Abstract

Background & Aims:

This study aimed to systematically evaluate a classification scheme of secondary peristalsis using functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) Panometry through comparison with primary peristalsis on high-resolution manometry (HRM).

Methods:

706 adult patients that completed FLIP and HRM for primary esophageal motility evaluation and 35 asymptomatic volunteers (“controls”) were included. Secondary peristalsis, i.e. contractile responses (CR), was classified on FLIP Panometry by presence and pattern of contractility as normal (NCR), borderline (BCR), impaired/disordered (IDCR), absent (ACR), or spastic-reactive (SRCR). Primary peristalsis on HRM was assessed according to the Chicago Classification.

Results:

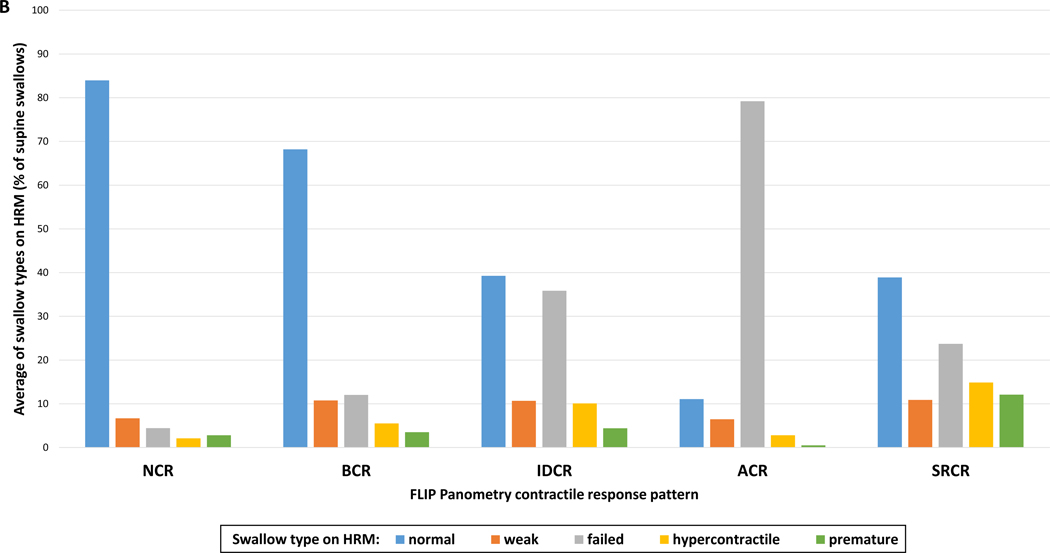

All 35 of the controls had antegrade contractions on FLIP Panometry with either NCR (89%) or BCR (11%). The average percentages of normal swallows on HRM varied across contractile response patterns from 84% in NCR, 68% in BCR, 39% in IDCR, to 11% in ACR, as did the percentage of failed swallows on HRM: 4% in NCR, 12% in BCR, 36% in IDCR, and 79% in ACR. SRCR on FLIP Panometry was observed in 18/57 (32%) patients with type III achalasia, 4/15 (27%) with distal esophageal spasm, and 7/15 (47%) with hypercontractile esophagus on HRM.

Conclusions:

The FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns reflect a pathophysiologic transition from normal to abnormal esophageal peristaltic function with shared features with primary peristaltic function/dysfunction on HRM. Thus, these patterns of the contractile response to distension can facilitate evaluation of esophageal motility using FLIP Panometry.

Introduction

The functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) utilizes impedance planimetry technology to assess lumen dimensions along the length of the esophagus and esophageal distensibility (i.e. the relationship of dimension with distensive pressure) during controlled volumetric distension. We developed a technique to assess esophageal motility using FLIP and a volume distention protocol, FLIP Panometry, by displaying the esophageal diameter changes along a space-time continuum with associated pressure.1 Utilizing FLIP Panometry, the contractile response to distension, i.e. secondary peristalsis can be assessed, in addition to esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening and distensibility.1, 2

Esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) is generally considered the standard method to assess for esophageal motility disorders.3, 4 With HRM and esophageal pressure topography, primary peristalsis is assessed with a standardized swallow protocol during which the vigor of peristalsis can be quantified using the HRM-metric of distal contractile integral (DCI) and swallow types can be classified as ineffective (failed, weak, or fragmented), premature, hypercontractile, or normal.4, 5 The proportions of each swallow type is then incorporated into the classification scheme to generate an esophageal motility diagnosis.4, 5

We previously demonstrated that a FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern associated with repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) during sustained volumetric distention was the physiomarker of normal esophageal body function and a pattern that was not observed among patients with achalasia (i.e. absent primary peristalsis).6–8 Our proposed classification scheme to assess the contractile response to distension using FLIP Panometry was evaluated among patients with normal esophageal motility on HRM and demonstrated that the majority of patients (77% of 164 patients) with normal primary peristalsis on HRM also had antegrade contractions (secondary peristalsis) observed on FLIP Panometry. The 23% rate of abnormal contractile responses to distension in patients with normal primary peristalsis was consistent with previous studies evaluating secondary peristalsis using manometry.9, 10

Therefore, the aim of this study was to further evaluate the classification of contraction response patterns on FLIP Panometry by comparison with primary peristalsis on HRM among a large cohort of symptomatic patients and asymptomatic controls.

Methods

Subjects

Adult patients (age 18–89) presenting to the Esophageal Center of Northwestern for evaluation of esophageal symptoms between November 2012 and December 2019 who completed FLIP during upper endoscopy and HRM were prospectively evaluated and data maintained in an esophageal motility registry. Consecutive patients that completed FLIP during sedated endoscopy and a corresponding HRM (i.e. no interval treatment and within 12 months) for evaluation for primary esophageal motility disorders were included. Patients with technically limited FLIP or HRM studies were excluded. Patients with previous foregut surgery (including previous pneumatic dilation) or esophageal mechanical obstructions including esophageal stricture, eosinophilic esophagitis, severe reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles-classification C or D), hiatal hernia > 3cm were excluded as these are causes attributed to secondary esophageal motor abnormalities.

