Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a pulmonary disease (COVID-19) which spread worldwide generating fear, anxiety, depression in the general population as well as among subjects affected by mental disorders. Little is known about which different psychopathological changes the pandemic caused among individuals affected by different psychiatric disorders, which represents the aim of the present study. Specific psychometric scales were administered at three time points: T0 as outbreak of pandemic, T1 as lockdown period, T2 as reopening. Descriptive analyses and linear regression models were performed. A total of 166 outpatients were included. Overall, psychometric scores showed a significant worsening at T1 with a mild improvement at T2. Only psychopathology in schizophrenia (SKZ) patients and obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms did not significantly improve at T2. Subjects affected by personality disorders (PDs) resulted to be more compromised in terms of general psychopathology than depressed and anxiety/OC ones, and showed more severe anxiety symptoms than SKZ patients. In conclusion, subjects affected by PDs require specific clinical attention during COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the worsening of SKZ and OC symptoms should be strictly monitored by clinicians, as these aspects did not improve with the end of lockdown measures. Further studies on larger samples are needed to confirm our results. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04694482

Keywords: COVID-19, Obsessive-compulsive symptoms, Outpatients, Pandemic, Personality disorders, Psychotic symptoms

1. Introduction

By the end of 2019, a new Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which was firstly identified in Wuhan, China, spread worldwide, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a pandemic on March 11th 2020 (WHO, 2020). Since the first months, Italy, and in particular Lombardy region in the north of the country, was particularly affected by the infection. The Italian government first declared a state of emergency on January 31st 2020 (Consiglio dei Ministri, 2020), then imposed largely restrictive measures that began in March and lasted about two months (the so-called “Phase-I”).

In different affected countries, the spread of the virus and the mass quarantine caused not only physical, but also psychological effects, such as fear of contagion, anxiety, insomnia, depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), similarly to what was observed in previous epidemics (Brooks et al., 2020). Indeed, several studies investigated the psychopathological consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in the general population. For example, high percentage of PTSD symptoms (29.5%) as well as of depression, anxiety and insomnia was reported in the Italian population (Forte et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020) and other countries (Daly and Robinson, 2021).

Of note, the health emergency conditioned many aspects of psychiatric intervention and care (De Girolamo et al., 2020). In particular, outpatient visits were limited to emergencies, critical or non-postponable cases (i.e. long-acting treatment, discharge from SPDC) and converted into telephone interviews or video calls. Group activities and team meetings were suspended and re-scheduled. Semi-residential structures (Day Centers) were open only for patients with an imperative need for daytime support. Hospitalizations and other inpatient facilities were severely limited to strictly urgent cases. Of course, psychiatric patients, who benefit from the relationship with the health personnel (Caldiroli et al., 2020) and from extensive rehabilitation and re-socialization interventions, may have been particularly affected by these restricted measures (Barlati et al., 2021).

Several authors assessed the psychopathological impact of the pandemic among psychiatric patients, but only few of them compared different diagnostic groups. A study conducted in Italy and Paraguay found a worsening of clinical symptoms, anxiety, fear and psychological distress among psychiatric outpatients, without distinguishing between different diagnoses (Gentile et al., 2020). Available data indicate that pandemic had a particularly negative impact on subjects affected by Personality disorders (PDs) (Preti et al., 2020), while Pinkhamet al. (2020) reported surprisingly that patients affected by schizophrenia (SKZ) or bipolar disorder (BD) did not present a worsening of symptoms between April and June 2020. Similar results were found in a sample of 65 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (Littman et al., 2020). In the light of these considerations, it seems plausible that patients might have reacted differently to COVID-19 pandemic according to their main psychiatric diagnosis, but data are still few and controversial.

Purpose of the present study was to compare the change in severity of symptoms in different diagnostic group during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This is an observational retrospective study. Outpatients (aged 18–65) were consecutively recruited at three mental health services of ASST Monza (Cesano Maderno, Monza and Brugherio) from November 12th 2020 until January 31st 2021. Information about the psychopathological status of patients, routinely evaluated during psychiatric visits, were retrospectively collected. In particular, data collected for the purposes of the study were registered when psychiatric visits occurred in January or February 2020 for T0, corresponding to the outbreak of the pandemic; in March or April 2020 for T1, that was the lockdown period (the so-called “phase I”); in May or June 2020 for T2, corresponding to the reopening and restarting (the so-called “phase II”). The same sample was evaluated at three time-points with a full retention rate.

