Abstract

Background

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) delivered via a mobile phone messaging robot to patients who had their total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty procedures postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Ninety patients scheduled for total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty who experienced surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic were randomized to the ACT group, receiving 14 days of twice daily automated mobile phone messages, or the control group, who received no messages. Minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) in preintervention and postintervention patient-reported outcome measures were utilized to evaluate the intervention.

Results

Thirty-eight percent of ACT group participants improved and achieved MCID on the Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System Physical Health compared to 17.5% in the control group (P = .038; number needed to treat [NNT] 5). For the joint-specific Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement and Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement (KOOS JR), 24% of the ACT group achieved MCID compared to 2.5% in the control group (P = .004; NNT 5). An improvement in the KOOS JR was found in 29% of the ACT group compared to 4.2% in the control group (P = .028; NNT 5). Fourteen percent of the ACT group participants experienced a clinical important decline in the KOOS JR compared to 41.7% in the control group (P = .027; NNT 4).

Conclusion

A psychological intervention delivered via a text messaging robot improved physical function and prevented decline in patient-reported outcome measures in patients who experienced an unexpected surgical delay during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Level of Evidence

1.

Keywords: hip arthritis, THA, TKA, telemedicine, text messaging, COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated innovations in healthcare delivery with an emphasis on telehealth applications. Automated mobile phone messaging robots (“Chatbots”) are a form of telehealth that utilizes software to deliver programmed text-based conversations to patients outside of traditional healthcare settings. During the COVID-19 pandemic automated mobile phone messaging has been utilized by the World Health Organization and others to communicate details regarding the COVID-19 pandemic to patients around the world [[1], [2], [3]]. Previous works have also utilized automated mobile phone messaging robots to communicate with patients to obtain information regarding blood pressure [4], opioid utilization [[5], [6], [7]], physical activity in patients with diabetes [8], and to obtain patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Interventions have also been performed utilizing this modern communication technique including medication adherence [13,14], office appointment reminders [15,16], blood pressure management [17], and as an adjunct to traditional communication techniques after hip and knee arthroplasty [18,19] and spine surgery [20].

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant changes in musculoskeletal healthcare delivery with elective surgery delay or cancellation becoming commonplace. Total hip (THA) and knee arthroplasties (TKA) have been affected with an estimated 30,000 primary THA and TKA procedures delayed or canceled per week during the early portion of the COVID-19 pandemic [21]. Additionally, osteoarthritic hip and knee pain was found to increase in 54% of patients since the delay of their surgery due to COVID-19 [22]. Surgical delays and cancellations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have created a projected backlog of surgical cases that may last up to 2 years or longer necessitating further surgical delays [23]. Furthermore, as COVID-19 and its variants remain active throughout the United States, it is likely that healthcare systems will continue to have unexpected surgical cancellations either due to worsening outbreaks or hospital protocols requiring postponement of surgery for patients who test positive in the days prior to their procedure.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a psychological intervention that seeks to decrease avoidable suffering and helps individuals to live according to self-identified personal values [24,25]. ACT attempts to augment an individual’s psychological flexibility utilizing 6 core cognitive processes: Acceptance, Defusion, Contact with the Present Moment, Self-as-Context, Values, and Committed Action [24]. ACT has proven efficacious in the management of chronic pain when compared to standard pharmacological treatment alone [[26], [27], [28], [29]] and in decreasing opioid utilization in at-risk orthopedic surgery patients [30].

Given the limitation in providing traditional care to patients with debilitating hip and knee osteoarthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of ACT delivered via an automated mobile phone messaging robot to patients who had their scheduled primary THA or TKA procedures indefinitely postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our null hypothesis was there would be no clinical difference in PROMs during the 2-week intervention period between participants receiving the ACT messaging protocol and the control group.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled trial was pre-registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04329897) and reporting is consistent with CONSORT guidelines. Ethical approval of this study was provided by the Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled from April 6, 2020 until April 20, 2020 at a single academic medical center in the United States.

Adults (≥18 years of age) who had previously been scheduled for primary THA or TKA and had their surgery delayed indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic were deemed eligible for the study. Those eligible were called by the research team and underwent the informed consent process. If a potential participant did not have a personal mobile phone or could not receive text messaging, they were ineligible for participation in the study. At the time of consent participants were required to complete electronic forms comprised of a basic demographic questionnaire and baseline PROMs consisting of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System (PROMIS) Global Health 10 Short Form with Mental Health (PROMIS MH) and Physical Health (PROMIS PH) component summary scores, PROMIS Pain Intensity 1A Short Form, PROMIS Pain Intensity 3A Short Form, PROMIS Pain Interference 8A Short Form, PROMIS Emotional Distress - Anxiety 8A Short Form, and either the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement (HOOS JR) or Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement (KOOS JR) depending on whether the patient was scheduled for THA or TKA. Participants in both groups also completed a questionnaire that was previously utilized to assess patient thoughts and concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic [22].

Following completion of all PROMs, participants were randomized into the control or ACT groups using a standard online random number generator with a range set from 1 to 10 and a 1:1 ratio by a research assistant. Participants who received an odd number from the 1 to 10 range were placed in the ACT group and received the ACT messaging protocol, while participants given an even number were placed in the control group and did not receive any mobile phone messaging over the 2-week study period. During the 2-week study period, patients were not contacted by their surgeon to reschedule surgery. A 2-week study period was chosen in an effort to ensure patients would be able to complete the protocol prior to their surgery being rescheduled.

