Abstract

Background

Foot ulcers are a major complication of diabetes mellitus, often leading to amputation. Growth factors derived from blood platelets, endothelium, or macrophages could potentially be an important treatment for these wounds but they may also confer risks.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of growth factors for foot ulcers in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Search methods

In March 2015 we searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL. There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials in any setting, recruiting people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosed with a foot ulcer. Trials were eligible for inclusion if they compared a growth factor plus standard care (e.g., antibiotic therapy, debridement, wound dressings) versus placebo or no growth factor plus standard care, or compared different growth factors against each other. We considered lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe), complete healing of the foot ulcer, and time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer as the primary outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Independently, we selected randomised clinical trials, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data in duplicate. We estimated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes. We measured statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We subjected our analyses to both fixed‐effect and random‐effects model analyses.

Main results

We identified 28 randomised clinical trials involving 2365 participants. The cause of foot ulcer (neurologic, vascular, or combined) was poorly defined in all trials. The trials were conducted in ten countries. The trials assessed 11 growth factors in 30 comparisons: platelet‐derived wound healing formula, autologous growth factor, allogeneic platelet‐derived growth factor, transforming growth factor β2, arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid peptide matrix, recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin), recombinant human epidermal growth factor, recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor, recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor, recombinant human lactoferrin, and recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor. Topical intervention was the most frequent route of administration. All the trials were underpowered and had a high risk of bias. Pharmaceutical industry sponsored 50% of the trials.

Any growth factor compared with placebo or no growth factor increased the number of participants with complete wound healing (345/657 (52.51%) versus 167/482 (34.64%); RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.31 to 1.73; I2 = 51%, 12 trials; low quality evidence). The result is mainly based on platelet‐derived wound healing formula (36/56 (64.28%) versus 7/27 (25.92%); RR 2.45, 95% 1.27 to 4.74; I2 = 0%, two trials), and recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) (205/428 (47.89%) versus 109/335 (32.53%); RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.76, I2= 74%, five trials).

In terms of lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe), there was no clear evidence of a difference between any growth factor and placebo or no growth factor (19/150 (12.66%) versus 12/69 (17.39%); RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.39; I2 = 0%, two trials; very low quality evidence). One trial involving 55 participants showed no clear evidence of a difference between recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor and placebo in terms of ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.94; P value 0.56, low quality of evidence)

Although 11 trials reported time to complete healing of the foot ulcers in people with diabetes , meta‐analysis was not possible for this outcome due to the unique comparisons within each trial, failure to report data, and high number of withdrawals. Data on quality of life were not reported. Growth factors showed an increasing risk of overall adverse event rate compared with compared with placebo or no growth factor (255/498 (51.20%) versus 169/332 (50.90%); RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96; I2 = 48%; eight trials; low quality evidence). Overall, safety data were poorly reported and adverse events may have been underestimated.

Authors' conclusions

This Cochrane systematic review analysed a heterogeneous group of trials that assessed 11 different growth factors for diabetic foot ulcers. We found evidence suggesting that growth factors may increase the likelihood that people will have complete healing of foot ulcers in people with diabetes. However, this conclusion is based on randomised clinical trials with high risk of systematic errors (bias). Assessment of the quality of the available evidence (GRADE) showed that further trials investigating the effect of growth factors are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn. The safety profiles of the growth factors are unclear. Future trials should be conducted according to SPIRIT statement and reported according to the CONSORT statement by independent investigators and using the Foundation of Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research recommendations.

Keywords: Humans; Amputation, Surgical; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1/complications; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/complications; Diabetic Foot; Diabetic Foot/therapy; Growth Substances; Growth Substances/adverse effects; Growth Substances/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Wound Healing

Plain language summary

Growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers

What are diabetic foot ulcers?

People who suffer from diabetes mellitus (usually referred to as ‘diabetes’) can develop wounds (ulcers) on their feet and ankles. These diabetic foot ulcers can take a long time to heal, and affect quality of life for people with diabetes. In some people, failure of these ulcers to heal can contribute to the need for some level of amputation on the foot. Any treatments that encourage diabetic foot ulcers to heal will be valuable.

What are growth factors?

Growth factors are substances that occur naturally in the body. They promote growth of new cells and healing of wounds. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers with growth factors may improve the healing of ulcers.

The purpose of this review

This Cochrane review tried to identify the benefits and harms of treating diabetic foot ulcers with growth factors in addition to providing standard care (i.e. pressure relief, removal of dead tissue from the wound, infection control and application of dressings).

Findings of this review

The review authors searched the medical literature up to 3 March 2015, and identified 28 relevant medical trials, with a total of 2365 participants. The trials were performed in ten different countries, generally in out‐patient settings. All the trials had low numbers of participants, which makes potential overestimation of benefits and underestimation of harms more likely. Half of the trials were sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry that produces these growth factors.

The trials tested 11 different types of growth factor, usually by applying them to the ulcer surface. Growth factors had no effect on the risk of having one toe or more amputated when compared with either another growth factor, or placebo (inactive fake medicine), or standard care alone (evidence from four trials). However, when compared with placebo or no growth factor, growth factors seemed to make complete healing of ulcers (wound closure) more likely to occur (evidence from 12 trials).

Shortcomings of the trials included in this review

None of the trials reported data on participants’ quality of life. Harms caused by treatments were poorly reported, so the safety profile of growth factors remains unclear.

It is clear that more trials are required to assess the benefits and harms of growth factors in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. These trials should be well‐designed, conducted by independent researchers (not industry‐sponsored), and have large numbers of participants. They should report outcomes that are of interest to patients, such as: how many of the participants’ ulcers healed, and how long the healing took; any level of amputation in the foot; quality of life; ulcer‐free days following treatment; and harms caused by treatment, including whether there are any potential cancer risks.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any growth factor compared with placebo or no growth factor for diabetic foot ulcer.

| Any growth factor compared with placebo or no growth factor for diabetic foot ulcer | ||||||

| Patient or population: foot ulcers in people with diabetes Settings: outpatient Intervention: any growth factor Comparison: placebo or no growth factor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or no intervention | Any growth factor | |||||

| Complete wound closure Follow‐up: 4 to 24 weeks | 346 per 10001 | 523 per 1000 (454 to 599) | RR 1.51 (1.31 to 1.73) | 1316 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | 1.‐ Growth factors investigated included autologous growth factor (1 trial); platelet‐derived wound healing formula (2 trials); recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) (5 trials), recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (2 trials), recombinant human epidermal growth factor (1 trial), and transforming growth factor (1 trial). 2.‐ Trials differed in quality. |

| Lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe) Follow‐up: 8 to 20 weeks | 174 per 10001 | 123 per 1000 (64 to 235) | RR 0.74 (0.39 to 1.39) | 219 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | Platelet‐derived wound healing formula (1 trial), and recombinant human epidermal growth factor (1 trial) |

| Ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (free from any recurrence) Follow‐up: 12 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 55 (1 study) | See comment | Trial authors reported recurrence of ulcer in 27% (4/15) of participants receiving growth factor (recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor) versus 33% (3/9) in placebo group. Hazard ratio was calculated using data transformation. |

| Time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Meta‐analysis was not possible due to the unique comparisons within each trial, failure to report data, with or without a high rate of withdrawals. |

| Quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | None of the trials assessed this outcome. |

| Adverse events (non‐serious and serious) Follow‐up: 5 to 20 weeks | 412 per 10001 | 404 per 1000 (325 to 502) | RR 0.98 (0.79 to 1.22) | 385 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,6 | Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (1 trial), recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (1 trial), recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (1 trial), thrombin‐induced, platelet‐released platelet‐derived wound healing formula (1 trial). |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Assumed risk is based on the risks for the control group in the meta‐analysis. 2 Downgraded one level for limitations in design and execution: Eleven out thirteen trials assessing this outcome have high risk for selection bias. And outcome assessment was performed in unclear fashion. 3 Downgraded one level for inconsistency (I2: 51%). 4 Downgraded one level for limitations in design and execution. 5 Downgraded two levels for imprecision: small sample size and very low rate of events conducting to wide confidence intervals. 6 Downgraded one level for imprecision: Low rate of adverse events resulting in wide confidence intervals.

