Abstract

Background

Individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) and fungal airway infection may present with fungal bronchitis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) or may appear unaffected despite fungal detection. We sought to characterize people with CF with frequent detection of fungi from airway samples and determine clinical outcomes.

Methods

This retrospective study included individuals with CF with ≥4 lower airway cultures over a 2‐year baseline period and ≥2 years of follow‐up. We defined two groups: ≤1 positive fungus culture (rare) or ≥2 positive cultures during baseline (frequent). Clinical characteristics and outcomes were determined.

Results

Between 2004 and 2016, 294 individuals met inclusion with 62% classified as rare and 38% as frequent fungi during baseline. Median follow‐up was 6 years (range: 2–9 years). Aspergillus fumigatus was the most common fungal species detected. Individuals with frequent fungi were older (13.7 vs. 11.7 years, p = .02) and more likely to have Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (35% vs. 17%, p < .001) at baseline, but did not differ in lung function or ABPA diagnosis. During follow‐up, those with frequent fungi were more likely to have chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. maltophilia. Individuals with ABPA and frequent fungi had the highest rates of co‐infection and co‐morbidities, and a trend towards more rapid lung function decline.

Discussion

Fungal infection in CF was associated with frequent P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia co‐infection even in those without ABPA. Individuals with frequent fungi and ABPA had worse outcomes, highlighting the potential contribution of fungi to CF pulmonary disease.

Keywords: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, allergy, aspergillus, fungus, infection

1. INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that affects more than 85,000 individuals worldwide. 1 Despite significant advances in therapy, people with CF continue to experience high rates of morbidity and mortality due to pulmonary disease. 2 People with CF are prone to inspissated airway mucus with subsequent pulmonary endobronchitis caused by CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein dysfunction that impairs chloride and bicarbonate secretion at the airway surface layer. Individuals subsequently develop chronic airway infections, episodic pulmonary exacerbations, and progressive airway injury. 3 , 4 Bacterial pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa are well known contributors to disease progression and exacerbations. Fungi are also often isolated from lower airway samples (sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [BAL]) but their clinical impact is less well understood, especially when cultured in the presence of concomitant bacteria. 5

Fungal infection in people with CF has a wide spectrum of both detection frequency and disease manifestations. Fungal detection may be transient, intermittent, or chronic. Disease manifestations range from acute or chronic fungal bronchitis with pulmonary exacerbation; sensitization to fungal allergens; and allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis most often caused by aspergillosis (allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, ABPA). 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Others with fungal positive cultures may appear unaffected without worsening clinical signs or symptoms, or with symptoms attributable to other causes. ABPA is at the severe end of presentations and is a known allergic inflammatory process in reaction to Aspergillus antigen causing airway mucus impaction and obstruction.

Despite the possible associations, detection of fungus is not a requirement for an ABPA diagnosis. 6 , 10 , 11 The impact of persistent fungal infection in the absence of ABPA on disease progression is less clear. Some studies have shown decrease in lung function over time in people with CF and Aspergillus infection as well as other worsening clinical outcomes. 7 Other studies, however, have shown little clinical difference in those with or without fungi. 12 Fungal detection has also been associated with P. aeruginosa co‐infection and with inhaled antibiotic treatments often used to treat Pseudomonas, possibly due to changes in microbial competition within the community. 13 , 14 Despite these studies, the contribution of fungi to CF lung disease progression remains under debate with few clinical guidelines upon isolation. Thus, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to compare clinical outcomes and disease course between individuals with CF with and without frequent fungal detection from airway samples, while accounting for chronic P. aeruginosa infection and ABPA diagnosis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patient selection and clinical characteristics

People with CF seen at Children's Hospital Colorado (CHCO) from 2004 to 2016 were identified by electronic medical records. Individuals were included in the study if they had a diagnosis of CF (sweat chloride ≥60 mmol/L and/or two disease‐causing CFTR gene variants) as established by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines and at least 4 airway fungal cultures (sputum, BAL, and/or fungus positive oropharyngeal [OP] culture) over 2 consecutive years (baseline period), and at least 2 years of follow‐up clinical data available after baseline. 15 Information included was patient demographics, CF diagnostic criteria, genotype, comorbidities including ABPA, asthma, and CF related diabetes (CFRD) present during the baseline or follow‐up periods, lung function starting at age 5, growth parameters, microbiology culture results, and laboratory results for immunoglobulin E (IgE) and complete blood count with eosinophils. ABPA, CFRD, and Asthma diagnoses were based off diagnoses codes, registry data, and database documentation of this diagnosis. Microbiologic culture data before baseline period was captured starting in 2004. CFTR modulators prescribed were recorded, however availability of approved modulators was limited during the study time. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple IRB (#15‐2376).

