Abstract

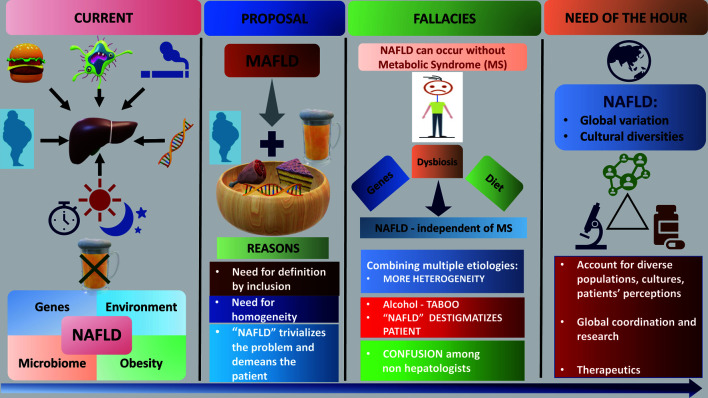

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects about a quarter of the world’s population and poses a major health and economic burden globally. Recently, there have been hasty attempts to rename NAFLD to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) despite the fact that there is no scientific rationale for this. Quest for a “positive criterion” to diagnose the disease and destigmatizing the disease have been the main reasons put forth for the name change. A close scrutiny of the pathogenesis of NAFLD would make it clear that NAFLD is a heterogeneous disorder, involving different pathogenic mechanisms of which metabolic dysfunction-driven hepatic steatosis is only one. Replacing NAFLD with MAFLD would neither enhance the legitimacy of clinical practice and clinical trials, nor improve clinical care or move NAFLD research forward. Rather than changing the nomenclature without a strong scientific backing to support such a change, efforts should be directed at understanding NAFLD pathogenesis across diverse populations and ethnicities which could potentially help develop newer therapeutic options.

Keywords: Heterogeneity, MAFLD, Metabolic, NAFLD, NASH, Nomenclature, Steatohepatitis

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Of late, there have been a plethora of articles supporting the change of nomenclature of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). In the face of such a vociferous campaign and the emanating din of MAFLD, one may very easily be led to think that this name change is a positive step in NAFLD research. There have been ‘consensus’ statements as well as a number of articles which have tried to emphasize upon the urgent requirement of this change of nomenclature.1–3 However, this proposed change of nomenclature is faulty and does not take into account several factors in NAFLD pathophysiology and also ignores the gamut of evidence garnered in NAFLD research to date. Besides, it is equally important to recognize the implications of a name change and its effects on both physicians and patients.4–6 In this review, we have tried to critically analyze the historical perspective of NAFLD, the origin of the term and the pathophysiological mechanisms involved, and deliberate whether a change in nomenclature is warranted.

History of NAFLD

‘Fatty liver’ is not a new term. Thomas Addison had described the presence of fatty liver in individuals who consumed alcohol in 1845.7 Fatty infiltration of the liver and the development of cirrhosis in diabetes and chronic alcoholism had been described by Connor in 1930.8 However, the histological features of NAFLD were first described in the late 1950s by Wastewater and Fainer,9 in persons who had no history of alcohol intake but had hepatic steatosis. In 1979, Klatskin, Miller and Ishimaru presented their landmark study at the plenary session of American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Annual Meeting, where they described the hepatic histological findings in 27 patients with typical features of alcoholic liver disease but with no history of alcohol intake, and labelled it as ‘non-alcoholic liver disease’.7 Perhaps, this was the point in time when the term ‘NAFLD’ had its humble beginnings. Similar findings were reported almost simultaneously by Adler and Schaffner,10 who categorized the patients on the basis of histopathological findings into ‘fatty liver, fatty hepatitis, fatty fibrosis and fatty cirrhosis’. Eight months later, Ludwig and his colleagues11 at Mayo clinic reported similar findings in a cohort of patients, which they named ‘non-alcoholic steatohepatitis’. Surprisingly, the MAFLD consensus statement makes no mention of these facts and states that the “….term non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was coined by Ludwig and colleagues in 1980…”1 Ludwig et al.11 coined the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in their 1980 article and never used the term NAFLD.

Not much was known about the pathophysiology of the entity at that point of time. In the course of time, it was evident that NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of disorders, ranging from simple steatosis to cirrhosis of the liver12 and a strong association between obesity, metabolic syndrome (MS) and NAFLD was established.13–15 However, it soon became obvious that this was an oversimplification and multiple factors were involved in NAFLD pathogenesis.16 Despite all the advances in our understanding of the causes of hepatic steatosis, the exact pathophysiologic mechanisms driving NAFLD have not been clearly defined and the search for the Holy Grail continues. With each passing day, a new player emerges and the adjective ‘key’ is thrust upon it!

Pathophysiology of NAFLD - The Six Blind Men of Indostan

“And so these men of Indostan, Disputed loud and long, Each in his own opinion, Exceeding stiff and strong, Though each was partly in the right, And all were in the wrong!”

