Abstract

Introduction

Tobacco product retailers provide access to tobacco products and exposure to tobacco marketing. Without a national tobacco retailer licensing system in the United States, there are no estimates of national trends in tobacco retailer numbers and store type over time.

Methods

We developed a protocol to identify likely tobacco retailers across the United States between 2000 and 2017 using industry codes and retailer names in the annual National Establishment Time Series (NETS) database. We calculated annual counts of tobacco retailers in seven store-type categories and annual numbers of tobacco retailers that opened and closed.

Results

We estimate that there were 317 492 tobacco product retailers in 2000; the number grew to 412 536 in 2009 before falling to 356 074 in 2017, for a net 12% increase overall. Gas/convenience stores and grocery stores accounted for more than two thirds of all retailers. On average, new openings accounted for 8.0% of the total retailers, whereas 7.3% of retailers closed or stopped selling tobacco each year, with stronger market volatility following the Great Recession. Since 2011, there was a disproportionate reduction in tobacco-selling pharmacies and an increase in both tobacco-specialty shops and tobacco-selling discount stores.

Conclusions

During two decades when smoking declined, tobacco retailer availability increased in the United States. The economic climate, corporate and public policies, and new tobacco products may all contribute to trends in tobacco retailer availability. State and local jurisdictions considering tobacco retailer policies may find retailer trend information useful for forecasting or evaluating potential policy impacts.

Implications

This study provides historic data tracking tobacco retailers in the United States between 2000 and 2017, documenting trends that unfolded as the general economic market contracted and grew, with greater regulation of the tobacco retailer environment. These data provide a context for better understanding future changes in the tobacco retailer market. In addition, the protocol established in this study could be applied in any US-based location without tobacco retailer licensing to allow identification of stores and tracking of trends.

Introduction

The Tobacco Control Vaccine, which includes four evidence-based components that reduce smoking (eg, tobacco product price increases, smoke-free policies), has now been amended to include policies focused on the tobacco retail environment.1,2 A greater number of tobacco product retailers and higher amounts of tobacco marketing in a geographic area are associated with greater smoking and relapse behaviors3–7 and health outcomes like pulmonary disease.8–10 Given concern over the adverse impacts of higher tobacco retailer density, several US cities and states have implemented public policies designed to restrict tobacco retail availability, such as bans on tobacco sales in pharmacies (eg, Massachusetts), caps on the number of tobacco retailers (eg, San Francisco), or limits on new retailers near schools (eg, Philadelphia).11

Understanding the potential impact of these and other policies designed to reduce tobacco retailer availability requires an understanding of the general variation in tobacco product retailers over time. Very few studies have tracked the tobacco retailer environment over time, and those that have are limited to individual cities or regions or specific store types. For example, Hosler et al. examined 12-year trends in tobacco availability in food stores in Albany, NY, between 2003 and 2015, finding a peak in percent of stores selling tobacco in 2009.1 Hall et al. documented a growth in tobacco-selling general goods discount stores in the Southeastern United States that coincided with a reduction in tobacco-selling pharmacies between 2012 and 2014.12

There is no national licensing system for tobacco product retailers in the United States, making it difficult to analyze the changes to the number and composition of tobacco retailers. Although 38 states and multiple cities do have licensing systems, the process and timing of updating those systems differ widely. Licensing systems differ in products licensed, fees, penalties, and renewal time periods, making comparisons across places challenging.13,14 Although the federal government requires regular checks of tobacco retailers for compliance with tobacco-related regulations (eg, bans on cigarette sales to minors), they contract with individual states or other entities to do so,15 resulting in multiple, varied systems. States are only required to audit a sample of stores each year,15 and only store names that receive an audit are made public.16

In the absence of national tobacco retailer data, several studies have instead identified likely tobacco product retailers using national business lists and industry codes. Two studies suggest this general approach to identifying tobacco outlets is valid when compared to a licensing list in Washington State,17 and a list of “ground-truthed” stores confirmed through store visits in three counties in North Carolina.18 The precise methods of identifying retailers, such as inclusion of certain store types and exclusion of certain company names, vary. Furthermore, existing studies are cross-sectional, so the tobacco retailer identification protocol used cannot be used to analyze how the tobacco retail environment has changed over time in the wake of periods of economic growth and contraction, or changes in tobacco retailer-related policies.

The purpose of our study is to estimate annual measures of the number of tobacco product retailers in the United States between 2000 and 2017, the number of new tobacco retailers established each year, and the number of stores that go out of business or stop selling tobacco. By decomposing the trends over the time period into different store types, we can also observe if some store types experienced stronger growth or decline than others in different time windows. Understanding how different types of retailers grow over time, and in a national context, is important for understanding potential changes in consumer exposure to a range of tobacco products.

