Abstract

Mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene are involved in the family cancer syndrome for which it is named and the development of sporadic renal cell cancer (RCC). Reintroduction of VHL into RCC cells lacking functional VHL [VHL(−)] can suppress their growth in nude mice, but not under standard tissue culture conditions. To examine the hypothesis that the tumor suppressor function of VHL requires signaling through contact with extracellular matrix (ECM), 786-O VHL(−) RCC cells and isogenic sublines stably expressing VHL gene products [VHL(+)] were grown on ECMs. Cell-cell and cell-ECM signalings were required to elicit VHL-dependent differences in growth and differentiation. VHL(+) cells differentiated into organized epithelial sheets, whereas VHL(−) cells were branched and disorganized. VHL(+) cells grown to high density on collagen I underwent growth arrest, whereas VHL(−) cells continued to proliferate. Integrin levels were up-regulated in VHL(−) cells, and cell adhesion was down-regulated in VHL(+) cells during growth at high cell density. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α, a transcription factor and global activator of proximal tubule-specific genes in the nephron, was markedly up-regulated in VHL(+) cells grown at high cell density. These data indicate that VHL can induce renal cell differentiation and mediate growth arrest through integration of cell-cell and cell-ECM signals.

Mutations of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene are involved in the family cancer syndrome for which it is named and the development of sporadic renal cancer and renal cystic disease (for review, see reference 15). VHL has no significant homology to previously identified proteins (21). Insights into the biochemistry of VHL have come predominantly from the identification of proteins that associate with VHL products (9, 17, 19, 26, 29, 34). These include elongins B and C (9, 12, 19, 37), cul-2 (26, 34), and Rbx1 (17), which are similar to components of a yeast E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (2, 16, 26, 34). A current hypothesis for VHL activity is that it functions as an F-box protein, directing specific substrates for ubiquitination. Indeed, VHL has been shown to have in vitro ubiquitin ligase activity (13, 25) and to target HIF-1α, a hypoxia inducible transcription factor, for proteasomal degradation (7, 18, 28, 38). However, the exact biochemical function(s) of VHL that is disrupted in VHL disease and which results in susceptibility to clear renal cell cancer (RCC) remains elusive.

Alterations of cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions are associated with renal cystic disease (for review, see references 4, 10, and 40). A role for VHL in the synthesis and degradation of ECM has begun to emerge. VHL was found to associate with intracellular fibronectin and was required for assembly of extracellular fibronectin (29). VHL also controls matrix degradation by regulating both matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and their inhibitors (20), as well as the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system (27).

Previous studies indicated that reintroduction of VHL into carcinoma cells lacking functional VHL [VHL(−)] leads to growth suppression in nude mice but not in cells grown under standard culture conditions (11, 33, 37). In addition, VHL-deficient RCC cells ectopically expressing VHL demonstrated morphological differentiation and growth arrest when grown as multicellular tumor spheroids, but not under standard culture conditions (23). These studies suggest the importance of the extracellular milieu to elicit biological functions of VHL.

In this report, we describe VHL function in the context of cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions. These studies demonstrate that VHL-dependent morphological and biochemical differentiation requires the establishment of high-density cell-cell contact and, in combination with cell-ECM interactions, results in VHL-dependent growth arrest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture.

The VHL(−) cell lines consist of the parental renal carcinoma cell line, 786-O, and its derivative lines containing either the empty expression vector pCR3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) or a nonfunctional VHL deletion construct, VHL(MPR)del(114–178) (37). The VHL(+) cell lines consist of 786-O derivative lines stably expressing the VHLp24(MPR) or the VHLp18(MEA) constructs as previously described (37). At least two independent clones were analyzed for each construct. Cells were grown in 10-cm-diameter dishes in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum. Stable transfectants were maintained in medium supplemented with 0.6 mg of G418 (Life Technology, Rockville, Md.)/ml. Medium was replenished every 2 to 3 days. To condition cells at high density, cells were allowed to grow for 1 week postconfluency with media replenishment every 24 to 48 h. To condition cells at low density, cells were maintained at 30 to 70% confluency for 1 week by frequent passaging.

Growth of cells on Matrigel.

To prepare a thin layer of Matrigel, 300 μl of liquefied Matrigel (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, Mass.) was spread evenly in the wells of 12-well plates (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) precooled on ice. The plates were then placed at 37°C for 30 min to allow the Matrigel to solidify. Aliquots containing 7 × 104 cells were plated in Matrigel-coated 22-mm wells. To inhibit surface integrin activity, ascites preparations of monoclonal antibodies P4C10 and P4G9 (Life Technologies) against β1 and α4 integrins, respectively, were diluted 1:50 in 1 ml of growth media containing 106 suspended cells. Following a 1-h incubation at room temperature, cells and diluted ascites fluid were plated onto thin layers of Matrigel and incubated at 37°C.

Double thymidine block.

To arrest cells at the G1-S border in the cell cycle, a double thymidine block was performed as previously described (14). Briefly, cells maintained for 1 week at 50 to 70% confluency were cultured for 17 h in medium containing 2 mM thymidine, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cultured for 9 h without thymidine. Thereafter, cells were incubated for an additional 17 h in the presence of 2 mM thymidine. Cells were detached with trypsin and counted. An aliquot of cells was taken for cell cycle analysis by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), as described below. Each cell line was analyzed in triplicate for each growth condition.

Image analysis.

A Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope equipped with an environmental chamber was used to photograph cells by using 10× (phase 1; numerical aperture, 0.30 planapo) and 4× (phase L; numerical aperture, 0.13 planapo) objectives. For video capture, an NEC TI-23A charge-coupled device (CCD) camera digitized with a Scion LG-3 video board in a Power Macintosh running NIH-Image was used. For still photography, a Nikon N6000 35 mm camera was used. To collect images by using Nomarski optics, a Photometrics (Tucson, Ariz.) KAF 1400 12-bit cooled CCD camera on an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope was used with a 20× objective (numerical aperture, 0.40 planapo) and I.P. Lab Spectrum software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, Va.). Images were deconvolved with Power Hazebuster software (Vaytek, Fairfield, Iowa) on a Power Macintosh. All images were captured at the Analytical Imaging Facility at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Scanning electron microscopy.

