Abstract

Introduction.

Existing research highlights interactions among child temperament, parents’ own anxiety symptoms, and parenting in predicting increased risk for anxiety symptom development (e.g., Ganiban et al., 2011). Theoretical models of child-elicited effects on parents (e.g., Dadds & Roth, 2001) have proposed that parents’ behaviors are likely not independent of children’s temperament; fearful children likely elicit more protective responses from parents and these parenting behaviors reinforces child anxiety and parents’ own anxiety.

Method.

The current study tests this model and examines whether there are bidirectional influences between early fearful temperament (i.e., dysregulated fear), maternal overprotection, and subsequent trajectories of maternal and child anxiety symptoms across early childhood. 166 children and mothers participated in a multi-method, longitudinal study of temperament risk from 2 – 6 years.

Results.

Results largely support our hypotheses, replicating and extending the prior literature. DF was associated with more maternal overprotective behavior, subsequent child anxiety symptoms, and maternal anxiety symptoms. Moreover, there were indirect (mediated) associations through maternal overprotective behavior and both child and mother anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion.

Results support the hypothesis that intergenerational transmission of anxiety was meditated through maternal behaviors and that the child-driven temperament effects are central to trajectories of child and maternal anxiety trajectories.

Developmental trajectories of anxiety symptom development in early childhood are complex and multifaceted. For instance, research highlights interactions among child fearful temperament and parenting in predicting increased risk for anxiety symptom development across childhood and adolescence (e.g., Kiel & Buss, 2014; Ganiban et al., 2011). In addition, there is robust support for intergenerational transmission of symptoms from parent symptoms and disorder to child (e.g., Rapee et al., 2014; Biederman et al., 2007). However, less work has examined child to parent effects.

Theoretical models of parent-child processes in the development of anxiety symptoms have proposed that parenting behaviors and parents’ symptoms are likely not independent of children’s temperament and anxiety and may be, in part, child-driven (e.g., Dadds & Roth, 2001). In this anxious-coercive model, fearful children elicit more protective responses from caregivers and these parenting behaviors, in turn, reinforce child fearful and anxious behavior in the moment and across development (Dadds & Roth, 2001; Rapee, 2013). Further, these parent behaviors can be self-reinforcing, especially if the behavior reduces child distress, and as such parents’ protective behaviors may increase and parents’ own anxiety may be impacted over time. However, the bulk of the extant literature examining these anxious-coercive patterns has been focused primarily on child outcomes. The current study addressed whether there are bidirectional influences between early fearful temperament and maternal overprotection in toddlerhood, and subsequent trajectories of maternal and child anxiety symptoms across early childhood. Specifically, we test whether maternal parenting behaviors, in the context of fearful temperament at age 2, predict trajectories of maternal and child anxiety symptoms across early childhood.

One of most robust findings in the anxiety development literature is that of the link between early forms of extreme fearful temperament (e.g., behavioral inhibition and dysregulated fear) and social anxiety development (e.g., Beesdo, Knappe & Pine, 2009; Fox & Pine, 2012; Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2013; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007). Behavioral inhibition (BI), a biological predisposition whereby some children are more fearful than others in fear-eliciting situations, is moderately stable. However, even within the BI literature, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in clinical outcomes. We have argued that characterizing patterns of behavior as a function of situational context provides a more nuanced way of capturing child fearfulness and risk for anxiety development (Buss & McDoniel, 2016). We have identified a pattern of behavior in toddlers, dysregulated fear (DF), that reflects a sensitivity to threat across a variety of novel situations. DF can be operationalized as a pattern of high fear across low-to high-threat situations (Buss, 2011) using a variety of statistical methods such as multi-level modeling to find a slope, person-centered latent profile analysis, or a threshold/fear sensitivity measurement (Buss et al., 2018). This context-inappropriate fear and avoidance indicates greater fear sensitivity in DF compared to other types of extremely fearful children (e.g., BI: Buss, 2011; Buss, et al., 2018). Furthermore, toddler DF predicted social anxiety symptoms at age 6 and a decade later at the transition to early adolescence (Buss et al., 2013; 2020).

Although these findings show a direct link between fearful temperament and anxiety symptom development, not all fearful children develop anxiety symptoms. Identification of factors that account for these different developmental trajectories is critical to identify which fearful children we should worry about the most. Naturally, examining parents’ symptoms and parenting process has received a great deal of attention in the literature.

Parents of fearful children often report viewing their children are more vulnerable and in need of protection. For instance, toddler shyness was associated with protective parenting behaviors 2 years later (Rubin, Nelson, Hastings, & Asendorpf, 1999). As a result, parents often engage in behaviors (e.g., comforting and protecting from threat) that they likely believe are sensitive to their child, and will help to reduce their children’s distress. However, these behaviors have been operationalized in a variety of ways that highlight a lack of sensitivity to what the child may need in a given situation. Specifically, Rubin and colleagues found that physical affection and intrusive behaviors (e.g., taking over for child; what authors called “oversolicitous”) were positively correlated and that this predicted highest levels of observed inhibition, especially for the temperamentally fearful toddlers (Rubin, Hastings, Stewart, Henderson, & Chen, 1997). Anxious parents also engage in these types of behaviors with their behaviorally inhibited children (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007).

