Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate parents' preferences regarding the appearance and attire of orthodontists.

Materials and Methods:

Parents attending their child's first orthodontic appointment were asked to choose from among sets of photographs of potential orthodontic providers. Selected factors were varied within the sets, including sex and age of the provider as well as attire (casual, formal, white coat, or scrubs), hairstyle (loose or tied back for women, facial hair or clean shaven for men), and presence of a nametag.

Results:

A total of 77 parents participated. There were significant differences in choice of provider in terms of the provider's sex (P < .0001), age (P = .0013), dress (P < .0001), hair (P < .0001), and nametag (P = .0065). There were no significant differences in preference attributable to parent characteristics (P > .05).

Conclusion:

Parents of orthodontic patients demonstrated clear preferences for choosing a provider related to factors that are not within the control of the practitioner (sex and age) as well as factors that can be changed by the practitioner (attire, hairstyle, and wearing a nametag).

Keywords: Practice management, Uniform, Hair, Facial hair, Professionalism

INTRODUCTION

The appearance and attire of medical professionals have long been considered important; for instance, Hippocrates wrote that the physician's “dress should be neat and his person clean” so the public will trust that he is qualified to attend to their health.1 The white coat itself has been a powerful symbol of authority and healing worn by medical practitioners for more than 100 years.2 The appropriate appearance and attire for physicians has been debated over time and evaluated extensively, but there are few studies published in the dental literature and none specific to the specialty of orthodontics regarding this issue.

In the medical literature, patients generally report that they prefer their physician to be dressed in a traditional, formal style. In one study, 76% of patients favored professional attire for their physician (shirt and tie for men, tailored trousers or skirt for women) along with a white coat as opposed to scrubs (10%), business dress (9%), or casual dress (<5%).3 Physicians appearing well-dressed in white coats were judged to be more trustworthy, knowledgeable, and competent.3 Another study, however, reported that most patients did not consider attire when choosing their physician, although of those who did, 76% preferred a white coat.4 Parents selected the most formally dressed physicians when choosing among photos of pediatricians, and this did not vary by the parents' demographic characteristics, such as age, race, or sex.5 Other studies have supported the finding that wearing formal attire, including a tie for men; wearing a white coat; and having a clearly visible nametag were considered desirable by patients.6–11 The presence of facial jewelry, visible tattoos, nontraditional hairstyles, and facial hair on men were characteristics that reduced a patient's confidence in his or her physician.12 Interest persists in defining what constitutes appropriate professional attire and how this may change as greater proportions of women continue to enter the health professions.

Unlike physicians in a hospital setting, dental practitioners are most often small business owners who determine their own dress code and appearance. Nearly 80% of the respondents to one survey reported that the appearance and attire of their dental care provider affected their opinion of the care they would receive.13 In a 2007 study, most dental patients surveyed preferred the use of nametags and a formal style of dress accompanied by a white coat, saying that it conveyed a sense of professionalism and authority.14 In another study comparing patient preferences for the appearance of dentists in different types of practices, patients said they had no preference between white coats or scrubs; however, the use of nametags was preferred more commonly for a practice with multiple doctors, such as the orthodontic group practice involved in that particular study.15 Recently, 90% of 9- to 12-year-old children stated that they preferred their dentist to wear traditional formal attire and a white coat.16 To date, no studies have specifically investigated patient or parent preferences toward the appearance and attire of orthodontists.

In an increasingly competitive market, orthodontists should consider all factors that may influence a parent's choice of provider. In a recent survey, the most highly ranked factor in choosing an orthodontist was that the “orthodontist appears competent, knowledgeable and confident.”17 Thus, an orthodontist's appearance and attire are likely to be highly important. The objective of this study was to evaluate parents' preferences regarding the appearance and attire of orthodontists. The findings may encourage orthodontists to alter those factors within their control to conform to styles that are most preferred by the public.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of six persons, three men and three women, one from each age group (younger - less than 35; middle - between 35 and 55; and older - more than 35) (Table 1) agreed to pose as providers for this computer-based survey administered in an orthodontic practice setting. All parents who brought a child for an initial screening visit to the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Orthodontic Clinic between September and December 2012 were asked to participate in this study by answering the survey questions before attending their appointment. The Institutional Review Board of VCU granted permission to conduct this study.

