Abstract

A case of bilateral pulmonary aspergilloma caused by an atypical isolate of Aspergillus terreus is described. The diagnosis was established by the presence of septate, dichotomously branched fungal elements in freshly collected bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum specimens and by repeated isolation of the fungus in culture. Specific precipitating antibodies against the A. terreus isolate were demonstrated in the patient's serum. The isolate was atypical as it failed to produce fruiting structures on routine mycological media, but it did so on extended incubation on potato flake agar and produced globose, relatively heavy-walled, hyaline accessory conidia (formerly termed aleurioconidia) on both vegetative and aerial mycelia. Also, it produced an intense yellow diffusing pigment in the medium. The report underscores the increasing importance of A. terreus in the etiology of pulmonary aspergillosis. It is suggested that A. terreus antigen be included in the battery of serodiagnostic reagents to facilitate the early diagnosis of infections caused by this species.

CASE REPORT

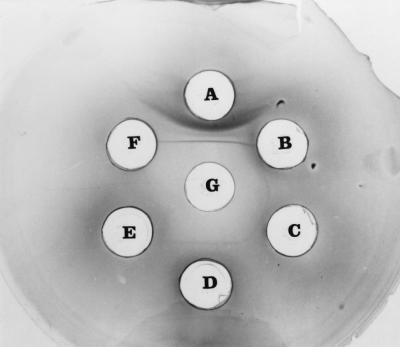

A 26-year-old Syrian male who was known to have type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus was admitted to Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital in Kuwait in November 1996. He complained of general fatigue, tiredness, a productive cough, especially at night, and numbness in his fingertips and toes. He had lost 20 kg of weight during the previous year. The patient gave a history of pulmonary tuberculosis in his country of origin 4 years earlier, for which he received treatment for 6 months. On physical examination, the patient was conscious and fully alert. His temperature was 36.9°C, his pulse was 80 beats/min, and his blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg. He had no lymphadenopathy. There was clubbing of his fingers and toes. Examination of the chest revealed the presence of a pleural rub and anterior and posterior bilateral basal crepitations. Examination of the heart and abdomen revealed no abnormality. Central nervous system examination showed evidence of polyneuropathy of the gloves-and-stocking pattern. Nerve conduction studies of both the hands and feet showed the presence of moderately severe axonal peripheral neuropathy secondary to diabetes. Laboratory investigations showed markedly raised blood sugar levels (21 mmol/liter) with normal renal function. His white blood cell count was 10.8 × 10/liter with 61% neutrophils. Examination of the urine showed high levels of glucose (56 mmol/liter), but no protein or red blood cells were observed. A chest X ray and a computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of a “fungal ball” in the right and left apical regions (Fig. 1 and 2). It also showed in the upper zones the presence of fibronodular infiltrations, which were probably due to the old tubercular infection. Pulmonary function tests showed an obstructive pattern which improved with bronchodilators and a decreased total lung capacity which suggested a restrictive pattern. Microscopic examination of bronchoalveolar lavage specimens showed many pus cells, a number of fungal elements, gram-positive cocci, and gram-negative bacilli. A potassium hydroxide-calcofluor mount confirmed the presence of septate, dichotomously branched hyphae (Fig. 3). Culture yielded Haemophilus influenzae, beta-hemolytic streptococci, and Streptococcus pneumoniae and many colonies of a mold. Repeat culture of sputum specimens yielded the same fungus. Since the conidial heads were not observed on the initial examination of the fungal isolate, it was provisionally identified as a Scedosporium species due to the presence of thick-walled, single-celled conidia that arose directly from the hyphae or that developed at the tip of the conidiogenous cells and that were mistaken for annelloconidia. The isolate was later confirmed to be an atypical strain of Aspergillus terreus. The patient's serum was tested for precipitins against Aspergillus (poly) antigen (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) and against culture filtrate antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus prepared in our laboratory (11), but it was found to be negative. However, when culture filtrate and mycelial antigens prepared from the patient's isolate were used, 3 and 1 precipitin lines, respectively, were obtained in an immunodiffusion test (Fig. 4). The culture filtrate antigen was prepared by growing the isolate in glucose asparagine broth as a stationary culture at 28°C for 3 weeks (11). The filtrate was dialyzed and concentrated 15 times by evaporation. The mycelial antigen was prepared by grinding 10 g of the separated mycelial mat in 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (0.05 M; pH 7.4) with glass beads in a pestle and mortar. The slurry so obtained was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a Nalgene filter unit (pore size, 0.45 μm), dialyzed, and concentrated about 10 times for use as an antigen. Since the patient had a chest infection, he was treated with ampicillin at 1 g every 6 h and cefotaxime at 1 g every 8 h. His diabetes was controlled with higher doses of insulin until a satisfactory level of blood sugar was achieved. He was discharged after 1 week of antibacterial therapy. No surgical intervention or specific antifungal therapy was planned since he had no hemoptysis or other aspergilloma-associated symptoms. The patient has since been lost for follow-up.

