Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to characterize the use and impact of assessments of understanding in parent-clinician communication for critically ill infants.

Methods:

We enrolled parents and clinicians participating in family conferences for infants with neurologic conditions. Family conferences were audio recorded as they occurred. We used a directed content analysis approach to identify clinician assessments of understanding and parent responses to those assessments. Assessments were classified based on an adapted framework; responses were characterized as “absent,” “yes/no,” or “elaborated.”

Results:

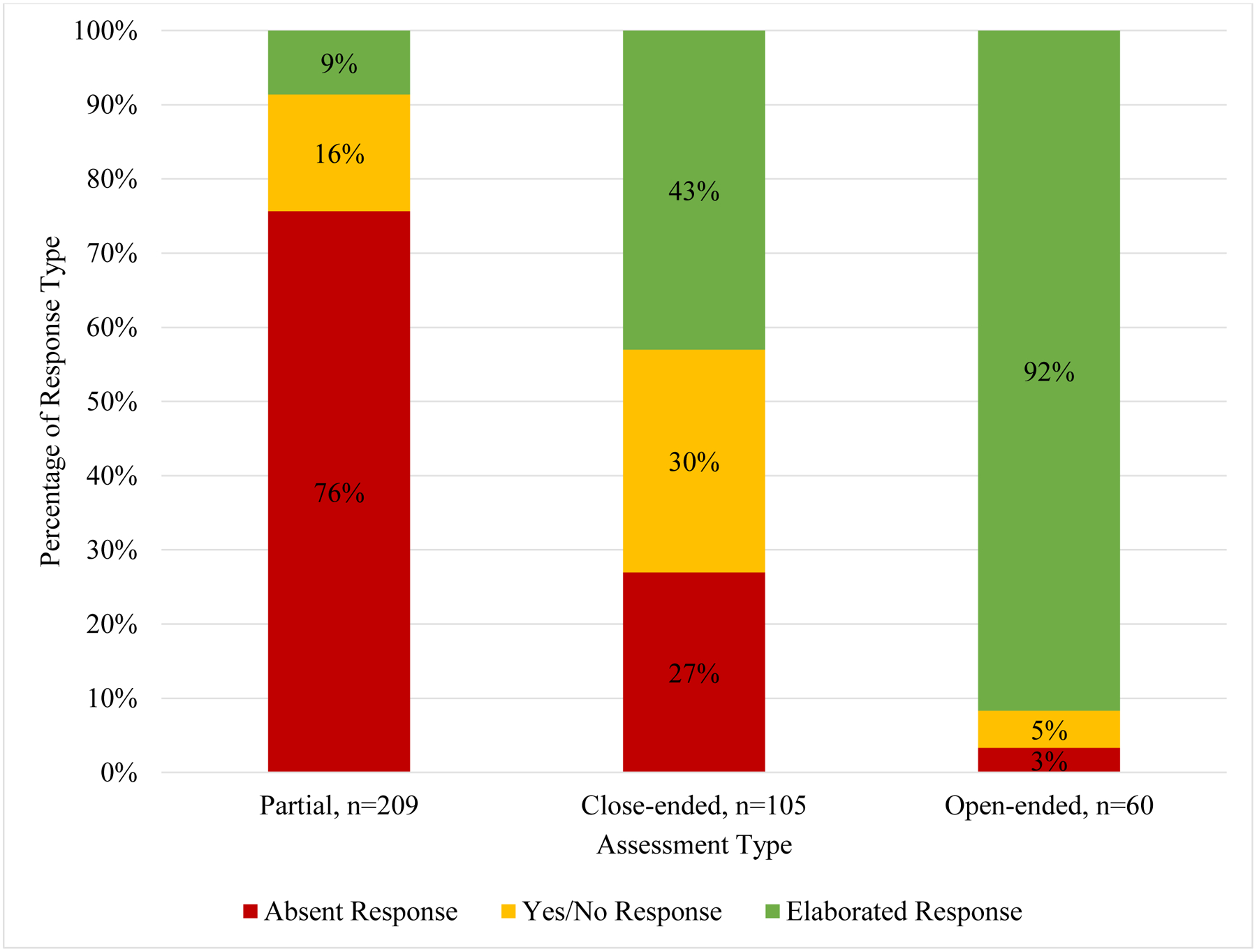

Fifty conferences involving the care of 25 infants were analyzed; these contained 374 distinct assessments of understanding. Most (n=209/374, 56%) assessments were partial (i.e. okay?); a minority (n=60/374, 16%) were open-ended. When clinicians asked open-ended questions, parents elaborated in their answers most of the time (n=55/60, 92%). Approximately three-quarter of partial assessments yielded no verbal response from parents. No conferences included a teach-back.