These results suggest that despite the intention to reduce distress, protective parenting may exacerbate distress for fearful children. Consistent with this hypothesis and with the model put forth by Dadds & Roth (2001), maternal protective behaviors have been shown to alter the time course of distress across novel threat tasks in toddlers (Buss & Kiel, 2011). Specifically, although distress typically declined across the task, when maternal protective behaviors were observed the slopes were flatter (i.e., distress did not decrease across the task). Moreover, this pattern was only observed when toddler distress preceded the protective behavior, suggesting that mothers’ comforting behaviors in response to the toddlers’ distress are actually maintaining that distress reaction. Across several studies we have shown that these protective and comforting behaviors when observed in putatively low-threat situations (i.e., situations where most toddlers do not show fear) are predictive of increases in anxiety symptoms for fearful children (Kiel & Buss, 2010;2012). In addition, we have shown maternal overprotection mediates the association between toddler dysregulated fear and social anxiety symptoms in kindergarten (Kiel & Buss 2014). There is also evidence that fearful children may be soliciting these responses from their caregivers (Kiel and Buss, 2012; van der Bruggen et al. 2010; Drake & Ginsburg, 2011), adding to the interplay among these dyadic behaviors at a critical time in the development of self-regulation. For example, Rubin and colleagues found that age 2 shyness predicted ‘overprotective’ parenting at age 4, but that these parenting behaviors did not predict child behaviors across the same period (Rubin et al., 1999). Thus, these types of protective and comforting behaviors may alternatively relate to maintained distress and may unintentionally reinforce fear or wariness. In contrast, observed parental sensitivity has been shown to attenuate the development of anxiety symptoms in temperamentally at-risk toddlers (Warren et al., 2003; Warren & Simmens, 2005).

Turning to a separate, but overlapping, literature we also know that maternal internalizing psychopathology is a consistent predictor of child internalizing symptoms (Biederman et al., 2007; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Murray, Creswell & Cooper, 2009; Field et al., 2020). For instance, Cote and colleagues demonstrated that maternal lifetime depression was the most important predictor of trajectories of children’s internalizing symptom development after accounting for child temperament (Cote et al., 2009). In our own work, maternal internalizing symptoms (both depression and anxiety) were associated with a steep increase in children’s internalizing symptoms from age three to four, followed by a decrease from four to six (Zhou & Buss, 2021). Studies focused on anxiety specifically demonstrate robust effects from parental anxiety to child anxiety. Merikangas and colleagues have demonstrated in two studies that children who have a parent with an anxiety disorder are more likely (twice to three times the risk) to develop an anxiety disorder (Merikangas et al., 1998; 1999). This has been replicated across several studies showing increased risk for child anxiety disorders when mothers have a lifetime history of anxiety disorders (McClure et al., 2001; Biederman et al., 2001). In behaviorally inhibited preschoolers, maternal anxiety predicted the development of higher social anxiety symptoms in adolescence (Rapee et al., 2014).

There is also emerging evidence for child-driven effects on parental anxiety symptoms. A few studies examined effects from child temperament to parents’ symptoms. For example, studies have demonstrated associations between infant temperament and maternal anxiety (e.g., Behrendt et al., 2020; Agrati et al., 2015). Using a genetically informed design, Brooker and colleagues (2015) demonstrated bidirectional effects on infant negative affectivity and maternal anxiety at 9, 18, 27 months. Infant negative affectivity predicted maternal anxiety 18 months later and maternal anxiety at 9 months predicted infant negativity at 18 months.

Effects from child symptoms to mother symptoms have also been explored, albeit few studies have examined these effects for anxiety symptoms in early childhood. For instance, Ahmadzadeh and colleagues examined transactional influences in adoptive mothers and children while accounting for birth parent symptoms and found that greater child anxiety at 7 predicted more maternal anxiety symptoms at 8 (Ahmadzadeh et al., 2019). Xerxa and colleagues demonstrated small child to parent effects (from age 3 to age 9) in a large cohort study (Xerxa et al., 2020) and demonstrated that these effects were smaller than the parent to child effects. In an adolescent sample, changes in adolescent internalizing symptoms had a significant effect on changes in maternal symptoms (Nicolson, Deboeck, Farris, Boker & Borkowski, 2011). However, consistent with other studies, the effects from mother to child were stronger.