Inclusion criteria consisted of: (1) comprehension of the Italian language; (2) ability to understand and sign the written informed consent; (3) diagnosis of SKZ, BD, major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, OCD or PDs according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th edition (DSM 5 – APA, 2013) criteria; (4) availability of the complete panel of psychometric scores in the medical records. Exclusion criteria were: (1) severe intellectual disability; (2) pregnancy or post-partum; (3) presence of medical conditions potentially contributing to psychiatric symptoms (e.g. multiple sclerosis or re-exacerbation of inflammatory diseases); (4) treatment with compounds potentially involved in the onset or worsening of psychiatric symptoms (e.g. corticosteroids); (5) health personnel involved in the sanitary emergency.

All participants signed informed consent after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the local accredited Medical Ethics Review Committee (named “Brianza Ethic Committee”; resolution number 1650, dated 12th November 2020). The research project is conformed to the provisions of the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the following ID number: NCT04694482

2.2. Assessment

Data were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records or, in case they were lacking, by interviews to the patients or their relatives and caregivers. Demographic variables included: age, gender, marital status, occupational status and education. Clinical variables included: diagnosis, age at onset, duration of illness, duration of untreated illness – DUI, level of needed care, type of psychiatric comorbidity, the presence of multiple psychiatric comorbidity (yes/no), the presence of family history of psychiatric disorders, suicide attempts, presence and number of hospitalizations, main pharmacological treatment, the presence of poly-therapy (yes/no), post-COVID changes in psychopharmacological treatment (no/increased/decreased in terms of dosages and/or number of prescribed compounds), presence of ongoing psychotherapy (yes/no). DUI was defined as the time elapsing between the onset of psychiatric disorders and the prescription of a proper pharmacological treatment according to international guidelines (Buoli et al., 2021). Level of needed care was considered “high” when the patient required a team of personnel for care, “low” when the patient was followed only by the psychiatrist. Data about substance misuse were registered referring at the 6 months before and 6 months after pandemic. The rating scales are routinely administered during patients’ visits.

2.2.1. Primary outcomes

-

-

Brief Psychiatry Rating Scale (BPRS – Overall and Gorham, 1962) at T0, T1, T2;

-

-

Clinical Global Impression (CGI – Guy, 1976) severity subscale at T0, T1, T2; improvement subscale at T1 and T2;

-

-

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A – Hamilton, 1959) at T0, T1, T2.

-

-

These rating scales were administered to all patients.

2.2.2. Secondary outcomes

-

-

- Disability Scale (DISS – Sheehan et al., 1996) at T0, T1, T2;

-

-

- Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS – Kay et al., 1987), collected for SKZ patients at T0, T1, T2;

-

-

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D – Hamilton, 1960) and Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS - Montgomery and Åsberg, 1979), collected for MDD and BD patients at T0, T1, T2;

-

-

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS – Young et al., 1978), collected for BD patients at T0, T1, T2;

-

-

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS – Goodman et al., 1989a, 1989b), collected for OCD patients at T0, T1, T2.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses of the entire sample were performed. Patients were divided into 5 groups according to diagnosis (SKZ, BD, MDD, anxiety disorders or OCD, PDs); multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) and chi-square tests were used to compare groups on quantitative and qualitative variables respectively.

Linear regression models (Gueorguieva and Krystal, 2004) were applied to examine whether the change over time in psychometric scores differed between diagnostic groups. In the models, psychometric scores were treated as dependent variables. The model included fixed effects of time and diagnosis. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to select the appropriate statistical model. The unstructured variance–covariance matrix was used to account for repeated measures within each subject. The significance was set at p < 0.05.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows (version 26.0) was used as statistical program.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses and diagnostic group comparisons

The sample of patients (N = 166) included 87 males and 79 females. Among the total patients, 66 (39.8%) were affected by SKZ, 29 (17.5%) by BD, 36 (21.7%) by MDD, 17 (10.2%) by anxiety or OCD, and 18 (10.8%) by PDs. Mean age was 49.22 years (±14.23).

