Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can progress rapidly, and patients are often unprepared to make kidney failure treatment decisions. We aimed to better understand patients’ preferences for and experiences of shared and informed decision making (SDM) regarding kidney replacement therapy before kidney failure.

Study Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting & Participants

Adults receiving nephrology care at CKD clinics in rural Pennsylvania.

Predictors

Estimated glomerular filtration rate, 2-year risk for kidney failure, duration and frequency of nephrology care, and preference for SDM.

Outcomes

Occurrence and extent of kidney replacement therapy discussions and participants’ satisfaction with those discussions.

Analytic Approach

Multivariable logistic regression to quantify associations between participants’ characteristics and whether they had discussions.

Results

The 447 study participants had a median age of 72 (IQR, 64-80) years and mean estimated glomerular filtration rate of 33 (SD, 12) mL/min/1.73 m2. Most (96%) were White, high school educated (67%), and retired (65%). Most (72%) participants preferred a shared approach to kidney treatment decision making, and only 35% discussed dialysis or transplantation with their kidney teams. Participants who had discussions (n = 158) were often completely satisfied (63%) but infrequently discussed potential treatment-related impacts on their lives. In multivariable analyses, those with a high risk for kidney failure within 2 years (OR, 3.24 [95% CI, 1.72-6.11]; P < 0.01), longer-term nephrology care (OR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.05-1.20] per 1 additional year; P < 0.01), and more nephrology visits in the prior 2 years (OR, 1.34 [95% CI, 1.20-1.51] per 1 additional visit; P < 0.01) had higher odds of having discussed dialysis or transplantation.

Limitations

Single health system study.

Conclusions

Most patients preferred sharing CKD treatment decisions with their providers, but treatment discussions were infrequent and often did not address key treatment impacts. Longitudinal nephrology care and frequent visits may help ensure that patients have optimal SDM experiences.

Index Words: chronic kidney disease, kidney replacement therapy, shared and informed decision making

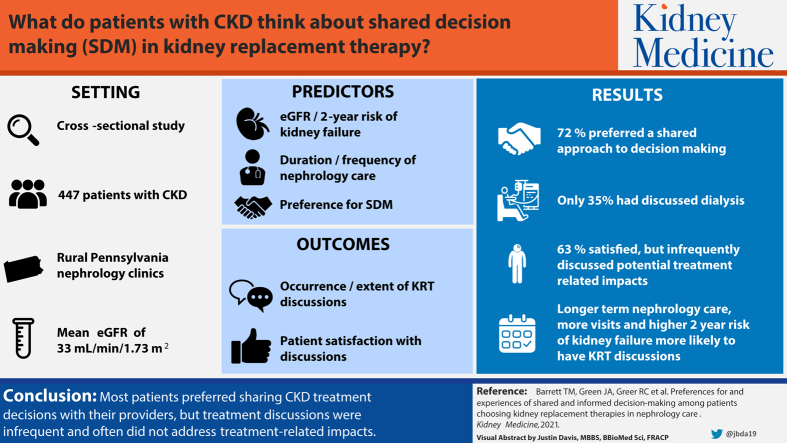

Graphical abstract

Plain-Language Summary.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can progress rapidly, and many patients lack preparation to make last-minute kidney replacement treatment decisions. Shared and informed decision making (SDM) can help ensure that patients receive their preferred treatment. We asked 447 patients with advanced CKD about their preferred role in the treatment decision-making process and whether they engaged with their kidney care teams in discussions about kidney replacement therapies. Most patients preferred SDM but only 35% of patients reported that they discussed dialysis or transplantation. Although patients reported being satisfied with their discussions, many patients also reported that they did not discuss key treatment topics, such as impacts on their finances. More complete discussions are needed to help patients prepare for choosing kidney replacement therapies.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can progress rapidly and unexpectedly to kidney failure, even when patients have already been referred to nephrology care.1, 2, 3 Many patients lack the knowledge and preparation required to make last-minute kidney replacement treatment decisions.4, 5, 6, 7 In these situations, patients may not get to experience their preferred degree of engagement in the kidney treatment decision-making process and the treatment decision may not properly reflect their preferences and values. Given the complexity of choosing a kidney replacement therapy, patients’ decisions should be both shared and informed, and shared and informed decision making (SDM) in kidney care may need to occur over substantial periods. Studying SDM discussions earlier in the disease course may help inform how kidney care teams prepare their patients for kidney failure.

Engaging patients in SDM about kidney replacement therapy options before they develop kidney failure is widely advocated in clinical practice guidelines and public policies.8, 9, 10 Additionally, recent SDM interventions among patients with kidney failure show promising results for improving patients’ decision-making experiences.11, 12, 13 However, patients’ experiences with SDM before they develop kidney failure have not been well studied. In other clinical settings, patients tend to prefer a shared approach to treatment decision making14,15 in which both the patient and health care provider are full participants in the decision-making process.16,17 For chronic diseases such as CKD, SDM ideally incorporates an ongoing dialogue between patients and doctors to allow adequate time for patients to develop their knowledge and preferences about available treatment options.18 Other nonphysician members of the health care team (ie, nurses and case managers) may also participate in this ongoing dialogue.18 We examined patients’ experiences of kidney treatment discussions with their kidney care teams in a large health care system.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study among adults receiving outpatient nephrology care at Geisinger Health in Pennsylvania using data collected in 2017 as part of the PREPARE NOW (Providing Resources to Enhance Patients’ and Families’ Readiness to Engage in Kidney Care: Break the News, Review Your Options, Weigh the Pros and Cons) Study. PREPARE NOW is an ongoing cluster randomized controlled trial (NCT 02722382) evaluating the effectiveness of a health system intervention to improve treatment decisions among patients with CKD.19 As part of PREPARE NOW, a CKD registry was developed to identify patients at risk for CKD progression based on the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) staging criteria.8,20 To minimize inclusion of patients with acute kidney injury, patients were only eligible for the registry if they had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or longer with no normal values in between. All participants in the current study had CKD, were included in the registry, had not initiated kidney replacement therapy, and were in nephrology care for the past 12 months. Participants were also English speaking and at least 18 years of age.

