Abstract

Tobacco is notably genotoxic and associated with head and neck carcinogenesis. Cigarette carcinogens have the capacity to alter early response gene expression in tobacco-related malignancies via genes such as NFκB. A number of early response gene activation events are also facilitated by fos/jun AP-1 associated pathways. In the present study, we hypothesize tobacco products may induce microenvironment alterations, promoting angiogenesis and providing a permissive environment for head and neck cancer progression. In an in vitro analysis, we employed immortalized oral keratinocyte (HOK-16B) and laryngeal squamous carcinoma (UM-SCC-11A) cells to investigate IL-8 and VEGF induction by cigarette smoke condensate (CSC). IL-8 and VEGF expression is based on interactions between NFκB, AP-1, and NF-IL6. We identified at least 1.5-fold dose-dependent induction of AP-1, VEGF, and IL-8 promoter/reporter gene activity after 24 hour exposure to CSC. Next, we stably transfected UM-SCC-11A cells with A-Fos, a dominant negative AP-1 protein. Treatment with CSC of the A-Fos cell lines compared to empty vector controls significantly downregulated AP-1, VEGF and IL-8 promoter/reporter gene expression. We also performed ELISAs and discovered significant upregulation of IL-8 and VEGF secretion by UMSCC 11A after treatment with PMA, TNFα, and CSC, which was downregulated by the A-Fos dominant negative protein. We conclude tobacco carcinogens upregulate AP-1 activity and AP-1 dependent IL-8 and VEGF gene expression in head and neck cancer. This upregulation may promote an angiogenic phenotype favoring invasion in both premalignant and squamous cancer cells of the head and neck.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, Activator Protein 1, cigarette smoke condensate, tobacco carcinogens, VEGF, IL-8

Introduction

Each year over 40,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with head and neck cancer and tobacco and/or alcohol use is identified in over 75% of cases [1–5]. The cure rates for head and neck cancer have not improved over several decades and voids exist in the understanding of signaling events during tobacco-induced carcinogenesis and progression [1,6]. In head and neck cancer, constitutive upregulation of early response genes activator protein 1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa b (NFκB) controls a number of cellular processes associated with malignant progression from a precancerous to metastatic phenotype [7–15]. For example, both pro-angiogenic and pro-inflammatory cytokines are significantly upregulated in murine squamous carcinogenesis models of head and neck cancer during tumor growth and metastatic spread [16]. Several studies also indicate pro-angiogenic cytokine expression in head and neck cancer cell lines is NFκB dependent when AP-1 is also constitutively activated. In these studies, dominant negative and other gene knockdown approaches can significantly decrease interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 expression when NFκB is targeted and decrease vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression when AP-1 is targeted [14,17].

IL-8 and VEGF are implicated in tumor progression via their contributions to angiogenesis, a process which allows autonomous growth of tumors once they achieve a size of approximately 3mm [18–23]. It is well established that IL-8 is a gene controlled by cooperative interactions in the promoter between transcription factors and NFκB, AP-1 and nuclear factor (NF)-IL6 elements, as IL-8 secretion from cells in the microenvironment appears maximized when these transcriptional events are switched on [14,16,24]. VEGF has been primarily identified as a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α and AP-1 dependent gene, and can be maximally stimulated during periods of low oxygen tension in the tumor microenvironment when HIF 1α is activated [25–29]. Both of these cytokines contribute to angiogenesis and are found in the milieu of head and neck cancer specimens as well as in oral cavity fluids of patients afflicted with head and neck carcinomas [30–32].

Tobacco carcinogens are principally genotoxic [33] but tobacco use is also highly associated with inflammatory conditions of the oral cavity and gingiva [34–38]. The pro-inflammatory effects of tobacco carcinogens require further investigation to yield a better understanding of head and neck carcinogenesis. A growing body of evidence indicates approximately 15% of the world’s malignancies are associated with chronic inflammation [39,40]. In head and neck carcinogenesis, chronic inflammation is an accompanying feature of dysplastic lesions and at least 75% of leukoplakia lesions are associated with smoking [41–44].

In the present study, we examined influences of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) on AP-1 dependent activation of IL-8 and VEGF in vitro. We found CSC could significantly stimulate AP-1 activation of both genes, resulting in increased IL-8 and VEGF secretion, and that these processes could be downregulated with introduction of a dominant negative A-Fos gene. These data demonstrate a role for tobacco carcinogen stimulation of pro-angiogenic cytokines, thus promoting an environment suitable for development and metastatic spread of head and neck cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials

To stimulate AP-1, cells were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), a diester of phorbol which activates the signal transduction enzyme protein kinase C, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (Promega, Madison, WI), or cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) (Murty Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, KY) solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The CSC is a standardized extract and is prepared by smoking University of Kentucky's Standard Research Cigarettes on an FTC Smoke Machine. The Total Particulate Matter (TPM) on the filter is calculated by the weight gain of the filter. From the TPM, the amount of DMSO to be used for extraction to prepare a theoretical 4% (40mg/mL) solution is calculated. The condensate is extracted with DMSO by soaking and sonication, then packaged 1 mL/vial in dry vials. Stock CSC, stored at −80°C, was thawed and added to cell growth media using serial dilutions to create treatment media of desired concentrations. Control cells were treated with medium containing an equivalent amount of DMSO. Repeated freezing and thawing of CSC solution was avoided as much as possible.

The AP-1 reporter gene plasmid (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) expresses the firefly luciferase gene under the control of a synthetic promoter containing seven direct repeats of the AP-1 transcription factor binding sequence. The VEGF reporter gene plasmid (a gift from Amit Maity, University of Pennsylvania) contains 1.5kb of the VEGF promoter in the pGL-3Basic vector [45]. The IL-8 reporter gene plasmid (from Dr. Naofumi Mukaida, Cancer Research Institute, Kanazawa University, Japan) contains 133bp of the IL-8 promoter in a firefly luciferase reporter vector [14].

Methods

Cell Culture

The HOK-16B, HPV immortalized human oral keratinocytes, were a kind gift from N.H. Park at UCLA. These cells were grown in KGM-2 Medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract, epidermal growth factor, insulin and hydrocortisone at 37°C in 5% CO2. UM-SCC-9, 11A, 11B and 38 are head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines, received from Thomas Carey, University of Michigan. These cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in 5% CO2. UM-SCC-9 was harvested from a tonsil/base of tongue primary tumor, UM-SCC-11A was harvested from a primary laryngeal cancer biopsy, UM-SCC-11B was derived from the laryngectomy specimen of the same patient after chemotherapy, and UM-SCC-38 was harvested from a tonsil/base of tongue primary tumor. NA and CA 9–22 are oral squamous carcinoma cell lines grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Where indicated, cells were grown in serum free media. The concentration of DMSO, in all cultures, including as a solvent control, was <0.1%. All lines were mycoplasma free by PCR testing. HUVEC cells were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and were grown in Medium 200 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 1µg/mL hydrocortisone, 10ng/mL human epidermal growth factor, 3ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, and 10µg/mL heparin at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Reporter Gene Assay

The cell lines were plated at 40,000 cells/well in 12 well plates and transiently co-transfected via TransIT LT1 (MirusBio, Madison, WI) with either AP-1, VEGF, or IL-8 reporter gene plasmids 24 hours later along with a pCMV Lac-Z reporter containing the CMV promoter and Lac-Z gene in pcDNA3 to adjust for transfection efficiency. After overnight transfection, cells were treated for 24h with DMSO (solvent control), PMA, TNFα, or CSC in serum free media. Cell lysates were analyzed via Tropix Dual Light Reporter Gene Assay (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) on a Tristar dual injection flash luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN). Nine replicates were measured per data point and each experiment was repeated in triplicate.