Additionally, a cohort of healthy, asymptomatic (i.e. free of esophageal symptoms including dysphagia, heartburn, and chest pain), adult volunteers (“controls”) were included. Potential control subjects were excluded for previous diagnosis of esophageal disorders (and thus the same exclusion criteria applied to patients were also applied for controls). Additional exclusion criteria included previous diagnosis of autoimmune, or eating disorders, use of antacids or proton pump inhibitors, body mass index >30 kg/m2, or a history of tobacco use or alcohol abuse. Informed consent was obtained for subject participation; control subjects were paid for their participation. The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. There is overlap of both the patient and control cohorts with previous publications.2, 6, 8, 11, 12

FLIP Study Protocol and Analysis

The FLIP study using 16-cm FLIP (EndoFLIP® EF-322N; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, MN) was performed during sedated endoscopy as previously described.2, 6 Endoscopy performed in the left-lateral decubitus position was generally performed using conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl; all of the controls were studied using conscious sedation. Other medications, e.g. propofol, were also used with monitored anesthesia care at the discretion of the performing endoscopist in 147/706 (21%) cases. Although these medications used for endoscopic sedation can alter esophageal motility, the patterns of motility during the FLIP protocol are reproducible and have been shown to predict motility patterns during standard manometry performed without these medications.2, 6, 13, 14 With the endoscope withdrawn and after calibration to atmospheric pressure, the FLIP was placed transorally and positioned within the esophagus with 1–3 impedance sensors beyond the EGJ with this positioning maintained throughout the FLIP study. Stepwise 10-ml FLIP distensions beginning with 40 ml and increasing to target volume of 60 or 70 ml were then performed; each stepwise distension volume was maintained for 30–60 seconds.

FLIP data were exported using a customized program (available open source at http://www.wklytics.com/nmgi) to generate FLIP Panometry plots for analysis.8, 11 The analysis of the FLIP Panometry plots was then performed by raters that used the plots and analysis software. The analysis included the 50–70ml FLIP fill volumes as lower fill volumes were observed to be susceptible to movement artifact. FLIP Panometry studies were initially collectively reviewed by 4 physicians (AJB, END, JEP, DAC) and the FLIP pattern was determined by consensus agreement among the reviewers. The FLIP studies were then sent to three external reviewers (RY, AK, CPG) for review and assessment of agreement with the FLIP contractility pattern. The internal and external reviews were blinded to clinical details, including HRM results, for FLIP interpretation. The external raters were provided a brief tutorial slide set that included the contractile pattern criteria (Table 1). For studies in which there was disagreement in classification, the majority classification was applied for analysis.

Table 1.

Panometry Contractile Response Patterns.

| Panometry Contractile Response Patterns | Definition |

|---|---|

|

Normal Contractile Response

NCR |

RAC-Rule of 6s (Ro6s)

|

|

Borderline Contractile Response

BCR |

|

|

Impaired/Disordered Contractile Response

IDCR |

|

|

Absent Contractile Response

ACR |

|

|

Spastic-Reactive Contractile Response

SRCR |

|

The contractile response to distension was based on evaluation of the FLIP study protocol including from the 50ml to 70ml fill volume. AC-Antegrade contractions. RC-retrograde contractions. RACs - Repetitive ACs. RRCs – Repetitive RCs. SOCs- sustained occluding contractions. sLESC – sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction.

Analysis of the contractile response to distension with FLIP Panometry

The analysis of the FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern was based on the totality of the FLIP study that included the 50ml, 60ml, and 70ml fill volumes. Esophageal body contractility was identified by a transient decrease in the luminal diameter in ≥3 adjacent impedance planimetry channels (i.e. ≥3 cm axial length). The direction of contractions (antegrade or retrograde) was categorized based on a tangent line placed at the onset of contraction. The contractile response to distension were further categorized as repetitive if contractions of similar directionality occurred consecutively at a consistent time interval and then by contraction direction (antegrade or retrograde). The rate of repetitive contractions was derived by dividing the number of repetitive contractions by duration (time) of repetitive contraction pattern and then normalized to reflect the number of contractions per minute. The repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) pattern was specifically identified using the RAC Rule-of-6s (Ro6s) as a) duration of ≥6 antegrade contractions that were b) ≥6-cm in axial length, and c) occurred at a regular rate of 6 (+/−3) antegrade contractions per minute; Figure 1.7, 8 A repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs) pattern was defined when retrograde contractions of ≥6 axial length occurred at a rate of >9 contractions per minute. Studies were also reviewed for the presence of sustained LES contractions (sLESC) and sustained occluding contractions (SOCs); Figure 2. sLESC was considered present when there was a transient reduction in diameter attributed to the LES (i.e. not associated with respiration and crural contraction) associated with an increase in FLIP pressure.12 The categorization of sLESC also required that the response was independent of an antegrade contraction in the esophageal body and lasted longer than 5 seconds. Sustained occluding contraction (SOC) was defined as a non-propagating, occluding contraction of the esophageal body in continuity with the EGJ that persisted for >10 seconds and was associated with a pressure increase >35 mmHg.7, 15

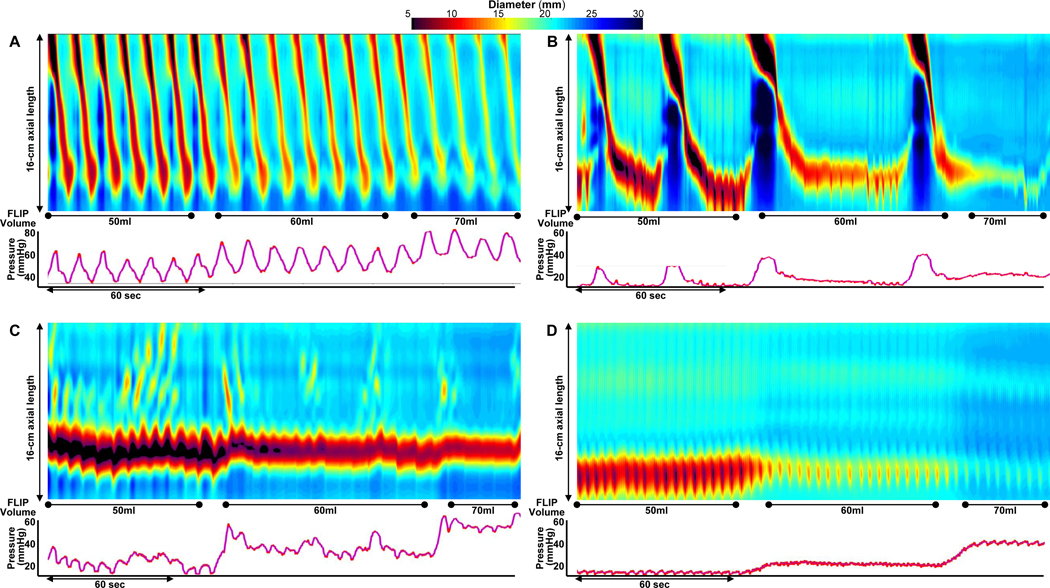

Figure 1. FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns.