All PREPARE NOW participants completed a standard telephone questionnaire administered by trained research staff and provided consent to obtain their electronic health records (EHRs) before implementation of the health system intervention. The PREPARE NOW Study protocol was approved by the Duke Health Institutional Review Board (Pro00074588).

Study Setting

Located in rural eastern Pennsylvania, Geisinger Health includes 9 nephrology practice sites that provide outpatient nephrology care to approximately 4,000 patients. Between 1 and 3 nephrology providers practice at each clinic, and some providers practice at multiple clinics. Approximately one-third of patients receiving care at Geisinger Health are insured through the Geisinger Health Plan. Patients’ kidney teams at Geisinger Health include their physicians, nurses, and case managers.

Participant Sociodemographic Characteristics

We used standard questionnaires to collect participants’ self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, household size, education, current employment, and marital status. We used participants’ self-reported household income and size to characterize their poverty status (poor, near poor, and not poor) according to federal poverty guidelines.21,22 We assessed participants’ health literacy using the Brief Health Literacy Screening instrument (scores range from 3 [least literate] to 15 [most literate]), and total scores were dichotomized into inadequate/marginal health literacy (≤9) and adequate health literacy (>9).23, 24, 25

Comorbid Conditions, Kidney Function, and End-Stage Kidney Disease Risk

We assessed participants’ comorbidity using the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which ranges from 0 (lowest comorbidity) to 37 (highest comorbidity).26 We used the most recent eGFR that was available in participants’ EHRs before administering the questionnaire to assess their kidney function. We also calculated the Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE), which incorporates age, sex, eGFR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, and calcium, phosphorus, albumin, and bicarbonate levels using the most recent values at the time of survey completion, to estimate participants’ risk for developing end-stage kidney disease within 2 years.27 Participants’ 2-year risk for kidney failure was considered low (<6%), moderate (6%-10%), or high (>10%) based on the recommended risk categories for the KFRE.27

Patient EHR data are screened nightly to identify individuals at a “high-risk” KFRE threshold among those included in the CKD registry implemented at Geisinger Health as part of PREPARE NOW. Patients in the high-risk category are considered to have an imminent risk for kidney failure and should be engaged in kidney treatment discussions by their care teams.19,20 Given that KDIGO guidelines recommend that patients are engaged in kidney treatment discussions when their eGFR is <30 mL/min/1.73 m2,8 we examined whether participants who were not high risk according to the KFRE but had eGFRs < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 were more or less likely to have discussed kidney replacement therapies than participants who were not high risk and had eGFRs ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. To do so, we created a combined variable that included: (1) high risk for kidney failure, (2) eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and low or moderate risk for kidney failure, and (3) eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and low or moderate risk for kidney failure.

Participants’ Nephrology Care

We ascertained the date of participants’ first outpatient nephrology visit at Geisinger Health from their EHRs and used this date to define the time they had been in nephrology care before participating in the study. We also assessed how many nephrology appointments they completed in the previous 2 years using EHR data. We included both measures to capture separately the length (years) and intensity (frequency) of nephrology care. These variables were not strongly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.07).

Preferences for and Experiences of SDM

Given that high-quality shared decision-making discussions should also be informed, we assessed participants’ preferences for and experiences of shared and informed decision-making (referred to throughout as SDM). In doing so, we asked participants a range of questions across domains important to high-quality SDM discussions, including whether discussions occurred; participants’ perceived completeness of those discussions and whether key topics were discussed; and participants’ satisfaction with discussions. Although other tools capture the decision-making process in specific clinical encounters,28 our objective was to gain insight into participants’ decision-making preferences and experiences throughout their history of nephrology care.

To assess participants’ preferred role in kidney treatment decision making, we used the validated Control Preferences Scale29 and asked “What role would you like to play when making decisions about your kidney treatments?” (“I make all the final decisions,” “The doctor and I make the final decisions together” [ie, SDM], “The doctor considers some of my ideas but still makes most, if not all of the final decisions,” “The doctor takes the initiative and decides what is best for me,” or “I don’t know”). We then assessed whether participants discussed treatments for kidney failure with their kidney care teams by asking “Have you and your kidney team ever talked about dialysis or a transplant (in which you would get another person’s kidney, either by being placed on the waiting list or by getting a kidney from someone you know)?” (“no” or “yes”).

Among participants who had discussions, we asked 5 additional questions to assess the extent to which they discussed each modality of kidney treatment. With similar wording, we asked, “To what extent has your kidney team explained to you (1) hemodialysis in a dialysis center, (2) home hemodialysis, (3) peritoneal dialysis or PD, (4) medical management of kidney failure with no dialysis or transplant, and (5) kidney transplant?” (“not at all,” “a little,” “mostly,” “completely,” or “don’t know”).

We also asked these participants 5 yes or no questions to assess whether they discussed the potential impacts of kidney replacement therapies across 5 domains: (1) “Have you and your kidney team talked about how each of the different kidney treatment options might affect the quality of your life on a day-to-day basis?,” (2) “Have you and your kidney team talked about how each of the different kidney treatment options might affect how long you will live?,” (3) “Have you and your kidney team talked about how insurance coverage for each of the different kidney treatment options might affect your money matters?,” (4) “Have you and your kidney team talked about how each of the different kidney treatment options might affect your family’s well-being?,” and (5) “Have you and your kidney team talked about how each of the different kidney treatment options might affect your need for help from family and friends?.” We created a scale to assess the total number of topics participants discussed, ranging from 0 (no topics) to 5 (all topics).