Background

See Appendix 1 for medical and epidemiological terms.

Description of the condition

It is estimated that in 2011, approximately 366 million people had diabetes, that is 7.0% of the world’s population (Bakker 2012a). Around 80% of these people live in low‐ or middle‐income countries. By 2030, the global estimate is expected to rise to 552 million – that is 8.3% of the adult population (Bakker 2012a). The development of foot ulcers is a major complication of diabetes mellitus (Boulton 2005; Lipsky 2004; Rathur 2007; Richard 2008; Sibbald 2008). The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot defines a foot ulcer as a full thickness wound involving the foot or ankle (Lavery 2008), that is, "a wound penetrating through the dermis" (Schaper 2004). A wound is a break in the epithelial integrity of the skin and may be accompanied by disruption of the structure and function of underlying normal tissue (Enoch 2008).

Epidemiology of the foot ulcer in people with diabetes

The proportion of diabetic foot ulcers among people with diabetes mellitus varies across studies, ranging from 5% to 43% (Appendix 2). There are four classification systems for diabetic foot ulcers that are summarised in Appendix 3 (Ince 2008; Lavery 1996; Schaper 2004; Wagner 1981). Outcomes for diabetic foot ulcers are predicted by ulcer area, presence of peripheral arterial disease, duration of diabetes, and presence of osteomyelitis (infection of bone) (Ince 2007; Lavery 2009; Oyibo 2001).

There is a close relationship between the presence of a diabetic foot ulcer and the amputation of a toe or a lower limb (Boulton 2008; Bakker 2012b; Younes 2004). Indeed, Boulton 2008 and Bakker 2012a reported that more than 85% of such amputations were preceded by an active foot ulcer. Amputation is a major complication for people with a diabetic foot ulcer (Bartus 2004; Schaper 2012a), and is a risk factor for increased mortality (Izumi 2009). The incidence of amputations is higher in people with diabetes (range 0.64 to 5.25 per 1000 person‐years) than in people without diabetes (0.03 to 0.24 per 1000 person‐years) (Schaper 2012a). The reported annual incidence of major amputation in industrialised countries ranges from 0.06 to 3.83 per 1000 diabetic people (Jeffcoate 2005). The incidence varies between countries, races, and communities (Jeffcoate 2005), however, there is concern about the methods used to calculate incidence and prevalence of amputation in people with diabetes (Van Houtum 2008). The incidence of reamputation in diabetic people with history of amputation within two years is almost 50% (Kanade 2007). Reamputation could be due to poor selection of the original amputation level through efforts to save as much of the lower extremity as possible (Skoutas 2009).

Diabetic foot ulcer pathways

The commonest causes of foot ulcers in people with diabetes are peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage), foot deformity, external trauma, peripheral vascular disease, and peripheral oedema (Boulton 2008; Figueroa‐Romero 2008; Quattrini 2008; Schaper 2012b; Szabo 2009). Other significant risk factors include being over 75 years of age, use of insulin, poor psychosocial status, hyperkeratosis (thickening of the outermost layer of skin), macrovascular and microvascular complications, and duration of diabetes (Chao 2009; Iversen 2008; Leymarie 2005).

Description of the intervention

Many studies have experimented with biological agents, aiming to modify the pathophysiology of diabetic foot ulcers. Growth factors are examples of these biological agents, and are considered to be a potentially important technological advance in the area of wound healing (Papanas 2007). Growth factors are platelet‐derived, endothelium‐derived, or macrophage‐derived, and include granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor, platelet‐derived growth factor, epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin‐like growth factor, and keratinocyte growth factor (Amery 2005; Barrientos 2008; Bennet 2003; Blair 2009; Cruciani 2009; Foster 2009; Galkoswka 2006; Grazul‐Bilska 2003; Rozman 2007; Smyth 2009). Growth factors are administered topically (on the surface) (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; Chen 2004; d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Landsman 2010; Lyons 2007; Niezgoda 2005; Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996; Tan 2008; Tsang 2003; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a), or intra lesionally (within the wound) (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009).

How the intervention might work

Normal wound healing has four phases: coagulation, inflammation, migration/proliferation, and remodelling (Papanas 2008). Sheehan 2006 observed that a 53% or greater reduction in the area of a foot ulcer area after four weeks of observation was a robust predictor of healing at 12 weeks. Since chronic wound healing may be limited by a lack of the necessary growth factors, healing may be speeded up by replacing or stimulating these growth factors, so enhancing the formation of granulation tissue, that precedes healing, within the wounds (Amery 2005; Barrientos 2008; Bennet 2003; Galkoswka 2006; Grazul‐Bilska 2003; Köveker 2000; Pradhan 2009; Viswanathan 2006). See Appendix 4 for wound‐healing and tissue‐forming ability of growth factors.

Why it is important to do this review

Diabetic foot ulcers represent a pervasive and important problem for people suffering from diabetes mellitus. Foot‐related problems are responsible for up to 50% of diabetes‐related hospital admissions (Albert 2002; Boulton 2001; Boulton 2005). Foot ulcers cause a low quality of life and often lead to lower extremity amputation (Armstrong 2008; Boutoille 2008; Goodridge 2006; Herber 2007; Kinmond 2003; Meatherall 2005; Price 2004; Ribu 2008; Schaper 2012a; Valensi 2007). Amputation causes prolonged hospitalisation, rehabilitation, and an increased need for home care and social services (Ali 2008; Ashry 1998; Girod 2003; Habib 2010; Lantis 2009; Redekop 2004; Siriwardana 2007; Van Acker 2000; Viswanathan 2005; Willrich 2005). Management of the diabetic foot has major economic consequences for patients, their families and society (Jeffcoate 2003; Jeffcoate 2004; Milman 2001; Rathur 2007; Smith 2004), and quality of life for caregivers is also unsatisfactory (Nabuurs‐Frassen 2005).

Several randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have assessed the benefits and harms of growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers, and they need a critical appraisal for risk of systematic errors that can cause bias (that is, could cause overestimation of benefits and underestimation of harms) and risk of random errors (that is, play of chance). Several narrative reviews and meta‐analyses have assessed the use of growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers, but these have been prone to errors (that is, lack of rigorous assessment of bias risks; no or insufficient evaluation of the risks of random errors; no evaluation of statistical heterogeneity; poor reporting of search methods; and potential conflicts of interest as authors of the reviews were also trialists of the included trials) (Hinchliffe 2008; Papanas 2008).

A systematic review of the most up to date evidence, including a rigorous assessment of the quality of that evidence, may help clinicians and clinical researchers make informed decisions about the use of growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of growth factors for diabetic foot ulcers in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in any setting.

Types of participants

Adults (>18 years of age) with a diabetic foot ulcer of any aetiology.

Types of interventions

See Appendix 1.