Conclusions:

Although common, most clinician assessments of understanding were partial or close-ended and rarely resulted in elaborated responses from parents. Open-ended assessments are an effective, underutilized strategy to increase parent engagement and clinician awareness of information needs.

Practice implications:

Clinicians hoping to facilitate parent engagement and question-asking should rely on open-ended statements to assess understanding.

1. Introduction

Clinicians and parents caring for infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) face high-stakes decisions about care. These decisions are often informed by complex information about the infant’s medical course, prognosis, and treatment options [1,2]. Relaying complex health information is challenging; these challenges are amplified in the NICU setting, where parents may be recovering from a traumatic birth experience and may not have previous experience making medical decisions [2–6].

Given the large amount of information parents must understand to make good decisions, the way in which information is presented is critical. For example, because the average U.S. adult reads at an eighth-grade level, the American Medical Association recommends that patient education materials be crafted at or below a 6th-8th grade reading level [7–10]. In addition, multiple professional organizations encourage clinicians to avoid jargon, focus on only three main points per encounter, speak slowly, and use visual aids to optimize comprehension [11,12]. Some studies have also suggested that providing families a question-prompt list to use with clinicians can facilitate question-asking and improve their understanding of medical information [13,14]. Clinicians can also periodically assess understanding to ensure that parents comprehend key information [15–18]. These assessments can come in a variety of forms [16–18]. A teach-back, typically considered the most robust assessment, occurs when clinicians ask patients to restate new medical information using their own words [18]. Other assessments of understanding include close- and open-ended questions that allow patients to ask questions or share their values and concerns with the medical team [18]. Whether and how to incorporate assessments of understanding in the intensive care setting and in the context of delivering complex, emotion-laden information is not known.

Existing data show that quality assessments of understanding improve patient understanding and retention of complex medical information, engage them in conversations about their care, and encourage question-asking [16–21]. The use of the teach-back method with NICU parents at discharge has been shown to improve caregiver retention and adherence to home care regimens [16–20,22]. However, doing a teach-back after relaying serious, emotion-laden news (e.g., your child likely will never walk) might not be the best technique in this context. Assessments of understanding also provide clinicians with real-time feedback on the clarity of their communication and can serve as a cue to revisit key information [16–18,22,23]. Yet, existing data suggest that clinicians do not frequently assess patient understanding; when clinicians do, they rarely use effective strategies [16,17,21,24–27]. Furthermore, some studies report that clinicians’ awareness of effective assessments during clinical encounters is poor; clinicians often overestimate their use of strategies to check patient comprehension of medical information [21,24].

Although parents rely on their knowledge of medical information to make treatment decisions for their child, how clinicians assess parent understanding during actual clinical encounters is unclear; and, to our knowledge, no investigators have assessed the frequency, type, and impact of assessments of understanding in the NICU setting. Clinician awareness and application of appropriate strategies to assess parent understanding may be critical to delivering goal-concordant care in this setting; here, we aimed to characterize the use and impact of assessments of understanding in family conferences for critically ill infants.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

This secondary analysis includes a convenience sample of family conferences from an audio-repository of clinical encounters between parents of critically ill infants and their medical team [13]. Inclusion criteria included 1) the presence of any neurologic condition, 2) a planned family conference, and 3) parent ability to understand and speak English. Meeting participants were chosen by the patient’s family and clinical team. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

2.2. Study Procedures

Data used for this secondary analysis were collected as part of two studies of parent-clinician communication that were completed between 2017–2020. The majority of conference transcripts were collected as part of a longitudinal observational study of communication and decision making for infants with neurologic conditions. A minority of conference transcripts (n=8) were collected as part of a study characterizing the use and acceptability of a question prompt list for parents of critically ill infants [13]. We reviewed infant charts for demographic and clinical information. Parents completed baseline surveys targeting demographic information. Family meetings between clinicians and parents of enrolled infants were audio recorded by a study team member. Audio recordings were transcribed and de-identified.

2.3. Data Analysis

We used a directed content analysis approach to analyze conference data [28]. We refined a codebook based on an existing framework first developed by Farrell and Kuruvilla to characterize four types of assessments of understanding and identify these assessments in transcripts of simulated clinical encounters [16,18]. (Table 1) Parent responses to assessments of understanding were identified and characterized as: 1) “absent,” indicating no response, 2) “yes/no,” indicating a “yes” or “no” response, or 3) “elaborated,” indicating all other responses.