Finally, we asked participants to report their satisfaction with their kidney team discussions: “How satisfied are you with your talks with your kidney team about kidney treatment options? Would you say…” (“not at all satisfied,” “a little satisfied,” “mostly satisfied,” “completely satisfied,” or “don’t know”).

Statistical Analyses

We described participants’ characteristics and SDM preferences, both overall and by whether they had kidney treatment discussions. Among participants who reported having discussions, we described the extent to which they discussed different treatment modalities (ie, in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, PD, conservative management, and transplantation), if they discussed patient-centered aspects of treatments (ie, their quality of life, length of life, family’s well-being, need for help from family and friends, and finances), and their discussion satisfaction.

We then constructed 2 multivariable logistic regression models. The first model assessed the association of participants’ characteristics with their odds of having discussed kidney treatments with their kidney care teams. The second model assessed the association between the number of topics participants discussed and their odds of being “completely” (vs less than completely) satisfied with their discussions. This second model was restricted to the subgroup of participants who had discussions and should not be generalized to all study participants. Variables included in the models were chosen a priori based on their potential to influence discussions or to act as confounders of the association between SDM preference and discussions. In the subgroup at high risk for kidney failure (>10% based on the KFRE) and the subgroup with eGFRs < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the extent to which different treatment modalities were discussed and whether they discussed patient-centered aspects of treatments.

All hypothesis tests were 2 sided at the 0.05 significance level and were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participants’ Characteristics and Preferred Role in Decision Making

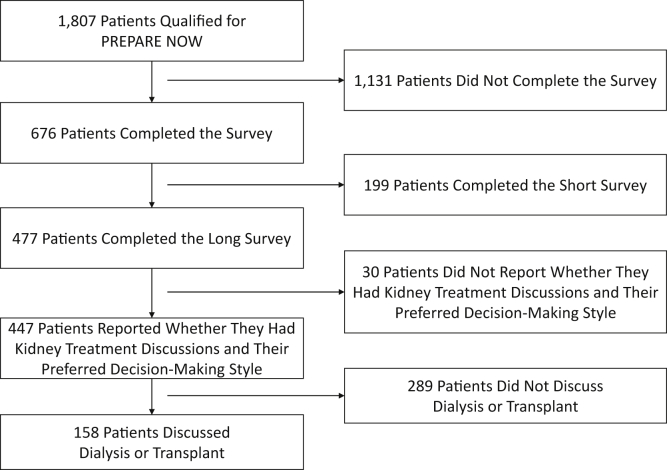

Of the 1,807 patients who were eligible for PREPARE NOW, 447 completed the questionnaire and were included in the analytical sample (Fig 1). Study participants tended to be younger than nonparticipants (median age, 72 [interquartile range [IQR], 64-80] vs 79 [IQR, 70-85] years). Most of the 447 participants were White (96%), not poor (83%), high school educated (67%), and retired (65%) and had adequate health literacy (66%). Approximately half (55%) were married or living with a partner. Most participants had stage 3b (45%) or stage 4 (35%) CKD. Overall, participants’ mean eGFR was 33 (standard deviation [SD], 12) mL/min/1.73 m2, and 17% were at a high risk for kidney failure within the next 2 years. Their median comorbidity index score was 5 [IQR, 3-7]. Participants had spent a median of 4 [IQR, 2-7] years in nephrology care and completed a median of 4 [IQR, 3-5] nephrology visits in the previous 2 years (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram describing steps to analytical sample.

Table 1.

Participant Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Stratified by Whether They Reported Discussing Dialysis or Transplantation With Their Kidney Teams

| Characteristics | Total (N = 447) | Did Not Discuss Dialysis or Transplant (n = 289) | Discussed Dialysis or Transplant (n = 158) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 72 [64-80] | 74 [67-81] | 68 [58-78] | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.99 | |||

| Female | 263 (58.8%) | 170 (58.8%) | 93 (58.9%) | |

| Male | 184 (41.2%) | 119 (41.2%) | 65 (41.1%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.58 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 431 (96.4%) | 278(96.2%) | 153 (96.8%) | |

| Other race/ethnicitya | 14 (3.1%) | 9 (3.1%) | 5 (3.2%) | |

| Don't know | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Poverty | 0.59 | |||

| Not poor | 370 (82.8%) | 241 (83.4%) | 129 (81.6%) | |

| Near poor | 40 (8.9%) | 23 (8.0%) | 17 (10.8%) | |

| Poor | 37 (8.3%) | 25 (8.7%) | 12 (7.6%) | |

| Education | 0.09 | |||

| <High school | 58 (13.0%) | 46 (15.9%) | 12 (7.6%) | |

| High school graduate/GED | 299 (66.9%) | 185 (64.0%) | 114 (72.2%) | |

| College graduate | 87 (19.5%) | 56 (19.4%) | 31 (19.6%) | |

| Missing/refused/don't know | 3 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Employment | 0.007 | |||

| Working/looking forwork | 84 (18.8%) | 48 (16.6%) | 36 (22.8%) | |

| Unemployed | 4 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Retired due todisability | 58 (13.0%) | 29 (10.0%) | 29 (18.4%) | |

| Retired | 292 (65.3%) | 205 (70.9%) | 87 (55.1%) | |

| Missing/refused/don't know | 9 (2.0%) | 6 (2.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Marital status | 0.06 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 247 (55.3%) | 156 (54.0%) | 91 (57.6%) | |

| Widowed | 107 (23.9%) | 79 (27.3%) | 28 (17.7%) | |

| Separated/divorced | 64 (14.3%) | 40 (13.8%) | 24 (15.2%) | |

| Never married | 28 (6.3%) | 13 (4.5%) | 15 (9.5%) | |

| Missing/refused/don’t know | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 33 (12) | 35 (11) | 29 (13) | <0.001 |

| CKD stageb | <0.001 | |||

| Stage G2 (eGFR = 60) | 9 (2.0%) | 6 (2.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Stage G3a (60 > eGFR ≥ 45) | 55 (12.3%) | 41 (14.2%) | 14 (8.9%) | |