Methods

This research was conducted as part of a national study conducted by Advancing Science and Practice in the Retail Environment (ASPiRE), a consortium of researchers from the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis, the Stanford Prevention Research Center, and the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.

We developed a protocol to identify likely tobacco product retailers across the United States based on store types (primary business function) and retailer names. Our protocol has four major steps:

Include all retailers in store type categories where tobacco selling occurs frequently;

Remove retailers known or presumed not to, or prohibited from, selling tobacco;

Add retailers from store types not already listed that are known or presumed to be tobacco retailers; and

Remove duplicate stores and corporate offices.

Details of these steps and the final store type categories used in our analyses are described below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tobacco Retailer List Store Type Categories, With Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Store type | NAICS code | Inclusions and exclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Gas stations and/or convenience stores | 447110, 445120, and 447190 | Exclude: Marine service stations (SIC: 55419902) |

| Supermarkets and grocery stores | 445110 | Exclude: Aldi’s, Trader Joes, Whole Foods, Wegmans (2009+), Raleys (CA only, 2016+), Schwans Home Service, Fresh and Easy Neighborhood Market, The Fresh Market, Sprouts |

| Exclude SIC codes: coops (54119901), delis (54119902), frozen foods (54119903) | ||

| Alcohol stores | 445310 | ExcludE: state-run liquor and wine stores that do not permit tobacco product sales. |

| Pharmacies | 446110 | Include: Walgreens, Rite Aid, Kmart Pharmacies, Eckerd, Longs Drug Stores, New Albertsons, American Drug Stores, Bond Drug Company, Duane Reade, Thrifty Payless Inc, Hook SuperX, Kerr Drug, Arbor Drug, CVS (until 2014) |

| Exclude: pharmacies in locations/years with pharmacy tobacco sales bans in effect. | ||

| Tobacco/smoke shops | 453991 | Exclude: Marijuana stores (SIC: 59939905) |

| Add: “tobacco” “cigarette” and “vap*” store titles in SIC: 53*-59* (various retailer categories), 70* (hotels), 78* (motion pictures), and 79* (recreation) | ||

| Other general merchandisers, discount department stores | 452319, 452210, and 452112 | Include: Walmart, Kmart, Meijer, Shopko, 99 cents stores, Family Dollar (as of 2013), Dolgencorp/Dollar General (as of 2014), military exchanges |

| Warehouse stores and supercenters | 452311 | Include all |

NAICS = North American Industry Classification System; SIC = Standard Industrialized Classification.

We applied the protocol to the annual National Establishment Time Series (NETS) database between 2000 and 2017. NETS is a longitudinal database developed by Walls & Associates that contains archival establishment data from Dun and Bradstreet.19 NETS retailers self-identify their retailer store types using Standard Industrialized Classification (SIC) codes; NETS then matches these with North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes using a crosswalk. Although both NAICS and SIC codes are government-developed systems used to identify business types, we leveraged the NAICS crosswalk and report our results using NAICS codes because they we developed our initial store type inclusion criteria using the US Economic Census, which reports tobacco sales by NAICS code.20 NETS also includes store names, addresses, first and most recent year of business operation, and latitude and longitude information for each retailer. NETS data are considered accurate as of January 1 of the identified year.

Include Retailers Where Tobacco Selling Occurs Regularly

Using the four US Economic Censuses covering our analysis window (2002, 2007, 2012, and 2017), we examined two metrics by NAICS code: (1) the percent of stores in a NAICS code category that sold tobacco, determined by the tobacco product code for cigars, cigarettes, tobacco, and smokers’ accessories and (2) the percent of all retail tobacco sales accounted for by that NAICS code. If, in at least one edition, more than 50% of stores within a NAICS code category sold tobacco, and if that category collectively accounted for at least 2% of tobacco retail sales, we considered that NAICS code a usual tobacco-selling store type and added those store types to our database. Eight NAICS codes met the following criteria: convenience stores that stock limited supplies and are open long hours (445120), gasoline stations that also include convenience stores (447110), tobacco-specific shops (including vape shops) (453991), supermarkets and grocery stores (445110), warehouse clubs and supercenters that sell bulk goods (452311), pharmacies and drug stores (446110), beer/wine/liquor stores (445310), and other general merchandisers (452319). We associated each of these with a separate store type, with two exceptions. After comparing store names listed under the convenience, gas/convenience, and a third NAICS category (other gasoline stores [447190]), and noting that similar store names appeared across all categories, we decided to combine these three NAICS codes into a single gas/convenience category. Additionally, prior to 2017, a small fraction of other general merchandise stores sold tobacco, but this percent jumped to more than 75% that year. Store name analysis suggested that several tobacco retailers previously listed as discount department stores, which sell general goods at reduced prices (NAICS: 452112) were later listed as either other general merchandisers or department stores (NAICS: 452210) in 2017 when the discount department store category was eliminated. To ensure catchment of all such retailers, we merged these three store types and then cleaned the data as described below.

