Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed primary care (PC), and policies aimed at integrating it into provincial health systems, to a “shock test.” This paper draws on documentary analysis and qualitative interviews with PC and health system stakeholders to examine shifts in Alberta's pre-pandemic PC integration model during the first nine months of the pandemic. We begin with an account of three elements of the province's pre-pandemic model: finance, health authority activity and community activity. We describe these elements as they shifted, focusing on two indicators of change: novel virtual care billing codes and personal protective equipment (PPE) distribution channels. We draw out policy planning lessons for improving PC integration under normal and future pandemic conditions, namely, by facilitating rapid updates of virtual care billing codes, analyses of the impact of care delivery and backstopping of PPE markets and supply chains for PC.

Abstract

La pandémie de COVID-19 a soumis les soins de santé primaires (SSP), de même que les politiques visant à les intégrer dans les systèmes de santé provinciaux, à un « test de choc ». Cet article s'appuie sur une analyse documentaire et des entretiens qualitatifs avec des intervenants des SSP et du système de santé pour examiner les changements dans le modèle d'intégration pré-pandémique des SSP en Alberta au cours des neuf premiers mois de la pandémie. Nous commençons par rendre compte de trois éléments du modèle pré-pandémique de la province: les finances, l'activité des autorités sanitaires et l'activité communautaire. Nous décrivons ces éléments au fur et à mesure de leur évolution, en nous concentrant sur deux indicateurs de changement: les nouveaux codes de facturation des soins virtuels et les canaux de distribution des équipements de protection individuelle (EPI). Nous tirons des leçons de planification politique pour améliorer l'intégration des SSP dans des conditions normales ou de pandémie éventuelles, notamment en facilitant la mise à jour rapide des codes de facturation des soins virtuels, en analysant l'impact de la prestation des soins et en soutenant les marchés et les chaînes d'approvisionnement des EPI pour les SSP.

Introduction

Integrating primary care (PC) into broader health systems has been a major policy objective in Canada, and around the world, over the last 20 years (Marchildon and Hutchinson 2016; Tenbensel and Burau 2017; Wang et al. 2011). With a broad range of definitions available for what integration in the health and social services might entail (Armitage et al. 2009), there have been sustained attempts to draw traditionally independent PC more closely into the governance and operations of provincial systems, which are predominantly focused on the provision of acute care (Bichel et al. 2011; Espinosa-González et al. 2020; Laberge and Gaudreault 2019; Solomon et al. 2013). These efforts have included the deployment of alternative funding models (Government of Alberta n.d.; HQCA 2019; Laberge and Gaudreault 2019; Lange et al. 2020) and networked service innovations exemplified by the Patient's Medical Home (AHS n.d.; Government of Québec n.d.) (http://www.lhins.on.ca/; https://patientsmedicalhome.ca/). With the intended benefits of PC integration often focused on improving the continuity of care and reducing costs (Galea and Kruk 2019; Marchildon and Di Matteo 2015; Rowan et al. 2007; Valentijn et al. 2013), the SARS-CoV-2 virus has highlighted a rather different policy goal: improved health system resilience. Indeed, service integration in health systems has been identified as amplifying those systems' abilities to absorb and adapt to a shock such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Hanefeld et al. 2018; Legido-Quigley et al. 2020). With healthcare service provision and the PC integration models of all Canadian provinces (Chakraborty et al. 2020) shock-tested by the pandemic, this paper takes Alberta as a policy case study. We examine how the pandemic shifted key elements of the province's pre-pandemic PC integration model using two specific indicators of change to draw out broadly applicable lessons for the present and future pandemics.

We begin by describing the province's broader pre-pandemic integration model, detailing that model's finance, health authority activity and community activity elements. We then shift to an account of the on-the-ground realities of PC integration in the first 10 months of the COVID-19 response. Drawing on documentary evidence and interviews conducted between March and December 2020, we describe significant shifts in the model's elements as Alberta's system generated novel billing codes and personal protective equipment (PPE) distribution channels for PC. As PC billing codes for virtual care and PPE distribution to PC clinics are pandemic-induced challenges that have been encountered across Canada, we use Alberta's experience to shed light on generalizable policy processes and considerations that will improve access to care in future responses. Although other jurisdictions – including Canada's other provinces and territories – will each have their own particular constellation of finance, health authority and community activity in place, what follows highlights the common challenges presented by a precipitous drop in both patient access to PC and the revenue PC physicians were able to generate. Our aim is not to compare and contrast integration models across jurisdictions, but rather to draw out generalizable policy considerations from specific changes to Alberta's integration model as it responded to the pandemic.

