Abstract

Interaction of the T cell receptor (TCR) with an MHC-antigenic peptide complex results in changes at the molecular and cellular levels in T cells. The outside environmental cues are translated into various signal transduction pathways within the cell, which mediate the activation of various genes with the help of specific transcription factors. These signaling networks propagate with the help of various effector enzymes, such as kinases, phosphatases, and phospholipases. Integration of these disparate signal transduction pathways is done with the help of adaptor proteins that are non-enzymatic in function and that serve as a scaffold for various protein–protein interactions. This process aids in connecting the proximal to distal signaling pathways, thereby contributing to the full activation of T cells. This review provides a comprehensive snapshot of the various molecules involved in regulating T cell receptor signaling, covering both enzymes and adaptors, and will discuss their role in human disease.

Subject terms: Haematological cancer, Lymphocytes

Introduction

T cells are key mediators in mounting an effective adaptive cell-mediated immune response.1,2 T cells continuously screen lymphoid and peripheral tissues for antigens such as peptides or lipids displayed by major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) molecules of other cells. Normal T cell development in the thymus undergoes a major developmental checkpoint in which T cell receptor (TCR) signaling is involved. Thymocytes bearing TCR with a high affinity for self-peptide MHC complexes undergo apoptosis (negative selection), whereas those bearing low-affinity TCR survive and differentiate into mature T cells (positive selection).3 This ensures that only those T cells that are self-tolerant survive while eliminating the self-reactive T cells.4 These naïve single positive mature T cells then leave the thymus and enter the peripheral lymphoid organs, such as the spleen and lymph nodes, where they get exposed to foreign peptides presented by the MHC molecules of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as the macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells, during pathogenic infection.5 Upon engagement of TCR with the antigenic peptide, T cells get activated, undergoing clonal expansion and differentiation to perform their effector functions, due to a complex series of molecular changes at the plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus.6,7 T cell signaling is thus important for efficient T cell development, activation, and immune tolerance. TCR signaling dysregulation can thus lead to anergy or autoimmunity.8

In general, the transmission of external cues to the interior of the cell occurs through binding of a ligand to the extracellular domain of the receptor, leading to receptor aggregation or conformational changes. Once this is accomplished, protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) phosphorylate various tyrosine residues present in the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor, which serve as a docking site for various signaling molecules containing specific phosphotyrosine recognition domains such as the SRC homology 2 (SH2) and phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains.6 This initiates proximal biochemical signals mediated by the key effector enzymes, such as kinases, phosphatases, and phospholipases, that culminate in distal signaling by activating numerous transcription factors required for translating these events into gene activation.9 However, both the proximal and distal signaling need to be integrated, and this is done by various adaptor proteins whose main function is to form multiprotein complexes.10

Adaptors are proteins that usually lack intrinsic enzymatic activity and instead possess multiple binding domains for phosphotyrosine, proline-rich region and lipid interactions, and sequence motifs that in turn are involved in binding to such domains.11,12 The phosphorylated tyrosine residues on various adaptor proteins serve as binding sites for many critical effector enzymes and other adaptor proteins.6 Thus, they behave as scaffolds, facilitating protein–protein interactions that aid in forming multiprotein complexes, thereby integrating signaling cascades necessary for efficient T cell biology. Apart from this, adaptors also interact with other adaptors present at the plasma membrane microdomains and even play important roles in the regulation of the cytoskeleton.6,10,13 Hematopoietic-specific adaptor proteins have led to a better understanding of T cell signaling.13 Those adaptor proteins can regulate signal transduction both positively and negatively.10,13 In this review, we discuss the role of TCR signaling in human health and disease.

Components and structure of TCR complex

The core TCR complex consists of two TCR chains and six cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3) chains. Several other components include coreceptors, kinases, and ligands.14,15

TCR-CD3 chains

The human genome expresses four TCR genes known as TCRα, TCRβ, TCRγ, and TCRδ, which forms two distinct heterodimers: TCRα/TCRβ or TCRγ/TCRδ.16–18 The majority of mature T cells expresses TCRα and TCRβ isoforms, generally referred to as T cells (or αβ T cells), while a small portion (0.5–5%) of T lymphocytes (γδ T cells) expresses TCRγ and TCRδ isoforms.19 In this review, we will focus on αβ T cells, and henceforth the nomenclature T cells will refer to αβ T cells.

Both heterodimers form multiprotein complexes with CD3 δ, γ, ε, and ζ chains. TCR chains consist of an extracellular region, transmembrane region, and a shorter cytoplasmic tail. The extracellular region contains a variable immunoglobulin-like (V) domain, a constant immunoglobulin-like (C) domain, and connecting peptide.20 The RAG1 and RAG2 recombinases facilitate the assembly of the V domain from gene segments that serve as the antigen recognition site. The C domain is used for the interactions with CD3 chains.

There are considerable structural differences between αβ and γδ chains in terms of C domain and connecting peptide, which are also reflected in the assembly of the TCR complexes, surface shape, and charge distribution.21–24 However, in both complexes, three dimers of CD3 proteins, δε and γε heterodimers and ζζ homodimers, are present.23,25 These CD3 proteins associate with TCR via non-covalent hydrophobic interactions and are required for a complete TCR localization on the cell surface (Fig. 1a).

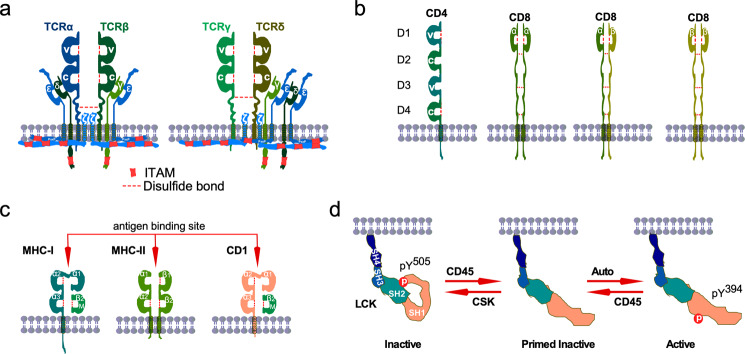

Fig. 1. TCR components.

a TCRα/TCRβ and TCRγ/TCRδ heterodimers form complexes with the CD3 molecules. Heterodimers of CD3ε/CD3δ and CD3γ/CD3ε, and a homodimer of CD3ζ/CD3ζ form complexes with TCR dimers. TCR heterodimers contain intramolecular and intermolecular disulfide bonds. CD3 chains contain 10 ITAMs distributed in different CD3 molecules. The variable region (V) of TCR heterodimers recognize the antigen peptide-loaded on MHC (pMHC). In the absence of pMHC, the intracellular part of the CD3 molecules forms a close conformation in which ITAMs are inaccessible to the kinases for phosphorylation. b Coreceptor CD4 acts as a single molecule while CD8α and CD8β can form homodimers or heterodimers. c MCH-I consists of an α-chain containing three immunoglobulin domains (α1, α2, α3) and β2-microglobulin (β2m). MCH-2 is the heterodimer of an α chain and a β-chain containing two immunoglobulin domains (α1, α2, and β1, β2) in each chain. d LCK-loaded CD4 molecules bind to the MHC-II bound TCR (TCRα/TCRβ) complex. This allows LCK to phosphorylate two distinct sites on ITAMs. Then ZAP-70 interacts with the phosphotyrosine sites and mediates more tyrosine phosphorylation. CD4 and MHC-II interaction is mediated through the membrane-proximal α2 and β2 domains of MHC-II and the membrane-distal D1 domain of CD4.

TCR co-receptors

Initial studies demonstrated that T cells expressing common TCRα/TCRβ heterodimer with distinct functions—for example, cytotoxic T cells that directly destroy infected cells and a subset of helper T cells that help B cells—may easily be distinguishable by the expression of mutually exclusive cell surface molecules CD8 and CD4.26–30 Later studies indicated that these two receptors may play important roles in the association of MHC molecules and thus are referred to as co-receptors.31–33 Both CD4 and CD8 molecules play important roles during the development of T cells by helping the TCR complex select a different class of MHC molecules.34 Like TCR molecules, both CD4 and CD8 molecules contain an extracellular domain, transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular tail.35 Although both CD8 and CD4 act as coreceptors with similar functionality, they share a minimal structural similarity. The extracellular domain of CD4 contains two V domains (D1 and D3) and two C domains (Fig. 1b). CD4 acts as a monomer on the T cell surface where it uses the D1 domain for MHC recognition and the cytoplasmic tail for interaction with non-receptor tyrosine kinase LCK.36 On the other hand, the CD8 extracellular domain contains only a single V domain. However, two CD8 isoforms, CD8α and CD8β, are expressed and can form homo- or heterodimers (Fig. 1b). Most CD8-positive T cells express as a heterodimer; some CD8-positive T cells—for example, intraepithelial lymphocytes and memory precursors—express as an αα homodimer.37–39

TCR ligands

Ligands for T cells are divided into two classes: MHC class I (MHCI) and MHC class II (MHCII) (Fig. 1c). Human MHCIs are complexes of human leukocyte antigens (HLAs: HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C) and β2-microglobulin while MHCIIs are heterodimers of several HLAs (HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DR).40 Antigen peptide-bound MHCI (pMHC-I) molecules can be presented on any nucleated cells recognized by CD8+ T cells. On the other hand, CD4+ T cells recognize antigen peptide-bound MHCII (pMHC-II) molecules that are presented on the APCs, such as B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.40 Besides peptide presentation by MHC molecules, lipid antigens present similarly structurally to MHCII molecules, such as CD1 family proteins.41,42

Lymphocyte-specific PTK (LCK)