Demographic and clinical data of the sample are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Descriptive analyses of the total sample and summary of the results of the univariate analyses comparing the diagnostic groups (SKZ, BD, MDD, anxiety/OCD, PDs) according to demographic and clinical variables.

| VARIABLES | N = 166 | F or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49.22 (±14.23) | 3.22 | 0.01 | |

| Sex | Male | 87 (52.4%) | 4.47 | 0.35 |

| Female | 79 (47.6%) | |||

| Level of needed care | High | 61 (36.7%) | 30.68 | <0.01 |

| Low | 105 (63.3%) | |||

| Education | Primary School | 11 (6.6%) | 11.43 | 0.50 |

| Secondary school | 69 (41.6%) | |||

| High school | 77 (46.4%) | |||

| Graduate | 9 (5.4%) | |||

| Occupational status | Employed | 45 (27.1%) | 3.78 | 0.45 |

| Not employed | 121 (72.9%) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 92 (55.4%) | 24.29 | 0.02 |

| Married/cohabitant | 46 (27.7%) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 23 (13.9%) | |||

| Widower | 5 (3.0%) | |||

| Psychiatric comorbidity | None | 119 (71.8%) | 31.57 | 0.28 |

| SKZ | 20 (12.0%) | |||

| MDD | 6 (3.6%) | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 4 (2.4%) | |||

| PD | 12 (7.2%) | |||

| OCD | 2 (1.2%) | |||

| Mild intellectual disability | 2 (1.2%) | |||

| Eating disorders | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| Psychiatric polycomorbidity | Yes | 5 (3.0%) | 2.59 | 0.63 |

| No | 161 (97.0%) | |||

| Family history of psychiatric disorders | None | 81 (48.9%) | 101.29 | <0.01 |

| SKZ | 19 (11.4%) | |||

| BD | 6 (3.6%) | |||

| MDDs | 33 (19.9%) | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 13 (7.8%) | |||

| Eating disorders | 2 (1.2%) | |||

| Substance misuse | 6 (3.6%) | |||

| PD | 6 (3.6%) | |||

| Family history of more than one psychiatric disorders | Yes | 32 (19.3%) | 13.03 | 0.01 |

| No | 134 (80.7%) | |||

| Age at onset (years) | 28.28 (±12.33) | 8.66 | <0.01 | |

| Duration of illness (years) | 21.04 (±12.66) | 1.14 | 0.34 | |

| DUI (years) | 3.61 (±7.05) | 10.44 | <0.01 | |

| Lifetime substance misuse | None | 119 (71.8%) | 39.51 | 0.02 |

| Alcohol | 15 (9.0%) | |||

| Cannabis | 17 (10.2%) | |||

| Cocaine | 8 (4.8%) | |||

| Heroin | 4 (2.4%) | |||

| BDZ | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| Gambling | 2 (1.2%) | |||

| 6-months pre-COVID substance misuse | None | 146 (88.0%) | 41.94 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol | 10 (6.0%) | |||

| Cannabis | 5 (3.0%) | |||

| Cocaine | 3 (1.8%) | |||

| BDZ | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| Gambling | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| 6-months post-COVID substance misuse | None | 150 (90.4%) | 23.13 | 0.10 |

| Alcohol | 8 (4.8%) | |||

| Cannabis | 4 (2.4%) | |||

| Cocaine | 3 (1.8%) | |||

| BDZ | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| Lifetime hospitalizations | Yes | 115 (69.3%) | 19.58 | <0.01 |

| No | 51 (30.7%) | |||

| Number of previous hospitalizations | 2.12 (±3.04) | 2.99 | 0.02 | |

| Lifetime suicide attempts | Yes | 25 (15.1%) | 9.91 | 0.04 |

| No | 141 (84.9%) | |||

| Main treatment | None | 2 (1.2%) | 206.82 | <0.01 |

| Antipsychotic | 56 (33.8%) | |||

| Long-acting injection | 19 (11.4%) | |||

| Antidepressant | 62 (37.3%) | |||

| Stabilizer | 27 (16.3%) | |||

| Polytherapy | Yes | 111 (66.9%) | 9.39 | 0.05 |

| No | 55 (33.1%) | |||

| Post-COVID treatment changes | No | 107 (64.5%) | 18.44 | 0.02 |

| Increased | 54 (32.5%) | |||

| Decreased | 5 (3.0%) | |||

| Ongoing psychotherapy | Yes | 38 (22.9%) | 10.73 | 0.03 |

| No | 128 (77.1%) | |||

In bold statistically significant p. In bracket percentages for qualitative variables and standard deviations for quantitative ones are reported.

