Abstract

Objective: To identify the potential biomarkers for predicting depression in diabetes mellitus using support vector machine to analyze routine biochemical tests and vital signs between two groups: subjects with both diabetes mellitus and depression, and subjects with diabetes mellitus alone.

Methods: Electronic medical records upon admission and biochemical tests and vital signs of 135 patients with both diabetes mellitus and depression and 187 patients with diabetes mellitus alone were identified for this retrospective study. After matching on factors of age and sex, the two groups (n = 72 for each group) were classified by the recursive feature elimination-based support vector machine, of which, the training data, validation data, and testing data were split for ranking the parameters, determine the optimal parameters, and assess classification performance. The biomarkers were identified by 10-fold cross validation.

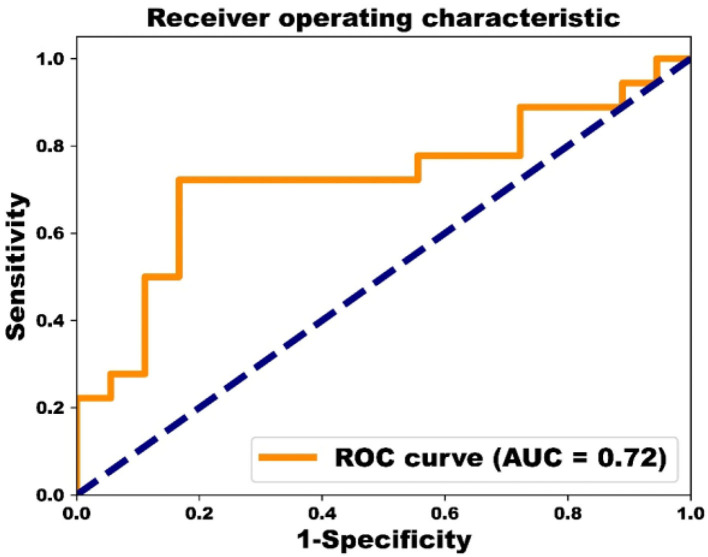

Results: The experimental results identified 8 predictive biomarkers with classification accuracy of 78%. The 8 biomarkers are magnesium, cholesterol, AST/ALT, percentage of monocytes, bilirubin indirect, triglyceride, lactic dehydrogenase, and diastolic blood pressure. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was also adopted with area under the curve being 0.72.

Conclusions: Some biochemical parameters may be potential biomarkers to predict depression among the subjects with diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, depression, support vector machine, biomarkers, machine learning method

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic illness affecting about 347 million people worldwide in 2017, and this number is expected to increase more than half by 2035 (1, 2). The disease will also lead to emotional distress other than physical symptoms and impose psychosocial impacts on life quality, which complicates its management.

Depression and diabetes mellitus are common comorbid conditions (3). A meta-analysis reported that patients with diabetes mellitus more than doubled the odds of developing depression (3). Another study described that depression was highly prevalent, affecting ~26% of the patients with diabetes mellitus (4). In addition, depression was found to be associated with a greater number of complications of diabetes mellitus (5). Furthermore, depression itself is a disabling disease and imposes a significant impact on life quality by undermining physical health (6) and impairing cognitive functions (7). Therefore, it is not surprising that diabetes mellitus comorbidity with depression is associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates, decreased compliance with treatment, poorer functionality, poor glycemic control, and more expenditure on use to health services (7–12). A prospective study involving more than 4,000 patients having diabetes mellitus with comorbidity of depression reported a higher risk of developing macrovascular complications, even when variables such as the type of treatment and the existed history of complications before the study were controlled (13). This highlights the severity of diabetes mellitus in comorbidity with depression and the need to treat both conditions concurrently.

Comorbid depression in diabetes mellitus might be considered not as the result of mental problem only, but more important, as an early sign of a multi-systemic disorder. Thus, medical monitoring is an important component of case assessment. The diagnosis of depression mainly depends on doctors' clinical experience and scale. The lack of objective indicators, the strong subjective consciousness of doctors and patients, and the avoidance or denial in some symptoms due to patients' insufficient understanding of the disease interfere with the accuracy of scale score; and this may affect the correct diagnosis of the disease (14–16). Therefore, it is particularly important to identify objective indicators of depression diagnosis and establish scientific diagnostic methods. Nonetheless, very few approaches have been proposed to facilitate early prediction depression in patients having diabetes mellitus because objective indicators of laboratory examinations are rare.

Recently, machine learning algorithms have been widely used in the medical sciences. It was reported that machine learning algorithms in combination with smartphone-based data will be a new approach to classify affective states accurately in bipolar disorder (17). In addition, machine learning methods may be used to predict treatment effect of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (18), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (19), and clozapine (20); or to help diagnostic clarification (21). According to Kim et al., comprehensive machine-learning methods that adopt supervised classification and appropriate feature selection methods that have interaction with the classifier show particular advantages in predicting complicated disorders with multi-facet etiology such as depression (22). Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a method of machine learning and is of great significance in accurately identifying depression among patients with diabetes mellitus in clinical practice. This method provides insights for understanding the underlying pathological mechanisms of depression.

Previous studies have reported a high accuracy of over 80% in differentiating patients with depression from healthy controls, using machine learning methods to analyze heart rate variability (HRV) and/or protein markers (22, 23). Nevertheless, the existing extraction procedures of parameters are usually complex. For example, Kuang et al. (23) need to examine the 64 features of HRV in the Ewing test including the different states—resting, valsalva, deep breathing, and standing states. By contrast, our study was much simpler in that only easy-to-obtain routine biochemical tests and vital signs of patients were needed. By SVM, the best executing classification system can be set up with a small number of parameters that are selected from a variety of biochemical tests and vital signs.

To address this need, we proposed using SVM to identify potential prediction biomarkers for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Materials and Methods

Data Acquisition

Biochemical tests and vital signs were obtained from electronic medical records of admissions in West China Hospital of Sichuan University between January 1, 2011 and October 31, 2016. A total of 322 patients were divided into two groups: 135 with both diabetes mellitus and depression (comorbidity group), and 187 with diabetes mellitus alone (DM group). Specifically, the DM group was diagnosed using the ICD - 10 categories E10.x - E14.x, and the depression in comorbidity group was diagnosed using the ICD - 10 categories F32.x and F33.x. To avoid confounding, patients with other diseases or of non-Han ethnicities were excluded. Each department had different biochemical parameters checked as appropriate, and we analyzed the same biochemical parameters for both groups (Table 1). Written informed consent had been obtained from all patients, and the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sichuan University approved this study.

Table 1.

The 52 biochemical tests and 5 vital signs.

| 52 biochemical tests and 5 vital signs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red blood count (RBC) | 14 | Acidophil absolute value | 27 | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) | 40 | Glutamyl transpeptidase |

| 2 | Hemoglobin (HGB) | 15 | Basophilic cell absolute value | 28 | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) | 41 | Blood urea nitrogen |

| 3 | Mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | 16 | Creatine kinase (CK) | 29 | Total protein | 42 | Sodium |

| 4 | Platelet count (PLT) | 17 | Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) | 30 | Albumin (A) | 43 | Potassium |

| 5 | White blood cell count (WBC) | 18 | Total bilirubin | 31 | Globulin (G) | 44 | Chlorine |

| 6 | Percentage of neutrophils | 19 | Direct bilirubin | 32 | A/G | 45 | Anion gap |

| 7 | Percentage of lymphocytes | 20 | Bilirubin indirect | 33 | Creatinine | 46 | Serum cyscatin-c |

| 8 | Percentage of monocytes | 21 | Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase | 34 | Uric acid | 47 | Hydroxybutyric acid |

| 9 | Eosinophil percentage | 22 | Triglyceride | 35 | Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 48 | Urine RBC |

| 10 | Basophil percentage | 23 | Cholesterol | 36 | Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 49 | Urine WBC |

| 11 | Absolute value of neutrophils | 24 | Calcium | 37 | AST/ALT | 50 | Urine conductivity |

| 12 | Absolute value of the lymphocyte | 25 | Magnesium | 38 | Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 51 | Urine specific gravity |

| 13 | Absolute value of the monocytes | 26 | Phosphorus | 39 | Glucose | 52 | Urine potential of hydrogen (U-PH) |

| 1 | Body temperature | 3 | Respiration | 5 | Diastolic blood pressure | ||

| 2 | Pulse | 4 | Systolic blood pressure | ||||

Data Processing

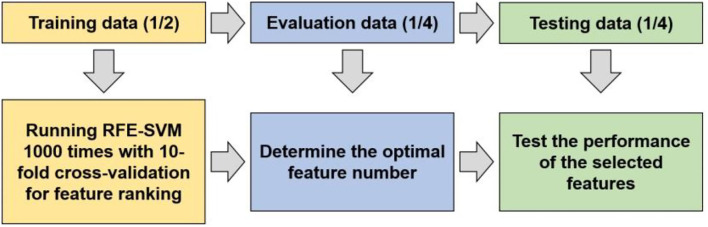

To detect whether biochemical tests and vital signs can function as markers for predicting depression in diabetes mellitus, a RFE-SVM algorithm was adopted to identify the markers and assess the classification performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flowchart of data processing.

Before applying the machine learning method to identify predictive markers, propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed because age and sex differed significantly between the DM and comorbidity groups. After the matching analysis, the experimental data were split into training data, validation data, and testing data with the proportion of 1/2, 1/4, 1/4 to obtain feature ranking, determine the optimal features, and assess the classification performance. Specifically, the implementation of the machine learning can be summarized as follows:

① Determine the feature ranking by recursive feature elimination-based SVM on the training data. The experiments were repeated 1,000 times with 10-fold cross validation.

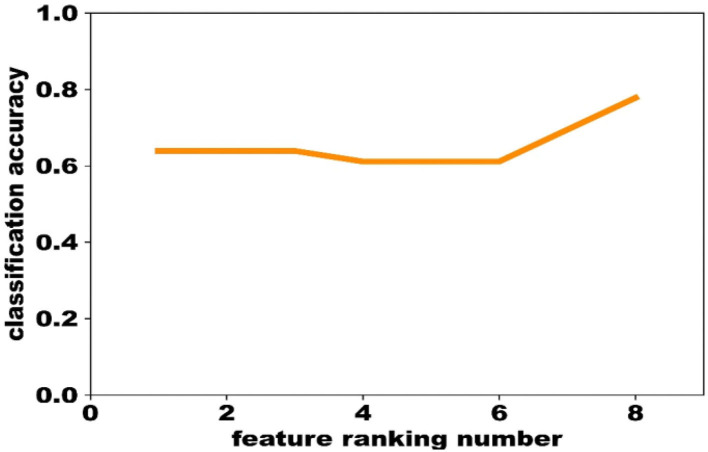

② Train a SVM classification model on the training data using the liblinear toolbox, and determine the most predictive features using the evaluation data based on the feature ranking obtained above. The feature that ranked No. 1 was first used to optimize the model, and the performance was evaluated by the validation data. Then, the feature that ranked No. 2 was combined to optimize the model and to compare the performance with the previous one. If the performance of the latter classifier was worse than the former, the feature that ranked No. 2 would be removed. In this way, only the features that could increase the classification accuracy were remained, and finally we obtained 8 biomarkers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The procedure of feature selection on the evaluation data.

③ Train the classification model on the training data with the selected 8 biomarkers, and assess the performance on the testing data by the measurements of accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0. Two-sample t-test and chi-squared test were used for comparison between groups. Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed for matching age and sex. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for both tests.

Results

Table 1 showed analyzed 52 biochemical tests and 5 vital signs for both groups, including red blood count (RBC), acidophil absolute value, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), glutamyl transpeptidase, hemoglobin (HGB), basophilic cell absolute value, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), blood urea nitrogen, mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), creatine kinase (CK), total protein, sodium, platelet count (PLT), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), albumin (A), potassium, white blood cell count (WBC), total bilirubin, globulin (G), chlorine, percentage of neutrophils, direct bilirubin, A/G, anion gap, percentage of lymphocytes, bilirubin indirect, creatinine, serum cyscatin-c, percentage of monocytes, hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, uric acid, hydroxybutyric acid, eosinophil percentage, triglyceride, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), urine RBC, basophil percentage, cholesterol, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), urine WBC, absolute value of neutrophils, calcium, AST/ALT, urine conductivity, absolute value of the lymphocyte, magnesium, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), urine specific gravity, absolute value of the monocytes, phosphorus, glucose, urine potential of hydrogen (U-PH), body temperature, respiration, diastolic blood pressure, Pulse, and systolic blood pressure.

In this retrospective study, medical records upon admission of 322 patients were selected. After the matching analysis, there are 72 samples in the DM group and the comorbidity group, respectively. Demographic characteristics of the DM group (n = 72) and the comorbidity group (n = 72, F32.x: 106 and F33.x: 29) were summarized (Table 2). The mean (SD) age of subjects was 56.13 (7.98) years in the DM group and 54.93 (7.62) years in the comorbidity group. There were not different between two groups on age and sex (male: 31, respectively). Eight features were computed in 10-fold cross-validation experiments, repeated 1,000 times with SVM, including magnesium, cholesterol, AST/ALT, percentage of monocytes, bilirubin indirect, triglyceride, lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), and diastolic blood pressure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics and biomarkers of experimental results of 144 diabetes mellitus patients with and without depression.

| DM group (n = 72) | Comorbidity group (n = 72) | Statistics | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male (n = 31) | Male (n = 31) | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | 56.13 ± 7.98 | 54.93 ± 7.62 | 0.92 | 0.36 |

| Magnesium | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.12 | −2.86 | 0.005 |

| Cholesterol | 4.25 ± 0.57 | 4.71 ± 0.95 | −3.57 | <0.001 |

| AST/ALT | 1.03 ± 0.38 | 0.97 ± 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| Percentage of monocytes | 5.38 ± 1.58 | 5.80 ± 1.46 | −1.65 | 0.10 |

| Bilirubin indirect | 7.31 ± 2.94 | 8.54 ± 4.59 | −1.92 | 0.06 |

| Triglyceride | 1.40 ± 0.62 | 1.82 ± 1.43 | −2.30 | 0.02 |

| lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) | 165.63 ± 27.78 | 155.07 ± 47.87 | 1.62 | 0.11 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 77.81 ± 10.77 | 78.87 ± 9.32 | −0.63 | 0.53 |

The performance of classification of both groups reached 83% for sensitivity, 72% for specificity, 78% for accuracy, and 0.72 for AUC based on ROC analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ROC curve analysis with AUC value.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we found 8 important depression biomarkers using SVM. These biomarkers are magnesium, cholesterol, AST/ALT, percentage of monocytes, bilirubin indirect, triglyceride, lactic dehydrogenase, and diastolic blood pressure, which differentiate depression in patients with diabetes mellitus at an overall classification accuracy of 78%. Eight identified factors imply that modulation of the inflammatory, immune, energy metabolism, and lipid metabolism pathways were mainly involved in the pathophysiology of depression in patients with diabetes mellitus.

We found four biomarkers involved in inflammatory and immune pathway including magnesium, AST/ALT, percentage of monocytes, and bilirubin indirect. Depression often comorbid with diabetes, metabolic disorders and other diseases, and is associated with inflammatory and oxidative stress (24). Type 2 diabetes usually begins with insulin resistance, and a relationship between depression and insulin resistance also exists (25). Diabetes can cause a rise in blood sugar and insulin levels and has an effect on inflammation that may contribute to depression. Recent studies have shown that oxidative stress may enhance induction of HO-1 expression, which may result in insulin resistance and insufficiency (26, 27). It is clear that increased oxidative stress may lead to insulin resistance and impose an impact on insulin secretion in patients having depressive disorder (27). One study demonstrated that reducing inflammation through non-drug treatments such as psychological interventions, physical exercises, and meditation can play a role in preventing depression (28). Magnesium has received great concern over its potential role in the pathophysiology of depression (29–31). Many studies support the hypothesis that inflammatory cytokines are important factors in the pathogenesis of MDD (32). Auffray et al. suggested that monocytes mediate fundamental regulatory and effector functions in immune inflammatory responses (33). Previous study have indicated that MDD patients with elevated serum TNF-α and IL-1β levels display marked alterations in circulating monocytes and exhibit a systemic proinflammatory state compared to healthy controls (34). Additionally, studies have shown that the percentage of monocytes decreased by imipramine treatment can be enhanced by stress exposure (35). New evidence shows that antidepressant treatment can reduce inflammation and improve mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with depression (36, 37). Also, studies have indicated that increased ALT levels were an independent predictor of depression onset (38).

We also found one biomarker potentially related to energy metabolism. The biomarker is lactic dehydrogenase. It is responsible for the conversion of lactic acid to pyruvic acid, an important step in the production of cellular energy (39). Kato et al. found that healthy nurses' depressive symptoms shown on CES-D under the stressful conditions were significantly negatively correlations with lactate dehydrogenase activities (r = −0.29, p = 0.0065) (40). We observed that patients with both diabetes mellitus and depression had lower concentrations of lactic dehydrogenase compared to those with diabetes alone. In another study, Ivana Perić et al. showed an increase in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels after Tianeptine treatment in stressed rats (41). After antidepressant treatment, LDH level is increased and depression was alleviated, suggesting that LDH may be related to the pathological basis of depression (41). Additionally, we found some other biomarkers that may be related to lipid metabolism, including cholesterol and triglyceride. Clinical and experimental evidence has suggested that plasma lipids might be an important factor in the pathophysiological mechanisms related to depression (42). Higher level of cholesterol was observed in patients with depression than in controls (27, 43). In agreement with this finding, increased levels of cholesterol were found to be associated with comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and depression in our study. A recent study has analyzed 230 metabolic markers and reported a clear and unique profile of circulating lipid metabolites related to depression (44). Bot et al. has found that depression is associated with higher triglyceride (44), which is consistent with our results in this study. A previous study has shown that activation of the proinflammatory response results in a decrease in HDL cholesterol and phospholipids, as well as an increase in TG mediated by compensatory production and accumulation of phospholipid-rich VLDL (45).

Depression is common in patients with diabetes, and there is a bidirectional association between diabetes and depression. Many mechanisms are considered to be involved in the link between depression and diabetes, including HPA axis dysregulation, immune and inflammatory mechanisms, brain insulin resistance, circadian rhythm dysregulation, shared genetic factors and more (46). For example, the immune system has also been implicated in the co-occurrence of depression and diabetes. Monocytes in the peripheral blood are the most important cells in the innate system, which produce cytokines involved in the development of inflammation in patients with diabetes (47). Previous study have shown that imbalances in Mg2+ status can increase insulin resistance, inhibit translocation of glucose transporter type 4, induce oxidative stress, affect lipid metabolism, and impair the antioxidant system of endothelial cells, thus promoting the progression of DM (48). Additionally, lactate metabolic pathways are important for understanding the pathogenesis of diabetes. It has been reported that pyruvate is reduced to lactate in the cytoplasm by lactate dehydrogenase without oxygen consumption, and excess lactate is generated in diabetes (49). Hildrum et al. found that patients with anxiety and depression had higher diastolic blood pressure at 11-year follow-up in these populations, but presented lower diastolic blood pressure at 22-year follow-up, which may be related to antidepressants (50). Trento found that self-management education improved blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes (51). These factors are also present in patients with depression.

Changes in triglyceride, AST, ALT, bilirubin indirect, lactic dehydrogenase, and cholesterol etc. in blood are not specific to depression and may be present in other psychiatric disorders such as eating disorders (52), schizophrenia (53, 54), and bipolar disorder (55, 56). Researchers suggested that a single biomarker often lacks in sensitivity and specificity (27) and thus may not well-distinguish depression from other diseases. Monitoring changes in multiple factor levels will provide a more comprehensive and accurate assessment, which can help us better understand the disease status and characteristics of specific diseases. Although the model of multiple biomarkers is more conducive for the diagnosis of diseases, it is usually used in the diagnosis of cancer instead of nervous system diseases (57, 58). Our study is advantageous in that laboratory biochemical indexes are routine examinations in clinical settings, which could be obtained with minimal invasiveness, maximal convenience, and low cost, thus having a great potential for wider clinical access and more efficient population screening. Because the biochemical tests of the two groups were not identical, the different ones were deleted. The lack of biochemical tests as variables in SVM learning affected accuracy, which is one limitation of the present study. Second, the parameters chosen retrospectively instead of consecutively were inadequate and included only those that were clinically applicable. This may have caused an enrollment bias and an erroneous classification by the algorithm. This is one of the major methodological limitations of the present study, which should be remedied in future investigations using a prospective and consecutive design.

In conclusion (1) SVM can facilitate clinical diagnosis of depression in patients with diabetes mellitus using commonly available laboratory parameters. (2) Eight potential biomarkers were identified for depression diagnosis in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the case report. The Institutional Ethics Committee of Sichuan University approved this study. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

XS, QZ, and XM participated in study design, data analysis, accrual of study participants, and manuscript writing and review. RZ and MW participated in data analysis and critical revisions for important intellectual content. WD, QW, WG, and TL review of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81671344).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dongtao Lin of Sichuan University for copyediting this manuscript and all individuals who have participated in this study.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. (1998) 15:539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markle-Reid M, Ploeg J, Fraser KD, Fisher KA, Bartholomew A, Griffith LE, et al. Community program improves quality of life and self-management in older adults with diabetes mellitus and comorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2017) 66:263–73. 10.1111/jgs.15173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tareen RS, Tareen K. Psychosocial aspects of diabetes management: dilemma of diabetes distress. Transl Pediatr. (2017) 6:383–96. 10.21037/tp.2017.10.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2010) 87:302–12. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. (2001) 63:619–30. 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 2013:Cd004366. 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammar A, Ardal G. Cognitive functioning in major depression–a summary. Front Hum Neurosci. (2009) 3:26. 10.3389/neuro.09.026.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayakody K, Gunadasa S, Hosker C. Exercise for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. (2014) 48:187–96. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2008) 2008:Cd005381. 10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. (2005) 19:113–22. 10.1016/S1056-8727(04)00004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schram MT, Baan CA, Pouwer F. Depression and quality of life in patients with diabetes: a systematic review from the European depression in diabetes (EDID) research consortium. Curr Diabetes Rev. (2009) 5:112–9. 10.2174/157339909788166828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin EH, Heckbert SR, Rutter CM, Katon WJ, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Depression and increased mortality in diabetes: unexpected causes of death. Ann Fam Med. (2009) 7:414–21. 10.1370/afm.998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knol MJ, Twisk JW, Beekman AT, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ, Pouwer F. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. (2006) 49:837–45. 10.1007/s00125-006-0159-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummins N, Scherer S, Krajewski J, Schnieder S, Epps J, Quatieri TF. A review of depression and suicide risk assessment using speech analysis. Speech Commun. (2015) 71:10–49. 10.1016/j.specom.2015.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balsters MJH, Krahmer EJ, Swerts MGJ, Vingerhoets AJJM. Verbal and nonverbal correlates for depression: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rev. (2012) 8:2966. 10.2174/157340012800792966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto JV, Passos IC, Gomes F, Reckziegel R, Kapczinski F, Mwangi B, et al. Peripheral biomarker signatures of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A machine learning approach. Schizophr Res. (2017) 188:182–4. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faurholt-Jepsen M, Busk J, Frost M, Vinberg M, Christensen EM, Winther O, et al. Voice analysis as an objective state marker in bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e856. 10.1038/tp.2016.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Waarde JA, Scholte HS, van Oudheusden LJ, Verwey B, Denys D, van Wingen GA. A functional MRI marker may predict the outcome of electroconvulsive therapy in severe and treatment-resistant depression. Mol Psychiatry. (2015) 20:609–14. 10.1038/mp.2014.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn T, Kircher T, Straube B, Wittchen HU, Konrad C, Strohle A, et al. Predicting treatment response to cognitive behavioral therapy in panic disorder with agoraphobia by integrating local neural information. JAMA Psychiatry. (2015) 72:68–74. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khodayari-Rostamabad A, Hasey GM, Maccrimmon DJ, Reilly JP, de Bruin H. A pilot study to determine whether machine learning methodologies using pre-treatment electroencephalography can predict the symptomatic response to clozapine therapy. Clin Neurophysiol. (2010) 121:1998–2006. 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khodayari-Rostamabad A, Reilly JP, Hasey G, Debruin H, Maccrimmon D. Diagnosis of psychiatric disorders using EEG data and employing a statistical decision model. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. (2010) 2010:4006–9. 10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim EY, Lee MY, Kim SH, Ha K, Kim KP, Ahn YM. Diagnosis of major depressive disorder by combining multimodal information from heart rate dynamics and serum proteomics using machine-learning algorithm. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 76:65–71. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuang D, Yang R, Chen X, Lao G, Wu F, Huang X, et al. Depression recognition according to heart rate variability using Bayesian Networks. J Psychiatr Res. (2017) 95:282–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrickx H, McEwen BS, Ouderaa F. Metabolism, mood and cognition in aging: the importance of lifestyle and dietary intervention. Neurobiol Aging. (2005) 26(Suppl. 1):1–5. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiuhua S, Bergquist-Beringer S, Sousa VD. Major depressive disorder and insulin resistance in nondiabetic young adults in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2002. Biol Res Nurs. (2011) 13:175–81. 10.1177/1099800410384501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keane KN, Cruzat VF, Carlessi R, de Bittencourt PIH, Newsholme P. Molecular events linking oxidative stress and inflammation to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Oxidat Med Cell Longevity. (2015) 2015:1–15. 10.1155/2015/181643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng YF, Xiang Y, Wei YS. The significance of routine biochemical markers in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:34402. 10.1038/srep34402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwin MR, Piber D. Insomnia and inflammation: a two hit model of depression risk and prevention. World Psychiatry. (2018) 17:359–61. 10.1002/wps.20556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linder J, Brismar K, Beck-Friis J, Saaf J, Wetterberg L. Calcium and magnesium concentrations in affective disorder: difference between plasma and serum in relation to symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1989) 80:527–37. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cade JF. A significant elevation of plasma magnesium levels in schizophrenia and depressive states. Med J Aust. (1964) 1:195–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1964.tb133950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryszewska-Pokrasniewicz B, Mach A, Skalski M, Januszko P, Wawrzyniak ZM, Poleszak E, et al. Effects of magnesium supplementation on unipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study and review of the importance of dosing and magnesium status in the therapeutic response. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1014. 10.3390/nu10081014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotrich FE. Inflammatory cytokine-associated depression. Brain Res. (2015) 1617:113–25. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. (2009) 27:669–92. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez-Mon MA, Gomez AM, Orozco A, Lahera G, Sosa MD, Diaz D, et al. Abnormal distribution and function of circulating monocytes and enhanced bacterial translocation in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:812. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez K, Sheridan JF. Antidepressant imipramine diminishes stress-induced inflammation in the periphery and central nervous system and related anxiety- and depressive- like behaviors. Brain Behav Immun. (2016) 57:293–303. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortmann CF, Reus GZ, Ignacio ZM, Abelaira HM, Titus SE, de Carvalho P, et al. Enriched flavonoid fraction from cecropia pachystachya trecul leaves exerts antidepressant-like behavior and protects brain against oxidative stress in rats subjected to chronic mild stress. Neurotox Res. (2016) 29:469–83. 10.1007/s12640-016-9596-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SY, Lee SJ, Han C, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU. Oxidative/nitrosative stress and antidepressants: targets for novel antidepressants. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 46:224–35. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelber-Sagi S, Toker S, Armon G, Melamed S, Berliner S, Shapira I, et al. Elevated alanine aminotransferase independently predicts new onset of depression in employees undergoing health screening examinations. Psychol Med. (2013) 43:2603–13. 10.1017/S0033291713000500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xixi Z, Qian P, Wang B. Electrolyzing lactic acid in situ in fermentation broth to produce pyruvic acid in electrolysis cell. Appl Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2019) 103:4045–52. 