The Current Study

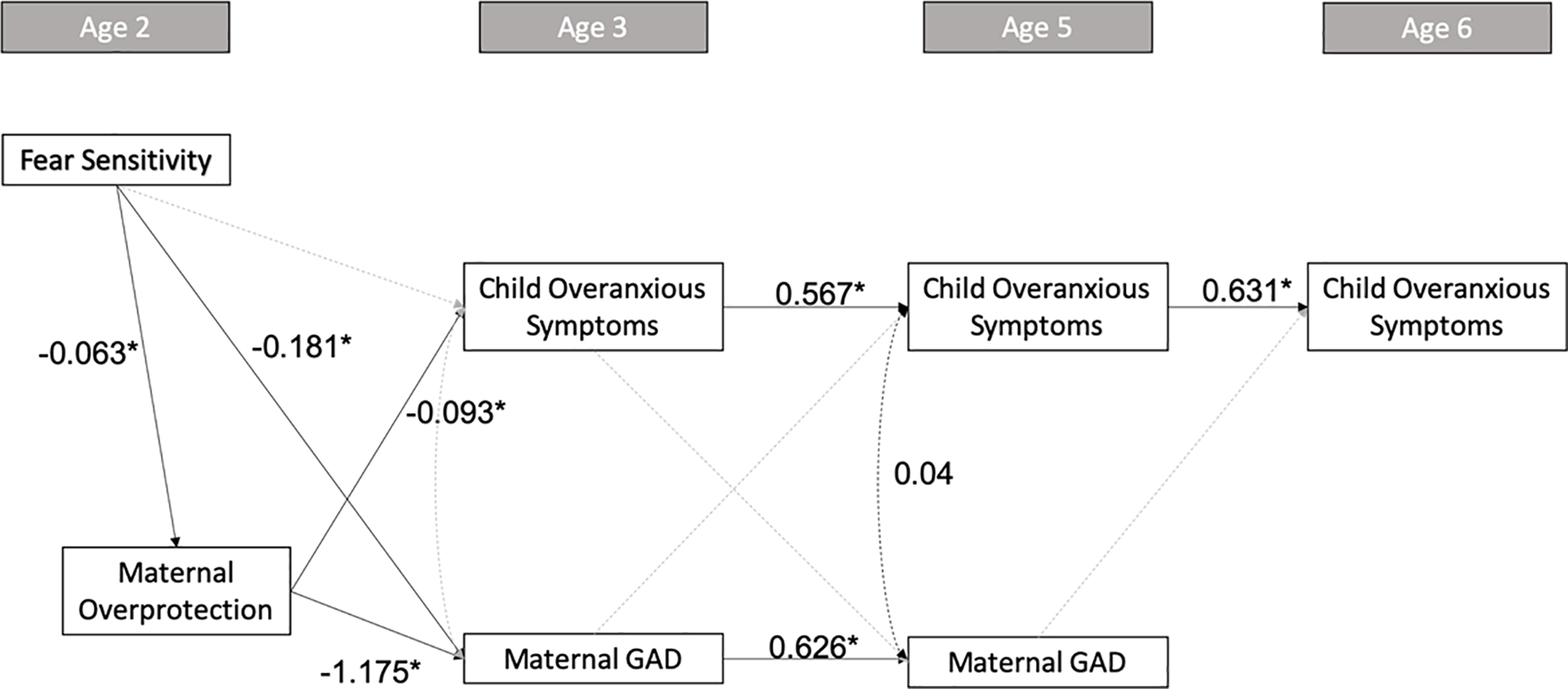

Temperamentally fearful children may be more vulnerable to the effects of parental anxiety and protective parenting behaviors. The combination of fearful temperament and overprotective parenting increases the risk for anxiety symptom development in children; when parents control the situation or their child’s response to that situation (i.e., do the regulation for them) that is not adaptive for children in the long-run (e.g., Ballash, Leyfer, Buckley & Woodruff-Borden, 2006). It reinforces the fear and avoidance and socializes children to rely on caregivers to regulate distress (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Figure 1 summarizes the model being tested in the current study. First, the current study will replicate previous work. We hypothesized that DF at age 2 would be associated with more maternal overprotective behaviors (concurrently), and that maternal overprotection would, in turn, predict more child anxiety symptoms across early childhood (ages 3, 5 and 6).

Figure 1.

Results of the path analysis on child fear sensitivity, maternal overprotection, and subsequent maternal and child anxiety. Standardized coefficients are presented for significant and approaching significant associations; * indicates significance at p < .05

Next, the current study will extend the literature in a few ways. First, most of the work to date has focused on mother to child effects and as a result we do not know whether the interplay between DF and overprotection will have effects on mother anxiety symptoms (at child ages, 3, 5 and 6). We hypothesized that DF would also predict more maternal anxiety symptoms. We hypothesized that maternal overprotection would mediate the association between DF and child (replicating our prior work) and mother anxiety symptoms at ages 3 and 5 and child symptoms at 6. We hypothesized that DF and overprotection would account for the stability of child and mother anxiety symptoms. Finally, we hypothesized bidirectional effects of mother and child anxiety symptoms from age 3–6.

Method

Participants

Data was obtained from a sample of 166 children (82 male, Mage = 24.5 months) and mothers participating in a longitudinal study designed to examine temperament and socioemotional development from age 2 to age 6. Participants were recruited through community-based sampling including a database containing families interested in research and through birth announcements. Of these participating families, 90% identified as Caucasian, 5% identified as Asian, 2% identified as mixed-race, 1% identified as Hispanic, 1% identified as American Indian, and 1% identified as African American. ~52% of participating families reported earning over $60,000 a year, ~40% reported earning between $31,000–59,000 a year, and ~ 7% reported earning less than $7,000 a year. Roughly 32% of mothers reported having completed their high school and/or some level of undergraduate education, 30% reported having completed their undergraduate degree, and 38% reported having completed some level of graduate education.

Procedures

18-month Screening

Screening measures were completed by 495 families at child age 18–20 months in order to oversample for anxiety risk in children as part of the original study design. Parents completed the Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003) and a 6-item questionnaire inquiring about the child’s fearfulness in low-threat, novel situations (i.e., those that most children find engaging) (see Buss, 2011 for more details). Children were identified as high in fear if they scored at least 1 SD above the mean on the ITSEA internalizing composite or on two of the ITSEA subscales (inhibition to novelty, anxiety, and separation distress) and scoring at least 1 SD above the mean on every item of the wariness questionnaire. 121 screened children were identified as potentially high fear, with 62 enrolling in the longitudinal study along with 62 additional participants randomly selected from screening (n=124 for original sample). As part of the 42-month laboratory visit, screening questionnaires were reexamined to identify and recruit exuberant children. Children were identified as exuberant if they met two of the three following criteria: 1 SD above the mean on the activity/impulsivity subscale, 1 SD below the mean on the inhibition to novelty subscale and scored a 2 on the depression subscale (a reverse score of children’s positive emotions). 81 children met this criteria, and 42 additional children were enrolled at 42 months.

24-month Laboratory Visit

During the first laboratory visit at age 24 months, mothers and children participated in a series of 6 tasks modeled from the toddler version of the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000) and related tasks (Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz & Buss, 1996). Children were introduced to six novel emotion eliciting stimuli of varying threat levels, such as watching a puppet show or being approached by an unfamiliar adult, and allowed to respond naturally (see for full description of tasks Buss, 2011).

