Abstract

Background:

Elevated fear and anxiety regarding donation-related stimuli (e.g., needles, pain, blood, fainting) has been associated with reduced blood donor recruitment and retention. The present longitudinal study tests the notion that this inverse relationship may be accounted for by lower donation confidence and more negative donation attitudes among fearful first-time donors.

Study Design and Methods:

In a sample of 1,479 first-time whole blood donors [67.9% female; Mean Age= 19.3 (SD = 2.5) years], path analyses were conducted to examine relationships among donor ratings of fear of blood draw and donation anxiety obtained approximately one week after donation, donation confidence and attitudes assessed approximately six weeks later, and donation attempts over the fourteen months following the original donation.

Results:

Path analyses indicated that both fear of blood draws and donation anxiety were associated with fewer attempted donations, and that these effects were indirectly mediated by a combination of lower donor confidence and more negative donation attitudes.

Conclusion:

Because retention of new blood donors is essential to maintain a healthy blood supply, the results of the present study suggest that first-time donors should be assessed for fear and anxiety so that appropriate strategies can be provided to address their concerns, bolster their confidence and attitudes, and ultimately promote their long-term retention.

Keywords: blood donor retention; first-time donors; fear; anxiety; confidence, attitudes

INTRODUCTION

Previous research has demonstrated that blood donors who report donation-related anxiety (i.e., apprehension about future donations) and donation-related fear (i.e., concerns about stimuli in the immediate donation environment, such as needles and blood) have lower future donation intentions and a decreased likelihood of actual donation behavior.1-7 Whereas anxious and fearful reactions to donation procedures and related stimuli likely dissuade many people from ever choosing to give blood, for a variety of reasons many others decide to donate despite their concerns. In fact, a recent survey8 indicated that 71.8% of first-time blood donors reported a fear of having blood drawn, and similarly high proportions reported a fear of blood donation needles (71.1%), feeling pain while donating (72.5%), and feeling faint or lightheaded while donating (67.6%). Although the frequency of such fears decreased with increasing experience as a donor, one third or more of those with at least six prior donations continued to report such fears.

Because fear and anxiety are not only deterrents to blood donation but also risk factors for donation-related vasovagal reactions,6,9-12 it is important to understand how these concerns can be addressed among current and prospective donors in order to promote an optimal donation experience and encourage donor retention. Consistent with this goal, Gilchrist and colleagues13 used a cross-sectional mediational analysis to examine the associations among various medical fears and donor motivation variables in an adult sample of primarily non-donors. Their analyses confirmed existing evidence that fear was related to a decreased intention to donate, and they provided novel evidence that the inverse relationship between fear and intention was accounted for by indirect effects. That is, fear was shown to be associated with less donor self-efficacy (i.e., less confidence in one’s ability to give blood) and more negative donation attitudes. In turn, lower self-efficacy and more negative attitudes were associated with lower intentions of giving blood.

Whereas the findings of Gilchrist and colleagues13 highlight donation self-efficacy and attitudes as reasonable targets for intervention among current and prospective donors who report fear, at the same time the study was limited in two significant respects. First, the observed relationships were based on survey responses reported at a single timepoint and therefore can only suggest a potential causal relationship between fear and donation intention. Second, although donation intention is a predictor of future donation behavior, it is an imperfect predictor at best.5,14,15 To address these limitations, the present report describes a longitudinal analysis of the relationships among fear and anxiety, self-efficacy, attitudes, and donation behavior in a sample of first-time blood donors. Using data from the blood donor CARE project,16,17 path analyses were conducted to examine the relationship among baseline fear and anxiety ratings, donor motivation variables (self-efficacy, attitude, and intention) collected approximately six weeks later, and instances of subsequent donation attempts over a fourteen month follow-up period. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that higher baseline fear and anxiety would predict a decreased likelihood of a subsequent donation attempt, and that this relationship would be mediated by the effect of higher fear and anxiety on lower donation self-efficacy and less positive donation attitudes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment and Participants

Participants in the blood donor CARE trial16,17 were recruited from the New York Blood Center donor database. Eligible individuals included all whole blood donors who were identified as being first-time donors with New York Blood Center in the previous week, 16 to 24 years old at the time of donation, and eligible to donate again. In addition, those contacted had to be willing to be randomly assigned to an intervention group, and have or be willing to establish a Facebook account. Exclusion criteria included a self-report of having more than one previous donation (with New York Blood Center or other blood collection agencies). Invitations to participate in the study were emailed to 23,064 individuals between 5/27/2016 and 6/10/2019, with study enrollment closed on 6/19/2019 when a sufficient sample had been recruited. Although the clinical trial included 1,746 participants who completed the post-intervention surveys, the fear of blood draw question used in this report was added after the clinical trial began and therefore the sample for the present report was limited to the 1,479 participants who received this fear question.

