Abstract

Purpose: While lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) elders face a multitude of barriers to healthy aging, little is known about needs and concerns specific to transgender elders, except that they face many self-perceived challenges to healthy aging, which exist at the individual, community, and institutional levels. To further understand these needs, we explored the perspectives of transgender individuals aged 65 and older on health care, expectations of aging, concerns for the future, and advice for young transgender people.

Methods: We performed 19 semistructured interviews with individuals who identify as transgender elders, 10 transgender women and 9 transgender men. Interviews were transcribed and coded by three investigators to generate salient themes via thematic analysis.

Results: We identified 7 major themes that exemplify the concerns and experiences of this sample of the aging transgender community: fear of mistreatment in elder care, isolation and loneliness exacerbated by transgender identity, increased vulnerability to financial stressors, perceived lack of agency, health care system and provider inclusivity, giving back to one's community, and embracing self-truth as a path to fulfillment.

Conclusion: While some of these concerns, such as fear of mistreatment, are common among elders, the concerns of transgender elders are heightened due to stigma compounded by being both transgender and elderly. Health care providers, nursing home staff, and social workers must be sensitized to these needs and fears to provide appropriate, affirming, and respectful care and support to transgender elders.

Keywords: health care inclusivity, healthy aging, transgender elders, transgender health

Introduction

With aging comes many challenges, including social isolation and possible decline in physical and mental well-being.1 However, not all people face the same challenges as they age. Minority stress theory argues that unique challenges exist for those in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) community, given increased rates of violence, discrimination, internalized homophobia, and rejection due to gender identity or expression.2 Unfortunately, such experiences are particularly frequent among the transgender community, further increasing the relevance of minority stress theory.3 For those who are both transgender and elderly, holding multiple marginalized identities likely leads to “overlapping areas of stigma.”4 The aging transgender population is disproportionately impacted by social determinants of health that exist at the individual, community, and institutional levels.5–8 Social determinants of health, including education, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic factors, are fundamental causes of inequity in health, particularly among older adults.9–12 Thus far, efforts to understand them have focused primarily on LGBTQ people as a whole, without emphasis on any of the subsets within this diverse population.13–18 The specific and general needs of the elderly transgender population must be assessed to adequately address these needs.

Putney et al. conducted a qualitative inquiry into the concerns and anticipated needs of LGBTQ adults in later life. They identified “the affordability of long-term care, uncertainty about who will care for them, fear of dementia, fear of mistreatment, end of life, and the need for LGBTQ-inclusive long-term care settings” as predominant concerns among this group.13 This study also noted the reliance of many older LGBTQ adults on informal support networks for care and the decline in mental health that loneliness and isolation may cause in this population.13 Moreover, Witten, in reporting the results from The Transgender MetLife Survey, documented that 30% of respondents (n=1963) were unsure of who would care for them in the event of illness.19 Serafin et al. reported that transgender patients may hide important details of their health history from their health care providers given their fear of being judged or mistreated by uninformed health care personnel.15

The Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study was the first federally funded longitudinal national project designed to better understand the aging, health, and well-being of LGBTQ midlife and older adults and their families.20 It included 2400 LGBTQ adults ranging in age from 50 to over 100. However, among over 75 articles produced using data from this study, only three focused on transgender individuals.21–23 Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. found that among LGBTQ elders, transgender individuals demonstrated significantly higher risk of poor physical health, perceived stress, disability, and depressive symptomatology than LGB peers. They point to internalized stigma, fear of utilizing medical services, insufficient social support, and physical inactivity as potential mediators of these effects.21 Hoy-Ellis and Fredriksen-Goldsen found that in a cohort of 174 transgender individuals, nearly half experienced depressive symptomatology, which they attributed to minority specific stressors (e.g., identity disclosure and transphobia) and perceived general stressors associated with aging.22 Of the studies related to transgender elders, most utilize survey data.5,19,21–25 Two in-depth qualitative studies again focus on LGBTQ people but did not specifically address transgender health.26,27

The purpose of this study was to identify the unique needs of the transgender elder community via semistructured interviews and qualitative analysis.

Methods

Recruitment and participant demographics

To investigate the experience of aging among transgender elders, we used a qualitative approach consisting of individual interviews. Using a community-based participatory research approach, we consulted with the Community Research Advisory Team (CREATE), a transgender community advisory group in Upstate New York affiliated with the Gender Wellness Center (GWC), a gender-inclusive family medicine practice from which some participants were recruited.28 Guided by goals outlined by CREATE, investigators drafted an interview guide that was modified and approved by CREATE.