FLIP Panometry output from four patients (A-D) is displayed as length (16-cm) x time x color-coded diameter FLIP topography (top panels) with corresponding intraballoon pressure (bottom panel); the corresponding high-resolution manometry (HRM) findings are described, but not displayed. A) A normal contractile response on Panometry with repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) meeting the RAC Rule-of-6s; this patient had normal esophageal motility on HRM. In B, distinct antegrade contractions are observed, but not meeting the RAC Rule-of-6s thus a borderline/diminished contractile response; this patient had ineffective esophageal motility on HRM. In C, contractility is observed, but without distinct antegrade contractions, thus assigned an impaired/disordered contractile response; this patient had type II achalasia on HRM. D) An absent contractile response on FLIP Panometry; this patient, who had systemic sclerosis, had an HRM with absent contractility. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

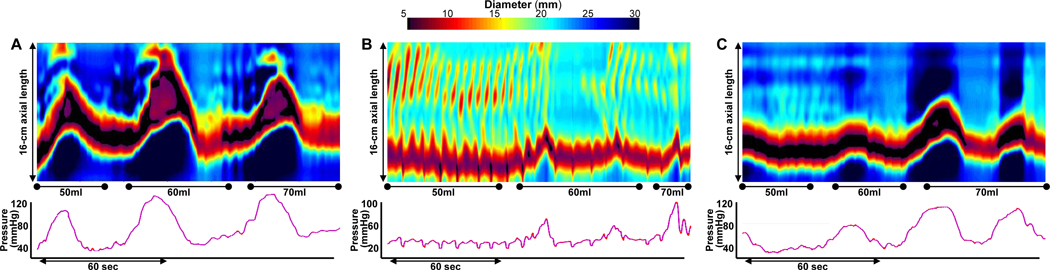

Figure 2. Spastic-reactive contractile response.

FLIP Panometry from 3 patients (A-C) classified as a spastic reactive contractile response. A spastic-reactive contractile response was assigned with presence of A) sustained occluding contractions (SOCs), B) repetitive retrograde contractions, C) or sustained lower esophageal sphincter contractions (SLESC). Contractility of the esophageal body was present in A and B (but without distinct antegrade contractions) and was absent in C. High-resolution manometry (HRM) classifications were of EGJ outflow obstruction with hypercontractility in A, type III achalasia in B, and type II achalasia in C. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

The contractile response to distension was then classified to assess the spectrum of secondary peristaltic response, i.e. transitioning from normal to abnormal (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1). The contractile response patterns were devised based on initial observations for categorization of contractile response patterns among HRM motility classifications, as well as anticipated ease of interpretation with qualitative pattern recognition and categorization using the presence or absence of antegrade contractions as an important discriminator.2, 6–8, 15 Normal contractile response (NCR; defined by RAC Ro6s) and borderline contractile response (BCR) both included distinct antegrade contractions, while antegrade contractions were not present in the patterns of impaired/disordered contractile response (IDCR) and absent contractile response (ACR). Spastic-reactive contractile response (SRCR) was classified based on the presence of sLESC, SOC, or repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs) and thus may also have scattered antegrade contractions present. SRCR studies were additionally assessed in a more detailed manner to describe contractile activity within the esophageal body and thus classified secondarily to SCRC as either absent, with contractility of the esophageal body without distinct antegrade contractions, or with antegrade contractions.

Analysis of EGJ opening on FLIP Panometry

The FLIP studies were also analyzed by raters using the customized analysis program for EGJ opening utilizing the EGJ- distensibility index (DI) at the 60ml FLIP fill volume and the maximum EGJ diameter that was achieved during the 60ml or 70ml fill volume. Measurements related to EGJ opening were taken at areas at the EGJ that were not affected by dry catheter artifact (i.e. artifact that impacts diameter measurement when occlusion of the FLIP balloon disrupts the electrical current utilized for the impedance planimetry technology).12 Then, the first 5 seconds after achieving the 60ml fill volume were omitted from analysis to avoid incorporation of active-filling effects. The EGJ-DI was then measured during the 60ml FLIP fill volume dependent on the FLIP contractile response pattern. If antegrade contractions were present, three measures of EGJ-DI (EGJ-cross sectional area divided by pressure) were obtained at the peak EGJ diameter that occurred during the pressure up-slope or pressure peak associated with antegrade contractions. If antegrade contractions did not occur during the 60ml fill volume, three measures of EGJ-DI were obtained during expiration or between EGJ contractions. The median of the three EGJ-DI values was then applied for analysis. The EGJ-DI was not calculated if the applied FLIP pressure was <15mmHg; in these cases, the max EGJ-diameter was applied independently for analysis. Normal EGJ opening was defined when there was both an EGJ-DI ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg and a maximum EGJ diameter ≥16mm.12 Abnormal EGJ opening was defined as EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg or maximum EGJ-diameter <16mm.

HRM protocol and analysis

After a minimum 6-hour fast, HRM studies were completed using a 4.2-mm outer diameter solid-state assembly with 36 circumferential pressure sensors at 1-cm intervals (Medtronic Inc, Shoreview, MN). The HRM assembly was placed transnasally and positioned to record from the hypopharynx to the stomach with approximately three intragastric pressure sensors. After a 2-minute baseline recording, the HRM protocol was performed with ten, 5-ml liquid swallows in a supine position and with five 5-ml liquid swallows in an upright, seated position.5

Manometry studies were analyzed according to the Chicago Classification v3.0, as all of these patients were evaluated prior to or during the consensus development process for Chicago Classification version 4.0.4, 5 An exception was in regard to classification of ineffective esophageal motility (IEM), which was classified in this study if >70% of supine swallows were ineffective (failed, weak, or fragmented) or >50% of supine swallows were failed; Table S1.5 A median integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) of >15 mmHg was applied as the upper limit of normal for supine swallows. Classifications of peristalsis were also applied using the percentages of swallow types for patients with a Chicago Classification v3.0 of EGJ outflow obstruction; Table S1.4, 5 Failed swallows were assigned a DCI value of 0 mmHg•s•cm and the mean DCI was calculated across the ten supine test swallows.