Experimental interventions

Platelet‐derived wound healing formula

Autologous growth factor

Allogeneic platelet‐derived growth factor

Transforming growth factor β2

Arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid (RGD) peptide matrix

Recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin)

Recombinant human epidermal growth factor

Recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor

Recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (telbermin)

Recombinant human lactoferrin

Recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor

In addition to receiving the experimental intervention (growth factors) participants also received standard care (see below).

Trials of granulocyte‐colony stimulating factors were excluded as they are the focus of another Cochrane review (Cruciani 2009).

Control interventions

Standard care (for example, antibiotic therapy, debridement, wound dressings) alone or plus placebo.

We noted whether the standard care was delivered similarly to intervention groups and noted any differences between intervention groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Complete wound healing (defined as 100% epithelialisation or skin closure without drainage).

Lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe).

Time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer.

Secondary outcomes

Ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (free from any recurrence).

Quality of life (as measured by a validated scale).

Adverse events: number and type of adverse events defined as any untoward medical occurrence ‐ not necessarily having a causal relationship with the treatment. We reported separately on adverse events that led, and did not lead, to treatment discontinuation. We defined serious adverse events according to the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Guidelines as any event that at any dose results in death, is life‐threatening, requires in‐patient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability, or is a congenital anomaly/birth defect, and any important medical event that may have jeopardised the patient or requires intervention to prevent it (ICH‐GCP 1997). All other adverse events were considered non‐serious.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched to identify reports of relevant randomised clinical trials:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 03 March 2015);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 2);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to March 2, 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations) (March 2, 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to March 2, 2015);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to March 3, 2015).

We used the following search strategy in The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

MeSH descriptor Foot Ulcer explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Diabetic Foot explode all trees

diabet* NEAR/3 ulcer*:ti,ab,kw

diabet* NEAR/3 (foot or feet):ti,ab,kw

diabet* NEAR/3 wound*:ti,ab,kw

(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5)

MeSH descriptor Intercellular Signaling Peptides and Proteins explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Insulin‐Like Growth Factor Binding Proteins explode all trees

growth NEXT factor*:ti,ab,kw

EGF or FGF or PDGF:ti,ab,kw

plermin or regranex or becaplermin:ti,ab,kw

(#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11)

(#6 AND #12)

This strategy was adapted to search Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL (please see Appendix 5). The MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefevbre 2011). The EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2010). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Searching other resources

The following web sites were also searched:

Food and Drug Administration (http://www.fda.gov/);

European Medicines Agency (http://www.emea.europa.eu);

International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (http://iwgdf.org/);

MedWatch The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm);

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm);

Scirus (www.scirus.com);

CenterWatch (http://www.centerwatch.com);

Evidence in Health and Social Care (http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/);

Dailymed (http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about.cfm).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

We also checked the reference lists of all the potentially relevant trials identified by the above methods.

Data collection and analysis

We summarised data using standard Cochrane Collaboration methodologies (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AJM‐C, SN) independently assessed each reference identified by the search against the inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements that arose through discussion. Those references that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were retrieved in full for further independent assessment by two review authors.

Data extraction and management

One review author independently extracted data (SN) from the included trials using a spreadsheet data extraction form and two review authors (AJM‐C, DSR) checked the data entered. We extracted the following data: eligibility criteria, demographics (age, sex, country), characteristic of the ulcers (anatomic site, size, number of ulcers, presence of infection, duration of ulceration), type of diabetes mellitus, duration of diabetes mellitus, ulcer treatments, and outcomes assessed. We discussed any discrepancies between review authors in order to achieve a final consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Independently, three review authors (AJM‐C, SN, DSR) assessed the risk of bias of each included trial using the domain‐based evaluation as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011). See, Appendix 6 for details.

Three review authors (LR, PO, JCT) checked these assessments. The review authors discussed discrepancies and achieved consensus.

Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether the RCTs were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed the risk of bias as being high if any of the above domains was assessed as being at unclear or high risk of bias.

Trials that had adequate generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, handling of incomplete outcome data, and no selective outcome reporting, and that were without other risks of bias were considered to be trials with a low risk of bias. We explored the impact of the risk of bias through undertaking subgroup analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes, such as incidence of complete wound healing, amputation, and adverse events, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each. For ulcer‐free days following treatment, a time‐to‐event outcome, we calculated the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI (Zavala 2007).

Dealing with missing data

We assessed the percentage of dropouts for each included trial, and for each intervention group, and evaluated whether an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis had been performed or could have been performed from the available published information. We contacted authors to resolve some queries on this issue.

In order to undertake an ITT analysis, we sought data from the trial authors on the number of participants in treatment groups, irrespective of compliance and whether or not participants were later thought to be ineligible, or otherwise excluded from treatment or lost to follow‐up. If this information was not forthcoming, we undertook a complete patient analysis, knowing that it might be biased.

We included patients with incomplete or missing data in sensitivity analyses by imputing them according to the following scenarios (Hollis 1999).

Extreme case analysis favouring the experimental intervention ('best‐worse' case scenario): none of the drop‐outs/participants lost from the experimental arm, but all of the drop‐outs/participants lost from the control arm experienced the outcome, including all randomised participants in the denominator.

Extreme case analysis favouring the control ('worst‐best' case scenario): all drop‐outs/participants lost from the experimental arm, but none from the control arm experienced the outcome, including all randomised participants in the denominator.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across trials that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). We considered statistical heterogeneity to be present if I2 was greater than 50% (Higgins 2011). When significant heterogeneity was detected (i.e. when I2 exceeded 50%), we attempted to identify the possible causes of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias and other bias by a funnel‐plot (Sterne 2011). We calculated Egger's test with Comprehensive Meta‐analysis software (CMA 2011).

Data synthesis

We calculated pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had anticipated clinical heterogeneity in the effect of the intervention and we planned to conduct the following sub‐group analyses had the data had been available. Furthermore, subgroup analysis would be performed only for complete wound healing (primary outcome).

We could not perform preplanned analyses for clinical subgroups (insulin‐using compared to non insulin‐using participants, severity and depth of wound, and use or not of antibiotics (Appendix 7; Appendix 8)) due to a lack of available data. We conducted the following preplanned subgroup analyses.

Duration of follow‐up: trials with less 20 weeks of follow‐up compared to trials with 20 weeks or more of follow‐up.

Type of growth factor.

The subgroup analyses were only performed for the outcome of complete wound closure.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the following sensitivity analysis in order to explore the influence of these factors on the intervention effect size.

Repeating the analysis taking attrition bias into consideration: 'Best‐worst case' scenario versus 'Worst‐best case' scenario

'Summary of findings' tables

We used the principles of the GRADE system to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with specific outcomes where possible (complete wound closure, lower limb amputation, ulcer‐free day following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers, time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer, quality of life, and adverse events) (Guyatt 2011f). We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADE software. The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence on the basis of the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodologic quality), the directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias (Balshem 2011; Guyatt 2011a; Guyatt 2011b; Guyatt 2011c; Guyatt 2011d; Guyatt 2011e; Guyatt 2011f; Guyatt 2011g; Guyatt 2011h; Guyatt 2011i; Guyatt 2012).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 424 references using our search strategies. Twenty‐eight trials (35 references) involving 2365 participants met our inclusion criteria (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; Chen 2004; d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Landsman 2010; Lyons 2007; Niezgoda 2005; Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996; Tan 2008; Tsang 2003; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). See Figure 1 for details of the flow of studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Tables of Characteristics of included studies show a detailed description of the studies.

Growth factors and populations assessed in the trials

The 28 RCTs reported 11 different growth factors compared with several different control interventions.

