Synthetic cathinones gained initial popularity on the illicit drug market as a result of attempts to evade legal restrictions on other commonly abused psychostimulants. A body of published research has determined that the psychopharmacology of the synthetic cathinone 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is comparable to cocaine and methamphetamine (METH). Few preclinical studies have systematically investigated concurrent use of synthetic cathinones with other psychostimulant drugs. The present study utilized conditioned place preference (CPP), a rodent model of conditioned drug reward, to evaluate the effects of concurrent treatment with MDPV and METH. Male (N=72) and female (N=105) Sprague-Dawley rats underwent a two-compartment biased CPP procedure, with one trial per day for eight consecutive days. Subjects were randomly assigned to the following treatment groups: saline, METH (1 mg/kg), MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg) or a mixture consisting of METH (1 mg/kg) and MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg). All treatments increased locomotor activity during drug conditioning trials, and most treatments produced higher activity increases in females compared to males. Although the level of CPP established by MDPV and MDPV+METH mixtures varied between males and females, sex differences were not statistically significant. Although none of the MDPV+METH mixtures produced stronger CPP than either substance alone, some mixtures of MDPV and METH produced higher increases in locomotor activity compared to either drug alone. Further studies with higher doses may be warranted to determine if concurrent use of MDPV and METH pose an enhanced risk for abuse.

Synthetic cathinones are derived from Catha edulis (Khat), an indigenous plant in East Africa used traditionally through oral and buccal routes for its mild stimulant effects (Al-Motarreb et al., 2002; Balint et al., 2009). Numerous synthetic cathinone (SC) analogs have surfaced on the illicit drug market within the last decade, colloquially referred to as “bath salts” (U.S. Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center, 2011). Scientific research and user reports indicate these substances pose a high risk for abuse. Moreover, emergency department and poison control reports (United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, 2015; U.S. Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center, 2011) indicate SCs can produce severe adverse cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric effects.

Despite recent attempts to curtail their use through legal restrictions and public education, novel SCs remain prevalent on the illicit drug market. 3, 4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a popular SC in the United States. Analytical results from a forensic investigation of seized drug products found that MDPV was detected in over 80% of tablet and capsule formulations and was the second most prevalent compound detected in powders (Seely et al., 2013). Additionally, chemical tests of residues from seized drug paraphernalia, including smoking devices, drug packaging and liquids in syringes or vials revealed evidence for concomitant use of MDPV or other SCs along with other drugs of abuse, including methamphetamine (METH), cocaine or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Seely et al., 2013). In consideration of their similar mechanisms of action, concurrent use of SCs with other psychostimulant drugs may pose an enhanced risk for toxicities and abuse.

MDPV is a potent dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, with weaker effects on serotonin reuptake (Eshleman et al., 2013; Simmler et al., 2013). Compared to cocaine, MDPV is up to 50-fold more potent at the dopamine transporter (DAT), approximately 10-fold more potent at the norepinephrine transporter (NET), and 10-fold less potent at the serotonin transporter (Baumann et al., 2012). This enhanced potency may be responsible for the severity of physiological and behavioral toxicities associated with MDPV (Froberg et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2011).

The popularity of polysubstance use with SCs and other psychostimulants is likely due to their similar psychoactive effects. For example, a collection of online personal reports from recreational users indicate the psychoactive effects of MDPV are comparable to other psychostimulant drugs that produce increased levels of empathy, euphoria, mood, self-esteem, sociability, motivation, alertness, energy and sexual arousal (Stanciu et al., 2017). These reports are supported by research findings from in vivo preclinical drug screening of the discriminative stimulus effects of MDPV. For example, several investigators have reported evidence for stimulus generalization between MDPV and other psychostimulant drugs, such as methamphetamine, cocaine, MDMA (Berquist and Baker, 2017; Fantegrossi et al., 2013; Gannon et al., 2016; Gatch et al., 2013; Risca and Baker 2019). Additionally, MDPV has been shown to produce rewarding effects in a conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm (King et al., 2015a) at similar doses to methamphetamine (Goeders and Goeders, 2004; Zakharova et al., 2009) in male rodents.