Table 1.

Persons Depicted as the Orthodontic Providers in This Study

The primary aim was to determine the effect of the orthodontist's appearance and attire according to the following five provider characteristics: sex (male, female), age (younger, middle, older), dress (casual, formal, white coat, scrubs), hair (controlled, uncontrolled), and nametag (nametag, no nametag). Each of the providers dressed in four types of attire (casual, formal, white coat, and scrubs). Casual attire consisted of a short-sleeve polo shirt of a solid color. Formal attire, for the purposes of this study, was a button-down, collared blouse for women and a collared shirt and tie for men. The photos showed people from the waist up. The white coat was worn over the formal attire for the subset of photographs that required a white coat. Scrubs were standard blue or green surgical scrubs. In addition, the six providers wore their hair in a controlled or uncontrolled style. For women, controlled meant that the hair was pulled back off of the face into a ponytail and uncontrolled meant that the hair was long and down around the face. For men, controlled meant the absence of facial hair and uncontrolled meant the presence of a mustache. The presence or absence of nametags was also varied.

The design of experiments platform in JMP software (SAS ver 9.3 Proc Mixed, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, Cary NC) was used to determine that a total of 12 choice sets would be sufficient to present the combinations of factors required to determine significant differences at P < .05. Parent evaluators were shown each of these choice sets containing four photographs and were asked to choose from each set the one provider they most preferred and the one they least preferred. To assess repeatability, an additional 13th choice set was used as a control to determine if a repeated presentation would yield the same results. Photographs for the first choice set are shown in Figure 1. Evaluators were permitted to take the survey only once.

Figure 1.

Choice set 1 showing, from left to right: older woman with a white coat, controlled hair, and no nametag; an older woman with casual attire, uncontrolled hair, and a nametag; a younger man with a white coat, controlled hair, and a nametag; a younger woman with a white coat, uncontrolled hair, and a nametag.

Parent sex, age, race, ethnicity, educational level, and family income were recorded. The remainder of the survey asked the parent to consider the 13 choice sets, each of which contained four photographs as described earlier. Specifically, the survey asked the parent to “Select the one photograph that depicts the orthodontist that you are MOST LIKELY to choose as a care provider.” The same four photographs were presented again and the prompt changed to “Select the one photograph that depicts the orthodontist that you are LEAST LIKELY to choose as a care provider.”

Repeated measures mixed model analysis of variance (Proc Mixed, ver 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, SAS) was used to determine whether there were significant differences in choice of orthodontist related to any of the five provider characteristics: sex, age, dress, hair, and nametag. Additionally, possible evaluator influences due to parent's sex, age, race, ethnicity, education level, and income were considered and investigated.

RESULTS

A total of 86 parents participated as evaluators. Nine were removed from the analyses due to incomplete responses. Of the 77 parents who completed the survey during their child's first screening visit to the orthodontist, 81% were women, of various ages but most commonly between 41 and 45 years; 58% were white, 32% African American, and 13% Hispanic; and 67% had some college or more education. Reported annual household incomes ranging from <$25,000 to >$120,000.

The third provider choice set was repeated at the end of the study as the 13th choice set. There was no significant difference in the rankings assigned by evaluators for the four pictures between the two choice sets (P = .378). Most (204/308; 66%) of the rankings assigned to the photos by evaluators were identical in the two choice sets (Kappa = 0.45; P < .0001).

