Abstract

Objective:

To compare the accuracy of measurements obtained from the three-dimensional (3D) laser scans to those taken from the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans and those obtained from plaster models.

Materials and Methods:

Eighteen different measurements, encompassing mesiodistal width of teeth and both maxillary and mandibular arch length and width, were selected using various landmarks. CBCT scans and plaster models were prepared from 60 patients. Plaster models were scanned using the Ortho Insight 3D laser scanner, and the selected landmarks were measured using its software. CBCT scans were imported and analyzed using the Avizo software, and the 26 landmarks corresponding to the selected measurements were located and recorded. The plaster models were also measured using a digital caliper. Descriptive statistics and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were used to analyze the data.

Results:

The ICC result showed that the values obtained by the three different methods were highly correlated in all measurements, all having correlations >0.808. When checking the differences between values and methods, the largest mean difference found was 0.59 mm ± 0.38 mm.

Conclusions:

In conclusion, plaster models, CBCT models, and laser-scanned models are three different diagnostic records, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The present results showed that the laser-scanned models are highly accurate to plaster models and CBCT scans. This gives general clinicians an alternative to take into consideration the advantages of laser-scanned models over plaster models and CBCT reconstructions.

Keywords: Cone-beam computed tomography, Digital models, Plaster models

INTRODUCTION

Three-dimensional (3D) digital model scanners are increasingly being incorporated into various orthodontic offices and institutions. They are no longer regarded as a mere additional tool in dental record keeping but a potential replacement of the traditional plaster models that have been necessary in treatment planning in orthodontics for many decades. Three-dimensional digital model scanning is an indirect imaging technique where the physical plaster model or impression is scanned by a laser scanner and subsequently reconstructed as a digital file. Most digital model scanners use one or more cameras with a light source such as laser or LED. Despite the extra step involved when compared to the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), which is a direct imaging technique, digital model scanners are rapidly gaining popularity in many orthodontic practices because they cost less money, space, and maintenance compared to physical models. Furthermore, the scanners provide more convenient access to study the models.1

Some studies have reported the difference between the plaster models and computer digital models to be clinically acceptable.2,3 Whetten et al.4 further studied the clinical implication in orthodontic treatment planning and reported that digital models are an acceptable alternative to plaster models in treatment planning for patients with Class II malocclusions. However, most of the previous studies presented the comparison of digital models only to the traditional plaster models.2,3,5 Due to the rapid adoption of the 3D model scanners in dental offices, different manufacturers are continuously introducing new scanners and software products with new technologic improvements and features, such as the capability to integrate scanned digital models with CBCT scans. However, the accuracy of digital model scanners in comparison to the plaster models and CBCT technology, which has been proven to yield high accuracy, often need further research to prove their clinical effectiveness.

CBCT has been used to produce 3D digital imaging of anatomic dental and craniofacial morphology with its capability to instantly produce 3D direct imaging with minimal patient discomfort as a primary advantage.6 Its accuracy has proved to exhibit accurate measurements, showing “1-to-1 image-to-reality ratio.”7 Furthermore, its capability to visualize root morphology and resorption without the superimpositions and distortions commonly found in the conventional radiographic imaging technique may provide valuable diagnostic information for orthodontic treatment planning.8 Despite the increasing adoption of this technology in the field of dentistry, its current role in orthodontic settings is limited to the diagnostics tool in assessment of unerupted tooth position, supernumerary teeth, and other certain circumstances.8 Additionally, the controversy over its radiation dose and its possible risk to the public has hindered CBCT from being routinely used for diagnostic purposes.6 This limitation in orthodontic practices is exacerbated by the economic and convenience factors associated with the CBCT equipment when compared to the traditional plaster models.