Alberta's Pre-Pandemic PC Integration Model

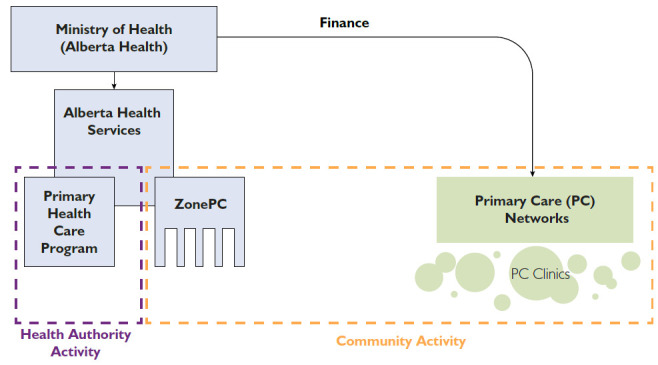

Alberta has the largest centralized healthcare system in Canada, with over 650 facilities across the province managed by a single health authority – Alberta Health Services (AHS) – delivering care in five geographically based “health zones.” AHS, as the single authority, formed the zones to provide “decision making at a local level” (AHS 2019) that draws on input from the community, healthcare staff, patients, clients and stakeholders to plan and deliver services. The facilities in these zones deliver acute, long-term, public health and some urgent care, with the province's more than 1,180 PC clinics owned and operated by independent family doctors operating outside AHS control. Built on this foundation, the province's PC integration model (Figure 1) is composed of three key elements: finance, health authority activity and community activity.

Figure 1.

Alberta's pre-pandemic PC integration model

As in many other provinces, Alberta's Ministry of Health (MoH) finances PC directly, with the vast majority of PC physicians billing the government on a fee-for-service basis. In an MoH budget of $20.8 billion, these PC services account for 7.17%, or $1.48 billion annually (Government of Alberta 2020a). Most PC practices are small, with services delivered by independent practitioners. Many, but not all, of these physicians opt to affiliate themselves with primary care networks (PCNs). The PCNs are financed through grants from the MoH that are based on the size of their members' patient panels and they provide PC services that would be beyond the capacity of individual clinics (Leslie et al. 2020b), such as access to nutritionists, psychologists or patient panel management expertise. Despite AHS being the province's single health authority, PC physicians do not share a governance or accountability relationship with the organization. Rather, PC fee guides are established through direct negotiations between the MoH and the provincial medical association.

While these circumstances might imply that AHS is uninvolved in PC, this is not the case. PC-focused health authority activity is part of the AHS portfolio of work. As noted, AHS operates several urgent and family care clinics (https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/) and – more significantly – maintains a pair of PC-focused divisions: the Primary Health Care Program (AHS-PHCP) and one operational group in each of the five zones (AHS-ZonePC). Both AHS-PHCP and AHS-ZonePC develop and support unique programming. Highlighting the health authority's acute and long-term care focus, the AHS-PHCP relies on a staff of less than 100 to conduct its work while embedded in an organization that employs more than 110,000. Within these constraints, AHS-PHCP works at a provincial level to provide PC clinics, the PCNs and ZonePC groups with system-wide guidelines and to act as a bridge between personnel in the MoH and community-based PC (https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/).

In contrast, the AHS-ZonePC groups are focused on zonal issues – not provincial ones – and they work with the PCNs. The zones are arranged in a way that creates a dyad composed of a zonal lead physician from “inside” the health authority (AHS-ZonePC) and a counterpart physician from “outside” the health authority who works in community PC. Zone dyads co-plan activities and service provision priorities with the PCNs, which are formed as joint ventures with AHS. A joint venture, here, is a formal governance partnership between AHS and the PC physicians who are the PCN members. The PCNs have developed into this form and governance structure over the last 18 years (Leslie et al. 2020b), with the MoH receiving accountability on specific performance metrics (Auditor General of Alberta 2017) for its capitation-based grants. There are presently 41 PCNs, each with its own priorities and modes of operating within a set of broader governance principles that emphasize co-planning with AHS, the delivery of the Patient's Medical Home (https://patientsmedicalhome.ca/) and the attachment of patients to PC (Alberta Medical Association Primary Care Alliance Board 2013; Auditor General of Alberta 2017). In this way, the work of the AHS-ZonePC and PCNs represents the PC integration model's community activity element.

Alberta's pre-pandemic PC integration model, then, is one that combines direct financing from the MoH to family physicians, the health authority activities of the AHS-PHCP and the community activities of the AHS-ZonePC working with the PCNs. The following sections track some of the key pandemic-induced shifts and re-combinations of these three elements.

Materials and Method

The data we use here are part of a larger qualitative study examining the communication and implementation of policy in Alberta's COVID-19 response (CIHR 2020). Our research approach focuses on understanding experiences and perspectives across the provincial health system during the pandemic (Leslie et al. 2020a). Myles Leslie (ML), Raad Fadaak (RF) and Nicole Pinto (NP) conducted semi-structured interviews (n = 85) of health system stakeholders across PC and the PCNs (n = 25), and AHS-primary care (n = 12). These key informant stakeholders were identified using a snowball sampling method in which we leveraged our team's existing relationships and research partnerships in Alberta's PC environment (Blaak et al. 2021; Leslie et al. 2020a, 2020b). These relationships span system leaders to front-line providers, and we purposively sought out differences of experience and opinion across health zones and PCNs. An interview guide was developed by ML and iterated in the field over the course of the research. All the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed for analysis. The digital recordings and transcripts are stored on the University of Calgary's secured servers and will – following standard ethics review board processes – be destroyed as the research project finishes or at the end of 5 years, whichever comes first. Only ML, RF and NP have access to the recordings or raw transcripts. All other co-authors have only dealt with fully anonymized material. Sampling for this analysis of PC integration was purposive and guided by authorial discussions of relevance based on notes taken during interviews. From these discussions, we selected the subset of interviews (n = 37) focused on PC stakeholders' experiences of the novel billing codes and PPE distribution channels that touched on PC integration.