When the current study was initiated, only one published preclinical study had examined MDPV’s effects in females. That study implemented a combined conditioned taste avoidance (CTA)/CPP paradigm and found that MDPV (1.0, 1.8 or 3.2 mg/kg) produced comparable CPP in male and female rats, but females demonstrated a weaker taste avoidance response compared to males (King et al., 2015b). These findings conflict with previous reports of sex differences in CPP with other psychostimulant drugs. Cocaine, for example, was found to establish CPP at lower doses in females than males (Russo et al., 2003). Additionally, female rats have also been shown to be more sensitive to the locomotor activating effects of methamphetamine (Schindler et al., 2002).

Despite the popularity of polysubstance use, only a few studies have systematically evaluated the combined behavioral effects of synthetic cathinones with other abused psychostimulants in preclinical models of abuse liability. In one study, repeated treatment with low dose mixtures of MDPV and 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC) enhanced the expression of cross-sensitization to the locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine (Berquist et al., 2016). Enhanced locomotor sensitization was also observed with low dose mixtures 4-MMC and MDMA (Bullock et al., 2019) or cocaine (Kohler et al., 2020). Cross-sensitization of MDPV to METH has also been observed (Watterson et al., 2016). In addition, the discriminative stimulus effects of MDPV were potentiated by pretreatment with other DAT or NET/SERT inhibitors (Risca and Baker, 2019) and methamphetamine discrimination was potentiated by caffeine (Munzar et al., 2002).

Whereas the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm has not been utilized extensively to evaluate concomitant treatment with SCs and other psychostimulants, the primary aim of the present study was to determine if concurrent treatment with MDPV and methamphetamine produces stronger CPP than either substance alone. In consideration of the aforementioned reports regarding sex differences with some psychostimulants, a secondary aim of this study was to determine if the behavioral effects of these drug mixtures are sex-dependent.

Methods

Subjects:

Seventy-four male and 105 female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used, with separate experiments conducted using same sex cohorts. All animals were pair-housed in polycarbonate cages with corncob bedding and maintained on a 12:12 hour light dark cycle (lights on at 0700) with ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were approximately 60 days old at the beginning of each experiment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee at Western Michigan University.

Apparatus.

Behavioral assessments were conducted in six identical, two compartment place preference chambers (MED-CPP2-RS, MED Associates INC, Saint Albans, VT) equipped with a manual door between the two compartments and 12 infrared sensors to monitor location and movement of animals. One compartment consisted of white walls and a steel mesh floor, while the other compartment contained black walls and a steel rod floor.

Procedure.

Animals were randomly assigned to one of the following eight treatment groups: saline, 1 mg/kg methamphetamine, one of three MDPV doses (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg), or a mixture containing 1 mg/kg methamphetamine and one of the aforementioned MDPV doses. All animals received intraperitoneal injections during CPP conditioning (day 2 through day 9). Pre-conditioning and post-conditioning assessments were conducted the first and last day of the experiment, day 1 and day 10 respectively. The door between compartments remained open during the pre-test and post-test to allow animals exploration of both compartments for 15 minutes. Preference scores were determined from time spent in each compartment during the pre-conditioning assessment to implement a biased CPP design. Specifically, during conditioning trials, drug injections were paired with exposure to the compartment in which each animal spent the least amount of time during the pre-conditioning test (least preferred) and saline injections were paired with exposure to the other compartment.

Biased CPP conditioning trials lasted a total of eight days and were divided into four, two-day cycles. Each cycle consisted of a drug session, followed by a saline session. Immediately prior to drug conditioning sessions, rats were injected with the treatment drug(s) and confined to the non-preferred compartment for 30 minutes. On saline conditioning days, rats were given a saline injection and confined to the opposite compartment. Dependent variables were activity counts during conditioning trials and CPP difference scores, determined by subtracting the time spent in the drug-paired compartment pre-conditioning (day 1) from the time spent in the same compartment post-conditioning (day 10).

Data analysis.

Activity counts obtained during 30-minute drug conditioning trials were analyzed separately for each sex with a two factor ANOVA to assess the main effects of treatment and test day, followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons of each treatment group with the respective saline control group. Additionally, activity counts were averaged across all four drug trials for each drug treatment and each sex and these averages were analyzed with a two factor ANOVA (treatment, sex) followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. CPP difference scores were calculated for each treatment group and sex and analyzed with a two factor ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons.

