Abstract

Background

High blood pressure is an important public health problem because of associated risks of stroke and cardiovascular events. Antihypertensive drugs are often used in the belief that lowering blood pressure will prevent cardiac events, including myocardial infarction and sudden death (death of unknown cause within one hour of the onset of acute symptoms or within 24 hours of observation of the patient as alive and symptom free).

Objectives

To assess the effects of antihypertensive pharmacotherapy in preventing sudden death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and fatal myocardial infarction among hypertensive individuals.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register (all years to January 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (2016, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to January 2016), Ovid EMBASE (1980 to January 2016) and ClinicalTrials.gov (all years to January 2016).

Selection criteria

All randomised trials evaluating any antihypertensive drug treatment for hypertension, defined, when possible, as baseline resting systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mmHg and/or resting diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mmHg. Comparisons included one or more antihypertensive drugs versus placebo, or versus no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently extracted data. Outcomes assessed were sudden death, fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction and change in blood pressure.

Main results

We included 15 trials (39,908 participants) that evaluated antihypertensive pharmacotherapy for a mean duration of follow‐up of 4.2 years. This review provides moderate‐quality evidence to show that antihypertensive drugs do not reduce sudden death (risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.15) but do reduce both non‐fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74, 0.98; absolute risk reduction (ARR) 0.3% over 4.2 years) and fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.90; ARR 0.3% over 4.2 years). Withdrawals due to adverse effects were increased in the drug treatment group to 12.8%, as compared with 6.2% in the no treatment group.

Authors' conclusions

Although antihypertensive drugs reduce the incidence of fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction, they do not appear to reduce the incidence of sudden death. This suggests that sudden cardiac death may not be caused primarily by acute myocardial infarction. Continued research is needed to determine the causes of sudden cardiac death.

Keywords: Humans; Antihypertensive Agents; Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use; Death, Sudden, Cardiac; Death, Sudden, Cardiac/prevention & control; Hypertension; Hypertension/complications; Hypertension/drug therapy; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Drugs used to lower blood pressure do not reduce sudden death

High blood pressure increases risks of stroke and heart attack. In people with moderate elevations of blood pressure, drugs that lower blood pressure reduce the incidence of stroke and heart attack. It is not known whether blood pressure‐lowering drugs reduce sudden death (death of unknown cause within one hour of the onset of acute symptoms or within 24 hours of observation of the patient as alive and symptom free). We found 15 trials including 39,908 people that investigated whether blood pressure‐lowering drugs reduce sudden death. This review presents moderate‐quality evidence to show that blood pressure‐lowering drugs reduce heart attacks but do not appear to reduce sudden cardiac death. This suggests that sudden cardiac death may not be caused primarily by heart attack. Continued research is needed to determine the causes of sudden cardiac death.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy versus control for prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertensive individuals.

| Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy versus control for prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertensive individuals | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with hypertension (defined as baseline systolic resting blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or resting diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) Setting: primary care outpatient Intervention: antihypertensive pharmacotherapy (first‐line thiazide, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, calcium channel blocker or beta‐blocker) Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with antihypertensive pharmacotherapy | |||||

| Sudden cardiac death (mean follow‐up: 4.2 years) |

Study population | RR 0.96 (0.81 to 1.15) | 39908 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 13 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (10 to 14) | |||||

| Non‐fatal myocardial infarction (mean follow‐up: 4.2 years) | Study population | RR 0.85

(0.74 to 0.98) |

39908 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 20 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (15 to 20) | |||||

| Fatal myocardial infarction (mean follow‐up: 4.2 years) | Study population | RR 0.75

(0.62 to 0.90) |

39908 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (7 to 11) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect but may be substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals)

Background

Description of the condition

High blood pressure is an important public health problem because of associated risks of stroke and cardiovascular events. It is most often of unknown origin, is relatively easy to detect and can be lowered with antihypertensive drugs. Extensive epidemiological data support the well‐known relationship between blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease, particularly the importance of systolic blood pressure as a determinant of risk (Glynn 2010).

Major coronary heart disease manifests as and is captured in trials by three different outcomes: non‐fatal myocardial infarction, fatal myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Antihypertensive therapy could have different effects on different outcomes, and some study authors suspect that it could increase the incidence of sudden cardiac death (Hoes 1994), which is defined as sudden unexpected death within one hour of the onset of acute symptoms or within 24 hours of observation of the patient as alive and symptom free (Chugh 2004).

Most reviews have focused on the effects of blood pressure‐lowering drugs on total fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction, but not specifically on sudden cardiac death. Instead, sudden cardiac death is included with total myocardial infarction because it is assumed that it is totally or most often caused by acute myocardial infarction. In fact, sudden cardiac death could have several causes not related to acute myocardial infarction (see below) (Zheng 2001).

Description of the intervention

The intervention of interest in this systematic review is any antihypertensive drug used alone or in combination with other antihypertensive drugs as part of stepped‐care therapy. The control in this review is placebo or no treatment.

How the intervention might work

Antihypertensive drugs lower blood pressure through a variety of mechanisms. Major classes of antihypertensive drugs include thiazide diuretics, beta‐blockers, drugs inhibiting the renin‐angiotensin system, calcium channel blockers, direct vasodilators, centrally active drugs and others. Several systematic reviews have shown the benefits of antihypertensive drug therapy in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients of all ages with moderate to severe hypertension (Gueyffier 1999; Musini 2009). At the present time, it is not known whether the benefits of antihypertensive therapy outweigh the harms in individuals with uncomplicated mild (grade 1) hypertension (Diao 2012; Sundström 2015).

It has been hypothesised, but not proven, that the benefits of antihypertensive drugs in reducing the incidence of stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure are mediated through blood pressure reduction. If this is so, all drugs that lower blood pressure to the same degree should be similarly effective in reducing cardiovascular events. Some evidence suggests that this is not the case, and that different classes of antihypertensive drugs have differential effects on different outcomes (Chen 2010; Wiysonge 2012; Wright 2009; Xue 2015).

Effects of antihypertensive drugs on sudden cardiac death are potentially more complicated, as sudden cardiac death could be caused by acute myocardial infarction, but also could result from spontaneous fatal arrhythmia (ventricular fibrillation, torsade de pointes, asystole) or another sudden fatal event (e.g. ruptured aortic aneurysm, intracerebral haemorrhage). A particular class of antihypertensive drugs could be beneficial for one cause and deleterious for another. Other causes of sudden death cannot be ruled out because autopsies are not systematically done even in the event of sudden death in a randomised trial.

