Abstract

Naegleria fowleri is the protozoan pathogen that causes primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), with the death rate exceeding 97%. The amoeba makes sterols and can be targeted by sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Here, we characterized N. fowleri sterol 14-demethylase, including catalytic properties and inhibition by clinical antifungal drugs and experimental substituted azoles with favorable pharmacokinetics and low toxicity. None of them inhibited the enzyme stoichiometrically. The highest potencies were displayed by posaconazole (IC50 = 0.69 μM) and two of our compounds (IC50 =1.3 and 0.35 μM). Because both these compounds penetrate the brain with concentrations reaching minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values in an N. fowleri cellular assay, we report them as potential drug candidates for PAM. The 2.1 Å crystal structure, in complex with the strongest inhibitor, provides an explanation connecting the enzyme weaker substrate specificity with lower sensitivity to inhibition. It also provides insight into the enzyme/ligand molecular recognition process and suggests directions for the design of more potent inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Naegleria fowleri, or the brain–eating amoeba, is a free-living unicellular eukaryotic organism found in warm freshwater places (e.g., ponds, lakes, rivers, hot springs) and soil. It causes a rare but nearly always fatal disease called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/). The infection occurs through the nose, and then the pathogen migrates to the brain, where it destroys brain tissue. Death follows within 1–15 days after the exposure. Due to the expansion of N. fowleri habitat, the disease is often considered as emerging,1–4 with the 381 cases reported globally within 1978–2018 likely representing a small fraction of the total number of PAM cases.5 Among the infected, there have been only seven survivors with a confirmed diagnosis. The treatment of six of them included antifungal azoles (ketoconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole).5 These clinical systemic drugs are inhibitors of sterol 14α-demethylase, the cytochrome P450 51 enzyme (CYP51) required for biosynthesis of sterols.6

Sterols are indispensable lipid components of eukaryotic cells, essential for the membrane biogenesis, integrity, and function as well as for intra- and intercellular signaling. They are either produced endogenously (most eukaryotes) or have to be acquired from food (e.g., insects, worms). N. fowleri is known to synthesize endogenous sterols, the pathway going through the cyclization of squalene-2,3-epoxide into cycloartenol,7 as in plants/algae.6 The physiological end-product sterols in N. folweri, however, are ergosterol-like, similar to those in Euglenozoa (Kinetoplastida).8

The objective of this work was to characterize N. fowleri CYP51 biochemically and to study its inhibition, by clinical antifungal azoles and by our experimental compounds (VNI derivatives) that were structure-based designed as stoichiometric inhibitors of Trypanosomatidae9 and fungal10 CYP51, and have favorable toxicity and pharmacokinetics profiles.9

We found that regardless of its plant-specific signature residue in the BC loop (Phe109), N. fowleri CYP51 displays relaxed substrate requirements, which coincide with lower susceptibility to inhibition (than seen for any microbial CYP51 orthologs studied by our team6). The 2.1 Å crystal structure of N. fowleri CYP51, in complex with the most potent experimental inhibitor F-VFV ((R)-N-(2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-(3,4’,5-trifluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide), provides a molecular basis for the enzyme resistance to inhibition/weakened substrate selectivity and outlines possible directions for the design of stronger inhibitory ligands. Moreover, it provides new insight into the substrate/inhibitor binding process in the active site of CYP51s across phylogeny.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequence Analysis.

Multiple sequence alignment (Figure 1) shows that all of the residues known to be required for sterol 14α-demethylases11 are present in the N. fowleri protein, leaving no doubt about the enzyme classification/functionality. Thus, in the BC loop, Tyr107, Phe114, and Gly115 are completely conserved across the family. A phyla-specific phenylalanine (Phe109) vs the animal/fungal leucine in this position suggests plantlike substrate preferences (toward the C4 monomethylated vs C4 dimethylated sterol substrates),12 while Tyr120 (vs Phe in plants) implies heme support similar to animal, fungi, and Euglenozoa CYP51s.13 In the C-helix, Glu131 aligns with the conserved glutamine that interacts with the sterol substrate side chain.14 Helix I contains the CYP51 family signature His residue, crucial for proton delivery,14,15 and is followed by “the conserved P450 threonine” (sometimes a serine in CYP51). In the K/β1-4 loop, the Pro375 residue indicates that, as the vast majority of CYP51 enzymes, the N. fowleri ortholog belongs to the B-type, which is typical for the organisms that contain a single CYP51 gene.16,17 Arg363 is also conserved in all CYP51s, its role being to form a salt bridge with the heme ring A propionate. There is no strict conservation in the areas aligned with the F” helix and the β4 hairpin, which are mostly phylum-specific.11

Figure 1.

Sterol 14α-demethylases from different phyla. (A) Phylogenetic tree (rendered in TreeDyn 198.3). Colored leaves (top to bottom): clade Discoba phylum Heterolobosea (red); clade Discoba phylum Euglenozoa (goldenrod); clade Amoebozoa phyla Evosea (orange) and Discosea (magenta); algae (lime); plants (green); animals (blue), fungi (plum). Branch support values are displayed in %. (B) Aligned CYP51 active site areas. N. fowleri numbering is presented on the top. Residues known to be crucial for the CYP51 function and absolutely conserved across all biological domains are in red. The N. fowleri residues with the proposed specific roles (Arg108 and Met129, described later in the discussion) are marked with blue arrows. Complete sequence alignment can be found in Figure S1.

Overall the sequence analysis shows that, although the phylogenetic tree implies that the enzymes from Nagleria sp. (clade Discoba phylum Heterolobosea) might have coevolved with Trypanosomatidae (clade Discoba phylum Euglenozoa, 30–31% sequence identity), they have higher identities to CYP51 enzymes from the separate, neighboring and broader cluster, which in addition to other free-living amoebas (clade Amoebozoa, phyla Discosea (Acantamoebas) and Evosea (Dictyostelium)) includes algae and green plants: (39–35% identity). This pattern might reflect some evolutionary convergence process (e.g., as a result of the ability of Naegleria sp. to exist as free-living organisms), but higher sequence similarity to photosynthetic organisms is in line with the squalene-2,3-epoxide to cycloartenol (plant- or rather algae-like) path for steroidogenesis in Nagleria. The average identities with animal and fungal CYP51 enzymes drop to 33 and 28%, respectively. Details can be found in the Experimental Section.

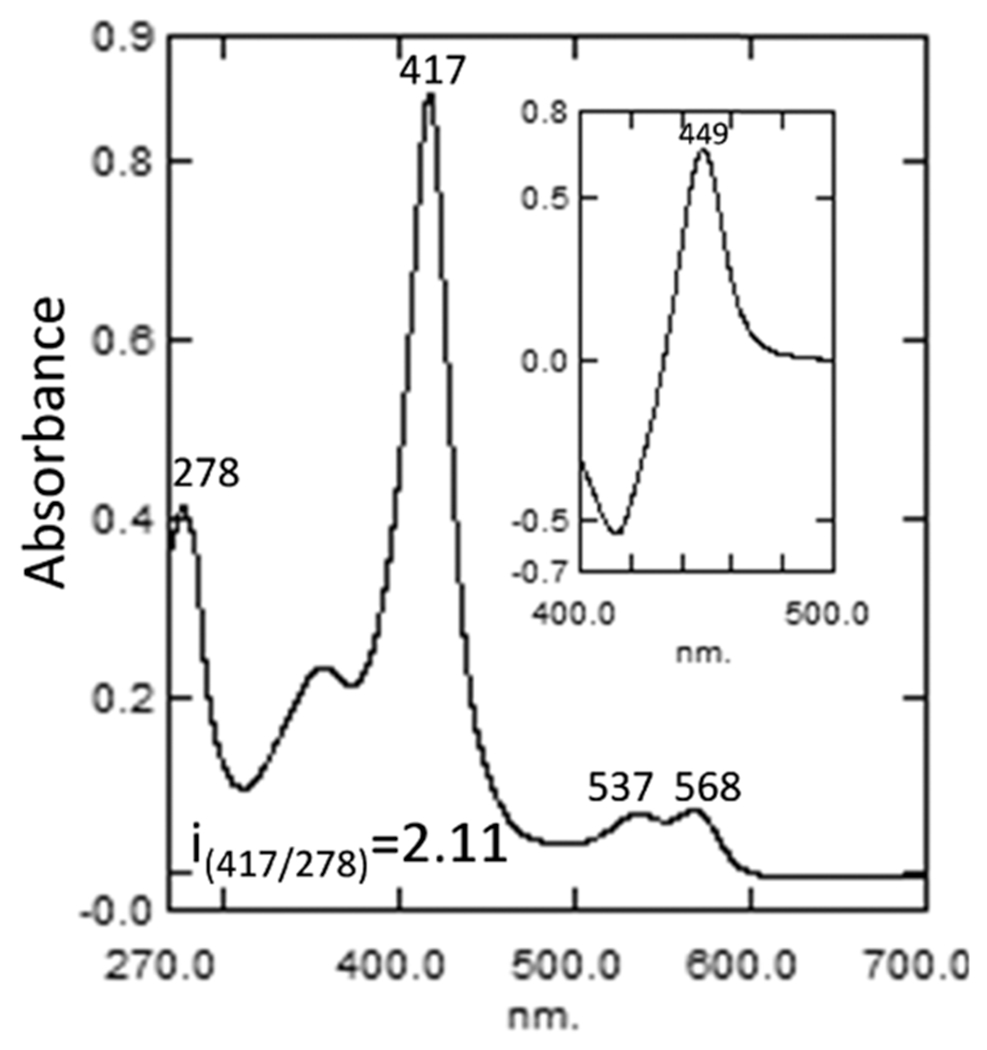

Optical Properties.

