Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) mastitis is one of the most difficult diseases to treat in lactating dairy cows worldwide. S. aureus with different lineages leads to different host immune responses. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are reported to be widely involved in the progress of inflammation. However, no research has identified stable lncRNAs among different S. aureus strain infections. In addition, folic acid (FA) can effectively reduce inflammation, and whether the inflammatory response caused by S. aureus can be reduced by FA remains to be explored.

Methods

lncRNA transcripts were identified from Holstein mammary gland tissues infected with different concentrations of S. aureus (in vivo) and mammary alveolar cells (Mac-T cells, in vitro) challenged with different S. aureus strains. Differentially expressed (DE) lncRNAs were evaluated, and stable DE lncRNAs were identified in vivo and in vitro. On the basis of the gene sequence conservation and function conservation across species, key lncRNAs with the function of potentially immune regulation were retained for further analysis. The function of FA on inflammation induced by S. aureus challenge was also investigated. Then, the association analysis between these keys lncRNA transcripts and hematological parameters (HPs) was carried out. Lastly, the knockdown and overexpression of the important lncRNA were performed to validate the gene function on the regulation of cell immune response.

Results

Linear regression analysis showed a significant correlation between the expression levels of lncRNA shared by mammary tissue and Mac-T cells (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.3517). lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 could be regarded as stable markers associated with bovine S. aureus mastitis. Several HPs could be influenced by SNPs around lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1. The results of gene function validation showed PRANCR regulates the mRNA expression of SELPLG and ITGB2 within the S. aureus infection pathway and the Mac-T cells apoptosis. In addition, FA regulated the expression change of DE lncRNA involved in toxin metabolism and inflammation to fight against S. aureus infection.

Conclusions

The remarkable association between SNPs around these two lncRNAs and partial HP indicates the potentially important role of PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 in immune regulation. Stable DE lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 can be regarded as potential targets for the prevention of bovine S. aureus mastitis. FA supplementation can reduce the negative effect of S. aureus challenge by regulating the expression of lncRNAs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40104-021-00639-2.

Keywords: Bovine mastitis, Folic acid, Long non-coding RNA, Mac-T cells, Mammary gland, Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

Bovine mastitis is a tricky problem in dairy farming and leads to the decline of milk quality and remarkable economic losses worldwide [1]. Pathogen invasion to mammary gland is the main cause of this complex disease [2]. Several microorganisms, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), induce bovine mastitis. Mastitis induced by the contagious pathogen S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is still hard to cure [3]. The host’s inflammatory response is dependent on the different lineages of S. aureus and the immune level of the mammary gland tissue [4–7].

Identifying stable molecular markers induced by different S. aureus strains can provide an effective broad-spectrum approach to the treatment and prevention of bovine S. aureus mastitis. Several stable markers of differentially expressed (DE) mRNAs involved in S. aureus infection, such as genes SETD2, CYP1A1 and SSB1, have been identified [8]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are the noncoding transcripts with length longer than 200 nucleotides, widely regulate mRNA expression at the transcription level, and influence the progress of complex diseases [9, 10]. However, stable DE lncRNAs among different S. aureus strain infections are yet to be investigated.

The bovine mammary gland tissue (in vivo) and mammary gland alveolar cells (Mac-T cells, in vitro) are the common experimental materials for the study of S. aureus mastitis [8, 11]. Previous results indicated partially inconsistent bovine immune response between in vivo and in vitro results [11, 12]. Thus, under the condition of S. aureus infection, the combined analysis of lncRNA regulation in vivo and in vitro is also necessary for the identification of reliable lncRNA markers. Folic acid (FA), as a micronutrient, plays effective roles in reducing inflammation and mastitis incidence, and improving milk production [4, 5, 13, 14]. The remarkable effect of FA on the lncRNA expression has been widely reported [15–17]. Whether FA can regulate the inflammation induced by S. aureus infection by influencing lncRNA remains unknown.

In this study, S. aureus strains with different lineages are chosen to identify the stable DE lncRNAs of bovine S. aureus mastitis in vivo and in vitro. The potential interaction network among host (lncRNA and mRNA), S. aureus infection, and FA treatment is characterized.

Material and methods

Ethics statement

All procedures involving experimental animals were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of China Agricultural University, Beijing, China. All efforts were made to minimize the suffering and discomfort of the experimental animals.

S. aureus strains

Four S. aureus strains were used in this study. One strain was used for the individual study (in vivo), and the three other strains were used for the cell study (in vitro). All four strains were isolated from the fresh milk of Chinese Holstein cows and stored at − 80 °C. Details are shown in our previous report [18]. The strain used in the individual study was isolated from a Chinese Holstein cow with mastitis. The two strains of S. aureus used in the cell experiment were isolated separately from cow with low milk somatic cell counts (Strain L) and cow with mastitis symptoms (Strain M). The strain of MRSA used in the cell experiment was isolated from a cow with mastitis (Strain MM).

Experimental design and samples information

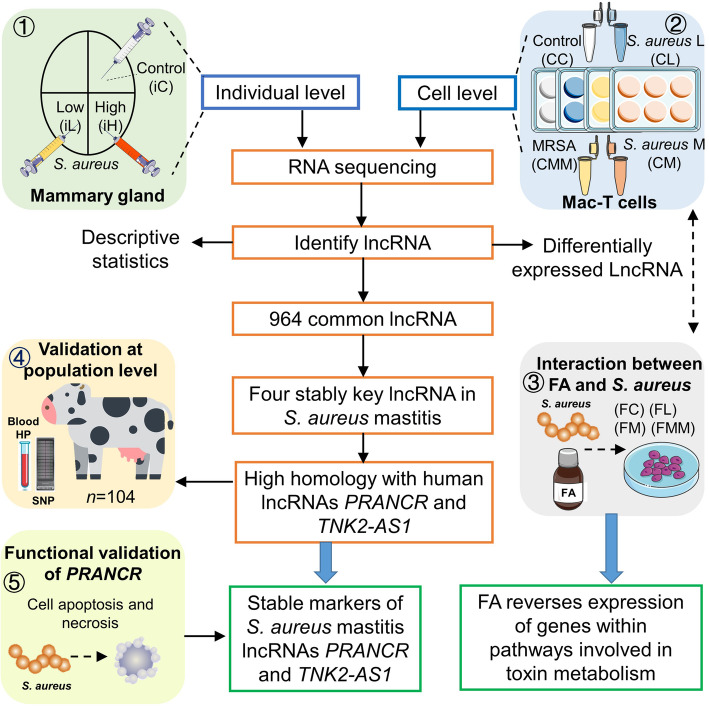

Five related experiments were designed and conducted in this study to uncover the interplays among host lncRNA, S. aureus infection, and FA treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of this study. Five related experiments were designed. The bovine mammary gland was challenged with different concentrations of S. aureus (in vivo). Bovine mammary gland alveolar cells (Mac-T cells) were challenged with different S. aureus strains (in vitro). Mac-T cells were subjected to folic acid treatment and S. aureus challenge, and the association between SNPs around key long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and hematological parameters (HP) was tested at the population level. Finally, the function of lncRNA was validated by gene knockdown and overexpression. S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; FA: folic acid; PRANCR: progenitor renewal associated non-coding RNA; TNK2-AS1: TNK2 antisense RNA 1. iC: mammary gland challenged with saline; iL: mammary challenged with low concentration of S. aureus; iH: mammary challenged with high concentration of S. aureus. CC: cells control; CL: cells challenged with Strain L; CM: cells challenged with Strain M; CMM: cells challenged with Strain MM; FC: cells treated by FA; FL: cells treated by FA and challenged with Strain L; FM: cells treated by FA and challenged with Strain M; FMM: cells treated by FA and challenged with Strain MM

The first experiment was conducted in vivo. Two healthy Chinese Holstein cows during their first lactation were challenged with a strain of S. aureus. Details are described in our previous study [11]. Briefly, the three udder quarters of each cow were inoculated with 0.9% sterile pyrogen-free saline and low (106 cfu/mL) and high (109 cfu/mL) concentrations of the S. aureus strain. After the S. aureus challenge, udder punch biopsies were sampled from the quarters of the studied cows. In this study, mammary gland samples consisted of predominant secretory epithelial cells and a small number of other tissues, such as adipose and connective tissues. Accordingly, these groups were named as individual Control (iC), individual Low S. aureus (iL), and individual High S. aureus (iH).

The second and third experiments were finished in vitro by using bovine mammary alveolar cells (Mac-T cell line). Cells were treated with control, different S. aureus strains, or 5 μg/mL FA and infected with different S. aureus strains (MOI = 10:1). Eight groups (six samples per group), i.e., Control + Control (CC), Control + Strain L challenge (CL), Control + Strain M challenge (CM), Control + Strain MM challenge (CMM), FA treatment + Control (FC), FA treatment + Strain L challenge (FL), FA treatment + Strain M challenge (FM), FA treatment + Strain MM challenge (FMM), were established in the two experiments.

The fourth experiment was performed to investigate the association between bovine SNPs (in lncRNAs identified in the above experiments) and hematological parameters (HPs) of Chinese Holsteins. A total of 104 lactating Chinese Holsteins (parity ranging from 1 to 3, and lactation stage ranging from 1 to 150 d) were chosen. About 8 mL anticoagulant blood sample was collected from each cow, and 2 mL blood was sent to Jinhaikeyu Company for HP testing (Beijing, China). The genomic DNA was isolated from 400 μL blood, and SNPs were detected using the GGP Bovine HD150k (Neogen, Lansing, MI, USA).