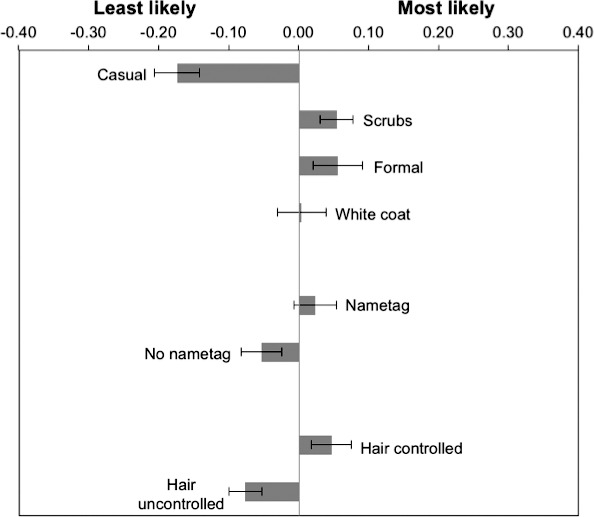

Parent preferences for their choice of orthodontist showed significant differences according to the provider's sex (P = .0013), age (P < .0001), dress (P < .0001), hair (P < .0001), and nametag (P = .0065). The most preferred image was the middle-aged man wearing formal attire, having a clean shaven face, and wearing a nametag. The least preferred image was the middle-aged man wearing casual attire, having facial hair, and wearing no nametag. Results are separated into those factors that cannot be altered by the provider (age and sex) and those that can be altered (dress, hair control, and nametag).

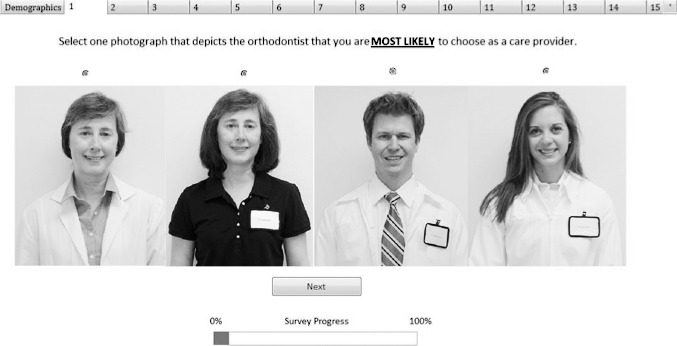

Parent preferences for the unalterable variables of sex and age are shown in Figure 2. There was an overall preference for female providers (P = .0013). When combining results for the male and female providers, there was an overall preference for younger orthodontists (P < .0001). There were also a significant interaction between sex and age (P < .0001); the most preferred providers were the younger woman and the older man.

Figure 2.

Individual and combined effects of sex and age on parents' preference for an orthodontist.

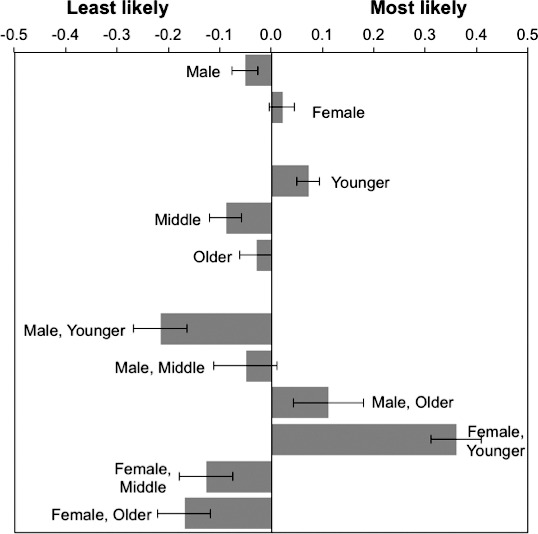

Parent preferences for the alterable provider characteristics (dress, hair, and nametag) are shown in Figure 3. Casual dress was the least preferred; formal attire and scrubs were both preferred styles (P < .0001). The evaluators did not indicate a preference one way or the other regarding the use of a white coat. For hair, there was a positive preference for controlled hair (pulled back for women, clean shaven for men) and a negative response associated with uncontrolled hair (loose hair for women, facial hair for men) (P < .0001). The use of a nametag was desirable, and the lack of identification with a nametag was undesirable (P = .0065).

Figure 3.

Individual effects of dress, nametag, and hair control on parents' preference for an orthodontist.

