Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between breastfeeding and the development of paediatric asthma.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted with MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health source databases. Retrospective/prospective cohorts in children aged <18 years with breastfeeding exposure reported were included. The primary outcome was a diagnosis of asthma by a physician or using a guideline-based criterion. A secondary outcome was asthma severity.

Results

42 studies met inclusion criteria. 37 studies reported the primary outcome of physician-/guideline-diagnosed asthma, and five studies reported effects on asthma severity. Children with longer duration/more breastfeeding compared to shorter duration/less breastfeeding have a lower risk of asthma (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.93; I2 = 62.4%). Similarly, a lower risk of asthma was found in children who had more exclusive breastfeeding versus less exclusive breastfeeding (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72–0.91; I2=44%). Further stratified analysis of different age groups demonstrated a lower risk of asthma in the 0–2-years age group (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.63–0.83) and the 3–6-years age group (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.55–0.87); there was no statistically significant effect on the ≥7-years age group.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding are associated with a lower risk of asthma in children aged <7 years.

Short abstract

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies suggest that duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding are associated with a lower risk of asthma in children aged <7 years https://bit.ly/3p804PG

Introduction

The 2018 Global Asthma Report estimated that 339 million people worldwide are affected by asthma [1]. This number continues to rise, particularly in children [2, 3]. Multiple factors contribute to the development of asthma, including genetic predisposition and environmental factors such as early respiratory infection, antibiotic use and smoking exposure [4–6]. Despite a multitude of studies on the subject, the relationship between breastfeeding and asthma continues to be difficult to elucidate. This is due to a variety of challenges, such as recall bias of breastfeeding exposure, inconsistent statistical management of confounders, variable definitions of diagnosis and a general scarcity of randomised controlled trials (RCT) and high-quality cohort studies [7, 8].

Three systematic reviews with meta-analyses related to asthma and breastfeeding have been published in the past 10 years (supplementary table E1) [8–10]. Two indicated that any breastfeeding or increased breastfeeding was protective against asthma. The third review showed no statistically significant association between breastfeeding and asthma [10]. These previous reviews included many case–control/cross-sectional studies of low quality, used less specific outcomes such as wheezing and self-reported asthma [8–10], and one of them only looked at children aged >5 years [9, 10]. All meta-analyses had substantial heterogeneity. The most recent review was completed by Lodge et al. [9] and included articles up until 2014.

We aimed to provide an updated meta-analysis exploring the relationship between breastfeeding and asthma in childhood. To increase the quality of the included studies and reduce heterogeneity relative to prior meta-analyses, the current analysis was restricted to cohort studies and/or RCTs. Strict definitions of asthma were used to develop a more specific assessment for how the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding impact the development of childhood asthma at different ages.

Methods

Search strategy

In brief, a comprehensive search of cohort studies published until January 2020 in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health databases was used. In addition, a manual search through references of included studies and review articles for additional resources was carried out. Full details of the search can be found in supplementary table E2. Further details on the study protocol can be accessed on PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ identifier number CRD42018099831).

Study selection, and inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if 1) they captured breastfeeding data (i.e. presence, duration and/or exclusivity); 2) had an outcome of a diagnosis of asthma fitting the specified criteria; 3) included data for children aged <18 years; and 4) was a cohort study/RCT.

Definitions of breastfeeding

Exclusive breastfeeding was based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, where infants received only breastmilk with no other liquids or solids. All other types of breastfeeding that did not meet these criteria were categorised as partial breastfeeding, i.e. breastfeeding with solids/formula.

Breastfeeding comparisons were made as follows. 1) More exclusive versus less exclusive breastfeeding encompasses comparisons where exclusive breastfeeding was done relatively longer than the comparator. For example, exclusive breastfeeding ≥3 months compared to exclusive breastfeeding <3 months or partial breastfeeding 1 month or no breastfeeding; 2) more versus less breastfeeding encompasses all comparisons where the intervention was relatively longer in duration than the comparator. For example, exclusive breastfeeding ≥3 months versus exclusive feeding <3 months or partial breastfeeding >1 month versus no breastfeeding; and 3) ever versus never encompasses any breastfeeding duration that was compared to no breastfeeding at all.

Definition of asthma

Only studies with either physician-diagnosed asthma or appropriate strict guidelines for asthma definition were included. These guidelines included those from the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, the Global Initiative for Asthma and the Canadian Paediatric Society [11–13]. Alternatively, included studies could use secondary outcomes of asthma severity such as hospitalisation, medication use and spirometry.

