Abstract

Venezuelan Haemorrhagic Fever is an endemic zoonosis exhibiting a high lethality. Discovered decades ago, it is still causing seasonal hemorrhagic fever outbreaks. With the ongoing migration crisis, transmission and spreading to other countries in Latin America remains a latent threat that should be monitored, particularly in light of recent cases.

Keywords: Guanarito virus, reemerging, rodent-borne diseases, Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever, zoonoses

Tropical diseases have reemerged in Venezuela as a consequence of an unprecedented humanitarian crisis [1,2], coinciding with a complex growing migration crisis from Venezuela to other Latin American countries. Although malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and more recently yellow fever [[1], [2], [3], [4]], have been highlighted through publications, and alerts by PAHO; other infections such as Venezuelan Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) [5], continue to be overlooked. We discuss the current epidemiological situation of this Mammarenavirus and its potential implications in view of the current migratory situation.

VHF is a viral haemorrhagic zoonosis with a high fatality rate (∼30%). The disease is caused by the Guanarito Mammarenavirus (species of the Mammarenavirus genus), which includes 40 species of the family Arenaviridae (order Bunyavirales) [6,7]. Like other family members, the Guanarito virus is known to spread through endemic rodents [[8], [9], [10]]. In VHF-Venezuelan endemic areas, some of them also serve as reservoirs for other viruses of the Bunyavirales order, Orthohantaviruses, such as Caño Delgadito.

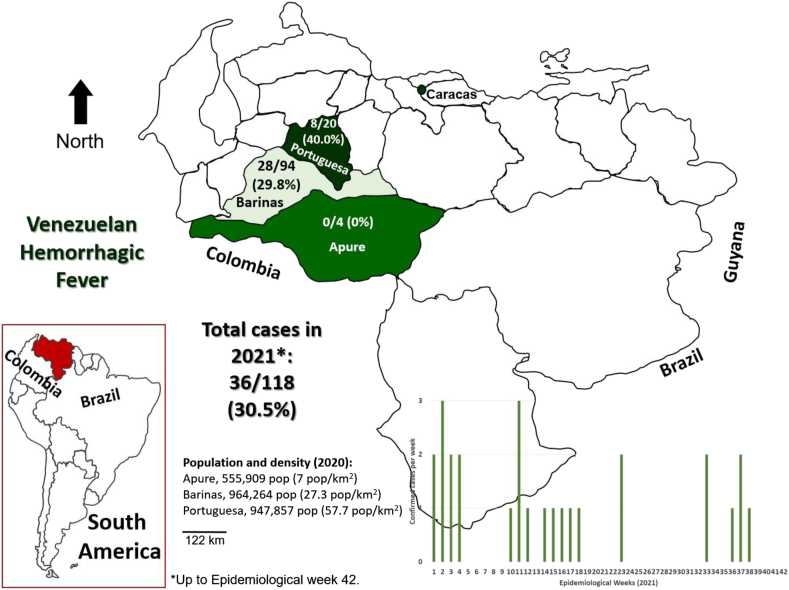

Although VHF human-to-human transmission has not been reported, other Mammarenavirus in Latin America, like the Chapare virus, is known to spread through human-to-human transmission [7]. The seasonal emergence of the Guanarito virus, poses a latent risk for the spread of imported cases to the region; 118 suspected cases have been investigated in Venezuela, in states in close proximity to the Colombian border. Of them, 36 have been confirmed (30.5%) (Fig. 1). In Venezuela, the icteric haemorrhagic febrile syndrome occurs more often in adult males exerting agricultural activities. Because of overlapping areas of endemism with other icterohaemorrhagic pathogens, the differential diagnosis in the country includes other clinically relevant conditions such leptospirosis, dengue and yellow fever, among others that, although not currently under surveillance, should also be considered (e.g. rickettsiosis).

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of Venezuelan Haemorrhagic Fever cases in Venezuela, 2021 (up to the Epidemiological Week 42); cases were confirmed by RT-PCR at Virology Reference Laboratory in Caracas. Apure, Barinas and Portuguesa are endemic for Zygodontomys brevicauda, Sigmodon alstoni and S. hispidus, who serve as natural reservoirs of the virus. Source: Dirección de Vigilancia Epidemiológica, Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Salud (Ministry of Health of Venezuela).