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported as mean (standard deviation; SD), or median (interquartile range; IQR) depending on data distribution. Groups were compared using Chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA/t-tests or Kruskal-Wallis/Mann-Whitney U for continuous variables, depending on data distribution. Statistical significance was considered at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. Post-hoc comparison testing, as appropriate, was completed using a Bonferroni correction.

Results

Subjects

706 patients, mean (SD) age 54 (17) years, 58% female and 35 controls, mean (SD) age 30 (6) years, 71% female were included. Among patients, the most common HRM diagnoses were achalasia (subtypes I, II, or III), which was observed in 245 (35%) patients, and normal esophageal motility, which was observed in 178 (25%) patients (Table 2). The FLIP and HRM were performed on the same day in 510 patients; in the remainder, the median (IQR) interval between tests was 1.7 (0.7–3.7) months. In the controls, 32/35 (91%) controls had normal peristalsis (4 of whom also had an IRP > 15mmHg) and 3 (9%) had IEM on HRM.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics by FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns.

| Panometry Contractile response pattern | Controls | All patients | Normal | Borderline | Impaired/ disordered | Absent | Spastic-reactive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| n | 35 | 706 | 108 | 132 | 190 | 198 | 78 |

|

| |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years * | 30 (6) | 54 (17) | 42 (15) | 52 (14) | 57 (16) | 54 (17) | 64 (14) |

|

| |||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| |||||||

| Gender, n(%) female * | 25 (71) | 406 (58) | 74 (69) | 94 (71) | 101 (53) | 94 (48) | 43 (55) |

|

| |||||||

| Indication * | |||||||

| Dysphagia | 0 | 639 (91) | 88 (82) | 108 (82) | 181 (95) | 188 (95) | 74 (95) |

| Reflux symptoms | 0 | 41 (6) | 16 (15) | 12 (9) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Chest pain | 0 | 16 (2) | 3 (2) | 9 (7) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 35 (100) | 10 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (3) |

|

| |||||||

| Endoscopy findings | |||||||

| Erosive esophagitis; | |||||||

| LA-A / LA-B | 0 / 0 | 23 (3) / 19 (3) | 4 (4) / 5 (5) | 8 (6) / 5 (4) | 6 (3) / 4 (2) | 4 (2) / 4 (2) | 1 (1) / 1 (1) |

| Non-obstructing ring | 0 | 15 (2) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Diverticulum 4 | 0 | 22 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | 7 (9) |

|

| |||||||

| HRM-Chicago Classification 2 * | |||||||

| Normal motility | 28 (80) | 178 (25 | 72 (67) | 61 (46) | 23 (12) | 7 (4) | 15 (19) |

| IEM 3 | 3 (9) | 41 (6) | 5 (5) | 11 (8) | 13 (7) | 9 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Absent contractility | 0 | 30 (4) | 0 | 4 (3) | 7 (4) | 18 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Hypercontractile esophagus | 0 | 15 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 7 (9) |

| Distal esophageal spasm | 0 | 15 (2) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 4(2) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) |

| Type I achalasia | 0 | 54 (8) | 0 | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 47 (24) | 1 (1) |

| Type II achalasia | 0 | 134 (19) | 0 | 1 (1) | 39 (21) | 82 (41) | 12 (15) |

| Type III achalasia | 0 | 57 (8) | 0 | 5 (4) | 27 (14) | 7 (4) | 18 (23) |

| EGJ outflow obstruction | 4 (11) | 182 (26) | 24 (22) | 44 (33) | 71 (31) | 26 (13) | 17 (22) |

|

| |||||||

| HRM-EGJOO, contractile pattern 2 | |||||||

| Normal | 4 (100) | 125 (69) | 22 (92) | 33 (75) | 45 (63) | 16 (62) | 9 (53) |

| IEM 3 | 0 | 22 (12) | 0 | 2 (5) | 11 (16) | 6 (23) | 3 (18) |

| Hypercontractile | 0 | 14 (8) | 0 | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 3 (12) | 1 (6) |

| Spasm | 0 | 21 (12) | 2 (8) | 4 (9) | 10 (14) | 1 (4) | 2 (24) |

|

| |||||||

| HRM-EGJ-morphology * | |||||||

| Type I (no hiatal hernia) | 31 (89) | 562 (80) | 83 (77) | 99 (75) | 149 (78) | 176 (89) | 55 (70) |

| Type II-III (hiatal hernia) | 4 (11) | 143 (20) | 24 (22) | 33 (25) | 41 (22) | 22 (11) | 23 (30) |

|

| |||||||

| EGJ-DI, mm2/mmHg, median (IQR) * | 5.8 (5.0–6.4) | 1.9 (0.9–4.4) | 5.2 (3.9–6.6) | 3.4 (2.0–5.5) | 1.2 (0.7–2.4) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 1.2 (0.7–2.4) |

|

| |||||||

| Maximum EGJ diameter, mm, median (IQR) * | 20.4 (19.5–20.8) | 13.6 (9.0–18.6) | 19.9 (18.1–21.2) | 18.5 (15.6–20.5) | 11.0 (8.6–15.4) | 9.2 (7.5–11.9) | 11.5 (9.6–14.0) |

P<0.001 on comparison between 5 groups.

P=0.023 on comparison between 5 groups.

High-resolution manometry (HRM) classification, and the peristalsis/contractile classification among patients with a HRM classification of EGJ outflow obstruction, were assigned based on 10 supine swallows.

Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) was defined by >70% ineffective swallow or ≥50% failed swallows.

Contractile response patterns among normal controls

Antegrade contractions were observed on FLIP Panometry in all 35 controls; 31 (89%) had NCR and 4 (11%) had BCR. In the 4 controls with BCR on FLIP Panometry, the median (IQR) mean DCI on HRM was 831 (284–3147) mmHg•s•cm versus 1638 (1128–3072) mmHg•s•cm in the controls with NCR on FLIP; P=0.233. One of 4 (25%) controls with BCR on FLIP had IEM classified on HRM compared with 3/32 (9%) of the controls with NCR on FLIP; P=0.313. None of the controls had sLESC, SOCs, nor RRCs.

FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns in patients

Among the 706 patients, FLIP Panometry contractile patterns were NCR in 108 (15%), BCR in 132 (19%), IDCR in 190 (27%), ACR in 198 (28%), and SRCR in 78 (11%). Agreement of the three external reviewers with the initial classification of contractile response pattern was observed in 719/741 (97%) cases, 709/741(96%) cases, and 724/741 (98%) cases, respectively, thus the average percent agreement was 97%.

Clinical and HRM characteristics among the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns are displayed in Table 2. There was a difference in age between the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns such that patients with NCR were the youngest and SCRC were the oldest. There were also differences between the contractile response patterns related to gender (greater proportion of female in contractile response patterns in NCR and BCR), indication for evaluation (greater proportion of evaluations for reflux symptoms in NCR and BCR), and presence of hiatal hernia (most frequent in SCRC and least frequent in ACR); Table 2.

Evaluation of the relationships of the FLIP Panometry contractile patterns with general classification of peristalsis or contractility on HRM demonstrated that of the 218 patients with 100% failed peristalsis on HRM (i.e. type I and II achalasia and absent contractility), 91% had either ACR (147; 67%) or IDCR (51; 23%) on FLIP Panometry; none (0%) of these patients had a normal contractile response and only 6 (3%) had BCR (Table 2). Among the 198 patients with ACR on FLIP Panometry, only 7 (4%) had normal motility on HRM. Among the 303 patients with normal primary peristalsis on HRM, (thus including patients with an HRM classification of EGJOO with normal peristalsis, as well as those with normal esophageal motiltity) 62% (n=188) had antegrade contractions on FLIP Panometry with either NCR or BCR. When stratifying by peristalsis pattern on HRM, differences were not observed between FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns related to sedation strategy (Table S2).

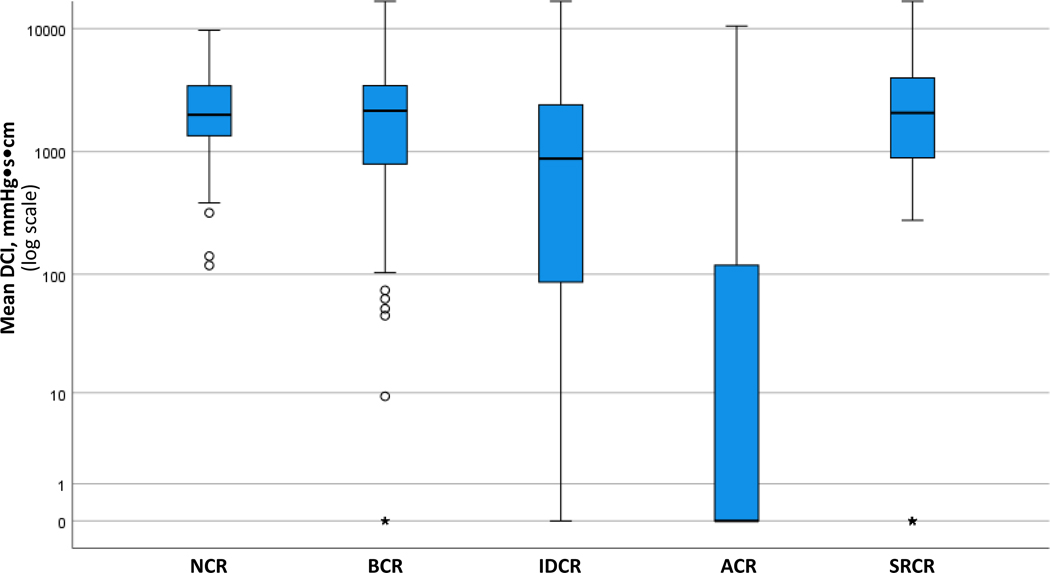

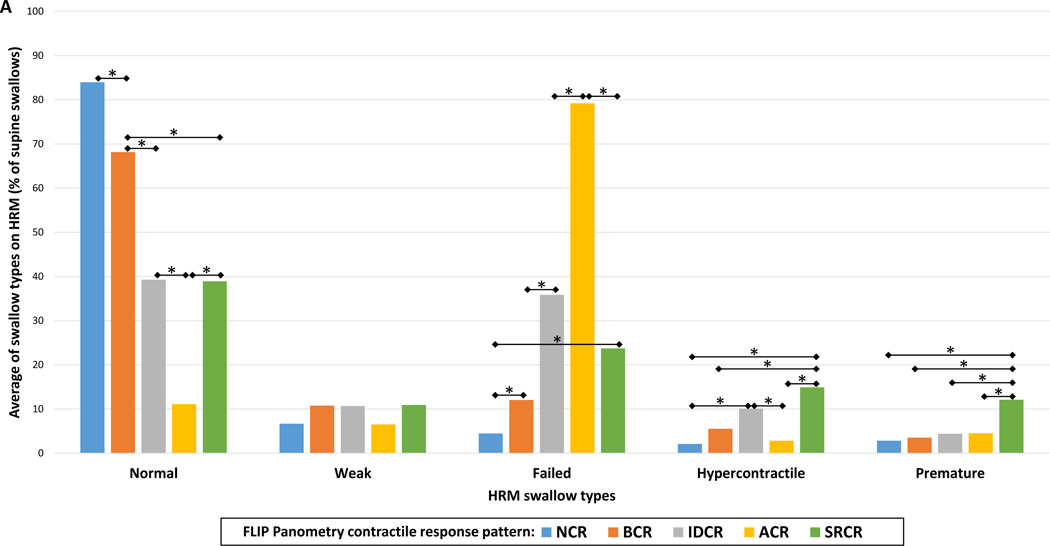

Mean DCI values differed between the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns and were the lowest in patients with ACR on FLIP Panometry; Figure 3. Proportions of HRM swallow types (i.e. average percentages of supine test swallows) on HRM also differed between FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns: P-values <0.001 for normal, failed, hypercontractile, and premature swallow types; P=0.099 for weak (Figure 4). NCR had the greatest average percentage of normal swallows and ACR the lowest. ACR had the greatest average percentage of failed swallows and NCR the lowest. The highest percentage of hypercontractile and premature swallows were observed in SRCR, though IDCR also had a greater percentage of hypercontractile swallows than NCR and ACR.