LCK is a member of the SRC family kinase (SFK). The SFKs are a family of ten structurally similar non-receptor PTKs which have been implicated in various cellular functions.43–45 All SFKs contain highly conserved regulatory domains (SH3 and SH2), a protein tyrosine kinase domain (SH1), a C-terminal tail, and a poorly conserved N-terminal region (SH4 domain). The SH4 domain contains a myristoylation site by which SFKs anchor to the membrane.46 The SH3 domain, in general, recognizes proline-rich motifs (PxxP), and the SH2 domain interacts with phosphotyrosine residues.47,48 However, the function of the SH4 domain cannot be generalized for all SFKs except that it holds the myristoylation site. The SH4 domain of some SFKs also contains a palmitoylation in addition to the myristoylation site. Likewise, other SFKs’ LCK activity is tightly controlled by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles (Fig. 1d). C-terminal SRC kinase (CSK) phosphorylates LCK on Y505 residue that interacts with the LCK-SH2 domain, keeping it inactive.49 The leukocyte common antigen (CD45), also known as protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type C (PTPRC), removes the regulatory phosphotyrosine residue that releases the kinase domain from autoinhibitory states (priming) and also makes the SH2 domain available for interaction with other proteins.50–52 This priming step results in autophosphorylation of Y,394 leading to full activation of LCK.52 Besides a role in LCK activation, several studies have pointed out that CD45 can negatively regulate LCK function by removing tyrosine phosphorylation from LCK-Y394.53,54 T cells maintaining a certain level of CD45 expression uphold appropriate LCK activation whereas low levels of CD45 expression correlate with the lower TCR activation, and higher CD45 expression reduces LCK activity by removing tyrosine phosphorylation from LCK-Y394.53 Thus, T cells can regulate TCR activity by modulating CD45 expression.55 Several cytosolic phosphatases, including PTPN6(SHP-1), and PTPN22, also control LCK activity by removing phosphate group from Y394.56,57 Therefore, LCK activity is probably dynamically regulated by cellular abundance and activity of CSK, CD45, PTPN6, and PTPN22.

TCR activation and proximal signaling

Early T cell signaling takes place within a few seconds, and the first step is TCR activation.58 An early event in the proximal signaling of TCR is the involvement and activation of a set of PTKs.6 Several PTKs, such as LCK, FYN, and ZAP-70, are important signaling components for T cell development and activation of TCR signaling through tyrosine phosphorylation on CD3.8,59–61 The cytosolic tail of the CD3 proteins contains a unique motif, the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), that consists of two tyrosine residues flanked by leucine/isoleucine and spaced by bulky aromatic amino acid, thus having a consensus sequence of D/Ex(0-2)YxxI/Lx(6-8)YxxI/L.62–64 Each of the CD3δ, γ, and ε chains contain one ITAM each, whereas each CD3ζ chains contain three ITAMs, thus each TCR-CD3 complex contains ten ITAMs.6,65,66 For TCR activation, tyrosine residues in ITAMs need to be phosphorylated, which is initiated by LCK and, to some degree, by FYN.67–69 Although FYN can induce phosphorylation of ITAMs, its role is dispensable for T cell development.70,71 Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation on CD3 ITAMs by LCK during T cell development probably cannot be replaced by other tyrosine kinases.72

LCK is known to be associated with several growth factor receptors, including KIT, FLT3, and AXL, in a phosphorylation-dependent manner.73–75 The interaction between LCK and growth factor receptors is mediated via the SH2 domain of LCK that interacts with the phosphotyrosine residue of the activated receptor. Since the TCR-CD3 complex lacks intrinsic kinase activity, the pMHC-loaded TCR-CD3 complex remains unphosphorylated, and therefore LCK cannot directly interact with the inactive complex through an SH2 domain. However, to facilitate the phosphorylation of ITAMs, LCK needs to be localized to the cell membrane. LCK can anchor to the cell membrane via its myristoylation (serine 2) and palmitoylation (cysteine 3/5) sites present in the SH4 domain or through the interaction with the cytoplasmic tail of coreceptors CD4 and CD8.69,76–88 The C-terminal tail of CD4 and CD8α contains a conserved CxCP motif, which is absent in CD8β, required for this interaction.81,89,90 This motif interacts with the CxxC motif present in the LCK SH4 domain, mediating the interaction in a zinc-ion-dependent manner.89–94 Therefore, only the homodimer CD8α/CD8α and heterodimeric CD8α/CD8β can load LCK to the TCR complex, and although a CD8β/CD8β homodimer can be formed, it cannot recruit LCK to the TCR complex and thereby does not play a role in TCR signaling.

T cells usually express CD4 or CD8 coreceptors, and therefore pMHC-bound TCR browses for LCK-loaded coreceptors where the non-polymorphic part of pMHCs interacts with the distal membrane part of the coreceptors.76–79 The membrane-distal D1 domain of CD4 associates with the membrane-proximal α2 and β2 domains of MHC-II (Fig. 2), but it does not directly interact with the TCR complex.95–98 Similar to the CD4–MHC-II interaction, binding with the CD8α/CD8α homodimer or CD8α/CD8β heterodimer to the MHC-I complex is mediated through the membrane-distal D1 domain of CD8 and membrane-proximal β2M and α3 of the MHCI complex.99 Additionally, the membrane distal α2 domain of the MHC-I complex also participates in interaction with CD8.99 Such interaction keeps TCR and coreceptors orthogonal, which is likely important for the stability of the complex, LCK loading, and TCR activation.100–103 Although both the CD8α/CD8α homodimer or CD8α/CD8β heterodimer binds with MHC-1 complex with a similar affinity, the CD8β/CD8β homodimer does not bind with MHC-1.104–106

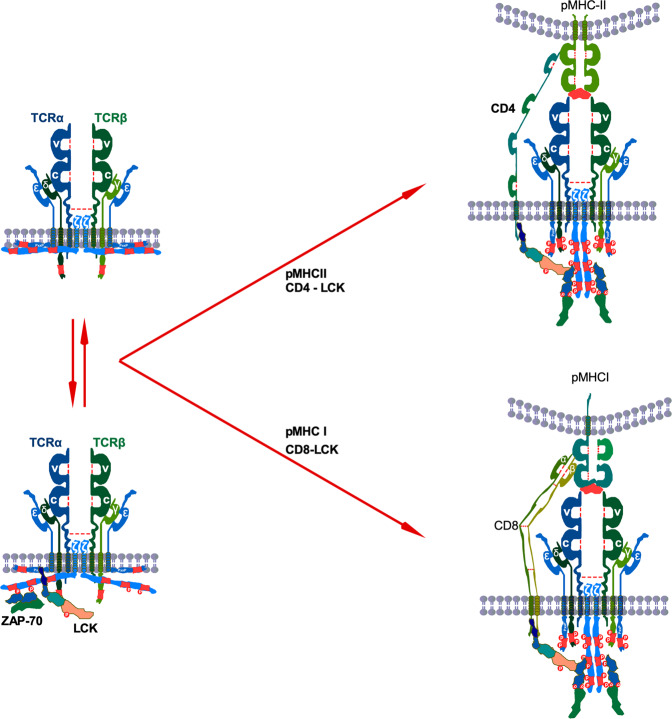

Fig. 2. TCR activation.

In resting T cells, CD3ζ and CD3ε remain membrane-embedded. Perhaps membrane-bound CD3ζ might be released to the cytosol, where free LCK induces tyrosine phosphorylation on at least two sites in ITAMs. This basal tyrosine phosphorylation creates docking sites for ZAP-70 interaction. After antigen engagement, the TCR complex recruits coreceptor-bound LCK that phosphorylates ZAP-70 and interacts with it through the SH2 domain facilitating tyrosine phosphorylation on other residues on ITAMs.

Interaction between coreceptors and LCK has two important functions: it brings LCK in close proximity to the TCR complex and it stabilizes coreceptors by preventing clathrin-mediated endocytosis.94 However, once LCK phosphorylates CD3 proteins, it leaves coreceptors that result in the internalization of coreceptors.107–111 Nevertheless, the interaction between LCK-loaded coreceptor and pMHC acts as a rate-limiting step to initiate TCR signaling.112

Initial studies suggest that coreceptor-bound LCK mediates tyrosine phosphorylation on all four CD3 chains.113–116 However, those studies have not suggested any site-specificity or whether LCK loaded to the CD4 or CD8 makes any difference in CD3 tyrosine phosphorylation dynamics. To address the sequence of CD3 tyrosine phosphorylation, several attempts have been taken with a specific focus on CD3ζ, which has six tyrosine phosphorylation sites.117,118 In resting T cells, at least two tyrosine residues in second and third ITAMs of CD3ζ remain to be phosphorylated.117 When activated, N-terminal tyrosine residue in the third ITAM displays dependency on the N-terminal tyrosine residue of the first ITAM, and C-terminal tyrosine residue in the second ITAM needs the C-terminal tyrosine residue to be phosphorylated on the first ITAM.117 Furthermore, LCK phosphorylates all six tyrosine residues of recombinant CD3ζ ITAMs in a specific order, starting from the N-terminal tyrosine residue of the first ITAM.118 These studies suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation in ITAMs is a controlled molecular event that has further been shown to be regulated by TCR ligand.117

LCK-induced phosphorylation of both tyrosine residues in ITAM has been shown to be required for interaction with ZAP-70 where ZAP-70 SH2 domains mediate the interactions.67,119 This interaction stabilizes tyrosine phosphorylation of CD3ζ and induces ZAP-70 tyrosine phosphorylation, which was independent of ZAP-70 kinase activity, suggesting that ZAP-70 does not play a role in CD3ζ tyrosine phosphorylation but that interaction with tyrosine residues probably limits phosphatase access, protecting tyrosine phosphorylation. Nevertheless, the interaction is important for ZAP-70 activation and downstream signaling.