Results

Locomotor Activity:

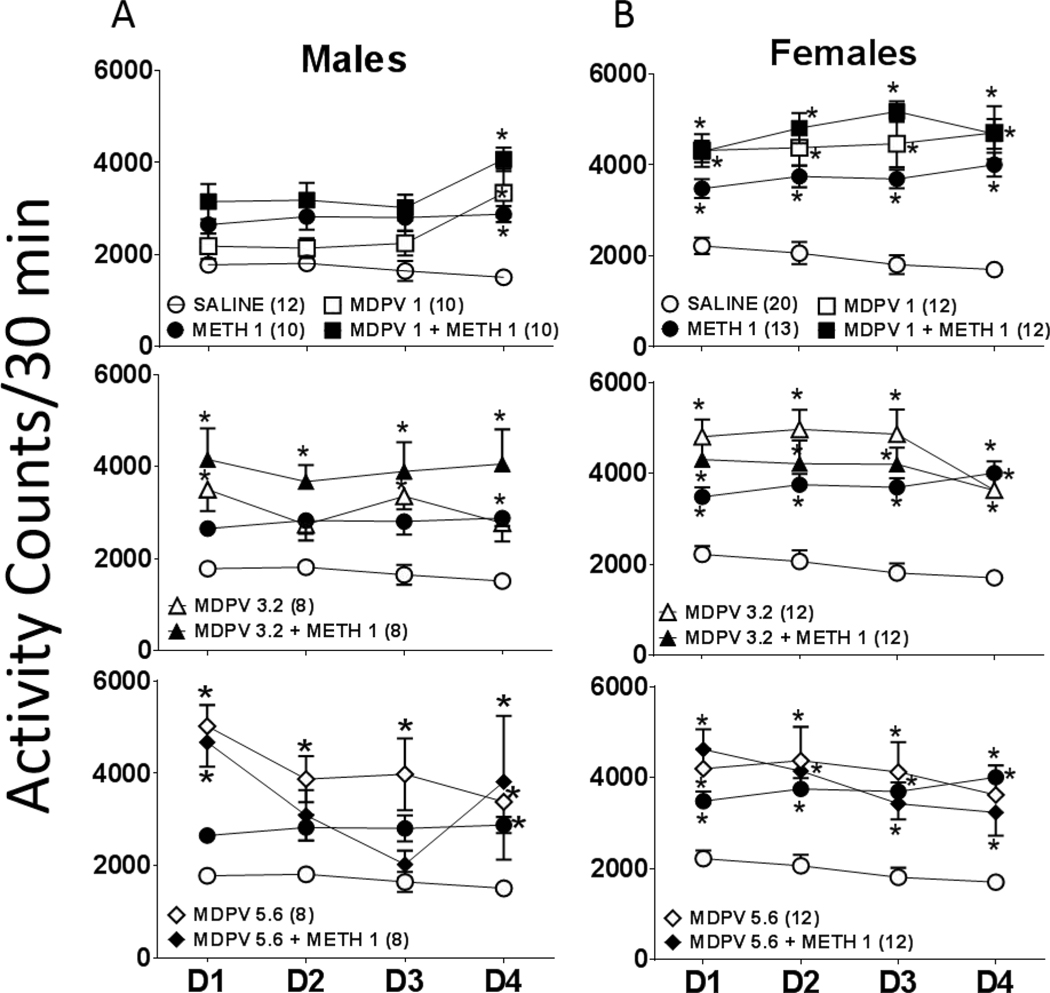

Activity counts obtained during drug conditioning trials indicate that 1 mg/kg METH and all MDPV doses (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg) increased locomotor activity and these increases were comparable with all METH+MDPV mixtures. Figure 1 displays activity counts obtained during each of the four 30 min drug conditioning trials separately for males (A) and females (B). A two way mixed effects ANOVA on activity counts during drug conditioning trials conducted with males revealed a statistically significant treatment effect (F7,66= 5.82, P < 0.01) test day effect (F3,198= 3.44, P < 0.05) and treatment x test day interaction (F21, 198= 1.94, P < 0.05). A similar analysis indicated a statistically significant treatment effect (F7, 97= 12.82, P < 0.01) test day effect (F3, 291= 3.55, P < 0.05) but no treatment x test day interaction (F21, 291= 1.56, P =0.06) on activity counts in females. Activity during saline conditioning trials did not vary among treatment groups or across test days (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Activity counts during 30 min drug conditioning trials in male (A) and female (B) Sprague-Dawley rats treated with saline, 1 mg/kg methamphetamine, MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg) or a mixture of 1 mg/kg methamphetamine and MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg). Saline and METH treatment groups are plotted in all graphs for visual comparison to other treatment groups. Points represent treatment group means (± S.E.M.). Numbers in parentheses next to treatment group labels indicate N. * indicates statistically significant Holm-Sidak comparisons to each respective Saline treatment group.