The aim of this study is to compare the accuracy of measurements obtained from the 3D laser scans to those taken from the CBCT scans and those obtained from the plaster models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maxillary and mandibular plaster models and their corresponding CBCT scans (I-Cat, Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, Pa) from 60 patients were used in this study. Model impressions and CBCT images were obtained on the same day for each patient at the Orthodontic Program in the University of Alberta. Exclusion criteria for patients were primary teeth present, extensive edentulous regions, and not having complete dental arch from first molar to first molar present in the maxilla and mandible.

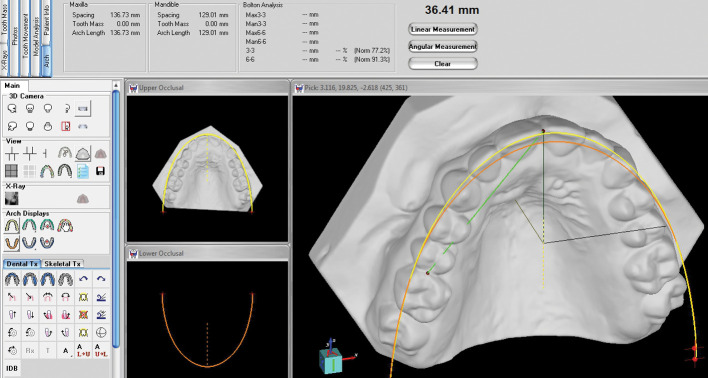

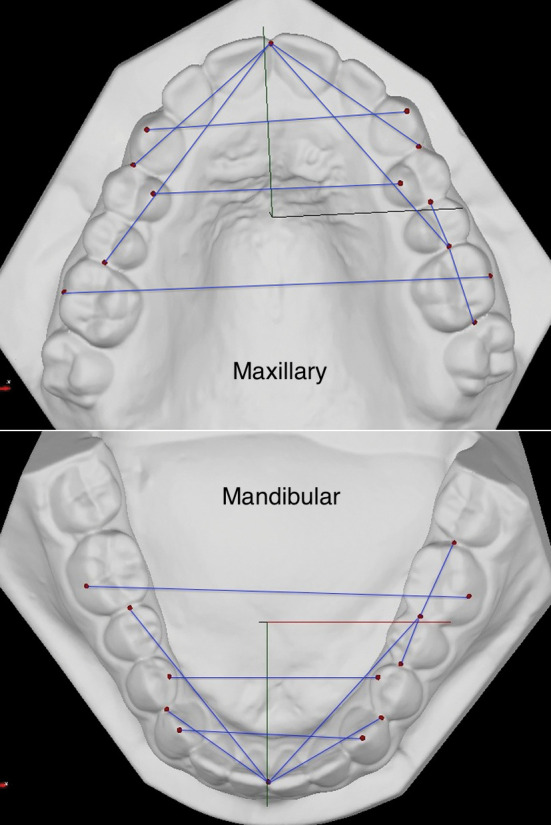

Each patient's maxillary and mandibular plaster models were scanned using the Ortho Insight 3D laser scanner (Motionview Software LLC, Hixson, Tenn), with scanning resolution set in “mid.” Using the Ortho Insight 3D software (version 4.0.6), measurements to the nearest 0.01 mm were recorded by locating necessary landmarks using the software's intrinsic linear measurement function (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Arch length measured on 3D digital model obtained from laser scanner using Ortho Insight software.