Remove Retailers Unlikely to Sell Tobacco

Several national or local chain stores have corporate policies prohibiting sales of tobacco or have been recognized by tobacco advocacy groups for not carrying tobacco products.21 To identify the most prevalent of these, we identified the 20 most frequently occurring retailer names in each store type category each year, combining similar company names, (eg, Rite Aid of Alabama, Rite Aid of Texas), and then examined websites, company financial forms, news stories, and citations for violating federal tobacco compliance checks to determine their historical tobacco selling status. In the absence of evidence from these strategies that a particular company did not sell tobacco products, we retained it in our data. Examples of excluded stores include Aldi’s, Trader Joes, Whole Foods, and CVS (after 2014). We also analyzed SIC code store categories within each included NAICS code and omitted certain stores that specialized in products other than tobacco: marijuana stores, food cooperatives, delis, frozen food stores, and marine service stations.

State and Local Tobacco Retailer Regulations

Furthermore, some states or localities banned certain types of stores from selling tobacco during our analysis period. For example, multiple cities and counties in New York, Minnesota, Massachusetts, and California, and the state of Massachusetts, passed laws prohibiting pharmacies from selling tobacco. Using data on local pharmacy bans collated by the American Nonsmoker’s Rights Foundation (ANRF) US Tobacco Control Laws Database (TCLD), we identified the years such bans were implemented and excluded pharmacies in the relevant jurisdictions during the years in which the ban was in place. As appropriate, we excluded pharmacies located in unincorporated regions subject to county policies. Because the NETS data are considered accurate as of January 1 of each year, policies implemented in the middle of a year were not reflected until the following year in our data. We followed a similar procedure to exclude state-run alcohol stores in nine states and one county, using factsheets and other resources provided by the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association (NABCA), as well as communication with state beverage control boards.

Tobacco-Selling Pharmacies

The NAICS pharmacy code includes both large-chain pharmacies that sell many products other than pharmaceuticals and small independent pharmacies that may specialize in compounding medicines. Independent and compounding pharmacies may be less likely to sell tobacco products than large-chain pharmacies. We therefore retained only those pharmacies with at least 10 establishments in the NETS data in either 2000 or 2017. As a sensitivity check, we compared our list with one created from pharmacies that were audited in the Food and Drug Association (FDA) tobacco retailer inspection system between 2012 and 2017.21 All names on our list, with the exception of those housed in grocery stores, were also identified on the FDA list.

Discount Department Stores and Other General Merchandisers

The NAICS codes describing discount department stores, other general merchandise stores, and department stores are relatively broad, and the percent of stores selling tobacco in each category varied widely across the time period, likely reflecting movement of stores across the NAICS codes. Rather than including all stores in all three categories, which would likely include many non-tobacco retailers that otherwise sell reduced-price goods, we included only known tobacco retailers using similar procedures to those described above. Examples of added stores known to sell tobacco products included Kmart, Shopko, and, after 2013, Family Dollar.

Add Other Retailers That Likely Sell Tobacco

Examination of the NETS data revealed multiple stores that appeared to be tobacco shops based on their name but were coded in another store type category. We examined a sample of excluded SIC codes and identified 10 SIC codes (eg, miscellaneous retail, amusement, and recreation services) where such store names were most prevalent. Within those SIC codes, we then added any store whose name included the words tobacco, cigarette, or vape/vapor/vaping to the retailer list under the tobacco shop store type.

Remove Duplicate Retailers and Corporate Offices

In 2017, the raw NETS data contained 33 107 addresses with multiple stores, accounting for 8.1% of stores. We reviewed Google streetviews of a selection of these addresses, often verifying the existence of each in multistore strip malls or convenience stops. As a result we did not consider these duplicate stores unless two stores had the same name, address, NAICS code, and time period of operation. However, in each year, there are a small number (~50–150) of addresses in the NETS data that listed seven or more tobacco retailers at a given address. We examined all of the store names at each of these addresses for 1 year. Similarity of store name (eg, multiple with RJ Reynolds in the name) suggested most of these were corporate office locations for manufacturers or chain retailers, rather than stores engaged directly in retail sales to consumers. We therefore removed these from the data. Finally, to correct for possible data errors and ensure we had information to conduct geospatial analyses, we removed stores with a post office box or missing address.