Table 1:

| AU Type | Interrater reliability (kappa) | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Partial (ineffective) | 0.84 | Ambiguous phrases that do not clearly assess comprehension and often do not invite a response. These phrases could be interpreted as an assessment of understanding or as permission for the clinician to continue speaking. | Okay? |

| 2. Close-ended (less effective) | 0.80 | The clinician asks parents if they have questions. This often limits responses to “yes” or “no”. Close-ended assessments allow for, but do not encourage, question-asking. | Do you have any questions? |

| 3. Open-ended (effective) | 0.80 | The clinician asks parents what questions they have. This places no restriction on responses and encourages question-asking. | What questions do you have? |

| 4. Request for Teach-Back (most effective) | 1.00 | The clinician asks parents to explain, or “teach”, information back to them using their own words. Thought to be the most effective assessment, as it explicitly tests the parents’ degree of comprehension. | I’m not sure I explained that well to you. Can you tell me what you heard about your child’s development? |

Farrell, Michael H., and Stephanie A. Christopher. 2012. “Frequency of High-Quality Communication Behaviors used by Primary Care Providers of Heterozygous Infants After Newborn Screening.” Patient Education and Counselling 90(2):226–232.

Farrell, Michael H., Pramita Kuruvilla, Kerry L. Eskra, Stephanie A. Christopher and Rebecca S. Brienza. 2009. “A Method to Quantify and Compare Clinicians’ Assessments of Patient Understanding during Counseling of Standardized Patients.” Patient Education and Counselling 77(1):128–135.

Two analysts (MB, ES) pilot-tested the codebook across a series of transcripts. Three study team members (MB, ES, ML) met to reconcile variances and achieve consensus, refining the codebook as needed to facilitate code dependability, confirmability, and credibility. Study team members (MS, ES, ML) additionally reviewed code segmentation to ensure a standardized approach. Upon the finalization of the codebook, independent coding was performed by two analysts (ES, MB) on 9 transcripts, representing 18% of the total sample. Inter-coder reliability was determined using Cohen’s kappa. (Table 1) Differences were reviewed and resolved in consensus (ES, MB, ML); in this review, no substantive differences between coder approach emerged. All remaining transcripts were coded by a single coder. We used NVivo 12 qualitative software to organize and index codes [29].

3. Results

3.1. Meeting Characteristics

Fifty family meetings from 24 cases for 25 infants were analyzed; for one case, twins were enrolled. These conferences included 32 parents. The infant’s mother was present for all family meetings; both parents were present in 64% (n=32) of meetings. (Table 2)

Table 2:

Infant and Parent Characteristics

| Characteristic | Median (Range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Infant Characteristics (n=25)a | |

| Gestational age at birth, wk | 33 (23–40) |

| Sex, Female | 14 (56) |

| Medical condition | |

| Prematurity (<37 weeks) | 15 (60) |

| Seizures | 7 (28) |

| Congenital heart disease | 7 (28) |

| Brain malformation | 7 (28) |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) | 5 (20) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 5 (20) |

| Parent Characteristics (n=32)b | |

| Age, y | 28 (19–38) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 21 (66) |

| Male | 8 (25) |

| Other/not reported | 2 (6) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White | 9 (28) |

| African American | 14 (44) |

| Asian | 2 (6) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 4 (13) |

| More than one race | 1 (3) |

| Other/not reported | 2 (6) |

| Level of education | |

| Less than high school | 3 (9) |

| High school/GED | 7 (22) |

| Some college | 4 (13) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 (22) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 4 (13) |

| Annual household income | |

| Less than $25,000 | 10 (31) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 9 (28) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 3 (9) |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 2 (6) |

| Greater than $150,000 | 5 (16) |

| Not reported | 1 (3) |

| Previous involvement in family member’s ICU care | 11 (34) |

One case has two infants enrolled.

One parent did not complete study surveys.

Multiple members of the clinical team attended most meetings, with a median of 5 clinical team members present (range 1–12). A neonatologist was present in most meetings (n=36, 72%). Many meetings included physicians from other pediatric specialties, including neurologists (n=25, 50%), palliative care physicians (n=15, 30%), and cardiologists (n=4, 8%). Non-physician clinicians included bedside nurses, social workers, and case managers. (Table 3)

Table 3:

Meeting Characteristics

| Characteristic | Median (Range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Meeting Characteristics (n=50) | |

| Number of meetings per case | 2 (1–7) |

| Meeting length, minutes | 46 (8–85) |

| Family members | |

| Mother present | 50 (100) |

| Father present | 32 (64) |

| Family members present | 14 (28) |

| Total family members present | 2 (1–7) |

| Team members | |

| Clinician type presenta | |

| Neonatology | 36 (72) |

| Neurology | 25 (50) |

| Palliative Care | 15 (30) |

| Other specialists’b | 13 (26) |

| Resident (pediatrics) | 10 (20) |

| MD/NP/PA student | 6 (12) |

| Unit staff present | |

| Bedside Nurse | 12 (24) |

| Case Manager | 11 (22) |

| Social Worker | 32 (64) |

| Physical, Occupational, and/or Speech Therapy | 5 (10) |

| Total team members present | 5 (1–12) |

| Meeting leader | |

| Neonatology | 29 (58) |

| Neurology | 16 (32) |

| Palliative Care | 2 (4) |

| Pediatric Intensive Care | 3 (6) |

Clinician type includes attending physicians, fellows, and APPs.