Cells cultured at confluency for 1 week were dislodged with trypsin and plated on glass-bottom wells at high density. After 2 days of growth, the cells were washed twice with PBS and were then immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4). The cells were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes and were critical-point dried using liquid carbon dioxide in a Samdri 790 Critical Point Drier (Tousimis Research Corp., Rockville, Md.). The cells were sputter coated with gold-palladium in a Vacuum Desk-1 Sputter Coater (Denton Vacuum Inc., Cherry Hill, N.J.) and examined in a JSM6400 Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL, Peabody, Mass.) using an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Macroscopic colony morphology assay.

The 786-O cell line was transfected with the VHLp24(MPR) construct in a 35-mm-diameter dish by using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies), as recommended by the manufacturer. Three days after transfection, one-tenth of the cells were plated in a 10-cm-diameter dish and selected with 1.2 mg of G418 (Life Technologies)/ml for 1 month. A Foto/Eclipse image analysis system (Fotodyne, Hartland, Wis.) was used for the video capture of the image.

Cell growth on collagen I and plastic for cell cycle analysis.

To prepare collagen I-coated plates, rat tail collagen I (Becton Dickinson) was diluted 1:2 and neutralized with 0.1 N NaOH, as recommended by the manufacturer. Each 10-cm-diameter plate was coated with 2.5 ml of collagen I solution and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow the collagen I to gel. Cells were plated in triplicate, and medium was replenished daily after cells reached confluency.

To collect cells for analysis, cells grown on plastic were dislodged with 5 mg of trypsin/ml, whereas cells grown on collagen I were dislodged with 25 mg of trypsin/ml and 5 mg of collagenase I (Life Technologies)/ml. Cells were washed once with 5 ml of growth medium, washed once with 5 ml of PBS, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS. One-half of the cell suspension was used to make lysates for immunoblot analysis (see below), and the remainder was utilized for flow cytometry. For analysis by flow cytometry, 5 ml of 80% ethanol was added and the cells were fixed overnight at 4°C. The cells were then spun down, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS containing 10 μg of propidium iodide/ml and 250 μg of ribonuclease A (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml. After a 1- to 3-h incubation at room temperature, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.). CellQUEST software was used for instrument control, data acquisition, and analysis. Cell cycle modeling was performed using ModFIT (Verity Software House, Topsham, Maine).

Western blotting.

Cell lysates were prepared by washing cells twice with PBS and lysing cells with 1 ml of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 200 mM dithiothreitol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol) per 10-cm plate. Lysates were heated for 10 min at 100°C, sonicated, and assayed for protein concentration by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Monoclonal antibodies against leucine aminopeptidase (B-F10; NeoMarkers, Union City, Calif.), hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF-1α), α5 integrin, β1 integrin (Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, Calif.), and α3 integrin (P1B5) (Life Technologies Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) and monoclonal antibody against VHL (11E12) (37) were prepared, and those prchased commercially were used as recommended by the manufacturers.

Analysis of surface expression of β1 integrin by flow cytometry.

Cell lines were grown on plastic culture dishes for 7 days at 30 to 70% confluence and for seven additional days after attaining confluence. Cell lines were grown in triplicate, and each plate was analyzed in triplicate. Cells were washed twice with PBS, suspended in PBS–0.1% EDTA, and blocked for 1 h in 1% fetal calf serum in PBS. Samples containing 5 × 105 cells from each cell line were incubated with 5 μl of TDM-29 antibody labeled with phycoerythrin (Southern Biotechnology) for 1 h in 0.5 ml of blocking buffer, washed two times with blocking buffer, and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.5). All procedures from cell blocking through cell fixation were performed at 4°C. A FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems) was used to perform the analysis. Background values from negative controls (no phycoerythrin-labeled antibody) were subtracted from the results of the tested cell lines.

Adhesion assay.

Thin collagen I gels were applied to the wells of a 96-well culture plate (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) by using 50 μl of a neutralized 2-mg/ml collagen I solution per well (Becton Dickinson). VHL(+) and VHL(−) cell lines were maintained at low density or at confluency for a week, suspended with trypsin-EDTA, counted, plated at 5 × 104 cells per well in 100 μl of growth medium, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Each line was grown and analyzed in triplicate. The wells were washed three times with growth medium and incubated with 1 mg of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma) per ml in DMEM (no serum) at 37°C for 1 h. The wells were washed once with DMEM, and 100 μl of N-propanol (Fischer) was added to dissolve the color indicator. The absorbance at 570 nm was read on an MRX microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Chantilly, Va.). Background values (wells with no cells) were subtracted from the test values.

RESULTS

VHL and cell-cell signaling regulate cell morphology.

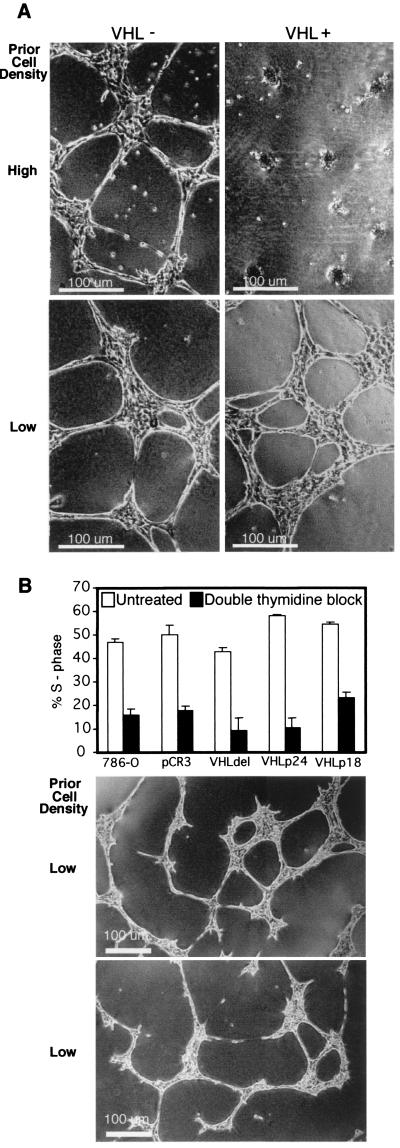

To test the notion that cell-ECM interactions are necessary to elicit growth control properties of VHL, the 786-O VHL(−) cell line and isogenic derivatives expressing VHL constructs were grown on Matrigel, a basement membrane preparation, to recapitulate growth conditions in vivo. Two different phenotypes were observed within the first 20 h of cell growth on Matrigel. Cells without functional VHL consistently aligned, elongated, and spread to form a web-like pattern (Fig. 1A, upper left). In contrast, VHL(+) cells formed clusters of rounded cells (Fig. 1A, upper right). Variability in the phenotype of the VHL(+) cells plated on Matrigel was observed (Fig. 1A, right). To define the conditions required to elicit the VHL(+) phenotype, the influence of cell-cell contacts prior to growth on Matrigel was studied. Cells were maintained for 1 week at either low or high density and then were plated on Matrigel. VHL(+) cells maintained at high density formed clusters on Matrigel (Fig. 1A, upper right). However, cells maintained at low density formed a web-like pattern similar to those formed by the VHL(−) lines (Fig. 1A, lower right). These data indicated that the VHL(+) phenotype was dependent on cell density prior to plating the cells on Matrigel.

