Abstract

Oncocytic adrenocortical tumours (OATs) or oncocytomas are extremely rare and are usually benign and nonfunctional. We report the case of a 4-year-old male with a right-sided, functional oncocytic adrenocortical adenoma, who presented with precocious puberty and Cushing’s syndrome. After work-up, the patient underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy. The excised adrenal mass weighed 21 g and measured 3.5 cm in maximum dimension. Histological examination demonstrated no features suggestive of aggressive biological behaviour. The patient had no features of recurrent or metastatic disease and had prepubertal testosterone levels with suppressed hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis twelve months after the surgery. A discussion of this case and a review of the literature on functional OATs in the pediatric population are presented.

Keywords: adrenal oncocytoma, functioning adrenal adenoma, pediatric adrenal tumours

INTRODUCTION

Oncocytic adrenocortical tumours (OATs) or neoplasms are extremely rare. Most of the cases are nonfunctional and benign, predominantly affecting middle-aged women. About 183 cases have been reported globally according to a systematic review by Costanzo et al., with most patients in the age group of 40 to 60 years.1,2 In the pediatric age group, only 9 cases have been reported so far.

CASE

A 4-year-old male presented with penile enlargement, deepening of voice and excessive body hair growth for over six months. He had recently gained 6 kg in over 6 months with no evidence of growth spurt. The mother also noticed the patient’s excess body odour, aggressive behaviour and irritability.

On physical examination, he had Cushingoid facies and prehypertensive blood pressure (BP) at 108/70 (50th percentile for age and height, 95 mm Hg for systolic BP and 51 mm Hg for diastolic BP). His weight was in the 75th percentile for age, while his height was in the 10th percentile of the combined Indian Academy of Pediatrics (2015) and WHO (2006) height chart for boys 0 to 18 years. His mid-parental height corresponded to the 10th percentile. Examination of the external genitalia revealed a stretched penile length of 10 cm, prepubertal testes (testicular size 3 cc) and Tanner stage 3 pubic hair with no concomitant axillary or facial hair. Abdominal examination was normal, with no palpable mass. There was no history of similar clinical presentation or malignancy in the family.

Hormonal studies showed a basal cortisol level of 19.8 μg/dL (reference range 4.3 to 22.4 μg/dL) and a plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level <10 pg/mL (reference range 10 to 50 pg/mL). Additional tests indicated disruption of diurnal cortisol rhythm (midnight cortisol 21.3 μg/dL) and non-suppression of cortisol after intake of dexamethasone 1 mg (19 μg/dL). Levels of total serum testosterone (231 ng/dL, reference range for age <20 ng/dL), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) (1261 μg/dL, reference rage 32 to 276 μg/dL) were also elevated. Serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (0.37 mIU/mL) and luteinising hormone (LH) (<0.07 mIU/mL) were normal and below detection limit, respectively.

The patient’s bone age by Tanner Whitehouse III method was advanced by three years compared to his chronological age. Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) of the abdomen revealed a 3.3 cm x 3.0 cm x 3.7 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion with a baseline density of 43 HU in the right suprarenal region arising from the medial limb of the right adrenal gland. The lesion was confined to the adrenal gland with no evidence of local invasion or enlarged abdominal lymph nodes.

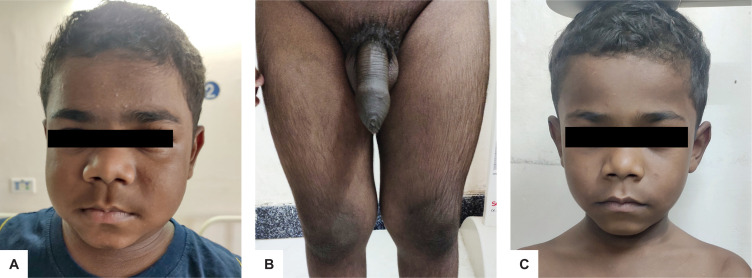

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation of the patient showing facial fullness and plethora (A), enlarged penile shaft and appearance of pubic hair (B). There was a decrease in facial fullness and plethora three months postoperatively (C).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen in coronal view showed a solid, rounded, well-defined tumour in the right adrenal gland.