The Blind Men and The Elephant—John Godfrey Saxe

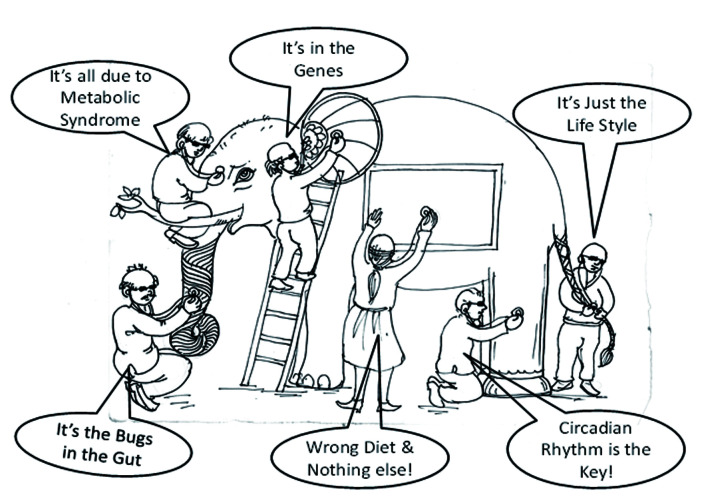

The pathophysiology of NAFLD is similar to the story of the six blind men and the elephant (Fig. 1). There have been numerous attempts to ascribe hepatic steatosis to a multitude of factors. It is generally accepted that NAFLD/NASH is commonly associated with insulin resistance (IR) or metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and dyslipidemia and has even been termed as the hepatic manifestation of the MS.17 However, given the complexity of the pathogenesis of NAFLD, it is difficult to explain the entire range of its manifestations by any single mechanism. We have explained in the following sections why it would be unscientific and illogical to ascribe the entire pathophysiology of NAFLD to MS. This attempt to change the nomenclature betrays a lack of complete understanding of the processes that go into the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Changing the name may neither reflect nor improve our understanding of ‘what causes' or ‘what leads to’ or ‘what happens to’ this entity.

Fig. 1. The different etiologies of NAFLD-described by different experts: No single factor can explain the whole spectrum of disease.

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Is NAFLD merely an extension of the MS?

Two questions are of paramount importance while analyzing the multiple factors involved in NAFLD pathogenesis. First, is MS ubiquitous in NAFLD and second, is the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH so linear? A careful look at the various factors causing NAFLD and the complex interplay therein, far from allaying our doubts and making things easier, raise crucial points to ponder upon.

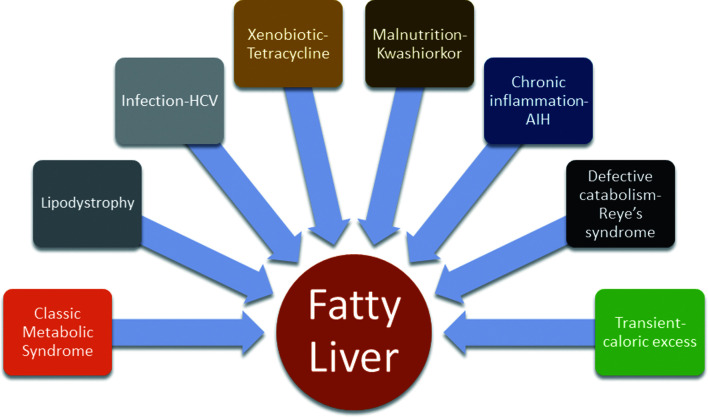

Fatty liver disease - different avatars

It is well known that lipid deposition in the liver is not exclusively hyperinsulinemia-mediated and can be caused by a range of conditions, like lipodystrophies, hepatitis C virus infection, adverse effects of drugs like tetracyclines, defects in metabolism like Reye’s syndrome, chronic inflammation, and in states of malnutrition.18–23 This lends credence to the hypothesis that NAFLD can exist in the absence of MS and IR and involve hitherto unexplored pathophysiological mechanisms. The different conditions that can cause fatty liver are illustrated in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Different conditions that can cause hepatic steatosis.

AIH, Autoimmune Hepatitis; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus.

NAFLD without metabolic syndrome – peculiarities

Studies have revealed that underweight subjects and those with normal BMI also develop NAFLD.24 In a study by Singh et al.,25 nearly half of the NAFLD subjects did not have IR and a significantly higher proportion of patients in non-IR group were non-obese. Similar findings were also observed in a study on NAFLD subjects in Bangladesh.26 Thus, the universality of association of MS with NAFLD is being increasingly disputed. Furthermore, although NAFLD with MS has been shown to have considerable risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and increase of left ventricular mass index in comparison to NAFLD without MS,27 other studies have also shown that NAFLD patients without MS displayed preclinical cardiologic abnormalities which were independent of diabetes mellitus and hypertension.28 Classical features of MS-IR, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia have not been observed in NAFLD associated with the patatin like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) Ile148Met variant, in which fatty liver occurs independent of presence of MS.29 Thus, two things are clear: neither is MS ubiquitous in NAFLD, nor does the association of MS and NAFLD follow the cause-effect equation, clearly indicating that there is much more to NAFLD pathogenesis than IR and MS.

Can hepatic steatosis give rise to IR?

The chicken-egg conundrum concerning the primacy of MS over NAFLD has persisted for a long time. While IR leading to hepatic steatosis has always held center stage, there is increasing evidence to indicate that hepatic triglyceride accumulation is also responsible for causing IR in the liver.30 This implies that the suppressive effects of insulin on hepatic glucose and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and triglyceride production are hampered.31 This contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, major components of the MS. From an evolutionary viewpoint, IR is an adaptive mechanism of the body to preserve glucose for various cellular processes, especially in states of starvation and immune activation.32 However, multiple factors can lead to this process of adaption to go awry with deleterious consequences.33 IR is associated with release of inflammatory mediators at the cellular level.34 Production of adipokines, IL-1, IL-6, resistin, leptin and free fatty acids mediate the release of kinases, like JNK, IKK-β and protein kinase C (PKC), which further impair insulin signalling.34 IR acts at two levels: hepatic and peripheral sites. However, hepatic IR can occur independent of changes in circulating adipokines.35 Hepatic steatosis and hepatic IR have also been found to occur in experimental models prior to the development of obesity, and increases in adipokine levels imply that hepatic steatosis may have an independent genesis.36

The diacylglycerol (DAG)-PKC hypothesis and the associated controversies might possibly partly explain this conundrum. Increased hepatic DAG activates the PKC-ϵ isoform, which causes phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and drives hepatic IR.36 Knockdown of PKC-ϵ has been shown to protect rats from high-fat diet-induced hepatic IR.37 Intrahepatic DAG accumulation can be from free fatty acid-derived lipolysis, chylomicron-mediated uptake, or hepatic de novo lipogenesis.38 The DAG-PKC-ϵ pathway successfully explains that NAFLD can definitely act as a precursor to MS.