2.2. Cultures

Airway samples were collected as part of clinical care and processed at the CHCO clinical microbiology laboratory following standard CF culture procedures. Bacterial and fungal cultures are performed routinely on all sputum and BAL samples. 16 OP cultures are not routinely plated on fungal media in our institution's microbiology lab, therefore result from OP cultures were only included in the analysis if positive for fungi. Two or more positive cultures within 1 month of each other were considered a single positive culture. Fungal detection included any reported fungus species by our clinical lab, including the labels “yeast” and “fungus,” which in some instances were reported. Of note, the microbiology lab does not routinely report Candida sp. growth on these cultures.

2.3. Defining infection status

Initially we compared patients with no fungal positive cultures, rare fungus (one positive), intermittent fungi (≥2 positive but <50% positive), or chronic fungi (>2 positive and at least 50% positive); however, given the limited group sample sizes we chose to dichotomize fungal exposure to agree with previously published literature and to provide greater power for group comparisons. 7 , 17 Results from cultures over the 2‐year baseline period were used to categorize individuals as either having rare fungus, defined as ≤1 positive fungal culture in the baseline period and no positive fungal cultures recorded before baseline, or frequent fungi, defined as having 2 or more positive fungal cultures in the baseline period. Definitions were based upon adaptations from previously published fungal and chronic bacterial infection studies in CF. 7 , 17 Given that we defined fungal exposure for individuals in the baseline period, individuals could transition groups during the follow‐up period (e.g., those classified as rare could later meet critieria for frequent fungal infection). Participants were considered rare during follow‐up if they had 1 positive culture and considered frequent if they met criteria (2 positive cultures) in any year of follow‐up. Chronic P. aeruginosa status was defined by a modified Leed's criteria of >50% positive cultures for P. aeruginosa over at least one 12‐month period. Patients were defined as chronic at baseline if they met these criteria for at least one 12‐month period in the baseline study period (and similarly defined during the follow‐up period). 18 “Ever P. aeruginosa” status during the follow‐up period was defined as isolating P. aeruginosa at any point in time, regardless of frequency or year.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Summary descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations or median and range for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Characteristics such as body mass index (BMI) that were repeated over the study period were averaged over their individual baseline and follow‐up time. Differences between airway fungi groups were determined using ANOVAs or Chi‐squared tests depending on the distribution. Given the potential impact of ABPA on clinical status, we also compared individuals with rare and frequent fungi by ABPA status, comparing characteristics and outcomes across the four groups. Multiple linear mixed effects regression models allowing for random slope and intercept per patient were used to assess percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (ppFEV1) over time by fungal exposure group using maximum likelihood estimation. ppFEV1 over follow‐up time was standardized within patient by taking their average ppFEV1 during their baseline. The first model only included time and fungal exposure group, the second model adjusted for chronic P. aeruginosa and ABPA status, and the third and fourth models compared ppFEV1 by airway fungi and adjusted for P. aeruginosa stratified by ABPA status. Models were re‐run adjusting for transition from one group to another in the follow‐up period to assess any change in association or inference. All three‐way and two‐way interactions between time with fungal status, ABPA, chronic or ever P. aeruginosa were assessed. Statistical significance was set at a Type I error rate of 0.05. All data cleaning, summaries, and testing were done using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Population characteristics during the baseline period

During the study period, clinical data from 712 patients with CF were available, of whom 294 met inclusion criteria (Figure S1). The majority of individuals who did not meet these criteria did not have enough sputum or BAL fungal cultures available. At baseline, 113 patients (38%) were categorized as having frequent fungi and 181 patients had rare fungus (62%). Patient characteristics during the 2‐year baseline period are shown in Table 1. Aspergillus sp. was the most common fungus isolated in the baseline period for both the frequent and rare groups, with Aspergillus fumigatus being the most common. Individuals categorized as frequent fungi were older (median 13.7 vs. 11.7 years, p = .02) and were more frequently co‐infected with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (35% vs. 17%, p < .001) compared to those with rare fungus. We did not detect differences in baseline ppFEV1, BMI percentile or rates of ABPA between groups. Fewer individuals with frequent fungi were diagnosed with asthma compared to the rare fungus group (14.9% vs. 25.6%, p = .04).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics during baseline period categorized by fungal infection status

| Rare fungus (N = 181) | Frequent fungus (N = 113) | Total (N = 294) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Age, yrs, median [range] | 11.7 [1.8–42.7] | 13.7 [4.9–52.4] | 12.4 [1.8–52.4] | .02 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 86 (48) | 49 (43) | 135 (46) | .49 |

| Race, n (%) | .52 | |||

| Black | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.4) | |

| White | 177 (97.8) | 110 (97.3) | 287 (97.6) | |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 24 (13.3) | 10 (8.8) | 34 (11.6) | .25 |