Analysis

The above protocol was implemented using code written by the research team in SAS (9.4, Cary, NC). Additionally, we used ArcMap (Esri, Redlands, CA) to identify pharmacies in unincorporated areas of counties with pharmacy bans. Once our lists were finalized, we calculated annual counts of tobacco product retailers by store type over the 18-year analysis window. From the NETS variables capturing the year a business opened as well as the last year it was in operation, we were able to calculate the annual number of tobacco product stores that opened or closed.

Results

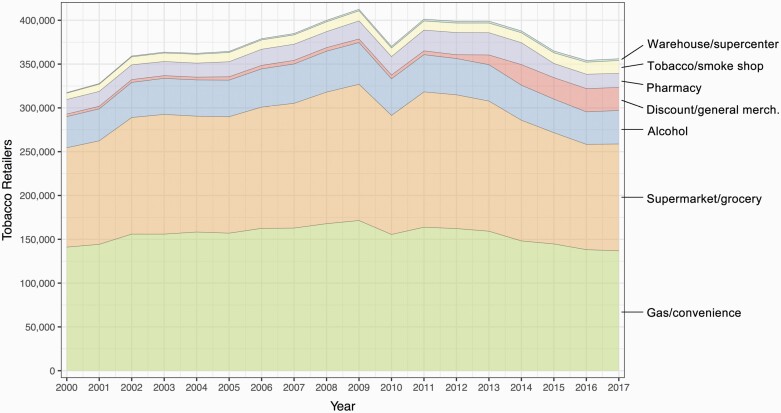

The total number of estimated tobacco product retailers each year between 2000 and 2017, by store type, is presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 1. In each year of this period, there were more than 300 000 likely tobacco retailers in the United States, and in some years, this total surpassed 400 000. Gas/convenience stores and supermarket/grocery stores accounted for the vast majority of tobacco retailers in all time periods, comprising between 38%–44% and 34%–39% of all retailers, respectively. Alcohol stores consistently account for between 10% and 11% of tobacco retailers, with all other store types each comprising less than 1%–8% of the retailer total.

Table 2.

Annual Numbers of Likely Tobacco Retailers by Store Type, United States (2000–2017)

| Store type | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | All tobacco retailers | Gas/convenience | Supermarket/grocery | Alcohol | Pharmacy | Tobacco/smoke shop | Discount/general merchandiser | Warehouse/supercenter |

| 2000 | 317 492 | 141 045 | 113 450 | 35 533 | 16 616 | 7226 | 2918 | 704 |

| 2001 | 327 779 | 144 246 | 118 161 | 36 576 | 16 950 | 8181 | 2980 | 785 |

| 2002 | 359 229 | 155 947 | 133 067 | 40 065 | 16 866 | 9093 | 3214 | 977 |

| 2003 | 363 666 | 155 917 | 136 627 | 41 154 | 16 132 | 9663 | 3125 | 1048 |

| 2004 | 362 286 | 158 288 | 132 241 | 41 351 | 16 006 | 10 111 | 3202 | 1087 |

| 2005 | 364 480 | 156 991 | 132 969 | 41 725 | 17 145 | 10 534 | 3846 | 1270 |

| 2006 | 378 996 | 162 455 | 138 447 | 43 607 | 18 410 | 10 628 | 3998 | 1451 |

| 2007 | 384 870 | 162 814 | 142 409 | 44 901 | 18 429 | 10 647 | 4111 | 1559 |

| 2008 | 399 922 | 167 841 | 150 174 | 46 685 | 18 250 | 11 170 | 4091 | 1711 |

| 2009 | 412 536 | 171 429 | 155 535 | 47 564 | 20 629 | 11 476 | 4141 | 1761 |

| 2010 | 370 191 | 155 543 | 135 860 | 41 826 | 21 012 | 9714 | 4247 | 1899 |

| 2011 | 401 239 | 163 807 | 154 460 | 42 451 | 23 737 | 10 365 | 4354 | 2065 |

| 2012 | 398 909 | 162 253 | 152 679 | 41 379 | 25 281 | 10 793 | 4399 | 2125 |

| 2013 | 399 039 | 159 221 | 148 564 | 41 546 | 25 445 | 10 981 | 11 062 | 2220 |

| 2014 | 387 854 | 148 149 | 137 775 | 39 985 | 24 993 | 11 335 | 23 495 | 2122 |

| 2015 | 364 981 | 144 687 | 127 041 | 38 305 | 16 140 | 12 137 | 24 540 | 2131 |

| 2016 | 354 247 | 138 179 | 120 186 | 37 081 | 16 404 | 13 680 | 26 601 | 2116 |

| 2017 | 356 074 | 136 869 | 121 939 | 38 218 | 16 070 | 14 690 | 26 272 | 2016 |

| % change 2000–2017 | +12.2% | -3.0% | +7.5% | +7.6% | −3.3% | +103.3% | +800.3% | +186.4% |

Figure 1.