The ACT group patients received automated mobile phone text messages twice a day (morning and evening) communicating an ACT-based intervention for 14 days with day 1 starting the day after enrollment into the study. All participants received the same morning and evening messages during the 2-week study period. All messages can be found in full in Appendix. Control group participants did not receive the ACT intervention or any other form of communication from their surgical team over the 2-week study period. The ACT messages were developed by our study group (CAA, ER, NAB) in conjunction with a pain psychologist (VK) specializing in ACT for chronic pain. These messages utilized the core fundamentals of ACT [24] with the objective of helping recipients develop better coping skills for their osteoarthritic pain during the current COVID-19 pandemic. At the end of each delivered message, participants were prompted they could receive additional messages if they replied “More.” The opportunity for additional messages was provided so we might begin to understand the volume of communication participants would be interested in engaging with. A message bank of additional messages was then accessed by the software and another message was sent (Appendix). At the conclusion of the 14-day study period, participants in both groups were again contacted by telephone and asked to complete a repeat set of PROMs via an electronic email link. Participants in the ACT group were also asked if they would recommend ACT delivered by automated mobile phone messaging to a friend or family member if they were experiencing a delay in their surgical care.

Changes in PROMs from enrollment to postintervention were calculated by subtracting either postintervention scores from baseline scores or vice versa, as appropriate, depending on the direction higher scores signify for a specific PROM. Higher scores on postintervention follow-up indicate an improvement from baseline for PROMIS MH and PH as well as for HOOS JR and KOOS JR while lower scores on postintervention follow-up indicate an improvement from baseline PROs for PROMIS NRS (numeric rating scale) Pain, Pain Intensity, Pain Interference, and Anxiety. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is the amount of change in a PROM that would be expected for a patient to present different clinically. There are multiple techniques to calculate MCIDs for PROMs. Additionally, not all PROMs have well-established MCIDs. A commonly accepted means of determining MCID is by utilizing ½ standard deviation of the mean difference in preintervention and postintervention scores as previously described [31,32]. We analyzed our results against MCID values provided in prior reports in the literature, when available, and utilized the ½ standard deviation method when prior MCIDs were not available. We utilized the MCID values in Table 1 to assess both clinically relevant improvement and clinically relevant decline across all PROMs [31,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37]].

Table 1.

The Minimal Clinical Important Difference for Each Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Utilized.

| Patient-Reported Outcome Measure | Literature Values |

|---|---|

| PROMIS Mental Health | 2.9 [31] |

| PROMIS Physical Health | 1.9 [31] |

| PROMIS Pain NRS | 1 [33,34] |

| PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a | 3.7a |

| PROMIS Pain Interference | 2.35 [35] |

| PROMIS Anxiety | 2.3 [35] |

| HOOS JR | 6.4 [36] |

| KOOS JR | 7 [36,37] |

PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System; NRS, numeric rating scale; HOOS JR, Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement; KOOS JR, Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement.

Literature values for these PROMs have not been reported and thus ½ standard deviation method for calculating the minimally clinical important difference was utilized [31].

The distributions of continuous variables were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and through evaluation of Quantile-Quantile Plots and Histograms [38]. Based on these results, potential between-group differences in age were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while PROM scores at each time point and changes in scores were compared between groups using t-tests [38]. Categorical participant characteristics (surgery type and gender) as well as COVID-19 questionnaire responses were compared between groups utilizing chi-squared or exact tests, as appropriate. Using chi-squared tests [38], we compared the proportion of participants meeting MCID cut-off points in a positive direction, as an indicator of clinical improvement, and a negative direction, as an indicator of clinical worsening. The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated by determining the absolute risk reduction (ARR) and dividing 1/ARR [38]. An a priori power analysis determined that a total of 84 participants would provide 90% power to detect a difference of 30% in worsening of PROMs between groups at an alpha level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 90 patients were enrolled in the study (45 in each group). There were no significant differences between the control vs ACT group in median (interquartile range [IQR]) age (63 (36-77) vs 65 (28-84) years, P = .448), proportion female (37.8% vs 33.3%, P = .660), or proportion indicated for TKA (60% vs 62.2%, P = .839), respectively. There were no significant differences between study groups in views or experience of the impact of COVID-19 at enrollment (Table 2 , all P > .05). Likewise, there were no significant differences between study groups for any PROMs at enrollment. Following the 2-week study period, PROMs were completed by 100% of participants (45 of 45 patients) in the ACT group and 89% of participants (40 of 45 participants) in the control group. All preintervention and postintervention PROMs are presented in Table 3 . All patients in the ACT group received a full 14 days of messages.

Table 2.

COVID-19 Questionnairea.

| Topic | Response | Control (n = 45) | ACT (n = 45) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of anxiety regarding: becoming infected with COVID-19 | None | 3 (6.67) | 6 (13.33) | .5746 |

| Minimal | 13 (28.89) | 12 (26.67) | ||

| Neutral | 11 (24.44) | 7 (15.56) | ||

| Moderate | 12 (26.67) | 16 (35.56) | ||

| Severe | 6 (13.33) | 4 (8.89) | ||

| Spreading COVID-19 to family member, friend, or colleague | None | 3 (6.67) | 6 (13.33) | .2570 |

| Minimal | 12 (26.67) | 14 (31.11) | ||

| Neutral | 8 (17.78) | 2 (4.44) | ||

| Moderate | 12 (26.67) | 15 (33.33) | ||

| Severe | 10 (22.22) | 8 (17.78) | ||

| Finances | None | 13 (28.89) | 19 (42.22) | .6111 |

| Minimal | 10 (22.22) | 11 (24.44) | ||

| Neutral | 9 (20.00) | 6 (13.33) | ||

| Moderate | 9 (20.00) | 7 (15.56) | ||

| Severe | 4 (8.89) | 2 (4.44) | ||

| Job security, FMLA, or disability | None | 20 (44.44) | 26 (57.78) | .3311 |

| Minimal | 5 (11.11) | 7 (15.56) | ||

| Neutral | 12 (26.67) | 5 (11.11) | ||

| Moderate | 6 (13.33) | 4 (8.89) | ||

| Severe | 2 (4.44) | 3 (6.67) | ||

| Not knowing how long surgery will be delayed | None | 2 (4.44) | 7 (15.56) | .4432 |