FIG. 1.

Influence of VHL expression and cell density on cell morphology. (A) Representative VHL(−) (left) and VHL(+) (right) 786-O RCC cell lines were maintained at high cell density (above) and low cell density (below) prior to plating on thin layers of Matrigel. Images were captured 20 h after cells were plated on Matrigel. (B) VHL(+) and VHL(−) lines were grown at low cell density, subjected to a double thymidine block, and analyzed by flow cytometry for cell cycle progression. Percentages of untreated cells and thymidine-treated cells in S phase are shown. Representative results are shown for the cell line stably expressing VHLp24(MPR) (untreated, middle panel; thymidine treated, lower panel).

To distinguish whether the VHL(+) phenotype was dependent upon cell-cell interactions or upon inhibition of the cell cycle by dense growth, a double thymidine block was used to arrest actively growing VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells. Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry confirmed that the growth of thymidine-treated cells was inhibited (Fig. 1B) compared to the growth of the untreated cells. Nevertheless, cells grown at low density displayed a similar phenotype on Matrigel irrespective of thymidine treatment or VHL expression. Representative results are shown for the 786-O cell line stably expressing VHLp24(MPR) (Fig. 1B, untreated cells, middle panel; thymidine-treated cells, lower panel). These results suggest that cell-cell contact and not cell cycle differences are responsible for the VHL-mediated clustering of cells on Matrigel.

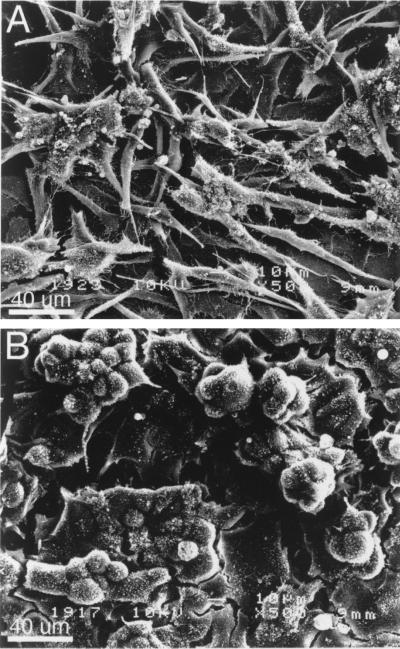

The necessity for high cell density to elicit a VHL-dependent phenotype prompted studies on the roles of cell-cell contact and VHL expression on cell growth in the absence of exogenous matrix. The morphologic appearances and growth properties of VHL(−) and VHL(+) cells are similar when maintained under standard culture conditions (9, 11, 37; data not shown). Scanning electron microscopy of cells grown at high density revealed striking morphological differences that paralleled the phenotypes observed on Matrigel (Fig. 2). VHL(−) cells growing above the monolayer were elongated, scattered, and branched (Fig. 2A), whereas VHL(+) cells growing above the monolayer were clustered and spherical (Fig. 2B). Thus, growth at high cell density coupled with VHL expression, in the absence of exogenous ECM, was sufficient to cause significant VHL-dependent changes in cell morphology.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of cells growing above the monolayer is dependent on VHL expression. Representative VHL(−) cells (A) and VHL(+) cells (B) grown at high density were plated on glass coverslips, grown for 2 days, and examined in a JSM6400 Scanning Electron Microscope.

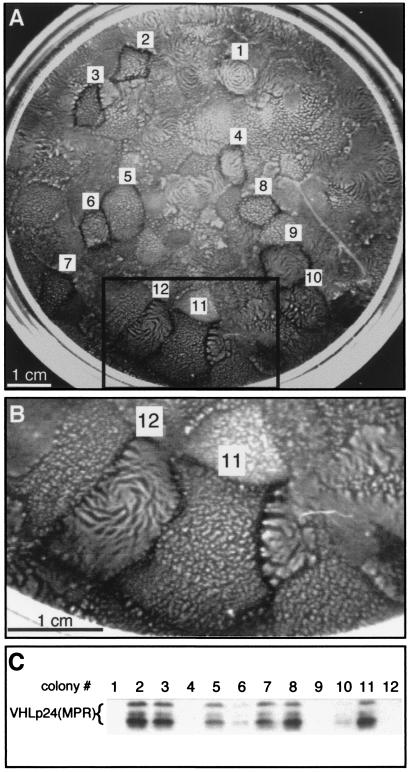

VHL and cell-cell signaling regulate the macroscopic organization of cells.

The VHL-dependent morphologic alterations of cells at high cell density suggested that multicellular organization might also be affected by VHL expression. To study the influence of VHL in the morphogenesis of multicellular architecture, the development of VHL(+) and VHL(−) colonies was observed during prolonged growth on plastic culture dishes (Fig. 3). 786-O cells were transfected with the VHLp24(MPR) expression construct and selected for 4 weeks with G418 (Fig. 3A). Dramatic VHL-dependent differences in colony morphology were observed. Two basic phenotypes developed and are exemplified by colonies 11 and 12 (Fig. 3B). Colonies similar to colony 11 had multiple clusters of cells growing above the monolayer, whereas those similar to colony 12 had dense ridges of cells rising above the monolayer, often forming spirals. To relate these phenotypes to VHL expression, 12 colonies were selected for VHL immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3C). Colonies expressing high levels of VHLp24(MPR) protein (colonies 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8) had morphologies similar to that of colony 11, whereas colonies expressing no VHLp24(MPR) protein (1, 4, and 9) had morphologies similar to that of colony 12. Colonies 6 and 10 expressed low levels of VHLp24(MPR) and displayed an intermediate phenotype. Thus, the expression of VHL altered macroscopic colony morphology during prolonged growth, and the magnitude of VHL expression modulated the extent to which the morphology was modified.

FIG. 3.