| Stage G3b (45 > eGFR ≥ 30) | 202 (45.2%) | 153 (52.9%) | 49 (31.0%) | |

| Stage G4 (30 > eGFR ≥ 15) | 155 (34.7%) | 84 (29.1%) | 71 (44.9%) | |

| Stage G5 (eGFR < 15) | 26 (5.8%) | 5 (1.7%) | 21 (13.3%) | |

| 2-y risk for ESKDc | <0.001 | |||

| High | 77 (17.2%) | 28 (9.7%) | 49 (31.0%) | |

| Moderate | 28 (6.3%) | 12 (4.2%) | 16 (10.1%) | |

| Low | 338 (75.6%) | 247 (85.5%) | 91 (57.6%) | |

| Undetermined | 4 (0.9%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Combined eGFR/ESKD risk | <0.001 | |||

| High risk | 77 (17.2%) | 28 (9.7%) | 49 (31.0%) | |

| <30, low or moderate risk | 104 (23.3%) | 61 (21.1%) | 43 (27.2%) | |

| ≥30, low or moderate risk | 262 (58.6%) | 198 (68.5%) | 64 (40.5%) | |

| Undetermined | 4 (0.9%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | 5 [3-7] | 5 [3-7] | 5 [3-7] | 0.31 |

| Health literacyd | ||||

| Inadequate/marginalhealth Literacy | 151 (33.8%) | 99 (34.3%) | 52 (32.9%) | 0.77 |

| Adequate health literacy | 296 (66.2%) | 190 (65.7%) | 106 (67.1%) | |

| Insurance | 0.009 | |||

| Commercial | 96 (21.5%) | 52 (18.0%) | 44 (27.8%) | |

| Medicare | 312 (69.8%) | 216 (74.7%) | 96 (60.8%) | |

| Medicaid/government/other | 39 (8.7%) | 21 (7.3%) | 18 (11.4%) | |

| Years in nephrology care | 4 [2-7] | 3 [2-6] | 5 [3-7] | <0.001 |

| No. of nephrology visits in the past 2 years | 4 [3-5] | 4 [2-5] | 5 [3-7] | <0.001 |

| Preferred role in kidney treatment decision making | 0.37 | |||

| “I make all the final decisions” | 66 (14.8%) | 39 (13.5%) | 27 (17.1%) | |

| “The doctor and I make the final decisions together” (ie, shared decision making) | 322 (72.0%) | 209 (72.3%) | 113 (71.5%) | |

| “The doctor considers some of my ideas but still makes most, if not all of the final decisions” | 19 (4.3%) | 11 (3.8%) | 8 (5.1%) | |

| “The doctor takes the initiative and decides what is best for me” | 40 (8.9%) | 30 (10.4%) | 10 (6.3%) | |

Note: Values expressed as median [interquartile range], number (percent), or mean (standard deviation.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GED, general equivalency diploma.

Other race/ethnicity includes Black, African American, or Negro; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian American, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander; and some other race.

eGFR categories may not match inclusion criteria due to the timing of survey administration or participants’ most recent laboratory values.

Risk categories based on the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.27

Most (72%) participants preferred a shared approach to kidney treatment decision making (ie, “The doctor and I make the final decisions together”). Only 15% of participants preferred to make all the decisions themselves, while even fewer preferred that their doctor makes all the decisions for them (9%) and that their doctor considers some of their ideas but makes most, if not all, of the final decisions (4%). Those who preferred SDM and those who wanted their doctor to consider some of their ideas tended to be younger (median, 72 [IQR, 64-80] and 67 [IQR,61-81] years, respectively) than those who wanted to make all the decisions themselves (median, 73 [IQR, 67-81] years) and those who wanted their doctor to make the final decisions (median, 77 [IQR, 73-83] years).

Characteristics Associated With SDM Discussions

Of the 447 study participants, 158 (35%) reported that they discussed dialysis or transplantation with their kidney care teams. Those who discussed (vs did not discuss) dialysis or transplantation tended to be younger (median, 68 [IQR, 58-78] vs 74 [IQR, 67-81] years) and were less likely to be retired (55% vs 71%). Those who discussed dialysis or transplantation had lower eGFRs (mean, 29 [SD, 13] vs 35 [SD, 11] mL/min/1.73 m2) and were more likely to be at a high risk for kidney failure within 2 years (31% vs 10%). They were also in nephrology care for more years (median, 5 [IQR, 3-7] vs 3 [IQR, 2-6]) and completed more nephrology appointments in the previous 2 years (median, 5 [IQR, 3-7] vs 4 [IQR, 2-5]; Table 1).

In a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, older participants had lower odds of having discussed (vs not) dialysis or transplantation with their kidney care teams (odds ratio [OR], 0.96 [95% CI, 0.94-0.98] per 1-year increase; P < 0.01). Participants who were at high risk for kidney failure within 2 years (vs low/moderate risk and eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2; OR, 3.24 [95% CI, 1.72-6.11]; P < 0.01), in nephrology care for a longer period (OR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.05-1.20] per 1-year increase; P < 0.01), and completed more nephrology visits in the prior 2 years (OR, 1.34 [95% CI, 1.20-1.51] per 1-visit increase; P < 0.01) had higher odds of having discussed (vs not) dialysis or transplantation. Preference for SDM was not statistically significantly associated with whether participants discussed kidney replacement therapy with their care team (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds of Participants Having Discussed Dialysis or Transplantation With Their Kidney Teams

| Characteristics | Unadjusted (N = 447) |

Adjusteda (N = 447) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | ||||

| 1-Unit increase | 0.95 (0.94-0.97) | <0.01 | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | <0.01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | 0.99 | Reference | 0.84 |

