ABSTRACT

Objective:

To describe clinical characteristics, resource use, outcomes, and to identify predictors of in-hospital mortality of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit.

Methods:

Retrospective single-center cohort study conducted at a private hospital in São Paulo (SP), Brazil. All consecutive adult (≥18 years) patients admitted to the intensive care unit, between March 4, 2020 and February 28, 2021 were included in this study. Patients were categorized between survivors and non-survivors according to hospital discharge.

Results:

During the study period, 1,296 patients [median (interquartile range) age: 66 (53-77) years] with COVID-19 were admitted to the intensive care unit. Out of those, 170 (13.6%) died at hospital (non-survivors) and 1,078 (86.4%) were discharged (survivors). Compared to survivors, non-survivors were older [80 (70-88) versus 63 (50-74) years; p<0.001], had a higher Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 [59 (54-66) versus 47 (42-53) points; p<0.001], and presented comorbidities more frequently. During the intensive care unit stay, 56.6% of patients received noninvasive ventilation, 32.9% received mechanical ventilation, 31.3% used high flow nasal cannula, 11.7% received renal replacement therapy, and 1.5% used extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Independent predictors of in-hospital mortality included age, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, Charlson Comorbidity Index, need for mechanical ventilation, high flow nasal cannula, renal replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support.

Conclusion:

Patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit exhibited a considerable morbidity and mortality, demanding substantial organ support, and prolonged intensive care unit and hospital stay.

Keywords: Coronavirus; COVID-19; Coronavirus infections; SARS-CoV-2; Betacoronavirus; Intensive care units; Respiration, artificial; Noninvasive ventilation; Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Critical care outcomes; Mortality

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease that was first reported in Wuhan, China, and has subsequently spread worldwide.(1) Although most of the infected patients develop only mild symptoms, approximately 15% of symptomatic patients will require hospitalization,(2) and almost 20% of hospitalized patients will require intensive care unit (ICU) admission due to progression to acute respiratory failure (ARF).(3,4)

Advanced age, male sex, obesity, systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiovascular disease are major risk factors for severe COVID-19.(5-8) Critically ill patients with COVID-19 require substantial organ support and prolonged ICU stay.(9) For instance, a systematic review including 16,561 critically ill COVID-19 patients demonstrated approximately 76% of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), two thirds of patients used mechanical ventilation, and 17% of them required renal replacement therapy (RRT).(9)

The first case of COVID-19 in Brazil was confirmed at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein (HIAE), on February 26, 2020.(2) Up to June 2021, more than 16 million cases and 500 thousand deaths due to COVID-19 had been registered in Brazil.(10) Nevertheless, few studies reported on epidemiology, clinical characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of ICU patients with COVID-19, in Brazil.(11-14)

OBJECTIVE

To describe clinical characteristics, resource use, outcomes, and to identify predictors of in-hospital mortality of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a single center retrospective cohort study. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee at HIAE with waiver of Informed Consent (CAAE: 30797520.6.0000.0071, protocol number: 4.562.815). This study is reported in accordance with the effort Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).(15)

Setting

This study was conducted in a private quaternary care hospital located in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. The HIAE comprises 634 beds. Out of those, 37 were open medical-surgical adult ICU beds and 81 were adult step-down unit beds. During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the total ICU operational capacity was increased, reaching 81 ICU beds designated to support severe COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care.

Study participants

Consecutive adult (≥18 years) patients admitted to the ICU, from March 4, 2020 to February 28, 2021 and diagnosed with COVID-19 were eligible for inclusion in this study. Laboratory confirmation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was based on positive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay (Cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Test, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, United States).(16)

Patient management

Criteria for ICU admission and the institutional protocol for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection management have been published elsewhere.(17,18)

Data collection and study variables

All study data were retrieved from Epimed Monitor system (Epimed Solutions, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), which is an electronic structured case report form, in which patients’ data are prospectively entered by trained ICU case managers.(19) Collected variables included demographics, comorbidities, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS 3)(20) at ICU admission, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)(21) at ICU admission, Charlson Comorbidity Index,(22) modified frailty index (MFI),(23) resource use and organ support (vasopressors, noninvasive ventilation, high flow nasal cannula – HFNC –, mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation – ECMO), during ICU stay, destination at hospital discharge, ICU and hospital length of stay, and ICU and in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR). Normality was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