Legend: BD = Bipolar Disorder; BDZ = benzodiazepines; DUI = duration of untreated illness; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; PD = Personality Disorder; SKZ = Schizophrenia.

MDD patients were older than PD patients (p = 0.03) and had higher age at onset than those affected by PD/SKZ (both p values <0.001). PD patients had a lower age at onset with respect to those affected by BD (p = 0.003), and presented a longer DUI with respect to any other diagnostic group (p = 0.02 for anxiety/OCD; p < 0.001 for the other diagnostic groups). Moreover, while BD and MDD patients were more frequently engaged in relationships than the other groups (p < 0.05), SKZ ones resulted to be predominantly unmarried (p < 0.05).

SKZ and anxiety/OCD patients presented family history for psychiatric disorders less frequently than the other groups (p < 0.05). Patients affected by SKZ or PDs had more frequently only one relative affected by psychiatric disorders than the other groups (p < 0.05) and needed a higher level of care than MDD patients (p < 0.05). Moreover, patients affected by PDs were more prone to lifetime misuse of alcohol than the other groups (p < 0.05), while the anxiety/OCD diagnosis resulted to be the group with the least substance misuse in the six months before pandemic (p < 0.05). SKZ and BD patients had the highest number of lifetime hospitalizations, while anxiety/OCD group the lowest. BD patients presented lifetime suicide attempts more frequently than the other groups (p < 0.05). Subjects affected by SKZ and PDs were more frequently on polytherapy than the other groups and PDs patients more frequently reduced pharmacological treatments after the pandemic with respect to the other groups (p < 0.05). Finally, ongoing psychotherapy was more frequently reported by PD patients and less frequently by SKZ patients than the other groups (p < 0.05). The diagnostic groups were not significantly different for the other collected variables (Table 1).

3.2. Psychopathological changes over time

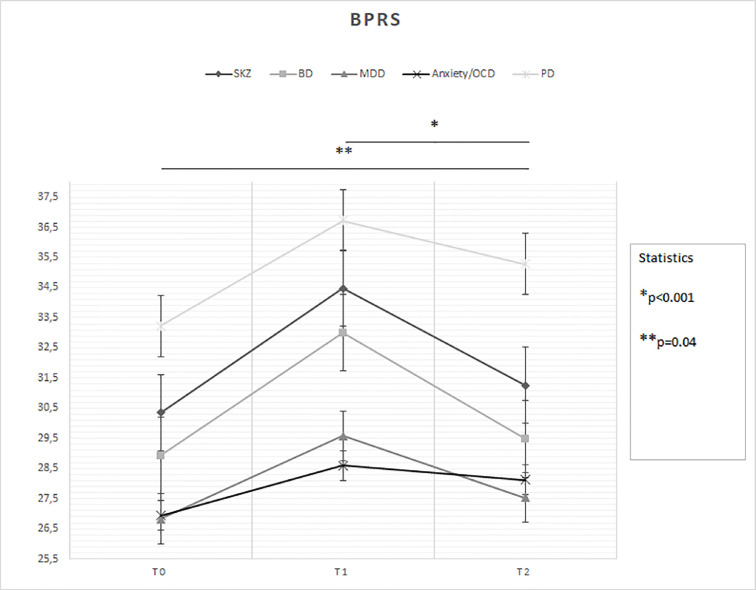

With regard to primary outcomes (Fig. 1 ):

-

-

Time (F = 26.56; p < 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of BPRS scores, but diagnosis did not at a borderline statistically significance (F = 2.30; p = 0.06) (Fig. 1): T0 < T2 (p = 0.04) and T1 > T2 (p < 0.001); MDD (p = 0.008) and anxiety disorders/OCD (p = 0.03) patients overall < PD patients;

-

-

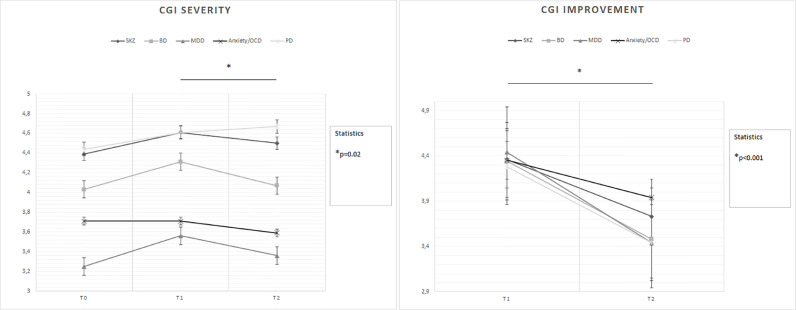

Time (F = 8.29; p < 0.001) and diagnosis (F = 6.65; p < 0.001) each had a significant effect on the change of CGI-severity scores (Fig. 2 ): T1 > T2 (p = 0.02); again, MDD (p = 0.001) and anxiety disorders/OCD (p = 0.02) patients overall < PD patients;