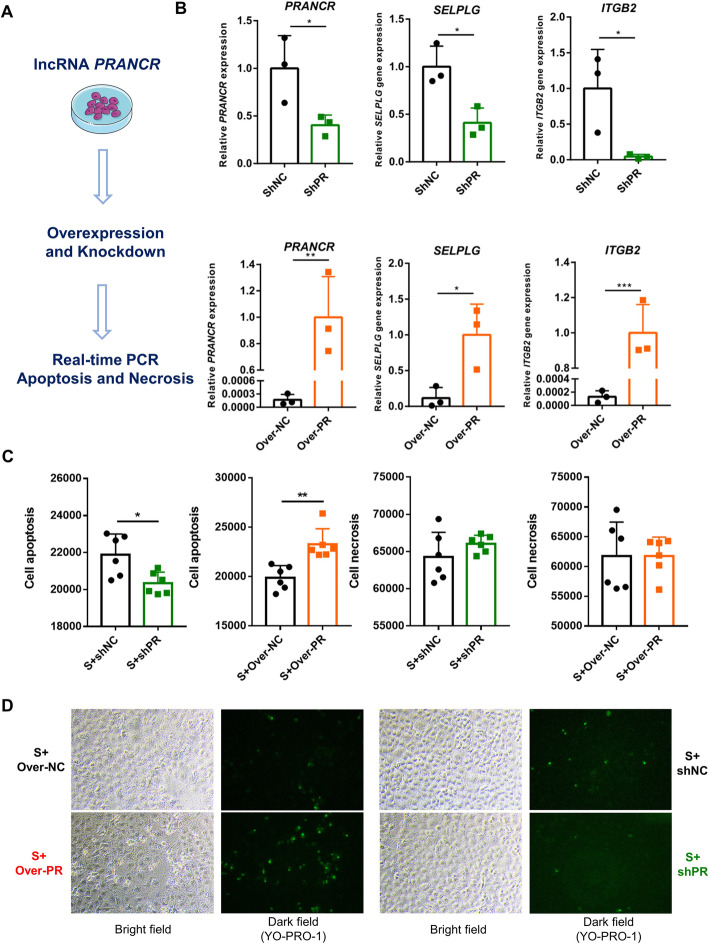

The last experiment was the function validation of lncRNA. In this section, the knockdown and overexpression of lncRNA was carried out, and cell apoptosis and necrosis were assessed.

Hematological parameters

Totally 24 hematological parameters were tested using the Sysmex K-4500 Automated Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Specific hematological parameters are as follows: White blood cell (WBC), Red blood cell (RBC), Haemoglobin (HGB), Red blood cell specific volume (HCT), Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV), Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), Platelet count (PLT), Neutrophils ratio (NETU%), Neutrophil counts (NETU#), Lymphocyte ratio (LYMPH%), Lymphocyte counts (LYMPH#), Monocyte ratio (MONO%), Monocyte counts (MONO#), Eosinophil ratio (EO%), Eosinophil counts (EO#), Basophile ratio (BASO%), Basophile counts (BASO#), Platelet distribution width (PDW), Mean platelet volume (MPV), Red cell distribution width-stand error (RDW-SD), Red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), Platelet-large cell ratio (P-LCR), Platelet cubic measure distributing width (PCT).

Cell culture, S. aureus challenge, and FA treatment

Mac-T cells were cultured in DMEM with GlutaMAX (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Initially, Mac-T cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates. At 80% confluence, Mac-T cells were treated with DMEM with or without extra 5 μg/mL FA for 24 h and infected with three S. aureus isolates or control (MOI = 10:1) for 6 h. Each experimental treatment was conducted in six replicates. After the above treatments, Mac-T cells were collected and stored at − 80 °C for further RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and sequencing

The total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA degradation was checked on 1% agarose gels. The NanoDrop 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to assess the concentration and purity of RNA. The RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system was used to measure the integrity of RNA. The average RNA integrity was more than 7 and 9 in cell and individual samples, respectively. Then, 3 μg RNA per sample was used to construct RNA-seq libraries. Finally, RNA-seq libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Novogene, Beijing, China).

Reads alignment and lncRNA identification

After the collection of RNA-seq raw data, reads alignment was performed. First, the quality of 150 bp paired-end reads were assessed using the FastQC version 0.11.8. Clean reads were obtained using the Trimmomatic software version 0.38 with default parameters (http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic). Clean reads were mapped to the bovine reference genome ARS-UCD1.2 (Ensembl annotation release 98) by using the HISAT2 version 2.1.0. After sorting and indexing using the Samtools version 1.9, each sample was assembled with the StringTie version 1.3.5. All assembled transcripts were merged into a new annotation file (GTF format) by using the GffCompare.

Novel lncRNA transcripts were identified in accordance with the following criteria. First, transcripts with length ≥ 200 nt and exon number ≥ 2 were retained. Among the different classes of the GffCompare, only class codes annotated by “i” (intronic lncRNA), “u” (intervening noncoding RNA), and “x” (antisense lncRNA) were retained, and the class code of known lncRNA transcripts was annotated by “=”. Finally, four software programs (i.e., CNCI, CPAT, CPC2, and PLEK) were applied to protein-coding potential prediction about transcripts annotated by “i”, “u”, and “x”, and transcripts with CNCI score < 0, CPAT score < 0.364, CPC2 score < 0, and PLEK score < 0 were retained. In this study, transcripts that met the above criteria were regarded as lncRNA transcripts. The FeatureCounts quantified the transcript abundance under the default setting, and the read count was normalized using the DESeq2.

Prediction of the cis and trans target mRNAs of lncRNA

In this study, mRNAs within 100 kb upstream and downstream of a lncRNA were defined as the cis target mRNA of the lncRNA, and this step was performed using the Bedtools. mRNA that had significant associations (|Pearson correlation| > 0.90 and P < 0.05) between itself and lncRNA expression was defined as the potential trans target mRNA of the lncRNA.

Differentially expressed gene identification and functional enrichment analysis

The differential expressed (DE) gene analysis was performed using the DESeq2 package in R. The read count from the FeatureCounts was normalized, and the rlog-normalized read count was also calculated. The normalized read count was then used to perform the differential expression analysis, and the rlog-normalized read count was used to conduct the multidimensional scaling.

DE genes with different criteria were defined in this study. The DE lncRNA of individual samples followed the criteria of P < 0.05 and |log2fold change| > 1, and the DE lncRNA of cell samples followed the criteria of q < 0.05 and |log2fold change| > 1.

In the integrated analysis of lncRNAs identified in individual and cell samples, lncRNA with the sum of corrected read counts in all individual samples > 3 and lncRNA with the sum of corrected read counts in all cell samples > 12 were retained to exclude the random error caused by low abundance lncRNA in this section. In addition, owing to the absence of intersection under the above filtering criteria (q < 0.05 and |log2Fold change| > 1) of DE lncRNA, lncRNAs with criteria P < 0.05 and same expression change direction in individual and cell S. aureus infection treatments were defined as stable DE lncRNAs for S. aureus infection treatment.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was performed using the target mRNAs of lncRNAs in the WebGestalt (http://www.webgestalt.org/). For the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) around DE lncRNAs, cattle QTLs were available to the AnimalQTLdb (https://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/QTLdb/index), and QTLs within 100 kb upstream and downstream of lncRNAs were retained.

Plasmid and shRNA transfection

Plasmid and shRNA construction were supported by Hitrobio.tech (Beijing, China). Full-length sequences of bovine lncRNA PRANCR were commercially synthesized and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 + vector. pcDNA3.1 + was used as vector control for analysis. shRNA targeting sequences are listed as follows: PRANCR (bovine), 5′-GGTGCTTGTGCACGCACTTCC-3′ and Scramble control sequence, 5′-GTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′. shRNA targeting sequences were cloned into pLKO.1-Puro. Plasmids and shRNAs were transfected into cells by using the Entranster-H4000 (Engreen Biosystem, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s recommended procedures.

Real-time PCR

The total RNA was extracted from the target cell by using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendation. Then, 1 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using the RT reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). The mRNA expression level was determined through qRT-PCR by using the SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche, Basel, Swiss) and analyzed on the Roche LightCycler 480 instrument. The GAPDH gene was used as the reference gene of target gene expression. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the relative gene expression level. Primers are listed as follows:

GAPDH-Forward: 5′-GGTGCTGAGTATGTGGTGGA-3′, GAPDH-Reverse: 5′-GGCATTGCTGACAATCTTGA-3′, PRANCR-Forward: 5′-TCTGCTCCCTGAAACGCATC-3′, PRANCR-Reverse: 5′- TACCAACGGTTTCGGCTGAC-3′, SELPLG-Forward: 5′- CTGAGCACGGTGCCATGTTTC-3′, SELPLG-Reverse: 5′-CTCTGGAGGGTCCGTTTGTC-3′, ITGB2-Forward: 5′- GAGTGCGACAACGTCAACTG-3′, and ITGB2-Reverse: 5′- ATGCCGAACCCTCATACTGC-3′.

Apoptosis and necrosis detection

A total of 5 × 104 cells within 0.1 mL complete medium per well were seeded into 96-well plates. When the logarithmic stage was reached, 0.1 μg/well plasmid or shRNA was transfected into cells for 36 h. Then cells were challenged with S. aureus solution for 6 h at an MOI of 10:1. Afterward, the Apoptosis and Necrosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to determine cell apoptosis and necrosis. All determination steps were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the fluorescence value was determined using the SpectraMax i3x Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

For fluorescence staining, a total of 2.5 × 105 cells within 0.5 mL of complete medium per well were seeded into 24-well plates. Similarly, after transfection and S. aureus challenge, cell apoptosis was determined by the above Apoptosis and Necrosis Detection Kit. Samples were photographed by Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Apoptotic cells were stained green by YO-PRO-1. In this section, Mac-T cells were challenged with the representative S. aureus strain Newman.

Statistical analysis

The linear regression analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism. Significant differences between treatment and control groups were examined using the Student’s t-test.