The UV–visible absolute absorbance spectrum of the purified N. fowleri CYP51 (Figure 2) was typical of a ferric, low-spin water-bound P450 with the maxima of the α-, β-, and Soret bands at 568, 537, and 417 nm, respectively, and the ratio ΔA393–470/ΔA419–470 = 0.35. The spectrophotometric index (A417/A278) was 2.11, which is the highest observed for CYP51 enzymes and is attributed to the relatively low content of aromatic residues (e.g., one tryptophan vs five in Leishmannia infantum, six in human, or eight in Candida albicans CYP51). The heme iron was readily reduced by sodium dithionite, and the difference spectrum of the ferrous CO-complex18 had an absorbance maximum at 449 nm with no quantifiable denatured cytochrome P420 form (Figure 2, inset).

Figure 2.

Absolute absorbance spectrum of purified N. fowleri CYP51. Inset: reduced carbon monoxide difference spectrum. The P450 concentration ~7 μM.

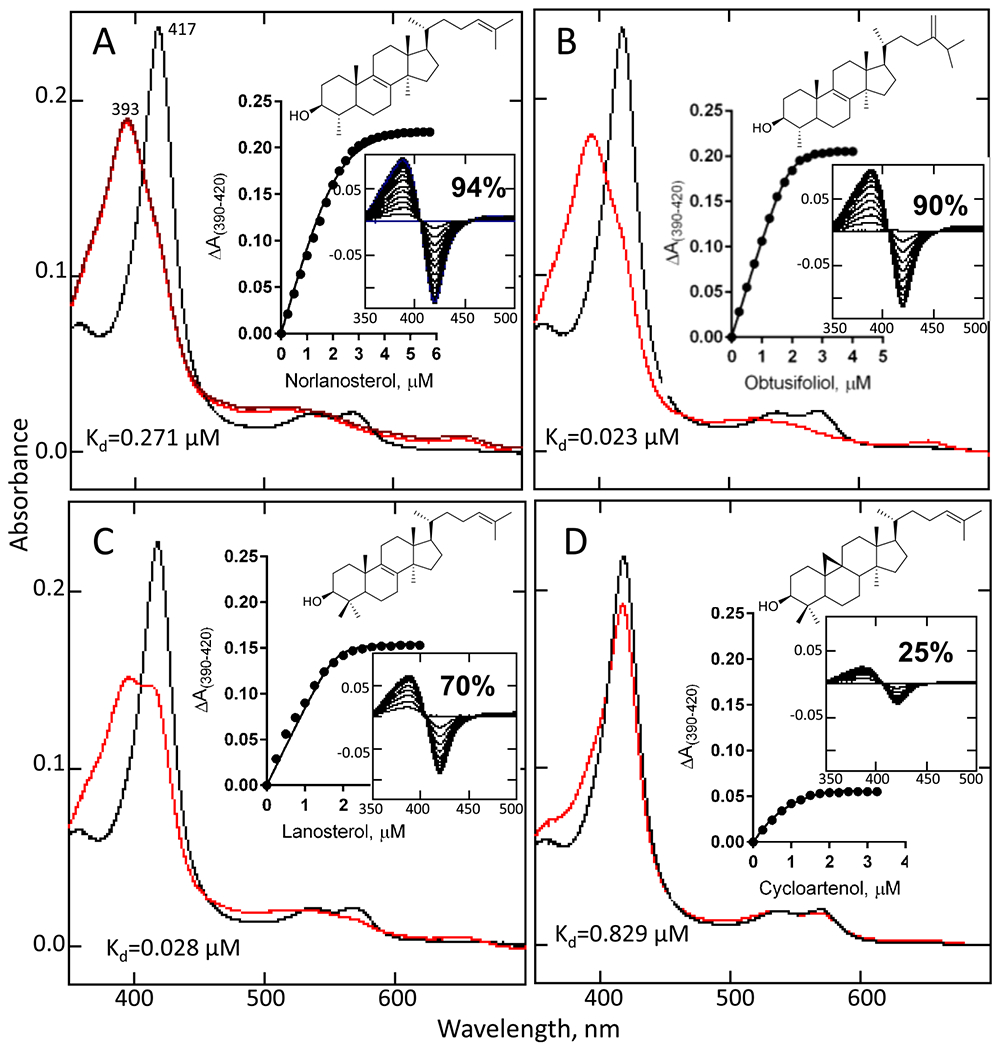

Spectrally Estimated Binding Affinities for Sterol Substrates.

The presence of a phenylalanine in position 109 in the amoebial sterol 14α-demethylase (corresponding to Phe105 in Trypanosoma brucei CYP5119) suggested that the enzyme must be plantlike, i.e., specific toward C4-monomethylated sterols. However, the substrate requirements of N. fowleri CYP51 were not found to be so strict. All four sterols tested here produced typical Type I spectral response (due to displacement of the water molecule from the heme iron coordination sphere, leading to the iron spin state transition from the hexa-coordinate low to the penta-coordinate high). The amplitude of the response (the fraction of substrate-bound molecules) was indeed higher for the C4-monomethylated norlanosterol and obtusifoliol (94 and 90% low-to high-spin state transition in the heme iron, respectively (Figure 3A,B)); however, the enzyme also responded spectrally to the addition of C4-dimethylated lanosterol (Figure 3C, 70% transition) and even to cycloartenol, the initial sterol formed upon cyclization of squalene-2,3-epoxide in plants and algae (25% transition, Figure 3D). Moreover, regardless of the lower amplitude of the response, the apparent dissociation constants (Kd) derived from the titration plots implied similar affinity for the binding of lanosterol (28 nM) and obtusifoliol (23 nM), the corresponding values for norlanosterol and cycloartenol being much higher (271 and 829 nM, respectively).

Figure 3.

Spectral responses of N. fowleri CYP51 to the titration with the sterols: norlanosterol (A), obtusifoliol (B), lanosterol (C), and cycloartenol (D). Absolute absorption spectra (black) before and (red) after the titrations. Inset: the titration curves with hyperbolic fitting to the quadratic Morrison equation (A–C) or Michaelis–Menten equation (D) and the corresponding type I difference absorption spectra. The optical path length was 1 cm, and the P450 concentration was ~2 μM. Statistical parameters can be found in Figure S2.

Catalytic Activity and Steady-State Kinetic Parameters.

The sterol 14α-demethylase activity of the enzyme was reconstituted with C4-monomethylated obtusifoliol and with C4-dimethylated lanosterol (Figure 4) because these two sterols revealed the highest spectral binding affinities. We found that regardless of sequence predictions and the higher fraction of low-to high-spin state transition upon obtusifoliol binding, N. fowleri CYP51 catalyzed the reaction with lanosterol quite well (kcat 64 min−1, vs 26 min−1 for obtusifoliol, Table 1), though the specificity constant (or kinetic efficiency, kcat/Km) for obtusifoliol was still slightly higher (3.2 vs 1.3). Thus, N. fowleri CYP51 can bind and catalyze 14α-demethylation of both C4 mono- and C4 dimethyl sterols.

Figure 4.

Catalytic activity of N. fowleri CYP51, Michaelis–Menten curves. The experiments were performed in triplicate; the results are presented as mean ± SD. P450 concentration is 0.5 μM.

Table 1.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters

| substrate | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| obtusifoliol | 26 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 3.2 |

| lanosterol | 64 ± 8 | 48 ± 10 | 1.3 |

Spectrally Estimated Binding Affinities for Inhibitory Ligands.