| Genotype, n (%) | .94 | |||

| F508del/F508del | 95 (52.5) | 61 (54.0) | 156 (53.1) | |

| F508del/other | 71 (39.4) | 42 (36.8) | 113 (38.4) | |

| Other/other | 15 (8.3) | 10 (8.8) | 25 (8.5) | |

| ppFEV1, mean (SD) | 86 (17) | 83 (18) | 85 (18) | .19 |

| BMI percentile, mean (SD) | 42.22 (26.45) | 40.11 (25.27) | 41.41 (26.98) | .50 |

| Co‐morbidities n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 46 (25.6) | 17 (14.9) | 63 (21.4) | .04 |

| ABPA | 9 (5.0) | 6 (5.3) | 15 (5.1) | .81 |

| CFRD | 21 (11.7) | 10 (8.7) | 31 (10.5) | .32 |

| IGE, kUA/L mean (SD) | 180 (401) | 239 (414) | 200 (405) | .34 |

| Cultures during baseline period (sputum/BAL/positive OP), n, median [range] | 4 [4–17] | 5.5 [4–14] | 4 [4–17] | <.01 |

| Fungal positive cultures during baseline period, n, median [range] | 0 [0, 1] | 3 [2, 8] | 1 [0, 8] | <.01 |

| Co‐infections, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic Pa infection | 59 (32.8) | 37 (32.7) | 96 (32.8) | .99 |

| Ever Pa positive | 76 (42.2) | 62 (54.9) | 138 (47.1) | .04 |

| S. maltophilia | 31 (17.1) | 40 (35.4) | 71 (24.1) | <.01 |

| Nontuberculous mycobacterium | 19 (10.6) | 10 (8.8) | 29 (9.9) | .63 |

| MSSA | 139 (76.8) | 88 (77.9) | 227 (77.2) | .74 |

| MRSA | 23 (12.8) | 16 (14.2) | 39 (13.3) | .74 |

| Fungus isolated during baseline, n (%) individualsa | ||||

| Aspergillus | 23 (12.8) | 85 (75.2) | 108 (36.9) | <.001 |

| A. fumigatis | 9 (5.0) | 44 (38.9) | 53 (18.0) | <.001 |

| A. flavus | 2 (1.1) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (1.7) | .317 |

| A. niger | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | .205 |

| A. terreus | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) | 4 (1.4) | .011 |

| Scedosporium | 3 (1.7) | 15 (13.3) | 18 (6.1) | <.001 |

| Otherb | 28 (15.5) | 37 (17.7) | 65 (22.1) | .009 |

| None | 127 (70.2) | 0 (0) | 127 (43.2) | <.001 |

Note: p = value determined by ANOVAs or Chi‐squared tests, p < .05 statistiffcally significant.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; BMI, body mass index; CFRD, CF related diabetes; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; OP, oropharyngeal swab; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; ppFEV1, percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s; S. maltophilia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Not all species level data was available in our database.

Other baseline fungus includes: Acremoniun (n = 1), Alternaria species (n = 3), Bipolaris sp. (n = 1), Conidiobolus species (n = 1), Dematiaceous species (n = 2), Exophiala species (n = 1), Fungus, unknown species (n = 6), Fusarium species (n = 3), Geotrichum sp (n = 1), HYPHOMYCETES species (n = 1), Mucor (n = 1), Scopulariopsis species (n = 4), Trichoderma species (n = 2), Yeast (n = 1), penecillium (n = 40).

3.2. Patient characteristics during the follow‐up period

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes during follow‐up period are shown in Table 2. There was no difference in the amount of follow‐up time for those with frequent fungi compared to rare [mean (SD) 4.3 (2.4) vs. 4.3 (2.2) years, p = .70]. Those with frequent fungi had more respiratory cultures during this period compared to the rare group although the range was large [median (range) 10 (2–76) vs. 7 (2–64), respectively, p = .02]. We did not detect differences in mean ppFEV1, BMI percentile, co‐morbidities or IgE concentrations between groups. The groups had a similar umber of admissions for pulmonary exacerbations was approaching significance with more in the frequent group, although the difference was small (1.84 per year in frequent vs. 1.57 per year in rare, p = .09). Individuals with frequent fungi were more likely to have chronic P. aeruginosa (51% vs. 37%, p = .01) and to ever have cultured P. aeruginosa (73% vs. 52%, p < .001) compared to those with rare fungus. Individuals with frequent fungi were also more likely to have S. maltophilia (47% vs. 30%, p = .004) consistent with baseline findings. There were no differences observed in frequency of MRSA and MSSA between groups.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes during follow‐up study period

| Rare (N = 181) | Frequent (N = 113) | Total (N = 294) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in follow‐up study period, years, mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.4) | 4.3 (2.4) | .70 |

