Abstract

Introduction:

Opioid/heroin use is an epidemic in the United States (US). Polysubstance use dramatically increases risk of adverse overdose outcomes, versus use of a single substance. Co-use of heroin and cocaine, known as “speedballing,” is associated with higher risk of overdose than use of either alone. It is not known whether co-use relative to use of either alone has increased in the US in recent years at a national level. If so, this may be one contributing factor to the increasing fatality rate associated with the US opioid epidemic. This study investigated the prevalence of use of each and co-use of heroin and cocaine from 2002 to 2017 in the US.

Methods:

Data were drawn from the 2002–2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to estimate prevalence of past-month heroin use, cocaine use, and co-use of heroin and cocaine among Americans ages 12 and older.

Results:

From 2002 to 2017, cocaine use (without heroin) (adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=0.971, 95% confidence interval (0.963, 0.979)) declined overall, though a subsequent quadratic analysis suggested that it began increasing in 2011. In contrast, heroin and cocaine co-use (AOR=1.062 (1.027, 1.099)) and heroin use (without cocaine) (AOR=1.101 (1.070, 1.133)) linearly increased from 2002 to 2017.

Conclusions:

Screening, outreach, clinical treatment, and first responders should be aware of increasing patterns of polysubstance use and the potential implications of co-use of heroin and cocaine on first responders’ intervention and the potential role of increasing exposure to multiple substances on overdose outcomes in the US.

Keywords: heroin, opioid, cocaine, speedball, polysubstance, NSDUH

1. INTRODUCTION

The United States (US) has seen an unprecedented increase in opioid use over the past several decades and an extremely high fatality rate due to opioid/heroin overdose.1,2 Many explanations have been put forth to explain the current epidemic, including expansion of opioid prescriptions, higher purity and cheaper cost of heroin, availability of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, and a decline in the nation’s mental health (e.g., increasing depression).3,4 One potential contributing factor that has received comparably less attention for fatalities is substance co-use, also known as polysubstance use. Indeed, there are mounting data to suggest that overdose is due in large part not only to opioids/heroin alone but to fatal patterns of co-use of opioids/heroin with other illicit substances.5

Polysubstance use is increasing and generally more dangerous than use of a single drug alone, as evidenced by increased mortality rates in overdose cases with more than one identified drug. One particularly lethal combination that has been reported in overdose statistics is “speedballing,” which involves the simultaneous administration of both cocaine and opioids/heroin. The initial stimulating effects of cocaine can mask symptoms of an impending opioid overdose. If co-use of cocaine and opioids/heroin is increasing, this may be one increasingly salient issue requiring attention in both treatment and intervention planning.

The current study investigated the prevalence of past-30-day use of cocaine (without heroin) and heroin (without cocaine) from 2002 to 2017, as well as the co-use of heroin and cocaine, to shed light on whether trends in single use of each and co-use of heroin and cocaine are in parallel or diverging. If the patterns of co-use are increasing, this will alert the need for public health approaches for prevention and outreach centered around co-use.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

Study data were drawn from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public data portal (http://datafiles.samhsa.gov/) for the years 2002 to 2017. The NSDUH provides annual representative, cross-sectional national data on the use of cocaine, heroin and other substances in the US, and is described in depth elsewhere.6 A multistage area probability sample for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia was conducted to represent the male and female civilian non-institutionalized population of the US ages 12 and older. Response rates ranged from 68% to 76%.

The datasets from each year were concatenated, adding a variable for the survey year. Person-level analysis sampling weight for the NSDUH was computed to control for individual-level non-response and was adjusted to ensure consistency with population estimates obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. To use data from the 16 years of the study period, a new weight was created upon aggregating the 16 datasets by dividing the original weight by the number of data sets combined. Further descriptions of the sampling methods and survey techniques for the NSDUH are found elsewhere.6

2.2. Statistical analysis

The prevalence of current (past-30-day) cocaine and heroin use and the associated standard errors among the whole population were calculated for each year from 2002 to 2017. A time trend in the prevalence of current cocaine use (without heroin) was tested using logistic regression with continuous year as the predictor for the linear time trend. The same analyses were then repeated with heroin use (without cocaine) and heroin and cocaine co-use. We further performed a test for quadratic trend on cocaine use (without heroin) due to visual inspection; cocaine use (without heroin) appeared to increase after 2011 following a downward linear trend beginning in 2002. All analyses were conducted in 2019.

