Abstract

Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum (viremia) of COVID-19 patients has been related to poor prognosis and death. The aim of this study was to evaluate both the ability to detect viremia in COVID-19 patients of two commercial reverse real-time-PCR (rRT-PCR) tests, Cobas® and TaqPath™, comparing them with a gold standard method, and their implementation in microbiology laboratories.

This retrospective cohort study included 303 adult patients (203 diagnosed with COVID-19 and 100 non-COVID-19 patients) admitted to a tertiary hospital, with at least one serum sample collected within the first 48 h from admission. A total of 365 serum samples were included: 100 from non-COVID patients (pre-pandemic and pandemic control groups) and 265 from COVID-19 patients. Serum samples were considered positive when at least one target was detected. All patients in control groups showed negative viremia. Cobas® and TaqPath™ tests showed specificity and Positive Predictive Value over 96%. Nevertheless, sensitivity (53.72 and 73.63, respectively) and Negative Predictive Value (64.78 and 75) were lower. Viremia difference between ICU and non-ICU patients was significant (p ≤ 0.001) for both techniques.

Consequently, SARS-CoV-2 viremia detection by both rRT-PCR tests should be considered a good tool to stratify COVID-19 patients and could be implemented in microbiology laboratories.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RNA, Serum, rRT-PCR, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is characterized by a severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by a new type of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). This novel coronavirus was first described on December 2019 in the city of Wuhan, China (Cheng and Shan, 2020). As of November first 2020, more than one million deaths had been reported worldwide (WHO, 2020a).

Patients with COVID-19 may develop mild, moderate or severe symptoms such as severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or multiple organ failure (Chen et al., 2020). To reduce the number of people who may end up suffering from these severe symptoms, it is important to improve diagnosis and, above all, to find tools that help us predict which patients will have a worse clinical outcome. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the samples most commonly used for diagnosis have been those obtained from the respiratory tract. Lately, patient's serum has been proposed as another type of sample to consider for diagnosis, since the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum (called viremia in this study) is related to unfavorable clinical outcomes and multi-organ damage (Eberhardt et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). This was also observed in a study in 2004, in which 75% of the studied patients presented SARS-CoV RNA in blood samples (Chen et al., 2004).

The most common tool to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA is real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). This technique is highly sensitive, especially if it targets more than two regions (Ji et al., 2020). Although most rRT-PCR tests are performed in respiratory tract samples, the genetic material of this novel coronavirus can be detected in other samples such as serum, peripheral blood, feces and samples from other anatomical locations (Zhang et al., 2020). Although the performance of rRT-PCR is well studied for respiratory tract samples, is less studied for other kinds of samples such as serum. Therefore, it is important to carry out comparative studies of the different available RT-PCR techniques to determine their capacity to detect SARS-CoV-2 viremia.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability to assess SARS-CoV-2 viremia of two commercial rRT-PCR assays (cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Test, Roche Diagnostics, USA and TaqPath™ COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) used in daily routine practice for COVID-19 diagnosis, as well as their implementation in a microbiology laboratory.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Patients and samples

This retrospective cohort study was conducted with 303 adult patients admitted to La Princesa University Hospital, a tertiary level hospital in Madrid (Spain). Fifty patients admitted to the hospital during November 2019 with respiratory symptoms were considered the pre-pandemic control group (median age 73.5 years [interquartile range, IQR 62.5–85.5] and 50 % male). Two hundred fifty-three patients were admitted to the hospital between March 1st and May 31th with at least one serum sample collected within the first 48 h from admission. Fifty out of these 253 patients had negative COVID-19 PCR results in nasopharyngeal swabs, and they were considered the pandemic control group (median age 69 years [IQR 62–83] and 64 % male). The remaining 203 patients (median age 64 years [IQR 56–72] and 68.5 % male) had SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed by a positive PCR on a nasopharyngeal swab sample. These patients were considered the COVID-19 group. Eighty-nine of them (median age 65 years [IQR 69–72] and 71.3 % male) were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), while 114 (median age 64 years [IQR 54.3–72] and 66.4 % male) were admitted to the general ward.

