Abstract

Background

Hospital capacity strain impacts quality of care and hospital throughput and may also impact the well being of clinical staff and teams as well as their ability to do their job. Institutions have implemented a wide array of tactics to help manage hospital capacity strain with variable success.

Objective

Through qualitative interviews, our study explored interventions used to address hospital capacity strain and the perceived impact of these interventions, as well as how hospital capacity strain impacts patients, the workforce, and other institutional priorities.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Qualitative study utilizing semi-structured interviews at 13 large urban academic medical centers across the USA from June 21, 2019, to August 22, 2019 (pre-COVID-19). Interviews were recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, coded, and then analyzed using a mixed inductive and deductive method at the semantic level.

Main Outcome Measures

Themes and subthemes of semi-structured interviews were identified.

Results

Twenty-nine hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders were interviewed. Across the 13 sites, a multitude of provider, care team, and institutional tactics were implemented with perceived variable success. While there was some agreement between hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders, there was also some disagreement about the perceived successes of the various tactics deployed. We found three main themes: (1) hospital capacity strain is complex and difficult to predict, (2) the interventions that were perceived to have worked the best when facing strain were to ensure appropriate resources; however, less costly solutions were often deployed and this may lead to unanticipated negative consequences, and (3) hospital capacity strain and the tactics deployed may negatively impact the workforce and can lead to conflict.

Conclusions

While institutions have employed many different tactics to manage hospital capacity strain and see this as a priority, tactics seen as having the highest yield are often not the first employed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07106-8.

BACKGROUND

Hospital capacity strain results when there is a mismatch between supply and demand on any resources a hospital uses to provide care (e.g., beds, nurses, physicians, equipment).1 This is often defined as increased bed demand relative to hospital bed or resource supply1 and has been shown to negatively impact patient care,1–7 increase costs,8 and disrupt patient flow.9–13 Large academic medical centers have been found to be at particular risk of having daily patient demand exceed supply14 and therefore often face capacity strain; this was further heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic.15,16

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement published the white paper “Achieving Hospital-Wide Patient Flow” that provides a framework for hospitals to improve hospital-wide patient flow through the framework of “the right care, in the right place, at the right time.”14 Numerous specific interventions to manage capacity strain and optimize patient flow have been described in the literature, including strategies that focus on earlier discharges, huddles, and reducing unnecessary hospital days.17–21 It is clear that hospital flow is of strategic importance to many hospital systems; however, the perceived impact of the various strategies has not been well studied.

To better understand the experience of hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders, we utilized qualitative methods to explore interventions used to address hospital capacity strain and the perceived impact of these interventions, as well as how hospital capacity strain impacts patients, the workforce, and other institutional priorities.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted semi-structured interviews via telephone and through in-person meetings with hospital leaders and hospitalist leaders at large academic medical centers to understand the strategies they utilize to combat hospital capacity strain. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB), University of Colorado, Aurora, reviewed and approved the study. Interviews were conducted from June 21, 2019, to August 22, 2019.

Setting and Participants

Interviews were conducted with participants from 13 academic medical centers. Academic medical centers were chosen for this study as they may be more likely to experience hospital capacity strain.14 To select sites, stratified purposeful expert sampling was performed after creating a comprehensive list of US medical schools along with their respective hospitals, identifying those that had over 200 beds and had hospital medicine groups (sections or divisions). We included hospitals from all regions as grouped by American Hospital Association (AHA) Regions22 and then combined these into larger regions for reporting to ensure anonymity.

We included both hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders as participants to ensure diverse perspectives were included given the focus of this work impacts both groups of leaders and it has also been suggested that alignment between medical staff and executive leaders is needed in order to build successful patient flow initiatives.14 We hypothesized that the perspectives might be different and important to explore. Hospitalist leaders were leaders in their hospital medicine group who had knowledge of and led initiatives related to managing hospital capacity strain and hospitalist operations such as staffing and service planning and similarly for hospital leaders except that their role was focused on hospital flow. A convenience sample of hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders was selected from the list of hospitals meeting inclusion criteria. When contacted, individuals were asked if their institution faced hospital capacity strain, whether they were interested in participating, and whether they felt they were the appropriate contact for their institution. If not, we asked for suggested participants at their respective site (snowball sampling). Only hospitals that stated they faced hospital capacity strain were included. Consent was performed during the in-person meeting or phone call and participants were provided the consent form prior to the consent discussion and interview.

Interview Guide

Semi-structured interviews with the hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders used open-ended questions to explore interventions used to address hospital capacity strain and the perceived impact of these interventions. Interviews typically lasted one hour.

Questions were derived through a literature review as well as hospitalist expertise and practical experience (collectively spanning more than four decades of experience in the field). Hospital capacity strain was defined as excess bed demand relative to hospital bed or resource supply.1,23 A broad definition of hospital capacity strain was utilized for this study as both space and staffing constraints may be encountered by hospitals facing hospital capacity strain. We utilized the job demand–resource model of burnout24 and the conceptual model for integrated approaches to the protection and promotion of worker health and safety by Sorensen et al. in hospital settings25 as the guiding models for this study, namely that workplace policies and practices can directly impact the workforce and enterprise outcomes.25 The full interview guides are available in Appendices 1 and 2.