Each task began with toddlers seated on their mothers’ lap. Clown and Puppet Show were designed to be novel but engaging and non-threatening (i.e., low threat). During the Clown task, a female experimenter entered the room dressed as a clown (i.e., multicolored wig, red nose) and invited the child to play with them. During Puppet Show, two animal puppets played games with each other an invited child to play with them. Two tasks were designed around interacting with strangers and considered to be moderate threat. In the Stranger Working a female stranger would enter the room and pretend to work, not interacting with the child unless initiated by the child. In Stranger Approach, a male stranger wearing a baseball cap would enter the room, slowly approaching the child, asking the toddler several short questions (e.g., “Are you having fun today?”). The high-threat tasks included Spider and Robot, toddlers began seated in their mother’s lap facing a small animatronic object (a large plush spider affixed to an RC car or small anthropomorphic robot, respectively). The Robot moved around on a platform, making sounds and lighting up. During Spider, after a similar period of inactivity the spider moved slowly towards the child and retreated (this occurred twice).

36-month and Kindergarten Questionnaires

Shortly following the child’s third (36 months) birthday, and during the fall and spring of their children’s kindergarten year, mothers were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete.

Measures

Fear Sensitivity

Children’s observed fear was calculated using second by second coding of the duration of children’s facial fear, bodily expressions of fear, freezing, and proximity to caregivers during each task. Facial fear was coded using the AFFEX coding system (Izard, Dougherty, & Hembree, 1983), while bodily fear was coded as the presence and duration of bodily expressions of fear such as diminished play. Freezing was coded as the child becoming still or rigid in response to a stimulus for durations of 2 seconds and longer. Proximity to mother was calculated using the duration of time spent in maximum proximity to caregiver (i.e., sitting on mother’s lap, physically touching). Finally, latency to freeze was measured as the number of seconds between the beginning of the task and the first onset of freezing behaviors. The duration of second-by-second coding of fear behaviors was summarized (with latency to freezing reverse coded). Coders were rated at 90% interrater agreement and levels of internal consistency were acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .61 to .73). As such, behaviors were averaged and compared to the total length of each episode in order to determine the percentage of each episode spent engaging in fearful behavior per episode.

Individual propensity (i.e., fear sensitivity) to exhibit fear across the six threat episodes was derived using a measurement model based on a nonlinear growth model (Ram & Grimm, 2015). In this model, episodes were ordered from low to high threat, and fear scores were then calculated as a person-specific metric which represented the point across the 6 fear tasks where the child displayed fear 50% of the task (see Buss et al., 2018 for details). The child-specific fear sensitivity scores were used in the analysis where lower scores represent high fearfulness (i.e., dysregulated fear; M = 4.52, SD = 1.31).

Maternal Overprotective Behaviors

Based on the work of Kiel (Kiel & Buss; 2010; 2012), the intensity of mother’s protective behaviors during the low threat tasks (Clown and Puppet Show) were scored and composited to create a single overprotective measure. These behaviors, such as shielding/blocking their child from interacting with the stimulus and/or physically moving the child to their lap, were coded in 10-second epochs on a scale representing 0 (no behavior observed) to 3 representing intense and prolonged behaviors (i.e., turning the child completely away from the stimulus and/or asking to end the task). The interrater reliability between coders was high (K = .79, and internal consistency of these behaviors was α = .69). The average intensity of protective behaviors from both tasks were composited to create a single overprotective score (M = .08, SD = .14).

Maternal Generalized Anxiety Symptoms

Maternal anxiety was assessed through maternal self-reported anxious behaviors on the General Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV (GADQ-IV; Newman et al., 2002). The GADQ-IV consists of 14 questions about specific behaviors scored for presence/absence (i.e., “Do you experience excess worry?”, “Do you find it difficult to control your worry once it starts?”), and the extent to which these behaviors interfere with daily life and /or cause distress (scored from 0= no distress to 8= severe distress). GADQ-IV has strong test-retest reliability and convergent validity with the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (K = .64, and r = .66, respectively; Newman, et al., 2002), and has been shown to have strong internal reliability across large-scale, non-clinical samples (N = 2,081, α = .83, Rodebaugh et al., 2008). Reliability in the current sample for both age 3 and age 5 Maternal Generalized Anxiety were found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .635 and .609, respectively). Mothers’ responses were scored, weighted, and summed to create a final Maternal Generalized Anxiety score ranging from 0–12 (M age 3 = 1.66, SD age 3 = 2.23, M age 5 = 2.19, SD age 3 = 2.91).

Child Anxiety Symptoms

Children’s anxiety symptoms were measured through maternal reported scores on the overanxious subscale of the Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ; Armstrong, et al., 2003). Mothers responded to 12 items assessing how accurately a variety of descriptions and behaviors represent their child (i.e., “Has nightmares”, or “Is Self-Conscious or easily embarrassed”) from 0= never / not true, 1=sometimes / somewhat true, 2 = often or very true. Scores were then averaged. The HBQ has been widely used in researching anxiety during childhood, with evidence supporting strong internal consistency and cross-informant agreement (Ablow, et al., 1999; Essex, et al., 2002; Lemery-Chalfant, et al., 2007), and identification of children with clinically significant generalized anxiety symptoms (Luby, et al., 2002). Further, the overanxious subscale has specifically been shown to have strong internal consistency across both clinically anxious and non-clinically anxious children (α = .78, and .77 respectively; Ablow, et al., 1999). In the current study, reliability for age 5 & 6 were both found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .88, and .66 respectively), however reliability at 36-months was determined to be relatively poor (Cronbach’s α = .39). This is likely due to 36 months being the earliest window of applicability for the ages in which the measure is validated.