Starting with a convenience sample, a snowball sampling method was used to recruit study participants. Transgender GWC patients aged 65 and older were invited to participate in the interviews. Participants recommended and provided contact information for other elders, which led to additional recruitment. Both recruitment at the GWC and snowball sampling occurred concurrently, resulting in 19 study participants. Before interviews, participants completed a written consent form and demographic questionnaire. Participants received a $25 grocery store or Amazon gift card upon completing the interview.

The study was approved by our hospital Institutional Review Board.

Interviews and qualitative analysis

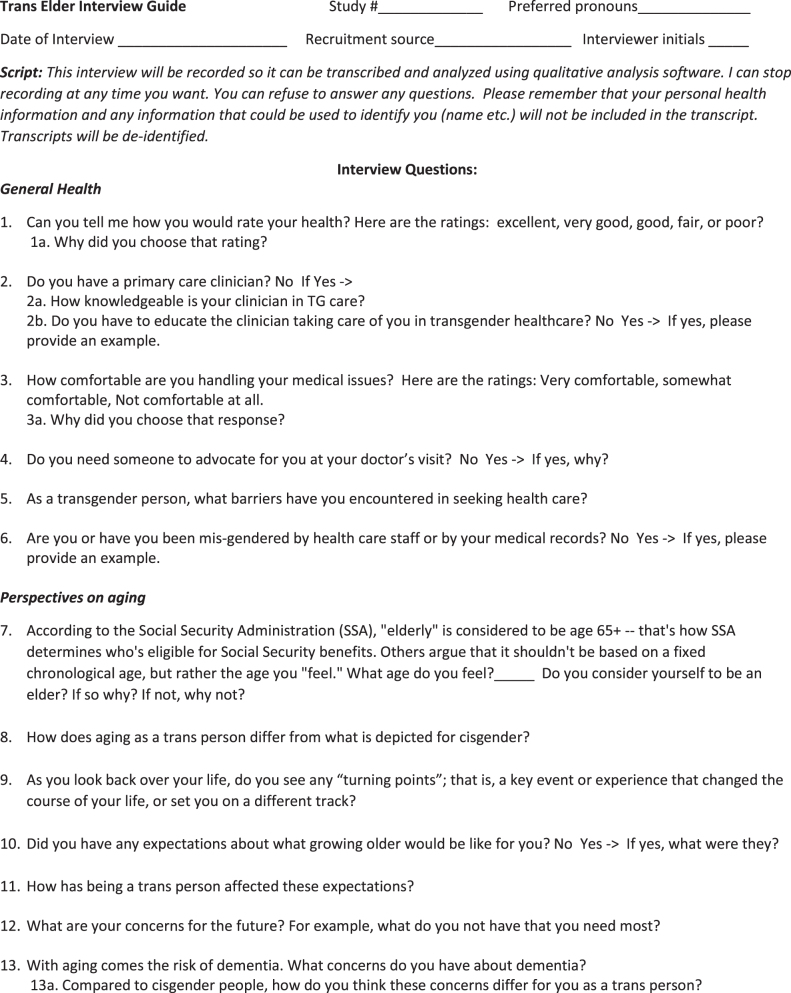

Semistructured interviews were conducted in English via Zoom and recorded using voice recording software. The interview guide used can be found in Figure 1. Interviews ranged from 30 to 90 min, with an average duration of 37 min. The interviews were transcribed by a third party and de-identified.

FIG. 1.

Interview guide for semi-structured interviews with transgender elders.

Analysis of interview transcripts was conducted using an inductive thematic analysis approach, divided among three of the authors (M.A., M.S., N.T.).29 Each coder read their allotted transcripts and drafted a descriptive summary of the content, followed by a line by line analysis to produce open codes. Open codes were subsequently compiled into one document and coders jointly assigned parent codes to group conceptually related open codes together. Assignment of parent codes was discussed until all coders reached consensus. This process continued until no new parent codes were developed.

Parent codes were compiled in a codebook. Coders used it to assign the remaining open codes allotted to them and met regularly to resolve assignment uncertainties. Coders then grouped parent codes by overarching concepts, resulting in identification and selection of salient themes.29 After analysis of the 19 interviews, all coders agreed that thematic saturation was achieved.

