Abstract

Background

Sedentary behaviour (SB; time spent sitting) is associated with musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions; however, no prior systematic review has examined these associations according to SB domains. We synthesised evidence on occupational and non-occupational SB and MSP conditions.

Methods

Guided by a PRISMA protocol, eight databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, SPORTDiscus, and AMED) and three grey literature sources (Google Scholar, WorldChat, and Trove) were searched (January 1, 2000, to March 17, 2021) for original quantitative studies of adults ≥ 18 years. Clinical-condition studies were excluded. Studies’ risk of bias was assessed using the QualSyst checklist. For meta-analyses, random effect inverse-variance pooled effect size was estimated; otherwise, best-evidence synthesis was used for narrative review.

Results

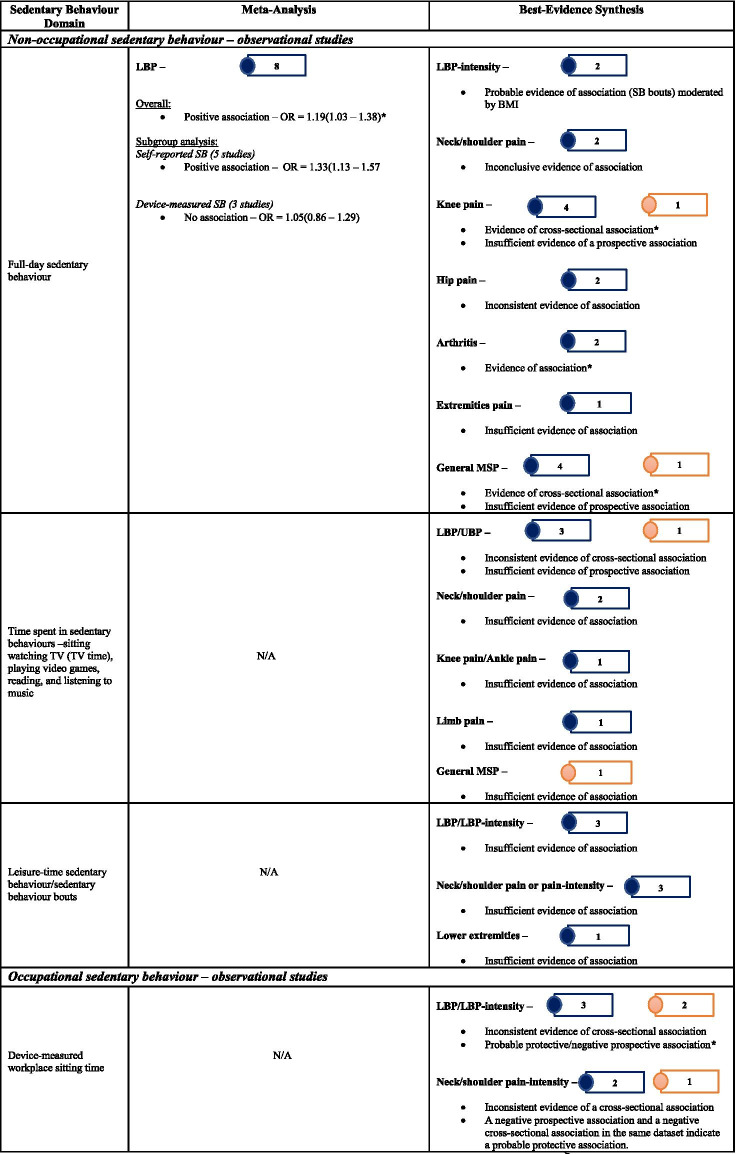

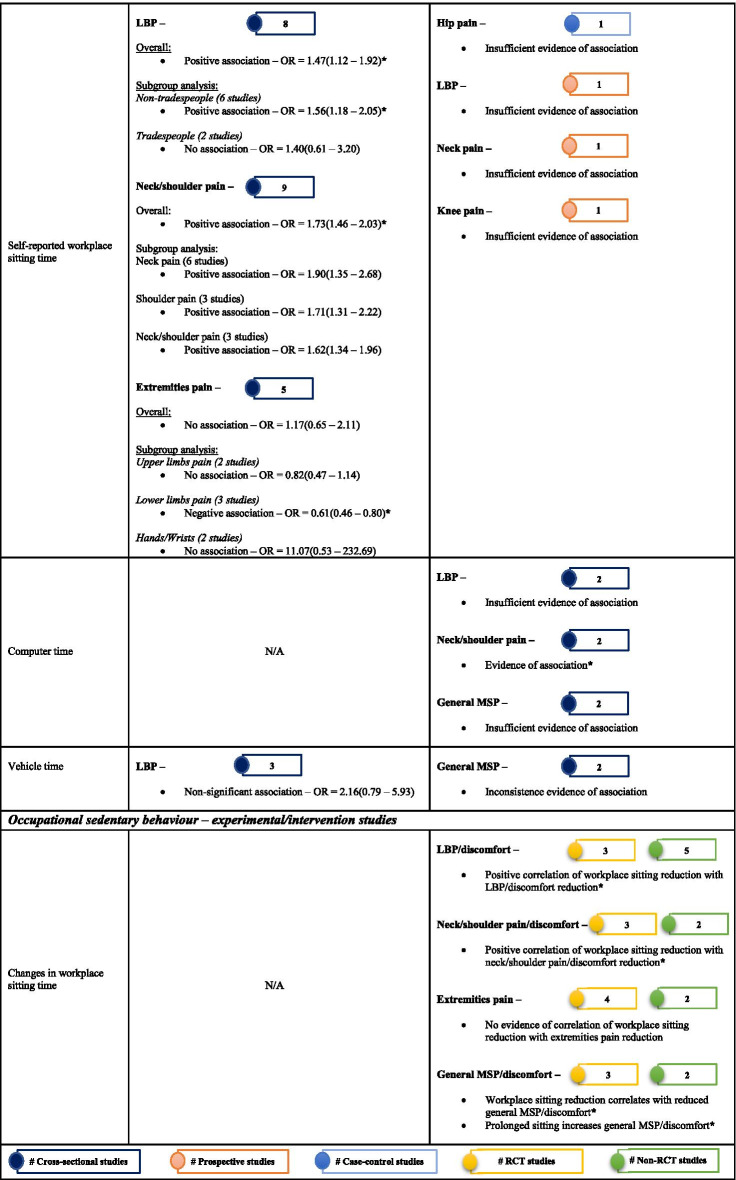

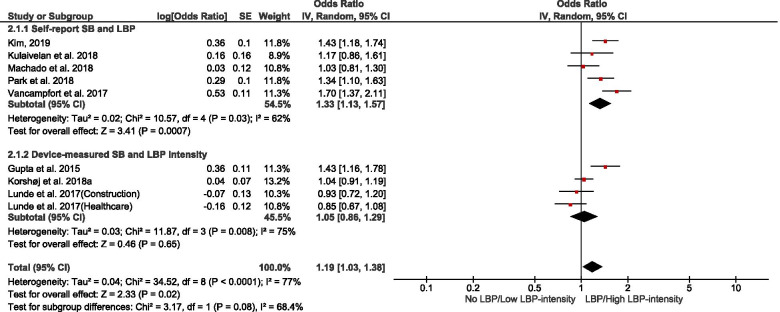

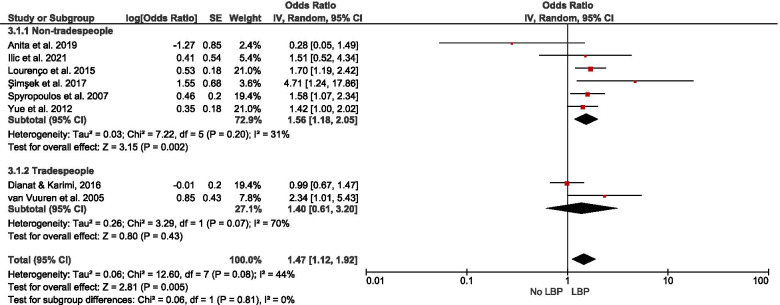

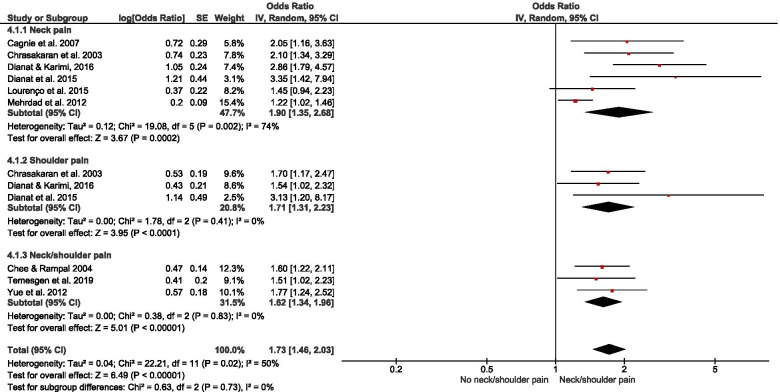

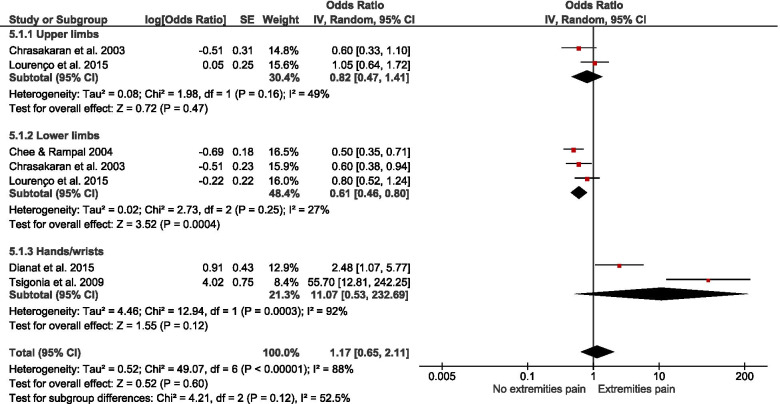

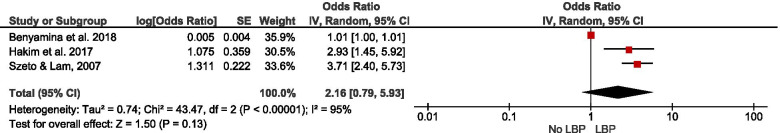

Of 178 potentially-eligible studies, 79 were included [24 general population; 55 occupational (incuding15 experimental/intervention)]; 56 studies were of high quality, with scores > 0.75. Data for 26 were meta-synthesised. For cross-sectional studies of non-occupational SB, meta-analysis showed full-day SB to be associated with low back pain [LBP – OR = 1.19(1.03 – 1.38)]. Narrative synthesis found full-day SB associations with knee pain, arthritis, and general MSP, but the evidence was insufficient on associations with neck/shoulder pain, hip pain, and upper extremities pain. Evidence of prospective associations of full-day SB with MSP conditions was insufficient. Also, there was insufficient evidence on both cross-sectional and prospective associations between leisure-time SB and MSP conditions. For occupational SB, cross-sectional studies meta-analysed indicated associations of self-reported workplace sitting with LBP [OR = 1.47(1.12 – 1.92)] and neck/shoulder pain [OR = 1.73(1.46 – 2.03)], but not with extremities pain [OR = 1.17(0.65 – 2.11)]. Best-evidence synthesis identified inconsistent findings on cross-sectional association and a probable negative prospective association of device-measured workplace sitting with LBP-intensity in tradespeople. There was cross-sectional evidence on the association of computer time with neck/shoulder pain, but insufficient evidence for LBP and general MSP. Experimental/intervention evidence indicated reduced LBP, neck/shoulder pain, and general MSP with reducing workplace sitting.