Data Collection

Eligible participants were consented and interviewed by investigators (M.B., S.A., and N.V.). Interviews were conducted by S.A. and N.V. (each were in the process of pursuing doctorate-level degrees at the time of the study) with the assistance of a hospitalist physician with qualitative research experience (M.B.). Recruitment of participants was halted when no new codes or themes emerged during analysis.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Any identifiers inadvertently captured on the audio-files were removed during professional transcription. The interview transcripts were then supplemented with notes and observations by research personnel made during the interviews. After professional transcription, interviews were imported into the Dedoose qualitative software program.

Analysis

Coding for themes was conducted (S.A., N.V., A.K., S.A., K.B., M.K., M.D., L.M., and M.B.). Both inductive and deductive coding approaches were applied to identify themes hypothesized a priori as well as new themes emerging from the data. An initial codebook was developed a priori, with new codes added as interviews and analysis were conducted. To ensure consensus, research personnel met virtually as a group to code two interviews together. After individual coding for each transcript was completed by at least two researchers, researchers virtually met as a group to harmonize any code disagreements. An inter-rater agreement was not measured as consensus was found through discussion. A thematic analysis was conducted using a mixed inductive and deductive method at the semantic level.26 Coded transcripts were analyzed both within hospitalist leader and hospital leader roles and across roles to identify commonalities and differences. Member checking,27 a technique for exploring the credibility of results, did not yield additional significant revisions.

RESULTS

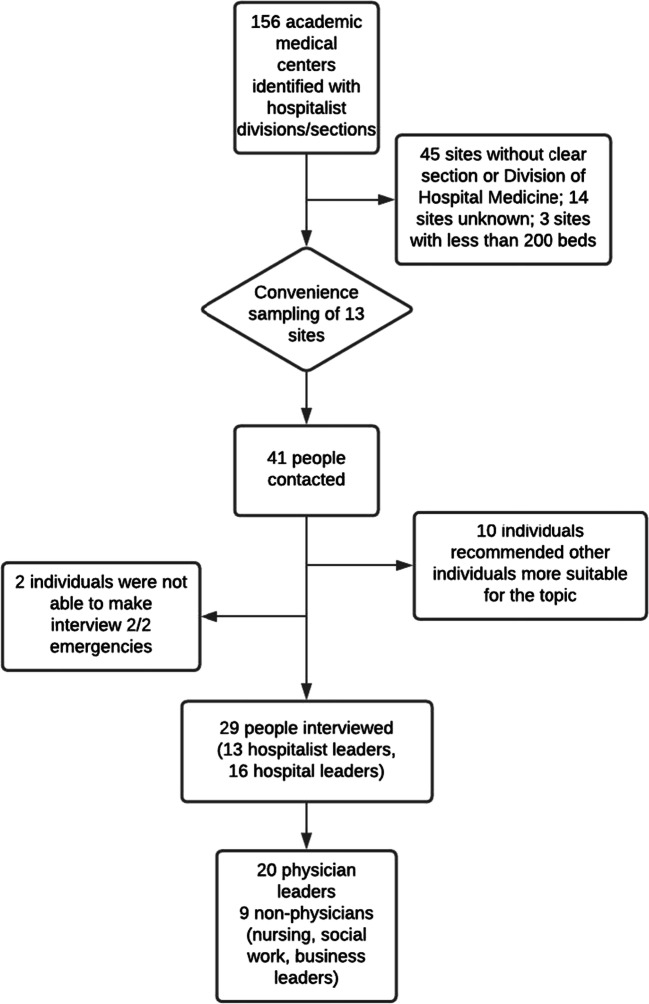

A total of 29 leaders participated in 27 interviews at a total of 13 large academic medical centers (all 200 beds or more). There were sites from all nine American Hospital Association Regions.28 Interviews were conducted with 13 hospitalist leaders and 16 hospital leaders and noted in Figure 1. All sites that were approached participated with at least one interview (100% site participation). All sites had an interview with a hospitalist leader and all but one site had a hospital leader. All interviews had one participant except one, which had three individuals from the same site and all were hospital leaders. Demographic data for the hospitals the participants were associated with are in Table 1. Specific roles of the respondents were omitted to ensure anonymity; however, high-level roles (physician, non-physician) are noted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Enrollment.

Table 1.

Demographics of Participating Hospitals

| Site | Region | Description | Bed capacity | Provider team caps* | Patient cap description | Utilize APPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Western | University quaternary referral center | > 500 | Yes | Varies based on team type | Yes |

| 2 | Southern | Safety net, county hospital, major referral center | > 500 | Yes | Soft cap—non-teaching teams go to 17 or 18 and then teaching teams with a cap of 15 to 17 | Yes |

| 3 | Eastern | University-affiliated, community hospital | < 500 | Yes | soft cap, 10 alone, 13 with APP fellow | Yes |

| 4 | Midwestern | Urban academic medical center, university-affiliated | > 500 | Yes | 15 patient touches per day (non-teaching), teaching averages 10 patients and caps consistent with ACGME rules | Yes |

| 5 | Eastern | Large academic, tertiary care, urban medical center | > 500 | Yes, depending on team type | Attendings do not have caps; house staff follow ACGME rules | Yes |

| 6 | Eastern | University-affiliated, quaternary referral center | > 500 | Yes, depending on team type | For teaching service only (cap of 8 in the ED) | No |

| 7 | Midwestern | University-affiliated academic institution, safety net hospital | > 500 | Yes, depending on team | Teaching service capped at 16, hospitalist team not capped | Yes |