The addition of azoles induced red shifts in the Soret band maximum, from 417 to 424 nm (a typical Type II spectral response in the difference spectra, with the trough at 413 and the maximum at 433 nm), indicative of the replacement of the oxygen atom of water (weak coordination bond with the heme iron) with the more basic N3 nitrogen of an imidazole ring (stronger coordination bond with the iron)20 (Figure 5). The observed apparent spectral binding affinities were all very high, in the low nanomolar range, for both ketoconazole, which was used as a control (Kd = 5 nM, Figure 5A), and our six VNI scaffold derivatives VNI (5 nM), FF-VNI (3 nM), FCF3-VNI (11 nM) (Figure 5B), VFV (10 nM), F-VFV (7 nM), and VFV-Cl (25 nM) (Figure 5C). In all cases, saturation was reached at the equimolar ratio enzyme/inhibitory ligand.

Figure 5.

Spectral responses of N. fowleri CYP51 to the titration with azoles. (A) Absolute absorption spectra before (black)and after (red) the titration with ketoconazole, used as a control. Inset: the titration curve with hyperbolic fitting to the quadratic Morrison equation and the corresponding type II different absorption spectra. Panels (B) and (C) show the titration curves and difference spectral responses to the experimental compounds, VNI, VFV, and their analogues, respectively. The titration step is 0.1 μM and the optical path length is 5 cm.

Inhibition of N. fowleri CYP51 Activity.

In addition to the fact that Kd values so low are difficult to quantitate precisely, these values—as we reported previously for other CYP51 orthologs20–22—may often be misleading and not necessarily correlate with strong inhibitory potencies.

Indeed, none of the “tight-binding” ligands acted as a stoichiometric functionally irreversible inhibitor (complete inhibition of CYP51 catalysis over time at an equimolar ratio to the enzyme, as we observed for Trypanosomatidae,9 fungal,10 and even human CYP5122 enzymes). Thus, posaconazole, which was the strongest inhibitor among the clinical antifungal drugs (IC50 0.69 μM), displayed complete inhibition of N. fowleri CYP51 activity at 2.0 μM (i.e., 4-fold molar excess over the enzyme). Potencies of the other clinical drugs were as follows: isavuconazole (IC50 0.96 μM), ketoconazole (1.3 μM), itraconazole (2.1 μM), voriconazole (3.2 μM), and fluconazole (7.1 μM) (Figure 6A). Noteworthy, this is somewhat in agreement with the earlier reported findings that clinical isolates of N. fowleri are more sensitive to ketoconazole but less so to triazoles itraconazole, and fluconazole.23 The potency of VNI, a stoichiometric functionally irreversible inhibitor of CYP51s from Typhochrestus brucei and Trigonoscuta cruzi,24,25 was rather low (IC50 5.6 μM, with complete inhibition achieved only at 50 μM). Its close analogue FF-VNI (the compound where two hydrogen atoms in the distal phenyl ring of the 3-ring linear polycycle arm were replaced with fluorines (meta- and para-positions) (see Figure 5B)), however, was much stronger: although its IC50 was 1.3 μM, complete inhibition was achieved at 6 μM (Figure 6B). Oddly enough, the compound where para-fluorine atom was replaced with a –CF3 group (FCF3-VNI in Figure 5B) had the IC50 value of 0.9 μM but did not inhibit N. fowleri CYP51 activity completely even at 50 μM. Equipped with a biphenyl-(instead of a phenyl-) arm, VFV produced better a better IC50 value (0.68 μM), with complete inhibition at 6.0 μM. Replacement of the fluorine atom in the biphenyl arm proximal ring with Cl (VFV-Cl) substantially weakened the potency (IC50 5.9 μM), but an additional metafluorine atom in this ring afforded the strongest inhibitor, F-VFV, IC50 0.35 μM, with complete inhibition at 3.0 μM (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of N. fowleri CYP51 catalytic activity by (A) antifungal drugs (fluconazole (FLU), voriconazole (VOR), itraconazole (ITR), ketoconazole (KET), isavuconazole (ISA), and posaconazole (POS)) and experimental inhibitors: (B) VNI and analogues and (C) VFV and analogues, 1 h reaction. The experiments were performed in triplicate; the results are presented as mean ± SD. P450 concentration is 0.5 μM. Statistics for IC50 calculations is shown in Table S2.

Crystallographic Analysis.

To understand the molecular basis for the observed variations in inhibitory potencies and, more general, for the relative resistance of N. fowleri CYP51 to inhibition, we cocrystallized the enzyme with F-VFV and determined the X-ray structure of the complex at a resolution of 2.1 Å (PDB code 7RTQ) with the Rwork/Rfree = 0.211/0.231 and the average B-factor 28.5 Å2. The detailed information on data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Table S1. Crystals belonged to the P1 space group, and the asymmetric unit contained four polypeptide chains. The RMSD for Cα atoms between the chains was 0.05 Å. The overall structure was reasonably similar to the structures of CYP51 enzymes from other species (Table 2), with the RMSD being within the range of deviations across phylogeny.13

Table 2.

RMSD between the Different CYP51 Structures, Å

| N. fowleri (molecules A, B, C, D) | T. cruzi: 3k10a, 3zg2, 4ck8, 4h6o, | L. infantum: 3l4d | T. brucei: 3gw9, 3tik, 4g3j, 4g7g | A. fumigatus: 4uyl, 4uym, 5frb, 6cr2 | C. albicans: 5fsa, 5tz1 | human: 4uhi, 6q2t | M. capsulatus: 6mcw, 6mi0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.042 ± 0.01 | 1.74 ± 0.05 | 1.76 ± 0.01 | 1.86 ± 0.02 | 1.97 ± 0.03 | 2.03 ± 0.09 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 1.82 ± 0.02 |

PDB ID.

The major difference in the protein backbone is that the B’ and F” helical inserts within the BC and FG loops partially lack their main chain helical H-bonding (being more looplike) and have higher B-factors, which range from 26 to 58 Å2 (residues 106–117) and from 38 to 96 Å2 (residues 207–225), respectively (Figure S3A). Either as a result or a trigger for these rearrangements F-VFV in the N. fowleri CYP51 active site is bound in two different conformations. Conformer A has the “traditional” orientation found in most CYP51/inhibitor costructures (Figure 7A), with the distal phenyl ring of its three-ring arm approaching the protein surface between the helix A’, FG loop, and β4 hairpin (we usually referred to it as the CYP51 “substrate access channel entrance”25 or “P450 tunnel 2f” in Wade’s nomenclature26). The outer portion of the conformer B molecule is trapped between the BC and FG loops (Figure 7B), a position that has never been observed before in a CYP51 structure and has the closest correspondence to “P450 tunnel 2ac” in Wade’s nomenclature.27 Although there are 22 protein residues contacting each conformer, with 16 of them being common and 6 conformer specific (Figure 7C,D), the program MOE28 predicts that the binding affinity of N. fowleri CYP51 for conformer B is stronger (−10.90 vs −10.37 kcal/mol, which corresponds to the Kd values of 10 and 23 nM, respectively (Table 3)). This prediction is in agreement with the fact that while the B-factors of both conformers are gradually increasing toward the protein surface (meaning the strongest binding of the substituted β-biphenyl arm in the deepest portion of the CYP51 active site), the increase in the B-factor of the (outer) three-ring polycyclic arm of conformer B is lower (Figure S3B). Moreover, when other VNI and VFV derivatives are inserted into the structure and analyzed in MOE (assuming that they acquire the same two conformations as F-VFV), in all cases the calculated strength of ligand–apoprotein interactions for conformer B is higher (Table 3, Figure S4 shows protein–ligand contacts in the models). Interestingly, a correlation between the MOE-calculated Kds for the models and experimental IC50 values is often better than between the IC50 and the Kd values determined spectrally, especially for VNI derivatives, which also form smaller numbers of contacts with the protein. The discrepancy is seen for VFV-Cl, although looking closer at the structure, it appears that the program did not count possible clashes between the (bulkier than fluorine) chlorine atom of VFV-Cl and the phenyl residue (Phe292) in the I helix, instead of assuming a backward movement of Phe114 (BC loop) (Figure S5).

Figure 7.

