Abstract

People with spinal cord injury (SCI) face unique challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, including greater risk of poor COVID-19-related outcomes, increased social isolation, and restricted access to important services. Furthermore, COVID-19 related restrictions have decreased already low levels of physical activity (PA) in this population. Therefore, the purpose of this commentary is to: 1) address the impact of COVID-19 on PA and sedentary behavior (SB) in people with SCI; 2) provide potential SB reduction strategies to guide future research; and 3) provide recommendations to increase PA and reduce SB on behalf of the American College of Sports Medicine Exercise is Medicine (ACSM-EIM) and Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL-PIVOT) using a social-ecological model targeting the individual-, social environment-, physical environment-, and policy-level determinants of behavior in people with SCI.

Keywords: Sedentary behavior reduction, COVID-19, Physical activity, Spinal cord injury, Socio-ecological model

Physical distancing recommendations to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 have become commonplace. These constraints, however, have negative impacts on health and well-being, especially among vulnerable populations, including people with spinal cord injury (SCI).1 Despite increased vaccine delivery, people with SCI continue to face unique challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, including greater risk of poor COVID-19-related outcomes (e.g., a higher mortality rate than the general population,2, 3, 4 increased social isolation, and restricted access to important services such as physical therapy5 , 6). Additionally, COVID-19 restrictions have further reduced already low levels physical activity (PA) in people with SCI.7

During COVID-19 and beyond, the SCI community needs guidance in establishing COVID-19-safe recommendations for engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors to promote PA and reduce sedentary behavior (SB).8 , 9 Importantly, SB and PA are distinct lifestyle behaviors, which are independently associated with cardiometabolic disease risk in the general able-bodied population.10 , 11 As such, SB (while awake, any behaviors performed in a seated or reclined position ≤ 1.5 Metabolic Equivalents12) may also be an independent cardiometabolic risk factor for people with SCI.8 Therefore, activity guidelines for people with SCI, their caregivers, and healthcare team may need to expand to include strategies helping to reduce SB.8 , 13 This commentary will 1) address the impact of COVID-19 on PA and SB in people with SCI, 2) provide potential strategies to reduce SB to guide future research, and 3) provides recommendations for to promote PA and reduce SB reduction based on a socio-ecological model.

Promoting healthy movement behavior in people with SCI during COVID-19

Prior to COVID-19, barriers to engaging in PA among people with SCI were complex and present at multiple levels, including individual, social environment, physical environmental, and policy levels. Example barriers include attitudes or past experience with PA, social isolation, and access to gyms with knowledgeable exercise professionals or appropriate equipment.14 , 15 Perhaps unsurprisingly, with the COVID-19 related social restrictions, there has been a decrease in self-reported recreation- and occupation-based PA among individuals with SCI when comparing pre-versus post-lockdown levels.7 Arguably, this low PA trend is more likely to be reversed if the multiple levels of barriers (i.e., individual, social/physical environment, policy) unique to people with SCI are considered.

In addition to addressing increased PA engagement, it is important to consider mitigation of SB for people with SCI. SB is an independent risk factor for poor health, including increased cardiometabolic diseases, as well as poor mental health.16 Of concern, emerging evidence indicates that cardiometabolic diseases, which are more frequent in persons with SCI17 are associated with more severe COVID-19 outcomes (e.g., increased incidence of hospitalization, ICU admission and death).18 Furthermore, Hall et al.,19 suggests that we are currently in the midst of two pandemics: COVID-19 and a SB pandemic. While COVID-19 may be a watershed moment that changes the structure and connected nature of society, this commentary seeks to identify specific strategies for PA promotion and SB mitigation for individuals with SCI during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Healthy movement behavior promotion in SCI during COVID-19: A socio-ecological framework