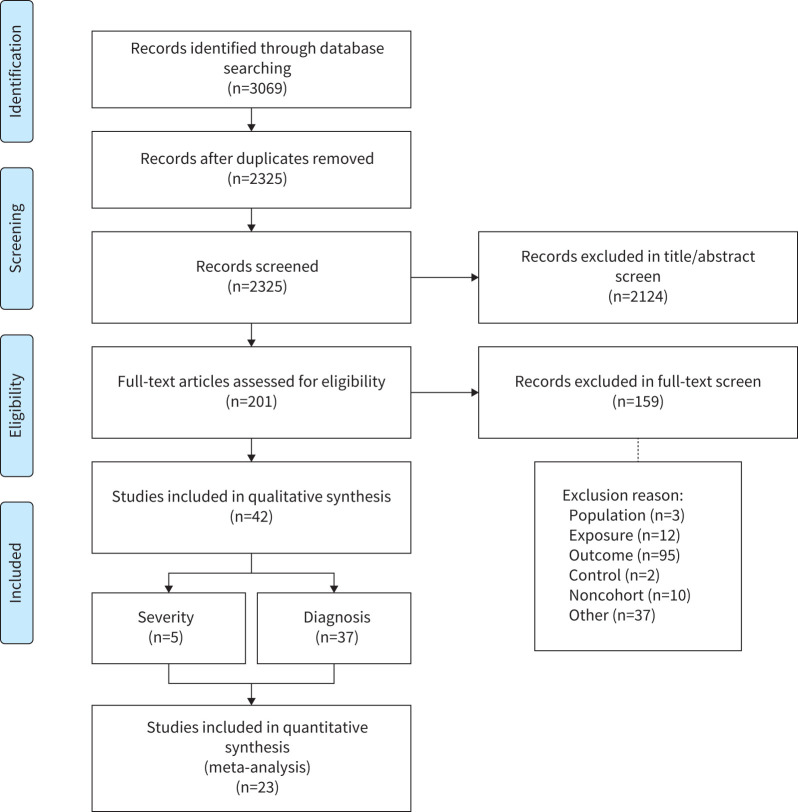

Data extraction

Two evaluators (MX and ED) independently assessed all articles through abstract and title screening. Articles that met the inclusion criteria during the initial screening underwent full-text screening to determine eligibility for data extraction. Any disagreements at the level of abstract/title or full-text screening were resolved through consensus. Where consensus between the two evaluators was not possible, a third reviewer was consulted (OK). Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the article identification process.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart highlighting the article identification process.

Data were extracted using a standardised form and included author name, study design, study period, age of assessment, country, sex, risk factors, asthma definition, reported breastfeeding and method of assessment, study outcomes and adjustment for confounders.

The primary outcome of interest was asthma risk. The secondary measure of interest was asthma severity. The effect sizes reported on the risk of asthma and/severity outcomes included information on hazard ratios, risk ratios, odds ratios and prevalence.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The risk of bias of individual articles was evaluated using a modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies (table 1). When assessing the comparability of cohorts, the confounders of interest were gestational age, family history of asthma/atopy and pre-/post-natal exposure to smoking. This was based on previously identified significant asthma risk factors [56]. In addition, article quality was then translated to “good”, “fair”, or “low” based on the number of stars and additional pre-set criteria (table 1). This step was important as certain study features are more relevant to the overall quality than others, but may receive the same weighting in the standard NOS system. The method for converting the NOS stars was adapted from a previous study published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and outlined in table 1 [57].

TABLE 1.

Study quality based on modified# Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies

| First author, year [reference] | 1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort | 2) Selection of the nonexposed cohort | 3) Ascertainment of exposure | 4) Appropriate temporality for breastfeeding assessment # | 5) Comparability of cohorts based on the design or analysis controlled for confounders (out of 2) | 6) Assessment of outcome | 7) Appropriate number of follow-ups conducted for detection of outcome # | 8) Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | Total (out of 9) | Quality ¶ |

| Ajetunmobi, 2015 [14] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Alm, 2008 [15] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | |||

| Bacopoulou, 2009 [16] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 4 | Low | ||||

| Bion, 2016 [17] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9 | Good |

| Burr, 1993 [18] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Low | |||

| Chiu, 2016 [19] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | Good | |

| Davidson, 2010 [20] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 4 | Low | ||||

| den Dekker, 2016 [21] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Fair | |||

| Elliott, 2008 [22] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 4 | Low | ||||

| Fredriksson, 2007 [23] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Fair | |||

| Karmaus, 2008 [24] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | |

| Kiechl-Kohlendorfer, 2007 [25] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Klingberg, 2019 [26] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Klopp, 2017 [27] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Kull, 2002 [28] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Lee, 2017 [29] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | Good | |

| Leung, 2016 [30] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | Good | |

| Mandhane, 2007 [31] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Low | |||

| McConnochie, 1986 [32] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 4 | Low | ||||

| Midodzi, 2010 [33] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Midwinter, 1987 [34] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 4 | Low | ||||

| Mihrshahi, 2007 [35] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | Fair | |

| Milner, 2004 [36] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 3 | Low | |||||

| Miyake, 2008 [37] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Fair | |||

| Nwaru, 2013 [38] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | Good | |

| Nwaru, 2013 [39] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Low | ||||

| Oddy, 2002 [40] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Oddy, 2004 [41] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Sbihi, 2016 [42] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Low | |

| Silvers, 2009 [43] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Silvers, 2012 [44] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| Standl, 2012 [45] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Low | |||

| Strömberg Celind, 2018 [46] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | |||

| Sunyer, 2006 [47] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Turner, 2008 [48] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Fair | ||||

| van Meel, 2017 [49] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | Good | ||

| von Kobyletzki, 2012 [50] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Fair | |||

| Wickman, 2003 [51] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Wilson, 1998 [52] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Wright, 2000 [53] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair | ||

| Wright, 2001 [54] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5 | Low | |||

| Yamakawa, 2015 [55] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 6 | Fair |