| Male | 1.00 (0.67-1.48) | 0.95 (0.58-1.56) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | >0.99 | Reference | 0.90 |

| Other race/ethnicityb | 1.01 (0.33-3.07) | 0.73 (0.19-2.84) | ||

| Poverty | ||||

| Not poor | Reference | 0.64 | Reference | 0.21 |

| Poor or near poor | 1.13 (0.68-1.88) | 1.50 (0.79-2.83) | ||

| Education | ||||

| <High school | Reference | 0.10 | Reference | 0.15 |

| High school graduate/GED | 2.36 (1.20-4.65) | 2.44 (1.13-5.28) | ||

| College graduate | 2.12 (0.98-4.59) | 2.43 (0.97-6.08) | ||

| Combined eGFR/ESKD riskc | ||||

| ≥30, low or moderate risk | Reference | <0.01 | Reference | <0.01 |

| <30, low or moderate risk | 2.18 (1.35-3.53) | 2.01 (1.14-3.53) | ||

| High risk | 5.41 (3.15-9.32) | 3.24 (1.72-6.11) | ||

| Undetermined | 3.09 (0.43-22.41) | 4.51 (0.51-39.9) | ||

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | Reference | Reference | ||

| Commercial | 1.90 (1.19-3.04) | 0.01 | 1.42 (0.78-2.59) | 0.51 |

| Medicaid/government/other | 1.93 (0.98-3.78) | 1.05 (0.43-2.56) | ||

| Years in nephrology care | ||||

| 1-Unit increase | 1.15 (1.08-1.22) | <0.01 | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | <0.01 |

| No. of nephrologist visits in past 2 y | ||||

| 1-Unit increase | 1.39 (1.26-1.54) | <0.01 | 1.34 (1.20-1.51) | <0.01 |

| Preferred role in kidney treatment decision making | ||||

| Do not prefer SDM | Reference | 0.86 | Reference | 0.94 |

| Prefer SDM | 0.96 (0.62-1.48) | 0.98 (0.58-1.65) | ||

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GED, general equivalency diploma; OR, odds ratio; SDM, shared and informed decision making.

Mutually adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty, education, eGFR/ESKD risk, years in nephrology care, and number of nephrology visits in the past 2 years.

Other race/ethnicity includes Black, African American, or Negro; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian American, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander; and some other race.

Risk categories based on the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.27

Quality of SDM Discussions

Among the 158 participants who discussed dialysis or transplantation with their kidney care teams, fewer than half reported that they completely (vs less than completely) discussed conservative management (37%), in-center hemodialysis (30%), kidney transplantation (24%), home hemodialysis (19%), and PD (15%). Participants most frequently reported that they discussed how each of the different kidney treatment options might affect their quality of life on a day-to-day basis (54%), followed by the impact on their length of life (44%), need for help from family or friends (34%), family’s well-being (28%), and finances (23%). Most (63%) participants reported that they were “completely” (vs less than completely) satisfied with their discussions.

Only 22 (14%) participants discussed all 5 topics, but a greater percentage of those who were completely satisfied with their discussions discussed all 5 topics than those who were less than completely satisfied with their discussions (18% vs 7%). In an adjusted logistic regression model, participants who discussed all 5 (vs zero) topics had higher odds of being completely (vs less than completely) satisfied with their discussions (OR, 6.20 [95% CI, 1.60-24.01]; P=0.03). Preference for SDM was not statistically significantly associated with participants’ discussion satisfaction (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant Satisfaction With Kidney Team Discussions Among Participants Who Had Discussions

| Characteristics | Satisfaction With Discussions |

Adjusted Odds of Being Completely Satisfied With Discussionsa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 158) | Completely Satisfied (n = 99) | Not at All/A Little/Mostly Satisfied (n = 59) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age, y | 68 [58-77] | 68 [60-76] | 68 [56-79] | 1.03 (0.99-1.06) | 0.18 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 93 (58.9%) | 54 (54.5%) | 39 (66.1%) | Reference | 0.35 |

| Male | 65 (41.1%) | 45 (45.5%) | 20 (33.9%) | 1.48 (0.65-3.41) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 153 (96.8%) | 95 (96.0%) | 58 (98.3%) | Reference | 0.40 |

| Other race/ethnicityb | 5 (3.2%) | 4 (4.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 3.08 (0.23-41.68) | |

| Poverty | |||||

| Not poor | 129 (81.6%) | 80 (80.8%) | 49 (83.1%) | Reference | 0.22 |

| Poor or near poor | 29 (18.4%) | 19 (19.2%) | 10 (16.9%) | 2.00 (0.66-6.08) | |

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 12 (7.6%) | 9 (9.1%) | 3 (5.1%) | Reference | 0.83 |

| High school graduate/GED | 114 (72.2%) | 68 (68.7%) | 46 (78.0%) | 0.51 (0.11-2.41) | |

| College graduate | 31 (19.6%) | 21 (21.2%) | 10 (16.9%) | 0.65 (0.11-3.87) | |

| Combined eGFR/ESKD riskc | |||||

| ≥30, low or moderate risk | 64 (40.5%) | 44 (44.4%) | 20 (33.9%) | Reference | 0.47 |

| <30, low or moderate risk | 43 (27.2%) | 23 (23.2%) | 20 (33.9%) | 0.46 (0.17-1.23) | |

| High risk | 49 (31.0%) | 31 (31.3%) | 18 (30.5%) | 0.63 (0.24-1.70) | |

| Undetermined | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0.71 (0.03-15.93) | |

| Insurance | |||||

| Medicare | 96 (60.8%) | 60 (60.6%) | 36 (61.0%) | Reference | 0.23 |

| Commercial | 44 (27.8%) | 30 (30.3%) | 14 (23.7%) | 1.96 (0.68-5.61) | |

| Medicaid/government/other | 18 (11.4%) | 9 (9.1%) | 9 (15.3%) | 0.66 (0.16-2.67) | |