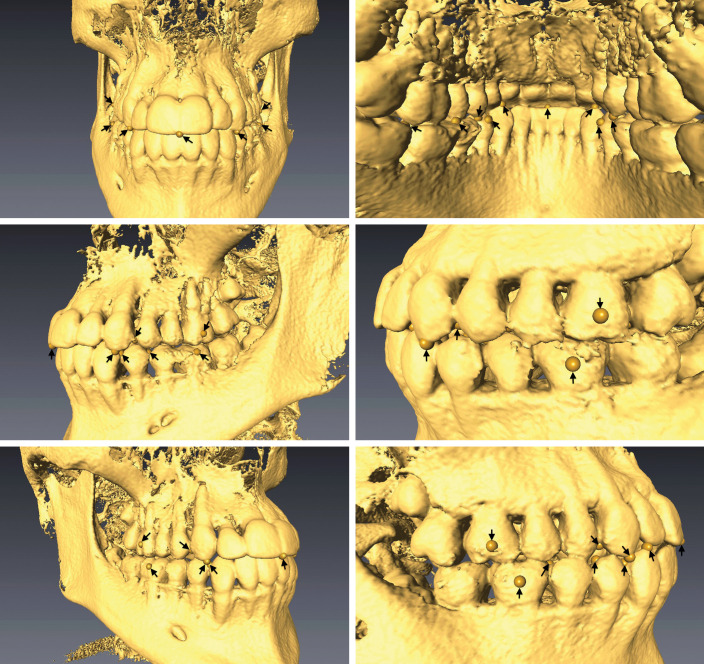

CBCT scans were taken using an I-Cat at 120 kVp, 7 mAs, and 8.9 seconds image timing. Images were taken in large view at 0.3 voxel size. Images were then converted to (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format and analyzed using the Avizo software (standard edition version 6.0, Mercury Computer System Inc, Chelmsford, Mass). In order to locate the required landmarks on the images, 3D visualization using Isosurface function set at a 600 to −700 threshold dependent on the patient's image, and CT slice visualization using OrthoSlice function set at maximum width for contrast control and center value adjusted appropriately for each scan for the optimal perceptibility, were accomplished (Figure 2). Twenty-six landmarks were identified for each patient scan, and x, y, and z coordinates of each landmark were recorded. Measurement values were obtained by calculating the distances between the two corresponding landmarks' coordinates.

Figure 2.

Landmarks represented on 3D model obtained from CBCT scans from various views.

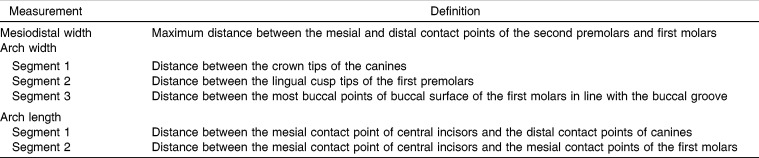

Eighteen different measurements, presented in Table 1, were selected based on the 26 landmarks in dentition. These measurements encompassed mesiodistal tooth width of molars and premolars and arch width and length in multiple segments of both the maxillary and mandibular arches (Figure 3). The same distances were measured in all 60 plaster models using a digital caliper. The required measurements were recorded to the nearest 0.01 mm by the examiner.

Table 1.

Measurement Definitions

Figure 3.

Landmarks and measurements indicated on 3D digital models.

All measurements were tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2010 software (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash), and statistical analyses were completed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics version 19, Armonk, NY). Paired t-test was used to analyze the mean differences between the measurements. Intraclass correlation coefficient was used to determine the agreement between the measurements. In order to determine the intraexaminer error of the measurements taken from the three different modalities, 10 patient records were selected and all 18 measurements were repeated three times by the same examiner, and then the correlations were computed using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