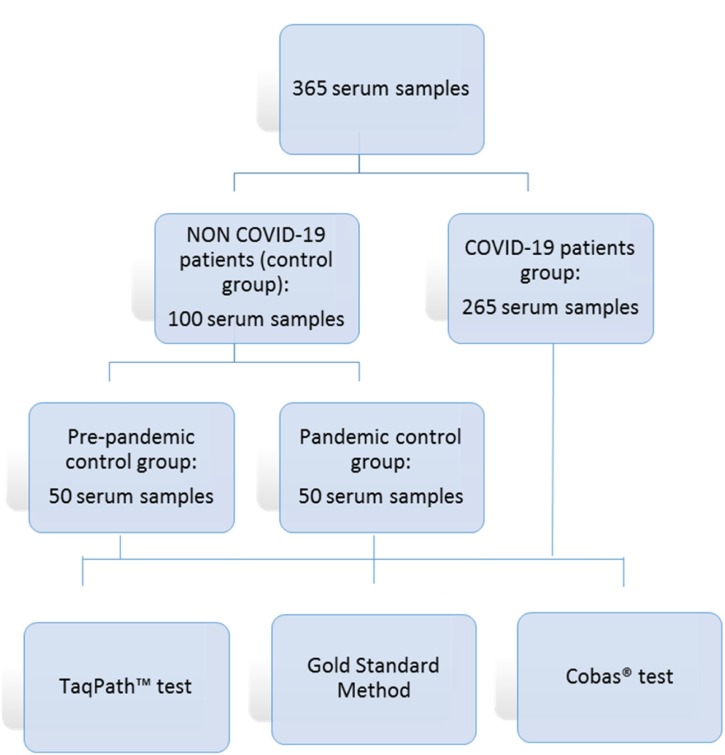

Serum samples were collected through routine clinical practice. Additional serum samples were collected from several patients (50) during their hospital admission as part of their routine management. A total of 365 serum samples were included in this study: 50 serum samples from the pre-pandemic control group, 50 from the pandemic control group and 265 from the COVID-19 group (Fig. 1 ). All samples were stored at -20 °C until they were tested.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of serum samples.

2.2. Study Ddesign

Serum samples were tested with two rRT-PCR assays: cobas® SARS-CoV-2 test (cobas® test), a qualitative assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA; and TaqPath™ COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit (TaqPath™ test), a multiplex RT-PCR assay for qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids. Both are used for routine detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab samples at our hospital.

Results obtained by both techniques were compared with results obtained by Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nucleic Acid Diagnostic Kit (Sansure Biotech Inc., China), a multiplex PCR test for qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids. This technique was used as the gold standard method because it has CE (European Conformity In Vitro Device) and FDA (Food and Drug Administration) authorizations for use in blood samples. Sansure Biotech reported a positive agreement for the test of 94.34 % (95 % CI: 84.34 % ∼ 98.82 %), and a negative agreement of 98.96 % (95 % CI: 96.31 % ∼ 99.87 %), in a clinical evaluation performed for the Submission to FDA EUA (Emergency Use Authorization) (Sansure Biotech Inc., 2020).

The analysis was performed only once for each molecular method because sample volumes were limited.

2.3. Sample processing

Test assays with all the three rRT-PCR methods were carried out using 400 μl of serum, previously treated for virus inactivation with lysis buffer.

2.3.1. Cobas® test

This assay detects a fragment of the SARS-CoV-2 specific orf-1ab region, and a conserved region of the structural envelope e gene, for pan-sarbecovirus detection. Test was performed by cobas® 6800 System (Roche Diagnostics, USA), an automatic platform for nucleic acid extraction and RT-PCR amplification and detection. An initial volume of 400 μl of serum, inactivated with 400 μl of lysis reagent, was processed according to manufacturer’s indications, following the same protocol used for SARS-CoV-2 detection in respiratory samples. Results were analyzed and interpreted automatically by the cobas® 6800/8800 Software version 1.02.12.1002.

2.3.2. Nucleic acid extraction for TaqPath™ and gold standard method

A previous nucleic acid extraction from 400 μl of serum, inactivated with 400 μl of NUCLISENS® easyMAG® Lysis Buffer (Biomérieux), was performed by the automatic eMAG® Nucleic Acid Extraction System (Biomerieux, France) according to manufacturer’s indications, obtaining purified RNA in 60 μl of elution buffer. This eluate was used for SARS-CoV-2 detection by both TaqPath™ test and Gold Standard Method.