Results

Participant characteristics

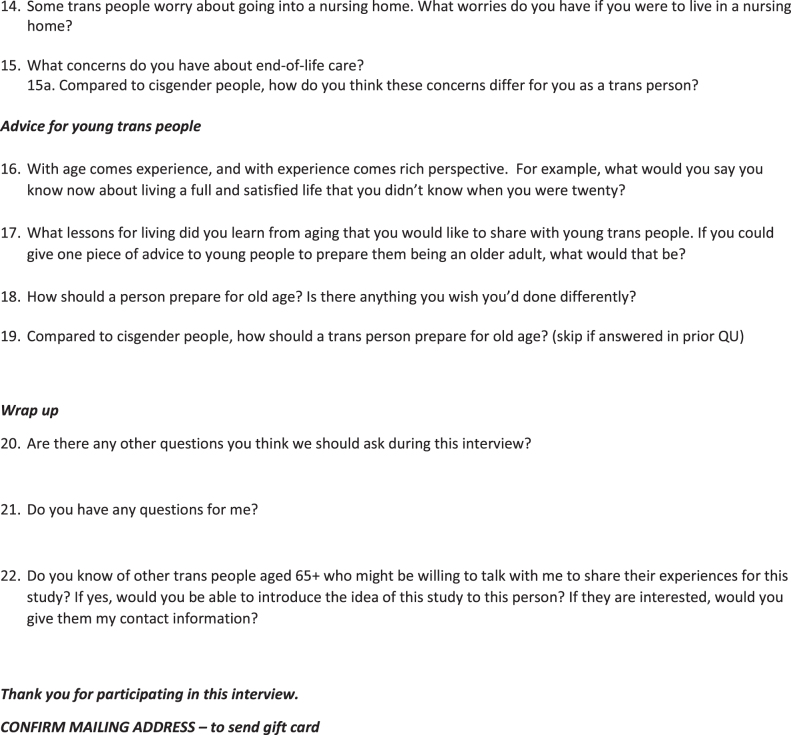

A total of 19 interviews with 9 transgender men and 10 transgender women were conducted over the course of 5 months. Ages ranged from 64 to 82 (youngest was 1 month away from turning 65). All identified as white and lived independently in equally distributed rural, suburban, and urban settings. Just over 50% of participants had partners and children. Ninety percent of participants were insured by Medicare, none had Medicaid, and 84% had supplemental insurance. Furthermore, 32% of participants reported having a doctorate or professional degree and 63% felt that they were living “fairly comfortably” financially. See Table 1 for complete participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (n=19)

| Transgender women (n=10) |

Transgender men (n=9) |

Overall (n=19) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age | |||

| 64–69 | 4 (40.0) | 5 (55.6) | 9 (47.4) |

| 70–74 | 2 (20.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (26.3) |

| 75–79 | 3 (30.0) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (21.1) |

| 80–84 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (5.3) |

| Self-identified race/ethnicitya | |||

| White | 10 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) |

| Self-rated health | |||

| Excellent | 3 (30.0) | 0 | 3 (15.8) |

| Very good | 3 (30.0) | 4 (44.4) | 7 (36.8) |

| Good | 3 (30.0) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (31.6) |

| Fair | 1 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| Community size | |||

| Rural | 4 (40.0) | 2 (22.2) | 6 (31.6) |

| Suburban | 4 (40.0) | 3 (33.3) | 7 (36.8) |

| Urban | 2 (20.0) | 4 (44.4) | 6 (31.6) |

| Partner status | |||

| Single | 6 (60.0) | 3 (33.3) | 9 (47.4) |

| Partnered | 4 (40.0) | 6 (66.7) | 10 (52.6) |

| Length of partnership (years)b | |||

| 0–19 | 1 (25.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) |

| 20–39 | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (10.0) |

| 40 or greater | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 2 (20.0) |

| Partner involved in careb | |||

| Yes | 1 (25.0) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (60.0) |

| No | 3 (75.0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (40.0) |

| Gender attracted to | |||

| Male | 2 (20.0) | 0 | 2 (10.5) |

| Female | 4 (40.0) | 5 (55.6) | 9 (47.4) |

| Neither | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (5.3) |

| Both | 3 (30.0) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (31.6) |

| All | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (5.3) |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 3 (30.0) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (47.4) |

| 1 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| 2 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| 3 or more | 5 (50.0) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (31.5) |

| Children involved in carec | |||

| Yes | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (10.0) |

| No | 6 (85.7) | 3 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) |

| Religious/spiritual affiliation | |||

| Yes | 8 (80.0) | 5 (55.6) | 13 (68.4) |

| No | 2 (20.0) | 4 (44.4) | 6 (31.6) |

| Insurance covers needs | |||

| Yes | 9 (80.0) | 6 (66.7) | 14 (73.7) |

| No | 1 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| Partially | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| Insurance covers prescriptions | |||