Do all patients with hepatic steatosis develop MS?

This hypothesis, however, contradicts the findings of Monetti et al.,39 who have reported that mice overexpressing acylCoA:DAG acyltransferase 2, which converts DAG to triacylglycerol (TAG) in the liver, do not demonstrate hepatic IR, even with elevated hepatic TAG and DAG content. This has brought to the fore the idea of compartmentalization of DAG in the hepatocyte.40 Cytoplasmic compartmentalization of DAG in the hepatocyte, in the form of lipid droplet, strongly correlated with PKC-ϵ activation and IR, whereas other lipid metabolites had no correlation with IR.41 The dissociation of hepatic steatosis from IR has also been seen in murine models.40 The sequestration of DAGs in specific compartments, which might include membrane-bound cellular vesicles that do not lead to PKC-ϵ activation and consequent IR, is an idea upon which much work is being focused.42 The idea that PKCs might have different affinities for different species of DAGs has also gained prominence.43 This might partly explain why in a proportion of subjects, the relationship between hepatic steatosis and IR seems dichotomous.44 However, despite advances in lipidomics and molecular biology, these are grey zones and much remains to be done to understand the exact mechanisms better.

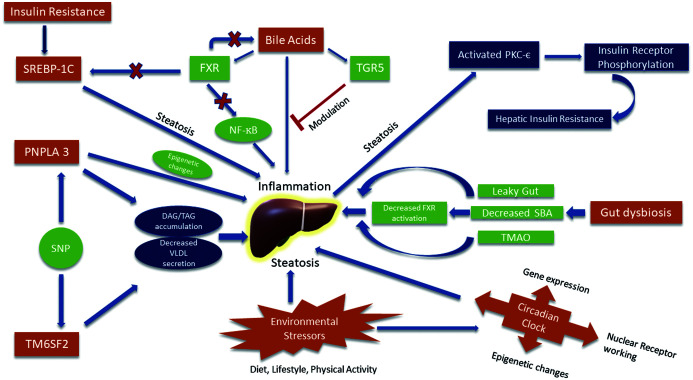

NAFLD multifactorial pathogenesis

In addition to genetic and environmental factors as well as bile acid metabolism, gut microbiota and a host of other players work in tandem and play important roles in the pathophysiological processes. The various mediators of hepatocyte injury and the pathophysiological processes involved in the development of NAFLD/NASH are discussed below.

Genetic factors

Epidemiological, familial and twin studies have provided ample evidence in favor of heritability of NAFLD.45,46 Genetic modifications occur at multiple steps of NAFLD pathogenesis, including insulin sensitivity, fatty acid influx, oxidative stress, cytokine activity and fibrogenesis.47 Genome-wide association studies have identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the PNPLA3 gene, rs738409 C>G SNP, which conferred a more than 2-fold risk for higher hepatic fat content.48 PNPLA3 is induced in the liver after feeding and during IR by fatty acids and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), the master regulator of lipogenesis.49 The function of PNPLA3 is to catalyze DAG and TAG hydrolysis.50 Quite interestingly, steatosis was found to be independent of IR and serum lipid levels in individuals with PNPLA3 polymorphism.48 The presence of this SNP prevents ubiquitination of PNPLA3 and its proteasomal degradation, resulting in decreased TAG mobilization from lipid droplets in the liver.51 In addition, several other SNPs have been identified in other genes. These include neurocan (SNP rs2228603), protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 3B (SNP rs4240624), glucokinase regulator (SNP rs780094), lysophospholipase-like 1 (SNP rs12137855), peroxisome proliferator activator-alpha (PPAR-α SNP Val227Ala), lipin1 (SNP rs13412852 T) and transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2, SNP rs58542926 c.449 C>T).52–55

Bile acid metabolism

Elevation in total bile acids has been observed in NAFLD patients.56 Increased serum levels of glychochendeoxycholate, glycholate, and taurocholate have been observed in patients with NASH compared to healthy controls.57 Bile acids regulate multiple pathways through activation of nuclear receptors, like farnesoid X receptor (FXR), pregnane X receptor, and vitamin D receptor.58,59 FXR functions to protect hepatocytes from the harmful effects of increased bile acid levels by FGF-19-mediated inhibition of endogenous bile acid synthesis and upregulation of bile acid biotransformation.60,61 The role of FXR in ameliorating hepatic inflammation through the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway has also been established.62 Recent studies seem to suggest that elevated serum bile acid levels have an independent association with NASH in individuals who are non-diabetic.63

Gut microbiota

The involvement of gut microbiota in NAFLD pathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Increased intestinal permeability subsequent to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth has been observed in NASH patients.64 Inflammation ensues with hepatic expression of toll like receptor 4 and release of interleukin-8.64 Conversion of choline to trimethylamine and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) by gut microflora has also been linked to hepatic inflammation and damage.65 Gut dysbiosis leads to decreased synthesis of secondary bile acids, which in turn decreases activation of nuclear receptors.66 FXR and TGR5 downregulation affect bile acid metabolism and promote hepatocyte injury.67,68 Ethanol production by gut microbiota leading to NAFLD is another example of the role of gut dysbiosis in the complex pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying NAFLD.69 Further, NAFLD patients have been found to have lower abundance of Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Coprococcus independent of body mass index and IR, implying that NAFLD is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and IR.70