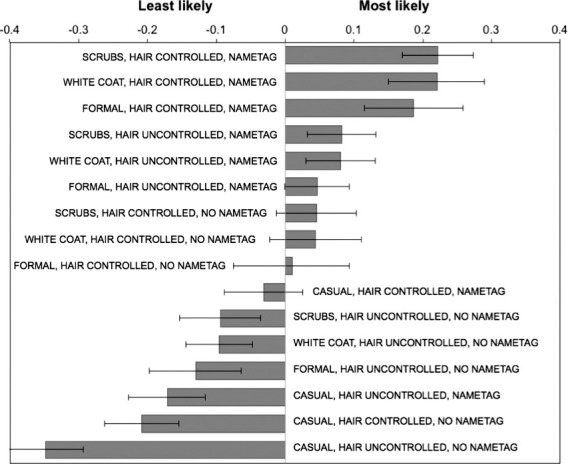

Each orthodontist's appearance included the combination of all three factors: dress, hair, and nametag. Therefore, each of these combinations could be ranked from most preferred to least preferred, and this order is shown in Figure 4. The most highly preferred styles were providers who had controlled hair; were dressed in formal attire, a white coat, or scrubs; and wore a nametag. All of the photographs that depicted providers with casual dress had consistently negative ratings.

Figure 4.

Combined effect of dress, hair control, and nametag on parents' preference for an orthodontist.

Analysis of the parent evaluators' characteristics (parents' sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, and income) showed that they did not influence the choice of an orthodontist (P > .05). There was one significant interaction, however, between the parents' education level and choice of the provider's sex (P = .0168). Although parents of all education levels preferred female providers, this preference was less pronounced for parents with higher levels of education.

DISCUSSION

Parents demonstrated that they have significant preferences related to the appearance and attire of orthodontic providers. No previous study has examined the influence of the orthodontist's appearance and attire on a parent's choice of an orthodontist to provide care for his or her child. Every variable examined (sex, age, dress, hair, and nametag) showed a statistically significant influence on the preferences demonstrated. Parents had clear positive and negative preferences for all of the alterable characteristics studied (dress, hair, and nametag). Specifically, there was a positive preference for providers depicted wearing formal attire or scrubs, having controlled hair, and displaying a nametag. There was a negative preference associated with casual attire, uncontrolled hair, and the absence of a nametag. The presence or absence of a white coat showed no positive or negative effect on a parents' choice of an orthodontist in this study.

Unalterable provider characteristics (sex and age) were also associated with significant differences in parents' preferences. There was an overall preference for female providers. This is consistent with a recent dental study that found a similar preference for female dentists.18 Although this preference is likely multifactorial, it may be related to a previous finding that female dentists were more likely to be seen as possessing empathy-related traits as well as having more effective communication and calming skills.19 This may be particularly relevant as those surveyed in this study were parents seeking practitioners for their children who may consider these traits desirable. There was an overall preference for younger providers, which is in accordance with previous studies that found patients had an overall preference for younger dentists.20 This may reflect a predilection for younger providers who are perceived by the public as most up to date with recent advances and modern techniques.

By far the least preferred style of dress was casual, which is consistent with the findings of many previous studies.3–7,11,14 The use of casual attire, common in many orthodontic practices today, may have come from the feared white-coat syndrome, which was thought to be present among adults and children. However, studies confirm that people do not fear white coats but instead oftentimes prefer them.7,16,21,22 Parents in this study preferred an orthodontist in formal attire or scrubs more than an orthodontist dressed casually. This finding was quite clear; thus, based on these results, a practitioner may wish to reassess his or her choice of attire and consider a more formal, professional style of dress.

Parents demonstrated an overall preference for orthodontists with controlled hair. For female practitioners, this meant wearing their hair in a neat, tied-back fashion, and for male practitioners, this meant being clean shaven and without facial hair. Controlled hair is the overall preference for both sexes in the orthodontic setting, which may be related to the physical proximity of the orthodontist to the patient in the dental chair. Perhaps this finding indicates that uncontrolled hair may be perceived as less hygienic. Therefore, providers should be cognizant of their appearance and avoid uncontrolled hair in the orthodontic office.