| Yes | 9 (90.0) | 4 (44.4) | 13 (68.4) |

| No | 1 (10.0) | 5 (55.6) | 6 (31.6) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Some high school, no diploma | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (5.3) |

| Some college, no degree | 2 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (15.8) |

| Associate's degree | 2 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (15.8) |

| Bachelor's degree | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| Master's degree | 2 (20.0) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (21.1) |

| Doctorate/professional degree | 3 (30.0) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (31.6) |

| Financial security | |||

| Having financial trouble | 1 (10.0) | 2 (22.22) | 3 (15.8) |

| Living fairly comfortably | 5 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | 12 (63.2) |

| Living very comfortably | 4 (40.0) | 0 | 4 (21.1) |

None identified as Latinx or African American.

For those participants who have partners.

For those participants with children.

When asked to rate their overall health, 53% of participants rated their health as either “excellent” or “very good,” 32% rated their health as “good,” and 16% rated their health as “fair.” When asked how comfortable they feel handling their own medical issues, 47% of participants responded “very comfortable” and 53% reported feeling “somewhat comfortable.”

All participants reported that they have a primary care provider; however, attitudes varied toward perception of their provider's knowledge of transgender care. Fifty-three percent of participants felt that their provider was knowledgeable in transgender care and 21% felt that their provider was not. Twenty-six percent of participants felt that their provider had only some knowledge of transgender care, making statements such as “She is a lot more knowledgeable since having me as a patient.”

Qualitative results

We identified seven themes that exemplify the concerns and experiences of this sample of the aging transgender community: (1) fear of mistreatment in elder care; (2) isolation and loneliness exacerbated by transgender identity; (3) increased vulnerability to financial stressors; (4) perceived lack of agency; (5) health care system and provider inclusivity; (6) giving back to one's community; and (7) embracing self-truth as a path to fulfillment. A summary of these themes, with supporting quotes, can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key Themes with Definition and Supporting Quote

| Key theme | Definition | Supporting quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Fear of mistreatment in elder care | Fear of nonaffirming care in elder care facilities, ranging from use of incorrect pronouns to acts of physical or sexual violence | “I worry about whether or not the people who are assisting me are going to be judgmental, are they going to be mean or be professional and take care of me like any other patient…Will I be abused in the nursing home because I am a trans person?” (Participant M, age 64, transgender man) |

| (2) Isolation and loneliness exacerbated by transgender identity | Lack of social connection heightened by transgender identity, including estrangement from spouses, partners or family members, concerns over accessing social resources | “[loneliness] can be more prevalent for trans people, because so many have had their families or partners abandon them and never rally back. They may have difficulty finding a partner who is comfortable with having a trans partner.” (Participant O, age 79, transgender man) |

| (3) Vulnerability to financial stressors | Increased risk of financial insecurity due to transphobia, such as loss of employment or professional opportunities due to transgender identity | “Getting fired from jobs because I was transgender were not happy or expected things.” (Participant C, age 70, transgender man) |

| (4) Perceived lack of agency | A perceived lack of control over how one will be treated at end of life or in nursing homes, potentially complicated by dementia, also includes lack of agency over one's narrative as transgender, such as fear of incorrect pronoun use in an obituary | “I worry about how my family is going to bury me and how they are going to show me in my casket. When I die and I am buried, I would like to be as the female I have become now.” (Participant Q, age 67, transgender woman) |

| “It's the loss of independence and loss of control. The worse case scenario would be I would lose all control over my life, how I would dress and everything else.” (Participant I, age 76, transgender woman) | ||

| (5) Health care system and provider inclusivity | The extent to which health care systems and providers are sensitive toward transgender individuals, including verbal communication and body language; medical records that accommodate gender identity | “I have literally been escorted out of an Ob-Gyn office. I was almost dragged out and was told we don't see your kind here…The younger men and women now don't have to go through that.” (Participant R, age 72, transgender man) |

| (6) Giving back to one's community | A desire to engage with and give back to one's community, through one's profession, activism, financial donation, education, youth mentorship or other means | “Over the years, I have put about $200,000.00 or more into the trans movement. That was money spent to support the early organizations.” (Participant D, age 78, transgender woman). |

| “I work in psychiatry and there are so few practitioners. Some of the clients we serve are homeless people and 95% of them are drug and alcohol addicted. As long as I can work, I want to serve these people and it's like another life mission.” (Participant O, age 79, transgender man) | ||

| (7) Embracing self-truth as a path to fulfillment | Self-acceptance of transgender identity as a source of happiness, inner peace and wisdom and a catalyst for improved mental health | “I didn't know much at twenty…Over a period of time I became more comfortable with me, and especially after transitioning…The sooner that you're comfortable with who you are, you don't worry so much about what other people think.” (Participant A, age 82, transgender woman) |

Fear of mistreatment in elder care

Participants were nearly unanimous in voicing fears over the prospect of receiving elder care, regardless of the form of care (e.g., in-home services or institutionalized settings such as nursing homes or assisted living facilities). The consensus from participants was that such care would be fraught with mistreatment and lack of affirmation of gender identity. The concerns voiced about mistreatment ranged from microaggressions, such as being addressed by the wrong pronouns, to severe macroaggressions, such as acts of physical and sexual abuse.