Other specialists include cardiology, endocrinology, genetics, ophthalmology, and pediatric intensive care.

3.2. Use of Assessments of Understanding

We identified 374 distinct assessments across all family meetings. All but one family meeting contained at least one assessment of understanding; these included 1) partial assessments, 2) close-ended assessments, and 3) open-ended assessments (Table 1). In no conferences did clinicians do a teach-back. The most common assessment type was partial (n=209, 56%), followed by close-ended (n=105, 28%) and open-ended (n=60, 16%). Most meetings contained at least one open-ended (n=30, 60%), close-ended (n=41, 82%), and/or partial (n=30, 60%) assessment. The majority of assessments were used by clinicians from neonatology, neurology, palliative care, and other consulting specialties. (Table 4)

Table 4:

Assessments of Understanding by Clinician Type

| Speaker | Partial | Close-ended | Open-ended | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cliniciana | ||||

| Neonatology | 33 | 42 | 21 | 96 |

| Neurology | 92 | 17 | 31 | 140 |

| Palliative Care | 23 | 4 | 1 | 28 |

| Other specialistsb | 48 | 30 | 5 | 83 |

| Unit Staff | ||||

| Bedside Nurse | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Case Manager | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Social Worker | 9 | 8 | 2 | 19 |

| Speech Therapy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Patient Advocate | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Clinician type includes attending physicians, fellows, and APPs.

Other specialists include cardiology, endocrinology, genetics, ophthalmology, and pediatric intensive care.

3.2.1. Partial and close-ended assessments

Partial assessments (n=209, 56%) included short phrases, such as “okay?”, “alright?”, and “you know?” Partial assessments were present in over half of family meetings (n=30, 60%); of all assessments identified, 56% (n=209) were classified as partial. Partial assessments often signaled the end of a speaker’s turn. For example, a neonatologist shared with parents of an infant with Trisomy 8:

I think the left side is the grade 2 and the right is the grade 1. So what that means is that there’s just some pressure in the kidneys from possibly infections or whatever she had, you know some issues with her bladder that there was some pressure that was going back into the kidneys. So that’s just something; it’s not severe, it’s just something that we need to follow on a regular basis. Okay?

Close-ended assessments included statements like “Okay, so any questions so far?” and “Was that clear?” Close ended assessments were present in the greatest number of family meetings (n=41, 82%); of all assessments identified, 28% (n=105) were classified as close-ended. For example, a cardiologist discussed the risks of a surgical procedure with parents of an infant with a rare genetic condition:

Cardiologist: I’ve actually talked to several different anesthesiologists, our partners from, who do sedation and everything for the babies who have this stuff, and they really couldn’t give me a number. Like, I can’t give you a percentage of what’s the chance cause I don’t think we know because this is a unique situation. But it’s definitely higher than it would be normally, given everything. I think the chance is still probably relatively low. I don’t think it’s fifty-fifty that something bad is gonna happen. It’s probably less than that, but we really don’t know. Does that make sense?

Mother: Yes, sir.

3.2.2. Open-ended assessments

Open-ended assessments were the least common type of assessment clinicians used overall, representing 16% (n=60) of all assessments of understanding. At least one open-ended assessment was present in over half of family meetings (n=30, 60%). Open-ended assessments were used by physicians from cardiology, neurology, neonatology, pediatric intensive care, and palliative care. Social workers on the palliative care team were the only non-physician clinicians to use open-ended assessments.

Open-ended assessments typically involved clinicians explicitly asking parents to share questions immediately after presenting new medical information. For example, a neurologist counseled a mother of a child with a congenital brain malformation:

I expect [patient] to keep gaining skills in her motor skills, but most children with this condition don’t walk on their own without extra help. What questions do you have about that?

Other times, open-ended assessments did not directly follow or explicitly reference information presented during the family meeting, presumably acting as standalone assessments; for example, “What questions do you have about her or about everything that’s happened?” and “What other questions do you have on your mind?”

3.3. Assessments of Baseline Understanding

In addition to assessing information in the same meeting, some clinicians assessed parents’ baseline understanding of an issue. Most often, these assessments were open-ended and general; for example, “Before I get started though, what do you understand already about what to expect for [patient]’s future?” This type of assessment often occurred when a new speaker-type began. Sometimes, baseline assessments asked parents to reflect on previous conversations with other providers; for example, a neonatologist asked, “I know Dr. [name] spent some time talking with you. Do you guys understand what the grade two and grade four are?

