ABSTRACT

Objective:

To examine the impact of hypertension on cardiovascular health in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease and to identify factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study including 251 patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (63.9% males, mean age 67±10 years). Following hypertension diagnosis, blood pressure was measured to determine control of hypertension. Arterial stiffness (carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity) and cardiac autonomic modulation (sympathovagal balance) were assessed.

Results:

Hypertension was associated with higher carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, regardless of sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, walking capacity, heart rate, or comorbidities (ß=2.59±0.76m/s, b=0.318, p=0.003). Patients with systolic blood pressure ≥120mmHg had higher carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity values than normotensive individuals, and hypertensive patients with systolic blood pressure of ≤119mmHg (normotensive: 7.6±2.4m/s=≤119mmHg: 8.1±2.2m/s 120-129mmHg:9.8±2.6m/s=≥130mmHg: 9.9±2.9m/s, p<0.005). Sympathovagal balance was not associated with hypertension (p>0.05).

Conclusion:

Hypertensive patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease have increased arterial stiffness. Arterial stiffness is even greater in patients with uncontrolled high blood pressure.

Keywords: Intermittent claudication, Peripheral arterial disease, Comorbidity, Cardiovascular system, Vascular stiffness, Hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) affects more than 200 million people worldwide.(1) Hypertension is one of the most prevalent risk factors for PAD, affecting approximately 80% of patients.(2–4) It is directly related to fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events in this patient population.(5).

Blood pressure control (i.e., systolic blood pressure <140mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <90mmHg) is thought to be a cornerstone of hypertension management.(6) In fact, a prior study(7) showed that blood pressure control can decrease the incidence of cardiovascular disease and overall mortality by 33% (from 3.85% to 2.59% per year) and 32% (from 2.63% to 1.78% per year), respectively. However, associations between hypertension control and cardiovascular function in patients with PAD remain to be determined.

Deeper understanding of the impact of controlled and uncontrolled hypertension on cardiovascular health may assist physicians in managing cardiovascular health, with potential contributions to the survival of patients with PAD. Factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension in patients with PAD are worthy of investigation.

OBJECTIVES

To examine the impact of hypertension on cardiovascular health in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease, and to identify factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension.

METHODS

Recruitment and patients

This cross-sectional study followed (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist.(8)Patients with PAD were recruited from vascular units in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Inclusion criteria were patients aged 40 to 90 years with symptomatic PAD (ankle-brachial index ≤0.90) in one or both legs, absence of critical limb ischemia, rest pain, noncompressible vessels, no limb amputation, or ulcers. Compliance with study criteria was checked by preliminary evaluations.

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo(HCFMUSP), protocol 3.986.124, CAAE: 42379015.3.3002.0068 and of Hospital Albert Einstein(HIAE), protocol 3.959.548, CAAE: 42379015.3.0000.0071. Patients were duly informed of study risks and benefits and gave their written informed consent for participation. Data collection was performed between September 2015 and December 2017.

Cardiovascular measurements

Measurements were made in a quiet environment. Blood pressure and arterial stiffness were measured with patients in the seated and the supine position, respectively. Patients were instructed to avoid moderate to vigorous physical activity for a minimum of 24 hours prior to the visit, and to avoid smoking, alcohol and caffeine intake for a minimum of 12 hours prior to measurements. Data were collected by blinded investigators.

Hypertension (predictors)

Patients taking antihypertensive drugs and with systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥90mmHg were defined as hypertensive. Blood pressure was measured in both arms using an automatic device HEM-742-E (Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Three consecutive blood pressure readings were taken at one-minute intervals, as described elsewhere.(9)Higher readings were used in the analysis. Patients systolic blood pressure <140mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <90mmHg were allocated to the controlled group. Patients with blood pressure values higher than those established for the controlled group were allocated to the uncontrolled group.(6)Intraclass correlation coefficient for systolic and diastolic blood pressure was 0.85 and 0.92, respectively.(10)

Arterial stiffness (outcome)

Carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV) was used to assess arterial stiffness. Measurements were made using a high-fidelity applanation tonometer (Sphygmocor, ATCOR Medical, Australia), in compliance with Clinical Application of Arterial Stiffness Task Force III(11) and American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Recommendations for Improving and Standardizing Vascular Research on Arterial Stiffness(12) guidelines. The intraclass correlation coefficient for cfPWV was 0.91.(10)

Cardiac autonomic modulation (outcome)