#: NOS modifications. 1) Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study; since this is essentially an assessment of temporality of the exposure, but is not particularly applicable to the types of articles we are screening, we changed it to “Does the article assess for breastfeeding at an appropriate time to avoid recall bias (i.e. <2 years of age)?”. 2) Comparability: our three adjusted confounders were family history of asthma or atopy, gestational age and cigarette exposure pre- or post-natally (studies received one star for adjusting for all three, and an additional star for adjusting for other confounders). 3) Outcome (follow-up length): follow-up length is not relevant for the detection of outcome we are looking for; instead we looked at the frequency of follow-up as this is more sensitive for transient asthma diagnoses that may not be chronic; this will be rater-dependent; however, points that will be considered include the total number of follow-ups as well as the timing of the follow-ups (i.e. asthma at 10 years: four well-spaced follow-ups versus three in the first year and one at 10 years). ¶: NOS conversion to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality low-, fair- and good-quality scale. Low: <4 NOS stars OR no adjustment for confounders (5 stars) OR nonrepresentative population (1 star) OR major flaw in methodology as determined by assessors; fair: 4–6 NOS stars with adjustment of confounders (5 stars) AND representative sample (1 star) AND an appropriate number of follow-ups conducted for detection of outcome (7 stars); good: >6 NOS stars AND adjustment of confounders with the inclusion of key confounders (5 stars) AND representative sample (1 stars) AND an appropriate number of follow-ups conducted for detection of outcome (7 stars) AND assessment of breastfeeding at a temporally appropriate time to reduce recall bias (4 stars).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data are grouped based on type of breastfeeding, duration of breastfeeding and asthma outcome variables. The analysis was further stratified by different age groups (0–2, 3–6 and ≥7 years) and study quality. The duration of breastfeeding was analysed as more versus less breastfeeding, ever versus never breastfeeding, breastfeeding for ≥3 months versus <3 months and ≥6 months versus <6 months. For studies that collected data at multiple ages in the same participants, only the oldest was used in the analysis. If a study had a group comparing the duration of feeding 4 months versus 1 month, it would be included in the ≥3- versus <3-month analysis. Studies that compared multiple different feeding durations to the same reference group could have multiple groups in the same analysis, but no two included groups could have overlapping intervention groups. Studies could have groups included in multiple different analyses (i.e. exclusive more versus less, ever versus never, age-stratified analysis, etc.). Studies that did not have duration-specific comparisons but instead used per month of additional breastfeeding as outcomes could not be included within the meta-analyses.

Where available, adjusted hazard ratios, odds ratios or relative risks were preferentially extracted in the data extraction sheet. A very limited number of studies reported hazard ratios and relative risks; only studies that reported odds ratio were used to estimate pooled effect size during meta-analysis using a random-effects inverse variance method [58]. Additionally, we assessed the publication bias using a funnel plot and Begg's test for small-study effect [59, 60]. Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistics and potential sources of heterogeneity for a number of variables (age, study design, country of study, birth cohort and ethnicity) using meta-regression [61]. The meta-analyses were conducted using Stata (version 16) software.

Results

Search findings

The database search resulted in 3069 articles (figure 1). Following initial title/abstract screening, 193 full-text articles were reviewed for eligibility based on the criteria described. 42 articles met the inclusion criteria, from which data were extracted; however, data from only 23 articles were suitable for meta-analysis. 37 articles analysed the impact of breastfeeding on asthma development, and five analysed its impact on asthma severity (figure 1). Of these 42 studies, 38 were prospective cohorts and four were retrospective cohorts. No RCTs met inclusion criteria. 37 articles from Western countries and five articles from Eastern countries were identified; however, there was no representation of low-income countries as defined by the World Bank [62]. Refer to supplementary table E3 for individual study information.

Study quality: risk of bias

Of the 42 articles, 14 (33%) were of good quality [17, 19, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 33, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 49], 16 (38%) were of fair quality [14, 15, 21, 23, 25, 28, 35, 37, 46–48, 50–53, 55] and 12 (29%) were of low quality [16, 18, 20, 22, 31, 32, 34, 36, 39, 42, 45, 54] based on our modified NOS scoring system (table 1). Low-quality articles were typically single-centre studies, tertiary-care settings or populations selected for specific illnesses. Additionally, they may not have had an appropriate assessment of breastfeeding to minimise recall bias, lacked adjustments for major confounders and/or did not assess for asthma within optimal time frames. Of the 42 included articles, 32 (76%) adjusted for multiple confounders and 18 (43%) adjusted for three key confounders (gestational age, family history and smoking exposure) [24]. Overall, a large majority of studies (71%) fell within fair and good quality for cohort studies.