Participants expressed trepidation over lack of control over their care and situation in an elder care setting, as stated by a participant:

“I have concerns about losing my independence. I have concerns about how I would be treated if I was in an elder facility. I have no control over that.” (Participant I, age 76, transgender woman)

There was fear over the lack of social and systemic support for gender minorities; participants were concerned that they would not be able to advocate for themselves and there would be no one to advocate for them. As expressed by one:

“Nobody wants to end up in a nursing home because they don't know what will happen to them. We don't know what they would do to us in a nursing home with no one there to guard us.” (Participant R, age 72, transgender man)

Acquaintances with other elderly transgender people who were mistreated in elder care situations further magnified fears, as shared by one participant:

“One of my fears is that I would end up in a nursing home with no one to advocate for me. I run an online group for transgender men…Some have been in nursing homes for rehab purposes. None of them have had a good experience.” (Participant H, age 69, transgender man)

Fears of being discriminated against due to gender identity and gender expression were shared, manifesting in care inequities compared to cisgender patients. Much fear was expressed about staff who are not trained in the care of transgender individuals and whose transphobia may lead to abuse:

“I worry about whether or not the people who are assisting me are going to be judgmental, are they going to be mean or be professional and take care of me like any other patient…Will I be abused in the nursing home because I am a trans person?” (Participant M, age 64, transgender man)

“They might take my hormones away. They might dress me in clothing the way that it appears as the birth sex. There are religious people who might harm me by withholding care due to their beliefs.” (Participant O, age 79, transgender man)

Isolation and loneliness exacerbated by transgender identity

Many participants expressed feelings of loneliness and isolation and often attributed this to their transgender identity, such as estrangement from spouses or family members. Several individuals noted that transgender people may face increased difficulty in finding romantic partners, due to partner discomfort with emotional or physical intimacy with a transgender person. One participant stated:

“[loneliness] can be more prevalent for trans people, because so many have had their families or partners abandon them and never rally back. They may have difficulty finding a partner who is comfortable with having a trans partner.” (Participant O, age 79, transgender man)

Difficulty finding romantic partners decreases likelihood of having children, further limiting possible sources of interpersonal support. Not being open about their transgender identity may lead to hesitancy in connecting with the transgender community and difficulty coming out in older age, further amplifying loneliness and isolation:

“Some of those people are coming out now at a much older age, but they may need trans community support. Some of them choose not to come out because they…may be isolated from the trans community.” (Participant S, age 68, transgender man)

Others noted the difficulties that lack of social support can create. Isolation can have detrimental effects on mental health and limit knowledge of and access to community resources. Stated simply by one participant:

“It's hard to be trans alone.” (Participant B, age 70, transgender woman)

Vulnerability to financial stressors

For some participants, job-seeking and financial security were primary concerns, both in their own lives and advice for others:

“Getting fired from jobs because I was transgender were not happy or expected things.” (Participant C, age 70, transgender man)

“I think economic security is a big deal. That is the one thing I don't have that I need to most.” (Participant N, age 71, transgender man)

Several participants offered ways that transgender individuals can counteract these challenges and create support networks from which to seek help during difficult times:

“The key to the whole thing is to have good relationships and good friends…having emotional support, physical support and support to getting things done. Having contacts and network to even getting a job.” (Participant E, age 76, transgender woman)

Perceived lack of agency

A fear of loss of agency and lack control over one's narrative were prevalent throughout conversations with participants. Many individuals felt that if they entered a nursing home, the manner in which they would be treated was largely out of their control, and would be determined by the knowledge and behaviors of staff. This extended beyond fear of physical mistreatment, to include the inability to live as their affirmed gender. As described by one participant:

“I can only hope that when that time comes, I will be in a facility where I am allowed to be who I am and that I will be treated with dignity.” (Participant I, age 76, transgender woman)

This fear of losing control also encompassed one's narrative as transgender. For many participants, preserving the truth of their transition and gender identity, both at the end of life and after death, was a vital component in their planning for old age. One participant expressed this concern in a conversation about funeral plans:

“I worry about how my family is going to bury me and how they are going to show me in my casket. When I die and I am buried, I would like to be as the female I have become now.” (Participant Q, age 67, transgender woman)

Considerations of remembrance after death also included fears that one's narrative might be amended or altered. For example, one participant stated:

I worry that they will immediately after I am gone…start assuming that I am not who I was. They might decide that I am some girl. (Participant N, age71, transgender man)

Fear of loss of control of one's mental capacity also arose in nearly every interview. This predominantly centered on concerns regarding dementia, and the impact dementia might have on one's agency and ability to continue living as a transgender person. Succinctly stated by one individual:

“It's the loss of independence and loss of control. The worse case scenario would be I would lose all control over my life, how I would dress and everything else.” (Participant I, age 76, transgender woman)

Health care system and provider inclusivity

While many participants reported currently having a transgender-care-competent primary care doctor, experiences of discrimination and insensitive medical care were common. These ranged from subtle microaggressions, such as body language suggestive of provider discomfort with caring for a transgender patient, to macroaggressions such as refusal to treat transgender patients. In describing her provider, one participant stated:

“There was nothing said but he was uncomfortable and it didn't make the patient comfortable either. So there are two things: it's what they might say and the other one is the body language.” (Participant A, age 82, transgender woman)

Several participants also noted that medical care has gradually become more inclusive of sexual and gender minorities over time. While some stories of discrimination in health care were recent, most occurred in decades before this study. Reflecting on these improvements, one individual commented:

“I have literally been escorted out of an Ob-Gyn office. I was almost dragged out and was told we don't see your kind here…The younger men and women now don't have to go through that.” (Participant R, age 72, transgender man)

Participants noted the ways in which health care infrastructure has become more welcoming to transgender individuals. These include the addition of preferred name and pronouns to electronic health records, transgender self-identification on patient intake forms, and diversity training for health care providers.

Giving back to one's community

While some participants recounted experiences of loneliness and isolation, others shared strong sentiments of community engagement and giving back to one's community. Some individuals felt that their profession allowed them to help others and provided a sense of purpose. As described by one individual:

“I work in psychiatry and there are so few practitioners. Some of the clients we serve are homeless people and 95% of them are drug and alcohol addicted. As long as I can work, I want to serve these people and it's like another life mission.” (Participant O, age 79, transgender man)

Others contributed specifically to the transgender community, through activism and support of the transgender movement. For some, financial support for the transgender movement has been a primary focus:

“Over the years, I have put about $200,000 or more into the trans movement. That was money spent to support the early organizations.” (Participant D, age 78, transgender woman).

One individual described support for the transgender movement through community building:

“I inherited a trans support group and newsletter that was vital to a small group of people before the internet…I worked really hard to build it into a global organization that supported all kinds of trans people on the masculine spectrum.” (Participant N, age 71, transgender man)

Other forms of giving back to the trans community included participation at academic conferences, collecting and publishing stories from transgender people, involvement in medical education and educating community organizations on topics of gender identity and transition.

Finally, several participants felt that transgender elders could support their communities through mentorship of younger individuals, especially transgender youth. In providing advice to transgender youth, one participant said:

“Nothing is impossible, if you put your mind to it. Set your goals high and always strive for those goals. If you fall short and don't achieve one or two goals, don't be upset. Go back, re-evaluate it and make a new list.” (Participant Q, age 67, transgender woman)

Embracing self-truth as a path to fulfillment

Whether in reflecting on their own lives or in providing advice to young trans people, a majority of participants highlighted the importance of embracing one's own identity as transgender. They found this to be a source of happiness and inner peace and for some individuals, a catalyst for improved mental health. One participant described the fulfillment that came with transitioning, and the respect this garnered from others:

“I have more respect now which is something I never had before transitioning…When I changed, everything changed. It definitely changed my life and made me be able to live instead of exist.” (Participant R, age 72, transgender man)

Some individuals described finding the ability to embrace their identity as they aged, while they were not able to earlier in life. For some, self-acceptance was one part of the wisdom they gained as they aged. In the words of two participants:

“I sat alone for a very long time. I was 63–1/2 years when I started to finally say enough is enough and I am coming out. Right now, I just know that everything is working toward what I know to be true about me.” (Participant G, age 65, transgender woman)

“I didn't know much at twenty…Over a period of time I became more comfortable with me, and especially after transitioning…The sooner that you're comfortable with who you are, you don't worry so much about what other people think.” (Participant A, age 82, transgender woman)