| Cultures during follow‐up (sputum/BAL/positive OP), n, median [range] | 7 [2–64] | 10 [2–76] | 8 [2–76] | .02 |

| Fungal positive cultures during follow‐up period, n, median [range] | 1 [0, 27] | 3 [0, 54] | 2 [0, 54] | <.01 |

| ppFEV1, mean (SD) | 81.11 (19.29) | 77.91 (20.70) | 79.88 (19.87) | .18 |

| BMI Percentile, mean (SD) | 42.50 (26.27) | 39.11 (24.96) | 41.19 (25.78) | .27 |

| Diagnosed with co‐morbidities during follow‐up, n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 62 (34.4) | 46 (40.4) | 108 (36.7) | .04 |

| ABPA | 18 (10.0) | 14 (12.3) | 32 (10.9) | .81 |

| CFRD | 40 (22.2) | 30 (26.3) | 70 (23.8) | .32 |

| Ever diagnosed with co‐morbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 108 (60) | 63 (55) | 171 (58) | .51 |

| ABPA | 27 (15) | 20 (18) | 47 (16) | .53 |

| CFRD | 61 (34) | 40 (35) | 101 (34) | .77 |

| During follow‐up co‐infections, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic Pa | 67 (37.2) | 58 (51.3) | 125 (42.7) | .02 |

| Ever Pa positive | 94 (51.9) | 82 (72.6) | 176 (59.9) | <.01 |

| S. maltophilia | 54 (29.8) | 53 (46.9) | 107 (36.4) | <.01 |

| Nontuberculous mycobacterium | 30 (16.7) | 22 (19.5) | 52 (17.7) | .81 |

| MSSA | 147 (81.2) | 89 (78.8) | 236 (80.3) | .61 |

| MRSA | 44 (24.4) | 32 (28.3) | 76 (25.9) | .75 |

| IGE, kUA/L mean (SD) | 249 (459) | 299 (616) | 266 (516) | .52 |

| Eosinophils, absolute 103/mcl, mean (SD) | 0.25 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.25 (0.18) | .86 |

| Transitioned | .01 | |||

| Stayed in the same group | 116 (64.1) | 88 (77.9) | 204 (69.4) | |

| Transitioned groups | 65 (35.9) | 25 (22.1) | 90 (30.6) | |

| Admissions, per year, mean (SD) | 1.57 (0.79) | 1.84 (1.27) | 1.67 (1.01) | .09 |

Note: p = value determined by ANOVAs or Chi‐squared tests, p < .05 statistically significant. Ever Pa Positive was defined as ever isolating Pa on at least one occasion during the follow‐up period. Group during follow‐up was defined as the number of individuals that continued to have at least one rare or frequent year in the follow‐up period.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; BMI, body mass index; CFRD, CF related diabetes; IgE, immunoglobulin E; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; OP, oropharyngeal swab; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; ppFEV1, percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s; S. maltophilia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

3.3. Relationship between change in fungal status and co‐infections

Of the individuals classifed as rare at baseline, 65 (36%) subsequently had at least 1 year of frequent fungal infections during the study period, while 116 (64%) remained rare throughout the study period. Of the individuals classifed as frequent at baseline, 25 (22%) did not isolate fungus during the follow‐up period. We examined co‐infections with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia in patients who transitioned from rare to frequent fungi. Of the individuals who started in the rare group and transitioned to frequent (n = 65), 17 had P. aeruginosa positive cultures. In this group, 71% (12/17) had P. aeruginosa detected before fungal positive culture whereas 29% (5/17) had a positive fungal culture before P. aeruginosa detection. Of the 38 individuals with S. maltophilia, 45% (17/38) had S. maltophilia detected before fungal positive culture whereas 55% (21/38) had a positive fungal culture before S. maltophilia detection.

3.4. Relationships of fungal status with changes in lung function

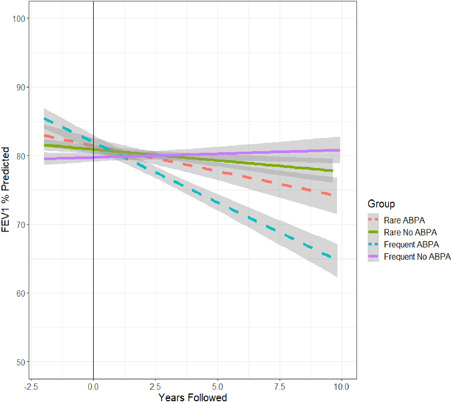

Average rate of ppFEV1 decline during follow‐up was not statistically different between the frequent fungi group compared to the rare group (−1.85% vs. −1.61% per year, respectively, Figure S2). Using regression modeling, there was no difference between fungal groups, even when controlling for ABPA, chronic P. aeruginosa, and transitioning across groups. Interestingly, in this model, when comparing only those with ABPA and frequent fungal infection to those with ABPA and rare fungal infection, fungal status was significant, showing that those with ABPA and frequent fungal infection had lower lung function at each time point compared to those with ABPA and rare fungal infection (p = .047).