FIG. 1.

Posterioanterior chest radiograph showing cavitary lesions in both the lung fields with aspergilloma in the right upper zone (arrow).

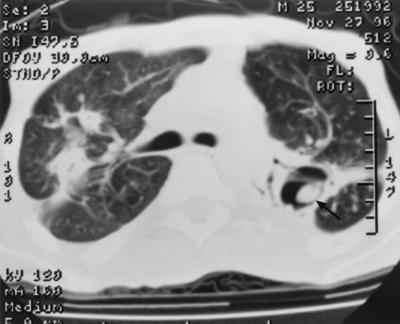

FIG. 2.

Aspergilloma shown by CT scan in a cavity of the left lung (arrow).

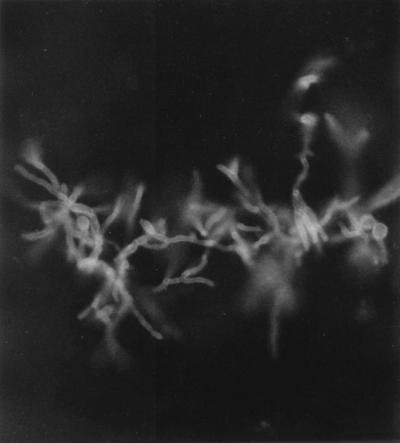

FIG. 3.

Potassium hydroxide-calcofluor mount showing septate, dichotomously branched hyphae of A. terreus in bronchoalveolar lavage sediment. Magnification, ×400.

FIG. 4.

Ouchterlony's double diffusion test. The central well (G) contained the patient's serum, and peripheral wells contained culture filtrate (A) and mycelial antigens (B, C, and D) prepared from the A. terreus isolate. Peripheral wells contained culture filtrate antigens of A. fumigatus and A. flavus (E and F, respectively). Note the precipitin bands against A. terreus antigens.

Aspergillus species are widely distributed in the environment, and infection is acquired primarily through the respiratory tract (19). Although over 200 different species of Aspergillus are known, only a few are recognized human pathogens (3). A. fumigatus and A. flavus are the most frequent etiologic agents of pulmonary and systemic aspergillosis, whereas infection with A. terreus is rarely reported (3). So far, A. terreus has been incriminated as a causative agent in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (12, 13), invasive aspergillosis (4, 9, 10, 30), cardiac infections (6, 22, 23), osteomyelitis (25), and septic arthritis (27). Cases of pulmonary aspergilloma due to A. terreus have rarely been reported (12). Here, we describe a case of bilateral pulmonary aspergilloma in a 26-year-old diabetic patient caused by an atypical strain of A. terreus.

Description of isolate.