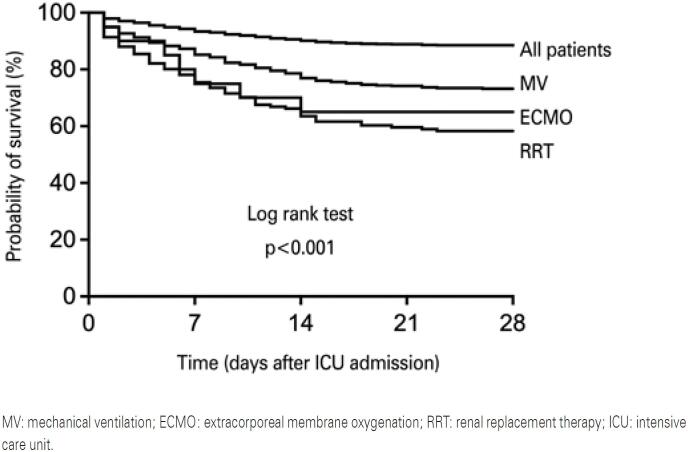

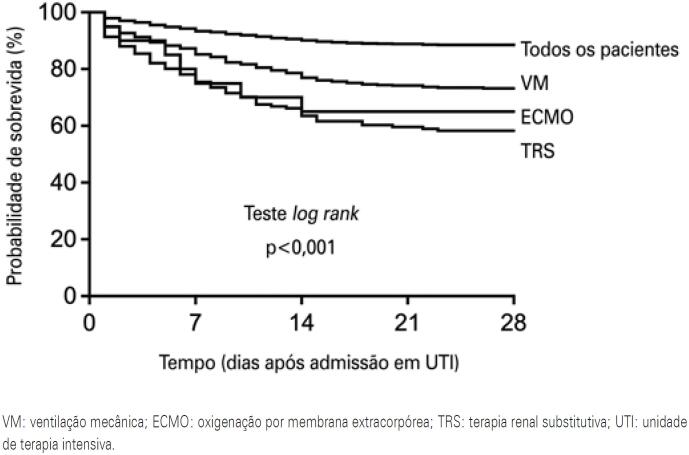

Comparisons were made between survivors and non-survivors, based on in-hospital mortality. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, when appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using independent t test, or Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-normal distribution. Survival at day 28 of pooled patients, and survival stratified according to the use of mechanical ventilation, RRT and ECMO, were analyzed by means of the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients discharged from hospital before 28 days were considered alive at day 28.

Univariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify which predictors were associated with in-hospital mortality. Multivariable logistic regression analyses with backward elimination procedure, including all the predictors showing a p-value <0.10 in the univariable analysis, were undertaken to obtain adjusted odds ratio (OR), along with 95% confidence interval (95%CI), and to define which variables were independently associated with in-hospital mortality. We tested the linearity assumption for continuous variables included in logistic regression models by analyzing the interaction between each predictor and its own log (natural log transformation).(24) Whenever the linearity assumption was violated, continuous variables were categorized. Final multivariable logistic regression model discrimination (area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve – AUC) and calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 statistic) were reported.(25)

Two-tailed tests were used, and considered statistically significant when p<0.05. All analyses were performed using IBM (SPSS) for Macintosh, version 27.0., and GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, California, United States) was used for graph plotting.

RESULTS

Cohort included

Between March 4, 2020 and February 28, 2021, 1,296 patients with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 were admitted to the ICU. Out of those, 170 (13.6%) died at hospital (non-survivors) and 1.078 (86.4%) were discharged alive from the hospital (survivors). By the time data were extracted (March 9, 2021), 48 patients were still hospitalized. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of studied patients according to in-hospital mortality.

| Characteristics | All patients 1,296 (100%)* |

Survivors 1,078/1,248 (86.4%) |

Non-survivors 170/1,248 (13.6%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 (53-77) | 63 (50-74) | 80 (70-88) | <0.001† | |

| Men | 862/1,296 (66.5) | 718/1,078 (66.6) | 109/170 (64.1) | 0.582‡ | |

| SAPS 3 | 49 (42-56) | 47 (42-53) | 59 (54-66) | <0.001† | |

| SOFA | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-3) | 6 (4-9) | <0.001† | |

| CCI | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 2 (1-3) | <0.001† | |

| MFI, points | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (1-3) | <0.001† | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 607/1,022 (59.4) | 484/814 (59.5) | 97/164 (59.1) | 1.000‡ | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 366/1,022 (35.8) | 286/814 (35.1) | 64/164 (39.0) | 0.391‡ | |

| Obesity | 320/1,043 (30.7) | 265/857 (30.9) | 47/146 (32.2) | 0.834‡ | |

| Asthma | 84/1,022 (8.2) | 70/814 (8.6) | 10/164 (6.1) | 0.363‡ | |

| Cancer | 80/1,022 (7.8) | 55/814 (6.8) | 21/164 (12.8) | 0.013‡ | |

| Congestive heart failure | 74/1,022 (7.2) | 46/814 (5.7) | 25/164 (15.2) | <0.001‡ | |