The mechanism through which CD3 ITAMs remain unphosphorylated in an inactive TCR complex remains to be debated. Using CD3ε as a model, it has been depicted that the positively charged cytoplasmic domain remains embedded in the negatively charged inner membrane, which sequestrates tyrosine residues.120,121 Similarly, the cytoplasmic part of CD3ζ remains lipid-bound, preventing tyrosine phosphorylation.122 However, the role of the inner membrane in the prevention of tyrosine phosphorylation was questioned by another study.123 This study demonstrated that removal of positively charged residues did not enhance tyrosine phosphorylation but that pervanadate enhanced CD3 tyrosine phosphorylation, concluding that phosphatase might be involved in the prevention of tyrosine phosphorylation.123 Pervanadate prevents tyrosine phosphatases by oxidizing the catalytic cysteine of phosphatase.124 Those claims were later contested by the fact that removal of positively charged residues decreases LCK-mediated CD3 tyrosine phosphorylation, and pervanadate can prevent membrane association of CD3 with lipid membranes.125

Combining early studies, a model has been proposed suggesting that interaction between the cytoplasmic chain and lipid membrane prevents ITAM phosphorylation, and pMHC association to the TCR induces structural changes that release CD3 from the inner membrane.126,127 This model has further been supported by the fact that positively charged ions, such as Ca2+, can release sequestered CD3 chains, facilitating tyrosine phosphorylation,128 and that defects in Mg2+ transport are linked to the defective T cell activation due to impaired Ca2+ influx in T cells.129 Antigen engagement increases Ca2+ intake86 as well as TCR proximal Ca2+ concentration.130

Although this model provides a simplified overview of TCR activation, the model fails to explain how ITAMs in CD3δ and CD3γ remain protected from tyrosine phosphorylation, as they lack membrane-binding residues,126,131 and how a basal level of CD3ζ tyrosine phosphorylation is maintained if they remain to be sequestered in the plasma membrane.60,117,120,132–134 Thus, complete sequestering to the plasma membrane might be an unlikely event. Rather, dynamic switching between membrane binding and cytosolic release might happen, and other forces may also be involved.135

Constitutive association of ZAP-70 to the CD3ζ might also go against the model of complete sequestering, as ZAP-70 association is mediated through the SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine residues.132 Furthermore, constitutively active LCK localized at the cell membrane was detected in up to 40% of resting T cells.53 Constitutively LCK activation is probably required for maintaining basal tyrosine phosphorylation of CD3ζ, as T cells with reduced constitutively LCK activation displayed undetectable levels of CD3ζ tyrosine phosphorylation.53 But why is TCR signaling not triggered in resting cells if free LCKs are available and apparently are more active than coreceptor-bound LCKs136? Perhaps membrane association CD3ζ limits the accessibility to the tyrosine sites in ITAMs, and, if they are accessible in resting cells, CD3ζ orientation allows phosphatases to remove tyrosine phosphorylation.123 Therefore, the association of pMHC to the TCR complex that mediates structural changes of the cytosolic part of CD3 is important for TCR activation.

A two-stage kinetics of TCR–pMHC–CD8 interaction has been suggested, where the first TCR binds with the pMHC (within <0.1 s), and then the tri-molecular complex is formed.137 The tri-molecular complex was affected by proximal signaling, as pharmacological inhibition of SFKs or CD45 abolished initiation of high-affinity binding.137 LCK association to the coreceptor stabilizes coreceptors by preventing endocytosis.94 However, how the kinase activity of LCK stabilizes the tri-molecular complex remains to be determined. As an early event, CD8 interacts with CD3ζ, which is independent of pMHC but LCK-dependent, and in the later events, tri-molecular complex is required to maintain the CD8–CD3ζ interaction.138 As LCK can be either free or CD8 bound,138 CD3ζ might get a chance to meet either free LCK or coreceptor bound LCK before ligand association, probably further explaining CD3ζ tyrosine phosphorylation in resting cells.

A single-molecule analysis suggests that the movement of LCK during TCR activation is not directed but is rather a Brownian movement.139 Therefore, it would be challenging for a TCR complex to find LCK instantly unless LCK is already recruited to the complex in resting cells. Free LCKs which are also membrane-bound display higher mobility than coreceptor-associated LCKs, probably due to the difference in molecular size.136 This might also explain why free LCKs are recruited in the early TCR complexes.138 Besides the ability to move faster, free LCKs display higher catalytic activity as measured by tyrosine phosphorylation (LCK-Y394).136 However, in any case, coreceptor-bound LCK is required for TCR activation, and the number of coreceptors-bound LCK increases during the maturation process.140 Finally, it has been demonstrated that LCKs directly interact with CD3ε in which the interaction is ionic and is mediated through the juxtamembrane basic residue-rich sequence (BRS) of CD3ε and the unique domain (UD) of LCK.141

The early steps of the TCR activation process seem to be highly debated. Current models for TCR activation either considered CD3 membrane sequestering and ignored the basal level of CD3ζ or the other way around.126,127,135 Perhaps both of the conditions simultaneously occur, and therefore probably CD3ζ holds its states as membrane-embedded and outside the membrane, allowing constitutively active LCK to phosphorylate tyrosine residues on CD3ζ ITAMs (Fig. 2). Then ZAP-70 binds to the phosphotyrosine residues in CD3 ITAMs. Once bound, ZAP-70 is phosphorylated by LCK, which leads to its activation.142 This results in the formation of a multi-nucleated signaling complex as further phosphorylation of ZAP-70 allows binding of additional proteins and adaptors, thereby itself behaving as a scaffold.142,143 Thus, the activated state of TCR is characterized by phosphorylation of ITAMs, followed by phosphorylation and activation of ZAP-70.

Distal TCR signaling

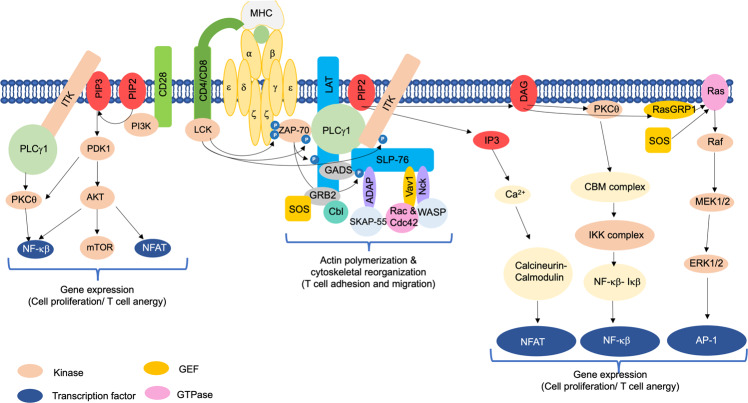

Engagement of TCR with the MHC-antigenic peptide complex of APCs triggers the formation of multi-molecular signalosomes at TCR. This leads to the generation of proximal signaling, followed by the activation of multiple distal signaling cascades, such as Ca2+–calcineurin–NFAT, PKCθ–IKK–NFκβ, RASGRP1–RAS–ERK1/2, and TSC1/2–mTOR, with the help of secondary messengers, enzymes, and various adaptor proteins (Fig. 3). These signaling cascades finally bring out the diverse phenotypic effects, as they control many aspects of T cell biology.1

Ca2+–calcineurin–NFAT pathway

Phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) is the main molecule connecting the TCR proximal to distal signaling cascades.144 The membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) gets hydrolyzed by activated PLCγ1 into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-3-phosphate (IP3).145 Both of these essential secondary messengers initiate a variety of distal signaling cascades important for T cell activation. Membrane-bound DAG can activate PKCθ, RASGRP1, and PDK1-mediated pathways. On the other hand, IP3 triggers the activation of a Ca2+-dependent calcineurin NFAT pathway.145–147

IP3 generated from PIP2 binds to the Ca2+-permeable ion channel receptors (IP3R) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thereby releasing ER Ca2+ stores in the cytoplasm.148 It has been found that ERs can sense the intracellular Ca2+ levels through the constitutive expression of a transmembrane protein called stromal interaction molecule (STIM). Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ levels thus triggers an influx of extracellular Ca2+ into T cells from Orai1 type plasma membrane calcium-release activated calcium (CRAC) channel.149–152 Increased intracellular Ca2+ activates a protein phosphatase, calcineurin, that dephosphorylates the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), thereby causing its nuclear translocation. Nuclear NFAT forms a complex with AP-1 transcriptional factors (JUN/FOS) derived from the DAG–RAS–MAPK–ERK1/2 pathway. This transcriptional complex is responsible for inducing the expression of various genes, like IL-2 and other effector molecules, that are responsible for T cell activation. In contrast, in the absence of AP-1, NFAT alone activates various genes, like several ubiquitin ligases and diacylglycerol kinase α (DGKα), that are responsible for T cell anergy, a state of T cell unresponsiveness, one of the processes to induce immune tolerance.153–156 Thus, two opposite T cell functions—activation and anergy—are controlled by NFAT proteins.153

In addition to calcineurin, Ca2+ also activates a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) that mediates T cell activation through activation of transcription factors, such as cyclic-AMP-responsive-element-binding protein and myocyte enhancer factor 2.157 A missense mutation in Orai1 can lead to impaired Ca2+ signaling, which affects nuclear translocation of NFAT, and thereby NFAT-induced cytokines production causes severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in humans.158,159 Thus, the universal secondary messenger Ca2+ regulates several important functions, including proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine production in T cells.160

PKCθ–IKK–NF-κβ pathway

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a family of ten protein serine/threonine kinases that plays numerous roles in physiological and pathological conditions.161–164 PKC family proteins are divided into three subfamilies: classical (PKCα, PKCβ1, PKCβ2, and PKCγ), novel (PKCδ, PKCε, PKCη, and PKCθ), and atypical (PKCζ and PKCι). DAG and Ca2+ regulate activation of classical PKC isoforms, and novel PKC isoforms are regulated by DAG while atypical PKC isoforms are independent of DAG and Ca2+ for activation.161 Several PKC isoforms have been implicated in T cell functions.165 For example, the novel isoform PKCθ binds to DAG through the PKC conserved region 1 (C1) domain, which is required for its recruitment to the lipid raft after TCR engagement. PKCθ plays major non-redundant roles in T cell activation, even though T cells express several other PKCs.166,167