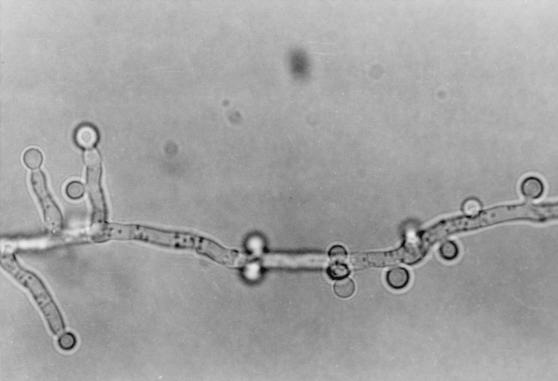

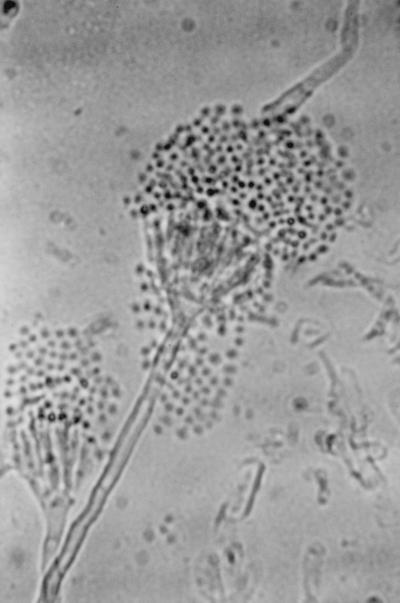

The isolate was moderately fast growing on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco Laboratory, Detroit, Mich.), attaining a diameter of 60 mm in 10 days at 28°C with entire margins. The color was variable in shades of yellow but became salmon to cinnamon colored on aging and produced diffusible pigment. The isolate was able to grow on Mycobiotic agar (containing chloramphenicol and cycloheximide; Difco Laboratories) at 37°C reaching a diameter of 50 mm in 7 days (Fig. 5). Microscopically, hyphae were septate and hyaline, producing smooth, thick-walled, spherical to pear-shaped accessory conidia (formerly referred to as aleurioconidia), which mostly occurred singly and which measured 3 to 5 μm in diameter (Fig. 6). The isolate failed to produce fruiting structures on Sabouraud dextrose agar, Czapek agar, and malt yeast extract agar. The isolate was forwarded to the Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSC) at San Antonio, for further characterization and was accessioned into the stock collection as strain UTHSC 98-403. There the isolate was subcultured onto potato flake agar (PFA) prepared in-house and was incubated at 25°C (20). The isolate grew rapidly, producing deep orange colonies that had a lemon yellow diffusing pigment and that were similar to those produced on Sabouraud dextrose agar. A slide culture prepared on PFA produced the thick-walled globose cells but failed to produce diagnostic fruiting structures. After 10 weeks of incubation, stereoscopic examination of the colonies revealed small, strongly columnar fruiting structures consistent with an Aspergillus species. The microscopic morphology of these structures, when examined by tape mounts, revealed globose vesicles up to 15 μm in diameter, a biseriate arrangement with crowded metulae and phialides, and small, globose conidia (1.5 to 2.0 μm in diameter), all features characteristic for A. terreus (Fig. 7). This atypical strain of A. terreus has been deposited with the American Type Culture Collection under accession no. 201901. The isolate appeared to be resistant to amphotericin B, ketoconazole, and fluconazole and to be susceptible to itraconazole and flucytosine when tested on buffered RPMI 1640 medium with Etest strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden), on the basis of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards interpretive criteria for yeast fungi (17).

FIG. 5.

Colony morphology of A. terreus isolate on Mycobiotic agar after 7 days of incubation at 37°C.

FIG. 6.

Slide culture of A. terreus isolate on Sabouraud dextrose agar showing globose, thick-walled accessory conidia (aleurioconidia), Magnification, ×1,000.

FIG. 7.

Conidial head of the atypical isolate of A. terreus produced on PFA after 10 weeks of incubation at 25°C.

Discussion.

A. terreus is widespread in the environment and particularly in warm arable soils. Although ubiquitous and sometimes disregarded as a mere colonizer, a review of recent English-language medical literature (Medline search) suggests that invasive infections due to A. terreus are being reported with increasing frequency (10; D. M. Flynn, B. G. Williams, S. V. Hetherington, B. F. Williams, M. A. Giannini, and T. A. Pearson, Letter, Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 14:363–365, 1993). Furthermore, infection with this species may be associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to those associated with infection with other species of the genus, despite amphotericin B therapy (10, 14). Colonization of preexisting lung cavities with A. terreus has rarely been reported (12), and the case that we describe appears to be only the second one reported in the English-language medical literature. This case also underscores the variability that may be seen in isolates of A. terreus. The designations for several species have been reduced to synonyms under the species as the organisms seem to represent only cultural variants. The case isolate, on the basis of its colonial morphology, appears to be similar to A. terreus var. boedijni, described by Thom and Raper (29) (and since reduced), due to its bright orange-brown colonies. It also resembles two currently accepted varieties, A. terreus var. africanus and A. terreus var. aureus, in that it displays small, sclerotial-like masses, as in A. terreus var. africanus, and areas of golden yellow hyphae and a much greater abundance of accessory conidia both in the vegetative mycelium and in the aerial mycelium, as in A. terreus var. aureus (18). Sterile variants of Aspergillus have occasionally been isolated from patients with chronic cases of aspergillosis; these variants sometimes appear highly atypical and are difficult to identify (15; L. Sigler, M. A. Viviani, U. Margini, R. Epis, V. Fregoni, A. Grancini, and A. Pastorini, Abstr. 13th Int. Soc. Hum. Anim. Mycol., p. 396, 1997). A sterile white mold which is able to grow at 45°C, especially if it is isolated from a respiratory specimen, may be suspected to be A. fumigatus because of its thermotolerant nature. However, to our knowledge sterile variants of A. terreus have not been reported previously. Application of the exoantigen test may be helpful in the identification of such atypical isolates (24).