F-VFV binds in the N. fowleri CYP51 active site in two conformations. (A) View from the distal P450 surface (atoms of conformer A are presented as spheres). (B) View from the upper P450 surface (atoms of conformer B are presented as spheres). The BC loop is orange; the FG loop is blue, the A’ helix is green, and the β4 hairpin is purple. Carbone atoms of the heme and inhibitor are salmon and yellow, respectively. Here and in the other figures, oxygen is red, nitrogen is blue, sulfur is yellow, and fluorine is light green or gray. (C, D) Contacts between the protein and conformers A and B, respectively, calculated in MOE using molecule A of 7RTQ. Polar interactions are in plum; hydrophobic interactions are in green. Arene–H interaction between the inhibitor distal phenyl ring of the biphenyl arm and the methyl group of the porphyrin ring D is indicated as a green dotted line. All six conformer A-specific interactions (Phe53, Pro213, Phe217, Met360, Met362, and Val468) are hydrophobic; three of the six conformer B-specific interactions (Met110, Arg111, Val113, Ile211, Ser215, and Arg226) are polar. Calculated contacts between the protein and modeled VNI/VFV analogues are shown in Figure S4.

Table 3.

VNI Derivatives as Inhibitory Ligands of N. fowleri CYP51a

| predicted binding affinity, kcal/molb (Kd, nM) |

number of contact residues |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inhibitor | spectral (Kd, nM) | IC50, μM (1 h reaction) | conformer A | conformer B | conformer A | conformer B |

| VNI | 5 | 5.63 | −8.91 (275) | −9.32 (138) | 17 | 17 |

| FF-VNI | 3 | 1.28 | −9.19 (170) | −9.36 (128) | 19 | 18 |

| FCF3-VNI | 11 | 0.93 | −9.00 (220) | −9.07 (210) | 20 | 21 |

| VFV | 10 | 0.68 | −10.28 (27) | −10.72 (13) | 22 | 22 |

| F-VFV | 7 | 0.35 | −10.37 (23) | −10.90 (10) | 22 | 22 |

| VFV-Cl | 25 | 5.94 | −10.22 (30) | −10.52 (18) | 22 | 22 |

Experimental results and MOE predictions.

Gibbs free energy was calculated only for interactions with the apoprotein moiety.

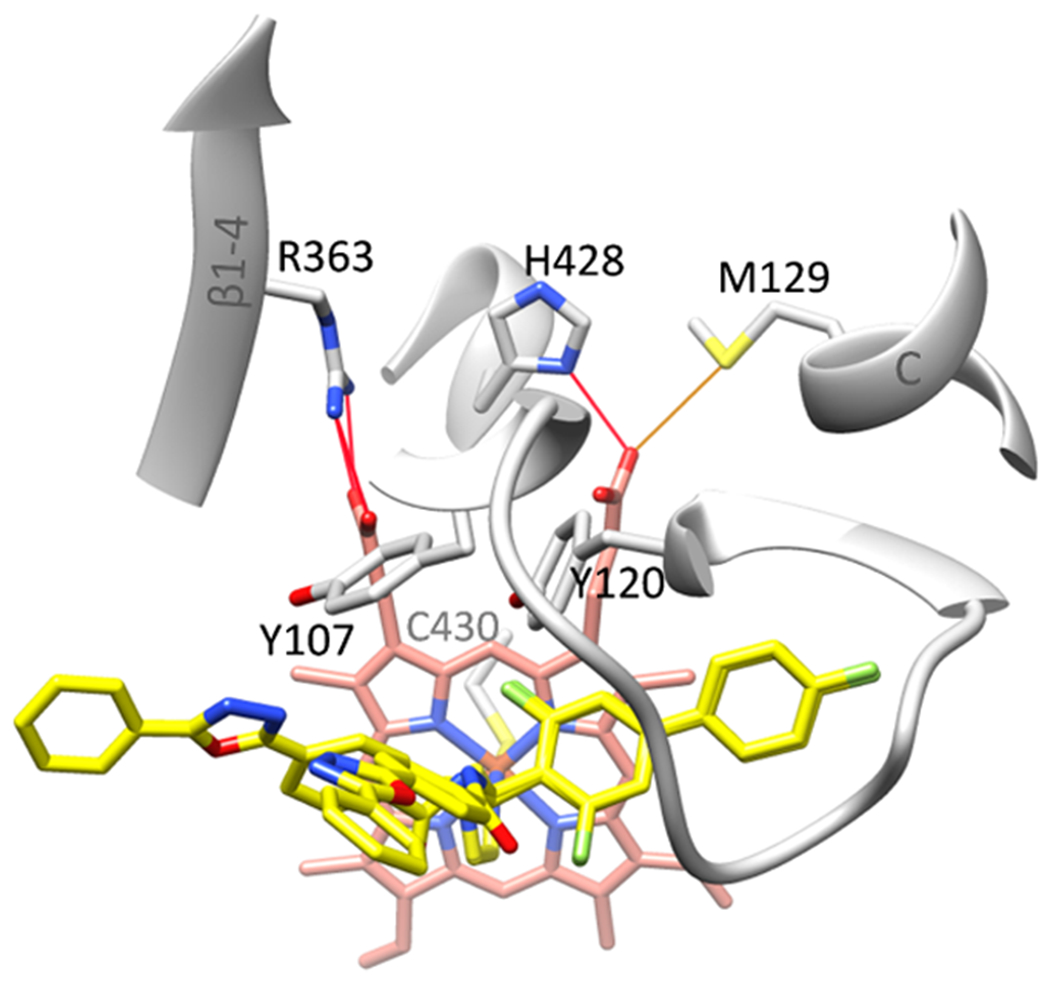

The heme support in the N. fowleri CYP51 structure, in addition to the conserved P450 cysteine (Cys430), whose sulfur atom serves as the proximal ligand to the iron (the Fe–S bond length is 2.3 Å), includes salt bridges typical for all CYP51 enzymes, i.e., with Arg363 (β1–4) and His428 (heme bulge). The H-bonds with Tyr107 and Tyr120, however, are both lost due to the inhibitor accommodation (Figure 8), a feature previously seen upon binding of some other inhibitors to protozoan25,29–31 and fungal CYP51,16,32 although usually disruption of only one of these H-bonds is observed. Interestingly, evaluation of the heme–protein interactions in MOE indicates that there must be an additional bond between the heme ring D propionate (O2D) and the sulfur atom of Met129 (helix C, marked with a blue arrow in Figure 1B), Gibbs free energy −3.5 kcal/mol. For comparison, estimated ΔG values for Arg363 interactions with O1A and O2A are ~−10.0 kcal/mol each, and for His428 interactions with O1D and O2D, they are −2.0 and −9.0 kcal/mol, respectively. This suggests that in N. fowleri CYP51, in addition to its contribution to the protein stability, Met129 might be involved in electron transfer, thus playing the same role as Arg124 in Trypanosomatidae and Lys156/Lys143 (human and C. albicans numbering, respectively) in animals and fungi.14

Figure 8.

Heme support in N. fowleri CYP51. Color code is the same as in Figure 7. Instead of forming H-bonds with the heme propionates, the side-chain hydroxyl of Tyr107 approaches the N3 nitrogen (2.6 Å) of the oxadiazole ring of conformer A, and the side-chain hydroxyl of Tyr120 approaches the fluorine atom of the biphenyl ring of the inhibitor (2.7 Å).

The most surprising feature of this structure is probably the flipping of Phe109 (Figure 9A), which is now positioned above the surface of the protein globule, a rare case for this hydrophobic residue. Although alternative options (including crystal packing) cannot be dismissed, we surmise that this flip could be associated with the preceding Naegleria-specific arginine (Arg108, marked with a blue arrow in Figure 1B). Since this charged residue has a high propensity to be solvent accessible, it might also “mobilize” (drag to the surface) Phe109, making this portion of the BC loop more movable and weakening its interactions with the FG loop. This would provide an explanation not only for the ability of this enzyme to bind an inhibitor in the unusual B-conformation but also for its relaxed substrate preferences and lower sensitivity to inhibition.

Figure 9.

Substrate-preferences defining residue (F109) flips in the F-VFV-bound N. fowleri CYP51. (A) Electron density of the protein in the region around Phe109. The 2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1.5 sigma is shown as gray mesh. The ligand omit map for F-VFV is shown in Figure S6. (B) Superimposition with VFV-bound T. brucei CYP51 (light blue, the B’ helix is semitransparent, PDB ID 4g7g) and with obtusifoliol-bound I105F mutant of T. cruzi CYP51 (light brown, the B’ helix is semitransparent, PDB ID 6FMO). Orientation is similar to (A). Phe109 in N. fowleri CYP51 in trypanosomal structures aligns with Phe105, the residue that makes CYP51 prefer C4-monomethyl sterol substrates. The CYP51 signature phenylalanine (corresponds to Phe114 in N. fowleri) is also marked. As a result of the BC loop rearrangement (the flip of Phe109), the outer rings of the three-ring arm of conformer B acquire the position between the BC and FG loops.