Supported by MAXQDA 2020 software (https://www.maxqda.com/), RF and NP used an inductive coding approach to render an interpretive description of the three elements of PC integration shock-tested by the COVID-19 pandemic. ML, RF and NP analyzed the data iteratively, expanding, collapsing and merging themes to arrive at the final analysis. We present passages from the verbatim transcripts to support this analysis, attributing the responses to participant numbers 01 to 82.

An interpretive description approach allows for insights not just into areas of commonality but also areas of disagreement among participants, with an eye on providing pragmatic suggestions to improve policies and outcomes (Mejdahl et al. 2018; Thorne et al. 1997, 2016; Yan et al. 2016; Young et al. 2012). We conducted iterative participant checks with stakeholders on the emerging interpretations presented here. This research obtained ethical approval from the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB20-0371). All participants provided written and verbal consent to participate.

Results

Virtual care billing codes

With finance as a foundational element of the province's pre-pandemic PC integration model, the introduction and iteration of virtual care billing codes (VCBC) to support PC operations represented a significant shift. Following Alberta's first reported COVID-19 case on March 5, 2020, PC physicians experienced a massively destabilizing decrease in patient visits and thus billing volume. A family doctor stated:

I would say from the middle of March to the end of May our revenue dropped by about 70%. Seven-zero percent! And I would say [that in] this month, June, we'll probably pick up [but] [our volume of visits] will have dropped [by just] 50% [compared to the year before] … It's been devastating. (Participant 45)

To provide financial stability as well as continuity of care to patients, supports in the form of VCBC were introduced. The codes first appeared at a time of considerable friction (Braid 2020; Molnar 2020a) between the province's PC physicians and the MoH over the financial viability of fee-for-service family medicine. As a co-initiative of the MoH and the Alberta Medical Association, the codes were initially implemented with no modifications from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, meaning that they permitted care exclusively for pandemic disease-related complaints and remunerated at rates that were a decade old (Molnar 2020b). As a PC physician described it, these codes were “paying community doc[tor]s 2009 rates for 2020 work with 2020 overhead” (Participant 31).

Another PC physician stated:

They had to create a new code that actually carried enough of a fee that you could pay your staff [with] and not have to lay everyone off. [There was also a strict limit on the number] of telephone visits per week you could even charge for. Not even a day's work basically. So, they had to create a new code. (Participant 78)

Significant uptake occurred once adaptations were made to remove limits on the use of codes, expanding their scope beyond complaints directly related to COVID-19 symptoms and bringing their value in line with 2020 costs. As one AHS-PHCP staffer described it:

[Before March 2020], the use of virtual visits was less than a percent. Once we hit May [and the codes were in place], we saw [it] in the 30% to 40% range. So that's a clear change in practice that had to occur because of COVID … And it's not like virtual visits is a new thing. It's been being kicked around for quite some time; I'm going to say 10–15 years. It just never got any traction. COVID forced a change in practice. (Participant 74)

With compromised access to care for patients, and the financial precariousness of PC clinics motivating a massive change in practice, one physician cautioned that virtual care was not a complete solution. Virtual visits, they noted, were not a panacea for ensuring access to timely patient-centred care that delivered on the promise of the patient's medical home model:

There's this huge reservoir of in-person visits that have been backlogged out there [since the pandemic started]. [T]he tsunami is arriving. All those people we've been putting off, they have to come in. (Participant 78)

In this way, PC physicians and administrators saw the iterated billing codes – the alterations to the finance element of the province's pre-pandemic integration model – as necessary but not sufficient supports for the integration of PC into the province's pandemic response. Beyond altering finances, our participants identified ensuring PC access to PPE as a further necessity. Without this access, in-person visits that could not be replaced by virtual care delivery were seen as a challenge to mounting an effectively integrated pandemic response.

PPE distribution

To meet this challenge, personnel inside AHS and the MoH made further changes to the finance element of the province's integration model while also adjusting the health authority activity and community activity elements. Specifically, the province initially took on the entire cost – and later a portion – of providing PPE to PC. As part of these financial shifts, health authority activity also changed, with AHS sourcing PPE on the global market for the province's independent PC clinics. The PPE was then distributed through the PCNs, representing a pandemic-induced re-alignment of the model's community activity element.