| COPD | 74/1,022 (7.2) | 52/814 (6.4) | 17/164 (10.4) | 0.099‡ | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 56/1,022 (5.5) | 32/814 (3.9) | 17/164 (10.4) | 0.001‡ | |

| Chronic kidney disease requiring RRT | 16/1,022 (1.6) | 9/814 (1.1) | 7/164 (4.3) | 0.010‡ | |

| Hematologic cancer | 40/1,022 (3.9) | 27/814 (3.3) | 11/164 (6.7) | 0.068‡ | |

| Metastatic cancer | 24/1,022 (2.3) | 15/814 (1.8) | 7/164 (4.3) | 0.105‡ | |

| Days from hospital to ICU admission | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-1) | 0.096† | |

| Support at ICU admission | |||||

| Noninvasive ventilation | 267/1,296 (20.6) | 218/1,078 (20.2) | 34/170 (20.0) | 1.000‡ | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 111/1,296 (8.6) | 82/1,078 (7.6) | 20/170 (11.8) | 0.091‡ | |

| Vasopressors | 83/1,296 (6.4) | 53/1,078 (4.9) | 20/170 (11.8) | <0.001‡ | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 4/1,296 (0.3) | 1/1,078 (0.1) | 2/170 (1.2) | 0.050‡ | |

Results expressed as median (interquartile range) or n/n total (%).

By the time data was extracted (March, 9, 2021), 48 patients were still hospitalized; p-values were calculated using

Mann-Whitney U test

χ2 test.

SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; MFI: modified frailty index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RRT: renal replacement therapy; ICU: intensive care unit.

The median (IQR) age of pooled patients was 66 (53 to 77) years, 66.5% were male, and the median (IQR) SAPS 3 was 49 (42 to 56) points. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (59.4%), diabetes mellitus (35.8%), and obesity (30.7%). At ICU admission, 20.6% of patients were receiving noninvasive ventilation, 8.6% were under mechanical ventilation, and 6.4% were using vasopressors.

Compared to survivors, non-survivors were older [80 (70-88) versus 63 (50-74) years; p<0.001], had a higher SAPS 3 [59 (54-66) versus 47 (42-53) points; p<0.001] and a higher SOFA [6 (4-9) versus 1 (0-3) points; p<0.001] at ICU admission. Cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease requiring and not requiring RRT were more frequent in non-survivors compared to survivors.

Resource use

During the ICU stay, 56.6% of patients received noninvasive ventilation, 32.9% of patients were mechanically ventilated; 31.3% used HFNC, 11.7% received RRT, and 1.5% received ECMO support. The median (IQR) duration of mechanical ventilation in pooled patients was 11 (6 to 24) days (Table 2).

Table 2. Resource use.

| Resource | All patients 1,296 (100%)* |

Survivors 1,078/1,248 (86.4%) |

Non-survivors 170/1,248 (13.6%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support during ICU stay | |||||

| Noninvasive ventilation | 733/1,296 (56.6) | 602/1,078 (55.8) | 104/170 (61.2) | 0.222† | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 426/1,296 (32.9) | 257/1,078 (23.8) | 133/170 (78.2) | <0.001† | |

| Vasopressors | 418/1,296 (32.3) | 254/1,078 (23.6) | 128/170 (75.3) | <0.001† | |

| High flow nasal cannula | 406/1,296 (31.3) | 308/1,078 (28.6) | 72/170 (42.4) | <0.001† | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 151/1,296 (11.7) | 59/1,078 (5.5) | 76/170 (44.7) | <0.001† | |

| ECMO | 20/1,296 (1.5) | 6/1,078 (0.6) | 11/170 (6.5) | <0.001‡ | |

| Tracheostomy | 84/1,296 (6.5) | 45/1,078 (4.2) | 29/170 (17.1) | <0.001† | |

| MV duration (days) | 11 (6-24) | 9 (5-15) | 17 (10-38) | <0.001§ | |

Results expressed as median (interquartile range) or n/n total (%).

By the time data was extracted (March 9, 2021), 48 patients were still hospitalized; p-values were calculated using

χ2 test

Fisher exact test or

Mann-Whitney U test.

ICU: intensive care unit; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MV: mechanical ventilation.

Mechanical ventilation, HFNC, vasopressors, RRT, and ECMO were more frequently used in non-survivors compared to survivors. The median (IQR) days on mechanical ventilation was higher in non-survivors compared to survivors [17 (10-38) versus 9 (5-15) days; p<0.001].