The general linear model procedure was used to detect the effects of polymorphism on hematological parameters (HPs) by using the Statistic Analysis System Version 9.2. Ten SNPs within 100 kb of bovine lncRNA PRANCR (Chromosome 15: 43,166,523 ~ 43,368,050) and eight SNPs within 100 kb of bovine lncRNA TNK2–AS1 (Chromosome 1: 70,540,306 ~ 70,741,382) were analyzed. Multiple tests were performed using the Bonferroni t method. In this study, P-value less than 0.05 indicated a significant difference. The effects included in the model were the same for all HPs:

where yijkl is the measure for HPs, μ is the overall mean, Pi is the fixed effect of parity (i = 1, 2, and 3, representing parities 1, 2, and 3, respectively), LSj is the fixed effect of lactation stage (j = 1, 2, and 3, representing lactation stages 1–50, 51–100, and 101–150 d, respectively), SNPk is the fixed effect of polymorphism for each SNP, and eijkl is the residual effects.

Results

Overview of high-throughput sequencing data in individual and cell samples

In summary, 6 samples in vivo and 48 samples in vitro were used for the RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 1). After quality trimming, 161 million and 1122 million clean read pairs were obtained from all cDNA libraries that included 6 individual samples from cow mammary gland tissue and 48 cell samples from bovine mammary gland alveolar cells (Mac-T cells), respectively. On average, 86.02% and 97.24% of the reads from individual and cell samples, respectively, were mapped to the cattle genome (Version: ARS-UCD1.2) by using HISAT2. Of these, 81.50% and 91.85% were uniquely mapped reads, and 4.07% and 2.19% were multi-mapped reads (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of reads mapped to bovine genome

| Items | Cell (Mac-T cell) |

Individual (Mammary gland tissue) |

|---|---|---|

| Clean reads | 1,122,383,385 | 161,180,893 |

| Total mapped reads | 1,094,511,424 | 138,645,272 |

| Total mapped rate, % | 97.52 | 86.02 |

| Unique mapping reads | 1,030,932,323 | 131,362,428 |

| Multi-mapping rate, % | 2.19 | 4.07 |

| Unique mapping rate, % | 91.85 | 81.50 |

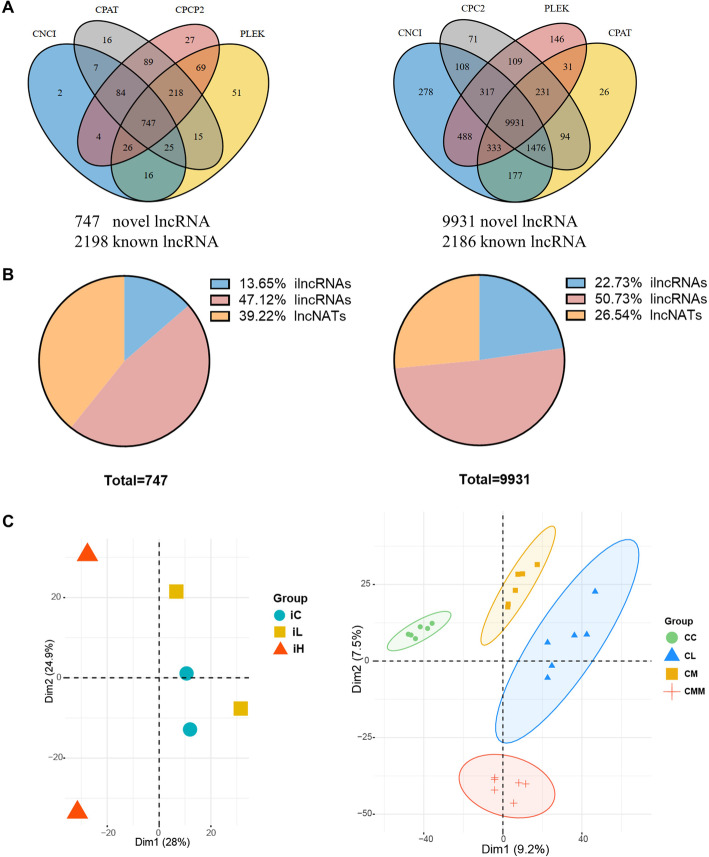

Identification and characterization of lncRNAs in individual and cell samples

A series of filter criteria was used to determine novel lncRNA candidates. First, 68,094 and 136,375 assembled transcripts were obtained using the StringTie in individual and cell samples, respectively. After transcript filtration and protein-coding potential prediction, 747 and 9931 non-coding sequences were obtained in individual and cell samples, respectively, which were considered as novel lncRNA transcripts. In summary, 2945 (2198 known) and 12,117 (2186 known) lncRNA transcripts were obtained in individual (left panel, Fig. 2A) and cell samples (right panel, Fig. 2A), respectively. Among the 747 and 9931 identified lncRNA transcripts, 102 and 2257, respectively, were intronic lncRNAs (ilncRNAs); 352 and 5038, respectively, were intervening noncoding RNAs (lincRNAs), and 293 and 2636, respectively, were antisense lncRNAs (lncNATs) in individual and cell samples (Fig. 2B). The proportions of ilncRNAs (13.65% and 22.73%) and lncNATs (39.22% and 26.54%) in individual and cell samples were remarkably different. The multidimensional scaling was conducted to examine the intragroup consistency and intergroup specificity, and the results showed that high specificity among different groups in individual and cell samples (Fig. 2C). In addition, cell samples with or without S. aureus infection could distinguish control and S. aureus infection groups at dim1, and samples with or without MRSA infection could be regarded as a vital influence factor at dim2, which was consistent with the experiment design.

Fig. 2.

Identification of lncRNAs and principal component analysis in individual and cell samples. (A) Venn diagrams for the prediction of potentially novel lncRNAs. CNCI, CPAT, CPC2, and PLEK software programs were applied to protein-coding potential prediction. (B) Category of novel identified lncRNAs. (C) Multidimensional scaling of different groups. Individual and cell samples are shown on the left and right panels, respectively. ilncRNAs: intronic lncRNAs, lincRNAs: intervening noncoding RNAs, lncNATs: antisense lncRNAs

Figure 3A–C show the number of exons, length, and chromosome distribution of the lncRNA transcript at the individual and cell levels. More than 90% of identified lncRNA transcript possessed 2–4 exons (Fig. 3A). Approximately 90% of lncRNA transcript length was found to be intensive within 103–105 bp (Fig. 3B). Moreover, these obtained lncRNAs were widely distributed in all chromosomes of the bovine genome, and the highest numbers of obtained lncRNAs existed in chromosomes 3 and 18 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Basic features of lncRNAs obtained in individual and cell samples. (A) Number of exons of obtained lncRNA transcripts. (B) Length and (C) chromosome distributions of obtained lncRNA transcripts. Chromosomes with the highest numbers of lncRNAs are marked with red arrows

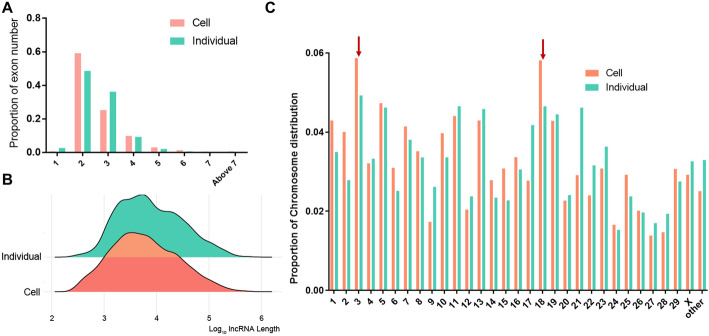

Identification and functional prediction of differentially expressed lncRNAs

A total of 44, 93, and 100 differentially expressed (DE) lncRNAs were obtained in individual samples, i.e., iC vs. iL, iC vs. iH, and iL vs. iH, respectively, and only three DE lncRNAs were common between iC vs. iL and iC vs. iH (Fig. S1A and Table S1). In cell samples, 280, 176, and 203 DE lncRNAs were identified in CL vs. CC, CM vs. CC, and CMM vs. CC, respectively (Fig. 4A and Table S2), and only 32 DE lncRNAs were common among the three treatments, which indicated the remarkable heterogeneity of host response induced by three different S. aureus isolate infections. In addition, the numbers of overlap gene between the cis target mRNAs of DE lncRNAs (Dlncm) and actual DE mRNAs (Dm) were assessed. Compared with the expected numbers of overlapped gene, there are 10 times of over-enrichment (OE) observed in the actual numbers of overlapped gene in the cell treatments (Fig. 4B), and 3 times of OE detected in the individual treatments (Fig. S1B). These results indicated that Dm were widely regulated by its neighboring DE lncRNAs.

Fig. 4.

Identification and functional prediction of DE lncRNAs. (A) Intersected outcome of DE lncRNAs induced by three different S. aureus strain challenge. (B) Overlaps between DE mRNA (Dm) and cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs (Dlncm) in cell samples. OE means fold of over-enrichment. (C) KEGG enrichment of the cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs. (D) Co-expression network of common DE lncRNAs and its cis/trans target mRNA. The network was drawn using the Cytoscape software. (E) Number of bovine complex traits’ QTLs associated with DE lncRNAs (Top 20 QTLs based on number are shown)

The functions of the overlapped genes between Dlncm and Dm were annotated by the KEGG pathway. In individual results, Dm were significantly enriched (P < 0.05) in some immunity-related pathways, such as S. aureus infection, toxoplasmosis, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway (Fig. S1C). Similar to individual results, the natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection, and breast cancer could be found in cell samples (Fig. 4C). The interaction network between DE lncRNAs and its cis/trans target mRNAs in cells is shown in Fig. 4D. Notably, eight DE mRNAs were cis/trans-regulated by DE lncRNAs MSTRG.14820.1, and Dm CGN was widely trans-regulated by five DE lncRNAs.