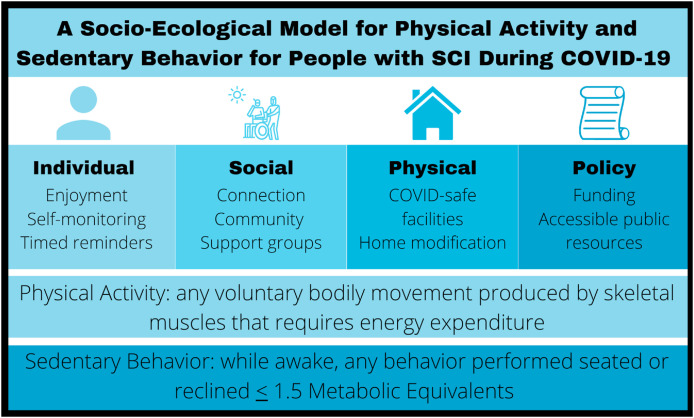

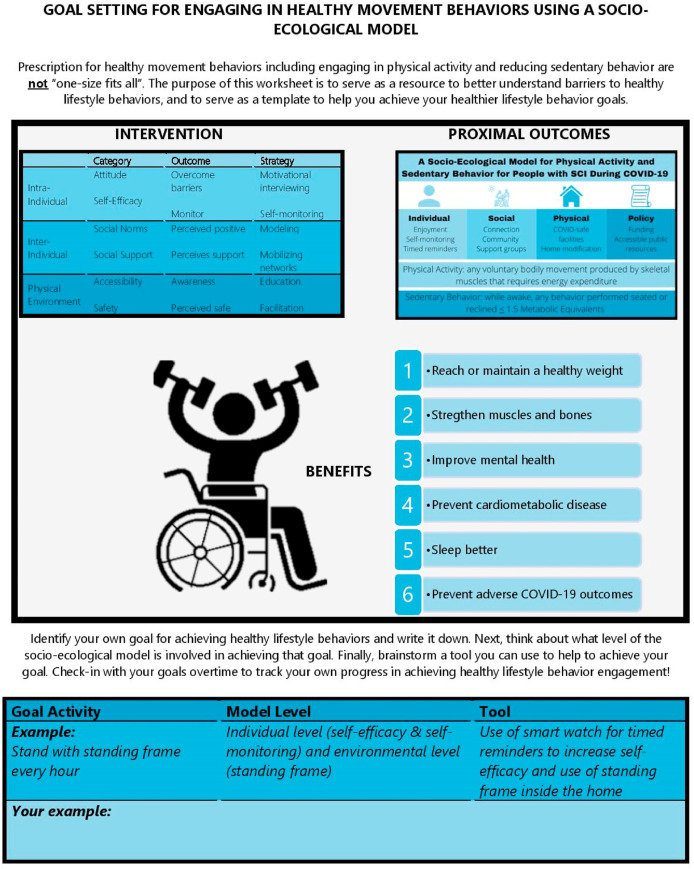

The socio-ecological model allows us to contextualize the multiple levels of influence on behavior, including individual (e.g., self-efficacy, enjoyment), social-environment (e.g., social support), physical-environment (e.g., home), and policy (e.g., legislation) levels.20 Contextualizing the key influences upon movement behaviors among persons with SCI allows us to provide practical recommendations to increase PA and decrease SB during and beyond COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ). To guide the recommendations which follow, it is important to clearly define PA and SB with respect to SCI. PA can be defined as activities one chooses to engage in during free time such, including ambulatory activities and resistance training.21 SB can be defined as any waking behavior in a seated or reclining posture (≤1.5 METS).12 However, due to the nature of SCIs, one may not be able to feasibly modify their position out of a seated or reclining posture. Therefore, “muscular inactivity” may be a more appropriate, but less commonly used term to describe SB in people with SCI.8 It is also important to note the controversy present in the field regarding SB reduction for people with SCI due to the postural challenges of the injury. However, PA and SB are independent factors targeted by separate recommendations for able-bodied populations. Additionally, both PA and SB are included in the most recent guidelines by the World Health Organization for people with disabilities.13 Therefore, the following recommendations attempt to integrate promotion of PA and reduction of SB in safe feasible recommendations during COVID-19 (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A socio-ecological model for physical activity and sedentary behavior for people with Sci during COVID-19 including definitions and recommendations.

Fig. 2.

A goal setting resource for people with SCI to achieve healthy lifestyle behavior engagement using the socio-ecological model.

Individual domain

Identifying ways to interrupt SB and achieve recommended PA guidelines14 that the individual enjoys while abiding by COVID-19 restrictions are critical. Potentially enjoyable activities include light PA (e.g., playing with a pet/gardening), using arm cycle ergometry,22 or modified yoga.23 With respect to SCI, an important consideration is the large differences in function and fitness between individuals with tetraplegia and paraplegia.24 , 25 Therefore, type of SCI needs to be considered to ensure the activity recommended is appropriate. Additionally, the use of goal setting, self-monitoring, and self-management techniques to improve self-efficacy (e.g., PA tracking via smartphone app or setting timed reminders to move) is a critical component of behavior change. To interrupt SB, timed reminders could be used to with light activities throughout the day via use of a standing frame or electrical stimulation. Some individuals with SCI may be able to apply for a grant26 for a standing frames or electrical stimulation equipment therefore alleviating a potential financial burden. Individuals with higher lesions (i.e., tetraplegia) could work with caregivers to schedule time to access or use other methods of movement such as functional electrical stimulation for engagement in PA/SB mitigation.