The experimental interventions included both non‐recombinant and recombinant growth factors. The non‐recombinant growth factors investigated were: platelet‐derived wound healing formula (Holloway 1993; Steed 1992); autologous growth factors (Driver 2006; Kakagia 2007; Saldalamacchia 2004); allogeneic platelet‐derived growth factor (Steed 1996); transforming growth factor β2 (Robson 2002); arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid (RGD) peptide matrix (Steed 1995b). The recombinant growth factors were recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Landsman 2010; Niezgoda 2005; Steed 1995a; Wieman 1998a); recombinant human epidermal growth factors (Afshari 2005; Chen 2004; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Tsang 2003; Viswanathan 2006); recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factors (Richard 1995; Tan 2008; Uchi 2009); recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (Hanft 2008); recombinant human lactoferrin (Lyons 2007); and recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor (Tan 2008).

Twenty trials compared growth factors against no growth factor or against placebo (without or with co‐interventions). The comparisons were: no growth factor (d'Hemecourt 1998; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Jaiswal 2010; Saldalamacchia 2004); saline solution (Bhansali 2009; Driver 2006; Holloway 1993; Richard 1995; Steed 1992; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996); or placebo (Agrawal 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Lyons 2007; Robson 2002; Steed 1995a; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). The characteristics of the placebo were not sufficiently described in Agrawal 2009, Hardikar 2005, Steed 1995a, Uchi 2009, or Wieman 1998a. Accordingly, only four trials used an appropriate placebo (Hanft 2008; Lyons 2007; Robson 2002; Viswanathan 2006).

Two trials compared one growth factor versus another growth factor, or different doses of the same growth factor (with or without co‐interventions). Tan 2008 compared recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor versus recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor. Fernández‐Montequin 2007 compared two doses of recombinant human epidermal growth factor, 75 µg and 25 µg.

Six trials compared growth factors versus other interventions (with or without co‐interventions): silver sulphadiazine (Afshari 2005); insulin (Chen 2004); oxidized regenerated cellulose/collagen biomaterial (Kakagia 2007); moisture‐regulating dressing (Landsman 2010); oasis wound matrix (Niezgoda 2005); and actovegin (Tsang 2003).

The co‐interventions used most frequently in both the experimental and the control groups were: wound debridement (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Lyons 2007;Robson 2002; Steed 1992;Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Tsang 2003; Uchi 2009; Wieman 1998a); wound dressing (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005, Kakagia 2007; Landsman 2010; Lyons 2007;Robson 2002;Steed 1992;Steed 1995a; Tan 2008); antibiotics ‐ topical (Chen 2004), and systemic (Afshari 2005; d'Hemecourt 1998; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Hardikar 2005; Lyons 2007;Viswanathan 2006); glycaemic control (Agrawal 2009; Chen 2004; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Hardikar 2005;Richard 1995;Viswanathan 2006); and offloading of local pressure on the foot ulcer (Bhansali 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Landsman 2010; Lyons 2007; Niezgoda 2005; Richard 1995;Robson 2002;Steed 1992;Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996). Two trials did not report the use of any co‐intervention (Holloway 1993; Saldalamacchia 2004).

Twenty‐six trials administered the intervention topically; two trials involving recombinant human epidermal growth factor used intralesional administration (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009).

The intervention was administered: once daily in 12 trials (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Landsman 2010; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1996; Tan 2008; Uchi 2009); daily during the six weeks for which participants were inpatients, then twice a week for 12 weeks in one trial (Richard 1995); twice daily in three trials (Lyons 2007; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a); once a week in one trial (Niezgoda 2005); twice a week in two trials (Robson 2002; Steed 1995b); or three times a week on alternate days in three trials (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008). Six trials did not report on the frequency of administration (Chen 2004; Driver 2006; Holloway 1993; Kakagia 2007; Saldalamacchia 2004; Tsang 2003).

The mean age of participants was 59.1 years (standard deviation (SD) ± 4.16), and most were male (66.6% (SD ± 16.1%)). Ten trials included participants with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Landsman 2010; Niezgoda 2005; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). Eighteen trials did not report the type of diabetes mellitus explicitly (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; Chen 2004; d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005; Kakagia 2007; Lyons 2007; Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996; Tan 2008; Tsang 2003; Uchi 2009). Trials included participants with target foot ulcers at nine different sites (fore‐foot, mid‐foot, hind‐foot, internal and external edge, sole, plantar surface, ankle). Six trials included participants with neuropathic ulcers (Hardikar 2005; Lyons 2007; Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Steed 1992; Steed 1996). The remaining 22 trials did not report the cause of the foot ulcers. Generally, the trials were conducted in the out‐patient (ambulatory) setting.

Location of trials

The trials were conducted in ten countries: three in China (Chen 2004; Tan 2008; Tsang 2003); two in Cuba (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009); one in Greece (Kakagia 2007); five in India (Agrawal 2009; Bhansali 2009; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Viswanathan 2006); one in Iran (Afshari 2005); one in Italy (Saldalamacchia 2004); one in Japan (Uchi 2009); and eleven in the USA (d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Hanft 2008; Holloway 1993; Landsman 2010; Robson 2002; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996; Wieman 1998a). One trial was conducted in both Canada and the USA (Niezgoda 2005), and another in both France and Italy (Richard 1995).

Trial methods

All trials were conducted using the parallel group trial design. Eighty‐two per cent of the trials (23/28) were conducted without reporting an a priori estimation of sample size. Trials were small with sample sizes ranging from 13 to 382 participants, with a median sample size of 60 and a mean of 87 (± SD 76). Fourteen trials had follow‐up periods of less than 20 weeks (range five to 18 weeks) (Afshari 2005; Agrawal 2009; Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Richard 1995; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1995b; Tan 2008; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006). Thirteen trials had a follow‐up of 20 weeks or more (range 20 weeks to 26 weeks) (Bhansali 2009; d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Landsman 2010; Lyons 2007; Niezgoda 2005; Robson 2002; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1996; Tsang 2003; Wieman 1998a). One trial did not report length of follow‐up (Chen 2004). In the trials, the units of randomisation and analysis were the participants. In terms of assessing the stage of the ulcer ‐ trials variously used Wagner's classification, the University of Texas Diabetic classification, or the International Association Enterostomal Therapy classification for (Appendix 3). Appendix 9 shows the methods for assessing ulcer dimension.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies for the following reasons: case reports (Acosta 2006; Miller 1999; Tuyet 2009); non‐RCTs (Aminian 2000; Saad Setta 2011); case series (Embil 2000; Hong 2006); and phase IV study (post‐marketing surveillance study) (Mohan 2007; Yera‐Alos 2013). See the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Ongoing trials

We identified six ongoing trials (NCT00521937; NCT00709514; NCT00915486; NCT00926068; NCT01060670; NCT01098357). Full details are shown in the table of Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Studies awaiting classification

Four citations are 'Awaiting classification' (Gomez‐Villa 2014; Morimoto 2013; Singla 2014; Young 1992; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for details).