Tobacco retailers in the United States by store type (2000–2017).

The number of tobacco retailers grew by 30% from 317 492 in 2000 to 412 536 in 2009, followed by a 14% drop over the next 8 years to 356 074 in 2017, resulting in a net 12% increase over the full time period. This overall trend included a sharp 10% drop in retailers between 2009 and 2010, followed by an 8% increase in retailers the following year.

Descriptive results suggest differences in trends for several store types, compared with the overall pattern observed for all stores combined. Although most store types grew in number over the full study period, there were fewer gas/convenience stores and tobacco-selling pharmacies in 2017 than in 2000. For gas/convenience stores, this is due primarily to a steady decline after 2011; for pharmacies, the steep reduction began later, after 2014. In contrast, growth in tobacco-selling discount stores over the entire time period far outpaced overall tobacco retailer growth, especially in the more recent time period, resulting in eight times as many of these retailers selling tobacco in 2017 than in 2000. In addition, the number of tobacco stores and supercenters increased even in the most recent years, when other types were declining, resulting in a more than doubling of their numbers in the analysis window.

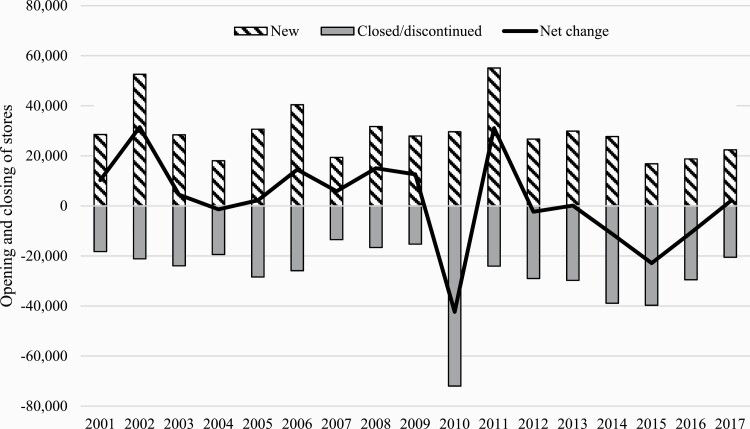

In any given year, new tobacco product retailers enter the market and some tobacco product retailers exit the market, which together form the net change described in Table 2. Annual retailer entrances and exits are illustrated in Figure 2. On average over the time frame, 27 404 retailers closed or stopped selling tobacco each year and 29 673 retailers opened or began selling tobacco; this represents about 7.3% and 8.0% of the total retailers each year, respectively. Retailer entrances and exits, however, varied substantially by year. Years marked by the high numbers of market exits were 2009 (71 949 exits, 19.4% of the tobacco market), 2014 (38 884 exits, 10.0% of the market), and 2015 (39 696 exits, 10.9% of the market). Years marked by high numbers of market entrances were 2001 (52 579 entrances, 14.6% of market), 2005 (40 427 entrances, 10.6% of the market), and 2010 (55 103 entrances, 13.7% of market). Two years in our data (2001 and 2010) were characterized by high retailer “churn” with more than 20% of the market opening or closing during the year.

Figure 2.

Annual likely tobacco retailer market entrances exits and net change, United States (2000–2017).

Discussion

Between 2000 and 2017, tobacco products were readily available to US residents, with an average of 375 664 tobacco product retailers each year. The numbers of tobacco retailers peaked at more than 412 000 in 2009. Although this number dropped precipitously in 2010 following the Great Recession, our analysis indicates that one year later, the market had nearly recovered, with more than 401 000 retailers selling tobacco. Since then, the number of tobacco retailers has steadily declined, resulting in an estimated 356 074 stores selling tobacco in 2017.

During this same time period, current cigarette smoking among US adults declined from 23.3% in 200022 to 14% in 2017,23 and the proportion of ever-smokers who have quit has increased over this time period.24 However, not all population groups experienced this same pattern. Tobacco use remained highest among non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives.22,23 Adults with household incomes below the poverty level and those with less than some college education consistently had higher smoking prevalence.22–24 In addition, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) were introduced to the US market by mid-2000s,25 and sales have more than doubled since 2014.26 As of 2017, 15% of adults27 and 19.6% of high school youth28 had ever used an e-cigarette.