-

-

Time (F = 41.88; p < 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of CGI-improvement scores, but diagnosis did not (F = 0.90; p = 0.46) (Fig. 2): T1 > T2 (p < 0.001);

-

-

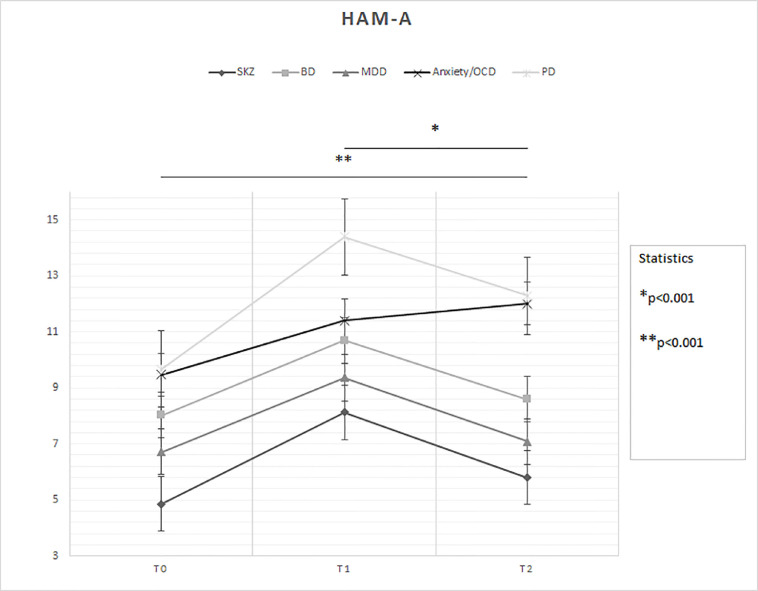

Time (F = 33.63; p < 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of HAM-A scores, while diagnosis showed a trend to present a significant effect (F = 2.36; p = 0.056) (Fig. 3 ): T0 < T2 and T1 > T2 (both p values <0.001); SKZ patients overall < PD patients (p = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Statistically significant changes in BPRS scores between groups over time

Legend: BD = Bipolar Disorder; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; PD = Personality Disorder; SKZ = Schizophrenia.

T0: outbreak of pandemic (January-February 2020)

T1: lockdown period (March-April 2020)

T2: reopening (May-June 2020)

* and ** = statistically significant differences.

Fig. 2.

Changes in CGI severity and improvement scores between groups over time

Legend: BD = Bipolar Disorder; CGI = Clinical Global Impression; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; PD = Personality Disorder; SKZ = Schizophrenia.

T0: outbreak of pandemic (January-February 2020)

T1: lockdown period (March-April 2020)

T2: reopening (May-June 2020)

* = statistically significant differences.

Fig. 3.

Changes in HAM-A scores between groups over time

Legend: BD = Bipolar Disorder; HAM-A = Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; PD = Personality Disorder; SKZ = Schizophrenia.

T0: outbreak of pandemic (January-February 2020)

T1: lockdown period (March-April 2020)

T2: reopening (May-June 2020)

* and ** = statistically significant differences.

With regard to secondary outcomes:

-

-

Diagnosis (F = 4.94; p = 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of DISS-disability scores, but time did not (F = 1.23; p = 0.29) (Supplementary Fig. 1): BD (p = 0.009), MDD (p < 0.001) and anxiety/OCD (p = 0.03) patients overall < PD patients;

-

-

Time (F = 40.80; p < 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of DISS-stress scores, but diagnosis did not at borderline statistically significance (F = 2.20; p = 0.07) (Supplementary Fig. 1): T0 < T2 and T1 > T2 (both p values <0.001); SKZ and BD patients overall < PD patients (both p values = 0.02);

-

-

Time (F = 9.26; p < 0.001) had a significant effect on the change of DISS-support scores, but diagnosis did not (F = 0.58; p = 0.68) (Supplementary Fig. 1): T0 < T2 (p = 0.003);