Risk of bias in included studies

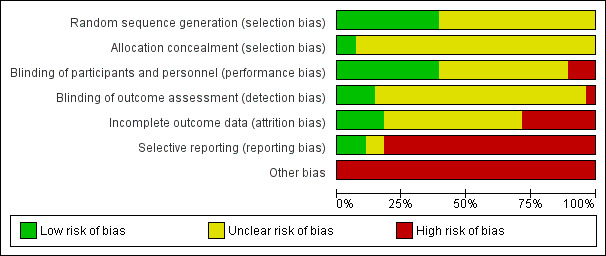

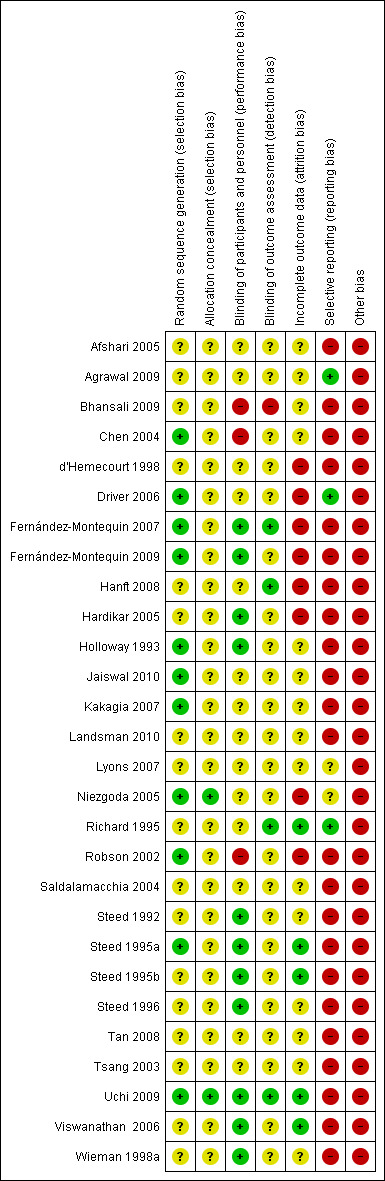

The risk of bias in the included trials is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The risk of bias arising from the method of generation of the allocation sequence was considered to be low in eleven trials (Chen 2004; Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Holloway 1993; Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Niezgoda 2005; Robson 2002; Steed 1995a; Uchi 2009). The remaining 17 trials had unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Allocation concealment

The risk of bias arising from the method of allocation concealment was considered to be low in two trials (Niezgoda 2005; Uchi 2009). The remaining 26 trials had an unclear risk for this domain.

Blinding

The risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants and personnel was rated as low in 11 trials (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Steed 1996; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). The risk of bias of performance bias was high in the remaining 17 trials.

In four trials outcome assessment was clearly reported as blinded, and detection bias was considered to be low (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Hanft 2008; Richard 1995; Uchi 2009). Blinding of outcome assessors was unclear or not performed in the remaining 24 trials, so the risk of detection bias was considered to be high.

Incomplete outcome data

Risk of attrition bias was rated as low in six trials (Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006), but high in the remaining 22 trials.

Selective reporting

Risk of selective outcome reporting bias was rated as low in three trials (Agrawal 2009; Driver 2006; Richard 1995), two trials was rated as having unclear risk (Lyons 2007; Niezgoda 2005), and rated as high in the remaining 23 trials. It was mainly due to these trials neither measured nor reported complete wound closure or safety data.

Other potential sources of bias

Risk of other bias was rated as high in all 28 trials due to bias in the presentation of data or design bias. Accordingly, all trials were considered to have an overall high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Complete wound closure (defined as 100% epithelialisation or skin closure without drainage)

Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor

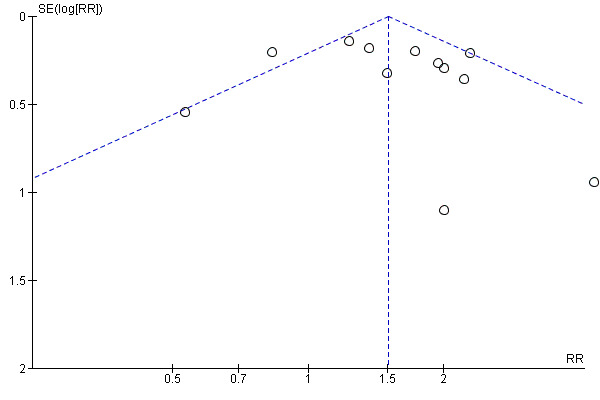

Meta‐analysis of 12 trials showed that growth factors, when considered as a group, increased the incidence of complete wound healing compared with placebo or no growth factor (345/657 (52.51%) versus 167/482 (34.64%); RR fixed‐effect model 1.51 95% CI 1.31 to 1.73; I2 = 51%, low quality evidence due to limitation in design, execution or both, and inconsistency) (d'Hemecourt 1998; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Jaiswal 2010; Richard 1995; Robson 2002; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). See Analysis 1.1. Figure 4 shows a funnel‐plot of this meta‐analysis.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor, Outcome 1 Complete wound closure.

4.

Funnel plot for comparison effect of any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor on 100% complete wound closure.

P‐value (two tailed) for Egger's test = 0.43

Subgroup analysis of trials with follow‐up of less than 20 weeks compared to trials with follow‐up of 20 weeks or longer

Meta‐analysis of five trials with follow‐up of less than 20 weeks shows uncertainty due to imprecision (small sample size and low rate of event) in the proportion of complete wound healing comparing any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor (102/167 (61.07%) versus 60/119 (50.42%); RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.55; I2 = 57%; P value 0.05) (Jaiswal 2010; Richard 1995; Saldalamacchia 2004; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006). Meta‐analysis of seven trials with a follow‐up of 20 weeks or longer showed an increase in the incidence of complete wound healing comparing any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor (243/490 (49.59%) versus 107/363 (29.47%); RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.98; I2 = 34%) (d'Hemecourt 1998; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Steed 1992; Steed 1995a; Wieman 1998a). The subgroup test showed high inconsistency between the two groups (I2 = 73.5%, P value 0.05). See Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor (subgroup analysis of trials with follow‐up < 20 weeks versus follow‐up ≥ 20 weeks), Outcome 1 Participants with complete wound closure.

Subgroup analysis by type of growth factor

One trial comparing autologous growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor showed inconclusive results regarding complete wound closure due to high imprecision (2/7 (28.57%) versus 1/7 (14.28%); RR 2.0, 95% CI 0.23 to 17.34; P value 0.53) (Saldalamacchia 2004). Meta‐analysis of two trials comparing platelet‐derived wound healing formula versus placebo showed a significant increase in the likelihood of participants with complete wound healing receiving growth factor (36/56 (64.28%) versus 7/27 (25.92%); RR 2.45, 95% CI 1.27 to 4.74, I2 = 0%) (Holloway 1993; Steed 1992). Meta‐analysis of five trials showed that recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) increased the proportion of the participants with complete wound healing compared with placebo (205/428 (47.89%) versus 109/335 (32.53%); RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.76, I2 = 74%) (d'Hemecourt 1998; Hardikar 2005; Jaiswal 2010; Steed 1995a; Wieman 1998a). Meta‐analysis of two trials comparing recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor showed inconclusive results regarding proportion of participants with complete wound healing (60/106 (56.60%) versus 27/59 (45.76%); RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.72, I2 = 62% P value 0.22) (Richard 1995; Uchi 2009). One trial comparing recombinant human epidermal growth factor versus placebo showed an increase in the incidence of complete wound healing using growth factor (25/29 (86.28%) versus 14/28 (50%); RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.57) (Viswanathan 2006). One trial comparing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor versus placebo showed no clear evidence of a difference regarding complete wound closure (15/29 (51.72%) versus 9/26 (34.61%); RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.82; P value 0.21) (Hanft 2008). The subgroup test showed no significant difference between the two groups (I2 = 0%, P value 0.55). However, the quality of the evidence showed in this subgroup analysis should be considered either low or very low. It is due to severe imprecision (wide confidence intervals) based on small sample size and low number of event (complete wound closure), inconsistency and limitations of design and execution of these trials. See Analysis 3.1.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor (subgroup analysis by type of growth factor), Outcome 1 Complete wound closure.