Conclusions

We found cross-sectional associations of occupational and non-occupational SB with MSP conditions, with occupational SB associations being occupation dependent, however, reverse causality bias cannot be ruled out. While prospective evidence was inconclusive, reducing workplace sitting was associated with reduced MSP conditions. Future studies should emphasise prospective analyses and examining potential interactions with chronic diseases.

Protocol registration

PROSPERO ID #CRD42020166412 (Amended to limit the scope)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12966-021-01191-y.

Keywords: Sedentary behaviour (SB), Occupational, Non-occupational, Workplace sitting, Self-reported, Device-measured, Computer time, Vehicle time, Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions

Background

The burden of musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions has increased in recent decades, contributing to substantial health care costs [1]. According to 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates, age-standardised disability-adjusted life years attributable to MSP conditions excluding low back pain (LBP) increased from 1990 to 2019 by some 30.7 percentage points [2]; whereas the 2017 GDB report ranked LBP as the second-highest contributor to years lived with disability [3]. The prevalence of MSP conditions has increased in parallel with the rising burden of chronic disease and is most pronounced in those with multi-morbidities [3, 4]. Also, MSP can substantially limit mobility and engagement in regular physical activity, thereby predisposing to increased risk of other chronic conditions [3].

The biological mechanisms contributing to MSP conditions are heterogeneous; nonetheless, obesity, static working postures, physical inactivity, smoking, and aging, as well as cardiometabolic and systemic inflammation, are some factors identified to increase the prevalence of MSP [5, 6]. While there is convincing evidence of beneficial associations of physical activity with outcomes related to MSP conditions [7, 8] there is an additional element to consider in this nexus – sedentary behaviour (SB). Defined as time spent in sitting and/or reclining postures during waking hours, with energy expenditure less than 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) [9] – SB is associated with increased risk and unfavourable outcomes of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, musculoskeletal diseases, and some cancers, as well as all-cause mortality [10, 11]. Intervention trials have shown that reducing sitting time can result in modest improvements in some biomarkers of health risk [12, 13]. From a population health perspective, excessive time spent sitting is common among older adults, especially in those with co-morbidities such as cardiovascular and metabolic disorders [14, 15].

Epidemiological evidence indicates higher volumes of SB are associated with several MSP conditions, including osteoarthritis, back pain, and neck/shoulder pain [16, 17]. Some of these findings are from low-level evidence cross-sectional studies and there could be potential reverse causality bias [16]; inferring a causal relationship between SB and MSP may therefore be problematic as pain and chronic disease could predispose to engagement in excessive SB [18]. There is, however, an inconsistent body of evidence of associations of SB with MSP conditions and related outcomes from high-level evidence-based studies [19, 20]. Some previous systematic reviews of studies including higher-level study designs have reported no associations of SB with the prevalence of some MSP conditions [19–24], whereas others have reported either positive [20, 25] or negative [26] associations with some MSP-related outcomes such as pain intensity. Methodological differences and limitations within the individual studies reviewed in these systematic reviews could impact the quality of evidence and comparability of these reviews as some of the studies were based on self-reported and surrogate estimates of SB which increases the risk of bias [19, 21, 22, 24, 27]. The emergence of evidence on device-measured SB, especially from studies using the ActiGraph and activPAL devices has improved the quality of SB evidence in recent research outputs [25–27].

There could be other reasons for the equivocal associations, including factors related to the influence of the specific domains of SB (e.g., work, transport, domestic) and the relative exposure of the studied population. This perspective suggests potential contributions of different domains of SB to the risk of adverse health outcomes, which may differ from the effects of total full-day SB [28–30]. Moreover, evidence on differences in health effects of different SB domains has been identified as a key knowledge gap by the 2020 World Health Organisation (WHO) physical activity and SB guidelines development group [31]. Existing systematic reviews have not identified differences according to domains in the associations of SB with MSP conditions.

This distinction is important, partly because, most working adults accumulate SB in both occupational and non-occupational settings. That said, SB could predispose to MSP conditions in certain occupational groups such as desk-based workers who commonly engage in a prolonged sitting [32, 33]. In this context, interventions to reduce prolonged workplace sitting time by breaking up sitting with standing and/or light walking have shown beneficial associations with a reduction in MSP or musculoskeletal system discomfort among desk-based workers [34, 35]. Thus, SB associations may also reflect plausible biomechanical or biological pathways explaining MSP conditions in those exposed to prolonged static sitting postures [36–38]. Paradoxically, however, in occupational groups such as tradespeople who engage in more labour-intensive manual work, SB may be a protective behaviour against MSP conditions and other chronic diseases [39–41].

We conducted a systematic review to examine evidence on the associations of SB with MSP conditions in observational and experimental/intervention studies of adults. Specifically, we examined and synthesised evidence separately for associations of SB with MSP conditions in the occupational and non-occupational SB domains.

Methods

Review design

We used a standard Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines-based pre-designed protocol (PROSPERO ID: CRD42020166412 – amended to limit the scope of the review) to ensure a transparent review [42, 43]. The a priori research question and search strategy were formulated according to the Population, Intervention, Control/Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework [44] to enhance search precision and ensure extensive data extraction to be representative and unbiased [45]. The research question was: What are the associations of occupational and non-occupational SB with MSP conditions in adults?

Search strategy

Using a comprehensive search strategy, search terms were identified and combined using Boolean operators to search the following electronic databases: MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, SPORTDiscus, and AMED. Additionally, three online grey literature databases, including Google Scholar, WorldChat, and Trove, were searched to also identify non-peer-reviewed studies to help to minimise publication bias [46]. The search was conducted by one reviewer, for consistency, with the guidance of a librarian (Australian Catholic University, Melbourne) initially on January 5, 2020; and, further updated on November 1, 2020, and March 17, 2021. The search filter was set to limit search results to studies published from January 1, 2000, onwards. This timeframe was chosen because the field of SB is relatively new, the early definitive papers were published at the beginning of this period, and SB research output has grown significantly over the past two decades [9].

The search terms format, guided by the PICO framework, included keywords, terms, and phrases related to SB (Exposure/Intervention); MSP conditions (Outcome); and adults (Population). The search was optimized by adding to the search string, newly identified key terms that consistently appear in titles and abstracts of retrieved studies during the search [47]. A supplementary file (Supplementary Table 1: Search key terms and strings strategy – A sample Medline database search syntax) describing the comprehensive search term framework is attached.

Study eligibility and selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The selection of eligible studies was based on pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewed studies satisfied all the criteria below:

An original quantitative study involving either an observational or intervention/experimental design. This included cross-sectional, case–control studies, and prospective studies, as well as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized experimental study designs.

The study was conducted in adults aged 18 years or older and examined relationships between SB (the exposure of interest) and MSP conditions (the outcome of interest).

The study included a measure of any kind of MSP condition, including inflammatory and non-inflammatory MSP conditions such as back pain, joint/osteoarthritis, and pain in extremities (except for pain attributable, acutely or recently, to trauma). Autoimmune-related MSP conditions, for example, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia were not included in this review because the pathophysiology of these conditions is mainly attributable to the processes and progression of specific clinical disease entities with autoimmune causations. Some studies did not measure a specific type of MSP condition but produced a composite measure of MSP conditions. Those that measured arthritis but excluded fibromyalgia were considered for inclusion because the majority of reported cases of arthritis are likely to be osteoarthritis rather than rheumatoid arthritis. There is no universally accepted measure for MSP conditions; therefore, any acceptable measures described in studies provided the basis for considering studies to be appropriately inclusive of MSP conditions.

The study clearly defined or stated the measure of SB. Specifically, the study reported a self-report measure or device-based measure of occupational or non-occupational SB. This included population-based or occupational/workgroup cohort studies that measured SB exposures that aligned with the focus of our review.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the criteria described below:

all qualitative studies and those quantitative studies involving children and adolescent populations aged below 18 years;

studies that did not appropriately define SB; those that used proxy estimates, such as “less active”, “inactive” or “does not engage in physical activities”; those that did not make a clear distinction between SB and physical inactivity and included these as overlapping behaviours or used these terms interchangeably;

studies that focused on SB as an outcome but did not explicitly examine the relationship of SB with MSP conditions; studies that focused only on the relationship between physical activity and MSP conditions;

studies conducted exclusively in clinical groups with existing clinically diagnosed MSP conditions, e.g., knee osteoarthritis patients that focused on symptom severity as outcome measures;

opinion or perspective articles, conference papers, editorials, newsletters, and review studies, however, the reference lists of some literature reviews on a similar topic were hand-searched for relevant studies;

studies published in languages other than English.