Discussion

This sample of transgender elders raised significant concerns regarding lack of social support and obtaining inclusive and dignified care as transgender people. These elders shared numerous accounts of fulfillment and pieces of advice for younger transgender and cisgender individuals alike. Many participants found joy in their journey of self-discovery and self-truth, which for some meant transitioning later in life. Although challenging for many, transitioning was described as a liberating experience that brought happiness, a renewed sense of self-confidence, connection to the LGBTQ community and improved mental health. This is consistent with prior research indicating that both surgical and medical transition among transgender individuals is associated with a sense of affirmation and lower rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideations.30–32 After transitioning, many participants also found fulfillment in giving back to their communities or the transgender community at large, and hoped to offer mentorship to young transgender people. While some themes described in this study have been documented by others, this desire to give back to one's community is a unique contribution to literature about transgender elders.

Nevertheless, the experience of transgender elders in this study has underscored ways in which both interactions with the health care system, and social determinants of health, can create barriers to health and well-being that extend beyond those faced by the general aging population. While many of these factors were described by Putney et al., only 6% of participants in that study identified as transgender, some participants were middle aged rather than elders (age 55–65), and data were gathered via focus groups.13 This study builds upon this work by providing data specific to individuals who are both transgender and elders, and gathered through one-on-one interviews. Participants in this study described struggling with common chronic conditions, such as osteoarthritis, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Given that in the United States, 86% of people older than the age of 65 years suffer from at least one chronic health condition, and this is not surprising.33 However, unique to this cohort are fears of mistreatment in institutional elder care programs due to gender identity, social isolation, and ostracization by friends and family due to transphobia and perceived lack of control over one's gendered narrative and identity as end of life approaches. Underlying each of these is anxiety and stress, the deleterious impact of which on minority groups is well described.34–36 In describing interactions with health care providers, participants in the current study recounted stories of dismissive and discriminatory practices, tempered by significant improvements in health care inclusivity in recent years. Other qualitative studies have found that navigating discrimination is a common theme for LGBTQ individuals, which engenders an erosion of trust in the medical profession and hesitancy in disclosing gender identity and sexual orientation.37 Unfortunately, a 2017 survey found that 37% of transgender individuals have delayed routine health care due to discrimination in their care.38 In addition, the experiences of hiring discrimination, financial hardship, difficulty finding romantic partners, and loneliness play pivotal roles in shaping the health of these individuals and lead to poorer health outcomes.39

This study is limited by the sample of transgender elders who cannot represent the experience of all transgender elders in the United States. This is an inherent limitation of both convenience and snowball sampling, as these methods cannot produce representative or random samples. Many of the study participants reside in Otsego County, New York, where 94% of residents identify as white.40 This racial composition is reflected in the study participants, who all were white. All were also able-bodied and generally healthy. This group is also likely more resource rich than many members of the transgender community, given that 53% of participants had some form of advanced degree (Master's or PhD), compared to 13% nationally according to one survey, and only 16% described themselves as having financial trouble.41 Nationally, ∼29% of transgender individuals live in poverty and nearly 30% have experienced homelessness.41 Thus, the fears and barriers to care expressed by this cohort are likely amplified among those transgender individuals with less access to financial and social resources. To verify this, future studies should include a more diverse sample of elders in terms of race, ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, and geographic location.

This study has implications for medical personnel and those who work with transgender individuals. Given the nearly unanimous fears and stories of mistreatment in elder care, additional training on sensitivity toward gender and sexual minorities would enhance the quality of care provided. Training might include practical skills, such as urinary catheterization of those who have undergone vaginoplasty or phalloplasty, as well as education about all forms of gender expression. Clinicians should initiate conversations with their transgender patients about such fears, particularly those who are being referred to nursing homes or rehabilitation facilities, and tailor their advanced directive documents to address these needs and fears, such as specifying preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity. The elder transgender community could also benefit from social programs that connect individuals to providers and elder care facilities knowledgeable in transgender care.

Conclusion

This qualitative research represents one of the first attempts to understand the needs of the elderly transgender community. While many of the concerns raised, such as fear of mistreatment, are not unique to transgender elders, they are likely heightened in this population due to overlapping areas of stigma, as both transgender and elderly. Health care workers must be trained in transgender care and sensitized to these concerns to provide appropriate care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Gender Wellness Center Community Research Advisory Team (CREATE) for rooting this study in the needs of the transgender community and helping to shape it from its beginning. We also thank the Gender Wellness Center staff for their role in recruiting many of the participants in this study. We thank the Bassett Medical Center Research Institute for supporting this study. Finally, we thank the participants for their vulnerability and honesty in sharing their experiences with us.