Aspergilloma, a noninvasive form of aspergillosis, may develop in a healthy host, in which the organism colonizes a cavity that has been created by some form of destructive process that has previously involved the lung, such as pulmonary tuberculosis, as apparently is the case with our patient (1). In most of the cases, aspergilloma occurs singly on either side of the lung field, but bilateral involvement may be seen in about 5 to 10% of the cases (5). Aspergilloma may even develop in areas of bronchiectasis caused by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (26). Some recent reports, however, suggest that the noninvasive form of aspergillosis may not always be noninvasive (16). Instead of developing in a preexisting cavity, it may create its own cavity and then grow as a relatively noninvasive organism. This form of infection has been termed semiinvasive aspergillosis by Gefter et al. (8) and chronic necrotizing aspergillosis by Binder et al. (2) and is not distinguishable from noninvasive aspergillosis (16). Semiinvasive aspergillosis tends to occur in patients whose immune systems are mildly depressed, for example, because of chronic obstructive lung disease or diabetes. Although our patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and had also had an obstructive lung function, it is impossible for us to document the radiological progression of the disease or clearly ascertain whether it was a classical form of aspergilloma or the consequence of this newly characterized form of semiinvasive aspergillosis. The semiinvasive form is known to start initially as an infiltrate in one of the apices which, over a period of weeks to months, slowly develops cavitation with formation of a “crescent sign.” Chang and King (4) described a case of invasive aspergillosis caused by A. terreus with an air-crescent sign in a leukemic patient.

The classical radiological picture of aspergilloma is one of a mobile, intracavitary mass usually in upper lobes, and the mass is almost pathognomonic of the disease (1). However, aspergilloma may sometimes be difficult to see even if it is present, and CT may be necessary to show its presence (21, 31). In our patient, while the fungal ball was visible in the right upper lobe by chest X ray, it could also be seen on the left side by CT scan (Fig. 2). The diagnosis of aspergilloma was confirmed by the presence in serum of precipitins against the patient's isolate. Although the presence of multiple precipitin bands is characteristic of aspergilloma due to a continuous antigenic stimulus in a generally nonimmunocompromised host (1, 7), we found precipitins only against culture filtrate antigen. Occasionally, other intracavitary masses, such as cancer or Wegener's granulomatosis, may simulate aspergilloma. However, a negative precipitin test for Aspergillus antigen can exclude such a possibility. In our patient, initial testing for precipitins with A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and Aspergillus (poly) antigens was negative until the serum was tested against the patient's isolate. This suggests that A. terreus has little or no cross-reactivity with A. fumigatus or A. flavus and that a diagnosis may be missed if homologous reagents are not used (12). The chances of isolating Aspergillus species from sputum specimens in patients with aspergilloma are about 50% (1), since it is dependent upon the intrapulmonary location of the lesion and its communication to the bronchial tree. Demonstration of precipitins therefore has greater sensitivity and specificity than culture for the diagnosis of aspergilloma (7, 19).