3.4. Responses to Assessments

Half (n=188/374; 50%) of all assessments of understanding did not yield any verbal response from parents or family members. Eighteen percent of assessments resulted in a yes/no responses (n=68/374, 18%), while approximately one-third of assessments resulted in an elaborated response (n=118/374, 31%). The presence of parent and family member responses to assessments varied by assessment type; open-ended assessments resulted in participants elaborating in their responses most of the time (n=55/60, 92%). These elaborated responses averaged 42 words each (range: 2–389). Nearly one-quarter of partial assessments yielded verbal responses (n=51/209, 24%); when parents and family members did respond, it was typically a yes/no response (n=33/51, 65%). (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Responses to assessments of understanding (AU) during family conferences in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

Elaborated responses included instances where participants elaborated on their understanding of medical knowledge beyond a simple “yes” or “no” statement. In some cases, participants asked for definitions of medical terms or for clarification on the medical information discussed. For example, one mother sought clarification on her daughter’s condition in response to an assessment: “So what happened to her this weekend has nothing to do with her brain?” Other elaborated responses requested that clinicians provide more information related to their child’s condition: “Can you, can you elaborate a little bit more on this?” Some parents and family members responded to assessments of understanding by summarizing information in their own words or stating the “bottom line.” For example, after receiving the results of his daughter’s MRI, one father concludes, “I think the key takeaway, again, is it’s a little bigger, but there’s not abnormality around the ventricles.” Other participants responded to assessments of understanding with their reactions to new information; for example, one mother, after hearing new information about her daughter’s brain condition, responded, “It’s a lot to process right now.”

Many elaborated responses resulted in parents and family members explaining their current understanding of their infants’ medical condition, treatment course, or prognosis. For example, one mother answered a baseline assessment of understanding by confirming facts about her child’s diagnosis: “So, what I know so far is she had the initial ultrasound that showed a bilateral grade three IVH.” Another mother responded to a baseline assessment with beliefs about her child’s neurologic development: “The motor skills, I don’t think she’ll have problems with that just ‘cause how she moves her legs.”

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Assessing patient understanding is a key tenet of high-quality communication. In this study of family conferences between parents and healthcare providers, assessments of understanding were common. The types of assessments were variable; there were no examples of a teach-back. When clinicians did ask parents to state their understanding in an open-ended way, they were more likely to prompt an elaborated response. Here, we highlight three key findings that can inform communication skills curricula.

First, open-ended assessments resulted in elaborated responses from parents. Communication curricula have long emphasized the importance of open-ended questioning when interviewing patients [15,30,31]; our findings suggest that this simple strategy may result in parents providing elaborated responses during clinical encounters. The benefits of prompting meaningful responses from parents are clear: it allows clinicians insight into the family’s understanding of their child’s condition. Eliciting meaningful parent responses can also help clinicians improve their communication skills in real-time by prompting them to refine their language, revisit confusing topics, or clarify misunderstood information.

Second, the most effective types of assessing understanding were rare. Partial assessments were overwhelmingly the most common assessment type. This finding may in part reflect that “okay?” or “alright?” are commonly used as fillers in colloquial speech. Alternatively, speakers may use such statements as a way of asking permission to move on to another topic. Regardless of their intent, partial assessments failed to yield a response from parents the majority of time; clinicians should avoid using partial assessments as a way to gauge parent understanding. Instead, clinicians should rely on open-ended assessments of understanding, especially after the delivery of key information. Members of interdisciplinary medical teams should be encouraged to hold each other accountable for appropriately assessing understanding during family conferences, as this is a shared responsibility among providers.

Teach-backs are considered a highly effective communication strategy associated with increased knowledge retention, patient-centered communication, and communication satisfaction [18,20,32,33]. Despite teach-backs being broadly recommended and applied across many clinical settings [21], there were no examples of a teach-back in this study; this finding is similar to those seen in other critical care settings [16,26,34]. The absence of teach-backs may reflect clinician concerns of whether or not this strategy is appropriate during NICU family conferences. Some clinicians cite time constraints as a barrier to the regular application of teach-backs in clinical settings [21,35]; teach-backs may be perceived as especially unrealistic during family conferences where multiple providers have limited time to share information with families. Furthermore, families may perceive a teach-back as “putting them on the spot” or “testing” their comprehension abilities [21,33,35–38]; asking parents to repeat back devastating information directly after hearing bad news could amplify distress [26,39,40]. Modeling teach-backs after a “Tell-Back-Collaborative” inquiry may help mitigate parent discomfort [37]. While there were no examples of a clinician asking a parent to restate new information within the current meeting, clinicians did ask parents to share their understanding of previous conversations. This strategy is similar to a teach-back in that both request parents restate information using their own words; these assessments have the added benefit of assessing baseline understanding prior to the disclosure of new medical information. The use and impact of teach-backs in this clinical context warrants further study.