Why it is important to do this review

No published systematic review has compared the effects of antihypertensive drugs versus placebo or no treatment on the incidence of sudden cardiac death. If antihypertensive pharmacotherapy or a specific class of antihypertensive therapy increases sudden cardiac death, it is important to establish this, as it raises important questions: Is it appropriate to classify sudden cardiac death under total myocardial infarction? Are approaches available to prevent the increase in sudden cardiac death associated with use of antihypertensive drugs? Should patients with a particularly increased risk of sudden cardiac death be identified and treated differently?

Objectives

To assess the effects of antihypertensive pharmacotherapy in preventing sudden cardiac death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and fatal myocardial infarction among hypertensive individuals.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs in predominantly hypertensive patients (> 50%) with duration of follow‐up of at least one year. Trials must include a comparative control group given placebo or no treatment.

We excluded trials that compared two specific antihypertensive therapies without placebo or with no treatment control, trials of blood pressure‐lowering devices and trials providing multi‐factorial interventions.

Trials had to provide data on the incidence of sudden cardiac death among participants in treated and control groups.

Types of participants

Most participants must have had high blood pressure (> 50%) at baseline. High blood pressure is defined as baseline resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 140 mmHg and/or resting diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 90 mmHg.

Trials were not limited by any other factor nor by baseline risk. We excluded trials that recruited participants in the first month following an acute cardiovascular event.

Types of interventions

Treatment interventions

Antihypertensive drug classes, including angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, renin inhibitors, beta‐adrenergic blockers, combined alpha‐ and beta‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, alpha‐adrenergic blockers, central sympatholytics, direct vasodilators and antihypertensive drugs with unknown mechanisms of action.

Control interventions

Placebo and no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Sudden cardiac death.

Secondary outcomes

Fatal myocardial infarction.

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

Withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) for related reviews.

This review falls within the scope of the search strategies developed for Wright 2009, for which we searched the following databases: the Hypertension Group Specialised Register (all years to January 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (2016, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to January 2016), Ovid EMBASE (1980 to January 2016), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (all years to January 2016), and ClinicalTrials.gov (all years to January 2016).

The Hypertension Group Specialised Register includes controlled trials from searches of CAB Abstracts, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, Food Science and Technology Abstracts (FSTA), Global Health, the Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), MEDLINE, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, PsycINFO, Web of Science and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

We searched electronic databases using a strategy that combined the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE (sensitivity‐maximising version (2008 revision)) with selected Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and free text terms. We applied no language restrictions. We translated the MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) for use with EMBASE, CENTRAL, the Hypertension Group Specialised Register and ClinicalTrials.gov, using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all relevant studies and systematic reviews for additional studies. We contacted authors of included studies to request information about any other relevant unpublished or ongoing studies.

We examined other sources to retrieve potential studies for the review:

Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to ask whether this group had related clinical trial information in its possession.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

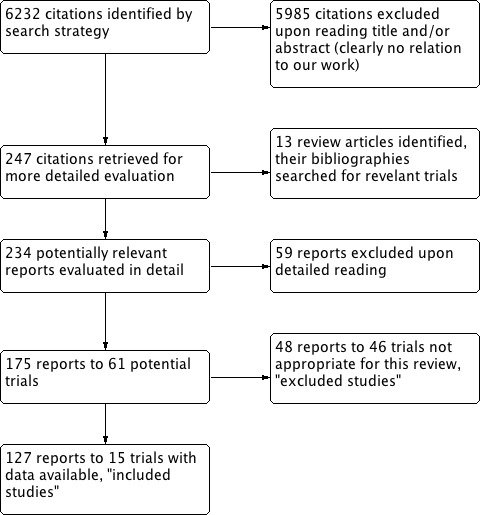

One review author (GT) screened citations/abstracts obtained as a result of the search strategies. We rejected articles on the initial screen if we determined from the title or from the abstract that the article was not a report of a randomised clinical trial. We also rejected articles that were irrelevant to the review, or that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. We obtained in full text trials that might be of relevance and citations of uncertain relevance. Two review authors (GT, YM) independently assessed full‐text articles for inclusion, using predetermined inclusion criteria. We recorded reasons for exclusion of trials. We provided a full accounting of search results in the form of a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) study flow diagram (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We extracted and managed data using the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.3. Review authors (GT, YM, AL, LT and JMW) extracted data independently, using a piloted, standard form, then cross‐checked data. We resolved discrepancies by discussion and by consensus, or we sought adjudication by a third review author if we could not reach consensus.

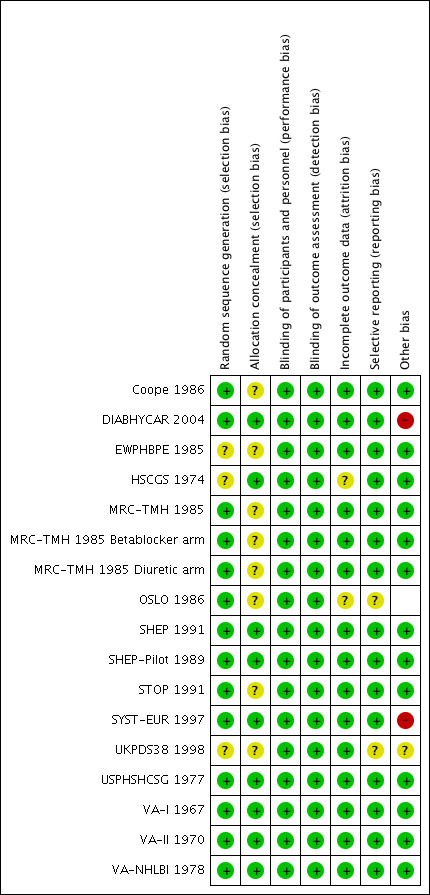

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors used the 'Risk of bias' tool to assess each trial according to guidelines provided in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Potential parameters of methodological quality listed in the 'Risk of bias' table include method used to randomise participants; whether randomisation was completed in an appropriate and blinded manner; whether participants, providers and/or outcome assessors were blinded to assigned therapy; whether the control group received placebo or no treatment; the proportion of participants who did not complete follow‐up; selective reporting of outcomes; and any other biases, including whether or not funding was provided by the drug industry.

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias within each included study on the basis of these domains, assigning ratings of 'low risk of bias', 'high risk of bias' and 'unclear risk of bias' (uncertain risk of bias). Review authors resolved disagreements by discussion or by obtaining a third party opinion. When published articles did not include sufficient detail to permit full assessment, we contacted study authors to ask for clarification of methods used.

We presented the risk of bias assessment in a table for each study.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured most of our outcomes as the proportion of participants suffering an event, including sudden cardiac death, fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and withdrawal due to adverse effects. When performing a meta‐analysis, we used risk ratios.