Nuclear factor κβ (NF-κβ) is an evolutionarily conserved transcription factor that plays important roles in regulating genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses, cell growth, survival, and differentiation.168 TCR-mediated T cell activation involves both the canonical (classical) and the non-canonical (alternative) NF-κβ pathway. An essential factor required for complete T cell activation via the non-canonical NF-κβ pathway is MAP3K14 (also known as NF-κβ-inducing kinase; NIK).169 However, more studies are required regarding this. On the other hand, PKCθ–IKKβ–NF-κβ forms the canonical branch of the NF-κβ pathway and is widely studied.170

Once PKCθ is activated following TCR stimulation, it triggers the formation of a tri-molecular complex of adaptor proteins in the cytoplasm called the CBM complex, which is composed of the caspase recruitment domain-containing membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein-1 (CARMA1), B cell lymphoma/leukemia 10 (BCL10), and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue translocation protein-1 (MALT1).171 This is initiated by phosphorylation of CARMA1 by activated PKCθ,172 which is required for its oligomerization and association with BCL10.173 MALT1 then binds to BCL10, and this association recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, called the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), that polyubiquitinates and degrades IKKγ, or the NF-κβ essential modifier (NEMO), a regulatory protein of the IKK complex.174,175 Consequently, the catalytic subunits of Iκβ kinases (IKK), α and β, are no longer inhibited, and they phosphorylate Iκβ, thereby inducing its ubiquitination and degradation. NF-κβ is thus released from its inhibitory Iκβ complex in the cytoplasm, and it translocates into the nucleus to regulate gene expression.176–178 This canonical PKCθ–IKKβ–NF-κβ pathway is extremely important for T cell survival, homeostasis, activation, and effector function.179 Deregulation of this pathway can cause defective T cell survival and activation, autoimmunity, SCID, and lymphoma.180–182

RASGRP1–RAS–ERK1/2–AP1 pathway

DAG from PIP2 induces the activation of another key molecule, a RAS guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein (RASGRP1), and recruits it to the plasma membrane.183,184 RASGRP1 and Son of Sevenless (Sos) are two known guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) responsible for RAS activation in T cells.1 RAS, a small G protein, binds to GTP in the activated state and initiates the RAS-MAPK cascade by activating the serine/threonine kinase Raf1.183,185 Raf1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase kinase (MAPKKK), then phosphorylates and activates MAPK kinases (MAPKKs), such as MEK1/2, that further phosphorylate and activate MAPK extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 & 2 (ERK1/2).6,185,186 T cell development, differentiation, and TCR-induced signal strength are all controlled by ERK1/2 signaling.187–189 Furthermore, ERKs trigger the phosphorylation and activation of their downstream target Elk, a transcription factor responsible for inducing the expression of c-Fos transcription factor. The VAV1–Rac pathway induces the expression of Jun.190 Thus, the formation and activation of a dimeric complex, activator protein-1 (AP-1) composed of Jun/Fos, that plays a critical role in immune response, followed by IL-2 transcription, is sustained by the DAG–RAS pathway.1,6 Further, the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3) and LCK get phosphorylated by ERKs.191,192

RASGRP1 is extremely important for the development of conventional αβ T cells but not the meager population of γδ T cells.193–195 However, it is important for the activation of both types of T cell population as well as for the expression of IL-17.195 RASGRP1 deficiency can cause defects in the activation of various signaling pathways, such as RAS–MAPK–ERK1/2, mTOR, and PI3K/AKT.193,196 Moreover, abnormal expression of both RASGRP1 and RAS was described in T cells of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients, thereby implicating the involvement of this pathway in the generation of SLE.197

p38 and JNK pathways

The other MAPKs such as p38 and JNK family proteins play important roles in the proliferation, differentiation, and function of different subsets of T cells.198–202 p38 is a family of four highly structurally homolog proteins including p38α (MAPK14), p38β (MAPK11), p38γ (MAPK12), and p38δ (MAPK13).203 p38α is widely known as p38 and is one of the most studied isoforms. On the other hand, the JNK family is composed of three members which include JNK1 (MAPK8), JNK2 (MAPK9), and JNK3 (MAPK10).204 Three dual-specificity MAP2Ks including MKK3 (MAP2K3, MEK3), MKK4 (MAP2K4, MEK4), and MKK6 (MAP2K6, MEK6) are involved in p38 activation through phosphorylation on the conserved T180-X-Y182 motif in the loop of the substrate recognition site.203 Among those three MAP2Ks, MKK3 and MKK6 display higher specificity to p38 while MKK4 also activates JNKs.203–206 The conserved T180-X-Y182 motif is required to be phosphorylated on both threonine and tyrosine residues for p38 activation.207 In mammalian cells, the classical p38 pathway is regulated by ten different MAP3Ks that allow for the integration of various signaling nodes. However, in T cells, p38 activity is mediated by a non-classical pathway which is downstream of proximal TCR signaling and probably independent of MAPK cascades.203 In such a case, activation of TCR proximal signaling results in the phosphorylation of p38 at Y323 residue by ZAP-70, which triggers autophosphorylation on regulatory residues (T180-X-Y182) followed by p38 activation.208 Additionally, activated p38 mediated phosphorylation of ZAP-70 on T293 residue may act as a negative feedback loop possibly by limiting excessive TCR signaling.209 JNK activation is likely mediated through the activation of PKCθ and CBM complex upon the activation of TCR proximal signaling (reviewed in ref. 210). BCL10 oligomers in the CBM complex can recruit TAK1 (MAP3K7), MKK7 (MAP2K7), and JNK2, leading to the activation of JNK.210,211

TSC1/2–mTOR pathway

Upon TCR engagement, both DAG–RASGRP1–RAS–ERK1/2 and PI3K–AKT pathways induce the activation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 (refs. 196,212) that differentially regulate the generation of CD4+ helper effector T cell types (Th).213 mTORC1 down-regulates SOCS5 to promote STAT3 activity, thereby promoting Th17 differentiation.214 Resultingly, mice having Rheb or raptor-deficient T cells show defects in Th17 differentiation.214,215 On the other hand, mTORC2 phosphorylates AKT at S473 and PKCθ at S660/676 to induce Th1 and Th2 differentiation respectively.215 Thus, mice having rictor-deficient T cells show defects in differentiation of IFNγ-producing Th1 and IL-4-producing Th2 effector cells.214,215 The activity of mTOR subsequently needs to be tightly controlled, as it regulates T cell activation, differentiation, and function.216

As discussed above, the CBM complex plays a crucial role in TCR signaling by recruiting key signaling mediators. Hamilton et al.217 demonstrated that CARMA1 and MALT1 in CBM complex, but not BCL10, are required for optimal activation of mTOR in T cells. Furthermore, the CBM complex is involved in TCR-induced glutamine uptake and the activation of mTOR pathways.218 Nevertheless, mTOR regulates intracellular metabolic signaling which links to biosynthetic and bioenergetic metabolisms (reviewed in refs. 219–221).

Signaling by the co-stimulatory molecules

TCR engagement leads to activation of proximal and distal signaling pathways. However, productive T cell activation also involves the engagement of additional cell surface receptors, i.e., co-stimulatory molecules like CD28. This is required to avoid anergy, a state of T cell unresponsiveness where T cells become refractory to restimulation by IL-2. If the TCR signals are weak, it results in cell death or anergy. These weak TCR signals are amplified strongly by CD28 engagement, thereby resulting in cell proliferation and differentiation. However, only CD28 engagement results in the expression of a few genes transiently with no biological consequences.222

The key event coupling CD28 to several downstream signaling pathways is the recruitment of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) to the phosphorylated cytoplasmic tail of CD28, which converts PIP2 to PIP3. Once AKT is recruited to PIP3, it acts on several substrates. AKT facilitates prolonged nuclear localization of NFAT, and thus IL-2 transcription, by inactivating GSK-3. IL-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK) is also associated with PIP3, and this kinase is important for phosphorylation and activation of PLCγ1.170 Apart from this, NF-κβ is one of the major signaling pathways regulated by co-stimulation signaling in T cells. AKT associates with CARMA1 and hence facilitates the formation of the CBM complex, which enhances the nuclear translocation and activation of NF-κβ. However, AKT is non-essential for NF-κβ signaling in T cells.223 The most important mediator of the NF-κβ signaling pathway is phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1), whose recruitment and phosphorylation enable its efficient binding to both CARMA1 and PKCθ, thus inducing NF-κβ activation.224,225 Indeed, activation of NF-κβ and PKCθ was found abrogated upon deletion of PDK1 in T cells.224 VAV1 is a GEF for small GTPases, such as Rac1, Rac2, and Rhog, where it plays a crucial role in strongly amplifying CD28-mediated activation of NFAT and NF-κβ signaling pathways.226,227 Thus, signaling by co-stimulatory molecules quantifies the signals that are already activated by TCR ligation, thereby strongly sustaining T cell activation. These include the PI3K–AKT–mTOR, NFAT, NF-κβ, and MAPK pathways (Fig. 3). While PI3K signaling is primarily mediated by CD28, initial activation of PI3K results in upregulation of phosphoinositide-3-kinase adaptor protein-1 (PIK3AP1, also known as BCAP).228 PIK3AP1 potentiates PI3K signaling in response to CD3 engagement in CD8+ T cells.228

Positive regulators of T cell signaling

Two of the most important adaptors that are phosphorylated by activated ZAP-70 and play a critical role in positively regulating TCR signaling are a transmembrane adaptor protein, linker for activation of T cells (LAT), and a cytosolically localized SH2 domain-containing leukocyte phosphoprotein of 76 kDa (SLP-76)229,230 (Fig. 3). These adaptor proteins form the backbone of the proximal signaling complex (proximal signalosome) that recruits various other effector proteins,231,232 along with phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1), which links the proximal with several distal signaling pathways upon TCR engagement.144 This results in a stable and dynamic zone of contact between APCs and T cells, designated as the immunological synapse (IS).