Cardiac autonomic modulation assessment was based on heart rate variability analysis, as per previously described procedures.(9) Inter-beat (RR) intervals were obtained using a heart rate monitor (V800, Polar® Electro, Oulu, Finland); a minimum of five minutes of stationary RR interval data were used. Frequency domain variables were calculated using the autoregressive method. Signals operating at frequencies between 0.04 and 0.4Hz were considered physiologically significant. Low (LF) and high (HF) frequency components were represented by oscillations ranging from 0.04 to 0.15Hz and 0.15 to 0.4Hz, respectively. The LF/HF ratio was defined as the cardiac sympathovagal balance. Analyses were performed using Kubios HRV software (Biosignal Analysis and Medical Imaging Group, Joensuu, Finland). Task Force for Heart Rate Variability recommendations were followed.(13)

Covariates

Demographic data (age and sex), ankle-brachial index, comorbidities (diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease and dyslipidemia), walking capacity, heart rate, and body mass index were assessed at the beginning of the study, using previously described procedures.(9,14) Interarm blood pressure differences >10mmHg were considered to be indicative of upper extremity PAD.(15)

Statistical analysis

Data normality and homogeneity were checked using the Kolmogorov Smirnov and the Levene test respectively. For descriptive statistics, continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were summarized as relative frequency. Linear regression models were used to investigate associations between cardiovascular variables (arterial stiffness and cardiac autonomic modulation) and hypertension. Crude analyses were performed first, then adjusted for classical confounding variables. Residual analysis was performed and homoscedasticity examined using graphical analysis (scatterplots). Multicollinearity analysis was conducted assuming variance inflation factors of less than than 5, and tolerance values of less than 0.20.

One-way ANOVA was used to compare cfPWV values between normotensive and hypertensive patients (≤119mmHg; 120-129mmHg and ≥130mmHg). Multiple logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension in patients with PAD. Variables with a p value <0.30 in bivariate analysis were included in the model, and only those with a p value <0.10 retained in the final model. Model goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to examine the relation between systolic blood pressure and cfPWV. The level of significance was set at 5% (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Out of 261 patients enrolled in this study, 10 were excluded due to missing blood pressure data. The final sample comprised 251 patients with PAD whose data were available for analysis. All patients had moderate PAD, and 24.8% had signs suggestive of upper extremity PAD. Mean body mass index was 27.4±6.3kg/m². Hypertension was diagnosed in 89.6% patients, of whom 50.2% had uncontrolled hypertension. Clinical characteristics of patients with controlled or uncontrolled hypertension are shown in table 1. More frequent use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE), older age, and higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure values were more prevalent among patients with uncontrolled hypertension relative to patients with controlled hypertension (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of general characteristics of patients with peripheral artery disease and controlled or uncontrolled hypertension.

| Variables | Controlled hypertension | Uncontrolled hypertension | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and demographic variables | ||||

| Male sex (%) | (53.6) | (46.4) | 0.130 | |

| Age (years) | 65±10 | 69±8 | 0.001 | |

| Ankle-brachial index | 0.60±0.19 | 0.57±0.16 | 0.245 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | 28.0±4.9 | 27.4±4.7 | 0.342 | |

| Claudication distance (m) | 133±85 | 125±68 | 0.465 | |

| Six-minute walk test (m) | 326±91 | 318±85 | 0.531 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 121±12 | 158±15 | <0.001 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69±10 | 78±10 | <0.001 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Current smoker (%) | (42.9) | (57.1) | 0.334 | |

| Diabetes (%) | (48.4) | (51.7) | 0.633 | |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | (53.2) | (46.8) | 0.056 | |

| Obesity (%) | (52.6) | (47.4) | 0.642 | |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | (55.6) | (44.4) | 0.241 | |

| Stroke (%) | (56.1) | (43.9) | 0.806 | |

| Medications | ||||

| Antiplatelet | (51.2) | (48.8) | 0.949 | |

| ACE inhibitor (%) | (64.9) | (35.1) | 0.018 | |

| Angiotensin-receptor antagonist (%) | (48.4) | (51.6) | 0.579 | |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) | (47.5) | (52.5) | 0.481 | |

| Diuretic (%) | (45.5) | (54.5) | 0.152 | |

| Beta-blocker (%) | (51.6) | (48.4) | 0.924 | |

| Statin (%) | (53.2) | (46.8) | 0.137 | |

| Hypoglycemic (%) | (47.7) | (52.3) | 0.371 | |

| Peripheral vasodilator (%) | (58.5) | (41.5) | 0.219 | |

| ACE inhibitor + diuretic + calcium channel blocker (%) | (53.8) | (46.2) | 0.904 | |

Values expressed as median±interquartile range and frequency.