Screening and selection process

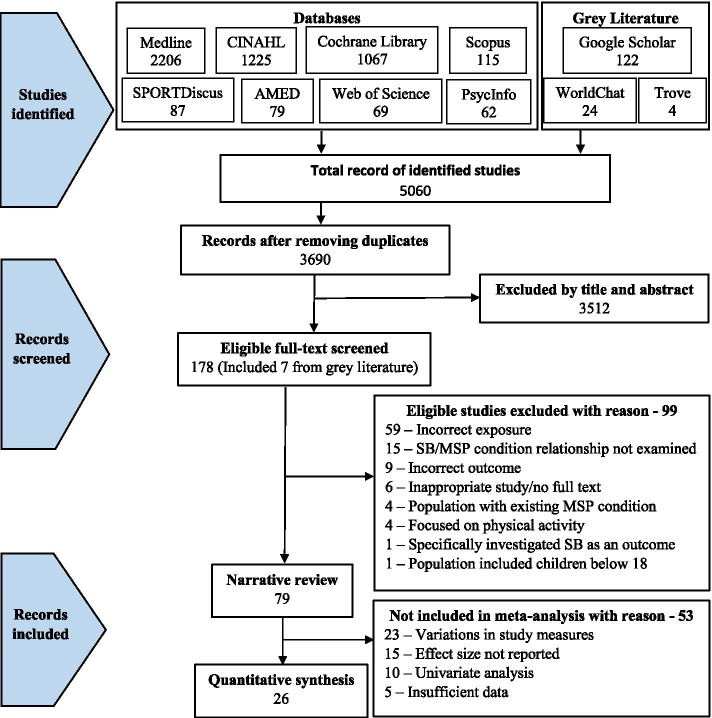

A two-stage approach was used to process all identified studies before arriving at the final set of studies for inclusion in this review. First, the reviewer (FD), exported all the retrieved studies into Endnote reference manager software [48], checked and removed duplicate studies. The refined list of studies was exported into collaboration-supported Rayyan systematic review software [49] for screening. One reviewer (FD) initially screened and removed irrelevant studies by title and abstract according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, but where there was uncertainty regarding inclusion, such studies were considered in stage two screening. The second stage involved retrieval of full-text articles of retained studies, and two reviewers (FD and CB), independently read and assessed the full-text articles for inclusion. Disparities were discussed and resolved among the two reviewers; however, when uncertainty remained, they consulted with three senior reviewers (AC, NO and DD). Records of retained studies as well as reasons for exclusion (at stage two) were documented using a PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the studies record

Data extraction

A pre-designed data extraction form was used to organise relevant information from the studies reviewed, to ensure data quality, and to minimise errors [50]. Reviewer FD extracted data from all the studies, and this was verified independently by CB. The verification process involved the comparison of data extracted by CB from randomly selected studies (not less than 20%) with the extracts of FD [51]. Disagreements were resolved harmoniously. Extracted data included:

Descriptive details – study title, author name, year of publication, place of study, study aim

Study design – cross-sectional, case–control, prospective, experiment/RCT/non-RCT

Study population – population-based, occupational/workgroup cohort

Sample size

Demographic information of study participants – e.g., gender, mean age or age range, and BMI.

SB and measures – occupational SB, non-occupational SB, self-report and objective measures.

Outcome variables and measures – MSP conditions, e.g., back pain, neck/shoulder pain, osteoarthritis, and extremities pain.

Intervention/experiment detail (when applicable) – type, duration, assessment point(s), effect size, etc.

Other relevant data relating to the MSP condition outcomes and their measures – e.g., pain intensity and disability.

Study quality assessment

Quality assessment for the included studies was undertaken (independently by two reviewers) using the quantitative checklist of QualSyst (Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields) [52]. Briefly, the quantitative QualSyst checklist is scored on 14 criteria as either “YES = 2”, “PARTIAL = 1”, “NO = 0” or “NOT APPLICABLE” (N/A) depending on the extent to which each criterion item is satisfied by the study report. Items marked ‘N/A’ were excluded from the computation of the QualSyst summary score. For each paper, a summary score was computed by summing scores across items and dividing this by the maximum possible score for all relevant items [i.e., 28 – (number of ‘N/A’ items × 2)] [52]. Disparities in the assessments were discussed and resolved between the assessors, and if required, the three senior reviewers arbitrated. Note, however, that the quality assessment score was not a criterion for study selection but was to be considered in the determination of the robustness of our data synthesis.

Data synthesis

The extracted data were first categorised broadly as either general population or occupational cohort studies. Thereafter, they were summarised as either observational or experimental/intervention studies. The observational studies were then further organised according to study design (cross-sectional/case–control and prospective), and experimental/intervention studies were categorised as RCTs and non-RCTs to simplify the evidence synthesis. Within the categories, the SB domain measured was organised into occupational and non-occupational SB, and the measuring instrument into device-measured and self-reported SB. Further, grouping was completed according to measured SB [full-day, leisure-time, workplace sitting, computer time, vehicle time (time spent sitting in a vehicle), and sedentary behaviours (SBs) – time spent watching television, on computer/video gaming, reading or talking on the phone], as well as the type of MSP condition outcomes. The MSP conditions included back pain (low back pain – LBP and upper back pain – UBP); neck/shoulder pain; knee osteoarthritis (pain); extremities pain (upper and lower); and other MSP conditions (included MSP conditions reported no more than three in the reviewed studies; a general MSP/discomfort or collectively measured MSP conditions; and arthritis).

Descriptive tables and narrative text provide a general overview of the studies reviewed. MSP condition outcomes (e.g., back pain, neck/shoulder pain, and knee osteoarthritis) reported in three studies or more with permissible variations in the study designs and measures were quantitatively synthesised. Otherwise, the MSP condition is presented in a narrative review.

Narrative review

In the case whereby meta-analysis was not feasible, individual study findings were systematically described and integrated using the best-evidence synthesis in a narrative text [53, 54]. This commonly used synthesis approach takes into account the quality and the consistency of reported findings of the studies in three levels – strong evidence (≥ 75% of the studies show consistent significant findings in the same direction of ≥ 2 high-quality studies; moderate evidence (consistent significant findings in the same direction of a high-quality and at least a low-quality studies or ≥ 2 low-quality studies; and insufficient evidence (inconsistent findings in ≥ 2 studies or just a single available study). When there were ≥ 2 studies of high quality in a category, our conclusion on the evidence of associations was based on the within- and between-relationships of the high-quality studies.

Quantitative synthesis

Pooled meta-analysis was performed on homogenous data for SB and MSP condition outcomes when permissible. The RevMan5 (Review Manager 5.4.1) inverse-variance approach was used to estimate the pooled effect size (in odds ratio) based on random effect due to the heterogeneity of the data [55]. When there were sufficient studies, subgroup analysis was performed based on self-reported and device-measured SB. To gain insight on how occupation type could mask the association of workplace sitting with MSP conditions, a subgroup analysis by occupation type was performed. Further, subgroup analysis was conducted for studies that reported neck, shoulder, and neck/shoulder pain, and for a subgroup that reported extremities pain. Pooled effect relationships were illustrated by forest plots, and data heterogeneity was estimated by I2, Tau2, and Cochran’s Chi-square. The robustness of our estimated pooled effect sizes was examined in a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies of low quality from the estimate; we used a funnel plot to illustrate potential publication bias.

In general, evidence synthesised by narrative review (the best-evidence synthesis) or quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) from observational studies was regarded as either of low quality for cross-sectional/case–control studies-based evidence or high quality for prospective studies-based evidence. Evidence synthesised from experimental/intervention studies was regarded as of moderate/high quality depending on the relative contribution of non-RCT and RCT studies in the evidence.

Results

The search identified 5060 studies (Fig. 1) and 3690 remained after removing duplicates. These studies were screened by title and abstract according to the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 178 studies were retained for full-text screening. Of these, we excluded 99 studies (Supplementary Table 2: Studies excluded after full-text screening) after the full-text screening, leaving 79 studies published from 2000 to 2021 for the evidence synthesis, including 26 studies for meta-analysis. The included studies had representation from 36 different countries. Several of these countries were the settings for five or more studies: Australia (10), Denmark (8), Brazil (8), South Korea (5), the USA (5), and the UK (5).

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the studies are detailed in Tables 1, 2, and 3 for the general population cohorts, observational occupational cohorts, and experimental/intervention occupational cohorts, respectively. Overall, 24 observational studies were categorised as general population cohort studies; 55 studies as occupational cohort studies, which included 40 observational studies and 15 experimental/intervention studies. The occupational category comprised studies of office workers (21); professionals – physicians, specialists, nurses, university staff, teachers, students, and police duty officers (20); tradespeople and manual workers – construction, factory, manufacturing, cleaning, transport, handicraft, sewing machine operators, steel plant workers and beauticians (14); and bus drivers (3), included a study [56] that recruited office workers, professionals, and tradespeople; and another study [57] was also of professionals and tradespeople. Cross-sectional designs and a case–control design accounted for 75% and prospective designs 25% in the general population category, whereas 85% of the observational studies in the occupational category were cross-sectional and 15% had prospective designs. Among the experimental/intervention studies, however, there were six randomised controlled trials (RCTs), two randomised cross-over trials, and two non-randomised experiment without control; one study each of non-RCT, randomised trial (RT) without control, non-RT without control (a pilot study), non-randomised cross-over trial, and a cross-sectional analysis of a dataset from an RCT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the general population studies

| Study ID + Country | Study population + Duration + Sample size + Average age/ BMI + %Female + Study name | Sedentary behaviour (SB) domain + Measures | Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions + % Prevalence + Measures | Statistical analysis + Adjusted covariates | Conclusions on associations of SB with MSP conditions + Effect size/p-value | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design – cross-sectional | ||||||

| Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

|

Aweto et al. 2016 [58] Nigeria |

51 – 80 years Sample size = 182 Average: age = 70.17(8.62), BMI = NR %Female: 54.95% |

Non-occupational – Sedentary behaviours (TV, reading, listening to music, sitting in a car, lying, talking on the phone) Self-reported |

LBP, UBP, Shoulder pain, Neck pain, Knee pain, Ankle pain, Elbow pain, Arm pain – Point and 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: point prevalence = 51.6%; 12-months prevalence = 87.4% Self-reported |

Chi-square (χ2) test |

Positive associations of sedentary behaviours with LBP; UBP; Knee pain; and Ankle pain. No association with Neck/shoulder and Elbow pain LBP: χ2 = 15.7, p-value = 0.02; UBP: χ2 = 13.6, p-value = 0.03; Knee pain: χ2 = 16.8, p-value = 0.01; Ankle pain: χ2 = 14.2, p-value = 0.03; Shoulder pain: χ2 = 10.6, p-value = 0.56; Neck pain: χ2 = 7.8, p-value = 0.62; Elbow pain: χ2 = 5.6, p-value = 0.72 |

0.41 |

|

Kang et al. 2020 [59] South Korea |

≥ 50 years Sample size = 3,761 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 48.3% |

Non-occupational – Total SB(≥ 7.5 h/day) Self-reported |

Orthopaedic problems (OPPs): LBP, knee pain, and hip pain – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: men – 17.7% OPPs; women – 28.6% OPPs Self-reported |

Multiple logistic regression Adjusted for age, education, income, occupation, marital status, smoking, BMI, physical activity at work, leisure physical activity, alcohol, sleep duration |

Positive association of total SB (≥ 7.5 h/day) with OPPs in men [OR(95%CI) = 1.45(1.08 – 1.93)], and no association in women [OR(95%CI) = 1.04(0.80 – 1.35)] Men had a positive association with knee pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.80(1.11 – 2.92)], whereas women had a positive association with hip pain [OR(95%CI) = 2.05(1.35 – 3.11)] No associations of total SB (≥ 7.5 h/day) with LBP in both men and women, knee pain in women, and hip pain in men |

0.91 |

|

Kim, 2019 [60] South Korea |

≥ 65 years Sample size = 301 Average: age = 72.93(0.11), BMI = NR %Female: 58.3% Korea’s 6th National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI) |

Non-occupational – Total SB (≥ 7.5 h/day) Self-reported |

LBP; Osteoarthritis; Knee pain; Hip pain – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: LBP = 30.5; Osteoarthritis = 92.7; Knee pain = 27.3; Hip pain = 12.8 Self-reported |