With PPE supply chains stressed, suppliers worldwide began focusing exclusively on large volume orders from institutional players such as AHS. Thrust briefly into the role of sole purchaser for the province, AHS (Mertz 2020) did not initially include PC in its plans (Lee 2020). By mid-March, AHS had committed to distributing PPE free-of-charge to PC and a range of other community-based healthcare providers, such as compounding pharmacists and midwives (AHS 2020). This decision – resulting from intra- and extra-AHS advocacy work on the part of AHS-PHCP personnel – was taken by the MoH based on a desire to maintain the safety and viability of the broader non-AHS health system. An AHS-Central Procurement and Supply Management (AHS-CPSM) manager noted the following:

If we're not able to provide [PPE] to primary care – where you're actually going to be seeing most of [the patients] – then you're simply not being responsive. Because the [acute care] system is going to end up getting constrained anyway. (Participant 76)

However, this arrangement would only last until the start of July 2020. Initially provided at no cost to community-based providers, the MoH reversed its position, deciding in late May to pivot to a model in which PC physicians and clinics – described in the policy as “independent businesses” (Government of Alberta 2020b) – would need to source their own PPE from manufacturers and pay market prices. Shortly after the introduction of this policy, AHS took on a supplier's role, providing PPE not free of charge but at its institutional cost to community-based PC and specialist physicians as well as non-AHS clinics (AHS 2020). In this way, the elements of finance and health authority activity shifted to meet the PPE access challenges encountered by PC clinics, drawing PC closer to the central system.

While acting as the sole provincial supplier of PPE, AHS-CPSM's approach was to leverage the 41 PCNs as distribution hubs to reach more than 1,180 PC clinics and 4,000 PC physicians across the province. In this way, an efficiency-driven distribution model to support operations also shifted the health authority activity and community activity elements of the pre-pandemic integration model. Inside health authority, AHS-CPSM, AHS-PHCP and AHS-ZonePC worked together to include the PCNs in the co-development of the ordering process, the list of items to be made available to PC and the distribution logistics. It was, as one PCN executive director noted, a major step forward from previous integration efforts under pandemic conditions:

AHS’ ability to include the PCNs and consider the unique needs of primary care [has grown by] leaps and bounds … I remember when SARS happened, and that was just such a messy thing to try to figure out how to manage, and there is just no comparison to the organization this time. (Participant 02)

As much as the process to leverage the PCNs was seen as an integration success, the PCNs' experience of becoming distribution hubs was mixed. As Participant 41 stated:

[Some PCN executive directors were] happy to play the role. It's been manageable for us. Primary care clinics are extremely grateful and I think that they're well prepared.

A PCN staffer who had been involved in setting up community-based COVID-19 testing centres elaborated on the relative ease of distributing PPE:

A lot of us [in the PCN] kind of banded together and distributed PPE when needed. And it's not a hard thing to do compared to what we've done." (Participant 56)

Some PCN executive directors, however, were less keen on this warehouse role and the gatekeeper work it required with not only their own PC physician members but also with other community healthcare providers. Indeed, inside the AHS-PHCP, changes to and inconsistencies in central AHS policy saw staff experience the PPE program as “a bit of a disaster” (Participant 74). The problematic changes and inconsistencies here included moments where the AHS-CPSM denied PC orders for PPE that they felt were inappropriate. As an AHS-CPSM manager described it:

[When PC clinics or PCNs made large orders, we would] actually go back to them and say, “Hey, I don't really think you need 10,000 of this. We can give you 1,000 today, and maybe you place another order in two weeks?” (Participant 76)

For most PCN executive directors, this sort of active gatekeeping of the PPE supply was not something in which they needed to engage. One director described it:

I'm not getting crazy [requests], so I don't get a sense of any kind of hoarding going on. (Participant 30)

Whether viewed as a success or as a challenge fraught with extra work, the PPE distribution program illustrates all three of the key elements in Alberta's pre-pandemic PC integration model shifting. Finance – previously limited to fee-for-service billing – shifted to include first no-cost and then at-cost supply of PPE to PC clinics. Health authority activity shifted, with AHS procurement working alongside the PHCP and ZonePC divisions to include PC in the broader system. Community activity shifted as the PCNs were made extensions of the central supply system, not just for PC clinics but for other community-based providers as well.

Discussion

With arguments made that COVID-19 is at the centre of PC expertise (Krist et al. 2020), the disease has had a “seismic effect” on the delivery of care by family physicians (Coombes 2020; Schneider and Shah 2020) who are grappling with the uncertainties of their patients' immediate and long-term issues (Greenhalgh et al. 2020). As this ongoing shock test of PC integration models unfolds around the world (Alsnes et al. 2020; Li and Zhu 2020), governments are seeking even greater involvement of family medicine into the next phase of the pandemic response, with PC deployed to deliver mass vaccination programs (Kanani et al. 2020; Mueller 2020; Weintraub et al. 2020) or positioned as a major resource in overcoming vaccine hesitancy (Griggs 2021). In this context, the shock-test evolution of Alberta's pre-pandemic PC integration model provides policy lessons for the present and the future. The province's moves to support PC through finance reforms ranged from the creation of VCBCs to no- or low-cost PPE distribution for PC. We discuss the policy lessons of these in turn below.