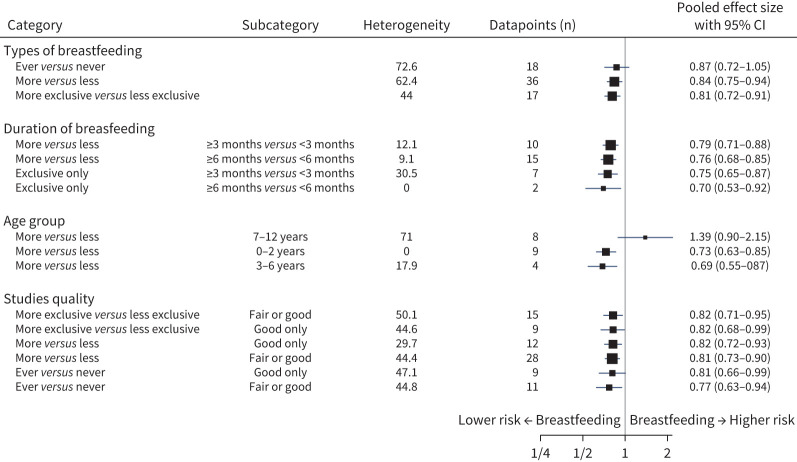

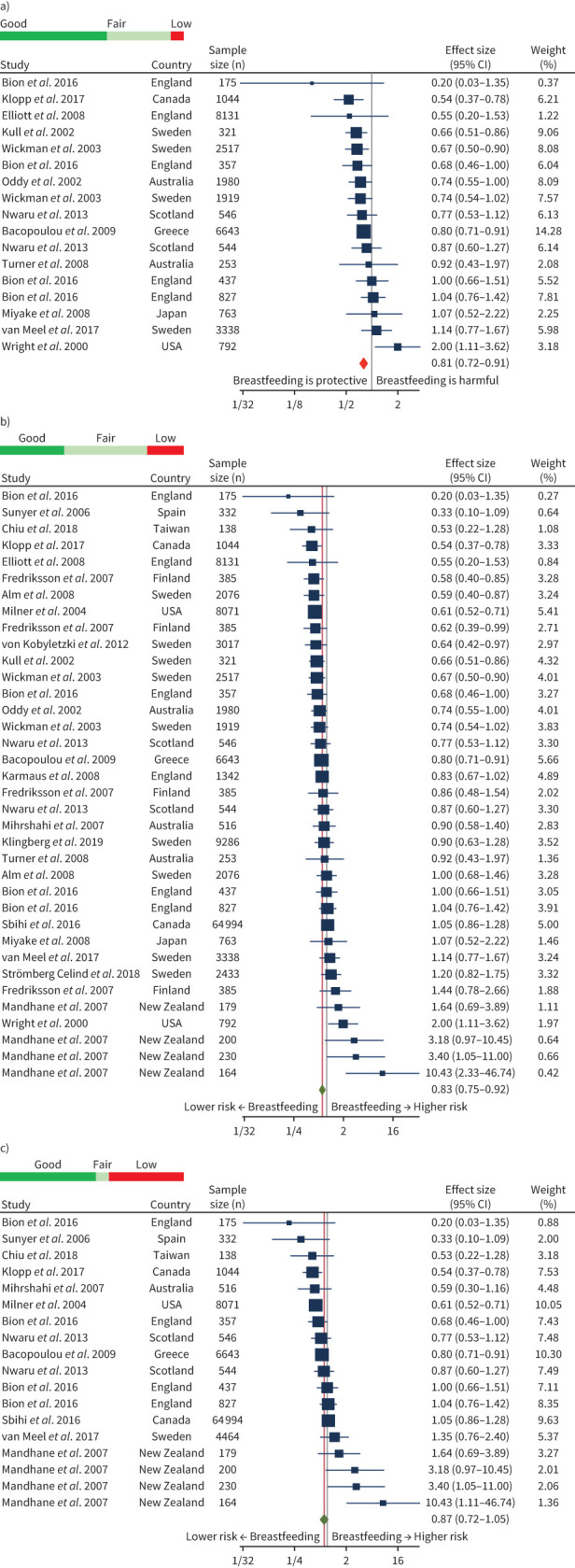

Diagnosis of asthma

Children who had more exclusive breastfeeding compared to those with less exclusive breastfeeding had a 19% lower risk of asthma (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72–0.91; I2=44.0%) (figure 2). Similarly, children with more breastfeeding compared to those with less breastfeeding had a 16% lower risk of asthma (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.93; I2=62.4%). For children that were ever breastfed compared to never breastfed, the lowered risk was not statistically significant (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.72–1.04; I2=72.6%) (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Pooled effect sizes and quality# of main analyses. a) More¶ exclusive+ breastfeeding versus less exclusive breastfeeding; b) more breastfeeding versus less breastfeeding; and c) ever versus never breastfed. Random-effects restricted maximum likelihood model. #: Coloured bar represents proportion of groups of good/fair/poor quality; ¶: “more” implying longer duration of breastfeeding; +: “exclusive” indicating breastmilk only with no other solids/liquids.

For children with more exclusive breastfeeding versus less, when either low-quality studies or both low- and fair-quality studies were excluded, the protective effect against asthma remained similar at 18% and 19%, respectively (figure 3). However, for the more versus less breastfeeding analysis, the 16% protective effect against asthma was greater when excluding low-quality articles (19%) or both low- and fair-quality articles (18%). In the case of ever versus never breastfeeding, exclusion of low-quality (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.95; I2=44.8%) or low- and fair-quality studies (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66–0.998; I2=47.1%) demonstrated a greater magnitude and developed a statistically significant difference (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Pooled effect sizes of all meta-analyses including breastfeeding type, duration, age and study quality.