Clinical outcomes

Pooled patients

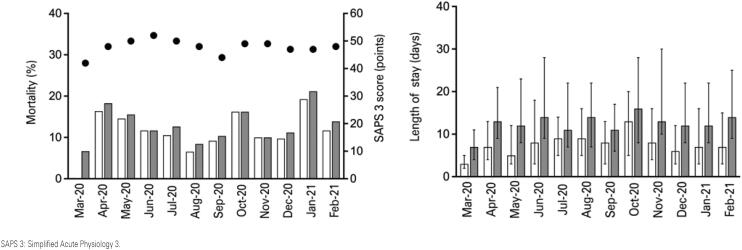

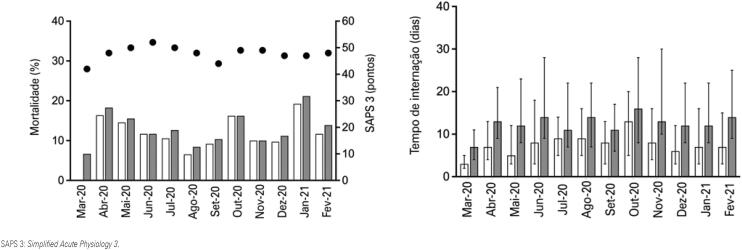

Intensive care unit and in-hospital mortality of pooled patients was, respectively, 11.7% (151 of 1,296 patients) and 13.6% (170 of 1,248 patients) (Table 3). Monthly ICU and in-hospital mortality between March 2020 and February 2021 is shown in figure 1. Cumulative survival at day 28 of pooled patients and survival stratified according to the use of mechanical ventilation, RRT, and ECMO are shown in figure 2.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes.

| Outcomes | All patients 1,296 (100%)* |

Survivors 1,078/1,248 (86.4%) |

Non-survivors 170/1,248 (13.6%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination at hospital discharge | <0.001† | ||||

| Home | 1,050/1,296 (84.1) | 1,050/1,078 (97.4) | 0/170 (0.0) | ||

| Home care | 18/1,296 (1.4) | 18/1,078 (1.7) | 0/170 (0.0) | ||

| Transfer to another hospital | 10/1,296 (0.8) | 10/1,078 (0.9) | 0/170 (0.0) | ||

| Palliative care | 47/1,296 (3.6) | 3/1,078 (0.3) | 44/170 (25.9) | <0.001† | |

| ICU length of stay, days | 7 (4-16) | 7 (3-13) | 15 (9-29) | <0.001‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 13 (8-23) | 12 (8-21) | 19 (12-34) | <0.001‡ | |

| According to the use of MV* | |||||

| Patients who received MV | 426 (100.0) | 257/390 (65.9) | 133/390 (34.1)§ | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 20 (13-32)§ | 19 (13-30)§ | 19 (12-33)§ | 0.892‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 27 (17-41)§ | 28 (18-41)§ | 24 (14-41)§ | 0.021‡ | |

| Patients who did not receive MV | 870 (100.0) | 821/858 (95.7) | 37/858 (4.3) | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 5 (2-8) | 5 (2-8) | 7 (3-11) | 0.058‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 10 (7-15) | 10 (7-15) | 10.0 (6-15) | 0.850‡ | |

| According to the use of RRT* | |||||

| Patients who received RRT | 151 (100.0) | 59/135 (43.7) | 76/135 (56.3)¶ | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 27 (15-40)¶ | 25 (17-37)¶ | 26 (13-40)¶ | 0.688‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 33 (22-55)¶ | 35 (28-61)¶ | 30 (16-49)¶ | 0.024‡ | |

| Patients who did not receive RRT | 1,145 (100.0) | 1,019/1,113 (91.6) | 94/1,113 (8.4) | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 7 (3-13) | 6 (3-11) | 13 (6-17) | <0.001‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 12 (8-19) | 11 (8-19) | 15 (9-24) | 0.009‡ | |

| According to the use of ECMO* | |||||

| Patients who received ECMO | 20 (100.0) | 6/17 (35.3) | 11/17 (64.7)& | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 32 (24-59)& | 37 (23-76)& | 29 (10-55)# | 0.687‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 48 (29-70)& | 49 (33-98)& | 31 (12-70) | 0.365‡ | |

| Patients who did not receive ECMO | 1,276 (100.0) | 1,072/1,231 (87.1) | 159/1,231 (12.9) | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 7 (3-15) | 7 (3-13) | 15 (9-28) | <0.001‡ | |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 12 (8-23) | 12 (8-21) | 18 (12-34) | <0.001‡ | |

Results expressed as n/n total (%) or median (interquartile range).