Stable Transfection of A-Fos

UM-SCC-11A cells were stably transfected with a dominant negative AP-1 plasmid (A-Fos), a gift from Charles Vinson (Laboratory of Metabolism, Center for Cancer Research, NCI/NIH), and selection performed with neomycin. The A-Fos protein has been extensively studied in the past. It contains an acidic amphipathic protein sequence appended onto the N-terminus of the Fos leucine zipper. This acidic extension interacts with the Jun basic region and extends the leucine zipper which prevents a JUN/A-fos heterodimer from interacting with AP-1 consensus sequences [46,47].

HOK-16B cells were co-transfected with A-Fos and pCDNA3.1-hygro and selected with hygromycin, as they are neomycin resistant from HPV transfection. Polyclonal populations were used for experiments.

ELISA

UM-SCC-11A and HOK-16B cells were plated in 25cm2 flasks and treated with DMSO, PMA, TNFα, or increasing CSC concentrations in serum free media. After 24 hours, media was collected and assayed for total IL-8 and VEGF using the DuoSet ELISA Development Kit for each analyte (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were run in triplicate. All experiments were independently repeated 2–3 times.

Angiogenesis microtubule assay

Cryopreserved HUVEC cells were seeded at 2 × 105 viable cells in a 75cm2 tissue culture flask using LSGS-supplemented Medium 200. Culture medium was changed every other day until the culture was approximately 80% confluent. A 24 well tissue culture plate was coated with Geltrex (Invitrogen) and incubated at 37°C, allowing solidification. HUVEC cells were harvested via trypsinization and centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended with non-supplemented Medium 200. Cells were mixed with conditioned media from HOK-16B cells treated with varying concentrations of CSC (supernatants were treated and collected precisely as described in the ELISA methods above) to a concentration of 8×104 cells per 400µL and added to the coated wells. The 24well plate was incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for four hours. To quantitate microtubule formation, capillary tube branch points were counted in two 100× fields per well (two replicate wells per treatment for a total of four replicates).

Western Blot

UM-SCC-11A and HOK-16B cells were plated in 75cm2 flasks and treated the following day with DMSO, PMA or 30ug/mL CSC in serum free media. Nuclear extracts were prepared using the NE-PER nuclear extract kit (Pierce Biotechnologies, Rockford, IL). Protein quantification was performed using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). Ten micrograms of nuclear protein per lane was separated on a 4–12% BisTris NuPage Gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-PSQ 0.2µm PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Detection was performed using the SNAP I.D. (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 0.5% milk in TBS/0.1% Tween-20 then blotted with a primary antibodies to AP-1 family members (AP-1 Family Antibody Screening Kit, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) individually followed by a horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Proteins were visualized with a chemiluminescence assay system (Pierce). Membranes were stripped and re-probed with each of the screening kit members and histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Differences in reporter gene activity, released protein levels, and capillary tube branch point counts were compared by Student T-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows was used for these analyses, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

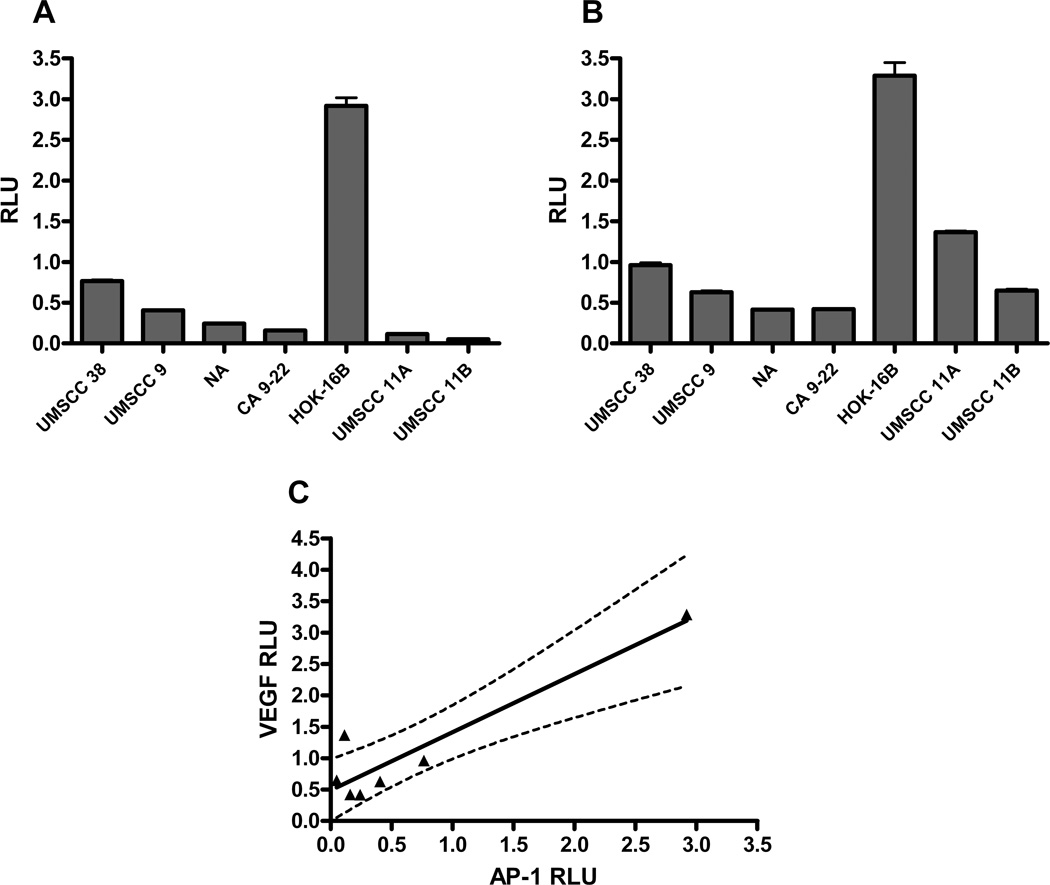

Pro-angiogenic cytokines such as IL-8 and VEGF are downstream from a variety of transcription factors. Specifically, IL-8 has been shown to be under principal control of AP-1, NFκB, and NF-IL6 [48–51]. VEGF is under great influence by low oxygen conditions stimulating the transcription factor HIF 1α, but is also under significant control by AP-1 [52,53]. Presently, we concentrated on the AP-1 associated activities of both genes as contributed to by cigarette smoke condensate. To establish the baseline levels of AP-1 or VEGF activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, we first investigated the degree of activation of AP-1 dependent reporter genes via luciferase assay. Twenty four hours after transfection of seven cell lines with AP-1 luciferase promoter/reporter plasmids, we assayed baseline transcriptional AP-1 activity (Figure 1A). We observed a 51-fold difference in activation between the highest and lowest activity of cell lines tested. Interestingly, the HPV-transfected premalignant oral keratinocytes (HOK-16B cells) had the greatest degree of AP-1 activity compared to the other cell lines. The invasive carcinoma cell lines had a 13-fold difference in baseline AP-1 activation between the highest and lowest cell line activities.