Aspergilloma of the respiratory tract is often a clinically occult process until the patient complains of hemoptysis. It may occasionally be found during routine monitoring of patients with cavitary tuberculosis, as was the case with our patient. Specific therapy is not required for patients with asymptomatic aspergilloma (16). However, it may be pertinent to mention here that our A. terreus isolate was resistant to amphotericin B. This is consistent with reports of the increased resistance of clinical isolates of A. terreus to amphotericin B (14, 28; C. Lass-Florl, D. Niederwieser, G. Kofler, and M. Dierich, Abstr. Focus on Fungal Infections 6, abstr. 36, 1996). Therefore, for patients for whom treatment for A. terreus infection is warranted, use of itraconazole or voriconazole could be a better therapeutic option than use of amphotericin B (14, 28). The case described here is the fourth case of aspergillosis due to A. terreus diagnosed by us in Kuwait during the last 3 years; the other cases were of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (two cases) and endocarditis. The report underscores the increasing importance of A. terreus in the etiology of pulmonary aspergillosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Kuwait University research grant MI 076.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albelda S M, Talbot G H. Pulmonary aspergillosis. In: Fishman A P, editor. Pulmonary disease and disorders. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Book Co.; 1988. pp. 1639–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder R E, Faling L J, Pugatch R D, Mahasaen C, Snider G L. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis. A discrete clinical entity. Medicine. 1982;61:109–118. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodey G P, Vartivarian S. Aspergillosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:413–437. doi: 10.1007/BF01964057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S W, King T E. Aspergillus terreus causing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with air crescent sign. J Natl Med Assoc. 1986;78:248–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J C, Chang Y L, Luh S P, Lee J M, Lee Y C. Surgical treatment for pulmonary aspergilloma: 28-year experience. Thorax. 1997;52:810–813. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.9.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin S, Ho P L, Yuen S T, Yuen K Y. Fungal endocarditis in bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of literature. J Infect. 1998;37:287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)92169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans E G V, editor. Serology of fungal infections and farmer's lung disease. A laboratory manual. British Society for Mycopathology Working Party. Leeds, United Kingdom: British Society for Mycopathology; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gefter W B, Weingard T R, Epstein D M, Ochs R H, Miller W T. “Semi-invasive” pulmonary aspergillosis. Radiology. 1981;140:313–321. doi: 10.1148/radiology.140.2.7255704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara K S, Ryce J H. Disseminated Aspergillus terreus infection in immunocompromised hosts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:770–775. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61749-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwen P C, Rupp M E, Langnas L N, Reed E C, Hinrichs S H. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: 12-year experience and review of literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1092–1097. doi: 10.1086/520297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan Z U, Sandhu R S, Randhawa H S, Menon M P S, Dusaj I S. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a study of 46 cases with special reference to laboratory aspects. Scand J Respir Dis. 1976;57:73–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laham M N, Carpenter J L. Aspergillus terreus, a pathogen capable of causing infective endocarditis, pulmonary mycetoma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:769–772. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laham M N, Allen R C, Greene J C. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) caused by Aspergillus terreus-specific lymphocyte sensitization and antigen-directed serum opsonic activity. Ann Allergy. 1981;46:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lass-Florl C, Kofler G, Kropshofer G, Hermans J, Kreczy A, Dierich M P, Niederwieser D. In vitro testing of susceptibility to amphotericin B is a reliable predictor of clinical outcome in invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:497–502. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGinnis M R, Buck D L, Jr, Katz B. Paranasal aspergilloma caused by an albino variant of Aspergillus fumigatus. South Med J. 1997;70:886–888. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197707000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller W T. Aspergillosis: a disease with many faces. Sem Roentgenol. 1996;31:52–66. doi: 10.1016/s0037-198x(96)80040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M 27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raper K B, Fennell D I. The genus Aspergillus. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rinaldi M G. Aspergillosis. In: Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Ohashi M, Turan A, editors. Laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. Principles and practice. Vol. 1. 1988. pp. 559–572. Bacterial, mycotic and parasitic diseases. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinaldi M G. Use of potato flake agar in clinical mycology. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1159–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1159-1160.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts G M, Citron K M, Stricteland B. Intrathoracic aspergilloma. Role of CT in diagnosis and treatment. Radiology. 1987;165:123–128. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.1.3628758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russack V. Aspergillus terreus myocarditis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1990;3:275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schett G, Casati B, Willinger B, Weinlander G, Binder T, Grabenwoger F, Sperr W, Geissler K, Jager U. Endocarditis and aortal embolization caused by Aspergillus terreus in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission diagnosis by peripheral blood culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3347–3351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3347-3351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekhon A S, Standard P G, Kaufman L, Garg A K, Cifuentes P. Grouping of Aspergillus species with exoantigens. Diagn Immunol. 1986;4:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seligsohn R, Rippon J W, Lerner S A. Aspergillus terreus osteomyelitis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;137:918–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah A, Khan Z U, Chaturvedi S, Ramachandaran S, Randhawa H S, Jaggi O P. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with coexistent aspergilloma: a long-term follow-up. J Asthma. 1989;26:109–115. doi: 10.3109/02770908909073239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinfield S, Durez P, Hauzeur J P, Motte S, Appelboom T. Articular aspergillosis. Two case reports and review of the literature. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:1331–1334. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.12.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton D A, Sanche S E, Revankar S G, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2243–2245. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2343-2345.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thom C, Raper K B. Manual of aspergilli. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tritz D W, Woods G L. Fatal disseminated infection with Aspergillus terreus in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:118–122. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman R A, Miller W T. Pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970;109:505–515. doi: 10.2214/ajr.109.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]