Figure 3. Peristaltic vigor on high-resolution manometry (HRM) differed by FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern.

The mean DCI from the ten 5ml liquid supine HRM test swallows are plotted by FLIP Panometry contractile pattern: note the logarithmic scale. The mean DCI was lower in absent contractile response (ACR) than impaired/disordered contractile response (IDCR), p<0.001, and lower in IDCR than in borderline contractile response (BCR), normal contractile response (NCR), and spastic-reactive contractile response (SRCR); P-values <0.001. Mean DCI values were similar between NCR, BCR, and SRCR (P-values 0.382 – 0.829). The ○ and * on the box-and-whisker plots reflect outlier values. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Figure 4. Swallow types on high-resolution manometry (HRM) differed by FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern.

The bars (in A and B) represent the group average percentage of swallow types during the HRM supine test swallows for each FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern: normal contractile response (NCR); borderline contractile response (BCR); impaired/disordered contractile response (IDCR); absent contractile response (ACR); spastic-reactive contractile response (SRCR). In A, the data is organized by HRM swallow type, where * indicates a significant difference when applying a Bonferroni correction for P-value <0.007. In B, the same data is organized by FLIP Panometry contractile response. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Association of FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern with EGJ opening

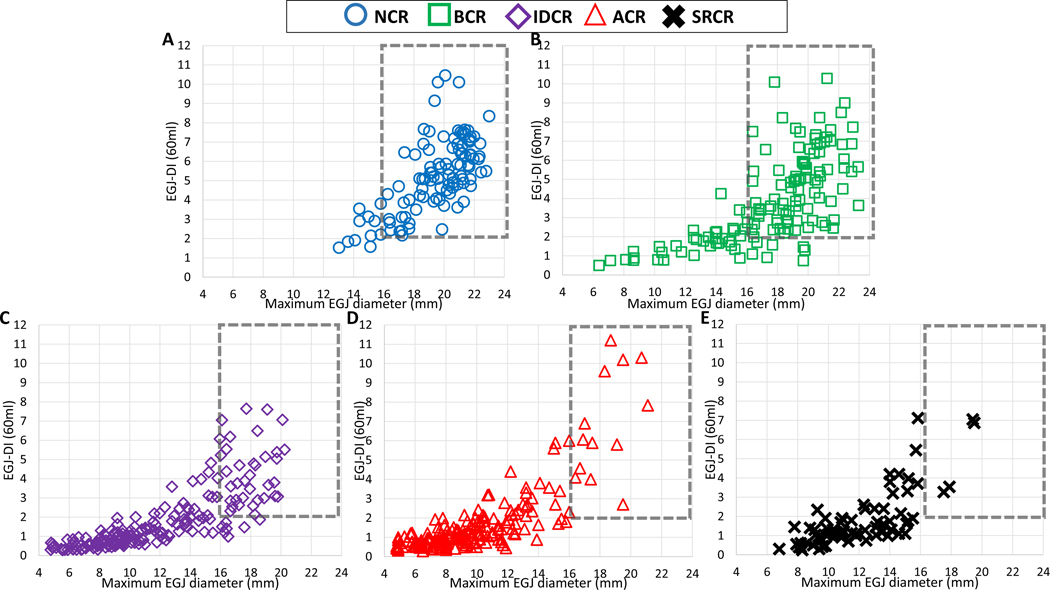

Both the EGJ-DI and maximum EGJ diameter differed between the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns (P-values <0.001), such that they were greater in NCR than BCR (P-values <0.001) and greater in BCR than IDCR (P-values <0.001) and also greater in BCR than SCRC (P-values <0.001); Table 2 and Figure 5. Maximum EGJ diameter was greater in both IDCR and SCRC than ACR (P-values <0.001), but EGJ-DI was similar (P-values = 0.411 and 0.138). EGJ-DI (P=0.591) and maximum EGJ diameter (P=0.467) were similar between IDCR and SCRC. The frequency of normal EGJ opening (i.e. EGJ-DI ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter ≥16mm) also differed by FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns (P<0.001) occurring in 90% of NCR, 67% of BCR, 18% of IDCR, 8% of ACR, and 5% of SRCR.

Figure 5. Association of FLIP Panometry contractile response and EGJ opening parameters.

FLIP Panometry EGJ opening parameters of EGJ-distensibility index (DI) and maximum EGJ diameter are plotted by each FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern: A) Normal contractile response, B) Borderline contractile response, C) Impaired/disordered contractile response, D) Absent contractile response, and E) spastic-reactive contractile response. The dashed box reflects the region of normal EGJ opening. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Spastic-reactive contractile response pattern

Among the entire patient cohort, SOCs were observed in 30/706 (4%) patients, sLESC were observed in 51/706 (7%) patients (there were 7 patients that had both a sLESC and SOC), and RRCs were observed in 4/706 (1%) patients (none also had SOC nor SSC). On comparison with the remainder of the study cohort without SRCR, patients with SCRC were older (mean (SD) age 64 (14) vs 53 (16) years; P=0.014), more likely to have hiatal hernia (30% vs 19%; P=0.032), and more likely to have esophageal diverticula (9% vs 2%; P=0.007). HRM classifications also differed between patients with and without SRCR (P<0.001); SRCR was observed in 18/57 (32%) of patients with type III achalasia on HRM, 4/15 (27%) of patients with distal esophageal spasm on HRM, and 7/15 (47%) of patients with hypercontractile esophagus on HRM. Only 8 (10% of 78) patients with SRCR had an HRM with normal motility or IEM without hiatal hernia or an epiphrenic diverticulum.

The SRCR cohort was further evaluated by comparing groups meeting criteria for SRCR and then assigned based on contractile activity in the esophageal body, thus either absent (i.e. contractile response isolated to sLESC), contractility present but without antegrade contractions, or contractility with antegrade contractions (Table 3). Differences were not detected with regard to age, gender, indication, endoscopy findings (including diverticulum), nor HRM classification. There was a trend toward greater frequency of hiatal hernia when antegrade contractions were present (P=0.060).

Table 3.