By the time data was extracted (March 9, 2021), 48 patients were still hospitalized. Out of those, 36 patients were receiving MV, 16 were receiving RRT, and 3 were receiving ECMO; p-values were calculated using

χ2 test

Mann-Whitney U test

p<0.001 versus patients who did not receive MV

p<0.001 versus patients who did not receive RRT

p<0.001 versus patients who did not receive ECMO

p=0.039 versus patients who did not receive ECMO.

ICU: intensive care unit; MV: mechanical ventilation; RRT: renal replacement therapy; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Figure 1. Monthly length of intensive care unit and hospital stay, intensive care unit and in-hospital mortality, and simplified acute physiology score 3 from March 2020 to February 2021.

Figure 2. Cumulative survival at day 28 of pooled patients and according to the need for organ support.

The median IQR length of ICU and hospital stay was, respectively, 7 (4 to 16) days and 13 (8 to 23) days. Compared to survivors, non-survivors exhibited a higher length of ICU [15 (9-29) versus 7 (3-13) days; p<0.001] and hospital stay [19 (12-34) versus 12 (8-21) days; p<0.001] (Table 3).

Mechanically ventilated patients

Mechanically ventilated patients exhibited a higher in-hospital mortality compared to patients who did not receive mechanical ventilation (34.1% versus 4.3%; unadjusted OR: 11.5; 95%CI: 7.8-17.0; p<0.001). The length of ICU [20 (13-32) versus 5 (2-8) days; p<0.001] and hospital stay [27 (17-41) versus 10 (7-15) days; p<0.001] was higher in patients who received mechanical ventilation compared to non-mechanically ventilated patients.

Patients who received renal replacement therapy

Patients submitted to RRT showed a higher in-hospital mortality compared to patients who did not receive RRT (56.3% versus 8.4%; unadjusted OR: 14.0; 95%CI: 9.4-20.8; p<0.001). Mechanical ventilation was used in 143 of 151 (94.7%) patients who received RRT. The length of ICU [27 (15-40) versus 7 (3-13) days; p<0.001] and hospital stay [33 (22-55) versus 12 (8-19) days; p<0.001] was higher in patients who received RRT than in patients who did not receive RRT.

Patients who received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Patients who received ECMO exhibited a higher in-hospital mortality compared to patients who did not receive ECMO [64.7% versus 12.9%; unadjusted OR: 12.4; 95%CI: 4.5-33.9; p<0.001) (Table 3). All patients who received ECMO support received mechanical ventilation, and 13 out of 20 (65.0%) patients also used RRT. The length of ICU [32 (24-59) versus 7 (3-15) days; p<0.001] and hospital stay [48 (29-70) versus 12 (8-23) days; p<0.001] was higher in patients who received ECMO than in patients who did not receive ECMO support.

Predictors of in-hospital mortality

Univariable analysis of factors associated with in-hospital death is depicted in table 4. After adjusting for confounders, independent predictors of in-hospital mortality included age (OR: 1.08; 95%CI: 1.06-1.10; p<0.001); SOFA (OR: 1.18; 95%CI: 1.08-1.29; p<0.001); Charlson Comorbidity Index (OR: 1.28; 95%CI: 1.15-1.43; p<0.001); the need for mechanical ventilation (OR: 4.45; 95%CI: 2.43-8.16; p<0.001); the need for HFNC (OR: 1.64; 95%CI: 1.04-2.58; p=0.033); RRT (OR: 3.42; 95%CI: 1.96-5.98; p<0.001) and ECMO support (OR: 8.18; 95%CI: 2.48-27.05; p<0.001) (Table 4). The final multivariable model had an area under the ROC curve (95%CI) of 0.93 (0.91-0.94) and a Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 of 8.844 (p=0.356).

Table 4. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses addressing risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

| Predictors | Type of analysis Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p value | OR | 95%CI | p value | ||

| Age, years | 1.07 | 1.06-1.08 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.06-1.10 | <0.001 | |

| SAPS 3* | |||||||

| ≤42 | Reference | ||||||

| 43-49 | 2.93 | 1.04-8.23 | 0.041 | ||||

| 50-55 | 9.77 | 3.75-25.46 | <0.001 | ||||

| ≥56 | 41.80 | 16.79-104.07 | <0.001 | ||||

| SOFA | 1.46 | 1.38-1.54 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.08-1.29 | <0.001 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.39 | 1.29-1.51 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 1.15-1.43 | <0.001 | |