| Years in nephrology care | 5 [3-7] | 5 [3-8] | 4 [3-6] | 1.10 (0.99-1.22) | 0.07 |

| No. of completed nephrology visits in the past 2 years | 5 [3-7] | 5 [3-7] | 4 [3-6] | 0.93 (0.81-1.08) | 0.36 |

| Preferred role in kidney treatment decision making | |||||

| Do not prefer SDM | 45 (28.5%) | 26 (26.3%) | 19 (32.2%) | Reference | 0.60 |

| Prefer SDM | 113 (71.5%) | 73 (73.7%) | 40 (67.8%) | 1.27 (0.52-3.09) | |

| No. of discussion topics discussed | |||||

| 0 of 5 | 57 (36.1%) | 25 (25.3%) | 32(54.2%) | Reference | 0.03 |

| 1 of 5 | 24 (15.2%) | 15 (15.2%) | 9 (15.3%) | 2.15 (0.74-6.28) | |

| 2 of 5 | 23 (14.6%) | 16 (16.2%) | 7 (11.9%) | 2.08 (0.65-6.71) | |

| 3 of 5 | 18 (11.4%) | 12 (12.1%) | 6 (10.2%) | 2.04 (0.55-7.58) | |

| 4 of 5 | 14 (8.9%) | 13 (13.1%) | 1 (1.7%) | 21.62 (2.29-203.87) | |

| 5 of 5 | 22 (13.9%) | 18 (18.2%) | 4 (6.8%) | 6.20 (1.60-24.01) | |

Note: Values expressed as median [interquartile range] or number (percent) unless noted otherwise.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GED, general equivalency diploma; OR, odds ratio; SDM, shared and informed decision making.

Mutually adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty, education, eGFR/ESKD risk, insurance, years in nephrology care, number of nephrology visits in the past 2 years, and preferred role in kidney treatment decision making.

Other race/ethnicity includes Black, African American, or Negro; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian American, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander; and some other race.

Risk categories based on the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.27

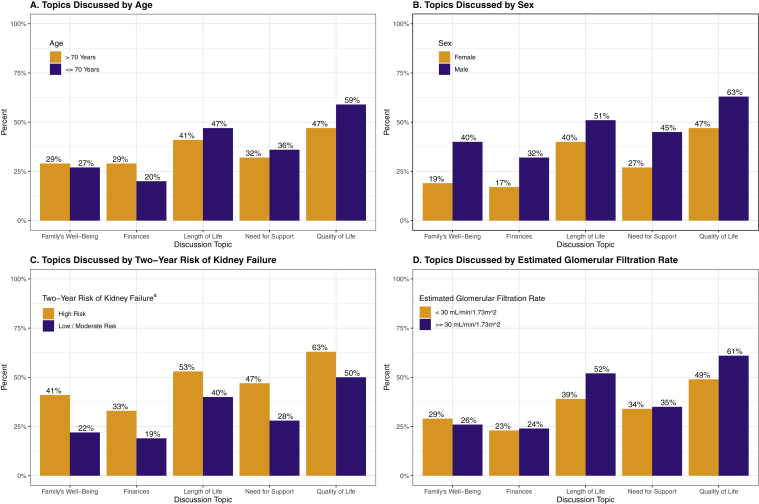

Among the subgroup of 49 participants who discussed dialysis or transplantation with their kidney care teams and were at a high risk for kidney failure within the next 2 years, fewer than half reported that they completely (vs less than completely) discussed transplantation (45%), in-center hemodialysis (47%), conservative management (43%), home hemodialysis (31%), and PD (31%). Similarly, fewer than half of the 92 participants with eGFRs < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 completely discussed transplantation (32%), in-center hemodialysis (36%), conservative management (33%), home hemodialysis (22%), and PD (19%). The frequency of topics discussed for each subgroup varied by topic (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Patient-centered kidney treatment topics discussed by age, sex, and chronic kidney disease severity. aRisk categories based on the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.27

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, most participants preferred SDM when considering their kidney replacement therapy options. However, only 35% reported that they discussed kidney transplantation or dialysis with their kidney care teams. When discussions occurred, participants frequently reported being satisfied, but key treatment topics were infrequently discussed. These findings demonstrate the importance of SDM to patients with CKD and suggest areas in which SDM can be improved.

This study is among the first to systematically explore patients’ preferences for and experiences of SDM in nephrology care before the development of end-stage kidney disease. One mixed-methods study conducted among patients receiving maintenance dialysis found that only 20% of participants recalled being asked about their values and preferences for dialysis before beginning treatment.30 Audiotaped encounters between primary care providers and patients with earlier stage CKD and CKD risk factors found that providers often use high levels of technical jargon and do not check patients’ comprehension.31,32 Our findings build on these prior studies by exploring patients’ experiences of SDM discussions with their full kidney care teams.

SDM discussions were more prevalent among participants who were under the care of their nephrologists for longer periods, completed more nephrology visits, and were at a high risk for kidney failure in the next 2 years. Even among those with a high risk for kidney failure, approximately a third had not discussed dialysis or transplantation. These findings highlight the importance of establishing longitudinal patient-provider relationships to promote SDM in kidney care, but they also show the need to enhance discussions, even in the context of longitudinal care. In other areas, such as cancer and pediatric chronic diseases, the decision-making process is often iterative and not limited to a single clinical encounter.33,34 Given the complexity of kidney treatment decision making, SDM in kidney care may need to occur over substantial periods.