To further understand trends in the number of tobacco retailers, we disaggregated our data by store type. Although the gas/convenience store type category was one of the few store types to experience a net reduction in numbers between 2000 and 2017, it remains the most prevalent type of tobacco retailer in the country, accounting for 38.4% of all retailers averaged across years. Gas/convenience stores are more likely to offer price promotions and contain more tobacco marketing materials than grocery stores, the next most prevalent retailer type (34.2%).29 Given the widespread availability of gas/convenience stores and the marketing of diverse products that occurs there that can cue tobacco purchases, it is not surprising that nearly 70%–80% of adult smokers report usually purchasing their cigarettes at gas/convenience stores.30,31

There were also fewer tobacco-selling pharmacies in 2017 than in 2000. This is unlikely to reflect a reduction of pharmacies in general, as one study found an increase in pharmacies between 2007 and 2015.32 A closer look at our data reveal a decline driven by a more than 35% reduction between 2014 and 2015. In 2014, CVS, the largest dispensing pharmacy by total prescription revenue in the United States,33 announced the phasing out of tobacco sales in its stores by October of that year. In addition, the latter part of our analysis window was characterized by a wave of local bans on pharmacy-based tobacco sales. Between 2009, when San Francisco became the first city to prohibit pharmacies from selling tobacco, and 2017, more than 150 cities or counties implemented similar policies.34 Both national- and state-based store observation data indicate that cigarette prices, a key predictor of tobacco use and consumption,35,36 are lower in pharmacies than in other tobacco retailer types.37 Voluntary and legislated tobacco sales bans may therefore reduce the availability of lower-cost products.

The impact of corporate policies may also be reflected in the growth of tobacco-selling discount stores, which doubled between 2012 and 2013 and again between 2013 and 2014. Two leading dollar stores, Family Dollar and Dollar General, began selling tobacco in the first quarter of 2012 and the second quarter of 2013, respectively.38,39 These two stores, along with Dollar Tree, which did not sell tobacco in our analysis window, grew 62% between 2008 and 2018.38–40 One study based in a single large US state found that cigarette prices in dollar stores were higher than in convenience stores or tobacco-specialty shops, but lower than in supermarkets.41 Although tobacco prices in dollar stores have not been compared with those in other tobacco retailers, the discount store model hinges on offering most products are prices that are lower than those found elsewhere. Furthermore, location studies of dollar stores indicate that tobacco availability in such stores may have disproportionately increased in rural areas, as well as neighborhoods with more Black, Hispanic, and Asian residents.12,40

Another store type experiencing dramatic growth between 2000 and 2017 was the tobacco/smoke specialty shop. This category includes both traditional tobacco retailers and stores that exclusively sell vaping products. Although the store type codes in our data do not distinguish primarily vape shops from other tobacco shops, the mostly steady growth in this store type during the analysis period may in part reflect the emergence and growth of electronic cigarettes Research suggests most tobacco shops also sell vaping products; in New Hampshire 2016 census of tobacco/smoke speciality shops, over 90% of stores sold vapor devices and all retailers sold e-liquids or cartridges.42 State and local laws regulating the sale and marketing of e-cigarettes have grown in the past few years43 and in late-2020 federal legislation banning the sale of tobacco, including electronic cigarettes, to people under the age of 21 was implemented.44 Future tracking of the number of tobacco stores that sell electronic cigarettes can examine whether the upward trends observed in our data continue. In 2016, a new six-digit SIC code (599306) was introduced for electronic cigarette retailers.45 Although this code may not distinguish shops that only sell vape products from other traditional and mixed tobacco retailers entirely, future studies analyzing this could provide more detail about tobacco shop market growth.

Several policies designed to limit tobacco product retailers, like Philadelphia’s 2016 policy capping tobacco retailer permits, rely on the natural winnowing of tobacco retailers through market exit in neighborhoods that exceed the cap. Our analysis suggests that nationwide, a little over 7% of tobacco retailers go out of business or stop selling tobacco each year. In a year with a large economic downturn, this rate was close to 20%. Although tobacco market turnover likely varies across cities, these estimates may help localities set expectations for timelines for reducing the number and density of tobacco retailers.

