Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Cultural Safety is being prioritized within health care around the world. As a concept, Cultural Safety centers upon power relations between health providers and indigenous recipients of care, ensuring that all people feel safe and respected in the health care system. In this article, we explored the breadth of the literature regarding Cultural Safety within the context of indigenous kidney health care.

Study Design & Populations

As a systematic narrative review, this work engaged widely across a diverse range of the available literature to broaden understanding of Cultural Safety within indigenous kidney health care and indigenous populations from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

Search Strategy & Analytical Approach

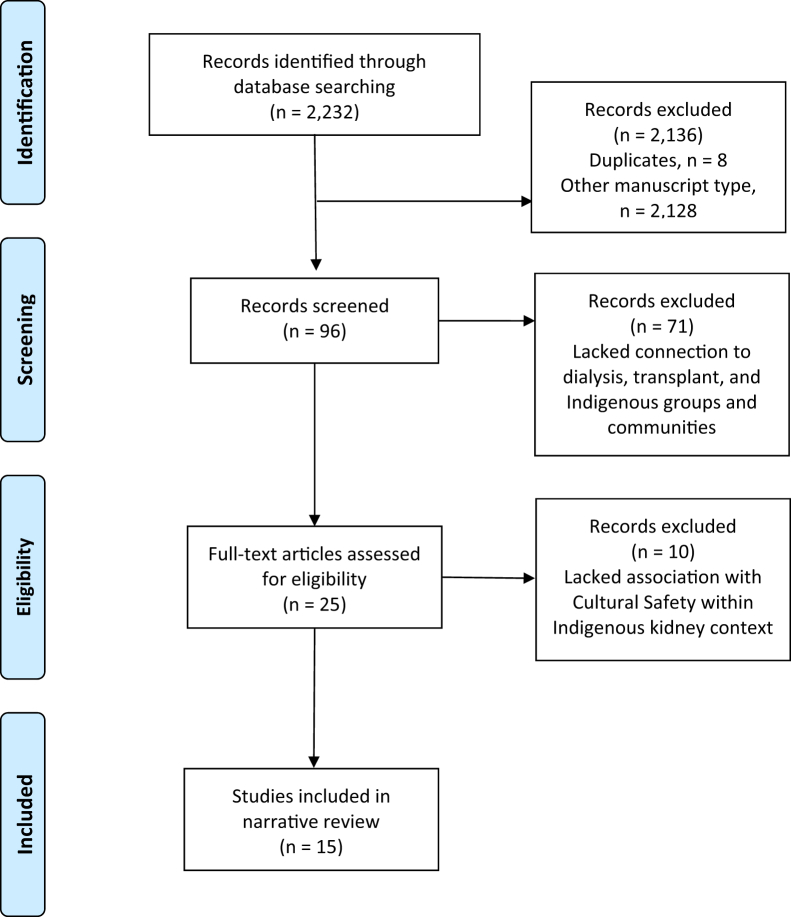

Guided by the research question focused on how Cultural Safety occurs within care for indigenous people with kidney disease, an initial database search by the university librarian resulted in retrieval of 2,232 articles, of which 96 potential articles were screened by the research team.

Results

15 articles relevant to the research question were identified and study findings were assembled within 3 broad clusters: relationality, engagement, and health care self-determination; systemic issues, barriers, and access; and addressing legacies of colonialism for health care providers.

Limitations

The review summarizes mainly qualitative articles given the paucity of articles found specific to Cultural Safety within indigenous contexts.

Conclusions

Of particular interest to health care providers are the collation of solutions by cluster and the findings of this review that contribute to further understanding of the concept of Cultural Safety in health care for indigenous people with kidney disease. Also, findings address the importance of community-driven kidney care in which language, ways of knowing and being, and traditional ways of healing are prioritized.

Index Words: Cultural safety, nursing, kidney, health care, indigenous

Plain-Language Summary.

This study identified various scientific papers that discussed Cultural Safety for indigenous people with kidney disease. In this review, a team of researchers within Canada explored published articles from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. The researchers wanted to discover how Cultural Safety happens in kidney health care. There is little research published on Cultural Safety in kidney care and we were able to locate 15 articles on this topic. We organized the articles that had similarities into 3 groups and then highlighted solutions aligning with community culturally based care. The results of our study should help improve the understanding of Cultural Safety for indigenous people with kidney disease and prioritize traditional ways of healing within community-driven care.

Editorial, p 881

During the 2020 pandemic year, the world witnessed an escalation of protests and media attention concerning racial incidents within health care. There has also been an increasing emphasis on the need for Cultural Safety∗ within mainstream health care in Canada.2, 3, 4 We begin here by describing the concept of Cultural Safety, its associated meanings, and its relevance to indigenous kidney health care and chronic kidney disease.