RESULTS

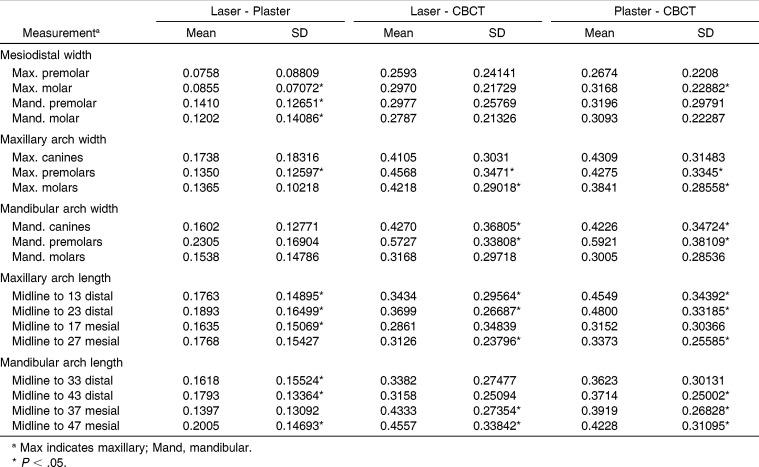

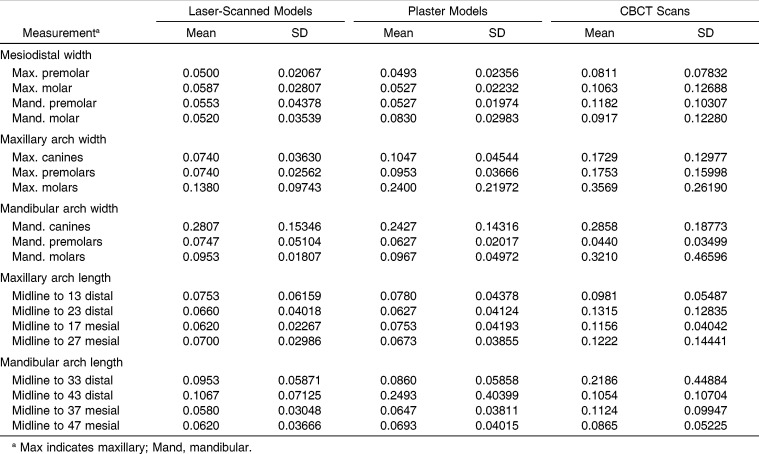

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics using paired-samples t-test comparing the plaster models, laser-scanned models, and CBCT scan models showing the mean differences between each other. Mean differences between the laser-scanned models and plaster models are ≤0.23 ± 0.169 mm with 90% of the mean differences less than 0.20 mm compared to the mean differences found between the laser-scanned models and CBCT scans at ≤0.57 ± 0.338 mm, where all values were ≤0.50 mm except the mandibular interpremolar distance. Mean differences between the plaster models and CBCT scans were similar to the results found between the laser-scanned models and CBCT scans. The highest mean difference was again found in mandibular interpremolar distance of 0.59 ± 0.381 mm, and all other mean differences were less than 0.50 mm. It is important to note that the mandibular interpremolar distance measurements exhibited the highest mean difference and significantly high variation in its set of values for all three comparison groups: 0.23 ± 0.169 mm for laser-scanned models and plaster models, 0.57 ± 0.338 mm for laser-scanned models and CBCT scans, and 0.59 ± 0.381 mm for plaster models and CBCT scans. P values presented that 29 of 54 measurement differences exhibited statistically significant differences (α < .05).

Table 2.

Paired Samples t-test: Mean Differences (in mm) With Standard Deviations (SD) for the Measurements Made on Laser-scanned Models, Plaster Models, and Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Scans (n = 60)