Sensitivity analysis taking attrition into consideration

Eight of the 12 trials combined for this outcome reported the exact number of participants with missing data in the intervention and the control groups. These trials involved 1043 participants (d'Hemecourt 1998; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Steed 1995a; Uchi 2009; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a).

'Best‐worst case' scenario

In a best‐worst case scenario analysis where none of the drop‐outs/participants were lost from the experimental arm, but all of the drop‐outs/participants lost from the control arm experienced the outcome, including all randomised participants in the denominator, meta‐analysis of eight trials showed a higher likelihood of complete wound healing in the participants receiving any growth factor compared with those exposed to placebo or no growth factor (417/607 (68.69%) versus 142/436 (32.56%); RR 2.09, 95% CI 1.81 to 2.41; I2 = 57%; P value 0.00001).

'Worst‐best case' scenario

In a worst‐best case scenario analysis (all drop‐outs/participants lost from the experimental arm, but none from the control arm experienced the outcome, including all randomised participants in the denominator) we did not find clear evidence of a difference in the proportion of participants assigned to any growth factor with complete wound healing compared with placebo or no growth factor (318/607 (52.38%) versus 218/436 (50%); RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.19; I2 = 60%; P value 0.43).

A test for subgroup differences showed a significant difference (I² = 98.2%; P value 0.0001). See Analysis 4.1.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor (sensitivity analyses considering attrition), Outcome 1 Complete wound closure.

Individual growth factor versus active control

There is inconclusive evidence of a difference between autologous growth factor and oxidized regenerate cellulose/collagen biomaterial regarding complete wound healing (4/34 (11.76%) versus 2/17 (11.76%); RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.20 to 14.93; P value 1.00) (Kakagia 2007). One trial reported inconclusive effects when recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) was compared with OASIS Wound Matrix for achieving complete wound healing (10/36 (27.77%) versus 18/37 (48.64%); RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.06; P value 0.08) (Niezgoda 2005). There is not conclusive results when recombinant human epidermal growth factor was compared with silver sulphadiazine for reaching complete wound healing (7/30 (23.33%) versus 2/20 (10%); RR 2.33, 95% CI 0.54 to 10.11; P value 0.26) (Afshari 2005). There was a higher proportion of complete wound healing in participants allocated to recombinant human epidermal growth factor than those receiving actovegin (32/42 (76.19%) versus 8/19 (42.10%); RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.15; P value 0.04) (Tsang 2003).

Lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe)

No trials described the extent of the amputation (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Holloway 1993; Tsang 2003).

Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor

Meta‐analysis of two trials showed no clear difference in number of lower limb amputations for growth factors, considered as a group, compared with placebo or no growth factor (19/150 (12.66%) versus 12/69 (17.39%); RR fixed‐effects model 0.74, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.39; I2 = 0%; P value 0.34, low quality evidence due to limitation in design, execution or both, and imprecision) (Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Holloway 1993). See Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor, Outcome 2 Lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe).

Individual growth factor versus active control

One trial comparing recombinant human epidermal growth factor versus actovegin showed no clear evidence of a difference regarding the incidence of lower limb amputation (2/42 (4.76%) versus 2/19 (10.52%); RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.07 to 2.98; P value 0.41) (Tsang 2003). Meta‐analysis of two trials comparing two doses of recombinant human epidermal growth factor, 75 μg and 25 μg, showed no clear difference regarding lower limb amputation (15/76 (19.73%) versus 16/66 (24.24%); RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.52; I2 = 0%; P value 0.52) (Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009).

Time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer

Fifteen trials assessed time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer. However, no trial reported hazard ratios or information that would allow us to calculate it. Most trials did not state explicitly that all participants achieved complete healing (Bhansali 2009; Chen 2004; d'Hemecourt 1998; Driver 2006; Fernández‐Montequin 2007; Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Niezgoda 2005; Robson 2002; Steed 1995a; Steed 1995b; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a), see Appendix 10 for details.

Secondary outcomes

Ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (free from any recurrence)

One trial comparing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (29 participants) versus placebo (26 participants) showed inconclusive difference in terms of ulcers‐free days following treatment (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.94 P value 0.56) (Hanft 2008).

Quality of life

None of the included trials addressed quality of life.

Adverse events

Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor

Meta‐analysis of four trials reporting number of participants with events showed no clear evidence of a difference between all growth factors when considered as a group compared with placebo or no growth factor in terms of adverse events (non‐serious and serious) (109/232 (46.98%) versus 63/153 (41.17%); RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.22; I2 = 0%; P value 0.85, low quality evidence) (Fernández‐Montequin 2009; Hanft 2008; Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993). See Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor, Outcome 4 Adverse events (non‐serious and serious).

Individual growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor

One trial comparing arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid peptide matrix with placebo reported adverse events as follows: "0.65 events per patient (N = 26) in arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid peptide matrix compared with 1.16 (N = 29) in the placebo group" (Steed 1995b). One trial showed no clear difference in overall adverse events when recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) was compared with placebo (31/61 (50.81%) versus 34/57 (59.64%); RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.18; P value 0.34) (Steed 1995a).

One trial comparing recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor versus placebo reported an incidence of serious adverse events similar across comparison groups (25%, 30% and 24% either recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor 30 μg/g or 100 μg/g, and placebo, respectively (Wieman 1998a).

Meta‐analysis of two trials comparing recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) with placebo showed no clear difference between treatment groups in terms of: infection (35/95 (36.84%) versus 28/127 (22.04%); RR 1.57, 95% CI 0.37 to 6.71, I2 = 88%; P value 0.54); cellulitis (11/165 (6.66%) versus 17/127 (13.38%); RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, I2 = 0%; P value 0.06); peripheral oedema (9/165 (5.45%) versus 16/127 (12.59%); RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.96, I2 = 0%; P value 0.04); pain (17/165 (10.30%) versus 16/125 (12.8%); RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.49, I2 = 0%; P value 0.45); or skin ulceration (14/165 (8.48%) versus 10/127 (7.87%); RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.37, I2 = 0%; P value 0.85) (d'Hemecourt 1998; Steed 1995a). See Analysis 6.2 to Analysis 6.6.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (rHuPDGF) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse event: infection.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (rHuPDGF) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Adverse event: skin ulceration.

Meta‐analysis of two trials comparing recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor with placebo did not find a difference in terms of infection (3/106 (2.83%) versus 3/59 (5.08%); RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.18 to 3.29; I2 = 0%; P value 0.72) (Richard 1995; Uchi 2009). Analysis 7.2.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (rHubFBGF) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse event: infection.

One trial showed no clear evidence of a difference between recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor versus placebo in terms of adverse events (4/97 (4.12%) versus 3/51 (5.88%); RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.02 to 2.83; P value 0.27) (Uchi 2009). One trial showed no clear difference between recombinant human epidermal growth factor group and placebo in terms of any adverse event (65/101 (64.35%) versus 31/48 (64.58%); RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.29; P value 0.98), or any severe adverse event (8/101 (7.92%) versus 2/48 (4.16%); RR 1.90, 95% CI 0.42 to 8.61; P value 0.40) (Fernández‐Montequin 2009). One trial comparing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor with placebo showed inconclusive results in the incidence of adverse events during the six‐week treatment period (14/29 (48.27%) versus 13/26 (50%); RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.65; P value 0.90) or the 12‐week observation period (5/26 (19.23%) versus (6/23 (26.08%); RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.10; P value 0.57). This trial also did not show a conclusive difference in terms of serious adverse events during the six‐week treatment period (2/29 (6.89%) versus 3/26 (11.53%); RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.30; P value 0.56) or 12‐week observation period (3/26 (11.53%) versus 3/26 (11.53%); RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.22 to 4.50; P value 1.00) (Hanft 2008).