| Minimal | 7 (15.56) | 8 (17.78) | ||

| Neutral | 7 (15.56) | 5 (11.11) | ||

| Moderate | 19 (42.22) | 18 (40.00) | ||

| Severe | 10 (22.22) | 7 (15.56) | ||

| Has your knee or hip pain changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic? | Increased | 32 (71.11) | 21 (46.67) | .0542 |

| Decreased | 1 (2.22) | 3 (6.67) | ||

| Stayed the same | 12 (26.67) | 21 (46.67) | ||

| Knowing what you know about COVID-19, would you still have elected to move forward with your TKA/THA even if it would have put you at elevated risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and possibly death? | (n, %Yes) | 14 (31.1%) | 17 (37.8%) | .5057 |

| Do you believe that is it important to stop elective surgery/joint replacements in order to minimize the spread of COVID-19? | (n, %Yes) | 36 (80) | 39 (86.7%) | .3961 |

| Do you currently feel isolated or lonely? | (n, %Yes) | 12 (26.7%) | 8 (17.8%) | .3105 |

| Do you have the help you need at home to assist you while struggling with your arthritis? | (n, %Yes) | 40 (88.9%) | 37 (82.2%) | .3684 |

| Has your activity level changed since your surgery was canceled? | Increased | 4 (8.89) | 8 (17.78) | .4111 |

| Decreased | 21 (46.67) | 21 (46.67) | ||

| Stayed the Same | 20 (44.44) | 16 (35.56) | ||

| Reschedule status | Plan to reschedule in near future: | 40 (88.89) | 40 (88.89) | .7136 |

| Plan to delay Concern about contracting COVID-19 in hospital financial difficulties Other reason |

5 (11.11) 3 (6.67) 1 (2.22) 1 (2.22) |

5 (11.11) 5 (11.11) 0 0 |

ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; FMLA, Family Medical Leave Act; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

The COVID-19 questionnaire was administered prior to the intervention to both arms of the study.

Table 3.

Differences in PROMs From Preintervention to Postintervention Between the ACT and Control Groups.

| PROMs | Time Point | Control Group (Mean ± SD) | ACT Group (Mean ± SD) | P-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMIS MH | Pre | 46.8 ± 7.7 | 46.3 ± 9.8 | .818 | 0.26 |

| Post | 46.2 ± 7.8 | 47.2 ± 7.6 | .521 | ||

| Change | −0.6 | 0.9 | .230 | ||

| PROMIS PH | Pre | 41.5 ± 6.5 | 41.3 ± 6.7 | .903 | 0.42 |

| Post | 40.1 ± 6.6 | 41.5 ± 6.1 | .302 | ||

| Change | −1.3 | 0.3 | .055 | ||

| PROMIS Pain NRS | Pre | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | .360 | 0.32 |

| Post | 6.2 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | .123 | ||

| Change | 0.3 | 0.1 | .223 | ||

| PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a | Pre | 53.5 ± 6.2 | 52.2 ± 7 | .374 | 0.32 |

| Post | 54.1 ± 6.6 | 51.2 ± 6 | .035 | ||

| Change | 0.5 | −1.1 | .148 | ||

| PROMIS Pain Interference | Pre | 61.1 ± 5.3 | 62.8 ± 7.4 | .220 | 0.15 |

| Post | 61 ± 6 | 62.1 ± 6.8 | .416 | ||

| Change | −0.1 | −0.7 | .500 | ||

| PROMIS Anxiety | Pre | 53.6 ± 9.4 | 54 ± 10.3 | .845 | 0 |

| Post | 52.6 ± 10.1 | 53 ± 10.5 | .848 | ||

| Change | −1 | −1 | .995 | ||

| HOOS JR | Pre | 52.5 ± 11 | 51 ± 10.4 | .686 | 0.18 |

| Post | 49.9 ± 11.8 | 49.6 ± 10.1 | .950 | ||

| Change | −2.6 | −1.3 | .612 | ||

| KOOS JR | Pre | 46.9 ± 15.1 | 45 ± 18.2 | .687 | 0.84 |

| Post | 40.6 ± 19.4 | 47.4 ± 15 | .159 | ||

| Change | −6.3 | 2.4 | .004 |

PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; SD, standard deviation; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System; MH, Mental Health; PH, Physical Health; NRS, numeric rating scale; HOOS, Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement; KOOS, Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement.

Bold values indicate the statistical significance.