| MFI | 1.72 | 1.53-1.95 | <0.001 | ||||

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Cancer | 2.03 | 1.19-3.46 | 0.009 | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 3.00 | 1.79-5.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| COPD | 1.70 | 0.95-3.01 | 0.072 | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.83 | 1.53-5.22 | <0.001 | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease requiring RRT | 3.99 | 1.46-10.87 | 0.007 | ||||

| Hematologic cancer | 2.10 | 1.02-4.31 | 0.045 | ||||

| Metastatic cancer | 2.38 | 0.95-5.92 | 0.063 | ||||

| Days from hospital to ICU admission | 1.00 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.534 | ||||

| AKI at ICU admission | 3.41 | 1.86-6.26 | <0.001 | ||||

| Support during ICU stay | |||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 11.48 | 7.77-16.97 | <0.001 | 4.45 | 2.43-8.16 | <0.001 | |

| Vasopressors | 9.89 | 6.79-14.40 | <0.001 | ||||

| High flow nasal cannula | 1.84 | 1.32-2.56 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 1.04-2.58 | 0.033 | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 11.96 | 9.36-20.84 | <0.001 | 3.42 | 1.96-5.98 | <0.001 | |

| ECMO | 12.36 | 4.51-33.89 | <0.001 | 8.18 | 2.48-27.05 | <0.001 | |

SAPS 3 was categorized according to percentiles, since linearity assumption was violated. The multivariable model had an area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (95%CI) of 0.93 (0.91-0.94) and a Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 of 8.844 (p=0.356).

OR: odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3; SOFA score: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; MFI: modified frailty index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RRT: renal replacement therapy; ICU: intensive care unit; AKI: acute kidney injury according; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective single center cohort study, we found that one in seven patients admitted to the ICU due to severe COVID-19 infection died at the hospital. Non-survivors were older, sicker, in accordance with SAPS 3 and SOFA, presented more comorbidities, such as cancer, congestive heart failure or chronic kidney disease, and had a longer ICU and hospital length of stay compared to survivors. Finally, increased age, higher SOFA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index, need for mechanical ventilation, HFNC, RRT, and ECMO were independent predictors of in-hospital mortality.

The association between advanced age and increased risk of death in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 has been reported by different authors.(3,26-28) Moreover, the association between the presence of comorbidities and the severity of COVID-19 was evidenced in several studies.(9,26,29,30) For instance, COVID-19 patients with hypertension, cardiocerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus were at higher risk of developing severe symptoms, and requiring ICU admission than patients without these comorbidities.(30) Furthermore, we observed that locoregional cancer diagnosis was more prevalent in deceased patients in comparison with survivors. Indeed, it was demonstrated in a large case-control study that cancer patients with COVID-19 exhibited an increased risk of worse clinical outcomes.(31) Although increased mortality has also been reported in patients with hematological cancer,(32) we did not observe this association in our study.

Interestingly, in our cohort we found lower in-hospital mortality both among patients admitted to the ICU and those requiring mechanical ventilation support, compared to previous studies conducted in Brazil(14) and in other countries.(6,33,34) In a cohort study involving 254,288 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Brazil, Ranzani et al., demonstrated a hospital mortality rate of approximately 60% among patients admitted to the ICU and a rate of roughly 80% among patients who received mechanical ventilation.(14) In a meta-analysis comprising 28 studies and 12,437 patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 worldwide, the reported ICU and mechanically ventilated mortality were, respectively, 28.3% and 43%.(4)

The discrepancy between the observed mortality rate in the present study and in other series may be explained by different hospital characteristics (private versus public); adopted thresholds for hospitalization and/or ICU admission; availability of resources, such as ICU beds, and limited offer of advanced respiratory support outside an ICU, or in ICUs but with resource constraints, characteristics of the ICU staff; ventilation strategies, such as the use of noninvasive ventilation and HFNC, and strategies for extra-pulmonary organ support. Furthermore, despite the different moments of COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, the observed monthly stability on outcomes (length of stay and mortality) of COVID-19 patients reflects the hospital and ICU organization to provide the best quality of care to patients.

Patients with acute kidney injury requiring RRT had a 14-fold increase in the odds for in-hospital death, compared with COVID-19 patients who did not receive RRT. This observation is consistent with other studies, in which a significant association between acute kidney injury and increased risk of death was reported in patients with severe COVID-19.(4,35,36) Additionally, we found that almost half of the deceased patients underwent RRT, which is also similar to other studies.(34,37,38) The assessment of risk factors for the development of acute kidney injury, and use of RRT in the first 207 critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to our ICU, were reported elsewhere.(39)

The highest in-hospital mortality rate in our study was observed in the subgroup of patients who received ECMO (approximately 65%). Reported mortality for COVID-19 patients submitted to veno-venous ECMO varied widely.(40) For instance, the reported in-hospital death at 90 days after ECMO initiation in 1,035 patients from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry was 37%.(41) Nevertheless, approximately one third of patients included in this study were still hospitalized, or had been discharged to another hospital or to a long-term acute care center at the time of outcome measurement.(41) Therefore, the crude mortality for COVID-19 patients who receive ECMO may be underestimated.