2.3.3. TaqPath™ test

TaqPath™ test detects three specific SARS-CoV-2 genomic regions (orf-1ab, s, and n genes) and it was carried out using 5 μl of purified RNA.

rRT-PCR was performed by QuantStudio™ 5 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). Amplification curves were analyzed with QuantStudio™ Design and Analysis software version 2.4.3 (Applied Biosystems, USA). Results were interpreted by a clinical microbiologist, by means of amplification curve analysis, considering the following criteria for positive target detection: a) a Cycle threshold (Ct) cut-off value of 40; b) curves with typical S-shape or without plateau. Positive and negative controls were added in each run.

2.3.4. Gold standard method test

This test detects two specific regions of SARS-CoV-2 genome, orf-1ab and n genes, including detection of internal standard gene fragments (RNase P). Nucleic acid amplification was performed according to the kit manufacturer’s indications. Briefly, 10 μl of purified RNA were added to 15 μl of master mix, with a final PCR volume of 25 μl. rRT-PCR was performed by QuantStudio™ 5 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The PCR protocol consisted of the following steps: 1) 30 min at 50 °C for reverse transcription; 2) 1 min at 95 °C for cDNA pre-denaturation; 3) 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C for denaturation, followed by 30 s at 60 °C for annealing, extension and fluorescence collection; and 4) 10 s at 25 °C for device cooling.

Results were analyzed with QuantStudio™ Design and Analysis software version 2.4.3 (Applied Biosystems, USA). Results were interpreted by a clinical microbiologist considering as a positive result the amplification of at least one of the SARS-CoV-2 genes with a Ct value under 40. Positive and negative controls were added in each run.

2.4. Analysis of results

Detection of at least one target was considered as a positive result.

Evaluation of viremia in patients was carried out considering only the results obtained from their first serum sample.

Results obtained from all 365 collected samples were analyzed for assessment of the techniques.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Continuous and categorical variables were presented as median (IQR) and n (%), respectively. To analyze differences between detection of viremia by each technique, according to whether patients were admitted to ICU or not, a χ2 test was performed. Ct values of all detected targets were recorded for all samples and their median, IQR and 95th percentile were calculated. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and Cohen’s Kappa coefficient were calculated for cobas® test and TaqPath™ test, in comparison with the gold standard method.

3. Results

3.1. Viremia detection in patients

Viremia detection in patients of the COVID-19 group showed the following results: The cobas® test detected viremia in 50.2 % of included patients, showing 65.2 % and 38.6 % positive viremia detection for ICU and non-ICU admitted patients, respectively. The TaqPath™ test detected viremia in 62.6 % of all included patients, with viremia detection in 75.3 % of patients admitted to ICU, and in 52.6 % of those patients who did not require ICU admission. For both techniques, differences of viremia detection between the ICU and non-ICU patients were significant (p ≤ 0.001). Results are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Viremia detection by the two evaluated techniques in patients of the COVID-19 group admitted to ICU or to general ward.

| Ward (%) | ICU (%) | Total | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobas® SARS-CoV-2 | Negative | 70 (61.4) | 31 (34.8) | 101 (49.8) | |

| Positive | 44 (38.6) | 58 (65.2) | 102 (50.2) | 0.0002 | |

| Total | 114 | 89 | 203 | ||

| TaqPath™ COVID-19 | Negative | 54 (47.4) | 22 (24.7) | 76 (37.4%) | |

| Positive | 60 (52.6) | 67 (75.3) | 127 (62.6) | 0.001 | |

| Total | 114 | 89 | 203 |

p value calculated by χ2 test.

Furthermore, the gold standard assay was able to detect presence of SARS-Cov-2 RNA in 80.8 % of patients, with the following distribution: 85.4 % and 77.2 % for ICU and non-ICU patients, respectively. No significant differences were found between both groups (p = 0.14). Viremia was not detected by any of the three techniques in any of the patients of the control groups.