10.1007/s00253-019-09793-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato A, Sakakibara H, Tsuboi H, Tatsumi A, Akimoto M, Shimoi K, et al. Depressive symptoms of female nursing staff working in stressful environments and their association with serum creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase - a preliminary study. Biopsychosoc Med. (2014) 8:21. 10.1186/1751-0759-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peric I, Costina V, Findeisen P, Gass P, Filipovic D. Tianeptine enhances energy-related processes in the hippocampal non-synaptic mitochondria in a rat model of depression. Neuroscience. (2020) 451:111–25. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.09.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang C, Yang Y, Zhu DM, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Zhang B, et al. Neural correlates of the association between depression and high density lipoprotein cholesterol change. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 130:9–18. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin JY, Suls J, Martin R. Are cholesterol and depression inversely related? A meta-analysis of the association between two cardiac risk factors. Ann Behav Med. (2008) 36:33–43. 10.1007/s12160-008-9045-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bot M, Milaneschi Y, Al-Shehri T, Amin N, Garmaeva S, Onderwater GLJ, et al. Metabolomics profile in depression: a pooled analysis of 230 metabolic markers in 5283 cases with depression and 10,145 controls. Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 87:409–18. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteve E, Ricart W, Fernandez-Real JM. Dyslipidemia and inflammation: an evolutionary conserved mechanism. Clin Nutr. (2005) 24:16–31. 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee N, Chaturvedi SK. Depressive symptoms and disorders in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2019) 32:416–21. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angelo AGS, Neves CTC, Lobo TF, Godoy RVC, Ono E, Mattar R, et al. Monocyte profile in peripheral blood of gestational diabetes mellitus patients. Cytokine. (2018) 107:79–84. 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng J, Wang H, Jing Z, Wang Y, Cheng Y, Wang W, et al. Role of magnesium in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2020) 196:74–85. 10.1007/s12011-019-01922-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adeva-Andany M, Lopez-Ojen M, Funcasta-Calderon R, Ameneiros-Rodriguez E, Donapetry-Garcia C, Vila-Altesor M, et al. Comprehensive review on lactate metabolism in human health. Mitochondrion. (2014) 17:76–100. 10.1016/j.mito.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hildrum B, Romild U, Holmen J. Anxiety and depression lowers blood pressure: 22-year follow-up of the population based HUNT study, Norway. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:601. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trento M, Fornengo P, Amione C, Salassa M, Barutta F, Gruden G, et al. Self-management education may improve blood pressure in people with type 2 diabetes. A randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 30:1973–9. 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nova E, Lopez-Vidriero I, Varela P, Casas J, Marcos A. Evolution of serum biochemical indicators in anorexia nervosa patients: a 1-year follow-up study. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2008) 21:23–30. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skibinska M, Kapelski P, Rajewska-Rager A, Szczepankiewicz A, Narozna B, Duda J, et al. Correlation of metabolic parameters, neurotrophin-3, and neurotrophin-4 serum levels in women with schizophrenia and first-onset depression. Nord J Psychiatry. (2019) 2019:1–8. 10.1080/08039488.2018.1563213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng XD, Cao X, Li T, Li JP. Creatine kinase (CK) and its association with aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2018) 197:478–83. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu Q, Wang C, Liu F, He J, Wang F, Wang W, et al. High serum levels of FGF21 are decreased in bipolar mania patients during psychotropic medication treatment and are associated with increased metabolism disturbance. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 272:643–8. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, Chen H, Feng J, Zhang L, Li J, Li R, et al. Association between hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome in patients suffering from bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:390. 10.1186/s12888-018-1952-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu CS, Pinsky PF, Cramer DW, Ransohoff DF, Hartge P, Pfeiffer RM, et al. A framework for evaluating biomarkers for early detection: validation of biomarker panels for ovarian cancer. Cancer Prev Res. (2011) 4:375–83. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunn BK, Jegalian K, Greenwald P. Biomarkers for early detection and as surrogate endpoints in cancer prevention trials: issues and opportunities. Recent Results Cancer Res. (2011) 188:21–47. 10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.