Unit of analysis issues

For the subgroup analysis of the two‐arm Medical Research Council (MRC) trial (MRC‐TMH 1985), we halved the placebo group to prevent double counting.

Dealing with missing data

When information was missing from the included studies, we contacted investigators (using email, letter and/or fax) to request the missing information, and we explored the INDANA (Individual Data Analysis of Antihypertensive Drug Intervention Trials) database.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented data on the following outcomes: sudden cardiac death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, fatal myocardial infarction and proportion of participants who experienced at least one withdrawal due to an adverse event. We presented dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We presented data regarding numbers of participants and studies for each outcome. We used the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (Grade working group 2004) to determine the quality of the evidence and downgraded the quality if (1) most (> 50%) included studies had high risk of bias; (2) the outcome had significant statistical heterogeneity (I² > 50%); and (3) the outcome had wide 95% CIs, indicating that the intervention effect was highly variable.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials by using a standard Chi2 statistic for heterogeneity and an alpha of 0.05 for statistical significance, and we estimated heterogeneity using the I2 test. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

We applied the fixed‐effect model to obtain summary statistics of pooled trials, unless significant between‐study heterogeneity was present, in which case we used the random‐effects model. If significant heterogeneity was present, and if I2 was greater than 50%, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (variation in trial methods, interventions and study population characteristics) in an attempt to find potential explanations for the observed variation.

Assessment of reporting biases

Positive results are consistently more likely to be published than negative results, leading to publication bias, which can result in overestimation of the effect size of studies. If we identified sufficient trials (≥ 10 studies), we visually inspected funnel plots for small‐study effects, and we considered the causes of funnel plot asymmetry, including publication bias. We considered use of additional statistical tests such as Egger's test when appropriate (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions).

Data synthesis

We performed data synthesis and analyses using the most current version of the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.3.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to look for variation in treatment effect among classes of first‐line antihypertensive drugs, namely, first‐line diuretics versus other first‐line antihypertensive drugs.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to test for robustness of results on trial quality. We did this by restricting analyses to trials with placebo and those judged to have low risk of bias. We also performed sensitivity analyses to see whether recruiting only patients with diabetes affected trial results.

Results

Description of studies

Details for the included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table. Reasons for exclusion of excluded trials can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Results of the search

We identified 61 trials, included 15 trials (39,908 participants) and excluded 46 trials. We have summarised the study selection process in the PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Included studies

We have provided details of included trials in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Studies recruited patients with high blood pressure, defined as baseline resting SBP of at least 140 mmHg and/or resting DBP of at least 90 mmHg. The average age of participants across all included trials was 63 years. Mean follow‐up of studies ranged from 1.5 to 8.3 years. Most participants were recruited from industrialised countries, including the USA (57%) and European multi‐sites (43%). Most trials evaluated first‐line diuretics (EWPHBPE 1985; HSCGS 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985 Diuretic arm; OSLO 1986; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐Pilot 1989: USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐I 1967; VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1978), except for DIABHYCAR 2004 and UKPDS38 1998, both of which evaluated an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, and SYST‐EUR 1997, which evaluated a first‐line calcium channel blocker. Five trials evaluated first‐line beta‐blockers (Coope 1986; MRC‐TMH 1985 Betablocker arm; OSLO 1986; STOP 1991; UKPDS38 1998). Females represented 38% of the population studied. Four trials (OSLO 1986; VA‐I 1967; VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1978) included only men (2320 participants). Eight trials reported ethnicity. African Americans accounted for the following percentages in these trials: HSCGS 1974 80%; SHEP 1991 13.8%; SHEP‐Pilot 1989 18%; USPHSHCSG 1977 28%; VA‐I 1967 53.8%; VA‐II 1970 42%; VA‐NHLBI 1978 25%; and UKPDS38 1998 8%. Seven trials did not report ethnicity (Coope 1986; DIABHYCAR 2004; EWPHBPE 1985; MRC‐TMH 1985; OSLO 1986; STOP 1991; SYST‐EUR 1997). Twelve trials reported initial mean SBP of participants ranging from 145 mmHg to 196 mmHg and DBP ranging from 75 mmHg to 102 mmHg. The final mean SBP ranged from 127 mmHg to 180 mmHg and DBP from 44 mmHg to 92 mmHg. Two studies (VA‐I 1967; VA‐NHLBI 1978) reported initial and final mean DBP: respectively, VA‐I 1967 121 mmHg and 91 mmHg, and VA‐NHLBI 1978 93 mmHg and 83 mmHg. VA‐II 1970 reported only the initial mean SBP/DBP: 164/104 mmHg. Ten trials reported baseline prevalence of diabetes as follows: Coope 1986 0%; DIABHYCAR 2004 100%; EWPHBPE 1985 0%; MRC‐TMH 1985 0%; SHEP 1991 10.1%; SYST‐EUR 1997 10.5%; UKPDS38 1998 100%; USPHSHCSG 1977 0%; VA‐I 1967 9.1%; and VA‐NHLBI 1978 0%. Three trials (SHEP 1991; SHEP‐Pilot 1989; SYST‐EUR 1997) restricted recruitment to persons with systolic hypertension, defined as SBP 160 to 219 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg (SHEP 1991; SHEP‐Pilot 1989), DBP < 95 mmHg (SYST‐EUR 1997) or simply systolic > 140 mmHg (DIABHYCAR 2004). Five trials based entry on diastolic hypertension (USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐I 1967; VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1978; UKPDS38 1998); six trials based entry on either systolic or diastolic hypertension (Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1985; HSCGS 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985; OSLO 1986; STOP 1991).

Excluded studies

We excluded 46 trials and have provided reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias from six domains for each of the included studies.

Allocation

We judged most of the trials as having low risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment. For trials with insufficient reporting, we judged risk of bias as unclear.

Blinding

Twelve of the 15 trials blinded participants to therapy (DIABHYCAR 2004; EWPHBPE 1985; HSCGS 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐Pilot 1989; STOP 1991; SYST‐EUR 1997; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐I 1967; VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1978) and of these all but MRC‐TMH 1985 also blinded providers to therapy. Eight trials specifically reported blinding of outcome assessors (Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1985; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐Pilot 1989; STOP 1991; SYST‐EUR 1997; UKPDS38 1998; VA‐II 1970).

Incomplete outcome data

Participants who were lost to follow‐up or who dropped out prematurely were usually included in the clinical outcome or safety analysis of each trial. Most trials used intention‐to‐treat analysis; we therefore judged them to have low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All studies reported sudden cardiac death and myocardial infarction numbers; therefore, we can consider them as having low risk of reporting bias.