Analytic Strategy

Path analysis was used to determine whether child fear sensitivity predicted both child overanxious symptoms and maternal general anxiety via the pathway of maternal overprotection, with child sex as a covariate. A structural equation model with manifest variables was tested using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in the R Environment for Statistical Computing. The lavaan package uses full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to account for unbiased estimates of data when data is missing at random. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust (Huber-White) standard errors was used. The model fit was evaluated using c2, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Good model fit is represented as p > 0.05, CFI ≥ 0.95, SRMR ≤ 0.05, RMSEA ≤ 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

There were 15 different patterns of missing data, and Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test indicated that data were missing completely at random, c2(63) = 59.46, p = .60. Table 1 contains the data we had available for each variable of interest for the present study. In order to account for missing data, FIML was used in all structural equation models.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fear Sensitivity | -- | ||||||

| 2. Maternal Overprotection | −0.35* | -- | |||||

| 3. Maternal Anxiety Age 3 | −0.13 | −0.07 | -- | ||||

| 4. Maternal Anxiety Age 5 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.46 * | -- | |||

| 5. Child Overanxiousness Age 3 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.10 | -- | ||

| 6. Child Overanxiousness Age 5 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.18 | 0.19 * | 0.28 * | -- | |

| 7. Child Overanxiousness Age 6 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.68 * | -- |

| Mean | 4.82 | 0.08 | 1.66 | 2.19 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| SD | 1.15 | 0.14 | 2.23 | 2.91 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| N | 124 | 123 | 101 | 109 | 101 | 111 | 106 |

p < 0.01

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations and correlations among variables used in the model are summarized in Table 1. Of note, maternal overprotection was positively skewed, with skew greater than 2 and kurtosis greater than 8.0 (Kline, 2011), and was thus square root transformed. Maternal anxiety scores at both age 3 and 5 were not extremely skewed but had positive skew (greater than 1.50 but less than 2) and were also square root transformed. Transformed variables did not have a significant skew or kurtosis and was used in all subsequent analyses. All other variables were approximately normally distributed (skew < 1.00, kurtosis < 8.0).

Path Model

The hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2 = 1.47, p = .48, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .001, SRMR = .01. The results of the path analysis are presented in Figure 1. Higher maternal overprotection was associated with greater fear sensitivity, β=−0.06, p < .01. Child fear sensitivity had both a direct effect on maternal general anxiety when children were aged 3, β=−0.18, p = .03, as well as an indirect effect via maternal overprotection, β=0.07, p = .02. The path from child fear sensitivity to maternal general anxiety when children were aged 5 via maternal overprotection and maternal general anxiety at age 3 was also significant, β=0.05, p = .03. Child fear sensitivity did not have a direct effect on child overanxious behaviors at age 3. However, there was an approaching significant indirect association from child fear sensitivity to child overanxious behaviors at age 3 via maternal overprotection, β=0.01, p = .07. The indirect path from child fear sensitivity to child overanxious symptoms at age 6 via maternal overprotection and child overanxious symptoms at ages 3 and 5 was not significant. There were also significant autoregressive paths for maternal general anxiety and child overanxious behaviors across time, though there were no significant effects from maternal general anxiety to child overanxious symptoms, or vice versa. There were no significant covariances between concurrent maternal general anxiety and child overanxious symptoms, though the covariance between maternal general anxiety and child overanxious symptoms at age 5 approached significance, β=0.04, p = .07.1

Discussion

The goals of the present study included examining (1) the interplay between DF and overprotection on both maternal and child anxiety symptoms during early childhood, and (2) bidirectional associations between maternal and child anxiety symptoms from ages 3 to 6. Our results largely confirmed our hypotheses that there are both direct and indirect associations from DF to both maternal and child anxiety during this early childhood period.

Consistent with prior work (Kiel & Buss, 2014), the results replicated findings that DF is associated with more maternal overprotective behaviors, and that maternal overprotection was in turn associated with more child anxiety symptoms. This finding is consistent with the anxious-coercive model (Dadds & Roth, 2001) whereby children high in DF elicit more maternal overprotective behaviors which unintentionally are reinforcing the fear and wariness and increase risk for the development of anxiety. As the anxious-coercive model suggestions, overprotective behavior likely has this effect on child anxiety because it serves to reinforce the fear by controlling the experience of the child with the putatively threatening stimuli. These findings are quite robust, and the current study adds to this literature.

To examine the effects from child temperament and parenting at age 2 to maternal anxiety symptoms, we tested whether or not DF and maternal overprotection would be associated with maternal anxiety symptoms across early childhood. We found evidence for both direct associations from DF to maternal anxiety at age 3 as well as indirect associations via maternal overprotection. In addition, path analyses demonstrated that DF was also indirectly associated with maternal anxiety symptoms when children were 5 via maternal overprotection, suggesting that the DF and overprotection were associated with the maintenance of maternal anxiety symptoms from age 3 to age 5. This finding addresses the gap in the literature as prior studies of temperamental fear largely focus on child outcomes, and bidirectional effects more generally are still rare. In particular, these current findings are consistent with studies that demonstrate temperament to parent symptom effects in early childhood (e.g., Brooker et al., 2015). Children play a role in regulating the affective state of the mother – for example, children expressing negative affect and distress may elicit negative affect and caregiving in mothers (e.g., Soltis, 2004). For mothers who have difficulty with emotion regulating, having a child frequently elicit negative affect may play a role in the development and maintenance of maternal anxiety (Scaramella & Leve, 2004; Kerns, Pincus, McLaughlin & Comer, 2017).

