Abstract

Background:

Health care worker (HCW) training using standardized patient actors (SPs) is an evidence-based approach for improving patient-provider interactions. We evaluated whether SP training among HCWs in Western Kenya improved quality of PrEP counseling for adolescent girls and young women (AGYW).

Methods:

We conducted a 2-day SP training intervention among HCWs providing PrEP counseling for AGYW. Six trained SPs role-played one encounter each with HCWs following scripts depicting common PrEP-seeking scenarios. SPs used checklists to report and discuss domains of adherence to national PrEP guidelines, communication, and interpersonal skills using validated scales after each encounter. HCWs presented to each case in random order. Overall and domain-specific mean score percentages were compared between the first and subsequent case encounters using generalized linear models, clustering by HCW.

Results:

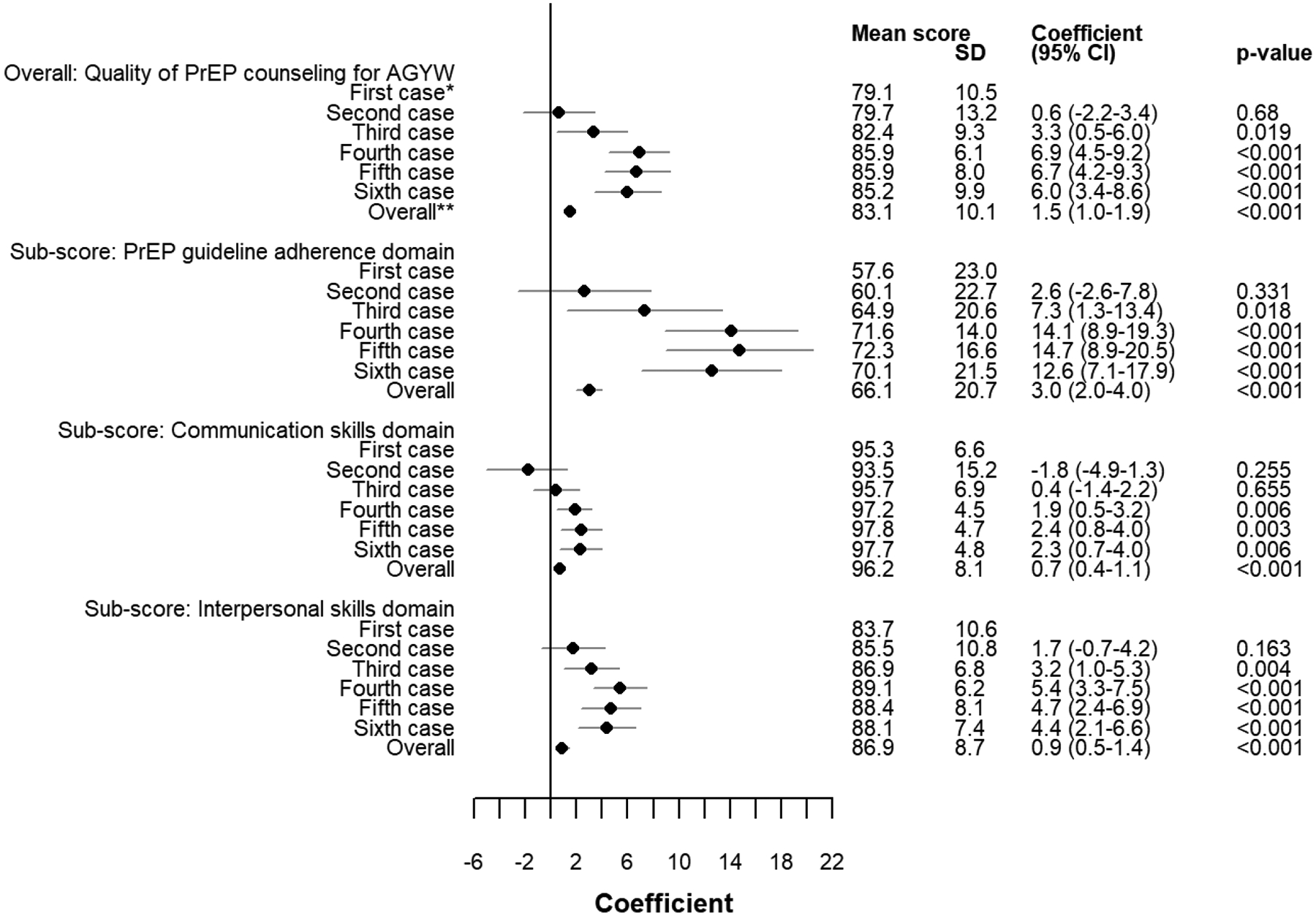

During 564 training cases among 94 HCW, the overall mean quality of PrEP counseling score was 83.1 (standard deviation [SD]:10.1); scores improved over the course of the 6 encounters (p<0.001). Compared to the first case encounter, mean scores for the fourth were significantly higher (79.1 vs. 85.9, p<0.001). Mean scores plateaued from the fourth to the sixth case (85.2). While HCWs demonstrated high baseline communication (95.3) and interpersonal skills (83.7), adherence to PrEP guidelines at baseline was suboptimal (57.6). By the 4th case, scores increased significantly (p<0.001) for all domains.

Conclusions:

SP training improved PrEP counseling overall and in domains of interpersonal skills, use of guidelines, and communication with AGYW and could be useful in efforts to improve quality of PrEP counseling for AGYW.

Keywords: PrEP, Standardized patients, Adolescent girls, Young women, Training, Healthcare workers

Background

In high HIV-burden settings in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) age 15–24 are at high risk for HIV infection, with eight times the risk of males in the same age range.1 Globally, an estimated 320,000 AGYW newly acquired HIV in 2019.2 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective at preventing HIV transmission when adherence is optimal,3–8 therefore a promising HIV prevention approach for AGYW.

PrEP uptake and adherence among AGYW in SSA is insufficient to achieve global HIV elimination targets.9–11 Poor quality of counseling interactions with health care workers (HCW) can dissuade AGYW from engaging in sexual and reproductive health services, including HIV prevention.12–17 AGYW experience judgmental attitudes by HCWs and lack of confidentiality, discouraging initiation or continuation of PrEP.12–14 Concurrently, HCWs report gaps in their knowledge and skills to effectively serve AGYW, particularly with HIV prevention.14,16–18 It is critical to improve the quality of PrEP counseling for AGYW to optimize uptake.