Figure 1. Positive correlation between AP-1 and VEGF promoter activity in head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines.

Head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines and HOK-16B cells were transiently transfected with AP-1 or VEGF promoter/luciferase reporter plasmids. (A) AP-1 or (B) VEGF constitutive promoter activity was measured via luciferase reporter gene assay. (C) Linear regression analysis via GraphPad Prism revealed a positive correlation between constitutive promoter activities (r2=0.8616, P=0.0025). RLU = relative light units.

Next, we repeated the experiment using the VEGF reporter plasmid. We again identified a significant degree of baseline activation of the VEGF reporter gene, which was highest in the HOK-16B premalignant keratinocytes compared to the malignant cells (Figure 1B). As VEGF is downstream of AP-1, we sought to establish the degree of correlation between baseline AP-1 reporter gene activity and VEGF reporter gene activity. We performed linear regression correlation analysis of the baseline activities of both genes. We identified a high level of correlation (r2 = 0.8616, P = 0.0025) between AP-1 and VEGF baseline gene activation in head and neck cancer cell lines, as judged by luciferase reporter gene activity (Figure 1C).

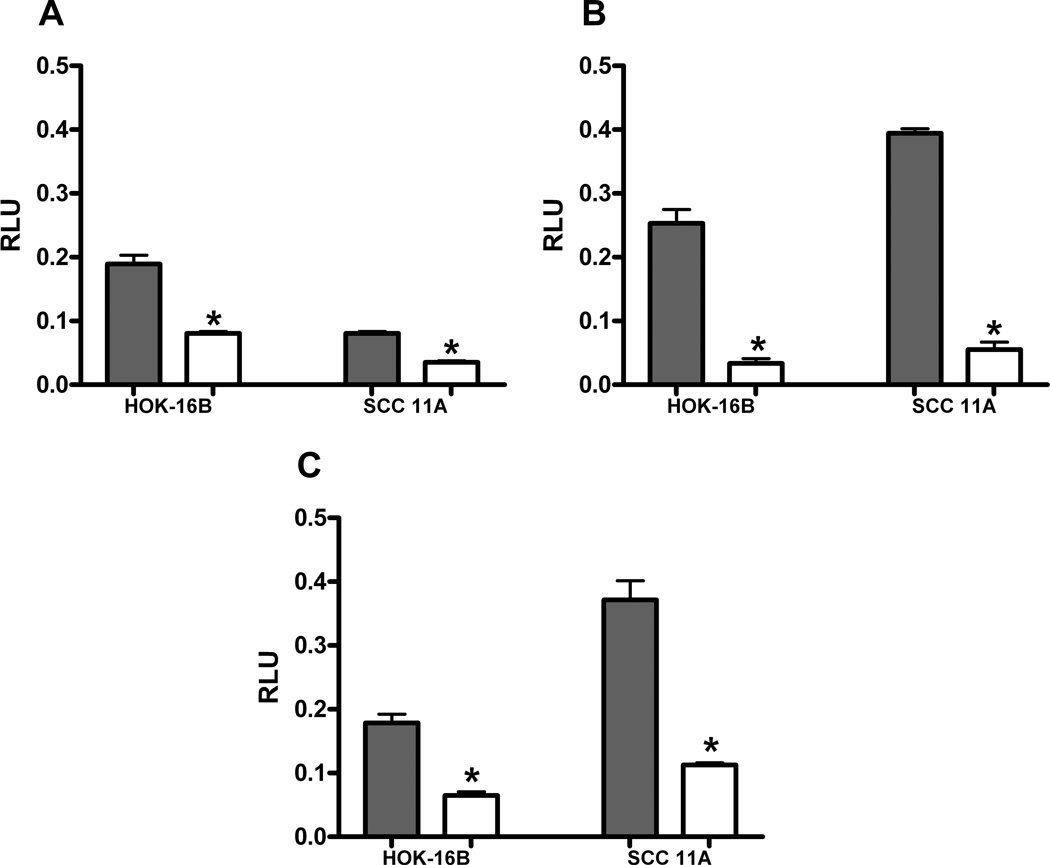

In order to further demonstrate whether pro-angiogenic cytokines are under AP-1 control, we established stably-transfected cell lines utilizing the dominant negative A-Fos construct in both the HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cell lines. Once these cell populations contained either the empty vector control or the dominant negative A-fos, we compared the levels of AP-1, VEGF, and IL-8 promoter activity in each cell line. First, we identified constitutive AP-1 promoter activity was significantly decreased by at least 2.3-fold in both cell lines after insertion of dominant negative A-Fos (Figure 2A) (P ≤ 0.0001). Next, we assayed the level of VEGF or IL-8 activation in empty vector control or A-Fos cell lines. After the insertion of A-Fos, we found the level of constitutive VEGF activation was suppressed by 7.6-fold in HOK-16B cells, and by 7.1-fold in the UM-SCC-11A cell lines (Figure 2B) (P ≤ 0.0001). Similar findings were identified for IL-8 luciferase activation after A-Fos insertion into each cell line (Figure 2C) (P ≤ 0.0001). These findings, taken together, demonstrate both pro-angiogenic cytokines have significant activation which is contributed to by constitutive AP-1 activity in head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines.

Figure 2. Dominant negative AP-1 (A-Fos) decreases AP-1, VEGF and Interleukin-8 promoter activity.

HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells stably expressing empty vector or A-Fos were transiently transfected with AP-1 (A), VEGF (B), or Interleukin-8 (C) promoter/reporter plasmids. The cells were harvested after 24h treatment in solvent and assayed for luciferase activity. Both cell lines demonstrated significant decrease in AP-1, VEGF and IL-8 with addition of A-Fos, shown in white (*= P value of ≤ 0.0001).