3.2. Assessment of serum samples

A total of 365 serum samples of patients from the pre-pandemic and pandemic control groups (N = 100) and the COVID-19 group (N = 265) were analyzed by both rRT-PCR methods: cobas® test and TaqPath™ test.

Both control groups showed negative results for all serum samples analyzed with cobas® test, TaqPath™ test and the gold standard method.

Comparison between cobas® test and the gold standard method showed a concordance of 75.07 % and a kappa coefficient of 0.52, while comparison of TaqPath™ test showed a concordance of 84.11 %, and a kappa value of 0.69. Results of sensitivity, specificity as well as positive and negative predictive values for both techniques are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Comparison of cobas® and TaqPath™ tests with the gold standard method.

| Assay | Value (%) | 95 % CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobas® test | Sensitivity | 56.72 | 49.62 | 63.81 |

| Specificity | 97.6 | 95.2 | 100 | |

| Positive predictive value | 96.61 | 92.92 | 100 | |

| Negative predictive value | 64.78 | 63.5 | 66.46 | |

| TaqPath™ Test | Sensitivity | 73.63 | 67.29 | 79.97 |

| Specificity | 96.95 | 94.32 | 99.58 | |

| Positive predictive value | 96.73 | 93.59 | 99.88 | |

| Negative predictive value | 75 | 73.21 | 76.79 | |

*CI: confidence interval.

Median Ct values for all targets detected by cobas® test were: 36.2 (IQR 34.2–37.1) for e gene, and 32.7 (IQR 32.1–34.1) for orf1ab gene, while 95th percentiles were 38.72 and 35.21 for e and orf1ab genes, respectively. On the other hand, median Ct values for all targets detected by TaqPath™ test were 31.91 (IQR 29.92–33.27), 32.46 (30.65–34.31) and 31.81 (30.01−32.92) for s, n and orf1ab genes, respectively, and 95th percentiles were 36.91, 37.17 and 37.04 for s, n and orf1ab genes, respectively. Table 3 shows the concordance of positive and negative results obtained by TaqPath™ and Cobas® tests with those found with the gold standard method.

Table 3.

Concordance of results obtained with TaqPath™ and cobas® tests with those found with the gold standard method.

| Concordance with reference method | Number of samples | Genes detected | Ct (Median) | IQR | Ct Range | Number of samples with Ct > P95* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobas® test | Concordant (Truly positive results) | 114 | E | 36 | 34−36.9 | 29−40.9 | 5 |

| Orf1ab | 32.72 | 32.09−34.09 | 28.9−36.9 | 3 | |||

| Concordant (Truly negative results) | 160 | None | – | – | – | ||

| Discordant (false positive results) | 4 | E | 37.88 | 37.76−37.96 | 37.57−38 | 0 | |

| Orf1ab | – | – | – | ||||

| Discordant (false negative results) | 87 | None | – | – | – | ||

| Total | 365 | – | – | – | |||

| TaqPath™ Test | Concordant (Truly positive results) | 148 | N | 32.36 | 30.63−34.14 | 24.32−38.99 | 0 |

| S | 31.89 | 29.92−33.20 | 24.66−38.01 | 6 | |||

| Orf1ab | 31.81 | 30.01−32.92 | 23.93−38.31 | 0 | |||

| Concordant (Truly negative results) | 159 | None | – | – | – | ||

| Discordant (false positive results) | 5 | N | 37.46 | 36.92−38.80 | 4 | ||

| S | 37.47 | – | 1 | ||||

| Orf1ab | – | – | – | ||||

| ≥2 targets | – | – | – | ||||

| Discordant (false negative results) | 53 | None | – | – | – | ||

| Total | 365 | – | – | – |

P95: 95th percentile for each target.

