Abstract

The recent proliferation of trans health literature for the past 20 years has prompted a need to examine two contested approaches used in designing study protocols and analyses in trans health research, as either specific to only one gender group (gender-specific approach) or across gender groups (i.e., gender-inclusive approach). In this critique, we aim to explicate and provide guidance for when the application of each approach is methodologically appropriate.

Keywords: gender-inclusive, gender-specific, survey design, survey methodology, transgender

Introduction

In efforts to conduct best practices in transgender (trans) health studies, researchers have trended into designing trans health studies with either gender-specific approaches, in which study participants of different gender identities are analyzed separately as distinct groups, or gender-inclusive approaches, in which participants of different gender identities are analyzed as one heterogeneous population. For example, study reviewers and journal editors often recommend separating out analysis between trans women and cisgender (nontransgender or cis) men (i.e., gender-specific), and yet consecutively suggest widening sampling strategies and analysis to include trans men and nonbinary people with trans women (i.e., gender-inclusive).

These two methodological approaches have remained contested given the proliferation of trans health literature recently,1 leaving researchers without any clear guidance for when to design trans health studies that are either gender-specific and gender-inclusive. In addition, relying on methodological conventions without critically examining their benefits and drawbacks may contribute to the well-documented history of trans erasure, oppression, and marginalization within research. Moreover, these ubiquitous erasures and oppressive practices to trans health research contribute to cisnormativity and cisgenderism (i.e., valuing, defaulting, and privileging cis researchers' vantage points), as reflected by the large volume of published studies by cis researches in this field—to the detriment of trans health.1

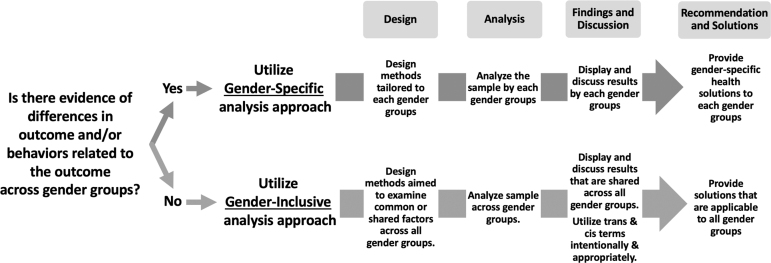

As such, there is a need to critically examine these methodological approaches. In this critique, we aim to explicate when these approaches are appropriate for designing trans health studies; we summarized our recommendations in Figure 1. These recommendations are applicable to quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research designs as it focuses on recruitment sampling and analytical approaches.

FIG. 1.

Recommended steps to applying gender-specific and gender-inclusive approaches.

Applying Gender-Specific Approach in Trans Health Research

Gender-specific approach to health promotion has conventionally been defined through experiences of cis populations as one that “acknowledges gender norms and targets women and men to achieve or meet their certain needs.”2 This approach has allotted researchers to design interventions specific to addressing health outcome(s) by gender, particularly when there is epidemiological evidence that such outcome for one group significantly differs from another group. Clinical trials such as the Women's Health Initiative3 and the Women's Health Study4 are some examples that have exclusively sampled cis women and provided evidence-based recommendations and solutions specifically for this gender group. In a similar vein, cis men's health needs have also been recognized using this approach, and The Young Men's Clinic5 in New York City and the Men who have sex with Men (MSM) Testing Initiative6 are some examples of research-based programs that are gender-specific for cis men.

A recent redefinition of the gender-specific approach extends acknowledgment of trans populations' health needs. It recognizes that trans populations consist of diverse and nonhomogenous groups who are behaviorally and culturally different from each other based on their trans identification. Within trans populations, there is an array of group-level gender identities that can be acknowledged as either gender binary (e.g., trans men and trans women) or nonbinary (e.g., genderqueer, gender fluid, and nonconforming).

Recent studies with disaggregated analyses show how health outcomes manifest differently across trans groups, revealing the health disparities that exist within trans populations. For example, one study examining intimate partner violence (IPV) showed that trans men experience significantly higher psychological and physical IPV compared with nonbinary individuals assigned male sex at birth (AMAB).7 Moreover, trans women have significantly higher trans-specific IPV in comparison with AMAB nonbinary individuals.7 These outcome differences across trans groups suggest the need for studies and interventions to be grounded in disaggregated epidemiological data that are gender-specific in its design, analysis, and recommendations.