| 8 | Western | University-affiliated, safety net hospital | < 500 | Yes | Resident services capped at 16 patients per team, direct care hospitalists are capped at 12 | Yes |

| 9 | Midwestern | Academic medical center, safety net | > 500 | Yes, depending on team type | Academic teams are capped at 15, soft caps for other teams at 15 | Yes |

| 10 | Southern | University; quaternary referral center | > 500 | No | N/A | Yes |

| 11 | Southern | University hospital; safety net | < 500 | Yes | Teaching 16; hospitalist plus 2 APPs 18 to 22 | Yes |

| 12 | Southern | University, partially state funded, quaternary referral center | > 500 | Yes | Teaching has cap of 12 but may extend; 16 soft cap, flex to 18 | Yes |

| 13 | Southern | Academic; safety net | > 500 | Yes | Non-teaching cap of 15 and 20 if with APP; Teaching team with caps of 18 | Yes |

Regions grouped by the American Hospital Association (AHA) Regions. https://www.ahvrp.org/sites/default/files/aha-regional-map.pdf (accessed January 31, 2021) and then combined into larger regions. Regions 1–3 are referred to as the eastern region, 4 and 7 southern, 5 and 6 midwestern, and 8 and 9 western regions

APP Advanced Practice Provider, ACGME Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ED Emergency Department, N/A not applicable

*Cap definition: there is maximum number of patients a provider will see in a day/shift

Across the 13 sites studied, a multitude of provider, care team, and institutional tactics were implemented with perceived variable success (Tables 2 and 3). The solutions that were most highly recommended were (1) ensuring appropriate staffing, (2) having proactive data-driven approaches which were felt to be more helpful than multiple pages and meetings, (3) planning for discharge at the time of admission, (4) establishing protocols and plans to manage high-capacity days, and (5) identifying barriers to discharge with a multidisciplinary approach. While there was some agreement between hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders, there was also some disagreement about the perceived successes of the various tactics deployed. Interventions that overall were perceived as positive were caps on patient loads, huddles, multidisciplinary rounds, and triagist roles. On-call providers received mixed reviews. Overall negative interventions were discharge lounges, flexing providers from teaching teams to non-teaching teams, and care escalation initiatives. Hospitalist leaders often felt multiple huddles and new care areas (i.e., surge spaces or adapting non-care areas into areas where patient care is provided) were interventions that were not perceived as successful in helping with capacity strain, whereas hospital leaders felt that designated discharge nurses, using existing staff and resources without adding staff or resources as census rises, and care escalation processes were not perceived as successful. Hospital leaders had mixed reviews on post-acute care contracts, predictive modeling, discharge lounges, and huddles. A coding summary for hospitalist and hospital leaders is provided in Appendix 3.

Table 2.

Provider Interventions to Manage Hospital Capacity Strain

| Interventions | Perceptions | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Provider team adaptations | ||

|

Team caps (i.e., maximum number of patients on a given team), safety thresholds (i.e., targets for teams, not necessarily caps) Census sharing agreement (ways that teams may share patients, e.g., cardiology takes certain patients) Level loading (i.e. patients distributed across a variety of teams such that no one team is given more patients than another) Emergency census protocol/back up plans/surge coverage/moonlighters Private patients (i.e., attending patients that are separate from teaching teams); addition of non-teaching teams |

Caps protect providers, patients with safe patient numbers Interventions can drive up costs Discontinuity can occur with moonlighting or unexpected staffing needs which can lead to increased length of stay, readmissions, and decreased patient satisfaction Lower census allows for more time spent with patients |

And even with that, we have a soft cap, wherein we don’t give two or three more patients than they are supposed to see for the day. This is being done to prevent burnout, and also to protect the patients to ensure the quality of care is not compromised. So what this does to us is this will drive up our moonlighting cost. Every time we have a higher census, we have to bring in moonlighters. So, that will drive up cost for the division and this is like unplanned cost. [moonlighting] …it leads to discontinuity in care with the moonlighters who are coming in and probably coming in for a day or two, and they are not here on a regular cycle. So the discontinuity again leads to a lot of things, including increased length of stay, increased readmissions, and also poor patient satisfaction. (Participant 103b, hospitalist leader) |

| Provider rounding styles adaptations | ||

|

Discharges first/discharge by “X” time Conditional discharges (discharge once “X” occurs) |

May lead to longer lengths of stay Hard to sustain Good for certain patient types |

Well, we’ve done a few things like any other hospital, like discharge 2 patients by 2 pm or 2 patients by 12 pm initiative. I don’t think they have any great impact, because that’s culture change, and it has to happen over time. And if you expect something to change only on high capacity, it doesn’t work; it usually won’t work for this type of intervention. (Participant 103b, hospitalist leader) I do go on a working philosophy that you’re going to get to a saturation point for discharge before noon, because if you’re going to be able to discharge before noon, say, greater than 30%, my argument is your excess days are probably too high. (Participant 105a, hospital leader) |

| Increasing APP support | ||

| Increasing APP roles on teams |

Challenges when integrating APPs into teams (at first) Lots of gains with APPs |

We’re relatively new to using nurse practitioners on our service. We’ve tried a few things to figure out what’s the best way to have the nurse practitioners help us with these—these flow surges, like focus on discharges and taking care of patients who are expected to go home that day or before noon. We’ve tried to have them pitch in with complex discharge, a lot of things along those lines. I think the balancing thing here is that we want the job to be satisfying for the nurse practitioners. So having them focus on just one specific type of patient, ultimately the feedback we got from them was this isn’t what I signed up for. (Participant108b, hospitalist leader) |

| Novel team types | ||

|

Social admitting team Barriers team Long stay units Complex discharge team Transitional care unit |