Usually, the genome location of DE lncRNAs with potential function might be close to some quantitative trait locus (QTLs) of animal complex traits. Currently, Cattle QTLdb included 160,659 QTLs representing 675 different complex traits. By comparing the genome location of DE lncRNAs and QTL-associated regions within Cattle QTLdb, in iC vs. iH, 74 out of 93 DE lncRNAs neighbor 1365 QTLs on the genome location, and in the S. aureus infection treatment of Mac-T cells vs. control, 23 out of 32 common DE lncRNAs neighbor 195 QTLs (Fig. 4E). The results suggest that these QTLs around DE lncRNAs were associated with milk secretion, health, and reproduction traits. More than 70% of these QTLs were intensive in milk-related traits (Table S3). These QTLs were also associated with immune-related traits, such as M. paratuberculosis susceptibility and somatic cell score (a commonly used indicator of mastitis), and reproduction-related traits, such as nonreturn rate and age at puberty.

Integrated analysis of lncRNAs identified in individual and cell samples

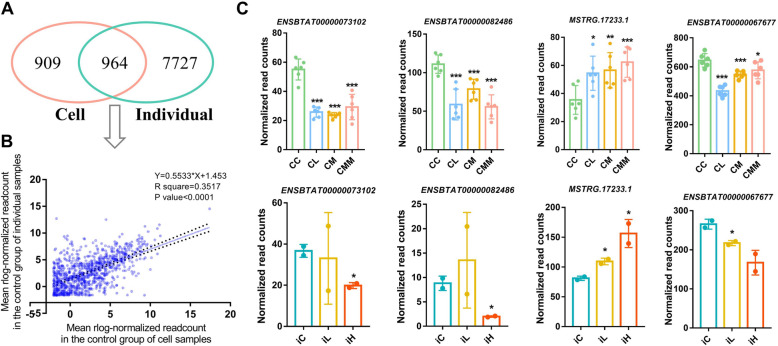

lncRNAs identified in mammary gland tissues of individuals and Mac-T cells were integrated to obtain stable lncRNA markers of mastitis induced by different S. aureus strains. A total of 964 lncRNAs were common in individual and cell control samples (Fig. 5A). The linear regression analysis was performed for the mean rlog-normalized read counts of the common 964 lncRNAs. The results (R2 = 0.3517, P < 0.0001; Fig. 5B) showed the significantly moderate correlation between individual and cell samples and indicated that the results outcome of cell samples could represent the partial results outcome of individual samples.

Fig. 5.

Association of identified lncRNAs between cell and individual samples. (A) Venn diagrams for lncRNAs identified in cell and individual control samples. (B) Linear regression analysis of the mean rlog-normalized read counts of 964 common lncRNAs in cell and individual control samples. (C) Expression level of four stable DE lncRNAs in cell and individual samples with criteria of P < 0.05 and same expression change direction

With the criteria of P < 0.05 and same expression change direction in individual and cell S. aureus infection treatments, four DE lncRNAs, i.e., ENSBTA00000073102, ENSBTA00000082486, MSTRG.17233.1, and ENSBTA00000067677, were obtained and defined as stable DE lncRNAs for S. aureus infection treatment (Fig. 5C).

The gene sequence-based conservation indicates similar and vital functions across species [19]. For the above four bovine stable DE lncRNAs, the preserved counterparts in humans were sought using the NONCODE (Table 2). Except ENSBTAT00000082486, all bovine stable DE lncRNAs had homologous genes in human, and significant somatic cell score QTLs neighbor these lncRNAs within about 20–300 kb. In humans, the preserved counterparts of bovine lncRNA MSTRG.17233.1 is the progenitor renewal associated non-coding RNA (lncRNA PRANCR), which functions as a regulator of epidermal homeostasis [20, 21], and ENSBTAT00000067677 is the TNK2 antisense RNA 1 (lncRNA TNK2–AS1) involved with cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis [22–24]. Based on their potentially preserved functions, these two lncRNAs were chosen for further analyses. Given their counterparts, i.e., PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 in humans, bovine MSTRG.17233.1 and ENSBTAT00000067677 were named as lncRNA PRANCR and TNK2–AS1, respectively, in this study.

Table 2.

Information of stable differentially expressed lncRNAs

| Homologous gene in human identified by NONCODE | Gene name | Site informationa | Closest identified QTLba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENSBTAT00000073102 | NONHSAT003723.2 | NA | 3:80,327,486-80,347,232 | 3:80,304,481-80,304,521 |

| ENSBTAT00000082486 | NA | NA | 20:8,025,966-8,027,066 | 20:7,770,475-7,770,515 |

| MSTRG.17233.1 | NONHSAT232219.1 | PRANCR | 5:43,266,523-43,268,050 | 5:43,569,644-43,569,648 |

| ENSBTAT00000067677 | NONHSAT195289.1 | TNK2-AS1 | 1:70,640,306-70,641,382 | 1:71,741,408-71,949,627 |

a Assembly: ARS-UCD1.2/bosTau9

bSomatic cell score QTL in cow (data from Animal QTL Database)

QTL: quantitative trait locus

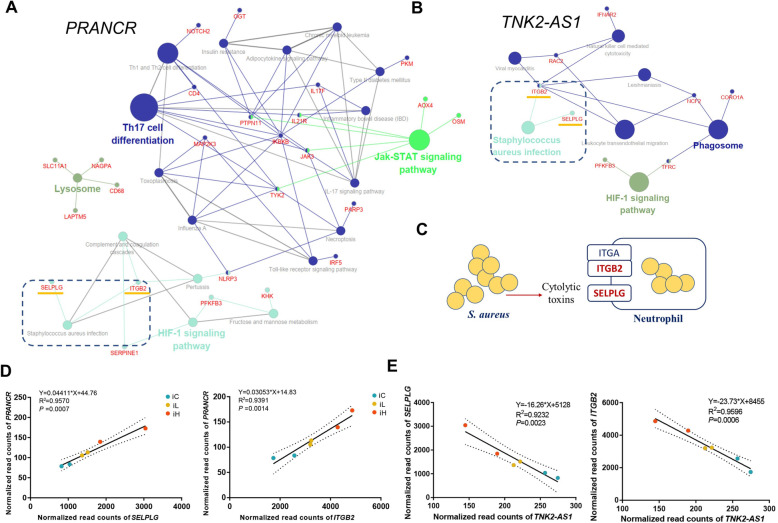

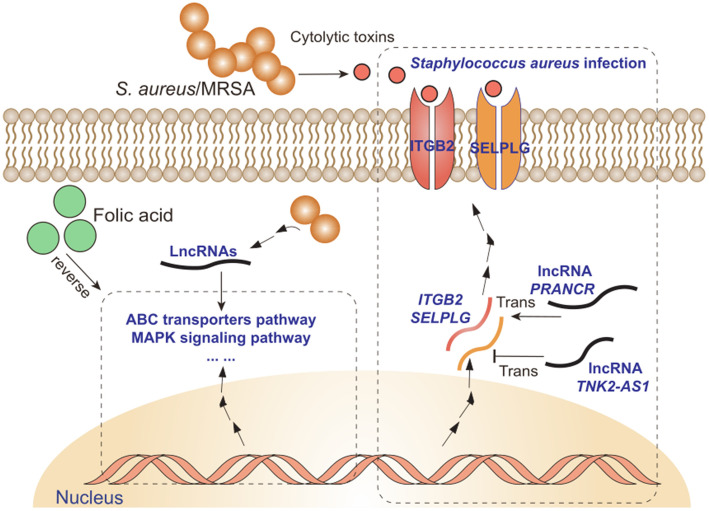

lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 as stable markers of S. aureus mastitis

The trans and cis target mRNAs of lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 were first identified to further understand the potential function of lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1. The KEGG enrichment analysis of these mRNAs showed that amounts of immunity-related pathways, such as S. aureus infection, Jak–STAT signaling pathway, Th17 cell differentiation, and phagosome, were enriched (Fig. 6A and B). These results indicated that lncRNAs PRANCR and TN2–AS1 were widely involved in the inflammatory response induced by S. aureus challenge. Integrin subunit beta 2 (ITGB2) and selectin P ligand (SELPLG) within the pathway of S. aureus infection were the receptors of S. aureus cytolytic toxins (Fig. 6C), and the results of linear regression analysis showed that the bovine milk somatic cell count (SCC) and the expression of ITGB2 and SELPLG were positively correlated with lncRNA PRANCR and negatively correlated with lncRNA TNK2–AS1 (R2 > 0.92, P < 0.01, Figs. S2A, 6D, and 6E). In addition, a significantly negative expression correlation was observed between PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 (Fig. S2B).

Fig. 6.