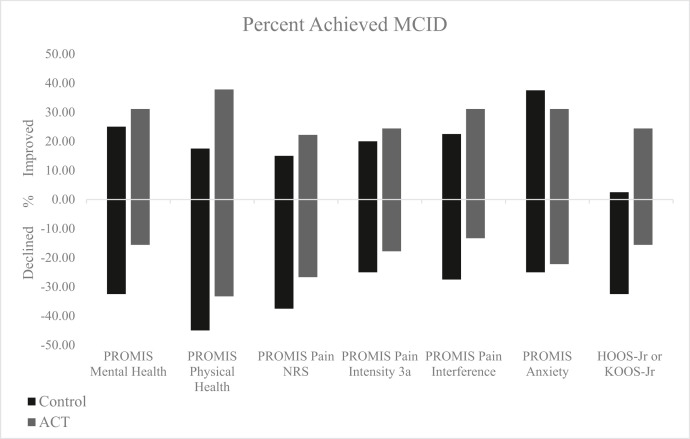

All MCID analyses are presented in Table 4 and Figure 1 . Thirty-eight percent of participants in the ACT group achieved an improvement greater than or equal to MCID on the PROMIS PH compared to 17.5% in the control group (P = .038; NNT 5). Twenty-four percent of participants in the ACT group improved by an MCID on the joint-specific HOOS JR or KOOS JR compared to 2.5% in the control group (P = .004; NNT 5). Sixteen percent of ACT group participants experienced a clinically important decline in the HOOS JR or KOOS JR compared to 33% in the control group (P = .066). Eighteen percent of participants in the ACT group achieved an improvement in MCID on the HOOS JR with no participants having an improvement in the control group (P = .227; Fig. 1). Twenty-nine percent of TKA participants experienced a clinically important improvement in the KOOS JR compared to 4.2% in the control group (P = .028; NNT 5) (Fig. 1). Fourteen percent of ACT group patients experienced a decline in the KOOS JR greater than MCID compared to 41.7% for the control group (P = .027; NNT 4). Although there was a greater proportion who experienced an increase (>10%) in pain severity (PROMIS Pain Intensity NRS) and interference (PROMIS Pain Interference) in the control vs ACT group, these PROMs did not reach statistical significance (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Table 4.

The Percentage of Each Group That Achieved the MCID on Each Patient-Reported Outcome Measure.

| Measure | n (%) ≥ MCID+ |

P-Value | n (%) ≤ MCID− |

P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 40) | ACT (N = 45) | Control (N = 40) | ACT (N = 45) | |||

| PROMIS Mental Health (higher is better, so V2-V1) | 10 (25.0%) | 14 (31.1%) | .5321 | 13 (32.5%) | 7 (15.6%) | .0660 |

| PROMIS Physical Health (higher better, so V2-V1) | 7 (17.5%) | 17 (37.8%) | .0382 | 18 (45.0%) | 15 (33.3%) | .2706 |

| PROMIS Pain NRS (lower is better, so V1-V2) | 6 (15.0%) | 10 (22.2%) | .3952 | 15 (37.5%) | 12 (26.7%) | .2843 |

| PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a (lower is better, so V1-V2) | 8 (20.0%) | 11 (24.4%) | .6235 | 10 (25.0%) | 8 (17.8%) | .4159 |

| PROMIS Pain Interference (lower is better, so V1-V2) | 9 (22.5%) | 14 (31.1%) | .3724 | 11 (27.5%) | 6 (13.3%) | .1031 |

| PROMIS Anxiety (lower is better, so V1-V2) | 15 (37.5%) | 14 (31.1%) | .5352 | 10 (25.0%) | 10 (22.2%) | .7631 |

| HOOS JR or KOOS JR (higher is better, so V2-V1) | 1 (2.5%) | 11 (24.4%) | .0037 | 13 (32.5%) | 7 (15.6%) | .0660 |

MCID, minimal clinically important difference; ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System; NRS, numeric rating scale; HOOS, Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement; KOOS, Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement.

Bold values indicate the statistical significance.

Fig. 1.

The percentage of participants who improved and declined between the control group and the ACT group for both total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System; HOOS, Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; KOOS, Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score.

Twenty-nine percent of participants asked for more messages during the course of the study on at least 1 day. The mean number of days more messaging was requested was 4.23 ± 3.4 days. The mean number of requests per day was 1.69 ± 1.82 with 72% of participants requesting more messaging one time per day. Seventy-five percent of participants indicated that they would recommend the mobile phone ACT messaging system to a family member or loved one if they were experiencing delay in their surgical care.

Discussion

Participants in the ACT arm reported stable or improved responses to administer PROMs compared to a consistent decline in the control group across PROMs at the end of the 2-week study period (Fig. 1). The most robust response to our intervention was experienced by those who had their TKA procedure postponed. A preoperative decline in PROMs is important as prior work has demonstrated that declining preoperative function and pain scores in the setting of THA and TKA portend to lower postoperative functional status [39,40]. Over the 2-week study period, the control group in our study experienced a decay and worsening of PROMs which is consistent with findings from a survey during the early pandemic period delivered by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons [22]. Contrastingly, the ACT group experienced either a clinically important improvement from their preintervention state or a smaller decline than the control group across PROMs (Table 4, Fig. 1). We suspect that abrupt cancellation of surgery with an unknown date of rescheduling during the COVID-19 pandemic may have had an impact on participants’ pain and function. This is supported by the relatively large percentage of patients in the control group who experienced a clinically significant decline in multiple PROMs over the study period. Our study found that a simple, 2-week intervention focusing on twice daily text messages delivered by a “Chatbot” was able to prevent clinically significant decline, and at times improve, multiple PROMs for patients who are delayed in receiving surgical care of their arthritic hip or knee condition. These findings have large implications for patients who may experience an unexpected surgical delay due to a variety of reasons. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not uncommon for patients to have surgery postponed for additional preoperative testing or optimization. Our results indicate that it is likely that THA and TKA patients who encounter a surgical delay during the COVID-19 pandemic may have a clinically significant decline in their hip or knee function. As such, we believe that measures should be put in place to preserve their functional status and prevent worsening of symptoms given the negative impact of declining preoperative PROMs on postoperative outcomes [39,40]. Our described mobile phone ACT-based communication protocol can be utilized to stabilize pain and joint-specific PROMs in the setting of surgical delay of THA and TKA. Additionally, this technology and communication intervention could be studied in other patient populations including patients with minimal and less severe osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.

