discussion affirmed that participation in the education initiative and, in particular, ELEVATE certification, provided a degree of external validation for the program.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- HCP

healthcare provider

- NP

nurse practitioner

- PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

- TGNC

transgender and gender nonconforming

- WPATH

World Professional Association for Transgender Health

Authors' Contributions

A.H. designed the interview guide, conducted clinic interviews, analyzed case study, and wrote the article. B.M. designed the education program. A.M. designed the interview guide, the education program, and co-wrote the article. All authors reviewed and approved of the article before submission.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The education program, data collection, and analysis were funded by an unrestricted education grant from ViiV Healthcare and Janssen Therapeutics. The funders played no role in education design, data collection, analysis, or article drafting.

Supplementary Material

Cite this article as: Howson A, Mutschler B, McCrea A (2021) Designing and evaluating a gender-affirming educational initiative for optimal HIV care: an intrinsic case study, Transgender Health 6:5, 296–301, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0124.

References

- 1. Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, et al. . Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among transgender people. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 3. Clark H, Babu AS, Wiewel EW, et al. . Diagnosed HIV infection in transgender adults and adolescents: results from the National HIV Surveillance System, 2009–2014. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:2774–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, et al. . Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2018;109:e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. James SE, Herman J, Rankin S, et al. . The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poteat T, Reisner SL, Radix A. HIV epidemics among transgender women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care. 2013;51:819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients—practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:843–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Recommended actions to improve the health and well-being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Communities. https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbt/enhanced-resources/reports/health-objectives-2011/index.html Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 10. National Prevention Information Network. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/national-hivaids-strategy-united-states-updated-2020, 2019 Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 11. The Office of National AIDS Policy. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Updated to 2020. https://www.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/nhas-update.pdf, 2017 Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 12. Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72:S235–S242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rochon TJ. Improving Primary Care Utilization for Transgender Patients at an FQHC. Health Sciences Research Commons. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=son_dnp. 2018.

- 15. Sevelius JM, Deutsch MB, Grant R. The future of PrEP among transgender women: the critical role of gender affirmation in research and clinical practices. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(7(Suppl 6)):21105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moore DE Jr, Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stake R. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, et al. . The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research. London: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection, 2017. Part A: Census tract-level social determinants of health and diagnosed HIV infection—United States and Puerto Rico. Part B: County-level social determinants of health, selected care outcomes, and diagnosed HIV infection—41 states and the District of Columbia. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24(No. 4): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization. Policy Brief: Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations, 2016 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization. Tool to Set and Monitor Targets for HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations Supplement to the 2014 Consolidated Guidelines for HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolf RC, Adams D, Dayton R, et al. . Putting the t in tools: a roadmap for implementation of new global and regional transgender guidance. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(3 Suppl 2):20801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.