Many are familiar with the well-publicized case of Brian Sinclair, who, in 2008, died in a Winnipeg, Manitoba, emergency department while waiting 34 hours for care for a serious bladder infection.5,6 In their 2015 report, First peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada, Drs Billie Allan and Janet Smylie7 emphasize the embedded disparities within colonial policies that continue to severely impact on the provision of equitable health resources. Papps and Ramsden1 (1996) explain that Cultural Safety “raises the issue of racism” and race relations that may trigger unease for those in denial and for those who acknowledge it. In this regard, learning of Cultural Safety needs to be prioritized. The concept of Cultural Safety “pays explicit attention to power relations between service user and service provider”7(p3) and therefore differs from cultural competence and sensitivity that focus on a person’s culture. Cultural Safety cannot happen without cultural humility, which involves self-reflection and acknowledging one’s own lens.3

From Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, the meaning of Cultural Safety extends “...beyond the idea of cultural 'appropriateness' and demands the incorporation of services and processes that empower Indigenous Peoples.”8(p3) Cultural Safety demands the “inclusion of Indigenous languages, laws and protocols, determination, spirituality, and religion.”8(p173) In addition, the “concept of client-centred care and ‘getting to know the individual’ may not foster Cultural Safety for indigenous and racialized clients who understand relationships, knowledge, and space as interconnected manifestations of family and kinship-based societies.”9(p10) Relationships within community and to the land or relational ways of being and knowing are prioritized over individualism.1,3,7, 8, 9

Our team, including First Nation members, nursing scholars, and a nephrologist, is focused on improving indigenous† kidney health throughout Canada. As an eclectic research team, we attempted to identify what already exists in terms of Cultural Safety for indigenous populations with kidney disease in Canada and internationally from a variety of sources. Our research specifically sought to understand and address how Cultural Safety occurs within contexts of health care for indigenous people with kidney disease.

Methods

The narrative review systematically incorporates a broad spectrum of literature and facilitates an evidence synthesis and interpretation that is both holistic and reflective of the unique insights and experiences of reviewers.10,11 Narrative reviews “provide interpretation and critique; their key contribution is deepening understanding."12(p2) In addition, this type of review fosters clarification and insight as relevant to philosophy and history.12 Cultural Safety is a concept that links to the historical legacy of colonialism and indigenous epistemologies and is favorable to a narrative review. This work comprehensively synthesizes peer-reviewed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed research studies and reviews toward offering rich and diverse perspectives.

Based on our research question, how Cultural Safety occurs within contexts of care for indigenous people with kidney disease, the following databases were searched by a librarian with experience in systematic reviews (ARW): Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) on the Ebsco platform, Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane CENTRAL on the Ovid platform, ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health Database, and Web of Science Core Collection (including Science Citation Index: 1900-present; Social Sciences Citation Index: 1956-present; and Arts and Humanities:1975-present).

The search strategy included a search filter for indigenous literature developed by the University of Alberta, as well as search strategy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander literature developed by the Lowitja Institute. Key terms were also searched in Google Scholar. A full search strategy for the Medline database is available at http://hdl.handle.net/1974/28582. We identified 2,232 records through the database searches for screening after duplicates were removed.

Inclusion criteria encompassed Cultural Safety concepts within the context of indigenous kidney care, including race relations, the legacy of colonialism, self-determination and land, indigenous ways of knowing and being, language, and relationality.9,13,14 Articles between 2002 and 2020 were chosen. The date of 2002 correlates with the time that Irihapeti Merenia Ramsden15 published her thesis titled Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu in which the term then began to be used more widely in the literature. Excluded records lacked association with Cultural Safety within indigenous kidney contexts and connection to chronic kidney disease, dialysis, and/or transplantation. This resulted in 96 potential articles for full-text screening by our research team. Both indigenous and nonindigenous members of the research team engaged in feedback on the chosen articles that were distributed through secure online collaborative sites and discussed during research team meetings.

Results

Fifteen studies met the criteria of Cultural Safety within indigenous kidney care and were included in this review (Fig 1).16 We found articles both from Canada and internationally that encompassed Cultural Safety concepts within the context of indigenous kidney care (Table 117, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). Most studies were published between 2014 and 2020. There were 10 qualitative studies, 2 quantitative studies, and 3 reviews, 1 scoping and 2 systematic. Although there are shared commonalities across all the articles, we arranged the research findings into 3 clusters aligned with Cultural Safety concepts. Clusters were determined through reading and re-reading articles and discussing their relevance to the research question within online team meetings and shared emails that involved both indigenous and nonindigenous research team members. The clusters include relationality, engagement and health care self-determination; systemic issues, barriers, and access; and addressing legacies of colonialism for health care providers. Solutions per cluster are represented in Box 1.17, 18, 19, 20, 21,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 There were 6 articles clustered under the heading of relationality, engagement, and health care self-determination: 4 articles in relation to systemic issues, barriers, and access; and 5 articles related to addressing legacies of colonialism for health care providers.