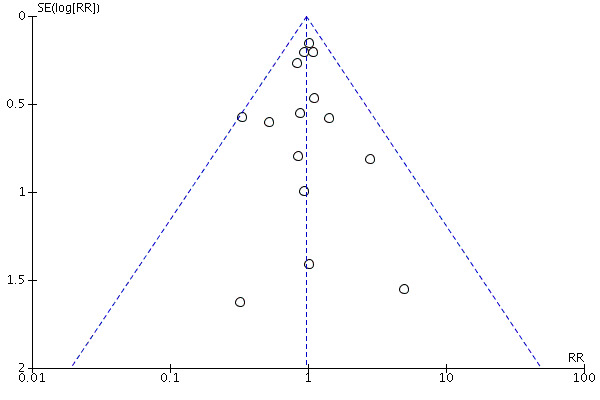

Other potential sources of bias

We defined publication bias as selective publication of studies with positive results; this is another source of bias that may have skewed the results of this review. The most common way to investigate whether an effect estimate is subject to publication bias is to examine for funnel plot asymmetry. Examining the funnel plot for sudden cardiac death in this review revealed no asymmetry to suggest high risk of publication bias (Figure 2).

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control, outcome: 1.1 Sudden cardiac death.

Thirteen of the 15 trials were funded by government agencies, not by industry, and thus were judged to have low risk of other bias.

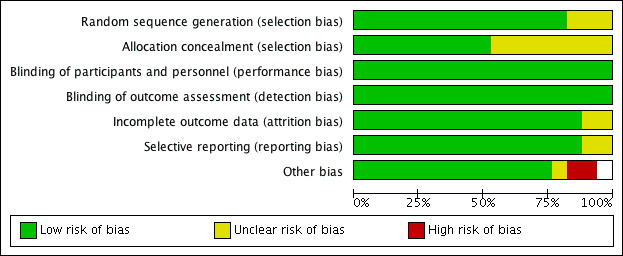

We have summarised our judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study and about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1. We performed analyses on the combined results of all 15 studies.

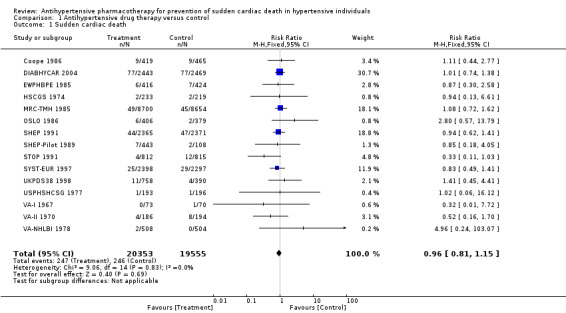

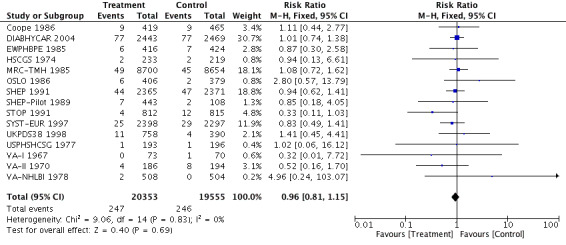

Sudden cardiac death

For the 39,908 participants included in this review, treatment with antihypertensive drugs as compared with no treatment or placebo did not affect sudden cardiac death (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.1) (Analysis 1.1, Figure 5).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 1 Sudden cardiac death.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control, outcome: 1.1 Sudden cardiac death.

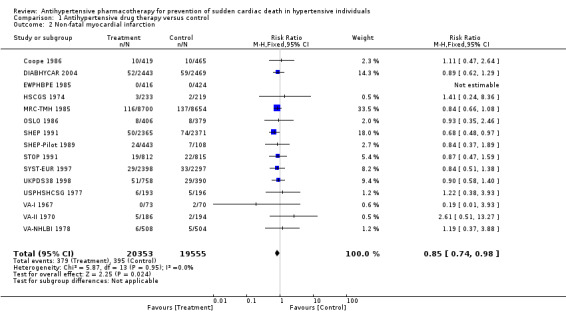

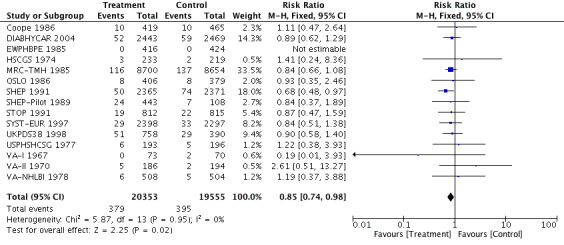

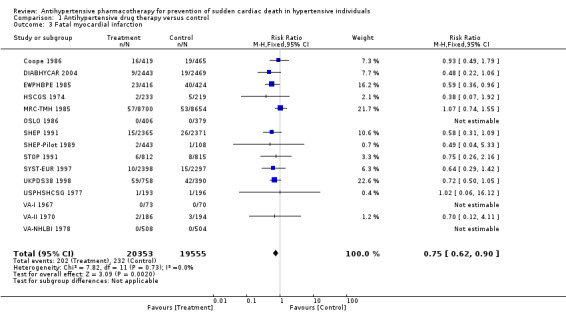

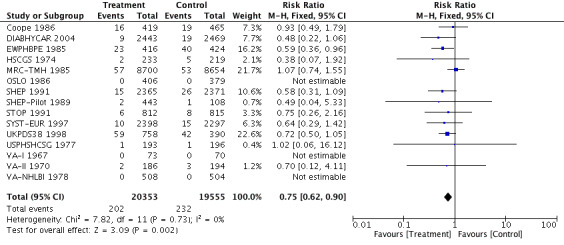

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction and fatal myocardial infarction

Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy resulted in a significant reduction in non‐fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98, ARR 0.3% over 4.2 years) (Analysis 1.2, Figure 6) and fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.90, ARR 0.3% over 4.2 years) (Analysis 1.3, Figure 7). We found no evidence of heterogeneity among included trials.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 2 Non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control, outcome: 1.2 Non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 3 Fatal myocardial infarction.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control, outcome: 1.3 Fatal myocardial infarction.