ACE: angiotensin conversion enzyme.

Associations between hypertension and cardiovascular variables are shown in table 2. Hypertension was associated with higher cfPWV, regardless of sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, walking capacity, heart rate or comorbidities (p<0.05). Hypertension was not associated with cardiac autonomic modulation (p>0.05).

Table 2. Association between hypertension and cardiovascular variables in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease.

| Independent variable β(SE) | cfPWV(m/s) | LF/HF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β(SE) | B | β(SE) | b | ||

| Hypertension (no=0, yes=1) | Crude | 1.61 (0.66) | 0.184* | -0.70 (0.39) | -0.157 |

| Adjusted | 2.37 (0.87) | 0.248* | 0.13 (0.85) | 0.014 | |

p<0.05. Model for cfPWV: adjusted for sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, six-minute walk test, heart rate, diabetes, obesity, coronary artery disease, stroke and dyslipidemia. Model for LF/HF: adjusted for sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, six-minute walk test, diabetes, obesity, coronary artery disease, stroke, and dyslipidemia.

cfPWV: carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; LF: low frequency; HF: sympathovagal balance; SE: standard error;

b: standardized beta coefficients.

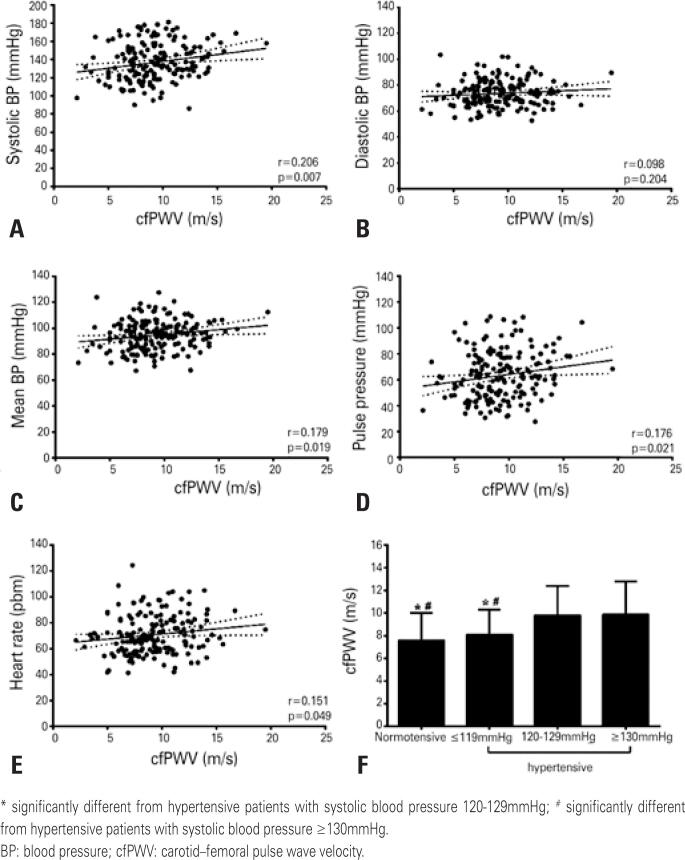

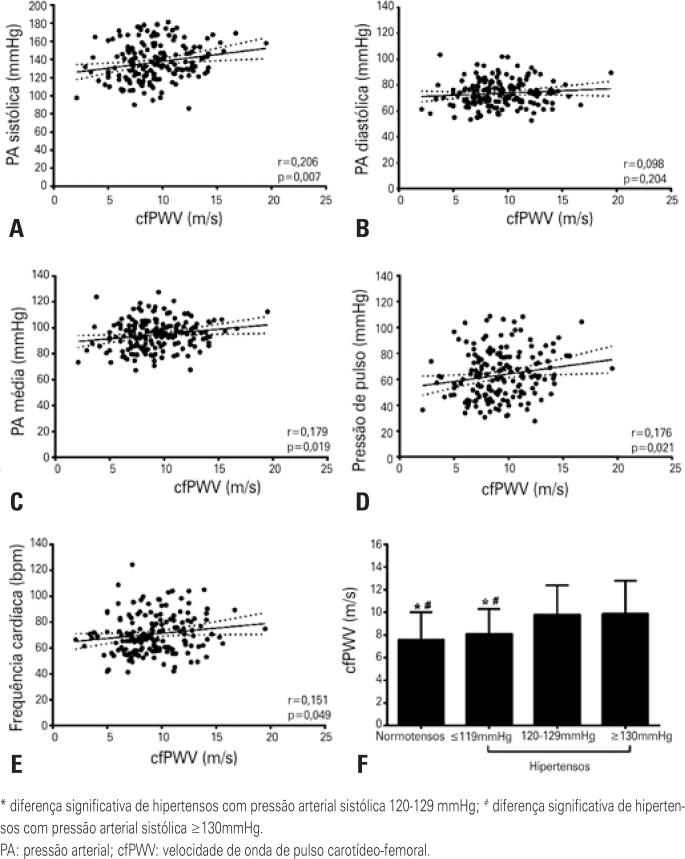

Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean blood pressure, heart rate and pulse pressure were positively correlated with cfPWV (Figures 1A-1E). Patients with PAD and systolic blood pressure ≥120mmHg had higher cfPWV than normotensive or hypertensive patients with systolic blood pressure ≤119mmHg (normotensive: 7.6±2.4m/s; systolic blood pressure ≤119mmHg: 8.1±2.2m/s; systolic blood pressure 120-129mmHg: 9.8±2.6m/s; systolic blood pressure ≥130mmHg: 9.9±2.9m/s; p<0.005) (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. Correlations between systolic blood pressure (A); diastolic blood pressure (B); mean blood pressure (C); pulse pressure (D); heart rate (E) and carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity; comparison of arterial stiffness between normotensive and hypertensive patients with systolic blood pressure of ≤119mmHg, 120-129mmHg, and ≥130mmHg (F).

Older age, lower ankle-brachial index and no use of ACEi were associated with uncontrolled hypertension, based on regression analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension in patients with peripheral artery disease.

| Dependent variables | Independent variables | OR (95%CI) | β (SE) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled hypertension (no=0, yes=1) | Age (years) | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) | 0.061 (0.019) | 0.001 |

| Ankle-brachial index | 0.14 (0.02-0.88) | -1.975 (0.941) | 0.036 | |

| Use of ACEi (ref=no) | 0.38 (0.19-0.76) | -0.970 (0.365) | 0.008 | |

| Dyslipidemia (ref=no) | 0.42 (0.16-1.05) | -0.878 (0.475) | 0.065 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow test: χ²=7.599; p=0.474.