Our study has limitations. First, it was performed in a single ICU located in a private quaternary care hospital in Brazil. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to other ICUs in Brazil or in other developing countries, since healthcare systems and patient characteristics may vary substantially from our cohort. Second, we did not collect detailed data on noninvasive or on ventilator management strategies. It is well established that ventilatory support for ARF patients has a major impact on outcomes.(42,43) Third, we assumed that patients discharged from hospital before 28 days were still alive at day 28. Nevertheless, discharged patients might have been readmitted elsewhere or could have died after discharge. Finally, we did not assess whether the new SARS-CoV-2 variants affected outcomes in our cohort of patients compared to previously circulating variants in Brazil.(44,45)

CONCLUSION

Patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit had considerable morbidity and mortality, requiring substantial organ support, and a prolonged intensive care unit and hospital stay. The volume and severity of COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care unit admission are a great burden for the Brazilian health care system. Therefore, the results of this study may be of interest to be used as benchmark, or to support decisions concerning delivery of healthcare services and prognosis for COVID-19 patients demanding intensive care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the intensive care unit physicians, nursing staff, physical therapists, and all members of the multidisciplinary team of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, who managed patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The authors thank Helena Spalic for proofreading this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Jan 30;: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Teich VD, Klajner S, Almeida FA, Dantas AC, Laselva CR, Torritesi MG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of patients with COVID-19 in Brazil. einstein (São Paulo). 2020;18:eAO6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O’Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Chang R, Elhusseiny KM, Yeh YC, Sun WZ. COVID-19 ICU and mechanical ventilation patient characteristics and outcomes-a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, Iotti G, Latronico N, Lorini L, Merler S, Natalini G, Piatti A, Ranieri MV, Scandroglio AM, Storti E, Cecconi M, Pesenti A; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-81. Erratum in: JAMA. 2021;325(20):2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Jain V, Yuan JM. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(5):533-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934-43. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tan E, Song J, Deane AM, Plummer MP. Global impact of coronavirus disease 2019 infection requiring admission to the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2021;159(2):524-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. COVID-19. Painel Coronavírus. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2021 [citado 2021 Jun 27]. Disponível em: https://covid.saude.gov.br/

- 11.Santos MM, Lucena EE, Lima KC, Brito AA, Bay MB, Bonfada D. Survival and predictors of deaths of patients hospitalised due to COVID-19 from a retrospective and multicentre cohort study in Brazil. Epidemiol Infect. 2020; 148:e198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Socolovithc RL, Fumis RR, Tomazini BM, Pastore L, Galas FR, de Azevedo LC, et al. Epidemiology, outcomes, and the use of intensive care unit resources of critically ill patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Sao Paulo, Brazil: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Sousa GJ, Garces TS, Cestari VR, Florêncio RS, Moreira TM, Pereira ML. Mortality and survival of COVID-19. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ranzani OT, Bastos LS, Gelli JG, Marchesi JF, Baiao F, Hamacher S, et al. Characterisation of the first 250 000 hospital admissions for COVID-19 in Brazil: a retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:407-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; Iniciativa STROBE. [The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2008;82(3):251-9. Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DK, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. Erratum in: Euro Surveill. 2020;25(14): Erratum in: Euro Surveill. 2020;25(30): Erratum in: Euro Surveill. 2021;26(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Corrêa TD, Matos GF, Bravim BA, Cordioli RL, Garrido AG, Assuncao MS, et al. Intensive support recommendations for critically-ill patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. einstein (São Paulo). 2020;18:eAE5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Corrêa TD, Matos GF, Bravim BA, Cordioli RL, Garrido AG, Assuncao MS, et al. Comment to:Intensive support recommendations for critically-ill patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. einstein (São Paulo). 2020; 18:eCE5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Soares M, Bozza FA, Angus DC, Japiassú AM, Viana WN, Costa R, et al. Organizational characteristics, outcomes, and resource use in 78 Brazilian intensive care units: the ORCHESTRA study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(12):2149-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Moreno RP, Metnitz PG, Almeida E, Jordan B, Bauer P, Campos RA, Iapichino G, Edbrooke D, Capuzzo M, Le Gall JR; SAPS 3 Investigators. SAPS 3-From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: Development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(10):1345-55. Erratum in: Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(5):796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):104-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Nova Jersey: Wiley & Sons; 2013. p. 203-22.