The most recent 2021 yellow fever outbreak has underscored the potential implications and relevance for disease surveillance in Venezuela [3], despite the availability of an effective vaccine. In contrast, no vaccines nor effective treatments are currently available for VHF, although ribavirin has shown slight clinical improvement for some cases. Despite its seasonality, the recent emergence of VHF cases should not be underestimated and should be considered a public health concern, not only for Venezuela but for the region. Further, by performing a search in PubMed, it becomes evident that there has been a significant lack of published studies on VHF over the last years. VHF tends to exhibit cyclic haemorrhagic fever peaking every 5-to-7 years. So far, the PAHO has yet not issued an alert regarding VHF.

Mammarenaviruses, such as VHF in Venezuela and other endemic countries, have important implications for public health [7]. Although imported cases have not been reported to date, cases of other Mammarenaviruses in returning travellers from other endemic countries have been described in the USA, Canada and Europe [8]. There is a pressing need to fill in the gap of knowledge on the diverse ecological and epidemiological aspects of Mammarenaviruses in Latin America, especially in Venezuela, where a complex humanitarian and migratory crisis continues to evolve, carrying the potential menace for disease importation through exodus given that the risk of exposure amongst domestic and international travellers and people living in rodent-disease endemic areas exists. Therefore, a differential diagnostic approach of viral haemorrhagic fevers is helpful, particularly among travellers returning from areas like rural Venezuela, where the Guanarito virus is endemic. Like for most viral haemorrhagic fevers, early diagnosis of cases is a key feature for outbreak responses and disease contention.

Transparency declaration

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to dedicate this article to the memory of Dr. Pedro Belisario, MD, a general surgeon from Venezuela, who died after SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 associated renal failure in November 2021.

References

- 1.Suárez J., Carreño L., Paniz-Mondolfi A., et al. Infectious diseases, social, economic and political crises, anthropogenic disasters and beyond: Venezuela 2019 – implications for public health and travel medicine. Rev Panamericana de Enferm Infec. 2018;1:73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grillet M.E., Hernandez-Villena J.V., Llewellyn M.S., Paniz-Mondolfi A.E., Tami A., Vincenti-Gonzalez M.F., et al. Venezuela's humanitarian crisis, resurgence of vector-borne diseases, and implications for spillover in the region. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e149–e161. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodríguez-Morales A.J., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Suárez J.A., Franco-Paredes C., Forero-Peña D.A., Mattar S., et al. Yellow fever reemergence in Venezuela – implications for international travelers and Latin American countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021:102192. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Morales M., Suarez J.A., Martinez-Buitrago E. Migration crisis in Venezuela and its impact on HIV in other countries: the case of Colombia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18:9. doi: 10.1186/s12941-019-0310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salas R., de Manzione N., Tesh R.B., Rico-Hesse R., Shope R.E., Betancourt A., et al. Venezuelan haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1991;338:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charrel R.N., de Lamballerie X. Zoonotic aspects of arenavirus infections. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escalera-Antezana J.P., Rodriguez-Villena O.J., Arancibia-Alba A.W., Alvarado-Arnez L.E., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Rodriguez-Morales A.J. Clinical features of fatal cases of Chapare virus hemorrhagic fever originating from rural La Paz, Bolivia, 2019: a cluster analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020:101589. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milazzo M.L., Cajimat M.N., Duno G., Duno F., Utrera A., Fulhorst C.F. Transmission of Guanarito and Pirital viruses among wild rodents, Venezuela. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:2209–2215. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesh R.B., Wilson M.L., Salas R., De Manzione N.M., Tovar D., Ksiazek T.G., et al. Field studies on the epidemiology of Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever: implication of the cotton rat Sigmodon alstoni as the probable rodent reservoir. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:227–235. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez E. Difusión del conocimiento de la fiebre hemorrágica venezolana (FHV) en los ámbitos académicos, profesionales y culturales del país. Observador del Conocimiento (ONCTI) 2021;6:12–31. [Google Scholar]