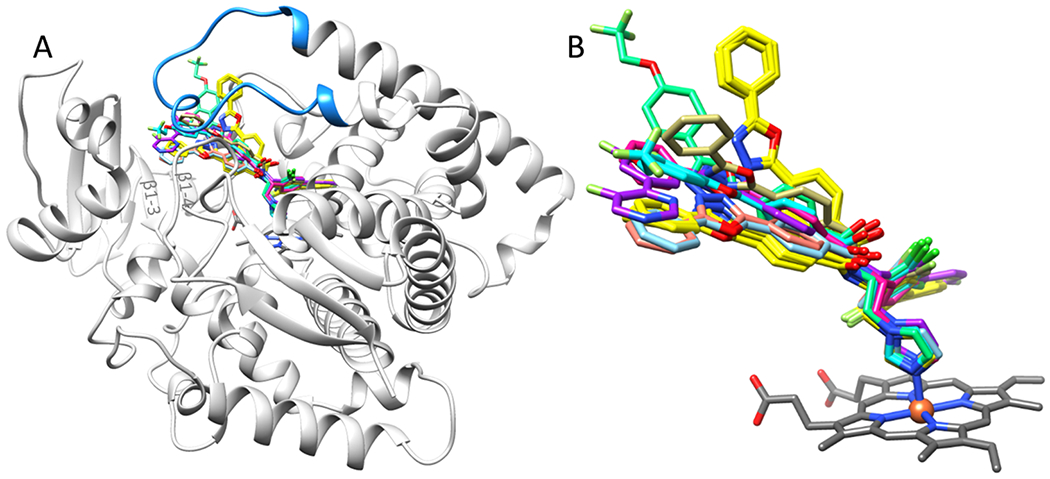

To compare binding poses of two F-VFV conformers in N. fowleri CYP51 with the binding poses of other VNI/VFV analogues cocrystallized with different CYP51 orthologs, we superimposed all four molecules from N. fowleri with CYP51 enzymes from T. brucei, Aspergillus fumigatus, and human. The overall picture altered our views about the CYP51 inhibitor/substrate binding process (Figure 10). The figure shows that the outer portions of the inhibitory molecules are all spread over the β1-sheet floor (antiparallel strands β1-3/β1-4) and “clamped” to this floor by the FG loop. This strongly suggests that substrates/inhibitory ligands must be entering the CYP51 active site not by squeezing through a channel/tunnel(s) [an event which always seemed unlikely because the van der Waals radii of the ligand molecules are almost always larger than those of a channel entry] but as a result of a wide opening of the cleft between the flexible FG loop cover and the steady β1-sheet floor. Then, a small molecule must acquire the position that affords the highest affinity for the apoprotein, the interaction involving partial or (e.g., in the case of the substrates14,15) complete closing of the entry. Overall, while in N. fowleri CYP51, conformers A and B occupy tunnels 2f and 2ac (see above), in A. fumigatus, conformer B points toward tunnel 2b,27 and the arms of the rest of the inhibitors are spread over the space that could be called “extended tunnel 2f.” Thus, the proposed cleft covers the surface that includes tunnels 2f, 2ac, and 2b [Wade’s nomenclature27], with number 2 being originally assigned to their names based on the prediction that these tunnels must be “related by their opening modes.”

Figure 10.

Inhibitors bound in the superimposed CYP51 structures: 7RTQ (yellow), N. fowleri; 3GW9 (light blue) and 4G7G (orange), T. brucei; 4UYL (magenta) and 6CR2 (cyan—conformer A, sea green—conformer B), A. fumigatus; and 4Q2T (purple) and 4UHI (khaki) human CYP51. (A) Overall view from the lower P450 surface. The N. fowleri apoprotein ribbon and the heme are shown as markers; the FG loop is blue; and β1 strands are marked. (B) Enlarged view of the inhibitors.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we found that CYP51 from N. fowleri is a rather catalytically efficient enzyme that can catalyze 14α-demethylation of both obtusifoliol and lanosterol and has a relatively low susceptibility to inhibition. None of the tested antifungal drugs or experimental compounds acted as a functionally irreversible stoichiometric inhibitor. Among antifungals, the strongest inhibitory effect was displayed by posaconazole, while fluconazole and voriconazole (drugs that readily penetrate the blood–brain barrier and are sometimes used in PAM treatment schemes) were the weakest. Among our experimental compounds, two inhibitors whose potencies are close to that of posaconazole (FF-VNI and F-VFV) have been identified. Both FF-VNI and F-VFV were previously shown to be highly efficient in the treatment of mouse models of Chagas disease, were not toxic, and displayed favorable pharmacokinetics and broad tissue distribution.9 Most importantly, they both penetrate the blood–brain barrier: after multiple oral doses of 25 mg/kg twice a day; the average concentrations in the brain were 3.5 ± 0.3 and 2.2 ± 0.2 μM, respectively, and remained quite steady (Figure 11). Given that their minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values that we determined in the N. fowleri cellular growth inhibition assay (details in the Experimental Section) are below (FF-VNI, 2.7 μM, or 1.5 ± 0.1 μg/mL)) or close to (F-VFV, 3.3 μM, or 1.9 ± 0.2 μg/mL), the concentrations in the brain that were achieved at the described administration conditions, both of these compounds merit testing as potential drug candidates for the treatment of PAM. Higher doses can be administered, if necessary, because the NOAEL for each of them is >200 mg/kg9).

Figure 11.

FF-VNI and F-VFV penetrate the blood–brain barrier. Concentrations in the blood and brain after multiple doses. The compounds were given to mice by oral gavage, 25 mg/kg each 12 h for 5 days. The samples were taken 4 h after each administration. Graphs report the mean ± SEM.

Structural analysis of N.fowleri CYP51 in complex with F-VFV suggests that both the relaxed substrate requirements and lower susceptibility to inhibition of this enzyme can be associated with the relatively higher mobility of the BC (Arg108/Phe109) and FG loops. The binding of F-VFV to N. fowleri CYP51 in two different conformations is supported by comparative analysis of binding modes of other inhibitors in different CYP51 structures and implies that it is not only opening of a channel but a large-scale movement of the FG loop (or the whole FG arm) that accompanies entry of the substrates/inhibitory ligands into the CYP51 active site.

Finally, the observed gradient in the binding strength along the F-VFV molecule (Figure S3B) indicates that stronger, perhaps stoichiometric, inhibitors of N. fowleri CYP51 could be designed by minor modifications of the biphenyl arm through achieving a better fit to the deepest (and CYP51-specific33) portion of the active site cavity. Shortening of the opposite arm, the part of the molecule that is directed toward the protein surface, might also be possible (reduce the molecular weight, e.g., per Lipinski’s rules). On the other hand, the high potency of FF-VNI suggests that, alternatively, additional interactions at the protein surface could also be used to strengthen an inhibitor, e.g., as an important backup to circumvent possible acquired drug resistance.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemicals.

Large preparations of VNI, FF-VNI, VFV, and F-VFV were synthesized by the Chemical Synthesis Core Facility (Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology),34 and synthesis of their analogues CF3F-VNI and VFV-Cl has been described previously.9,10 The purity of the compounds was >95%. Voriconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); isavuconazole was from Sigma-Aldrich, and fluconazole was from ICN Biomedicals. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD) was purchased from Cyclodextrin Technology Development (Gainesville, FL). DEAE- and CM-Sepharose resins were from GE Healthcare, and Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate (NTA) agarose was purchased from Qiagen.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

Multiple protein sequence alignment was carried out in Clustal Omega and analyzed in GeneDoc. The phylogenetic tree was rendered in TreeDyn; branch support values (%) were generated in Phylogeny analysis (One Click mode: MUSCLE-Gblocks-PyML).35 The Discoba CYP51 sequences were N. fowleri (NCBI accession no. KAF0972476.1), Naegleria lovaniensis (KAG2389056.1, 98% identity), and N. gruberi (XP_002681678.1, 86% identity) [Heterolobosea]; T. brucei (XP_828695.1, 31% identity) and L. infantum (ABM89546.1, 30% identity) [Euglenozoa]. The Amoebozoa sequences were Acanthamoeba castellanii (XP_004334294.1, 38% identity), Acanthamoeba polyphaga (AMN14212.1, 38% identity), and Dictyostelium discoideum (XP_001134568.1, 36% identity). The algae sequences were Guillardia theta (XP_005826589.1, 39% identity), Nannochloropsis gaditana (EWM25289.1, 37% identity), and Chlorella sorokiniana (PRW59933.1, 35% identity). The plant sequences were Sorghum bicolor (XP_002442753.1, 35% identity), Vitis vinifera [grape] (XP_002271942.1, 36% identity), and Malus_domestica [apple] (XP_008390216.1, 36% identity). The animal sequences were Homo sapiens [human] (NP_000777.1, 33% identity); Gallus gallus [chicken] (XP_015136877.1, 33% identity), Xenopus tropicalis [frog] (NP_001016194.1, 33% identity), and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus [sea urchin] (NP_001001906.1, 32% identity). The fungal sequences were A. fumigatus CYP51B (XP_749134.1, 30% identity) and CYP51A (AAF32372.1, 28% identity), Fusarium graminearum CYP51B (ACL93392.1, 29% identity) and CYP51A (ACL93390.1, 28% identity); Trichophyton tonsurans CYP51B (EGD96940.1, 28% identity) and CYP51A (EGD95049.1, 28% identity); and C. albicans (XP_716761.1, 28% identity), and Cryptococcus neoformans (XP_566464.1, 27% identity).