Multiple logistic regression Adjusted for sex, age, obesity, housing type, family income, education, and marital status |

Positive associations of total SB (sitting) with LBP, knee pain, hip pain; and no association with osteoarthritis LBP: OR(95%CI) = 1.44(1.19 – 1.74), p < 0.001; Knee pain: OR(95%CI) = 1.41(1.11 – 1.79), p < 0.05; Hip pain: OR(95%CI) = 1.54(1.1 – 2.03), p < 0.05; Osteoarthritis: OR(95%CI) = 1.72(0.86 – 3.43), p = 0.126 |

0.91 |

|

Kulaivelan et al. 2018 [61] India |

All adults Sample size = 1503 Average: age = 48.23(13.12), BMI = 25.97(4.57) %Female: 54.2% |

Non-occupational – TV time, TB SB (sitting) Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 9.0% Self-reported – MNMQ |

Binary logistic regression Adjusted for smoking, income, sleeping hours, scheduled caste |

No associations of TV time and total SB (sitting) with LBP Sitting time (upper quartile): OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.85 – 1.62); TV time(> 2 h/day): OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.82 – 1.66) |

0.68 |

|

Lee et al. 2019 [16] South Korea |

≥ 50 years Sample size = 8008 (Without chronic pain = 6344, chronic pain = 1664) Average: age – without chronic knee pain = 65.2(9.3), chronic knee pain = 61.3(8.7); BMI – without chronic knee pain = 24.0(3.1), chronic knee pain = 24.7(3.3) %Female: without chronic knee pain = 72.6%, chronic knee pain = 27.4% KNHANES VI |

Non-occupational – Total SB (< 5, 5–7, 8–10, and > 10 h/day) Self-reported – IPAQ |

Chronic knee pain – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: 20.8% Self-reported |

Multivariable logistic regression Adjusted for age and BMI, individual factors (lifestyle factors and health factors), such as smoking, alcohol consumption, occupation, education, household income, physical activity, depression, and sleep duration |

Total SB (> 10 h/day) is significantly positively correlated with chronic knee pain, especially in women even with high levels of physical activity Total SB > 10 h/day – Overall: OR(95% CI) = 1.28(1.02 – 1.61), p = 0.03; Women: OR(95% CI) = 1.33(1.02 – 1.74), p = 0.04; Men: OR(95% CI) = 1.17(0.78 – 1.75), p = 0.46 |

0.95 |

|

Loprinzi, 2014 [62] USA |

≥ 65 years Sample size = 1753 Average: age – T2D = 73.4, without diabetes = 74.3; BMI – diabetes = 30.2, without diabetes = 27.3 %Female: diabetes = 55.1%, without diabetes = 74.3%, All = 57.4% National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) |

Non-occupational – Total SB Device-measured – ActiGraph |

Arthritis %Prevalence – With diabetes = 43.4%; without diabetes = 33.5% Self-reported |

Wald tests and design-based likelihood ratio tests were used to examined statistical differences Adjusted for gender, age, and accelerometer wear time |

Positive association of total SB with arthritis in both T2D and non-diabetes P-value: T2D = 0.001; without diabetes < .0001 |

0.91 |

|

Machado et al. 2018 [63] Brazil |

≥ 65 years Sample size = 378 Average: age = 75.5(6.1), BMI = 27.3(4.9) %Female: 70.9% The PAINEL Study |

Non-occupational – Total SB Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 9.3% Self-reported |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, income, multimorbidity, depressive symptoms, sleep hours, years of schooling, smoking, physical activity level |

No association of total SB with LBP Sitting time 4.2(2.5) h/day: OR(95%CI) = 1.03(0.81 – 1.31) |

0.73 |

|

Mendonça et al. 2020 [64] Brazil |

All adults – Severely obese Sample size = 150 Average: age = 39.6(0.7), BMI = 46.1(0.5) %Female: 85.3% ‘DieTBra Trial’ |

Non-occupational – Total SB (Low SB < 1,182.15 min/day) Device-measured – ActiGraph |

MSP –Neck, shoulders, elbows, upper back, lower back, wrist/hands, hips/thighs, knees, and ankles/feet %Prevalence: 89.3%(site with high prevalence – ankle/feet = 68.7%), LBP = 62.7%, knees = 53.3%, and UBP = 52.0%) Self-reported |

Poisson regression Adjusted for sex, age, skin colour, years of schooling, economic class, and occupation |

Low total SB (< 1,182.15 min/day) is associated with hip pain, but no association with shoulder pain and wrist/hands pain Hip pain: PR(95%CI) = 1.84(1.05 – 3.21), p = 0.032. Shoulder pain: PR(95%CI) = 1.76(0.96 – 3.23), p = 0.066; Wrist/hands: PR(95%CI) = 0.59(0.33 – 1.06), p = 0.078 |

0.95 |

|

Mendonça et al. 2020a [65] Brazil |

All adults – Severely obese Sample size = 150 Average: age = 39.57(0.72), BMI = 46.12(0.53) %Female: 85.33% ‘DieTBra Trial’ |

Non-occupational – Total SB(Low SB < 1,182.15 min/day); Device-measured – ActiGraph |

MSP-related pain intensity %Prevalence: pain – 89.33%, severe pain – 69.33%, and pain in four or more sites – 53.33% Self-reported |

Poisson regression Adjusted for demographic data (gender, education, and economic class), diet and exercise (fruit and vegetable consumption and MVPA [min/day]), and clinical characteristics (falls in the last 12 months, fracture, anxiety, depression, arthritis/arthrosis, use of analgesics, and muscle relaxant use) |

A longer duration of total SB is associated with the experience of more pain SB < Median (1182.15): Pain – PR(95%CI) = 0.95(0.86 – 1.06), p = 0.399; Severe pain – PR(95%CI) = 1.09(0.88 – 1.35), p = 0.432; Four or More Painful Sites – PR(95%CI) = 1.06(0.79 – 1.44), p = 0.680 |

0.91 |

|

Park et al. 2018 [66] South Korea |

≥ 50 years Sample size = 5364 Average: age = without LBP = 63.4(8.7), LBP = 67.3(9.1); BMI = without LBP = 24.1(3.1), LBP = 24.4(3.4) %Female: without LBP = 52.3%; LBP = 74.2% KNHANES |

Non-occupational – Total SB Self-reported – IPAQ |

LBP – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: 22.8% Self-reported |

Multiple logistic regression Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, socioeconomic factors, education, household income, smoking, alcohol, and comorbidities |

Positive association of total SB with LBP Sitting time > 7 h/day: OR(95%CI) = 1.33 (95% CI, 1.10 – 1.61) |

0.95 |

|

Ryan et al. 2017 [67] UK |

All adults Sample size = 2313 Average: age = 52(18), BMI = 28(5) %Female: 55% Health Survey for England (HSE) |

Non-occupational – Total SB Device-measured – ActiGraph |

Chronic MSP %Prevalence: 17% Self-reported |

Isotemporal substitution Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, diet, smoking history, alcohol intake, anxiety/depression, and presence of anon-musculoskeletal long-standing illness |

Replacing 30 min SB with 30 min MVPA has a small but clinically relevant protective association with the chronic MSP prevalence ratio Substituting 30 min SB with 30 min MVPA: PR(95%CI) = 0.71(0.55 – 0.88) |

0.95 |

|

Sagat et al. 2020 [68] Saudi Arabia |

18 – 64 years Sample size = 463 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 44.1% |

Non-occupational – Total SB (Sitting always or most of the time) Self-reported |

LBP intensity %Prevalence: Before quarantine = 38.8%, During quarantine = 43.8% Self-reported |

Spearman test for correlation |

A significant positive correlation of LBP intensity with sitting during Covid-19 quarantine Correlations of LBP intensity with sitting: Before quarantine – r = 0.054, p = 0.216; During quarantine – r = 0.124, p = 0.008 |

0.59 |

|

Smuck et al. 2014 [69] USA |

All adults Sample size = 6796 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: NR NHANES |

Non-occupational – Total SB, sedentary bout Device-measured –ActiGraph |

LBP – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: NR Self-reported |

Adjusted weighted logistic regression Adjusted for BMI |

Positive association of total SB and mean sedentary bout with LBP Maximum SB bout [1239(903) min]: OR(95%CI) = 1.03(1.1 – 1.8); Average SB bout [50.0(46.9) min]: OR(95%CI) = 1.09(1.3 – 3.0) |

0.91 |

|

Vancampfort et al. 2017 [70] China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa |

≥ 50 years Sample size = 34,129 (China = 13,175; Ghana = 4305; India = 6560; Mexico = 2313; Russia = 3938; South Africa = 3838) Average: age = median (IQR): 62(55 –70) years, BMI = NR %Female: 52.1% SAGE |

Non-occupational – Total SB (≥ 8 h per day) Self-reported |

Chronic LBP – 1-month prevalence %Prevalence: 8.6%, Arthritis %Prevalence: 29.5% Self-reported |

Multivariable logistic regression Adjusted for sex, age, education, wealth, setting, unemployment, living arrangement, and country, comorbid chronic conditions |

Positive association of total SB with arthritis and chronic LBP Arthritis Overall: OR(95%CI) = 1.22(1.03 – 1.44); 50-64 years: OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.92 – 1.49); ≥ 65 years: OR(95%CI) = 1.33(1.07 – 1.67); Chronic LBP Overall: OR(95%CI) = 1.70(1.37 – 2.11), 50-64 years: OR(95%CI) = 1.38(0.98 – 1.95), ≥ 65 years: OR(95%CI) = 1.87(1.43 – 2.44) |

0.86 |

| Occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

|

Anita et al. 2019 [71] Spain |

Born between 1940 and 1966 (> 50 years) Sample size = 1059 Average: age = 56.7(7.1), BMI – LBP = 27.1(5.4), No LBP = 27.1(4.2) %Female: 55% |

Occupational – Workplace sitting Self-reported |

LBP – 1-month prevalence %prevalence = 14.2% Self-reported |

Multivariate regression Adjusted for age, sex, depression/anxiety level |

No association of workplace sitting with LBP OR(95%CI) = 0.28(0.05 – 1.38), p = 0.12 |

0.77 |

| Occupational and Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

|

Bento et al. 2019 [72] Brazil |

All adults Sample size = 600 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 50% |

Occupational—Workplace sitting; and Non-occupational—Sedentary behaviours (time spent on TV, on a computer, and/or video games) Self-reported |

LBP – Point prevalence %Prevalence: 28.8% Self-reported |

Poisson regression Adjusted for age, education, ethnicity, income, smoking, physical activity, depression, hypertension, diabetes, gastrointestinal, renal, and respiratory diseases |