Figure 1.

Flow chart. Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.16

Table 1.

Publications Relevant to Cultural Safety Concepts Within the Context of Indigenous Kidney Care

| Reference, Country | Research Question(s) or Purpose/Objectives | Research Design/Methods | Participants | Results and Connection to Cultural Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richels et al17 (2020), Canada | Identify existing barriers to home peritoneal dialysis; provide insight for a culturally meaningful framework for future programs in First Nations communities in Saskatchewan | Qualitative research - sharing circles, individual interviews | 67 participants in sharing circles | Themes included: logistics, education and information, training and support, community support, and culture and leadership; notes underuse of home-based peritoneal dialysis |

| Jansen et al19 (2020), Canada | Identify culturally appropriate and co-developed indigenous educational tools to support CKD learning and end-stage kidney treatment decision making | Scoping review | 1 article; CKD tool co-developed by researchers | Engaging with indigenous communities requires in-depth understanding; the co-development of indigenous CKD educational tools is lacking |

| Hughes et al18 (2019), Australia | Describe health care experiences in relation to a government’s kidney health care | Qualitative interviews | 26 adults | Acknowledges land and self-determination concepts; identifies complaint of lack of respect and empathy from health care providers; addresses needs to further health care quality |

| Walker et al21 (2019), New Zealand | Identify systemic barriers and understanding of cultural values that influence kidney transplantation | A systematic review of qualitative studies | 225 indigenous participants in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States | Related to indigenous ways of knowing and being; identified barriers include distrust of health care systems, lack of knowledge of kidney transplantation processes, and discrimination; among indigenous participants, access to kidney transplantation was strongly desired |

| Conway et al23 (2018), Australia | Examine impact of mobile dialysis on health and well-being; facilitators and barriers | Semi-structured interviews | 15 indigenous dialysis patients and 10 nurses | Country reference similar to a family bond, tradition, links with ownership and spirituality |

| Nelson et al20 (2018), United States | Examine efficacy of a home-based kidney care program | Clinical trail | 98 rural adult Zuni Indians | A home-based intervention improved activation in own health and health care and may reduce CKD risk factors for disadvantaged rural area; interventions through community members who are trained furthered the educational process and helped engage patients in own care |

| Rix et al28 (2016), Australia | Aim to inform service improvement for Aboriginal kidney patients | Qualitative research; community-based research | 18 Aboriginal hemodialysis patients and 29 kidney health professionals | Related to indigenous ways of being and knowing; land/self-determination colonialism; relationality; Cultural Safety requires listening to what people are saying |

| Reilly et al24 (2016), Australia, New Zealand, Canada | Examine benefits, cost-effectiveness, and suitability of CKD management programs for indigenous people, in addition to enablers and barriers | Systematic review of mixed evidence | 10 studies were included | Describes the challenge of recruiting and retaining staff in remote communities, need for indigenous decision making, respect, ownership and health care workers |

| Kelly et al29 (2016), Australia | Develop a more responsive education program | Participatory action research | Kidney focus group of kidney and health care professionals | Related to knowledge of history/colonialism; humility and safety to be reflected through case studies; emphasis on indigenous Culturally Safe care |

| Walker et al22 (2012), New Zealand | Describe and discuss what predialysis nurses perceive to be key influences on effective predialysis nursing care | A descriptive exploratory approach | 11 interviews with 11 nurses | Important to provide culturally appropriate and effective care; lack of culturally diverse educational resources identified as barrier to providing effective care; the Western approach of focusing on individuals is not always effective in this population |

| Rix et al27 (2014), Australia | Inform the provision of health care services as depicted by the indigenous people themselves | Qualitative stories | 5 indigenous participants | Exemplifies Cultural Safety, uses storying, reflection on colonial historical past, unequal power relationships and indigenous ways of being and knowing within a kidney context |

| Shah et al25 (2014), United States | Identify barriers to health care in the Zuni Pueblo | 14 one-hour focus group sessions | 112 people | Recommends implementation of culturally community-based health promotion programs and preventive screening to improve access and reduce disparities |