An example area where this approach would be applicable is HIV prevention research, particularly in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trials. Epidemiological evidence has shown that trans women have lower PrEP uptake and adherence compared with other adult populations worldwide.8–10 Compared with cis MSM and cis women, research specific to trans women reveal this group's unique set of barriers such as concerns regarding PrEP provider's trans competency and potential drug-to-drug interaction with hormone therapy. However, as PrEP trials move to long-acting injectable modality, these trials continue to design studies with a gender-inclusive approach by recruiting trans women as a supplementary sample to cis MSM in the same study.11 Doing so undermines trans women's womanhood and introduces risks for providing recommendations that do not resonate with trans women.

Applying Gender-Inclusive Approach in Trans Health Research

In contrast to a gender-specific approach, researchers have utilized a gender-inclusive approach to health promotion. Gender-inclusive research recognizes and addresses gender-based health inequities present across genders. Inherent to the study of health disparities includes methodological steps to ensure sampling across gender groups. Clinical trials such as the Framingham Heart Study,12 for example, have recruited both cis women and cis men to understand which risk factors are common between gender groups that can be leveraged for intervention goals.

Another example of a gender-inclusive approach can be found in the public health literature on sex work, in which qualitative and quantitative studies are often designed with a mixed-gender approach that sample cis women, cis men sex workers, and their cis men clients.13–18 When these studies find unique issues to one group, such studies explicitly state the gender of sex workers/clients and consequently make gender-specific recommendations and solutions. For instance, stigma against same-sex behavior is more pronounced for cis men sex workers with cis men clients, whereas stigma against not being married impacts cis women sex workers more negatively in some parts of the world.19 When issues impact sex workers of both genders (e.g., discrimination based on sex work status), researchers simply conduct a gender-inclusive analysis and make recommendations (i.e., decriminalization of sex work) that would benefit both groups.

Applying a gender-inclusive approach could be beneficial in understanding health disparities that are shared across gender groups. Displaying study results together as shared experiences indicates that recommendations are not rooted in gender-based solutions, but rather are more specifically organized around larger structural and social factors in which these gender groups commonly are subjected to.

A Note on Intentional Labeling and Designing Studies Per Gender Group

Utilizing a gender-inclusive approach should not lead to the miscategorization of various gender groups. For example, trans women have historically been miscategorized with studies of cis MSM by public health surveillance systems and researchers, which erases trans women's experiences and conflates gender and sexual identities.20,21 Using a gender-inclusive approach should not be an attempt to replicate such practices of miscategorization and erasure. Instead, researchers should examine a shared public health issue between groups and work to understand whether there are health outcome differences to ensure that recommendations are appropriately either gender-specific or gender-inclusive. Researchers designing studies with more than one gender should strive to utilize best practices that do not undermine one gender group over another. For example, when applying a gender-inclusive approach involving trans women and cis MSM groups, researchers should be intentional in utilizing the term cisgender (e.g., cis MSM) throughout all aspects of the study to ensure sensitivity to the gender imbalance between trans and cis groups. Similarly, when examining and differentiating the health needs of trans women from those of cis women, it is important to distinguish unique and shared needs between these two groups. Recruitment strategies and study materials should also be tailored to each gender group, including achieving sample sizes that are well powered to conduct meaningful analyses by gender, particularly when recruiting within trans communities.22,23 For example, studies in which cis MSM and trans women are both eligible often recruit participants from LGBT social venues; however, these spaces disproportionately cater to cis MSM. As a result, the generalizability of these studies' findings may not extend to the proportion of trans women who do not frequent spaces that are assumed to primarily cater to cis MSM. The Transwomen Empowered to Advance Community Health study, conducted by the San Francisco Department of Public Health, is an example of a study that aptly applied a gender-specific approach.24 The researchers acknowledge that not only are the health needs of trans women different than other gender groups, but they also utilized respondent-driven sampling to intentionally recruit participants according to specific social networks, which allowed them access and ability to recruit marginalized participants who are part of a historically disenfranchised community.

Conclusion

The increase in research involving trans populations for the past 20 years has prompted a need to consider the approaches used to design study protocols and analyze data with members of this group. Gender-specific and gender-inclusive approaches represent two alternatives that researchers may consider. We recommend that when there is evidence of differences in outcomes and/or behaviors related to the outcome across gender groups, that a gender-specific approach be used. In turn, the findings of the study can provide gender-specific health solutions. When there is no evidence of gender-specific differences and a meaningful rationale for combining categories (e.g., due to upstream societal factors that similarly affect multiple groups), we recommend the use of a gender-inclusive approach, which can lead to health recommendations that are applicable to all (or multiple) gender groups. Neither is inherently correct. Researchers must consider the overarching research goal, scientific question, and gender-relevant clinical or social-behavioral phenomena that underpin the choice to include and analyze multiple genders versus focus on a specific gender. We also recommend that researchers clarify the intent of their investigation to justify the approach taken, as well as consider the limitations in their decision to either include multiple genders or target a specific gender. In doing this, we encourage and invite researchers to critically self-reflect and be accountable for how they and others may have contributed to erasures and oppressive histories by which trans “samples” and “communities” have been misrepresented through methodologies that are often conventionally and unquestionably conducted in trans health research, as well as examine what they can and must do to dismantle these methods and practices. Finally, as trans researchers are still underrepresented in academic research, we recommend that cis researchers conducting trans health research include and center trans community stakeholders and members, as well as trans researchers, in the development of their research.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, writing, and editing of this article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the authors are affiliated entities, namely Brown University School of Public Health, NIDA, NIAID, RWJF HPRS, and amfAR.