The final sample had a mean age of 19.3 years (SD = 2.5) and self-identified as female (67.9%), male (31.4%), or transgender (0.7%). With respect to race, participants self-identified as White (54.8%), Asian (17.8%), Black (9.3%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (0.7%), Pacific Islander (0.5%), or Multiple race or Other (16.8%). In addition, 23.6% of the sample self-identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Survey materials

The measures analyzed for this study were drawn from the larger clinical trial assessment battery and are described in Table 1. All scales were scored by calculating the mean score across the scale items. In addition to these measures, participants also provided basic demographic information such as age, self-reported gender, race, ethnicity, and donation history at the baseline assessment.

Table 1.

Assessment measures obtained at baseline and post-intervention.

| Measure | Description | Sample Item | Item Anchors | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Level of nervousness, tension, and anxiety with respect to donating blood (3 items).28 | “If I donate blood I will feel nervous.” | 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Very much) |

.96 |

| Fear | Single-item measure of donation fear6,11,12 | “How afraid are you of having blood drawn from your arm?” | 0 (Not at all afraid) to 4 (Extremely afraid) |

NA |

| Self-Efficacy | Confidence or self-efficacy in one’s ability to engage in blood donation and to cope with barriers that may arise (6 items).16 | “I am confident that I can cope with any concerns I may have about donating blood.” | 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Extremely) |

.91 |

| Attitude | Thoughts and feelings about blood donation (6 items).29 | “For me, donating blood within the next year would be…” | 1 (Unpleasant) to 7 (Pleasant) |

.81 |

| Intention | Intention to donate blood again in the next year (5 items).29 | “I plan to donate blood in the next year.” | 1 (Disagree) to 7 (Agree) |

.97 |

Procedure

Study invitations for the blood donor CARE trial were sent by email in the week following eligible donations. Interested donors (and the parents of minor-age donors) were directed to the study website where a full study description was available. Donors who provided informed consent (or parental informed consent and assent for minor-age donors) were then linked to the online time 1 (baseline) assessment materials. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools18,19 hosted at Ohio University. All interactions with participants were via email, telephone, and social media.

At the completion of the time 1 assessment, the REDCap system automatically randomized respondents to one of eight parallel groups for the clinical trial study. All participants received an email with instructions regarding their group assignment. Participants who completed their assigned intervention were eligible to complete the time 2 (post-intervention) assessment. A survey link was emailed to eligible participants six weeks after completion of their time 1 assessment. To encourage participation and retention, participants who completed their assigned intervention and the time 2 survey received a check for US$100. The donor database of New York Blood Center was used to track subsequent donation behavior. All donation attempts in the 421 days following each participant’s initial donation (to allow for a one-year follow-up after an eight-week waiting period for whole blood donation) were retrieved for the participants who had completed the time 1 and time 2 assessments. The last follow-up window closed on 7/31/2020. These procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Ohio University and the New York Blood Center. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02717338).

Statistical Analysis

A series of path analyses was conducted to examine the relationship among baseline fear and anxiety ratings, donor motivation variables (self-efficacy, attitude, and intention) collected approximately six weeks later, and instances of subsequent donation attempts over a fourteen month follow-up period. Consistent with Gilchrist et al,13 a path analysis was first conducted using donation anxiety as the predictor, intention as the dependent variable, and self-efficacy and attitude as potential mediators. To control for effects related to the blood donor CARE interventions, intervention group was included as a covariate on the self-efficacy, attitude, and intention variables for all of the path analyses. After modification based on the fit indices, this analysis was repeated after adding donation attempt (yes/no) as the dependent variable. Following the analyses using donation anxiety as the predictor variable, similar analyses were conducted using fear of blood draw as the predictor variable and then using both donation anxiety and fear of blood draw as potential predictors in the same model. To illustrate the magnitude of the effect of anxiety and fear of blood draw on donation attempt, the predicted probability of return was calculated for participants in the blood donor CARE no-treatment control condition. To maximize the sample size included in the path analysis, the model was fitted using a maximum likelihood estimation method with robust standard errors (estimation method MLR in Mplus), and a χ2 difference test was conducted after removing or adding a path to ensure improved fit. Analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Mplus Version 8.4, and p < 0.05 was used to denote statistical significance.