Functional prediction of lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1. KEGG pathway enrichment of cis and trans target mRNAs of lncRNAs (A) PRANCR and (B) TNK2–AS1. (C) Part of the genes involved in S. aureus infection pathway. Linear regression analysis of normalized read counts among lncRNAs (D) PRANCR, (E) TNK2–AS1, and its trans target mRNA SELPLG and ITGB2. SELPLG: gene of Selectin P Ligand, ITGB2: gene of Integrin Subunit Beta 2

Folic acid protect host against S. aureus challenge by regulating the expression level of lncRNAs involved in toxin transport and inflammatory response-related pathways

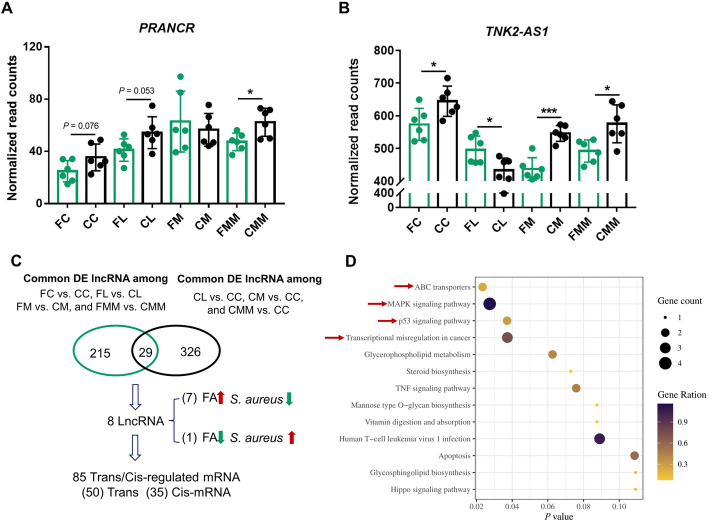

FC, FL, FM, and FMM groups were established to understand the interplays among host lncRNAs, the target mRNAs of lncRNA, S. aureus infection, and FA treatment (Fig. 1). First, the effects of FA on lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 were investigated. Regarded to PRANCR, FA can hamper the upregulation of the lncRNA in the comparisons of CC vs. FC, CL vs. FL, and CMM vs. FMM (Fig. 7A). As for TNK2–AS1, the downregulation of the lncRNA is hampered by FA only in the comparison of CL vs. FL (dotted box in Fig. 7B). The preliminary results indicated the regulatory roles of FA in inflammation response induced by specific S. aureus strain challenge.

Fig. 7.

Cis and trans target mRNAs of key lncRNAs influenced by folic acid that are involved in toxin transport and inflammatory response-related pathways. Normalized read counts of lncRNAs (A) PRANCR and (B) TNK2–AS1 in different groups. (C) Intersected results and cis/trans target mRNA identification of lncRNAs between folic acid and S. aureus treatment groups. Here, DE lncRNAs were defined with the criteria of P < 0.05. (D) KEGG enrichment results of the target mRNAs of the eight key lncRNAs

The relationship between DE lncRNAs induced by S. aureus infection or FA treatment was further investigated. A total of 244 common DE lncRNAs in the comparisons between FA treatment and corresponding control (i.e., FC vs. CC, FL vs. CL, FM vs. CM, and FMM vs. CMM) and 355 common DE lncRNAs in the comparisons between S. aureus infection and control (CL vs. CC, CM vs. CC, and CMM vs. CC) were obtained, and 29 DE lncRNAs intersected between the above 244 and 355 common DE lncRNAs. In 8 of these 29 lncRNAs, the expression changes induced by S. aureus infection could be reduced and reversed by FA treatment (Fig. 7C). Then, 50 trans and 35 cis target mRNAs of these eight lncRNAs were obtained. The results of KEGG enrichment showed that the toxin transport and inflammatory response-related pathways (e.g., ABC transporters, MAPK signaling pathway, and p53 signaling pathway) were regulated by these lncRNAs (Fig. 7D).

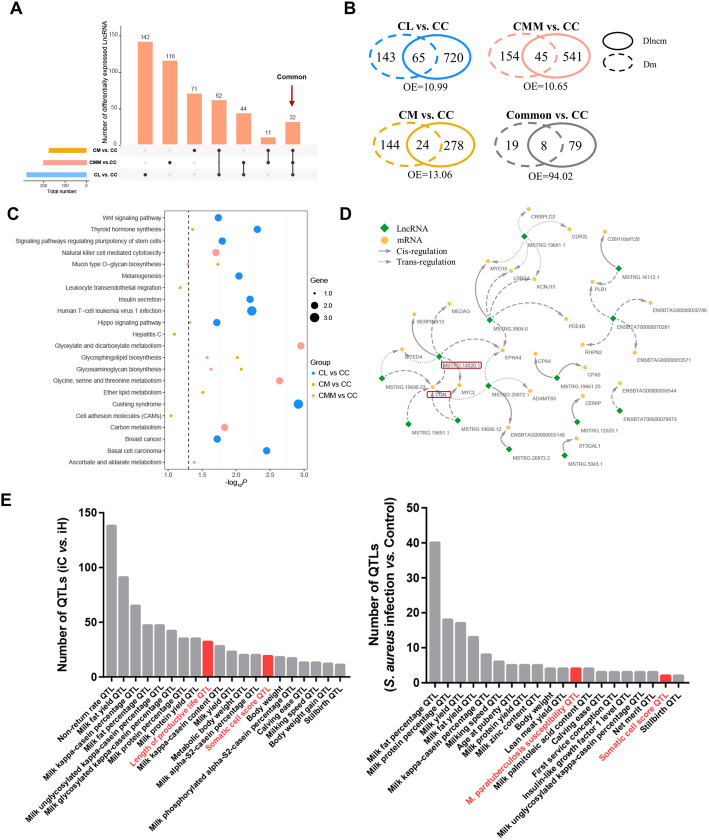

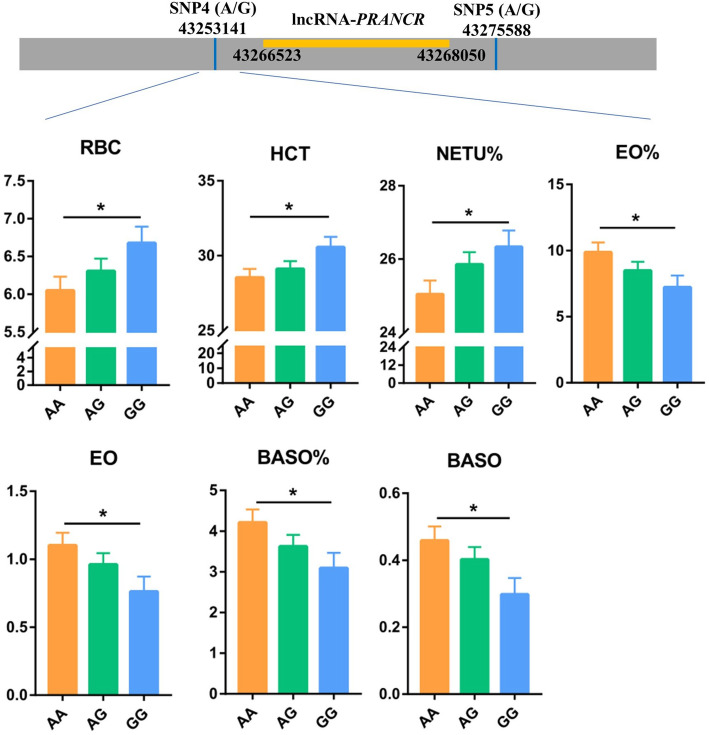

lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 were associated with hematological parameters

The potential association between SNPs within 100 kb lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 and hematological parameters (HPs) were analyzed to further validate the function of lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 on immune response (Table S4). For the lncRNA PRANCR, 4 out of 11 SNPs were significantly associated with the partial indicators of HP (Table S5, P < 0.05). Significant associations between SNP4 and red blood cell (RBC), red blood cell specific volume (HCT), percentage of neutrophil (NETU%), percent of eosinophile granulocyte count (EO%), eosinophile granulocyte count (EO#), percent of basophilic granulocyte count (BASO%), and basophilic granulocyte count (BASO#, Fig. 8), and between SNP8 and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) were found. Moreover, SNP10 and SNP11 were significantly associated with mean corpuscular volume (MCV). Among the 11 SNPs, SNP4 was the closest to the location of the lncRNA PRANCR. Furthermore, the NETU%, EO#, EO%, BASO#, and BASO% were key indicators reflecting the host immune level. Similar to the lncRNA PRANCR, a nearly significant association existed between the SNP closest to the lncRNA TNK2–AS1 and the platelet-large cell ratio (P-LCR) of HP (Table S6 and Fig. S3). These results showed that lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 could be regarded as indicators of cow immune status.

Fig. 8.

Blood routine test parameters significantly associated with the SNP4 of lncRNA PRANCR. The grey box notes the fragment of chromosome, the yellow box notes the location of lncRNA PRANCR. RBC: Red blood cell; HCT: Red blood cell specific volume; NETU%: Neutrophils ratio; EO%: Eosinophil ratio; EO#: Eosinophil counts; BASO%: Basophile ratio; BASO#: Basophile counts

lncRNA PRANCR influences the apoptosis of Mac-T cells induced by S. aureus challenge

Finally, lncRNA PRANCR was chosen for the experiment of gene knockdown and overexpression to confirm the function of the lncRNA on regulating the cell immune response (Fig. 9A). First, the regulation of PRANCR on its trans target mRNAs was investigated. Consistent with the results of linear regression (Fig. 6D), the knockdown of lncRNA PRANCR significantly reduced the mRNA expression of SELPLG and ITGB2, and the overexpression of this lncRNA significantly increase the mRNA expression of SELPLG and ITGB2 (P < 0.05, Fig. 9B). Subsequently, the regulatory effects of lncRNA PRANCR on cell apoptosis and necrosis were investigated. Our results showed the knockdown or overexpression of lncRNA PRANCR doesn’t influence cell apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. S4). It is worth noted that the knockdown of lncRNA PRANCR remarkably reduced the cell apoptosis induced by S. aureus challenge, and that the overexpression of this lncRNA significantly promoted the cell apoptosis, and this lncRNA cannot influence cell necrosis (Fig. 9C). The results of fluorescence staining also verified the function of lncRNA PRANCR on cell apoptosis induced by S. aureus challenge (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

Involvement of PRANCR with S. aureus infection pathway and the regulation of cell apoptosis. (A) Workflow of PRANCR function validation. (B) Relative expression levels of PRANCR, SELPLG, and ITGB2. (C) Functions of PRANCR on cell apoptosis and necrosis. (D) Cell apoptosis was assessed with fluorescence microscopy. Apoptotic cells were stained green by YO-PRO-1. S: S. aureus challenge, Over: plasmid for lncRNA overexpression, sh: the shRNA for lncRNA knockdown, NC: negative control, and PR: lncRNA PRANCR

Discussion

Increasing evidence reveals that lncRNAs are widely involved in host response to pathogen invasion [25–27]. In this study, the basic features of obtained lncRNA transcripts were first characterized in Mac-T cells in vitro and bovine mammary gland tissue samples in vivo. Owing to the bigger data size and higher mapping rate in cell samples than in individual samples (Table 1), more lncRNA transcripts were identified in cell samples (Fig. 2A). Most identified lncRNA transcripts were located in intergenic regions, and this finding was consistent with those in previous studies [28–30]. Moreover, our results showed that lncRNAs were widely distributed on all chromosomes especially the largest number of Chromosome 3, and this finding was similar to that of previous studies on Mac-T cells [31]. The results indicated the potentially extensive involvement of lncRNAs in bovine complex traits.