Macroscopic colony morphology is dependent on VHL expression. (A) 786-O cells were transfected with the VHLp24(MPR) construct and selected for 4 weeks with 1.2 mg of G418/ml. A Fotodyne Foto/Eclipse video capture system was used to acquire the image of the plate. Twelve colonies with distinct morphologies (labeled 1 to 12) were isolated using cloning cylinders. (B) Enlargement of boxed area in panel A. (C) Lysates from cell lines derived from the 12 colonies were screened for VHL expression by immunoblotting using monoclonal antibody 11E12 37. Forty micrograms of lysate was loaded in each lane. VHLp24(MPR) bands are indicated by a bracket.

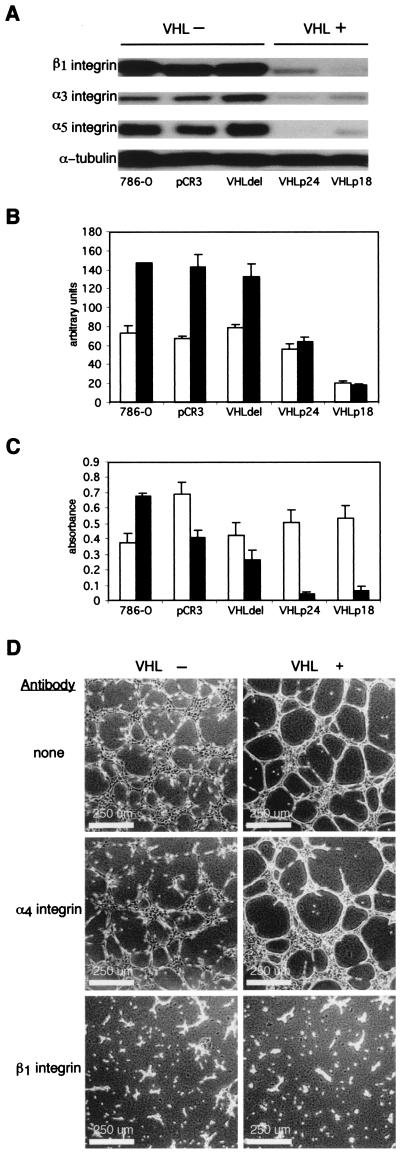

VHL and cell-cell signaling regulate integrin levels and activity.

In order to study possible mechanisms by which VHL and cell density may influence cell morphology, integrin expression and cell adhesion were assayed. VHL(+) cells had reduced levels of β1, α3, and α5 integrins compared to the levels of the VHL(−) cells when cells were grown for 10 additional days after attaining 100% confluence (Fig. 4A). The relationship between cell density and integrin expression was further studied by flow cytometry to determine the surface expression of β1 integrin (Fig. 4B) on subconfluent cells and cells grown for an additional 7 days after attaining confluence. At high cell density, surface β1 integrin levels increased in VHL(−) cells but were unchanged in VHL(+) cells. Thus, VHL maintains surface levels of β1 integrin that would otherwise be up-regulated by growth at high cell density.

FIG. 4.

Influence of VHL expression and cell density on integrin expression and cell adhesion. (A) Whole-cell lysates were made from VHL(−) and VHL(+) cells grown for an additional 10 days after attaining confluence. Monoclonal antibodies against α5 and β1 integrins (Transduction Laboratories) and antibody P1B5 against α3 integrin (Life Technologies) were used to detect integrin expression by immunoblotting. Thirty micrograms of lysate was loaded in each lane, and monoclonal antibody DM1A against α-tubulin was used to confirm equal loading. (B) Flow cytometry was performed on cells grown at low density (white) and high density (black) using monoclonal antibody TDM-29 conjugated to phycoerythrin (Southern Biotechnology) to detect the surface expression of β1 integrin. (C) Adhesion assays of low-density cells (white) and high-density cells (black) to thin layers of collagen I gels were performed in a 96-well plate. VHL(+) and VHL(−) cell lines were maintained at low and high density, plated in triplicate at 5 × 104 cells per well, and allowed to adhere for 30 min. Wells were washed three times, and a colorimetric assay was performed with 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide to determine relative quantities of adherent cells by using an MRX microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories). (D) VHL(+) and VHL(−) cell lines maintained at low cell density on plastic were incubated in suspension with blocking antibody against α4 integrin P4G9, with blocking antibody against β1 integrin P4C10 (Life Technologies), or with no antibody, and then cells were plated on thin layers of Matrigel. Images were captured 10 h after plating on Matrigel.

The ability of integrins to mediate adhesion is dependent not only on their abundance on the cell membrane but also on their state of activation. Therefore, cell adhesion to collagen I was assayed as an indicator of integrin function (Fig. 4C). In cell adhesion assays, VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells maintained under subconfluent conditions (Fig. 4C) were similarly adhesive to collagen I, consistent with their phenotype on Matrigel (Fig. 1A, bottom). However, adhesion of VHL(+) cells was markedly reduced for cells conditioned by growth for seven additional days after attaining confluence (Fig. 4C), consistent with their phenotype on Matrigel (Fig. 1A, right top). Moreover, cells preconditioned at low density, which spread on Matrigel (Fig. 4D, top), were inhibited from spreading when treated with blocking antibodies to β1 integrin (Fig. 4D, bottom), whereas treatment with a control antibody had no effect (Fig. 4D, middle). VHL(+) cell adhesion to collagen I and cell spreading on Matrigel were highly dependent on cell density and were inhibited by blocking antibodies to β1 integrin, whereas surface expression of β1 integrin on the VHL(+) cells was unaffected by cell density, thus suggesting that β1 integrin-associated activity is regulated by VHL.

VHL, cell-cell signaling, and cell-ECM signaling direct morphological differentiation.