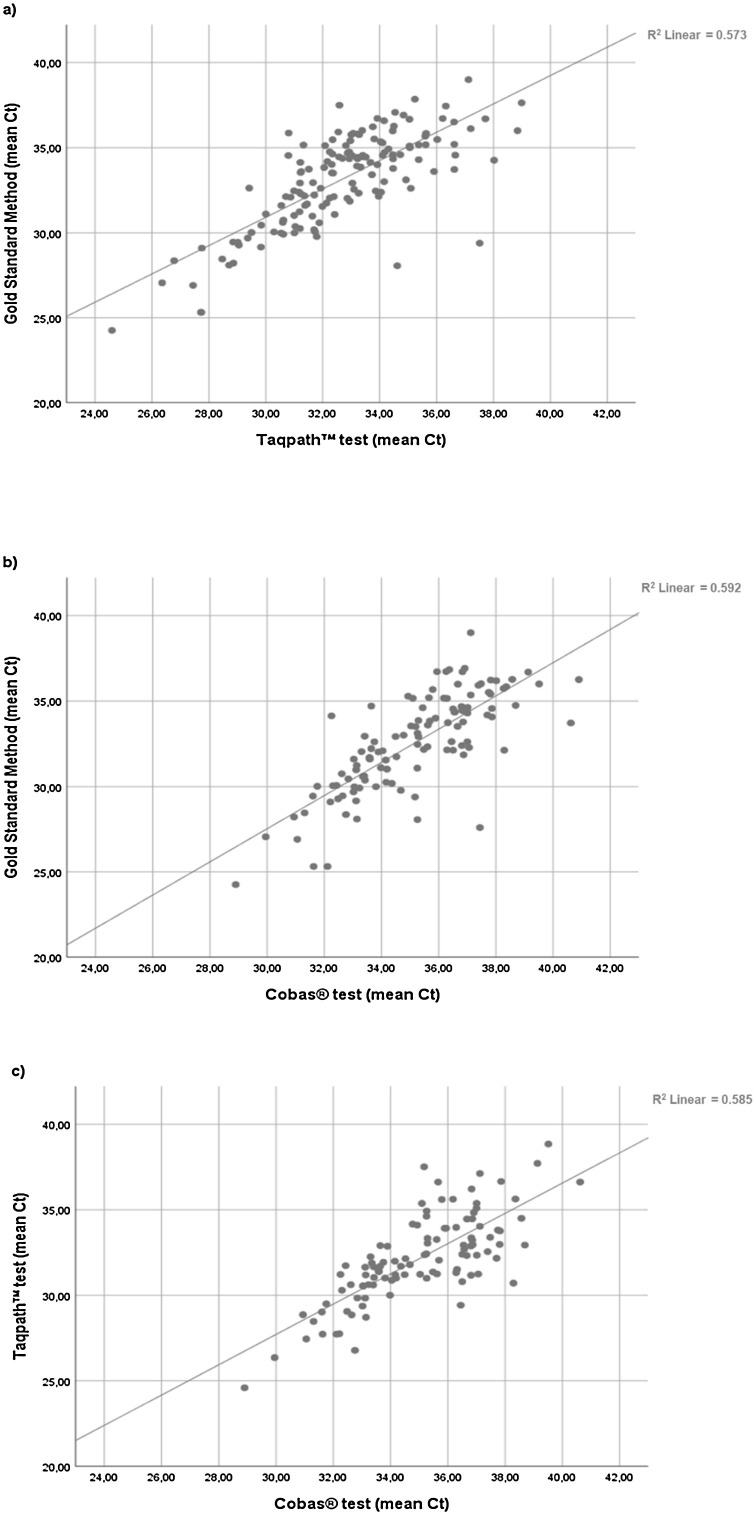

Comparison of the distribution of Ct values obtained for positive serum samples with the three methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Comparison of different rRT-PCR methods. Scatter plots represent mean Ct values of positive serum samples obtained by different rRT-PCR methods: gold standard method versus TaqPath™ test (a), gold standard method versus cobas® test (b) and TaqPath™ test versus cobas® test (c).

Cobas® test provided 4 false positive results by detecting only the e gene with Ct values from 37.57 to 38, while the TaqPath™ test provided 5 false positive by detecting only one target gene (n or s genes) with Ct values ranging from 36.92 to 38.8.