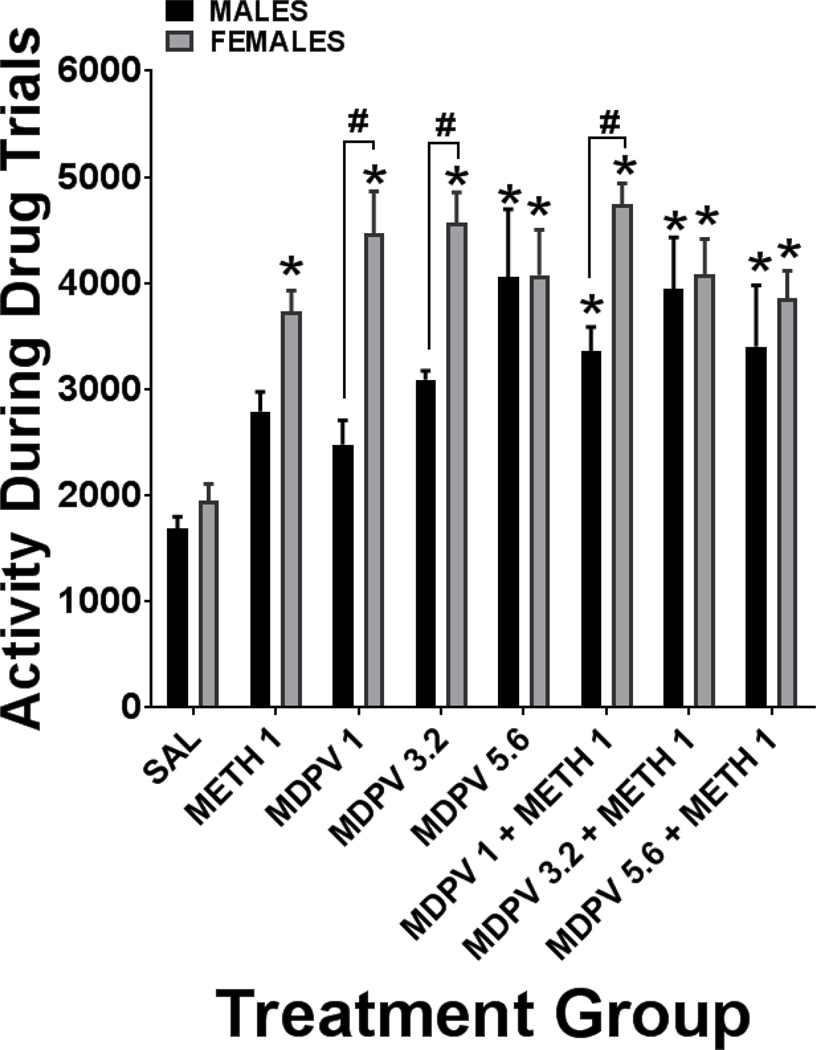

Females exhibited higher increases in activity than males in some treatment groups. To statistically analyze both treatment and sex, activity counts were averaged across all drug conditioning trials for each group. These results are displayed in figure 2. MDPV increased activity in a dose-dependent manner among males, whereas all three MDPV doses produced comparable increases in activity among females. A two-way ANOVA of these results revealed statistically significant main effects of treatment (F7, 163= 14.44, P < 0.01) and sex (F 1, 163= 28.01, p < 0.01) as well as a significant treatment × sex interaction (F7, 163= 2.68, P < 0.05). Planned Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests between treatment groups indicated statistical significance for all drug treatments compared to saline among females. However, only those males treated with 5.6 mg/kg MDPV or any MDPV+METH mixture displayed activity increases that were significantly different from saline-treated males. Additionally, planned post-hoc comparison tests between sexes indicated statistical significance only for the following treatments: 1 mg/kg MDPV, 3.2 mg/kg MDPV, 1 mg/kg METH + 1 mg/kg MDPV.

Figure 2.