N. fowleri CYP51 Gene Ordering and Expression Vector Construction.

The N. fowleri CYP51 gene (UniProtKB accession no. A0A6A5BCR7, gene no. FDP41_009379), codon-optimized for bacterial expression, was synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany), incorporating an NdeI restriction site at the 5’ end and a HindIII restriction site at the 3’ end of the gene cloned into the pUC57 plasmid. The first five amino acids were changed to MAIKA- (ATGGCTAATAAAGCT-),12 and a six-histidine extension (-CATCATCACCATCATCAC) was inserted before the stop codon (-TAA) to facilitate protein purification by NTA agarose affinity chromatography. This gene encoding the full-length CYP51 protein (485 amino acid residues plus the (His)6-tag, 56 200 Da, pI 8.6 (Antheprot)) was used for functional studies, including ligand binding, enzymatic activity, and inhibition assays. For crystallization purposes, the protein was truncated (466 amino acid residues, 53 500 Da, pI 9.0) as follows: the 36-amino acid membrane anchor sequence at the N-terminus (up to the conserved CYP51 proline Pro-37 in N. fowleri CYP51) was replaced with the 11-amino acid sequence fragment MAKKTSSKGKL- (ATGGCTAAGAAAACGAGCTC TAAAGGGAAGCTC-) as described previously for A. fumigatus CYP51.16 The functionality of this construct was verified prior to crystallization: the catalytic activity, substrate preferences, and susceptibility to inhibition were found to be similar to those of the full-length enzyme. For protein expression, both the full-length and truncated CYP51 genes were excised by NdeI/HindIII restriction digestion followed by cloning into the pCW expression vector using NEB T4 DNA ligase. Gene integrity was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein Expression and Purification.

N. fowleri CYP51 was expressed in Escherichia coli HMS-174 (DE3) (Novagen) and purified to electrophoretic homogeneity in two steps, including affinity chromatography (Ni2+-NTA agarose) and cation exchange chromatography (CM-Sepharose). In general, we followed the procedure described previously for A. fumigatus CYP51,16 except that the (NTA-) bound protein was eluted in 20 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), and 0.1 mM EDTA with a linear gradient of imidazole increasing from 45 to 100 mM, and the CM-bound protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mM NaCl. Recombinant rat NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) was purified as described elsewhere.36

Spectroscopic Characterization.

UV–visible absorption spectra were recorded at 22 °C using a dual-beam Shimadzu UV-240IPC spectrophotometer. The N. fowleri CYP51 concentration was determined from the Soret band absorbance in the absolute spectrum, using an absolute molar extinction coefficient ɛ417 = 117 mM−1 cm−1 for the low-spin oxidized (ferric, Fe3+) form of the protein or a difference molar extinction coefficient Δɛ(449–490) = 91 mM−1 cm−1 for the reduced carbon monoxide (Fe2+–CO) complex in the difference spectra.37 Difference spectra were generated by recording the P450 absorbance in a sample cuvette versus the absorbance in a reference cuvette, both containing the same amount of the protein. The spin state of the P450 samples was estimated from the absolute spectra as the ratio (ΔA393–470/ΔA417–470), with values of 0.35 and 2.0 corresponding to 100% low- and 100% high-spin iron, respectively.38

Spectral Ligand Binding Assays.

Spectral Binding Affinities Were Determined in Titration Experiments.

Titration with sterols was carried out at ~2 μM P450 concentration in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, in 1 cm optical path length cuvettes. Sterol substrate binding was monitored as a Type I spectral response reflecting hexacoordinated low- to pentacoordinated high-spin transition of the ferric P450 heme iron as a result of displacement of the heme-bound water molecule (a spectral shift in the Soret band maximum from 417 to 393 nm39). Aliquots of sterols dissolved in 45% HPCD, w/v,19 were added to the sample cuvette in the concentration range 0.25–4.0 μM (0.25–6.0 μM for norlanosterol), with each titration step being 0.25 μM. At each step, the corresponding volume of 45% HPCD was added to the reference cuvette.

Titration with azoles was carried out at ~0.5 μM P450 concentration in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 250 mM sodium chloride, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol, in 5 cm optical path length cuvettes. Inhibitor binding was monitored as a Type II spectral response, reflecting the coordination of the imidazole N3 nitrogen to the P450 heme iron (a shift in the Soret band maximum from 417 to 424 nm). Aliquots of azoles dissolved in DMSO were added to the sample cuvette in the concentration range 0.1–1.0 μM, with each titration step being 0.1 μM. At each step, the corresponding volume of DMSO was added to the reference cuvette.

The apparent spectral dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated in Prism 6 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) by fitting the data for the ligand-induced absorbance changes in the difference spectra Δ(Amax – Amin) versus ligand concentration to the quadratic Morrison equation (ΔA = (ΔAmax/2E)((L + E + Kd) − ((L + E + Kd)2 – 4LE)0.5), where [L] and [E] are the total concentrations of ligand and enzyme used for the titration, respectively, except for cycloartenol, where the better fit was achieved in fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

Catalytic Activity and Inhibition Assays.

The standard reaction mixture19 contained 0.5 μM N. fowleri CYP51 and 2.0 μM CPR, 100 μM L-α-1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine, 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.4 mg/mL isocitrate dehydrogenase, and 25 mM sodium isocitrate. After the addition of the radiolabeled ([3-3H]) sterol substrates (lanosterol or obtusifoliol, ~4,000 dpm/nmol; dissolved in 45% HPCD, w/v), the mixture was preincubated for 2 min at 37 °C in a shaking water bath, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 μM NADPH and stopped by extraction of the sterols with 5 mL of ethyl acetate. The extracted sterols were analyzed by a reversed-phase HPLC system (Waters) equipped with a β-RAM detector (INUS Systems). Time-course experiments were carried out at 50 μM concentrations of sterol substrates. For steady-state kinetic analysis, the reactions were run for 60 s at 37 °C, and the sterol concentration range was 3–50 μM. Michaelis–Menten parameters were calculated using GraphPad Prism, with reaction rates (nmol product formed/nmol P450/min) being plotted versus total substrate concentration.

The inhibitory potencies of clinical systemic antifungal azoles and our experimental compounds (VNI, VFV, and their analogues) were compared by determining their “1 h IC50” values (concentration required to prevent the conversion of 50% of the substrate (50 μM) in a 1 h reaction), an approach that allows identification of the most potent inhibitors.22 The values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6, with the percentage of substrate converted being plotted against inhibitor concentration and the curves fitted with nonlinear regression (log(inhibitor) vs normalized response).

N. fowleri Cellular Growth Inhibition Assay.

The experiments were performed following the protocol described in (40). Briefly, serial 2-fold dilutions of the drugs (12.5–0.5 μg/mL) were prepared in modified PYNFH medium (ATCC Medium 1034) and applied directly in sterile 96-well culture plates (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) containing 100 μL of N. fowleri trophozoites (104 cells/mL), and the plates were sealed and incubated at 37 °C for 4 days. Control wells received ATCC medium with DMSO. Cell growth was monitored on days 1–4 by counting cells in a cell counter. All tests were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Blood–Brain Permeability Assay.