In the case of VCBC, these moves were similar to others made across Canada (BC Family Doctors 2020; CIHI 2021; DoctorCare 2021). According to a national survey of PC physicians, the percentage of in-person appointments dropped from 60% pre-pandemic to a mere 10% during the early months of the pandemic (The College of Family Physicians of Canada and Patient's Medical Home 2021). Conversely, virtual care increased from 23% of appointments pre-pandemic to 50% with the rollout of VCBCs (The College of Family Physicians of Canada and Patient's Medical Home 2021). Without the codes in place, this shift in care delivery for fee-for-service PC physicians resulted in devastating income loss, staff layoffs and the very real threat of clinic closures and bankruptcy that would permanently threaten patients' access to care (Boothby 2020; Glauser 2020; Huston et al. 2020). Indeed, this was a trend observed not only in Canada but in other high-income countries as well (Huston et al. 2020; Landon and Landon 2021; PCC 2020; Rubin 2020; Wright et al. 2020). The provision of support, in the form of appropriate and well-adapted billing codes to PC physicians then, is a necessary condition for protecting patients and the viability of fee-for-service PC clinics. As Alberta's experience shows, policy planning here likely needs to include rapid mechanisms for updating existing billing codes and adapting to novel conditions. With legacy policies written to respond to different circumstances and referencing out-of-date financial conditions, rapid and successful pivoting requires flexibility and channels for feedback. Despite ongoing political friction, Alberta's stakeholders were able to exhibit the former and activate the latter, ultimately creating VCBCs that supported patients and clinicians while improving PC integration into the pandemic response. Relationships that cross the boundaries between central and community-based organizations were important in achieving this resilient, adaptive response.

That response appears to be the fruition of a long-anticipated change in PC practice toward virtual care (CMA 2019; CMA et al. 2020; Kichloo et al. 2020). This was tipped off by the pandemic not just in Alberta, but across Canada (Glazier et al. 2021). As this “new normal” takes hold, however, early evidence from our own work and in other jurisdictions (Abelson 2021) suggests that attention to how VCBCs shape the available quantity and quality of PC will be important. Our ongoing research suggests the possibility that over the course of the switch to virtual care, access to care may have decreased and possibly rebounded for some populations as physicians avoided in-person practice. Similarly, the switch to virtual interactions between patient and physician may have removed key diagnostic opportunities delaying treatment. Subject to further research, the presumptive lesson here is that optimal integration hinges on close attention to access and quality outcomes as novel financing is introduced.

The second shock-test adaptation of the finance element in Alberta's PC integration model saw the province move to provide no or low-cost PPE to PC specifically and community-based clinics generally. Our data suggest that three key policy lessons can be derived from this adaptation: 1) policy attention aimed at anticipating shocks to key PC supply markets will likely support more effective integration; 2) successful finance reform will likely require concurrent adjustments to the health authority and community activity elements of any PC integration model; and 3) PPE, similar to VCBCs, requires policy capacity – forums, working relationships and mutual trust – if responses are to be rapid, appropriate and nimble.

In the first case, Alberta's experience highlights the importance of policy attention in protecting PC-integrated systems from pandemic-induced supply shocks. Future work in this policy space will undoubtedly examine a range of market-based or supply chain-focused solutions to ensuring PC remains a viable and fully integrated part of pandemic responses.

In the second case, our data suggest that meso-level organizations such as the PCNs – that is, organizations that exist in the governance and action space between independent PC physicians and a single health authority (Leslie et al. 2020b) – are important resources requiring engagement not just as extensions of the central system but rather as independent and functional entities in their own right. In this sense, improving PC integration requires both financial reform and attention to the activities of units inside the health authority, which may have had little previous connection to PC. Similarly, our data suggest that long-term coordinated activity with organizations in the community will help ensure responses are extensions of existing relationships, rather than induced by pandemic shocks.

Finally, even with rapid attention to producing VCBCs that are well-adapted to emerging conditions, without adequate supplies and distribution of PPE, access to PC is likely to falter at just the time the system requires it the most. In this way, co-ordinated attention to both VCBCs and PPE will be important to ensuring pandemic-shocked PC remains accessible.

Conclusion

Responding resiliently to the COVID-19 “shock test,” Alberta has successfully adjusted all three elements of its PC integration model. Changes in the province's finance elements – VCBC and no- or low-cost PPE supply – were accompanied by and relied on adjustments to health authority and community activity. Indeed, these adjustments to the non-finance elements addressed challenges that went beyond merely providing more or different money. The keys here were the flexibility to pivot and create relationships that could overcome political friction and allowed stakeholders from inside and outside the central system to understand and respond to a bigger, integrated picture. As Alberta and other jurisdictions with similar models move to anticipate shocks to the supply of PPE, policy planning attention can helpfully be focused on building the mechanisms and relationships that will improve PC integration under both pandemic and more normal operating conditions. While the specifics of Alberta's experience – its legacy organizations, relationships and policy structures – are unlikely to be replicated in other provinces or territories, there are still useful high-level lessons to be drawn. Attention paid to building mechanisms that promote mutual understanding, trust and communication between provincial and territorial health authorities and PC will be central to rapidly updating VCBCs, tracking the quality effects of those codes and effectively backstopping PPE supply markets and supply chains.