False negative results were obtained by cobas® test for 87 samples, 30 of which showed amplification of the two targets of the gold standard method, while the remaining 57 false negative samples showed amplification of only one target gene. Regarding the TaqPath™ test, 53 false negatives were obtained; most of them (42/53) were positive by detection of only one target gene of the gold standard method, while the rest (11/53), were positive by detection of both n and orf1ab genes, (supplementary Fig. 1). There was agreement with cobas® test in 45 (85 %) of the false negatives obtained by TaqPath™ test.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing two commercial rRT-PCR assays for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in serum samples. The goal of this study was to provide clinicians with a useful tool for the management of COVID-19. Although these commercial assays have not been validated for their use in serum or plasma samples, the extraction methods performed in this study are commonly used for other viruses in serum or plasma samples (Barreiro et al., 2015; Loens et al., 2007; Wirden et al., 2017).

The preferred method for SARS-CoV-2 detection is rRT-PCR of upper respiratory tract samples collected by nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs or, in some cases, lower respiratory tract samples (Pascarella et al., 2020). However, SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in multiple types of samples such as saliva, stool, plasma and serum (To et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum samples has been related to progression to critical disease and death (Hagman et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020), as well as to a cytokine storm syndrome (Chen et al., 2020) characterized by several inflammation and severe disease markers, such as lower absolute lymphocyte counts and higher levels of both C-reactive protein and IL-6 (Fajnzylber et al., 2020). Moreover, a recent study showed that prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 viremia is significantly higher in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with detectable troponin and myocardial injury (Siddiqi et al., 2020). However, most of the studies use in-house or commercial methods for SARS-CoV-2 detection that are not validated in serum or plasma samples (Hagman et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020).

In our study, viremia percentages obtained with the two rRT-PCR assays showed significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) between ICU patients and patients admitted to the general ward, thus supporting previous studies indicating that presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum samples is more common in critical patients and could be considered a prognostic indicator (Fajnzylber et al., 2020; Hagman et al., 2020; Hogan et al., 2020; Veyer et al., 2020).

Comparison between the assessed rRT-PCR kits and the gold standard method showed high specificity and positive predictive values, over 96 % for both techniques. These high values indicate that positive results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in serum samples of patients previously diagnosed for COVID-19 are reliable and should be taken into account by clinicians managing these patients.

Cobas® test showed four false positive results, all of them only showing amplification of the e gene. According to manufacturer’s indications, detection of the e gene without amplification of the orf-1ab region could be due to several factors, such as mutations in the amplification region of orf-1ab, low viral loads, or presence of other sarbecoviruses, among others. These results should be considered as presumptive positive results and be retested (“cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 Systems,” 2020). In this study, 52 true positive samples had amplification of the e gene. Therefore, it was decided to consider the amplification of only this target as a positive result based on several reasons. First, the serum samples collected in this study came from previously diagnosed COVID-19 patients. Secondly, according to the WHO (WHO, 2020b), SARS-CoV has only been reported four times since the end of the epidemic on July 2003 (three times associated to laboratory accidents and another one in Southern China). Accordingly, the probability that samples with e gene amplification without any other target are positive for other sarbecoviruses is very low; in addition, other reports also considered them as positives (Wirden et al., 2017).

The TaqPath™ test detected five false positive results, all of them with only one detected target and with high Ct values (from 36.92 to 38.80). Furthermore, these Ct values were over the 95th percentile, which suggests that false positive results may be obtained when only one gene is detected with a Ct within this range. Therefore, values over 37 are unlikely to be true positives, and should not be considered, which is in agreement with the last manufacturer’s indications (ThermoFisher Scientific, 2020). However, with this consideration, six concordant results considered as true positives would turn into false negative results, slightly decreasing sensitivity to 72.68 % but increasing specificity to 99.34 % (supplementary Table 1).

On the other hand, the negative predictive values obtained with both cobas® test and TaqPath™ test were low (64.78 % and 75 %, respectively), due to the high number of false negative results obtained (87 with cobas® Test and 53 with TaqPath™ test). Moreover, the high coincidence of false negative results between both techniques is remarkable; 85 % of TaqPath™ negative results were also negative with cobas® Test.

It is difficult to elucidate the cause of these false negative results, as we used commercial rRT-PCR kits whose design is not available for customers. Nevertheless, differences in the number of targets, and possibly in the sequence or the size of the amplicons, may cause differences in sensitivity between the techniques. Moreover, the cobas® test is performed in the automatic close cobas® 6800 system, making more difficult to elucidate the nature of discrepancies. A possible explanation is that these samples had low viral loads, decreasing the sensitivity of the assessed techniques. Also, the volume of eluted RNA added to the PCR reaction could have an influence since double volume is used for the gold standard method compared with the TaqPath™ test.