The blood–brain concentrations of FF-VNI and F-VFV following multiple doses were monitored using a previously developed protocol that is based on the VNI-specific (oxadiazole ring) absorption maximum at 291 nm (ɛ291 = 36 mM−1 cm−1).24 Fresh solutions of the compounds were prepared from 10% stocks in DMSO by dissolving them in sterile 5% Arabic gum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3% Tween 80 (w/v)41 and given to BALB/c mice (50% male, 50% female, Jackson Laboratory) at 25 mg/kg by oral gavage twice a day for 5 days (two mice per group). Four hours after the first administration (and then every 12 h), two mice from each group were sacrificed; their blood and brains were collected and analyzed. For the blood analysis, 30 μL samples of plasma were diluted to 100 μL with PBS, mixed with 100 μL of CH3CN containing 10 μM VNI (used as an internal standard), the mixture was vortexed, and the drugs were extracted with 300 μL of an extraction solution containing 80% CH3CN and 20% water (v/v). After centrifugation at 16 000g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, dried, redissolved in 500 μL of a solvent composed of 50% CH3CN and 50% water (v/v), and injected into an HPLC system equipped with a dual-wavelength UV 2489 detector (Waters) set at 291 and 250 nm and a 4.6 mm × 75 mm Symmetry C18 (3.5 μm) octdecylsilane column. The mobile phase was 55% 0.015 M ammonium acetate, pH 7.4, and 45% CH3CN (v/v) with an isocratic flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. For the brain analysis, approximately 100 mg of the brain tissue was diluted 5-fold with PBS prior to drug extraction and homogenized using an IKA Ultra Turrax T8 tissue homogenizer (The Lab World Group), and 100 μL of the homogenate sample was used for the extraction and analysis, as described above for plasma. The identities of the extracted compounds were confirmed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) as described previously.41

Ethics.

The procedures involving mice were approved by the IACUC of Meharry Medical College.

Crystallization, Structure Determination, and Analysis.

Prior to crystallization, a 100 μM N. fowleri CYP51 protein in 20 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, EDTA, 5.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and 10% glycerol (v/v), was mixed with a 10 mM solution of F-VFV in DMSO (molar ratio enzyme/inhibitor 1:2), incubated 10 min at 4 °C, and concentrated to ~250 μM. Then, 0.34 mM n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (Hampton Research) was added, and the absorbance spectrum was taken to confirm that the Soret maximum was at 424 nm. Crystals were obtained at 20 °C by vapor diffusion in hanging drops containing 4 μL of the protein/inhibitor complex and 2 μL of reservoir solution (15% PEG 3350 (w/v), 5% isopropanol (v/v), and 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5), cryoprotected with 20% (v/v) glycerol in reservoir solution and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at 100 K using synchrotron radiation at the 21-ID-G beamline (0.97856 nm), Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. The diffraction images were indexed and integrated with iMOSFLM,42 scaled with Aimless (CCP4 Program Suite),43 and the structure was determined by molecular replacement with Phaser MR (CCP4) using T. brucei CYP51 (PDB ID 3G1Q) as a search model. The initial model was inspected and corrected using Coot44 and refined with Refmac5 (CCP4) (Table S1). The coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 7RTQ. Structure superimposition and RMSD calculation were done in LSQkab, (CCP4) using a secondary structure matching algorithm. The B-factor range was calculated in Pymol 2.5.1 (Schrodinger) and is used for coloring the inhibitor and protein segments in TOG (from blue (the lowest) to red (the highest)).

Estimation of Ligand Binding Affinities in MOE.

Because spectral titrations [that mostly reflect coordination of the basic azole nitrogen to the P450 heme iron] often provide Kd values that do not correlate with compound inhibitory potencies (as previously observed multiple times), we attempted to apply a computational approach using the program MOE28 to estimate binding affinities of the ligands for the apoprotein. The analogues were built in molecule A of 7RTQ using Builder based on the assumption that they adopt the same conformations in the N. fowleri CYP51 active site as does F-VFV. The structures were prepared and protonated using QuickPrep (default parameters) with the heme and a ligand fixed. The Fe–N bond was then deleted, the ligand was chosen, freed, and the iron-coordinated nitrogen atom tethered. The energy was minimized with Amber 10:EHT force field. The binding affinity was calculated as Gibbs free energy and converted into Kd values using the equation (ΔG = −RT ln Kd).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM067871 (G.I.L.). Synthesis of compounds at the Vanderbilt Chemical Synthesis Core Facility was supported by R01 GM067871-15S1 (Administrative Supplement) (G.I.L.). Synthesis of the sterols was supported by R33 AI119782 (W.D.N.). Vanderbilt University is a member institution of the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team at Sector 21 of the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL). Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CYP51

sterol 14α-demethylase

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FCF3-VNI

(R)-N-(1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-(3-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide

- FF-VNI

(R)-N-(1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-ethyl)-4-(5-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-benzamide

- F-VFV

(R)-N-(2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-(3,4’,5-trifluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide

- HPCD

hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

- IC50

inhibitor concentration required to prevent conversion of 50% of the substrate in a 1 h reaction

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- VFV

(R)-N-(1-(3,4’-difluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide

- VFV-Cl

(R)-N-(1-(3-chloro-4’-fluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-( 1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide

- VNI

(R)-N-(1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01710.

Molecular formula strings for VNI, FF-VNI, FCF3-VNI, VFV, F-VFV, and VFV-Cl (CSV);

complete alignment of CYP51 sequences (Figure S1); comparative hyperbolic fitting parameters for N. fowleri CYP51 binding of obtusifoliol, norlanosterol, lanosterol, and cycloartenol (Figure S2); N. fowleri CYP51 structure colored by B-factor, an overall view and the B-factor range along the inhibitor molecule (Figure S3); calculated interactions between the protein and VNI/VFV analogues (Figure S4); predicted binding mode of VFV-Cl vs VFV, and F-VFV (Figure S5); ligand omit map for F-VFV (Figure S6); data collection and refinement statistics (Table S1); statistics for IC50 calculations (Table S2); and HPLC profiles for the compounds (Table S3) (PDF)

Accession Codes

The PDB code for N. fowleri CYP51 with bound F-VFV is 7RTQ.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01710

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Tatiana Y. Hargrove, Department of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, United States

Zdzislaw Wawrzak, Synchrotron Research Center, Life Science Collaborative Access Team, Northwestern University, Argonne, Illinois 60439, United States.

Girish Rachakonda, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Physiology, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee 37208, United States.

W. David Nes, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, United States.

Fernando Villalta, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Physiology, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee 37208, United States.