Social environment domain

To combat isolation, virtual platforms can be utilized to challenge family or friends to SB interruption challenges or to participate in PA classes.23 For example, individuals within SCI support groups could challenge one another to engage musculature for at least 1 min every hour or by reminding one another to break-up a sedentary bout with resistance band exercises. With respect to PA, loneliness is negatively associated with PA in people with SCI.27 Virtual platforms could target loneliness and promote PA via online peer mentorship28 or other online community-based support groups.29 Additionally, the care-giver/care-receiver relationship is critical for support30 and during COVID-19 care-givers may consider sheltering in place with the individual with SCI to combat loneliness therefore providing social support to engage in PA/mitigate SB. As other family members may be working virtually, it may be feasible to adjust living conditions to include others for greater safe, social engagement such as providing PA assistance or engaging in a SB reduction together (e.g., engaging musculature via arm ergometer or electrical stimulation or by using a standing frame). Furthermore, time spent at rehabilitation clinics are commonly one of the only opportunities people with SCI have to interact with others outside of the home. Opening rehabilitation facilities to encourage social interaction31 with COVID-19 safe precautions (cleaning, masks, social distancing) are important to help people with SCI engage in PA.

Physical environment domain

Barriers to engaging in activity include safety concerns and lack of access to facilities, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fortunately, the available evidence indicates that behavioral interventions have increased unsupervised PA at both home and gym settings in people with SCI,32 suggesting that physical environments may be potentially modifiable to promote healthy movement behavior. The physical environment can be modified to include: 1) installing grab-bars for standing and completing selfcare thereby breaking up SB; 2) identifying appropriate height surfaces of furniture/counters that provides support for completing simple tasks potentially reducing SB/increasing PA; 3) placing resistance bands/other equipment around the home to make it easier to replace SB with PA; and 4) utilizing online PA classes which removes the significant transportation barrier for this population. Depending on the level and severity of the lesion, not all individuals with SCI can participate in PA without access to proper care or adapted exercise equipment, therefore policy change is needed to make at-home accommodations to improve the accessibility PA promotion and SB mitigation more feasible.

Policy domain

As COVID-19 continues, it is important that policy makers consider the impact that lockdown has on individuals with SCI. We call upon policymakers to pass legislation specifically to aid individuals with SCI, and also primary care facilities so that there is greater access to the care that individuals with SCI need during the pandemic. Care and engagement with PA for individuals with SCI occurs at major healthcare centers like hospitals or local rehabilitation clinics. Public officials should consider greater aid for small businesses and rehabilitation clinics within larger healthcare settings that could support safe increasing PA engagement and remove barriers for people with SCI to ensure public buildings are achieving the recommendations set forth by WHO's Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021.33 Additionally, public officials can modify public resources such as parks to ensure they are inclusive and accessible for people with SCI. For example, public officials could make sure assistive technology, such as Access Earth, Accomable, and Google Maps all have accurate data on accessible buildings and locations.34