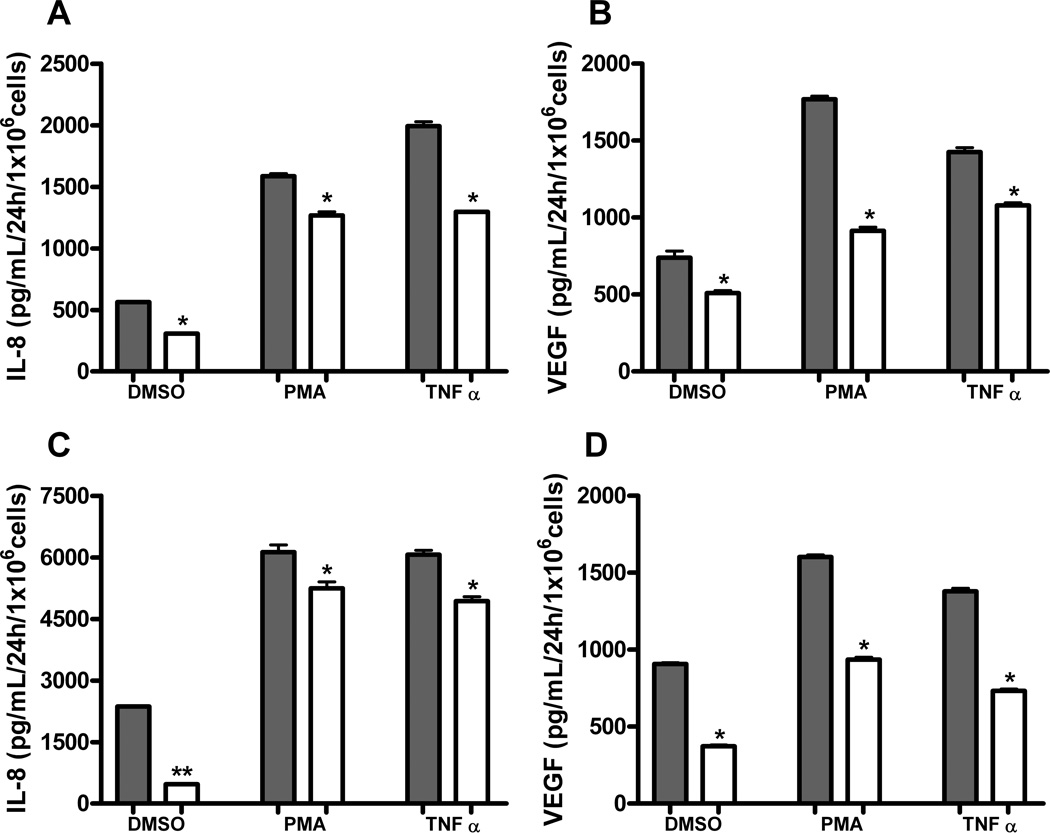

ELISA was utilized to further evaluate the relationship between AP-1 activation and downstream IL-8 and VEGF expression in HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cell lines. Levels of constitutive IL-8 secretion were significantly decreased in each cell line after insertion of dominant negative A-Fos. In addition, treatment of cells with 10nM PMA or 10ng/mL TNFα as positive controls induced high levels of IL-8 secretion which were largely diminished with A-Fos insertion (Figures 3A, 3C) (P ≤ 0.05). Constitutive VEGF secretion was similarly decreased in both cell lines by insertion of A-Fos. PMA and TNFα treatments also caused increased secretion of VEGF in both cell lines, which was significantly decreased in cells stably expressing A-Fos (Figures 3B, 3D) (P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3. A-Fos decreases release of pro-angiogenic cytokines in response to PMA and TNFα.

HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells stably expressing A-Fos or empty vector were treated for 24h with 10nM PMA or 10ng/mL TNFα and assayed for cytokine release via ELISA. (A) IL-8 in HOK-16B, (B) VEGF in HOK-16B, (C) IL-8 in UM-SCC-11A and (D) VEGF in UM-SCC-11A. Both cell lines demonstrated a significant decrease in cytokine release with addition of dominant negative AP-1 (A-Fos), shown in white (*= P value of ≤ 0.05, **= P value of ≤ 0.0001).

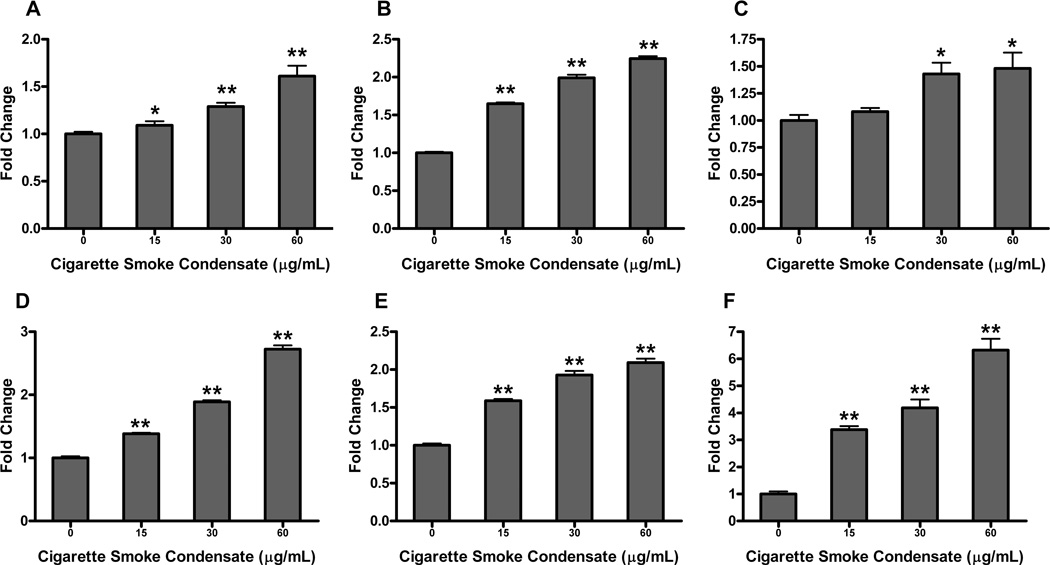

Cigarette smoke condensate has recently been shown to upregulate NFκB activity in transformed oral keratinocytes and squamous cell carcinoma [15]. We hypothesized CSC could also increase AP-1 activity in these cell types. Treatment of the HOK-16B cell line with CSC demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in AP-1 promoter activity, with as much as a 1.6-fold increase in AP-1 after treatment with 60µg/mL CSC (Figure 4A) (P ≤ 0.0001). AP-1 promoter activity in the UM-SCC-11A cell line was also upregulated in a dose-dependent fashion with CSC treatment, demonstrating a peak 2.7-fold increase in activity with 60µg/mL CSC treatment (Figure 4D) (P ≤ 0.0001). We then examined VEGF and IL-8 promoter activities in response to CSC in transformed oral keratinocytes. Similar to AP-1, we demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in these promoter activities after CSC treatment (Figures 4B and 4C) (P ≤ 0.05). In the UM-SCC-11A cell line, VEGF and IL-8 promoter activities were also significantly increased with CSC treatment, again in a dose-dependent fashion (Figures 4E and 4F) (P ≤ 0.0001).

Figure 4. Cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) upregulates AP-1, VEGF, and IL-8 promoter activity in HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells.

HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells were transiently transfected with AP-1, VEGF, or IL-8 promoter/reporter plasmids and underwent 24h treatment with varying concentrations of CSC. Cells were harvested, lysed and luciferase assay performed. Promoter activities are as follows, (A) AP-1, (B) VEGF, and (C) IL-8 in HOK-16B; (D) AP-1, (E) VEGF, and (F) IL-8 in UM-SCC-11A. CSC significantly upregulated AP-1, VEGF, and IL-8 promoter activities in a dose-dependent manner for both cell lines (*= P value of ≤ 0.05 vs. control, **= P value of ≤ 0.0001 vs. control).