Lipid rafts are microdomains located within the plasma membrane that are enriched with cholesterol, glycosphingolipids, and sphingomyelin, and these rafts accumulate at the IS. They are also known as glycolipid-enriched microdomains (GEMs), detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs), or detergent-insoluble glycolipid-enriched membranes (DIGs). Key components of the TCR signaling pathway, such as LCK, LAT, RAS, CD4, and FYN, along with some others, are located within the lipid rafts.6 Post-translational modification of lipids in these molecules is very important for their localization in the lipid rafts. RAS is both palmitoylated and farnesylated, whereas most of the SRC PTKs, including the T cell-specific LCK, undergoes myristoylation and palmitoylation, necessary for its localization in the lipid rafts and subsequent targeting and phosphorylation of the CD3 ζ chain.233–235 TCR engagement and activation result in its rapid association with the lipid rafts, and this localization is important for the early tyrosine phosphorylation events of the TCR subunits by the SRC family PTKs.236,237 This can be achieved by the PTK LCK that is present in the rafts, where its SH2 domain binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine residues in activated ZAP-70, thereby bringing TCRs bearing activated ZAP-70 to the lipid rafts.238,239

The GM-CSF/IL3/IL5 common β-chain-associated protein (CBAP) is involved in the regulation of TCR downstream signaling, as CBAP-deficient cells display reduced phosphorylation of PLCγ1, LAT, JNK1/2, and ZAP-70,240 suggesting that it may play a role in both proximal and distal signaling. Besides its role in normal physiology, CBAP plays an important role in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) pathology. CBAP was found to be highly expressed in T-ALL, and its expression enhanced T-ALL cell growth.241 Similar to TCR signaling, loss of CBAP decreased ERK1/2, S6K, RSK, and TSC2 phosphorylation and thereby decreased aerobic glycolysis and energy metabolism.241

LAT

The first adaptor essential for the successful transmission of TCR signals is the LAT.13 It is a transmembrane protein of 36–38 kDa242 consisting of a tyrosine-rich cytoplasmic tail and a short extracellular region.229 It requires palmitoylation on its two cysteine residues (C26 and C29) for localization to the lipid rafts. Mutation of C26 fully inhibited the localization of LAT to the lipid rafts, whereas C29 mutation had a partial effect. Moreover, no tyrosine phosphorylation of LAT was detected when C26 was mutated, indicating that raft localization of LAT is vital for its phosphorylation.243 Several molecules have been proposed that link TCR and LAT by binding to both of them. PLCγ1 binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residue 132 of LAT244 via its N-terminal SH2 domain and to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on activated ZAP-70 via its C-terminal SH2 domain.245 An Abl-SH3 interacting protein, 3BP2 has also been found to interact with both LAT and ZAP-70 via its SH2 domain, probably in a multimeric form.246 Another important molecule found to link TCR and LAT is a small adaptor protein, Shb, that binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine residues on the CD3 ζ chain via its SH2 domain and also binds phosphorylated LAT via its non-SH2 phosphotyrosine binding domain.247 TCR engagement results in rapid phosphorylation of LAT on its tyrosine residues by ZAP-70.248 Thus, LAT phosphorylation and distal signaling events were inhibited when mutant Shb was expressed with a defective SH2 domain.247 Once phosphorylated, LAT then binds to several proteins, such as enzymes and adaptor molecules, via diverse binding sites as discussed below, therein bringing them to the plasma membrane.

Overexpression of LAT did not augment TCR-mediated downstream signaling pathways.249 Moreover, LAT-deficient Jurkat cells also displayed TCR-induced receptor phosphorylation and ZAP-70 activation but were found to be defective in all steps distal from this. There was no activation of PLCγ1 with reduction of Ca2+ mobilization, ERK activation, NFAT activation, and reduced IL-2 gene transcription.249,250 Reconstitution with LAT restored these defects. Moreover, LAT-deficient mice blocked thymic differentiation at the pre-TCR stage, thereby showing no T cells in the lymph nodes and spleen.250 LAT, then, is important for TCR-mediated signaling and intra-thymic development of T cells.

Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2) and GRB2-related adaptor downstream of Shc (GADS)

GRB2 and GADS are cytosolic adaptor proteins, with the former expressed ubiquitously and the latter expressed only in the hematopoietic cells, playing an important role in hematopoietic growth factor receptors signaling.251,252 Activated/phosphorylated LAT binds to both the GRB2 family proteins via their SH2 domains, thereby translocating them to the plasma membrane, along with their SH3 domain-associated proteins.6 GRB2 is constitutively associated with Sos, a dual-specific GEF for small GTPases such as RAS and Rho. Upon TCR activation, Grb2-Sos complex associates with LAT, leading to activation of RAS. However, Grb2 seems insufficient for RAS activation in T cells, as LAT mutants failed to induce complete RAS activation.183,253 An additional small linker molecule, Shc, was found to mediate the association of Sos with GRB2 in T cells.254 An E3 ubiquitin ligase, CBL (discussed later), is another GRB2 associated protein that binds to phosphorylated LAT in T cells.255 Upon TCR stimulation, another member of the GRB2 family, GADS not only binds to phosphorylated LAT but also specifically binds to a critical adaptor molecule of T cells, SLP-76,256 thereby associating LAT with SLP-76. GADS has also been found to associate with a serine/threonine kinase, hematopoietic progenitor kinase-1 (HPK1), involved in JNK pathway activation.256,257 T cell development was found impaired, with specific defects in both positive and negative selection of thymocytes, in GADS-deficient mice.258

The three distal tyrosine residues of LAT (171, 191, and 226) are involved in binding to Grb2, whereas Tyr 171 and 191 are involved in binding to GADS.244 Mutation in any one of the tyrosine residues did not affect either Grb2 or GADS binding, whereas loss of both 171 and 191 decreased GRB2 binding, and mutation of both these residues completely abolished GADS binding. The binding of GRB2 was only abolished when all three tyrosine residues were mutated. Since these tyrosine sites might directly interact with PLCγ1 through its C-terminal SH2 domain or indirectly via GADS–SLP-76–PLCγ1 interaction, mutations of these tyrosine residues also impacted PLCγ1 binding due to loss of SLP-76 binding, with PLCγ1 activation completely inhibited, calcium flux partially inhibited, and PLCγ1-LAT association being undetected.244

SH2 domain-containing leukocyte phosphoprotein of 76 kDa (SLP-76)

SLP-76 is another crucial multidomain adaptor protein of 76 kDa, localized in the cytoplasm13,230 and expressed only in cells of the hematopoietic system, such as thymocytes, mature T cells, natural killer cells, megakaryocytes, and macrophages but not B cells.259 It plays a very important role by linking LAT, activating PLCγ1, and other downstream signaling pathways.13 The proline-rich region of SLP-76 binds to the SH3 domain of PLCγ1,260 leading to the formation of the LAT–GADS–SLP76–PLCγ1 complex. Thus, the two complexes described above, LAT-GADS-SLP-76 and LAT-PLCγ1, interact with each other via binding of SLP-76 to PLCγ1.261 SLP-76-deficient Jurkat cells subsequently displayed severe impairment of PLCγ1 phosphorylation, resulting in decreased calcium flux and IL-2 production, following TCR engagement.262 Overexpression of SLP-76 in Jurkat cells increased TCR-mediated NFAT activity and IL-2 transcription as well as ERK activation, but calcium flux remained unchanged.263,264 Moreover, SLP-76-deficient mice showed an intra-thymic block at an early developmental stage of T cells (double negative stage), thereby failing to generate normal, peripheral T cells, displaying the same phenotype as the LAT-deficient mice.265,266 Such findings demonstrate that SLP-76, like LAT, is important for TCR-mediated signaling and intra-thymic development of T cells.

Upon TCR stimulation, SLP-76 gets phosphorylated by ZAP-70 at its multiple tyrosine residues, which serve as binding sites for various SH2 domain-containing proteins. These include proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements, such as VAV1, non-catalytic tyrosine kinase (NCK), and the PTK ITK (described below).267–269 On the other hand, the SH2 domain of SLP-76 associates with the phosphorylated tyrosine residues of a 130 kDa multidomain adaptor protein, named SLP-76-associated phosphoprotein (SLAP)/FYN-binding protein (FYB)/Adhesion and degranulation promoting adaptor protein (ADAP).270,271 SLP-76 thus regulates cytoskeletal changes in activated T cells by coordinated and precise loading of the effector molecules VAV, NCK, and ADAP into the complex, vital for the stability of the complex and its optimal activation.1