Abbreviations Used

- CREATE

Community Research Advisory Team

- GWC

Gender Wellness Center

- LGBTQ

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer or Questioning

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Cite this article as: Adan M, Scribani M, Tallman N, Wolf-Gould C, Campo-Engelstein L, Gadomski A (2021) Worry and wisdom: a qualitative study of transgender elders' perspectives on aging, Transgender Health 6:6, 332–342, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0098.

References

- 1. Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Commun. 2017;25:799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyer IH. Prejudice, Social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGovern J. The forgotten: dementia and the aging LGBT community. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker RV, Powers SM, Witten TM. Impact of anticipated bias from healthcare professionals on perceived successful aging among transgender and gender nonconforming older adults. LGBT Health. 2017;4:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dysart-Gale D. Social justice and social determinants of health: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, intersexed, and queer youth in Canada. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;23:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1820–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blosnich JR, Marsiglio MC, Dichter ME, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on medical conditions among transgender veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh G, Daus G, Allender M, et al. Social determinants of health in the United States: addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6:139–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kollia N, Caballero FF, Sánchez-Niubó A, et al. Social determinants, health status and 10-year mortality among 10,906 older adults from the English longitudinal study of aging: the ATHLOS project. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Northwood M, Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, Sherifali D. Integrative review of the social determinants of health in older adults with multimorbidity. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Podnieks E. Social inclusion: an interplay of the determinants of health—new insights into elder abuse. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;46:57–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Putney JM, Keary S, Hebert N, et al. “Fear Runs Deep”: the anticipated needs of LGBT older adults in long-term care. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61:887–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hafford-Letchfield T, Simpson P, Willis PB, Almack K. Developing inclusive residential care for older lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) people: an evaluation of the Care Home Challenge action research project. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Serafin J, Smith GB, Keltz T. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) elders in nursing homes: it's time to clean out the closet. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34:81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Shiu C, et al. Successful aging among lgbt older adults: physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. Gerontologist. 2015;55:154–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boggs JM, Dickman Portz J, King DK, et al. Perspectives of LGBTQ older adults on aging in place: a qualitative investigation. J Homosex. 2017;64:1539–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orel NA. Investigating the needs and concerns of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults: the use of qualitative and quantitative methodology. J Homosex. 2014;61:53–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Witten TM. End of life, chronic illness, and trans-identities. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2014;10:34–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J. The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults-an introduction to aging with pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). Gerontologist. 2017;57(Suppl 1):S1–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim HJ, et al. Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: an at-risk and underserved population. Gerontologist. 2014;54:488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoy-Ellis CP, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Depression among transgender older adults: general and minority stress. Am J Community Psychol. 2017;59:295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, et al. Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl 1):S63–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson K, Yarns BC, Abrams JM, et al. Gay and gray session: an interdisciplinary approach to transgender aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:719–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Henry RS, Perrin PB, Coston BM, Witten TM. Transgender and gender non-conforming adult preparedness for aging: concerns for aging, and familiarity with and engagement in planning behaviors. Int J Transgend Health. 2019;21:58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bloemen EM, Rosen T, LoFaso VM, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults' experiences with elder abuse and neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2338–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hash KM, Morrow DF. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons aging in rural areas. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2020;90:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004;99:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: a total population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;177:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Glynn TR, Gamarel KE, Kahler CW, et al. The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2016;3:336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parola N, Bonierbale M, Lemaire A, et al. Study of quality of life for transsexuals after hormonal and surgical reassignment. Sexologies. 2010;19:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Policy Data Requests—Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over with Chronic Conditions [Internet]. 2009. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm Accessed July 16, 2020.

- 34. Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63:985–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lefevor GT, Boyd-Rogers CC, Sprague BM, Janis RA. Health disparities between genderqueer, transgender, and cisgender individuals: an extension of minority stress theory. J Couns Psychol. 2019;66:385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malik S, Master Z, Parker W, et al. In our own words: a qualitative exploration of complex patient-provider interactions in an LGBTQ population. Can J Bioeth. 2019;2:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seelman KL, Colón-DIaz MJP, Lecroix RH, et al. Transgender noninclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgend Health. 2017;2:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA. 2016;316:1641–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Otsego County, New York [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/otsegocountynewyork Accessed October 19, 2020.

- 41. James S, Herman J, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey [Internet]. 2016. [cited July 16, 2020]. Available from: https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS Full Report-FINAL 1.6.17.pdf Accessed July 16, 2020.