Standardized patient actors (SPs) are utilized within clinical training as an evidence-based approach to improve provider competency and quality of care.19–26 SPs pose as patients, evaluating provider compliance with clinical guidelines. Provider competencies in numerous topics, including quality of care,21,22,26 have been improved by SPs across diverse settings, including South Africa and Kenya.19,20,25,27

We implemented a training intervention using SPs posing as AGYW in role-played clinical scenarios to improve quality of PrEP counseling by HCWs. We evaluated changes in quality of PrEP services provided by HCW across multiple role-played scenarios to identify the number of SP sessions needed to achieve sufficient competency in PrEP counseling for AGYW.

Methods

Study setting and population

This analysis is nested in a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an SP-led training intervention: “Simulated Patients to Improve PrEP Counseling for Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Kenya” (“PrIYA-SP”). The study protocol was previously published.28 The PrIYA-SP study was conducted within 24 large family planning and maternal health facilities providing PrEP counseling and care services to AGYW in Kisumu County, Kenya. All HCWs who were current employees at the study sites, were at least 18 years old, able to provide informed consent, and whose job duties included provision of PrEP services to AGYW were approached for enrollment. Our analysis includes data from HCWs who completed the training intervention.

Standardized patient-led training intervention

The training intervention was delivered through two-day training events involving groups of 5–10 HCWs from intervention sites. The training started with didactic lectures covering adolescent health and development, Kenya national guidelines for HIV prevention and PrEP delivery29, and how to structure a high-quality patient-provider encounter. Interactive group activities included a values clarification and patient-centered communication. These activities offered opportunities for HCW to practice reducing the influence of their personal beliefs within patient care and engaging patients in their own health decision-making processes. Training materials were informed by frameworks for clinical communication skills and high quality patient-provider interactions,24,30–37 and Kenyan national guidelines for PrEP delivery.29