Contributor Information

Myles Leslie, Director of Research, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary; Associate Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

Raad Fadaak, Research Associate, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

Nicole Pinto, Research Associate, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

Jan Davies, Professor of Anesthesia, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary; Anesthesiologist, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, AB.

Lee Green, Professor and Chair, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Judy Seidel, Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary; Scientific Director, Primary Healthcare Integration Network, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, AB.

John Conly, Professor, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Infection Prevention and Control, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, AB.

Pierre-Gerlier Forest, Director, School of Public Policy, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and Canadian Institutes of Health Research under the COVID-19 Rapid Response operating grant program dated February 18, 2020.

References

- Abelson R. 2021, March 17. Advanced Cancers Are Emerging, Doctors Warn, Citing Pandemic Drop in Screenings. The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/17/health/cancer-screenings-decline-breast-colon.html>.

- Alberta Health Services (AHS). n.d. Primary Care Networks (PCNs). Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/Page15625.aspx>.

- Alberta Health Services (AHS). 2019. 2018-2019 Report to the Community: AHS Map and Zone Overview. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/publications/ahs-ar-2019/zones.html>.

- Alberta Health Services (AHS). 2020, November 12. PPE Distribution to Community Specialists and Primary Care Physicians Who Are Not a Member of a Primary Care Network. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-ppe-distribution-non-pcn.pdf>.

- Alberta Medical Association Primary Care Alliance Board. 2013, December. PCN Evolution: Vision and Framework: Report to the Minister of Health. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <http://pcnevolution.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/PCNe%20Overview/PCN%20Evolution%20Vision%20and%20Framework.lrg.pdf>.

- Alsnes I.V., Munkvik M., Flanders W.D., Øyane N.. 2020. How Well Did Norwegian General Practice Prepare to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic? Family Medicine and Community Health 8(4): e000512. doi:10.1136/fmch-2020-000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage G.D., Suter E., Oelke N.D., Adair C.E.. 2009. Health Systems Integration: State of the Evidence. International Journal of Integrated Care 9(2). doi:10.5334/ijic.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auditor General of Alberta. 2017, October. Alberta Health–Primary Care Networks. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.oag.ab.ca/reports/health-primary-care-networks-oct-2017/>.

- BC Family Doctors. 2020, June 17. New Telehealth Fee Codes. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://bcfamilydocs.ca/billing-for-virtual-care/>.

- Bichel A., Bacchus M., Meddings J., Conly J.. 2011. Academic Alternate Relationship Plans for Internal Medicine: A Lever for Health Care Transformation. Open Medicine 5(1): e28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaak J., Fadaak R., Davies J., Pinto N., Conly J., Leslie M.. 2021. Virtual Tabletop Simulations for Primary Care Pandemic Preparedness and Response. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning 7: 487–93. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby L. 2020, March 20. COVID-19 Could Bankrupt Clinics Because of Low Fees for Virtual Visits, Edmonton Doctors' Group Says. Edmonton Journal. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/covid-19-edmonton-doctors-group-says-virtual-visits-could-close-clinics-because-of-low-fees>.

- Braid D. 2020, February 20. Braid: UCP Cancels Doctor Pay Contract, Imposes Radical Change. Calgary Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://calgaryherald.com/opinion/columnists/braid-ucp-cancels-doctor-pay-contract-imposes-radical-change>.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2021, September 9. Physician Billing Codes in Response to COVID-19. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.cihi.ca/en/physician-billing-codes-in-response-to-covid-19>.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). 2020. Policy Implementation and Communication Lessons from Alberta's Acute and Primary Care Environments during the COVID-19 Response. Government of Canada. Retrieved October 17, 2021. <https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/decisions/p/project_details.html?applId=422611&lang=en>. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA). 2019, August. CMA Health Summit: Virtual Care in Canada: Discussion Paper. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/News/Virtual_Care_discussionpaper_v2EN.pdf>.

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA); The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC); and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2020, February. Virtual Care: Recommendations for Scaling Up Virtual Medical Services: Report of the Virtual Care Task Force. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/virtual-care/ReportoftheVirtualCareTaskForce.pdf>.

- Chakraborty S., Vyse A., Coakley A.. 2020, August 28. Engaging Primary Care in the Community Management of COVID-19: Global Lessons from a Small Town in Alberta, Canada [Blog post]. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved November 9, 2021. <https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200826.583052/full/>.

- The College of Family Physicians of Canada and Patient's Medical Home. 2021, February. Virtual Care in the Patient's Medical Home. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://patientsmedicalhome.ca/files/uploads/PMH_Virtual-Care-Supplement_ENG_FINAL_REV.pdf>.

- Coombes R. 2020. Covid-19: This Time It's Personal for GPs. BMJ 371: m3898. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3898. [Google Scholar]

- DoctorCare. 2021. A Comprehensive Guide to OHIP Billing Codes for Virtual Care and COVID-19. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.doctorcare.ca/ohip-schedule-of-benefits-for-telemedicine-and-virtual-care/>.