Third, regardless of assessment type, parents responded to assessments in an elaborated way or asked clarifying questions only about one-quarter of the time. Because these clinical scenarios are complex and high-stakes, it is less likely parents did not have any information needs. Existing literature suggests that parents may be unsure of what questions to ask or what information is key [2]. The setting of NICU conferences may contribute to lower levels of comprehension and engagement among families caring for critically ill infants. In our study, there was a median of five medical providers and two family members present per meeting; parents were typically outnumbered. The imbalance between the number of providers and family members may lead some families to feel too intimidated to share information needs during family conferences. The range of topics covered and number of speaking turns present during conferences with multiple providers risks burdening families with too much information; families also may not have time to process new information before clinicians transition to another topic [41,42]. NICU parents also report high levels of emotional distress, which could further undermine their ability to process key information and engage with the medical team [2,5,43,44]. These ways in which the NICU environment may undermine parents’ understanding of decision-relevant information highlights the importance of identifying strategies to encourage elaborated responses during family conferences.

The quality of communication between clinicians and parents directly impacts parents’ psychosocial wellbeing, relationships with the medical staff, and ability to cope in the NICU environment [5]; gathering and understanding information about their child’s medical condition is an important aspect of coping for parents in this setting [45]. Creating opportunities for question-asking through open-ended assessments may be especially necessary to support minority populations, who report understanding difficulties, outstanding information needs, and feeling unheard by clinicians at higher rates than other populations [46,47]. Quality information exchange and mutual understanding are also essential to shared decision making and have been associated with improved patient outcomes and satisfaction with care [48–50]. Clinicians’ use of effective assessments of understanding has the ability to increase parents’ desire to communicate with the medical team and seek support within the NICU setting; interventions that encourage the application of assessments during family conferences may play an important role in achieving equitable, goal-concordant care for critically ill infants.

This study had several limitations. While all infants were critically ill and required a pediatric neurocritical care consult, the etiology of infants’ neurologic conditions was heterogeneous. Family meetings represent an important but isolated interaction between parents and the medical team; individual family meetings are not representative of all medical encounters between clinicians and families in the NICU. A minority of meetings included the use of a question prompt list, which may have increased assessments of understanding [13]. Meetings including certain types of clinicians, for example, palliative care clinicians, may qualitatively differ from others. We were limited in our ability to evaluate systematic differences between meetings that contained palliative care specialists and those that did not. We were unable to assess nonverbal responses to assessments. Because speaker intent is unknown, some partial assessments may have represented colloquial speech or permission to transition to the next topic instead of an assessment of understanding.

4.2. Conclusion

Future work should leverage these findings to build targeted communication interventions for families caring for critically ill children. Effectively assessing parent understanding has the potential to increase parent participation in conversations and ensure that they understand complicated medical information.

4.3. Practice Implications

Clinicians seeking to assess parent understanding should use open-ended assessments of understanding. This simple communication strategy has the potential to increase parent question-asking and decrease unmet information needs during family conferences.

Highlights.

We characterized how clinicians assess parent understanding in family conferences

Teach-backs and open-ended assessments were underutilized by clinicians

Partial and close-ended assessments rarely resulted in elaborated parent responses

Open-ended assessments helped facilitate parent engagement and question-asking

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health [K23NS116453]; the National Palliative Care Research Center; and the Greenwall Foundation.