Following didactic training, HCWS completed an applied component consisting of role-play sessions with trained SPs enacting case-scripted scenarios depicting common experiences of AGYW seeking PrEP in the region. SPs were trained by an expert trainer according to the Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE) standards of best practice38, which involved standardized performance review. Case scripts were developed in a standard format by a team comprised of a SP expert, Kenyan and US clinicians, and AGYW researchers who worked together to depict common challenges faced by PrEP-seeking AGYW within prior studies conducted by the group.19,39,40 Cases involved themes including but not limited to sexual activity among young adolescents, transactional sex, multiple concurrent partners, and having an HIV-positive partner. HCWs rotated through six cases (one SP per case) in random order (Supplemental Table 1). A brief conversation between the SP and HCW followed each encounter where SPs shared HCW strengths and areas for improvement based on a standard, tablet-based checklist. Training events concluded with a review of video-recordings of SP role-play case encounters during a group debriefing session where study staff facilitated synthesis of feedback from peers and SPs.

Data collection procedures

Study staff administered surveys to HCWs to ascertain demographics; training history; beliefs about HIV,32 AGYW, and PrEP;18 self-reported competency in PrEP counseling to AGYW; and self-reported knowledge of PrEP services. After each role-play case encounter with an HCW, SPs used a tablet-based checklist to record perceptions of the interaction and guide discussion with the HCW (Appendix 1).

Outcome measures

The outcome of PrEP counseling quality by HCWs during the SP encounters was defined by three domains: adherence to PrEP delivery guidelines, communication skills, and interpersonal skills.41 Sub-scores for the three domains were combined to produce an overall score. Adherence to guidelines was evaluated with a checklist containing 12 questions using binary ‘done/not done’ response options to indicate whether a PrEP counselling message was delivered by the provider during the case encounter according to the Kenyan guidelines (sub-score range: 0–12) (Appendix 1).29 Communication skills were assessed with seven questions using Likert response options (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree) (sub-score range: 0–28), which were informed by the Kalamazoo Consensus statement on essential elements of communication30,42 and adapted from the Adolescent Patient-Provider Interaction Scale37 to suit the study setting (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81)34,43 We assessed HCW interpersonal skills within case encounters using a validated tool developed to evaluate medical graduates during standardized patient encounters.44 The IPS tool evaluates 14 items under four dimensions (interviewing and collecting information, counseling and delivering information, rapport, and personal manner) using Likert response options (item score range: 1 – 4; sub-score range: 14–56).

Statistical analysis

We described demographic, employment, and training characteristics of the HCW using counts and proportions or median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Mean sub-scores per domain were calculated by dividing each raw sub-score by its respective total possible score and rescaling by 100. Overall quality was computed by combining those three values, then dividing by three to achieve the weighted mean score.

To evaluate change in overall quality of PrEP counseling score for each case encounter compared to the first case encounter, we used generalized linear models with a Gaussian distribution and identity link including case encounter order as a categorical variable, clustering by HCW and adjusting for time since initial training event (days) to account for temporal changes in training implementation. Analyses were repeated for each domain sub-score. Analyses were performed in Stata version 15.0.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics Research Committee and University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee. Approval was additionally obtained by the Kisumu County Department of Health and health administrators in the health facilities involved. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Healthcare worker characteristics

Among the 94 HCW from 12 health facilities who completed the SP-led training intervention, over half (59%) were female and median age was 32 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 29–36) (Table 1). Over a third (37%) of HCW were stationed within HIV Comprehensive Care Clinics, and 37% worked in Maternal and Child Health clinics. Most HCW (83%) completed college as their highest level of education. Just over half (54%) were nurses, and 41% were clinical officers. HCWs had a median of 4 years of experience providing HIV prevention services to AGYW (IQR: 2–7).

Table 1.