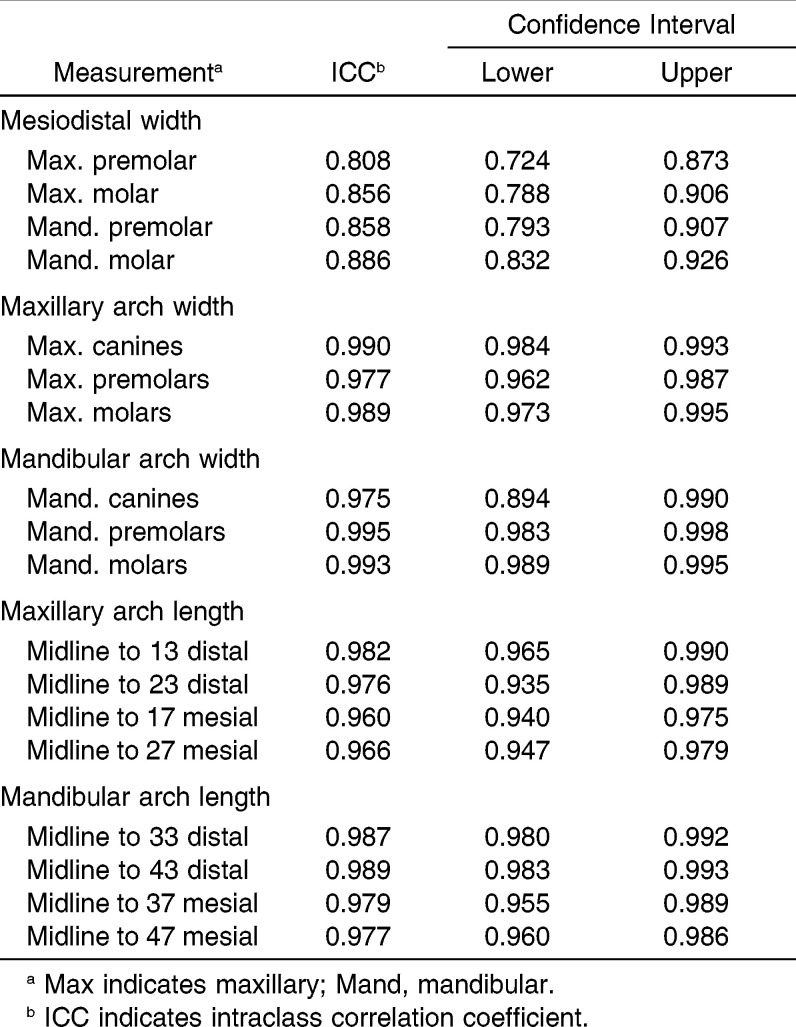

Evaluation of agreement among the laser-scanned digital models, plaster models, and CBCT scans using ICC is presented in Table 3. Mesiodistal width measurements presented relatively lower agreement when compared to other measurement parameters, ranging from 0.808 to 0.886. The lowest agreement among the three diagnostic record modalities was found in mesiodistal width of maxillary premolar at 0.808. Generally, both maxillary and mandibular arch width and length parameters exhibited excellent agreement at ≥0.960. Among the arch width and length measurements, half of the calculated ICC values were lower than 0.980, ranging from 0.960 to 9.979, while the other half ranged from 0.982 to 9.995. The highest agreement was found in mandibular arch width using mandibular premolars at 0.995.

Table 3.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient for the Agreement of Measurements Made on Plaster Models, Laser-scanned Models, and Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Scans

Table 4.

Intraexaminer Mean Differences (in mm) of Repeated Measurements Using Laser-scanned Models, Plaster Models, and Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT)

The intraexaminer differences, as shown in Table 4 ranged from 0.05 ± 0.021 mm to 0.28 ± 0.153 mm for laser-scanned models, from 0.05 ± 0.024 mm to 0.24 ± 0.143 mm for plaster models, and from 0.04 ± 0.035 mm to 0.36 ± 0.262 mm for CBCT scans.

DISCUSSION

Results of paired-samples t-test suggest that the discrepancy between the measurements acquired from the laser-scanned models and from the plaster models is sufficiently low to be clinically acceptable. All mean differences were well below the clinically significant difference of 0.3 mm for orthodontic purposes as suggested by Hirogaki et al.9 and were also significantly lower than the clinically relevant threshold difference of 0.5 mm as suggested by Luu et al.10 Keating et al.5 reported a range of absolute measurement differences between the plaster and virtual model measurements of 0.10 mm to 0.19 mm, which closely coincides with the range we found of 0.08 mm to 0.23 mm. ICC results also demonstrate an excellent agreement among the plaster models, CBCT scans, and laser-scanned digital models (≥0.808). Both results support the accuracy of the laser-scanned models, which provide clinicians with another modality for diagnostic purposes. Compared to the traditional plaster models, the laser-scanned models require less space and simultaneously allow for easy and convenient access to retrieve the models for study and treatment planning.