OR: odds ratio; SE: standard-error; β: regression coefficient; ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

In this study, hypertension was associated with greater arterial stiffness in patients with PAD, regardless of sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, walking capacity, heart rate or comorbidities. Arterial stiffness was also greater in hypertensive patients with PAD and systolic blood pressure ≥120mmHg than in normotensive and hypertensive patients with PAD and systolic blood pressure ≤119mmHg. Older age, lower ankle–brachial index, and no use of ACEi were associated with uncontrolled hypertension in patients with PAD.

Prior studies have shown that hypertension is the most prevalent comorbidity in patients with PAD.(2–4) This analysis revealed similar findings. The prevalence of hypertension was associated with increased arterial stiffness, even after adjustment for confounding factors, as reported in other studies investigating patients with hypertension and diabetes.(16,17) From a clinical standpoint, these are relevant findings, since increased arterial stiffness is associated with poorer cardiovascular outcomes, regardless of traditional risk factors.

Arterial stiffness plays a key role in the pathophysiology of hypertension.(18,19) It is also strongly related to atherosclerosis development and should, therefore, be considered a significant clinical marker in patients with PAD.(20,21) The median cfPWV value was 2.4m/s higher in hypertensive relative to normotensive patients with PAD. This implies a higher cardiovascular risk, given a 1m/s increase in cfPWV is associated with a 14% increase in the odds of having a cardiovascular event and a 15% increase in cardiovascular mortality.(22)

Patients with controlled hypertension had lower cfPWV values than those with uncontrolled hypertension, suggesting interventions aimed to reducing cfPWV may benefit patients with PAD. For example, medications with proven ability to decrease arterial stiffening, particularly ACEi and calcium channel blockers,(23) have a positive effect on aortic stiffness. In addition to drug treatment, lifestyle modifications, such as physical activity, should be recommended to reduce blood pressure.

Sympathovagal balance of 2.0 in patients with PAD in this study indicated a shift in cardiac autonomic modulation towards increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic modulation. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere.(24,25)Increased sympathetic and decreased cardiac parasympathetic modulation are thought to be important predictors of fatal and nonfatal cardiac events.(26) Data in this study failed to reveal a relation between hypertension and sympathovagal balance. This may seem odd at first, since patients with hypertension have an autonomic dysfunction.(13) However, half of patients were taking beta-blockers. Beta-blockers upregulate the fractal behavior of cardiac autonomic modulation in patients with cardiovascular diseases,(27,28) allowing for better cardiovascular control.