ACT has demonstrated positive results in the management of chronic pain across multiple patient populations [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30]]. Previous work also demonstrated decreased opioid utilization and pain scores at 3 months after various orthopedic procedures, including THA and TKA, when utilizing a one time, preoperative 5-hour ACT interventional workshop [30]. Additionally, healthcare communication strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic have necessitated physical distancing between patients and the healthcare system. Telehealth solutions consisting of automated mobile phone messaging have been adopted in the United States [3] and abroad [1,2] during the pandemic with high reported success. We demonstrate that ACT delivered through an automated mobile phone messaging robot influenced various PROMs in the setting of delayed THA and TKA. Three-quarters of patients in our ACT intervention arm stated they would recommend this technology and method of communication in the future if a family member was going to experience a delay in their surgical care. Our findings during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that our software messaging platform is an acceptable form of communication with a focus on a contextual psychological intervention. Healthcare systems should consider utilization of ACT and mobile phone messaging robots to communicate with patients who are experiencing delays in their surgical care.

This trial has limitations. The intervention was limited to 2 weeks in duration which might not be the ideal duration for this intervention in this population. At the initiation of our investigation, there was no way to identify how long the pandemic would continue. We determined a two-week study period with a two-week follow-up period would most likely allow us to complete the study while still in the pandemic conditions the study was initiated under. Further study of ideal length in time of intervention utilizing this technology and communication is warranted. Additionally, the length of the effect of our intervention is unclear given our follow-up time period. Participants received multiple PROMs in this investigation which may or may not fully encompass the complexities of their pain, anxiety, and hip and knee function. Although we included in this study what we felt to be the most appropriate PROMs, other questionnaires may have added to our findings. Additionally, the best methods for determining an MCID for a PROM has been greatly debated with no definitive conclusion. Utilization of alternative MCID cutoffs or formulation methods may alter the clinical significance of our results. Finally, our results represent the findings from a Midwestern and largely rural patient population. Further similar investigations should be performed in other demographic regions and in locales representative of the broader population in terms of socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and political views that may have effected personal responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that ACT delivered via an automated mobile phone messaging robot can prevent clinically significant decline, and at times improve physical function and joint-specific PROMs in patients who experience a surgical delay of THA or TKA due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future investigations should consider the longer term impact of our designed intervention and should also consider altering the duration of the ACT software messaging protocol in order to determine the ideal duration and timing of delivered therapy. Healthcare systems should consider utilization of an ACT messaging protocol to preserve physical function and joint-specific PROMs when caring for patients with operative hip and knee arthritis who are experiencing surgical delay.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors of this paper have disclosed potential or pertinent conflicts of interest, which may include receipt of payment, either direct or indirect, institutional support, or association with an entity in the biomedical field which may be perceived to have potential conflict of interest with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.12.006.

Appendix

| Message Protocol | Random Messages (Text More) | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 AM | Maintaining focus on what you value most in life is sometimes difficult. Do not let momentary discomforts due to pain or the COVID pandemic take away from what you want most in life. Pick 3 things that matter most to you in life. Remind yourself of these 3 things over the course of the day and in the coming weeks. Text more for more tips | Remind yourself throughout your day what you value most in life. Take time to focus on 3 things that matter most to you in life and move past any feelings of discomfort, pain, or anxiety that arise for you might experience today. Text more for more tips |

| Day 1 PM | Stop for a moment and remember the 3 values you identified earlier today. Remind yourself how important these values are in your life. As your day comes to an end, remember that YOU are in control of your thoughts. We encourage you to end your day focusing on your 3 core values. Text more for more tips | Remember you are in control of your thoughts. Even when thoughts of pain and anxiety arise you can choose to acknowledge and move through these feelings to things that are hopeful and define who you truly are. Text more for more tips |

| Day 2 AM | Joint pain can be part of arthritis. Pain is something you can choose to observe and not something that requires you to act. Your life goals, values, and subsequent actions determine what your life looks like on a daily basis. If you are experiencing some pain today we encourage you to acknowledge it and then turn your focus to the things in your life that matter most to you. Text more for more tips | Your life goals, values, and subsequent actions determine what your life looks like on a daily basis. If you are experiencing some pain or anxious thoughts today we encourage you to acknowledge these feelings and then actively turn your focus to the things in your life that matter most to you. Text more for more tips |

| Day 2 PM | Feelings of pain and feelings about your experience of pain are normal in the setting of arthritis. Acknowledge and accept these feelings as part of your current reality. Remember how you feel at this moment is temporary and your life will continue as arthritis is only a minor part of who you are. Choose to focus your mind on pleasant feelings or thoughts that you experienced today. Text more for more tips | You can make any feelings of anxious thoughts or discomfort in your joints temporary. Choose to acknowledge these feelings and then actively take your focus to things that bring hope and joy to your life. Text more for more tips |

| Day 3 AM | Awareness of the present moment and your breathing may change with pain-related emotions or thoughts. Remember you can always count on your breathing to bring you back to the present moment and help you move through your current experience of pain or anxiety you may be feeling. Focus on taking slow and deep breaths today. Text more for more tips | Focus on taking slow and deep breaths today. Any time you notice feelings of pain, discomfort, or anxiety choose to focus on your breathing and take 5 or 6 slow deep inhales and exhales. Know that the act of slow, deep breathing calms your body and mind. Text more for more tips |

| Day 3 PM | Breathing helps bring awareness about how you are reacting to thoughts in the moment. You can also use breathing to help you focus on what you want in life and what is important to you. End your day in a calm and relaxed state as you focus on taking deep, slow breaths. Remember, you are in charge of your breath, your thoughts and emotions, and ultimately how you experience everything that is going on around you. Text more for more tips | Remember, you are in charge of your thoughts, emotions, and ultimately how you experience everything that is going on around you. You can use breathing to help you focus on what you want in life and what is important to you. Text more for more tips |

| Day 4 AM | Pause and reflect on the aspects of your life that bring meaning and purpose. Think of 3 life goals or motivations that you want to focus on today. Your journey through difficult times is an opportunity to refocus your life on what is truly important to you. Text more for more tips | Pause and reflect on the aspects of your life that bring meaning and purpose. Think of 3 life goals or motivations that you want to focus on today. Your journey through difficult times is an opportunity to refocus your life on what is truly important to you. Text more for more tips |