The mean difference calculated for the measurements of mandibular arch width using the mandibular premolar landmarks is distinguishably high compared to other mean differences, despite the fact that mandibular arch width measurement distance is considerably lower than other arch width and length measurement distances. We hypothesize that this may be due to the relatively high intraexaminer error that is present in locating the landmark on the first premolar lingual cusp compared to other landmarks because the lowest ICC value observed in both the laser-scanned models and plaster models was both found to be the measurement of mandibular arch width using the landmarks on premolars. Nevertheless, the overall intraexaminer error of the measurements evaluated in this study is relatively small with the lowest ICC value being 0.953 and the highest intraexaminer difference (0.36 mm) substantially lower than the 0.5 mm threshold, suggesting a difference that is clinically not significant. This is consistent with previous studies.2,3,10,11

Mean differences when comparing laser-scanned digital models and plaster models to the CBCT scans were higher than those between the laser-scanned models and plaster models. This was expected because CBCT is a direct imaging technique, thereby effectively eliminating the errors that may arise from the alginate impression and plaster model production stage. Three studies11–13 selected by Luu et al.,10 comparing the CBCT and plaster models, exhibited noticeably lower discrepancy than the results presented in this study; however, they reported that two of the studies12,13 used CBCT capturing images of impressions instead of direct imaging technique, thus not accounting for the possible errors that may have resulted during the process of making impression and plaster models. However, it is important to note that despite the relatively high mean differences, all mean differences found between the laser-scanned models and plaster models to CBCT scans were below the clinically relevant threshold of 0.5 mm,10 with the exception of two mandibular interpremolar measurements. Furthermore, most of the mean differences between the plaster models and laser-scanned models were within 0.3 mm of the mean differences between the laser-scanned models and the CBCT scans. Thus, we can safely assume that these discrepancies in mean differences are not clinically significant. Generally, excellent agreement existed among the laser-scanned models, plaster models, and CBCT scans.

This result coincides with the excellent agreement found in the arch width and length measurements and strong agreement in mesiodistal width measurements between the plaster models and 3D-based dental measurement program using CT scans as reported by El-Zanaty et al.11 Generally, the correlations found in mesiodistal width, especially that of maxillary premolar, were relatively lower than the arch length and width measurements, and this result is supported by the similar result found by Luu et al.10 Luu et al.10 observed that correlation of CBCT models compared with plaster models was relatively poor for maxillary premolar and mandibular incisor mesiodistal width, while other mesiodistal width measurements exhibited moderate correlation and better correlations found in arch perimeter measures. Although more than half of the measurements exhibited statistically significant differences, small mean differences in the measurements and excellent agreement among the techniques suggest that these statistically significant differences do not translate to clinical significance. This further supports that 3D digital models obtained using laser scanner demonstrate high accuracy that is comparable to CBCT technology, which coincides with the study by Tarazona et al.14 It is important to note that although the study done by Tarazona et al.14 used the software that separates the upper and lower arches in evaluating CBCT images, which was not done in this study since the software used is not appropriately equipped to separate both arches. However, this study also incorporated a clinical scenario where arch dimensions could be measured on unaltered CBCT images. The similar results of both studies indicate that the impact this difference in method had on the result is clinically negligible. Lastly, further research is required to determine whether this finding translates to the accuracy of a new software feature capable of integrating CBCT scans with laser-scanned models.