In the current study, advanced age, lower ankle-brachial index and no use of ACEi, were associated with uncontrolled hypertension in patients with PAD. Likewise, previous studies revealed lower ankle-brachial index, greater impairment of walking capacity,(29) poor fitness,(29)low levels of physical activity,(30,31)and more barriers to physical activity, in older patients.(3,32) These variables are classic predictors of good cardiovascular health.(33) Uncontrolled hypertension was also more likely among patients who did not use ACEi. According to a review study,(34) renin-angiotensin system blockers, especially angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor inhibitors, may effectively reduce the risk of cardiovascular ischemic events in patients with PAD.

Findings of this study have important practical implications. For example, systolic blood pressure <140mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <90mmHg (i.e., controlled blood pressure) are thought to be cornerstones of hypertensive patient management.(6) Hypertension was associated with increased arterial stiffness, regardless of sex, age, ankle-brachial index, body mass index, walking capacity, heart rate or comorbidities. However, hypertensive patients with systolic blood pressure ≤119mmHg had better vascular health (lower arterial stiffness). Therefore, these values should be accounted for in the establishment of therapeutic goals, as suggested in American guidelines,(35)is spite of divergences from Brazilian(6) and European guidelines.(36)

This study has limitations. Firstly, cross-sectional study design precludes causal inference. Therefore, longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate mechanisms responsible for the associations detected. Secondly, only patients with symptomatic PAD were included. Hence, findings cannot be extrapolated to patients with other stages of the disease. Thirdly, small sample size and the fact that patients were using different drugs may have impacted cardiovascular variables, and stratified analysis according to type of medication was not possible. Finally, biomarkers were not measured, which limits the understanding of mechanisms underlying the associations reported, as well as the extrapolation of findings to other patients.

CONCLUSION

Hypertension was associated with increased arterial stiffness in patients with PAD. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension had greater arterial stiffness. These findings underscore the significance of blood pressure control in these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Gabriel Grizzo Cucato has a grant from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq number 409707/2016-3). Raphael Mendes Ritti-Dias has a research productivity fellowship (PQ-1D) granted by CNPq. We also thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329-40. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Farah BQ, Ritti-Dias RM, Cucato GG, Montgomery PS, Gardner AW. Factors associated with sedentary behavior in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52(6):809-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Cavalcante BR, Farah BQ, Barbosa JP, Cucato GG, Chehuen MR, Santana FS, et al. Are the barriers for physical activity practice equal for all peripheral artery disease patients? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(2):248-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Farah BQ, Ritti-Dias RM, Cucato GG, Chehuen MR, Barbosa JP, Zeratti AE, et al. Effects of clustered comorbid conditions on walking capacity in patients with peripheral artery disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(2):279-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hackl G, Jud P, Avian A, Gary T, Deutschmann H, Seinost G, et al. COPART risk score, endothelial dysfunction, and arterial hypertension are independent risk factors for mortality in claudicants. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016; 52(2):211-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barroso WK, Rodrigues CI, Bortolotto LA, Mota-Gomes MA, Brandão AA, Feitosa AD, et al. Brazilian Guidelines of Hypertension - 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):516-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Campbell RC, Chertow Fine LJ, Haley WE, Hawfield AT, Ix JH, Kitzman DW, Kostis JB, Krousel-Wood MA, Launer LJ, Oparil S, Rodriguez CJ, Roumie CL, Shorr RI, Sink KM, Wadley VG, Whelton PK, Whittle J, Woolard NF, Wright JT Jr, Pajewski NM; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke J; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Farah BQ, Rigoni VL, Correia MA, Wolosker N, Puech-Leao P, Cucato GG, et al. Influence of smoking on physical function, physical activity, and cardiovascular health parameters in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: a cross-sectional study. J Vasc Nurs. 2019;37(2):106-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gerage AM, Benedetti TR, Farah BQ, Santana FS, Ohara D, Andersen LB, et al. Sedentary behavior and light physical activity are associated with brachial and central blood pressure in hypertensive patients. PloS One. 2015;10(12):e0146078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Van Bortel LM, Duprez D, Starmans-Kool MJ, Safar ME, Giannattasio C, Cockcroft J, et al. Clinical applications of arterial stiffness, Task Force III: recommendations for user procedures. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(5):445-52. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Townsend RR, Wilkinson IB, Schiffrin EL, Avolio AP, Chirinos JA, Cockcroft JR, Heffernan KS, Lakatta EG, McEniery CM, Mitchell GF, Najjar SS, Nichols WW, Urbina EM, Weber T; American Heart Association Council on Hypertension. Recommendations for improving and standardizing vascular research on arterial stiffness. a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):698-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(3):354-81. [PubMed]