Regarding their implementation in clinical practice, both techniques can be easily introduced in the microbiology laboratory for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in serum samples and they can be performed along with SARS-CoV-2 detection in respiratory samples. The TaqPath™ test is more suitable to perform a small number of determinations at a time, while the cobas® test should be more useful to analyze a high number of samples.

The present study has some limitations. First, the intrinsic analytical variability of PCR may have exerted an influence on the results. Another limitation is the absence of significant differences between the percentage of viremia in ICU and non-ICU groups with the gold standard method, which may be due to a higher sensitivity in the detection of lower viral loads with this technique, which could lead to lower specificity. Finally, the type of sample used in this study is serum. Although serum samples are accepted in the analysis of viremia, the samples commonly used in most microbiology laboratories are plasma samples.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Test and TaqPath™ COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit could be useful for detecting SARS-CoV-2 viremia in serum of diagnosed COVID-19 patients. For good test performance both techniques require detection of at least one target, while the TaqPath™ assay additionally needs a Ct value under 37. A positive viremia result may help managing COVID-19 patients, since viremia has been recently related to bad prognosis and mortality in these patients (Fajnzylber et al., 2020; Hagman et al., 2020; Siddiqi et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). In addition, these techniques are easy to incorporate in the Microbiology laboratory routine practice for SARS-CoV-2 detection.

Finally, early detection of SARS-CoV-2 viremia could help to stratify COVID-19 patients facilitating different treatment strategies (Fajnzylber et al., 2020; Hagman et al., 2020; Patterson et al., 2021).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A. Martín Ramírez: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing. N. D. Zurita Cruz: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing. A. Gutiérrez Cobos: methodology, writing. D.A. Rodríguez Serrano: resources, writing. I. González Álvaro:resources, writing. E. Roy Vallejo: resources, writing. S. Gómez de Frutos:methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing.L. Fontán García-Rodrigo:methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing. L. Cardeñoso Domingo:conceptualization, methodology, writing, supervision.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the university hospital La Princesa independent research ethics committee (reference number 4267, acta CEIm 21/20).