The data presented here are a historical analysis, and as such, we have no way to verify whether the identified stores sold tobacco. In the absence of a national tobacco licensing system, we developed a protocol that used the same process to identify tobacco retailers throughout the country and over time, that also incorporated variation based on existing legislation or changes in corporate policies. Some cities may have additional “on-premise” tobacco retailers, such as bars, cigar bars, cafes, or restaurants, that are not captured in our data. In addition, we limited our procedures for de-duplication, opting not to remove multiple retailers at one location unless they shared other unique characteristics or were numerous enough to suggest corporate headquarters. We have no evidence to suggest any potential under- or overcounting occurred systematically in certain years, suggesting the trends we describe may remain good estimates.

Unfortunately, there is a lag in the construction of longitudinal NETS data after 2017. As such we are unable to assess more recent trends, including national changes in tobacco retailers following the emergence of COVID-19 and the economic retraction that followed. However, these analyses do present a time trend that includes a previous recessionary period; once 2020 retailer data can be included in the longitudinal data sets, we can examine the extent to which the impact on tobacco retailers mirrors previous downturns.

Despite these limitations, our process may still represent an improvement over previous count estimates based on fewer store type categories and limited adjustments for corporate and local public policies.3,17 Due to the inclusion of some stores in categories with fewer tobacco sales overall, followed by extensive cleaning processes, we may better-quantify tobacco retailer availability. For example, elimination of companies known not to sell tobacco, limiting some store types to only known tobacco retailers, and modifications based on existing legislation limiting tobacco sales in some pharmacies or alcohol outlets resulted in a reduction of estimated annual retailers by between 19% and 23%.

Using the described protocol, we identified the annual number of likely tobacco product retailers in the United States between 2000 and 2017. Tobacco retailer trend information, in general, and by store type, can inform the development and evaluation of state and local tobacco retailer policies. Furthermore, identifying tobacco retailers in a community is important for other reasons as well, including the enforcement of tobacco control laws banning certain products or sales to underage youth, and the collection of data about tobacco product marketing and prices, both known risk factors for tobacco use. In places without tobacco retailer licensing systems designed to explicitly identify stores permitted to sell tobacco, this protocol could be used by state or local communities to estimate and track the tobacco retail environment.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award numbers: P01CA225597, T32CA128582). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funders or the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Data Availability

Data available at https://aspirecenter.org/netsretailerscode/.

References

- 1. Hosler AS, Done DH, Michaels IH, Guarasi DC, Kammer JR. Longitudinal trends in tobacco availability, tobacco advertising, and ownership changes of food stores, Albany, New York, 2003–2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:160002. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kong AY, King BA. Boosting the tobacco control vaccine: recognizing the role of the retail environment in addressing tobacco use and disparities. Tob Control. 2020;1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Golden SD, Kuo T-M, Kong AY, Baggett CD, Henriksen L, Ribisl KM. County-level associations between tobacco retailer density and smoking prevalence in the USA, 2012. Prev Med Rep. 2019;17:101005. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.101005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valiente R, Escobar F, Urtasun M, Franco M, Shortt NK, Sureda X. Tobacco retail environment and smoking: a systematic review of geographic exposure measures and implications for future studies. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2020;23(8):1263–1273. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nuyts PAW, Davies LEM, Kunst AE, Kuipers MAG. The association between tobacco outlet density and smoking among young people: a systematic methodological review. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2019;23(2):239–248. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marsh L, Vaneckova P, Robertson L, et al. Association between density and proximity of tobacco retail outlets with smoking: a systematic review of youth studies. Health Place. 2021;67:102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finan LJ, Lipperman-Kreda S, Abadi M, et al. Tobacco outlet density and adolescents’ cigarette smoking: a meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipton R, Banerjee A, Dowling KC, Treno AJ. The geography of COPD hospitalization in California. COPD. 2005;2(4):435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galiatsatos P, Kineza C, Hwang S, et al. Neighbourhood characteristics and health outcomes: evaluating the association between socioeconomic status, tobacco store density and health outcomes in Baltimore City. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e19–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kong AY, Baggett CD, Gottfredson NC, Ribisl KM, Delamater PL, Golden SD. Associations of tobacco retailer availability with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related hospital outcomes, United States, 2014. Health Place. 2021;67:102464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ackerman A, Etow A, Bartel S, Ribisl KM. Reducing the density and number of tobacco retailers: policy solutions and legal issues. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(2):133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall J, Cho HD, Maldonado-Molina M, George TJ Jr, Shenkman EA, Salloum RG. Rural-urban disparities in tobacco retail access in the southeastern United States: CVS vs. the dollar stores. Prev Med Rep. 2019;15:100935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) . 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/licensure/Licensure.html. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- 14. American Heart Association. Tobacco Retail Licensure . https://tobaccoretaillicensure.heart.org/. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- 15. US Food & Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. Compliance and Enforcement Report . FDA; 2013. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/compliance-enforcement-training/compliance-and-enforcement-report. Accessed June 17, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Food & Drug Administration C for T. CTP Compliance & Enforcement . FDA; 2020. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/compliance-enforcement-training/ctp-compliance-enforcement. Accessed June 17, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rodriguez D, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Berke EM, Sargent JD. Predictors of tobacco outlet density nationwide: a geographic analysis. Tob Control. 2013;22(5):349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Angelo H, Fleischhacker S, Rose SW, Ribisl KM. Field validation of secondary data sources for enumerating retail tobacco outlets in a state without tobacco outlet licensing. Health Place. 2014;28:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walls & Associate. National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) Database. Denver, CO: Walls; 2019. https://maryannfeldman.web.unc.edu/data-sources/longitudinal-databases/national-establishment-time-series-nets. Accessed August 6, 2021.