Although most participants in our study preferred SDM, our results do not indicate that preference for SDM is associated with the actual occurrence of discussions. Prior studies also suggest that patients generally prefer SDM in other therapeutic areas.14,15 However, our findings suggest that patients may not initiate SDM discussions simply because it is their preference. Rather, these patients may be waiting for their providers to engage them in such discussions, and kidney care teams should be aware that patients may not actively pursue their preferred decision-making style. Decision aids developed for enhancing patient-provider communication in kidney care may be useful tools to help providers initiate SDM discussions.11,12 In recent years, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has also prioritized SDM in kidney care.35 For example, the CMS Kidney Care Choices Model encourages patient education and SDM to help patients make choices about their kidney replacement therapies before initiation.35

Despite high rates of satisfaction with discussions, participants reported that they did not cover topics that could inform their decision making (eg, finances). Prior work also found that full engagement in SDM does not always coincide with high patient-reported satisfaction.36,37 Some models for conducting patient-provider discussions are guided by patient concerns and do not emphasize covering topics that patients may not deem relevant to their values.38, 39, 40 However, studies of patients who transition to kidney failure have demonstrated that patients and families believe that people with kidney disease should be informed about these aspects of treatments before developing kidney failure.41,42 Our findings suggest that patient satisfaction may not accurately capture the quality of SDM, and assessments of SDM interventions may benefit from more precise measures, such as the patient-reported measure CollaboRATE.28

Our study had several limitations. The study population in rural Pennsylvania was mostly White and older than the general public. Thus, study participants may differ from other populations with CKD, potentially influencing the generalizability of our findings. Participants were also patients at Geisinger Health, which provides resources (eg, care management programs) that may not be available to adults with CKD in other settings. Our study included participants at earlier and later stages of CKD. Clinical practice guidelines do not explicitly recommend engaging patients with earlier stages of CKD in discussions about kidney replacement therapies, and we did not have data on whether patients were contraindicated for receiving a transplant. Kidney care teams may have been particularly hesitant to engage in SDM with older participants who had earlier-stage CKD given that adults 75 years or older with eGFRs > 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 have a higher risk for death than progression to ESKD.43 Participants self-reported their experience of SDM discussions and we did not directly observe their interactions. Nonetheless, patients’ recollections of their discussions may be closely related to the information they have retained before making treatment decisions.

In summary, most study participants preferred a shared approach to kidney treatment decision making. Despite this preference, discussions were infrequent and were often incomplete when they occurred. Our results indicate that longitudinal nephrology care with more frequent visits may facilitate SDM discussions between patients and their kidney care teams.

Article Information

PREPARE NOW Study Team Members

Duke University, Durham, NC (L. Ebony Boulware, Clarissa Diamantidis, Clare Il’Giovine, George Jackson, Jane Pendergast, Sarah Peskoe, Tara Strigo); Geisinger Health System, Danville, PA (Jon Billet, Jason Browne, Ion Bucaloiu, Charlotte Collins, Daniel Davis, Sherri Fulmer, Jamie Green, Chelsie Hauer, Evan Norfolk, Michelle Richner, Cory Siegrist, Wendy Smeal, Rebecca Stametz, Mary Solomon, Christina Yule); Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Patti Ephraim, Raquel Greer, Felicia Hill-Briggs); University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC (Teri Browne); University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba (Navdeep Tangri); members of the Patient and Family Caregiver Stakeholder Group (Brian Bankes, Shakur Bolden, Patricia Danielson, Katina Lang-Lindsey, Suzanne Ruff, Lana Schmidt, Amy Swoboda, Peter Woods); American Association of Kidney Patients (Diana Clynes); Council of Nephrology Social Workers (Stephanie Stewart); Medical Education Institute (Dori Schatell, Kristi Klicko); Mid-Atlantic Renal Coalition (Brandi Vinson); National Kidney Foundation (Jennifer St. Clair Russell, Kelli Collins, Jennifer Martin); Renal Physicians Association (Dale Singer); and Pennsylvania Medical Society (Diane Littlewood).

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Tyler M. Barrett, MA, Jamie A. Green, MD, MS, Raquel C. Greer, MD, MHS, Patti L. Ephraim, MPH, Sarah Peskoe, PhD, Jane F. Pendergast, PhD, Chelsie L. Hauer, MPH, Tara S. Strigo, MPH, Evan Norfolk, MD, Ion Dan Bucaloiu, MD, Clarissa J. Diamantidis, MD, MHS, Felicia Hill-Briggs, PhD, Teri Browne, PhD, MSW, George L. Jackson, PhD, and L. Ebony Boulware, MD, MPH; on behalf of the PREPARE NOW study investigators.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: TMB, JAG, PLE, LEB; data analysis: TMB, SP, JFP, LEB; intellectual contributions/interpretation: TMB, JAG, RCG, PLE, CLH, TSS, EN, IDB, CJD, FH-B, TB, GLJ, LEB; supervision and mentorship: LEB, JAG. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, accepts personal accountability for the author’s own contributions, and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Program Award (IHS-1409-20967). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the physicians, nurses, medical assistants, staff, and patients of Geisinger Health, Danville, PA.

Peer Review

Received January 27, 2021, as a submission to the expedited consideration track with 3 external peer reviews. Direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form May 31, 2021.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Contributor Information

L. Ebony Boulware, Email: ebony.boulware@duke.edu.

PREPARE NOW study investigators:

L. Ebony Boulware, Clarissa Diamantidis, Clare Il’Giovine, George Jackson, Jane Pendergast, Sarah Peskoe, Tara Strigo, Jon Billet, Jason Browne, Ion Bucaloiu, Charlotte Collins, Daniel Davis, Sherri Fulmer, Jamie Green, Chelsie Hauer, Evan Norfolk, Michelle Richner, Cory Siegrist, Wendy Smeal, Rebecca Stametz, Mary Solomon, Christina Yule, Patti Ephraim, Raquel Greer, Felicia Hill-Briggs, Teri Browne, Navdeep Tangri, Brian Bankes, Shakur Bolden, Patricia Danielson, Katina Lang-Lindsey, Suzanne Ruff, Lana Schmidt, Amy Swoboda, Peter Woods, Diana Clynes, Stephanie Stewart, Dori Schatell, Kristi Klicko, Brandi Vinson, Jennifer St. Clair Russell, Kelli Collins, Jennifer Martin, Dale Singer, and Diane Littlewood