| Walton30 (2011), United States | Describe differences regarding cultural knowledge and awareness in students before and after receiving education re indigenous experiences with hemodialysis therapy by a nephrology nurse; examine how students apply culturally relevant care when given a case scenario with CKD | Quantitative -pre- and post-tests based on 1-h presentation and qualitative-reflective paper | N = 95 nursing students | Indigenous ways of knowing and being are discussed; “Storytelling, networking, and involvement of Native American leaders, and the creation of new models that integrate cultural traditions in care may be keys to bridging the cultural gaps that exist”(p27) |

| Sicotte26 (2011), Canada | Compares health and care use of patients receiving tele-hemodialysis services | Pre-post design | N = 19 | Telemedicine reduces the burden associated with access for hemodialysis |

| Walton30 (2011), United States | Explore what spirituality means to individuals receiving hemodialysis. and spirituality’s influence on their lives | Grounded theory | N = 21; 12 women and 9 men | Focus on spirituality, traditional approaches, consideration and recommendations for developing and transitioning into hemodialysis; also explores ways to decrease depression, reconcile past issues and further relationships |

Abbreviation: CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Box 1. Identifying Solutions by Cluster.

Relationality, engagement and health care self-determination

-

•

Incorporation of translators, traditional approaches, Elders, peer support attention to funding and advocacy17

-

•

Individualized education17

-

•

Support for caregivers17

- •

-

•

Sharing stories that voice ways of knowing and being inclusive of indigenous art 17, 18, 19

-

•

Cultural Safety audits and continuity of service18

-

•

Home-based care using local culturally consistent and community-based resources and personnel17, 18, 19, 20

-

•

Build trust through traditional ways to foster kidney organ donation and transplantation21

-

•

Culturally appropriate social workers and cultural support personnel; promotion of indigenous kidney nursing20

-

•

Indigenous engagement within health care education and administrative and organizational systems sectors20

Systemic issues, barriers, and access

-

•

Recognition of significance of land and cultural attachments to place of origin21

-

•

Dialysis service and kidney care in home remote communities25

-

•

Increase indigenous health workers and capacity for involvement in decision making21

-

•

Supporting community ownership furthers engagement in health prevention24

-

•

Reliable transportation to medical facilities and pharmacies25

-

•

Tele-hemodialysis reduced the burden associated with travel and the requirement for on-site health care providers that historically have had a high turnover rate26

Addressing legacies of colonialism for health care providers

-

•

Self-reflective journey through journaling as a way to address harmful assumptions and sterotyping27

-

•

Intensive listening conveys respect for both cultural or traditional worldviews28

-

•

Having indigenous health workers within dialysis units28

-

•

Paid Elders inclusive of family/community for cultural training of nonindigenous health workers28

-

•

Include case studies relating to patient journeys in health care education29

-

•

Need for ongoing indigenous involvement in reviewing the overall course and framework29

-

•

Respect for smudging supporting use of meaningful symbols in prayer in dialysis care31

-

•

Approaching with an open mind; establishing trust and a sacred space; assessing belief systems; ongoing education for the patient30

Relationality, Engagement, and Health Care Self-determination

The publication by Richels et al17 addresses barriers to home peritoneal dialysis through a qualitative study involving sharing circles and interviews with First Nation communities from Saskatchewan. With regard to Cultural Safety, participants spoke about mistrust arising from colonization and systemic racism that ignored traditional healing, as well as differing treatment based on race. Solutions brought forward by the participants included incorporation of translators, traditional approaches, Elders, peer support, and attention to funding and advocacy. The need for individualized education and support for caregivers was further highlighted.17

Similarly, a qualitative study by Hughes et al18 and a scoping review from Jansen et al19 emphasized community relational strengths and included supporting, assisting each other, and learning from and listening to Elders. These studies and another study by Nelson et al20 also identified a need for resources beyond written format that are inclusive of local language, traditional protocols, and ceremonies developed by communities themselves.18, 19, 20 For example, audiovisual stories that voice ways of knowing and being and are inclusive of art, are creative opportunities in which communities could take ownership and be highly engaged. Hughes et al18 additionally stressed the need for Cultural Safety audits and continuity of service in situations in which health care providers were noted to lack attention to privacy and often spoke in a highly alienating manner using complex medical language.

Nelson et al20 further addressed the effectiveness of a home-based kidney education program for the Zuni Pueblo, an indigenous people located in New Mexico, United States, that was delivered by community health representatives. The randomized clinical trial study assessed the effectiveness of home-based learning and treatment interventions developed in conjunction with the Tribal Advisory Panel and cultural protocols. Community health representatives, members of the Zuni Tribe who spoke Zuni, provided home visits and blood testing with results directly in the home. The community health representatives also sent positive health messages to participants by text. In addition, consultations occurred monthly through telemedicine with physicians and other service providers. Similarly to the articles by Richels et al,17 Hughes et al,18 and Jansen et al,19 the study by Nelson et al20 highlights how home-based care using local culturally consistent resources can improve treatment adherence and quality of life.