3.5. Individuals with ABPA and frequent fungal infection have signs of worse clinical outcomes

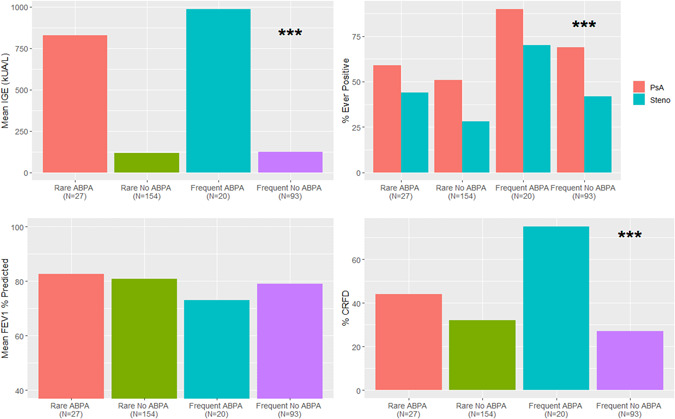

We compared the clinical characteristics at baseline and during follow‐up of individuals by ABPA and fungal status: ABPA/frequent (N = 20, 7%), ABPA/rare (N = 27, 9%), no ABPA/frequent (N = 93, 32%), and no ABPA/rare (N = 154, 52%). Individuals ever diagnosed with ABPA were, on average, followed longer during the study period than those without ABPA regardless of fungal status [mean (SD) 5.7 years (2.3) vs. 4.0 (2.7) years, respectively, p < .001]. Table 3 shows clinical characteristics for the four groups. Figure 1 shows comparisons in ppFEV1, diagnoses of CFRD, IgE measurements, and co‐infection with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia between groups.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics stratified by ABPA and fungus group

| Rare + ABPA (N = 27) | Rare no ABPA (N = 154) | Frequent + ABPA (N = 20) | Frequent no ABPA (N = 93) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) follow‐up, median (range) | 15.1 9.4–20.5 | 15.4 6.4–46.1 | 16.0 13.2–55.2 | 16.7 7.9–35.6 | .03 |

| Average ppFEV1 follow‐up, mean (SD) | 82.6 (14.9) | 80.8 (20) | 73.1 (18) | 79 (21.1) | .33 |

| BMI Percentile, mean (SD) | 43 (24.4) | 42.4 (26.7) | 42.2 (28) | 38.5 (24.4) | .67 |

| Co‐morbidities during follow‐up time, n (%) | |||||

| Asthma | 15 (55.6) | 47 (30.7) | 16 (80.0) | 30 (31.9) | .04 |

| CFRD | 8 (44.4) | 32 (32.0) | 11 (75.0) | 19 (26.6) | .79 |

| Co‐morbidities ever diagnosed, n (%) | |||||

| Asthma | 22 (81.5) | 86 (55.8) | 18 (90.0) | 45 (48.4) | <.01 |

| CFRD | 12 (44.4) | 49 (31.8) | 15 (75.0) | 25 (26.9) | <.01 |

| Co‐infections, n (%) | |||||

| Chronic Pa | 8 (29.6) | 59 (38.6) | 12 (60.0) | 46 (49.5) | .07 |

| Ever Pa positive | 16 (59.3) | 78 (50.6) | 18 (90.0) | 64 (68.8) | <.01 |

| S. maltophilia | 12 (44.4) | 42 (27.5) | 14 (70.0) | 39 (41.5) | <.01 |

| IgE, kUA/L mean (SD) | 830 (696) | 117 (240) | 987 (1115) | 123 (154) | <.01 |

| Eosinophils, absolute 103/mcl, mean (SD) | 0.39 (0.28) | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.39 (0.24) | 0.21 (0.10) | <.01 |

| Admissions, per year, mean (SD) | 1.58 (0.59) | 1.56 (0.84) | 1.97 (0.78) | 1.78 (1.44) | .35 |

Note: p = value determined by ANOVAs or Chi‐squared tests, p < .05 statistically significant. Ever Pa Positive was defined as ever isolating Pa on at least one occasion during the follow‐up period. Group during follow‐up was defined as the number of individuals that continued to have at least one rare or frequent year in the follow‐up period.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; BMI, body mass index; CFRD, CF related diabetes; IgE, immunoglobulin E; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; OP, oropharyngeal swab; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; ppFEV1, percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s; S. maltophilia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Figure 1.