Connecting link PLCγ1

Since both LAT and SLP-76 form the backbone of the proximal signaling complex, deficiency of both the adaptors in Jurkat cells and mouse models showed diminished activation of RAS signaling due to impairment in formation of the proximal signalosome.265,272 As the connecting link between proximal and distal signaling pathways, PLCγ1 is the central signaling molecule in T cells, and phosphorylation on its multiple tyrosine residues is required for its full activation.273 This is mediated by the TEC PTK family members, such as IL-2 inducible T cell kinase (ITK) and resting lymphocyte kinase (RLK)/TXK. Deletion of both ITK and RLK exhibited complete loss of PLCγ1 activity along with defects in calcium flux following TCR engagement.274–277 In contrast, overexpression of RLK enhanced PLCγ1 phosphorylation and calcium flux.278 Plasma membrane localization of ITK and RLK/TXK is possible via its N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain and palmitoylation respectively. ITK interacts with many different molecules via its various binding domains. The Tec homology (TH) region of ITK is a proline-rich region that interacts with the SH3 domain of Grb2. The SH3 domain of ITK, in turn, interacts with the proline-rich regions of PLCγ1.260 LAT interactions with ITK have also been reported; nevertheless, the exact mechanisms are still unknown.279 Moreover, the SH2 domain of ITK interacts with tyrosine-phosphorylated SLP-76.268,269 Thus, ITKs can interact with the LAT-associated molecules via multiple mechanisms. ITKs in turn are activated by both SLP-76 and LCK.280,281 When ITK associates with SLP-76, it is present in close proximity to its substrate PLCγ1, and direct phosphorylation of ITK at Y511 by LCK promotes its activation.269,282 Moreover, apart from ITK, the association of PLCγ1 with LAT, GADS, and SLP-76 is also required for its optimal activation.253 In response to TCR engagement, PLCγ1 activation is thus regulated by the signaling complex (signalosome) composed of LAT, GADS, SLP-76, PLCγ1, and ITK.6

Signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM)-associated protein (SAP)

Signals from both the TCR-CD3 complex and co-stimulatory receptors, such as CD28, CD2, and the CD150/SLAM (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule) family, are required for full activation of T cells.283 SAP is a small cytoplasmic protein of 128 amino acids284 that associates via its SH2 domain with the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motifs (ITSMs) present in the cytoplasmic tail of the SLAM family of receptors. Once bound to a specific ITSM, it may prevent binding of the SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2) and thereby compete with it. On the other hand, it may favor the recruitment of SH2 domain-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP), causing the switch between these two signaling pathways.285,286 The SLAM family consists of a number of transmembrane costimulatory receptors, such as CD150/SLAM, CD244/2B4, CD84, CD229/Ly-9, CD319/CRACC, and NTB-A.287 Thus, SAP can bind via its SH2 domain to the ITSMs of various SLAM families of receptors, and this interaction plays a crucial role in mediating the costimulatory signals necessary for T cell activation.283 Moreover, SAP also exerts its adaptor role by binding to various SH3 domain-containing proteins, such as FYN, PKCθ, βPix, and NCK1,288–291 thus recruiting them to the SLAM family of transmembrane receptors.292

Along with SLAM, SAP has also been found to directly associate with the first ITAM (Y72-Y83) of the CD3ζ chain in various T cell lines and peripheral blood lymphocytes. Knockdown of SAP resulted in a decrease of several canonical T cell signaling pathways, such as AKT and ERK; reduced the recruitment of PLCγ1, SLP76, and Grb2 to the phosphotyrosine containing complex; and also reduced IL-2 and IL-4 mRNA induction. Through its direct association with the CD3ζ chain, SAP was found to play a central role in T cell activation.292 Indeed, mutations or deletions of the SH2D1A gene encoding SAP resulted in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome-1 (XLP1), which is characterized by immunodeficiency due to a specific defect in T cells (apoptosis resistance and impaired interaction with B cell), reduced cytotoxicity of natural killer cells, a decrease in B cell functions, and defective NKT cell development.293,294

SAP and NTB-A (SLAMF6) are essential proteins that potentiate the strength of proximal TCR signals required for restimulation-induced cell death (RICD).295 RICD is an important consequence of repeated TCR signaling essential for TCR-induced apoptosis in thymocytes, mature T cells, T cell malignancies, and T cell therapies (reviewed in refs. 296–298). Therefore, T cells with impaired SAP function display resistance to RICD, which likely explains severe CD8+ T cell lymphoproliferation in XLP1 patients.295

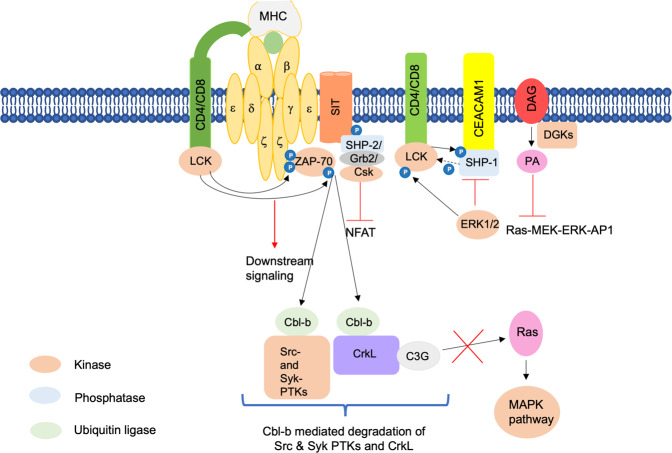

Negative regulators of T cell signaling

Inappropriate activation of T cells is prevented by the termination of TCR signals, and this is mediated by certain proteins that negatively regulate TCR signaling (Fig. 4).

Adaptors serving as negative regulators

Phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains (PAG)/CSK-binding protein (CBP)

An important transmembrane adaptor protein negatively regulating TCR signaling is PAG/CBP which is found in the lipid rafts.299,300 In the absence of TCR engagement or in resting T cells, PAG is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in its cytoplasmic tail. This serves as a docking site for the SH2 domain of the major negative regulator of SRC kinases, the tyrosine kinase c-terminal SRC kinase (CSK), thereby localizing to the rafts and activating.301–303 Once activated, CSK phosphorylates LCK at the C-terminal Y505 residue, which leads to its kinase domain inactivation as it causes LCK to bind to its internal SH2 domain.49,69,301–303 Thus, CSK gets activated upon binding to PAG in the lipid rafts, and it inhibits the activity of SRC family kinases. However, upon TCR activation, tyrosine phosphatase CD45 transiently dephosphorylates PAG. This results in the dissociation of CSK from the glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains (GEMs), relieving the inhibition of SRC kinases for signal transmission.304 Moreover, the inhibitory Y505 residue of LCK also gets dephosphorylated by CD45 tyrosine phosphatase, which, furthermore, slightly dephosphorylates positive regulatory autophosphorylation at Y394.53,305 Thus, the PAG-CSK complex maintains T cell quiescence by transmitting negative regulatory signals.13

SH2 or SHP-2-interacting transmembrane adaptor protein (SIT)

Another transmembrane adaptor protein negatively regulating TCR signaling is SIT expressed in lymphocytes.306–308 It associates with the TCR complex as a disulfide-linked homodimer.306 The cytoplasmic tail of SIT contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs) that, upon tyrosine phosphorylation, associate with SHP-2. SIT mediates its negative regulation of TCR signaling through the inhibition of NFAT activity. That, however, remains unaffected after mutation of the tyrosine residue within the ITIM motif, which completely abrogates binding to SHP-2. Thus, SIT-SHP-2 interaction seems unimportant for SI-mediated negative regulation of T cell signaling.306 GRB2 was also found to be associated with SIT via two consensus YxN motifs whose mutations abrogated the binding. This also had no effect on the inhibitory function of SIT.308 Moreover, the effector molecule that might mediate the negative regulatory function of SIT was found to be CSK via co-precipitation experiments.308 However, the precise mechanism of SIT-mediated negative regulation of TCR signaling needs to be elucidated,13 as its role in lymphocyte function seems to be more complex.10

Enzymes serving as negative regulators

Enzymes such as phosphatases, kinases, and ligases also play important roles in negatively regulating TCR signaling.

Phosphatases

Apart from CD45 and SHP-2 already mentioned above, there are other tyrosine phosphatases that mediate negative regulation. Adhesion molecules called carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1 (CEACAM1) are expressed at later time points of TCR stimulation.309 The SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP-1) is recruited to the phosphorylated ITIMs of CEACAM1, and it dephosphorylates LCK at Y394, inactivating it57,309,310 and thus terminating TCR signaling. The binding of TCR to antagonists or weak antigens induces LCK-mediated phosphorylation of SHP-1 at Y564, thereby activating it, which, in turn, dephosphorylates and inactivates LCK.309,310 Moreover, SHP-1 binding to LCK is prevented by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of LCK at S59, sustaining TCR signaling. SHP-1 activity is thus indirectly regulated by ERK1/2.311 Additional phosphatases that negatively regulate TCR signaling include PTEN, which dephosphorylates PIP3, and dual-specificity phosphatases, which dephosphorylate MAPKs.312,313

Diacylglycerol kinases

Subcellular levels of DAG are regulated by lipid kinases, DGKs that phosphorylate DAG to produce phosphatidic acid (PA).314,315 Consequently, the increase in DGK activity attenuates RAS–MEK–ERK–AP1 signaling induced by TCR-mediated DAG activation.316,317 Ten DGK isoforms are expressed in mammals,315 with DGK α and ζ being expressed at high levels in T cells.318 Both isoforms negatively regulate the DAG–RASGRP1–RAS–ERK1/2 pathway and thus inhibit activation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes.196 Indeed, the genetic ablation of these isoforms resulted in increased activation of the RAS–MEK–ERK–AP1 pathway, mTOR signaling, and PKCθ–NF-κβ pathway. This led to the loss of T cell anergy and increased T cell hyperactivation.145,155,156,319,320 Both DGK α and ζ perform redundant roles in T cells, as their deficiency resulted in severe T cell developmental blockade at the DP stage, which was partially restored with the phosphatidic acid treatment.321 DGK activity can be regulated by SAP. Overexpression of SAP reduces DGKα activity which was shown to be dependent on the SH3-binding ability of SAP in T cells, suggesting that SAP acts as a negative regulator of DGKα.322 As SAP-deficient XLP1 displays resistance to RICD, pharmacological inhibition of DGKα in SAP-deficient cells can restore RICD, indicating that XLP1 patients will likely benefit from DGKα-targeted therapy.295,323,324