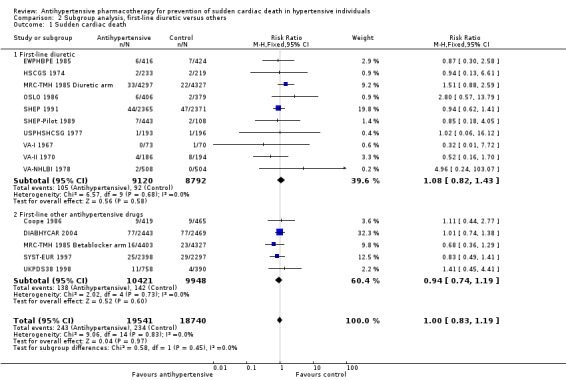

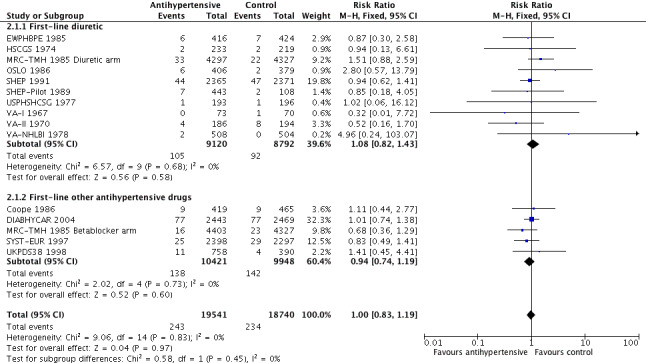

Subgroup analysis

To analyse whether a class effect of drugs was evident, we performed a subgroup analysis of first‐line diuretics versus other antihypertensive drugs. In clinical trials, medications given to treat hypertension are often added to achieve the goal of lowering blood pressure. For this reason, we analysed data related to first‐line treatment only.

The risk ratio for sudden cardiac death was 1.08 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.43) when diuretics were used as first‐line agents, and 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) for other antihypertensive treatments (Analysis 2.1, Figure 8). We noted no significant heterogeneity between subgroups based on use of first‐line drugs.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis, first‐line diuretic versus others, Outcome 1 Sudden cardiac death.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Subgroup analysis, first‐line diuretic versus others, outcome: 3.1 Sudden cardiac death.

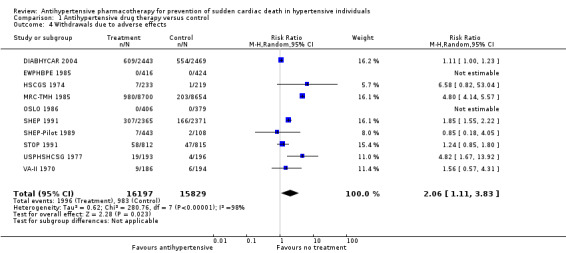

Withdrawals due to adverse effects (WDAEs)

Ten of 15 trials reported the numbers of participants who dropped out of trials because of adverse drug effects. WDAEs occurred in 6.2% of the no treatment group, and this percentage increased to 12.8% in the drug treatment group (RR 2.06, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.83, absolute risk increase 6.6%). Heterogeneity was high for this outcome (I2 = 98%).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Fifteen trials evaluated antihypertensive pharmacotherapy of various drug classes in a total of 39,908 hypertensive individuals, with periods of follow‐up ranging from 1.5 to nine years (mean 4.2 years).

This systematic review demonstrates that antihypertensive pharmacotherapy used in the treatment of hypertensive patients has not been proven to significantly reduce sudden cardiac death (risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.15). In contrast, in the same trials, antihypertensive therapy reduced both non‐fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98) and fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.90).

These findings suggest that sudden cardiac death is not totally or mostly caused by acute myocardial infarction, as if this were the case, it would have been reduced by antihypertensive therapy to a similar degree (e.g. RR 0.72 to 0.82). Therefore, sudden cardiac death could most often result from a condition unaffected by antihypertensive therapy, or more likely is caused in part by acute myocardial infarction and is reduced by antihypertensive therapy and is caused in part as well by another mechanism (e.g. ventricular arrhythmias), which is increased by antihypertensive therapy, resulting in an overall null effect.

High blood pressure is a well‐known risk factor for cardiac hypertrophy. Increased left ventricular mass detected by echocardiography is associated with increased risk for sudden cardiac death after other known coronary disease risk factors were accounted for (Haider A). It is unclear, however, whether antihypertensive therapies that promote the regression of left ventricular hypertrophy would reduce the risk of sudden death (Messerli 1999). These facts make the lack of risk reduction of sudden death difficult to explain, unless we assume that at least some antihypertensive drugs may increase the incidence of sudden death. Diuretics have long been suspected to potentially induce sudden death by causing hypokalaemia and subsequent ventricular arrhythmia (Hoes 1995). On the other hand, beta‐blockers are supposed to prevent sudden death due to arrhythmia (Hjalmarson 1997; Kaplan 1997), at least for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.

In this review, we tested this possibility by performing a subgroup analysis of diuretics versus control for sudden cardiac death; we found that the pooled risk ratio of 1.08 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.43) did not affirm a differential effect for diuretics, and the pooled effect for other drugs was not different (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.19). However, so few trials used other first‐line antihypertensive drugs that the subgroup analysis was not a good test of that possibility. Sudden death represents 19.4% of total deaths and is more frequent than fatal myocardial infarction (13.4% of total deaths). It has been estimated that 40.7% of sudden deaths are due to coronary causes (Loire 1996), providing the rationale for including them within major coronary events. In North America and Europe, their annual incidence ranges from 50 to 100 per 100,000 in the general population (Byrne 2008; Chugh 2004; Vreede‐Swagemakers 1997; Vaillancourt 2004).

The fact that antihypertensive pharmacotherapy does not prevent this frequent cause of death is a matter of public health concern. One important improvement in coronary death prevention seen during the past two decades results from coronary angioplasty in acute coronary syndrome. These results, however, do not call into question the prescription of antihypertensive drugs, which remain associated with a significant reduction in coronary and cerebrovascular events. This shows that additional research is needed to determine the causes of sudden death. It also suggests that sudden cardiac death may be a misnomer, and that until we have attained a good estimate of its different causes, this might be better labelled 'sudden death'.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This comprehensive review provides the most up‐to‐date evidence from available randomised controlled trials. We have done our best to contact study authors to collect data on sudden cardiac death from the more recent studies (HOPE 2000; HYVET 2008; HYVET‐Pilot 2003), which did not report it. We applied no language restrictions when selecting studies.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, we judged the risk of bias of studies included in this review as moderate to low. However, only six of the 15 trials (53%) described the method of concealment of allocation. Most trials with unclear concealment of allocation were described as 'randomised', and study authors provided no other details. Some study authors stated that these trials were double‐blind but offered no information about how this was achieved.

Potential biases in the review process

One potential bias that deserves attention is the fact that most trials used a combination of antihypertensive medications as stepped‐care therapy. As a result, the drugs used and the amount of blood pressure reduction achieved were heterogeneous.