Comparison during follow‐up study period for individuals classified by fungal and ABPA status of (A) mean IgE ng/ml, (B) co‐infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, (C) mean ppFEV1 and (D) percent with CFRD. ***p < .001. ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CFRD, CF related diabetes; IgE, immunoglobulin E [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Individuals with frequent fungi and ABPA tended to have more chronic infection with P. aeruginosa compared to the other three groups (p = .07). While not statistically significant, those with frequent fungal infection and ABPA clinically had the lowest average ppFEV1 of the four groups during the follow‐up period (Table 3) and highest annual rate of decline in ppFEV1 (−2.3% vs. ABPA/rare −1.32%, no ABPA/frequent −1.76% and no ABPA/rare −1.68% per year [p values of interactions = 0.19, 0.5, 0.43], Figure 2). Those with ABPA had higher IgE and serum eosinophils regardless of fungal status; IgE was highest in the ABPA/frequent group.

Figure 2.

Average ppFEV1 per year, showing decline in ppFEV1 from baseline (left of the line) to study period (right of the line) by rare and frequent fungal grouping and ABPA status. Linear lines with 95% shaded confidence intervals are fit to average over time for each group. ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; ppFEV1, predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, we found that individuals with CF and frequent fungal detection had higher rates of co‐infection with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia compared to those with no or rare detection of fungi. Other clinical characteristics and outcomes did not differ between those with frequent versus rare fungi including frequency of ABPA diagnosis and nutritional status. Lung function (ppFEV1) and lung function decline were also similar between groups including after controlling for chronic P. aeruginosa and ABPA.

In individuals with ABPA however, frequent fungal detection was associated with significantly lower lung function (ppFEV1) compared to those with ABPA and rare fungal detection. Individuals with ABPA/frequent fungi had significantly higher rates of co‐infection with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia; more CFRD diagnoses; and higher IgE values compared to those with ABPA/rare fungi and compared to those without ABPA regardless of fungal categorization. Individuals with ABPA/frequent fungi also had a trend towards more rapid lung function decline during follow‐up. Clinically, this is notable, yet given the lack of statistically significance, more studies are needed to understand these observations. Interestingly, we found equal proportions of ABPA among the rare and frequent fungal groups.

As expected, those with ABPA had higher absolute eosinophils and IgE values, markers of T‐helper 2 cells (Th2), typical of allergic or hypersensitivity responses. We did not detect a difference in eosinophils or IgE between the frequent and rare fungal groups. Interestingly, 60% of the rare group and 55% of the frequent group had a diagnosis of asthma over the entire study, which is higher than the general population as well as previously published literature on patients with CF. 19 , 20 Furthermore, in the baseline period, more individuals in the rare group had asthma, while in the follow‐up period, more individuals in the frequent group had asthma. While the follow‐up period had more time to collect data and is likely more robust, the significance of this finding is unclear. Asthma, ABPA, and CFRD diagnoses were documented based upon coding in our electronic medical record and pose expected limitation within this retrospective study; thus diagnoses may reflect institutional practices, regional effects and allergens, or another unknown confounding variable. Using diagnosis codes for asthma and other comorbidities in this study has an expected limitation.

Individuals with frequent fungal infection had higher rates of chronic P. aeruginosa co‐infection and more P. aeruginosa detection overall during follow‐up compared to the rare fungus group. A similar pattern was seen in those with ABPA and frequent fungi, having the highest proportion of individuals with chronic P. aeruginosa infection when compared to the other three groups. This may be related to the use of aggressive antibiotic therapy in P. aeruginosa eradication protocols, allowing for shifts in biodiversity by creating a less competitive airway environment for fungal species. 11 , 21 Other studies and authors have suggested that biofilms created by P. aeruginosa and/or Aspergillus may be initially favorable and synergistic for fungal spores to germinate. 22 However, other studies have shown that P. aeruginosa biofilms and their attach mechanisms actually inhibit Aspergillus growth, favoring the competition theory. 23 , 24 , 25 There was no significant differences in MRSA co‐infection among any of the groups, another organism possibly related to more frequent therapies and driven by microbial management. 26 In the follow‐up period, people in our cohort with rare fungi more often isolated P. aeruginosa before later fungal detection, rather than isolating fungi first, supporting the role of antimicrobial therapies and/or a synergistic environment in fungal growth, although our numbers were small.