These findings extend the literature by showing additional effects on maternal anxiety and add to the growing literature examining the complex set of mechanisms underlying transmission of anxiety symptoms. For instance, Eley and colleagues (2015) used a twin study design to demonstrate that intergenerational transmission of anxiety is environmentally mediated (rather than genetically). Environments created by mothers with high levels of internalizing (e.g., anxiety) symptoms can be particularly stressful for children due to factors such as increased negative affect, dysfunctional behaviors, and cognitions (Goodman & Gotlieb, 1999; Dix, 1991; Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Cho, 2003; Bayer et al., 2006; Murray et al., 2009). Studies have shown that maternal anxiety is associated with overprotective parenting strategies (Bayer et al., 2006), parent worry, and socialization goals (Kiel & Buss, 2010; Kiel, Price & Buss, 2020). Additional work suggests that maternal worry (about the child) may be an important factor to consider. For instance, we have shown that mothers who report more worry about their child predicted that their child would be more fearful in the laboratory, but this was not always accurate (Kiel & Buss, 2010). We have also demonstrated that parent-focused (vs. child-focused) goals were associated with greater maternal protective behavior (Kiel & Buss, 2012). Thus, mothers who are more focused on alleviating their own distress may be more likely to engage in parenting behaviors that increase child distress and risk for anxiety. These findings suggest that mother’s worry or anxiety may be biasing their perceptions of their child’s behavior: more negative and less accurate as other work has demonstrated (Dix, 1991; Leerkes & Crockenberg, 2003). As we reported above, when parents are anxious and view their children as vulnerable, they are more likely to engage in parenting behaviors that increase child distress and anxiety.

We did not find a direct association between DF and child overanxiousness at age 3, despite robust evidence of this association in previous work (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2013; Buss et al., 2018). The symptoms on this scale of the HBQ most closely align with generalized anxiety symptoms, which given the ages we examined in our study may account for the lack of direct findings. Furthermore, DF, like behavioral inhibition, may be a specific risk factor for social anxiety symptoms and only when examined through the lens of overprotective parenting does other anxiety symptoms emerge. In addition, we did not find evidence for indirect links between DF to child symptoms through maternal overprotection at the later timepoints. The current analyses suggest this ‘parenting’ effect does not appear at later timepoints either, although it is difficult to interpret without additional parenting assessments after age 2. At the same time, we know that maternal characteristics do account for child internalizing in a separate study using the same sample. Specifically, we found that maternal internalizing symptoms were associated with steeper increases in child internalizing symptoms followed by decreases (Zhou & Buss, 2021). The findings from the current study, along with our previous work (e.g., Buss & Kiel, 2013) suggest that the indirect pathway through early maternal overprotection is what may set the child up for the development of anxiety symptoms in children by accounting for higher anxiety in preschool. Therefore, future studies should also examine repeated measures of overprotective parenting in order to determine whether this type of parenting behavior continues to have an effect.

Finally, turning specifically to bidirectional effects of anxiety symptoms from age 3–6, our results did not support this hypothesis. We found no evidence for bidirectional associations between child and maternal anxiety symptoms. One possibility is that anxiety symptoms, for children especially, were quite low in this preschool period. This is not surprising given that these symptoms include GAD-related symptoms like worry, which are developmentally not as prevalent in early childhood and that this was a low-risk sample. In fact, much of the work that demonstrates bidirectional effects is in older children and adolescents. In a recent paper, Pelham et al (2020) demonstrated that the association between maternal depression and later child behavior outcomes (including internalizing symptoms) was the result of confounding variables rather than a causal effect. Although we would not characterize the interplay between DF and maternal overprotection as confounding variables, it is possible that accounting for these processes at age 2 made it more difficult to detect additional bidirectional influences. Finally, other studies have also failed to find such effects. For instance, accounting for father anxiety, Ahmazadeh et al (2019) found father to child anxiety but not mother to child anxiety effects. Others have demonstrated both maternal and father anxiety symptoms effects on child anxiety symptoms in early childhood (Field et al., 2020). Therefore, other parenting and family processes would be important to explore in subsequent studies.

Limitations

There are a few limitations worth noting. First, our sample was 90% white, which limits the generalizability of our findings. There is evidence that child anxiety and internalizing symptoms may vary across culture and race/ethnicity (Kirmayer, 2001; Anderson & Mayes, 2010), and future studies should examine if the associations from the present study can be replicated in more diverse samples. Additionally, the sample was also a low-risk sample, despite the temperamental oversampling in infancy. In particular, the mean levels of maternal general anxiety symptoms are relatively low in this sample. Therefore, the patterns may be different in a sample with higher levels of maternal anxiety and/or other environmental risk factors.

We did not have maternal anxiety symptoms at first timepoint or overprotection measures beyond the 24-month timepoint. Therefore, we were unable to test the interplay among these factors across development. In particular, we are limited in testing the pathway from maternal anxiety to maternal overprotective parenting. There are some studies that suggest that maternal anxiety and worry may drive increased overprotection, especially if children are temperamentally inhibited or fearful (Kalomiris & Kiel, 2016). Future studies should aim to examine the interplay between maternal anxiety, maternal overprotection and child anxiety across time.

An additional limitation is that both maternal and child anxiety were measured using the same informant. Xerxa and colleagues (2020) demonstrate that mothers’ reports of child internalizing symptoms are associated with their own psychopathology. However, studies with children under six also suggest that preschoolers are limited in self-report of anxiety symptoms (Luby et al., 2007). Future studies should aim to replicate the present study with a subset of the anxiety symptoms that preschoolers may be able to reliably self-report on, or use teacher- or father-report of child anxiety symptoms.