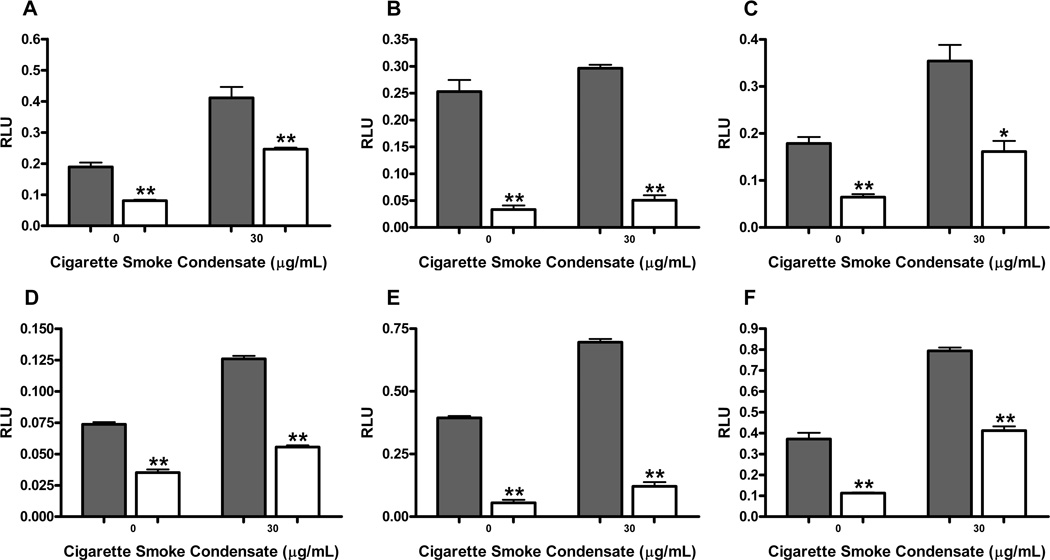

Next, we sought to determine whether the DN A-Fos plasmid could affect AP-1, VEGF or IL-8 promoter activities in response to CSC treatment. We chose to treat HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells with 30µg/mL CSC, based on our previous study [15]. In the presence of A-Fos; AP-1, VEGF and IL-8 promoter activities for HOK-16B were decreased by 1.7-fold, 5.9-fold, and 2.2-fold, respectively (Figures 5A–C) (P ≤ 0.05). The UM-SCC-11A cell line expressing A-Fos showed reduction in AP-1 by 2.3-fold, VEGF by 5.8-fold, and IL-8 by 1.9-fold (Figures 5D–F) (P ≤ 0.0001). Others have demonstrated that dominant negative AP-1 insertion in mouse keratinocytes can coordinately downregulate NFκB activity as well [54,55]. We tested whether A-Fos would act in a similar fashion in the oral cancer cells. However, we found only 0.1–0.2 fold increases in NFκB luciferase activity when this was tested in UM-SCC-11A cells (not shown). This is far less than effects observed with TAM67 dominant negative insertion in murine cells.

Figure 5. A-Fos decreases AP-1, VEGF and IL-8 promoter activity in response to CSC treatment.

HOK-16B and UMSCC 11A cells stably expressing A-Fos or empty vector were transiently transfected with AP-1, VEGF or IL-8 promoter/reporter plasmids. After 24h treatment with 30µg/mL CSC, promoter activity was analyzed via reporter gene assay. Promoter activities are as follows, (A) AP-1, (B) VEGF, and (C) IL-8 in HOK-16B; (D) AP-1, (E) VEGF, and (F) IL-8 in UM-SCC-11A. AP-1, VEGF, and IL-8 promoter activity was significantly decreased in both cell lines with addition of A-Fos, shown in white (*= P value of ≤ 0.05 vs. control, **= P value of ≤ 0.0001 vs. control).

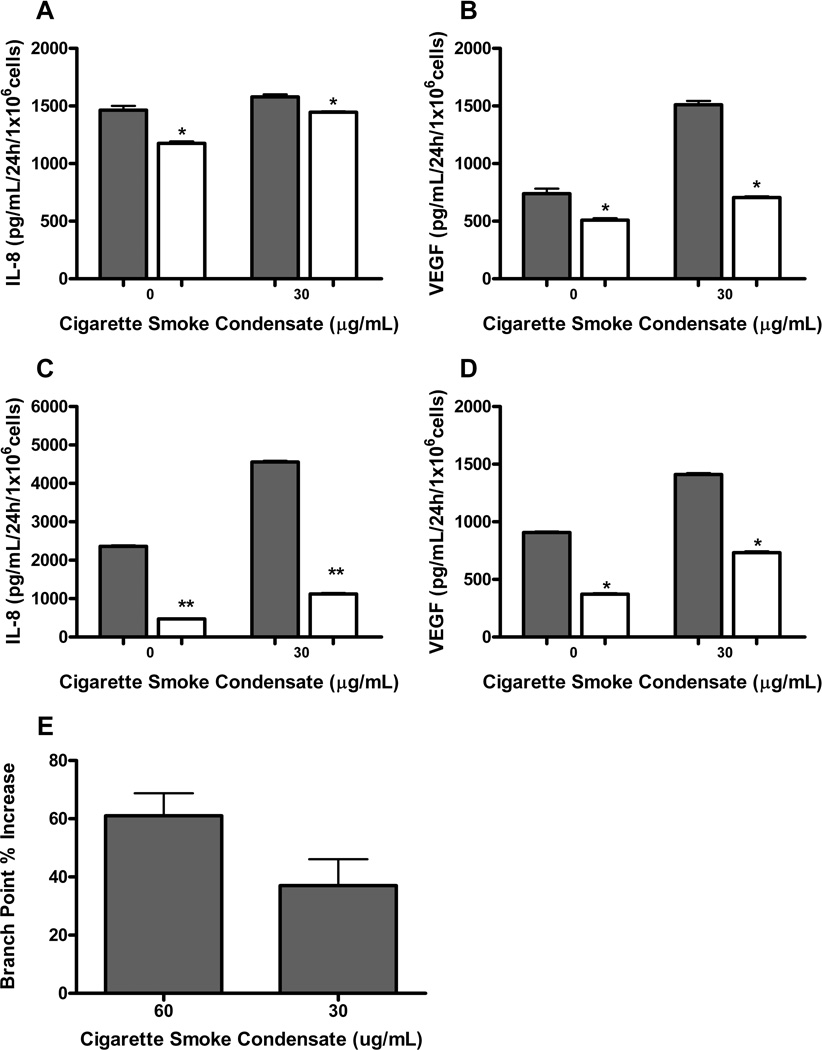

We then wanted to further delineate the relationship between CSC-mediated secretion of pro-angiogenic cytokines and their dependence upon AP-1 activity. HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells stably expressing A-Fos or empty vector were treated with 30µg/mL CSC for 24 hours. Cultured cell supernatants were collected and assayed for cytokine release via ELISA. In both HPV-transformed premalignant keratinocytes and invasive squamous carcinoma, upregulation of IL-8 and VEGF secretion via CSC treatment was largely decreased with insertion of A-Fos (Figure 6A–D) (P ≤ 0.05). Next, we wanted to investigate whether supernatants from CSC treated A-Fos cells would functionally downregulate angiogenesis. We utilized conditioned media from either A-fos or empty vector transfected HOK-16B cells treated with CSC for 24 hours and examined endothelial tube formation, as a standard measure of angiogenesis. We observed that supernatents from CSC treated EV HOK-16 B cells could stimulate endothelial tube formation by up to 61% compared to CSC treated A-Fos cells (P = 0.0003 for 60ug/mL CSC and P = 0.0019 for 30ug/mL CSC) (Figure 6E). These data, taken together demonstrate that CSC has the capacity to stimulate both proangiogenic cytokine secretion and angiogenesis in premalignant oral cavity (HOK-16B EV cells) when AP-1 is intact compared to when the A-fos dominant negative is transfected.

Figure 6. A-Fos decreases release of pro-angiogenic cytokines in response to CSC.

HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells stably expressing A-Fos or empty vector were treated with CSC for 24h and assayed for cytokine release via ELISA. ELISA for (A) IL-8 and (B) VEGF in HOK-16B; (C) IL-8 and (D) VEGF in UM-SCC-11A. Both cell lines demonstrated significant decrease in cytokine release with addition of A-Fos, shown in white (*= P value of ≤ 0.05 vs. control, **= P value of ≤ 0.0001 vs. control). (E) Capillary tube branch point formation of HUVEC in an endothelial tube formation assay is increased by 61% (P = 0.0003) when comparing effect of conditioned media from 60ug/mL CSC treated empty vector control HOK-16B cells to A-Fos HOK-16B cells. An increase of 37% is seen with 30ug/mL CSC in HOK-16B EV/A-Fos (P = 0.0019).

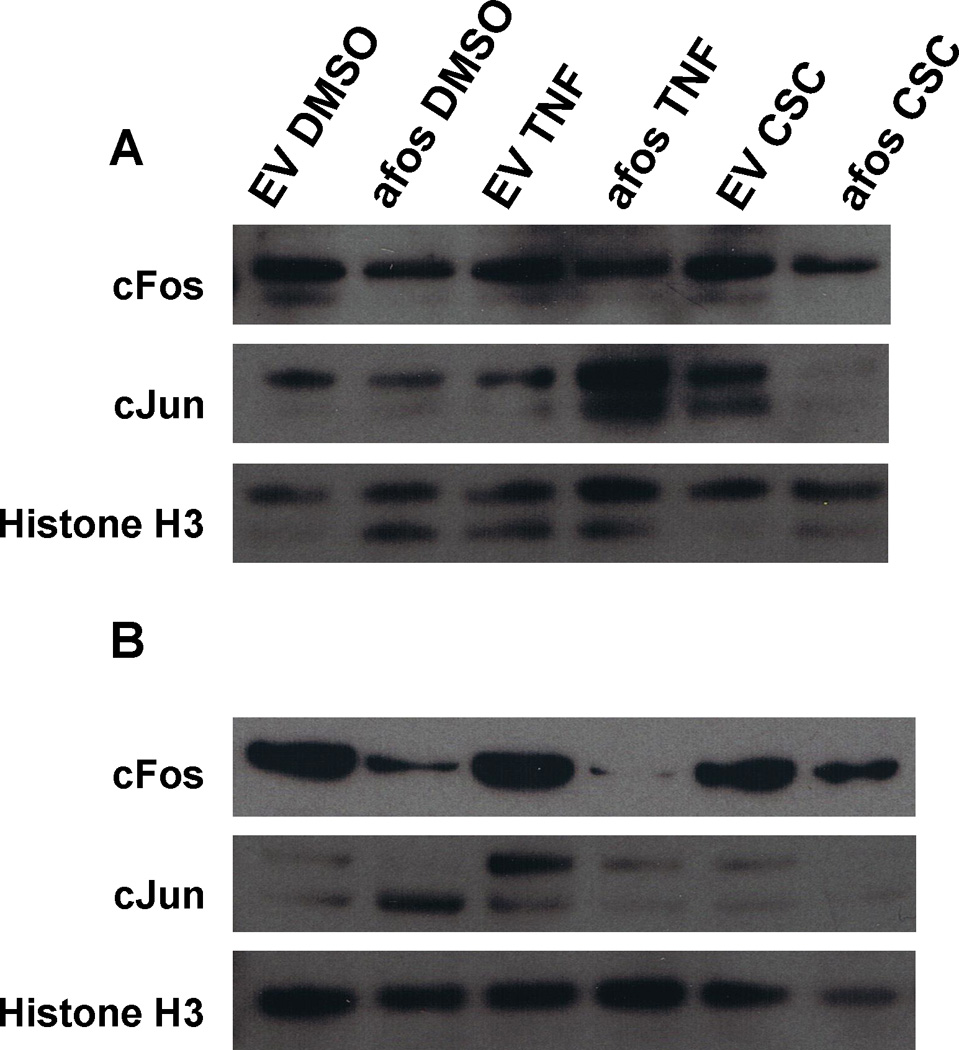

Next, we examined the nuclear levels of two AP-1 family members, cfos and cjun, to determine if expression of the dominant negative A-fos affected expression in an autocrine manner. Cells were treated with DMSO, 10ng/mL TNFα, or 30ug/mL CSC, nuclear extracts isolated and separated via PAGE. Western blot was performed with antibodies to cfos, cjun, and histone H3. In the HOK-16B (Figure 7A), we found cfos expression was visibly decreased with addition of the dominant negative A-fos. The cjun expression decreased when the cells were treated with DMSO or CSC. An increase in expression was seen with TNFα treatment. Also in the HOK-16B, the antibody to Histone H3 non-specifically bound to a slightly smaller protein. UM-SCC-11A (Figure 7B) experienced a visible decrease in cfos and cjun expression with the addition of the dominant negative, A-fos. In the UM-SCC-11A, the particular antibody to cjun we employed also bound non-specifically to a protein marginally smaller than cjun, the lower band shown in the cjun panel in Fig. 7A.

Figure 7. A-Fos decreases nuclear protein levels of cfos and cjun.

HOK-16B and UM-SCC-11A cells stably expressing A-Fos or empty vector were treated with 10ng/mL TNFα or 30µg/mL CSC for 24h. Nuclear proteins were collected and analyzed via western blot. (A) HOK-16B; (B) UM-SCC-11A. Both cell lines demonstrated a decrease in cfos and cjun expression with addition of A-Fos.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of AP-1 in the production of a pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic cellular microenvironment in premalignant oral keratinocytes and HNSCC cell lines. We studied the importance of AP-1 at baseline conditions as well as in the presence of CSC, a known stimulator of cellular carcinogenesis. AP-1 is composed of a family of dimeric basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins which regulate cellular proliferation, transformation and death [56]. A strong connection between AP-1 and chronic inflammation has been established in colon, breast, and prostate cancer [57–59]. Cytokines such as IL-8 and VEGF permit a pro-tumorigenic cellular environment via propagation of inflammation and angiogenesis. Accordingly, we first evaluated the potential association between constitutive AP-1 and VEGF promoter activities in multiple head and neck cancer cell lines. Results demonstrate the level of VEGF activation at baseline is highly correlated with the degree of AP-1 activation in the cell lines tested (Figure 1). These data are consistent with published literature demonstrating VEGF relies on AP-1 as a principal control mechanism in cancer [26–29].

We hypothesized inhibition of AP-1 activity in premalignant keratinocytes and invasive carcinoma cell lines would yield markedly decreased transcriptional and translational activities of VEGF and IL-8, which are implicated in the promotion of cellular inflammation and angiogenesis. We utilized a dominant negative to AP-1 which inhibits Fos-Jun heterodimer binding to DNA in equimolar competition. This dominant negative, termed A-Fos, is more potent than other previously constructed DNs to AP-1 which carried a deletion of the Fos or Jun transactivation domains [46]. Our present investigation is the first to utilize A-Fos to study the importance of AP-1 activity in the context of HNSCC. We established the level of AP-1 activation in head and neck cancer cell lines is associated with the levels of both VEGF and IL-8 activation in HPV-transformed oral keratinocytes and head and neck cancer cell lines, as introduction of A-Fos resulted in a proportional decrease in VEGF and IL-8 promoter activity compared to AP-1 (Figure 2). This suggests both genes are AP-1 dependent to a significant degree in head and neck cancer cell lines. Further, data shown in figure 3 supports the fact that IL-8 and VEGF secretion in head and neck cancer cell lines is highly dependent upon the activation of AP-1. Thus, AP-1 appears to play a critical role in the promotion of a pro-inflammatory environment in both HPV-transformed premalignant oral keratinocytes and HNSCC cell lines. And since chronic inflammation is often a central process in carcinogenesis, aberrant increases in AP-1 may be a primary mechanism for tumorigenesis in this setting.

As cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor in the development of head and neck cancer and demonstrates pro-inflammatory properties, we sought to characterize the associations between acute CSC exposure and AP-1 activity in HPV-transformed oral keratinocytes and HNSCC cell lines. We found, in both cell lines, CSC could significantly stimulate AP-1 activation above constitutive levels. A proportional increase in VEGF and IL-8 transcriptional activity was also demonstrated in time- and dose-dependent manners (Figure 4). Cytokine secretion of VEGF and IL-8 were also upregulated with exposure to CSC (Figure 6). We again utilized A-Fos to demonstrate inhibition of AP-1 activity abrogated the vehement pro-inflammatory response initiated by CSC (Figures 5 and 6). These findings suggest AP-1 plays a significant role in the heightened proinflammatory response that occurs with CSC exposure through downstream activation of VEGF and IL-8.

In a subset of head and neck cancers, HPV infection has been identified, predominantly the high risk subtype HPV-16. Thus, oral HPV infection is considered a risk factor for HNSCC [60]. As a virus, HPV does not produce its own transcription factors and relies on those provided by the host cell. Of great interest, it has been shown that AP-1 is necessary for E6 and E7 oncogene expression in HPV-16 and HPV-18 infected cells [61,62]. Our premalignant oral keratinocyte cell line, HOK-16B, has been immortalized with HPV-16. Initially, we expected to see markedly increased AP-1 levels and downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines in the invasive carcinoma cell line, as compared to the premalignant oral keratinocytes. In actuality the HPV-transformed cell line had far greater AP-1 promoter activity than the HNSCC line, both in the presence or absence of CSC treatment (Figures 2 and 4). Although IL-8 and VEGF activity was greater in the 11A cell line compared to HOK-16B, the expression variance between premalignant and malignant cells was less than expected (Figures 3 and 6). It is possible that in HOK-16B cells AP-1 is being utilized to augment viral replication, with less AP-1 available to bind the IL-8 and VEGF promoters. In the setting of CSC exposure we do see multi-fold increases in AP-1 for HPV-transformed oral keratinocytes. This suggests HPV and CSC may work synergistically to mount a strong proinflammatory response and promote malignant transformation, as HPV needs AP-1 to replicate and CSC provides an increased amount of AP-1.

We have identified the potential importance of AP-1 in the promotion of a proinflammatory cellular environment through IL-8 and VEGF expression in HPV-transformed oral keratinocytes and HNSCC cell lines. The proinflammatory role of AP-1 is particularly heightened in the presence of CSC. This information is valuable since AP-1 is considered a strong target for chemoprevention. Agents such as resveratrol, curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), quercitin and caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) all inhibit AP-1 activation to varying degrees [63]. Our results further explain why these agents may be effective inhibitors of tumorigenesis of the head and neck, particularly in the setting of tobacco or HPV exposure.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Lions 5M Translational Biomarker Initiatives for Medical Students (FGO), Minnesota Medical Foundation and the Office of Clinical Research Clinical Translational Research Program, University of Minnesota (WGS), P30 CA77598-07 NIH/NCI (FGO).