S. maltophilia was associated with more frequent fungal infection at baseline and during follow‐up. It also had a different longitudinal pattern than P. aeruginosa with almost 50% of individuals isolating S. maltophilia before fungus. Furthermore, we found that individuals with S. maltophilia and frequent fungus were older and had lower average lung function by almost 10% compared to individuals with rare fungus without S. maltophilia. While one investigation in the associations with fungi and S. maltophilia have been seen in people with CF and liver disease, the literature is still lacking in understanding of how the organisms are related. 27 Previous studies investigating biofilm formation and antibiosis between S. maltophilia and A. fumigatus demonstrated some competition as well as co‐infection. 28 Our findings are both supportive of and contrary to existing data, but imply an association between the acquisition of fungus and subsequent infection with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia. Given this, more research is needed to identify associated risk factors as well as cause and effect relationships between these fungi and gram‐negative pathogens in people with CF.

The association between fungus and lung disease progression has been examined previously in CF. Studies have shown lower ppFEV1 in those with chronic fungal infection, yet the definition of chronic varies widely in the literature. Some investigators have adapted criteria similar to P. aeruginosa classifications, however, there are many genera and species of fungus that make definitions difficult. Furthermore, given the need for sputum or BAL for fungal culture, detection of fungi is dependent on the person's ability to expectorate, further complicating classification, prevalence, and disease severity. This likely explains the higher rates of bacteria and fungus isolation in our cohort when compared to registry data. 29

Most studies in the literature focus on Aspergillus or Aspergillus fumigatus specifically, excluding other fungal genera. 5 , 7 , 17 We included all fungi (with the exception of Candida, i.e., not routinely reported by our clinical laboratory) as genera such as Scedosporium may also contribute to CF lung disease. 30 , 31 However, over 70% of fungal positive cultures in our cohort grew Aspergillus. Our study was larger than most and included follow‐up for a median of 6 years.

Our findings agree with the literature in finding higher morbidity and worse outcomes in those with ABPA. However, our study was one of the few comparing ABPA to fungal frequency both as a co‐variate and as a separate group. 6 , 7 By doing so, we found that those with both ABPA and frequent fungus appeared to have more severe disease despite the fact that the presence of fungus in the sputum is not required for ABPA diagnosis. This dynamic emphasizes the importance of fungus on inflammation in the CF airway, yet how the pathophysiology of fungal infections needs further investigation.

This study has several limitations. Most importantly, this was a single center, retrospective study so we are unable to determine causation between fungal disease, ABPA and outcomes. Given electronic medical record limitations, we only evaluated culture results as early as 2004. It is possible that some individuals isolated fungi before this and thus meet other fungal group classification. Fungi are also difficult to isolate in culture. 21 , 32 Given this, there are likely individuals who have fungi that were not detected and may account for those without ABPA in the absence of positive fungal cultures. We tried to account for this by requiring at least 4 lower airway cultures for analysis. It is likely that most of the individuals in this study could spontaneously expectorate, and thus were likely more severely impacted compared to those who could not expectorate. Given this, it is possible that there is an overrepresentation of individuals infected with P. aeruginosa and other organisms associated with morbidity and increased sputum production. This may limit generalizability, however, we required sputum from each subject as to not bias the rare group. This may explain the higher rates of fungi and bacterial pathogens given a more reliable sample than throat swabs. Furthermore, individuals in the frequent fungal group had significantly more cultures compared to those with rare fungi which may lead to surveillance bias. Prospective longitudinal studies are needed to assess the acquisition of fungus in real time and how use of antibiotics and co‐infections contribute. Mechanistic studies are also needed to explore the interactions of fungi and other organisms in the CF airway as well as inflammatory host‐responses, specific biomarkers of fungal disease and allergy, and clinical studies investigating characteristics regarding the development of ABPA.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We found associations between frequent fungal detection and bacterial co‐infection with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia, but not MSSA or MRSA in people with CF. In those with a diagnosis of ABPA, frequent fungal detection was associated with worse clinical outcomes with high rates of comorbidities, co‐infections with pathogenic bacteria, and worse lung disease. However, we did not detect a similar association between fungal detection and clinical outcomes when controlling for ABPA diagnosis. Currently, there is no consensus on whether to routinely obtain fungal cultures in people with CF. Future prospective studies are needed to determine the relationship between fungal infection, bacterial co‐infections and development of ABPA, which would inform future recommendations for monitoring for fungi.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Edith T. Zemanick personal fees from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, site clinical trial support from Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Savara Pharmaceuticals Inc., and material agreements and consulting contracts with Calithera Biosciences and Concert Pharmaceuticals outside the scope of the submitted work. Emily M. DeBoer is a consultant and stockholder for EvoEndoscopy, not related to this project.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Thomas Spencer Poore: conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); writing original draft (equal); writing review & editing (equal). Maxene Meier: data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); software (equal); writing original draft (equal); writing review & editing (equal). John Brinton: supervision (equal); writing review & editing (equal). Stacey L. Martiniano: conceptualization (equal); methodology (equal); writing review & editing (equal). Scott D Sagel: writing review & editing (equal). Emily M DeBoer: writing review & editing (equal). Brandie Wagner: writing review & editing (equal). Edith T Zemanick: conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); supervision (equal); writing original draft (equal); writing review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation POORE20D0 (TSP), ZEMANI17Y5 (ETZ), ZEMANI20Y7 (ETZ, MM), NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535.