Average activity counts across four drug conditioning trials in male (black bars) and female (gray bars) Sprague-Dawley rats treated with saline, 1 mg/kg methamphetamine, MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg) or a mixture of 1 mg/kg methamphetamine and MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg). Bars depict treatment group means (± S.E.M.). * indicates statistically significant Holm-Sidak comparisons to the respective Saline treatment group. # indicates statistically significant Holm-Sidak comparisons between males and females.

Conditioned Place Preference:

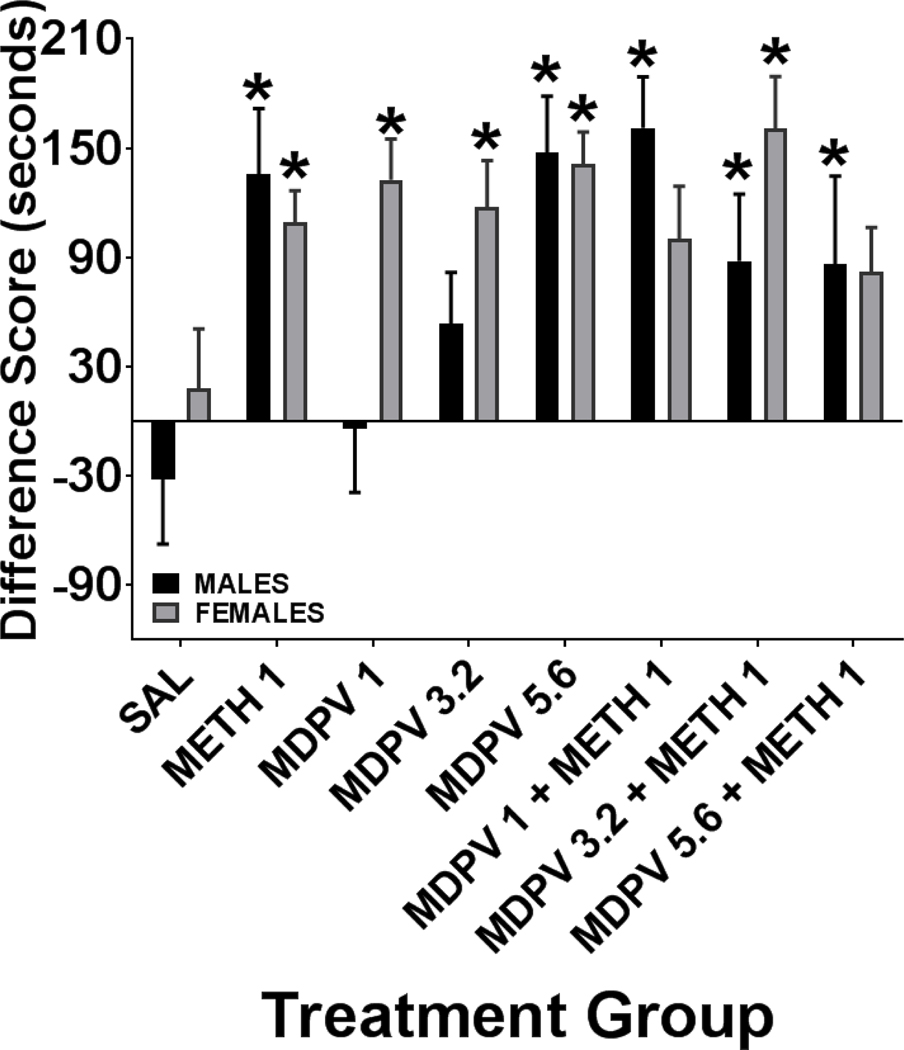

CPP was determined by calculating difference scores from time spent in the drug-paired compartment before and after conditioning trials. Figure 3 displays difference scores obtained for males and females in each treatment group. A two-way ANOVA indicated a statistically significant treatment effect (F7, 161 = 5.87, P < 0.001), whereas sex (F 1, 161 = 3.17, P = 0.08) and a treatment by sex interaction (F7, 161 = 2.03, P = 0.054) were not statistically significant. Similar to MDPV’s effects on activity, difference scores appear to be dose-dependent in males, whereas all three MDPV doses and METH treatment produced comparable difference scores in females. Planned Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests among treatment groups revealed statistical significance between saline and the following treatment groups: METH 1, MDPV 3.2, MDPV 5.6, METH 1 + MDPV 1, and METH 1 + MDPV 3.2. Planned post-hoc comparisons between sexes were not conducted because the main effect of sex was not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Difference scores obtained in male (black bars) and female (gray bars) Sprague-Dawley rats treated with saline, 1 mg/kg methamphetamine, MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg) or a mixture of 1 mg/kg methamphetamine and MDPV (1, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg). Bars depict treatment group means (± S.E.M.). * indicates statistically significant Holm-Sidak comparisons to the respective Saline treatment group.