Characteristics of healthcare workers participating in SP-led training intervention (n=94)

| Characteristics | N or Median | % or IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32 | 29–36 |

| Sex (Female) | 55 | 59% |

| Clinical station | ||

| CCC | 35 | 37% |

| MCH | 35 | 37% |

| PMTCT/HTS | 8 | 9% |

| Other /(FP) | 16 | 17% |

| Highest education achieved | ||

| College | 78 | 83% |

| University | 15 | 16% |

| Primary/Secondary | 1 | 1% |

| Employment title | ||

| Nurse | 51 | 54% |

| Clinical officer | 38 | 40% |

| Other/(Adherence counselor) | 5 | 5% |

| Number of years at current clinic | 2 | 1–4 |

| Number of years of experience in HIV prevention services | 4 | 2–8 |

| Number of years working with AGYW | 4 | 2–7 |

| Number of AGYW clients served per week | 4 | 3–6 |

| Ever received training in HIV prevention for AGYW | 56 | 60% |

| Ever received training in prescribing PrEP | 67 | 71% |

| Ever received training in prescribing PrEP to AGYW (n=67) | 35 | 37% |

Quality of PrEP counseling for AGYW during training intervention

During 564 individual training encounters among 94 HCW, the overall mean score was 83.1 (standard deviation [SD]:10.1) and scores improved after sequential encounters (p<0.001) (Figure 1) taking place over the course of the 2-day training. The first case encounter had the lowest mean score of 79.1 (SD:10.5). Statistically significant improvement was achieved by the third compared to the first case (82.4 vs. 79.1, coef: 3.28, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.93–4.84), adjusting for time since initial training event. The fourth case had the highest mean score (85.9, SD:6.1). Compared to the first case encounter, mean scores for the fourth were 6.9 points higher (fourth vs. first case coef:6.9, 95%CI: 4.5–9.2), and mean scores plateaued from the fourth to the sixth case (85.2).

Figure 1. Quality of PrEP counseling overall mean score percent* and results from linear regression models (n=94 HCW, n=564 case scripts).

*Case script coefficients from generalized linear models with a Gaussian distribution and identity link, clustering by individual, case order included as categorical variable, adjusted for number of days since initial training event

**”Overall” coefficient from generalized linear model with Gaussian distribution and identity link, clustering by individual, case order included as a continuous variable, adjusted for number of days since initial training event

Sub-domains of PrEP counseling for AGYW

The domain of HCW adherence to PrEP guidelines had the lowest mean score of 66.1 across all encounters. The mean sub-score significantly improved by 14 points from the first to the fourth case (fourth vs. first case coef:14.1, 95%CI: 8.9–19.3, p<0.001), and mean sub-scores plateaued from the fourth to sixth case.

We saw a similar pattern in the mean sub-scores for the communication skills and interpersonal skills domains. HCWs had the highest mean score for the communication skills domain with 96.2 overall. We observed statistically significant improvement from the first to the fourth case (97.2 vs. 95.3, coef: 1.85, 95% CI: 0.53–3.16) which plateaued through the sixth case. Overall, HCW demonstrated mean score percent of 86.9 for interpersonal skills. The highest sub-score for interpersonal skills was achieved in the fourth case (89.1) which was about five points higher than the first case (coef: 5.4, 95% CI: 3.3–7.5). In sensitivity analyses, we did not find differences in quality of PrEP counseling by HCW characteristics.

Discussion

In our training evaluation with over 500 role-play interactions, we found that quality of PrEP counseling for AGYW improved after HCW training involving standardized patient actors. HCW competency in adherence to national PrEP guidelines, communication skills, and interpersonal skills improved after only three encounters, were highest after four, and plateaued after that. These findings indicate that a shorter training with four cases may be sufficient to elicit improvement in PrEP counseling for AGYW, allowing for lower resource allocation to achieve sustained improvement in counseling quality.

Quality of PrEP counseling assessed in the initial SP role-play sessions was high among this sample of HCW, including domains of communication and interpersonal skills. However, adherence to national PrEP guidelines for AGYW counseling sessions was relatively low. Adherence to PrEP guidelines showed the greatest improvement, yet HCW only reached a mean score of 72, demonstrating further room for improvement.45 All domains showed statistically significant improvement following SP-led training encounters.

SPs are especially useful at assessing and improving patient-centered communication – a key component of quality of care.46 Global guidelines from groups such as the World Health Organization and US. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)47,48 increasingly call for a focus on provider competency and patient-centered communication as key components of adolescent and HIV care provision.49,50 On the path toward global HIV elimination, PEPFAR promotes patient-centered services47 that are hospitable and friendly48 as an important last mile approach to ensuring hard-to-reach key populations receive HIV prevention and treatment. As high-HIV burden countries rapidly expand efforts to promote PrEP uptake among groups with high HIV risk, such as AGYW, SPs could be engaged within clinical training to operationalize policy and guideline implementation.