-

-

Time had a significant effect on the change of HAM-D (F = 9.50; p < 0.001) and MADRS (F = 9.40; p < 0.001) scores (Supplementary Fig. 2): in both cases T1 > T2 (p < 0.001);

-

-

Time did not have a significant effect on the change of PANSS (F = 1.37; p = 0.26), YMRS (F = 2.84; p = 0.06) and Y-BOCS (F = 0.55; p = 0.59) scores (Supplementary Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

Although several studies investigated the psychological consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic on the general population, on the health professionals, or subjects affected by mental disorders, only few authors compared patients suffering from different psychiatric disorders (Quittkat et al., 2020). In the present study, an effect of time significantly emerged, with an increase of psychometric scores in conjunction with restrictive measures and an improvement at the reopening on general psychopathology (BPRS), global severity and functioning (CGI severity and improvement), anxiety (HAM-A), disability (both DISS stress and support), and depressive symptoms (HAM-D and MADRS) in patients with affective disorders. Subjects affected by PDs reported overall more anxious symptoms than SKZ patients during the first six months of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Visually, the worsening of general psychopathology in SKZ and of OC symptoms did not substantially improved after the reopening.

The mean age of the entire sample resulted to be quite high, consistently with the context of the recruitment (the Outpatients Unit). In terms of clinical variables, PD patients presented longer DUI compared to the other groups, probably because of the frequent delay in diagnosis and treatment of these disorders, as reported by previous literature, in particular for subjects affected by borderline PD (Bozzatello et al., 2019). Moreover, both PD and SKZ groups needed higher level of care compared to MDD patients, they received more frequently poly-therapy than other groups, and in particular SKZ subjects presented a higher frequency of unemployment and unmarried status, as expected considering the cognitive impairment and the poor social functioning related to this disabling disorder (Green et al., 2014). Interestingly, PD patients presented significantly more frequent alcohol misuse in the 6 months pre-pandemic than the other diagnostic groups, difference that was no longer significant in the 6 months after the COVID-19 outbreak, probably as a consequence of a lower availability of alcohol and substances during the lockdown period.

Regarding psychopathological changes, our analyses revealed that, during the so-called “Phase I” of COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, characterized by the application of strict lockdown measures, psychiatric patients showed significantly higher scores in almost all of administered psychometric scales, compared with the beginning of the pandemic, with a mild improvement at T2 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Despite a general reduction of psychiatric hospitalization rates registered in Northern Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak (Clerici et al., 2020), our results showed a global worsening of psychiatric symptoms, as shown by BPRS and CGI-S scores, particularly for PDs with respect to MDD and anxiety/OCD patients. With the same differences between the diagnoses, a similar trend was detected in DISS-disability scores over time, as expected, considering the financial problems, fear of contagion, and the reorganization of mental health departments occurred during the lockdown period (Moreno et al., 2020). Of note, the COVID-19 outbreak also led to self-isolations and lack of usual support (Hao et al., 2020), as showed by the worsening of DISS-support scores independently from diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. 1). A general improvement, also confirmed by the CGI-I scores (Fig. 2), emerged at the endpoint, indicating that the gradual resumption of social life and usual activities had some positive effects on mental health without diagnostic differences.

An impressive finding concerns SKZ patients, although it did not reach the statistical significance: PANSS scores were the only ones that revealed a further mild worsening at T2, after the symptoms exacerbation at T1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Some factors may be implicated in the worsening of general psychopathology of SKZ patients, such as the stressful event represented by the pandemic, the difficulties in the continuity of care, the isolation among patients and their relatives/caregivers in case of COVID-19 infection (Kozloff et al., 2020). In fact, in our sample, SKZ subjects were more frequently unmarried and this status may have contributed to their psychopathological worsening during lockdown period. Moreover, social restrictions may increase persecutory symptoms, which need more time than others to remit after the reopening (Hamada and Fan, 2020). On the other hand, anxiety symptoms resulted to be significantly lower in this subgroup than in PD patients (Fig. 3). A recent narrative review underlined the negative impact that the pandemic might have had on psychotic symptoms (Zhand and Joober, 2021). In contrast, some authors reported that SKZ patients might show a psychopathological stability with an increased self-reported well-being (Barlati et al., 2021). Similarly to subjects affected by SKZ, OCD patients showed symptom exacerbation with poor improvement when the restrictive measures ended (Supplementary Fig. 2). Other studies, conducted during the lockdown period, confirmed the global worsening of OCD patients (Benatti et al., 2020; Prestia et al., 2020) with increased rates of psychiatric emergency consultations in comparison with the previous year (Capuzzi et al., 2020).