Epigenetic modifications

The rapidly growing field of epigenetics has shed new light on NAFLD pathogenesis by explaining the effect of several environmental factors, like over nutrition and physical inactivity, upon gene expression.71 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, an epigenetic modification, is likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD by regulating liver mitochondrial biogenesis and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α expression.72 DNA methylation at certain CpG islands in genes mediating fibrogenesis has been found to differentiate between patients with mild and severe fibrosis in NAFLD.73 However, these studies are in their infancy, and before attributing disease processes in NAFLD to epigenetic modifications, meticulous follow-up studies are required to understand the effects of DNA methylation on fibrosis progression.74 An emerging concept is the interplay between genetic and epigenetic variants in determining gene expression and NAFLD disease progression. Methylation in the PNPLA3 promoter region has been studied and it has been seen that it was significantly hypermethylated in patients with severe (F3–4) fibrosis.75 The role of histone deacetylation has also gained importance in view of the observation that histone deacetylase 3 has been implicated in the diversion of metabolites from hepatic gluconeogenesis to lipogenesis and storage.76 Thus, a growing body of evidence is accumulating in favor of the role of epigenetics in NAFLD pathogenesis.

Role of circadian rhythm

The workings of the circadian clock have been greatly explored in the pathogenesis of multiple disorders and the close interactions of circadian rhythm with endocrine functions and energy homoeostasis have been discovered.77–80 Circadian clock is modulated by a core oscillator in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus in conjunction with multiple peripheral clocks in other organs, including the liver.81 There is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that the pathways of energy homeostasis in the liver involves complex mechanisms of transcriptional and post-translational regulation of circadian clock gene expression.81 Evidence suggests that transcription factors, such as PARbZIP and Nfil3, which regulate the process of hepatic xenobiotic transformation are under the control of circadian clock proteins, such as Per1, Per2, Rev-erbα, Rev-erbβ, Rorα, Rorβ, and Rorγ.82 One particular SNP, 3111T>C in Clock (rs1801260), has been found to be associated with overweight status and an increased risk of hepatic steatosis in women.83 This is compatible with experiments in murine models where mutations in clock genes produce more severe hepatic steatosis under both regular and high-fat chow feeding conditions compared to wild-type mice.84 An intricate network operates between circadian rhythm, epigenetic changes, gene expression and nuclear receptor working.84 Nuclear receptors sense nutrient levels and control cellular metabolism.85 Recruitment of nuclear receptor co-repressors induce histone deacetylase activity.86 This, in turn, influences chromatin conformation and modelling.87 Normal hepatic lipid homoeostasis requires recruitment of HDAC3 by Rev-erbα, a circadian nuclear receptor.88 Bile acid homoeostasis works under circadian control, evidenced by disturbed bile acid metabolism in mice with Per1 and Per 2 knockouts.89 Therefore, it is amply clear that circadian misalignment can cause dysregulation of cellular metabolism leading to hepatic steatosis.84

Dietary and environmental factors

Dietary habits and intake of certain food products have been implicated in the pathogenesis of NAFLD.90,91 Foods rich in animal protein and less in fiber, soft drinks and snacks have been associated with presence of fatty liver.90 Consumption of soft drinks has been associated with NAFLD independent of the traditional risk factors like obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.92,93 Cigarette smoking has been linked to exacerbation of liver injury in a rat model of obese-NAFLD through oxidative stress and hepatocellular apoptosis.94 In a large cohort study of 199,468 young and middle aged persons who did not have NAFLD at baseline and were followed up for 1,070,991 person-years, 45,409 persons developed NAFLD.95 Cigarette smoking, pack-years of cigarettes smoked, and urinary cotinine levels were found to be positively associated with NAFLD incidence, and smoking was observed be an independent risk factor for NAFLD progression.95 Therefore, the prevalent view that dietary factors lead to obesity, diabetes, MS and thereby impact NAFLD pathogenesis96 has been increasingly questioned, and emerging evidence suggests that environmental stressors can cause liver injury independent of traditional risk factors.

The spectrum of the pathophysiological pathways in NAFLD, a maze in itself, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. The maze of NAFLD-interactions and cross-talk among multiple factors leading to hepatic steatosis. Hepatic steatosis itself can give rise to IR.

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; SREBP 1C, Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 1C; PNPLA 3, Patatin Like Phospholipase Domain Containing Protein-3; TM6SF2, Transmembrane 6 Superfamily Member 2; SNP, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism; DAG, Diacyl Glycerol; TAG, Triacyl Glycerol; VLDL, Very Low-Density Lipoprotein; FXR, Farnesoid X Receptor; TGR5, Takeda G-Protein Receptor 5; NF-ĸB, Nuclear Factor Kappa B; SBA, Secondary Bile Acids; TMAO, Trimethylamine Oxide; PKCє, Protein Kinase C-epsilon isoform.

Philosophy behind medical nomenclature

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other name would smell as sweet.

Romeo and Juliet —William Shakespeare

Naming of a disease or an entity, although seemingly simple, has far-reaching consequences. There have been several attempts to systematize the nomenclature of diseases.97 Best practice recommendations have also been issued by the World Health Organization in this regard for infectious diseases.6 The idea behind these is to impress upon members of the medical fraternity as well as the general populace about the significance of the disease entity. The term ‘non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (acronym-NAFLD)’ encompasses those individuals who have fatty liver without history of significant alcohol intake and other conditions that could cause fatty liver. Importantly, not all patients in Ludwig’s study were overweight/obese. Further research has only consolidated the point that NAFLD is a disease of multifactorial and competing etiologies and can not be ascribed to any single factor.