3. RESULTS

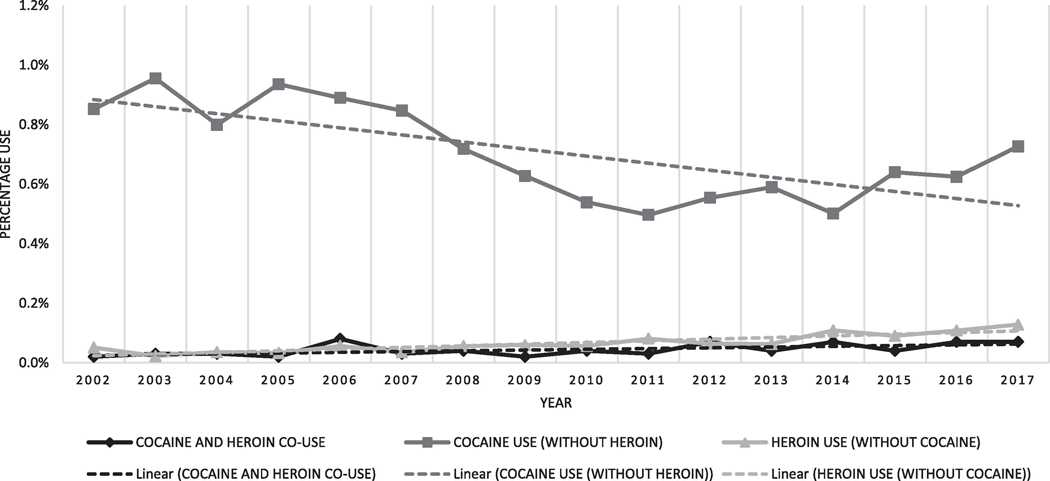

From 2002 to 2017, among those ages 12 and older in the US, cocaine use (without heroin) (adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=0.971 (0.963, 0.979)) declined, whereas heroin and cocaine co-use (AOR=1.062 (1.027, 1.099)) and heroin use (without cocaine) increased ((AOR=1.101 (1.070, 1.133) using tests for linear trends; See Figure 1). Use of cocaine (without heroin) significantly increased from 2011 to 2017 testing for a quadratic trend (p-value <0.0001).

Figure 1.

Cocaine and heroin use in the past month among individuals ages 12+ in the United States, 2002–2017

4. DISCUSSION

Co-use of heroin and cocaine has increased over the past decade. Overdose fatalities including both cocaine and opioids/heroin have also increased since 2010.7 While overdose fatalities involving cocaine declined from 2006 to 2012, cocaine-related overdose fatalities increased from 2012 to 2018, which is consistent with the trends in cocaine use (without heroin) found in the current study.1 Indeed, in 2017, 72.7% of cocaine-involved overdose fatalities also involved opioids/heroin.8 Increasing overdose fatalities that involve polysubstance use, cocaine and heroin specifically, suggest the need for further research focused on patterns of polysubstance use and overdose risk among opioid users.

4.1. Study limitations

Study limitations include absence of information on route of administration and timing of co-administration. Heroin and cocaine use are increasing in the same individuals, though it cannot be confirmed that there is an increase in simultaneous administration (i.e., speedballing) per se. Although the linear pattern was a decline in cocaine use over the study period, it is possible that the later years could reflect an emerging uptick. As additional data become available for 2018 and beyond, we will be able to confirm or refute this potential new upward trend.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In light of the current findings and other evidence of increasing trends in co-use of heroin and cocaine, and the elevated risk of fatal outcomes of overdoses with more than one substance, increased attention should be focused on screening and early intervention in terms of short- and long-term treatment to prevent adverse outcomes associated with overdose. Early intervention and prevention, including education of the risks associated with specific patterns of drug co-use, may be a key toward reducing fatalities associated with an increasing prevalence of polysubstance use.

Highlights.

Cocaine and heroin co-use increased from 2002–2017 in the United States

From 2002–2017, the use of heroin without cocaine increased

The use of cocaine without heroin decreased from 2002–2011 but increased thereafter

Increase in co-use may contribute to higher overdose-attributable mortality

Acknowledgments

Renee D. Goodwin: Funding acquisition; Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

Scott J. Moeller: Funding acquisition; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

Jiaqi Zhu: Software; Formal analysis; Writing - review & editing

Jeremy Yarden: Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

Sarah Ganzhorn: Writing - review & editing

Jill M. Williams: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing - review & editing

Role of Funding Source

Funding was provided by grant DA20892 (Dr. Goodwin) and K01DA037452 (Dr. Moeller) from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse. The funding organization had no role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. 2020. NCHS Data Brief, no 356. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2010–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM, Nash D, Galea S, Goodwin RD. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med. 2018;48(8):1308–1315. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institutes of Health. Overdose Death Rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.[Dataset] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2017. (NSDUH-2002–2016) https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-2017-nid17938. Published 2017. Accessed October 10, 2019. [PubMed]

- 7.Jones CMC, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocaine-related overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):430–432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, Hoots B. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential - United States, 2003–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(17):388–395. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]