May be able to increase the census for providers with patients who are less acutely medically complex Large discharge barrier for patients; teams can get really good at this type of care |

We have like a sizable population of social admissions and geriatric/psychiatric patients. We try to cohort those patients on to one provider and increase the census on this provider. We are a little methodical on how we assign patients—one provider does not get all the sick patients in the hospital. That way everybody has an equal opportunity to work on discharges and get people out. (Participant 103b, hospitalist leader) One of the biggest discharge barriers certainly is housing and security. Part of the reason our census is so high at baseline is because we probably have about 15% of our service consists of patients who do not actually require hospital level care. Some of them are patients that they need their six weeks of intravenous antibiotics but they’re homeless and they don’t have anywhere to go. A larger proportion of them are patients who are cognitively impaired either due to dementia or psychosis or some other reason, and they don’t have a surrogate decision-maker, and/or they’re homeless and so they came into the hospital for some acute reason, but now they have nowhere to go. (Participant 108b, hospitalist leader) |

|

Innovative care models Admitter rounder models Comprehensivist/extensivist Low-risk chest pain Hospital-at-home |

Novel care models can help with specific populations Can gain efficiency Costs money and the financial gains may be more indirect |

It is an extensivist model where you have a certain cohort of patients that we found out were responsible for the large number of admissions, and we do have a special team that will see them in the hospital when they’re in the hospital and then see them in the clinic when they’re out of the hospital and develop care plans for those patients to help make the hospitalizations consistent if they’re coming in for similar reasons. (Participant 104b, hospitalist leader) We are partnering with some local organizations and other healthcare providers to work on what we—it is a hospital at home model to try to have some patients who can be safely managed at home. We’ve also done work in expanding our urgent care, trying to divert patients from getting so sick and need to be in the hospital. (Participant 106a, hospital leader) |

APP Advanced Practice Provider

Table 3.

Hospital and Care Team-Based Interventions for Hospital Capacity Strain

| Interventions | Perceptions | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Geographically based solutions | ||

|

Discharge lounge—place where patients will move to from the inpatient side while awaiting rides, discharge paperwork Unit based care teams—geographically based teams; team-based models for care management Hallway beds/flex care units—care areas that are set up/staffed that may be in addition to typical patient beds/care areas Observation unit (ED based), clinical decision units, holding units—areas where shorter stay patients may be cared for |

Need buy-in from nurses and physicians; acuity too high for patients to be appropriate for discharge lounge Improved length of stay; difficult when at high capacity; a lot of challenges to maintaining geography Lack of team structures for hallway beds/flex care units; not perceived as patient centered; more patients and not necessarily more staff/providers; sometimes helpful to keep patients moving; unclear impact on outcomes |

We have done a discharge lounge, although it has not been extremely successful. I think there’s some reluctancy on the part of nursing in terms of discharging those patients to the discharge lounge. There’s not a lot of buy-in from the physician standpoint. Many believe that the acuity of the patients are just too high for that area. So, I think some of the perception, they’re just not comfortable with the concept. (Participant 109a, hospital leader) So from the provider angle for our service, the part that makes it challenging for us is the difficulty to be at two different places at the same time. So, if you have patients that are bedded in the emergency department and then they’re assigned to a physician who is upstairs on their geographic floor rounding, it’s—innately inefficient from the standpoint that for them to take care of the bedded patient at ER, they have to physically go off their floor to go do that. (Participant 110b, hospitalist leader) |

| Capacity management | ||

|

Capacity management team and leadership, capacity plans, action teams, bed management center Triagist, ED-based team—team housed in the emergency department that will provide consults or care for patients who may stay in the ED secondary to a lack of beds; triagist helps with bed management and assignment of care teams |

Have overview of big picture; commitment to standard operating procedures Ensures patient flow happens more seamlessly; allows for ED discharges/ED care; allows other teams to focus on patient care |

We do have capacity surge for our service based upon a certain census that our service hits, will initiate a call in for a doctor to come in to help offset volume. And that’s a pretty recent development. We started that about a year-ago and I think that has worked pretty well for its intentional purposes. The rules of the game is at 6 o’clock in the morning we have a clinical care coordinator that comes in, they help to determine, “Okay, what’s the census of our service,” and then by 7 o’clock—it’s—within one hour determine, “Hey, do we need to initiate surge capacity or not?”. And so, we do—do that for both hospital sites at [de-identified] for university hospital and then we also have a smaller hospital site nearby called [de-identified]. And both of them have surge capacity, you know, doctors at “risk” to get called in. (Participant 110b, hospitalist leader) We have a triagist role that’s done by our advanced practitioners who, essentially have the big picture of what the numbers look like, what the numbers look like for each team, and transfer management is done by that provider—even on a very busy day, an individual team is able to just focus on their patient care with the knowledge and understanding, that if they’re needed then someone will reach out to them, but if they’re not needed, it doesn’t matter how light, or how slow, or how full, or how busy, the census is across the entire division across the hospital because this is all managed by a person who is not doing clinical work, who just has spreadsheets, and numbers, and pagers in front of them. (Participant 101b, hospitalist leader) |

| Proactive planning/dashboards | ||

|

Proactive financial planning, care planning, and addressing barriers to discharge—planning in advance, from the time of admission Predictive analytics—utilizing data to predict inflow and outflow of the hospital Dashboards, track boards, daily reports—techniques to relay information on capacity, discharges Smoothing admissions—developing plans around operating rooms and other expected admissions in order to prevent admission stacking |