Overall, from our results emerged that PD patients presented a greater psychopathological worsening during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic, with respect to the other diagnostic groups. On the other hand, in our sample, the reduction of pharmacological treatments after the outbreak resulted statistically significant for PD patients, thus probably reflecting a clinical improvement when a return to pre-pandemic conditions occurred (Torales et al., 2020). Although statistically significant, this last result may be considered with caution in the light of the small number of subjects that overall underwent changes in pharmacological treatment. Our findings support the hypothesis that the psychopathology of PD patients is relevantly influenced by social contest and daily-life condition, which should be taking into account in the management of these subjects (Shepherd et al., 2016).

The interpretation of our findings must take into consideration the above-mentioned results about the differences among groups in terms of clinical variables. In fact, the higher level of needed care, the earlier age at onset, the longer DUI, the prevalent substance misuse, the frequent hospitalizations, the more diffused poly-therapy in PD or SKZ patients or both than others, represent negative prognostic factors (Caldiroli et al., 2018; Buoli et al., 2021) or indices of greater severity of illness (Centorrino et al., 2008), and may partially explain the worse psychopathology presented by PD and SKZ subjects at the three time-points.

The present study has some limitations. The sample was selected from Northern Italy population, in Monza district, an area particularly affected by COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the early phases. Therefore, our results may not be generalized to other regions or countries. Moreover, the sample size has not been calculated a priori and it was relatively small, considering that statistical analyses were performed on five diagnostic subgroups with the majority of subjects affected by schizophrenia. In order to allow the comparison between more than two groups, we chose the regression analyses which, on the other hand, did not provide a specific result about the groupXtime interaction. Finally, this is a naturalistic study. This aspect may represent a limitation, for the poorly standardized conditions of enrolment and assessment, and for the presence of a potential interviewer bias; on the other hand, it may be considered a strength of the research, giving a reliable representation of the real clinical world. Other strengths of our research may be the broad panel of enrolled patients, as the study included and compared all major psychiatric diagnoses. It is also one of the first studies specifically investigating the psychopathological impact of COVID-19 pandemic over a relatively long period of observation in comparison to current literature.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alice Caldiroli: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Enrico Capuzzi: Visualization, Data curation. Agnese Tringali: Conceptualization, Investigation. Ilaria Tagliabue: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Marco Turco: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Andrea Fortunato: Investigation, Visualization. Matteo Sibilla: Investigation. Caterina Montana: Investigation. Laura Maggioni: Investigation. Cristian Pellicioli: Investigation. Matteo Marcatili: Resources. Roberto Nava: Resources. Giovanna Crespi: Resources. Fabrizia Colmegna: Project administration, Validation. Massimiliano Buoli: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Massimo Clerici: Project administration, Supervision.

Declarations of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114334.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. (DSM-5®. [Google Scholar]

- Barlati S., Nibbio G., Vita A. Schizophrenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2021;34:203–210. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatti B., Albert U., Maina G., Fiorillo A., Celebre L., Girone N., Fineberg N., Bramante S., Rigardetto S., Dell'Osso B. What happened to patients with obsessive compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic? A multicentre report from tertiary clinics in northern Italy. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:720. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzatello P., Bellino S., Bosia M., Rocca P. Early detection and outcome in borderline personality disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:710. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buoli M., Cesana B.M., Fagiolini A., Albert U., Maina G., de Bartolomeis A., et al. Which factors delay treatment in bipolar disorder? A nationwide study focused on duration of untreated illness. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2021;15:1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/eip.13051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldiroli A., Capuzzi E., Riva I., Russo S., Clerici M., Roustayan C., Abbass A., Buoli M. Efficacy of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy in mood disorders: a critical review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;273:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldiroli A., Serati M., Orsenigo G., Caletti E., Buoli M. Age at onset and social cognitive impairment in clinically stabilized patients with schizophrenia: an ecological cross-sectional study. Iran. J. Psychiatry. 2018;13:84–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuzzi E., Di Brita C., Caldiroli A., Colmegna F., Nava R., Buoli M., Clerici M. Psychiatric emergency care during Coronavirus 2019 (COVID 19) pandemic lockdown: results from a department of mental health and addiction of northern Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centorrino F., Cincotta S.L., Talamo A., Fogarty K.V., Guzzetta F., Saadeh M.G., Salvatore P., Baldessarini R.J. Hospital use of antipsychotic drugs: polytherapy. Compr. Psychiatry. 2008;49:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M., Durbano F., Spinogatti F., Vita A., de Girolamo G., Micciolo R. Psychiatric hospitalization rates in Italy before and during COVID-19: did they change? An analysis of register data. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020;37:283–290. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio dei Ministri, 2020. Delibera del consiglio dei ministri 31 gennaio 2020. Dichiarazione dello stato di emergenza in conseguenza del rischio sanitario connesso all'insorgenza di patologie derivanti da agenti virali trasmissibili. (20A00737) (GU Serie Generale n.26 del 01-02-2020). https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/02/01/20A00737/sg.