For most long‐term and large‐scale studies, it is impossible to maintain single first‐line drug treatment because a single drug frequently does not lower blood pressure to a level considered low enough. In most cases, physicians in the included studies added other antihypertensive drugs (e.g. reserpine) to reach the target blood pressure. We excluded many studies because they did not report the incidence of sudden cardiac death. This lack of completeness could have biased the analysis, but as most of these eligible studies were published before 1991, it is unlikely that their data will become available.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first systematic review undertaken to specifically assess the effects of antihypertensive therapy on sudden cardiac death. Estimates of effects of risk reduction on fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction provided here are similar to those reported by other reviews (Musini 2009; Wright 2009).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found moderate‐quality evidence suggesting that antihypertensive drugs lead to a small reduction in the incidence of fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction but do not reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death. This suggests that sudden cardiac death in people with hypertension may be attributable to causes other than acute myocardial infarction. Withdrawals due to adverse effects were increased in the drug treatment group to 12.8%, as compared with 6.2% in the no treatment group.

Implications for research.

Sudden death should not be included as part of a composite outcome of major coronary events in future trials. Autopsies should be performed to establish the cause of death when people die suddenly during a clinical trial. More research is needed to determine the causes of sudden death.

Future clinical trials of cardiovascular prevention should systematically and separately explore the impact of treatment on sudden death and should identify treatments that could have a preventive effect on this outcome.

Specific risk scores for sudden death should be developed so they can be used to check whether sudden death shares the same capacity for prognosis as coronary events, fatal or not, and to help identify subgroups of individuals at particularly high risk for sudden death. Sudden death risk scores might prove useful once effective preventive treatments have been identified, as is the case for beta‐blockers and aldosterone antagonists for congestive heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Hypertension Group, especially Ciprian Jauca and Douglas Salzwedel, for assistance provided.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search Date: 13 January 2016 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp thiazides/ (14683) 2 exp sodium chloride symporter inhibitors/ (13465) 3 exp sodium potassium chloride symporter inhibitors/ (12878) 4 ((ceiling or loop) adj diuretic?).tw. (2241) 5 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw. (30887) 6 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw. (2099) 7 or/1‐6 [THZ] (45504) 8 exp angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/ (39474) 9 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. (16301) 10 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. (16602) 11 acei.tw. (2437) 12 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril$ or perindopril$ or pivopril or quinapril$ or ramipril$ or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril$ or temocapril$ or teprotide or trandolapril$ or utibapril$ or zabicipril$ or zofenopril$ or Aceon or Accupril or Altace or Capoten or Lotensin or Mavik or Monopril or Prinivil or Univas or Vasotec or Zestril).tw. (24224) 13 or/8‐12 [ACEI] (53318) 14 exp Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists/ (18967) 15 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw. (10209) 16 arb?.tw. (4325) 17 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan or Atacand or Avapro or Benicar or Cozaar or Diovan or Micardis or Teveten).tw. (13440) 18 or/14‐17 [ARB] (26495) 19 exp calcium channel blockers/ (75134) 20 (amlodipine or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil or Cardizem CD or Dilacor XR or Tiazac or Cardizem Calan or Isoptin or Calan SR or Isoptin SR Coer or Covera HS or Verelan PM).tw. (56470) 21 (calcium adj2 (antagonist? or block$ or inhibit$)).tw. (34966) 22 or/19‐21 [CCB] (100015) 23 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. (14779) 24 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. (19670) 25 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. (18463) 26 exp hydralazine/ (4535) 27 (hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw. (4154) 28 or/23‐27 [CNS] (55461) 29 exp adrenergic beta‐antagonists/ (78226) 30 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. (57382) 31 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. (88421) 32 or/29‐31 [BB] (142694) 33 exp adrenergic alpha antagonists/ (47587) 34 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw. (12922) 35 (adrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw. (18584) 36 ((adrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw. (51526) 37 or/33‐36 [AB] (104492) 38 hypertension/ (205857) 39 hypertens$.tw. (320460) 40 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. (22415) 41 or/38‐40 (378583) 42 randomized controlled trial.pt. (403223) 43 controlled clinical trial.pt. (89924) 44 randomized.ab. (300551) 45 placebo.ab. (154066) 46 clinical trials as topic/ (174243) 47 randomly.ab. (213007) 48 trial.ti. (130278) 49 or/42‐48 (921351) 50 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) (4139775) 51 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ (808940) 52 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. (12542) 53 49 not (50 or 51 or 52) (812533) 54 (7 or 13 or 18 or 22 or 28 or 32 or 37) and 41 and 53 (15322) 55 54 and (2015$ or 2016$).ed. (284) 56 remove duplicates from 55 (276) *************************** Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on Wiley <Issue 1, 2016> via Cochrane Register of Studies Online Search Date: 14 January 2016 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1MeSH descriptor Thiazides explode all trees2247 #2MeSH descriptor Sodium Chloride Symporter Inhibitors explode all trees2703 #3MeSH descriptor Sodium Potassium Chloride Symporter Inhibitors explode all trees967 #4(loop or ceiling) next diuretic*:ti,ab324 #5(amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide*):ti,ab4836 #6(chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide):ti,ab894 #7#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #66356 #8MeSH descriptor Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors explode all trees5527 #9"angiotensin converting enzyme" next inhibit*:ti,ab2838 #10ace near3 inhibit*:ti,ab2849 #11acei:ti,ab525 #12(alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril* or perindopril* or pivopril or quinapril* or ramipril* or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril* or temocapril* or teprotide or trandolapril* or utibapril* or zabicipril* or zofenopril*):ti,ab7364 #13#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #1210002 #14MeSH descriptor Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists explode all trees2422 #15angiotensin near3 (receptor next antagon* or receptor next block*):ti,ab1960 #16arbs:ti,ab338 #17(abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan):ti,ab4511 #18#14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #175317 #19MeSH descriptor Calcium Channel Blockers explode all trees7947 #20(amlodipine or amrinone or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil):ti,ab11089 #21calcium near2 (antagonist* or block* or inhibit*):ti,ab4116 #22#19 OR #20 OR #2113599 #23(methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa):ti,ab,kw567 #24(reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil):ti,ab,kw231 #25(clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets):ti,ab,kw2648 #26MeSH descriptor Hydralazine explode all trees299 #27(hydralazin* or hydrallazin* or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat):ti,ab,kw431 #28#23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #273837 #29MeSH descriptor Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists explode all trees9425 #30(acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol):ti,ab13596 #31beta near2 (adrenergic* or antagonist* or block* or receptor*):ti,ab8436 #32#29 OR #30 OR #3117593 #33MeSH descriptor Adrenergic alpha‐Antagonists explode all trees2966 #34(alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin):ti,ab1992 #35adrenergic near2 (alpha or antagonist*):ti,ab402 #36(adrenergic or alpha or receptor*) near2 block*:ti,ab5466 #37#33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #368851 #38MeSH descriptor Hypertension13751 #39hypertens*:ti,ab31186 #40(elevat* or high* or raise*) near2 blood pressure:ti,ab1976 #41#38 OR #39 OR #4033478 #42#7 OR #13 OR #18 OR #22 OR #28 OR #32 OR #3747478 #43#41 AND #4216338 *************************** Database: Embase <1974 to 2016 January 12> Search Date: 13 January 2016 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp thiazide diuretic agent/ (49977) 2 exp loop diuretic agent/ (61804) 3 ((loop or ceiling) adj diuretic?).tw. (3467) 4 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw. (40241) 5 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw. (3621) 6 or/1‐5 [THZ] (115178) 7 exp dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase inhibitor/ (146016) 8 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. (21265) 9 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. (25386) 10 acei.tw. (5169) 11 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril$ or perindopril$ or pivopril or quinapril$ or ramipril$ or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril$ or temocapril$ or teprotide or trandolapril$ or utibapril$ or zabicipril$ or zofenopril$ or Aceon or Accupril or Altace or Capoten or Lotensin or Mavik or Monopril or Prinivil or Univas or Vasotec or Zestril).tw. (34232) 12 or/7‐11 [ACEI] (154116) 13 exp angiotensin receptor antagonist/ (68667) 14 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw. (15952) 15 arb?.tw. (9450) 16 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan or Atacand or Avapro or Benicar or Cozaar or Diovan or Micardis or Teveten).tw. (22408) 17 or/13‐16 [ARB] (74373) 18 calcium channel blocking agent/ (51954) 19 (amlodipine or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil or Cardizem CD or Dilacor XR or Tiazac or Cardizem Calan or Isoptin or Calan SR or Isoptin SR Coer or Covera HS or Verelan PM).tw. (75122) 20 (calcium adj2 (antagonist? or block$ or inhibit$)).tw. (45137) 21 or/18‐20 [CCB] (133231) 22 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. (27831) 23 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. (30770) 24 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. (44044) 25 hydralazine/ (17592) 26 (hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw. (6203) 27 or/22‐26 [CNS] (105686) 28 exp beta adrenergic receptor blocking agent/ (253415) 29 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. (76208) 30 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. (110070) 31 or/28‐30 [BB] (306054) 32 exp alpha adrenergic receptor blocking agent/ (126208) 33 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw. (15975) 34 (adrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw. (17678) 35 ((adrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw. (67235) 36 or/32‐35 [AB] (190161) 37 exp hypertension/ (556409) 38 (hypertens$ or antihypertens$).tw. (508004) 39 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. (32657) 40 or/37‐39 (730540) 41 double blind$.mp. (203065) 42 placebo$.tw. (230914) 43 blind$.tw. (310333) 44 or/41‐43 (449503) 45 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) (5742913) 46 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ (614605) 47 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. (18262) 48 44 not (45 or 46 or 47) (417356) 49 (6 or 12 or 17 or 21 or 27 or 31 or 36) and 40 and 48 (12964) 50 49 and (2015$ or 2016$).em. (421) 51 remove duplicates from 50 (402) *************************** Database: ClinicalTrials.gov Search Date: 13 January 2016 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Search terms: randomized Study type: Interventional Studies Conditions: hypertension Interventions: antihypertensive Outcome Measures: blood pressure First Received: First Received: From 01/01/2015 to 01/13/2016 (43) ***************************