Ensuring insurance is correct is key; preparing discharge paperwork, medical equipment is important to do in advance Predictive accuracy an issue Good for building alignment; electronic dashboards take time to build; paper dashboards less effective than electronic Taking advantage of times when there are less patients/open operating rooms or procedural areas |

The idea is to identify barriers to discharge and alleviating these barriers, and preferably, doing all of this the day before discharge and making sure that if there are any barriers, that those are being addressed, the families being notified of the patient’s anticipated date of discharge, and then walking through what barriers can be accomplished today to get the patient out. (Participant 110a, hospital leader) We have what we call our [de-identified] dashboard and our [de-identified] tracker just so that we’re reviewing our metrics on a monthly basis across the state and then for any metric where they may be in red, then they’re expected to come up with countermeasures and report out on their countermeasures every month. And now, we’re taking that one step further, and we’re developing a unit-specific dashboard so that each individual, case manager and social work team can see what their performance looks like and not to necessarily be a comparison because we know that their populations are different, their lengths of stays are different, etcetera, but just for them to have an opportunity to actually see their own data. I mean, that’s kind of meaningless to them unless they can tie it back to the exact work that they’re doing, so that’s what we’re trying to do (Participant 109a, hospital leader) |

| Communications | ||

|

Huddle/calls around discharges—brief team meetings to address discharge barriers and discharge plans Communications such as emails, pages, and texts—sent to update care team members around capacity and to request early discharges and or care escalations Electronic communication tools—technology built to enhance multidisciplinary care team communication Multidisciplinary care team meetings—typically scheduled meetings during the weekday to plan patient care |

Difficulty with providers attending huddles consistently; takes away from education and from patient care; perceived lack of value, lack of accountability, not everyone shows up; too long; should be concise; key people should be there Often redundant communications and a lot of them |

You spend a lot of time talking about prompt discharge, we have a 3:00 pm huddle that sort of is in the middle of some other potential activities. It definitely detracts and distracts from other things people would like to be doing, such as teaching. It can distract from taking good care of patients, when you have a huddle to go to. So, yeah, I do think that the—the emphasis on the activities can get in the way of the other activities, and other, you know, things that the hospitalists are doing. (Participant 105b, hospitalist leader) The thing that we do have that I think is effective but I just couldn’t tell you how effective it is, is we have…a HIPAA-compliant text messaging system. And so, we’re able to loop in nursing, rehab, pharmacy all on the same group text just to review what the care plan is. (Participant 111b, hospitalist leader) |

| Regional plans | ||

|

Regional wide plans for moving patients to other hospitals—utilizing system approaches to managing patient volumes across multiple hospitals Post-acute care contracts (hospital paying when patients do not have funding)—hospital will develop contracts to help facilitate patient movement to next care location (e.g., subacute nursing facility) when patient may not have funding source and thus hospital covers cost |

Patients are moved from one hospital in the system to another; may be challenging for patients and their families |

We have contracts with a long-term acute care hospital, with a skilled nursing facility. We have a good relationship with an acute rehab for unfunded patients and with residential care facilities. So, we will pay for them while their Medicaid is in process so they don’t live in the hospital. (Participant 112a, hospital leader) One of the things that we’ll do when it’s appropriate is identify patients who have not yet been admitted to go to one of our network hospitals, which overall works well. It can be a patient dissatisfier, but when it works well it works well, but it does require a lot of coordination and upfront identification of patients who would be eligible for a transfer before ultimately being admitted here. (Participant 111c, hospital leader) |

| Preventing readmissions | ||

|

Post discharge phone calls—calls to help ensure higher risk patients do not have any unexpected issues Medications in hand—program to ensure patients discharge with their medications they need in hopes of preventing readmissions |

Disease-focused interventions and focusing on high-risk patients. Patients seem to engage with post discharge calls and have better experience. Ensuring patients have their medications at discharge has decreased readmissions | Just from a readmission standpoint, we partner with a vendor and all our patients who are discharged inpatient or observation, outpatient in a bed, they receive a follow-up phone call 48 hours after discharge, and it goes through, you know, were you able to get your medications, did you understand your discharge instructions, could you get in for a follow-up appointment? There’s five or six different questions. And then depending on how the patient answers the question, we have transitional case managers that will follow-up with patients and intervene and help them with problem solving. So that’s been really successful. We found that those patients that actually engage with a call had a higher patient experience score and a lower readmission risk. (Participant 109a, hospital leader) |

| Nursing | ||

| Discharge nurse—nurse specializing in care of discharging patients | Failed on teaching teams; takes strong leadership | We do that actually just for the hospitalist teams. It was tried on teaching and I think it failed. And I think that there were a couple of reasons why it failed. One is they didn’t have a strong leader advocate for the project. So, it was kind of like, “Okay, we’re doing this, but what exactly are we doing?” And then additionally, the way it was done for the teaching service because teaching services are generally a little less efficient and, you know, they take just longer to round where you talk outside the room and then you go in the patient room and you talk again on most of the services and what they did when they did the pilot is they actually put one attending nurse with two teams. So, the attending nurse would join the teaching team, I think, on the post-call day. And they wouldn’t have necessarily rounded with the team the day before. And then the team wasn’t quite sure what the nurse’s role was. So, there was kind of role definition issues. There was maybe a little bit of undermining, and that the attending our end, that’s what we call them, the discharge nurse wasn’t following with the team daily. And so, to keep up on all those patients was a little trickier. And then there was also a concern that “Hey, should an intern be able to draft this.” Is this taking away from their educational thought? (Participant 104b, hospitalist leader) |