RESULTS

Path analyses of donation anxiety, intention, and behavior

Path analysis was used to examine donor self-efficacy and attitude as potential indirect mediators of the relationship between baseline donor anxiety and subsequent donation intention. Figure 1a illustrates the results of the final model after elimination of the non-significant path from anxiety to intention. This model had a strong fit to the data [RMSEA = 0.011 with 90% CI (0.000, 0.027); CFI = 0.998; SRMR = 0.019], and indicates that the relationship between higher anxiety and reduced donation intention is completely mediated by lower self-efficacy and donation attitude ratings. A total of 50.7% of the variance in donation intention was accounted for by both mediators.

Figure 1.

Path analysis of the relationships among donation anxiety, self-efficacy, attitude, intention, and behavior. Significant pathways with associated standardized coefficients are illustrated, with the exception of covariate paths from interventions which are not illustrated for clarity.

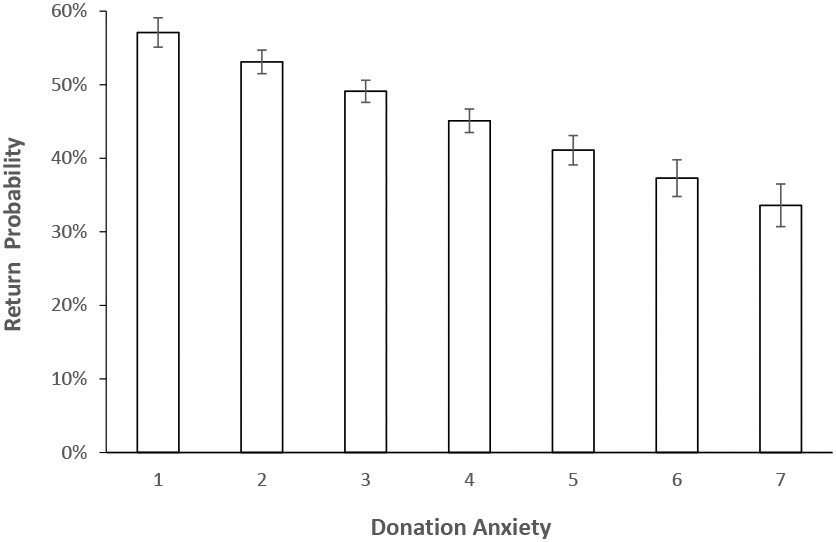

As shown in Figure 1b, addition of donation attempt (yes/no) over the next 14 months as the dependent variable revealed 1) a positive relationship between intention and behavior, 2) a direct negative relationship between anxiety and donation attempt, and 3) an indirect negative relationship between anxiety and donation behavior via lower intention ratings. Figure 2 shows that 57% of donors with the lowest anxiety rating were predicted to make a return attempt as compared to only 34% for those with the highest anxiety rating.

Figure 2.

Estimated predicted probability (and standard error) of an attempted donation during the 14-month follow-up as a function of baseline donation anxiety.

Path analyses of fear of blood draw, intention, and behavior

Path analysis was used to examine donor self-efficacy and attitude as potential indirect mediators of the relationship between baseline fear of having blood drawn and subsequent donation intention. Figure 3a illustrates the results of the final model after elimination of the non-significant path from fear of having blood drawn to intention. This model had a strong fit to the data [RMSEA = 0.004 with 90% CI (0.000, 0.024); CFI = 1.000; SRMR = 0.018], and indicates that the relationship between higher fear of having blood drawn and reduced donation intention is completely mediated by lower self-efficacy and donation attitude ratings. A total of 50.7% of the variance in donation intention was accounted for by both mediators.

Figure 3.

Path analysis of the relationships among fear of blood draw, self-efficacy, attitude, intention, and behavior. Significant pathways with associated standardized coefficients are illustrated, with the exception of covariate paths from interventions which are not illustrated for clarity.

As shown in Figure 3b, addition of donation attempt (yes/no) over the next 14 months as the dependent variable revealed 1) a positive relationship between intention and behavior and 2) an indirect negative relationship between fear of blood draw and donation behavior via lower intention ratings. Figure 4 shows that 52% of donors with the lowest fear of blood draw rating were predicted to make a return attempt as compared to only 34% for those with the highest fear rating.

Figure 4.