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sudden cardiac death | 15 | 39908 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.81, 1.15] |

| 2 Non‐fatal myocardial infarction | 15 | 39908 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.74, 0.98] |

| 3 Fatal myocardial infarction | 15 | 39908 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.62, 0.90] |

| 4 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 10 | 32026 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.06 [1.11, 3.83] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 4 Withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Comparison 2. Subgroup analysis, first‐line diuretic versus others.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sudden cardiac death | 15 | 38281 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.83, 1.19] |

| 1.1 First‐line diuretic | 10 | 17912 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.82, 1.43] |

| 1.2 First‐line other antihypertensive drugs | 5 | 20369 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.74, 1.19] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Coope 1986.

| Methods | Randomised controlled group Trial conducted in Europe |

|

| Participants | Patients 60 to 79 years of age who were registered in 13 general practices in England and Wales | |

| Interventions | Atenolol 100 mg (± bendrofluazide 5 mg ± alpha‐methyldopa 500 mg) Control: no treatment |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality Systolic BP and diastolic BP Stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "the patient was randomised into the treatment or control group" Quote: "These had been prepared from random number tables" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "a double‐blind protocol" SCD not likely affected |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | SCD not likely affected |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Analysis has been on the 'intention to treat' basis" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Quote: "All deaths and major recordable events were entered with full details on special forms" |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

DIABHYCAR 2004.

| Methods | Multi‐centre randomised double‐blind parallel‐group Trial conducted in Europe and North Africa |

|

| Participants | Patients with type 2 diabetes > 50 years of age who use oral antidiabetic drugs and have persistent microalbuminuria or proteinuria and serum creatinine < 150 µmol/L | |

| Interventions | Ramipril (1.25 mg/d) vs placebo (on top of usual treatment) | |

| Outcomes | Total mortality Cardiovascular death Myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure leading to hospital admission, end‐stage renal failure, sudden death Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | SCD unlikely affected |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | High risk | |

EWPHBPE 1985.

| Methods | Double‐blind randomised placebo‐controlled Trial conducted in Europe |

|

| Participants | Elderly patients (mean age 72 years, range > 60 years) Male 30%. Ethnicity not reported Baseline SBP/DBP 183/101 mmHg; pulse pressure 82 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP 160 to 239 mmHg and DBP 90 to 119 mmHg. Participants followed for 7 years |

|

| Interventions | HCTZ/triamterene 25/50 mg 1 to 2 tabs methyldopa 0.5 to 2 g Control: matching placebo |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality: death from any cause Fatal myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease, sudden death, heart failure, stroke Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure |

|

| Notes | Only intention‐to‐treat data included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly allocated to an active treatment or placebo treatment group" Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Patients remained in the double‐blind part of the trial until the summer of 1984" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Data were sent to the coordinating office every three months on specially designed forms, and deaths and other terminating events were classified independently by two investigators into previously agreed categories. These investigators were not aware of the treatment group to which patients had been assigned" Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two analyses: per‐protocol analysis and Intention‐to‐treat analysis. "After leaving the double‐blind part of the trial, the surviving patients were followed up until July 1984, but only date and cause of death were recorded" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SCD reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

HSCGS 1974.