Comparison among contractile presence in patients with spastic-reactive contractile response.

| Body-contractility | Absent | Contractility without AC’s present | AC’s present |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n | 12 | 31 | 10 |

|

| |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 69 (11) | 64 (14) | 57 (14) |

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| |||

| SOC-present * | 0 | 25 (45) | 5 (50) |

|

| |||

| RRCs-present | 0 | 3 (5) | 1 (10) |

|

| |||

| SLESC-present * | 12 (100) | 35 (63) | 4 (40) |

|

| |||

| Gender, female | 5 (42) | 33 (59) | 5 (50) |

|

| |||

| Indication | |||

| Dysphagia | 10 (83) | 54 (96) | 10 (0) |

| Reflux symptoms | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Chest pain | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 |

|

| |||

| Endoscopy findings | |||

| Erosive esophagitis; | |||

| LA-A / LA-B | 0 / 0 | 1 (2) / 0 | 0 / 1 (10) |

| Non-obstructing ring | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Diverticulum | 1 (8) | 6 (11) | 0 |

|

| |||

| HRM-Chicago Classification | |||

| Type I achalasia | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Type II achalasia | 4 (33) | 8 (14) | 0 |

| Type III achalasia | 1 (8) | 14 (25) | 3 (30) |

| EGJ outflow obstruction | 2 (17) | 12 (21) | 3 (30) |

| Hypercontractile esophagus | 1 (8) | 6 (11) | 0 |

| Distal esophageal spasm | 0 | 4 (7) | 0 |

| Absent contractility | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| IEM | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 (10) |

| Normal motility | 3 (25) | 9 (16) | 3 (30) |

|

| |||

| HRM-EGJ-morphology 1 | |||

| Type I (no hiatal hernia) | 8 (67) | 43 (77) | 4 (40) |

| Type II-III (hiatal hernia) | 4 (33) | 13 (23) | 6 (60) |

P<0.05 on comparison between groups.

P=0.060 AC – antegrade contractions. SOC – sustained occluding contraction. RRC – repetitive antegrade contractions. sLESC – sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction.

Discussion

In this study of 706 symptomatic patients evaluated for esophageal motility disorders, we validated a classification scheme of FLIP Panometry contractile patterns of the esophageal response to distension (i.e. secondary peristalsis) by demonstrating the relationships with primary peristaltic function observed on HRM. The FLIP Panometry contractile response scheme was developed to reflect a potential pathophysiologic transition from normal to absence of secondary peristalsis, i.e. a qualitative transition from presence to absence of antegrade contractions. Additionally abnormal spastic motor responses occurring in response to distension can be identified that likely occur along a different continuum of esophageal motor dysfunction. The findings of a stepwise increase in important contractile measurements on manometry, such as DCI and number of normal swallows, support that the FLIP Panometry contractile patterns provide a valid scheme to categorize peristaltic vigor. While the relative agreement in esophageal contractility observed on FLIP Panometry and HRM demonstrates the general shared features between the evaluations of secondary peristalsis and primary peristalsis with two modalities, discordant responses also occurred. Thus, the two evaluations may provide a complementary role in the evaluation of esophageal motor function. Overall, the demonstration of the functional significance of the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns supports their use for the evaluation of esophageal motility.

We previously demonstrated that the unique contractile response pattern involving RACs during sustained esophageal distention represented normal esophageal body function.1, 6 When defined using the RAC Rule-of-6s, this pattern was associated with a clinical impression of normal esophageal motility and further, was not observed among patients with achalasia (and the associated absence of primary peristalsis).7, 8 In the present study that included a larger patient cohort that encompassed a broader spectrum of esophageal motor function (in addition to expansion of previously described cohorts), these findings remain consistent and this study further demonstrated that abnormal primary peristalsis is associated with abnormal secondary peristalsis as evaluated via FLIP Panometry. Thus, a normal contractile response on FLIP Panometry in the setting of a normal endoscopy can effectively exclude the presence of achalasia and could reduce the need for a HRM; clinical management could instead be directed toward reflux or a functional esophageal disorder.7, 8, 12 When esophageal dysmotility is observed on FLIP Panometry, it may be supportive of achalasia if also associated with reduced EGJ opening. When there is a finding of impaired or absent secondary peristalsis and normal EGJ opening, further evaluation of primary peristalsis with HRM should be considered when it would impact clinical management decisions, such as during an evaluation for anti-reflux surgery.

The similarities between the peristaltic evaluation with FLIP Panometry and HRM demonstrated in this study seem fundamental as the neuromuscular integrity necessary for coordinated peristalsis is thought to be similar for both primary and secondary peristalsis. However, discordance was also observed which is likely in part accounted for by inherent differences in triggering between primary and secondary peristalsis. In this study, we observed that 188/303 (62%) of patients with normal primary peristalsis on manometry had secondary peristalsis (antegrade contractions with NCR or BCR) on FLIP Panometry. This finding is consistent with previous data that described lower rates of successful secondary peristalsis in response to focal esophageal distention than primary peristalsis in cohorts of healthy controls and patients with reflux or dysphagia.10, 16 In contrast with these earlier studies that assessed secondary peristalsis with manometry and consistent with our previous reports, we also observed cases of patients with absent contractility on HRM, but with evidence of peristalsis or contractility on FLIP Panometry.8, 17 The reason for this finding is likely related to the dependence of catheter contact for manometry to detect peristalsis while FLIP Panometry can also detect non-lumen occluding contractions when there is dilatation of the esophageal lumen, such as in achalasia.17, 18

This study also demonstrated the relationship between secondary peristalsis and EGJ opening. When antegrade contractions are triggered, these generate a ramp of intrabolus pressure that facilitates opening of the EGJ. On the other hand, the absence of antegrade contractions was associated with a lesser degree of EGJ opening. This reflects the global evaluation of esophageal function that is assessed with FLIP Panometry and thus supports ongoing efforts to refine the classification of esophageal motility with FLIP Panometry. The validation of the contractile response patterns reported in this study will facilitate that application.