Our study was limited by the self-reported nature of SP checklists used to quantify quality of PrEP counseling. However, SPs were trained in ASPE best practices and underwent expert performance evaluation. Implementation of the intervention may have changed over time from the first to the final event, thus we adjusted our results for time elapsed. HCWs were aware they were being evaluated during training encounters, which may have influenced their performance. To address this, our ongoing trial utilizes unannounced SPs, or “mystery shoppers” to measure quality outcomes in real-world clinical settings within intervention and control sites.

In conclusion, simulated patient training improved provider guideline adherence and interpersonal communication skills in PrEP counseling for AGYW. Improvement was achieved following at least three simulated case encounters between HCWs and SPs, and highest quality was seen after four case encounters. Findings suggest SP training is useful to strengthen provider PrEP knowledge and interpersonal skills to engage and counsel AGYW on PrEP for HIV prevention. The forthcoming PrIYA-SP trial will further inform effectiveness of this SP-led training intervention in improving quality of PrEP counseling for AGYW. As sub-Saharan Africa strives toward global HIV elimination targets, additional research is needed to determine whether gains in quality care subsequently result in improved PrEP uptake and continuation.

Supplementary Material

Sources of support:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number R01 HD094630.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: No authors declare a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS data 2019 | UNAIDS. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-UNAIDS-data

- 3.Guidance on Pre-Exposure Oral Prophylaxis (PrEP) for Serodiscordant Couples, Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex with Men at High Risk of HIV. World Health Organization; 2012. Accessed March 23, 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23586123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson KA, Baeten JM, Mugo NR, Bekker LG, Celum CL, Heffron R. Tenofovir-based oral preexposure prophylaxis prevents HIV infection among women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan FM, Delany-Moretlwe S, Sanders EJ, et al. PrEP implementation research in Africa: What is new? J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(7(Suppl 6)). doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar MS, Kripke K, Haberer J, et al. Understanding and measuring uptake and coverage of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Health. 2018;15(6):513–521. doi: 10.1071/SH18061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, Baeten JM, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: from efficacy trials to delivery. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S4). doi: 10.1002/jia2.25298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bender SS, Fulbright YK. Content analysis: A review of perceived barriers to sexual and reproductive health services by young people. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care. 2013;18(3):159–167. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2013.776672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, Van Den Broek N. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):172. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagey JM, Akama E, Ayieko J, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Patel RC. Barriers and facilitators adolescent females living with HIV face in accessing contraceptive services: A qualitative assessment of providers’ perceptions in western Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1). doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Lavussa JA, Quinney D, Hofman JJ, Van Den Broek N. Sexual reproductive health service provision to young people in Kenya; Health service providers’ experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):476. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidia KK, Mupambireyi Z, Cluver L, Ndhlovu CE, Borok M, Ferrand RA. HIV status disclosure to perinatally-infected adolescents in Zimbabwe: A qualitative study of adolescent and healthcare worker perspectives. PLoS One. 2014;9(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wachira J, Naanyu V, Genberg B, et al. Health facility barriers to HIV linkage and retention in Western Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):646. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0646-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilgrim N, Jani N, Mathur S, et al. Provider perspectives on PrEP for adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: The role of provider biases and quality of care. PLoS One. 2018;13(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler PK, Marumo E, Jed SL, et al. A national evaluation using standardised patient actors to assess STI services in public sector clinical sentinel surveillance facilities in South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(4):247–252. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson KS, Mugo C, Bukusi D, et al. Simulated patient encounters to improve adolescent retention in HIV care in Kenya: Study protocol of a stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2266-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels B, Dolinger A, Bedoya G, et al. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: A pilot, cross-sectional study with international comparisons. BMJ Glob Heal. 2017;2(2):e000333. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wafula F, Dolinger A, Daniels B, et al. Examining the Quality of Medicines at Kenyan Healthcare Facilities: A Validation of an Alternative Post-Market Surveillance Model That Uses Standardized Patients. Drugs - Real World Outcomes. 2017;4(1):53–63. doi: 10.1007/s40801-016-0100-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilbur K, Elmubark A, Shabana S. Systematic review of standardized patient use in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2018;38(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker DM, Holme F, Zelek ST, et al. A process evaluation of PRONTO simulation training for obstetric and neonatal emergency response teams in Guatemala. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1). doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0401-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker DM, Cohen SR, Fritz J, et al. Impact evaluation of PRONTO Mexico: A simulation-based program in obstetric and neonatal emergencies and team training. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das J, Kwan A, Daniels B, et al. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of tuberculosis care: A pilot, cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(11):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00077-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mugo C, Wilson K, Wagner AD, et al. Pilot evaluation of a standardized patient actor training intervention to improve HIV care for adolescents and young adults in Kenya. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2019;31(10):1250–1254. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen A, Wilson KS, Kinuthia J, et al. Standardised patient encounters to improve quality of counselling for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in Kenya: Study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NASCOP. Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: A Rapid Advice; 2014. Accessed July 8, 2019. http://healthservices.uonbi.ac.ke/node/1963