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding to conduct the study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors do not have conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114411.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Barreiro P., Labarga P., Fernandez-Montero J.V., Mendoza Cde, Benítez-Gutiérrez L., Peña J.M., Soriano V. Rate and predictors of serum HCV-RNA &6 million IU/mL in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Clin. Virol. 2015;71:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Xu Z., Mu J., Yang L., Gan H., Mu F., Fan B., He B., Huang S., You B., Yang Y., Tang X., Qiu L., Qiu Y., Wen J., Fang J., Wang J. Antibody response and viraemia during the course of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;53:435–438. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhao B., Qu Y., Chen Y., Xiong J., Feng Y., Men D., Huang Q., Liu Y., Yang B., Ding J., Li F. Detectable serum SARS-CoV-2 viral load (RNAaemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 (IL-6) level in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z.J., Shan J. 2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- cobas . 2020. Cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative Assay for Use on the Cobas® 6800/8800 Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt K.A., Meyer-Schwickerath C., Heger E., Knops E., Lehmann C., Rybniker J., Schommers P., Eichenauer D.A., Kurth F., Ramharter M., Kaiser R., Holtick U., Klein F., Jung N., Di Cristanziano V. RNAemia corresponds to disease severity and antibody response in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Viruses. 2020;12:1045. doi: 10.3390/v12091045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajnzylber J., Regan J., Coxen K., Corry H., Wong C., Rosenthal A., Worrall D., Giguel F., Piechocka-Trocha A., Atyeo C., Fischinger S., Chan A., Flaherty K.T., Hall K., Dougan M., Ryan E.T., Gillespie E., Chishti R., Li Y., Jilg N., Hanidziar D., Baron R.M., Baden L., Tsibris A.M., Armstrong K.A., Kuritzkes D.R., Alter G., Walker B.D., Yu X., Li J.Z. The Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman K., Hedenstierna M., Gille-Johnson P., Hammas B., Grabbe M., Dillner J., Ursing J. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum as predictor of severe outcome in COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1285. ciaa1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan C.A., Stevens B.A., Sahoo M.K., Huang C., Garamani N., Gombar S., Yamamoto F., Murugesan K., Kurzer J., Zehnder J., Pinsky B.A. High frequency of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and association with severe disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1054. ciaa1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji T., Liu Z., Wang G., Guo X., Akbar khan S., Lai C., Chen H., Huang S., Xia S., Chen B., Jia H., Chen Y., Zhou Q. Detection of COVID-19: a review of the current literature and future perspectives. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loens K., Bergs K., Ursi D., Goossens H., Ieven M. Evaluation of NucliSens easyMAG for automated nucleic acid extraction from various clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:421–425. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00894-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella G., Strumia A., Piliego C., Bruno F., Del Buono R., Costa F., Scarlata S., Agrò F.E. COVID‐19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J. Intern. Med. 2020;288:192–206. doi: 10.1111/joim.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson B.K., Seethamraju H., Dhody K., Corley M.J., Kazempour K., Lalezari J., Pang A.P.S., Sugai C., Mahyari E., Francisco E.B., Pise A., Rodrigues H., Wu H.L., Webb G.M., Park B.S., Kelly S., Pourhassan N., Lelic A., Kdouh L., Herrera M., Hall E., Bimber B.N., Plassmeyer M., Gupta R., Alpan O., O’Halloran J.A., Mudd P.A., Akalin E., Ndhlovu L.C., Sacha J.B. CCR5 inhibition in critical COVID-19 patients decreases inflammatory cytokines, increases CD8 T-cells, and decreases SARS-CoV2 RNA in plasma by day 14. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;103:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansure Biotech Inc . 2020. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nucleic Acid Diagnostic Kit (PCR-Fluorescense Probing) Instructions for Use.https://www.fda.gov/media/137651/download [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi H.K., Weber B., Zhou G., Regan J., Fajnzylber J., Coxen K., Corry H., Yu X.G., DiCarli M., Li J.Z., Bhatt D.L. Increased prevalence of myocardial injury in patients with SARS-CoV-2 viremia. Am. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.09.046. S0002934320309335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThermoFisher Scientific . 2020. TaqPathTM COVID‑19 CE‑IVD RT‑PCR Kit INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE. [Google Scholar]

- To K.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Yip C.C.-Y., Chan K.-H., Wu T.-C., Chan J.M.-C., Leung W.-S., Chik T.S.-H., Choi C.Y.-C., Kandamby D.H., Lung D.C., Tam A.R., Poon R.W.-S., Fung A.Y.-F., Hung I.F.-N., Cheng V.C.-C., Chan J.F.-W., Yuen K.-Y. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:841–843. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyer D., Kernéis S., Poulet G., Wack M., Robillard N., Taly V., L’Honneur A.-S., Rozenberg F., Laurent-Puig P., Bélec L., Hadjadj J., Terrier B., Péré H. Highly sensitive quantification of plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA shelds light on its potential clinical value. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1196. ciaa1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – World Health Organization [WWW Document] URL https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed 10.4.20) [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) [WWW Document] URL https://www.who.int/ith/diseases/sars/en/ (accessed 10.29.20) [Google Scholar]

- Wirden M., Larrouy L., Mahjoub N., Todesco E., Damond F., Delagreverie H., Akhavan S., Charpentier C., Chaix M.-L., Descamps D., Calvez V., Marcelin A.-G. Multicenter comparison of the new Cobas 6800 system with Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas TaqMan and Abbott RealTime for the quantification of HIV, HBV and HCV viral load. J. Clin. Virol. 2017;96:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Zhou F., Sun W., Chen L., Lan L., Li H., Xiao F., Li Ying, Kolachalama V.B., Li Yirong, Wang X., Xu H. Relationship between serum SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid(RNAemia) and organ damage in COVID-19 patients: a cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1085. ciaa1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Du R.-H., Li B., Zheng X.-S., Yang X.-L., Hu B., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Yan B., Shi Z.-L., Zhou P. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386–389. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.