Estimated predicted probability (and standard error) of an attempted donation during the 14-month follow-up as a function of baseline fear of having blood drawn.

Path analyses of anxiety, fear of blood draw, intention, and behavior

Path analysis was used to examine donor self-efficacy and attitude as potential indirect mediators of the relationship between baseline anxiety and fear of blood draws on subsequent donation intention. Figure 5a illustrates the results of the final model after elimination of the non-significant paths from anxiety and fear of having blood drawn to intention. This model had a strong fit to the data [RMSEA = 0.007 with 90% CI (0.000, 0.021); CFI = 0.999; SRMR = 0.020], and indicates that the relationships between higher anxiety and fear of having blood drawn and reduced donation intention are completely mediated by lower self-efficacy and donation attitude ratings. A total of 50.8% of the variance in donation intention was accounted for by both mediators.

Figure 5.

Path analysis of the relationships among anxiety, fear of blood draw, self-efficacy, attitude, intention, and behavior. Significant pathways with associated standardized coefficients are illustrated, with the exception of covariate paths from interventions which are not illustrated for clarity.

As shown in Figure 5b, addition of donation attempt (yes/no) over the next 14 months as the dependent variable revealed 1) a positive relationship between intention and behavior and 2) a direct negative relationship between anxiety and donation attempt, and 3) indirect negative relationships between anxiety and fear of blood draw with donation behavior via lower intention ratings.

DISCUSSION

The present findings support a growing body of evidence that donor fear and anxiety are associated with an increased risk of attrition from the donor pool.5-7,20 The findings are also consistent with those of Gilchrist and colleagues,13 in that we confirmed that the relationship between fear/anxiety and donation intention is statistically mediated by donor confidence and attitudes. That is, individuals with more fear and anxiety are less confident in their ability to donate blood and, as a consequence of both elevated fear and lower confidence, more negative in their attitude towards blood donation. Further, and not surprisingly, less confidence and more negative attitudes are each associated with lower donation intention. Given the observation that both fear and anxiety are significant contributors to these relationships when entered in the same model (see Figure 5), it is important to reiterate the distinction between these constructs. As measured in this study, anxiety represents a broad or diffuse apprehension about future blood donation, whereas our measure of fear was specific to concerns about the experience of having blood drawn.

The current study also extends the existing literature in several important respects. First, because we assessed both donation intention and behavior, we were able to demonstrate that fear and anxiety not only reduce intentions to give but also reduce actual donation behavior. Indeed, there was a 60% relative decrease in donation behavior when comparing the most anxious donors (34% returned) versus the least anxious donors (57% returned). Interestingly, whereas our models indicated that the influence of fear on reduced donations was fully mediated by lower self-efficacy and attitude ratings, in contrast anxiety exerted both direct and indirect (via self-efficacy and attitude) negative effects on donation behavior. Thus, efforts to bolster donor self-efficacy and attitude might be expected to eliminate donor attrition associated with fear of blood draw, and to reduce but not completely eliminate attrition related to donation anxiety. A second, related contribution of the current study was the use of a longitudinal design. Specifically, in contrast to a cross-sectional design, where all variables are assessed at approximately the same time, the present study used a sequential assessment of baseline fear and anxiety, followed by assessment of self-efficacy and attitude shortly before the donors’ next eligibility to provide a whole blood donation, and then examined donation behavior over a full year of eligibility. Relative to a cross-sectional design, demonstration of a mediational effect of self-efficacy and attitude in this longitudinal design provides stronger support for these constructs as potential psychological mechanisms that can explain the influence of fear and anxiety on donation behavior. A third significant contribution of the current study is the demonstration of these relationships in a large sample of first time blood donors, which reinforces existing evidence that donation-related fear and anxiety are present even among those who have made the decision to donate blood8 and suggests that if such concerns are left unaddressed they can deter our newest recruits from remaining in the donor pool. Finally, the present results also demonstrated that both fear of blood draw ratings and anxiety ratings were retained in a model where both constructs were included at the same time, indicating that each of these constructs can contribute unique variance in the explanation of donor self-efficacy and attitude. These findings suggest that it would be best to address not only generic donation anxiety, but also any specific fears (e.g., needles, pain, blood, fainting) in an effort to maximize donor confidence, attitude, and intentions.