Walker et al21 completed a systematic review of qualitative studies related to indigenous experiences, perspectives, and values regarding kidney transplantation with participants from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. A recurring theme that is shared with the articles by Richels et al,17 Hughes et al,18 and Jansen et al19 was the lack of patient engagement in kidney health care decision making, including prioritizing transplantation. Moreover, the review highlights issues with trust within the health care system and the need to incorporate traditional ways to foster kidney organ donation and transplantation. Overall, the need to further Cultural Safety and eliminate ignorance and prejudice was a finding shared by Richels et al,17 Hughes et al,18 and Jansen et al.19

Another study conducted by Walker et al22 in 2012 involved 11 New Zealand nurses in telephone interviews concerning effective predialysis care. The qualitative research related mainly to the indigenous population, which is significantly overrepresented in those requiring kidney replacement therapy. Four themes emerged from the interviews revolving around time, culturally specific care, health care team relationships, and issues within nursing practice. As apparent in the publications by Richels et al17 and Hughes et al,18 the need for interpreters and culturally appropriate and indigenous-specific resources was pinpointed. Further, there were recommendations for “having cultural input into changes in health service systems; nurses having better access to and engagement with culturally appropriate social workers and cultural support personnel; and the promotion of kidney nursing to Ma ¯ori and Pacific students.”22(p31) The study also emphasizes the need for increased and consistent indigenous engagement within all sectors related to kidney care, including health care education and administrative and organizational systems.

Systemic Issues, Barriers, and Access

Conway et al23 offered insights into the perspectives of indigenous people and staff who are involved with hemodialysis occurring on a mobile bus that travels to remote areas of Australia. The qualitative study expressed the pivotal significance of land and cultural attachments to place of origin for indigenous people. Globally, indigenous people are frequently required to travel vast distances for dialysis and are often even required to relocate. Such detachments from family, community, and place result in adverse consequences related to grief and loss.23 Being separated from country often means the loss of elders for community, which is critical to cultural continuance. Elders are critical to a community healing from a traumatic history; they provide a sense of identity and maintain relationality. Conway et al23 further demonstrated that when elders receive dialysis at home, the community is strengthened because well-being through traditional practices is sustained and shared with the younger generations. With closer proximity to home, relationships with health care staff improved. Health care providers working in remote areas became more attuned to the relevance of cultural traditions to community well-being and the necessity of accessible care for overall community health.23

Reilly et al24 performed a systematic review concerning clinical evidence of chronic kidney disease programs for indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. Components of these programs included embedding Cultural Safety through indigenous health workers within primary care services, addressing accessibility and continuity of care, furthering education consistent with maintaining local culture, and community ownership of programs. The article pointed to the high turnover of health care providers as more problematic than a lack of overall funds. Despite having sufficient funding, the continuum of care is adversely affected by the inability to retain health care providers. A solution proposed was to expand the number of indigenous health workers and increase capacity for their involvement in decision making. Supporting community ownership of health was connected to improving prevention activities that ultimately can reduce the burden of chronic diseases and associated costs.24

The high turnover rate of health care providers, with concerns regarding confidentiality and embarrassment, as well as difficulties accessing medical care that required expensive transportation, were also discussed by Shah et al.25 This study investigated barriers to health care for people of the Zuni Pueblo, an indigenous people located in New Mexico. Community health representatives, trusted members of the community, were involved in focus groups. In close knit communities, members often had difficulty keeping their health conditions personal. For example, when attending public health events related to managing obesity, members risked criticism and unwanted attention to personal issues by others in the community. This attention could also foster self-guilt as being the cause of one’s illness. Relationships with health care providers were adversely affected by high turnover rates of providers and having to start again with explaining personal histories. Difficulties securing reliable transportation to medical facilities and pharmacies were also noted for those without cars or lacking support for transportation.25

Sicotte et al26 described the provision of tele-hemodialysis services in 2 James Bay Cree communities in Canada through a quantitative pre-post study design involving 19 participants requiring hemodialysis. The telemedicine component allowed ongoing care and monitoring between health care providers and nephrologists with the person needing dialysis. The study found that tele-hemodialysis support reduced the burden associated with travel and the requirement for onsite health care providers that historically have had a high turnover rate. The authors recommended a qualitative study to determine the social and quality-of-life impacts for the recipients of care. This study highlighted tele-hemodialysis as an innovative solution with the potential to alleviate the issue of accessibility, transportation, and high staff turnover rates.26