Discussion

This is the first known study to examine low dose mixtures of MDPV and methamphetamine in a rodent model of conditioned place preference. Previous published findings indicate both substances establish CPP at doses comparable to those examined in the current study (Goeders and Goeders, 2004; King et al., 2015a; 2015b; Thorn et al., 2012; Zakharova et al., 2009). The current results failed to support the hypothesis that MDPV+METH mixtures would produce stronger CPP than either substance alone, at least at the low doses assessed in this study. Further evaluation of potential additive effects of these substances will require the assessment of a wider range of doses.

With respect to sex, the current findings are consistent with those of King et al. (2015b), who reported MDPV-induced CPP did not vary between males and females. However, the aforementioned study implemented CPP procedures in combination conditioned taste avoidance (CTA) and found that MDPV-induced CTA was weaker in females compared to males. Based on these findings, King et al. (2015b) suggested females may have a heightened susceptibility to MDPV abuse.

Although sex differences were not statistically significant for CPP as indexed by difference scores in the current study, a visual analysis of these scores suggests females displayed stronger CPP than males at lower MDPV doses. This observation is consistent with the aforementioned conclusion posed by King et al. (2015b). Furthermore, a statistically significant effect of sex was found for the locomotor stimulant effects of MDPV in the current study. Specifically, females in all drug treatment groups displayed significantly higher activity levels compared to saline-treated controls, while locomotor activity among males was only significantly different from saline-treated controls following 5.6 mg/kg MDPV or any MDPV+METH mixture. Furthermore, significant post-hoc comparisons were observed between males and females treated with 1 mg/kg MDPV, 3.2 mg/kg MDPV, or 1 mg/kg MDPV + 1 mg/kg METH. The absence of differences in locomotor activity between males and females at the highest dose of MDPV and the two highest MDPV+METH mixtures may be due to potential ceiling effects, which may have impacted the overall effect of sex on locomotor activity.

Although visual inspection of activity counts during drug conditioning trials shows a slight increase in activity among males administered 1 mg/kg MDPV or 1 mg/kg MDPV + 1 mg/kg METH during the last drug conditioning trial in comparison to previous trials, these differences were not statistically significant. In contrast, a decrease in activity was observed among males and females over the course of conditioning trials with 5.6 mg/kg MDPV + 1 mg/kg METH as well as for females treated with 3.2 mg/kg MDPV and males treated with 5.6 mg/kg MDPV. Some of these differences were statistically significant in comparison to the first drug conditioning trial and could be interpreted as evidence for tolerance. However, a statistically significant decrease in activity among males treated with 5.6 mg/kg MDPV + 1 mg/kg METH was only observed on drug trials 2 and 3 compared to drug trial 1. Activity in this treatment group was not significantly different between drug trial 1 and drug trial 4. For females treated with this mixture, activity counts during the third and fourth drug conditioning trials were significantly different from activity on the first drug conditioning trial. These differences should be interpreted with caution because activity was assessed within the confined space of the CPP apparatus, which precluded measures of vertical activity or stereotypy. These measures could be explored in future studies. Indeed, the assessment of behavioral tolerance or sensitization are better assessed through alternative paradigms such as psychomotor activity tests in open field or sensitization chambers (Marusich et al., 2013).

It should be noted that the present study used a biased CPP design which in itself may mask the effects of some drugs. Biased designs require preconditioning days in order to calculate the unconditioned preference for a compartment which can influence the strength of CPP (Bardo and Bevins 2000; Tzschentke et al., 1998). A meta-analysis of CPP found that CPP studies without preconditioning/exposure typically demonstrated larger conditioning effects than those in which animals were pre-exposed to test chambers (Bardo et al., 1995).

Additionally, females from the present study displayed more of an asymptotic effect in CPP whereas males exhibited an apparent dose-dependent increase in CPP, up until the two high dose mixtures. Lower doses and alternative paradigms may be warranted to better assess the dose effects of these drug mixtures. It should be noted that a meta-analysis investigating cocaine-induced CPP did not find evidence for a dose-effect relationship either (Bardo et al., 1995). Interpretation of dose-related effects, as well as the general interpretation of results from drug combination studies using CPP has limitations. For example, a lack or reduction of effect from a drug combination when both drugs separately produce an effect could be due to disruption in perception of the conditioning environment, impacting the process of conditioning (Huffman 1989).