- Daly M., Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;286:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Girolamo G., Cerveri G., Clerici M., Monzani E., Spinogatti F., Starace F., Tura G., Vita A. Mental health in the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency-the Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:974–976. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte G., Favieri F., Tambelli R., Casagrande M. COVID-19 pandemic in the italian population: validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:4151. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile A., Torales J., O'Higgins M., Figueredo P., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., De Berardis D., Petito A., Bellomo A., Ventriglio A. Phone-based outpatients' follow-up in mental health centers during the COVID-19 quarantine. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020979732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman W., Price L., Rasmussen S.A., Mazure C., Fleischmann R.L., Hill C.L., Heninger G.R., Charneyet D.S. The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale (Y-BOCS): part I. Development, use and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman W., Price L., Rasmussen S.A., Mazure C., Delgado P., Heninger G.R., Charney D.S. The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale (Y-BOCS): part II. Validity Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Harvey P.D. Cognition in schizophrenia: past, present, and future. Schizophr. Res. Cognit. 2014;1:e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualano M.R., Lo Moro G., Voglino G., Bert F., Siliquini R. Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:4779. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R., Krystal J.H. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the archives of general psychiatry. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 1976. Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (ECDEU) Assessment Manual For Psychopharmacology. Revised, 1976. DHEW Publication No. (ADM) 76-338. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada K., Fan X. The impact of COVID-19 on individuals living with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., McIntyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff N., Mulsant B.H., Stergiopoulos V., Voineskos A.N. The COVID-19 global pandemic: implications for people with schizophrenia and related disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2020;46:752–757. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman R., Naftalovich H., Huppert J.D., Kalanthroff E. Impact of COVID-19 on obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74:660–661. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S.A., Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S., Nordentoft M., Crossley N., Jones N., Cannon M., Correll C.U., Byrne L., Carr S., Chen E.Y.H., Gorwood P., Johnson S., Kärkkäinen H., Krystal J.H., Lee J., Lieberman J., López-Jaramillo C., Männikkö M., Phillips M.R., Uchida H., Vieta E., Vita A., Arango C. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall J.E., Gorham D.R. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psycol. Rep. 1962;10:799–812. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham A.E., Ackerman R.A., Depp C.A., Harvey P.D., Moore R.C. A longitudinal investigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals with pre-existing severe mental illnesses. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestia D., Pozza A., Olcese M., Escelsior A., Dettore D., Amore M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with OCD: effects of contamination symptoms and remission state before the quarantine in a preliminary naturalistic study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti E., Di Pierro R., Fanti E., Madeddu F., Calati R. Personality disorders in time of pandemic. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:80. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01204-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittkat H.L., Düsing R., Holtmann F.J., Buhlmann U., Svaldi J., Vocks S. Perceived impact of Covid-19 across different mental disorders: a study on disorder-specific symptoms, psychosocial stress and behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Harnett-Sheehan K., Raj B.A. The measurement of disability. Int. Clin. Psychopharm. 1996;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd A., Sanders C., Doyle M., Shaw J. Personal recovery in personality disorder: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative methods studies. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2016;62:41–50. doi: 10.1177/0020764015589133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66:317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020. WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020/ (Accessed 03 December 2020).

- Young R.C., Biggs J.T., Ziegler V.E., Meyer D.A. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhand N., Joober R. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: narrative review. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e35. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.