Addressing Legacies of Colonialism for Health Care Providers

A study by Rix et al27 asserted a Culturally Safe approach in which storying was prioritized and indigenous people themselves directed their own health care. The article further addressed victim blaming and racism through “relational accountability that incorporates respect, responsibility and reciprocity.”27(p2) The authors described a self-reflective journey through journaling that can expose harmful assumptions and stereotypes aligned with a Eurocentric system. Another qualitative study by Rix et al28 explained that Cultural Safety “will require more than just talk; it needs intensive listening and taking on board what Aboriginal people are saying.”28(p15) Their recommendation was for indigenous people from the community to be closely involved in kidney health care and education for mainstream health care providers. Focusing on to 2-way understanding strengthened relationships and encouraged respect for cultural or traditional worldviews as distinguished from mainstream approaches. This occurred by having indigenous health workers within dialysis units to provide an important cultural connection and presence for indigenous people receiving dialysis. Two-way understanding extended to having paid Elders involved in cultural training of nonindigenous health workers and including family members.28

Kelly et al29 described a collaborative activity involving nurses who revised a kidney course designed for nurses who care for indigenous people in Australia. Case studies of patient journeys were anonymized and used by experienced nurses to illustrate culturally appropriate care to student nurses. Expert nurses were aligned with Cultural Safety as conceptualized within Benner’s32 model of competence stages. Cultural humility and Cultural Safety concepts were also distinguished. Cultural humility was defined as aligning with patient as expert and with self-reflection within an interpretative realm whereas Cultural Safety is aligned with “a critical social justice/equity/social determinants of health framework.”29(p110) Although the case studies stemmed from indigenous experiences, the study addressed the need for ongoing indigenous involvement in reviewing the overall course and its framework.

Walton31 used grounded theory to address spirituality through narratives and stories from 21 indigenous people in the context of dialysis care. From the narratives, the 4 themes of Honoring Spirit, Healing Old Wounds, Connecting With Community, and Suffering were conceptualized as a Sacred Circle model with approaches suggested for staff or health care providers. The themes were reflective of Cultural Safety concepts that prioritize ways of knowing and being. Honoring Spirit involves identifying and respecting religious or traditional practices and beliefs, smudging within the care unit, and supporting the use of meaningful items or symbols in prayer while receiving dialysis care. In Healing Old Wounds and Connecting With Community, the emphasis was on listening and sharing stories, expressing emotions respectfully and supporting traditions of prayer and family gatherings, and inquiring about relations and community. In Suffering, the recommendations included fostering dialysis education respectful of cultural ways, including family and community. Walton31 explained that participants went through phases of suffering, including asking why they had to become sick, experiencing periods of illness, repelling dialysis, debating between choices of life or death, praying for health, and persevering through dialysis for family. Providing comfort through traditional approaches was important to participants within dialysis units.

Another related study by Walton30 linked partnerships between nephrology and academic centers with furthering cultural care. A 1-hour presentation describing the Sacred Circle Model was followed by completing a critical reflection of a case study. Pre-post surveys identified changes in attitudes and beliefs for students who participated. Qualitative analysis of post surveys identified themes that included “approaching the patient with an open mind; developing trust; assessing beliefs, culture, and knowledge; educating and re-educating with patient and family; convincing the patient to have dialysis; and creating a sacred space.”30(p21) Some of the study outcomes included furthering open mindedness, trust building, and striving to understand beliefs. The aforementioned articles and the research by Walton suggest the need not only for approaches to promote supportive and respectful care, but also for education of health care providers that is consistent with indigenous ways of being and knowing.27, 28, 29, 30, 31

Discussion

Culture Safety requires a lens that genuinely reflects on the relationship and balance of power between care providers and recipients. In this regard, most articles in this review identified the need to build trust within indigenous kidney care in the 4 countries of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. The articles included for this review were pertinent to the focus of Cultural Safety within indigenous kidney care. Overall, there was a paucity of articles that addressed the research question.