No associations od sedentary behaviours nor workplace sitting with LBP TV time ≥ 3 h: Female PR = 0.96(95%CI = 0.31 – 1.71); Male PR(95%CI) = 1.06(0.68 – 1.65); Computer/video game ≥ 3 h: Female PR(95%CI) = 0.70(0.37 – 1.31); Male PR(95%CI) = 0.52(0.24 – 1.14). Sitting position at work (Always/usually): Female PR(95%CI) = 1.24(0.90 – 1.72); Male PR(95%CI) = 0.88(0.56 – 1.38) |

0.86 |

|

Dos Santos et al. 2017 [73] Brazil |

All adults Sample size = 600 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 50% |

Occupational – Workplace sitting; and Non-occupational – sedentary behaviours (time spent on TV, on a computer, and/or playing video games) Self-reported |

Neck pain – 12-month prevalence %prevalence: 20.3% Self-reported – NMQ |

Poisson regression to calculate prevalence ratio with a confidence interval Adjusted for gender |

No associations of workplace sitting, TV time, and computer time with neck pain Sitting position (Always/usually): PR = 1.09(95%CI = 0.78 – 1.52); TV time > 3 h: PR = 0.89(95%CI = 0.64 – 1.23); Computer time > 3 h: PR = 1.20(95%CI = 0.71 – 2.02) |

0.77 |

| Study design – case–control | ||||||

| Occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

|

Pope et al. 2003 [74] UK |

All adults Sample size = 3385 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR, %Female: Cases = 63.6; Control = 49.4 |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 2 h without a break) Self-reported |

Hip pain – 1-month prevalence %Prevalence: 10.5% Self-reported |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, sex, and all physical activities |

Positive association of prolonged sitting with hip pain Sitting for prolonged periods – ≥ 2 h: (higher exposure vs not exposed): OR(95%CI) = 1.82(1.13 – 2.92) |

0.91 |

| Study design – prospective | ||||||

| Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

|

Balling et al. 2019 [75] Denmark |

All adults Duration: mean 7.4-years Sample size = 46,826 Average: age = 47.6(15.8), BMI = 24.8(4.2) %Female: 60.3% |

Non-occupational – Total SB (sitting time) Self-reported – IPAQ |

LBP – Incidence %Incidence: 3.8% Medical records |

Cox regression Adjusted for age, sex, mental disorder, education, smoking status, BMI, leisure-time physical activity, and physical activity at work |

No association of total SB (sitting) with an incidence of LBP Sitting 6 to < 10 h: HR(95%CI) = 0.99(0.89 – 1.10); 10 + hrs: HR(95%CI) = 0.99(0.86 – 1.16) |

0.95 |

|

Chang et al. 2020 [76] USA |

45 – 79-years at baseline Duration: 8-year Sample size = 1194 Average: age = 58.4(8.9), BMI = 26.8(4.5) %Female: 58.4% Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) |

Non-occupational – Extensive sitting behaviour over 8 years Self-reported |

Knee pain – 12-month incidence %Incidence: 13.0% Clinical diagnosis – radiologic examination |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, depressive symptoms, comorbidities |

No association of extensive sitting trajectory with incident knee osteoarthritis Moderate frequency sitting trajectory: RR(95%CI) = 1.02(0.88 – 1.18); High frequency sitting trajectory: RR(95%CI) = 1.22(1.00 – 1.50) |

0.95 |

|

da Silva et al. 2019 [77] Australia |

All adults Duration: 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-ups Sample size = 250 Average: age = 50(15), BMI: 26.5(5.3) %Female: 50% |

Non-occupational – Total SB Self-reported |

LBP – Incidence %Incidence: 38% at 3-months; 56% at 6-months; and 69% at 12-months Self-reported – 11-point numerical rating scale |

Cox regression – completeness of follow-up was calculated using the completeness index Adjusted for age BMI, smoking, and exposure to heavy load |

Positive association of sitting time with LBP Sitting > 5 h: HR(95%CI) = 1.50(1.08 – 2.09), p = 0.02 |

0.73 |

|

Hussain et al. 2016 [78] Australia |

All adults Duration: 5-, 12-years Sample size = 4974 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 55.8% Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle (AusDiab) Study |

Non-occupational – TV time Self-reported |

LBP intensity, LBP disability – 6-month prevalence %Prevalence: 81.9% Self-reported – Chronic Pain Grade Questionnaire (CPGQ) |

Multinomial logistic regression Adjusted for age, education, smoking status, dietary guideline index score, and BMI; SF-36 MCS score |

High levels of TV time are positively associated with an increased risk of LBP disability in women but not in men. No association of TV time with LBP intensity TV time ≥ 2 h: LBP intensity (Men) Low: OR(95%CI) = 1.15(0.91 – 1.46), p = 0.25; High: OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.86 – 1.59), p = 0.31; (Women) Low: OR(95%CI) = 1.11(0.88 – 1.40), p = 0.37; High: OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.88 – 1.56), p = 0.28; LBP Disability (Men) Low: OR(95%CI) = 1.10(0.84 – 1.43), p = 0.50; High: OR(95%CI) = 1.15(0.82 – 1.61), p = 0.42; (Women) Low: OR(95%CI) = 1.35(1.04 – 1.73), p = 0.02; High: OR(95%CI) = 1.29(1.01 – 1.72), p = 0.04 |

0.82 |

|

Stefansdottir & Gudmundsdottir, 2017 [17] Iceland |

All adults Duration: 5-years Sample size = 737 Average: age = 53(16), BMI = 27(5) %Female: 39% Health and Wellbeing of Icelanders survey |

Non-occupational – Total SB Self-reported |

General musculoskeletal symptoms – 5-year prevalence %Prevalence: 33.5% Self-reported |

Not reported |

Positive association of total SB with general MSP High SB: OR(95%CI) = 1.7(1.03 – 2.83) |

0.50 |

| Occupational Sedentary Behaviour | ||||||

| Martin et al. 2013 [79]UK |

36-year, 43-year, and 53-year old cohorts Duration: Since birth in 1946 Sample size = 2957 Average BMI: 36-year = 24.1(3.7), 43-year = 25.4(4.2), 53-year = 27.4(4.8) %Female: 36-year = 51.3%, 43-year = 51.3%; 53-year = 50.7% |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (> 2 h) Self-reported |

Knee pain (Osteoarthritis) – 1-month prevalence %Prevalence: 10.2% Self-report and clinical examination |

Logistic regression Adjusted for gender, health risk factors, and socioeconomic position |

Negative association of workplace with knee osteoarthritis in women, but no association in men Sitting highly likely: (Men) 36 years OR(95%CI) = 1.13(0.61 – 2.06), p = 0.700; 43 years OR(95%CI) = 0.69 (0.39 – 1.24), p = 0.226; 53 years OR(95%CI) = 0.60 (0.34 – 1.07), p = 0.085; (Women) 36 years OR(95%CI) = 0.56 (0.33 – 0.94), p = 0.029; 43 years OR(95%CI) = 0.57 (0.36 – 0.89), P = 0.013; 53 years OR(95%CI) = 0.89 (0.56 – 1.43), p = 0.653 |

0.91 |

NR: Not reported, (M)NMQ: (Modified) Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire, TV: Television-viewing

Table 2.

Characteristics of the observational occupational cohort studies

| Study ID + Country | Study population + Duration + Sample size + Average age/ BMI + %Female + Study name | Nature of occupation | Sedentary behaviour (SB) domain + measures | Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions + % Prevalence + Measures | Statistical analysis + Adjusted covariates | Conclusions on associations of SB with MSP conditions + Effect Size/p-value | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design – cross-sectional | |||||||

| Occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Ayanniyi et al. 2010 [80] Nigeria |

All adults Sample size = Computer users = 236; Non-computer users = 236; Total = 472 Average: age – Computer users = 29(4.87), Non-computer users = 31(6.23); BMI = NR %Female: Computer users = 42.4%; Non-computer users = 42.4% |

Office workers |

Occupational – Computer time Self-reported |

Musculoskeletal symptoms (Neck/shoulder pain, UBP, elbows, wrists/hands, LBP, hips/thighs, knees, and ankles/feet pain) – 7- and 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 7 days point prevalence – Computer users = 55.9%, Non-computer users = 27.5%; 12-months prevalence – Computer users = 93.2%, Non-computer users = 33.9% Self-reported |

Regression analysis Adjusted for age, sex, marital status |

Positive association of computer time with musculoskeletal symptoms 7-day prevalence: 2–4 h – OR = 1.36(95%CI = 0.92 – 1.68, p < 0.05); > 4 h – OR = 4.12(95%CI = 3.21 – 5.16, p < 0.05); 12-Month prevalence: 2–4 h – OR = 3.25(95%CI = 1.84 – 4.73, p < 0.05); > 4 h – OR = 5.04(95%CI = 3.66 – 6.33, p < 0.05) |

0.73 |

|

Benyamina et al. 2018 [81] Canada |

All adults Sample size = 2208 Average: age = 35.8(8.1), BMI = NR %Female: 31.1% |

Professionals – Car-patrol police officers |

Occupational –vehicle time (time spent sitting in a vehicle) Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: Chronic LBP = 28.1%, acute/subacute LBP = 40.7% Self-reported – NMQ |

Multinomial regression Adjusted age, sex, country of birth, income, the region of residency, depressed mood, and anxiety |

No association of vehicle time with LBP Acute/subacute LBP vs No-LBP: OR(95%CI) = 1.005 (0.998 – 1.012), p = 0.169; Chronic LBP vs No-LBP: OR(95%CI) = 1.002 (0.993 – 1.010), p = 0.702 |

0.77 |

|

Cagnie et al. 2007 [82] Belgium |

All adults Sample size = 512 Average: age = NR, BMI = 24.0(3.4) %Female: 41.7% |

Office workers |

Occupational – prolonged workplace sitting and computer time (> 4 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck pain – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 45.5% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, mental tiredness, and sport |

Positive associations of prolonged workplace sitting and computer time with neck pain Workplace sitting: OR(95% CI) = 2.06(1.17 – 3.62); Computer time: OR(95% CI) = 1.57(1.10 – 2.22) |

0.73 |

|

Celik et al. 2018 [83] Turkey |

All adults Sample size = 528 Average: age = 38.55(9.79), BMI = 25.44(3.85) %Female: 51.14% |

Office workers |

Occupational – Total workplace sitting [mean = 4.64(2.21) Self-reported |

LBP, UBP, Shoulder pain, Neck pain, Leg pain, Arm pain, Foot pain, Wrist pain %Prevalence: LBP – Female = 60.4%, Male = 49.6%; UBP – Female = 62.6%, Male = 43.0%; Shoulder pain – Female = 50.0%, Male = 31.0%; Neck pain – Female = 61.9%, Male = 42.6%; Leg pain – Female = 39.6%, Male = 26.7%, Arm pain – Female = 33.0%, Male = 20.5%; Foot pain – Female = 45.6, Male = 37.2%; Wrist pain – Female = 33.7%, Male = 19.0% Self-reported |