Duration of breastfeeding

Children with exclusive breastfeeding for ≥6 months compared to <6 months had a 30% lower risk of asthma (0.70, 0.53–0.92) (figure 3); however, these data were pooled from only two articles [48, 51]. The article published by Wickman et al. [51] in 2003 assessed 4089 children for doctor-diagnosed asthma at 2 years of age. They found a statistically significant benefit with ≥6 months versus <3 months of exclusive breastfeeding (0.67, 0.5–0.91). The second study, published in 2008 by Turner et al. [48], included 154 infants recruited from a single antenatal clinic. They found no statistically significant benefit for doctor-diagnosed asthma diagnosis at 3, 6 and 11 years, although values trended toward a beneficial effect, particularly in the 3-year-old analysis (0.44, 0.19–1.00). Both studies were assessed as fair-quality. Exclusive breastfeeding for ≥3 months versus <3 months had 25% lower risk of asthma (0.75, 0.65–0.87).

Children with any type of breastfeeding for ≥6 months compared to <6 months had a 24% lower risk (0.76, 0.68–0.85). Any breastfeeding for ≥3 months versus <3 months had a 21% lower risk of asthma (0.79, 0.71–0.87).

Age of children

Breastfeeding in the age groups 0–2 years and 3–6 years had 27% and 31% lower risk of asthma, respectively, but no statistically significant effect in the ≥7-years age group (figure 3). Articles in the meta-analyses for ages <7 years were predominantly good/fair quality, while age ≥7 years articles were predominantly of low quality and mainly came from different age groups from a single study [31].

Asthma severity

Five articles assessed the duration of breastfeeding on the impact of asthma severity [14, 20, 25, 30, 55]. There were no articles that quantified the number of exacerbations, medication use, frequency or spirometry. The surrogate marker of severity commonly seen within these studies was hospitalisation due to asthma. There was little consistency in the potential trends/effects of breastfeeding. Two articles demonstrated trends towards protective odds ratios [25, 55]; two articles had trends towards harmful hazard ratios [14, 30]; and the fifth contained only prevalence data [20]. We did not perform a meta-analysis due to inconsistent outcome measures, few articles and lower quality studies.

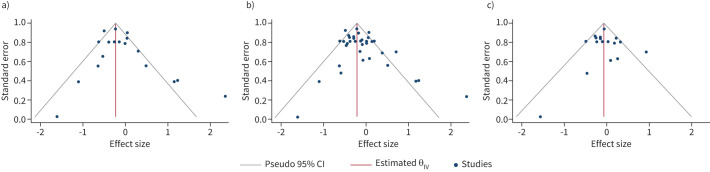

Publication bias and small-study effects

Publication bias was assessed by graphical representation of funnel plots, and Begg's test assessed small-study effects. We found no publication bias and no small-study effects for exclusive breastfeeding versus less exclusive breastfeeding, more breastfeeding versus less breastfeeding and for ever versus never breastfeeding (figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Funnel plots evaluating for publication bias in the main analyses. a) More# exclusive¶ breastfeeding versus less exclusive breastfeeding; b) more breastfeeding versus less breastfeeding; and c) ever versus never breastfed. #: “more” implying longer duration of breastfeeding; ¶: “exclusive” indicating breastmilk only with no other solids/liquids.

Heterogeneity

The heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistics. There was wide variation in heterogeneity ranging from 44% in the exclusive breastfeeding group to 62% in the more versus less breastfeeding group; the greatest (73%) was seen in the ever versus never breastfeeding group. We explored the potential sources of heterogeneity (study design, birth cohort, ethnicity, country and age) in ever versus never breastfeeding using a meta-regression command. Only ethnicity (p<0.03) was found to contribute to heterogeneity significantly, whereas no statistically significant heterogeneity was contributed by study design (p=0.729), country of study (p=0.680) and age (p=0.815). Birth cohort was dropped from the model due to collinearity.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that both longer duration of any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding is associated with a decreased likelihood of developing asthma, particularly in children aged <7 years. The results of longer duration of any breastfeeding demonstrated similar protective effects compared to prior reviews; however, this review is the first to clearly demonstrate a pooled protective effect of longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Current WHO guidelines recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months [63]. Although the findings of our study support this recommendation, only two articles were included in the meta-analysis for exclusive breastfeeding ≥6 months versus <6 months [48, 49]. This probably reflects the challenge that many parents experience with meeting this recommendation. In addition, national breastfeeding guidelines vary in their recommendations for timing of solid food introduction, with many citing 4–6 months [64]. We found a reduced risk of asthma development in children with ≥3 months of exclusive breastfeeding when compared with those <3 months. Additionally, any breastfeeding for ≥3 months and ≥6 months showed a significant benefit for asthma prevention. Thus, babies who do not meet the 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding guidelines may still receive some protection against asthma development with partial or intermittent breastfeeding.