It has not been possible as of yet to ascribe hepatic steatosis to any single cause and the unitary treatment targeting has not yielded successful treatment options. The general idea is that NAFLD is a spectrum of disorders, with MS occupying a predominant part of that spectrum. Despite years of research, we have not been able to add much to the treatment arsenal of NAFLD. Changing the nomenclature could put an exaggerated emphasis on MS, which ultimately may not turn out to be the only target. While the pathophysiology is still a puzzle, how would a mere change in name help?

MAFLD: Is the new terminology justified?

There have been several arguments put forward by the proponents of MAFLD in favor of a name change. The objections to NAFLD are that NAFLD should be defined by inclusion rather than by exclusion, the heterogeneity of NAFLD implies that it is difficult to manage it as a single entity, and the effects of non-significant amounts of alcohol consumed by NAFLD patients on hepatic steatosis have not yet been clearly defined.2 The diagnosis of MAFLD requires radiological evidence of hepatic steatosis and the presence of any one of the following three conditions: overweight/obesity, presence of diabetes mellitus, or evidence of metabolic dysregulation.2 In fact, in their algorithm, the diagnosis of MAFLD is essentially identical to the diagnosis of NAFLD.

There are several problems with this approach. First, putting ‘non’ in the nomenclature of a disease and approaching it through exclusion has been a time-tested, simple and very effective approach in medical science. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-small cell carcinoma are prime examples of this approach.98–100 It is indeed peculiar the way the change in name is sought to be justified. The proponents of MAFLD have surprisingly split “nonalcoholic” into two words: ‘non’ and ‘alcoholic’, followed by the assertion that the word “non” trivializes their problem, while the word alcoholic demeans the patient and blames the patient for the disease. This rationale for change in terminology, however, trivializes the seriousness of changing a term which has stood the test of time for almost half a century. Quite to the contrary, the term ‘nonalcoholic’ destigmatizes the patient. The term “metabolic” in MAFLD as a reference to MS itself trivializes the gamut of evidence garnered in NAFLD research to date.

To put things in perspective, the Rome Foundation has been frequently changing the names of functional bowel disorders, many of which are not so functional after all. For example, in a validation study of 1,452 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, the Rome III criteria performed only modestly in identifying those with functional dyspepsia and were not significantly superior to previous definitions.101 Despite one of the rationales for the revision being to allow separation of functional dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease more clearly, almost identical proportions of patients meeting criteria for each of the different definitions of FD were found to have erosive esophagitis.101

Second, merely replacing the term NAFLD with MAFLD would not make the entity any less heterogeneous. At the moment, their exists considerable uncertainty regarding the pathogenesis of NAFLD, and a change in name cannot be justified.

Third, the impact of nonsignificant intake of alcohol on hepatic metabolism is itself very unclear; some studies have shown a decreased progression to NASH with moderate alcohol consumption, as acknowledged in the consensus paper. Moreover, metabolic complications in alcoholic fatty liver disease have been demonstrated too.102 Besides, lipid metabolism abnormalities,103 disturbances in sirtuin104 and PPAR-γ105 pathways have also been shown to occur in alcoholic liver disease. Can the change in terminology to MAFLD provide adequate answers to these perplexing questions? Thus, it is clear that the reasons stated for such a sudden change are very flimsy and have no rational basis.

Interestingly, in a review concerning the challenges of the diagnosis and classification of NAFLD by Hashimoto, Tokushige and Ludwig in 2015, it was argued that recommendations to change the nomenclature of NAFLD to metabolic fatty liver or metabolic steatohepatitis would be of little help, and since patients with NAFLD/NASH were also being treated by cardiologists and diabetologists in addition to hepatologists, such changes in nomenclature would create confusion and should be avoided.106

It will be worthwhile to mention here that as regards the change in nomenclature, European Liver Patients Association (ELPA) had expressed its concerns to the European Commission in 2018, arguing for a change in nomenclature.1 We tried to elicit an answer from ELPA in this regard - if this was true and if so, the reasons for such a suggestion. We also sought to know how this was decided, the percentage of patients who feel uncomfortable with such terminology and importantly, if the heterogeneity in NAFLD pathogenesis—especially in non-Caucasians—was taken into account. However, despite repeated queries, unfortunately, we did not receive any reply from ELPA.

Most of the emerging literature on the NAFLD versus MAFLD debate have pooled patients of NAFLD with other patients of fatty liver due to dual etiology and then compared these patients with NAFLD patients.107 This has obviously resulted in increased prevalence of hepatic fibrosis in this cohort108 and it needs no rocket science to understand this, since fatty liver patients with dual etiology including alcohol (up to 60 gram/day) have been compared to patients with NAFLD! Instead of achieving ‘homogeneity’ which the proponents of MAFLD harp on, this has paradoxically made the entity more heterogenous. Besides, another offshoot of this change would be that this will push the field back, since all study protocols to date have been based on NAFLD. It would not be possible to reconcile previous data on NAFLD with new data on MAFLD.