- 20. Henneberry B. SIC Codes vs. NAICS Codes – What’s the Difference?https://www.thomasnet.com/articles/other/sic-codes-vs-naics-codes-what-s-the-difference. Accessed May 20, 2021.

- 21. Lee JGL, Schleicher NC, Leas EC, Henriksen L. US Food and Drug Administration inspection of tobacco sales to minors at top pharmacies, 2012–2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1089–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation idicators among adults – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013–1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang TW. Tobacco product use among adults – United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225–1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan C, Neff LJ. Tobacco Product use among adults – United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736–1742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Introduction, Conclusions, and Historical Background Relative to E-Cigarettes . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538684/ Accessed May 27, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ali FRM. E-cigarette unit sales, by product and flavor type – United States, 2014–2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 2020;69(37):1313–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Villarroel M, Cha A, Vahratian A. Electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults, 2018. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db365.htm. Accessed April 4, 2021. [PubMed]

- 28. Wang TW. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629–633. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ribisl KM, D’Angelo H, Feld AL, et al. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: results of a national study. Prev Med. 2017;105:381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Groom AL, Cruz-Cano R, Mead EL, et al. Tobacco point-of-sale influence on U.S. adult smokers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(1):249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kruger J, Jama A, Lee JGL, et al. Point-of-sale cigarette purchase patterns among U.S. adult smokers – National Adult Tobacco Survey, 2012-2014. Prev Med. 2017;101:38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qato DM, Zenk S, Wilder J, Harrington R, Gaskin D, Alexander GC. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007–2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fein AJ. The 2020 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Drug Channels Institute; 2020:374. https://drugchannelsinstitute.com/products/industry_report/pharmacy/. Accessed September 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. CounterTobacco.org. Tobacco Free Pharmacies . https://countertobacco.org/policy/tobacco-free-pharmacies/. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- 35. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco Use: Interventions to Increase the Unit Price for Tobacco Products . 2012. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/tobacco-use-interventions-increase-unit-price-tobacco. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 36. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/. Accessed September 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Barker DC, Liu Y, Chaloupka FJ. Prices for tobacco and nontobacco products in pharmacies versus other stores: results from retail marketing surveillance in California and in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1858–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maxfield J. Cigarette Sales Are Soaring at Dollar General, Showing Why Retailers Are Addicted to Tobacco. The Motley Fool; 2014. https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/03/18/cigarette-sales-are-soaring-at-dollar-general-show.aspx. Accessed September 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thau B. Dollar chains tap smokes, booze to drive sales, fight Wal-Mart’s small-format stores. Forbes. 2012. https://www.forbes.com/sites/barbarathau/2012/11/06/dollar-chains-tap-smokes-booze-to-drive-sales-fight-wal-marts-small-format-stores/. Accessed September 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shannon J. Dollar stores, retailer redlining, and the metropolitan geographies of precarious consumption. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2020;111(4): 1–19. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1775544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henriksen L, Andersen-Rodgers E, Zhang X, et al. Neighborhood variation in the price of cheap tobacco products in California: results from healthy stores for a healthy community. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(11):1330–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kong AY, Eaddy JL, Morrison SL, Asbury D, Lindell KM, Ribisl KM. Using the Vape Shop Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (V-STARS) to assess product availability, price promotions, and messaging in New Hampshire vape shop retailers. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. E-Cigarettes . https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/e-cigarettes. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- 44. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) . FDA. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/laws-enforced-fda/federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-fdc-act. Accessed September 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee JGL, D’Angelo H, Kuteh JD, Martin RJ. Identification of vape shops in two North Carolina Counties: an approach for states without retailer licensing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1050. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available at https://aspirecenter.org/netsretailerscode/.