- 30.Makoul G Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: The kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390–393. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mugwanya KK, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, et al. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis delivery in routine family planning clinics: A feasibility programmatic evaluation in Kenya. Geng EH, ed. PLOS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyblade L, Jain A, Benkirane M, et al. A brief, standardized tool for measuring HIV-related stigma among health facility staff: results of field testing in China, Dominica, Egypt, Kenya, Puerto Rico and St. Christopher & Nevis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2). doi: 10.7448/ias.16.3.18718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rider EA, Hinrichs MM, Lown BA. A model for communication skills assessment across the undergraduate curriculum. Med Teach. 2006;28(5):e127–e134. doi: 10.1080/01421590600726540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong LML, de Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: A review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahn JA, Emans SJ, Goodman E. Measurement of young women’s attitudes about communication with providers regarding Papanicolaou smears. J Adolesc Heal. 2001;29(5):344–351. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00254-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness Questionaire (PPPC) #04–1 - Centre for Studies in Family Medicine - Western University. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.schulich.uwo.ca/familymedicine/research/csfm/publications/working_papers/the patient perception of patient centerdness questionnaire_pppc.html

- 37.ER W, JD K, GM W, et al. Development of a new Adolescent Patient-Provider Interaction Scale (APPIS) for youth at risk for STDs/HIV. J Adolesc Heal. 2006;38(6):753.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis KL, Bohnert CA, Gammon WL, et al. The Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE) Standards of Best Practice (SOBP). Adv Simul 2017 21. 2017;2(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/S41077-017-0043-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escudero JN, Dettinger JC, Pintye J, et al. Community Perceptions About Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Kenya. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020;31(6):669–677. doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pintye J, O’Malley G, Kinuthia J, et al. Influences on Early Discontinuation and Persistence of Daily Oral PrEP Use Among Kenyan Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Qualitative Evaluation From a PrEP Implementation Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(4):e83–e89. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen A, Wilson KS, Kinuthia J, et al. Standardised patient encounters to improve quality of counselling for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in Kenya: study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rider EA, Nawotniak RH. A practical guide to teaching and assessing the ACGME core competencies. Published online 2010:394.

- 43.Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, Beach MC. Higher Quality Communication and Relationships are Associated with Improved Patient Engagement in HIV Care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):362. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0B013E318295B86A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Zanten M, Boulet JR, McKinley D. Using standardized patients to assess the interpersonal skills of physicians: Six years’ experience with a high-stakes certification examination. Health Commun. 2007;22(3):195–205. doi: 10.1080/10410230701626562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Heal. 2018;6(11):e1196–e1252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paget L, Han P, Nedza S, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: Basic Principles and Expectations. NAM Perspect. 2011;1(6). doi: 10.31478/201106a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.PEPFAR. Guiding Principles for the Next Phase of PEPFAR.

- 48.PEPFAR. Client-Centered HIV Services. Published online 2021.

- 49.Standards for Improving the Quality of Care for Children and Young Adolescents in Health Facilities.

- 50.PEPFAR 2020 Country Operational Plan Guidance for All PEPFAR Countries.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.