F. Peter Guengerich, Department of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, United States.

Galina I. Lepesheva, Department of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, United States; Center for Structural Biology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37232, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Maciver SK; Piñero JE; Lorenzo-Morales J Is Naegleria fowleri an Emerging Parasite? Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kemble SK; Lynfield R; DeVries AS; Drehner DM; Pomputius WF III; Beach MJ; Visvesvara GS; da Silva AJ; Hill VR; Yoder JS; Xiao L; Smith KE; Danila R Fatal Naegleria fowleri Infection Acquired in Minnesota: Possible Expanded Range of a Deadly Thermophilic Organism. Clin. Infect. Dis 2012, 54, 805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Linam WM; Ahmed M; Cope JR; Chu C; Visvesvara GS; da Silva AJ; Qvarnstrom Y; Green J Successful Treatment of an Adolescent with Naegleria fowleri Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e744–e748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gharpure R; Gleason M; Salah Z; Blackstock AJ; Hess-Homeier D; Yoder JS; Ali IKM; Collier SA; Cope JR Geographic Range of Recreational Water-Associated Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis, United States, 1978-2018. Emerging Infect. Dis 2021, 27, 271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gharpure R; Bliton J; Goodman A; Ali IKM; Yoder J; Cope JR Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria fowleri: A Global Review. Clin. Infect. Dis 2021, 73, e19–e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lepesheva GI; Friggeri L; Waterman MR CYP51 as Drug Targets for Fungi and Protozoan Parasites: Past, Present and Future. Parasitology 2018, 145, 1820–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Raederstorff D; Rohmer M Sterol Biosynthesis via Cycloartenol and Other Biochemical Features Related to Photosynthetic Phyla in the Amoeba Naegleria lovaniensis and Naegleria gruberi. Eur. J. Biochem 1987, 164, 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zhou W; Debnath A; Jennings G; Hahn HJ; Vanderloop BH; Chaudhuri M; Nes WD; Podust LM Enzymatic Chokepoints and Synergistic Drug Targets in the Sterol Biosynthesis Pathway of Naegleria fowleri. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, No. e1007245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Friggeri L; Hargrove TY; Rachakonda G; Blobaum AL; Fisher P; de Oliveira GM; da Silva CF; Soeiro MNC; Nes WD; Lindsley CW; Villalta F; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Sterol 14α-Demethylase Structure-Based Optimization of Drug Candidates for Human Infections with the Protozoan Trypanosomatidae. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 10910–10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Friggeri L; Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Blobaum AL; Rachakonda G; Lindsley CW; Villalta F; Nes WD; Botta M; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Sterol 14α-Demethylase Structure-Based Design of VNI ((R)- N-(1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)benzamide)) Derivatives to Target Fungal Infections: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Crystallographic Analysis. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 5679–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lepesheva GI; Waterman MR Structural Basis for Conservation in the CYP51 Family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2011, 1814, 88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lepesheva GI; Zaitseva NG; Nes WD; Zhou W; Arase M; Liu J; Hill GC; Waterman MR CYP51 from Trypanosoma cruzi: a Phyla-Specific Residue in the B’ Helix Defines Substrate Preferences of Sterol 14α-Demethylase. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 3577–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lamb DC; Hargrove TY; Zhao B; Wawrzak Z; Goldstone JV; Nes WD; Kelly SL; Waterman MR; Stegeman JJ; Lepesheva GI Concerning P450 Evolution: Structural Analyses Support Bacterial Origin of Sterol 14α-Demethylases. Mol. Biol. Evol 2021, 38, 952–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Fisher PM; Child SA; Nes WD; Guengerich FP; Waterman MR; Lepesheva GI Binding of a Physiological Substrate Causes Large-Scale Conformational Reorganization in Cytochrome P450 51. J. Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 19344–19353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI A Requirement for an Active Proton Delivery Network Supports a Compound I-Mediated C-C Bond Cleavage in CYP51 Catalysis. J. Biol. Chem 2020, 295, 9998–10007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Lamb DC; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Structure-Functional Characterization of Cytochrome P450 Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51B) from Aspergillus fumigatus and Molecular Basis for the Development of Antifungal Drugs. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 23916–23934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cherkesova TS; Hargrove TY; Vanrell MC; Ges I; Usanov SA; Romano PS; Lepesheva GI Sequence Variation in CYP51A From the Y Strain of Trypanosoma cruzi Alters its Sensitivity to Inhibition. FEBS Lett. 2013, 588, 3878–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Omura T; Sato R The Carbon Monoxide-Binding Pigment of Liver Microsomes. II. Solubilizatiom, Purification, and Properties. J. Biol. Chem 1964, 239, 2379–2385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lepesheva GI; Nes WD; Zhou W; Hill GC; Waterman MR CYP51 from Trypanosoma brucei is obtusifoliol-specific. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 10789–10799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Alexander PW; Chaplin JH; Keenan M; Charman SA; Perez CJ; Waterman MR; Chatelain E; Lepesheva GI Complexes of Trypanosoma cruzi sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) with Two Pyridine-Based Drug Candidates for Chagas disease: Structural Bbasis for Pathogen Selectivity. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 31602–31615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lepesheva GI; Ott RD; Hargrove TY; Kleshchenko YY; Schuster I; Nes WD; Hill GC; Villalta F; Waterman MR Sterol 14α-Demethylase as a Potential Target for Antitrypanosomal Therapy: Enzyme Inhibition and Parasite Cell Growth. Chem. Biol 2007, 14, 1283–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Friggeri L; Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Validation of Human Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) Druggability: Structure-Guided Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Stoichiometric, Functionally Irreversible Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 10391–10401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tiewcharoen S; Junnu V; Chinabut P In vitro Effect of Antifungal Drugs on Pathogenic Naegleria spp. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2002, 33, 38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Villalta F; Dobish MC; Nde PN; Kleshchenko YY; Hargrove TY; Johnson CA; Waterman MR; Johnston JN; Lepesheva GI VNI Cures Acute and Chronic Experimental Chagas Disease. J. Infect. Dis 2013, 208, 504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lepesheva GI; Park HW; Hargrove TY; Vanhollebeke B; Wawrzak Z; Harp JM; Sundaramoorthy M; Nes WD; Pays E; Chaudhuri M; Villalta F; Waterman MR Crystal Structures of Trypanosoma brucei Sterol 14α-Demethylase and Implications for Selective Treatment of Human Infections. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 1773–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yu X; Cojocaru V; Mustafa G; Salo-Ahen OM; Lepesheva GI; Wade RC Dynamics of CYP51: Implications for Function and Inhibitor Design. J. Mol. Recognit 2015, 28, 59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cojocaru V; Winn PJ; Wade RC The Ins and Outs of Cytochrome P450s. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj 2007, 1770, 390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2020.09; Chemical Computing Group ULC: 1010 Sherbrooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lepesheva GI; Hargrove TY; Anderson S; Kleshchenko Y; Furtak V; Wawrzak Z; Villalta F; Waterman MR Structural Insights Into Inhibition of Sterol 14α-Demethylase in the Human Pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 25582–25590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Andriani G; Amata E; Beatty J; Clements Z; Coffey BJ; Courtemanche G; Devine W; Erath J; Juda CE; Wawrzak Z; Wood JT; Lepesheva GI; Rodriguez A; Pollastri MP Antitrypanosomal Lead Discovery: Identification of a Ligand-Efficient Inhibitor of Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 and Parasite Growth. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 2556–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Friggeri L; Hargrove TY; Rachakonda G; Williams AD; Wawrzak Z; Di Santo R; De Vita D; Waterman MR; Tortorella S; Villalta F; Lepesheva GI Structural Basis for Rational Design of Inhibitors Targeting Trypanosoma cruzi Sterol 14α-Demethylase: Two Regions of the Enzyme Molecule Potentiate its Inhibition. J. Med. Chem 2013, 57, 6704–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hargrove TY; Friggeri L; Wawrzak Z; Qi A; Hoekstra WJ; Schotzinger RJ; York JD; Guengerich FP; Lepesheva GI Structural Analyses of Candida albicans Sterol 14α-Demethylase Complexed with Azole Drugs Address the Molecular Basis of Azole-Mediated Inhibition of Fungal Sterol Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292, 6728–6743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lepesheva GI Design or Screening of Drugs for the Treatment of Chagas Disease: What Shows the Most Promise? Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2013, 8, 1479–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lepesheva G; Christov P; Sulikowski GA; Kim K A Convergent, Scalable and Stereoselective Synthesis of Azole CYP51 Inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4248–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Dereeper A; Audic S; Claverie J-M; Blanc G Blast-Explorer Helps You Building Datasets for Phylogenetic Analysis. BMC Evol. Biol 2010, 10, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hanna IH; Teiber JF; Kokones KL; Hollenberg PF Role of the Alanine at Position 363 of Cytochrome P450 2B2 in Influencing the NADPH- and Hydroperoxide-Supported Activities. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1998, 350, 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hargrove TY; Wawrzak Z; Liu J; Nes WD; Waterman MR; Lepesheva GI Substrate Preferences and Catalytic Parameters Determined by Sstructural Characteristics of Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) from Leishmania infantum. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 26838–26848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lepesheva GI; Strushkevich NV; Usanov SA Conformational Dynamics and Molecular Interaction Reactions of Recombinant Cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) Detected by Fluorescence Energy Transfer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol 1999, 1434, 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Schenkman JB; Remmer H; Estabrook RW Spectral Studies of Drug Interaction with Hepatic Microsomal Cytochrome. Mol. Pharmacol 1967, 3, 113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kim JH; Jung SY; Lee YJ; Song KJ; Kwon D; Kim K; Park S; Im KI; Shin HJ Effect of Therapeutic Chemical Agents in vitro and on Experimental Meningoencephalitis Due to Naegleria fowleri. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 4010–4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lepesheva GI; Hargrove TY; Rachakonda G; Wawrzak Z; Pomel S; Cojean S; Nde PN; Nes WD; Locuson CW; Calcutt MW; Waterman MR; Daniels JS; Loiseau PM; Villalta F VFV as a New Effective CYP51 Structure-Derived Drug Candidate for Chagas Disease and Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis 2015, 212, 1439–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Battye TG; Kontogiannis L; Johnson O; Powell HR; Leslie AG iMOSFLM: a New Graphical Interface for Diffraction-Image Processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Winn MD; Ballard CC; Cowtan KD; Dodson EJ; Emsley P; Evans PR; Keegan RM; Krissinel EB; Leslie AG; McCoy A; McNicholas SJ; Murshudov GN; Pannu NS; Potterton EA; Powell HR; Read RJ; Vagin A; Wilson KS Overview of the CCP4 Suite and Current Developments. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and Development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.