Multiple-linear regression Adjusted for age, BMI, marital status, exercise in daily life, working experience |

No significant association of workplace sitting with LBP, UBP, shoulder and wrist pain. Negative association of workplace sitting with neck and extremities pain (arm, leg, and foot) in females LBP: Female B = –0.07, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.16–0.00, p = 0.080; Male B = –0.03, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.13–0.05, p = 0.458; UBP: Female B = –0.00, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.09–0.07, p = 0.825; Male B = 0.06, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.03–0.15, p = 0.195; Neck pain: Female B = –0.110, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.20–(–0.02), p = 0.009; Male B = 0.04, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.04–0.13, p = 0.352. Shoulder pain: Female B = –0.02, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.10–0.06, p = 0.648; Male B = 0.01, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.06–0.10, p = 0.711; Leg pain: Female B = –0.08, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.170–0.000, p = 0.043; Male B = –0.01, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.11–0.07, p = 0.687; Foot pain: Female B = –0.09, SE = 0.040, 95%CI = –0.18–(–0.01), p = 0.027; Male B = 0.00, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.07–0.08, p = 0.891; Arm pain: Female B = –0.10, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.18–(–0.02), P = 0.010; Male B = 0.00, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.07–0.08, p = 0.919; Wrist pain: Female B = –0.04, SE = 0.04, 95%CI = –0.12–0.04, p = 0.343; Male B = 0.03, SE = 0.03, 95%CI = –0.03–0.11, P = 0.292 |

0.73 |

|

Chee & Rampal 2004 [84] Malaysia |

All adults Sample size = 906 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 100% |

Tradespeople – Semiconductor factory workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 4 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck/shoulder pain, and lower limbs – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 80.5% Self-reported – NMQ |

Multivariate binary logistic regression Adjusted for age, work task, work schedule, overtime work, whether work environment was too cold, and stress |

Positive association of workplace sitting with neck/shoulder pain [OR(95% CI) = 1.6(1.2 – 2.1)]; a negative association with Lower limbs OR(95% CI) = 0.5(0.4 – 0.8) | 0.91 |

|

Chrasakaran et al. 2003 [85] Malaysia |

All adults Sample size = 529 Average: age = 31.2(7.4), BMI = NR %Female: 100% |

Tradespeople –Semiconductor factory workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 4 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck, shoulder, arm (elbow and forearm), wrist and fingers, upper leg (hips/thighs/knees), lower leg (ankles/feet) – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: lower leg (48.4%), shoulder (44.8%), upper leg (38.8%) and neck (29.7%) Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, number years of work, the stress of work, cold working temperature |

Positive association of workplace sitting with NSP, but no association with extremities pain Neck: [OR(95% CI) = 2.1(1.3 – 3.2); Shoulder: [OR(95% CI) = 1.7(1.2 – 2.5); Upper leg: [OR(95% CI) = 0.6(0.3 – 1.0); Lower leg: [OR(95% CI) = 0.6(0.4 – 1.0) |

0.73 |

|

Constantino et al. 2019 [86] Brazil |

All adults Sample size = 530 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 95.4% |

Professionals – Teachers |

Occupational – workplace sitting (≥ 2 h/day), computer time(≥ 2 h/day); and Non-occupational – TV time(≥ 2 h/day) Self-reported |

Clinically diagnosed MSP disease; musculoskeletal symptoms (back/neck); and MSP-related disability – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: > 30% Self-reported – NMQ |

Poisson regression Adjusted for age, gender, length of employment, high stress, common mental disorder, physical activity |

Negative association of workplace sitting with lower limbs disability [Adjusted PR(95%CI) = 0.64(0.43–0.94)]; No association of TV time with back & neck pain [Adjusted PR(95%CI) = 1.03(0.88–1.21)]; Positive association of TV time with clinically diagnosed MSP disease [Adjusted PR(95%CI) = 1.37(1.02–1.85)]; No association of computer time with clinically diagnosed MSP disease [Adjusted PR(95%CI) = 0.78(0.60–1.02)] | 0.77 |

|

Dianat & Karimi, 2016 [87] Iran |

All adults Sample size = 632 Average: age = 34.5(11.5), BMI = 24.9(4.1) %Female: 58.9% |

Tradespeople – Handicraft workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (> 2 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck, shoulders, LBP –1-month prevalence %Prevalence: 76.2% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, marital status, education level, smoking, physical activity, years working |

Positive association of workplace sitting > 2 h with neck pain in multivariate analysis [OR(95% CI) = 2.85(1.79 – 4.53), p < 0.001] Univariate analysis showed a positive association of workplace sitting with shoulder pain [OR(95% CI) = 1.54(1.02 – 2.31)];and no association with LBP [OR(95% CI) = 0.99(0.66 – 1.47)] |

0.86 |

|

Dianat et al. 2015 [88] Iran |

All adults Sample size = 251 Average: age = 33.2(9.9), BMI: 24.1(4.1) %Female: 39.8% |

Tradespeople – Sewing machine operators |

Occupational – workplace sitting (> 2 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck, shoulders, UBP, LBP, elbows, wrists/hands, hips/thighs/buttocks, knees, and ankles/feet – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 9.6% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for demographic (age, gender, BMI, educational level, marital status, smoking, physical activities, and job characteristics, and RULA scores |

Positive association of workplace sitting > 2 h with neck pain [OR(95% CI) = 3.34(1.40 – 7.95), p = 0.006]; and shoulder pain [OR(95% CI) = 3.12(1.19 – 8.18), p = 0.020] in multivariate analysis However, univariate analysis showed no association of workplace sitting with LBP [OR(95% CI) = 1.12(0.41 – 2.99), p = 0.821], and UBP [OR(95% CI) = 1.04(0.93 – 1.16), p = 0.102]; but positive association with Hand/wrist [OR(95% CI) = 2.49(1.08 – 5.72), p = 0.031] |

0.86 |

|

Ilic et al. 2021 [89] Serbia |

Young to middle-aged Sample size = 499 Average: age = 22.0(2.2) %Female: 67.7% |

Professionals – Students |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (prolonged sitting) Self-reported |

LBP – Point prevalence %Prevalence: 20.8% Self-reported |

Logistic regression Adjusted for smoking, BMI, Incorrect body posture, stress, incorrect sitting position, family history of LBP |

Multivariate analysis: No association of prolonged sitting with LBP [OR (95%CI) = 1.5(0.5 – 4.2), p = 0.424 Univariate analysis – prolonged sitting associated with LBP (p = 0.018) |

0.82 |

|

Hakim et al. 2017 [90] Egypt |

All adults Sample size = 180 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 0% |

Bus divers |

Occupational – vehicle time (> 8 h/day) Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 73.9% Self-reported – NMQ |

Binary logistics regression Adjusted for age, BMI, marital status, education, smoking, work duration |

Positive association of vehicle time (> 8 h) with LBP OR(95%CI) = 2.93(1.45 – 5.93) |

0.68 |

|

Larsen et al. 2018 [91] Sweden |

All adults Sample size = 4114 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 25.8% |

Professionals – Duty police officer |

Occupational – Vehicle time (% shift time sitting: 25 – 50%, 50 – 75%, > 75%) Self-reported |

Multisite MSP (pain in two or more body regions) – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: 41.3% Self-reported – 5-point scale |

Binominal logistic regression.; adjusted for age, sex, physical exercise, physical workload factors, and psychosocial factors |

Vehicle time vehicles were not significantly associated with multi-site MSP among police Shift time sitting: 25 – 50% OR(95%CI) = 0.97(0.74 – 1.28); 50 – 75% OR(95%CI) = 1.11(0.84 – 1.47); > 75% OR(95%CI) = 1.10(0.77 – 1.57) |

0.86 |

|

Lourenço et al. 2015 [92] Portugal |

21-year cohorts Sample size = 1733 (Non-workers = 1083; Workers = 650) Average BMI = NR %Female: Non-workers = 51.8%; Workers = 51.2% Epidemiological Health Investigation of Teenagers in Porto (EPI-Teen) |

Professionals – Student |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (> 4.2 h/week); computer time (> 5.0 h/week) Self-reported |

Neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists/hands, upper back, lower back, hips/thighs/buttocks, knees, and ankles/feet – 12-month prevalence Self-reported |

Logistic regression Adjusted for sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking, education, and job strain (Karasek’s Job Strain Model) |

A positive association of workplace sitting with LBP [OR(95%CI) = 1.70(1.20 – 2.42)]; no association with neck pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.23(0.89 – 1.71)] and extremities pain [OR(95%CI) = 0.83(0.60 – 1.16)] | 0.91 |

|

Mehrdad et al. 2012 [93] Iran |

All adults Sample size = 405 Average: age = 44.6 (7.9), BMI: 23.7(2) %Female: 47% |

Professionals – physicians |

Occupational – Prolonged workplace sitting (> 20 min) Self-reported |

Neck paina – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 41.7% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for both individual and work-related factors such as age, gender, BMI, shift work, type of employment, and secondary job |

A positive association of prolonged workplace sitting with neck pain Coefficient(B) = 0.204, OR(95%CI) = 1.227(1.032 – 1.458), p = 0.020 |

0.86 |

|

Omokhodion et al. 2003 [94] Nigeria |

All adults Sample size = 840 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 43% |

Office workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (> 3 h) Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 37.5%; Self-reported |

Not reported | Workplace sitting for > 3 h associated with increased severity of LBP | 0.36 |

|

Pradeepkumar et al. 2020 [95] India |

24 – 55 years Sample size = 301 Average: age = 39(7.3), BMI = NR %Female: NR |

Bus drivers |

Occupational – Vehicle time (Prolonged sitting) Self-reported |

MSP conditions – 7-day and 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 55.8%; Self-reported – NMQ |

Chi-square test |

Prolonged sitting in a vehicle is positively associated with the risk of MSP conditions χ2 = 5.833, p < 0.05 |

0.55 |

|

Ratzon et al. 2000 [96] Israel |

All adults Sample size = 60 Average: age = 46.0 (8.66), BMI – Sitting position = 25.14(2.18), Alternating position = 25.31(2.44) %Female: 0% |

Professionals – Dentist |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 80% of work time) Self-reported |

General MSP, LBP – 7-days and 12-month prevalence %Prevalence; Low back pain = 55% Self-reported – NMQ |

Pearson and Spearman correlations |

Sitting position at work positively and significantly correlated with LBP Correlation coefficient – MSP = − 0.16; LBP: r = 0.41, p < 0.01 |

0.45 |

|

Şimşek et al. 2017 [97] Turkey |

All adults Sample size = 1682 Average: age = 37.9(7.46), BMI: NR %Female: 60% |

Professionals – Healthcare workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (> 4 h), computer time (> 4 h) Self-reported |