| Methods | Prospective double‐blind randomised placebo‐controlled Trial conducted in USA |

|

| Participants | Ambulatory patients, stroke survivors, 80% African Americans, mean age 59 years (range < 75 years). Male 60% Baseline SBP/DBP 167/100 mmHg; pulse pressure 67 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP ≥ 140 to 220 mmHg, DBP 90 to 115 mmHg Participants followed for 3 years |

|

| Interventions | Methyclothiazide 10 mg + deserpidine 1 mg. Control placebo | |

| Outcomes | Total mortality Stroke, sudden death, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The biostatistical section was responsible for assignment of patients to drug or placebo regimens, distribution of medication by mail to the individual clinics, data preparation, coding, and analysis" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not described but low risk for SCD |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not described but low risk for SCD |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Sudden cardiac death reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

MRC‐TMH 1985.

| Methods | Randomised single‐blind comparison of 2 treatments and placebo Trial conducted in UK |

|

| Participants | Ambulatory young patients. Mean age 52 years (range 35 to 64 years). Ethnicity not reported. Male 52%. Baseline mean SBP/DBP 161.4/98.2 mmHg. Pulse pressure 63 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP < 200 mmHg and DBP 90 to 109 mmHg Participants followed for 5 years |

|

| Interventions | Bendrofluazide 10 mg daily (71% mono), propranolol 80 to 240 mg daily (78% mono), methyldopa added if required | |

| Outcomes | Total mortality Stroke, myocardial infarction Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly allocated at entry" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "single‐blind" Comment: low risk for SCD |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The evidence on which the diagnosis of each terminating event was based was assessed by an arbitrator ignorant of the treatment regimen" Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "All analyses presented here are based on randomised treatment ('intention to treat') categories" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SCD reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

MRC‐TMH 1985 Betablocker arm.

| Methods | See above | |

| Participants | See above | |

| Interventions | See above | |

| Outcomes | See above | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See above |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | See above |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | See above |

| Other bias | Low risk | See above |

MRC‐TMH 1985 Diuretic arm.

| Methods | See above | |

| Participants | See above | |

| Interventions | See above | |

| Outcomes | See above | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See above |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | See above |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | See above |

| Other bias | Low risk | See above |

OSLO 1986.

| Methods | Randomized controlled group Trial conducted in Norway | |

| Participants | Ambulatory young male patients. Mean age 45.3 years (range 40 to 49 years). Ethnicity not reported Baseline mean SBP/DBP 156.2/97 mmHg; pulse pressure 59 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP 150 to 179 mmHg and DBP < 110 mmHg Participants followed for 5 to 6 years |

|

| Interventions | Hydrochlorothiazide (95%), methyldopa and propranolol (26%) At 5‐year follow‐up, 36.7% were taking HCTZ alone, 26% HCTZ + propranolol, 20% HCTZ + methyldopa and 18% other drugs |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality Sudden death, myocardial infarction, stroke Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The drugs were administered in a randomised manner" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Low risk for SCD |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Low risk for SCD |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

SHEP 1991.

| Methods | Multi‐centre randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled Trial conducted in USA |

|

| Participants | Ambulatory patients. Mean age 72 years (range > 60 years) 13.9% of participants were African Americans. Male 43% Baseline mean SBP/DBP 170/77 mmHg; pulse pressure 93 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP 160 to 219 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg Participants followed for 4.5 years |

|

| Interventions | Chlorthalidone 12.5 to 25 mg (69%) Step 2: atenolol 25 to 50 mg (23%) or reserpine 0.05 to 0.1 mg Identical placebo |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality Stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death Quality of life measures Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Screenees were randomly allocated by the coordination center to one of two treatment group[s]" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was stratified by clinical center and by anti‐hypertensive medication status at initial contact" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Participants were randomized in a double‐bind manner" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Information related to study end points was collected by clinic staff... Occurrence of study events listed above was confirmed by a coding panel of three physicians blind to randomization allocation" Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Low risk for SCD |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Low risk for SCD |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not Industry funded |

SHEP‐Pilot 1989.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled Trial conducted in USA | |

| Participants | Ambulatory patients. Mean age 72 years (range > 60 years) 18% of participants were non‐white. Male 37% Baseline mean SBP/DBP 170/77 mmHg; pulse pressure 93 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP 160 to 219 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg Participants followed for 3 years |

|

| Interventions | Chlorthalidone 25 to 50 mg daily (87%) Step II randomised to hydralazine, reserpine or metoprolol (13%) Control: placebo |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality Stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Participants were randomly assigned in a double‐blind [fashion]" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The ratio of assignment was 4:1 to permit the expected comparison among Step II medications" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Working independently and without knowledge of the participant's treatment group assignment, each member made a diagnosis based on the criteria table" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Analysis was by intention to treat" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The diagnosis of "no event" was also acceptable and was the final diagnosis for five suspected morbid events" |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

STOP 1991.

| Methods | Prospective randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled intervention study Trial conducted in Sweden |

|

| Participants | Hypertensive men and women 70 to 84 years of age | |

| Interventions | Treatment consisted of atenolol 50 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg + amiloride 2.5 mg, metoprolol 100 mg or pindolol 5 mg. Control placebo | |

| Outcomes | Total mortality Stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly allocated" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind administration of active hypertension therapy or placebo" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Endpoints were evaluated by an independent endpoint committee, unaware of treatment given or blood pressure" Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "77% of the placebo group and 84% of the actively treated group were still taking the study medication. In the analysis, the intention‐to‐treat principle was used" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Low risk for SCD |

| Other bias | Low risk | Not industry funded |

SYST‐EUR 1997.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled Trial conducted in Europe |

|

| Participants | Ambulatory patients, with mean age 70.2 (range > 60) years Male 31%. Ethnicity not reported Baseline mean SBP/DBP 174/85.5 mmHg; pulse pressure 89 mmHg Inclusion criteria: SBP 160 to 219 mmHg and DBP < 95 mmHg Participants followed for 2.5 years |

|

| Interventions | Nitrendipine 10 mg daily, 10 mg BID, 20 mg BID; enalapril 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg daily in the evening; HCTZ 12.5 mg, 25 mg daily in the morning Matched placebos |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality Myocardial infarction, stroke, sudden death Systolic BP and diastolic BP |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "After stratification by centre, sex, and previous cardiovascular complications, we randomly assigned" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate Quote: "by means of computerised random function" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind" Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "The endpoint committee, which was unaware of the patients' treatment status, identified all major endpoints by reviewing the patients' files and other source documents" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The data were analysed by intention to treat with two‐sided test" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Other bias | High risk | Industry funding |

UKPDS38 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled open‐label Trial conducted in UK | |