| Day 4 PM | Before today ends think about how the values and goals you identified earlier were part of how you experienced the day. Focus on these values and goals and imagine how tomorrow you will build upon what you accomplished today. Text more for more tips | You get to choose how you move and interact with the world. Do not let distracting thoughts of pain, discomfort, or anxious thoughts distract you from living how you want to live. Remember your circumstances are temporary and continue to choose to focus and spend your time on things that matter most to you in life. Text more for more tips |

| Day 5 AM | We cannot change that a feeling or thought may arise, but we can choose how we respond to our feelings and thoughts. Remember that dwelling on pain, discouraging feelings, and anxious thoughts about current world events are NOT consistent with your life goals, and values. Observe thoughts that try to move you away from your values and only act on things that are compatible with who you want to be and what matters most in your life. Text more for more tips | We cannot change that a feeling or thought may arise, but we can choose how we respond to our feelings and thoughts. Remember that dwelling on pain, discouraging feelings, and anxious thoughts about current world events are NOT consistent with your life goals and values. Observe thoughts that try to move you away from your values and only act on things that are compatible with who you want to be and what matters most in your life. Text more for more tips |

| Day 5 PM | Notice your thoughts and feelings today about how your pain and world events might be affecting you. Remember that arthritic pain and the COVID pandemic do not define who you are or how you experience life. Your life is much larger and fuller than these things. Spend some time tonight thinking about something or someone important to you. Text more for more tips | Remaining actively engaged in life during stressful times can be difficult. In these moments it is important to focus on the things that matter most to you in life. Take time to reflect on your goals and values and allow them to support you in the moments you find it difficult to remain positive today. Remember YOU are in charge of your thoughts and feelings. Text more for more tips |

| Day 6 AM | Life requires you to act. We previously discussed your life goals, meaning, and purpose. Take action today and move closer toward what you want in life. Recognize that pain and anxious thoughts may be present but make the choice that they will not impede your progress toward what you really want in life. Be present in the moment and ensure your actions remain true to what you want most. All actions you take, no matter how small, are important in making this life what you want despite your circumstances. Text more for more tips | Life requires you to act. We previously discussed your life goals, meaning, and purpose. Take action today and move closer toward what you want in life. Recognize that pain and anxious thoughts may be present but make the choice that it will not impede your progress toward what you really want in life. Be present in the moment and ensure your actions remain true to what you want most. All actions you take, no matter how small, are important in making this life what you want despite your circumstances. Text more for more tips |

| Day 6 PM | Now that your day is winding down, reflect on what motivated your actions throughout the day. Intrusive thoughts, emotional distress, and pain may show up periodically during your day, but these thoughts and feelings do not need get to direct the actions you take. Remember that YOU decide how to live in a way that reflects what matters to YOU. Text more for more tips | Thoughts of pain and anxiety may be entering your daily life. Remember you do not need to avoid these feelings and thoughts. Recognize they may be a part of your day but you can CHOOSE to move past them as you can make them only momentary. Take a deep breath, and as you breathe out allow yourself to focus on something you are thankful for today. Text more for more tips |

| Day 7 AM | Living with arthritis can involve pain in your joints. By accepting this you can control your actions related to pain and choose how big of a role pain plays in your daily life. Know that you are not doing further damage to your joint by moving and enjoying life. Acknowledge the pain you might be having in your joint and choose to continue to do the things you enjoy. Text more for more tips | Living with arthritis can involve pain in your joints. By accepting this you can control your actions related to pain and choose how big of a role pain plays in your daily life. Know that you are not doing further damage to your joint by moving and enjoying life. Acknowledge the pain you might be having in your joint and choose to continue to do the things you enjoy. Text more for more tips. |

| Day 7 PM | Reflect back on today. Think about the role that pain played in the activities you took part in. Take notice of any instances where pain slowed down your life and try to improve on those tomorrow. Remember, pain might be part of your life, but not what dictates it. Continue to move forward with a focus on what matters most to you in life and make pain and anxiety take a back seat. Find and focus on one thing you can be thankful for today. Text more for more tips | Engaging in activities that we enjoy can be difficult given current circumstances. Anything that brings you joy and meaning is important. Whether you enjoy a specific TV show, taking a walk, or reading a good book, do something today that you enjoy. Text more for more tips |

| Day 8 AM | If you experience pain in your joints know that the feeling is real but what it actually represents is not what you might think. Our mind is capable of making us feel pain, even though there is no damage going on in our body. Pause, become more aware in the moment and choose to focus on thoughts of what is good and hopeful in your life. Text more for more tips | Happiness and having fun are values that are sometimes easy to forget during this difficult time. Reflect on what activities you can do today that bring joy and meaning to your life. Make it your goal today, and every day, to do at least one thing that brings your life joy and meaning. Text more for more tips |

| Day 8 PM | Thoughts of pain and anxiety may be entering your daily life. Remember you do not need to avoid these feelings and thoughts. Recognize they may be a part of your day but you can CHOOSE to move past them as you can make them only momentary. Take a deep breath, and as you breathe out allow yourself to focus on something you are thankful for today. Text more for more tips | Don't let your joint pain limit what you do today. Make a choice that you will do what you want to do regardless of how your body feels. Don't judge yourself if you need to walk a little slower or not bend or move in quite the same way you used to when doing the things you love. Choose to move today! Text more for more tips |

| Day 9 AM | Remaining actively engaged in life during stressful times can be difficult. In these moments it is important to focus on the things that matter most to you in life. Take time to reflect on your goals and values and allow them to support you in the moments you find difficult to remain positive today. Remember YOU are in charge of your thoughts and feelings. Text more for more tips | Emotional distress and joint pain may be present in your daily life. Acknowledging their presence helps diminish their possible negative impact. Remember that you are not defined by the events going on in the world or by the aches and pains of your body. Today, take time to focus on what you value most in life and choose for these values to define your day. Text more for more tips |