E3 ubiquitin ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases are enzymes that ubiquitinate different proteins and target them for proteasomal- or lysosomal-mediated degradation.325 Some of these ligases regulate T cell tolerance, and T cells can become autoreactive upon their deletion or mutation, leading to autoimmunity.326 TRAF6, as mentioned before, is one such E3 ubiquitin ligase that plays an important role in the activation of the NF-κβ signaling pathway.174,175 Itch is another ubiquitin ligase that not only targets PLCγ1 and PKCθ327,328 but also Jun, thereby causing diminished activation of AP-1.329 Itch thus regulates T cell anergy by degrading certain components of TCR signaling.330 Itch-deficient mouse models are therefore prone to autoimmune and pro-inflammatory phenotypes.1

A well-studied E3 ligase that marks various proteins for ubiquitin-mediated degradation is Casitas B cell lymphoma (CBLB). This enzyme, along with c-CBL, another member of the CBL family, negatively regulates TCR signaling.331 In activated T cells, the CD3ζ chain gets ubiquitinated by CBLB at its multiple lysine residues and induces degradation of surface TCRs.332–335 Some other targets for CBL-mediated ubiquitination and protein degradation include members of the proximal signaling complex, SRC- and Syk-family PTKs,336,337 the regulatory p85 subunit of PI3K,338 and the adaptor molecule VAV1.337 All these events result in the attenuation of TCR signaling. In another mode of action, T cell activation leads to dissociation of CBLB from Grb2, and it then binds to CRKL, an adaptor molecule required for T cell adhesion and migration. CRKL is in turn constitutively associated with C3G, a GEF for the small GTPases such as RAP1, RAP2, and R-RAS.339–345 The CRKL–C3G–RAP1 signaling pathway increases the affinity of β1-integrins to the extracellular matrix (ECM), regulating and mediating the adherence of the hematopoietic cells to ECM and stromal cells.346,347 Cell proliferation, cytoskeletal reorganization, and cell-to-cell contact are some of the most critical biological effects of the CRKL–C3G–Rap1 signaling pathway.341,346,348 The binding of CBL to CRKL results in the ubiquitination of CRKL, thus disrupting the CRKL–C3G–Rap1 signaling. On the other hand, an increase in CRKL–C3G–RAP1 signaling, along with clustering of the integrin, lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), was observed in response to TCR engagement upon knockdown of CBLB.349,350 CBLB thus serves as the negative regulator of CRKL–C3G–RAP1-mediated signaling events that promote T lymphocyte adhesion, migration, and homing.351 Both LCK and FYN seem to be involved in TCR downregulation, as pharmacological inhibition of LCK and FYN led to stabilization of the TCR complex.352

Adaptor proteins in cytoskeletal reorganization

Early events leading to T cell activation also involve cytoskeletal changes required for lymphocyte migration and mediating cell-to-cell adhesion.353 Interaction of T cells and APCs results in T cell activation, which involves supramolecular rearrangement of a number of receptors at the contact zone, thus forming a synapse. Initially, the integrin receptors of T cells and integrin receptor ligands of APCs are present in the center surrounded by a ring of MHC-peptide complexes. However, this pattern completely reverses within a few minutes, and MHC-peptide complexes form the central region known as the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC), surrounded by integrin receptors in the periphery, forming the peripheral supramolecular activation cluster (pSMAC).354–356 These structures are stable for a few hours where specific molecules can be detected. For example, PKCθ has been detected in cSMAC,354 whereas CD45 is initially excluded from cSMAC only to migrate back to it later.357 These molecular rearrangements are partly regulated by the cytoskeleton,354,355 where a ring of polymerized actin accumulates in T cell-APC conjugates or at the interface between T cells stimulated with anti-TCR antibodies.358 LAT and all its binding partners, such as PLCγ1, GADS, and GRB2, are essential for efficient actin polymerization, as the absence of LAT or mutation in binding sites of either of the components inhibits polymerization of actin.358 SLP-76 is one of the molecular adaptors present in a complex with LAT in activated T cells. It binds to several different adaptors involved in regulating the cytoskeleton. Two such adaptors, VAV and NCK, bind to the amino-terminal phosphotyrosine residues of SLP-76 (refs. 359,360) to promote cytoskeletal reorganization, whereas ADAP binds to the carboxyl-terminal phosphotyrosine residues of SLP-76 to promote integrin signaling361 (Fig. 1).

VAV

VAV structurally is a multidomain adaptor protein and functionally a GEF for the activation of Rac and Cdc42, members of the Rho/Rac family of small GTPases.362 Defects in IL-2 production and partial blocks in calcium mobilization were seen upon targeted disruption of VAV. VAV-deficient T cells also showed defects in cytoskeletal function,363,364 along with impaired SMAC formation.365 LAT-deficient T cells would thus fail in the recruitment of VAV via SLP-76, thereby decreasing the amount of activated Rac and Cdc42. This could result in inadequate activation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase, an enzyme responsible for generating PIP2, a substrate of PLCγ1.366 Moreover, there could be inadequate activation of Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) due to insufficient Rac activation.6

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein

WASP, as the name suggests, was initially identified as a defective protein from Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome patients.367 Decreased IL-2 production, calcium flux, and defective actin polymerization were seen in VAV−/− animals, and a similar phenotype was observed in T cells from WASP patients and murine cells from WAS−/− animals.368,369 This could be explained by the fact that WASP normally exists in an autoinhibited state in resting T cells, where the GTPase-binding domain interacts with the C-terminus that contains the Arp2/3 complex responsible for actin polymerization. The effectors of VAV, RAC, and CDC42, along with PIP2, upon activation, associate with WASP, thereby synergistically activating it and stimulating actin polymerization through the Arp2/3 complex.370,371 WASP is also associated with the NCK, which in turn binds SLP-76.372 Thus, SLP-76 might act as a scaffold by binding to both the NCK and VAV, thereby bringing WASP, RAC, and CDC42-GTP into close proximity so that they can interact with each other.373

NCK and T cell-specific adaptor protein (TSAd)

NCK is another adaptor protein known to regulate the actin cytoskeleton that constitutively interacts with VAV1.374 Both NCK and VAV1 further interact with SLP-76 upon TCR engagement, thereby forming a complex that associates with components of the TCR-CD3 complex, leading to reorganization of actin at the T cell-APC interface.360,373,375 A T cell-specific adaptor protein, TSAd, mediates the association of NCK with LCK and SLP-76 in T cells, thus controlling actin polymerization events in activated T cells. Both NCK and TSAd were found to co-localize in Jurkat cells, where NCK, via its SH2 and SH3 domains, interacts with pTyr280 and pTyr305 and the proline-rich region (PRR) of TSAd respectively. Further, increased polymerization of actin was observed in Jurkat cells expressing TSAd, and this was due to the presence of TSAd exon 7, which encodes interaction sites for both NCK and LCK.376

Moreover, many proteins tend to associate with NCK, as more than 60 binding partners have been identified.377,378 Thus, TSAd may influence the actin cytoskeleton by bringing LCK in the vicinity of different NCK binding partners.376 Moreover, CXCL-12-induced migration and cytoskeletal rearrangements in T cells are regulated via TSAd by promoting LCK-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of ITK.379 ITK not only binds to TSAd281,379 but also SLP-76,375 thereby forming a multiprotein complex of NCK, TSAd, LCK, SLP-76, and ITK that may interact with each other and several other molecules in a cooperative manner.376 NCK thus plays a vital role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, IS formation after TCR engagement, and cell proliferation and migration.377,380,381

Adhesion and degranulation promoting adaptor protein (ADAP)

Another component of the actin polymerization machinery in T cells is the SLP-76-associated phosphoprotein of 130 kDa (SLAP-130)/FYN-binding protein (FYB)/adhesion and degranulation promoting adaptor protein (ADAP).6 It is a multidomain adaptor protein that, upon TCR engagement, gets phosphorylated by SRC family kinases, such as FYN, enabling its binding to the SH2 domains of SLP-76 and FYN.382,383 Peripheral T cells deficient in ADAP demonstrated defects in cell proliferation, cytokine production, and clustering of the integrin LFA-1 upon TCR stimulation,270,271 whereas TCR-driven IL-2 transcription was increased upon co-transfection of ADAP with SLP-76 and FYN.383,384 Integrin clustering with the help of ADAP facilitates T cell migration in response to stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha (SDF1α)385 and enhances T cell-APC conjugate formation.386 ADAP thus couples TCR-mediated actin cytoskeletal changes to integrin activation.13 ADAP associates with proteins of the Ena (enabled)/VASP (vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) family, important for the regulation of actin dynamics and T cell polarization, thereby regulating cell adhesion mediated by integrins.387 ADAP also interacts with a multiprotein complex composed of WASP, Arp2/3, VAV, NCK, and SLP-76. TCR-mediated actin rearrangement was inhibited when the binding between the WASP and Arp2/3 complex or ADAP and Ena/VASP proteins was hindered, suggesting that TCR signaling is linked to cytoskeletal remodeling by these interactions.388

SRC kinase-associated phosphoprotein of 55 kDa (SKAP-55)

SKAP-55 or Scap1 is a T cell-specific adaptor protein that is constitutively associated with ADAP.389,390 It enhances cellular adhesion by not only promoting the clustering of LFA-1 but also enhancing its binding to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and fibronectin. SKAP-55 also increases T cell/APC conjugate formation, thereby inducing its translocation to the lipid rafts.386 This brings it into close proximity with the SRC kinase FYN that phosphorylates SKAP-55.391 Both ADAP and SKAP-55 might control the formation of SMACs since they enhance LFA-1-mediated adhesion during T cell/APC interactions, which are important for SMAC formation.13