The patient underwent right laparoscopic adrenalectomy with removal of a well-defined mass weighing 21 g and measuring 3.5 cm in maximum dimension. Gross examination showed a well-circumscribed tumour without any breach in the capsule. Histopathologic examination of the tumour revealed cords, trabeculae and sheets of tumour cells, which were round to polygonal with minimal nuclear pleiomorphism, central nuclei, prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Majority of the tumour cells exhibited oncocytic morphology. Mitosis count was 3/50 high power field with no evidence of atypical mitosis. Meticulous examination revealed no evidence of capsular invasion, vascular invasion, necrosis or extra-adrenal extension of the tumour. On immunohistochemistry, the tumour cells were positive for inhibin and negative for S-100, melan-A and chromogranin. The MIB-1 proliferation index was 5%. According to the Lin-Weiss-Bisceglia (LWB) criteria, the tumour did not fulfill any of the major or minor criteria for malignancy; therefore, a diagnosis of oncocytic adrenocortical adenoma was made.3

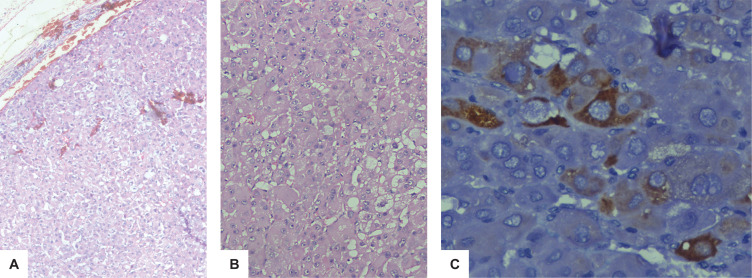

Figure 3.

Histopathologic examination showed an capsulated tumour with cells exhibiting abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in cords and trabecular pattern (H&E, 100x) (A). Abundant oncocytic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei with minimal nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli were noted. Mitoses are inconspicuous (H&E, 200x) (B). Immunohistochemical examination using diaminobenzidine staining (400x) with DAKO monoclonal antibody showing focal strong expression of inhibin in tumour cells (C).

The postoperative clinical course was uneventful. The patient was started on hydrocortisone supplementation, which was tapered rapidly to a replacement dose of 7.5 mg given in two divided doses. Serum testosterone levels normalised two weeks post-surgery. On the follow-up visit three months after surgery, the patient had remission of Cushingoid features with no further progression of pubertal development. Regular follow-up was planned.

During his last visit, one year after surgery, he had prepubertal testosterone levels with suppressed hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Hydrocortisone replacement (7.5 mg) was continued. There was no further progression of puberty. CECT of the abdomen was negative for local remission.

DISCUSSION

OATs are a rare subtype that represents approximately 10% of adrenocortical tumours.2 As defined by Bisceglia et al., these neoplasms are made up of at least 50% oncocytic cells and can be either pure (>90%) or mixed (50 to 90% oncocytic cells) variant.3 The spectrum of these tumours includes benign adenomas/oncocytomas, oncocytic carcinomas and oncocytic neoplasms of uncertain malignant potential.4 Since the first account of OAT in 1986 by Kakimoto et al., 183 cases have been reported.1,5 Most of these tumours were detected incidentally, with 20% of them demonstrating evidence of malignancy.1 Approximately 10 to 20% of the OATs were functional; majority were non-functional.2

OATs predominantly affect adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 46 years and a female preponderance by a ratio of 1.8:1.6 Adrenocortical tumours are particularly rare in children and account for less than 0.2% of all pediatric neoplasms. Nine cases of OATs in the pediatric age population were previously reported.7-15 All the patients except one were females, with ages between 3.5 and 16 years.15 Most tumours involved the right adrenal gland, with sizes ranging from 2.5 to 17.5 cm. Six of the cases were diagnosed as adrenocortical adenoma (oncocytoma) on histopathology, while one case was labeled as borderline tumour according to the LWB classification.3 All these tumours were functional with variable clinical presentations. Four females presented with virilization. Three patients (two females and one male) presented with precocious puberty; two co-presented with Cushing’s syndrome. Our case also had similar clinical presentation. All four patients who presented with Cushing’s syndrome were younger. Other major presenting symptoms included fatigue, headache, abdominal pain and palpable abdominal mass. Kawahara et al., described a case of interleukin-6-producing oncocytic adrenocortical adenoma in an 11-year-old female, who presented with persistent fever and weight loss.13 Clinicopathological data of reported cases of OATs in the pediatric population including our patient are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of functional oncocytic adrenocortical tumours in pediatric patients