LBP – 7-days, 12-month, and lifetime prevalence %Prevalence: Lifetime prevalence 53%, 12-month prevalence 39% and 7-days prevalence 29.5% Self-reported – NMQ (10-cm-long Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)) |

Binary logistic regression Adjusted for sex, BMI, marital status, smoking habit, physical exercise, job satisfaction, workplace stress |

Positive associations of workplace sitting and computer time > 4 h with LBP Workplace sitting time: OR(95%CI) = 4.7(1.25 – 17.64), p = 0.021; Computer time: OROR(95%CI) = 0.0(0.00 – 0.04), p = 0.0001 |

0.86 |

|

Spyropoulos et al. 2007 [98] Greece |

All adults Sample size = 648 Average: age = 44.5, BMI = NR %Female: 75.8% |

Office workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 6 h) Self-reported |

LBP – Lifetime prevalence %Prevalence: Lifetime 61.6% Self-reported – Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and physical examination by a physiotherapist |

Multiple logistic regression Adjusted for age gender, BMI, psychosocial factors |

Positive association of workplace sitting time > 6 h with lifetime LBP OR(95z5CI) = 1.588(1.064 – 2.368) |

0.82 |

|

Szeto & Lam, 2007 [99] Hong Kong |

All adults Sample size = 481 Average: age = NR, BMI – Male = 25.24(3.42); Female = 23.60(2.74) %Female: 16% |

Bus drivers |

Occupational – Vehicle time (prolonged sitting) Self-reported |

LBPa – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 92.7% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, company |

Positive association of prolonged vehicle time with LBP OR(95% CI) = 3.71(2.40 – 5.74) |

0.77 |

|

Temesgen et al. 2019 [100] Ethiopia |

All adults Sample size = 754 Average: age = 42(9.73), BMI = NR %Female: 57.8% |

Professionals – Teachers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (prolonged sitting > 4 h/day) Self-reported |

Neck/shoulder pain – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 57.3% Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistics regression Adjusted for age, marital status, salary, smoking, alcohol, physical exercise, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory diseases |

Positive association of prolonged workplace sitting > 4 h with neck/shoulder pain OR(95%CI) = 1.50(1.02 – 2.23) |

0.95 |

|

Tsigonia et al. 2009 [101] Greece |

All adults Sample size = 102 Average: age = 38.42(10.74), BMI = 23.09(2.86) %Female: 93% |

Tradespeople – Cosmetologists |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (High exposure to prolonged sitting – often or always) Self-reported |

Neck, shoulder, hand/wrist, low back, knee; 12-month prevalence; %Prevalence: Neck = 58%; shoulder = 35%; hand/wrist = 53%; low back = 53%; knee = 28%; Self-reported– NMQ | Logistics regression; adjusted for age and sex |

Positive association of high exposure to prolonged workplace sitting with hand/wrist complaints, OR(95%CI) = 55.7(18.75- 354.93) Univariate analysis indicates workplace sitting is significantly related to the occurrence of LBP, neck/shoulder pain, hand and knee pain (both acute and chronic complaints) |

0.73 |

|

van Vuuren et al. 2005 [102] South Africa |

All adults Sample size = 366 Average: age = 31.76(7.80), BMI = NR %Female: NR |

Tradespeople – Steel plant workers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (sitting position half the time or more) Self-reported |

LBP, LBP disability – Point, 1-month, 12-month, and lifetime prevalence %Prevalence: Point 35.8%, 1-month 41.3%, 12-month 55.7%, and lifetime 63.9%; LBP disability – ≥ 30% Self-reported – Functional Rating Index (FRI) |

Multivariate logistic regression Adjusted for all risk factors including work organization, trunk posture, handling activities, body position, and environmental demands |

Positive association of workplace sitting with LBP, but no significant association with LBP disability LBP: [OR(95%CI) = 2.33(1.01 – 5.37)]; LBP disability: [OR(95%CI) 1.89(0.75 – 4.78)] |

0.77 |

|

Yue et al. 2012 [103] China |

All adults Sample size = 893 Average: age = 32.21(10.6), BMI = 39(2.79) %Female: 67% |

Professionals – Teachers |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 4 h/day); Computer time (≥ 4 h/day) Self-reported |

LBP, neck/shoulder pain – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: LBP = 45.6%, NSP = 48.7% Self-reported – NMQ |

Binary logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education, smoking, exercise, years of work, duration of work |

Positive association of prolonged workplace sitting (≥ 4 h) with neck/shoulder pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.76(1.23 – 2.52)] and LBP[OR(95%CI) = 1.42 (1.01 – 2.02)] No significant association of computer time (≥ 4 h) with neck/shoulder pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.02 (0.63 – 1.65)] and LBP [OR(95%CI) = 0.71 (0.44 – 1.14)] |

0.86 |

| Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Ben-Ami et al. 2018 [104] Israel |

All adults Sample size = 1026 Average: age = 27.2(6.4), BMI = NR %Female: 57.7% |

Professionals – Students |

Non-occupational – Leisure-time SB (at least half an hour a day) Self-reported |

LBP – 6-month prevalence %Prevalence: 38.6% Self-reported |

Multinominal logistic regression Adjusted for sociodemographic, lifestyle, and personal vulnerability |

No significant association of total SB with LBP (backache) AOR(95%CI) = 0.96(0.78 – 1.18) |

0.86 |

|

Hildebrandt et al. 2000 [56] Netherlands |

All adults Sample size = 2030 Average: age = 33.7(9.6), BMI: NR %Female: 51% |

Tradespeople – Industry (shipyard, metal, transport) and services (cleaners, childcare); Professionals – Healthcare(nurses); and Office workers |

Non-occupational – Leisure-time SB Self-reported |

LBP, neck/shoulder pain, and lower extremity pain – 12-prevalence %Prevalence: LBP = 60%, NSP = 44%, and lower extremity pain = 31% Self-reported |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, education, and type of workload |

Leisure-time SB is positively associated with LBP [OR(95%CI) = 1.46(1.18 – 1.29)]; and no associated with neck/shoulder pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.02(0.82 – 1.27)], and lower extremities pain [OR(95%CI) = 1.07(0.85 – 1.36)] | 0.73 |

|

Ibeachu et al. 2019 [105] UK |

18 – 39 years Sample size = 314 Average: age = 22.0(5.2), BMI = 24.3(4.1) %Female: 43.9% |

Professionals – Student |

Non-occupational – Total SB (mean 5.6(2.6)hrs/day) Self-reported – IPAQ |

Knee pain – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 31.8% Self-reported – Knee Pain Screening Tool (KNEST) |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, mental distress |

Total SB has a borderline non-significant association with knee pain (p = 0.069) Quadratic term: OR(95%CI) = 1.02(1.00 – 1.05) Linear term: OR(95%CI) = 1.04 (0.93 – 1.16) |

0.82 |

|

Rodríguez-Nogueira et al. 2021 [106] Spain |

All adults Sample size = 472 Average: age – Male = 48.1(10.9); Female = 45.3(11.2) %Female: 60% |

Professionals – University staff |

Non-occupational – Daily sitting time (Mean daily sitting time (hrs): Male = 7(2.5); Female = 6.9(2.3)) Self-reported |

General MSP – 12-month prevalence Self-reported – NMQ |

Logistic regression Adjusted for age, sex, anxiety, physical activity, self-perceived stress |

No significant association of daily sitting with general MSP OR(95%CI) = 0.934(0.86 – 1.01), p = 0.09 |

0.86 |

|

Sklempe et al. 2019 [107] Croatia |

Young adults Sample size = 517 Average: age – 20(2), BMI = 22.3(4.3) %Female: 63.8% |

Professionals – Student |

Non-occupational – Total SB (mean 5(3.5)hrs/day) Self-reported – IPAQ |

Musculoskeletal symptoms (neck, shoulder, upper back, and lower back) – 12-month prevalence %Prevalence: 81% Self-reported – NMQ |

Point-biserial correlation coefficient | No significant association between the time spent sitting and MSP score | 0.73 |

|

Tavares et al. 2019 [108] Brazil |

Young to middle-aged adults Sample size = 629 Average: age – median(IQR) = LBP = 22.5(21.0 – 24.0); no LBP = 23.0(21.0 – 25.0); Average BMI = NR %Female: 72.8% |

Professionals – Student |

Non-occupational – Total SB Self-reported |

LBP – Lifetime prevalence; %Prevalence: 81.7%; Self-reported | Chi-squared test | No association of total SB with LBP | 0.59 |

| Occupational and Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Gupta et al. 2015 [109] Denmark |

All adults Sample size = 201 Average: age = 44.7(9.7), BMI = 26.4 (5.0) %Female: 41.8 |

Tradespeople – Construction workers, cleaners, garbage collectors, manufacturing workers, assembly workers, mobile plant operators, and workers in the health service sector |

Occupational – Total workplace sitting (low: ≤ 2.0 h, moderate: 2.1 – 3.7 h, high: > 3.7 h); and non-occupational – Total full day sitting (low: ≤ 6.4 h, moderate: 6.5 – 8.3 h and high: > 8.3 h); Total leisure-time sitting (Low: < 4.4 h, moderate: 4.0 – 5.4 h, high: > 5.4 h Device-measured – ActiGraph |

LBP intensity – 1-month prevalence Low intensity: ≤ 5 pain score; high intensity: > 5 pain score Self-reported – NMQ |

Binary logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and smoking, job seniority, influence at work, and occupational lifting/carrying time at work |

Positive associations of the total full day sitting time and leisure-time with LBP intensity, and marginally significant association of total workplace sitting with LBP intensity Total full day sitting: OR = 1.43(1.15 – 1.77), p = 0.01; Workplace sitting: OR = 1.34(0.99 – 1.82), p = 0.06; Leisure sitting: OR = 1.45(1.10 – 1.91), p = 0.01. High total full day sitting: OR = 3.31(1.18 – 9.28), p = 0.03; High Workplace sitting: OR = 3.26(0.89 – 11.98), p = 0.08; High Leisure sitting: OR = 5.31(1.57 – 17.90), p = 0.01 |

0.95 |

|

Hallman et al. 2015 [110] Denmark |

All adults Sample size = 202 Average: age = NR, BMI = NR %Female: 41.8% Danish PHysical ACTivity cohort with Objective measurements (DPHACTO) |

Tradespeople – Construction workers, cleaners, garbage collectors, manufacturing workers, assembly workers, mobile plant operators, and workers in the health service sector |

Occupational – Mean total workplace sitting = 3.0(1.4); and Non-occupational – mean total full day sitting = 7.3 (2.1), mean total leisure-time sitting = 4.8(1.7) Device-measured – ActiGraph |

Neck/shoulder pain-intensity – 1-month prevalence %Prevalence: 75.2% Self-reported – NMQ (numeric rating scale (NRS)) |

Logistic regression Adjusting for age and gender, individual factors (i.e., BMI and smoking), work-related factors (i.e., seniority, influence at work, and lifting/carrying) |