The publications by Richels et al,17 Hughes et al,18 Jansen et al,19 Nelson et al,20 and Walker et al21,22 were consistent with the concept of Cultural Safety within kidney care and expressed relationality, engagement, and health care self-determination. Relationality and engagement were critical to health and well-being; these emerged as a community strength significant to those in need of dialysis care. Having the family and community close by and involved in shaping the care to be provided was vital to respectful care.17, 18, 19, 20 Specific to health care determination were the articles by Hughes et al,18 Richels et al,17 and Walker et al21,22 in which participants expressed that it was crucial that they, in addition to family members and communities, be more involved in decision making. For example, the systematic review by Walker et al21 supported the acceptability of kidney transplantation; however, there were concerns when the subject of transplantation remained elusive within discussions with health care providers. Community engagement and health care self-determination also became apparent as a way to further trust. This was evident in the articles by Nelson et al19 and Walker et al,22 who highlighted the need for indigenous health workers who were familiar with the community’s language and culture to support community-based kidney care. Systemic issues, barriers, and access are reflected within the articles by Conway et al,23 Reilly et al,24 Shah et al,25 and Sicotte et al.26 Accessibility issues overlap with continuity of care in which indigenous communities struggled to maintain a stable workforce of health care providers necessary to the provision of kidney care.24,25 Innovative ways to improve accessibility to remote dialysis included a mobile dialysis unit and tele-hemodialysis.23,26 The benefits of community ownership of care were emphasized in these articles, as well as care provided by fellow community members familiar with language and ways of being.23, 24, 25, 26

The studies within the cluster addressing legacies of colonialism for health care providers speak to the critical necessity for health care providers to learn indigenous ways of being and knowing as provided by elders, indigenous persons with kidney disease, their families, and communities themselves.27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Health care providers may benefit from journaling and case studies to allow a deeper understanding and appreciation of how colonialism has shaped health care for indigenous people.27,28 Another recommendation essential to trust building was the need to listen to those with kidney disease within comforting surroundings that afford respectful listening and privacy.29 Accommodating cultural traditions within dialysis units builds trust and exemplifies respect. At the same time, it is important to not assume that all indigenous people have the same belief system.31

A narrative review methodology with a systematic database search was chosen given the dearth of articles and the broad focus related to the term Culturally Safe care specific to kidney disease within indigenous contexts. Although there was a multitude of records related to culture, it was a challenge to garner those specific to our focus. To glean meanings from the existing literature on Cultural Safety and kidney disease required a flexible approach toward the literature. Given that we included a variety of articles including qualitative studies, the assessment for methodological rigor or quality of the studies was limited to consideration of the quality of the journal and whether it was peer reviewed.

Although Cultural Safety is a term that has been in the literature for some time and is increasingly being referred to, particularly in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, its expression within kidney care still requires further understanding and delineation. The studies involved in this narrative review solidify that indigenous-determined care and engagement is critical toward improving kidney health outcomes. A multifaceted effort is required to support the recruitment of indigenous students and health care workers. Kidney educational programs require health care providers to engage in learning about systemic racism and the legacy of colonialism. Additionally, indigenous health workers and social workers need to be involved in decision making and advocating for those needing kidney replacement therapy or transplantation. Indigenous persons with kidney disease, their families, elders, and community groups can also participate in enhancing and creating tools with mainstream providers for kidney care and kidney disease prevention. Given the overall burden of kidney disease, it is important to fund and support indigenous community members and mainstream health care providers in designing kidney care programs together that instill language and traditional protocols into accessible Culturally Safe care. In addition, there is a need for ongoing indigenous research that evaluates and sustains Culturally Safe indigenous kidney care and chronic disease prevention programs. It is critical that health care authorities engage communities and care recipients in decision making, provide a respectful time and space to listen, and enable indigenous-driven traditional protocols and approaches within highly technical dialysis units and nephrology services.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Mary Smith, PhD, NP-PHC, Vanessa Silva e Silva, PhD, Kara Schick-Makaroff, PhD, MN, RN, Joanne Kappel, MD, FRCPC, Jovina Concepcion Bachynski, MN, RN(EC), CNeph(C), Valerie Monague, MSW, Geneviève C. Paré, MSc, and Amanda Ross-White, MLIS, AHIP.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: MS, VSS, KSM, GCP, JK ARW, VM, JCB; data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation: MS, VSS, KSM, GCP, JK ARW, JCB, VM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This work was made possible by the Kidney Foundation of Canada’s Allied Health Research Grant [KFOC190024].

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Kidney Foundation of Canada in making this review possible.

Peer Review

Received January 22, 2021. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input by the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form April 25, 2021.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

The term, Cultural Safety, is to be capitalized as it emphasizes the position of power that the health care provider holds, with the need for the recipient of care to determine what approach to care is safe for them.1

The term indigenous is supported by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It is used interchangeably in this article to refer to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples in Canada.