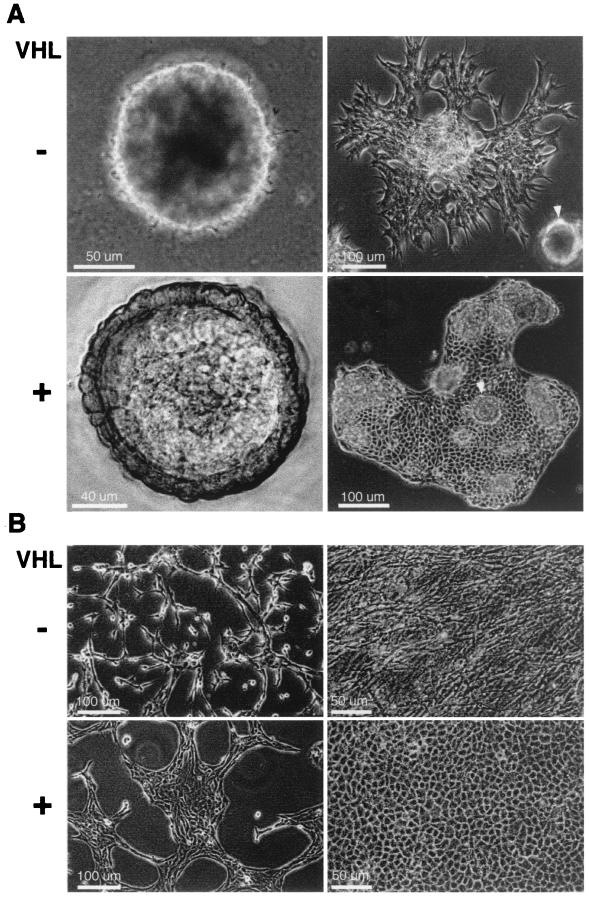

During prolonged growth on Matrigel, VHL(−) and VHL(+) cells developed distinct patterns of multicellular organization. After 5 to 7 days of growth on Matrigel, both VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells contracted into large aggregates (Fig. 5A, left). The aggregates of VHL(−) cells grew as dense spheres without an organized structure or discernible cell morphology (Fig. 5A, upper left). In contrast, the VHL(+) cells grew into organized structures characterized by a flat round center surrounded by a raised outer rim in which cell boundaries were clearly seen (Fig. 5A, lower left). By 12 days of growth on Matrigel, cells began to grow out of the aggregates (Fig. 5A, right). The VHL(−) cells were branched and disorganized (Fig. 5A, upper right), whereas the VHL(+) cells were polygonal, were tightly associated, and grew as a coherent epithelial sheet (Fig. 5A, lower right). These results indicated that during growth for several days with cell-cell contact, VHL expression was required for Matrigel-cell signaling to direct the formation of organized structures and an epithelial-like morphology.

FIG. 5.

Influence of VHL expression and ECM substrate on morphological differentiation. (A) Representative VHL(−) (above) and VHL(+) (below) cells were plated on Matrigel and grown for 7 or 12 days (left and right, respectively). Arrowheads (right) indicate structures similar to those shown on the left. (B) Representative VHL(−) (above) and VHL(+) (below) cells were plated on thin gels of polymerized collagen I and grown at low density (left) and high density (right). Images were captured on film using a Nikon Diaphot inverted phase microscope equipped with an environmental chamber except for one in panel A (lower left). Nomarski optics were used to capture this image with a Photometrics cooled CCD camera on an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope and deconvolved with Power Hazebuster software on a Power Macintosh computer.

To determine whether specific ECMs could elicit the VHL-dependent phenotypes observed on Matrigel, several homogenous ECM preparations were tested to elicit VHL-dependent morphological differences. Significant VHL-dependent biologic effects were observed on the surface of polymerized collagen I gels (Fig. 5B), but not on coatings of laminin, collagen IV, or fibronectin (data not shown). At low cell density, growth of VHL(−) cells on collagen I was characterized by branching and scattering of cells (Fig. 5B, upper left), whereas VHL(+) cells grew in tight patches (Fig. 5B, lower left). At high cell density, VHL(−) cells were disorganized, branched, and intercalated (Fig. 5B, upper right), whereas VHL(+) cells formed a monolayer of polygonal cells characteristic of differentiated epithelia (Fig. 5B, lower right). Prior growth of VHL(+) cells at low density resulted in their branching during the initial hours of growth on collagen I, but they subsequently coalesced into tight patches of cobblestone-shaped cells after 2 to 3 days of growth (data not shown), indicating that cell density also plays a role in VHL-dependent morphological changes on collagen I.

VHL, cell-cell signaling, and cell-ECM signaling direct growth arrest.

VHL(+) cells maintained at high density for 4 weeks grew out of the monolayer on tissue culture plastic (Fig. 3, colony 11), but VHL(+) cells grown for 4 weeks on collagen I were confined to a monolayer (data not shown). In contrast, VHL(−) cells grew out of the monolayer both on plastic (Fig. 3, colony 12) and on collagen I (Fig. 5B, upper right) and invaded the collagen gel (data not shown).

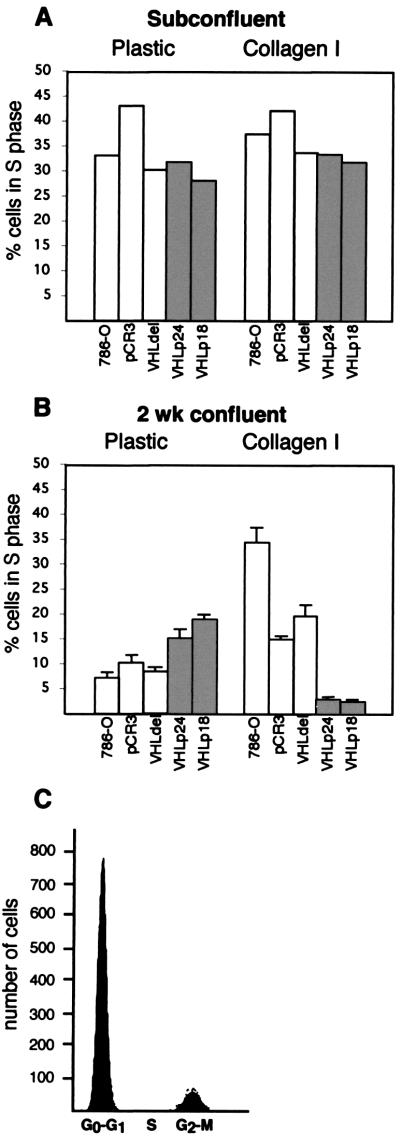

The confinement of VHL(+) cells to growth in two dimensions on collagen I suggested that VHL(+) cells undergo growth arrest after achieving maximum cell density. Flow cytometry was employed to directly compare the cell cycle profiles of cells grown on plastic and collagen I (Fig. 6). Cells maintained at low density (i.e., in active growth) on plastic or collagen I (Fig. 6A) showed equivalent S-phase profiles for VHL(−) and VHL(+) cells. Strikingly, after 2 weeks of culture at high density, VHL(−) cells had higher percentages of S-phase cells on collagen I than on plastic (Fig. 6B), whereas 2 weeks of culture at high density on collagen I led to the growth arrest of VHL(+) cells (Fig. 6B, right) in the G0-G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Cell cycle analysis of VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells grown on plastic and collagen I. VHL(−) and VHL(+) cell lines were grown at either low density (A) or for 2 weeks after attaining confluence (B) on plastic or on gels of polymerized collagen I. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACScan instrument. Percentages of cells in S phase in the VHL(−) lines (white) and VHL(+) lines (shaded) are shown. (C) Representative analysis of confluent VHL(+) cells grown on collagen I demonstrating the accumulation of arrested cells in the G0-G1 phase and the absence of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle.