ED Emergency Department, ER Emergency Room

Themes

Three main themes as elucidated from hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders emerged and are shown below along with the subthemes and verbatim exemplar quotes.

Theme 1: Hospital capacity strain is complex and difficult to predict

Hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders agree that drivers of hospital capacity are complex and difficult to predict, which often leads to conflict and the sense of constant “churn.” Because of the lack of predictability, staffing concerns often lag.

It is like the spigot game…you got one spigot that’s coming out, you put a finger in that to stop it, then also there's the other spigot that now comes out spraying water...it’s like anything else that you solve one problem, careful you may open up a new problem to be encountered. (Participant 110b, hospitalist leader)

Theme 2: The interventions that were perceived to have worked the best when facing strain were to ensure appropriate resources; however, less costly solutions were often deployed and this may lead to unanticipated negative consequences

Both leader types recognized that the capacity crisis was almost daily, caused stress, and that resources often lagged. Because drivers of hospital capacity are complex and difficult to predict, resource allocation can be challenging. Resources and time were felt to be very valuable in managing hospital capacity strain; however, they often lagged or were not deployed in response to the current crisis.

Staffing

Participants noted the need to ensure enough providers for volume, often using a formula based on census with the goal of keeping numbers stable across teams/providers and with a consistent workload. It was perceived as stressful for providers when the hospital became progressively busier with no maximum in sight. Solutions often fell into (1) asking providers on service to take on more patients in a day, (2) adding staff like a backup/on-call/jeopardy system (perceived as challenging because this system is often used for providers who call in sick), or (3) using moonlighters to add staff when needed. The biggest challenges were often noted to be financial (balancing being overstaffed versus understaffed) and accurate projections of volume to know when to staff up because projections are difficult in a constantly changing environment. In addition, some solutions such as moonlighters were perceived as costly and potentially unsafe due to discontinuity of care and there were essentially thresholds at which you can run out of providers to pick up the extra work.

It is ideal to staff at a level where it is just built-in that there is some ability to flex up. There’s really no way to accurately model and predict volume if you’re a large academic medical center treating all variety of patients, you can’t control, if you have an open emergency room, you have a large network, you’re taking referrals, it’s very, very difficult to control volume, so you have to accommodate it. The best way to do it is to sort of staff to a level that allows for some flexibility, to flex up to accommodate sort of maybe 90% of the variation. (Participant 106b, hospitalist leader)

Participants noted that increasing providers, calling in float pool nurses, and adding beds to handle increases in volume does not ensure that the other necessary resources for delivering patient care are available such as care management, social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, respiratory therapy, and imaging.

The high-capacity situation has created busy days, seeing larger numbers of patients, which it is just physically and cognitively mentally harder, and potentially creates more frustrations as well because all of the available resources in the hospital can get soaked up, and the things that normally happen quickly happen more slowly, which then creates a vicious cycle… it creates inefficiencies. (Participant 101b, hospitalist leader)

Time

Time is a resource in short supply in a high-capacity strain environment. Those interviewed reflected that it takes time to decompress the hospital after patient volume decreases. In addition, there is not enough time in a day for providers to complete all their tasks if caring for a large number of patients, with institutional initiatives seeming to directly compete with each other in order to finish everything before noon (discharges, calling consultants, multidisciplinary meetings).

The other direct impact obviously is if you are doing QI [quality improvement] or clinical research that relies heavily on workflows being in a certain way, and every time there is a stress on the health system to discharge patients early or keep the flow going, these workflows might be altered and again, would impact your studies... The other side of it is how the human factors the burnout and the constant request for moonlighting, like a lot of people in good faith want to moonlight to help other colleagues, but that time is actually coming out of their research and personal time. (Participant 102b, hospitalist leader)

Unintended Consequences

Participants noted that some of the most commonly implemented initiatives can often have unintended consequences, including distracting from patient care, burnout, and delayed abilities to properly staff for patient care.