Positive associations of the total full day sitting and workplace sitting with neck/shoulder pain intensity. Low total workplace sitting is associated with reduced neck/shoulder pain intensity in men. No association of leisure-time sitting with neck/shoulder pain intensity Total full day Sitting: High sitting (Overall) OR(95%CI) = 2.97(1.25 – 7.03), p = 0.01; (Male) OR(95%CI) = 6.44(1.76 – 23.56), p = 0.005; (Female) OR(95%CI) = 1.19(0.31 – 4.51), p = 0.44. Workplace sitting: High sitting (Overall) OR(95%CI) = 0.92(0.41 – 2.06), p = 0.83; (Male) OR(95%CI) = 0.94(0.31 – 2.85), p = 0.92; (Female) OR(95%CI) = 1.17(0.32 – 4.33), p = 0.82; Low sitting (Overall) OR(95%CI) = 0.54(0.23 – 1.25), p = 0.15; (Male) OR(95%CI) = 0.26(0.07 – 0.96), p = 0.04; (Female) OR(95%CI) = 1.01(0.28 – 3.59), p = 0.99. Leisure-time: High sitting (Overall) OR(95%CI) = 1.60(0.68 – 3.74) p = 0.28; (Male) OR(95%CI) = 2.76(0.83 – 9.18), p = 0.097; (Female) OR(95%CI) = 1.02(0.28 – 3.74), p = 0.97 |

0.91 |

|

Hallman et al. 2016 [111] Denmark |

All adults Sample size = 659 Average: age = 45.0(9.9), BMI = 27.5(4.9) %Female: 44.9% DPHACTO |

Tradespeople – Cleaning, manufacturing, transport |

Occupational –workplace sitting pattern and absolute sitting time (brief: < 5 min, moderate: > 5 – 20 min, prolonged: > 20 min) and Non-occupational –leisure-time sitting pattern and absolute sitting time (brief: < 5 min, moderate: > 5 – 20 min, prolonged: > 20 min) Device-measured – ActiGraph |

Neck/shoulder pain-intensity – 3-month prevalence %Prevalence: 74% Self-reported – NMQ [numeric rating scale (NRS)] |

Binary logistic regression Adjusted for age, gender, smoking, BMI, job seniority, lifting/carrying time at work, physical activity at work, and leisure, sitting with arms above 90° |

Negative association of short workplace sitting bout with neck/shoulder pain intensity and positive association with moderated workplace sitting bout with neck/shoulder pain intensity. No association of prolonged Workplace sitting bout nor leisure-time sitting bouts with neck/shoulder pain intensity Workplace sitting bout: Brief Coefficient (B) = -0.38, OR(95%) = 0.60(0.40 – 0.91), p = 0.04; Moderate B = 0.28, OR(95%CI) = 1.23(0.93 – 1.63), p = 0.02; Prolonged B = − 0.08, OR(95%CI) = 0.84(0.69 – 1.02), p = 0.33. Leisure sitting bout: Brief B = 0.23, OR(95%CI) = 1.25(0.71 – 2.21), p = 0.44; Moderate B = 0.27, OR(95%CI) = 0.76(0.52 – 1.10), p = 0.15; Prolonged B = 0.11, OR(95%CI) = 0.90(0.71 – 1.14), p = 0.37 |

0.91 |

| Study design – prospective | |||||||

| Occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Hallman et al. 2016 [112] Denmark |

All adults Duration: 12-months Sample size = 625 Average: age = 44.8(9.8), BMI = 27.5(4.9) %Female: 45% DPHACTO |

Tradespeople – Cleaning, manufacturing, transport |

Occupational – Total workplace sitting [2.4(1.7)hrs] Device-measured – ActiGraph |

Neck/shoulder pain-intensity – 1-month prevalence (measured over 12 months) %Prevalence/incidence: 70%; mean pain score 3.1(2.7) Self-reported – Numerical rating scale (NRS) |

Linear mixed models Adjusted for age, gender, and BMI; occupational sector, lifting/carrying time at work, physical activity at and leisure, working with the dominant arm elevated > 60° |

Negative association of increased workplace sitting with neck/shoulder pain-intensity (i.e., reduced neck/shoulder pain-intensity) after 12-month follow-up in the Tradespeople Coefficient, B = 0.012, SE = 0.055, 95%CI = 0.000 – 0.025, p = 0.006 |

0.91 |

|

Korshøj et al. 2018 [39] Denmark |

All adults Duration: 12-months Sample size = 665 Average: age = 45.0(10.0), BMI = 27.4(4.9) %Female: 44.2% DPHACTO |

Tradespeople – Cleaning, manufacturing, transport |

Occupational – Total workplace sitting, sitting bout Device-measured – ActiGraph |

LBP-intensity – 3- and 12-month prevalence Mean pain score 3.1(2.7) Self-reported – Numerical rating scale (NRS), which ranges from 0 (‘no pain’) to10 (‘worst pain imaginable’) |

Linear mixed models Adjusted for herniated disc, occupational lifting and carrying, LBP the last 3 months from baseline, sitting time during leisure time |

Negative association of both total workplace sitting and temporal patterns of sitting (sitting bout) with LBP intensity across 12-month Total workplace sitting: Coefficient(B) = -0.050, SE = 0.007, p < 0.001, 95%CI = -0.065 – -0.040; Brief (bouts ≤ 5 min): B = -0.118, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001, 95%CI = -0.152 – -0.084; Moderate (bouts of > 5 − 20 min): B = -0.117, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001, 95%CI = -0.151 – -0.084; Prolonged (bouts of > 20 min): B = -0.123, SE = 0.018, p < 0.001, 95%CI = -0.158 – -0.088 |

0.95 |

|

Yip, 2004 [113] Hong Kong |

All adults Duration: 12 months Sample size = 144 Average0: age = 31.1, BMI = NR %Female: 85.5% |

Professionals – Nurses |

Occupational – Workplace sitting (≥ 2 h) Self-reported |

LBP – 12-month incidence %Prevalence: 56% Self-reported |

Chi-square test | No association of prolonged workplace sitting ≥ 2 h/day with the prevalence of LBP, p = 0.47 | 0.59 |

| Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Santos et al. 2020 [114] Brazil |

All adults Duration: 24-months Sample size = 978 at baseline Average: age – median age(IQR) Baseline = 42(34 – 49), Follow-up = 44(36 – 51); BM – median BMI(IQR) Baseline = 25.2(22.8 – 28.2), Follow-up = 25.6(23.2 – 28.6) %Female: 66.6% baseline Pro-Mestre study |

Professionals – Teachers |

Non-occupational – TV time Self-reported |

Chronic MSP – 6-month prevalence % Prevalence – baseline = 32.3%; follow-up = 24.7% Self-reported |

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and depression |

Positive association of change in TV time (30 min/day) with chronic MSP, OR(95%CI) = 1.051(1.001 – 1.102) |

0.95 |

|

Jun et al. 2020 [115] Australia, South Korea |

All adults Duration: 12-month Sample size = 214 (Australia – Brisbane = 156; South Korea – Daegu = 58) Average: age = 37.3(9.9), BMI = 24.0(4.2) %Female: 55.1% |

Office workers – University faculty members, research centre, management service, industrial institution |

Non-occupational – Total SB [total hours sitting in weekdays = 51.9(11.8)] Self-reported – IPAQ |

Neck pain – monthly prevalence for the 12-month %prevalence/incidence: 18.2% self-reported |

Survival analysis Adjusted for age, gender, and BMI |

Positive association of increased total SB during weekdays with increased risk of neck pain Adjusted HR(95%CI) = 1.04(1.03 – 1.06), p < 0.001 |

0.82 |

| Occupational and Non-occupational Sedentary Behaviour | |||||||

|

Lunde et al. 2017 [57] Norway |

All adults Duration: 6-month Sample size = 124 Average: age – Construction = 39.9(13.6), Health = 44.5(9.6); BMI – Construction = 25.7(3.3), Health = 25.1(3.8) %Female – Construction = 1.6%, Health = 77.8% |

Tradespeople – Construction; Professionals – Healthcare workers |

Occupational – Total workplace sitting (Construction = 156.8(114.2) Health = 171.6(93.8); and Non-occupational – Leisure-time sitting (Construction = 282.0(78.4); Health = 274.0(94.3)) Device-measured – ActiGraph |

LBP-intensity; 1-month prevalence %Prevalence: Health – Baseline = 59%; 6-month = 55%; Construction – Baseline = 52%; 6-month = 49%; mean pain score Baseline – Construction = 0.5(0.5); Health = 0.6(0.5); 6-months – Construction = 0.7(0.9); Health = 1.0(1.0) Self-reported |

Linear mixed models Adjusted for age, gender, smoking, body mass index, heavy lifting, forward bending at work, social climate, decision control, fair leadership, empowering leadership, sitting (minutes) during leisure time |

Total full day Sitting: Association of the total full day sitting with LBP-intensity in both healthcare and construction workers at baseline and 6-months Healthcare: Baseline – B(95%CI) = -0.16(-0.40 – 0.08), p = 0.183; 6-month – B(95%CI) = -0.17(-0.40 – 0.07), p = 0.168 Construction: Baseline B(95%CI) = -0.07(-0.31– 0.18), p = 0.596; 6-months – B(95%CI) = -0.08(-0.31– 0.17), p = 0.541 Workplace Sitting Healthcare workers – a negative association of workplace sitting with LBP intensity at baseline and 6-months’ follow-up Baseline: B(95%CI) = B(95%CI) = -0.31(-0.63 – 0.01), p = 0.058; 6-Month: B(95%CI) = -0.34(-0.66 – -0.02), p = 0.040 Construction workers – no associations of workplace sitting with LBP intensity Baseline: B(95%CI) = -0.00001(-0.35 – 0.35), p = 1.00; 6-Month: B(95%CI) = -0.003(-0.36 – 0.35), p = 0.986 |

0.95 |

aMeasured multiple MSP conditions but presented only the MSP condition that was reported in the study result NR: Not reported, NMQ: Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire, TV: Television-viewing,

Table 3.

Characteristics of the experimental/intervention of occupational cohort studies

| Study ID + Country | Study design + Time points + Sample size + Intervention | Study population + Average age/ BMI + %Female | Sedentary behaviour (SB) domain + measures | Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) conditions + Time points/% prevalence + Measures | Statistical analysis + Adjusted covariates | Conclusions on associations of SB with MSP conditions + Effect Size/p-value | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trial – RCT | |||||||

|

Benzo et al. 2018 [116] USA |

RCT Sample size = 15 Time points: 13 data points (minute 0, 10, 29, 60, 70, 89, 120, 130, 149, 180, 190, 209 and 240) – 4-h experiment |

All adults – Office workers Average: age – 36.7(5.5), BMI = 29.6(3.1) %Female: 13.3% |

Occupational – Sitting changes (sitting condition) |