Biochemical markers of the cell cycle were assayed to corroborate analysis by flow cytometry that indicated that VHL(+) cells grown at high density on collagen I undergo growth arrest. VHL(+) cells had hypophosphorylated pRb, elevated levels of p130, and decreased E2F-1 compared to the VHL(−) cells (data not shown). The relative expression of these markers demonstrated that VHL(−) cells were proliferating on collagen I while VHL(+) cells were growth arrested. These differences were not seen when cells were grown on plastic. These data are consistent with the observation that VHL(+) cells grow out of the monolayer on plastic but are confined to a monolayer on collagen I during prolonged growth.

VHL, cell-cell signaling, and cell-ECM signaling direct biochemical differentiation.

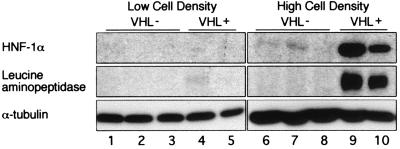

The epithelial morphology of VHL(+) cells, when cultured on ECM, suggested that VHL may also induce proximal tubule-specific biochemical differentiation. Therefore, the expression of HNF-1α, a transcription factor responsible for the maturation and maintenance of proximal tubule function (35), was examined by immunoblotting (Fig. 7, top row). At low cell density, HNF-1α protein was barely detectable in all cell lines (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 5). Growth of VHL(−) cells at high cell density resulted in low levels of HNF-1α (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 8). The combination of VHL expression and high cell density resulted in a dramatic increase in HNF-1α (Fig. 7, lanes 9 and 10). Thus, both VHL expression and cell-cell signaling were required for maximal induction of HNF-1α. Protein levels of leucine aminopeptidase, a proximal tubule brush-border enzyme and transcriptional target of HNF-1α, were also increased in a cell density- and VHL-dependent manner (Fig. 7, middle row) consistent with the induction of differentiation by VHL.

FIG. 7.

Regulation of HNF-1α and leucine aminopeptidase protein levels by VHL and cell density. VHL(−) and VHL(+) cell lines were grown at low density (lanes 1 to 5) or at high density (lanes 6 to 10) on plastic culture dishes. Thirty micrograms of lysate was loaded in each lane. Immunoblottings were performed to determine protein levels of HNF-1α (top row), leucine aminopeptidase (middle row), and α-tubulin (bottom row) to confirm equal loading, with monoclonal antibodies against HNF-1α (Transduction Laboratories), leucine aminopeptidase (B-F10; NeoMarkers), and α-tubulin (DM1A; Sigma). VHL(−) lines are 786-O (lanes 1 and 6), pCR3 vector only (lanes 2 and 7), and VHLdel114–178 (lanes 3 and 8). VHL(+) lines are VHLp18(MEA)-1 (lanes 4 and 9) and VHLp18(MEA)-2 (lanes 5 and 10).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that establishment of cell-cell and cell-ECM contact is necessary to elicit the biological functions of VHL critical for the control of renal cell growth and differentiation. Both the expression of functional VHL and the preconditioning of cells at high density were necessary to inhibit branching during the first hours of growth on Matrigel and collagen I, suggesting that VHL mediated cross talk between cell-cell and cell-ECM signaling pathways. Pharmacological inhibition of the cell cycle did not affect this phenotype. Moreover, although their cell cycle profiles were similar, the morphologies of VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells growing above the monolayer were significantly different after prolonged growth on plastic, further supporting the independence of cell cycle effects and VHL-dependent cell morphology. Previous studies also indicated that cell density and not cell cycle influenced the subcellular localization of VHL in transfected COS cells (22).

In the absence of exogenous matrix, growth of cells at high density was sufficient to manifest striking VHL-dependent changes in cell growth and morphology. Cells growing above the monolayer were most visibly affected as determined by scanning electron microscopy. VHL(+) cells were round and formed tight clusters, whereas VHL(−) cells were branched and scattered. Growth of cells as colonies for a prolonged time also revealed VHL-dependent macroscopic differences in multicellular organization. Prolonged growth on Matrigel and polymerized collagen I stimulated VHL(+) cells to grow as a coherent epithelial monolayer, whereas VHL(−) cells were disorganized and branched and grew above the monolayer and into the ECM substrates. We further demonstrate that VHL-dependent growth arrest is a consequence of the morphologic confinement of growth to a monolayer on ECM.

VHL has been reported to bind fibronectin (29), and VHL expression has been shown to correlate with the deposition of assembled fibronectin. Based on these observations, VHL was suggested to be involved in fibronectin assembly, and signaling from fibronectin may be involved in generating a differentiated phenotype (24, 29). However, 786-O cells showed no differences in growth on a fibronectin coating from growth on plastic (data not shown). Additionally, VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells grown on matrices deposited by either VHL(+) or VHL(−) cells were morphologically equivalent (data not shown). Thus, fibronectin deposition is not sufficient to elicit growth regulation of 786-O cells.

VHL has been reported to inhibit hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced invasion and branching morphogenesis in renal carcinoma cells (20), consistent with the observations reported here that VHL expression inhibits branching and invasion. However, under the conditions used in our studies, VHL(−) cells branched and were invasive in the absence of exogenous HGF, suggesting that VHL activity is independent of HGF signaling. Accordingly, activating mutations of the MET receptor (i.e., the receptor of the HGF ligand) are associated with papillary renal carcinomas and not clear RCCs in which inactivation of VHL is typical (36).

Growth at high cell density markedly diminished the ability of VHL-expressing cells to adhere to collagen I, although their integrin levels were unaffected by cell density. In the absence of VHL expression, cell density had a minimal affect on the adhesion of cells to collagen I although integrin levels were markedly increased. Thus, VHL and cell-cell signaling may be involved in the modulation of integrin function and may help account for some of the VHL-dependent morphologic and growth differences. In support of this contention, treatment of subconfluent cells with antibody to β1 integrin inhibited their spreading on ECM and produced a phenotype similar to that seen in VHL(+) cells grown at high density which have reduced integrin levels.