S. aureus is one of the main pathogens of bovine mastitis [3, 32]. Previous studies reported that several bovine lncRNAs may regulate the host immune response to S. aureus infection. In the cell model of bovine S. aureus mastitis, the S. aureus adhesion to epithelial cells can be mediated by lncRNAs TUB and H19 [31, 33], and the NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway is regulated by the lncRNA XIST [34]. However, the host immune response to S. aureus is demonstrated to be dependent on the lineages of this bacterium [7, 32, 35]. Until now, the heterogeneity and similarity of lncRNAs involved in inflammatory response induced by different S. aureus strain infection are not explained well. In our analysis, only 32 DE lncRNAs were shared among the three different bovine milk-originated S. aureus strains, which reminded us that when studying host–pathogen interactions, heterogeneity between strains should be considered. The chronic inflammation engaged in the progress of cancer is widely recognized [36–38], and the pathways of breast cancer and basel cell carcinoma are exclusively enriched in the comparison of CL vs. CC, which implied the potential harm of strain L (isolated from a cow with low milk SCC) to the host. Moreover, previous studies reported that the host’s inflammatory response and cytokine expression level are dependent on pathogen concentration [39–41]. Our results also showed few overlaps of DE lncRNAs (only 3 common DE lncRNAs) and differentially activated KEGG pathways between the comparisons of iC vs. iL and iC vs. iH. Thus, identifying the stable molecular markers of S. aureus mastitis is difficult under different S. aureus lineages and loads.

Emerging evidence indicates that many lncRNAs act their functions by interacting with mRNA in cis- and trans-manner [42–45]. In the present study, the significant overlaps between cis target Dlncms and Dms also confirmed that the differential expression of mRNA could be regulated by its neighboring DE lncRNAs. Previous studies identified numbers of lncRNAs located in the QTLs of complex traits among several species [46–49]. The results of the present study showed that 4/23 (17.39%) and 25/74 (33.78%) DE lncRNAs were associated with health-related QTLs in CC vs. S. aureus infection groups (CL, CM, and CMM) and in iC vs. iH (Table S3), respectively. Moreover, 17/23 (73.91%) and 59/74 (79.73%) DE lncRNAs in CC vs. S. aureus infection groups and iC vs. iH, respectively, were related to multi-trait QTLs, which implied the multiple effects of these lncRNAs on the regulation of milk production and immunity-related traits.

Immortalized Mac-T cells are primarily established from primary bovine mammary alveolar cells [50]. In this study, the tissue punch biopsy was adopted, and the samples of obtained mammary gland consisted of several tissues and cells, such as mammary epithelial cell, adipose tissue and connective tissue. Besides, neutrophils also widely exist in the mammary gland after infected with pathogen [51, 52]. The above differences between Mac-T cells and mammary gland tissues may explain the few shared DE lncRNAs between cell and individual samples (Fig. 5A) in the current study. The significantly moderate correlation (0.3517) of lncRNA expression between Mac-T cells and mammary gland tissues indicated that Mac-T cells cannot be completely regarded as the alternative of bovine mammary gland. The results of Mac-T cells should be tested at the bovine individual level.

Under the different S. aureus strains challenge, the consistent expression changes of four lncRNAs were observed at the cell and individual levels. Among these four lncRNAs, three lncRNAs were conserved between human and cattle. Evidence shows that lncRNA TNK2–AS1 downregulation can inhibit cell proliferation and migration and promote apoptosis [22–24]. Moreover, in human, lncRNA PRANCR is closely related with epidermis formation and ovarian cancer metastasis [20, 21, 53]. Our study found the regulatory effect of PRANCR on the cell apoptosis induced by S. aureus challenge. In addition, the regulation of the lncRNA PRANCR on the mRNA expression of SELPLG and ITGB2 within S. aureus infection pathway were confirmed in the overexpression and knockdown validation. However, whether the regulatory effect of the lncRNA on cell apoptosis by directly mediating SELPLG and ITGB2 remains to be further studied. The HP detection can help diagnose organ and systemic disorders in dairy cow [54–56]. The significant associations between SNPs closest to these two lncRNAs and partial HP indicated that SNPs nearby PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 could be regarded as potential molecular markers affecting the immunity of dairy cows. In other studies, the association between SNPs and HP is also widely investigated [57, 58], but the causal mutation within these two lncRNAs should be further explored for future animal breeding.

A healthy mammary gland with immune equilibrium is essential for the host to fight against pathogen infection [7]. Previous studies reported that moderately extra FA intake can improve the host immune capacity and reduce inflammation and oxidative stress [59–61]. Our previous results also indicated that for dairy cows, FA supplementation reduces mastitis incidence and promotes milk production [4, 5]. In Mac-T cells infected with S. aureus, the results of the present study showed that the expression of genes within ABC transporters [62] involved with toxin secretion, MAPK signaling pathway [63] and p53 signaling pathway [64] related with inflammatory regulation can be influenced by FA treatment through the regulation of lncRNAs. FA is a kind of methyl-donor. A previous study found that methyl-donor supplemented diet prevents the colonization of intestinal E. coli in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease, which may be by influencing the DNA methylation level of CEACAM6 gene (a kind of cell adhesion molecule) [65]. Similarly, in mice, FA supplementation prevent Helicobacter-associated gastric cancer by increasing global DNA methylation [13]. Thus, in the present study, whether FA affects lncRNA expression by affecting DNA methylation needs further exploration. Our findings will help understand the roles of lncRNA in S. aureus infection and provide an improved approach for the effective diagnosis and prevention of bovine S. aureus mastitis.

Conclusion

Consequently, this study characterized an important lncRNA resource of the interplays among bovine mammary gland tissues/Mac-T cells, different S. aureus strains infection, and FA treatment (Fig. 10). lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1 can be regarded as stable molecular markers of bovine S. aureus mastitis. The negative effect of S. aureus infection on the host can be partially prevented and reduced by FA supplementation.

Fig. 10.

Interplays among host immune responses of transcriptome (lncRNA and mRNA), S. aureus infection, and folic acid treatment

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Identification and KEGG enrichment of cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs. (A) Venn diagrams among the different comparisons of individual samples. (B) Overlaps between DE mRNA and cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs in individual samples. OE means fold of over-enrichment. (C) KEGG enrichment of cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs. iC: mammary gland challenged with saline; iL: mammary challenged with low concentration of S. aureus; iH: mammary challenged with high concentration of S. aureus. Figure S2. (A) Correlations between somatic cell count and lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1. (B) Correlation between the two lncRNAs. Figure S3. Blood routine test parameters significantly associated with the SNP4 of lncRNA TNK2-AS1. The grey box notes the fragment of chromosome, the green box notes the location of lncRNA TNK2-AS1. P-LCR: Platelet-large cell ratio; RBC: Red blood cell. Figure S4. The influence of PRANCR on cell apoptosis and necrosis. Over: plasmid for lncRNA overexpression, sh: the shRNA for lncRNA knockdown, NC: the negative control, and PR: lncRNA PRANCR.

Additional file 4. Bovine QTL information

Additional file 6. Association between PRANCR SNPs and HPs

Additional file 7. Association between TNK2-AS1 SNPs and HPs

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mengyou Yang, Hui Wen, Wenlong Li and all the members of the Animal Molecular and Quantitative Genetics Laboratory in China Agricultural University, and professor Xin Wang in Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University for the study design, samples collection and data analysis.

Abbreviations

- S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus

- SCC

Somatic cell count

- FA

Folic acid

- Strain L

S. aureus isolated from the cow with low milk somatic cell counts

- Strain M

S. aureus isolated from the cow with mastitis

- Strain MM

MRSA isolated from the cow with mastitis

- Mac-T cells

Mammary alveolar cells

- CC

Control + control in vitro

- CL

Control + Strain L infection in vitro

- CM

Control + Strain M infection in vitro

- CMM

Control + Strain MM infection in vitro

- FC

Folic acid treatment + control in vitro

- FL

Folic acid treatment + Strain L infection in vitro

- FM

Folic acid treatment + Strain M infection in vitro

- FMM

Folic acid treatment + Strain MM infection in vitro

- iC

Individual Control

- iL

Individual challenged with Low concentration of S. aureus

- iH

Individual challenged with High concentration of S. aureus

- DE

Differentially expressed

- lncRNA

Long non-coding RNA

- ilncRNA

Intronic lncRNA

- lincRNA

Intervening lncRNA

- Dlncm

Cis target mRNAs of differentially expressed lncRNA

- Dm

Differentially expressed mRNA

- lncNAT

Antisense lncRNA

- PRANCR

Progenitor renewal associated non-coding RNA

- TNK2-AS1

TNK2 antisense RNA 1

- HP

Hematological parameters

And the abbreviations of hematological parameters are shown as below

- WBC

White blood cell

- RBC

Red blood cell

- HGB

Haemoglobin

- HCT

Red blood cell specific volume

- MCV

Mean Corpuscular Volume

- MCH

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin

- MCHC

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration

- PLT

Platelet count

- NETU%

Neutrophils ratio

- NETU#

Neutrophil counts

- LYMPH%

Lymphocyte ratio

- LYMPH#

Lymphocyte counts

- MONO%

Monocyte ratio

- MONO#

Monocyte counts.