| Day 9 PM | Take several minutes this evening and remind yourself of what matters most to you in life. Imagine things you can do tomorrow to move closer to these values. Remember to define your day by how you move toward what matters most to you in life and not by the momentary feelings of discomfort and anxious thoughts that many people are feeling right now. You are not alone, keep actively moving forward on a daily basis. Text more for more tips | Moving is good for your body, even if it causes pain and discomfort in your joints. Choosing to work through feelings of pain and discomfort can lead to enjoyment of activities and a more full life. Choose to overcome momentary discomforts today when you move and know you have accomplished great things with even small movements and tasks! Text more for more tips |

| Day 10 AM | Emotional distress and joint pain may be present in your daily life. Acknowledging their presence helps diminish their possible negative impact. Remember that you are not defined by the events going on in the world or by the aches and pains of your body. Today, take time to focus on what you value most in life and choose for these values to take your focus and define your day. Text more for more tips | You can choose to alter how you move if it helps ease discomfort you might have in your joints. Be open to finding new ways of moving your body in an effort to do the things you enjoy and love in life. Remember you are not defined by momentary thoughts of pain and anxiety but you are defined by your actions and things you choose to value in life. Text more for more tips |

| Day 10 PM | Your current everyday life may involve pain, discomfort, and emotional distress. Remember you are not alone and these circumstances are only temporary. Willingness to notice and move past your current feelings and focus on things that are most important to you is key to successfully navigating your life! Text more for more tips | Your current everyday life may involve pain, discomfort, and emotional distress. Remember you are not alone and these circumstances are only temporary. Willingness to notice and move past your current feelings and focus on things that are most important to you is key to successfully navigating your life! Text more for more tips |

| Day 11 AM | Engaging in activities that we enjoy can be difficult given current circumstances. Anything that brings you joy and meaning is important. Whether you enjoy a specific TV show, taking a walk, or reading a good book, do something today that you enjoy | |

| Day 11 PM | Take some time before your day ends and do 1 thing that is just for you. This could be preparing and eating a meal you love, taking some deep breaths, or watching your favorite TV show. Despite how your body may be feeling, determine 1 thing you want to do before your day ends and take time to enjoy life. Text more for more tips | |

| Day 12 AM | Remember who you are today. Remember your values, goals, and aspirations in life. Notice that the thoughts, emotions, and discomfort you may currently feel can blur your sense of self and keep you from doing things consistent with your values. Even though anxious thoughts and pain may show up, they do not need to determine what you do. Not reacting to these thoughts or feelings about yourself or your pain is success! Text more for more tips | |

| Day 12 PM | Remember you can change the way you move and interact with the world in order to limit your joint pain. Be creative and experiment with different ways of moving today. Notice what helps and what doesn't. You are NOT causing more damage to your joints by moving the way you want to move. Choose to be active and move today. Do not let pain or anxious thoughts limit who you are. Text more for more tips | |

| Day 13 AM | Taking actions, moment by moment, that move you toward the things that matter most to you in life is the most effective and satisfying way to live life. Carrying out any action that is in-line with your goals and values is a major win, just like adding a correct new piece to a puzzle. Text more for more tips | |

| Day 13 PM | As your day comes to an end, think back on the wins you had today. Use these wins to motivate you and keep you moving when things are difficult. The wins will keep coming and the puzzle will continue to take shape as long as you keep taking actions that reflect the things that matter most to you in life. Text more for more tips | |

| Day 14 AM | Happiness and having fun are values that are sometimes easy to forget during difficult times. Reflect on what activities you can do today that bring joy and meaning to your life. Make it your goal today, and every day, to do at least one thing that brings your life joy and meaning. Text more for more tips | |

| Day 14 PM | Remember you are not alone in this process and that we are here for you! You are much, much more that any feelings you have about joint pain and current world events. Enjoy your rest tonight and get ready for a hopeful new today tomorrow! Text more for more tips |

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Organization WH COVID-19 Information- SMS Message Library who.int: WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/covid-19-message-library [Accessed 04.04.21]

- 2.Organization W.H., Union I.T. ITU-WHO Joint Statement: unleashing information technology to defeat COVID-19 who.int. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/20-04-2020-itu-who-joint-statement-unleashing-information-technology-to-defeat-covid-19 [Accessed 20.04.21]

- 3.Rapid Implementation of an Outpatient COVID-19 Monitoring Program NEJM catalyst innovations in care delivery. https://catalyst-nejm-org.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/doi/full/10.1056/cat.20.0214 [Accessed 16.06.20]