Individual growth factor versus active control

One trial comparing recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) with OASIS Wound Matrix did not find clear evidence of a difference in terms of treatment related events (10/36 (27.77%) versus 17/37 (45.94%); RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.14; P value 0.12) (Niezgoda 2005). One trial comparing different doses of recombinant human epidermal growth factor, 75 μg versus 25 μg, showed no difference in terms of burning sensation (5/23 (21.73%) versus 2/18 (11.11%); RR 1.96, 95% CI 0.43 to 8.94 P value 0.39; 41 participants), or local pain (4/23 (17.39%) versus 3/18 (16.66%); RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.27 to 4.08; P value 0.95; 41 participants) (Fernández‐Montequin 2007). One trial showed evidence of a difference in reduction of local wound pain in participants who received recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor compared with those who received recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (2/104 (1.92%) versus 6/35 (17.14%); RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.53; 9 P value 0.006) (Tan 2008).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This Cochrane systematic review of growth factors for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes included 28 randomised clinical trials that incorporated 2365 participants. Trials evaluated 11 different experimental growth factors compared with several different control interventions. Overall, the trials had a high risk of bias and were underpowered. Most of the trials, 82% (23/28), did not report an a priori sample size estimation. Drug companies sponsored at least 14 of the trials. The trials were conducted in 10 countries (Canada, China, Cuba, France, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, and the USA). In general the trials were conducted in the out‐patient (ambulatory) setting. The reporting of trial participants characteristics was ill‐defined with regard to their type of diabetes mellitus and etiology of their diabetic foot ulcer.

Meta‐analysis was possible only on six types of experimental growth factors: platelet‐derived growth factor, autologous growth factor; platelet‐derived wound healing formula, recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor, recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor, and human epidermal growth factor.

We were able to meta‐analyse data on trial participants with complete wound healing. Meta‐analysis of 12 trials showed that all growth factors, when considered as a group, seemed to increase the proportion of participants with complete wound healing significantly compared with placebo or no growth factor. The quality of the estimate was qualified as low due to limitations in design and execution of included trials, and inconsistency (Table 1).

We were able to meta‐analyse data on lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe). One meta‐analysis of two trials showed no clear evidence that growth factors, when as considered as a group, reduced the risk of lower limb amputation compared with placebo or no growth factor. Evidence was downgraded to very low due to pitfalls in design and execution of included trials, and a very small sample size and very low number of events (Table 1). Another meta‐analysis of two trials that compared two doses of recombinant human epidermal growth factor, 75 μg and 25 μg, did not show a significant difference between the two doses.

Eleven trials reported time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer, however, meta‐analysis was not possible due to the unique comparisons within each trial, failure to report data, with or without a high rate of withdrawals. One trial comparing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor versus placebo showed inconclusive result on ulcer‐free days following treatment. Trials did not report data on quality of life. Growth factors compared against placebo or no growth factor showed no difference in terms of any adverse event. However, overall, safety data were poorly reported and adverse events may have been underestimated. Evidence was considered as low due to limitations in design and execution, and low number of event (Table 1).

Trials with a 20‐week or longer follow‐up seemed to be more effective in increasing the number of participants with complete wound closure than trials with a follow‐up of less than 20 weeks. However, there was no an conclusive difference between these groups.

We conducted a subgroup analysis of trials by type of growth factor. There was an inconclusive difference between growth factor versus placebo or no growth factor in terms of the number of participants with complete wound closure. This is could be due to small sample size and low number of events.

In terms of complete wound closure we found a clear difference between the 'best‐worse case' scenario and the 'worst‐best case' scenario in sensitivity analyses that took attrition into consideration. It should be interpreted as inconsistency due to missing data.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This Cochrane review found evidence suggesting that growth factors might be useful for increasing complete wound closure of foot ulcers in people with diabetes , though this conclusion is based on randomised clinical trials with a high risk of bias due to pitfalls in design and execution of the included trials. Therefore, and based on GRADE findings, future research are a need to know with a better certainty the clinical benefits of growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers. Furthermore, the safety profile of all the growth factors is unclear.

The results in this review are based on data from trials that included a broad range of participants with different co‐morbidities, who received different treatment approaches. That heterogeneity downgraded the quality of evidence. We cannot rule out that the calculations of the potential effects have been overestimated due to poor methodological quality (bias risks, design, analysis and the small information size. Therefore, these three variables, i.e., high heterogeneity, pitfalls in methodology, and small sample size and low number of events, even after meta‐analysis, depleted the quality of evidence. Futhermore, we cannot exclude an underestimation of harms. A caveat concerning the safety of recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) has been outlined recently; this relates to the risk of cancer in people who use three tubes or more compared to that in non‐users (FDA 2008; Papanas 2010). However, an observational study reported that this growth factor does not appear to increase the risk of cancer or cancer mortality (Ziyadeh 2011), though further high‐quality data are clearly needed.

Quality of the evidence

GRADE assessments were conducted on outcomes of both meta‐analysis and non‐pooled trials. None of the trials was graded as providing strong evidence, primarily because of small sample sizes (even after meta‐analysis) which generate wide confidence intervals with low precision of estimate of the intervention effects, and the high risk of bias due to a lack of adequate randomisation methods, lack of blinding, high attrition, and unclear reporting of outcomes.

Quality of evidence also had to be downgraded due to inconsistency. We can't reject a potential detection bias ‐wound healing is a fairly subjective outcome‐ where is there is no blinded outcome assessment or unclear for this, even though due to clear definition of complete wound closure.

See Table 1 for complete assessment and rationale for ratings.

This review assessed the impact of missing data on the effect of intervention in increasing the proportion of participants with complete wound closure (Analysis 4.1) using best/worst and /best case scenarios. If the amount of missing data is large, the conclusion on the difference between the comparison groups is not valid (Hollis 1999). This Cochrane review found a significant subgroup difference comparing all trials, best/worst and /best case scenarios (Analysis 4.1).

This Cochrane review has identified the following issues that should be considered when planning future trials: inconsistent information concerning the healing percentage of wound closure definition provided by trial reports, differences in definitions of outcomes, and inconsistency of reported outcomes need to be avoided. Trials should adopt an agreed set of core outcomes for each medical condition (Clarke 2007). This approach may reduce the impact of outcome reporting bias (Kirkham 2010).

The impact of outcome reporting bias may be reduced by adopting the recommendations of The Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (PCORI 2012). This organisation was established by United States Congress as an independent, non‐profit organisation, created to conduct research to provide information about the best available evidence to help patients and their healthcare providers make more informed decisions. PCORI’s research is intended to give patients a better understanding of the prevention, treatment and care options available, and the science that supports those options (Gabriel 2012; Basch 2012; PCORI 2012; Selby 2012).