- EO%

Eosinophil ratio

- EO#

Eosinophil counts

- BASO%

Basophile ratio

- BASO#

Basophile counts

- PDW

Platelet distribution width

- MPV

Mean platelet volume

- RDW-SD

Red cell distribution width-stand error

- RDW-CV

Red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation

- P-LCR

Platelet-large cell ratio

- PCT

Platelet cubic measure distributing width.

Authors’ contributions

YY and SYM conceived the study. SYM and YJT collected the samples. SYM, YJT, and HLZ analyzed the data. SYM, GD, and YJS conducted the experiment. YY, SYM, JNZ, HLZ wrote and prepared the manuscript. XQL, YBL and UT provided the suggestions about lncRNA analysis. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the NSFC-PSF Joint Project (31961143009), Beijing Dairy Industry Innovation Team (BAIC06), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, Beijing Natural Science Foundation (6182021), and the Program for Changjiang Scholar and Innovation Research Team in University (IRT-15R62).

Availability of data and materials

RNA-seq data (in vivo) had been submitted to the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number SRP073432. RNA-Seq (in vitro) and 150 K SNP-chip data from China Agricultural University is available upon the agreement of China Agricultural University and should be requested directly from the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee, China Agricultural University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Halasa T, Huijps K, Østerås O, Hogeveen H. Economic effects of bovine mastitis and mastitis management: a review. Vet Quart. 2007;29(1):18–31. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2007.9695224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miles AM, Huson HJ. Graduate student literature review: understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying mastitis. J Dairy Sci. 2021;104(1):1183–1191. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-18297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rainard P, Foucras G, Fitzgerald JR, Watts JL, Koop G, Middleton JR. Knowledge gaps and research priorities in Staphylococcus aureus mastitis control. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(S1):149–165. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MZ, Khan A, Xiao J, Dou J, Liu L, Yu Y. Overview of folic acid supplementation alone or in combination with vitamin B12 in dairy cattle during Periparturient period. Metabolites. 2020;10(6):263. doi: 10.3390/metabo10060263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MZ, Zhang Z, Liu L, Wang D, Mi S, Liu X, Liu G, Guo G, Li X, Wang Y, Yu Y. Folic acid supplementation regulates key immunity-associated genes and pathways during the periparturient period in dairy cows. Asian Austral J Anim. 2020;33(9):1507–1519. doi: 10.5713/ajas.18.0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zbinden C, Stephan R, Johler S, Borel N, Bunter J, Bruckmaier RM, et al. The inflammatory response of primary bovine mammary epithelial cells to Staphylococcus aureus strains is linked to the bacterial phenotype. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoekstra J, Rutten VPMG, Lam TJGM, Van Kessel KPM, Spaninks MP, Stegeman JA, et al. Activation of a bovine mammary epithelial cell line by ruminant-associated Staphylococcus aureus is lineage dependent. Microorganisms. 2019;7(12):688. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Xiu L, Hu Q, Cui X, Liu B, Tao L, Wang T, Wu J, Chen Y, Chen Y. Deep sequencing-based transcriptional analysis of bovine mammary epithelial cells gene expression in response to in vitro infection with Staphylococcus aureus stains. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81(1):145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Goede OM, Nachun DC, Ferraro NM, Gloudemans MJ, Rao AS, Smail C, Eulalio TY, Aguet F, Ng B, Xu J, Barbeira AN, Castel SE, Kim-Hellmuth S, Park YS, Scott AJ, Strober BJ, Brown CD, Wen X, Hall IM, Battle A, Lappalainen T, Im HK, Ardlie KG, Mostafavi S, Quertermous T, Kirkegaard K, Montgomery SB, Anand S, Gabriel S, Getz GA, Graubert A, Hadley K, Handsaker RE, Huang KH, Li X, MacArthur DG, Meier SR, Nedzel JL, Nguyen DT, Segrè AV, Todres E, Balliu B, Bonazzola R, Brown A, Conrad DF, Cotter DJ, Cox N, Das S, Dermitzakis ET, Einson J, Engelhardt BE, Eskin E, Flynn ED, Fresard L, Gamazon ER, Garrido-Martín D, Gay NR, Guigó R, Hamel AR, He Y, Hoffman PJ, Hormozdiari F, Hou L, Jo B, Kasela S, Kashin S, Kellis M, Kwong A, Li X, Liang Y, Mangul S, Mohammadi P, Muñoz-Aguirre M, Nobel AB, Oliva M, Park Y, Parsana P, Reverter F, Rouhana JM, Sabatti C, Saha A, Stephens M, Stranger BE, Teran NA, Viñuela A, Wang G, Wright F, Wucher V, Zou Y, Ferreira PG, Li G, Melé M, Yeger-Lotem E, Bradbury D, Krubit T, McLean JA, Qi L, Robinson K, Roche NV, Smith AM, Tabor DE, Undale A, Bridge J, Brigham LE, Foster BA, Gillard BM, Hasz R, Hunter M, Johns C, Johnson M, Karasik E, Kopen G, Leinweber WF, McDonald A, Moser MT, Myer K, Ramsey KD, Roe B, Shad S, Thomas JA, Walters G, Washington M, Wheeler J, Jewell SD, Rohrer DC, Valley DR, Davis DA, Mash DC, Barcus ME, Branton PA, Sobin L, Barker LK, Gardiner HM, Mosavel M, Siminoff LA, Flicek P, Haeussler M, Juettemann T, Kent WJ, Lee CM, Powell CC, Rosenbloom KR, Ruffier M, Sheppard D, Taylor K, Trevanion SJ, Zerbino DR, Abell NS, Akey J, Chen L, Demanelis K, Doherty JA, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Hickey PF, Jasmine F, Jiang L, Kaul R, Kibriya MG, Li JB, Li Q, Lin S, Linder SE, Pierce BL, Rizzardi LF, Skol AD, Smith KS, Snyder M, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Tang H, Wang M, Carithers LJ, Guan P, Koester SE, Little AR, Moore HM, Nierras CR, Rao AK, Vaught JB, Volpi S. Population-scale tissue transcriptomics maps long non-coding RNAs to complex disease. Cell. 2021;184(10):2633–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang L, Hou Y, An J, Li B, Song M, Wang X, Sørensen P, Dong Y, Liu C, Wang Y, Zhu H, Zhang S, Yu Y. Genome-wide transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of innate immune and defense responses of bovine mammary gland to Staphylococcus aureus. Front Cell Infect Mi. 2016;6:193. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appuhamy JADR, Bell AL, Nayananjalie WAD, Escobar J, Hanigan MD. Essential amino acids regulate both initiation and elongation of mRNA translation independent of insulin in MAC-T cells and bovine mammary tissue slices. J Nutr. 2011;141(6):1209–1215. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.136143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonda TA, Kim YI, Salas MC, Gamble MV, Shibata W, Muthupalani S, et al. Folic acid increases global DNA methylation and reduces inflammation to prevent Helicobacter-associated gastric cancer in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):824–833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan MZ, Liu L, Zhang Z, Khan A, Wang D, Mi S, Usman T, Liu G, Guo G, Li X, Wang Y, Yu Y. Folic acid supplementation regulates milk production variables, metabolic associated genes and pathways in perinatal Holsteins. J Anim Physiol An N. 2019;104(2):483–492. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma F, Li W, Tang R, Liu Z, Ouyang S, Cao D, Li Y, Wu J. Long non-coding RNA expression profiling in obesity mice with folic acid supplement. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42(1):416–426. doi: 10.1159/000477486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu S, Guo W, Li X, Liu Y, Li Y, Lei X, Yao J, Yang X. Paternal chronic folate supplementation induced the transgenerational inheritance of acquired developmental and metabolic changes in chickens. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2019;286(1910):20191653. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng X, Zhan F, Hu J, Hua F, Xu G. LncRNA-mRNA expression profiles and functional networks associated with cognitive impairment in folate-deficient mice. Comb Chem High T Scr. 2021;24. 10.2174/1386207324666210208110517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wang X, Wang X, Wang Y, Guo G, Usman T, Hao D, Tang X, Zhang Y, Yu Y. Antimicrobial resistance and toxin gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus strains from Holstein milk. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;58(6):527–534. doi: 10.1111/lam.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma H, Carninci P. The secret life of lncRNAs: conserved, yet not conserved. Cell. 2020;181(3):512–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai P, Otten ABC, Cheng B, Ishii MA, Zhang W, Huang B, Qu K, Sun BK. A genome-wide long noncoding RNA CRISPRi screen identifies PRANCR as a novel regulator of epidermal homeostasis. Genome Res. 2020;30(1):22–34. doi: 10.1101/gr.251561.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otten A, Cai P, Cheng B, Ishii M, Qu K, Sun B. 194 a CRISPR-interference screen identifies PRANCR and other novel long non-coding RNAs controlling human epidermis formation. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(9):S248. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao W, Yan Q, Du X, Hou J. TNK2-AS1 upregulated by YY1 boosts the course of osteosarcoma through targeting miR-4319/WDR1. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(2):893–905. doi: 10.1111/cas.14727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai T, Cui X, Zhang K, Zhang A, Liu B, Mu JJ. LncRNA TNK2-AS1 regulated ox-LDL-stimulated HASMC proliferation and migration via modulating VEGFA and FGF1 expression by sponging miR-150-5p. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(11):7289–7298. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Han D, Pan L, Sun J. The positive feedback between lncRNA TNK2-AS1 and STAT3 enhances angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2018;507(1–4):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heward JA, Lindsay MA. Long non-coding RNAs in the regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(9):408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YG, Satpathy AT, Chang HY. Gene regulation in the immune system by long noncoding RNAs. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(9):962–972. doi: 10.1038/ni.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosinska-Selbi B, Mielczarek M, Szyda J. Review: long non-coding RNA in livestock. Animal. 2020;14(10):2003–2013. doi: 10.1017/S1751731120000841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai W, Li C, Liu S, Zhou C, Yin H, Song J, Zhang Q, Zhang S. Genome wide identification of novel long non-coding RNAs and their potential associations with milk proteins in Chinese Holstein cows. Front Genet. 2018;9:281. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou J, Schenkel F, Hu L, Khan A, Khan MZ, Yu Y, Wang Y, Wang Y. Genome-wide identification and functional prediction of long non-coding RNAs in Sprague-Dawley rats during heat stress. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07421-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozdemir S, Altun S. Genome-wide analysis of mRNAs and lncRNAs in mycoplasma bovis infected and non-infected bovine mammary gland tissues. Mol Cell Probes. 