Polycystin-1, the PKD1 gene product, has been reported to associate with focal adhesion complexes and has been similarly proposed to down-regulate integrin-mediated epithelial cell adhesion to collagen I (41). Murine polycystic kidney epithelial cell lines have also been shown to have increased β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to collagen I (39). In addition, renal cysts and tumors from VHL patients have elevated levels of α3 and α5 integrins compared to those of normal proximal tubule cells (32). Moreover, immunohistological studies of ECM components in clear-cell renal carcinomas demonstrated that approximately 50% of the tumors had detectable levels of collagen I in contrast to the absence of collagen I in the ECM of normal proximal tubules (8). Taken together, these observations suggest that up-regulation of integrin mediated adhesion to collagen I may be a common defect contributing to the pathogenesis of VHL-associated renal cysts and clear-cell renal cancer.

Growth as a monolayer on ECM and tight cell-cell association exhibited by VHL(+) cells suggested that cadherin proteins may be affected by VHL. Immunoblot analysis of cadherins indicated that 786-O VHL(−) cells and VHL(+) cells expressed equivalent levels of N-cadherin which were similarly localized to the cell membrane (data not shown). No E or K cadherin expression was detected in any of the lines (data not shown). Furthermore, analysis of Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions from confluent cells grown on collagen I demonstrated similar levels of N-cadherin by immunoblotting, indicating that differences in N-cadherin are not associated with VHL-dependent morphologic differentiation. Thus, VHL may regulate other cadherins and/or molecules involved in cell-cell association.

The present data indicate that VHL mediates both biochemical and morphological differentiation of renal cells, extending the data presented by Lieubeau-Teillet et al. (24). VHL expression and high cell density mediated the up-regulation of HNF-1α, a transcriptional activator required for the expression of genes required for the maturation and maintenance of proximal tubules (42). Leucine aminopeptidase, a brush-border enzyme specific for the proximal tubule within the nephron, is a target for HNF-1α (30, 31). Leucine aminopeptidase expression was associated with the expression of HNF-1α, supporting a model whereby VHL affects the global differentiation of renal proximal tubule cells. VHL-dependent up-regulation of proximal tubule-specific markers is biologically significant since loss of differentiation is a characteristic of renal cysts and renal cell carcinomas (5) which are thought to arise from proximal renal tubular epithelial cells. HNF-1α functions as a homodimer or as a heterodimer with HNF-1β to activate the transcription of renal proximal tubule-specific proteins (30). HNF-1α function is lost in most RCCs (1, 6, 23). Loss of HNF-1β function has been associated with abnormal nephron development and multicystic dysplastic kidneys (3). HNF-1α is also involved in the maintenance of differentiation in the liver and pancreas (35). VHL disease often leads to the development of cysts in the kidney, liver, and pancreas, strengthening the argument that VHL loss resulting in decreases in HNF-1α levels contributes more globally to the pathogenesis of cysts and loss of differentiation. VHL in concert with cell-cell signaling is positioned to control proximal tubule differentiation by the activation and repression of numerous developmentally regulated genes by the modulation, in part, of HNF-1α levels and/or activity. However, inherited mutations in the HNF-1α gene in humans are not associated with the development of renal cysts and RCC (1). Thus, although we demonstrate that HNF-1α expression and proximal tubule epithelial cell differentiation are dependent on the expression of functional VHL, the tumor suppressor function of VHL cannot be based solely on the regulation of HNF-1α expression. This supports accumulating evidence that VHL functions through multiple pathways.