Abbreviations

- CSC

Cigarette Smoke Condensate

- AP-1

Activator Protein 1

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RLU

relative light unit

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2001;51(1):15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi SY, Kahyo H. Effect of cigarette-smoking and alcohol-consumption in the eitiology of cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;20(4):878–885. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mashberg A, Boffetta P, Winkelman R, Garfinkel L. Tobacco smoking, alcohol-drinking, and cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx among United-States vetrans. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369–1375. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::aid-cncr2820720436>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boffetta P, Mashberg A, Winkelmann R, Garfinkel L. Carcinogeneic effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on anatomic sites of the oral cavity and oropharynx. International Journal of Cancer. 1992;52(4):530–533. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Research. 1988;48(11):3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: A site-specific analysis of the SEER database. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114(5):806–816. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutirangura A, Supiyaphun P, Trirekapan S, et al. Telomerase activity in oral leukoplakia and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1996;56(15):3530–3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Califano J, Ahrendt SA, Meininger G, Westra WH, Koch WM, Sidransky D. Detection of telomerase activity in oral rinses from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Research. 1996;56(24):5720–5722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyoshi Y, Tsukinoki K, Imaizumi T, et al. Telomerase activity in oral cancer. Oral Oncology. 1999;35(3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao L, Lee JS, Fan YH, et al. Frequent microsatellite alterations at chromosomes 9p21 and 3p14 in oral premalignant lesions and their value in cancer risk assessment. Nature Medicine. 1996;2(6):682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schepman KP, vanderWaal I. A proposal for a classification and staging system for oral leukoplakia: A preliminary study. Oral Oncology-European Journal of Cancer Part B. 1995;31B(6):396–398. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raju B, Mehrotra A, Oijordsbakken G, Al-Sharabi AK, Vasstrand EN, Ibrahim SO. Expression of p53, cyclin D1 and Ki-67 in pre-malignant and malignant oral lesions: Association with clinicopathological parameters. Anticancer Research. 2005;25(6C):4699–4706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anto RJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Shishodia S, Gairola CG, Aggarwal BB. Cigarette smoke condensate activates nuclear transcription factor-kappa B through phosphorylation and degradation of I kappa B alpha: correlation with induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(9):1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ondrey FG, Dong G, Sunwoo J, et al. Constitutive activation of transcription factors NF-kappa B, AP-1, and NF-IL6 in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines that express pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic cytokines. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 1999;26(2):119–129. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199910)26:2<119::aid-mc6>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohrer J, Wuertz BRK, Ondrey F. Cigarette Smoke Condensate Induces Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Activity and Proangiogenic Growth Factors in Aerodigestive Cells. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1609–1613. doi: 10.1002/lary.20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong G, Chen Z, Kato T, Van Waes C. The host environment promotes the constitutive activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and proinflammatory cytokine expression during metastatic tumor progression of murine squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1999;59(14):3495–3504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf JS, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. IL (interleukin)-1 alpha promotes nuclear factor-kappa B and AP-1-induced IL-8 expression, cell survival, and proliferation in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7(6):1812–1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luca M, Huang SY, Gershenwald JE, Singh RK, Reich R, BarEli M. Expression of interleukin-8 by human melanoma cells up-regulates MMP-2 activity and increases tumor growth and metastasis. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;151(4):1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, Glass M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Inhibition of interleukin-8 reduces tumorigenesis of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97(12):2792–2802. doi: 10.1172/JCI118734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitadai Y, Takahashi Y, Haruma K, et al. Transfection of interleukin-8 increases angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of human gastric carcinoma cells in nude mice. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;81(4):647–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrara N, DavisSmyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocrine Reviews. 1997;18(1):4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumor-growth invivo. Nature. 1993;362(6423):841–844. doi: 10.1038/362841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravi D, Ramadas K, Mathew BS, Nalinakumari KR, Nair MK, Pillai MR. Angiogenesis during tumor progression in the oral cavity is related to reduced apoptosis and high tumor cell proliferation. Oral Oncology. 1998;34(6):543–548. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffey DC, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor-kappa B alpha of nuclear factor-kappa B in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Research. 1999;59(14):3468–3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohamed KM, Le A, Duong H, Wu YD, Zhang QZ, Messadi DV. Correlation between VEGF and HIF-1 alpha expression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2004;76(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pages G, Pouyssegur J. Transcriptional regulation of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor gene - a concert of activating factors. Cardiovascular Research. 2005;65(3):564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt D, Textor B, Pein OT, et al. Critical role for NF-kappa B-induced JunB in VEGF regulation and tumor angiogenesis. Embo Journal. 2007;26(3):710–719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobrovnikova-Marjon EV, Marjon PL, Barbash O, Jagt DLV, Abcouwer SF. Expression of angiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8/CXCL8 is highly responsive to ambient glutamine availability: Role of nuclear Factor-kappa B and activating protein-1. Cancer Research. 2004;64(14):4858–4869. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damert A, Ikeda E, Risau W. Activator-protein-1 binding potentiates the hypoxia-inducible factor-1-mediated hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation of vascular-endothelial growth factor expression in C6 glioma cells. Biochemical Journal. 1997;327:419–423. doi: 10.1042/bj3270419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SahebJamee M, Eslami M, AtarbashiMoghadam F, Sarafnejad A. Salivary concentration of TNF alpha, IL1 alpha, IL6, and IL8 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Medicina Oral Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Bucal. 2008;13(5):E292–E295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhodus NL, Ho V, Miller CS, Myers S, Ondrey F. NF-kappa B dependent cytokine levels in saliva of patients with oral preneoplastic lesions and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2004;29(1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z, Malhotra PS, Thomas GR, et al. Expression of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines in patients with head and neck cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5(6):1369–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husgafvel-Pursiainen K. Genotoxicity of environmental tobacco smoke: a review. Mutation Research-Reviews in Mutation Research. 2004;567(2–3):427–445. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandel I. Smoke signals - An alert for oral disease. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1994;125(7):872–878. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haber J, Wattles J, Crowley M, Mandell R, Joshipura K, Kent RL. Evidence for cigarette-smoking as a major risk factor for periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. 1993;64(1):16–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ismail AI, Morrison EC, Burt BA, Caffesse RG, Kavanagh MT. Natural-history of periodontal-disease in adults - Findings from the Tecumseh periodontal-disease study, 1959–87. Journal of Dental Research. 1990;69(2):430–435. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergstrom J. Cigarette-smoking as risk factor in chronic periodontal-disease. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 1989;17(5):245–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taybos G. Oral changes associated with tobacco use. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2003;326(4):179–182. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marx J. Cancer research - Inflammation and cancer: The link grows stronger. Science. 2004;306(5698):966–968. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5698.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baric JM, Alman JE, Feldman RS, Chauncey HH. Inflence of cigarette, pipe, and cigar smoking, removable partial dentures, and age on oral leukoplakia. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontics. 1982;54(4):424–429. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pindborg JJ, Kiaer J, Gupta PC, Chawla TN. Studies in oral leukoplakias - Prevalence of leukoplakia among 10000 persons in Lucknow India with special reference to use of tobacco and betel nut. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1967;37(1):109. &. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banoczy J, Rigo O. Prevalence study of oral precancerous lesions within a complex screening system in Hungary. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 1991;19(5):265–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dombi C, Voros-Balog T, Czegledy A, Hermann P, Vincze N, Banoczy J. Risk group assessment of oral precancer attached to X-ray lung-screening examinations. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2001;29(1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maity A, Pore N, Lee J, Solomon D, O'Rourke DM. Epidermal growth factor receptor transcriptionally up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human glioblastoma cells via a pathway involving phosphatidylinositol 3 '-kinase and distinct from that induced by hypoxia. Cancer Research. 2000;60(20):5879–5886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olive M, Krylov D, Echlin DR, Gardner K, Taparowsky E, Vinson C. A dominant negative to activation protein-1 (AP1) that abolishes DNA binding and inhibits oncogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(30):18586–18594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonovich M, Olive M, Reed E, O'Connell B, Vinson C. Adenoviral delivery of A-FOS, an AP-1 dominant negative, selectively inhibits drug resistance in two human cancer cell lines. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2002;9(1):62–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yasumoto K, Okamoto S, Mukaida N, Murakami S, Mai M, Matsushima K. Tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha and interferon-gamma synergistically induce interleukin-8 production in a human gastric cancer cell line through acting concurrently on AP-1 and NF-KB-like binding sites of the interleukin-8 gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(31):22506–22511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamoto SI, Mukaida N, Yasumoto K, et al. The interleukin-8 AP-1 and KAPPAB- like sites are genetic end targets of FK5O6-sensitive pathway accompanied by calcium mobilization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(11):8582–8589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukaida N, Okamoto S, Ishikawa Y, Matsushima K. Molecular mechanism of interleukin-8 gene-expression. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1994;56(5):554–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murayama T, Ohara Y, Obuchi M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus induces interleukin-8 production by a human monocytic cell line, THP-1, through acting concurrently on AP-1- and NF-kappa B-binding sites of the interleukin-8 gene. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(7):5692–5695. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5692-5695.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, et al. The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(18):11947–11954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diaz BV, Lenoir MC, Ladoux A, Frelin C, Demarchez M, Michel S. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human keratinocytes by retinoids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(1):642–650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li JJ, Rhim JS, Schlegel R, Vousden KH, Colburn NH. Expression of dominant negative Jun inhibits elevated AP-1 and NF-kappaB transactivation and suppresses anchorage independent growth of HPV immortalized human keratinocytes. Oncogene. 1998;16(21):2711–2721. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li JJ, Cao Y, Young MR, Colburn NH. Induced expression of dominant-negative c-jun downregulates NFkappaB and AP-1 target genes and suppresses tumor phenotype in human keratinocytes. Mol Carcinog. 2000;29(3):159–169. doi: 10.1002/1098-2744(200011)29:3<159::aid-mc5>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4(5):E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ness RB, Modugno F. Endometriosis as a model for inflammation-hormone interactions in ovarian and breast cancers. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(6):691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Kempen LCL, de Visser KE, Coussens LM. Inflammation, proteases and cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(6):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Platz EA, et al. Pathological and molecular mechanisms of prostate carcinogenesis: Implications for diagnosis, detection, prevention, and treatment. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2004;91(3):459–477. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2005;14(2):467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Offord EA, Beard P. A member of the activator protein-1 family found in keratinocytes but not in fibroblasts required for transcription from a human papillomavirus type-18 promoter. Journal of Virology. 1990;64(10):4792–4798. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4792-4798.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan WK, Chong T, Bernard HU, Klock G. Transcription of the transforming genes of the oncogenic human papillomavirus-16 is stimulated by tumor promoters through AP1 binding sites. Nucleic Acids Research. 1990;18(4):763–769. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matthews CP, Colburn NH, Young MR. AP-1 a target for cancer prevention. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(4):317–324. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]