Poore TS, Meier M, Towler E, et al. Clinical characteristics of people with cystic fibrosis and frequent fungal infection. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2022;57:152‐161. 10.1002/ppul.25741

REFERENCES

- 1. Bell SC, Mall MA, Gutierrez H, et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:65‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elborn JS. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2016;388:2519‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:918‐951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Welsh MJ. Origins of cystic fibrosis lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1574‐1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tracy MC, Moss RB. The myriad challenges of respiratory fungal infection in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:S75‐S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janahi IA, Rehman A, Al‐Naimi AR. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Ann Thorac Med. 2017;12:74‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amin R, Dupuis A, Aaron SD, Ratjen F. The effect of chronic infection with Aspergillus fumigatus on lung function and hospitalization in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2010;137:171‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baxter CG, Dunn G, Jones AM, et al. Novel immunologic classification of aspergillosis in adult cystic fibrosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(560‐6):e10‐e566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. King J, Brunel SF, Warris A. Aspergillus infections in cystic fibrosis. J Infect. 2016;72(Suppl:):S50‐S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Antunes J, Fernandes A, Borrego LM, Leiria‐Pinto P, Cavaco J. Cystic fibrosis, atopy, asthma and ABPA. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2010;38:278‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sudfeld CR, Dasenbrook EC, Merz WG, Carroll KC, Boyle MP. Prevalence and risk factors for recovery of filamentous fungi in individuals with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:110‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Vrankrijker AM, van der Ent CK, van Berkhout FT, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus colonization in cystic fibrosis: implications for lung function? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1381‐1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burns JL, Van Dalfsen JM, Shawar RM, et al. Effect of chronic intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin on respiratory microbial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1190‐1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keown K, Reid A, Moore JE, Taggart CC, Downey DG. Coinfection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aspergillus fumigatus in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farrell PM, White TB, Ren CL, et al. Diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis: consensus Guidelines from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. J Pediatr. 2017;181S(S4‐S15):e1‐S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saiman L, Siegel J, Cystic, Fibrosis F. Infection control recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis: microbiology, important pathogens, and infection control practices to prevent patient‐to‐patient transmission. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:S6‐S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heltshe SL, Mayer‐Hamblett N, Burns JL, et al. Network GIotCFFTD: Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients with G551D‐CFTR treated with ivacaftor. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:703‐712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee TW, Brownlee KG, Conway SP, Denton M, Littlewood JM. Evaluation of a new definition for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros. 2003;2:29‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kent BD, Lane SJ, van Beek EJ, Dodd JD, Costello RW, Tiddens HA. Asthma and cystic fibrosis: a tangled web. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:205‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nielsen AO, Qayum S, Bouchelouche PN, Laursen LC, Dahl R, Dahl M. Risk of asthma in heterozygous carriers for cystic fibrosis: a meta‐analysis. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15:563‐567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nguyen LD, Viscogliosi E, Delhaes L. The lung mycobiome: an emerging field of the human respiratory microbiome. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaur S, Singh S. Biofilm formation by Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2014;52:2‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mowat E, Rajendran R, Williams C, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their small diffusible extracellular molecules inhibit Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:96‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira JA, Penner JC, Moss RB, et al. Inhibition of Aspergillus fumigatus and Its Biofilm by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on the source, phenotype and growth conditions of the bacterium. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Penner JC, Ferreira JAG, Secor PR, et al. Pf4 bacteriophage produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits Aspergillus fumigatus metabolism via iron sequestration. Microbiology. 2016;162:1583‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akil N, Muhlebach MS. Biology and management of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:S64‐S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cabaret O, Bonnal C, Canoui‐Poitrine F, et al. Concomitant presence of Aspergillus fumigatus and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in the respiratory tract: a new risk for patients with liver disease? J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:414‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Melloul E, Roisin L, Durieux MF, et al. Interactions of Aspergillus fumigatus and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in an in vitro Mixed Biofilm Model: does the strain matter? Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foundation CF : 2019 Patient Registry Annual Data Report. 2020.

- 30. Cimon B, Carrere J, Vinatier JF, Chazalette JP, Chabasse D, Bouchara JP. Clinical significance of Scedosporium apiospermum in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:53‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chotirmall SH, McElvaney NG. Fungi in the cystic fibrosis lung: bystanders or pathogens? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;52:161‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coron N, Pihet M, Frealle E, et al. Toward the standardization of mycological examination of sputum samples in cystic fibrosis: results from a french multicenter prospective study. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:101‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information.