- Espinosa-González A.B., Delaney B.C., Marti J., Darzi A.. 2020. The Role of the State in Financing and Regulating Primary Care in Europe: A Taxonomy. Health Policy 125(2): 168–76. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Kruk M.E.. 2019. Forty Years after Alma-Ata: At the Intersection of Primary Care and Population Health. The Milbank Quarterly 97(2): 383–86. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser W. 2020, May 23. Pandemic Amplifies Calls for Alternative Payment Models. CMAJ News. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://cmajnews.com/2020/05/23/covid-finances-1095874/>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Glazier R.H., Green M.E., Wu F.C., Frymire E., Kopp A., Kiran T.. 2021. Shifts in Office and Virtual Primary Care during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 193(6): E200–10. doi:10.1503/cmaj.202303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta. n.d. Blended Capitation Clinical Alternative Relationship Plan (ARP) Model. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.alberta.ca/blended-capitation-clinical-alternative-relationship-plan-model.aspx>.

- Government of Alberta. 2020a. Fiscal Plan: A Plan for Jobs and the Economy 2020–23. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/05bd4008-c8e3-4c84-949e-cc18170bc7f7/resource/79caa22e-e417-44bd-8cac-64d7bb045509/download/budget-2020-fiscal-plan-2020-23.pdf>.

- Government of Alberta. 2020b. PPE Cost Recovery. My Alberta eSERVICES. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://eservices.alberta.ca/ppe-cost-recovery.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Québec. n.d. Family Medicine Group (FMG), University Family Medicine Group (U-FMG) and Super Clinic. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-system-and-services/service-organization/family-medicine-group-fmg-u-fmg-and-super-clinic/#c698>.

- Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L.. 2020. Management of Post-Acute COVID-19 in Primary Care. BMJ 370: m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs J. 2021, March 5. Leveraging Trust in Primary Care to Promote Behavior Change during COVID-19 [Blog post]. Milbank Memorial Fund. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.milbank.org/2021/03/leveraging-trust-in-primary-care-to-promote-behavior-change-during-covid-19/>. [Google Scholar]

- Hanefeld J., Mayhew S., Legido-Quigley H., Martineau F., Karanikolos M., Blanchet K. et al. 2018. Towards an Understanding of Resilience: Responding to Health Systems Shocks. Health Policy Plan 33(3): 355–67. doi:10.1093/heapol/czx183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality Council of Alberta (HQCA). 2019, October. A Case Study Evaluation: Crowfoot Village Family Practice and the Taber Clinic. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://hqca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/HQCA-Crowfoot_Taber-Case-Study-Evaluation-2019.pdf>.

- Huston P., Campbell J., Russell G., Goodyear-Smith F., Phillips R., van Weel C., Hogg W.. 2020. COVID-19 and Primary Care in Six Countries. BJGP Open 4(4). doi:10.3399/bjgpopen20X101128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanani N., Lawson E., Waller E.. 2020, November 9. Urgent Preparing for General Practice to Contribute to a Potential COVID-19 Vaccination Programme. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0856_COVID-19-vaccineletter_9-Novrevb.pdf>.

- Kichloo A., Albosta M., Dettloff K., Wani F., El-Amir Z., Singh J. et al. 2020. Telemedicine, The Current COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future: A Narrative Review and Perspectives Moving Forward in the USA. Family Medicine and Community Health 8(3): e000530. doi:10.1136/fmch-2020-000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krist A., DeVoe J., Cheng A., Ehrlich T., Jones S.. 2020. Redesigning Primary Care to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Midst of the Pandemic. Annals of Family Medicine 18(4): 349–54. doi:10.1370/afm.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge M., Gaudreault M.. 2019. Promoting Access to Family Medicine in Québec, Canada: Analysis of Bill 20, Enacted in November 2015. Health Policy 123(10): 901–905. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon B., Landon S.. 2021. Primary Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Improving Access to High-Quality Primary Care, Accelerating Transitions to Alternative Forms of Care Delivery, and Addressing Health Disparities The Harvard Medical School Center for Primary Care, CareQuest Institute for Oral Health and The Milbank Memorial Fund. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Book_Primary_Care_During_COVID_ebook_4-27-21.pdf>.

- Lange T., Carpenter T., Zwicker J.. 2020. Primary Care Physician Compensation Reform: A Path for Implementation. School of Public Policy Publications 13(4): 69472. doi:10.11575/sppp.v13i0.69472. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. 2020, May 28. Alberta's New PPE Distribution Plan Unfair, Doctors Tell Province. CBC News. Retrieved October 25, 2021. <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/ppe-alberta-doctors-supply-cost-1.5588488>.