Abbreviations Used

- AMAB

assigned male sex at birth

- IPV

intimate partner violence

- LGBT

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study did not receive funding from agencies. Dr. Restar is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Dissertation Grant R36DA048682, and a recipient of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars (RWJF HPRS) Fellowship and the Public Policy Fellowship at amFAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research. Dr. Jin and Dr. Restar are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grant T32AI102623.

Cite this article as: Restar A, Jin H, Operario D (2021) Gender-inclusive and gender-specific approaches in trans health research, Transgender Health 6:5, 235–239, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0054.

References

- 1. Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature in transgender health (1900–2017). BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pederson A, Greaves L, Poole N. Gender-transformative health promotion for women: a framework for action. Health Promotion Int. 2014;30:140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Study TWsHI. Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rexrode KM, Lee I-M, Cook NR, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women's Health Study. J Womens Health Gender Based Med. 2000;9:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Armstrong B, Cohall AT, Vaughan RD, et al. Involving men in reproductive health: the Young Men's Clinic. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DiNenno E, Shouse L, Martin T, et al. The MSM Testing Initiative (MTI): innovative approaches for HIV testing and linkage to medical care. Atlanta: National HIV Prevention Conference, 2015;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. King WM, Restar A, Operario D. Exploring multiple forms of intimate partner violence in a gender and racially/ethnically diverse sample of transgender adults. J Interpers Violence. 2019;36:NP10477–NP10498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilson EC, Jin H, Liu A, Raymond HF. Knowledge, indications and willingness to take pre-exposure prophylaxis among transwomen in San Francisco, 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. HIV Prevention Trials Network. HPTN 083: a phase 2b/3 double blind safety and efficacy study of injectable cabotegravir compared to daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), for pre-exposure prophylaxis in HIV-uninfected cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men. 2017. Available at https://www.hptn.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/HPTN%20083_Final%20Version%202.0_25July2018.pdf Accessed May 21, 2019.

- 12. Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, et al. The third generation cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Syvertsen JL, Robertson AM, Abramovitz D, et al. Study protocol for the recruitment of female sex workers and their non-commercial partners into couple-based HIV research. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masvawure TB, Mantell JE, Tocco JU, et al. Intentional and unintentional condom breakage and slippage in the sexual interactions of female and male sex workers and clients in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valente PK, Mantell JE, Masvawure TB, et al. “I Couldn't Afford to Resist”: Condom Negotiations Between Male Sex Workers and Male Clients in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:925–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katsulis Y, Durfee A. Prevalence and correlates of sexual risk among male and female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. Global Public Health. 2012;7:367–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nyblade L, Reddy A, Mbote D, et al. The relationship between health worker stigma and uptake of HIV counseling and testing and utilization of non-HIV health services: the experience of male and female sex workers in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre-and post-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) among female and male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: implications for integrating biomedical prevention into sexual health services. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29:141–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okal J, Chersich MF, Tsui S, et al. Sexual and physical violence against female sex workers in Kenya: a qualitative enquiry. AIDS Care. 2011;23:612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tordoff D, Andrasik M, Hajat A. Misclassification of sex assigned at birth in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and transgender reproductive health: a quantitative bias analysis. Epidemiology. 2019;30:669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poteat T, German D, Flynn C. The conflation of gender and sex: gaps and opportunities in HIV data among transgender women and MSM. Global Public Health. 2016;11:835–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tebbe EA, Budge SL. Research with trans communities: applying a process-oriented approach to methodological considerations and research recommendations. Counsel Psychol. 2016;44:996–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tebbe EA, Moradi B, Budge SL. Enhancing scholarship focused on trans people and issues. Counsel Psychol. 2016;44:950–959. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baguso GN, Turner CM, Santos GM, et al. Successes and final challenges along the HIV care continuum with transwomen in San Francisco. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]