- 25.Ottenbacher KJ, Ottenbacher HR, Tooth L, Ostir GV. A review of two journals found that articles using multivariable logistic regression frequently did not report commonly recommended assumptions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(11):1147-52. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. Erratum for: BMJ. 2020;368:m1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, Brenner SK, Leonberg-Yoo A, Schenck EJ, Radbel J, Reiser J, Bansal A, Srivastava A, Zhou Y, Sutherland A, Green A, Shehata AM, Goyal N, Vijayan A, Velez JC, Shaefi S, Parikh CR, Arunthamakun J, Athavale AM, Friedman AN, Short SA, Kibbelaar ZA, Abu Omar S, Admon AJ, Donnelly JP, Gershengorn HB, Hernán MA, Semler MW, Leaf DE; STOP-COVID Investigators. Factors associated with death in critically Ill patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1436-47. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Wang B, Li R, Lu Z, Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020; 12(7):6049-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531-8. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Passamonti F, Cattaneo C, Arcaini L, Bruna R, Cavo M, Merli F, Angelucci E, Krampera M, Cairoli R, Della Porta MG, Fracchiolla N, Ladetto M, Gambacorti Passerini C, Salvini M, Marchetti M, Lemoli R, Molteni A, Busca A, Cuneo A, Romano A, Giuliani N, Galimberti S, Corso A, Morotti A, Falini B, Billio A, Gherlinzoni F, Visani G, Tisi MC, Tafuri A, Tosi P, Lanza F, Massaia M, Turrini M, Ferrara F, Gurrieri C, Vallisa D, Martelli M, Derenzini E, Guarini A, Conconi A, Cuccaro A, Cudillo L, Russo D, Ciambelli F, Scattolin AM, Luppi M, Selleri C, Ortu La Barbera E, Ferrandina C, Di Renzo N, Olivieri A, Bocchia M, Gentile M, Marchesi F, Musto P, Federici AB, Candoni A, Venditti A, Fava C, Pinto A, Galieni P, Rigacci L, Armiento D, Pane F, Oberti M, Zappasodi P, Visco C, Franchi M, Grossi PA, Bertù L, Corrao G, Pagano L, Corradini P; ITA-HEMA-COV Investigators. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(10):e737-e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wang Y, Lu X, Li Y, Chen H, Chen T, Su N, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW: the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-9. Erratum in: JAMA. 2020;323(20):2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hansrivijit P, Qian C, Boonpheng B, Thongprayoon C, Vallabhajosyula S, Cheungpasitporn W, et al. Incidence of acute kidney injury and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2020;68(7):1261-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Lowe R, Ferrari M, Nasim-Mohi M, Jackson A, Beecham R, Veighey K, Cusack R, Richardson D, Grocott M, Levett D, Dushianthan A; University Hospital Southampton Critical Care Team and the REACT COVID investigators. Clinical characteristics and outcome of critically ill COVID-19 patients with acute kidney injury: a single centre cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475-81. Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Doher MP, Torres de Carvalho FR, Scherer PF, Matsui TN, Ammirati AL, Caldin da Silva B, et al. Acute kidney injury and renal replacement therapy in critically Ill COVID-19 patients: risk factors and outcomes: a single-center experience in Brazil. Blood Purif. 2020:50(4-5):520-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Huang S, Zhao S, Luo H, Wu Z, Wu J, Xia H, et al. The role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a narrative review. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):116. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, Bartlett RH, Tonna JE, Hyslop R, Fanning JJ, Rycus PT, Hyer S, Anders MM, Agerstrand CL, Hryniewicz K, Diaz R, Lorusso R, Combes A, Brodie D; Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1071-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, Mercier E, Badet M, Mercat A, Baudin O, Clavel M, Chatellier D, Jaber S, Rosselli S, Mancebo J, Sirodot M, Hilbert G, Bengler C, Richecoeur J, Gainnier M, Bayle F, Bourdin G, Leray V, Girard R, Baboi L, Ayzac L; PROSEVA Study Group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, Claro IM, Candido DS, Mishra S, et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. 2021;372(6544):815-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Resende PC, Gräf T, Paixão AC, Appolinario L, Lopes RS, Mendonça AC, et al. A Potential SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Interest (VOI) Harboring Mutation E484K in the Spike Protein Was Identified within Lineage B.1.1.33 Circulating in Brazil. Viruses. 2021;13(5):724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]