| Pt | Case | Country | Age, year/ Gender | Clinical Presentation | Main Hormone | Tumour Location, Size (cm) | Year | Follow up, Outcome | Hormonal Status on Follow-up | LWB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gumy-Pause et al | Switzerland | 12/F | Acne, abdominal pain | A4, TT | L, 5 | 2008 | 18 months Remission | Normal | Benign |

| 2 | Tahar et al | Tunisia | 6/F | Pseudo PP | E2 | R, 3.5 | 2008 | 12 months Remission | Normal | Benign |

| 3 | Lim et al | Korea | 14/F | Virilization | DHEAS, TT | R, 17.5 | 2010 | 2 weeks Remission | Normal | Borderline |

| 4 | Subbiah et al | India | 3.5/F | Premature pubarche, Virilization | DHEAS, TT, Cortisol | R, 2.5 | 2012 | 1 month Remission | TT DHEAS: normal Cortisol: NA | Benign |

| 5 | Sharma et al | India | 16/F | Virilization | DHEAS, TT | R, 11.6 | 2012 | 3 months Remission | NA | NA |

| 6 | Pereira et al | Portugal | 5.8/F | Pseudo PP, Cushing’s | Cortisol | L, 4.5 | 2014 | 64 months Remission | NA | Benign |

| 7 | Kawahara et al | Japan | 11/F | Fever, Weight loss | IL6 | L, 4.5 | 2014 | 48 months Remission | Normal | NA |

| 8 | Yordanova et al | Bulgaria | 9/F | Virilization | A4, TT | L, 2.2 | 2015 | 11 months Remission | Normal | Benign |

| 9 | Badi et al | Saudi Arabia | 5/M | Pseudo PP, Cushing’s | Cortisol, TT | R, 3 | 2018 | 28 months Remission | TT, cortisol: normal | Benign |

| 10 | Our case | India | 4/M | Pseudo PP, Cushing’s | Cortisol, TT, DHEAS |

R, 3.5 | 2020 | 12 months Remission | TT: normal on Hydrocortisone | Benign |

A4, androstenedione; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; E2, estradiol; F, female; IL-6, interleukin-6; L, left; LWB, Lin-Weiss-Bisceglia criteria; M, male; NA, not available; PP, precocious puberty; R, right; TT, total testosterone

OATs are usually large, rounded, encapsulated and well-circumscribed, with an average diameter of 8 cm (2 to 20 cm). Microscopically, the tumour cells are highly eosinophilic, granular and arranged in solid, trabecular, tubular or papillary patterns. Electron microscopic studies of these tumours have shown the cytoplasm of oncocytes to be rich in mitochondria. The immune profile shows diffuse positivity for vimentin, melan-A, synaptophysin and alpha-inhibin.2 Wiess score, used for categorizing adrenal tumours, overestimates the potential malignancy risk owing to parameters that are intrinsic to oncocytic cells, such as eosinophilic character, high nuclear grade and diffuse architecture. Hence, the World Health Organization in 2017 recommended the LWB score for categorizing OATs.4

Imaging studies such as computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging are not useful to differentiate between benign and malignant oncocytic neoplasms. Surgical excision is the definite treatment for both large and functional tumours. Recent advances in laparoscopic techniques have made the application of minimally invasive procedures possible even in the presence of a large adrenal mass. The biological behaviour of OATs differs from other benign adrenal cortical tumours and carries a better prognosis. Patients with malignant OATs had a median overall survival of 58 months, which is different compared to patients with non-oncocytic adrenocortical carcinoma (31.9 months).6

Our patient did not satisfy any of the criteria for high risk stratification and was then classified as having adrenal oncocytic adenoma. Surgical resection of functional OAT normalizes the serum hormonal levels and results in resolution of hormonal overproduction-related clinical symptoms and signs. None of the reported cases of functional OATs, including our patient, had recurrence of disease during the follow-up period ranging from two weeks to 64 months. Seven of the cases had normal hormonal levels appropriate for age and sex at follow-up. None of the cases developed central precocious puberty during follow-up. There are no guidelines for the follow-up of patients with OATs. Considering the possible risk of adrenocortical carcinoma, meticulous follow-up is planned for our patient with hormonal and imaging investigations.