When stratifying by age, the benefit of breastfeeding was evident for ages 0–2 years and 3–6 years, but no benefit was seen in those aged ≥7 years. This lack of effect may be driven by a broad representation of low-quality articles within that analysis. In addition, it may be that breastfeeding protects against earlier-onset asthma rather than late-onset asthma, as has been suggested previously [8]. This phenomenon was described in an article by Sbihi et al. [65], which examined a nationally representative Canadian birth cohort of 11 652 children. They identified three different childhood asthma trajectories: late-onset nonremitting, early-onset chronic and transient asthma. A lack of breastfeeding only led to increased risk of transient and early onset of chronic asthma. There was no significant impact of breastfeeding in the late-onset cohort, suggesting that factors other than breastfeeding may be equally or more important to asthma development in older children.

Strengths and limitations

With our updated search, 11 new cohort studies were identified since 2014 [14, 17, 19, 24, 41, 43, 44, 47–50], when the most recent systematic review search was conducted [8]. Our search was broad and incorporated more databases than other recent systematic reviews [8–10]. Of the recently completed systematic reviews, only Lodge et al. [9] included any allied health databases. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were more stringent than previous studies, as we included only cohort studies. This improves the overall quality of the meta-analyses and mitigates recall bias. Similar breastfeeding cut-offs were used with prior systematic reviews with the addition of a more exclusive versus less exclusive comparison in our study.

Additionally, we selected studies with clear reporting of physician diagnosis of asthma or strict guideline-based diagnosis of asthma [8, 66]. Prior systematic reviews included studies with wheeze as an outcome [8–10]. This could have confounding effects, as breastfeeding may also reduce viral-induced wheeze. Our approach does not completely reduce the potential for misdiagnosis of asthma as objective physiological evidence was not assessed in these studies. However, performing spirometry, bronchodilator reversibility or bronchial provocation challenges is often not feasible in young children. On the flip side, by limiting the diagnosis of asthma, some of the nuances of a highly heterogeneous disease may be lost. Additionally, we were unable to stratify for current asthma and ever asthma as was done by Dogaru et al. [8].

To assess quality, we adapted the NOS to place more weight on a study's ability to prevent recall bias, adjust for confounders and assess asthma within reasonable time frames. These are important factors that would not be directly accounted for in the standard NOS for cohort studies. Despite a strict scoring system, 37% of studies were considered fair, and 35% of studies were of good quality. It is difficult to directly compare the quality of analyses within our study to previous systematic reviews as each used different quality criteria; however, they all report the majority of studies being of low or very low quality within their analyses (table 1).

Heterogeneity in the data depended on the analysis, but the majority were within the moderate range (figure 3). For major analyses, our heterogeneity was similar or lower compared to analyses in previous systematic reviews. This may be explained by our use of more stringent inclusion criteria, including limitation to cohort studies and physician-/criterion-diagnosed asthma, thus reducing methodological heterogeneity. Despite this, some analyses still showed considerable heterogeneity, with the country being the major contributor. This could be related to prognostic factors within different countries.

Although we aimed to improve the quality of our meta-analyses by restricting observational data to cohort studies, this limited the total number of studies available. For example, we did not identify any robust cohort studies assessing the relationship between asthma and breastfeeding in low-income countries, thus leading to less generalisability in those regions.

There were limited data addressing maternal atopy and its influence on breastfeeding effects. Similarly, we were unable to stratify by sex, which has been highlighted as a risk factor in recent literature with evidence that childhood asthma severity and frequency are differentially affected by the pubertal stage between males and females [67]. It would be interesting to learn whether breastfeeding similarly has differential benefits impacted by sex. The additional restriction of articles to the English language may have introduced bias into our results, reducing generalisability.

Conclusions

This review highlights that breastfeeding has an important role in reducing the risk of developing asthma in early childhood. Compared to previous systematic reviews, the relationship is better established due to the higher quality of articles used in the meta-analyses. This result, along with many other health benefits attributed to breastfeeding, reinforces breastfeeding recommendations by national and international bodies.

Future studies designed to explore the relationship between breastfeeding and asthma should utilise prospective cohort design to minimise recall bias in breastfeeding duration and regularly assess for the diagnosis and current symptoms of asthma. Stringent criteria for diagnosis should be used to minimise misdiagnosis of wheeze due to other causes. Studies need to ensure confounders are accounted for and aim to adjust for key confounders such as gestational age, exposure to cigarette smoking and atopic history.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00504-2021.SUPPLEMENT (361.4KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Author contributions: M. Xue and E. Dehaas share joint first authorship. M. Xue, E. Dehaas and O.P. Kurmi designed the review. Database search, article identification, data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment were conducted by M. Xue and E. Dehaas. M. Xue and O.P. Kurmi analysed the data. M. Xue, E. Dehaas and O.P. Kurmi drafted the manuscript. O.P. Kurmi provided advice at multiple different stages. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript submission. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others have been omitted.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

This review is registered in PROSPERO with identifier number CRD42018099831.

Data sharing: Full datasets can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest: M. Xue has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Dehaas has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N. Chaudhary has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: P. O'Byrne has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: I. Satia has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: O.P. Kurmi has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Global Asthma Network . The Global Asthma Report 2018. 2018. Available from: www.globalasthmareport.org/

- 2.Beasley R, Semprini A, Mitchell EA. Risk factors for asthma: is prevention possible? Lancet 2015; 386: 1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Asthma. 2021. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma Date last updated: 3 May 2021.

- 4.Castro-Rodríguez JA, Stern DA, Halonen M, et al. . Relation between infantile colic and asthma/atopy: a prospective study in an unselected population. Pediatrics 2001; 108: 878–882. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelfand EW. Pediatric asthma: a different disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009; 6: 278–282. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-090RM [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duijts L. Fetal and infant origins of asthma. Eur J Epidemiol 2012; 27: 5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9657-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MS. Does breast feeding help protect against atopic disease? Biology, methodology, and a golden jubilee of controversy. J Pediatr 1988; 112: 181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogaru CM, Nyffenegger D, Pescatore AM, et al. . Breastfeeding and childhood asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014; 179: 1153–1167. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lodge CJ, Tan DJ, Lau MX, et al. . Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015; 104: 38–53. doi: 10.1111/apa.13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brew BK, Allen CW, Toelle BG, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating breast feeding and childhood wheezing illness. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011; 25: 507–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Thoracic Society (BTS) , Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) . British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. 2019. Available from: www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

- 12.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2020. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/

- 13.Ducharme FM, Dell SD, Radhakrishnan D, et al. . Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers: a Canadian Thoracic Society and Canadian Paediatric Society position paper. Paediatr Child Health 2015; 20: 353–371. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.7.353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajetunmobi OM, Whyte B, Chalmers J, et al. . Breastfeeding is associated with reduced childhood hospitalization: evidence from a Scottish Birth Cohort (1997–2009). J Pediatr 2015; 166: 620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alm B, Erdes L, Möllborg P, et al. . Neonatal antibiotic treatment is a risk factor for early wheezing. Pediatrics 2008; 121: 697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacopoulou F, Veltsistan A, Vassi I, et al. . Can we be optimistic about asthma in childhood? A Greek cohort study. J Asthma 2009; 46: 171–174. doi: 10.1080/02770900802553128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bion V, Lockett GA, Soto-Ramírez N, et al. . Evaluating the efficacy of breastfeeding guidelines on long-term outcomes for allergic disease. Allergy 2016; 71: 661–670. doi: 10.1111/all.12833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burr ML, Limb ES, Maguire MJ, et al. . Infant feeding, wheezing, and allergy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child 1993; 68: 724–728. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.6.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu CY, Liao SL, Su KW, et al. . Exclusive or partial breastfeeding for 6 months is associated with reduced milk sensitization and risk of eczema in early childhood: the PATCH Birth Cohort Study. Medicine 2016; 95: e3391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson R, Roberts SE, Wotton CJ, et al. . Influence of maternal and perinatal factors on subsequent hospitalisation for asthma in children: evidence from the Oxford record linkage study. BMC Pulm Med 2010; 10: 14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.den Dekker HT, Sonnenschein-van der Voort AMM, de Jongste JC, et al. . Early growth characteristics and the risk of reduced lung function and asthma: a meta-analysis of 25,000 children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137: 1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott L, Henderson J, Northstone K, et al. . Prospective study of breast-feeding in relation to wheeze, atopy, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122: 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredriksson P, Jaakkola N, Jaakkola JJ. Breastfeeding and childhood asthma: a six-year population-based cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2007; 7: 39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-7-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karmaus W, Dobai AL, Ogbuanu I, et al. . Long-term effects of breastfeeding, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and recurrent lower respiratory tract infections on asthma in children. J Asthma 2008; 45: 688–695. doi: 10.1080/02770900802178306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Horak E, Mueller W, et al. . Neonatal characteristics and risk of atopic asthma in schoolchildren: results from a large prospective birth-cohort study. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 1606–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klingberg S, Brekke HK, Ludvigsson J. Introduction of fish and other foods during infancy and risk of asthma in the All Babies In Southeast Sweden cohort study. Eur J Pediatr 2019; 178: 395–402. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-03312-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klopp A, Vehling L, Becker A, et al. . Do infants fed expressed breast milk have an increased risk of developing childhood asthma compared to directly breastfed infants? Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2017; 13: Suppl. 1, A11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kull I, Wickman M, Lilja G, et al. . Breast feeding and allergic diseases in infants – a prospective birth cohort study. Arch Dis Child 2002; 87: 478–481. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.6.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee M-T, Wu C-C, Ou C-Y, et al. . A prospective birth cohort study of different risk factors for development of allergic diseases in offspring of non-atopic parents. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 10858–10870. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung JY, Kwok MK, Leung GM, et al. . Breastfeeding and childhood hospitalizations for asthma and other wheezing disorders. Ann Epidemiol 2016; 26: 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandhane PJ, Greene JM, Sears MR. Interactions between breast-feeding, specific parental atopy, and sex on development of asthma and atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnochie KM, Roghmann KJ. Parental smoking, presence of older siblings, and family history of asthma increase risk of bronchiolitis. Am J Dis Child 1986; 140: 806–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Midodzi WK, Rowe BH, Majaesic CM, et al. . Early life factors associated with incidence of physician-diagnosed asthma in preschool children: results from the Canadian Early Childhood Development cohort study. J Asthma 2010; 47: 7–13. doi: 10.3109/02770900903380996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Midwinter RE, Morris AF, Colley JRT. Infant feeding and atopy. Arch Dis Child 1987; 62: 965–967. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.9.965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mihrshahi S, Ampon R, Webb K, et al. . The association between infant feeding practices and subsequent atopy among children with a family history of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37: 671–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milner JD, Stein DM, McCarter R, et al. . Early infant multivitamin supplementation is associated with increased risk for food allergy and asthma. Pediatrics 2004; 114: 27–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Sasaki S, et al. . Breastfeeding and the risk of wheeze and asthma in Japanese infants: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2008; 19: 490–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nwaru BI, Craig LCA, Allan K, et al. . Breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods during infancy in relation to the risk of asthma and atopic diseases up to 10 years. Clin Exp Allergy 2013; 43: 1263–1273. doi: 10.1111/cea.12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nwaru BI, Takkinen H-M, Niemelä O, et al. . Timing of infant feeding in relation to childhood asthma and allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131: 78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oddy WH, Peat JK, de Klerk NH. Maternal asthma, infant feeding, and the risk of asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 110: 65–67. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oddy WH, Sherriff JL, de Klerk NH, et al. . Breastfeeding, body mass index, and asthma and atopy in children. Adv Exp Med Biol 2004; 554: 387–390. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sbihi H, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, et al. . Perinatal air pollution exposure and development of asthma from birth to age 10 years. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1062–1071. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00746-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silvers KM, Frampton CM, Wickens K, et al. . Breastfeeding protects against adverse respiratory outcomes at 15 months of age. Matern Child Nutr 2009; 5: 243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00169.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silvers KM, Frampton CM, Wickens K, et al. . Breastfeeding protects against current asthma up to 6 years of age. J Pediatr 2012; 160: 991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Standl M, Sausenthaler S, Lattka E, et al. . FADS gene cluster modulates the effect of breastfeeding on asthma. Results from the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. Allergy 2012; 67: 83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strömberg Celind F, Wennergren G, Vasileiadou S, et al. . Antibiotics in the first week of life were associated with atopic asthma at 12 years of age. Acta Paediatr 2018; 107: 1798–1804. doi: 10.1111/apa.14332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sunyer J, Torrent M, Garcia-Esteban R, et al. . Early exposure to dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, breastfeeding and asthma at age six. Clin Exp Allergy 2006; 36: 1236–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner S, Zhang G, Young S, et al. . Associations between postnatal weight gain, change in postnatal pulmonary function, formula feeding and early asthma. Thorax 2008; 63: 234–239. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Meel ER, de Jong M, Elbert NJ, et al. . Duration and exclusiveness of breastfeeding and school-age lung function and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017; 119: 21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Kobyletzki LB, Bornehag C-GG, Hasselgren M, et al. . Eczema in early childhood is strongly associated with the development of asthma and rhinitis in a prospective cohort. BMC Dermatol 2012; 12: 11. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wickman M, Melén E, Berglind N, et al. . Strategies for preventing wheezing and asthma in small children. Allergy 2003; 58: 742–747. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson AC, Forsyth JS, Greene SA, et al. . Relation of infant diet to childhood health: seven year follow up of cohort of children in Dundee infant feeding study. BMJ 1998; 316: 21–25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM, et al. . Maternal asthma status alters relation of infant feeding to asthma in childhood. Adv Exp Med Biol 2000; 478: 131–137. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46830-1_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM, et al. . Factors influencing the relation of infant feeding to asthma and recurrent wheeze in childhood. Thorax 2001; 56: 192–197. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.3.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Kato T, et al. . Breast-feeding and hospitalization for asthma in early childhood: a nationwide longitudinal survey in Japan. Public Health Nutr 2015; 18: 1756–1761. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castro-Rodriguez JA, Forno E, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, et al. . Risk and protective factors for childhood asthma: what is the evidence? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.John M Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science . Evaluation and Treatment of Cryptorchidism. In: Comparative Efficacy Review Summary Guides for Clinicians. Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riley RD, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011; 342: 964–967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Begg CB. A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis by P. Macaskill, S. D. Walter and L. Irwig, Statistics in Medicine, 2001; 20: 641–654. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1803. doi: 10.1002/sim.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 2002; 21: 1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The World Bank . Low Income. 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-income/

- 63.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 8: CD003517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koletzko B, Hirsch NL, Jewell JM, et al. . National recommendations for infant and young child feeding in the World Health Organization European Region. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020; 71: 672–678. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sbihi H, Koehoorn M, Tamburic L, et al. . Asthma trajectories in a population-based birth cohort. Impacts of air pollution and greenness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 607–613. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0164OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michel G, Silverman M, Strippoli MPF, et al. . Parental understanding of wheeze and its impact on asthma prevalence estimates. Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 1124–1130. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00008406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zein JG, Erzurum SC. Asthma is different in women. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015; 15: 28. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00504-2021.SUPPLEMENT (361.4KB, pdf)