Despite limitations of the CPP paradigm, the apparent sex difference in MDPV-induced locomotor stimulant effects combined with lack of convincing evidence for sex differences in MDPV-induced CPP may reflect the notion that these two measures rely on different underlying mechanisms modulating specific behaviors, as noted by previous reports with amphetamine (Stöhr et al., 1998) and methamphetamine (Schindler et al., 2002) demonstrating increased sensitivity in female rodents to locomotor stimulant effects and little to no difference between sexes in conditioned place preference. Collectively, these findings support the notion that psychostimulant drugs modulate different behaviors and emphasize the importance of assessing behavior on multiple dimensions.

In conclusion, the sex differences observed in drug-induced increases in activity indicate females may be more susceptible to the locomotor stimulant effects of MDPV and METH, with lower doses required to produce peak effects in females. Although there was not a statistically significant sex effect on CPP scores, it is noteworthy that females displayed greater shifts in preference to the drug-paired compartment compared to males. Together this evidence might suggest that females may be more sensitive to the stimulant effects and abuse risks of MDPV. Further studies with higher doses may be warranted to determine if concurrent use of MDPV and METH pose an enhanced risk for abuse.

Highlights.

Although polysubstance use is common among illicit drug users, few preclinical studies of drug-induced reward have examined drug mixtures.

This study implemented conditioned place preference procedures with male and female Sprague-Dawley rats to assess concomitant treatment with 3, 4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and methamphetamine (METH).

At the doses assessed, MDPV+METH mixtures did not produce stronger CPP than either substance alone.

Sex differences were observed in drug-induced increases in locomotor activity but not in CPP.

These findings indicate females may be more sensitive than males to the stimulant effects and abuse risks of MDPV.

Acknowledgement:

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R15 DA038295). The National Institute on Drug Abuse drug control supply program provided the drugs used in this study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Al Motarreb, A., Baker K, & Broadley KJ (2002). Khat: pharmacological and medical aspects and its social use in Yemen. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives, 16(5), 403–413. 10.1002/ptr.1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balint EE, Falkay G, & Balint GA (2009). Khat–a controversial plant. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 121(19–20), 604. 10.1007/s00508-009-1259-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardo MT, & Bevins RA (2000). Conditioned place preference: what does it add toour preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology, 153(1), 31–43. 10.1007/s002130000569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardo MT, Rowlett JK, & Harris MJ (1995). Conditioned place preference usingopiate and stimulant drugs: a meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 19(1), 39–51. 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00021-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, ... & Brandt SD (2013). Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive ‘bath salts’ products. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(4), 552–562. 10.1038/npp.2012.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berquist MD 2nd, & Baker LE (2017). Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Behavioural pharmacology, 28(5), 394–400. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berquist II MD, Traxler HK, Mahler AM, & Baker LE (2016). Sensitization to the locomotor stimulant effects of “bath salt” constituents, 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC) and 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Drug and alcohol dependence, 164, 128–134. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock TA, Berquist MD, & Baker LE (2019). Locomotor sensitization in male Sprague-Dawley rats following repeated concurrent treatment with 4-methylmethcathinone and 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. Behavioural pharmacology, 30(7), 566–573. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Hatfield MG, Johnson RA, Murphy KV, & Janowsky A. (2013). Substituted methcathinones differ in transporter and receptor interactions. Biochemical pharmacology, 85(12), 1803–1815. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantegrossi WE, Gannon BM, Zimmerman SM, & Rice KC (2013). In vivo effects of abused ‘bath salt’ constituent 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in mice: drug discrimination, thermoregulation, and locomotor activity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(4), 563–573. 10.1038/npp.2012.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Froberg BA, Levine M, Beuhler MC, Judge BS, Moore PW, Engebretsen KM, ... & ACMT Toxicology Investigators Consortium. (2015). Acute methylenedioxypyrovalerone toxicity. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 11(2), 185–194. 10.1007/s13181-014-0446-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gannon BM, Williamson A, Suzuki M, Rice KC, & Fantegrossi WE (2016). Stereoselective effects of abused “bath salt” constituent 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in mice: drug discrimination, locomotor activity, and thermoregulation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 356(3), 615–623. 10.1124/jpet.115.229500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatch MB, Taylor CM, & Forster MJ (2013). Locomotor stimulant and discriminative stimulus effects of “bath salt” cathinones. Behavioural pharmacology, 24, 437. 10.1097/fbp.0b013e328364166d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goeders JE, & Goeders NE (2004). Effects of oxazepam on methamphetamine induced conditioned place preference. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 78(1), 185–188. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huffman DC (1989). The use of place conditioning in studying the neuropharmacology of drug reinforcement. Brain research bulletin, 23(4–5), 373–387. 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90224-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King HE, Wetzell B, Rice KC, Riley AL. (2015a). An assessment of MDPV-induced place preference in adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 146:116–119. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King HE, Wakeford A, Taylor W, Wetzell B, Rice KC, & Riley AL (2015b). Sex differences in 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)-induced taste avoidance and place preferences. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 137, 16–22. 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohler RJ, Cibelli J. & Baker LE (2020). Combined effects of mephedrone and cocaine on locomotor activity and conditioned place preference in male Sprague–Dawley rats. Behavioural Pharmacology, doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marusich JA, Lefever TW, Novak SP, Blough BE, & Wiley JL (2013). Prediction and prevention of prescription drug abuse: role of preclinical assessment of substance abuse liability. Methods report (RTI Press), 1. doi: 10.3768/rtipress.2013.op.0014.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munzar P, Justinova Z, Kutkat SW, Ferré S, & Goldberg SR (2002). Adenosinergic modulation of the discriminative-stimulus effects of methamphetamine in rats. Psychopharmacology, 161(4), 348–355. 10.1007/s00213-002-1075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54050/ doi: 10.17226/12910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risca HI, & Baker LE (2019). Contribution of monoaminergic mechanisms to the discriminative stimulus effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology, 236(3), 963–971. 10.1007/s00213-018-5145-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo SJ, Jenab S, Fabian SJ, Festa ED, Kemen LM, & Quinones-Jenab V(2003). Sex differences in the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. Brain research, 970(1–2), 214–220. 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02346-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schindler CW, Bross JG, & Thorndike EB (2002). Gender differences in the behavioral effects of methamphetamine. European journal of pharmacology, 442(3), 231–235. 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01550-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seely KA, Patton AL, Moran CL, Womack ML, Prather PL, Fantegrossi WE, ... & McCain KR (2013). Forensic investigation of K2, Spice, and “bath salt” commercial preparations: a three-year study of new designer drug products containing synthetic cannabinoid, stimulant, and hallucinogenic compounds. Forensic science international, 233(1–3), 416–422. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, ... & Liechti ME (2013). Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. British journal of pharmacology, 168(2), 458–470. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, & Jansen J. (2011). Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs”(synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clinical toxicology, 49(6), 499–505. 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanciu CN, Penders TM, Gnanasegaram SA, Pirapakaran E, Padda JS, & Padda JS (2017). The behavioral profile of methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (PVP)-A Systematic Review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev, 10(999), 1–1. 10.2174/1874473710666170321122226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stöhr T, Wermeling DS, Weiner I, & Feldon J. (1998). Rat strain differences in open-field behavior and the locomotor stimulating and rewarding effects of amphetamine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 59(4), 813–818. 10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00542-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorn DA, Winter JC, & Li JX (2012). Agmatine attenuates methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. European journal of pharmacology, 680(1–3), 69–72. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tzschentke TM (1998). Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: a comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Progress in neurobiology, 56(6), 613–672. 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00060-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center (2011) Situation report: synthetic cathinones (bath salts): an emerging domestic threat. National Drug Intelligence Center, Johnstown, pp 15901–11622 http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44571/44571p.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNODC (2015) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: World Drug Report 2015. United Nations publication, New York: http://www.undoc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Taylor SB, Nemirovsky NE, & Olive MF (2016). Sensitization to the motor stimulant effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and cross-sensitization to methamphetamine in rats. Journal of drug and alcohol research, 5, 235967. 10.4303/jdar/235967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakharova E, Leoni G, Kichko I, & Izenwasser S. (2009). Differential effects of methamphetamine and cocaine on conditioned place preference and locomotor activity in adult and adolescent male rats. Behavioural brain research, 198(1), 45–50. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]