- Legido-Quigley H., Asgari N., Teo Y., Leung G.M., Oshitani H., Fukuda K. et al. 2020. Are High-Performing Health Systems Resilient against the COVID-19 Epidemic? The Lancet 395(10227): 848–50. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie M., Fadaak R., Davies J., Blaak J., Forest P.G., Green L. et al. 2020a. Integrating the Social Sciences into the COVID-19 Response in Alberta, Canada. BMJ Global Health 5(7): e002672. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie M., Khayatzadeh-Mahani A., Birdsell J., Forest P.G., Henderson R., Gray R.P. et al. 2020b. An Implementation History of Primary Health Care Transformation: Alberta's Primary Care Networks and the People, Time and Culture of Change. BMC Family Practice 21: 258. doi:10.1186/s12875-020-01330-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.K.T., Zhu S.. 2020. Contributions and Challenges of General Practitioners in China Fighting against the Novel Coronavirus Crisis. Family Medicine and Community Health 8(2): e000361. doi:10.1136/fmch-2020-000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchildon G., Di Matteo L. (Eds.). 2015. Bending the Cost Curve in Health Care: Canada's Provinces in International Perspective. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchildon G., Hutchinson B.. 2016. Primary Care in Ontario, Canada: New Proposals after 15 Years of Reform. Health Policy 120(7): 732–38. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejdahl C.T., Valen Schougaard L.M., Hjollund N.H., Riiskjær E., Lomborg K.. 2018. Exploring Organisational Mechanisms in PRO-Based Follow-up in Routine Outpatient Care – An Interpretive Description of the Clinician Perspective. BMC Health Service Research 18(1): 546. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3352-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz E. 2020, April 14. Coronavirus: Alberta Government Asks Non-AHS Staff Needing PPE to Request via Email. Global News. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://globalnews.ca/news/6818804/alberta-non-ahs-ppe-coronavirus-protective-masks/>.

- Molnar C. 2020a, April 17. Embattled. Alberta Medical Association. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.albertadoctors.org/services/media-publications/presidents-letter/pl-archive/Embattled>. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar C. 2020b, July 20. We Are Under Attack. Alberta Medical Association. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.albertadoctors.org/services/media-publications/presidents-letter/pl-archive/we-are-under-attack>. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B. 2020, December 31. Some Doctors in Britain Plan to Defy Instructions to Delay Vaccine Booster Shots. The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/31/world/uk-britain-covid-coronavirus.html>.

- Primary Care Collaborative (PCC). 2020. Quick COVID-19 Primary Care Survey: Series 18 Fielded August 7–10, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d7ff8184cf0e01e4566cb02/t/5f4073436c65f16b60e29d6c/1598059336727/C19+Series+18+National+Executive+Summary.pdf>.

- Rowan M.S., Hogg W., Huston P.. 2007. Integrating Public Health and Primary Care. Healthcare Policy 3(1): e160–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. 2020. COVID-19's Crushing Effects on Medical Practices, Some of Which Might Not Survive. JAMA 324(4): 321–23. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E.C., Shah T.. 2020, May 20. Pandemic Shock Threatens to Undermine Outpatient Care [Blog]. The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/pandemic-shock-threatens-undermine-outpatient-care>. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon R., Damba C., Bryant S.. 2013. Measuring Quality at a System Level: An Impossible Task? The Toronto Central LHIN Experience. Healthcare Quarterly 16(4): 36–42. doi:10.12927/hcq.2014.23654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenbensel T., Burau V.. 2017. Contrasting Approaches to Primary Care Performance Governance in Denmark and New Zealand. Healthcare Policy 121(8): 853–61. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S.R., MacDonald-Emes J.. 1997. Interpretive Description: A Noncategorical Qualitative Alternative for Developing Nursing Knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health 20(2): 169–77. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199704)20:2<169::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Stephens J., Traunt T.. 2016. Building Qualitative Study Design Using Nursing's Disciplinary Epistemology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(2): 451–60. doi:10.1111/jan.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn P.P., Schepman S.M., Opheija W., Brujinzeels M.A.. 2013. Understanding Integrated Care: A Comprehensive Conceptual Framework Based on the Integrative Functions of Primary Care. International Journal of Integrated Care 13: e010. doi:10.5334/ijic.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Gusmano M., Cao Q.. 2011. An Evaluation of the Policy on Community Health Organizations in China: Will the Priority of New Healthcare Reform in China be a Success? Healthcare Policy 99(1): 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub R., Koller C.F., Bitton A.. 2020, December 1. Why Primary Care Can Make COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution More Successful [Blog post]. Milbank Memorial Fund. Retrieved October 18, 2021. <https://www.milbank.org/2020/12/why-primary-care-can-make-covid-19-vaccine-distribution-more-successful/>. [Google Scholar]

- Wright M., Versteeg R., Hall J.. 2020. General Practice's Early Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Australian Healthcare Review 44(5): 733–36. doi:10.1071/AH20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Rose S., Rothberg M.B., Mercer M.B., Goodman K., Misra-Hebert A.D.. 2016. Physician, Scribe, and Patient Perspectives on Clinical Scribes in Primary Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31(9): 990–95. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J., Donahue M., Farquhar M., Simpson C., Rocker G.. 2012. Using Opioids to Treat Dyspnea in Advanced COPD. Canadian Family Physician 58: e401–07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]