Conclusion

NAFLD cannot be kept confined to the precincts of MS, nor is NAFLD just another ‘manifestation’ of MS. It is clear that rather than changing the nomenclature without a strong scientific backing to support such a change, there should be more efforts directed at understanding NAFLD pathogenesis across diverse populations and ethnicities. This would definitely lead to newer therapeutic approaches. We hope in the near future, there will be sufficient advances in our understanding of NAFLD pathogenesis to enable translation into clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ELPA

European Liver Patients Association

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- IR

insulin resistance

- MAFLD

metabolic-associated fatty liver disease

- MS

metabolic syndrome

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NF-ĸB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PNPLA3

patatin like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3

- SBA

secondary bile acid

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SREBP 1C

sterol regulatory element binding protein 1C

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TGR5

Takeda G-protein receptor 5

- TM6SF2

transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2

- TMAO

trimethylamine oxide

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

References

- 1.Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J, International Consensus Panel MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1999–2014.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eslam M, Ratziu V, George J. Yet more evidence that MAFLD is more than name change. J Hepatol. 2021;74(4):977–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young ME, Norman GR, Humphreys KR. The role of medical language in changing public perceptions of illness. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janda JM. Proposed nomenclature or classification changes for bacteria of medical importance: taxonomic update 5. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;97(3):115047. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO | WHO issues best practices for naming new human infectious diseases. WHO. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2015/naming-new-diseases/en/

- 7.Reuben A. Leave gourmandising. Hepatology. 2002;36(5):1303–1306. doi: 10.1002/hep.510360543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor CL. Fatty infiltration of the liver and the development of cirrhosis in diabetes and chronic alcoholism. Am J Pathol. 1938;14(3):347–364.9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westwater JO, Fainer D. Liver impairment in the obese. Gastroenterology. 1958;34(4):686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler M, Schaffner F. Fatty liver hepatitis and cirrhosis in obese patients. Am J Med. 1979;67(5):811–816. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopec KL, Burns D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of the spectrum of disease, diagnosis, and therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011;26(5):565–576. doi: 10.1177/0884533611419668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity: an autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatol Baltim Md. 1990;12(5):1106–1110. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson S, Eriksson KF, Bondesson L. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obesity: a reversible condition. Acta Med Scand. 1986;220(1):83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb02733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina J, Fernández-Salazar LI, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R. Approach to the pathogenesis and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(8):2057–2066. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2018;67(1):328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polyzos SA, Perakakis N, Mantzoros CS. Fatty liver in lipodystrophy: a review with a focus on therapeutic perspectives of adiponectin and/or leptin replacement. Metabolism. 2019;96:66–82. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noureddin M, Wong MM, Todo T, Lu SC, Sanyal AJ, Mena EA. Fatty liver in hepatitis C patients post-sustained virological response with direct-acting antivirals. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(11):1269–1277. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i11.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tetracycline. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547920/ [PubMed]