References

- 1.Papps E., Ramsden I. Cultural Safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8(5):491–497. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (IPAC-RCPSC) Promoting culturally safe care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Patients: A core curriculum for residents and physicians. https://www.ipac-amac.ca/downloads/core-curriculum.pdf Published 2009. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 3.First Nations Health Authority #itstartswithme: FNHA’s policy statement on cultural safety and humility. https://www.fnha.ca/documents/fnha-policy-statement-cultural-and-safety-and-humility.pdf Published 2016. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 4.Horrill T. (2020). Cultural safety: are we on the same page? Canadian Nurse. https://www.canadian-nurse.com/en/articles/issues/2020/february-2020/cultural-safety-are-we-on-the-same-page Published February 18, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- 5.Brian Sinclair Working Group Out of sight. https://libguides.lib.umanitoba.ca/ld.php?content_id=33973085 Published September 2017. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 6.Puxley C. Brian Sinclair inquest told aboriginals face racism in ERs. The Canadian Press. Published June 10, 2014 June. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/brian-sinclair-inquest-told-aboriginals-face-racism-in-ers-1.2670990 Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 7.Allan B., Smylie J. First peoples, second class treatments: the role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. https://www.sac-oac.ca/sites/default/files/resources/Report-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment.pdf Published 2015. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 8.National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls: Reclaiming power and place: the final report of the National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/ Published June 3, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 9.Churchill M.E., Smylie J.K., Wolfe S.H., Bourgeois C., Moeller H., Firestone M. Conceptualising cultural safety at an Indigenous-focused midwifery practice in Toronto, Canada: qualitative interviews with Indigenous and non-Indigenous clients. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon-Woods M., Agarwal S., Jones D., Young B., Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mays N., Pope C., Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T., Thorne S., Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(6) doi: 10.1111/eci.12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerlach A.J. A critical reflection on the concept of cultural safety. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79(3):151–158. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung S. Conceptualizing cultural safety. Journal for Social Thought. 2016;1(1) https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/jst/article/view/498 Accessed November 21, 2020.

- 15.Ramsden I. Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [dissertation]. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University; 2005 (doctoral dissertation) https://croakey.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/RAMSDEN-I-Cultural-Safety_Full.pdf Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 16.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richels L., Sutherland W., Prettyshield K., Kappel J., McCarron M., Richardson B. Community-based dialysis in Saskatchewan First Nations: a grassroots approach to gaining insight and perspective from First Nations patients with chronic kidney disease. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7 doi: 10.1177/2054358120914689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes J.T., Freeman N., Beaton B., et al. My experiences with kidney care: a qualitative study of adults in the Northern Territory of Australia living with chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. PLoS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansen L., Maina G., Horsburgh B., et al. Co-developed indigenous educational materials for chronic kidney disease: a scoping review. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7 doi: 10.1177/2054358120916394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson R.G., Pankratz V.S., Ghahate D.M., Bobelu J., Faber T., Shah V.O. Home-based kidney care, patient activation, and risk factors for CKD progression in Zuni Indians: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(12):1801–1809. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06910618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker R.C., Abel S., Reynolds A., et al. Experiences, perspectives and values of Indigenous peoples regarding kidney transplantation: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:204. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1115-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker R., Abel S., Meyer A. Perceptions of key influences on effective pre-dialysis nursing care. Contemp Nurse. 2012;42(1):28–35. doi: 10.5172/conu.2012.42.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conway J., Lawn S., Crail S., McDonald S. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the Country Health SA Dialysis bus. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1010–1013. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3849-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly R., Evans K., Gomersall J., et al. Effectiveness, cost effectiveness, acceptability and implementation barriers/enablers of chronic kidney disease management programs for Indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand and Canada: a systematic review of mixed evidence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:119. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah V.O., Ghahate D.M., Bobelu J., et al. Identifying barriers to healthcare to reduce health disparity in Zuni Indians using focus group conducted by community health workers. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7(1):6–11. doi: 10.1111/cts.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sicotte C., Moqadem K., Vasilevsky M., Desrochers J., St-Gelais M. Use of telemedicine for haemodialysis in very remote areas: the Canadian First Nations. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(3):146–149. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rix E.F., Barclay L., Wilson S. Can a white nurse get it? 'Reflexive practice' and the non-Indigenous clinician/researcher working with Aboriginal people. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(2):2679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rix E., Moran C., Kapeen R., Wilson S. Building cultural bridges and two-way understanding: working with Australian Aboriginal people within mainstream renal services. Renal Society of Australasia Journal. 2016;12(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly J., Wilden C., Chamney M., Martin G., Herman K., Russell C. Improving cultural and clinical competency and safety of renal nurse education. Renal Society of Australasia Journal. 2016;12(3):106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walton J. Can a one-hour presentation make an impact on cultural awareness? Nephrol Nurs J. 2011;38(1):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walton J. Prayer warriors: a grounded theory study of American Indians receiving hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2007;34(4):377–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]