Early concepts of esophageal spasm were defined on manometry by simultaneous contractions, identified by rapid contractile front velocity, more recently supplanted by premature swallows with short distal latency.3, 19, 20 We initially described the RRC pattern as a frequent findings in a relatively small cohort of patients with type III achalasia on HRM and proposed RRCs as the spastic manifestation of distension induced contractility.17 However, we subsequently demonstrated that SOCs carried stronger predictive capabilities than RRCs when modeling FLIP parameters to differentiate between spastic (type III) achalasia and non-spastic (type I and II) achalasia.15 Additionally, we had questioned the specificity of the RRC pattern as we later observed RRCs in patients with GERD, eosinophilic esophagitis, and postfundoplication dysphagia, and noted these often occurred at low FLIP fill volumes (i.e. <50ml) that may be susceptible to movement artifact when the FLIP bag is incompletely filled.21–23 Hence, our definitions and analysis paradigms evolved to focus on the FLIP fill volumes that were less susceptible to movement artifact, while maintaining the fill volumes in which normal antegrade contractions were most commonly observed in healthy controls.6 Here we observed that the abnormal (i.e. not observed in healthy controls) contractile responses involving RRCs, SOCs, and sLESCs are most commonly observed in patients with spastic motor findings on HRM. However, they also appear to be related to hiatal hernia, and thus there is consideration that these response are ‘reactive’ to the associated obstruction or reflux. There also appears to be heterogeneity with the IDCR pattern as this pattern included patients with spastic HRM findings, as well as others with ineffective motility. Thus, future study is needed to clarify the mechanisms related to these findings, which will facilitate refinement of these classifications. However, these patterns represent abnormal findings with potential for clinical consequence, including an association with epiphrenic diverticula (even among patients with normal esophageal motility on HRM).12 Thus, we suggest that the presence of RRCs, SOCs, or sLESCs on FLIP Panometry warrants further evaluation with HRM and esophagram for clinical clarification.

While this study carries value in describing and validating a novel qualitative FLIP Panomery approach based on specific patterns in a large patient cohort, this study has several limitations. One limitation is the lack of additional clinical outcomes beyond HRM. Thus future studies are needed to apply additional outcome data; esophageal reflux monitoring is a candidate as a previous study demonstrated more severe esophageal acid exposure in patients with abnormal FLIP Panometry contractile responses.22 Unfortunately, few patients in this esophageal motility cohort that were primarily evaluated for dysphagia completed esophageal reflux monitoring. Application of additional clinical outcome data may help refine the classification scheme, such as the threshold between BCR and IDCR or within the IDCR classification to improve defining weak versus spastic features. Additionally, this study cohort is reflective of patients evaluated at an esophageal motility referral center, and thus the prevalence of disease may limit generalizability to other practice environments. Finally, while a study strength lies in the external evaluation to confirm agreement with FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns, this was not specifically designed as an inter-rater agreement study; thus while the degree of agreement is reassuring, specific conclusions are limited in this regard and a future focused study should be pursued to further demonstrate rater agreement and the generalizability of this approach.

In conclusion, the FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns described here reflect a pathophysiologic transition from normality to abnormality paralleling primary peristaltic function as assessed on HRM. Additionally, discordance between secondary peristalsis on FLIP Panometry and primary peristalsis on HRM is sometimes expected due to differences between the two stimuli (distension vs swallows) and capabilities of the two testing modalities (i.e. detection of non-occluding esophageal contractions). Overall, this study supports the role of FLIP Panometry in evaluating esophageal motility as it accurately identifies normal motility and also defines another group that should undergo further diagnostic testing. Future studies focused on correlating contractile response patterns with objective outcome measures and developing more quantitative measures of function will continue to improve its utility in assessing patients with esophageal symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by P01 DK117824 (JEP) from the Public Health service and American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award (DAC).

Disclosures:

JEP, PJK, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic Inc.

DAC: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting)

RY: Institutional Consulting Agreement: Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Diversatek; Consultant: Phathom Pharmaceuticals; Research support: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; Advisory Board with Stock Options: RJS Mediagnostix

AK: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting)

CPG: Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, IsoThrive, Quintiles (consulting)

WK: Janisys (Consulting)

PJK: Ironwood (Consulting); Reckitt Benckiser (Consulting)

JEP: Medtronic (Speaking. Consulting, IP Licensing), Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek (Consulting, Grant), Takeda (Speaking, Consulting, Grant), Astra Zeneca (Speaking), Torax/Ethicon (Speaking, Consulting), Ironwood (Consulting, Grant), Impleo (Grant).

AJB, JaEP, END: nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Rogers MC, Lin CY, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Utilizing functional lumen imaging probe topography to evaluate esophageal contractility during volumetric distention: a pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(7):981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0((c)). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson DA, Kou W, Lin Z, et al. Normal Values of Esophageal Distensibility and Distension-Induced Contractility Measured by Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):674–81 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson DA, Kou W, Pandolfino JE. The rhythm and rate of distension-induced esophageal contractility: A physiomarker of esophageal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Baumann AJ, Donnan EN, Triggs JR, et al. Normal Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry Findings Associate With Lack of Major Esophageal Motility Disorder on High-Resolution Manometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Stimulation and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in normal subjects. Gut. 1994;35(2):152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Gut. 1994;35(11):1523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Triggs JR, Carlson DA, Beveridge C, Kou W, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry Identifies Achalasia-Type Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(10):2209–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson DA, Baumann AJ, Donnan EN, Krause A, Kou W, Pandolfino JE. Evaluating esophageal motility beyond primary peristalsis: Assessing esophagogastric junction opening mechanics and secondary peristalsis in patients with normal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021:e14116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(5):601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittal RK, Frank EB, Lange RC, McCallum RW. Effects of morphine and naloxone on esophageal motility and gastric emptying in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31(9):936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson DA, Kou W, Rooney KP, et al. Achalasia subtypes can be identified with functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) panometry using a supervised machine learning process. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Integrity and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1995;36(4):499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, et al. The Functional Lumen Imaging Probe Detects Esophageal Contractility Not Observed With Manometry in Patients With Achalasia. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S, Zifan A, Kumar D, Mittal RK. Genesis of Esophageal Pressurization and Bolus Flow Patterns in Patients with Achalasia Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49(1):145–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Carlson D, et al. Distal esophageal spasm in high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: defining clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):469–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Ritter K, Lin Z, Pandolfino JE. Mechanisms of repetitive retrograde contractions in response to sustained esophageal distension: a study evaluating patients with postfundoplication dysphagia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;314(3):G334–G40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson DA, Kathpalia P, Craft J, et al. The relationship between esophageal acid exposure and the esophageal response to volumetric distention. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Hirano I, Gonsalves N, Zalewski A, Pandolfino JE. Evaluation of esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis: an update and comparison of functional lumen imaging probe analytic methods. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1844–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.