- 21.Partin JC. Reye’s syndrome (encephalopathy and fatty liver). Diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 1975;69(2):511–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, Zhong S, Qu H, Xie Y, Cao Z, Li Q, et al. Chronic inflammation aggravates metabolic disorders of hepatic fatty acids in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):10222. doi: 10.1038/srep10222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Zutphen T, Ciapaite J, Bloks VW, Ackereley C, Gerding A, Jurdzinski A, et al. Malnutrition-associated liver steatosis and ATP depletion is caused by peroxisomal and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Hepatol. 2016;65(6):1198–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam S, Fahim SM, Chowdhury MAB, Hassan MZ, Azam G, Mustafa G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bangladesh. JGH Open. 2018;2(2):39–46. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh SP, Misra B, Kar SK, Panigrahi MK, Misra D, Bhuyan P, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) without insulin resistance: is it different? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39(4):482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azam G, Alam S, Hasan SN, Alam SMNE, Kabir J, Alam AK. Insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: experience from Bangladesh. Bangladesh Crit Care J. 2016;4(2):86–91. doi: 10.3329/bccj.v4i2.30022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Käräjämäki AJ, Bloigu R, Kauma H, Kesäniemi YA, Koivurova OP, Perkiömäki J, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without metabolic syndrome: different long-term outcomes. Metabolism. 2017;66:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makker J, Tariq H, Bella JN, Kumar K, Chime C, Patel H, et al. Preclinical cardiac disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with and without metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;9(5):65–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lallukka S, Sevastianova K, Perttilä J, Hakkarainen A, Orho-Melander M, Lundbom N, et al. Adipose tissue is inflamed in NAFLD due to obesity but not in NAFLD due to genetic variation in PNPLA3. Diabetologia. 2013;56(4):886–892. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2829-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.den Boer M, Voshol PJ, Kuipers F, Havekes LM, Romijn JA. Hepatic steatosis: a mediator of the metabolic syndrome. lessons from animal models. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(4):644–649. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000116217.57583.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee RG. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a study of 49 patients. Hum Pathol. 1989;20(6):594–598. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soeters MR, Soeters PB. The evolutionary benefit of insulin resistance. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2012;31(6):1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsatsoulis A, Mantzaris MD, Bellou S, Andrikoula M. Insulin resistance: an adaptive mechanism becomes maladaptive in the current environment—an evolutionary perspective. Metab - Clin Exp. 2013;62(5):622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meshkani R, Adeli K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(13):1331–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Yu C, Moore IK, Pypaert M, et al. Tissue-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes tissue-specific insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(13):7522–7527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121164498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samuel VT, Liu Z-X, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(31):32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gassaway BM, Petersen MC, Surovtseva YV, Barber KW, Sheetz JB, Aerni HR, et al. PKCε contributes to lipid-induced insulin resistance through cross talk with p70S6K and through previously unknown regulators of insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(38):E8996–E9005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804379115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Diacylglycerol activation of protein kinase Cε and hepatic insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):574–584. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monetti M, Levin MC, Watt MJ, Sajan MP, Marmor S, Hubbard BK, et al. Dissociation of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice overexpressing DGAT in the liver. Cell Metab. 2007;6(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cantley JL, Yoshimura T, Camporez JPG, Zhang D, Jornayvaz FR, Kumashiro N, et al. CGI-58 knockdown sequesters diacylglycerols in lipid droplets/ER-preventing diacylglycerol-mediated hepatic insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(5):1869–1874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219456110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumashiro N, Erion DM, Zhang D, Kahn M, Beddow SA, Chu X, et al. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(39):16381–16385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113359108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petersen MC, Shulman GI. Roles of diacylglycerols and ceramides in hepatic insulin resistance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38(7):649–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamiya Y, Mizuno S, Komenoi S, Sakai H, Sakane F. Activation of conventional and novel protein kinase C isozymes by different diacylglycerol molecular species. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2016;7:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantartzis K, Peter A, Machicao F, Machann J, Wagner S, Königsrainer I, et al. Dissociation between fatty liver and insulin resistance in humans carrying a variant of the patatin-like phospholipase 3 gene. Diabetes. 2009;58(11):2616–2623. doi: 10.2337/db09-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makkonen J, Pietiläinen KH, Rissanen A, Kaprio J, Yki-Järvinen H. Genetic factors contribute to variation in serum alanine aminotransferase activity independent of obesity and alcohol: a study in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. J Hepatol. 2009;50(5):1035–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Struben VM, Hespenheide EE, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis within kindreds. Am J Med. 2000;108(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rowell RJ, Anstee QM. An overview of the genetics, mechanisms and management of NAFLD and ALD. Clin Med Lond Engl. 2015;15(Suppl 6):s77–82. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-6-s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Y, He S, Li JZ, Seo YK, Osborne TF, Cohen JC, et al. A feed-forward loop amplifies nutritional regulation of PNPLA3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):7892–7897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003585107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, Garuti R, Kinch L, Grishin NV, et al. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPLA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6706–6715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bruschi FV, Tardelli M, Claudel T, Trauner M. PNPLA3 expression and its impact on the liver: current perspectives. Hepatic Med Evid Res. 2017;9:55–66. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S125718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dongiovanni P, Anstee QM, Valenti L. Genetic predisposition in NAFLD and NASH: impact on severity of liver disease and response to treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(29):5219. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fawcett KA, Grimsey N, Loos RJF, Wheeler E, Daly A, Soos M, et al. Evaluating the role of LPIN1 variation in insulin resistance, body weight, and human lipodystrophy in U.K. Populations. Diabetes. 2008;57(9):2527–2533. doi: 10.2337/db08-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen S, Li Y, Li S, Yu C. A Val227Ala substitution in the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) gene associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and decreased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(9):1415–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y-L, Reeves HL, Burt AD, Tiniakos D, McPherson S, Leathart JB, et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):4309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bechmann LP, Kocabayoglu P, Sowa JP, Sydor S, Best J, Schlattjan M, Beilfuss A, et al. Free fatty acids repress small heterodimer partner (SHP) activation and adiponectin counteracts bile acid-induced liver injury in superobese patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2013;57(4):1394–1406. doi: 10.1002/hep.26225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalhan SC, Guo L, Edmison J, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Hanson RW, et al. Plasma metabolomic profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2011;60(3):404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makishima M, Okamoto AY, Repa JJ, Tu H, Learned RM, Luk A, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284(5418):1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guo GL, Lambert G, Negishi M, Ward JM, Brewer HB, Jr, Kliewer SA, et al. Complementary roles of farnesoid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor in protection against bile acid toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(46):45062–45071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fuchs M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the bile acid-activated farnesoid X receptor as an emerging treatment target. J Lipids. 2012;2012:934396. doi: 10.1155/2012/934396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kir S, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Roles of FGF19 in liver metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:139–144. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang YD, Chen WD, Wang M, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor κB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology. 2008;48(5):1632–1643. doi: 10.1002/hep.22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Ma J, Gu L, Jin L, Chen P, Zhang X, et al. Increased serum total bile acid is independently associated with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in non-diabetes population. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-27123/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferolla SM, Armiliato GNA, Couto CA, Ferrari TCA. The role of intestinal bacteria overgrowth in obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. 