In this study, there was also a strong preference for the use of a nametag by practitioners. The top six rated photographs all depicted orthodontists wearing a nametag. This is consistent with multiple other studies in the medical and dental literature.4,8,14,15,21 Identifying information, such as a nametag, may be of particular importance for female providers as most orthodontic support staff members are also women. Parents would likely want to be able to identify the orthodontist by name and distinguish him or her from the staff. Introducing nametags into an orthodontic practice would be a very simple and practical way to be more appealing to parents. These findings should encourage practitioners to wear nametags if they are not already doing so. For orthodontists who are looking to hire an associate, this study provides important information about parents' preference for specific provider characteristics. Future studies may want to consider the potential effect of ethnicity on the parents' preference of a provider.

The findings from this study indicate clearly that parents do have significant preferences for orthodontic practitioners who have a formal, professional, and neat appearance to care for their children.

CONCLUSIONS

Parents demonstrated a significant, positive preference for orthodontists to wear formal attire (button-down, collared blouse for women and collared shirt and tie for men) or scrubs, have controlled hair (tied back for women, clean shaven for men), and display a nametag.

There was a significant negative preference for casual attire, uncontrolled hair (loose hair for women, facial hair for men), and the absence of a nametag.

Demographic characteristics of parents did not significantly influence the choice of the most and least preferred orthodontic providers.

The most preferred providers by parents were the younger woman and the older man.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coxe JR. The Writings of Hippocrates and Galen. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsay and Blakiston; 1846. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumhagen DW. The doctor's white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Inter Med. 1979;91:111–116. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-1-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, Kilpatrick AO. What to wear today? Effect of doctor's attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menahem S, Shvartzman P. Is our appearance important to our patients. Fam Pract. 1998;15:391–397. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez Del Ray JA, Paul RI. Preferences of parents for pediatric emergency physicians' attire. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11:361–364. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Major K, Hayase Y, Balderrama D, Lefor AT. Attitudes regarding surgeons' attire. Am J Surg. 2005;190:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenum AJ, Wallace LS, Stevens AR. Patients' attitudes regarding physical characteristics of family practice physicians. South Med J. 2003;96:1190–1194. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000077011.58103.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients' preferences for doctors' appearance and mode of address. BMJ. 2005;331:1524–1527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy JJ, McCarthy MC, Eilert RE. Children's and parents' visual perception of physicians. Clin Pediatr. 1999;38:145–152. doi: 10.1177/000992289903800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuscu OO, Caglar E, Kayabasoglu N, Sandalli N. Short communication: preferences of dentist's attire in a group of Istanbul school children related with dental anxiety. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:38–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03262666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marino RV, Rosenfeld W, Narula P, Karakurum M. Impact of pediatricians' attire on children and parents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1991;12:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, Lascher S. The physician's attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:132–138. doi: 10.7547/0960132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brosky ME, Keefer OA, Hodges JS, Pesun IJ, Cook G. Patient perceptions of professionalism in dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:909–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna G, Lillywhite GRR, Maini N. Patient preferences for dental clinical attire: a cross-sectional survey in a dental hospital. Br Dent J. 2007;203:681–685. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shulman ER, Brehm WT. Dental clinical attire and infection-control procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;4:508–516. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AlSarheed M. Children's perception of their dentists. Eur J Dent. 2011;5:186–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longoria JM, English J, O'Neil PN, Tan Q, Velasquez G, Walji M. Factors involved in choosing an orthodontist in a competitive market. J Clin Orthod. 2011;45:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swami V, McClelland A, Bedi R, Furham A. The influence of practitioner nationality, experience, and sex in shaping patient preferences for dentists. Int Dent J. 2011;61:193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MK, Dundes L. The implications of gender stereotypes for the dentist-patient relationship. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:562–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furnham A, Swami V. Patient preferences for dentists. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14:143–149. doi: 10.1080/13548500802282690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui D, Cho M, Rieder MJ. Physician's attire as perceived by young children and their parents: the myth of the white coat syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:198–201. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy JJ, McCarthy MC, Eilert RE. Children's and parent's visual perception of physicians. Clin Pediatr. 1999;38:145–152. doi: 10.1177/000992289903800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]