It was really just a very inefficient system that people would then try to cram and make work faster and better than they normally would, but something I think makes the providers feel nagged when everyone’s paging, they’re trying to see patients, and they’re running around the hospital trying to find this one patient that got tucked away somewhere in the back of the outpatient area here, and at the same time getting emailed and called and pages, asking if you can discharge people as quickly as possible. (Participant 101b, hospitalist leader)

Theme 3: When a hospital is facing hospital capacity strain, it negatively impacts the workforce and can lead to conflict

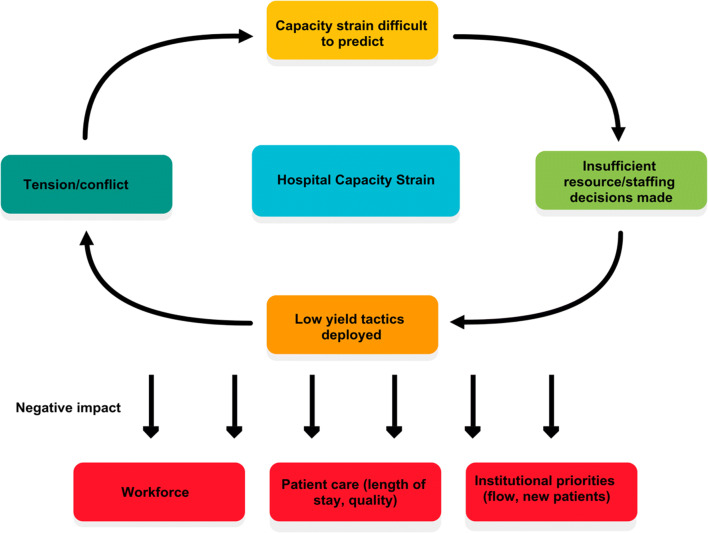

Hospital capacity strain was perceived to have negatively impacted patients, providers, and staff, and it was also noted to encroach upon other academic medical center missions such as education, research, innovation, and financial stability. Appendix 4 highlights these key subtheme areas by key stakeholder groups and core mission areas. Figure 2 is a conceptual model depicting the impact of hospital capacity strain on the workforce, the patients, and institutional priorities. Additional subthemes emerged and are shown below.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of impact of hospital capacity strain.

The tactics implemented to mitigate hospital capacity strain directly impacts the ability of providers to do their jobs

The many different initiatives that hospitals craft to mitigate hospital capacity strain can have a perceived negative impact on care team members’ abilities to do their jobs. Participants noted being pulled in many different directions and often bombarded with a wide array of communication tactics. This also limited the ability to do other academic work such as teaching.

Because you have a lot of patients and you’re concentrating on the difficult ones. But there could be ones that you know, instead of saying, “Oh, let’s wait until tomorrow,” if you would have had the chance to sort of circle back and evaluate throughout the day you might have been able to get them out that day. But because you’re working on other difficult patients or just the sheer number of patients, then you might not have had that chance to really pay attention closely to a patient. (Participant 112a, hospital leader)

Hospital capacity strain impacts the well being of providers

Hospital capacity strain and the tactics implemented were perceived to lead to increased stress and tension which places providers at increased risk of burnout.

Unfortunately, in the meantime, when you are outnumbered with patients, and finding it difficult to provide the type of care that our providers want to give, there is a long time before you can staff up appropriately to make sure you’re managing that well, and that puts a strain on people and their morale, and their sense of whether this position—this job is sustainable. (Participant 102b, hospitalist leader)

The tension between sufficient resources, the tactics deployed, and being able to do one’s job creates conflict

Conflict was perceived to be experienced when tactics to address hospital capacity strain were implemented without sufficient additional resources.

Years ago, before we had a true throughput surge plan, what the typical strategy was for someone in the ED to e-mail someone in hospital leadership, like the president, and say, “It’s crazy down here, can you get those guys upstairs to discharge?” It was very confrontational. (Participant 105b, hospitalist leader)

DISCUSSION

We found that hospital capacity strain was perceived to have wide-reaching impact at each of the participating sites. Participants from all institutions noted a continued struggle with how to manage hospital capacity strain and had implemented numerous measures with variable success. Both hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders felt that the most effective way to address strain is often through ensuring sufficient resources, particularly through staffing, but noted that it is often not the first intervention utilized. Instead, seemingly more cost neutral interventions (e.g., discharge lounge or huddles) are implemented first, even though most people interviewed felt they do not fix the problem and may lead to negative consequences and a repetitive cycle of lagging resources and stress.

There is limited literature about the impact of hospital capacity strain on the various stakeholders and key mission areas of academic medical centers. Some reports have highlighted the impact of hospital capacity strain on timeliness of discharge,29 length of stay,6,7 and quality of care1; however, this study highlights the consequences on the workforce with the words “churn,” “burnout,” and “conflict” frequently utilized when describing how the inpatient workforce manages hospital capacity strain. Clinician burnout is consequential not only for individual providers but also for health care systems, as it may lead to providers leaving the workforce,30–32 medical errors,33–37 and has been projected to cost $4.6 billion annually in the USA for burnout related to physicians.38

Hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders had differing opinions on the impact of the various initiatives aimed at improving patient flow and capacity. The perception of conflict was noted throughout the interviews. Workflows may differ for various roles, so an assessment of how these well-intentioned interventions may impact the workforce’s ability to get work done may be necessary as it was noted that some of the interventions could cause distractions and negatively impact patient care.

Some research has suggested that adequate staffing may lend itself to more expedited care and potential cost savings. Elliott et al. showed that increasing hospitalist workload is associated with clinically meaningful increases in length of stay and cost.39 Previous work by Michtalik et al. highlighted that having fixed census caps on teams decreased the odds of reporting unsafe census situations.40 Thus, while adequate staffing may require resources, these studies suggest that the cost may be offset through improved patient flow and improved patient safety. This study suggests that often hospitals employ less costly solutions to address hospital capacity strain; however, the reasons behind why hospital systems choose measures that are perceived to be less effective is unknown and could be a future area of study. Future work should focus on the economic impact of the various initiatives, in particular the impact of high patient census and increased workloads (and cognitive load) as well as interventions that may inadvertently result in provider distractions.