The authors confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patients/persons described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of this story.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Ha JF, Longnecker N, Doctor-patient communication: a review, Ochsner J. 10 (2010) 38–43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096184/pdf/i1524-5012-10-1-38.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lemmon ME, Donohue PK, Parkinson C, Northington FJ, Boss RD, Communication Challenges in Neonatal Encephalopathy, Pediatrics. 138 (2016). 10.1542/peds.2016–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harrison H, The Principles for Family-Centered Neonatal Care, Pediatrics. 92 (1993) 643–650. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/92/5/643.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].de Wit S, Donohue PK, Shepard J, Boss RD, Mother-clinician discussions in the neonatal intensive care unit: agree to disagree?, J Perinatol. 33 (2013) 278–281. 10.1038/jp.2012.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wigert H, Dellenmark Blom M, Bry K, Parents’ experiences of communication with neonatal intensive-care unit staff: an interview study, BMC Pediatr. 14 (2014) 304. 10.1186/s12887-014-0304-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Boss RD, Donohue PK, Larson SM, Arnold RM, Roter DL, Family Conferences in the Neonatal ICU: Observation of Communication Dynamics and Contributions, Pediatr Crit Care Med 17 (2016) 223–230. 10.1097/pcc.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].A.E.M. E, S.S. N, S. G, C.P. E, A.-P.C. W, C.T. B, Readability of Invasive Procedure Consent Forms, Clin. Transl. Sci (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL, Readability Standards for Informed-Consent Forms as Compared with Actual Readability, N. Engl. J. Med (2003). 10.1056/nejmsa021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Perni S, Rooney MK, Horowitz DP, Golden DW, Mccall AR, Einstein AJ, Jagsi R, Assessment of Use, Specificity, and Readability of Written Clinical Informed Consent Forms for Patients With Cancer Undergoing Radiotherapy Supplemental content, JAMA Oncol. 5 (2019) 190260. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weiss BD, How to bridge the health literacy gap., Fam. Pract. Manag 21 (2014) 14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hersh WR, Totten AM, Eden KB, Devine B, Gorman P, Kassakian SZ, Woods SS, Daeges M, Pappas M, McDonagh MS, Outcomes From Health Information Exchange: Systematic Review and Future Research Needs, JMIR Med. Informatics (2015). 10.2196/medinform.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wittink H, Oosterhaven J, Patient education and health literacy, Musculoskelet Sci Pr 38 (2018) 120–127. 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lemmon ME, Huffstetler HE, Donohue P, Katz M, Barks MC, Schindler E, Brandon D, Boss RD, Ubel PA, Neurodevelopmental Risk: A Tool to Enhance Conversations With Families of Infants, J Child Neurol. 34 (2019) 653–659. 10.1177/0883073819844927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Boss RD, Lemmon ME, Arnold RM, Donohue PK, Communicating prognosis with parents of critically ill infants: direct observation of clinician behaviors, J Perinatol. 37 (2017) 1224–1229. 10.1038/jp.2017.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Makoul G, Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement, Acad. Med 76 (2001) 390–393. 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Farrell MH, Kuruvilla P, Eskra KL, Christopher SA, Brienza RS, A method to quantify and compare clinicians’ assessments of patient understanding during counseling of standardized patients, Patient Educ Couns 77 (2009) 128–135. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Farrell MH, Christopher SA, Frequency of high-quality communication behaviors used by primary care providers of heterozygous infants after newborn screening, Patient Educ Couns 90 (2013) 226–232. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Farrell MH, Kuruvilla P, Assessment of parental understanding by pediatric residents during counseling after newborn genetic screening, Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med 162 (2008) 199–204. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kornburger C, Gibson C, Sadowski S, Maletta K, Klingbeil C, Using “teach-back” to promote a safe transition from hospital to home: an evidence-based approach to improving the discharge process, J Pediatr Nurs. 28 (2013) 282–291. 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nickles D, Dolansky M, Marek J, Burke K, Nursing students use of teach-back to improve patients’ knowledge and satisfaction: A quality improvement project, J. Prof. Nurs 36 (2020) 70–76. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shersher V, Haines TP, Sturgiss L, Weller C, Williams C, Definitions and use of the teach-back method in healthcare consultations with patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis, Patient Educ. Couns 104 (2021) 118–129. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Deuster L, Christopher S, Donovan J, Farrell M, A method to quantify residents’ jargon use during counseling of standardized patients about cancer screening, J. Gen. Intern. Med 23 (2008) 1947–1952. 10.1007/s11606-008-0729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Street RL Jr., Measuring the quality of clinician-patient information exchange, Patient Educ Couns 99 (2016) ix–xi. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Feinberg I, Ogrodnick MM, Hendrick RC, Bates K, Johnson K, Wang B, Perception Versus Reality: The Use of Teach Back by Medical Residents, Heal. Lit Res Pr 3 (2019) e117–e126. 10.3928/24748307-20190501-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Howard T, Jacobson KL, Kripalani S, Doctor talk: physicians’ use of clear verbal communication, J Heal. Commun 18 (2013) 991–1001. 10.1080/10810730.2012.757398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR, The language of prognostication in intensive care units, Med. Decis. Mak 30 (2010) 76–83. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hong YR, Jo A, Cardel M, Huo J, Mainous AG, Patient-Provider communication with teach-back, patient-centered diabetes care, and diabetes care education, Patient Educ. Couns 103 (2020) 2443–2450. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Miles A, Huberman MB, An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis (2nd Edition), 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [29].QSR International, NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Windows, QSR Int. (2012) 8. http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-support/faqs. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Smith RC, Patient-centered interviewing : an evidence-based method, Philadelphia : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, c2002., Philadelphia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M, Maguire P, Lipkin M, Novack D, Till J, Doctor-patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement, Br. Med. J 303 (1991) 1385. 10.1136/bmj.303.6814.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].White M, Garbez R, Carroll M, Brinker E, Howie-Esquivel J, Is “teach-back” associated with knowledge retention and hospital readmission in hospitalized heart failure patients?, J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 28 (2013) 137–146. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31824987bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Badaczewski A, Bauman LJ, Blank AE, Dreyer B, Abrams MA, Stein REK, Roter DL, Hossain J, Byck H, Sharif I, Relationship between Teach-back and patient-centered communication in primary care pediatric encounters, Patient Educ Couns 100 (2017) 1345–1352. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].de Vos MA, Bos AP, Plötz FB, van Heerde M, de Graaff BM, Tates K, Truog RD, Willems DL, Talking With Parents About End-of-Life Decisions for Their Children, Pediatrics. 135 (2015) e465. 10.1542/peds.2014-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Roodbeen R, Vreke A, Boland G, Rademakers J, van den Muijsenbergh M, Noordman J, van Dulmen S, Communication and shared decision-making with patients with limited health literacy; helpful strategies, barriers and suggestions for improvement reported by hospital-based palliative care providers, PLoS One. (2020). 10.1371/journal.pone.0234926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dew K, Barton J, Stairmand J, Sarfati D, Signal L, Ascertaining patients’ understandings of their condition: a conversation analysis of contradictory norms in cancer specialist consultations, Heal. Sociol. Rev 28 (2019) 229–244. 10.1080/14461242.2019.1633945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kemp EC, Floyd MR, McCord-Duncan E, Lang F, Patients prefer the method of “tell back-collaborative inquiry” to assess understanding of medical information, J. Am. Board Fam. Med 21 (2008) 24–30. 10.3122/jabfm.2008.01.070093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Samuels-Kalow M, Hardy E, Rhodes K, Mollen C, “Like a dialogue”: Teach-back in the emergency department, Patient Educ Couns 99 (2016) 549–554. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chiarchiaro J, Buddadhumaruk P, Arnold RM, White DB, Quality of communication in the ICU and surrogate’s understanding of prognosis, Crit Care Med 43 (2015) 542– 548. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shermont H, Pignataro S, Humphrey K, Bukoye B, Reducing Pediatric Readmissions: Using a Discharge Bundle Combined With Teach-back Methodology, J. Nurs. Care Qual 31 (2016) 224–232. 10.1097/ncq.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].October TW, Dizon ZB, Roter DL, Is it my turn to speak? An analysis of the dialogue in the family-physician intensive care unit conference, Patient Educ Couns 101 (2018) 647–652. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boss RD, Donohue PK, Larson SM, Arnold RM, Roter DL, Family conferences in the neonatal ICU: Observation of communication dynamics and contributions, Pediatr. Crit. Care Med 17 (2016) 223–230. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Franck LS, Shellhaas RA, Lemmon M, Sturza J, Soul JS, Chang T, Wusthoff CJ, Chu CJ, Massey SL, Abend NS, Thomas C, Rogers EE, McCulloch CE, Grant K, Grossbauer L, Pawlowski K, Glass HC, group Neonatal Seizure Registry study, Associations between Infant and Parent Characteristics and Measures of Family WellBeing in Neonates with Seizures: A Cohort Study, J. Pediatr 221 (2020) 64–71 e4. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Loewenstein K, Barroso J, Phillips S, The Experiences of Parents in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Integrative Review of Qualitative Studies Within the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs 33 (2019) 340–349. 10.1097/jpn.0000000000000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Smith VC, Steelfisher GK, Salhi C, Shen LY, Coping with the neonatal intensive care unit experience: parents’ strategies and views of staff support, J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs 26 (2012) 343–352. 10.1097/JPN.0b013e318270ffe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K, Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans, Commonw. Fund (2002). https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2002/mar/diverse-communities-common-concerns-assessing-health-care (accessed March 18, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pérez-Stable EJ, El-Toukhy S, Communicating with diverse patients: How patient and clinician factors affect disparities, Patient Educ. Couns 101 (2018) 2186–2194. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM, How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes, (n.d.). 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martinez LS, Schwartz JS, Freres D, Fraze T, Hornik RC, Patient-clinician information engagement increases treatment decision satisfaction among cancer patients through feeling of being informed, Patient Educ. Couns 77 (2009) 384–390. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].October TW, Hinds PS, Wang J, Dizon ZB, Cheng YI, Roter DL, Parent Satisfaction with Communication Is Associated with Physician’s Patient-Centered Communication Patterns during Family Conferences, Pediatr. Crit. Care Med 17 (2016) 490–497. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]