2014;6(12):5583–5599. doi: 10.3390/nu6125583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen J, Thomsen M, Vitetta L. Interaction of gut microbiota with dysregulation of bile acids in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and potential therapeutic implications of probiotics. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(3):2713–2720. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Armstrong LE, Guo GL. Role of FXR in liver inflammation during nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2017;3(2):92–100. doi: 10.1007/s40495-017-0085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arab JP, Karpen SJ, Dawson PA, Arrese M, Trauner M. Bile acids and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2017;65(1):350–362. doi: 10.1002/hep.28709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu L, Baker RD, Zhu R, Baker SS. Gut microbiota produce alcohol and contribute to NAFLD. Gut. 2016;65(7):1232. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Da Silva HE, Teterina A, Comelli EM, Taibi A, Arendt BM, Fischer SE, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and insulin resistance. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1466. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19753-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao F. Dysregulated epigenetic modifications in the pathogenesis of NAFLD-HCC. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1061:79–93. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8684-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pirola CJ, Scian R, Gianotti TF, Dopazo H, Rohr C, Martino JS, et al. Epigenetic modifications in the biology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of DNA hydroxymethylation and TET proteins. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(36):e1480. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeybel M, Hardy T, Robinson SM, Fox C, Anstee QM, Ness T, et al. Differential DNA methylation of genes involved in fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:25. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hardy T, Mann DA. Epigenetics in liver disease: from biology to therapeutics. Gut. 2016;65(11):1895–1905. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kitamoto T, Kitamoto A, Ogawa Y, Honda Y, Imajo K, Saito S, et al. Targeted-bisulfite sequence analysis of the methylation of CpG islands in genes encoding PNPLA3, SAMM50, and PARVB of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;63(2):494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun Z, Miller RA, Patel RT, Chen J, Dhir R, Wang H, Zhang D, et al. Hepatic Hdac3 promotes gluconeogenesis by repressing lipid synthesis and sequestration. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):934–942. doi: 10.1038/nm.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xie Y, Tang Q, Chen G, Xie M, Yu S, Zhao J, et al. New insights into the circadian rhythm and its related diseases. Front Physiol. 2019;10:682. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li X, Shaffer ML, Rodríguez-Colón SM, He F, Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, et al. Systemic inflammation and circadian rhythm of cardiac autonomic modulation. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2011;162(1-2):72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inokawa H, Umemura Y, Shimba A, Kawakami E, Koike N, Tsuchiya Y, et al. Chronic circadian misalignment accelerates immune senescence and abbreviates lifespan in mice. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2569. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59541-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gnocchi D, Custodero C, Sabbà C, Mazzocca A. Circadian rhythms: a possible new player in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathophysiology. J Mol Med. 2019;97(6):741–759. doi: 10.1007/s00109-019-01780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou D, Wang Y, Chen L, Jia L, Yuan J, Sun M, et al. Evolving roles of circadian rhythms in liver homeostasis and pathology. Oncotarget. 2016;7(8):8625–8639. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tahara Y, Shibata S. Circadian rhythms of liver physiology and disease: experimental and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(4):217–226. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bandín C, Martinez-Nicolas A, Ordovás JM, Ros Lucas JA, Castell P, Silvente T, et al. Differences in circadian rhythmicity in CLOCK 3111T/C genetic variants in moderate obese women as assessed by thermometry, actimetry and body position. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(8):1044–1050. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mazzoccoli G, Vinciguerra M, Oben J, Tarquini R, De Cosmo S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of nuclear receptors and circadian rhythmicity. Liver Int. 2014;34(8):1133–1152. doi: 10.1111/liv.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu S, Downes M, Evans RM. Metabolic regulation by nuclear receptors. In: Nakao K, Minato N, Uemoto S, editors. Innovative Medicine. 2015. pp. 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.You SH, Lim HW, Sun Z, Broache M, Won KJ, Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor corepressors are required for the histone deacetylase activity of HDAC3 in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):182–187. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gallinari P, Marco SD, Jones P, Pallaoro M, Steinkühler C. HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: from molecular biology to cancer therapeutics. Cell Res. 2007;17(3):195–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, Bugge A, Mullican SE, Alenghat T, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331(6022):1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ma K, Xiao R, Tseng HT, Shan L, Fu L, Moore DD. Circadian dysregulation disrupts bile acid homeostasis. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rietman A, Sluik D, Feskens EJM, Kok FJ, Mensink M. Associations between dietary factors and markers of NAFLD in a general Dutch adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(1):117–123. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tajima R, Kimura T, Enomoto A, Yanoshita K, Saito A, Kobayashi S, et al. Association between rice, bread, and noodle intake and the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Japanese middle-aged men and women. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2017;36(6):1601–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Assy N, Nasser G, Kamayse I, Nseir W, Beniashvili Z, Djibre A, et al. Soft drink consumption linked with fatty liver in the absence of traditional risk factors. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(10):811. doi: 10.1155/2008/810961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abid A, Taha O, Nseir W, Farah R, Grosovski M, Assy N. Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver disease independent of metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol. 2009;51(5):918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Azzalini L, Ferrer E, Ramalho LN, Moreno M, Domínguez M, Colmenero J, et al. Cigarette smoking exacerbates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1567–1576. doi: 10.1002/hep.23516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jung HS, Chang Y, Kwon MJ, Sung E, Yun KE, Cho YK, et al. Smoking and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):453–463. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mirmiran P, Amirhamidi Z, Ejtahed H-S, Bahadoran Z, Azizi F. Relationship between diet and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review article. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(8):1007–1017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chute CG. Clinical classification and terminology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):298–303. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Armitage JO, Gascoyne RD, Lunning MA, Cavalli F. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):298–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Singh SP, Anirvan P, Reddy KR, Conjeevaram HS, Marchesini G, Rinella ME, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: not time for an obituary just yet! 2021;74(4):972–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zappa C, Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(3):288–300. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.06.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, Bolino C, Pintos-Sanchez MI, Moayyedi P. The Rome III criteria for the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia in secondary care are not superior to previous definitions. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(4):932–940. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.014. quiz e14-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hamaguchi M, Obora A, Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Kojima T, Fukui M. Changes in metabolic complications in patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease monitored over two decades: NAGALA study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7(1):e000359. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Louvet A, Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(4):231–242. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yin H, Hu M, Liang X, Ajmo JM, Li X, Bataller R, et al. Deletion of SIRT1 from hepatocytes in mice disrupts Lipin-1 signaling and aggravates alcoholic fatty liver. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):801–811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tomita K, Azuma T, Kitamura N, Nishida J, Tamiya G, Oka A, et al. Pioglitazone prevents alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats through upregulation of c-Met. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(3):873–885. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hashimoto E, Tokushige K, Ludwig J. Diagnosis and classification of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: current concepts and remaining challenges. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(1):20–28. doi: 10.1111/hepr.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fouad Y, Elwakil R, Elsahhar M, Said E, Bazeed S, Ali Gomaa A, et al. The NAFLD-MAFLD debate: eminence vs evidence. Liver Int. 2021;41(2):255–260. doi: 10.1111/liv.14739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yamamura S, Eslam M, Kawaguchi T, Tsutsumi T, Nakano D, Yoshinaga S, et al. MAFLD identifies patients with significant hepatic fibrosis better than NAFLD. Liver Int. 2020;40(12):3018–3030. doi: 10.1111/liv.14675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]