Our study has several strengths. We explored both the hospitalist leader and hospital leader perspectives to understand the impact of hospital capacity strain on key stakeholders and core mission areas as well as the impact of the various tactics deployed to manage strain. We included both perspectives given hospitalist leaders and hospital leaders might have distinct perspectives on the topic given different incentives, constraints, and resources available to respond to capacity strain situations. We also included a large number of institutions from a variety of geographic regions. This work adds to the understanding of which strategies have been deployed and the experiences with these initiatives. While several studies have shown the operational impact of hospital capacity strain (through increased length of stay and mortality), we believe this is one of the first to show the impact on the workforce (i.e., ability to do one’s job, conflict, well being), though there is increasing literature on how COVID-19 has strained clinical care teams.41

Our study also has some limitations. It involved large academic medical centers with greater than 200 beds and hospital medicine groups, and thus, our findings may not apply to smaller hospitals or non-academic medical centers or institutions without hospitalist groups. We interviewed two individuals (a hospitalist leader and hospital leader) at most institutions and thus our findings may not represent the beliefs of frontline workers, though many of the hospitalist leaders were also frontline clinicians. Hospital leaders that were interviewed also had a variety of roles some of which were hospitalists (i.e., hospitalists that led initiatives for the hospital) and thus some of the perspectives could have overlapped between the two groups. Lastly, this work covers hospital capacity situations that may differ from a crisis situation (e.g., COVID, mass casualty event) though likely with some overlapping components.

CONCLUSION

Across the 13 sites, a multitude of provider, care team, and institutional tactics were implemented with variable success. Hospital capacity strain was perceived as complex and difficult to predict with wide-reaching impact on patients, the workforce, and institutional priorities. While ensuring appropriate resources was felt to be key to managing hospital capacity strain, less costly solutions were perceived to be deployed that may result in further negative consequences and conflict.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 18 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

(DOCX 18 kb)

Funding

Sagarika Arogyaswamy, BA, was supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, Newgard CD, Guise JM. The Association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:686–96. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48:224–32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaieski DF, Agarwal AK, Mikkelsen ME, et al. The impact of ED crowding on early interventions and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:953–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, Kelley KM, Rzechula KH. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr, Viccellio P, Pines JM. The association between length of emergency department boarding and mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1324–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DF. Boarding inpatients in the emergency department increases discharged patient length of stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, Lee AJ, van Walraven C. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:127–33. doi: 10.1197/aemj.10.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foley M, Kifaieh N, Mallon WK. Financial impact of emergency department crowding. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:192–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGowan JE, Truwit JD, Cipriano P, et al. Operating room efficiency and hospital capacity: factors affecting operating room use during maximum hospital census. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:865–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Early discharge and its effect on ED length of stay and access block. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;178:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:186–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, Zeitz K. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28:164–70. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:664–9. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutherford PA, Anderson A, Kotagal UR, Luther K, Provost LP, Ryckman FC, Taylor J. Achieving hospital-Wide Patient Flow (Second edition) IHI White Paper Boston. Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowden K, Burnham EL, Keniston A, et al. Harnessing the power of hospitalists in operational disaster planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2732–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeley C, Jimenez J, Jackson H, et al. Staffing up for the surge: expanding the new york city public hospital workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:1426–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane M, Weinacker A, Arthofer R, et al. A multidisciplinary initiative to increase inpatient discharges before noon. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46:630–5. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel H, Yirdaw E, Yu A, et al. Improving early discharge using a team-based structure for discharge multidisciplinary rounds. Prof Case Manag. 2019;24:83–9. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Eid GR, Kaddoum R, Tamim H, Hitti EA. Improving hospital discharge time: a successful implementation of Six Sigma methodology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e633. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck MJ, Okerblom D, Kumar A, Bandyopadhyay S, Scalzi LV. Lean intervention improves patient discharge times, improves emergency department throughput and reduces congestion. Hosp Pract (1995) 2016;44:252–9. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1254559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562–6. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Hospital Association Regions American Hospital Association. Available at: https://wwwahvrporg/sites/default/files/aha-regional-mappdf. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 23.Kohn R, Harhay MO, Bayes B, et al. Ward capacity strain: a novel predictor of 30-day hospital readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1851–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4564-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen G, McLellan DL, Sabbath EL, et al. Integrating worksite health protection and health promotion: a conceptual model for intervention and research. Prev Med. 2016;91:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1802–11. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Hospital Association (AHA) Regions. https://wwwahvrporg/sites/default/files/aha-regional-mappdf. Accessed January 31, 2021.

- 29.Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13:816–22. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantenburg B, Luppa M, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Burnout among young physicians and its association with physicians’ wishes to leave: results of a survey in Saxony, Germany. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2016;11:2. doi: 10.1186/s12995-016-0091-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:851. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17:36–41. doi: 10.1370/afm.2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1317–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:203–12. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000281626.28363.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:784–90. doi: 10.7326/M18-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott DJ, Young RS, Brice J, Aguiar R, Kolm P. Effect of hospitalist workload on the quality and efficiency of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:786–93. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michtalik HJ, Pronovost PJ, Marsteller JA, Spetz J, Brotman DJ. Identifying potential predictors of a safe attending physician workload: a survey of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:644–6. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a new york city health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95:1136–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 18 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

(DOCX 18 kb)