References

- 1.Buck J., Baker R., Cannaby A.M., Nicholson S., Peters J., Warwick G. Why do patients known to renal services still undergo urgent dialysis initiation? A cross-sectional survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(11):3240–3245. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelssohn D.C., Curtis B., Yeates K., et al. Suboptimal initiation of dialysis with and without early referral to a nephrologist. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(9):2959–2965. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes S.A., Mendelssohn J.G., Tobe S.W., McFarlane P.A., Mendelssohn D.C. Factors associated with suboptimal initiation of dialysis despite early nephrologist referral. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(2):392–397. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein F.O., Story K., Firanek C., et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008;74(9):1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadem S.Z., Walker D.R., Abbott G., et al. Satisfaction with renal replacement therapy and education: the American Association of Kidney Patients survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(3):605–612. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06970810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Biesen W., van der Veer S.N., Murphey M., Loblova O., Davies S. Patients' perceptions of information and education for renal replacement therapy: an independent survey by the European Kidney Patients' Federation on information and support on renal replacement therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verberne W.R., Konijn W.S., Prantl K., et al. Older patients' experiences with a shared decision-making process on choosing dialysis or conservative care for advanced chronic kidney disease: a survey study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:264. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Working Group KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2009. Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act, Section 152(b): Coverage of Kidney Disease Patient Education Services. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Department of Health and Human Services . United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. Advancing American Kidney Health.https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/262046/AdvancingAmericanKidneyHealth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulware L.E., Ephraim P.L., Ameling J., et al. Effectiveness of informational decision aids and a live donor financial assistance program on pursuit of live kidney transplants in African American hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:107. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0901-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finderup J., Jensen J.K.D., Lomborg K. Developing and pilot testing a shared decision-making intervention for dialysis choice. J Renal Care. 2018;44(3):152–161. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finderup J., Lomborg K., Jensen J.D., Stacey D. Choice of dialysis modality: patients' experiences and quality of decision after shared decision-making. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:330. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01956-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiesler D.J., Auerbach S.M. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(3):319–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chewning B., Bylund C.L., Shah B., Arora N.K., Gueguen J.A., Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles C., Gafni A., Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charles C., Gafni A., Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montori V.M., Gafni A., Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9(1):25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green J.A., Ephraim P.L., Hill-Briggs F.F., et al. Putting patients at the center of kidney care transitions: PREPARE NOW, a cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;73:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green JA, Ephraim PL, Hill-Briggs FF, et al. Integrated digital health system tools to support decision making and treatment preparation in CKD: the PREPARE NOW study. Kidney Med. 2021;3(4):565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hokayem C., Heggeness M. Living near poverty in the United States: 1966-2012. United States Census Bureau; 2014. pp. 1–26.https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p60-248.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Poverty Guidelines Updated Periodically in the Federal Register by the U.S . 2018. Department of Health and Human Services under the Authority of 42 U.S.C. 9902(2). 83 FR 2644; 2018-00814; pp. 2642–2644.https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/01/18/2018-00814/annual-update-of-the-hhs-poverty-guidelines [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chew L.D., Bradley K.A., Boyko E.J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace L.S., Rogers E.S., Roskos S.E., Holiday D.B., Weiss B.D. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew L.D., Griffin J.M., Partin M.R., et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson M., Szatrowski T.P., Peterson J., Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tangri N., Stevens L.A., Griffith J., et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elwyn G., Barr P.J., Grande S.W., Thompson R., Walsh T., Ozanne E.M. Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degner L.F., Sloan J.A., Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song M.K., Lin F.C., Gilet C.A., Arnold R.M., Bridgman J.C., Ward S.E. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2815–2823. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greer R.C., Cooper L.A., Crews D.C., Powe N.R., Boulware L.E. Quality of patient-physician discussions about CKD in primary care: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(4):583–591. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy K.A., Greer R.C., Roter D.L., et al. Awareness and discussions about chronic kidney disease among african-americans with chronic kidney disease and hypertension: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern ed. 2020;35(1):298–306. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05540-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipstein E.A., Britto M.T. Evolution of pediatric chronic disease treatment decisions: a qualitative, longitudinal view of parents' decision-making process. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(6):703–713. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15581805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beryl L.L., Rendle K.A., Halley M.C., et al. Mapping the decision-making process for adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: the role of decisional resolve. Med Decis Making. 2017;37(1):79–90. doi: 10.1177/0272989X16640488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model. 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/kidney-care-choices-kcc-model Accessed May 12, 2021.

- 36.Saba G.W., Wong S.T., Schillinger D., et al. Shared decision making and the experience of partnership in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(1):54–62. doi: 10.1370/afm.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brom L., De Snoo-Trimp J.C., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B.D., Widdershoven G.A., Stiggelbout A.M., Pasman H.R. Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: a qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):69–84. doi: 10.1111/hex.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Childers J.W., Back A.L., Tulsky J.A., Arnold R.M. REMAP: A framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e844–e850. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.018796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schell J.O., Arnold R.M. NephroTalk: communication tools to enhance patient-centered care. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):611–616. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VITAL Talk Transitions/Goals of Care. 2019. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/transitionsgoals-of-care/ Accessed April 23, 2021.

- 41.DePasquale N., Cabacungan A., Ephraim P.L., et al. I wish someone had told me that could happen": a thematic analysis of patients' unexpected experiences with end-stage kidney disease treatment. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(4):577–586. doi: 10.1177/2374373519872088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DePasquale N., Ephraim P.L., Ameling J., et al. Selecting renal replacement therapies: what do African American and non-African American patients and their families think others should know? A mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Hare A.M., Choi A.I., Bertenthal D., et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(10):2758–2765. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]