- 14.de Sousa AS, Correia MA, Farah BQ, Saes G, Zerati AE, Puech-Leao P, et al. Barriers and levels of physical activity in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: comparison between women and men. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(5):719-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Santini L, Almeida Correia M, Oliveira PL, Puech-Leao P, Wolosker N, Cucato GG, et al. Functional and cardiovascular parameters in peripheral artery disease patients with interarm blood pressure difference. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;70:355-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Smulyan H, Lieber A, Safar ME. Hypertension, diabetes type ii, and their association: role of arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(1):5-13. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Maruhashi T, Kinoshita Y, Kajikawa M, Kishimoto S, Matsui S, Hashimoto H, Takaeko Y, Aibara Y, Yusoff FM, Hidaka T, Chayama K, Noma K, Nakashima A, Goto C, Takahashi M, Kihara Y, Higashi Y; Hiroshima NOCTURNE Research Group. Relationship between home blood pressure and vascular function in patients receiving antihypertensive drug treatment. Hypertens Res. 2019;42(8):1175-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, et al. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001;37(5):1236-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lim J, Pearman ME, Park W, Alkatan M, Machin DR, Tanaka H. Impact of blood pressure perturbations on arterial stiffness. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309(12):R1540-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Husmann M, Jacomella V, Thalhammer C, Amann-Vesti BR. Markers of arterial stiffness in peripheral arterial disease. Vasa. 2015;44(5):341-8. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Palombo C, Kozakova M. Arterial stiffness, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiologic mechanisms and emerging clinical indications. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016;77:1-7. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(13):1318-27. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Protogerou AD, Papaioannou TG, Lekakis JP, Blacher J, Safar ME. The effect of antihypertensive drugs on central blood pressure beyond peripheral blood pressure. Part I: (Patho)-physiology, rationale and perspective on pulse pressure amplification. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(3):267-71. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Andrade-Lima AH, Farah BQ, Rodrigues LB, Miranda AS, Rodrigues SL, Correia MA, et al. Low-intensity resistance exercise does not affect cardiac autonomic modulation in patients with peripheral artery disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013;68(5): 632-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Andrade-Lima AH, Soares AH, Cucato GG, Leicht AS, Franco FG, Wolosker N, et al. Walking capacity is positively related with heart rate variability in symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52(1):82-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Tsuji H, Larson MG, Venditti FJ Jr, Manders ES, Evans JC, Feldman CL, et al. Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1996;94(11):2850-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Lin LY, Lin JL, Du CC, Lai LP, Tseng YZ, Huang SK. Reversal of deteriorated fractal behavior of heart rate variability by beta-blocker therapy in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(1):26-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lampert R, Ickovics JR, Viscoli CJ, Horwitz RI, Lee FA. Effects of propranolol on recovery of heart rate variability following acute myocardial infarction and relation to outcome in the Beta-Blocker Heart Attack Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(2):137-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Gardner AW. Sex differences in claudication pain in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(11):1695-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Gerage AM, Correia MA, Oliveira PM, Palmeira AC, Domingues WJ, Zeratti AE, et al. Physical activity levels in peripheral artery disease patients. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(3):410-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Barbosa JP, Farah BQ, Chehuen M, Cucato GG, Farias Júnior JC, Wolosker N, et al. Barriers to physical activity in patients with intermittent claudication. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(1):70-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Sousa AS, Correia MA, Farah BQ, Saes G, Zerati AE, Puech-Leao P, et al. Barriers and levels of physical activity in symptomatic peripheral artery disease patients: comparison between women and men. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(5):719-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Emrich IE, Böhm M, Mahfoud F. The 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: a German point of view. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(23):1830-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Tsioufis C, Andrikou I, Siasos G, Filis K, Tousoulis D. Anti-hypertensive treatment in peripheral artery disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2018;39:35-42. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138(17):e426-e83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement D, Coca A, De Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen S, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GY, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder R, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis K, Aboyans V, Desormais I; List of authors/Task Force members: 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology: ESH/ESC task force for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(12):2284-309. Erratum in: J Hypertens. 2019;37(2):456.