Finally, in the current study, we were unable to account for heritable influences of maternal anxiety on child temperament or child anxiety.

Conclusion

The current study adds to a growing literature examining bidirectional influences on anxiety development by providing evidence that there are anxiety-supporting family processes (both mother and child directed) that reinforce anxiety symptoms in both mothers and children. We demonstrated that fearful temperament and maternal overprotection are important risk factors accounting for anxiety symptoms in both children and mothers during preschool. These findings have implications for identifying characteristics and behaviors that increase anxiety risk and are likely modifiable.

Acknowledgments

Data for this study are drawn from NIMH R01MH075750 awarded to Kristin Buss. Dr. Buss is also supported by the Social Science Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We wish to thank the families who participated in this study.

Footnotes

A post hoc analysis controlling for maternal depressive symptoms at age 3 and age 5 revealed that associations in the main model held. However, this model with maternal depressive symptoms as a covariate did not fit the data as well as the main model, χ2 = 0.01, p < .05, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA =.12, SRMR = .06.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ahmadzadeh YI, Eley TC, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM, & McAdams TA (2019). Anxiety in the family: a genetically informed analysis of transactional associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(12), 1269–1277. 10.1111/jcpp.13068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH, & The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment. (2003). Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0). MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development (David J. Kupfer, Chair), University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Ballash N, Leyfer O, Buckley AF, & Woodruff-Borden J (2006). Parental control in the etiology of anxiety. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(2), 113–133. 10.1007/s10567-006-0007-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Sanson AV, & Hemphill SA (2006). Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 542–559. 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, & Pine DS (2009). Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524. 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt HF, Wade M, Bayet L, Nelson CA, & Enlow MB (2020). Pathways to socioemotional functioning in the preschool period: The role of child temperament and maternal anxiety in boys and girls. Developmental and Psychopathology, 32(3), 961–974. 10.1017/S0954579419000853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Hérot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, & Faraone SV (2001). Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1673–1679. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, & Faraone SV (1998). Biased maternal reporting of child psychopathology? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(1), 10–12. 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Scaramella LV, & Reiss D (2015). Associations Between Infant Negative Affect and Parent Anxiety Symptoms are Bidirectional: Evidence from Mothers and Fathers. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(DEC), 1875. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 804–819. 10.1037/a0023227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Cho S, Morales S, McDoniel M, Webb AF, Schwartz A, Cole PM, Dorn LD, Gest S, & Teti DM (2020). Toddler dysregulated fear predicts continued risk for social anxiety symptoms in early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 10.1017/S0954579419001743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Davis EL, Kiel EJ, Brooker RJ, Beekman C, & Early MC (2013). Dysregulated Fear Predicts Social Wariness and Social Anxiety Symptoms during Kindergarten. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(5), 603–616. 10.1080/15374416.2013.769170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Davis EL, Ram N, & Coccia M (2018). Dysregulated Fear, Social Inhibition, and Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia: A Replication and Extension. Child Development, 89(3), e214–e228. 10.1111/cdev.12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Goldsmith HH (2000). Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery—Toddler version. Psychology Department Technical Report, University of Wisconsin, Madison [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Kiel EJ (2011). Do maternal protective behaviors alleviate toddlers’ fearful distress? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 136–143. 10.1177/0165025410375922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Kiel EJ (2013). Temperamental Risk Factors for Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. In Pediatric Anxiety Disorders (pp. 47–68). Springer; New York. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6599-7_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & McDoniel ME (2016). Improving the Prediction of Risk for Anxiety Development in Temperamentally Fearful Children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 14–20. 10.1177/0963721415611601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, & Little TD (2003). The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 31(5), 495–514. 10.1023/a:1025449031360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté SM, Boivin M, Liu X, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, & Tremblay RE (2009). Depression and anxiety symptoms: Onset, developmental course and risk factors during early childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50(10), 1201–1208. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, & Leerkes EM (2004). Infant and maternal behaviors regulate infant reactivity to novelty at 6 months. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1123–1132. 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, & Roth JH (2001). Family Processes in the Development of Anxiety Problems. In The Developmental Psychopathology of Anxiety (pp. 278–303). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med:psych/9780195123630.003.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T (1991). The Affective Organization of Parenting: Adaptive and Maladaptative Processes. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 3–25. 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake KL, & Ginsburg GS (2011). Parenting practices of anxious and nonanxious mothers: A multi-method, multi-informant approach. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 33(4), 299–321. 10.1080/07317107.2011.623101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, & Kupfer DJ (2002). The Confluence of Mental, Physical, Social, and Academic Difficulties in Middle Childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(5), 588–603. 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP, Lester KJ, Cartwright-Hatton S, Harold GT, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM, & Leve LD (2020). Maternal and paternal influences on childhood anxiety symptoms: A genetically sensitive comparison. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 68, 101123. 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, & Pine DS (2012). Temperament and the emergence of anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(2), 125–128. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Ulbricht J, Saudino KJ, Reiss D, & Neiderhiser JM (2011). Understanding child-based effects on parenting: Temperament as a moderator of genetic and environmental contributions to parenting. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 676–692. 10.1037/a0021812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Gotlib IH (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 28(3), 225–233. 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, Bloomfield A, Biederman J, & Rosenbaum J (2008). Behavioral inhibition. Depression and Anxiety, 25(4), 357–367. 10.1002/da.20490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco JA, Simoes NA, & Henin A (2008). High risk studies and developmental antecedents of anxiety disorders. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics, 148C(2), 99–117. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Hembree EA, Dougherty LM, & Spizzirri CC (1983). Changes in facial expressions of 2- to 19-month-old infants following acute pain. Developmental Psychology, 19(3), 418–426. 10.1037/0012-1649.19.3.418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalomiris AE, & Kiel EJ (2016). Maternal anxiety and physiological reactivity as mechanisms to explain overprotective primiparous parenting behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(7), 791–801. 10.1037/fam0000237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CE, Pincus DB, McLaughlin KA, & Comer JS (2017). Maternal emotion regulation during child distress, child anxiety accommodation, and links between maternal and child anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 52–59. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2010). Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children’s responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development, 19(2), 304–325. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2010). Maternal expectations for toddlers’ reactions to novelty: Relations of maternal internalizing symptoms and parenting dimensions to expectations and accuracy of expectations. Parenting, 10(3), 202–218. 10.1080/15295190903290816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2012). Associations among Context-specific Maternal Protective Behavior, Toddlers’ Fearful Temperament, and Maternal Accuracy and Goals. Social Development, 21(4), 742–760. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2014). Dysregulated Fear in Toddlerhood Predicts Kindergarten Social Withdrawal through Protective Parenting. Infant and Child Development, 23(3), 304–313. 10.1002/icd.1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Premo JE, & Buss KA (2016). Gender Moderates the Progression from Fearful Temperament to Social Withdrawal through Protective Parenting. Social Development, 25(2), 235–255. 10.1111/sode.12145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Price NN, & Buss KA (2020). Maternal anxiety and toddler inhibited temperament predict maternal socialization of worry. Social Development. 10.1111/sode.12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ (2001). Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Methodology in the Social Sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lemery-Chalfant K, Schreiber JE, Schmidt NL, Van Hulle CA, Essex MJ, & Goldsmith HH (2007). Assessing internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems in young children: Validation of the macarthur HBQ. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(10), 1315–1323. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f616c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Dierker L, Harrington R, Kraemer HC, & Kupfer DJ (2002). Differential Performance of the MacArthur HBQ and DISC-IV in Identifying DSM-IV Internalizing Psychopathology in Young Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(4), 458–466. 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Brennan PA, Hammen C, & Le Brocque RM (2001). Parental Anxiety Disorders, Child Anxiety Disorders, and the Perceived Parent - Child Relationship in an Australian High-Risk Sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(1), 1–10. 10.1023/A:1005260311313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Dierker LC, & Szatmari P (1998). Psychopathology among Offspring of Parents with Substance Abuse and/or Anxiety Disorders: A High–risk Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(5), 711–720. 10.1111/1469-7610.00370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S, Dierker L, & Grillon C (1999). Vulnerability factors among children at risk for anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 46(11), 1523–1535. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00172-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Creswell C, & Cooper PJ (2009). The development of anxiety disorders in childhood: An integrative review. Psychological Medicine, 39(9), 1413–1423. 10.1017/S0033291709005157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH and Buss K (1996), Behavioral Inhibition and Stress Reactivity: The Moderating Role of Attachment Security. Child Development, 67(2), 508–522. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, Constantino MJ, Przeworski A, Erickson T, & Cashman-McGrath L (2002). Preliminary reliability and validity of the generalized anxiety disorder questionnaire-IV: A revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 33(2), 215–233. 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80026-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JS, Deboeck PR, Farris JR, Boker SM, & Borkowski JG (2011). Maternal Depressive Symptomatology and Child Behavior: Transactional Relationship With Simultaneous Bidirectional Coupling. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1312–1323. 10.1037/a0023912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, West SG, Lemery-Chalfant K, Goodman SH, Wilson MN, Dishion TJ, & Shaw DS (2020). Depression in mothers and the externalizing and internalizing behavior of children: An attempt to go beyond association. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 10.1037/abn0000640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, & Grimm KJ (2015). Growth Curve Modeling and Longitudinal Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science (pp. 1–31). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM (2013). The preventative effects of a brief, early intervention for preschool-aged children at risk for internalising: Follow-up into middle adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 54(7), 780–788. 10.1111/jcpp.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM, & Heimberg RG (2008). The factor structure and dimensional scoring of the generalized anxiety disorder questionnaire for DSM-IV. Assessment, 15(3), 343–350. 10.1177/1073191107312547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(1), 1–36. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, & Chen X (1997). The Consistency and Concomitants of Inhibition: Some of the Children, All of the Time. Child Development, 68(3), 467. 10.2307/1131672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Nelson LJ, Hastings P, & Asendorpf J (1999). The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23(4), 937–957. 10.1080/016502599383612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, & Leve LD (2004) Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(2), 89–107. 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000030287.13160.a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis J (2004). The signal functions of early infant crying. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(4), 443–458. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0400010X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJM, Bögels SM, & Paulussen-Hoogeboom MC (2010). Parenting behaviour as a mediator between young children’s negative emotionality and their anxiety/depression. Infant and Child Development, 19(4), 354–365. 10.1002/icd.665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SL, Gunnar MR, Kagan J, Anders TF, Simmens SJ, Rones M, Wease S, Aron E, Dahl RE, & Sroufe LA (2003). Maternal panic disorder: Infant temperament, neurophysiology, and parenting behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 814–825. 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046872.56865.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SL, & Simmens SJ (2005). Predicting toddler anxiety/depressive symptoms: Effects of caregiver sensitivity on temperamentally vulnerable children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(1), 40–55. 10.1002/imhj.20034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang WC, & Chu BC (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 44(1), 134–151. 10.1111/1469-7610.00106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xerxa Y, Rescorla LA, Ende J, Hillegers MHJ, Verhulst FC, & Tiemeier H (2020). From Parent to Child to Parent: Associations Between Parent and Offspring Psychopathology. Child Development, 10.1111/cdev.13402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.