A major implication of the current findings is that novice donors have fear and anxiety that can deter future donation attempts, hence it seems reasonable to consider adaptations of current blood collection practices to acknowledge concerns and provide support for fearful donors. Whereas some may be hesitant to ask donors about their fear based on a belief that such conversations could increase the risk of a negative donation experience, evidence suggests that asking about fear does not increase the risk of vasovagal reactions.6,10-12 Whereas the exact form of donor fear and anxiety screening will need to be decided by each blood collection agency, one approach that combines simplicity and limited interference with ongoing procedures would be to ask a single fear question during the health screen (i.e., “How afraid are you of having blood drawn?”) and apply a cut-off score to decide when to intervene. We suggest a liberal cut-off for first-time donors (i.e., anything greater than “not at all afraid”), but a more conservative threshold for experienced donors, particularly if they lack a history of vasovagal reactions to blood donation. With respect to how to intervene, two recent studies demonstrated that very brief interventions that address fear immediately before donation can enhance the experience of both whole blood21,22 and plasma22 donors. Ideally, this on-site approach would be combined with additional efforts to reach prospective donors with educational materials on how to cope with donation-related fears as these have been shown to reduce anxiety and increase confidence and attendance among prospective donors.23-27

Although strengths of the present study include recruitment of a relatively large and diverse sample of first-time blood donors, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although participants are all first time New York Blood Center donors, they may have had donation experience with a different blood collection organization that they did not report. Fortunately, this is unlikely for most participants given their young age and residence within the New York Blood Center catchment area. A second limitation is that our recording of follow-up donation attempts is restricted to those made with the New York Blood Center. It is possible that some participants may have moved during the follow-up interval and donated with another blood collection organization, and this would not be reflected in our data. A third issue is the fact that our measure of fear was not obtained in the donation environment, but via an online survey administered approximately one week after donation. Ideally, fear should be assessed in closer temporal and physical proximity to the fear-eliciting stimulus, hence future studies would be advised to follow the lead of prior work that has obtained fear ratings as part of the donor health screen.6,10-12 Finally, whereas the vast majority of participants completed the study and follow-up period prior to COVID-19 pandemic, those who were recruited after January 2019 would have had less opportunity to make a repeat donation at a school-based blood drive due to the cancellation of in-person high school and college classes in the New York areas as of March 2020.

In sum, a longitudinal assessment of first-time donors indicates that fear and anxiety exist as negatives influences on donation intention and behavior, and that these effects are mediated by lower donor confidence and more negative donation attitudes. Given the importance of retaining new blood donors, it is suggested that all new donors be assessed for fear and anxiety and appropriate strategies be provided to address their concerns, bolster their confidence and attitudes, and ultimately promote their long-term retention.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation matrix for all variables. Pearson r values are reported for the correlations among the continuous variables (1-5), and Spearman rho values are reported for correlations with the dichotomous variable of donation attempt (6). All correlations are significant at p < 0.001.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | 3.19 (1.96) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 2. Fear | 0.83 (0.92) | .719 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 3. Self-Efficacy | 6.02 (1.01) | −.242 | −.216 | --- | --- | --- |