Potential biases in the review process

There is a group of biases called significance‐chasing biases (Ioannidis 2010), which includes publication bias, selective outcome reporting bias, selective analysis reporting bias, and fabrication bias. Publication bias represents a major threat to the validity of systematic reviews, particularly in reviews that include small trials. However, this Cochrane review has a low risk of publication bias due to the meticulous trial search that was performed, and the fact that we emailed the main authors of a number of the trials identified. Selective outcome reporting bias operates through suppression of information about specific outcomes and has similarities to publication bias of whole studies or trials, in that ‘negative’ results remain unpublished (Ioannidis 2010). We were surprised to find how few times amputations or mortality were reported in the trials. This Cochrane review found that 75% of the included randomised clinical trials had high risks of selective outcome reporting. For example, adverse events were not reported (Afshari 2005; Bhansali 2009; Chen 2004, Jaiswal 2010; Kakagia 2007; Landsman 2010; Saldalamacchia 2004; Steed 1992; Steed 1996; Tan 2008; Tsang 2003), or were poorly reported in a total of 16 trials (Hardikar 2005; Holloway 1993; Lyons 2007; Viswanathan 2006; Wieman 1998a). These 16 trials incorporated 55% of the randomised participants (1289/2365) included in this review. This review found no evidence of asymmetry of the funnel plot for complete wound closure (Figure 4).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of our review are similar to the findings from other systematic reviews (Buchberger 2010; O'Meara 2000) and a narrative review of complete closure of diabetic foot ulcer using growth factors (Wieman 1998b).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence from RCTs to recommend or refute the use of growth factors in treating diabetic foot ulcers. The results are based on the results of 28 RCTs with a high risk of bias. There is a paucity of information for other main clinical outcomes such as lower limb amputation, time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer and ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (free from any recurrence). There is an absence of information on mortality, and quality of life. In addition, adverse events data remain unclear. Therefore, prescription of growth factors for treating people with diabetic foot ulcers can not be supported or rejected until new evidence from a large, high‐quality trial becomes available and alters this conclusion.

Implications for research.

This systematic review has identified the need for well‐designed, adequately powered RCTs to assess the benefits and harms of growth factors with complete wound closure, lower limb amputation, and adverse events as the primary outcomes. Since epidemiological studies have connected to the recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (becaplermin) to a five‐fold increase in cancer mortality in people who used more than three tubes of it compared to non‐users, potential risk needs to be ruled out in large randomised clinical trials before wider use can be recommended. The trials should be designed according to the SPIRIT statement (Chan 2013), and reported according to the CONSORT statement for improving the quality of reporting of efficacy; the trials should also provide better reports of harms/adverse events encountered during their conduct (Ioannidis 2004; Moher 2010; Schulz 2010). Future trials should be planned following the Foundation of Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research recommendations (Basch 2012; Gabriel 2012; McKinney 2012). Potential trials should also include clinical outcomes such as, incidence of lower limb amputation (minimum of one toe, with the extent of amputation being specified, and data the incidence of different extents of amputation also reported separately), time to complete healing of the diabetic foot ulcer, quality of life, ulcer‐free days following treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (free from any recurrence), and adverse events.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to Sally EM Bell‐Syer and Nicky Cullum for the suggestions to enhance the quality of this review. In addition we acknowledge the comments made by the peer referees; Julie Bruce, Jane Burch, Gill Worthy, Anita Raspovic, Mark Rodgers and Stephanie Wu. The protocol and review were copy‐edited by Elizabeth Royle. Our thanks go to Li Xun for translating Chen 2004 from the original Chinese.

We want to express our thanks to María Ximena Rojas who was a review author on the protocol.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of medical and epidemiological terms

| Terms | Definition | Reference |

| Ankle Brachial Index | Comparison of the blood pressure between the brachial artery and the posterior tibial artery. It is a predictor of peripheral arterial disease. | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |

| Actovegin | A biological drug ‐ a calf blood haemodialysate ‐ manufactured from a natural source | Buchmayer 2011 |

| Amputation | The removal of a limb or other appendage or outgrowth of the body | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |

| Arginine‐glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) peptide matrix (Argidene Gel®, formerly Telio‐Derm Gel®, Telios Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA, USA) |

This peptide matrix contains the arginine‐glycine‐aspartic acid amino acid sequence, through which cells in vivo become attached to macromolecules of extracellular matrix via surface integrin receptors. The matrix (intervention) is a sterile non‐preserved clear viscous gel, formulated in phosphate‐buffered saline and dispensed from a single‐use syringe. The functional ingredient of RGD peptide matrix is a complex formed by the combination of a synthetic 18‐amino acid peptide and sodium hyaluronate. It also contains added unconjugated sodium hyaluronate as a viscosity‐increasing agent, and, therefore, does not need to be prepared from patient's samples | O'Meara 2000 |

| Attrition bias | A type of selection bias due to systematic differences between the study groups in the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the process of loss of their members during study conduct, i.e., due to attrition among subjects in the study. | Porta 2008 |

| Autologous platelet gel | See 'platelet‐rich plasma' | Lacci 2010 |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Farmitalia Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) |

A heparin‐building, single‐chain peptide of 146 amino acids, ubiquitously distributed in mesoderm‐ and neuroectoderm‐derived tissues. This is a potent mitogen for all cell types involved in the healing process. It is highly angiogenic and chemotactic for fibroblasts and endothelial cells. bFGF is produced by recombinant DNA technology using Escherichia coli type b | O'Meara 2000 |

| Bias in the presentation of data | Error due to irregularities produced by digit preference, incomplete data, poor techniques of measurement, technically poor laboratory procedures, or an intentional attempt to mislead | Porta 2008 |

| Burning sensation | An abnormal feeling of burning in the absence of heat | http://www.healthline.com/hlc/burning‐sensation |

| Callus |

A hard, thickened area of skin occurring in parts of the body that are subjected to pressure or friction, particularly the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands | O'Meara 2000 |

| Cellulitis | An acute, diffuse, and suppurative inflammation of loose connective tissue, particularly the deep subcutaneous tissues, and sometimes muscle, most commonly seen as a result of infection of a wound, ulcer, or other skin lesion | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |

| Co‐intervention | In a randomised controlled trial, the application of additional diagnostic or therapeutic procedures to members of either, some or all of the experimental and control groups | Porta 2008 |

| Connective tissue disease | A heterogeneous group of disorders, some hereditary, others acquired, characterised by abnormal structure or function of one or more of the elements of connective tissue, i.e. collagen, elastin, or the mucopolysaccharides | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |

| CT‐102 activated platelet supernatant (APST) (Curative Technologies, Setauket, NY, USA) (synonym: platelet‐derived wound‐healing formula (PDWHF)) |

A combination of growth factors released from ρ‐granules of human platelets by thrombin | O'Meara 2000 |

| Debridement |

The removal of foreign material and dead or contaminated tissue from, or adjacent to, a wound until the surrounding healthy tissue is exposed | O'Meara 2000 |

| Design bias | The difference between a true value and that obtained through the faulty design of a study. Examples include uncontrolled studies where the effects of two or more processes cannot be separated because of lack of measurement of key causes of the exposure or outcome (confounding); also studies performed on poorly‐defined populations or with unsuitable control groups | Porta 2008 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, type 1 | A subtype of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by insulin deficiency. It is manifested by the sudden onset of severe hyperglycemia, rapid progression to diabetic ketoacidosis, and death unless treated with insulin. The disease may occur at any age, but is most common in childhood or adolescence. | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |

| Diabetes Mellitus, type 2 | A subclass of diabetes mellitus that is not insulin‐responsive or dependent (NIDDM). It is characterized initially by insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia; and eventually by glucose intolerance; hyperglycemia; and overt diabetes. Type II diabetes mellitus is no longer considered a disease exclusively found in adults. Patients seldom develop ketosis but often exhibit obesity. | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh |