Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is integral to HIV prevention; however, the influence of PrEP use and PrEP use disclosure on condom use is unclear among Latinx men who have sex with men (LMSM). This study explored associations of LMSM PrEP use and use disclosure on consistent dyadic condom use in the past 6 months. Participants were 130 HIV-negative PrEP and non-PrEP using LMSM ages 20–39 years. Two-level logistic regression models assessing individual- and dyadic-level predictors on condom use were fitted using R. Participants reported a mean of four sexual partners (n=507 dyads). Participants who reported using PrEP or having more sexual partners were more likely to use condoms; however, participants who reported disclosing PrEP use were less likely to use condoms. Future longitudinal studies should characterize approaches to increase informed personal health choices and conversations about PrEP, condom use, and other HIV risk-reduction strategies using network methodologies.

Keywords: Men who have sex with men, PrEP, Condoms, Hispanic Americans, Risk Reduction Behavior

RESUMEN

La pastilla PrEP es un nuevo método profiláctico para prevenir el contagio del VIH. Aun no se ha determinado la manera en que el consumo de PrEP y las conversaciones sobre el uso de PrEP puedan influenciar en el uso de condones entre los hombres Latinos que tienen relaciones sexuales con otros hombres (HLSH). Este estudio exploró las asociaciones entre el uso y la divulgación del uso de PrEP con el uso de condones durante las relaciones sexuales que los HLSH tuvieron en los últimos 6 meses. En este estudio participaron un total 130 HLSH que eran VIH-negativos usuarios. Los participantes podían ser usuarios o no usuarios de PrEP, pero todos debían tener entre 20 y 39 años. Estimamos modelos de regresión logística de dos niveles, utilizando el programa R, para identificar factores individuales y diádicos asociados con el uso de condones. Los participantes reportaron un promedio de cuatro parejas sexuales (n=507 diadas). Encontramos que los participantes que reportaron usar PrEP o tenían un promedio mayor de parejas sexuales tenían una mayor probabilidad de haber usando condones. Sin embargo, la probabilidad de haber usados condones se redujo en los participantes que comunicaron a sus parejas sexuales que usaban PrEP. Es necesario implementar otros estudios longitudinales para entender como diseñar estrategias basadas en redes sociales que promuevan conversaciones sobre PrEP y el uso de condones.

INTRODUCTION

Although the national rate of new HIV diagnoses has plateaued in the general population from 2014–2018, HIV incidence has increased among young Latinx men who have sex with men (LMSM) ages 13–24 years (1–3). If current incidence rates persist, approximately one in five LMSM will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime (4). Miami-Dade County, Florida, is one of the counties with the highest number of new HIV cases in the United States (U.S.), and experiences an HIV incidence four times that of the national rate (1, 2). In Miami-Dade County, more than one out of every two new HIV diagnoses occur among LMSM, signifying a pressing need for additional biomedical and behavioral (together termed “biobehavioral”) prevention efforts utilizing condoms and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) within this population facing substantial HIV disparities (5).

Previously established predictors of condomless sex has been associated with partner closeness (6), serodifference (6–9), use of alcohol/drugs (7, 9–11), HIV status disclosure (8), exposure to discrimination due to gay-identification (12), and gay affirmation (a self-affirmation of gay identity in which feeling that being gay is an important and positive part of one’s identity and being gay is normal and fulfilling) (13, 14). Findings from previous studies suggest that gay affirmation is correlated with increases in condom use self-efficacy (15–17).

Additionally, endorsement of the traditional Latinx cultural values of simpatía (promotion of harmony in relationships) and machismo (expectation of men to detach themselves from any feminine attributes and that men have uncontrollable sexual urges) has been negatively associated with condom use during anal sex for LMSM (9). The Latinx cultural value familismo (familism) is associated with increases in condom use (18). Familism emphasizes the importance of individuals accepting responsibility of their families and close friends (19). Based on this interpretation of familism, we hypothesize that LMSM with higher beliefs of familism may be more likely to use PrEP or condoms. The association between Latinx-specific cultural values and uptake of HIV preventive behaviors necessitates the importance of examining the role that cultural factors play on PrEP use, PrEP use disclosure, and condom use among LMSM.

In accordance with the risk compensation framework, in which risk behaviors increase following use of other risk reduction methods (20–22), findings from previous studies suggest that condom use intention may decrease after PrEP uptake (23, 24). Reasons for decreased condom use intention include barriers to arousal and an increased temptation for condomless sex, which is perceived as more pleasurable (25). However, other studies have found that PrEP uptake does not influence condom use (26–29). Marcus et al. (2019) suggested that there is a population-level decline in condom use among MSM that is not due to the effects of risk compensation. Instead, MSM may be experiencing an increasing need for alternatives to condom dissemination programs, such as PrEP programs (30). These mixed findings suggest that additional factors may influence condom use (20–22, 26–29).

Geospatial networking apps used to find sexual partners allow users to display and/or disclose PrEP use status (24); however, few studies have investigated the effects of PrEP use disclosure on condom use. Due to the perception that PrEP users engage in condomless sex, MSM who disclose PrEP use may find it difficult to negotiate condom use (31). Hooks and Gross (2020) found that MSM are more likely to perceive PrEP users as being more warm and/or trustworthy relative to individuals who do not use PrEP (32). Additionally, the authors found that White PrEP users are perceived to be more likely to engage in condomless sex and group sex compared to non-White groups, suggesting the need to study the role that race plays on the association between PrEP use disclosure and condom use (32).

The role of PrEP use and PrEP use disclosure on condom use is unclear. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which is often posited to explain condom use among MSM (33), can only predict limited variance in condom use intentions and condom use behavior (24% and 12.4% variance, respectively) (33). Thus, additional factors at other levels, such as social network factors may be needed to explain condom use. In the context of this study, the Social Action Theory can explain condom use based on both personal characteristics (e.g., PrEP use) and dyadic social interaction factors (e.g., PrEP disclosure) (34). Egocentric network studies have successfully used multilevel analyses to describe correlates of condom use within a prespecified time period (35). The present study aimed to identify correlates of condom use at the personal and dyadic social interaction levels using multilevel modeling. We hypothesized that, among LMSM, PrEP use and PrEP use disclosure during sex will be associated with consistent condom use with each sexual partner. Further, we hypothesized that there would be an interaction effect between PrEP use and racially identifying as White on consistent condom use.

METHODS

Study sample, eligibility criteria, and recruitment

We utilized data from a cross-sectional social network study of the sexual practices of LMSM living in Miami-Dade County. Participants were recruited from a South Florida community-based organization using respondent-driven sampling methods. Briefly stated, the parent study, PrEParados enrolled 130 participants grouped into 1 of 10 social networks. The project coordinator first recruited 12 seeds. Then, each of the 12 seeds recruited 3 friends who then, in turn, each recruited 3 friends (13 egos per network). This formed a total of 10 networks of 13 LMSM (n=130). Additional information about study recruitment can be found elsewhere.

To be included in the study, participants had to report: 1) cis-male identity, 2) HIV-negative status, 3) sex with a man in the past six months, 4) Hispanic, Latino, or Latinx identification, and 5) behaviors which would qualify them for PrEP prescription based on the CDC PrEP Clinical Practice Guidelines (36). Data were collected from October 2018 to August 2019.

Data collection

Trained bilingual interviewers employed with our community partner obtained written consent from participants. Participants completed the assessment at a community partner site. All study materials were developed in English and Spanish using the back-translation method supported by Marin & Marin (1991). Oral and written data we collected using tablets and a paper-based survey. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap software (Research electronic data capture) hosted at the University of Miami (37, 38).

Measures

Participant/Ego-level Characteristics-

Participants provided individual-level data, including race, PrEP use, number of sexual partners in the past 6 months, and information surrounding their endorsement of familism (39) and self-affirmation of gay identity (14). Familism was measured using the previously validated Mexican American Cultural Values Scale, which consists of 16 items and utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (“Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”) (39). Total possible mean scores could range from 1–5. Although originally developed for Mexican Americans, this scale is widely used for other foreign-born and US-born Hispanic/Latinx subgroups and nationalities (40). Based on previously established correlates of condom use, this study used a modified version of the full scale to examine the effects of three familism subscales: support (6 items), obligations (5 items), and referents (5 items). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for all 16 items in the three familism subscales was 0.98. Due to the high internal consistency among the subscales, a confirmatory factor analysis model was fitted and predicted values for the familism latent variable were extracted for each participant using the R “lavaan” package (41). This new construct was used in our models to account for the effect of familism on condom use.

Gay affirmation was measured using the previously validated Internalized Homonegativity Inventory, a reliable and validated scale used commonly among MSM to measure internalized homophobia and self-affirmation of gay identity (14). The original gay affirmation subscale consists of 7 items utilizing a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree” (14). However, 2 items were removed from the original subscale for this analysis based on feedback from our community partners during pre-testing. The internal consistency for the final 5 items in this subscale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

Situational/Dyadic-level Characteristics -

Participants provided demographic data, and descriptive information of up to 12 sexual partners in the past six months, including anonymous sex partners, using measures developed for this survey. For each sexual partner, participants reported situational/dyadic-level characteristics such as condom use during insertive and receptive anal sex, alcohol use, HIV status disclosure, emotional closeness to each partner, and PrEP use disclosure. Only male alters were included in our analysis.

Emotional closeness was measured using the question, “On a scale of 1 to 5, how close do you feel to this person?” and values could range from “Not at all close” to “Extremely close” with total possible scores ranging from 1 to 5. Reported closeness of ego to alter was group mean centered by ego.

PrEP use disclosure by the alter was measured using the question, “Did this person tell you he was using PrEP?” and the response was binary (Yes/No). PrEP use disclosure by the ego was measured using the question, “Did you ever tell this person that you were using PrEP?” and the response was binary (Yes/No). It is important to note that although the ego may have disclosed PrEP use, this does not necessarily mean the ego was actually using PrEP at that time.

The outcome of interest, consistent condom use during anal sex, was measured by asking each participant, “Please indicate if you had: 1) Active anal sex without a condom refers to when you inserted your penis into another person’s anus without a condom (you were a top); 2) Passive anal sex without a condom refers to when another man penetrated you in the anus with his penis (you were bottom)” for each alter. The occurrence of consistent condom use during anal sex was coded as a binary variable, (1) for consistent condom use and (0) for inconsistent condom use (i.e., ever engaging in condomless sex with that alter).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using R (42). Descriptive statistics of participants (egos) and sexual partners (alters) are displayed in Tables I and II, respectively. For each model, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated. Our models were fitted using a Bernoulli sampling distribution. At level 1, the unit of analysis was the alter characteristic (n=507), and at level 2, the unit of analysis was the ego-level characteristic (n=130). As different random and fixed effects were added to the models discussed below, Likelihood-Ratio Tests (LRT) were used to compare if each subsequent step was a significantly better fit than the previous one. We specified the null model, which reported an intra-class correlation of 0.78, signifying that 78% of the variance in condom use is due to between participants (ego) effects. Our baseline model (Table III: Fixed Model) included the variables of interests for both the sexual partner attributes (level 1) and the participants’ attributes (level 2).

Table I:

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

| PrEP nonuser n (%) | PrEP user n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 38 (30) | 89 (70) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 28.54 (4.4) | 27.71 (3.8) |

| Race | ||

| White | 68 (78) | 23 (66) |

| Multi-racial | 14 (16) | 10 (29) |

| Black/African American | 3 (3) | 2 (6) |

| American Indian or Alaskan | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Asian or Pacific-Islander | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Country of nativity | ||

| US-born | 40 (51) | 21 (55) |

| Foreign-born | 39 (49) | 17 (45) |

| Income | ||

| $24,999 or less | 11 (12) | 5 (13) |

| $25,000 - $34,999 | 34 (38) | 20 (53) |

| $35,000 - $49,999 | 26 (29) | 9 (24) |

| $50,000 or more | 18 (20) | 4 (11) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single or never married | 83 (91) | 29 (76) |

| Married or domestic partner | 8 (9) | 9 (24) |

| Mean sexual partners (SD) | 3.7 (3.0) | 4.4 (2.4) |

| Mean gay affinity score (SD) (alpha = 0.85) | 4.8 (1.0) | 5.2 (1.0) |

| Mean Latino cultural values score | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| Mean religiosity score (alpha = 0.97) (SD) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.4 (N/A) |

| Mean family referent scores (alpha = 0.93) (SD) | 3.2 (N/A) | 3.4 (0.9) |

| Mean family support score (alpha = 0.93) (SD) | 3.3 (N/A) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| Mean family obligation score (alpha = 0.93) (SD) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.8 (0.9) |

| Mean respect score (alpha = 0.97) (SD) | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.6 (0.9) |

Table II:

Descriptive statistics of alters, as perceived by participants

| Alter n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Condomless sex | |

| Used condom during sex | 144 (28) |

| Ever had condomless sex | 363 (72) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 146 (29) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 361 (71) |

| Age | |

| Under 18 years | 1 (0) |

| 18 – 29 years | 299 (59) |

| 30 – 39 years | 141 (28) |

| 40 – 49 years | 23 (5) |

| 50 years or older | 8 (2) |

| No response | 35 (7) |

| Partner PrEP use disclosure | |

| Partner did not disclose PrEP use | 406 (80) |

| Partner disclosed PrEP use | 101 (20) |

| Participant PrEP use disclosure | |

| Participant did not disclose PrEP use | 388 (77) |

| Participant disclosed PrEP use | 119 (23) |

Table III:

Multi-level analyses of condom use during sex

| Fixed Model | Random Slope Model | Final Model with Interactions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds Ratios | CI | p | Odds Ratios | CI | p | Odds Ratios | CI | p |

|

| |||||||||

| (Intercept) Situational/Dyadic-level characteristics | 0.00 | 0.00 – 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 – 0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 – 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Closeness with alter | 0.70 | 0.46 – 1.04 | 0.079 | 0.37 | 0.15 – 0.91 | 0.030 | 0.71 | 0.47 – 1.06 | 0.090 |

| Alter is living with HIV and undetectable | 1.30 | 0.64 – 2.63 | 0.465 | 1.35 | 0.58 – 3.13 | 0.483 | 1.28 | 0.64 – 2.59 | 0.487 |

| Drank alcohol | 0.69 | 0.39 – 1.22 | 0.207 | 0.71 | 0.38 – 1.32 | 0.279 | 0.68 | 0.39 – 1.19 | 0.179 |

| Alter disclosed PrEP use | 1.05 | 0.60 – 1.82 | 0.871 | 0.96 | 0.52 – 1.79 | 0.901 | 1.01 | 0.58 – 1.76 | 0.971 |

| Ego disclosed PrEP use Participant/Ego-level characteristics |

0.49 | 0.23 – 1.04 | 0.063 | 0.45 | 0.18 – 1.09 | 0.078 | 0.42 | 0.20 – 0.91 | 0.028 |

| Race is White | 0.35 | 0.08 – 1.45 | 0.147 | 0.35 | 0.07 – 1.71 | 0.196 | 0.28 | 0.07 – 1.17 | 0.081 |

| Ego is using PrEP | 2.40 | 1.05 – 5.45 | 0.037 | 2.54 | 1.01 – 6.38 | 0.046 | 9.48 | 2.54 – 35.47 | 0.001 |

| Number of sex partners | 1.41 | 1.12 – 1.79 | 0.004 | 1.61 | 1.19 – 2.17 | 0.002 | 1.44 | 1.14 – 1.81 | 0.002 |

| Gay self-affirmation score | 3.34 | 1.37 – 8.18 | 0.008 | 4.24 | 1.49 – 12.04 | 0.007 | 3.04 | 1.30 – 7.14 | 0.011 |

| Familism – latent variable | 3.31 | 1.19 – 9.17 | 0.021 | 3.11 | 1.00 – 9.70 | 0.051 | 4.83 | 1.64 – 14.24 | 0.004 |

| White x Using PrEP | 0.11 | 0.02 – 0.55 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Random Effects | |||||||||

| σ2 | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.29 | ||||||

| τ00 | 5.32 ego | 12.75 ego | 4.52 ego | ||||||

| τ11 | 2.63 ego-alter closeness | ||||||||

| ρ01 | 0.94 ego | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.58 | ||||||

| N | 116 ego | 116 ego | 116 ego | ||||||

| Observations | 428 | 428 | 428 | ||||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.483 / 0.802 | 0.382 / 0.890 | 0.538 / 0.805 | ||||||

Our next step was to identify a model by specifying the random effect of participant’s closeness to the alter, as suggested by prior research (Table III: Random slope model) (6). This model was a better fit than the baseline (χ2(2)=6.68, p<.05), and the closeness effect was significant. The overall variance for this random slope was 2.63, which contributed to an increase in the Conditional R2 (from 0.80 to 0.89) but decreased the Marginal R2 (from 0.48 to 0.38). This meant that the fixed effects in the random slope model explained less of the overall variation in our data.

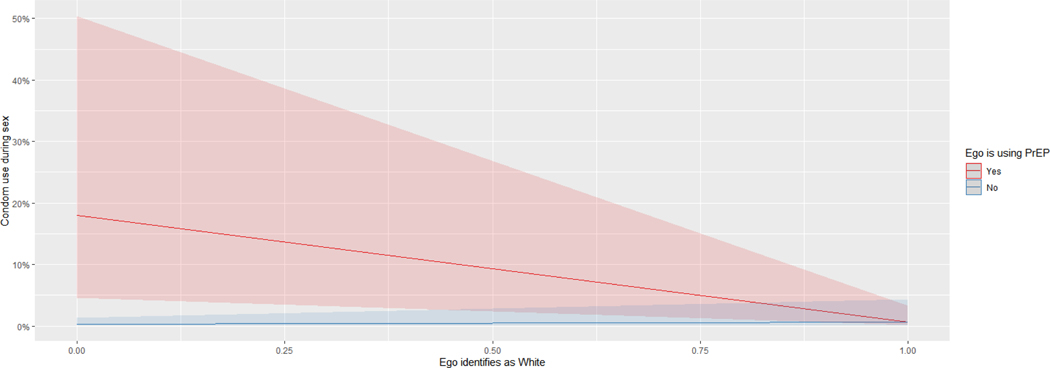

The following interaction effects were then explored in a subsequent model: a) the ego using PrEP and the alter disclosing their PrEP use, and b) both the ego and the alter disclosing PrEP use. This interaction effect did not improve the model. Based on findings from prior research (32, 43), we then included the interaction effect of White race and PrEP use. There was a significant interaction effect between participants identifying as White and being on PrEP. This is represented in Table III: Final Model with Interactions. The final model with interactions was a better fit overall than the baseline fixed model (χ2(1)=8.65, p<.01). The final model failed to converge when the random slope for ego-alter closeness was added; thus, this random effect was dropped. Finally, a simple slope analysis was conducted to further investigate the interaction between ego being on PrEP and identifying as White on the outcome variable of condom use (Figure 2 and Table IV).

Figure 2:

Predicted probability of condom use, based on interaction of White race and PrEP use

Table IV:

Simple slope analysis of condom use, based on interaction of white race and PrEP use

| Slope of White LMSM when ego is using PrEP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | S.E. | z-value | p-value |

| −3.44 | 1.17 | −2.93 | 0.00 |

| Slope of White LMSM when ego is not using PrEP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | S.E. | z-value | p-value |

| 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.37 |

Ethical approval and informed consent

Written consent in either English or Spanish (based on participant preference) was provided and obtained from all participants. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami (IRB # 20180284). All study team members, including our community-based partners, received Human Subjects Research training prior to study commencement. Participants received a $50 gift card as compensation for their time.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics- Thirty percent of participants reported currently using PrEP. Almost all participants self-identified as gay (96%), with few identifying as bisexual (4%). Participants were predominantly White (72%), employed full-time (84%), single or never married (87%), and born in the U.S. (56%). Our sample was heterogenous for Latinx nativity: of those born outside of the U.S. (n=56), 39% reported Cuba nativity, 9% reported Nicaragua nativity, 9% reported Dominican Republic nativity, and the remainder from 5 other Latin American countries.

Alter Characteristics

Egos perceived the majority of their sexual partners to be Latinx (71%) and gay (88%). Except for one female alter, all sexual partners were male—the female alter was excluded from the analysis. As seen in Table II, the majority of sexual partners were reported to be of similar age to the participants (18 to 39 years old).

Hierarchical logistic regression model

The odds of condom use with a sexual partner were 9.48 (95% CI: 2.54, 35.47; p<0.01) times larger with ego’s PrEP use, 1.44 (95% CI: 1.14, 1.81; p<0.01) times larger for every additional sexual partner, 3.04 times larger (95% CI: 1.30, 7.14; p<0.05) for each increment in gay self-affirmation score, and 4.83 (95% CI: 1.64, 14.24; p<0.05) times larger for each point increment in familism score. The odds of condom use with a sexual partner were 0.42 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.91; p<0.05) for ego disclosing PrEP use compared to non-disclosure to this sexual partner during sex. Finally, although there was no effect of White race on condom use, White LMSM who used PrEP were less likely to use condoms compared to Non-White LMSM (OR=0.11; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.55; p<0.05). The interaction effect is further described in Table IV.

Figure 1 demonstrates the multilevel correlation between condom use and PrEP use, stratified by race (only significant effects are shown). The first two models were not significant for ego’s PrEP use disclosure to the alter on condom use; however, this association became significant when controlling for the interaction between White race and ego’s PrEP use. As seen in Figure 2 and Table IV, the interaction between PrEP use and White race is negative and significantly different than zero (β=−3.44; SE=1.17; z-value=−2.93; p<0.05), meaning that a non-White LMSM PrEP user is more likely to use condoms relative to a White LMSM PrEP user. Conversely, for PrEP non-users, racial identity did not yield a significant change in slope (both had low odds of consistent condom use, as expected for PrEP non-users).

Figure 1:

Plot of final multi-level model of correlates with condom use during sex

DISCUSSION

This study used multilevel modeling of egocentric sexual networks to identify correlates of consistent condom use with a sexual partner by LMSM in Miami-Dade County, Florida. We found that PrEP disclosure, PrEP use, number of sexual partners, and higher endorsement of the Latinx cultural belief familism and self-affirmation of gay identity were associated with condom use. The most relevant finding of this study is that PrEP use is positively correlated with consistent condom use; however, when the ego disclosed PrEP use (regardless of whether they were actually using PrEP), consistent condom use decreased. Previous studies have found contradictory conclusions on the risk compensation effects of PrEP use on condom use (20–24).

Our findings suggest that disclosing PrEP use is associated with an increase in condom use. This may be due to underlying sociocultural barriers. There may be a heightened stigma attached to PrEP use, in which individuals who use PrEP are perceived to engage in condomless sex (31, 44–46). In addition, PrEP users have reported being labelled as “promiscuous,” by family and friends for their PrEP use (31). Endorsement or internalization of PrEP-related stigma may cause individuals to promote condom use with partners who use PrEP, believing these individuals may be more likely to have a sexually transmitted infection (31). This finding supports the Social Action Theory which considers condom use in the context of both individual- and situational-level factors. To ensure the dual protection method of both PrEP and condoms, condom use negotiation scripts should also consider incorporating PrEP use disclosure with the ultimate goal of promoting condom use. These negotiation scripts can be developed for specific priority populations using community-based participatory research approaches to ensure that language is stigma-free and tailorable for diverse situations, conversation modes (e.g., online, text, face-to-face), and sexual partnerships (e.g., casual, open relationship). Notably, the alter’s disclosure of PrEP use did not affect condom use. Future studies can examine condom use through a more intensive data collection tool, such as a sex journal which can more accurately capture situational level information during sex including conversations surrounding condom and PrEP use.

Some findings from previous research have suggested that Black and Latinx MSM have higher rates of condomless sex than Whites (47). Another study found that MSM perceived White MSM to have higher rates of condomless sex relative to other racial/ethnic identities (32). Few studies, if any, have looked at condomless sex among Latino racial subgroups. Our study, which focuses on LMSM, found that White LMSM were less likely to use condoms relative to non-White LMSM. When we performed a stratified analysis using a subsample of LMSM who did not use PrEP, condom use did not change by racial identification. Future studies should explore whether due to the disproportionate burden of HIV among Black MSM, White LMSM may feel less at risk for HIV due to their White self-identification despite being an ethnic minority.

Previous studies have found that LMSM who have more sexual partners engage in higher rates of condomless sex (6). However, our study found that as the number of sexual partners increased, LMSM reported more consistent condom use with alters. In addition, of partnered men, MSM in a monogamous relationship are more likely to perceive being protected from HIV relative to men in an open relationship; however, men in an open relationship have higher odds of recent HIV testing than men in a monogamous relationship (48). Future studies should examine how the number of sexual partners and type of sexual partnership (e.g., monogamy, polyamory) influence HIV prevention decision making processes, especially in the context of PrEP use, PrEP use disclosure, and condom use.

We found that familism and gay self-affirmation were positively associated with condom use. LMSM with higher endorsement of familism may feel more responsibility towards the health of their sexual partners. LMSM who feel more positive about their gay identity may feel more comfortable utilizing services such as PrEP navigation and condom dissemination programs at gay-friendly HIV prevention organizations. Our findings on the association between positive endorsement of familism and gay self-affirmation with condom usage suggests that future HIV prevention programs for LMSM should consider the integration of these factors in prevention programming. For example, HIV prevention programs could integrate gay-affirming messaging to help LMSM internalize positive beliefs about being gay, which in turn could lead to increased condom use (49).

Limitations to the present study include recall and social desirability bias due to the self-reported nature of data, lack of generalizability to the broader U.S. Latinx population as Miami-Dade County has a heterogenous and diverse Latinx community, and the use of perceived sociodemographic information (e.g., “street race”) of sexual alters which may not accurately reflect alters’ characteristics. In order to minimize recall and social desirability bias, we used forced-choice items, allowed for guided self-administration of the questionnaire, and employed bilingual LMSM interviewers. Multilevel modeling has strength in elucidating the multiple layers of both ego and dyadic/situational characteristics on the outcome of condom use; however, the utility of multilevel models in the analysis of egocentric network data requires that three conditions be met: 1) the dependent variable must be measured at the alter level; 2) observations at the ego level must be independent of each other; and 3) egocentric sexual networks cannot overlap. As participant recruitment was based on respondent-driven sampling, there is a small chance that conditions 2 and 3 may have been violated. Finally, we did not capture previous PrEP use in our analyses. Participants may have been previously using PrEP but were not using PrEP at the time of the study.

Conclusion

This study examined the association between social network characteristics and condom use among LMSM. A novel finding is that PrEP use was positively associated with condom use; however, the ego’s disclosure of PrEP use decreased odds of condom usage with sexual partners. Notably, the alter’s disclosure of PrEP use did not affect consistent condom use. In addition, we found that increased numbers of sexual partners yielded greater odds of condom usage. Previous studies on PrEP have focused on White MSM so studies such as this, with a Latinx population diverse in race and country of origin, are important (50). Social network methodologies can be used to increase the efficacy of informed personal health choices about PrEP, condoms, and other risk reduction strategies (U=U, negotiated safety) by LMSM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the men who participated in this study; our community partner Latinos Salud and their team members Christian Oliver, Jeremy Johnston, Cooper Wade, and Omar Valdez; and our mentors.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (awards #K99DA041494 PI: Kanamori, R00DA041494 PI: Kanamori), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (award 350 #P30AI050409 Sub-award PI: Kanamori), National Institute of Mental Health (award #P30MH116867 Sub-award PI: Kanamori), and National Institute of Minority Health Disparities (award # F31MD015988 PI: Shrader). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Minority Health Disparities, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Doblecki-Lewis reports investigator-initiated research support from Gilead Sciences. The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents in metropolitan statistical areas—United States and Puerto Rico, 2017. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2019;1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV/AIDS Section, Division of Disease Control and Health Protection, Florida Department of Health. HIV Epidemiology Area 11a. Tallahasee, Florida: Florida Department of Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. Unprotected anal intercourse among immigrant Latino MSM: the role of characteristics of the person and the sexual encounter. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):700–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Predictors of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(4):379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Serostatus disclosure, seroconcordance, partner relationship, and unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2005;17(3):227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo SC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT, Zea MC. Cultural beliefs, partner characteristics, communication, and sexual risk among Latino MSM. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A, Nieves-Rosa L, Dıaz F. Substance use and sexual risḱ behavior: Understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11(4):323–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Reback CJ, Landovitz RJ, Mutchler MG, et al. Individual-level, partnership-level, and sexual event-level predictors of condom use during receptive anal intercourse among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(6):1315–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarama SL, Kennamer JD, Poppen PJ, Hendricks M, Bradford J. Psychosocial, behavioral, and cultural predictors of sexual risk for HIV infection among Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(4):513–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Siconolfi DE, Moeller RW, Figueroa RP, Barton SC, et al. Individual, psychosocial, and social correlates of unprotected anal intercourse in a new generation of young men who have sex with men in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):889–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayfield W. The development of an internalized homonegativity inventory for gay men. J Homosex. 2001;41(2):53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Y-J, Israel T. A computer-based intervention to reduce internalized heterosexism in men. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(3):458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisner SL, O’Cleirigh C, Hendriksen ES, McLain J, Ebin J, Lew K, et al. “40 & Forward”: Preliminary Evaluation of a Group Intervention to Improve Mental Health Outcomes and Address HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Older Gay and Bisexual Men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23(4):523–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cahill S, Valadéz R, Ibarrola S. Community-based HIV prevention interventions that combat anti-gay stigma for men who have sex with men and for transgender women. J Public Health Policy. 2013;34(1):69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Santis JP, Gattamorta KA, Valdes B, Sanchez M, Provencio-Vasquez E. The Relationship of Hispanic Cultural Factors and Sexual Behaviors of Hispanic Men Who Have Sex with Men. Sex Cult. 2019;23(1):292–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. 2002:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogben M, Aral SO. Risk compensation in the age of biomedical prevention. Focus (San Francisco, Calif). 2010;24(4):5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassell MM, Halperin DT, Shelton JD, Stanton D. Risk compensation: the Achilles’ heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ. 2006;332(7541):605–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaño MA, Dombrowski JC, Dasgupta S, Golden MR, Duerr A, Manhart LE, et al. Changes in Sexual Behavior and STI Diagnoses Among MSM Initiating PrEP in a Clinic Setting. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(2):548–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newcomb ME, Moran K, Feinstein BA, Forscher E, Mustanski B. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Use and Condomless Anal Sex: Evidence of Risk Compensation in a Cohort of Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(4):358–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2010;54(5):548–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y-H, Guigayoma J, McFarland W, Snowden JM, Raymond HF. Increases in Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use and Decreases in Condom Use: Behavioral Patterns Among HIV-Negative San Francisco Men Who have Sex with Men, 2004–2017. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1841–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt M, Lea T, Mao L, Kolstee J, Zablotska I, Duck T, et al. Community-level changes in condom use and uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by gay and bisexual men in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia: results of repeated behavioural surveillance in 2013–17. The lancet HIV. 2018;5(8):e448–e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traeger MW, Schroeder SE, Wright EJ, Hellard ME, Cornelisse VJ, Doyle JS, et al. Effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection on sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(5):676–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Bircher AE, Campbell CK, Grisham K, Neilands TB, et al. Attitudes Towards PrEP and Anticipated Condom Use Among Concordant HIV-Negative and HIV-Discordant Male Couples. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(7):408–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus JL, Katz KA, Krakower DS, Calabrese SK. Risk Compensation and Clinical Decision Making - The Case of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):510–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks RA, Landrian A, Nieto O, Fehrenbacher A. Experiences of Anticipated and Enacted Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Stigma Among Latino MSM in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooks CN, Gross AM. Racialized Sexual Risk Perceptions of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in Men Who have Sex with Men. Sexuality & Culture. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrew BJ, Mullan BA, de Wit JBF, Monds LA, Todd J, Kothe EJ. Does the Theory of Planned Behaviour Explain Condom Use Behaviour Among Men Who have Sex with Men? A Meta-analytic Review of the Literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(12):2834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. Am Psychol. 1991;46(9):931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodes SD, McCoy TP. Condom use among immigrant Latino sexual minorities: Multilevel analysis after respondent-driven sampling. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(1):27–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. In: US Public Health Service, editor. Atlanta, GA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inf. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knight G, Gonzales N, Saenz D, Bonds D, Germán M, Deardorf J, et al. The Mexican American Cultural Values scales for Adolescents and Adults. J Early Adolesc. 2010;30(3):444–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corona R, Rodríguez VM, McDonald SE, Velazquez E, Rodríguez A, Fuentes VE. Associations between cultural stressors, cultural values, and Latina/o college students’ mental health. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(1):63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. 2012. 2012;48(2):36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In: Computing RFfS, editor. Vienna, Austria: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Shoptaw S, Landovitz RJ, Javanbakht M, et al. Sexual risk trajectories among MSM in the United States: implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014;65(5):579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, Maksut J. Stigma and Conspiracy Beliefs Related to Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Interest in Using PrEP Among Black and White Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Hayford C, Phillips G, Newcomb ME, Smith JD. Geographic and Individual Associations with PrEP Stigma: Results from the RADAR Cohort of Diverse Young Men Who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3044–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubov A, Galbo P, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. Stigma and Shame Experiences by MSM Who Take PrEP for HIV Prevention: A Qualitative Study. AJMH. 2018;12(6):1843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson EH, Jackson LA, Hinkle Y, Gilbert D, Hoopwood T, Lollis CM, et al. What is the significance of black-white differences in risky sexual behavior? J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(10):745–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stephenson R, White D, Darbes L, Hoff C, Sullivan P. HIV Testing Behaviors and Perceptions of Risk of HIV Infection Among MSM with Main Partners. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(3):553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pérez A, Santamaria EK, Operario D. A systematic review of behavioral interventions to reduce condomless sex and increase HIV testing for Latino MSM. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(5):1261–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Algarin AB, Shrader CH, Bhatt C, Hackworth BT, Cook RL, Ibañez GE. The Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Continuum of Care and Correlates to Initiation Among HIV-Negative Men Recruited at Miami Gay Pride 2018. J Urban Health. 2019;96(6):835–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]