| 4. Attitude | 5.99 (0.95) | −.488 | −.442 | .528 | --- | --- |

| 5. Intention | 6.25 (1.15) | −.267 | −.238 | .621 | .623 | --- |

| 6. Donation Attempt | 50.0% | −.123 | −.113 | .202 | .177 | .262 |

Acknowledgments:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL127766. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors certify that they have no conflicts of interest or financial involvement with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Labus JS, France CR, Taylor BK. Vasovagal reactions in volunteer blood donors: Analyzing the predictive power of the medical fears survey. Int J Behav Med 2000;7: 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masser BM, White KM, Hyde MK, Terry DJ, Robinson NG. Predicting blood donation intentions and behavior among Australian blood donors: testing an extended theory of planned behavior model. Transfusion 2009;49: 320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemmens KP, Abraham C, Ruiter RA, Veldhuizen IJ, Dehing CJ, Bos AE, Schaalma HP. Modelling antecedents of blood donation motivation among non-donors of varying age and education. Br J Psychol 2009;100: 71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hupfer ME, Taylor DW, Letwin JA. Understanding Canadian student motivations and beliefs about giving blood. Transfusion 2005;45: 149–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.France CR, France JL, Wissel ME, Ditto B, Dickert T, Himawan LK. Donor anxiety, needle pain, and syncopal reactions combine to determine retention: a path analysis of two-year donor return data. Transfusion 2013;53: 1992–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.France CR, France JL, Carlson BW, Himawan LK, Yunuba Stephens K, Frame-Brown T, Venable GA, Menitove JE. Fear of blood draws, vasovagal reactions, and retention among high school donors. Transfusion 2014;54: 918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.France CR, France JL, Himawan LK, Lux P, McCullough J. Donation related fears predict vasovagal reactions and donor attrition among high school donors. Transfusion 2021;61: 102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.France CR, France JL. Fear of donation-related stimuli is reported across different levels of donation experience. Transfusion 2018;58: 113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.France CR, France JL. Estimating the risk of blood donation fainting for self versus others: the moderating effect of fear. Transfusion 2019;59: 2039–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.France CR, France JL, Conatser R, Lux P, McCullough J, Erickson Y. Predonation fears identify young donors at risk for vasovagal reactions. Transfusion 2019;59: 2870–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.France CR, France JL, Himawan LK, Stephens KY, Frame-Brown TA, Venable GA, Menitove JE. How afraid are you of having blood drawn from your arm? A simple fear question predicts vasovagal reactions without causing them among high school donors. Transfusion 2013;53: 315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.France CR, France JL, Kowalsky JM, Ellis GD, Copley DM, Geneser A, Frame-Brown T, Venable G, Graham D, Shipley P, Menitove JE. Assessment of donor fear enhances prediction of presyncopal symptoms among volunteer blood donors. Transfusion 2012;52: 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilchrist PT, Masser BM, Horsley K, Ditto B. Predicting blood donation intention: the importance of fear. Transfusion 2019;59: 3666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masser BM, Bednall TC, White KM, Terry D. Predicting the retention of first-time donors using an extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Transfusion 2012;52: 1303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheeran P Intention-behaviour relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology 2002;12: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.France CR, France JL, Carlson BW, Frye V, Duffy L, Kessler DA, Rebosa M, Shaz BH. Applying self-determination theory to the blood donation context: The blood donor competence, autonomy, and relatedness enhancement (Blood Donor CARE) trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2017;53: 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.France CR, France JL, Himawan LK, Fox KR, Livitz IE, Ankawi B, Slepian PM, Kowalsky JM, Duffy L, Kessler DA, Rebosa M, Rehmani S, Frye V, Shaz BH. Results from the blood donor competence, autonomy, and relatedness enhancement (blood donor CARE) randomized trial. Transfusion 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42: 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, Consortium RE. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ditto B, France CR. Vasovagal symptoms mediate the relationship between predonation anxiety and subsequent blood donation in female volunteers. Transfusion 2006;46: 1006–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.France CR, France JL, Kowalsky JM, Conatser R, Duffy L, Barnofsky N, Kessler D, Shaz B. A randomized controlled trial of a tablet-based intervention to address predonation fears among high school donors. Transfusion 2020;60: 1450–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilchrist PT, Thijsen A, Masser BM, France CR, Davison TE. Improving the donation experience and reducing venipuncture pain by addressing fears among whole-blood and plasma donors. Transfusion 2021;61: 2107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masser B, France CR, Foot J, Rozsa A, Hayman J, Waller D, Hunder E. Improving first-time donor attendance rates through the use of enhanced donor preparation materials. Transfusion 2016;56: 1628–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.France CR, France JL, Kowalsky JM, Copley DM, Lewis KN, Ellis GD, McGlone ST, Sinclair KS. A Web-based approach to blood donor preparation. Transfusion 2013;53: 328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.France CR, France JL, Wissel ME, Kowalsky JM, Bolinger EM, Huckins JL. Enhancing blood donation intentions using multimedia donor education materials. Transfusion 2011;51: 1796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.France CR, France JL, Kowalsky JM, Cornett TL. Education in donation coping strategies encourages individuals to give blood: further evaluation of a donor recruitment brochure. Transfusion 2010;50: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.France CR, Montalva R, France JL, Trost Z. Enhancing attitudes and intentions in prospective blood donors: evaluation of a new donor recruitment brochure. Transfusion 2008;48: 526–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.France CR, France JL, Carlson BW, Kessler DA, Rebosa M, Shaz BH, Madden K, Carey PM, Fox KR, Livitz IE, Ankawi B, Slepian PM. A brief motivational interview with action and coping planning components enhances motivational autonomy among volunteer blood donors. Transfusion 2016;56: 1636–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.France JL, Kowalsky JM, France CR, McGlone ST, Himawan LK, Kessler DA, Shaz BH. Development of common metrics for donation attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention for the blood donation context. Transfusion 2014;54: 839–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]