Exemplar daily recommendation

People with SCI spend much, or all day, sitting.13 Therefore, it is especially important for people with SCI to replace SB with PA. We urge healthcare providers, exercise professionals, and caregivers to encourage people with SCI to examine their daily schedule and prioritize time to replace SB with strategies that contribute towards recommended PA guidelines.14 Individuals are encouraged to disperse activities of daily living throughout the day to interrupt periods of prolonged SB. Engaging in multiple 10-min bouts of PA throughout the day may be more feasible than a single 30-min bout of PA and it is important to remember that some PA is better than doing none. The World Health Organization guidelines suggest that adults living with disabilities should engage in at least 150–300 minutes of moderate intensity PA or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity PA per week for substantial health benefits.13 Additionally, multicomponent PA with varied types of both aerobic and resistance training especially targeting functional capacity are recommended.13 At first, people with SCI should focus on increasing the duration of PA and then overtime seek to improve intensity and/or frequency. People with SCI can also increase self-efficacy by utilizing their social network, or activity tracker/smart phone to set daily goals and track progress over the course of the day.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has created broad challenges to sustaining population physical health. We urge providers, policy makers, caregivers, and people living with SCI alike to identify enjoyable forms of PA and SB interruptions strategies considering the individual, social and physical environments, and policy level determinants of behavior to encourage healthy behaviors during COVID-19 and beyond.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Sánchez-Raya J., Sampol J. Spinal cord injury and COVID-19: some thoughts after the first wave. Spinal Cord. 2020;58(8):841–843. doi: 10.1038/s41393-020-0524-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogenes B, Querée M, Townson A, Willms R, Eng JJ. COVID-19 and spinal cord injury: clinical presentation, clinical course, and clinical outcomes: a rapid systematic review. J Neurotrauma. Published online January 27, 2021. doi:10.1089/neu.2020.7461. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Stillman M.D., Capron M., Alexander M., Di Giusto M.L., Scivoletto G. COVID-19 and spinal cord injury and disease: results of an international survey. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020;6(1):21. doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0275-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Cola M., Jiménez-Velasco I., Gutiérrez-Henares F., et al. Clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a cohort of patients with disability due to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020;6(1):39. doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas F.P., Murphy C. COVID-19 and spinal cord injury professionals: maintaining a scholarly perspective. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;43(3):279. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1751529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Connell C.M., Eriks-Hoogland I., Middleton J.W. Now, more than ever, our community is needed: spinal cord injury care during a global pandemic. Spinal cord Ser cases. 2020;6(1):18. doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marco-Ahulló A., Montesinos-Magraner L., González L.-M., Morales J., Bernabéu-García J.A., García-Massó X. Impact of COVID-19 on the self-reported physical activity of people with complete thoracic spinal cord injury full-time manual wheelchair users. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1857490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verschuren O., Dekker B., van Koppenhagen C., Post M. Sedentary behavior in people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(1):173. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch A., Hinrichs T., Oberhauser C., Cieza A., Group S.S. Do people with spinal cord injury meet the WHO recommendations on physical activity? Int J Public Health. 2016;61(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0724-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews C.E., George S.M., Moore S.C., et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):437–445. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.019620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young D.R., Hivert M.F., Alhassan S., et al. Sedentary behavior and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(13):e262–e279. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs B.B., Hergenroeder A.L., Katzmarzyk P.T., Lee I.-M., Jakicic J.M. Definition, measurement, and health risks associated with sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(6):1295–1300. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carty C, Ploeg HP van der, Biddle SJH, et al. The first global physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines for people living with disability. J Phys Activ Health. 18(1):86-93. doi:10.1123/jpah.2020-0629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Martin Ginis K.A., van der Scheer J.W., Latimer-Cheung A.E., et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord. 2018;56(4):308–321. doi: 10.1038/s41393-017-0017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fekete C., Rauch A. Correlates and determinants of physical activity in persons with spinal cord injury: a review using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health as reference framework. Disabil Health J. 2012;5(3):140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piercy K.L., Troiano R.P., Ballard R.M., et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama. 2018;320(19):2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers J., Lee M., Kiratli J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(2) doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31802f0247. https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Fulltext/2007/02000/Cardiovascular_Disease_in_Spinal_Cord_Injury__An.9.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow N., Fleming-Dutra K., Gierke R., et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382–386. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6913E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ, Arena R. A tale of two pandemics: how will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. Published online April 2020:S0033-0620(20)30077-3. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latimer A.E., Ginis K.A., Craven B.C., Hicks A.L. The physical activity recall assessment for people with spinal cord injury: validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(2):208–216. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000183851.94261.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Scheer J.W., Martin Ginis K.A., Ditor D.S., et al. Effects of exercise on fitness and health of adults with spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2017;89(7) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004224. 736 LP - 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinai IS of M at M COVID-19 incluseive home workout guide. https://labs.icahn.mssm.edu/brycelab/adaptive-and-inclusive-home-workouts-guide/ Published 2020.

- 24.Manns P.J., Chad K.E. Determining the relation between quality of life, handicap, fitness, and physical activity for persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(12):1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrmann K.H., Kirchberger I., Biering-Sørensen F., Cieza A. Differences in functioning of individuals with tetraplegia and paraplegia according to the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) Spinal Cord. 2011;49(4):534–543. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Association U.S. United spinal association spinal cord resource center. https://askus-resource-center.unitedspinal.org/index.php?pg=kb.page&id=2971 Published 2021.

- 27.Santino N., Larocca V., Hitzig S.L., Guilcher S.J.T., Craven B.C., Bassett-Gunter R.L. Physical activity and life satisfaction among individuals with spinal cord injury: exploring loneliness as a possible mediator. J Spinal Cord Med. Published online May. 2020;7:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1754651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamontagne M.-E., Best K.L., Clarke T., Dumont F.S., Noreau L. Implementation evaluation of an online peer-mentor training program for individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2019;25(4):303–315. doi: 10.1310/sci19-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman S.D., Toatley S.L., Rodgers M.D. Translating a spinal cord injury self-management intervention for online and telehealth delivery: a community-engaged research approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42(5):595–605. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2018.1518123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodakowski J., Skidmore E.R., Rogers J.C., Schulz R. Role of social support in predicting caregiver burden. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(12):2229–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guilcher S.J.T., Catharine Craven B., Bassett-Gunter R.L., Cimino S.R., Hitzig S.L. An examination of objective social disconnectedness and perceived social isolation among persons with spinal cord injury/dysfunction: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(1):69–75. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1616328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J.K., West C.R., Martin Ginis K.A. The effects of a patient and provider Co-developed, behavioral physical activity intervention on physical activity, psychosocial predictors, and fitness in individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Sports Med. 2019;49(7):1117–1131. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Organization W.H. World Health Organization; 2015. WHO Global Disability Action Plan 2014-2021: Better Health for All People with Disability. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong A.W.K., Ng S., Dashner J., et al. Relationships between environmental factors and participation in adults with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional multi-center study. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(10):2633–2645. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]