2020;50:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2020.101512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Wang X, Li X, Wang Q, Qing S, Zhang Y, Gao MQ. A novel long non-coding RNA regulates the immune response in MAC-T cells and contributes to bovine mastitis. FEBS J. 2019;286(9):1780–1795. doi: 10.1111/febs.14783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi BF, Bonsaglia ECR, Pantoja JCF, Santos MV, Gonçalves JL, Fernandes Júnior A, Rall VLM. Short communication: association between the accessory gene regulator (agr) group and the severity of bovine mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J Dairy Sci. 2021;104(3):3564–3568. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-19275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Wang H, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Qi S, Zhang Y, Gao MQ. Overexpression of lncRNA H19 changes basic characteristics and affects immune response of bovine mammary epithelial cells. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6715. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma M, Pei Y, Wang X, Feng J, Zhang Y, Gao M. LncRNA XIST mediates bovine mammary epithelial cell inflammatory response via NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Cell Proliferat. 2019;52(1):e12525. 10.1111/cpr.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Budd KE, Mitchell J, Keane OM. Lineage associated expression of virulence traits in bovine-adapted Staphylococcus aureus. Vet Microbiol. 2016;189:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herszényi L, Lakatos G, Hritz I, Varga MZ, Cierny G, Tulassay Z. The role of inflammation and proteinases in tumor progression. Digest Dis. 2012;30(3):249–254. doi: 10.1159/000336914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonardi GC, Accardi G, Monastero R, Nicoletti F, Libra M. Ageing: from inflammation to cancer. Immun Ageing. 2018;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12979-017-0112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinoshita T, Goto T. Links between inflammation and postoperative Cancer recurrence. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):228. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chanrot M, Blomqvist G, Guo Y, Ullman K, Juremalm M, Bage R, Donofrio G, Valarcher JF, Humblot P. Bovine herpes virus type 4 alters TNF-alpha and IL-8 profiles and impairs the survival of bovine endometrial epithelial cells. Reprod Biol. 2017;17(3):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danesh Mesgaran S, Gärtner MA, Wagener K, Drillich M, Ehling-Schulz M, Einspanier R, Gabler C. Different inflammatory responses of bovine oviductal epithelial cells in vitro to bacterial species with distinct pathogenicity characteristics and passage number. Theriogenology. 2018;106:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gärtner MA, Bondzio A, Braun N, Jung M, Einspanier R, Gabler C. Detection and characterization of lactobacillus spp. In the bovine uterus and their influence on bovine endometrial epithelial cells in vitro. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e119793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gil N, Ulitsky I. Regulation of gene expression by cis-acting long non-coding RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21(2):102–117. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172(3):393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joung J, Engreitz JM, Konermann S, Abudayyeh OO, Verdine VK, Aguet F, Gootenberg JS, Sanjana NE, Wright JB, Fulco CP, Tseng YY, Yoon CH, Boehm JS, Lander ES, Zhang F. Genome-scale activation screen identifies a lncRNA locus regulating a gene neighbourhood. Nature. 2017;548(7667):343–346. doi: 10.1038/nature23451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun M, Kraus WL. From discovery to function: the expanding roles of long NonCoding RNAs in physiology and disease. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(1):25–64. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez M, Rocha D, Charles M, Boussaha M, Hozé C, Brochard M, et al. Sequence-based GWAS and post-GWAS analyses reveal a key role of SLC37A1, ANKH, and regulatory regions on bovine milk mineral content. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87078-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li W, Jing Z, Cheng Y, Wang X, Li D, Han R, Li W, Li G, Sun G, Tian Y, Liu X, Kang X, Li Z. Analysis of four complete linkage sequence variants within a novel lncRNA located in a growth QTL on chromosome 1 related to growth traits in chickens. J Anim Sci. 2020;98(5):5. doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mell B, Cheng X, Joe B. QTL mapping of rat blood pressure loci on RNO1 within a homologous region linked to human hypertension on HSA15. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e221658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi J, Shin D, Lee H, Oh J. Comparison of long noncoding RNA between muscles and adipose tissues in Hanwoo beef cattle. Anim Cells Syst. 2019;23(1):50–58. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2018.1512522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huynh HT, Robitaille G, Turner JD. Establishment of bovine mammary epithelial cells (MAC-T): An in vitro model for bovine lactation. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90422-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viguier C, Arora S, Gilmartin N, Welbeck K, O Kennedy R. Mastitis detection: current trends and future perspectives. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(8):486–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asselstine V, Miglior F, Suárez-Vega A, Fonseca PAS, Mallard B, Karrow N, Islas-Trejo A, Medrano JF, Cánovas A. Genetic mechanisms regulating the host response during mastitis. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102(10):9043–9059. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X, Yu S, Yang R, Wang Q, Liu X, Ma M, Li Y, Wu S. Identification of lncRNA-associated ceRNA network in high-grade serous ovarian cancer metastasis. Epigenomics. 2020;12(14):1175–1191. doi: 10.2217/epi-2020-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirzadeh K, Tabatabaei S, Bojarpour M, Mamoei M. Comparative study of hematological parameters according strain, age, sex, physiological status and season in iranian cattle. J Anim Vet Adv. 2010;9(16):2123–2127. doi: 10.3923/javaa.2010.2123.2127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roland L, Drillich M, Iwersen M. Hematology as a diagnostic tool in bovine medicine. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2014;26(5):592–598. doi: 10.1177/1040638714546490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Archambault D, Beliveau C, Couture Y, Carman S. Clinical response and immunomodulation following experimental challenge of calves with type 2 noncytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Res. 2000;31(2):215–227. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Z, Hong Y, Gao J, Xiao S, Ma J, Zhang W, Ren J, Huang L. Genome-wide association study reveals constant and specific loci for hematological traits at three time stages in a white duroc × erhualian f2 resource population. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macedo LC, Santos BC, Pagliarini-e-Silva S, Pagnano KB, Rodrigues C, Quintero FC, et al. JAK2 46/1 haplotype is associated with JAK2 V617F--positive myeloproliferative neoplasms in Brazilian patients. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(5):654–660. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calder P, Carr A, Gombart A, Eggersdorfer M. Optimal nutritional status for a well-functioning immune system is an important factor to protect against viral infections. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1181. doi: 10.3390/nu12041181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cronstein BN, Aune TM. Methotrexate and its mechanisms of action in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(3):145–154. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dubois-Deruy E, Peugnet V, Turkieh A, Pinet F. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants. 2020;9(9):864. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vasiliou V, Vasiliou K, Nebert DW. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum Genomics. 2008;3(3):281–290. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-3-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun Y, Liu W, Liu T, Feng X, Yang N, Zhou H. Signaling pathway of MAPK/ERK in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence and apoptosis. J Recept Sig Transd. 2015;35(6):600–604. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2015.1030412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kruiswijk F, Labuschagne CF, Vousden KH. P53 in survival, death and metabolic health: a lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2015;16(7):393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrm4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gimier E, Chervy M, Agus A, Sivignon A, Billard E, Privat M, et al. Methyl-donor supplementation prevents intestinal colonization by Adherent-Invasive E. coli in a mouse model of Crohn's disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12922. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69472-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Identification and KEGG enrichment of cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs. (A) Venn diagrams among the different comparisons of individual samples. (B) Overlaps between DE mRNA and cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs in individual samples. OE means fold of over-enrichment. (C) KEGG enrichment of cis target mRNA of DE lncRNAs. iC: mammary gland challenged with saline; iL: mammary challenged with low concentration of S. aureus; iH: mammary challenged with high concentration of S. aureus. Figure S2. (A) Correlations between somatic cell count and lncRNAs PRANCR and TNK2–AS1. (B) Correlation between the two lncRNAs. Figure S3. Blood routine test parameters significantly associated with the SNP4 of lncRNA TNK2-AS1. The grey box notes the fragment of chromosome, the green box notes the location of lncRNA TNK2-AS1. P-LCR: Platelet-large cell ratio; RBC: Red blood cell. Figure S4. The influence of PRANCR on cell apoptosis and necrosis. Over: plasmid for lncRNA overexpression, sh: the shRNA for lncRNA knockdown, NC: the negative control, and PR: lncRNA PRANCR.

Additional file 4. Bovine QTL information

Additional file 6. Association between PRANCR SNPs and HPs

Additional file 7. Association between TNK2-AS1 SNPs and HPs

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data (in vivo) had been submitted to the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number SRP073432. RNA-Seq (in vitro) and 150 K SNP-chip data from China Agricultural University is available upon the agreement of China Agricultural University and should be requested directly from the authors.