Mammalian CT10 (chicken tumor virus number 10) regulator of kinase (CRK)

The CRK adaptor proteins are ubiquitously expressed and regulate proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration, and apoptosis of immune cells by integrating signals from various effector molecules, such as ECM, growth factors, pathogens, and apoptotic cells.392–396 There are three members belonging to the family of CRK adaptor proteins, CRKI, CRKII, and CRK-like (CRKL), that mediate various protein interactions through their SH2 and SH3 domains. Transient interactions with STAT5, ZAP-70, CBL, and CASL (CRK-associated substrate lymphocyte type) are mediated by the CRK SH2 domains, thus activating the lymphocytes. Cytokines secreted upon TCR activation can induce STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation, possibly through Janus kinase 3 (JAK3), which was shown to be required for T cell proliferation.397 Furthermore, the STAT5 function is required for amino acid biosynthesis.398 Cell adhesion of lymphocytes, their extravasation, and recruitment to the sites of inflammation are mediated by the constitutive association of CRK with C3G via their SH3 domains. A detailed function of CRKL-C3G is mentioned in the ubiquitin ligase section of this paper, while the reader is also referred to the comprehensive review on the role of CRK adaptor proteins in T cell adhesion and migration.399

TCR signaling dysregulation in diseases

Dysregulation of TCR signaling can lead to the generation of various diseases, given its importance in executing different functions of T cell biology. Thus, defects in TCR signaling can lead to immune deficiency. On the other hand, its hyperactivation can lead to autoimmune diseases. TCR signal transduction is thus tightly regulated via multiple mechanisms by various enzymes and non-enzymatic proteins that serve as scaffolds for efficient signal transmission.183 Mutations in any of these mediators can contribute to the dysregulation of TCR signaling, leading to various disorders.

Both immune deficiency and autoimmunity have been observed when tyrosine phosphatase CD45 is misexpressed. SCID which is characterized by the absence or defective function of T cells, displays deficiency of CD45 expression,400,401 whereas multiple sclerosis (MS) is an end result of certain CD45 polymorphisms.402 SCID was also generated due to mutations in genes coding for CD3 δ, ε, and ζ chains.403 Both mice and humans showed immunodeficiency due to defective expression of LCK.404,405 Furthermore, a rare form of SCID was observed in humans with functionally impaired CD4+ T cells and the absence of CD8+ T cells due to deficiency or mutation of ZAP-70.406,407 In contrast, the development of T cells at the CD4+ CD8+ double-positive stage in mice was blocked due to deficiency of ZAP-70, thereby having a complete absence of single positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.1 On the other hand, autoimmune disorders can be caused by an abnormal thymic selection of T cells or their uncontrolled proliferation due to dysregulated TCR signaling. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and SLE have been found to be associated with reduced expression of CD3ζ.408,409 Similar to human RA, autoimmune arthritis has been observed in mice having spontaneous mutations in the SH3 domain of ZAP-70.410 Non-T cell activation linker (NTAL) is a transmembrane adaptor molecule that enhances methylprednisolone and TCR-induced apoptosis in T-ALL through increased ERK phosphorylation.411 NTAL thus serves as a tumor suppressor in T-ALL, where its high mRNA expression correlates with a good response to prednisone and vice versa.412 Accordingly, NTAL−/− mice displayed activated T cells characteristic of an autoimmune syndrome.411

Peripheral T cell lymphomas (PTCL) and T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias or lymphomas (T-ALL) both constitute different groups of T cell malignancies; PTCL arises from post-thymic mature T cells whereas T-ALL arises from thymic immature T cells blocked at various stages of development.413 Multiple molecular aberrations have been described in genes involved in TCR signaling in PTCL,413 with 84% of Sezary syndrome samples414 and 90% of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma samples415 showing mutations in TCR signaling components. Upregulation of the LAT adaptor along with frequent activating mutations (gain-of-function alterations) in the adaptor CARD11 and PLCγ1 have been observed in most cases of Sezary syndrome cutaneous T cell lymphoma,414 contributing to cell survival and proliferation and disease progression. Thus, the TCR signaling in this context is oncogenic. In contrast, translocations involving TCR genes have been identified in T-ALL416 with no recurrent mutations in any of the TCR signaling components.413 In a landmark study, Trinquand et al. in 2016417 identified that TCR engagement with an MHC-restricted TCR-specific antigen or via CD3 stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 made TCR-positive T-ALL cells undergo apoptosis in a similar transcriptional program as the thymic negative selection. However, leukemia recurrence was observed in TCR-positive T-ALL xenografts due to the presence and selection of TCR-negative subclones as a mechanism of tumor relapse from OKT3-mediated therapy. Nevertheless, it is quite encouraging to see that mature T-ALL cells can be induced to undergo apoptosis by TCR activation, using the gene signature for negative selection that is reminiscent in these cells. Subsequently, when assessing the potential of novel anticancer therapies, it is necessary to also assess the importance of cell and disease, as TCR signaling supports oncogenesis in PTCL whereas it appears to have an anti-oncogenic effect in T-ALL.413

Applications of TCR-based immunotherapy

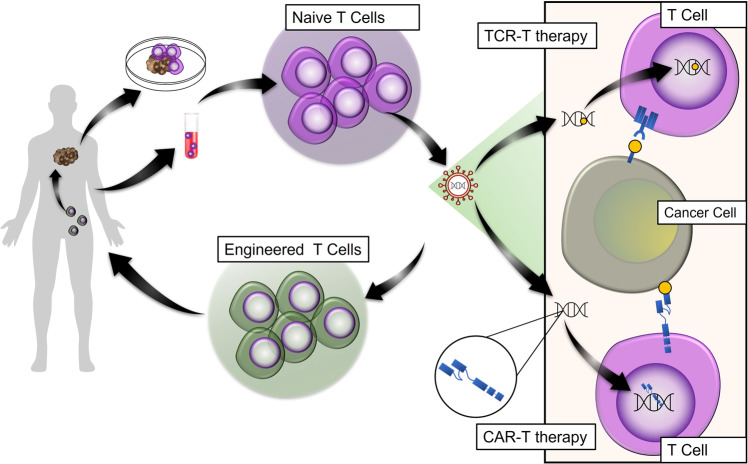

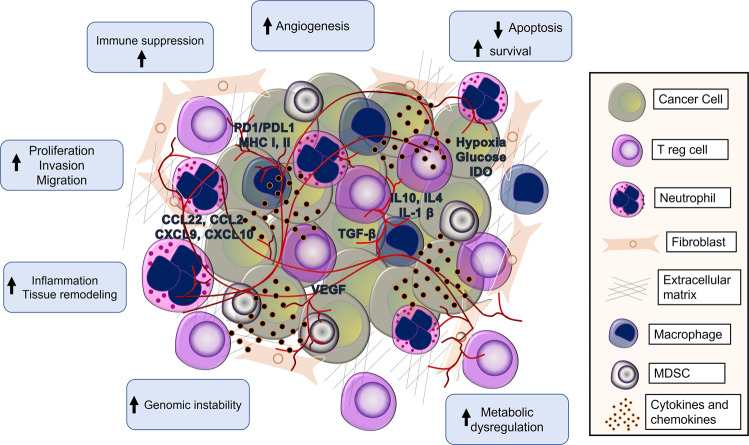

The emergence of T cell-based immunotherapy has revolutionized the understanding of the role of T cells in mitigating a wide variety of diseases, including viral, autoimmune, and malignant diseases. TCR engineering has provided a compelling approach to fight cancer, disrupting the immuno-oncology research field and introducing a new class of impressive cancer immuno-therapeutic strategies, including adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), checkpoint blockade, tumor microenvironment (TME) regulation, and cancer therapeutic vaccines.

Fig. 3. Positive regulation of T cell signaling.

The figure depicts the activation of various enzymes and adaptor molecules upon engagement of TCR with the MHC antigenic peptide complex. The phosphorylation events carried out are depicted as small, blue-colored circles. Black lines with arrows indicate activation.

Adoptive T cell transfer therapy

Experimental research in T cells adoptive transfer has revealed the superior capabilities of T cells to identify tumor antigens and to harness the immune system, contributing to anti-tumor activity.418 This type of therapy was first demonstrated clinically by Southam et al.419 in 1966 when patients with unresectable cancer displayed tumor regression upon co-transplantation with patient-derived leukocytes and autologous tumor cells. Although this strategy has been successfully applied, adoptive T cell transfer has not been generalized widely due to the fact that the number of infiltrated T cells was insufficient to exert a full potential of the anti-tumor activity or to boost the body’s immune response against cancer. In addition, the validated immune response in patients receiving this type of therapy was found to be cancer-type and patient-dependent.420,421 Therefore, the engineering of T cells has provided an effective alternative to activate and expand T cells ex vivo with defined specificity against tumor antigens. In this context, TCR-engineered lymphocytes have garnered considerable attention over the past decade, offering significant curative outcomes in patients with cancer. Because tumor cells downregulate MHC molecules, also known as HLA, this posed a challenge for proper T cell response directed against tumor antigen presentation resulting in immune tolerance.422 However, the development of synthetic chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) has overcome this challenge by redirecting T cell specificity to recognize and lyse tumor antigens on the surface of the malignant cell independently of MHC molecules.423

Fig. 4. Negative regulation of T cell signaling.

The figure depicts various adaptors and enzymes, like kinases and phosphatases, involved in negatively regulating TCR signaling. The phosphorylation events carried out are depicted as small, blue-colored circles. Black lines with arrows indicate activation. Dotted black lines with arrows indicate dephosphorylation events.

To date, different types of ACTs have been developed, including TCR engineered T cell therapy (TCR-T), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and CAR T therapy.424–427 These strategies allow the fast entry of T cell-receptor-based immunotherapies to clinical trials with encouraging clinical outcomes.

TILs therapy