- 4.Anthony C.A., Polgreen L.A., Chounramany J., Foster E.D., Goerdt C.J., Miller M.L., et al. Outpatient blood pressure monitoring using bi–directional text messaging. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthony C.A., Volkmar A., Shah A.S., Willey M., Karam M., Marsh J.L. Communication with orthopedic trauma patients via an automated mobile phone messaging robot. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:504–509. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock K.J., Rice O.M., Anthony C.A., Glass N., Hogue M., Karam M., et al. Efficacy of multimodal analgesic injections in operatively treated ankle fractures: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:2194–2202. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.19.00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson S.E., Adams A.J., Buczek M.J., Anthony C.A., Shah A.S. Postoperative pain and opioid use in children with supracondylar humeral fractures: balancing analgesia and opioid stewardship. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:119–126. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.18.00657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polgreen L.A., Anthony C., Carr L., Simmering J.E., Evans N.J., Foster E.D., et al. The effect of automated text messaging and goal setting on pedometer adherence and physical activity in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anthony C.A., Lawler E.A., Glass N.A., McDonald K., Shah A.S. Delivery of patient-reported outcome instruments by automated mobile phone text messaging. Hand (N Y) 2017;12:614–621. doi: 10.1177/1558944716672201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott E.J., Anthony C.A., Rooney P., Lynch T.S., Willey M.C., Westermann R.W. Mobile phone administration of hip-specific patient-reported outcome instruments correlates highly with in-office administration. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e41–e46. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-18-00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthony C.A., Peterson A.R. Utilization of a text-messaging robot to assess intraday variation in concussion symptom severity scores. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:149–152. doi: 10.1097/jsm.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellor X., Buczek M.J., Adams A.J., Lawrence J.T.R., Ganley T.J., Shah A.S. Collection of common knee patient-reported outcome instruments by automated mobile phone text messaging in pediatric sports medicine. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40:e91–e95. doi: 10.1097/bpo.0000000000001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandapur Y., Kianoush S., Kelli H.M., Misra S., Urrea B., Blaha M.J., et al. The role of mHealth for improving medication adherence in patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2016;2:237–244. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y.Y., Dang F.P., Zhai T.T., Li H.J., Wang R.J., Ren J.J. The effect of text message reminders on medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e18353. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin C.L., Mistry N., Boneh J., Li H., Lazebnik R. Text message reminders increase appointment adherence in a pediatric clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Pediatr. 2016;2016:8487378. doi: 10.1155/2016/8487378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junod Perron N., Dao M.D., Righini N.C., Humair J.P., Broers B., Narring F., et al. Text-messaging versus telephone reminders to reduce missed appointments in an academic primary care clinic: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:125. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zahr R.S., Anthony C.A., Polgreen P.M., Simmering J.E., Goerdt C.J., Hoth A.B., et al. A texting-based blood pressure surveillance intervention. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21:1463–1470. doi: 10.1111/jch.13674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day M.A., Anthony C.A., Bedard N.A., Glass N.A., Clark C.R., Callaghan J.J., et al. Increasing perioperative communication with automated mobile phone messaging in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell K.J., Louie P.K., Bohl D.D., Edmiston T., Mikhail C., Li J., et al. A novel, automated text-messaging system is effective in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:145–151. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.17.01505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goz V., Anthony C., Pugely A., Lawrence B., Spina N., Brodke D., et al. Software-based postoperative communication with patients undergoing spine surgery. Glob Spine J. 2019;9:14–17. doi: 10.1177/2192568217728047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedard N.A., Elkins J.M., Brown T.S. Effect of COVID-19 on hip and knee arthroplasty surgical volume in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S45–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown T.S., Bedard N.A., Rojas E.O., Anthony C.A., Schwarzkopf R., Barnes C.L., et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S49–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain A., Jain P., Aggarwal S. SARS-CoV-2 impact on elective orthopaedic surgery: implications for post-pandemic recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:e68. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.20.00602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batten S.V. SAGE; Los Angeles, California; London, England: 2011. Essentials of acceptance and commitment therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav Ther. 2004;35:639–665. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahl J., Wilson K.G., Nilsson A. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the treatment of persons at risk for long-term disability resulting from stress and pain symptoms: a preliminary randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2004;35:785–801. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80020-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers M.B., Vörding M.B.Z.V.S., Emmelkamp P.M. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:73–80. doi: 10.1159/000190790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes L.S., Clark J., Colclough J.A., Dale E., McMillan D. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:552–568. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCracken L.M., Vowles K.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: model, process, and progress. Am Psychol. 2014;69:178–187. doi: 10.1037/a0035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dindo L., Zimmerman M.B., Hadlandsmyth K., StMarie B., Embree J., Marchman J., et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for prevention of chronic post-surgical pain and opioid use in at-risk veterans: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Pain. 2018;19:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman G.R., Sloan J.A., Wyrwich K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.Mlr.0000062554.74615.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asher A.L., Kerezoudis P., Mummaneni P.V., Bisson E.F., Glassman S.D., Foley K.T., et al. Defining the minimum clinically important difference for grade I degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: insights from the quality outcomes database. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E2. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.Focus17554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salaffi F., Stancati A., Silvestri C.A., Ciapetti A., Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Concoff A., Rosen J., Fu F., Bhandari M., Boyer K., Karlsson J., et al. A comparison of treatment effects for nonsurgical therapies and the minimum clinically important difference in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. JBJS Rev. 2019;7:e5. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.Rvw.18.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee A.C., Driban J.B., Price L.L., Harvey W.F., Rodday A.M., Wang C. Responsiveness and minimally important differences for 4 patient-reported outcomes measurement information system short forms: physical function, pain interference, depression, and anxiety in knee osteoarthritis. J Pain. 2017;18:1096–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo A.C., Giori N.J., Bowe T.R., Manfredi L., Lalani N.F., Nordin D.A., et al. Comparing methods to determine the minimal clinically important differences in patient-reported outcome measures for veterans undergoing elective total hip or knee arthroplasty in veterans health administration hospitals. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:404–411. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalil L.S., Darrith B., Franovic S., Davis J.J., Weir R.M., Banka T.R. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global health short forms demonstrate responsiveness in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:1540–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J. 2nd ed. L. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, New Jersey: 2014. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences/Jacob Cohen. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fortin P.R., Clarke A.E., Joseph L., Liang M.H., Tanzer M., Ferland D., et al. Outcomes of total hip and knee replacement: preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at six months after surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1722–1728. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1722::Aid-anr22>3.0.Co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan M., Tanzer M., Reardon G., Amirault D., Dunbar M., Stanish W. The role of presurgical expectancies in predicting pain and function one year following total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2011;152:2287–2293. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.