Although laser-scanned models are a clinically acceptable diagnostic record, there are some limitations in the practical application of the 3D laser scanner in an orthodontic setting compared to the traditional plaster models, such as the relatively slow and tedious process of scanning each impression or plaster model and a relatively steep learning curve of proprietary software. Furthermore, Kau et al.15 present a strong advantage of CBCT technology over the digital models in offering various diagnostic information such as bone levels, root positions, and temporomandibular joint status that are not provided by the digital models. Kau et al.15 also suggest the diagnostic usefulness of CBCT images are useful in assessing. unerupted tooth position and supernumerary teeth. In some orthodontic cases, clinicians make the transition from CBCT to scanned digital models as diagnostic record. For example, CBCT images may be required to assess the unerupted teeth at first, but the case can progress to the point that it no longer warrants the usage of CBCT and can be replaced by the use of laser-scanned digital models. In such cases, clinicians can be assured that the initial measurements done on CBCT is highly correlated to the measurements done on the digital models. This would prevent clinicians doing repeatable measurements using two systems. In summary, the selection of the diagnostic record method by the clinician will ultimately depend heavily both on the clinical situation and economic factors. Further research is needed to study other clinically relevant dental analyses, such as Bolton analysis, comparing laser-scanned models to CBCT and plaster models to provide clinicians with additional information with respect to the selection of alternative diagnostic records.

CONCLUSIONS

Plaster models, CBCT models, and laser-scanned models are three different diagnostic records, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

The present results show that the laser-scanned models are highly accurate to plaster models and CBCT scans.

The accuracy of laser-scanned models provides general clinicians an alternative to plaster models and CBCT reconstructions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leifert MF, Leifert MM, Efstratiadis SS, Cangialosi TJ. Comparison of space analysis evaluations with digital models and plaster dental casts. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:16.e1–4; discussion 16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens DR, Flores-Mir C, Nebbe B, Raboud DW, Heo G, Major PW. Validity, reliability and reproducibility of plaster vs digital study casts: comparison of peer assessment rating and Bolton analysis and their constituent measurements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quimby ML, Vig KWL, Rashid RG, Firestone AR. The accuracy and reliability of measurements made on computer-based digital models. Angle Orthod. 2004;74:298–303. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2004)074<0298:TAAROM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whetten JL, Willamson PC, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Major PW. Variations in orthodontic treatment planning decisions of Class II patients between virtual 3-dimensional models and traditional plaster study models. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keating AP, Knox J, Bibb R, Zhurov Al. A comparison of plaster, digital and reconstructed study model accuracy. J Orthod. 2008;35:191–201. doi: 10.1179/146531207225022626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mah JK, Huang JC, Choo H. Practical applications of cone-beam computed tomography in orthodontics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(suppl 3):7S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagravère MO, Carey J, Toogood RW, Major PW. Three-dimensional accuracy of measurements made with software on cone-beam computed tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapila S, Conley RS, Harrell WE., Jr The current status of cone beam computed tomography imaging in orthodontics. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011;40:24–34. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/12615645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirogaki Y, Sohmura T, Satoh H, Takahashi J, Takada K. Complete 3-D reconstruction of dental cast shape using perceptual grouping. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:1093–1101. doi: 10.1109/42.959306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luu NS, Nikolcheva LG, Retrouvey JM, et al. Linear measurements using virtual study models. Angle Orthod. 2012;82:1098–1106. doi: 10.2319/110311-681.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Zanaty HM, El-Beialy AR, Abou El-Ezz AM, Attia KH, El-Bialy AR, Mostafa YA. Three-dimensional dental measurements: an alternative to plaster models. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naidu D, Scott J, Ong D, Ho CT. Validity, reliability, and reproducibility of three methods used to measure tooth widths for Bolton analyses. Aust Orthod J. 2009;25:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe-Kanno GA, Abrão J, Miasiro Junior H, Sánchez-Ayala A, Lagravère MO. Reproducibility, reliability and validity of measurements obtained from Cecile3 digital models. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:288–295. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarazona B, Llamas JM, Cibrian R, Gandia JL, Paredes V. A comparison between dental measurements taken from CBCT models and those taken from a Digital Method. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35:1–6. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kau CH, Littlefield J, Rainy N, Nguyen JT, Creed B. Evaluation of CBCT digital models and traditional models using the Little's Index. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:435–439. doi: 10.2319/083109-491.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]