Taken together, these results suggest a model in which VHL functions to redirect cell-cell and cell-ECM signaling from inducing proliferative and disorganized growth to inducing differentiation and growth arrest. In the absence of VHL expression, growth at high cell density caused increased integrin expression, whereas VHL-expressing cells grown at high density were less adhesive and more differentiated, as indicated by higher levels of HNF-1α. Cell growth at high density on ECM was stimulated in the absence of VHL, whereas VHL(+) cells were growth arrested. Thus, VHL plays a major role in determining whether cells undergo growth arrest and differentiation or continue to proliferate in an undifferentiated state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeffrey Segal, Peter Mundel and Prasad Devarajan for critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Michael Cammer, Leslie Gunther, and Frank Macaluso for their assistance with microscopy and image analysis and David Gebhard for assistance with FACS analysis. All microscopy was performed at the Analytical Imaging Facility of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized in the oligonucleotide facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (partially supported by grant CA 13330). Monoclonal antibodies were produced at the Hybridoma Facility of the Cancer Center of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the VHL Family Alliance. A.R.S. was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (CA 09060). E.J.D. was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (DK 07218).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anastasiadis A G, Lemm I, Radzewitz A, Lingott A, Ebert T, Ackermann R, Ryffel G U, Schulz W A. Loss of function of the tissue specific transcription factor HNF1 alpha in renal cell carcinoma and clinical prognosis. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:2105–2110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper J W, Elledge S J. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingham C, Ellard S, Allen L, Bulman M, Shepherd M, Frayling T, Berry P J, Clark P M, Linder T, Bell G I, Ryffel G U, Nicholls A J, Hattersley A T. Abnormal nephron development associated with a frameshift mutation in the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta. Kidney Int. 2000;57:898–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.057003898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvet J P. Molecular genetics of polycystic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 1998;11:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvet J P. Polycystic kidney disease: primary extracellular matrix abnormality or defective cellular differentiation? Kidney Int. 1993;43:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clairmont A, Ebert T, Weber H, Zoidl C, Eickelmann P, Schulz W A, Sies H, Ryffel G U. Lowered amounts of the tissue-specific transcription factor LFB1 (HNF1) correlate with decreased levels of glutathione S-transferase alpha messenger RNA in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1319–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockman M E, Masson N, Mole D R, Jaakkola P, Chang G W, Clifford S C, Maher E R, Pugh C W, Ratcliffe P J, Maxwell P H. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25733–25741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Droz D, Patey N, Paraf F, Chretien Y, Gogusev J. Composition of extracellular matrix and distribution of cell adhesion molecules in renal cell tumors. Lab Investig. 1994;71:710–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan D R, Humphrey J S, Chen D Y, Weng Y, Sukegawa J, Lee S, Gnarra J R, Linehan W M, Klausner R D. Characterization of the VHL tumor suppressor gene product: localization, complex formation, and the effect of natural inactivating mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6459–6463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris P C. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: clues to pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1861–1866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iliopoulos O, Kibel A, Gray S, Kaelin W G. Tumor suppression by the human von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Nat Med. 1995;1:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iliopoulos O, Ohh M, Kaelin W G., Jr pVHL19 is a biologically active product of the von Hippel-Lindau gene arising from internal translation initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11661–11666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwai K, Yamanaka K, Kamura T, Minato N, Conaway R C, Conaway J W, Klausner R D, Pause A. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor-suppressor protein as part of an active E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12436–12441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson R T, Downes C S, Meyn R E. The synchronization of mammalian cells. In: Fantes P, Brooks R, editors. The cell cycle: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press, Ltd.; 1993. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaelin W G, Jr, Maher E R. The VHL tumour-suppressor gene paradigm. Trends Genet. 1998;14:423–426. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamura T, Conrad M N, Yan Q, Conaway R C, Conaway J W. The Rbx1 subunit of SCF and VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase activates Rub1 modification of cullins Cdc53 and Cul2. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2928–2933. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamura T, Koepp D M, Conrad M N, Skowyra D, Moreland R J, Iliopoulos O, Lane W S, Kaelin W G, Jr, Elledge S J, Conaway R C, Harper J W, Conaway J W. Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science. 1999;284:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamura T, Sato S, Iwai K, Czyzyk-Krzeska M, Conaway R C, Conaway J W. Activation of HIF1alpha ubiquitination by a reconstituted von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10430–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190332597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kibel A, Iliopoulos O, DeCaprio J A, Kaelin W G. Binding of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein to elongin B and C. Science. 1995;269:1444–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.7660130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koochekpour S, Jeffers M, Wang P H, Gong C, Taylor G A, Roessler L M, Stearman R, Vasselli J R, Stetler-Stevenson W G, Kaelin W G, Jr, Linehan W M, Klausner R D, Gnarra J R, Vande Woude G F. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inhibits hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced invasion and branching morphogenesis in renal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5902–5912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh F M, Orcutt M L, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L, Schmidt L, Zhou F, Li H, Wei M H, Chen F, Glenn G, Choyke P, Walther M M, Weng Y, Duan D R, Dean M, Glavac D, Richards F, Crossey P A, Ferguson-Smith M A, Paslier D L, Chumakov I, Cohen D, Chinault A C, Maher E R, Linehan W M, Zbar B, Lerman M I. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260:1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Chen D Y T, Humphrey J S, Gnarra J R, Linehan W M, Klausner R D. Nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene product is determined by cell density. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1770–1775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemm I, Lingott A, Pogge v. Strandmann E, Zoidl C, Bulman M P, Hattersley A T, Schulz W A, Ebert T, Ryffel G U. Loss of HNF1alpha function in human renal cell carcinoma: frequent mutations in the VHL gene but not the HNF1alpha gene. Mol Carcinog. 1999;24:305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieubeau-Teillet B, Rak J, Jothy S, Iliopoulos O, Kaelin W, Kerbel R S. von Hippel-Lindau gene-mediated growth suppression and induction of differentiation in renal cell carcinoma cells grown as multicellular tumor spheroids. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4957–4962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lisztwan J, Imbert G, Wirbelauer C, Gstaiger M, Krek W. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein is a component of an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1822–1833. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonergan K M, Iliopoulos O, Ohh M, Kamura T, Conaway R C, Conaway J W, Kaelin W G., Jr Regulation of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein requires binding to complexes containing elongins B/C and Cul2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Los M, Zeamari S, Foekens J A, Gebbink M F, Voest E E. Regulation of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohh M, Park C W, Ivan M, Hoffman M A, Kim T Y, Huang L E, Pavletich N, Chau V, Kaelin W G. Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:423–427. doi: 10.1038/35017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohh M, Yauch R L, Lonergan K M, Whaley J M, Stemmer-Rachamimov A O, Louis D N, Gavin B J, Kley N, Kaelin W G, Jr, Iliopoulos O. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein is required for proper assembly of an extracellular fibronectin matrix. Mol Cell. 1998;1:959–968. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen J, Laustsen L, Karnstrom U, Sjostrom H, Noren O. Tissue-specific interactions between nuclear proteins and the aminopeptidase N promoter. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18089–18096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen J, Laustsen L, Troelsen J. HNF1 alpha activates the aminopeptidase N promoter in intestinal (Caco-2) cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:325–328. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paraf F, Chauveau D, Chretien Y, Richard S, Grunfeld J P, Droz D. Renal lesions in von Hippel-Lindau disease: immunohistochemical expression of nephron differentiation molecules, adhesion molecules and apoptosis proteins. Histopathology. 2000;36:457–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pause A, Lee S, Lonergan K M, Klausner R D. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene is required for cell cycle exit upon serum withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:993–998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pause A, Lee S, Worrell R A, Chen D Y, Burgess W H, Linehan W M, Klausner R D. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor-suppressor gene product forms a stable complex with human CUL-2, a member of the Cdc53 family of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2156–2161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach J P, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt L, Duh F M, Chen F, Kishida T, Glenn G, Choyke P, Scherer S W, Zhuang Z, Lubensky I, Dean M, Allikmets R, Chidambaram A, Bergerheim U R, Feltis J T, Casadevall C, Zamarron A, Bernues M, Richard S, Lips C J, Walther M M, Tsui L C, Geil L, Orcutt M L, Stackhouse T, Zbar B, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoenfeld A, Davidowitz E J, Burk R D. A second major native von Hippel-Lindau gene product, initiated from an internal translation start site, functions as a tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8817–8822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanimoto K, Makino Y, Pereira T, Poellinger L. Mechanism of regulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha by the von hippel-lindau tumor suppressor protein. EMBO J. 2000;19:4298–4309. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Adelsberg J. Murine polycystic kidney epithelial cell lines have increased integrin-mediated adhesion to collagen. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F1082–F1093. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.6.F1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watnick T, Germino G G. Molecular basis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19:327–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson P D, Burrow C R. Cystic diseases of the kidney: role of adhesion molecules in normal and abnormal tubulogenesis. Exp Nephrol. 1999;7:114–124. doi: 10.1159/000020592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witzgall R. The proximal tubule phenotype and its disruption in acute renal failure and polycystic kidney disease. Exp Nephrol. 1999;7:15–19. doi: 10.1159/000020579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]