CONCLUSION

OATs are extremely rare in childhood and adolescence. Most pediatric OATs are benign and functional, occurring predominantly in females, with excellent clinical outcomes. In children with adrenal mass and associated features of either virilisation or precocious puberty or Cushing’s syndrome, OATs should be considered.

Learning points

Oncocytic adrenocortical tumours (OATs) are rare, consisting mostly of benign and functional adrenal tumours in the pediatric population.

Clinical, biochemical and radiological investigation cannot differentiate benign oncocytic adenomas from carcinomas, mandating adrenalectomy in most of the cases for histopathological confirmation and definitive treatment of functional tumours.

The prognosis of patients with OATs is good when compared to conventional adrenocortical carcinoma, with an excellent rate of remission and higher overall survival.

Ethical Considerations

Patient consent was obtained before submission of the manuscript.

Statement of Authorship

All authors certified fulfillment of ICMJE authorship criteria.

Author Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding Source

None.

References

- 1.Costanzo PR, Paissan AL, Knoblovits P. Functional plurihormonal adrenal oncocytoma: Case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2017;6(1):37-44. PMID: . PMCID: . 10.1002/ccr3.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mearini L, Del Sordo R, Costantini E, Nunzi E, Porena M. Adrenal oncocytic neoplasm: A systematic review. Urol Int. 2013;91(2):125-33. PMID: . 10.1159/000345141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisceglia M, Ben-Dor D, Pasquinelli G. Oncocytic adrenocortical tumors. Pathol Case Rev. 2005;10(5):228-42. 10.1097/01.pcr.0000175102.22075.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renaudin K, Smati S, Wargny M, et al. Clinicopathological description of 43 oncocytic adrenocortical tumors: Importance of Ki-67 in histoprognostic evaluation. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(11): 1708–16. PMID: . 10.1038/s41379-018-0077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakimoto S, Yushita Y, Sanefuji T, et al. Non-hormonal adrenocortical adenoma with oncocytoma-like appearances. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1986; 32(5):757-63. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong DD, Spagnolo DV, Bisceglia M, Havlat M, McCallum D, Platten MA. Oncocytic adrenocortical neoplasms—A clinicopathologic study of 13 new cases emphasizing the importance of their recognition. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(4):489-99. PMID: . 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumy-Pause F, Bongiovanni M, Wildhaber B, Jenkins JJ, Chardot C, Ozsahin H. Adrenocortical oncocytoma in a child. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(3):718-21. PMID: . 10.1002/pbc.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tahar GT, Nejib KN, Sadok SS, Rachid LM. Adrenocortical oncocytoma: A case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(5):E1-3. PMID: . 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim Y-J, Lee S-M, Shin J-H, Koh H-C, Lee Y-H. Virilizing adrenocortical oncocytoma in a child: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(7):1077-9. PMID: . PMCID: . 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.7.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subbiah S, Nahar U, Samujh R, Bhansali A. Heterosexual precocity: Rare manifestation of virilizing adrenocortical oncocytoma. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(3):294-7. PMID: . PMCID: . 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma D, Sharma S, Jhobta A, Sood RG. Virilizing adrenal oncocytoma. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2012;2:76. PMID: . PMCID: . 10.4103/2156-7514.104309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira BD, Rios ES, Cabrera RA, Portugal J, Raimundo L. Adrenocortical oncocytoma presenting as Cushing’s syndrome: An additional report of a paediatric case. Endocr Pathol. 2014;25(4): 397-403. PMID: . 10.1007/s12022-014-9325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawahara Y, Morimoto A, Onoue A, Kashii Y, Fukushima N, Gunji Y. Persistent fever and weight loss due to an interleukin-6-producing adrenocortical oncocytoma in a girl—Review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(8):1107-10. PMID: . 10.1007/s00431-014-2292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yordanova G, Iotova V, Kalchev K, et al. Virilizing adrenal oncocytoma in a 9-year-old girl: Rare neoplasm with an intriguing postoperative course. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28(5-6):685-90. PMID: . 10.1515/jpem-2014-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Badi MK, Al-Alwan I, Al-Dubayee M, et al. Testosterone- and cortisol-secreting oncocytic adrenocortical adenoma in the pediatric age-group. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21(6):568–73. PMID: . 10.1177/1093526617753045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]